Info

Head of an old man.

Rembrandt

1628 – 1630

Agnes Etherington Art Centre

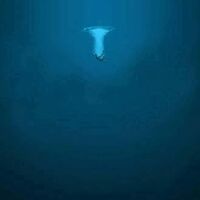

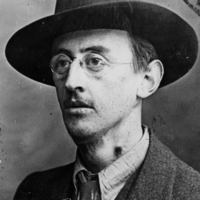

Stephen P. H. Butler Leacock, (30 December 1869 – 28 March 1944) was a Canadian teacher, political scientist, writer, and humorist. Between the years 1915 and 1925, he was the best-known English-speaking humorist in the world. He is known for his light humour along with criticisms of people’s follies. The Stephen Leacock Memorial Medal for Humour was named in his honour. Early life Stephen Leacock was born in Swanmore, a village near Southampton in southern England. He was the third of the eleven children born to (Walter) Peter Leacock (b.1834), who was born and grew up at Oak Hill on the Isle of Wight, an estate that his grandfather had purchased after returning from Madeira where his family had made a fortune out of plantations and Leacock’s Madeira wine, founded in 1760. Stephen’s mother, Agnes, was born at Soberton, the youngest daughter by his second wife (Caroline Linton Palmer) of the Rev. Stephen Butler, of Bury Lodge, the Butler estate that overlooked the village of Hambledon, Hampshire. Stephen Butler (for whom Leacock was named), was the maternal grandson of Admiral James Richard Dacres and a brother of Sir Thomas Dacres Butler, Usher of the Black Rod. Leacock’s mother was the half-sister of Major Thomas Adair Butler, who won the Victoria Cross at the siege and capture of Lucknow. Peter’s father, Thomas Murdock Leacock J.P., had already conceived plans eventually to send his son out to the colonies, but when he discovered that at age eighteen Peter had married Agnes Butler without his permission, almost immediately he shipped them out to South Africa where he had bought them a farm. The farm in South Africa failed and Stephen’s parents returned to Hampshire, where he was born. When Stephen was six, he came out with his family to Canada, where they settled on a farm near the village of Sutton, Ontario, and the shores of Lake Simcoe. Their farm in the township of Georgina in York County was also unsuccessful, and the family was kept afloat by money sent from Leacock’s paternal grandfather. His father became an alcoholic; in the fall of 1878, he travelled west to Manitoba with his brother E.P. Leacock (the subject of Stephen’s book My Remarkable Uncle, published in 1942), leaving behind Agnes and the children. Stephen Leacock, always of obvious intelligence, was sent by his grandfather to the elite private school of Upper Canada College in Toronto, also attended by his older brothers, where he was top of the class and was chosen as head boy. Leacock graduated in 1887, and returned home to find that his father had returned from Manitoba. Soon after, his father left the family again and never returned. There is some disagreement about what happened to Peter Leacock; some suggest that he went to live in Argentina, while other sources indicate that he moved to Nova Scotia and changed his name to Lewis. In 1887, seventeen-year-old Leacock started at University College at the University of Toronto, where he was admitted to the Zeta Psi fraternity. His first year was bankrolled by a small scholarship, but Leacock found he could not return to his studies the following year because of financial difficulties. He left university to work as a teacher—an occupation he disliked immensely—at Strathroy, Uxbridge and finally in Toronto. As a teacher at Upper Canada College, his alma mater, he was able simultaneously to attend classes at the University of Toronto and, in 1891, earn his degree through part-time studies. It was during this period that his first writing was published in The Varsity, a campus newspaper. Academic and political life Disillusioned with teaching, in 1899 he began graduate studies at the University of Chicago under Thorstein Veblen, where he received a doctorate in political science and political economy. He moved from Chicago, Illinois to Montreal, Quebec, where he eventually became the William Dow Professor of Political Economy and long-time chair of the Department of Economics and Political Science at McGill University. He was closely associated with Sir Arthur Currie, former commander of the Canadian Corps in the Great War and principal of McGill from 1919 until his death in 1933. In fact, Currie had been a student observing Leacock’s practice teaching in Strathroy in 1888. In 1936, Leacock was forcibly retired by the McGill Board of Governors—an unlikely prospect had Currie lived. Leacock was both a social conservative and a partisan Conservative. He opposed giving women the right to vote, and had a mixed record on non-Anglo-Saxon immigration, having written both in support of expanding immigration beyond Anglo-Saxons prior to World War II and in opposition to expanding Canadian immigration beyond Anglo Saxons near the close of World War II. He was a staunch champion of the British Empire and the Imperial Federation Movement and went on lecture tours to further the cause. Despite his conservatism, he was a staunch advocate for social welfare legislation and wealth redistribution. Although Prime Minister R.B. Bennett asked him to be a candidate for the 1935 Dominion election, Leacock declined the invitation. Nevertheless, he would stump for local Conservative candidates at his summer home. Literary life Early in his career, Leacock turned to fiction, humour, and short reports to supplement (and ultimately exceed) his regular income. His stories, first published in magazines in Canada and the United States and later in novel form, became extremely popular around the world. It was said in 1911 that more people had heard of Stephen Leacock than had heard of Canada. Also, between the years 1915 and 1925, Leacock was the most popular humorist in the English-speaking world. A humorist particularly admired by Leacock was Robert Benchley from New York. Leacock opened correspondence with Benchley, encouraging him in his work and importuning him to compile his work into a book. Benchley did so in 1922, and acknowledged the nagging from north of the border. Near the end of his life, the American comedian Jack Benny recounted how he had been introduced to Leacock’s writing by Groucho Marx when they were both young vaudeville comedians. Benny acknowledged Leacock’s influence and, fifty years after first reading him, still considered Leacock one of his favorite comic writers. He was puzzled as to why Leacock’s work was no longer well known in the United States. During the summer months, Leacock lived at Old Brewery Bay, his summer estate in Orillia, across Lake Simcoe from where he was raised and also bordering Lake Couchiching. A working farm, Old Brewery Bay is now a museum and National Historic Site of Canada. Gossip provided by the local barber, Jefferson Short, provided Leacock with the material which would become Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town (1912), set in the thinly-disguised Mariposa. Although he wrote learned articles and books related to his field of study, his political theory is now all but forgotten. Leacock was awarded the Royal Society of Canada’s Lorne Pierce Medal in 1937, nominally for his academic work. “The proper punishment for the Hohenzollerns, and the Hapsburgs, and the Mecklenburgs, and the Muckendorfs, and all such puppets and princelings, is that they should be made to work; and not made to work in the glittering and glorious sense, as generals and chiefs of staff, and legislators, and land-barons, but in the plain and humble part of labourers looking for a job. (Leacock 1919: 9)” Memorial Medal for Humour The Stephen Leacock Associates is a foundation chartered to preserve the literary legacy of Stephen Leacock, and oversee the annual award of the Stephen Leacock Memorial Medal for Humour. It is a prestigious honour, given to encourage Canadian humour writing and awarded for the best in Canadian humour writing. The foundation was instituted in 1946 and awarded the first Leacock Medal in 1947. The presentation occurs in June each year at the Stephen Leacock Award Dinner, at the Geneva Park Conference Centre in Orillia, Ontario. Personal life Leacock was born in England in 1869. His father, Peter Leacock, and his mother, Agnes Emma Butler Leacock, were both from well-to-do families. The family, eventually consisting of eleven children, immigrated to Canada in 1876, settling on a one hundred-acre farm in Sutton, Ontario. There Stephen was home-schooled until he was enrolled in Upper Canada College, Toronto. He became the head boy in 1887, and then entered the University of Toronto to study languages and literature. Despite completing two years of study in one year, he was forced to leave the university because his father had abandoned the family. Instead, Leacock enrolled in a three-month course at Strathroy Collegiate Institute to become a qualified high school teacher. His first appointment was at Uxbridge High School, Ontario, but he was soon offered a post at Upper Canada College, where he remained from 1889 through 1899. At this time, he also resumed part-time studies at the University of Toronto, graduating with a B.A. in 1891. However, Leacock’s real interests were turning towards economics and political theory, and in 1899 he was accepted for postgraduate studies at the University of Chicago, where he earned his PhD in 1903 In 1900 Leacock married Beatrix Hamilton, niece of Sir Henry Pellatt, who had built Casa Loma, the largest castle in North America. In 1915, after 15 years of marriage, the couple had their only child, Stephen Lushington Leacock. While Leacock doted on the boy, it soon became apparent that “Stevie” suffered from a lack of growth hormone. Growing to be only four feet tall, he had a love-hate relationship with Leacock, who tended to treat him like a child. Beatrix died in 1925 due to breast cancer. Leacock was offered a post at McGill University, where he remained until he retired in 1936. In 1906, he wrote Elements of Political Science, which remained a standard college textbook for the next twenty years and became his most profitable book. He also began public speaking and lecturing, and he took a year’s leave of absence in 1907 to speak throughout Canada on the subject of national unity. He typically spoke on national unity or the British Empire for the rest of his life. Leacock began submitting articles to the Toronto humor magazine Grip in 1894, and soon was publishing many humorous articles in Canadian and American magazines. In 1910, he privately published the best of these as Literary Lapses. The book was spotted by a British publisher, John Lane, who brought out editions in London and New York, assuring Leacock’s future as a writer. This was confirmed by Literary Lapses (1910), Nonsense Novels (1911) – probably his best books of humorous sketches—and by the more sentimental favorite, Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town (1912). John Lane introduced the young cartoonist Annie Fish to illustrate his 1913 book Behind the Beyond. Leacock’s humorous style was reminiscent of Mark Twain and Charles Dickens at their sunniest—for example in his even and satisfying My Discovery of England (1922). However, his Arcadian Adventures with the Idle Rich (1914) is a darker collection that satirizes city life. Collections of sketches continued to follow almost annually at times, with a mixture of whimsy, parody, nonsense, and satire that was never bitter. Leacock was enormously popular not only in Canada but in the United States and Britain. In later life, Leacock wrote on the art of humor writing and also published biographies of Twain and Dickens. After retirement, a lecture tour to western Canada led to his book My Discovery of the West: A Discussion of East and West in Canada (1937), for which he won the Governor General’s Award. He also won the Mark Twain medal and received a number of honorary doctorates. Other nonfiction books on Canadian topics followed and he began work on an autobiography. Leacock died of throat cancer in Toronto in 1944. A prize for the best humour writing in Canada was named after him, and his house at Orillia on the banks of Lake Couchiching became the Stephen Leacock Museum. Death and tributes Predeceased by Trix (who had died of breast cancer in 1925), Leacock was survived by son Stevie (Stephen Lushington Leacock (1915–1974). In accordance with his wishes, after his death from throat cancer, Leacock was buried in the St George the Martyr Churchyard (St. George’s Church, Sibbald Point), Sutton, Ontario Shortly after his death, Barbara Nimmo, his niece, literary executor and benefactor, published two major posthumous works: Last Leaves (1945) and The Boy I Left Behind Me (1946). His physical legacy was less treasured, and his abandoned summer cottage became derelict. It was rescued from oblivion when it was declared a National Historic Site of Canada in 1958 and ever since has operated as a museum called the Stephen Leacock Museum National Historic Site. In 1947, the Stephen Leacock Award was created to meet the best in Canadian literary humour. In 1969, the centennial of his birth, Canada Post issued a six-cent stamp with his image on it. The following year, the Stephen Leacock Centennial Committee had a plaque erected at his English birthplace and a mountain in the Yukon was named after him. A number of buildings in Canada are named after Leacock, including the Stephen Leacock Building at McGill University, Stephen Leacock Public School in Ottawa, a theatre in Keswick, Ontario, and a school Stephen Leacock Collegiate Institute in Toronto. Screen adaptations Two Leacock short stories have been adapted as National Film Board of Canada animated shorts by Gerald Potterton: My Financial Career and The Awful Fate of Melpomenus Jones. Sunshine Sketches, based on Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town, aired on CBC Television in 1952–1953; it was the first Canadian broadcast of an English-language dramatic series, as it debuted on the first night that television was broadcast in Toronto. In 2012, a screen adaptation based on Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town was aired on CBC Television to celebrate both the 75th anniversary of the CBC and the 100th anniversary of Leacock’s original collection of short stories. The recent screen adaptation featured Gordon Pinsent as a mature Leacock. Bibliography Fiction * Literary Lapses (1910) * Nonsense Novels (1911) * Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town (1912) * Behind the Beyond (1913)– illustrated by Annie Fish. * Arcadian Adventures with the Idle Rich (1914) * Moonbeams from the Larger Lunacy (1915) * Further Foolishness (1916) * Essays and Literary Studies (1916) * Frenzied Fiction (1918) * The Hohenzollerns in America (1919) * Winsome Winnie (1920) * My Discovery of England (1922) * College Days (1923) * Over the Footlights (1923) * The Garden of Folly (1924) * Winnowed Wisdom (1926) * Short Circuits (1928) * The Iron Man and the Tin Woman (1929) * Laugh With Leacock (1930) * The Dry Pickwick (1932) * Afternoons in Utopia (1932) * Hellements of Hickonomics in Hiccoughs of Verse Done in Our Social Planning Mill (1936) * Model Memoirs (1938) * Too Much College (1939) * My Remarkable Uncle (1942) * Happy Stories (1943) * How to Write (1943) * Last Leaves (1945) * My Lost Dollar Non-fiction * Elements of Political Science (1906) * Baldwin, Lafontaine, Hincks: Responsible Government (1907) * Practical Political Economy (1910) * Adventurers of the Far North (1914) * The Dawn of Canadian History (1914) * The Mariner of St. Malo: a chronicle of the voyages of Jacques Cartier (1914) * The Unsolved Riddle of Social Justice (1920) * Mackenzie, Baldwin, Lafontaine, Hincks (1926) * Economic Prosperity in the British Empire (1930) * The Economic Prosperity of the British Empire (1931) * Humour: Its Theory and Technique, with Examples and Samples (1935) * The Greatest Pages of American Humor (1936) * Humour and Humanity (1937) * Here Are My Lectures (1937) * My Discovery of the West (1937) * Our British Empire (1940) * Canada: The Foundations of Its Future (1941) * Our Heritage of Liberty (1942) * Montreal: Seaport and City (1942) * Canada and the Sea (1944) * While There Is Time (1945) * My Lost Dollar Biography * Mark Twain (1932) * Charles Dickens: His Life and Work (1933) Autobiography * The Boy I Left Behind Me (1946) Quotations * "Lord Ronald … flung himself upon his horse and rode madly off in all directions."—Nonsense Novels, “Gertrude the Governess”, 1911 * “Professor Leacock has made more people laugh with the written word than any other living author. One may say he is one of the greatest jesters, the greatest humorist of the age.”—A. P. Herbert * “Mr Leacock is as 'bracing’ as the seaside place of John Hassall’s famous poster. His wisdom is always humorous, and his humour is always wise.”—Sunday Times * “He is still inimitable. No one, anywhere in the world, can reduce a thing to ridicule with such few short strokes. He is the Grock of literature.”—Evening Standard * “I detest life-insurance agents: they always argue that I shall some day die, which is not so.” * “Hockey captures the essence of Canadian experience in the New World. In a land so inescapably and inhospitably cold, hockey is the chance of life, and an affirmation that despite the deathly chill of winter we are alive.” References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stephen_Leacock

Born near St. Louis, Missouri, on November 15, 1887, Marianne Moore was raised in the home of her grandfather, a Presbyterian pastor. After her grandfather's death, in 1894, Moore and her family stayed with other relatives, and in 1896 they moved to Carlisle, Pennsylvania. She attended Bryn Mawr College and received her B.A. in 1909. Following graduation, Moore studied typing at Carlisle Commercial College, and from 1911 to 1915 she was employed as a school teacher at the Carlisle Indian School. In 1918, Moore and her mother moved to New York City, and in 1921, she became an assistant at the New York Public Library. She began to meet other poets, such as William Carlos Williams and Wallace Stevens, and to contribute to the Dial, a prestigious literary magazine. She served as acting editor of the Dial from 1925 to 1929. Along with the work of such other members of the Imagist movement as Ezra Pound, Williams, and H. D., Moore's poems were published in the Egoist, an English magazine, beginning in 1915. In 1921, H.D. published Moore's first book, Poems, without her knowledge. Moore was widely recognized for her work; among her many honors were the Bollingen prize, the National Book Award, and the Pulitzer Prize. She wrote with the freedom characteristic of the other modernist poets, often incorporating quotes from other sources into the text, yet her use of language was always extraordinarily condensed and precise, capable of suggesting a variety of ideas and associations within a single, compact image. In his 1925 essay "Marianne Moore," William Carlos Williams wrote about Moore's signature mode, the vastness of the particular: "So that in looking at some apparently small object, one feels the swirl of great events." She was particularly fond of animals, and much of her imagery is drawn from the natural world. She was also a great fan of professional baseball and an admirer of Muhammed Ali, for whom she wrote the liner notes to his record, I Am the Greatest! Deeply attached to her mother, she lived with her until Mrs. Moore's death in 1947. Marianne Moore died in New York City in 1972. Poetry Collected Poems (1951) Like a Bulwark (1956) Nevertheless (1944) O to Be a Dragon (1959) Observations (1924) Poems (1921) Selected Poems (1935) Tell Me, Tell Me (1966) The Arctic Fox (1964) The Complete Poems of Marianne Moore (1967) The Pangolin and Other Verse (1936) What Are Years? (1941) Prose A Marianne Moore Reader (1961) Predilections (1955) The Complete Prose of Marianne Moore (1987)

Florence Margaret Smith, known as Stevie Smith (20 September 1902– 7 March 1971) was an English poet and novelist. Life Stevie Smith, born Florence Margaret Smith in Kingston upon Hull, was the second daughter of Ethel and Charles Smith. She was called “Peggy” within her family, but acquired the name “Stevie” as a young woman when she was riding in the park with a friend who said that she reminded him of the jockey Steve Donoghue. Her father was a shipping agent, a business that he had inherited from his father. As the company and his marriage began to fall apart, he ran away to sea and Smith saw very little of her father after that. He appeared occasionally on 24-hour shore leave and sent very brief postcards ("Off to Valparaiso, Love Daddy"). When she was three years old she moved with her mother and sister to Palmers Green in North London where Smith would live until her death in 1971. She resented the fact that her father had abandoned his family. Later, when her mother became ill, her aunt Madge Spear (whom Smith called “The Lion Aunt”) came to live with them, raised Smith and her elder sister Molly and became the most important person in Smith’s life. Spear was a feminist who claimed to have “no patience” with men and, as Smith wrote, “she also had 'no patience’ with Hitler”. Smith and Molly were raised without men and thus became attached to their own independence, in contrast to what Smith described as the typical Victorian family atmosphere of “father knows best”. When Smith was five she developed tubercular peritonitis and was sent to a sanatorium near Broadstairs, Kent, where she remained for three years. She related that her preoccupation with death began when she was seven, at a time when she was very distressed at being sent away from her mother. Death and fear fascinated her and provide the subjects of many of her poems. Her mother died when Smith was 16. When suffering from the depression to which she was subject all her life she was so consoled by the thought of death as a release that, as she put it, she did not have to commit suicide. She wrote in several poems that death was “the only god who must come when he is called”. Smith suffered throughout her life from an acute nervousness, described as a mix of shyness and intense sensitivity. In the Poem “A House of Mercy”, she wrote of her childhood house in North London: It was a house of female habitation, Two ladies fair inhabited the house, And they were brave. For although Fear knocked loud Upon the door, and said he must come in, They did not let him in. Smith was educated at Palmers Green High School and North London Collegiate School for Girls. She spent the remainder of her life with her aunt, and worked as private secretary to Sir Neville Pearson with Sir George Newnes at Newnes Publishing Company in London from 1923 to 1953. Despite her secluded life, she corresponded and socialised widely with other writers and creative artists, including Elisabeth Lutyens, Sally Chilver, Inez Holden, Naomi Mitchison, Isobel English and Anna Kallin. After she retired from Sir Neville Pearson’s service following a nervous breakdown she gave poetry readings and broadcasts on the BBC that gained her new friends and readers among a younger generation. Sylvia Plath became a fan of her poetry and sent Smith a letter in 1962, describing herself as “a desperate Smith-addict.” Plath expressed interest in meeting in person but committed suicide soon after sending the letter. Smith was described by her friends as being naive and selfish in some ways and formidably intelligent in others, having been raised by her aunt as both a spoiled child and a resolutely autonomous woman. Likewise, her political views vacillated between her aunt’s Toryism and her friends’ left-wing tendencies. Smith was celibate for most of her life, although she rejected the idea that she was lonely as a result, alleging that she had a number of intimate relationships with friends and family that kept her fulfilled. She never entirely abandoned or accepted the Anglican faith of her childhood, describing herself as a “lapsed atheist”, and wrote sensitively about theological puzzles;"There is a God in whom I do not believe/Yet to this God my love stretches." Her 14-page essay of 1958, “The Necessity of Not Believing”, concludes: “There is no reason to be sad, as some people are sad when they feel religion slipping off from them. There is no reason to be sad, it is a good thing.” Smith died of a brain tumour on 7 March 1971. Her last collection, Scorpion and other Poems was published posthumously in 1972, and the Collected Poems followed in 1975. Three novels were republished and there was a successful play based on her life, Stevie, written by Hugh Whitemore. It was filmed in 1978 by Robert Enders and starred Glenda Jackson and Mona Washbourne. Fiction Smith wrote three novels, the first of which, Novel on Yellow Paper, was published in 1936. Apart from death, common subjects in her writing include loneliness; myth and legend; absurd vignettes, usually drawn from middle-class British life, war, human cruelty and religion. All her novels are lightly fictionalised accounts of her own life, which got her into trouble at times as people recognised themselves. Smith said that two of the male characters in her last book are different aspects of George Orwell, who was close to Smith. There were rumours that they were lovers; he was married to his first wife at the time. Novel on Yellow Paper (Cape, 1936) Smith’s first novel is structured as the random typings of a bored secretary, Pompey. She plays word games, retells stories from classical and popular culture, remembers events from her childhood, gossips about her friends and describes her family, particularly her beloved Aunt. As with all Smith’s novels, there is an early scene where the heroine expresses feelings and beliefs which she will later feel significant, although ambiguous, regret for. In Novel on Yellow Paper that belief is anti-Semitism, where she feels elation at being the “only Goy” at a Jewish party. This apparently throwaway scene acts as a timebomb, which detonates at the centre of the novel when Pompey visits Germany as the Nazis are gaining power. With horror, she acknowledges the continuity between her feeling “Hurray for being a Goy” at the party and the madness that is overtaking Germany. The German scenes stand out in the novel, but perhaps equally powerful is her dissection of failed love. She describes two unsuccessful relationships, first with the German Karl and then with the suburban Freddy. The final section of the novel describes with unusual clarity the intense pain of her break-up with Freddy. Over the Frontier (Cape, 1938) Smith herself dismissed her second novel as a failed experiment, but its attempt to parody popular genre fiction to explore profound political issues now seems to anticipate post-modern fiction. If anti-Semitism was one of the key themes of Novel on Yellow Paper, Over the Frontier is concerned with militarism. In particular, she asks how the necessity of fighting Fascism can be achieved without descending into the nationalism and dehumanisation that fascism represents. After a failed romance the heroine, Pompey, suffers a breakdown and is sent to Germany to recuperate. At this point the novel changes style radically, as Pompey becomes part of an adventure/spy yarn in the style of John Buchan or Dornford Yates. As the novel becomes increasingly dreamlike, Pompey crosses over the frontier to become a spy and soldier. If her initial motives are idealistic, she becomes seduced by the intrigue and, ultimately, violence. The vision Smith offers is a bleak one: “Power and cruelty are the strengths of our lives, and only in their weakness is there love.” The Holiday (Chapman and Hall, 1949) Smith’s final novel is her own favourite, and most fully realised. It is concerned with personal and political malaise in the immediate post-war period. Most of the characters are either employed in the army or civil service in post-war reconstruction, and its heroine, Celia, works for the Ministry as a cryptographer and propagandist. The Holiday describes a series of hopeless relationships. Celia and her cousin Caz are in love, but cannot pursue their affair since it is believed that, because of their parents’ adultery, they are half-brother and sister. Celia’s other cousin Tom is in love with her, Basil is love with Tom, Tom is estranged from his father, Celia’s beloved Uncle Heber, who pines for a reconciliation; and Celia’s best friend Tiny longs for the married Vera. These unhappy, futureless but intractable relationships are mirrored by the novel’s political concerns. The unsustainability of the British Empire and the uncertainty over Britain’s post-war role are constant themes, and many of the characters discuss their personal and political concerns as if they were seamlessly linked. Caz is on leave from Palestine and is deeply disillusioned, Tom goes mad during the war, and it is telling that the family scandal that blights Celia and Caz’s lives took place in India. Just as Pompey’s anti-semitism was tested in Novel on Yellow Paper, so Celia’s traditional nationalism and sentimental support for colonialism is challenged throughout The Holiday. Poetry Smith’s first volume of poetry, the self-illustrated A Good Time Was Had By All, was published in 1937 and established her as a poet. Soon her poems were found in periodicals. Her style was often very dark; her characters were perpetually saying “goodbye” to their friends or welcoming death. At the same time her work has an eerie levity and can be very funny though it is neither light nor whimsical. “Stevie Smith often uses the word 'peculiar’ and it is the best word to describe her effects” (Hermione Lee). She was never sentimental, undercutting any pathetic effects with the ruthless honesty of her humour. “A good time was had by all” itself became a catch phrase, still occasionally used to this day. Smith said she got the phrase from parish magazines, where descriptions of church picnics often included this phrase. This saying has become so familiar that it is recognised even by those who are unaware of its origin. Variations appear in pop culture, including “Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!” by the Beatles. Though her poems were remarkably consistent in tone and quality throughout her life, their subject matter changed over time, with less of the outrageous wit of her youth and more reflection on suffering, faith and the end of life. Her best-known poem is “Not Waving but Drowning”. She was awarded the Cholmondeley Award for Poets in 1966 and won the Queen’s Gold Medal for poetry in 1969. She published nine volumes of poems in her lifetime (three more were released posthumously).

Joseph Mary Plunkett (Irish: Seosamh Máire Pluincéid, 21 November 1887– 12 May 1916) was an Irish nationalist, poet, journalist, and a leader of the 1916 Easter Rising. He was born at 26 Upper Fitzwilliam Street in one of Dublin’s most affluent neighbourhoods. Both his parents came from wealthy backgrounds, and his father, George Noble Plunkett, had been made a papal count. Despite being born into a life of privilege, young Joe Plunkett did not have an easy childhood.

Humble, respectful, persistent a few of the words that can be used to describe myself. Kimiko Watson, a young lady of 19 years, a teacher in training. I am a student of the Bethlehem Moravian Teachers' College as our motto says: 'Mihi Cura Futuri' which is to say 'My care if for the Future'. My grandmother is the reason why I write. She has always encourage me by telling me that I can be anything and do anything that i put my mind to. I will continue to believe that any thing that I concieve I can and will achieve.

Edwin George Morgan (27 April 1920 – 17 August 2010) was a Scottish poet and translator who was associated with the Scottish Renaissance. He is widely recognised as one of the foremost Scottish poets of the 20th century. In 1999, Morgan was made the first Glasgow Poet Laureate. In 2004, he was named as the first Scottish national poet: The Scots Makar. Life and career Morgan was born in Glasgow and grew up in Rutherglen. His parents were Presbyterian. As a child he was not surrounded by books, nor did he have any literary acquaintances. Schoolmates labelled him a swot. He convinced his parents to finance his membership of several book clubs in Glasgow. The Faber Book of Modern Verse (1936) was a “revelation” to him, he later said. Morgan entered the University of Glasgow in 1937. It was at university that he studied French and Russian, while self-educating in “a good bit of Italian and German” as well. After interrupting his studies to serve in World War II as a non-combatant conscientious objector with the Royal Army Medical Corps, Morgan graduated in 1947 and became a lecturer at the University. He worked there until his retirement as a full professor in 1980. Morgan described ‘CHANGE RULES!’ as 'the supreme graffito’, whose liberating double-take suggests both a lifelong commitment to formal experimentation and his radically democratic left-wing political perspectives. From traditional sonnet to blank verse, from epic seriousness to camp and ludic nonsense; and whether engaged in time-travelling space fantasies or exploring contemporary developments in physics and technology, the range of Morgan’s voices is a defining attribute. Morgan first outlined his sexuality in Nothing Not Giving Messages: Reflections on his Work and Life (1990). He had written many famous love poems, among them “Strawberries” and “The Unspoken”, in which the love object was not gendered; this was partly because of legal problems at the time but also out of a desire to universalise them, as he made clear in an interview with Marshall Walker. At the opening of the Glasgow LGBT Centre in 1995, he read a poem he had written for the occasion, and presented it to the Centre as a gift. In 2002, he became the patron of Our Story Scotland. At the Opening of the Scottish Parliament building in Edinburgh on 9 October 2004, Liz Lochhead read a poem written especially for the occasion by Morgan, titled “Poem for the Opening of the Scottish Parliament”. She was announced as Morgan’s successor as Scots Makar in January 2011. Near the end of his life, Morgan reached a new audience after collaborating with the Scottish band Idlewild on their album The Remote Part. In the closing moments of the album’s final track "In Remote Part/ Scottish Fiction", he recites a poem, “Scottish Fiction”, written specifically for the song. In 2007, Morgan contributed two poems to the compilation Ballads of the Book, for which a range of Scottish writers created poems to be made into songs by Scottish musicians. Morgan’s songs “The Good Years” and “The Weight of Years” were performed by Karine Polwart and Idlewild respectively. Nobel Laureate Seamus Heaney "[paid] formal homage" during a 2005 visit. In later life Morgan was cared for at a residential home as his health worsened. He published a collection in April 2010, months before his death, titled Dreams and Other Nightmares to mark his 90th birthday. Up until his death, he was the last survivor of the canonical 'Big Seven’ (the others being Hugh MacDiarmid, Robert Garioch, Norman MacCaig, Iain Crichton Smith, George Mackay Brown, and Sorley MacLean). On 17 August 2010, Edwin Morgan died of pneumonia in Glasgow, Scotland, at the age of 90. The Scottish Poetry Library made the announcement in the morning. Tributes came from, among others, politicians Alex Salmond and Iain Gray, as well as Carol Ann Duffy, the UK Poet Laureate. Testamentary provisions First Minister of Scotland Alex Salmond’s leader’s speech to the Scottish National Party Conference at Inverness on 22 October 2011 referred to Morgan’s bequest of £918,000 to the party in his will as “transformational”. The next day it was announced that all of the bequest would be used for the party’s independence referendum campaign. Morgan also left £45,000 to a number of friends, former colleagues and charity organisations and set aside another £1 million for the creation of an annual award scheme for young poets in Scotland. Poetry Morgan worked in a wide range of forms and styles, from the sonnet to concrete poetry. His Collected Poems appeared in 1990. He has also translated from a wide range of languages, including Russian, Hungarian, French, Italian, Latin, Spanish, Portuguese, German and Old English (Beowulf). Many of these are collected in Rites of Passage. Selected Translations (1976). His 1952 translation of Beowulf has become a standard translation in America. Morgan was also influenced by the American beat poets, with their simple, accessible ideas and language being prominent features in his work. In 1968 Morgan wrote a poem entitled Starlings In George Square. This poem could be read as a comment on society’s reluctance to accept the integration of different races. Other people have also considered it to be about the Russian Revolution in which “Starling” could be a reference to “Stalin”. Other notable poems include: The Death of Marilyn Monroe (1962) – an outpouring of emotion after the death of one of the world’s most talented women. The Billy Boys (1968) – flashback of the gang warfare in Glasgow led by Billy Fullerton in the Thirties. Glasgow 5 March 1971 – robbery by two youths by pushing an unsuspecting couple through a shop window on Sauchiehall Street In the Snackbar – concise description of an encounter with a disabled pensioner in a Glasgow restaurant. A Good Year for Death (26 September 1977) – a description of five famous people from the world of popular culture who died in 1977 Poem for the Opening of the Scottish Parliament – which was read by Liz Lochhead at the opening ceremony because he was too ill. (9 October 2004) Books Awards and honours * 1972 PEN Memorial Medal (Hungary) * 1982 OBE * 1983 Saltire Society Scottish Book of the Year Award for Poems of Thirty Years * 1985 Soros Translation Award (New York) * 1998 Stakis Prize for Scottish Writer of the Year for Virtual and Other Realities * 2000 Queen’s Gold Medal for Poetry * 2001 Oxford-Weidenfeld Translation Prize for Jean Racine: Phaedra * 2002 The Saltire Society’s Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun award for notable service to Scotland * 2003 Jackie Forster Memorial Award for Culture * 2003 Lifetime Achievement Award for Literature, from the Saltire Society and the Scottish Arts Council * 2007 T. S. Eliot Prize for A Book of Lives. * 2008 Scottish Arts Council Book of the Year Award References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edwin_Morgan_(poet)

Gertrude Stein was born in Allegheny, Pennsylvania, on February 3, 1874, to wealthy German-Jewish immigrants. At the age of three, her family moved first to Vienna and then to Paris. They returned to America in 1878 and settled in Oakland, California. Her mother, Amelia, died of cancer in 1888 and her father, Daniel, died 1891. Stein attended Radcliffe College from 1893 to 1897, where she specialized in Psychology under noted psychologist William James. After leaving Radcliffe, she enrolled at the Johns Hopkins University, where she studied medicine for four years, leaving in 1901. Stein did not receive a formal degree from either institution. In 1903, Stein moved to Paris with Alice B. Toklas, a younger friend from San Francisco who would remain her partner and secretary throughout her life. The couple did not return to the United States for over thirty years. Together with Toklas and her brother Leo, an art critic and painter, Stein took an apartment on the Left Bank. Their home, 27 rue de Fleurus, soon became gathering spot for many young artists and writers including Henri Matisse, Ezra Pound, Pablo Picasso, Max Jacob, and Guillaume Apollinaire. She was a passionate advocate for the "new" in art, her literary friendships grew to include writers as diverse as William Carlos Williams, Djuana Barnes, F. Scott Fitzgerald, James Joyce, and Ernest Hemingway. It was to Hemingway that Stein coined the phrase "the lost generation" to describe the expatriate writers living abroad between the wars. By 1913, Stein's support of cubist painters and her increasingly avant-garde writing caused a split with her brother Leo, who moved to Florence. Her first book, Three Lives, was published in 1909. She followed it with Tender Buttons in 1914. Tender Buttons clearly showed the profound effect modern painting had on her writing. In these small prose poems, images and phrases come together in often surprising ways—similar in manner to cubist painting. Her writing, characterized by its use of words for their associations and sounds rather than their meanings, received considerable interest from other artists and writers, but did not find a wide audience. Sherwood Anderson in the introduction to Geography and Plays (1922) wrote that her writing "consists in a rebuilding, and entire new recasting of life, in the city of words." Among Stein's most influential works are The Making of Americans (1925); How to Write (1931); The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (1933), which was a best-seller; and Stanzas in Meditation and Other Poems [1929-1933] (1956). In 1934, the biographer T. S. Matthews described her as a "solid elderly woman, dressed in no-nonsense rough-spun clothes," with "deep black eyes that make her grave face and its archaic smile come alive." Stein died at the American Hospital at Neuilly on July 27, 1946, of inoperable cancer.

Frederick George Scott (7 April 1861– 19 January 1944) was a Canadian poet and author, known as the Poet of the Laurentians. He is sometimes associated with Canada’s Confederation Poets, a group that included Charles G.D. Roberts, Bliss Carman, Archibald Lampman, and Duncan Campbell Scott. Scott published 13 books of Christian and patriotic poetry. Scott was a British imperialist who wrote many hymns to the British Empire—eulogizing his country’s roles in the Boer Wars and World War I. Many of his poems use the natural world symbolically to convey deeper spiritual meaning. Frederick George Scott was the father of poet F. R. Scott.