Ella Wheeler Wilcox (November 5, 1850– October 30, 1919) was an American author and poet. Her best-known work was Poems of Passion. Her most enduring work was “Solitude”, which contains the lines, “Laugh, and the world laughs with you; weep, and you weep alone”. Her autobiography, The Worlds and I, was published in 1918, a year before her death. Biography Ella Wheeler was born in 1850 on a farm in Johnstown, Wisconsin, east of Janesville, the youngest of four children. The family soon moved north of Madison. She started writing poetry at a very early age, and was well known as a poet in her own state by the time she graduated from high school. Her most famous poem, “Solitude”, was first published in the February 25, 1883 issue of The New York Sun. The inspiration for the poem came as she was travelling to attend the Governor’s inaugural ball in Madison, Wisconsin. On her way to the celebration, there was a young woman dressed in black sitting across the aisle from her. The woman was crying. Miss Wheeler sat next to her and sought to comfort her for the rest of the journey. When they arrived, the poet was so depressed that she could barely attend the scheduled festivities. As she looked at her own radiant face in the mirror, she suddenly recalled the sorrowful widow. It was at that moment that she wrote the opening lines of “Solitude”: Laugh, and the world laughs with you; Weep, and you weep alone. For the sad old earth must borrow its mirth But has trouble enough of its own She sent the poem to the Sun and received $5 for her effort. It was collected in the book Poems of Passion shortly after in May 1883. In 1884, she married Robert Wilcox of Meriden, Connecticut, where the couple lived before moving to New York City and then to Granite Bay in the Short Beach section of Branford, Connecticut. The two homes they built on Long Island Sound, along with several cottages, became known as Bungalow Court, and they would hold gatherings there of literary and artistic friends. They had one child, a son, who died shortly after birth. Not long after their marriage, they both became interested in theosophy, new thought, and spiritualism. Early in their married life, Robert and Ella Wheeler Wilcox promised each other that whoever went first through death would return and communicate with the other. Robert Wilcox died in 1916, after over thirty years of marriage. She was overcome with grief, which became ever more intense as week after week went without any message from him. It was at this time that she went to California to see the Rosicrucian astrologer, Max Heindel, still seeking help in her sorrow, still unable to understand why she had no word from her Robert. She wrote of this meeting: In talking with Max Heindel, the leader of the Rosicrucian Philosophy in California, he made very clear to me the effect of intense grief. Mr. Heindel assured me that I would come in touch with the spirit of my husband when I learned to control my sorrow. I replied that it seemed strange to me that an omnipotent God could not send a flash of his light into a suffering soul to bring its conviction when most needed. Did you ever stand beside a clear pool of water, asked Mr. Heindel, and see the trees and skies repeated therein? And did you ever cast a stone into that pool and see it clouded and turmoiled, so it gave no reflection? Yet the skies and trees were waiting above to be reflected when the waters grew calm. So God and your husband’s spirit wait to show themselves to you when the turbulence of sorrow is quieted. Several months later, she composed a little mantra or affirmative prayer which she said over and over “I am the living witness: The dead live: And they speak through us and to us: And I am the voice that gives this glorious truth to the suffering world: I am ready, God: I am ready, Christ: I am ready, Robert.”. Wilcox made efforts to teach occult things to the world. Her works, filled with positive thinking, were popular in the New Thought Movement and by 1915 her booklet, What I Know About New Thought had a distribution of 50,000 copies, according to its publisher, Elizabeth Towne. The following statement expresses Wilcox’s unique blending of New Thought, Spiritualism, and a Theosophical belief in reincarnation: “As we think, act, and live here today, we built the structures of our homes in spirit realms after we leave earth, and we build karma for future lives, thousands of years to come, on this earth or other planets. Life will assume new dignity, and labor new interest for us, when we come to the knowledge that death is but a continuation of life and labor, in higher planes”. Her final words in her autobiography The Worlds and I: “From this mighty storehouse (of God, and the hierarchies of Spiritual Beings ) we may gather wisdom and knowledge, and receive light and power, as we pass through this preparatory room of earth, which is only one of the innumerable mansions in our Father’s house. Think on these things”. Ella Wheeler Wilcox died of cancer on October 30, 1919 in Short Beach. Poetry A popular poet rather than a literary poet, in her poems she expresses sentiments of cheer and optimism in plainly written, rhyming verse. Her world view is expressed in the title of her poem “Whatever Is—Is Best”, suggesting an echo of Alexander Pope’s “Whatever is, is right,” a concept formally articulated by Gottfried Leibniz and parodied by Voltaire’s character Doctor Pangloss in Candide. None of Wilcox’s works were included by F. O. Matthiessen in The Oxford Book of American Verse, but Hazel Felleman chose no fewer than fourteen of her poems for Best Loved Poems of the American People, while Martin Gardner selected “The Way Of The World” and “The Winds of Fate” for Best Remembered Poems. She is frequently cited in anthologies of bad poetry, such as The Stuffed Owl: An Anthology of Bad Verse and Very Bad Poetry. Sinclair Lewis indicates Babbitt’s lack of literary sophistication by having him refer to a piece of verse as “one of the classic poems, like 'If’ by Kipling, or Ella Wheeler Wilcox’s ‘The Man Worth While.’” The latter opens: It is easy enough to be pleasant, When life flows by like a song, But the man worth while is one who will smile, When everything goes dead wrong. Her most famous lines open her poem “Solitude”: Laugh and the world laughs with you, Weep, and you weep alone; The good old earth must borrow its mirth, But has trouble enough of its own. “The Winds of Fate” is a marvel of economy, far too short to summarize. In full: One ship drives east and another drives west With the selfsame winds that blow. ’Tis the set of the sails, And Not the gales, That tell us the way to go. Like the winds of the sea are the ways of fate; As we voyage along through life, ’Tis the set of a soul That decides its goal, And not the calm or the strife. Ella Wheeler Wilcox cared about alleviating animal suffering, as can be seen from her poem, “Voice of the Voiceless”. It begins as follows: So many gods, so many creeds, So many paths that wind and wind, While just the art of being kind Is all the sad world needs. I am the voice of the voiceless; Through me the dumb shall speak, Till the deaf world’s ear be made to hear The wrongs of the wordless weak. From street, from cage, and from kennel, From stable and zoo, the wail Of my tortured kin proclaims the sin Of the mighty against the frail.

I am an American Patriot, a Believer, and a lover of God and Country. I am a widow, a mother of five children ❤️ and five grandchildren. ❤️ I’m very proud, and honored to have borne such loving, talented and hard working children. Being a Mother was my destiny. Being a writer is also part of my destiny that I truly thank God for. It’s a gift from God It was after my children were grown and left home that I became serious about writing. I have written a book titled (American Poetry and Music) that has been published by Christian Faith Publishing. Which can be purchased on Amazon.com, Barnes and Noble, and Thrift Books.com I get my inspiration from the Creator, and I go under the heading of H.S.I. Which stands for (Holy Spirit Inspiration) Some of these poems on Poeticous.com appear in my book . I am grateful for them allowing me to publish my poems on this site also. I’ve come to love this site very much. All Poems, and Original Music Videos on this site are my own original compositions, and are covered under U.S.Copyright laws.© 2024. For more info -You can find me on (Youtube) and (Facebook). Email no longer public, but if you message me from Facebook or here on Poeticous I’ll give it to you privately. No copyright infringement intended with any Pictures or videos used on these poetry pages. Some videos of artist I enjoy were obtained from Youtube, and some pictures are from Public Domain sites. Mostly they are the property of Poeticous I do not claim rights for any works except my own Original Work. Thank you, Charlotte B. Williams

Walter Whitman (May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist and journalist. A humanist, he was a part of the transition between transcendentalism and realism, incorporating both views in his works. Whitman is among the most influential poets in the American canon, often called the father of free verse. His work was controversial in his time, particularly his 1855 poetry collection Leaves of Grass, which was described as obscene for its overt sensuality.

I am a 27-year-old Christian (the modern term for Follower of the Way). Some bands that I've drawn inspiration from include Demon Hunter, Skillet, Disturbed, Breaking Benjamin, All That Remains and War of Ages. I write lyrical poems, which I have been writing since I was 12 years old. A lot of my lyrics are based on life views and experiences, as well as struggles regarding my Christian faith. I am not ashamed and I will not shy away from admitting to my faith. I hope that my lyrics might open up solutions to readers that can relate to my lyrics. Thank you and God bless.

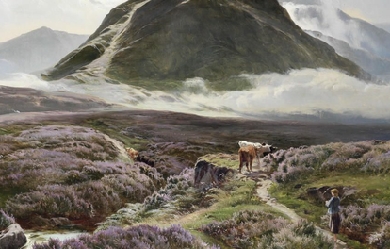

William Wordsworth (7 April 1770 – 23 April 1850) was a major English Romantic poet who, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, helped to launch the Romantic Age in English literature with the 1798 joint publication Lyrical Ballads. Wordsworth's magnum opus is generally considered to be The Prelude, a semiautobiographical poem of his early years which he revised and expanded a number of times. It was posthumously titled and published, prior to which it was generally known as the poem "to Coleridge". Wordsworth was Britain's Poet Laureate from 1843 until his death in 1850. Early life The second of five children born to John Wordsworth and Ann Cookson, William Wordsworth was born on 7 April 1770 in Wordsworth House in Cockermouth, Cumberland—part of the scenic region in northwest England, the Lake District. His sister, the poet and diarist Dorothy Wordsworth, to whom he was close all his life, was born the following year, and the two were baptised together. They had three other siblings: Richard, the eldest, who became a lawyer; John, born after Dorothy, who went to sea and died in 1805 when the ship of which he was Master, the Earl of Abergavenny, was wrecked off the south coast of England; and Christopher, the youngest, who entered the Church and rose to be Master of Trinity College, Cambridge. Their father was a legal representative of James Lowther, 1st Earl of Lonsdale and, through his connections, lived in a large mansion in the small town. Wordsworth, as with his siblings, had little involvement with their father, and they would be distant from him until his death in 1783. Wordsworth's father, although rarely present, did teach him poetry, including that of Milton, Shakespeare and Spenser, in addition to allowing his son to rely on his own father's library. Along with spending time reading in Cockermouth, Wordsworth would also stay at his mother's parents house in Penrith, Cumberland. At Penrith, Wordsworth was exposed to the moors. Wordsworth could not get along with his grandparents and his uncle, and his hostile interactions with them distressed him to the point of contemplating suicide. After the death of their mother, in 1778, John Wordsworth sent William to Hawkshead Grammar School in Lancashire and Dorothy to live with relatives in Yorkshire; she and William would not meet again for another nine years. Although Hawkshead was Wordsworth's first serious experience with education, he had been taught to read by his mother and had attended a tiny school of low quality in Cockermouth. After the Cockermouth school, he was sent to a school in Penrith for the children of upper-class families and taught by Ann Birkett, a woman who insisted on instilling in her students traditions that included pursuing both scholarly and local activities, especially the festivals around Easter, May Day, and Shrove Tuesday. Wordsworth was taught both the Bible and the Spectator, but little else. It was at the school that Wordsworth was to meet the Hutchinsons, including Mary, who would be his future wife. Wordsworth made his debut as a writer in 1787 when he published a sonnet in The European Magazine. That same year he began attending St John's College, Cambridge, and received his B.A. degree in 1791. He returned to Hawkshead for his first two summer holidays, and often spent later holidays on walking tours, visiting places famous for the beauty of their landscape. In 1790, he took a walking tour of Europe, during which he toured the Alps extensively, and visited nearby areas of France, Switzerland, and Italy. Relationship with Annette Vallon In November 1791, Wordsworth visited Revolutionary France and became enthralled with the Republican movement. He fell in love with a French woman, Annette Vallon, who in 1792 gave birth to their child, Caroline. Because of lack of money and Britain's tensions with France, he returned alone to England the next year. The circumstances of his return and his subsequent behaviour raise doubts as to his declared wish to marry Annette, but he supported her and his daughter as best he could in later life. The Reign of Terror estranged him from the Republican movement, and war between France and Britain prevented him from seeing Annette and Caroline again for several years. There are strong suggestions that Wordsworth may have been depressed and emotionally unsettled in the mid-1790s. With the Peace of Amiens again allowing travel to France, in 1802 Wordsworth and his sister, Dorothy, visited Annette and Caroline in Calais. The purpose of the visit was to pave the way for his forthcoming marriage to Mary Hutchinson, and a mutually agreeable settlement was reached regarding Wordsworth's obligations. Afterwards he wrote the poem "It is a beauteous evening, calm and free," recalling his seaside walk with his daughter, whom he had not seen for ten years. At the conception of this poem, he had never seen his daughter before. The occurring lines reveal his deep love for both child and mother. First publication and Lyrical Ballads In his "Preface to Lyrical Ballads", which is called the "manifesto" of English Romantic criticism, Wordsworth calls his poems "experimental." The year 1793 saw Wordsworth's first published poetry with the collections An Evening Walk and Descriptive Sketches. He received a legacy of £900 from Raisley Calvert in 1795 so that he could pursue writing poetry. That year, he met Samuel Taylor Coleridge in Somerset. The two poets quickly developed a close friendship. In 1797, Wordsworth and his sister Dorothy moved to Alfoxton House, Somerset, just a few miles away from Coleridge's home in Nether Stowey. Together, Wordsworth and Coleridge (with insights from Dorothy) produced Lyrical Ballads (1798), an important work in the English Romantic movement. The volume gave neither Wordsworth's nor Coleridge's name as author. One of Wordsworth's most famous poems, "Tintern Abbey", was published in the work, along with Coleridge's "The Rime of the Ancient Mariner". The second edition, published in 1800, had only Wordsworth listed as the author, and included a preface to the poems, which was augmented significantly in the 1802 edition. This Preface to Lyrical Ballads is considered a central work of Romantic literary theory. In it, Wordsworth discusses what he sees as the elements of a new type of poetry, one based on the "real language of men" and which avoids the poetic diction of much 18th-century poetry. Here, Wordsworth gives his famous definition of poetry as "the spontaneous overflow of powerful emotions recollected in tranquility: it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquility." A fourth and final edition of Lyrical Ballads was published in 1805. The Borderers From 1795 to 1797, he wrote his only play, The Borderers, a verse tragedy set during the reign of King Henry III of England when Englishmen of the north country were in conflict with Scottish rovers. Wordsworth attempted to get the play staged in November 1797, but it was rejected by Thomas Harris, theatre manager of Covent Garden, who proclaimed it "impossible that the play should succeed in the representation". The rebuff was not received lightly by Wordsworth, and the play was not published until 1842, after substantial revision. Germany and move to the Lake District Wordsworth, Dorothy and Coleridge travelled to Germany in the autumn of 1798. While Coleridge was intellectually stimulated by the trip, its main effect on Wordsworth was to produce homesickness. During the harsh winter of 1798–99, Wordsworth lived with Dorothy in Goslar, and, despite extreme stress and loneliness, he began work on an autobiographical piece later titled The Prelude. He wrote a number of famous poems, including "The Lucy poems". He and his sister moved back to England, now to Dove Cottage in Grasmere in the Lake District, and this time with fellow poet Robert Southey nearby. Wordsworth, Coleridge and Southey came to be known as the "Lake Poets". Through this period, many of his poems revolve around themes of death, endurance, separation and grief. Marriage and children In 1802, after Wordsworth's return from his trip to France with Dorothy to visit Annette and Caroline, Lowther's heir, William Lowther, 1st Earl of Lonsdale, paid the ₤4, debt owed to Wordsworth's father incurred through Lowther's failure to pay his aide. Later that year, on October 4, Wordsworth married a childhood friend, Mary Hutchinson. Dorothy continued to live with the couple and grew close to Mary. The following year, Mary gave birth to the first of five children, three of whom predeceased William and Mary: * John Wordsworth (18 June 1803 – 1875). * Dora Wordsworth (16 August 1804 – 9 July 1847). * Thomas Wordsworth (15 June 1806 – 1 December 1812). * Catherine Wordsworth (6 September 1808 – 4 June 1812). * William "Willy" Wordsworth (12 May 1810 – 1883). Autobiographical work and Poems in Two Volumes Wordsworth had for years been making plans to write a long philosophical poem in three parts, which he intended to call The Recluse. He had in 1798–99 started an autobiographical poem, which he never named but called the "poem to Coleridge", which would serve as an appendix to The Recluse. In 1804, he began expanding this autobiographical work, having decided to make it a prologue rather than an appendix to the larger work he planned. By 1805, he had completed it, but refused to publish such a personal work until he had completed the whole of The Recluse. The death of his brother, John, in 1805 affected him strongly. The source of Wordsworth's philosophical allegiances as articulated in The Prelude and in such shorter works as "Lines composed a few miles above Tintern Abbey" has been the source of much critical debate. While it had long been supposed that Wordsworth relied chiefly on Coleridge for philosophical guidance, more recent scholarship has suggested that Wordsworth's ideas may have been formed years before he and Coleridge became friends in the mid 1790s. While in Revolutionary Paris in 1792, the 22-year-old Wordsworth made the acquaintance of the mysterious traveller John "Walking" Stewart (1747–1822), who was nearing the end of a thirty-years' peregrination from Madras, India, through Persia and Arabia, across Africa and all of Europe, and up through the fledgling United States. By the time of their association, Stewart had published an ambitious work of original materialist philosophy entitled The Apocalypse of Nature (London, 1791), to which many of Wordsworth's philosophical sentiments are likely indebted. In 1807, his Poems in Two Volumes were published, including "Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood". Up to this point Wordsworth was known publicly only for Lyrical Ballads, and he hoped this collection would cement his reputation. Its reception was lukewarm, however. For a time (starting in 1810), Wordsworth and Coleridge were estranged over the latter's opium addiction. Two of his children, Thomas and Catherine, died in 1812. The following year, he received an appointment as Distributor of Stamps for Westmorland, and the £400 per year income from the post made him financially secure. His family, including Dorothy, moved to Rydal Mount, Ambleside (between Grasmere and Rydal Water) in 1813, where he spent the rest of his life. The Prospectus In 1814 he published The Excursion as the second part of the three-part The Recluse. He had not completed the first and third parts, and never would. He did, however, write a poetic Prospectus to "The Recluse" in which he lays out the structure and intent of the poem. The Prospectus contains some of Wordsworth's most famous lines on the relation between the human mind and nature: My voice proclaims How exquisitely the individual Mind (And the progressive powers perhaps no less Of the whole species) to the external World Is fitted:--and how exquisitely, too, Theme this but little heard of among Men, The external World is fitted to the Mind. Some modern critics[who?] recognise a decline in his works beginning around the mid-1810s. But this decline was perhaps more a change in his lifestyle and beliefs, since most of the issues that characterise his early poetry (loss, death, endurance, separation and abandonment) were resolved in his writings. But, by 1820, he enjoyed the success accompanying a reversal in the contemporary critical opinion of his earlier works. Following the death of his friend the painter William Green in 1823, Wordsworth mended relations with Coleridge. The two were fully reconciled by 1828, when they toured the Rhineland together. Dorothy suffered from a severe illness in 1829 that rendered her an invalid for the remainder of her life. In 1835, Wordsworth gave Annette and Caroline the money they needed for support. The Poet Laureate and other honours Wordsworth received an honorary Doctor of Civil Law degree in 1838 from Durham University, and the same honour from Oxford University the next year. In 1842 the government awarded him a civil list pension amounting to £300 a year. With the death in 1843 of Robert Southey, Wordsworth became the Poet Laureate. He initially refused the honour, saying he was too old, but accepted when Prime Minister Robert Peel assured him "you shall have nothing required of you" (he became the only laureate to write no official poetry). When his daughter, Dora, died in 1847, his production of poetry came to a standstill. Death William Wordsworth died by re-aggravating a case of pleurisy on 23 April 1850, and was buried at St. Oswald's church in Grasmere. His widow Mary published his lengthy autobiographical "poem to Coleridge" as The Prelude several months after his death. Though this failed to arouse great interest in 1850, it has since come to be recognised as his masterpiece. Major works Lyrical Ballads, with a Few Other Poems (1798) * "Simon Lee" * "We are Seven" * "Lines Written in Early Spring" * "Expostulation and Reply" * "The Tables Turned" * "The Thorn" * "Lines Composed A Few Miles above Tintern Abbey" Lyrical Ballads, with Other Poems (1800) * Preface to the Lyrical Ballads * "Strange fits of passion have I known"[14] * "She Dwelt among the Untrodden Ways"[14] * "Three years she grew"[14] * "A Slumber Did my Spirit Seal"[14] * "I travelled among unknown men"[14] * "Lucy Gray" * "The Two April Mornings" * "Nutting" * "The Ruined Cottage" * "Michael" * "The Kitten At Play" Poems, in Two Volumes (1807) * "Resolution and Independence" * "I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud" Also known as "Daffodils" * "My Heart Leaps Up" * "Ode: Intimations of Immortality" * "Ode to Duty" * "The Solitary Reaper" * "Elegiac Stanzas" * "Composed upon Westminster Bridge, September 3, 1802" * "London, 1802" * "The World Is Too Much with Us" * Guide to the Lakes (1810) * The Excursion (1814) * Laodamia (1815, 1845) * The Prelude (1850) References Wikipedia – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Wordsworth

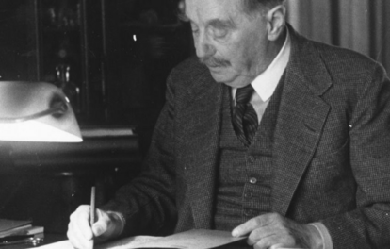

William Carlos Williams (September 17, 1883 – March 4, 1963) was an American poet closely associated with modernism and Imagism. He was also a pediatrician and general practitioner of medicine with a medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine. Williams "worked harder at being a writer than he did at being a physician" but excelled at both. Although his primary occupation was as a family doctor, Williams had a successful literary career as a poet. In addition to poetry (his main literary focus), he occasionally wrote short stories, plays, novels, essays, and translations. He practiced medicine by day and wrote at night. Early in his career, he briefly became involved in the Imagist movement through his friendships with Ezra Pound and H.D. (also known as Hilda Doolittle, another well-known poet whom he befriended while attending the University of Pennsylvania), but soon he began to develop opinions that differed from those of his poet/friends.

Greetings ladies and gentlemen. Welcome to my page. Thank you for taking your time to read my poetry. It's out of the normal styles of writing because it is meant to express my darkest feelings. Please leave your comments if you like what you read. I love to write dark and mysterious types of poetry. Please support me as I continue to write to help me release the emotions I built up inside me. I do hope everyone that reads this respects and understands the personal emotions that comes through my poetry. It is not meant to be altered by any means or taken. It has special meaning to me of what I write and what I express is all true. My current interests and hobbies are Ball Jointed Dolls, Poetry, Art of all forms, Role Playing Games, Playing Guitar, Painting, Drawing, and Writing. I get my inspiration while living in depression through my life, art, and music.

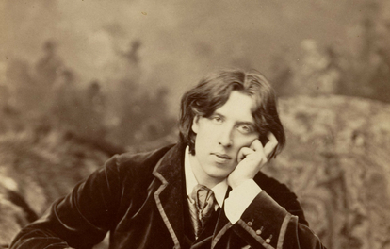

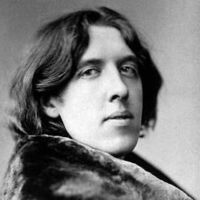

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 1854 – 30 November 1900) was an Irish writer and poet. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of London's most popular playwrights in the early 1890s. Today he is remembered for his epigrams, plays and the circumstances of his imprisonment, followed by his early death. At the turn of the 1890s, he refined his ideas about the supremacy of art in a series of dialogues and essays, and incorporated themes of decadence, duplicity, and beauty into his only novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890). The opportunity to construct aesthetic details precisely, and combine them with larger social themes, drew Wilde to write drama. He wrote Salome (1891) in French in Paris but it was refused a licence. Unperturbed, Wilde produced four society comedies in the early 1890s, which made him one of the most successful playwrights of late Victorian London.

I've always loved to read and wrote as a kid, though I really grasped hold of the art in high school as a release from everything I was going through then. I've had writer's block though for the past couple years and am just trying to get out of the slump now. So please read my work and leave comments if you'd like, even criticisms, I want to get better so have at it if you see there's something I need to work on. And if you follow me or favorite any of my poems, I promise to follow you back! And I won't just click the button, I'll really read your poems and comment on the ones I like. Thanks for reading, hope you enjoy. Oh and by the way, I didn't make my user name rambling woman because of the spoken sense of the word but from the rock n roll sense. Rambling: spreading or winding irregularly in various directions, traveling from place to place, wandering. I use it because I've moved around a lot and I thrive on change.

John Greenleaf Whittier (December 17, 1807 – September 7, 1892) was an American Quaker poet and advocate of the abolition of slavery in the United States. Frequently listed as one of the Fireside Poets, he was influenced by the Scottish poet Robert Burns. Whittier is remembered particularly for his anti-slavery writings as well as his book Snow-Bound.

My name is gary w..... i write 5 styles of poems and i have a different name for each style. 1. <+3 (my symbol)....poems about GOD 2. GAR ....Love poems 3. BONES....Rock poems 4. DIRTY D.O.G. .....Rap poems 5. FUN-K-KID ....funk n dance I have the name of the style with the tiltle now so you can pick your pleasure.

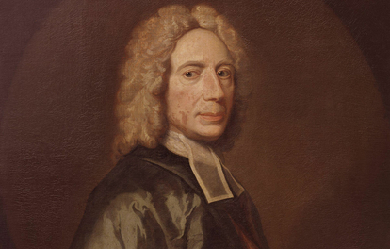

Isaac Watts (17 July 1674– 25 November 1748) was an English Christian minister, hymnwriter, theologian and logician. A prolific and popular hymn writer, his work was part of evangelization. He was recognized as the “Father of English Hymnody”, credited with some 750 hymns. Many of his hymns remain in use today and have been translated into numerous languages.

Judith Arundell Wright (31 May 1915 – 25 June 2000) was an Australian poet, environmentalist and campaigner for Aboriginal land rights. She was born in Armidale, New South Wales. The eldest child of Phillip Wright and his first wife, Ethel, she spent most of her formative years in Brisbane and Sydney. Wright was of Cornish ancestry. After the early death of her mother, she lived with her aunt and then boarded at New England Girls’ School after her father’s remarriage in 1929. After graduating, Wright studied Philosophy, English, Psychology and History at the University of Sydney. At the beginning of World War II, she returned to her father’s station to help during the shortage of labour caused by the war.

Humble, respectful, persistent a few of the words that can be used to describe myself. Kimiko Watson, a young lady of 19 years, a teacher in training. I am a student of the Bethlehem Moravian Teachers' College as our motto says: 'Mihi Cura Futuri' which is to say 'My care if for the Future'. My grandmother is the reason why I write. She has always encourage me by telling me that I can be anything and do anything that i put my mind to. I will continue to believe that any thing that I concieve I can and will achieve.

Alice Walker is a poetese, essayist, and novelist born on February 9, 1944, in Eatonton, Georgia, the eighth and last child of sharecroppers Willie Lee and Minnie Lou Grant Walker. She attended Spelman College and received a B.A. from Sarah Lawrence College. In 1982, she wrote The Color Purple, which won the Pulitzer Prize.

Phillis Wheatley was the first black poet in America to publish a book. She was born around 1753 in West Africa and brought to New England in 1761, where John Wheatley of Boston purchased her as a gift for his wife. Although they brought her into the household as a slave, the Wheatleys took a great interest in Phillis's education. Many biographers have pointed to her precocity; Wheatley learned to read and write English by the age of nine, and she became familiar with Latin, Greek, the Bible, and selected classics at an early age. She began writing poetry at thirteen, modeling her work on the English poets of the time, particularly John Milton, Thomas Gray, and Alexander Pope. Her poem "On the Death of the Rev. Mr. George Whitefield" was published as a broadside in cities such as Boston, New York, and Philadelphia and garnered Wheatley national acclaim. This poem was also printed in London. Over the next few years, she would print a number of broadsides elegizing prominent English and colonial leaders. Wheatley's doctor suggested that a sea voyage might improve her delicate health, so in 1771 she accompanied Nathaniel Wheatley on a trip to London. She was well received in London and wrote to a friend of the "unexpected and unmerited civility and complaisance with which I was treated by all." In 1773, thirty-nine of her poems were published in London as Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral. The book includes many elegies as well as poems on Christian themes; it also includes poems dealing with race, such as the often-anthologized "On Being Brought from Africa to America." She returned to America in 1773. After Mr. and Mrs. Wheatley died, Phillis was left to support herself as a seamstress and poet. It is unclear precisely when Wheatley was freed from slavery, although scholars suggest it occurred between 1774 and 1778. In 1776, Wheatley wrote a letter and poem in support of George Washington; he replied with an invitation to visit him in Cambridge, stating that he would be "happy to see a person so favored by the muses." In 1778, she married John Peters, who kept a grocery store. They had three children together, all of whom died young. Because of the war and the poor economy, Wheatley experienced difficulty publishing her poems. She solicited subscribers for a new volume that would include thirty-three new poems and thirteen letters, but was unable to raise the funds. Phillis Wheatley, who had once been internationally celebrated, died alone in a boarding house in 1784. She was thirty-one years old. Many of the poems for her proposed second volume disappeared and have never been recovered.

Sir William Watson (2 August 1858– 11 August 1935) was an English poet, popular in his time for the celebratory content, and famous for the controversial political content, of his verse. Initially popularly recognised, he was then neglected because of changing tastes. Poet Watson was born in Burley, in present-day West Yorkshire. He was a prolific poet of the 1890s, and a contributor to The Yellow Book, though without “decadent” associations, and on the traditionalist wing of English poetry. His reputation was established in 1891, with the publication of “Wordsworth’s Grave”. On Alfred Tennyson’s death in 1892, he was a strong candidate to be his eulogist, the commission resulting in his “Lachrymae Musarum”. He suffered a breakdown later in 1892 and was passed over for the position of Poet Laureate in favour of Alfred Austin. Watson regained his standing in 1894 with the publication of Odes and other poems, which included “Vita Nuova”, expressing gratitude for his recovery. He courted controversy later in the decade with a attack on Turkey (The Purple East, 1896) and then later again with anti-Boer War poems. After Austin’s death in 1913, Prime Minister Asquith considered him for the laureateship, despite the fact that he had written a cruel pasquil against his wife Margot Asquith ('She is not old, she is not young/ The woman with the serpent’s tongue’); but because of the contentious nature of his political poems, he was again passed over, this time for Robert Bridges. Perhaps in exchange for writing a panegyric of Lloyd George, or perhaps because of his support of the Great War effort, he was awarded a knighthood in 1917. After World War I Watson was largely forgotten. A number of literary men in 1935 issued a public appeal for a fund to support him in his old age; he died the same year. Family Watson married Adeline Maureen Pring in 1909; they had two daughters. Works * The Prince’s Quest and Other Poems (1880) * Epigrams of Art, Life and Nature (1884) * Wordsworth’s Grave and Other Poems (1890) * Poems (1892) * Lachrymae Musarum (1892) * Lyric Love: An Anthology (1892) * Eloping Angels: A Caprice (1893) * The Poems of William Watson (1893) * Excursions in Criticism: Being Some Prose Recreations Of A Rhymer (1893) * Odes and Other Poems (1894) * The Father of the Forest & Other Poems (1895) * The Purple East: A Series Of Sonnets On England’s Desertion of Armenia (1896) * The Year of Shame (1897) * The Hope of the World and Other Poems (1898) * The Collected Poems of William Watson (1899) * Ode on the Coronation of King Edward VII (1902) * Selected Poems (1903) * For England. Poems Written During Estrangement (1904) * New Poems (1909) * Sable and Purple (1910) * The Heralds of the Dawn: A Play in Eight Scenes (1912) * The Muse in Exile (1913) * Pencraft. A Plea For The Older Ways (1916) * The Man Who Saw: and Other Poems Arising out of the War (1917) * Retrogression and Other Poems (1917) * The Superhuman Antagonists and Other Poems (1919) * "Ireland Unfreed. Poems and Verses written in the early months of 1921" (1921) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Watson_(poet)

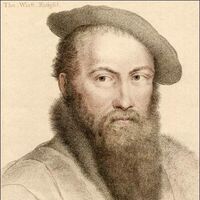

Lady Mary Wroth (18 October 1587– 1651/3) was an English poetess of the Renaissance. A member of a distinguished literary family, Lady Wroth was among the first female British writers to have achieved an enduring reputation. She is perhaps best known for having written The Countess of Montgomery’s Urania, the first extant prose romance by an English woman, and for Pamphilia to Amphilanthus, the second known sonnet sequence by an English woman. Wroth’s works also include Love’s Victory, a pastoral closet drama.

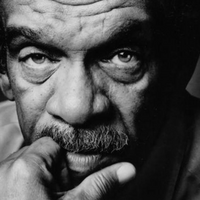

Sir Derek Alton Walcott, KCSL OBE OCC (born 23 January 1930) is a Saint Lucian–Trinidadian poet and playwright. He received the 1992 Nobel Prize in Literature. He is currently Professor of Poetry at the University of Essex. His works include the Homeric epic poem Omeros (1990), which many critics view “as Walcott’s major achievement.” In addition to having won the Nobel, Walcott has won many literary awards over the course of his career, including an Obie Award in 1971 for his play Dream on Monkey Mountain, a MacArthur Foundation “genius” award, a Royal Society of Literature Award, the Queen’s Medal for Poetry, the inaugural OCM Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature, the 2011 T. S. Eliot Prize for his book of poetry White Egrets and the Griffin Trust For Excellence In Poetry Lifetime Recognition Award in 2015. Early life and education Walcott was born and raised in Castries, Saint Lucia, in the West Indies with a twin brother, the future playwright Roderick Walcott, and a sister, Pamela Walcott. His family is of African and European descent, reflecting the complex colonial history of the island which he explores in his poetry. His mother, a teacher, loved the arts and often recited poetry around the house. His father, who painted and wrote poetry, died at age 31 from mastoiditis while his wife was pregnant with the twins Derek and Roderick, who were born after his death. Walcott’s family was part of a minority Methodist community, who felt overshadowed by the dominant Catholic culture of the island established during French colonial rule. As a young man Walcott trained as a painter, mentored by Harold Simmons, whose life as a professional artist provided an inspiring example for him. Walcott greatly admired Cézanne and Giorgione and sought to learn from them. Walcott’s painting was later exhibited at the Anita Shapolsky Gallery in New York City, along with the art of other writers, in a 2007 exhibition named “The Writer’s Brush: Paintings and Drawing by Writers”. He studied as a writer, becoming “an elated, exuberant poet madly in love with English” and strongly influenced by modernist poets such as T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound. Walcott had an early sense of a vocation as a writer. In the poem “Midsummer” (1984), he wrote: At 14, Walcott published his first poem, a Miltonic, religious poem in the newspaper, The Voice of St Lucia. An English Catholic priest condemned the Methodist-inspired poem as blasphemous in a response printed in the newspaper. By 19, Walcott had self-published his two first collections with the aid of his mother, who paid for the printing: 25 Poems (1948) and Epitaph for the Young: XII Cantos (1949). He sold copies to his friends and covered the costs. He later commented, I went to my mother and said, 'I’d like to publish a book of poems, and I think it’s going to cost me two hundred dollars.' She was just a seamstress and a schoolteacher, and I remember her being very upset because she wanted to do it. Somehow she got it—a lot of money for a woman to have found on her salary. She gave it to me, and I sent off to Trinidad and had the book printed. When the books came back I would sell them to friends. I made the money back. The influential Bajan poet Frank Collymore critically supported Walcott’s early work. With a scholarship, he studied at the University College of the West Indies in Kingston, Jamaica. Personal life Derek Walcott married Fay Moston, a secretary, but the marriage lasted only a few years and ended in divorce. Walcott married a second time to Margaret Maillard, who worked as an almoner in a hospital, but that also ended in divorce. In 1976, Walcott then married Norline Metivier, but this marriage also did not last. He has children named Elizabeth, Peter and Anna. Walcott is also known for his passion for traveling to different countries around the world. He splits his time between New York, Boston, and St. Lucia, where he incorporates the influences of different areas into his pieces of work. Career After graduation, Walcott moved to Trinidad in 1953, where he became a critic, teacher and journalist. Walcott founded the Trinidad Theatre Workshop in 1959 and remains active with its Board of Directors. Exploring the Caribbean and its history in a colonialist and post-colonialist context, his collection In a Green Night: Poems 1948–1960 (1962) attracted international attention. His play Dream on Monkey Mountain (1970) was produced on NBC-TV in the United States the year it was published. In 1971 it was produced by the Negro Ensemble Company off-Broadway in New York City; it won an Obie Award that year for “Best Foreign Play”. The following year, Walcott won an OBE from the British government for his work. He was hired as a teacher by Boston University in the United States, where he founded the Boston Playwrights’ Theatre in 1981. That year he also received a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship in the United States. Walcott taught literature and writing at Boston University for more than two decades, publishing new books of poetry and plays on a regular basis and retiring in 2007. He became friends with other poets, including the Russian Joseph Brodsky, who lived and worked in the US after being exiled in the 1970s, and the Irish Seamus Heaney, who also taught in Boston. His epic poem, Omeros (1990), which loosely echoes and refers to characters from The Iliad, has been critically praised “as Walcott’s major achievement.” The book received praise from publications such as The Washington Post and The New York Times Book Review, which chose the book as one of its "Best Books of 1990". Walcott was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1992, the second Caribbean writer to receive the honor after Saint-John Perse, who was born in Guadeloupe, received the award in 1960. The Nobel committee described Walcott’s work as “a poetic oeuvre of great luminosity, sustained by a historical vision, the outcome of a multicultural commitment.” He won an Anisfield-Wolf Book Award for Lifetime Achievement in 2004. His later poetry collections include Tiepolo’s Hound (2000), illustrated with copies of his watercolors; The Prodigal (2004), and White Egrets (2010), which received the T.S. Eliot Prize. In 2009, Walcott began a three-year distinguished scholar-in-residence position at the University of Alberta. In 2010, he became Professor of Poetry at the University of Essex. As a part of St Lucia’s Independence Day celebrations, in February 2016, he became one of the first knights of the Order of Saint Lucia, granting him the title of 'Sir’. Oxford Professor of Poetry candidacy In 2009, Walcott was a leading candidate for the position of Oxford Professor of Poetry. He withdrew his candidacy after reports of documented accusations against him of sexual harassment from 1981 and 1996. (The latter case was settled by Boston University out of court.) When the media learned that pages from an American book on the topic were sent anonymously to a number of Oxford academics, this aroused their interest in the university decisions. Ruth Padel, also a leading candidate, was elected to the post. Within days, The Daily Telegraph reported that she had alerted journalists to the harassment cases. Under severe media and academic pressure, Padel resigned. Padel was the first woman to be elected to the Oxford post, and journalists including Libby Purves, Yasmin Alibhai-Brown, the American Macy Halford and the Canadian Suzanne Gardner attributed the criticism of her to misogyny and a gender war at Oxford. They said that a male poet would not have been so criticized, as she had reported published information, not rumour. Numerous respected poets, including Seamus Heaney and Al Alvarez, published a letter of support for Walcott in The Times Literary Supplement, and criticized the press furore. Other commentators suggested that both poets were casualties of the media interest in an internal university affair, because the story “had everything, from sex claims to allegations of character assassination”. Simon Armitage and other poets expressed regret at Padel’s resignation. Writing Themes Methodism and spirituality have played a significant role from the beginning in Walcott’s work. He commented, “I have never separated the writing of poetry from prayer. I have grown up believing it is a vocation, a religious vocation.” Describing his writing process, he wrote, "the body feels it is melting into what it has seen… the 'I’ not being important. That is the ecstasy... Ultimately, it’s what Yeats says: ‘Such a sweetness flows into the breast that we laugh at everything and everything we look upon is blessed.’ That’s always there. It’s a benediction, a transference. It’s gratitude, really. The more of that a poet keeps, the more genuine his nature." He also notes, “if one thinks a poem is coming on... you do make a retreat, a withdrawal into some kind of silence that cuts out everything around you. What you’re taking on is really not a renewal of your identity but actually a renewal of your anonymity.” Influences Walcott has said his writing was influenced by the work of the American poets, Robert Lowell and Elizabeth Bishop, who were also friends. Playwriting He has published more than twenty plays, the majority of which have been produced by the Trinidad Theatre Workshop and have also been widely staged elsewhere. Many of them address, either directly or indirectly, the liminal status of the West Indies in the post-colonial period. Through poetry he also explores the paradoxes and complexities of this legacy. Essays In his 1970 essay “What the Twilight Says: An Overture”, discussing art and theatre in his native region (from Dream on Monkey Mountain and Other Plays), Walcott reflects on the West Indies as colonized space. He discusses the problems for an artist of a region with little in the way of truly indigenous forms, and with little national or nationalist identity. He states: “We are all strangers here... Our bodies think in one language and move in another". The epistemological effects of colonization inform plays such as Ti-Jean and his Brothers. Mi-Jean, one of the eponymous brothers, is shown to have much information, but to truly know nothing. Every line Mi-Jean recites is rote knowledge gained from the coloniser; he is unable to synthesize it or apply it to his life as a colonised person. Walcott notes of growing up in West Indian culture: “What we were deprived of was also our privilege. There was a great joy in making a world that so far, up to then, had been undefined... My generation of West Indian writers has felt such a powerful elation at having the privilege of writing about places and people for the first time and, simultaneously, having behind them the tradition of knowing how well it can be done—by a Defoe, a Dickens, a Richardson.” Walcott identifies as “absolutely a Caribbean writer”, a pioneer, helping to make sense of the legacy of deep colonial damage. In such poems as “The Castaway” (1965) and in the play Pantomime (1978), he uses the metaphors of shipwreck and Crusoe to describe the culture and what is required of artists after colonialism and slavery: both the freedom and the challenge to begin again, salvage the best of other cultures and make something new. These images recur in later work as well. He writes, “If we continue to sulk and say, Look at what the slave-owner did, and so forth, we will never mature. While we sit moping or writing morose poems and novels that glorify a non-existent past, then time passes us by.” Omeros Walcott’s epic book-length poem Omeros was published in 1990 to critical acclaim. The poem very loosely echoes and references Homer and some of his major characters from The Iliad. Some of the poem’s major characters include the island fishermen Achille and Hector, the retired English officer Major Plunkett and his wife Maud, the housemaid Helen, the blind man Seven Seas (who symbolically represents Homer), and the author himself. Although the main narrative of the poem takes place on the island of St. Lucia, where Walcott was born and raised, Walcott also includes scenes from Brookline, Massachusetts (where Walcott was living and teaching at the time of the poem’s composition), and the character Achille imagines a voyage from Africa onto a slave ship that is headed for the Americas; also, in Book Five of the poem, Walcott narrates some of his travel experiences in a variety of cities around the world, including Lisbon, London, Dublin, Rome, and Toronto. Composed in a variation on terza rima, the work explores the themes that run throughout Walcott’s oeuvre: the beauty of the islands, the colonial burden, the fragmentation of Caribbean identity, and the role of the poet in a post-colonial world. Criticism and praise Walcott’s work has received praise from major poets including Robert Graves, who wrote that Walcott “handles English with a closer understanding of its inner magic than most, if not any, of his contemporaries”, and Joseph Brodsky, who praised Walcott’s work, writing: “For almost forty years his throbbing and relentless lines kept arriving in the English language like tidal waves, coagulating into an archipelago of poems without which the map of modern literature would effectively match wallpaper. He gives us more than himself or 'a world’; he gives us a sense of infinity embodied in the language.” Walcott noted that he, Brodsky, and the Irish poet Seamus Heaney, who all taught in the United States, were a band of poets “outside the American experience”. The poetry critic William Logan critiqued Walcott’s work in a New York Times book review of Walcott’s Selected Poems. While he praised Walcott’s writing in Sea Grapes and The Arkansas Testament, he had mostly negative things to say about Walcott’s poetry, calling Omeros “clumsy” and Another Life “pretentious.”. Finally, he concluded with the faint praise that “No living poet has written verse more delicately rendered or distinguished than Walcott, though few individual poems seem destined to be remembered.” Most reviews of Walcott’s work are more positive. For instance, in The New Yorker review of The Poetry of Derek Walcott, Adam Kirsch had high praise for Walcott’s oeuvre, describing his style in the following manner: By combining the grammar of vision with the freedom of metaphor, Walcott produces a beautiful style that is also a philosophical style. People perceive the world on dual channels, Walcott’s verse suggests, through the senses and through the mind, and each is constantly seeping into the other. The result is a state of perpetual magical thinking, a kind of Alice in Wonderland world where concepts have bodies and landscapes are always liable to get up and start talking. He calls Another Life Walcott’s “first major peak” and analyzes the painterly qualities of Walcott’s imagery from his earliest work through to later books like Tiepolo’s Hound. He also explores the post-colonial politics in Walcott’s work, calling him “the postcolonial writer par excellence.” He calls the early poem “A Far Cry from Africa” a turning point in Walcott’s development as a poet. Like Logan, Kirsch is critical of Omeros which he believes Walcott fails to successfully sustain over its entirety. Although Omeros is the volume of Walcott’s that usual receives the most critical praise, Kirsch, instead believes that Midsummer is his best book. Awards and honours 1969 Cholmondeley Award 1971 Obie Award for Best Foreign Play (for Dream on Monkey Mountain) 1972 Officer of the Order of the British Empire 1981 MacArthur Foundation Fellowship ("genius award") 1988 Queen’s Gold Medal for Poetry 1990 Arts Council of Wales International Writers Prize 1990 W. H. Smith Literary Award (for poetry Omeros) 1992 Nobel Prize in Literature 2004 Anisfield-Wolf Book Award for Lifetime Achievement 2008 Honorary doctorate from the University of Essex 2011 T. S. Eliot Prize (for poetry collection White Egrets) 2011 OCM Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature (for White Egrets) 2015 Griffin Trust For Excellence In Poetry Lifetime Recognition Award 2016 Knight Commander of the Order of Saint Lucia List of works * Works about Derek Walcott in libraries (WorldCat catalog) * Works by Derek Walcott at Open Library Further reading * Baer, William, ed. Conversations with Derek Walcott. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1996. * Baugh, Edward, Derek Walcott: Memory as Vision: Another Life. London: Longman, 1978. * Baugh, Edward, Derek Walcott. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006. * Breslin, Paul, Nobody’s Nation: Reading Derek Walcott. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001. ISBN 0-226-07426-9 * Brown, Stewart, ed., The Art of Derek Walcott. Chester Springs, PA.: Dufour, 1991; Bridgend: Seren Books, 1992. * Burnett, Paula, Derek Walcott: Politics and Poetics. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2001. * Fumagalli, Maria Cristina, The Flight of the Vernacular: Seamus Heaney, Derek Walcott and the Impress of Dante. Amsterdam-New York: Rodopi, 2001. * Fumagalli, Maria Cristina, Agenda 39:1–3 (2002–03), Special Issue on Derek Walcott. Includes Derek Walcott’s Epitaph for the Young (1949) republished here in its entirety. * Fumagalli, Maria Cristina and Patrick, Peter, “Two Healing Narratives: Suffering, Reintegration, and the Struggle of Language”, Small Axe 20 10:2 (2006), pp. 61–79. * Fumagalli, Maria Cristina, “Brushing History Against the Grain: Derek Walcott’s Tiepolo’s Hound”, in Caribbean Perspectives on Modernity: Returning Medusa’s Gaze. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2009. * Gazzoni, Andrea, Epica dell’arcipelago. Il racconto della tribù, Derek Walcott, “Omeros”. Firenze: Le Lettere, 2009. ISBN 88-6087-288-X * Hamner, Robert D., ed. Critical Perspectives on Derek Walcott. Washington, D.C.: Three Continents, 1993. ISBN 0-89410-142-0 * Hamner, Robert D., Derek Walcott. Updated Edition. Twayne’s World Authors Series. TWAS 600. New York: Twayne, 1993. * Heaney, Seamus, “The Murmur of Malvern”, in The Government of the Tongue: The 1986 T. S. Eliot Memorial Lectures and Other Critical Writings. London: Faber and Faber, 1988, pp. 23–29. * King, Bruce, Derek Walcott and West Indian Drama: “Not Only a Playwright But a Company”: The Trinidad Theatre Workshop 1959–1993. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995. * King, Bruce, Derek Walcott, A Caribbean Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. * Lennard, John, “Derek Walcott”, in Jay Parini, ed., World Writers in English. 2 vols, New York & London: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2004, II.721–46. * Morris, Mervyn, “Derek Walcott”, in Bruce King, ed., West Indian Literature, Macmillan, 1979, pp. 144–60. * Parker, Michael and Roger Starkey, eds. New Casebooks: Postcolonial Literatures: Achebe, Ngugi, Desai, Walcott. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Macmillan, 1995. ISBN 0-333-60801-1 * Sinnewe, Dirk, Divided to the Vein? Derek Walcott’s Drama and the Formation of Cultural Identities. Saarbrücken: Königshausen und Neumann, 2001 [Reihe Saarbrücker Beiträge 17]. ISBN 3-8260-2073-1 * Terada, Rei, Derek Walcott’s Poetry: American Mimicry. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1992. * Thieme, John, Derek Walcott. Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 1999. * Walcott, Derek, Dream on Monkey Mountain and Other Plays. New York: Farrar, 1970. ISBN 0-374-50860-7 References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Derek_Walcott

I am a young, aspiring poet who has a great passion for epic writing. Born in South Africa in 1993 during dark economic times I have risen to the occasion and am currently persueing a career in business. My poetry has many hidden meanings and references to my own life and what I deem things to be. I am obsessed with greatness and despise the average. I live a healthy life focused on physical, mental and EQ health and strength. I can not complete this biography because It has barley begun.