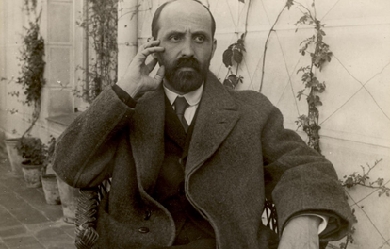

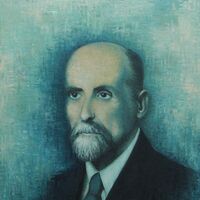

Juan Ramón Jiménez Mantecón (Moguer, Huelva, 23 de diciembre de 1881 – San Juan, Puerto Rico, 29 de mayo de 1958) fue un poeta español, ganador del Premio Nobel de Literatura en 1956, por el conjunto de su obra, designándose como trabajo destacado de la misma, la narración lírica Platero y yo.

Nací en la Ciudad de México en 1967, año del Señor (equivalente al año cero "pepper" de la "beatlemanía"). Desde muy pequeño mis padres me miraban con preocupación, pues no parecía igual que mi hermano o mis primos. No me gustaban los deportes, las pelotas me llamaban la atención sólo por su condición esférica, pues esta forma geométrica es mi favorita y parece ser que la de Dios también, pues las burbujas y los astros tienden a esa figura enigmática. En lugar de correr tras un balón me pasaba la vida leyendo todo lo que llegaba a mi alcance. En casa no abundaban los libros, así que leía historietas o revistas, de las cuales aún conservo una vasta colección, porque aparte de mi extraño hábito de leer también tengo la costumbre de guardarlo todo. Es probable que mi verdadera vocación sea la de museólogo. Afortunadamente para mi, un vecino, padre de dos amigos de la escuela primaria, era un lector voraz y en tardes memorables me dio mis primeras lecciones de Literatura. Me regaló libros, lo que a mis padres no pareció gustarles mucho. La primera obra literaria que leí en mi vida fue "Tom Sawyer" de Mark Twain, después le seguiría "La cabaña del tío Tom" de Harriet Beecher Stowe. Ahí me di cuenta que los libros pueden cambiar al mundo. Con los años, gracias a las becas tuve la oportunidad de comprar más libros y luego descubriría las Bibliotecas que son para mi lo más cercano al Paraíso. Actualmente vivo en una de ellas, la que he podido conformar en décadas. Es fácil que me encuentren en todo lugar donde se vendan libros viejos ¡Amo ese maravilloso olor del papel añoso! A los doce años mis amigos leídos, no conocidos, me urgieron a escribir. Con un terrible miedo a la página en blanco empecé a hacerlo, para terror de mis amados padres que ya se habían resignado a vivir con mis rarezas, hasta me regalaron una máquina de escribir, que desde luego tengo conmigo todavía, es una Olivetti Lettera 32 y ¡Funciona! El tiempo que transcurre muy a nuestro pesar, ha hecho que se acumulen nueve libros de poemas, tres novelas, una obra de teatro y un guión cinematográfico. Todos pecados míos, guardados bajo llave en un lugar donde no pueden hacer daño a nadie. Lo que se mira en Poeticous es una breve muestra del pasado, cada intento de poema tiene el año en que fue escrito. Además de cosas que no me puedo callar, escritas a partir del 2013. Todos desaliñados como su autor. Los versos de cada poema, están como los dientes de Cervantes: "Mal acondicionados y peor puestos". Si han llegado hasta este punto de mi biografía son ustedes un Monumento a la Paciencia, igual que Job. Cordialmente, Alfredo Jiménez G. Eterno aprendiz de poeta.

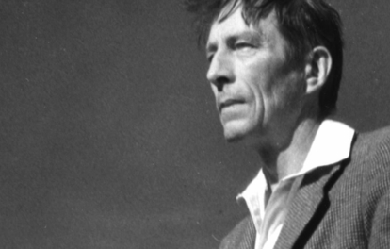

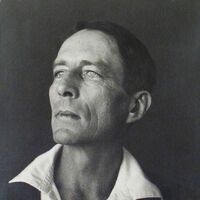

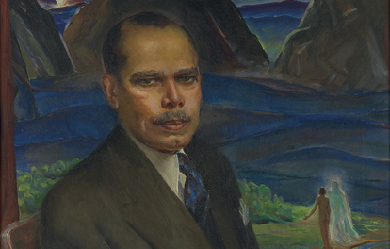

John Robinson Jeffers (January 10, 1887 – January 20, 1962) was an American poet, known for his work about the central California coast. Much of Jeffers' poetry was written in narrative and epic form, but he is also known for his shorter verse and is considered an icon of the environmental movement. Influential and highly regarded in some circles, despite or because of his philosophy of "inhumanism," Jeffers believed that transcending conflict required human concerns to be de-emphasized in favor of the boundless whole. This led him to oppose U.S. participation in World War II, a stand that was controversial at the time. Jeffers was born in Allegheny, Pennsylvania (now part of Pittsburgh), the son of a Presbyterian minister and biblical scholar, Reverend Dr. William Hamilton Jeffers, and Annie Robinson Tuttle. His brother was Hamilton Jeffers, who became a well-known astronomer, working at Lick Observatory. His family was supportive of his interest in poetry. He traveled through Europe during his youth and attended school in Switzerland. He was a child prodigy, interested in classics and Greek and Latin language and literature. At sixteen he entered Occidental College. At school, he was an avid outdoorsman, and active in the school's literary societies. After he graduated from Occidental, Jeffers went to the University of Southern California to study at first literature, and then medicine. He met Una Call Kuster in 1906; she was three years older than he was, a graduate student, and the wife of a Los Angeles attorney. In 1910 he enrolled as a forestry student at the University of Washington in Seattle, a course of study that he abandoned after less than one year, at which time he returned to Los Angeles. Sometime before this, he and Una had begun an affair that became a scandal, reaching the front page of the Los Angeles Times in 1912. After Una spent some time in Europe to quiet things down, the two were married in 1913, and moved to Carmel, California, where Jeffers constructed Tor House and Hawk Tower. The couple had a daughter who died a day after birth in 1914, and then twin sons (Donnan and Garth) in 1916. Una died of cancer in 1950. Jeffers died in 1962; an obituary can be found in the New York Times, January 22, 1962. Poetic career In the 1920s and 1930s, at the height of his popularity, Jeffers was famous for being a tough outdoorsman, living in relative solitude and writing of the difficulty and beauty of the wild. He spent most of his life in Carmel, California, in a granite house that he had built himself called "Tor House and Hawk Tower". Tor is a term for a craggy outcrop or lookout. Before Jeffers and Una purchased the land where Tor House would be built, they rented two cottages in Carmel, and enjoyed many afternoon walks and picnics at the "tors" near the site that would become Tor House. To build the first part of Tor House, a small, two story cottage, Jeffers hired a local builder, Michael Murphy. He worked with Murphy, and in this short, informal apprenticeship, he learned the art of stonemasonry. He continued adding on to Tor House throughout his life, writing in the mornings and working on the house in the afternoon. Many of his poems reflect the influence of stone and building on his life. He later built a large four-story stone tower on the site called Hawk Tower. While he had not visited Ireland at this point in his life, it is possible that Hawk Tower is based on Francis Joseph Bigger's 'Castle Séan' at Ardglass, County Down, which had also in turn influenced Yeats' poets tower, Thoor Ballylee. Construction on Tor House continued into the late 1950s and early 1960s, and was completed by his eldest son. The completed residence was used as a family home until his descendants decided to turn it over to the Tor House Foundation, formed by Ansel Adams, for historic preservation. The romantic Gothic tower was named after a hawk that appeared while Jeffers was working on the structure, and which disappeared the day it was completed. The tower was a gift for his wife Una, who had a fascination for Irish literature and stone towers. In Una's special room on the second floor were kept many of her favorite items, photographs of Jeffers taken by the artist Weston, plants and dried flowers from Shelley's grave, and a rosewood melodeon which she loved to play. The tower also included a secret interior staircase – a source of great fun for his young sons. During this time, Jeffers published volumes of long narrative blank verse that shook up the national literary scene. These poems, including Tamar and Roan Stallion, introduced Jeffers as a master of the epic form, reminiscent of ancient Greek poets. These poems were full of controversial subject matter such as incest, murder and parricide. Jeffers' short verse includes "Hurt Hawks," "The Purse-Seine" and "Shine, Perishing Republic." His intense relationship with the physical world is described in often brutal and apocalyptic verse, and demonstrates a preference for the natural world over what he sees as the negative influence of civilization. Jeffers did not accept the idea that meter is a fundamental part of poetry, and, like Marianne Moore, claimed his verse was not composed in meter, but "rolling stresses." He believed meter was imposed on poetry by man and not a fundamental part of its nature. nitially, Tamar and Other Poems received no acclaim, but when East Coast reviewers discovered the work and began to compare Jeffers to Greek tragedians, Boni & Liveright reissued an expanded edition as Roan Stallion, Tamar and Other Poems (1925). In these works, Jeffers began to articulate themes that contributed to what he later identified as Inhumanism. Mankind was too self-centered, he complained, and too indifferent to the "astonishing beauty of things." Jeffers's longest and most ambitious narrative, The Women at Point Sur (1927), startled many of his readers, heavily loaded as it was with Nietzschean philosophy. The balance of the 1920s and the early 1930s were especially productive for Jeffers, and his reputation was secure. In 1934, he made the acquaintance of the philosopher J Krishnamurti and was struck by the force of Krishnamurti's person. He wrote a poem entitled "Credo" which many feel refers to Krishnamurti. In Cawdor and Other Poems (1928), Dear Judas and Other Poems (1929), Descent to the Dead, Poems Written in Ireland and Great Britain (1931), Thurso's Landing (1932), and Give Your Heart to the Hawks (1933), Jeffers continued to explore the questions of how human beings could find their proper relationship (free of human egocentrism) with the divinity of the beauty of things. These poems, set in the Big Sur region (except Dear Judas and Descent to the Dead), enabled Jeffers to pursue his belief that the natural splendor of the area demanded tragedy: the greater the beauty, the greater the demand. As Euripides had, Jeffers began to focus more on his own characters' psychologies and on social realities than on the mythic. The human dilemmas of Phaedra, Hippolytus, and Medea fascinated him. Many books followed Jeffers' initial success with the epic form, including an adaptation of Euripides' Medea, which became a hit Broadway play starring Dame Judith Anderson. D. H. Lawrence, Edgar Lee Masters, Benjamin De Casseres, and George Sterling were close friends of Jeffers, Sterling having the longest and most intimate relationship with him. While living in Carmel, Jeffers became the focal point for a small but devoted group of admirers. At the peak of his fame, he was one of the few poets to be featured on the cover of Time Magazine. He was also asked to read at the Library of Congress, and was posthumously put on a U.S. postage stamp. Part of the decline of Jeffers' popularity was due to his staunch opposition to the United States' entering World War II. In fact, his book The Double Axe and Other Poems (1948), a volume of poems that was largely critical of U.S. policy, came with an extremely unconventional note from Random House that the views expressed by Jeffers were not those of the publishing company. Soon after, his work was received negatively by several influential literary critics. Several particularly scathing pieces were penned by Yvor Winters, as well as by Kenneth Rexroth, who had been very positive in his earlier commentary on Jeffers' work. Jeffers would publish poetry intermittently during the 1950s but his poetry never again attained the same degree of popularity that it had in the 1920s and the 1930s. Inhumanism Jeffers coined the word inhumanism, the belief that mankind is too self-centered and too indifferent to the "astonishing beauty of things." In the famous poem "Carmel Point," Jeffers called on humans to "uncenter" themselves. In "The Double Axe," Jeffers explicitly described inhumanism as "a shifting of emphasis and significance from man to notman; the rejection of human solipsism and recognition of the trans-human magnificence. ... This manner of thought and feeling is neither misanthropic nor pessimist. ... It offers a reasonable detachment as rule of conduct, instead of love, hate and envy ... it provides magnificence for the religious instinct, and satisfies our need to admire greatness and rejoice in beauty." In The Loyalties of Robinson Jeffers,the first in-depth study of Jeffers not written by one of his circle, poet and critic J. Radcliffe Squires addresses the question of a reconciliation of the beauty of the world and potential beauty in mankind: “Jeffers has asked us to look squarely at the universe. He has told us that materialism has its message, its relevance, and its solace. These are different from the message, relevance, and solace of humanism. Humanism teaches us best why we suffer, but materialism teaches us how to suffer.” Influence His poems have been translated into many languages and published all over the world. Outside of the United States he is most popular in Japan and the Czech Republic. William Everson, Edward Abbey, Gary Snyder, and Mark Jarman are just a few recent authors who have been influenced by Jeffers. Charles Bukowski remarked that Jeffers was his favorite poet. Polish poet Czesław Miłosz also took an interest in Jeffers' poetry and worked as a translator for several volumes of his poems. Jeffers also exchanged some letters with his Czech translator and popularizer, the poet Kamil Bednář. Writer Paul Mooney (1904–1939), son of American Indian authority James Mooney (1861–1921) and collaborator of travel writer Richard Halliburton (1900–1939), "was known always to carry with him (a volume of Jeffers) as a chewer might carry a pouch of tobacco ... and, like Jeffers," writes Gerry Max in Horizon Chasers, "worshipped nature ... (taking) refuge (from the encroachments of civilization) in a sort of chthonian mysticism rife with Greek dramatic elements ..." Jeffers was an inspiration and friend to western U.S. photographers of the early twentieth century, including Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, and Morley Baer. In fact, the elegant book of Baer's photographs juxtaposed with Jeffers' poetry, combines the creative talents of those two residents of the Big Sur coast. Although Jeffers has largely been marginalized in the mainstream academic community over the last thirty years, several important contemporary literary critics, including Albert Gelpi of Stanford University, and poet, critic and NEA chairman Dana Gioia, have consistently cited Jeffers as a formidable presence in modern literature. His poem "The Beaks of Eagles" was made into a song by The Beach Boys on their album Holland (1973). Two lines from Jeffers' poem "We Are Those People" are quoted toward the end of the 2008 film Visioneers. Several lines from Jeffers' poem "Wise Men in Their Bad Hours" ("Death's a fierce meadowlark: but to die having made / Something more equal to the centuries / Than muscle and bone, is mostly to shed weakness.") appear in Christopher McCandless' diary. Robinson Jeffers is mentioned in the 2004 film I Heart Huckabees by the character Albert Markovski played by Jason Schwartzman, when defending Jeffers as a nature writer against another character's claim that environmentalism is socialism. Markovski says, "Henry David Thoreau, Robinson Jeffers, the National Geographic Society...all socialists?" Further reading and research The largest collections of Jeffers' manuscripts and materials are in the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin and in the libraries at Occidental College, the University of California, and Yale University. A collection of his letters has been published as The Selected Letters of Robinson Jeffers, 1887–1962 (1968). Other books of criticism and poetry by Jeffers are: Poetry, Gongorism and a Thousand Years (1949), Themes in My Poems (1956), Robinson Jeffers: Selected Poems (1965), The Alpine Christ and Other Poems (1974), What Odd Expedients" and Other Poems (1981), and Rock and Hawk: A Selection of Shorter Poems by Robinson Jeffers (1987). Stanford University Press recently released a five-volume collection of the complete works of Robinson Jeffers. In an article titled, "A Black Sheep Joins the Fold", written upon the release of the collection in 2001, Stanford Magazine commented that it was remarkable that, due to a number of circumstances, "there was never an authoritative, scholarly edition of California’s premier bard" until the complete works published by Stanford. Biographical studies include George Sterling, Robinson Jeffers: The Man and the Artist (1926); Louis Adamic, Robinson Jeffers (1929); Melba Bennett, Robinson Jeffers and the Sea (1936) and The Stone Mason of Tor House (1966); Radcliffe Squires, The Loyalties of Robinson Jeffers (1956); Edith Greenan, Of Una Jeffers (1939); Mabel Dodge Luhan, Una and Robin (1976; written in 1933); Ward Ritchie, Jeffers: Some Recollections of Robinson Jeffers (1977); and James Karman, Robinson Jeffers: Poet of California (1987). Books about Jeffers's career include L. C. Powell, Robinson Jeffers: The Man and His Work (1940; repr. 1973); William Everson, Robinson Jeffers: Fragments of an Older Fury (1968); Arthur B. Coffin, Robinson Jeffers: Poet of Inhumanism (1971); Bill Hotchkiss, Jeffers: The Sivaistic Vision (1975); James Karman, ed., Critical Essays on Robinson Jeffers (1990); Alex Vardamis The Critical Reputation of Robinson Jeffers (1972); and Robert Zaller, ed., Centennial Essays for Robinson Jeffers (1991). The Robinson Jeffers Newsletter, ed. Robert Brophy, is a valuable scholarly resource. In a rare recording, Jeffers can be heard reading his "The Day Is A Poem" (September 19, 1939) on Poetry Speaks – Hear Great Poets Read Their Work from Tennyson to Plath, Narrated by Charles Osgood (Sourcebooks, Inc., c2001), Disc 1, #41; including text, with Robert Hass on Robinson Jeffers, pp. 88–95. Jeffers was also on the cover of Time – The Weekly Magazine, April 4, 1932 (pictured on p. 90. Poetry Speaks). Jeffers Studies, a journal of research on the poetry of Robinson Jeffers and related topics, is published semi-annually by the Robinson Jeffers Association. Bibliography * Flagons and Apples. Los Angeles: Grafton, 1912. * Californians. New York: Macmillan, 1916. * Tamar and Other Poems. New York: Peter G. Boyle, 1924. * Roan Stallion, Tamar, and Other Poems. New York: Boni and Liveright, 1925. * The Women at Point Sur. New York: Liveright, 1927. * Cawdor and Other Poems. New York: Liveright, 1928. * Dear Judas and Other Poems. New York: Liveright, 1929. * Thurso's Landing and Other Poems. New York: Liveright, 1932. * Give Your Heart to the Hawks and other Poems. New York: Random House, 1933. * Solstice and Other Poems. New York: Random House, 1935. * Such Counsels You Gave To Me and Other Poems. New York: Random House, 1937. * The Selected Poetry of Robinson Jeffers. New York: Random House, 1938. * Be Angry at the Sun. New York: Random House, 1941. * Medea. New York: Random House, 1946. * The Double Axe and Other Poems. New York: Random House, 1948. * Hungerfield and Other Poems. New York: Random House, 1954. * The Beginning and the End and Other Poems. New York: Random House, 1963. * Robinson Jeffers: Selected Poems. New York: Vintage, 1965. * Stones of the Sur. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robinson_Jeffers

I'm not scared of toasters, but it's ok if you are. Fearing things that can hurt you is natural. Unfortunately, I'm a sucker for huckleberry jam on toast, so I take that risk every day. I don't have forever, and life isn't always enjoyable, but have you TRIED huckleberry jam? It's hard to hate the world when you have that slightly chunky, gelatinous concentration on a piece of glutenous (or should I say gluttonous) bread.

Porfirio Barba-Jacob (Seudónimo de Miguel Ángel Osorio Benítez; Santa Rosa de Osos, 1883 - México, 1942) Poeta y periodista colombiano polémico e influyente, cuya obra suele clasificarse dentro de un modernismo ecléctico. En su primera juventud fue un sencillo maestro de escuela rural en Antioquia, donde fundó la campesina Escuela de la Iniciación. A los 23 años, habiéndose trasladado de Antioquia a Barranquilla, comenzó a publicar sus primeros poemas, entre ellos la Parábola del retorno, muy conocida en Colombia. Después, con algunos amigos trovadores colombianos, se trasladó a México.

Víctor Lidio Jara Martínez (1932 – 1973), conocido simplemente como Víctor Jara, fue un músico, cantautor, profesor, director de teatro, activista político y miembro del Partido Comunista de Chile. La figura de Víctor Jara es un referente internacional de la canción protesta y de cantautor. Debido a su militancia comunista, fue torturado y asesinado en el antiguo Estadio Chile (actual Estadio Víctor Jara como homenaje) por fuerzas represivas de la dictadura de Augusto Pinochet, poco después del Golpe de Estado que derrocó al gobierno de Salvador Allende, el 11 de septiembre de 1973. Infancia Víctor Jara nació el 28 de septiembre de 1932 en San Ignacio, localidad de la provincia de Ñuble, Región del Biobío en Chile, en el seno una familia de padres campesinos, originarios de la pequeña localidad de Quiriquina, perteneciente por entonces al Departamento de Bulnes, actualmente San Ignacio, y caracterizada por un arraigado folclore. Su padre, Manuel Jara, se dedicaba a las tareas del campo, y su madre, Amanda Martínez (originaria del sur de Chile), además de dedicarse a las labores domésticas, tocaba la guitarra y cantaba. Tenía, además, cuatro hermanos: María, Georgina ("Coca"), Eduardo ("Lalo") y Roberto, el menor. Por causa de las necesidades familiares, Víctor se vio obligado desde niño a ayudar a la familia en los trabajos del campo. Influenciado por su madre, tomó también contacto a temprana edad con la música, además de asistir al colegio.[cita requerida] Juventud La familia se trasladó a la población Los Nogales, donde coincidieron con Julio y Humberto Morgado, compañeros de Víctor en la escuela primaria. La familia Morgado proporcionó a Víctor, que abandonó sus estudios, un trabajo en una fábrica de muebles, ayudando al padre de sus compañeros en su trabajo de transportista. Cuando contaba con 15 años, falleció su madre, lo que significó la disolución del núcleo familiar.[cita requerida] Por consejo de un sacerdote, ingresó en el seminario de la Congregación del Santísimo Redentor, en San Bernardo. Víctor recordó así su decisión: "Para mí fue una decisión muy importante ingresar en el seminario. Al pensarlo ahora, desde una perspectiva más dura, creo que lo hice por razones íntimas y emocionales, por la soledad y la desaparición de un mundo que hasta entonces había sido sólido y perdurable, simbolizado por un hogar y el amor de mi madre. Yo ya estaba relacionado con la Iglesia, y en aquel momento busqué refugio en ella. Entonces pensaba que ese refugio me guiaría hacia otros valores y me ayudaría a encontrar un amor diferente y más profundo que quizá compensaría la ausencia de amor humano. Creía que hallaría ese amor en la religión, dedicándome al sacerdocio." [cita requerida] Dos años después de su ingreso, abandonó el seminario al comprobar su falta de vocación, tras haber practicado allí el canto gregoriano y la interpretación de la liturgia. Tras dejar el seminario, prestó el servicio militar. Comienzos artísticos A los 21 años, después de cumplir el servicio militar, ingresó en el coro de la Universidad de Chile, participando en el montaje de Carmina Burana comenzando así su trabajo de investigación y recopilación folclórica. Con 24 años se unió a una compañía teatral, la "Compañía de Mimos de Noisvander", e inició los estudios de actuación y dirección en la Escuela de Teatro de la Universidad de Chile. A modo de anécdota, como no tenía donde dormir, pernoctaba en inmediaciones de la escuela, muestra del sacrificio que para él significó dedicar su vida al arte. En 1957 ingresó en el Conjunto folclórico Cuncumén y conoció a la artista plástica y cantautora Violeta Parra, quien lo animó a continuar su carrera musical. Con 27 años, en 1959 dirigió su primera obra de teatro: Parecido a la felicidad, de Alejandro Sieveking, haciendo giras por varios países latinoamericanos. Como solista del grupo folclórico grabó su primer disco, un sencillo que contenía dos villancicos chilenos. Al año siguiente participó como asistente de dirección en el montaje de la obra teatral La viuda de Apablaza, de Germán Luco Cruchaga, cuyo director era Pedro de la Barra, y dirigió la obra La mandrágora, de Machiavello. En 1961, y como director artístico del grupo Cuncumén viajó por Holanda, Francia, Unión Soviética, Checoslovaquia, Polonia, Rumania y Bulgaria. En 1961 compuso su primera canción, Paloma quiero contarte y continuó trabajando como asistente de dirección en el montaje de La madre de los conejos, de Alejandro Sieveking. Al año siguiente, en 1962, dirigiría para el Instituto de Teatro de la Universidad de Chile (Ituch) la obra Ánimas de día claro, también de Sieveking. Grabó con el grupo Cuncumén el LP Folclore chileno, con dos canciones propias: Paloma quiero contarte y La canción del minero, en la época en que comenzó a desempeñar la función de director en la Academia de Folclore de la Casa de la Cultura de Ñuñoa, labor que desempeñaría hasta 1968. Desde esa misma época, y hasta 1970, formó parte del equipo estable de directores del Ituch, además de trabajar, entre 1964 y 1967, como profesor de actuación en la universidad. También llevó a cabo, bien como asistente de dirección o como director, varios montajes, entre ellos uno para el canal de televisión de la Universidad de Chile, realizando además una gira por Argentina, Uruguay y Paraguay con la obra Ánimas de día claro, de Alejandro Sieveking. En 1963 fue asistente de dirección de Atahualpa del Cioppo en el montaje de El círculo de tiza caucasiano, de Bertolt Brecht, para el Ituch. Compaginó su actividad teatral con la composición musical, y en 1965 dirigió la obra La remolienda, de Sieveking, así como el montaje de La maña, de Ann Jellicoe, por las que recibe el premio Laurel de Oro como mejor director y el Premio de la Crítica del Círculo de Periodistas a la mejor dirección por La Maña. Cantautor "El amor a la justicia como instrumento del equilibrio para la dignidad del hombre", oración de Víctor Jara. Ejerció como director artístico del grupo Quilapayún entre los años 1966 y 1969, y hasta 1970 actuó como solista en la "Peña de los Parra". Sin abandonar el teatro, en 1966 grabó su primer LP como solista, Víctor Jara, editado por la empresa discográfica Arena. Con la empresa filial chilena de Emi-Odeón grabaría el año siguiente Canciones folclóricas de América, junto a Quilapayún. En 1969 llevó a cabo el montaje de Antígona, de Sófocles, para la Compañía de la Escuela de Teatro de la Universidad Católica. Con la canción Plegaria a un labrador ganó el primer premio en el primer festival de la Nueva Canción Chilena, y viajó a Helsinki para participar en un acto mundial en protesta por la Guerra de Vietnam, además de Pongo en tus manos abiertas. A este álbum pertenece el tema Preguntas por Puerto Montt, inspirado en la Masacre de Pampa Irigoin (Puerto Montt), en la que murieron 11 personas (incluyendo un niño), bajo la represión policial del gobierno de Eduardo Frei Montalva. En esa canción critica duramente al ministro de Interior Edmundo Pérez Zújovic, luego asesinado por el grupo extremista Vanguardia Organizada del Pueblo (VOP) (8 de junio de 1971): "Usted debe responder, señor Pérez Zújovic, porqué al pueblo indefenso, contestaron con fusil. Señor Pérez, su conciencia la enterró en un ataúd y no limpiará sus manos toda la lluvia del sur." En 1970 participó en Berlín en la Conversación Internacional de Teatro y en Buenos Aires en el I Congreso de Teatro Latinoamericano. En esa época participa en la campaña electoral de Unidad Popular y presenta el álbum Canto libre. Al asumir Salvador Allende como Presidente de la República de Chile, Jara es nombrado Embajador Cultural y en 1971 compone la música, junto con Celso Garrido Lecca, de la obra de ballet Los siete estados, de Patricio Bunster, para el Ballet Nacional de Chile. Junto a Isabel Parra e Inti-Illimani entra en el Departamento de Comunicaciones de la Universidad Técnica del Estado. Con la discográfica Dicap edita el disco El derecho de vivir en paz, que le vale el premio Laurel de Oro a la mejor composición del año. Trabaja como compositor de música para continuidad en la Televisión Nacional de Chile de 1972 a 1973, e investiga y recopila testimonios en Herminda de la Victoria, en los cuales basaría su disco La población. También viaja a la URSS y a Cuba, y dirige el homenaje a Pablo Neruda por la obtención del Premio Nobel. Los campesinos de Ránquil lo invitan a la realización de una obra musical sobre el lugar, y dentro de su compromiso social, toma parte en los trabajos voluntarios para impedir la paralización del país causada por una huelga de camioneros. Ese mismo compromiso lo llevará en 1973 a realizar diferentes actos, participando en la campaña electoral para las elecciones al parlamento a favor de los candidatos de la Unidad Popular y, respondiendo a un llamado de Pablo Neruda, participa dirigiendo y cantando en un ciclo de programas de televisión contra la guerra y el fascismo. Trabaja simultáneamente en la preparación de varios álbumes que no podría grabar, pero graba el álbum Canto por travesura, último de los que realizó. Tortura y asesinato El golpe de Estado encabezado por el general Augusto Pinochet contra el presidente Salvador Allende, el 11 de septiembre de ese año, lo sorprende en la Universidad Técnica del Estado, y es detenido junto a profesores y alumnos. Lo llevan al Estadio Chile (actualmente "estadio Víctor Jara", lugar en el que hay una placa en su honor con su último poema),1donde permanece detenido varios días. Según numerosos testimonios, lo torturan durante horas, le golpean las manos hasta rompérselas con la culata de un revólver y finalmente lo acribillan el día 16 de septiembre. El cuerpo es encontrado el día 19 del mismo mes. Estando preso escribió su último poema y testimonio Somos cinco mil, también conocido como Estadio Chile. Somos cinco mil en esta pequeña parte de la ciudad. Somos cinco mil ¿Cuántos seremos en total en las ciudades y en todo el país? Solo aquí diez mil manos siembran y hacen andar las fábricas. ¡Cuánta humanidad con hambre, frío, pánico, dolor, presión moral, terror y locura! Reconocimiento del asesinato En 1990, la denominada Comisión de Verdad y Reconciliación determinó que Víctor Jara fue acribillado con 44 disparos el 16 de septiembre de 1973 en el Estadio Chile y que fue arrojado a unos matorrales en los alrededores del Cementerio Metropolitano, ubicado a orillas de la Carretera 5 Sur. Luego fue llevado al depósito de cadáveres, donde le asignaron las siglas "NN", y donde más tarde sería identificado por su esposa, la coreógrafa de origen inglés Joan Turner. Sus restos fueron enterrados en el Cementerio General de Santiago de Chile. La viuda, años después, mencionaría que el diario chileno La Segunda, al día siguiente al Golpe de Estado, publicó un párrafo que daba a entender que Jara había muerto sin violencia y que su sepelio había sido de carácter privado. Como homenaje a su memoria, 30 años después del golpe militar, en septiembre del 2003 se puso su nombre al hasta entonces denominado Estadio Chile. El 29 de mayo de 2009, la Corte de Apelaciones de Santiago de Chile ratificó el encarcelamiento del ex soldado del ejército José Paredes Márquez, quien fue acusado del asesinato del cantante. En el momento de la ejecución, Paredes Márquez era un recluta del ejército chileno que tenía 18 años.6 Éste declaró que cuando le tirotearon, Víctor Jara ya había fallecido, debido a un disparo en la cabeza efectuado por un oficial de ejército,7 por lo que el juez encargado del caso ordenó la exhumación de sus restos, con el fin de practicarle una segunda autopsia. En junio de 2009 se exhumaron por orden judicial los restos mortales de Víctor Jara para la realización de un estudio que determinara las causas precisas de la muerte. El 27 de noviembre de ese mismo año la Fundación Víctor Jara hizo público el resultado del estudio. Según el mismo, efectuado por el Servicio Médico Legal (SML) de Chile y ratificado por el Instituto Genético de Innsbruck, el artista murió a consecuencia de «múltiples fracturas por heridas de bala que provocaron un shock hemorrágico en un contexto de tipo homicida» y que fue golpeado y torturado durante su paso por el Estadio Chile, donde estuvo detenido. Se destaca que se han encontrado más de 30 lesiones óseas producto de fracturas provocadas por heridas de proyectil y otras provocadas por objetos contundentes, diferentes a las heridas de bala. Estudio judicial del asesinato Bajo la autoridad del juez Juan Eduardo Fuentes Belmar, en 2007 se realizó una investigación sobre el asesinato de Víctor Jara destinada a buscar responsabilidades por el mismo. Se acusó de los hechos a José Paredes, autor confeso de algunos de los disparos (aunque después se retractó), y al coronel retirado Mario Manríquez, que era el responsable del centro de detención, quedando fuera del procesamiento como responsable de la orden del asesinato, señalado por los familiares de Víctor Jara, así como por organizaciones defensoras de los derechos humanos. También fue señalado, por compañeros de cautiverio del músico, el ex coronel Edwin Dimter Bianchi, conocido como "El Príncipe". Entierro y homenaje Una vez finalizados los estudios forenses en noviembre de 2009, se realizó un acto de homenaje, del 3 al 5 de diciembre, permaneciendo los restos mortales del artista en la sede de la Fundación Víctor Jara y, posteriormente, recibieron sepultura en el Cementerio General de Santiago de Chile en una procesión fúnebre que congregó a más de 12.000 personas. A diferencia del entierro, prácticamente clandestino, llevado a cabo en 1973, después de su asesinato, el sepelio del día 5 de diciembre de 2009, 36 años después de su asesinato, fue abierto y público. Los actos de homenaje y entierro, como señaló Gloria Konig, directora ejecutiva de la Fundación Víctor Jara, constituyeron una demanda de «verdad y justicia para el artista y para todos los detenidos, desaparecidos y ejecutados políticos de Chile». Carta de Ángel Parra a Víctor Jara La expresión de los hechos ocurridos en Chile a raíz del golpe de estado quedan redactados en la carta escrita por Ángel Parra en París, durante su exilio, en diciembre de 1987. Su obra Teatro Entre las obras dirigidas por Víctor Jara se encuentran: * 1959 - Parecido a la felicidad, de Alejandro Sieveking. * 1960 - La mandrágora, de Maquiavelo. * 1962 - Ánimas de día claro, de Alejandro Sieveking. *1963 - Los invasores, de Egon Wolff. * 1963 - Parecido a la felicidad, de Alejandro Sieveking. * 1963 - Dúo, de Raúl Ruiz. * 1964 - Ánimas de día claro, de Alejandro Sieveking. * 1965 - La remolienda, de Alejandro Sieveking. * 1965 - La maña, de Ann Jellicoe. * 1966 - La casa vieja, de "Abelardo Estorino". Obras en las que asistió a la dirección: * 1960 - La viuda de Apablaza, de Germán Luco Cruchaga, dirigida por Pedro de la Barra. * 1961 - La madre de los conejos, de Alejandro Sieveking, dirigida por Agustín Siré. * 1963 - El círculo de tiza, de Bertolt Brecht, dirigida por Atahualpa del Cioppo. * 1966 - Marat Sade, de Peter Weiss, dirigida por William Oliver. Discografía Discos de estudio * 1966 - Víctor Jara * 1967 - Canciones folclóricas de América (con Quilapayún) * 1967 - Víctor Jara * 1969 - Pongo en tus manos abiertas... * 1970 - Canto libre * 1971 - El derecho de vivir en paz * 1972 - La población * 1973 - Canto por travesura Discos grabados en vivo * 1978 - El recital * 1996 - Víctor Jara en México * 1996 - Víctor Jara habla y canta Ediciones póstumas * 1974 - Víctor Jara / Manifiesto * 1975 - Víctor Jara. Presente * 1975 - Víctor Jara. Últimas canciones * 1979 - Víctor Jara * 1984 - An Unfinished Song * 1990 - Canto a lo Humano * 1992 - Todo Víctor Jara * 1997 - Víctor Jara presente. Colección “Haciendo historia” * 2001 - Víctor Jara habla y canta * 2001 - Manifiesto * 2001 - Antología musical * 2001 - 1959-1969 Obra relacionada con Víctor Jara Víctor Jara ha inspirado a múltiples artistas hispanohablantes contemporáneos, y en particular a músicos. Por ejemplo la carta póstuma de Ángel Parra, con fuerte contenido político. También reciben su nombre distintas edificaciones a lo largo de Chile; entre ellas, la más simbólica y relevante es el estadio donde fue asesinado, antiguo Estadio Chile, que actualmente se llama Estadio Víctor Jara. Desde el año 1993, la Fundación Víctor Jara, una organización sin fines de lucro, se ha hecho cargo de los derechos de autor de Víctor, para organizar y difundir de manera apropiada y artísticamente válida los distintos trabajos del director y cantautor, ya sea por iniciativa propia o por iniciativas de terceros. El teatro del municipio de Santa Lucía de Tirajana en la isla de Gran Canaria (Canarias, España) recibe el nombre de Víctor Jara en honor al cantautor chileno. Canciones en homenaje a Víctor Jara Véase también: Anexo:Canciones homenaje a Víctor Jara. Existe una enorme cantidad de agrupaciones musicales y cantautores de los más diversos estilos que han escrito canciones ya sea mencionando a Víctor Jara, o hablando de su vida. Esta lista podría crecer enormemente, pues en la actualidad no se detiene, y agrupaciones tanto nuevas como ya reconocidas continúan haciendo homenajes de Víctor. Versiones Existe una enorme cantidad de cantautores y agrupaciones musicales que han interpretado temas de Víctor Jara. Algunos de ellos lo conocieron en vida, mientras que otros fueron influenciados claramente por éste. Adicionalmente, existen otras agrupaciones que, tocando otros estilos musicales, toman sus letras o arreglos para componer sus propias versiones.[cita requerida] Películas y documentales * El tigre saltó y mató, pero morirá… morirá…. Director: Santiago Álvarez – Cuba (1973) * Compañero: Víctor Jara of Chile. Directores: Stanley Foreman/Martin Smith (documental) – Gran Bretaña (1974) * Il Pleut sur Santiago, starring André Dussollier. Director: Helvio Soto – Francia (1976) * April Hat 30 Tage. Director: Gunther Scholz - Alemania (1978) * El cantor. Director: Dean Reed; escritor: Wolfgang Ebeling – Alemania (1978) * Freedom Highway: Songs that Shaped a Century. Director: Philip King – Estados Unidos (2001) * El derecho de vivir en paz - Documental DVD - Chile 1999. Director. Carmen Luz Parot. * La tierra de las 1000 músicas [Episodio 6: La protesta]. Directores: Luis Miguel/González Cruz – España (2005)11 * La funa de Víctor Jara. Directores: Nélida D. Ruiz de los Paños- Cristian Villablanca R. Documental en coproducción con TV3 Cataluña (España), Paral·lel 40, Cristian Villablanca y Nélida D. Ruiz de los Paños - España/Chile (2007). * An Unfinished Song (Una canción inacabada). Directores: Emma Thompson. Actores: Antonio Banderas. Inspirada en el libro de Joan Jara Víctor Jara, un canto truncado. Referencias Wikipedia-http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/V%C3%ADctor_Jara

Ben Jonson (originally Benjamin Jonson; c. 11 June 1572 – 6 August 1637) was an English playwright, poet, and literary critic of the seventeenth century, whose artistry exerted a lasting impact upon English poetry and stage comedy. He popularised the comedy of humours. He is best known for the satirical plays Every Man in His Humour (1598), Volpone, or The Foxe (1605), The Alchemist (1610), and Bartholomew Fayre: A Comedy (1614), and for his lyric poetry; he is generally regarded as the second most important English dramatist, after William Shakespeare, during the reign of James I. He was a classically educated, well-read, and cultured man of the English Renaissance with an appetite for controversy (personal and political, artistic and intellectual) whose cultural influence was of unparalleled breadth upon the playwrights and the poets of the Jacobean era (1603–1625) and of the Caroline era (1625–1642).

Me gusta la poesía y escribo... poemas que vierten en el papel sentimientos a lo largo de mi vida. Distintos uno del otro pero surgidos de la misma raíz. Pétalos vueltos inmarcesibles por el verso. Y que para que el viento no se lleve: las coso juntas. Espero que sean de su agrado. Por leer, muchas gracias.

José Alfredo Jiménez Sandoval' (Dolores Hidalgo, Guanajuato, México, 19 de enero de 1926 - Ciudad de México, 23 de noviembre de 1973) fue un cantante y compositor mexicano. Es considerado el mejor cantautor de música ranchera de todos los tiempos. Falleció en la Ciudad de México, el 23 de noviembre de 1973 a la edad de 47 años, a consecuencia de cirrosis hepática. Sus restos descansan en el cementerio de su pueblo natal, tal y como expresó en su canción "Caminos de Guanajuato". Fue el poeta de la desolación marginal y la lírica cantinera. “De veras, muchas gracias por haberme aguantado tanto tiempo, desde 1947 hasta 1972, y yo siento que todavía me quieren. ¿Saben por qué? Porque yo he ganado dinero; el dinero pues no sé ni por dónde lo tiré, pero sus aplausos esos los traigo aquí adentro, y ya no me los quita nadie, esos se van conmigo hasta la muerte”

Erica Jong (née Mann; born March 26, 1942) is an American novelist and poet, known particularly for her 1973 novel Fear of Flying. The book became famously controversial for its attitudes towards female sexuality and figured prominently in the development of second-wave feminism. According to Washington Post, it has sold more than 20 million copies worldwide. Born in New York, she was the second of three daughters of Seymore Mann and Eda Mirsky. Attended New York’s Public High School of Music and Art in the 1950’s where she developed her passion for art and writing. As a student at Barnard College, she edited the Barnard Literary Magazine and created poetry programs for the Columbia University campus radio station.

I don't write to please Only to put this need at ease I can't force my poems, spontanious as fire They flow in when they desire Like emotions, they never seem to dim It's my job to scramble; keeping up with them So they are not a loss of time To view my work I won't charge one dime All my hardships are not my demise This life I live is such a prize

Roberto Juarroz (Coronel Dorrego, Provincia de Buenos Aires, 5 de octubre de 1925 - Temperley, Buenos Aires, 31 de marzo de 1995) fue un poeta y ensayista argentino. Graduado en la Facultad de Filosofía y Letras y en Ciencias de la información por la Universidad de Buenos Aires y becario de la misma, amplió estudios en La Sorbona. Fue después profesor titular de la Universidad de Buenos Aires y dirigió el Departamento de Bibliotecología y Documentación de la misma entre 1971 y 1984. En esta universidad ejerció la docencia durante treinta años. Marchó al exilio con el advenimiento del general Perón. Trabajó como bibliotecólogo para la Unesco y la OEA en diversos países y entre 1958 y 1965 dirigió veinte números de la revista Poesía = Poesía junto con Mario Morales. Colaboró en numerosas publicaciones argentinas y extranjeras y fue crítico bibliográfico del diario La Gaceta de Tucumán (1958-63), crítico cinematográfico de la revista Esto es (Buenos Aires, 1956-58) y traductor de varios libros de poesía extranjera, en especial de Antonin Artaud. Su poesía ha sido muy estudiada y vertida a una gran cantidad de lenguas. Desde junio de 1984 fue miembro numerario de la Academia Argentina de Letras. Recibió varios premios, el Gran premio de honor de poesía de la Fundación Argentina de Buenos Aires, el Esteban Echeverría de 1984, el "Jean Malrieu" de Marsella en mayo de 1992, y el premio de la "Bienal Internacional de Poesía", en Lieja, Bélgica, en septiembre de 1992. Obra Salvo su colección Seis poemas sueltos (1960), su obra se agrupa en una serie de volúmenes correlativamente numerados del uno al catorce bajo el título general de Poesía vertical; el primero de ellos data en 1958, el segundo de 1963, el tercero de 1965, el cuarto de 1969 y así sucesivamente; en 1997 apareció la décimocuarta entrega, en forma póstuma. En conjunto, esta obra fue editada por Emecé en tres volúmenes. En un principio influido por el Creacionismo del chileno Vicente Huidobro y el simbolismo de Stéphane Mallarmé, la amistad de un "raro" de la poesía argentina, el maestro del aforismo, Antonio Porchia, autor de un único libro titulado Las voces, le influyó notablemente; le impresionaron, además, los románticos alemanes, en especial Novalis. Su temática se centró en la metapoesía y su lenguaje se fue haciendo conceptual conforme exploraba los límites de la palabra como nexo de relación del hombre con el mundo, un mundo contemplado como apofanía, como revelación. Es una poesía imbuida en algunos aspectos por la filosofía existencial de Martin Heidegger. Para él, la poesía es "el absoluto real", un nuevo sentido de lo sagrado sin teología, "la vida no fosilizada o desfosilizada del lenguaje", un lenguaje que en él es escueto y austero: sus piezas persiguen la máxima condensación y rehúyen la rima y la métrica; en una conferencia dada en Montevideo en agosto de 1993 dijo que "poco a poco se fue formando ese hecho de vida que es escribir hasta que sentí que la poesía era un poco fláccida, repetitiva, aún en los grandes poetas, con zonas en las cuales cedía la tensión interior, ese rango de intensidad que para mí tiene siempre el poema. Eso me llevó a concebir una poesía más ceñida, más estricta o rigurosa, en donde cada elemento fuera irreemplazable. La inclinación fue la de recoger de las situaciones extremas eso que llevamos escondido en nuestro silencio, lo que barajamos y pocas veces decimos. Para eso necesitaba un tipo de lenguaje diferente que dejara de lado lo que las palabras tienen de ornamento, de euforia. Buscar formas de síntesis poética, que no es síntesis intelectual, en donde confluyeran emoción, sensibilidad, inteligencia. Una forma de expresión que penetrase en las zonas aparentemente prohibidas. Zonas que mucha gente se veda a sí misma por temor". Sus poemas se hallan numerados en cada entrega, sin título. Prescinde de referencias geográficas o históricas, de localismos verbales, de eurritmia o eufonía, de efusiones sentimentales, de anécdotas, del uso de voces prestigiosas o a priori poéticas. Típicamente, sus depurados textos tienden a adoptar un modo asertivo, simétricamente estructurado, con significaciones frecuentemente enigmáticas o paradójicas. No le interesa la musicalidad ni la experimentación con el lenguaje per se: intenta buscar el fundamento último de la realidad exterior, por lo que su poesía es una especie de colección de callejones sin salida, una búsqueda constante. En medio de la convulsa historia argentina de su época, el silencio de Juarroz al respecto lo constituye en un extraño ejemplo de ascesis y de poesía pura. Sus poemas son deliberadamente impersonales y abstractos, un conjunto de apartados sueltos de una única formulación general, al modo del Tractatus de Ludwig Wittgenstein. Nunca hay un yo lírico, sólo un nosotros o un uno igualmente anónimo. La poesía de Juarroz es una pesquisa en demanda de un Ser ontológico fugitivo. En cuanto a sus ensayos, son fundamentalmente Poesía y creación (Diálogos con Guillermo Boido); Poesía y Realidad; Poesía, literatura y hermenéutica (Conversaciones con Teresita Saguí). Referencias http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roberto_Juarroz

My name is Jessica Joehanson I am fourteen I live in Farmington Maine and Jesus is my number one. I am an a métier poet. I'm at a very low point in my life but I find myself more and more inspired every day by my crushing heartbreak. I have no plans to become and professional poet it's just a hobby. My poems are based on real life events and my emotions, thoughts, and dreams. My favorite quote is "Somethings are to beautiful captured, you just have to let them be." I am a dreamer and I will always be this way.

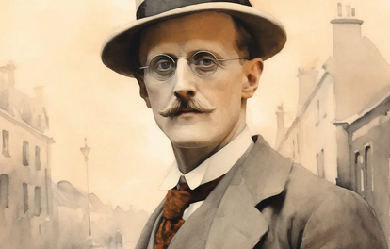

James Augustine Aloysius Joyce (2 February 1882 – 13 January 1941) was an Irish novelist and poet, considered to be one of the most influential writers in the modernist avant-garde of the early 20th century. Joyce is best known for Ulysses (1922), a landmark work in which the episodes of Homer's Odyssey are paralleled in an array of contrasting literary styles, perhaps most prominently the stream of consciousness technique he perfected. Other major works are the short-story collection Dubliners (1914), and the novels A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916) and Finnegans Wake (1939). His complete oeuvre includes three books of poetry, a play, occasional journalism, and his published letters.

Teresa de Cepeda y Ahumada, más conocida por el nombre de Santa Teresa de Jesús o simplemente Teresa de Ávila (Ávila, 28 de marzo de 1515 – Alba de Tormes, 4 de octubre de 1582), fue una religiosa, doctora de la Iglesia Católica, mística y escritora española, fundadora de las carmelitas descalzas, rama de la Orden de Nuestra Señora del Monte Carmelo (o carmelitas).

I work hard and play hard. I am a dad and that is the most important attribute about my self. I have a strong belief in God and trust that he guides me. I also have a soft heart and writing helps getting out the pain i may feel or i may just simply be sharing things i have written in the past. I love to write I do not claim to be good at it, but i enjoy it so much. Writing is my reading. I do not like to read books so writing is my way of exercising my brain. Feel free to critique my writing if it helps me then i thank you, if it is just to banter me then keep it to your self.

Es el gran renovador de la poesía amorosa colombiana y uno de los mejores poetas de la segunda mitad del siglo XX de su país. Darío Jaramillo Agudelo (Santa Rosa de Osos, Antioquia, 28 de julio de 1947), poeta y escritor colombiano, reconocido internacionalmente como uno de los mejores poetas de su país del último siglo. Poeta, novelista y ensayista colombiano nacido en Santa Rosa de Osos, Antioquia, en 1947. Realizó estudios de bachillerato en Medellín y posteriormente, se graduó como abogado y economista en la Universidad Javeriana de Bogotá. Durante años, desempeñó importantes cargos culturales en organismos estatales y fue miembro de los consejos de redacción de la revista Golpe de Dados y de la fundación particular Simón y Lola Guberek. De su poesía se han hecho tres reediciones completas: 77 poemas (Universidad Nacional, 1987), 127 poemas (Universidad de Antioquia, 2000) y Libros de poemas (Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2003); y cinco selecciones parciales: Antología poética (1991), Cuánto silencio debajo de esta luna (1992), Razones del ausente (1998), Aunque es de noche (Pre-Textos, 2000) y Del amor, del olvido (Pre-Textos, 2009). Poesía * Historias, 1974 * Tratado de retórica,1978 * Poemas de amor,1986 * Del ojo a la lengua. Ilustraciones para diez grabados de Juan Antonio Roda", 1995 * Cantar por cantar, Pre-Textos, 2001 * Gatos, Pre-Textos, 2005 * Cuadernos de Música, Pre-Textos, 2008 Prosa * Guía para viajeros, 1991 * Historia de una pasión (texto autobiográfico), Pre-Textos, 2006 * La muerte de Alec, Pre-Textos, 1983 * Cartas cruzadas, 1993 * El juego del alfiler, Pre-Textos, 2002 * Novela con fantasma, Pre-Textos, 2004 * La voz interior, Pre-Textos, 2006 * Memorias de un hombre feliz, Pre-Textos, 2010 * Historia de Simona, Pre-Textos, 2010 Ensayo * Poesía en la canción popular latinoamericana, Pre-Textos, 2009 Premios * Premio Nacional de poesía de Colombia en 1978 por Tratado de retórica * Premio de Novela Corta José María de Pereda en 2010 por Historia de Simona, Pre-Textos, 2010. Referencias Wikipedia - http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Darío_Jaramillo

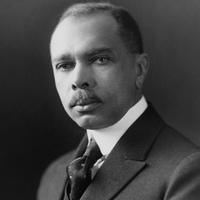

James Weldon Johnson (June 17, 1871– June 26, 1938) was an American author, educator, lawyer, diplomat, songwriter, and civil rights activist. Johnson is best remembered for his leadership of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), where he started working in 1917. In 1920 he was the first African American to be chosen as executive secretary of the organization, effectively the operating officer. He served in that position from 1920 to 1930. Johnson established his reputation as a writer, and was known during the Harlem Renaissance for his poems, novels, and anthologies collecting both poems and spirituals of black culture. He was appointed under President Theodore Roosevelt as US consul in Venezuela and Nicaragua for most of the period from 1906 to 1913. In 1934 he was the first African-American professor to be hired at New York University. Later in life he was a professor of creative literature and writing at Fisk University.

Helen Maria Hunt Jackson, born Helen Fiske (October 15, 1830 – August 12, 1885), was a United States writer who became an activist on behalf of improved treatment of Native Americans by the U.S. government. She detailed the adverse effects of government actions in her history A Century of Dishonor (1881). Her novel Ramona dramatized the federal government's mistreatment of Native Americans in Southern California and attracted considerable attention to her cause, although its popularity was based on its romantic and picturesque qualities rather than its political content. It was estimated to have been reprinted 300 times, and contributed to the growth of tourism in Southern California. Early years She was born Helen Fiske in Amherst, Massachusetts, the daughter of Nathan Welby Fiske and Deborah Waterman Vinal. She had two brothers, both of whom died after birth, and a sister Anne. Her father was a minister, author, and professor of Latin, Greek, and philosophy at Amherst College. Her mother died in 1844 when Helen was fourteen, and her father three years later. Her father provided for her education and arranged for an aunt to care for her. Fiske attended Ipswich Female Seminary and the Abbott Institute, a boarding school run by Reverend J.S.C. Abbott in New York City. She was a classmate of the poet Emily Dickinson, also from Amherst. The two corresponded for the rest of their lives, but few of their letters have survived. Marriage and family In 1852 at age 22, Fiske married U.S. Army Captain Edward Bissell Hunt. They had two sons, one of whom, Murray Hunt, died as an infant in 1854 of a brain disease. In 1863, her husband died in a military accident. Her second son, Rennie Hunt, died of diphtheria in 1865. About 1873-1874, Hunt met William Sharpless Jackson, a wealthy banker and railroad executive, while visiting at Colorado Springs, Colorado, at the resort of Seven Falls. They married in 1875 and she took the name Jackson, under which she was best known for her writings. She was a Unitarian. Career Helen Hunt began writing after the deaths of her family members. She published her early work anonymously, usually under the name "H.H." Ralph Waldo Emerson admired her poetry and used several of her poems in his public readings. He included five of them in his anthology Parnassus. She traveled widely. In the winter of 1873-1874 she was in Colorado Springs, Colorado, in search of a cure for tuberculosis. Here she met the man who would become her second husband. Over the next two years, she published three novels in the anonymous No Name Series, including Mercy Philbrick's Choice and Hetty's Strange History. In 1879 her interests turned to Native Americans after hearing a lecture in Boston by the Ponca Chief Standing Bear. He described the forcible removal of the Ponca from their Nebraska reservation and transfer to the Quapaw Reservation in Indian Territory, where they suffered from disease, climate and poor supplies. Upset about the mistreatment of Native Americans by government agents, Jackson became an activist. She started investigating and publicizing government misconduct, circulating petitions, raising money, and writing letters to the New York Times on behalf of the Ponca. A fiery and prolific writer, Jackson engaged in heated exchanges with federal officials over the injustices committed against American Indians. Among her special targets was U.S. Secretary of Interior Carl Schurz, whom she once called "the most adroit liar I ever knew." She exposed the government's violation of treaties with the American Indian tribes. She documented the corruption of US Indian agents, military officers, and settlers who encroached on and stole Indian lands. Jackson won the support of several newspaper editors who published her reports. Among her correspondents were editor William Hayes Ward of the New York Independent, Richard Watson Guilder of the Century Magazine, and publisher Whitelaw Reid of the New York Daily Tribune. Jackson also wrote a book, the first published under her own name, condemning state and federal Indian policy, and detailing the history of broken treaties. A Century of Dishonor (1881) called for significant reform in government policy toward Native Americans.[10] Jackson sent a copy to every member of Congress with a quote from Benjamin Franklin printed in red on the cover: "Look upon your hands: they are stained with the blood of your relations." The New York Times later wrote that she "soon made enemies at Washington by her often unmeasured attacks, and while on general lines she did some good, her case was weakened by her inability, in some cases, to substantiate the charges she had made; hence many who were at first sympathetic fell away." Jackson went to southern California for respite. Having been interested in the area's missions and the Mission Indians on an earlier visit, she began an in-depth study. While in Los Angeles, she met Don Antonio Coronel, former mayor of the city and a well-known authority on early Californio life in the area. He had served as inspector of missions for the Mexican government. Coronel told her about the plight of the Mission Indians after 1833. They were buffeted by the secularization policies of the Mexican government, as well as later U.S. policies, both of which led to their removal from mission lands. Under its original land grants, the Mexican government provided for resident Indians to continue to occupy such lands. After taking control of the territory in 1848, the U.S. generally disregarded such Mission Indian occupancy claims. In 1852, there were an estimated 15,000 Mission Indians in Southern California. By the time of Jackson's visit, they numbered fewer than 4,000. Coronel's account inspired Jackson to action. The U.S. Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Hiram Price, recommended her appointment as an Interior Department agent. Jackson's assignment was to visit the Mission Indians, ascertain the location and condition of various bands, and determine what lands, if any, should be purchased for their use. With the help of the US Indian agent Abbot Kinney, Jackson traveled throughout Southern California and documented conditions. At one point, she hired a law firm to protect the rights of a family of Saboba Indians facing dispossession from their land at the foot of the San Jacinto Mountains. In 1883, Jackson completed her 56-page report. It recommended extensive government relief for the Mission Indians, including the purchase of new lands for reservations and the establishment of more Indian schools. A bill embodying her recommendations passed the U.S. Senate but died in the House of Representatives. Jackson decided to write a novel to reach a wider audience. When she wrote Coronel asking for details about early California and any romantic incidents he could remember, she explained her purpose: "I am going to write a novel, in which will be set forth some Indian experiences in a way to move people's hearts. People will read a novel when they will not read serious books."[14] She was inspired by her friend Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852). "If I could write a story that would do for the Indian one-hundredth part what Uncle Tom's Cabin did for the Negro, I would be thankful the rest of my life," she wrote. Although Jackson started an outline in California, she began writing the novel in December 1883 in her New York hotel room, and completed it in about three months. Originally titled In The Name of the Law, she published it as Ramona (1884). It featured Ramona, an orphan girl who was half Indian and half Scots, raised in Spanish Californio society, and her Indian husband Alessandro, and their struggles for land of their own. The characters were based on people known by Jackson and incidents which she had encountered. The book achieved rapid success among a wide public and was popular for generations; it was estimated to have been reprinted 300 times. Its romantic story also contributed to the growth of tourism to Southern California. Encouraged by the popularity of her book, Jackson planned to write a children's story about Indian issues, but did not live to complete it. Her last letter was written to President Grover Cleveland and said: "From my death bed I send you message of heartfelt thanks for what you have already done for the Indians. I ask you to read my Century of Dishonor. I am dying happier for the belief I have that it is your hand that is destined to strike the first steady blow toward lifting this burden of infamy from our country and righting the wrongs of the Indian race." Jackson died of stomach cancer in 1885 in San Francisco, California. Her husband arranged for her burial on a one-acre plot on a high plateau overlooking Colorado Springs, Colorado. Her grave was later moved to Evergreen Cemetery in Colorado Springs. At the time of her death, her estate was valued at $12,642. She used her married names, Helen Hunt and Helen Jackson, but she is most often referred to as Helen Hunt Jackson. The New York Times referred to her as Helen Hunt Jackson in 1885, reporting on her final illness, and in 1886, reporting on visitors to her grave. The name was used during her lifetime by others, though she disliked the practice. "It is not proper to keep one's first married name, after a second marriage", she wrote to Moncure Conway. To Caroline Healey Dall, she admitted she was "positively waging war" against being called "Helen Hunt Jackson". Critical response and legacy Jackson's A Century of Dishonor remains in print, as does a collection of her poetry. A New York Times reviewer said of Ramona that "by one estimate, the book has been reprinted 300 times." One year after Jackson's death the North American Review called Ramona "unquestionably the best novel yet produced by an American woman" and named it, along with Uncle Tom's Cabin, one of two most ethical novels of the 19th century. Sixty years after its publication, 600,000 copies had been sold. There have been over 300 reissues to date and the book has never been out of print. The novel has been adapted for other media, including three films, stage, and television productions. Valery Sherer Mathes assessed the writer and her work: Ramona may not have been another Uncle Tom's Cabin, but it served, along with Jackson's writings on the Mission Indians of California, as a catalyst for other reformers ....Helen Hunt Jackson cared deeply for the Indians of California. She cared enough to undermine her health while devoting the last few years of her life to bettering their lives. Her enduring writings, therefore, provided a legacy to other reformers, who cherished her work enough to carry on her struggle and at least try to improve the lives of America's first inhabitants. Her friend Emily Dickinson once described her limitations: "she has the facts but not the phosphorescence." In a review of a film version, a journalist wrote about the novel, calling it "the long and lugubrious romance by Helen Hunt Jackson, over which America wept unnumbered gallons in the eighties and nineties," and complained of "the long, uneventful stretches of the novel."[26] In reviewing the history of her publisher, Houghton Mifflin, a 1970 reviewer noted that Jackson typified the house's success: "Middle aged, middle class, middlebrow." Jackson herself wrote, "My Century of Dishonor and Ramona are the only things I have done of which I am glad.... They will live, and... bear fruit." A portion of Jackson's Colorado home has been reconstructed in the Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum and furnished with her possessions.

Hi, My name is Amanda Joannevaeh Steinbrecher. Everyone calls me Lady J. I am 27 years old. I have two children, a nine year old son named Shayn Azriel and a three year old daughter named Nacirema Jillian. I used to be very shy and timid. I would hide all of my poetry, so no one would see my true feelings and emotions. I have been writing poetry for as long as I can remember. In second grade I won an Echoes Theatre Award for my writing, and the awards, certificates, and recognitions have continued consistently on in my life. Poetry is my greatest outlet to express myself. I ahve always used poetry as my escape from pain, and always go back to re read everything I write to see where I have been in the past emotionally and mentally, and to stay update reading how far I have come. Some of my poetry will make you sad, or be sensitive to some readers, so I ask that you read at your own risk. Other pieces I have written are very motivatioanl and inspirational. I hope and pray that through my poetry I can help inspire others who may have faced some of the same struggles I have myself. I pray everyone on here with be abundantly bless with joy,peace,harmony, happiness, laughter, and Love. God Bless You All !! Sincerely, <3 Lady J. <3