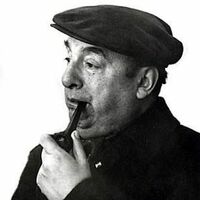

Pablo Neruda, seudónimo y posterior nombre legal de Ricardo Eliécer Neftalí Reyes Basoalto (Parral, 12 de julio de 1904-Santiago, 23 de septiembre de 1973), fue un poeta y político chileno. Es considerado entre los más destacados e influyentes artistas de su siglo; además de haber sido senador de la república chilena, miembro del Comité Central del Partido Comunista (PC), precandidato a la presidencia de su país y embajador en Francia. En 1971 Neruda recibió el Premio Nobel de Literatura «por una poesía que con la acción de una fuerza elemental da vida al destino y los sueños de un continente».

Born and raised in Soweto. God, my family and sports and music are the most important things in my life. I started writing poems as a hobby and then developed a greater liking for it. The poems I write are based on the emotions I feel at that time, but also sometimes they are inspired by music & movies. I write poetry to entertain and inspire other people to better themselves and that through them, they will learn & most importantly, know how strong and mighty God is.

Amado Ruiz de Nervo y Ordaz (Tepic, Distrito Militar de Tepic, Jalisco, República Restaurada, 27 de agosto de 1870-Montevideo, Uruguay, 24 de mayo de 1919), más conocido como Amado Nervo, fue un poeta y escritor mexicano, perteneciente al movimiento modernista. Fue miembro correspondiente de la Academia Mexicana de la Lengua, pero no pudo serlo de número por residir en el extranjero.

Frederic Ogden Nash (August 19, 1902 – May 19, 1971) was an American poet well known for his light verse. At the time of his death in 1971, The New York Times said his “droll verse with its unconventional rhymes made him the country’s best-known producer of humorous poetry”. Nash wrote over 500 pieces of comic verse. The best of his work was published in 14 volumes between 1931 and 1972.

Acolmiztli Nezahualcóyotl (1402 – 1472) (náhuatl: Nezahual.cóyō.tl 'coyote que ayuna') fue el monarca (tlatoani) de la ciudad-estado de Tetzcuco en el México antiguo. Nació el 28 de abril (según otras fuentes, el 4 de febrero) de 1402 en Texcoco (actualmente un municipio del Estado de México) en la actual República Mexicana y murió en 1472. Era hijo del sexto señor de los chichimecas, Ixtlilxóchitl, cuyo nombre significa 'flor oscura' (īxtlīl- 'oscuro, negro', xōchitl 'flor') señor de la ciudad de Texcoco, y de la princesa mexica Matlalcihuatzin, hija del tlatoani azteca Huitzilíhuitl, segundo señor de Tenochtitlan. Al nacer, le fue asignado el nombre de Acolmiztli (náhuatl: Acōlmiztli, 'felino fuerte')?, pero las tristes circunstancias que rodearon su adolescencia hicieron que se cambiara el nombre por el de Nezahualcóyotl que significa «coyote que ayuna o coyote hambriento», entendiéndose el ayuno como una forma de sacrificio.[cita requerida] A principios del siglo XV el mayor centro de poder en la cuenca de México era Azcapotzalco, capital de los tepanecas. El señorío tepaneca bajo Tezozómoc tenía tintes tiránicos, y después de un relativo fracaso militar, mediante una conspiración palaciega logró expulsar de Texcoco y eventualmente, dar muerte a Ixtlixóchitl, padre de Nezahualcóyotl. Tiempo después éste tuvo la oportunidad de participar en una alianza con los mexicas, que además de vengar la muerte de su padre, logró derruir el poder tepaneca. Una vez que recuperó el trono, Nezahualcóyotl gobernó Texcoco con valor y sabiduría. Asimismo, ganó reputación de sabio y obtuvo fama como poeta. Su amplia formación intelectual se traducía en una elevada sensibilidad estética y un gran amor por la naturaleza, que quedaron reflejados no sólo en la arquitectura de la ciudad, sino también en sus manifestaciones poéticas y filosóficas. Nezahualcóyotl llegó a construir un jardín botánico adornado con hermosas pozas de agua y acueductos en Tetzcotzingo, donde eran habituales las reuniones de poetas e intelectuales. Algunos historiadores han manifestado que aun cuando los acolhuas profesaban el politeísmo, él comenzó a desarrollar la idea de un dios único, al cual llama Tloquenahuaque. Varios de sus versos se encuentran actualmente plasmados en los muros del Museo Nacional de Antropología en la Ciudad de México Texcoco o la guerra chichimeca de rojes Desde su infancia y durante su adolescencia, Nezahualcóyotl recibió una educación muy completa correspondiente a su linaje. Estudió primero en el palacio con tutores designados por su padre, y más tarde en el calmecac, escuela de estudios superiores donde asistían los jóvenes de las clases privilegiadas y gobernantes. De esta forma aprendió la escritura; los ritos y tradiciones ancestrales de sus antepasados chichimecas-toltecas; la historia, las enseñanzas y las doctrinas heredadas por los mexicas y acolhuacanos venidos del norte y las artes de la guerra y la política, que lo prepararían para gobernar a su pueblo. Aunque Netzahualcóyotl era heredero nato del reino de Texcoco, no vivía como un príncipe rodeado de lujos y comodidades, pues en esos años su padre enfrentaba el asedio de los tepanecas de Azcapotzalco, cuyo belicoso rey, Tezozomoc, ya había conquistado Tenayuca y Culhuacán, y ambicionaba extender su imperio hacia la región norte del gran lago. La intención de Tezozomoc era asesinar al rey Ixtlilxóchitl y a toda su familia para poder apoderarse del trono de Texcoco. Para entonces, el reino texcocano se encontraba debilitado, no contaba con aliados comprometidos, ni tenía las suficientes armas ni el ejército necesario para sostener una guerra y repeler la invasión. En 1418, los tepanecas sitiaron la ciudad de Texcoco durante 30 días. Bajo la amenaza de muerte lanzada por Tezozomoc, el rey Ixtlilxóchitl de 54 años, errante y furtivo, tuvo que abandonar su palacio. Mientras las huestes de Tezozómoc rastreaban los alrededores de la ciudad para encontrar al rey y príncipe texcocanos, éstos se refugiaron en las cuevas de Cualhyacac y Tzinacanoztoc, rodeados de unos pocos leales. No pudiendo ocultarse allí por mucho tiempo, Ixtlilxóchitl ordenó a su hijo que se adentrara en el bosque, mientras él y unos pocos hombres trataban de detener sin éxito el avance de sus captores. Sin embargo, éstos anticiparon su ataque y lo sorprendieron en el bosque. El príncipe Nezahualcóyotl, oculto entre las ramas de un árbol, fue testigo de cómo su padre luchó hasta caer abatido por las lanzas tepanecas. Luego de presenciar el asesinato de su padre, Nezahualcóyotl, de apenas 16 años, logró escapar y huyó. Antes había pedido a sus partidarios que cesaran la resistencia y que, por el momento, se sometieran a la tiranía de Tezozomoc, mientras él buscaba el apoyo de otros pueblos y encontraba el modo de liberarlos. Una vez que Tezozomoc se apoderó completamente de la ciudad, ordenó la captura de Nezahualcóyotl y ofreció una recompensa para quien se lo entregara vivo o muerto; sabía que el legítimo príncipe heredero representaba un peligro pues intentaría liberar a su reino. A partir de entonces y durante los siguientes dos años, Nezahualcóyotl debió eludir el acoso y las asechanzas de sus perseguidores. Clandestinamente, recorrió varios poblados con el fin de conseguir aliados y mantenerse informado de los planes del rey usurpador. Un tiempo se mantuvo encubierto en Tlaxcala, donde pudo pasar inadvertido disfrazado de campesino. De ahí se trasladó a Chalco y se incorporó como soldado al ejército de los chalcas , pero fue descubierto y encerrado en una jaula. Toteotzintecuhtli, el soberano de esa ciudad, lo condenó a muerte para congraciarse con el tirano Tezozomoc. Sin embargo, Quetzalmacatzin, hermano del gobernante chalca, se compadeció de Nezahualcóyotl y lo ayudó a escapar, cambiando sus ropas y ocupando su lugar en la jaula. Nezahualcóyotl pudo salir de Chalco y regresar a Tlaxcala sin ser reconocido; mientras tanto, su protector fue ejecutado en su lugar, acusado de traición. Es hasta 1420 cuando concluye ese periodo errante, luego de que las tías de Nezahualcoyotl, hermanas de su madre y esposas de los gobernantes de Tenochtitlan y Tlatelolco, solicitaron al rey tepaneca el perdón para su joven sobrino. Tezozomoc consintió que Nezahualcoyotl viviera en Tenochtitlan, ciudad donde el príncipe sin trono fue afectuosamente recibido. Durante los siguientes ocho años, gracias a la hospitalidad de su familia materna, Netzahualcoyotl pudo continuar con su educación y adiestramiento militar, lo cual le permitió convertirse rápidamente en un guerrero; de igual modo cultivó su vocación por las artes y las ciencias. En esos años, Tezozomoc le otorgó un palacio en Texcoco y le autorizó a viajar entre las dos ciudades. Sin embargo, Nezahualcóyotl no había olvidado los sucesos que provocaron su exilio. Decidido a recuperar su trono, planeaba la estrategia para cumplir su objetivo. Para entonces, el viejo Tezozomoc, debilitado y gravemente enfermo, sospechaba de las intenciones de Nezahualcóyotl y, casi al borde de la muerte, encomendó a sus tres hijos Maxtla, Teyatzin y Tlatoca Tlitzpaltzin asesinar al príncipe destronado. Netzahualcoyotl, al tanto de los planes de sus enemigos, se refugió en Tenochtitlan bajo la protección de su tío, el rey Chimalpopoca. Un año después sobrevino la muerte de Tezozomoc, y Maxtla ocupó su lugar como soberano de Azcapotzalco. Aunque conocía el propósito de asesinarlo, Nezahualcoyotl asistió al funeral del patriarca tepaneca. El heredero de Tezozomoc no estaba dispuesto a ceder el trono de Texcoco a Nezahualcóyotl, y decidió hacer prisionero a Chimalpopoca como represalia contra este por haber ayudado a su enemigo; al mismo tiempo, envió a un grupo de mercenarios para buscar y ejecutar al temerario príncipe. Netzahualcóyotl, desafiando el peligro, llegó a Azcapotzalco para interceder por la libertad de Chimalpopoca. Maxtla fingió ser benevolente, pero trató de asesinarlo a traición. Netzahualcóyotl consiguió salir ileso y escapó hacia Texcoco. Entonces Maxtla preparó una nueva trampa para eliminarlo. Convenció a Yancuiltzin, hijo natural del padre de Nezahualcóyotl, para que invitara a su medio hermano a un banquete y una vez que estuviera solo en su casa lo matara. Sin embargo, Nezahualcóyotl es advertido del siniestro plan por un amigo y, para librarse de la muerte, dispuso que un labriego se hiciera pasar por él para asistir al banquete de Yancuiltzin. Allí, el supuesto Nezahualcóyotl es decapitado y su cabeza fue entregada como trofeo a Maxtla, quien creía que al fin había acabado con el invencible príncipe. Sin embargo, no tardó en enterarse de que Nezahualcóyotl aún estaba vivo. Enfurecido, Maxtla dio órdenes a sus principales capitanes para que se dirigieran a Texcoco en busca de Nezahualcóyotl y lo aniquilaran sin piedad. De nuevo, el príncipe texcocano tuvo que huir de una feroz persecución. En múltiples ocasiones logró salir indemne de las emboscadas ordenadas por Maxtla. Éste, al no poder dar alcance a su escurridizo oponente, descargó su venganza contra Chimalpopoca y alevosamente lo asesinó, lo cual daría un drástico giro en favor de Nezahualcóyotl, pues los mexicas, indignados, decidieron romper su alianza con Azcapotzalco y nombraron a Izcóatl como su nuevo rey. Esto acarreó que Tenochtitlan fuera sitiada por Maxtla. Entre tanto, con gran habilidad diplomática, Netzahualcóyotl consiguió atraerse los favores de otras ciudades descontentas con la tiranía tepaneca y organizó un frente común, cuyo peso principal recayó en los tlaxcaltecas y los huejotzincas. El formidable ejército aliado alcanzó victorias en Otumba y Acolman antes de tomar Texcoco en 1429. En seguida Netzahualcóyotl dedicó sus esfuerzos a liberar México y Tlatelolco. En una cruenta batalla, destruyó Azcapotzalco después de un sitio de ciento catorce días. Maxtla murió a manos de Nezahualcóyotl, quien, dispuesto a inaugurar una época de esplendor en el Valle de México, consiguió sellar un pacto confederal con Itzcóatl, de Tenochtitlan y Totoquiyauhtzin, señor de Tlacopan, pacto conocido como la Ēxcān Tlahtolōyān. Cuando en 1472 falleció Netzahualcóyotl, subió al trono su hijo Nezahualpilli, quien gobernó la ciudad hasta el año 1516, continuando la política expansiva emprendida por su antecesor. Hitos de su gobierno El gobierno de Nezahualcóyotl no sólo representó un modelo de gobierno y administración, el rey también emprendió extraordinarios proyectos de construcción y arquitectura en Texcoco y Tenochtitlan. Tuvo especial interés por las obras de servicio y ornato, por lo que edificó presas, acueductos, palacios, templos, monumentos, calzadas y jardines. Gracias a su visión estética, buscó armonizar los requerimientos de los sistemas urbanos con las condiciones naturales del medio ambiente. Además de dirigir la urbanización de su reino, hizo edificar más de cuatrocientas casas y palacetes para los señores y caballeros de su corte, cada uno de acuerdo con el rango y los méritos de su habitante. Entre las grandes obras realizadas por Nezahualcóyotl se encuentra el Templo Mayor de Texcoco que estaba dedicado a Huitzilopochtli y a Tláloc, a cuya terraza superior se ascendía a través de 160 escalones. Motivado por su amor por la naturaleza, en los bosques de Tezcutzingo y Chapultepec, sus lugares de recreación preferidos, preservó los manantiales y los árboles, condujo el agua por los montes, introdujo el riego, talló estanques y albercas en las formaciones rocosas, plantó flores, propagó variadas especies animales y ordenó la construcción de un zoológico y un jardín botánico. Asimismo destacan los famosos jardines de su soberbio palacio, así como el portentoso acueducto erigido en el bosque de Chapultepec para abastecer de agua potable a Tenochtitlan. Pero lo que es más extraordinario, a solicitud de su homólogo y aliado Moctezuma I el grande, también concibió y realizó un dique de piedra y madera (que los españoles llamaron "el gran albarradón") que sirvió como defensa contra las inundaciones que afectaban a esa ciudad, y que además impedía que se mezclaran el agua salada y el agua dulce del gran lago. Homenajes * Para honrar la memoria de este ilustre monarca prehispánico, se le ha dedicado una fuente en el Castillo de Chapultepec, diseñada por el artista Luis Ortiz Monasterio, Igualmente la obra de Federico Cantú en la Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, además de bautizar con su nombre un municipio y una ciudad del Estado de México. * Igualmente, en la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México se erigió la Sala Nezahualcóyotl con su nombre. * En la ciudad española de Cáceres existe una estatua en su honor. * Su imagen aparece en los billetes de 100 pesos mexicanos, acompañado de uno de sus poemas más conocidos. * En el año 2005 su nombre fue inscrito con letras de oro en el muro de honor de la Cámara de Diputados del Congreso Mexicano. * En el municipio Texcoco, su lugar natal, se le construyo un monumento, así como también unas escuelas. * En el acto para conmemorar el Día Internacional de la Lengua Materna, efectuado el 21 de febrero del 2013 en el Museo Nacional de Arte, la Dirección General de Culturas Populares del Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes, a cargo de Miriam Morales Sanhueza, presentó la aplicación gratuita para iPad dedicada a la obra poética de Nezahualcóyotl: incluye 38 poemas que pueden leerse en náhuatl y en español. También se incluyó un facsímil digital de las primeras transcripciones conservadas de los cantos prehispánicos de Nezahuacóyotl y un cómic sobre su vida. La aplicación incluye una sección de multimadia con entrevistas a Miguel León-Portilla y a Patrick Johansson. Billetes Este personaje histórico aparece en el billete mexicano con denominación de 100 pesos; en el anverso del billete se encuentra su rostro, y con letra muy muy pequeña, un poema suyo, que dice: «Amo el canto del zenzontle, pájaro de las cuatrocientas voces. Amo el color del jade, y el enervante perfume de las flores, pero lo que más amo es a mi hermano, el hombre.» Cabeza de Coyote Como parte de los festejos del 45 aniversario de la creación del Municipio, el alcalde perredista Víctor Bautista López, en compañía de alcaldes, diputados, artistas y población en general inauguraron la obra que también fungirá como Centro de exposiciones. El edil manifestó que esta edificación dará orgullo e identidad al municipio, pues es una de las obras más grandes no sólo del estado de México sino del país y de América Latina. Señaló que la escultura se localiza en la glorieta que forman las avenidas Adolfo López Mateos y Pantitán, puede apreciarse desde más de dos kilómetros a la redonda y desde el aeropuerto Internacional de la ciudad de México. Refirió que la obra tiene una superficie de 366 metros cuadrados y un basamento interior de 21 metros. La construcción se inició en el 2005 con una inversión de dos millones de pesos y estaba proyectada para concluirse en un año. Por falta de recursos los trabajos se retrasaron dos años y para terminarla se buscó el financiamiento de aportaciones privadas y de los ciudadanos, a través de la compra de réplicas de la "Cabeza de Coyote". El escultor Sebastián no asistió a la inauguración y en su representación acudió su esposa Gabriela Hernández, quien dijo que el artista participa en España en una exposición sobre El Quijote y además va a recibir un reconocimiento de manos del rey Juan Carlos. Referencias Wikipedia-http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nezahualc%C3%B3yotl

John Newton (24 July 1725– 21 December 1807) was an English sailor, in the Royal Navy for a period, and later a captain of slave ships. He became ordained as an evangelical Anglican cleric, served Olney, Buckinghamshire for two decades, and also wrote hymns, known for “Amazing Grace” and “Glorious Things of Thee Are Spoken”. Newton started his career at sea at a young age, and worked on slave ships in the slave trade for several years. After experiencing a period of Christian conversion Newton eventually renounced his trade and became a prominent supporter of abolitionism, living to see Britain’s abolition of the African slave trade in 1807. Early life John Newton was born in Wapping, London, in 1725, the son of Elizabeth (née Scatliff) and John Newton Sr., a shipmaster in the Mediterranean service. Elizabeth was the only daughter of Simon Scatliff, an instrument maker from London (the marriage register records her maiden name as Seatcliffe). Elizabeth was brought up as a Nonconformist. She died of tuberculosis (then called consumption) in July 1732, about two weeks before John’s seventh birthday. Newton spent two years at boarding school before going to live in Aveley in Essex, the home of his father’s new wife. At age eleven he first went to sea with his father. Newton sailed six voyages before his father retired in 1742. At that time, Newton’s father made plans for him to work at a sugarcane plantation in Jamaica. Instead, Newton signed on with a merchant ship sailing to the Mediterranean Sea. Impressment into naval service In 1743, while going to visit friends, Newton was captured and pressed into the naval service by the Royal Navy. He became a midshipman aboard HMS Harwich. At one point Newton tried to desert and was punished in front of the crew of 350. Stripped to the waist and tied to the grating, he received a flogging of eight dozen lashes and was reduced to the rank of a common seaman. Following that disgrace and humiliation, Newton initially contemplated murdering the captain and committing suicide by throwing himself overboard. He recovered, both physically and mentally. Later, while Harwich was en route to India, he transferred to Pegasus, a slave ship bound for West Africa. The ship carried goods to Africa and traded them for slaves to be shipped to the colonies in the Caribbean and North America. Enslavement and rescue Newton did not get along with the crew of Pegasus. They left him in West Africa with Amos Clowe, a slave dealer. Clowe took Newton to the coast and gave him to his wife, Princess Peye of the Sherbro people. She abused and mistreated Newton equally as much as she did her other slaves. Newton later recounted this period as the time he was “once an infidel and libertine, a servant of slaves in West Africa.” Early in 1748 he was rescued by a sea captain who had been asked by Newton’s father to search for him, and returned to England on the merchant ship Greyhound, which was carrying beeswax and dyer’s wood, now referred to as camwood. Spiritual conversion During his 1748 voyage to England after his rescue, Newton had a spiritual conversion. The ship encountered a severe storm off the coast of County Donegal in Ulster, Ireland, and almost sank. Newton awoke in the middle of the night and, as the ship filled with water, called out to God. The cargo shifted and stopped up the hole, and the ship drifted to safety. Newton marked this experience as the beginning of his conversion to evangelical Christianity. He began to read the Bible and other religious literature. By the time he reached Britain, he had accepted the doctrines of evangelical Christianity. The date was 10 March 1748, an anniversary he marked for the rest of his life. From that point on, he avoided profanity, gambling, and drinking. Although he continued to work in the slave trade, he had gained sympathy for the slaves during his time in Africa. He later said that his true conversion did not happen until some time later: “I cannot consider myself to have been a believer in the full sense of the word, until a considerable time afterwards.” Slave trading Newton returned in 1748 to Liverpool, England, a major port for the Triangle Trade. Partly due to the influence of his father’s friend Joseph Manesty, he obtained a position as first mate aboard the slave ship Brownlow, bound for the West Indies via the coast of Guinea. While in west Africa (1748–49), Newton acknowledged the inadequacy of his spiritual life. He became ill with a fever and professed his full belief in Christ, asking God to take control of his destiny. He later said that this was the first time he felt totally at peace with God. Newton did not however immediately renounce working in the slave trade. After his return to England in 1750, he made three voyages as captain of the slave ships Duke of Argyle (1750) and African (1752–53 and 1753–54). After suffering a severe stroke in 1754, he gave up seafaring and slave-trading activities. But he continued to invest in Manesty’s slaving operations. Marriage and family In 1750 Newton married his childhood sweetheart, Mary Catlett, in St. Margaret’s Church, Rochester. Newton adopted his two orphaned nieces, Elizabeth and Eliza Catlett, children of one of his brothers-in-law and his wife. Newton’s niece Alys Newton later married Mehul, a prince from India. Anglican priest In 1755 Newton was appointed as tide surveyor (a tax collector) of the Port of Liverpool, again through the influence of Manesty. In his spare time, he studied Greek, Hebrew, and Syriac, preparing for serious religious study. He became well known as an evangelical lay minister. In 1757, he applied to be ordained as a priest in the Church of England, but it was more than seven years before he was eventually accepted. During this period, he also applied to the Methodists, Independents and Presbyterians. He mailed applications directly to the Bishops of Chester and Lincoln and the Archbishops of Canterbury and York. Eventually, in 1764, he was introduced by Thomas Haweis to William Legge, 2nd Earl of Dartmouth, who was influential in recommending Newton to William Markham, Bishop of Chester. Haweis suggested Newton for the living of Olney, Buckinghamshire. On 29 April 1764 Newton received deacon’s orders, and finally was ordained as a priest on 17 June. As curate of Olney, Newton was partly sponsored by John Thornton, a wealthy merchant and evangelical philanthropist. He supplemented Newton’s stipend of £60 a year with £200 a year “for hospitality and to help the poor”. Newton soon became well known for his pastoral care, as much as for his beliefs. His friendship with Dissenters and evangelical clergy led to his being respected by Anglicans and Nonconformists alike. He spent sixteen years at Olney. His preaching was so popular that the congregation added a gallery to the church to accommodate the many persons who flocked to hear him. Some five years later, in 1772, Thomas Scott took up the curacy of the neighbouring parishes of Stoke Goldington and Weston Underwood. Newton was instrumental in converting Scott from a cynical ‘career priest’ to a true believer, a conversion which Scott related in his spiritual autobiography The Force Of Truth (1779). Later Scott became a biblical commentator and co-founder of the Church Missionary Society, In 1779 Newton was invited by John Thornton to become Rector of St Mary Woolnoth, Lombard Street, London, where he officiated until his death. The church had been built by Nicholas Hawksmoor in 1727 in the fashionable Baroque style. Newton was one of only two evangelical Anglican priests in the capital, and he soon found himself gaining in popularity amongst the growing evangelical party. He was a strong supporter of evangelicalism in the Church of England. He remained a friend of Dissenters (such as Methodists and Baptists) as well as Anglicans. Young churchmen and people struggling with faith sought his advice, including such well-known social figures as the writer and philanthropist Hannah More, and the young William Wilberforce, a Member of Parliament who had recently suffered a crisis of conscience and religious conversion while contemplating leaving politics. The younger man consulted with Newton, who encouraged Wilberforce to stay in Parliament and “serve God where he was”. In 1792, Newton was presented with the degree of Doctor of Divinity by the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University). Abolitionist In 1788, 34 years after he had retired from the slave trade, Newton broke a long silence on the subject with the publication of a forceful pamphlet Thoughts Upon the Slave Trade, in which he described the horrific conditions of the slave ships during the Middle Passage. He apologized for “a confession, which... comes too late... It will always be a subject of humiliating reflection to me, that I was once an active instrument in a business at which my heart now shudders.” He had copies sent to every MP, and the pamphlet sold so well that it swiftly required reprinting. Newton became an ally of William Wilberforce, leader of the Parliamentary campaign to abolish the African slave trade. He lived to see the British passage of the Slave Trade Act 1807, which enacted this event. Some modern writers have criticised Newton for continuing to participate in the slave trade after his religious conversion, but Christianity did not deter thousands of slaveholders in the colonies from owning other men, nor many others from profiting by the slave trade. Newton came to believe that during the first five of his nine years as a slave trader he had not been a Christian in the full sense of the term. In 1763 he wrote: “I was greatly deficient in many respects... I cannot consider myself to have been a believer in the full sense of the word, until a considerable time afterwards.” Writer and hymnist In 1767 William Cowper, the poet, moved to Olney. He worshipped in Newton’s church, and collaborated with the priest on a volume of hymns; it was published as Olney Hymns in 1779. This work had a great influence on English hymnology. The volume included Newton’s well-known hymns: “Glorious Things of Thee Are Spoken,” “How Sweet the Name of Jesus Sounds!,” “Let Us Love, and Sing, and Wonder,” “Come, My Soul, Thy Suit Prepare,” “Approach, My Soul, the Mercy-seat”, and “Faith’s Review and Expectation,” which has come to be known by its opening phrase, “Amazing Grace”. Many of Newton’s (as well as Cowper’s) hymns are preserved in the Sacred Harp, a hymnal used in the American South during the Second Great Awakening. Hymns were scored according to the tonal scale for shape note singing. Easily learned and incorporating singers into four-part harmony, shape note music was widely used by evangelical preachers to reach new congregants. Newton also contributed to the Cheap Repository Tracts. He wrote an autobiography entitled An Authentic Narrative of Some Remarkable And Interesting Particulars in the Life of———Communicated, in a Series of Letters, to the Reverend T. Haweiss, which he published anonymously. It was later described as 'written in an easy style, distinguished by great natural shrewdness, and sanctified by the Lord God and prayer’. Final years Newton’s wife Mary Catlett died in 1790, after which he published Letters to a Wife (1793), in which he expressed his grief. Plagued by ill health and failing eyesight, Newton died on 21 December 1807 in London. He was buried beside his wife in St. Mary Woolnoth in London. Both were reinterred at the Church of St. Peter and Paul in Olney in 1893. Commemoration Newton is memorialized with his self-penned epitaph on his gravestone at Olney. When he was initially interred in London, a memorial plaque to Newton, containing his self-penned epitaph, was installed on the wall of St Mary Woolnoth. At the bottom of the plaque are the words: "The above Epitaph was written by the Deceased who directed it to be inscribed on a plain Marble Tablet. He died on December the 21st December 1807. Aged 82 Years, and his Mortal Remains are deposited in the Vault beneath the Church.” The town of Newton, Sierra Leone is named after him. To this day his former town of Olney provides philanthropy for the African town. In 1982, Newton was recognized for his influential hymns by the Gospel Music Association when he was inducted into the Gospel Music Hall of Fame. Portrayals in media Film The film Amazing Grace (2006) highlights Newton’s influence on William Wilberforce. Albert Finney portrays Newton, Ioan Gruffudd is Wilberforce, and the film was directed by Michael Apted. The film portrays Newton as a penitent haunted by the ghosts of 20,000 slaves. The Nigerian film The Amazing Grace (2006), the creation of Nigerian director/writer/producer Jeta Amata, provides an African perspective on the slave trade. Nigerian actors Joke Silva, Mbong Odungide, and Fred Amata (brother of the director) portray Africans who are captured and taken away from their homeland by slave traders. Newton is played by Nick Moran. The 2014 film Freedom tells the story of an American slave (Samuel Woodward, played by Cuba Gooding, Jr.) escaping to freedom via the Underground Railroad. A parallel earlier story depicts John Newton (played by Bernhard Forcher) as the captain of a slave ship bound for America carrying Samuel’s grandfather. Newton’s conversion is explored as well. Stage productions African Snow (2007), a play by Murray Watts, takes place in the mind of John Newton. It was first produced at the York Theatre Royal as a co-production with Riding Lights Theatre Company, transferring to the Trafalgar Studios in London’s West End and a National Tour. Newton was played by Roger Alborough and Olaudah Equiano by Israel Oyelumade. The musical Amazing Grace is a dramatisation of Newton’s life. The 2014 pre-Broadway and 2015 Broadway productions starred Josh Young as Newton. Television Newton is portrayed by actor John Castle in the British television miniseries, The Fight Against Slavery (1975). Novels Caryl Phillips’ novel, Crossing the River (1993), includes nearly verbatim excerpts of Newton’s logs from his Journal of a Slave Trader. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Newton

Salvador Novo (Ciudad de México, 30 de julio de 1904 — Ibídem, 13 de enero de 1974) fue un poeta, ensayista, dramaturgo e historiador mexicano, miembro del grupo ‘Los Contemporáneos’ y de la Academia Mexicana de la Lengua. Su característica principal, como autor, fue su prosa hábil y rápida, así como su picardía al escribir. Se decía de él que era “el homosexual belicosamente reconocido y asumido en épocas de afirmación despiadada del machismo”.

hi I'm Allison. "Some of us get dipped in flat, some in satin, some in gloss.... But every once in a while, you find someone who's iridescent, and when you do, nothing will ever compare.” “My heart stopped. It just stopped beating. And for the first time in my life, I had that feeling. You know, like the world is moving all around you, all beneath you, all inside you, and you're floating. Floating in midair. And the only thing keeping you from drifting away is the other person's eyes. They're connected to yours by some invisible physical force, and they hold you fast while the rest of the world swirls and twirls and falls completely away.”

Jesús Orta Ruiz 30 de septiembre de 1922, La Habana, †30 de diciembre de 2005, La Habana, también conocido con el sobrenombre de “Indio Naborí”, es un destacado poeta y decimista cubano, que desarrolló una gran popularidad en su tierra natal. Nació y se crió en una familia campesina conservadora de las tradiciones y folclore de origen español en los campos de Cuba, tradiciones llevadas a la isla por sus bisabuelos (quienes eran originarios de las Islas Canarias). De ahí que el punto de partida de su vocación poética, manifiesta precozmente, no podía ser otro que la décima, folclorizada en el canto de los labradores cubanos. Desde los nueve años de edad la improvisaba.

Caroline Elizabeth Sarah Norton (22 March 1808 – 15 June 1877) was an English social reformer, and author of the early and mid-nineteenth century. Caroline left her husband in 1836, following which her husband sued her close friend Lord Melbourne, the then Whig Prime Minister, for criminal conversation. The jury threw out the claim, but Caroline was unable to obtain a divorce and was denied access to her three sons. Caroline's intense campaigning led to the passing of the Custody of Infants Act 1839, the Matrimonial Causes Act 1857 and the Married Women's Property Act 1870. Caroline modelled for the fresco of Justice in the House of Lords by Daniel Maclise, who chose her because she was seen by many as a famous victim of injustice.

Sarojini Naidu (née Chattopadhyaya; 13 February 1879 – 2 March 1949), also known by the sobriquet The Nightingale of India (Bharatiya Kokila), was a child prodigy, Indian independence activist and poet. Naidu was the second Indian woman to become the President of the Indian National Congress and the first woman to become the Governor of Uttar Pradesh state. Her birthday is celebrated as Women's Day in India. Early years Sarojini Chattopadhyay, later Naidu, belonged to a Bengali family of Kulin Brahmins. She was born in Hyderabad, India as the eldest daughter of scientist, philosopher, linguist and educator Aghornath Chattopadhyaya, and Barada Sundari Devi, a Bengali poetess. After receiving a doctor of science degree from Edinburgh University, her father settled in Hyderabad State, where he founded and administered the Hyderabad College, which later became the Nizam College in Hyderabad. Her father was a linguist and thinker, and the first member of Indian National Congress in Hyderabad. Her mother, Barada Sundari Devi, was a poetess baji and used to write poetry in Bengali. Sarojini Naidu was the eldest among the eight siblings. One of her brothers Birendranath was a revolutionary and her other brother Harindranath was a poet, dramatist, and actor. Education Sarojini Naidu was a brilliant student. She was proficient in Urdu, Telugu, English, Bengali, and Persian. At the age of 12, Sarojini Naidu attained national fame when she topped the matriculation examination at Madras University. Her father wanted her to become a mathematician or scientist but Sarojini Naidu was interested in poetry. She started writing poems in English. Impressed by her play Maher Muneer, the Nizam of Hyderabad gave her scholarship to study abroad. At the age of 16, she traveled to England to study first at King's College London and later at Girton College, Cambridge. There she met famous laureates of her time such as Arthur, Symons and Edmond Gosse. It was Gosse who convinced Sarojini to stick to Indian themes-India's great mountains, rivers, temples, social milieu, to express her poetry. She depicted contemporary Indian life and events. Her collections "The golden threshold (1905)", "The bird of time (1912)", and "The broken wing (1912)" attracted huge Indian and English readership. Indian Freedom Fighter Sarojini Naidu joined the Indian national movement in the wake of partition of Bengal in 1905. She came into contact with Gopal Krishna Gokhale, Rabindranath Tagore, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Annie Besant, C. P. Ramaswami Iyer, Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru. During 1915-1918, she traveled to different regions in India delivering lectures on social welfare, women empowerment, and nationalism. She awakened the women of India and brought them out of the kitchen. She also helped to establish the Women's Indian Association (WIA) in 1917. She was sent to London along with Annie Besant, President of WIA, to present the case for the women's vote to the Joint Select Committee. President of the Congress In 1925, Sarojini Naidu presided over the annual session of Indian National Congress at Kanpur. In 1929, she presided over East African Indian Congress in South Africa. She was awarded the Kaiser-i-Hind medal by the British government for her work during the plague epidemic in India. In 1931, she participated in the Round table conference with Gandhiji and Madan Mohan Malaviya. Sarojini Naidu played a leading role during the Civil Disobedience Movement and was jailed along with Gandhiji and other leaders. In 1942, Sarojini Naidu was arrested during the "Quit India" movement and was jailed for 21 months with Gandhiji. She shared a very warm relationship with Gandhiji and used to call him "Mickey Mouse". Literary career Sarojini Naidu began writing at the age of 12. Her play, Maher Muneer, impressed the Nawab of Hyderabad. In 1905, her collection of poems, named "The Broken Wings" was published. Her poems were admired by many prominent Indian politicians like Gopala Krishna Gokhale and Jawaharlal Nehru.

Ernesto Noboa y Caamaño nació en Guayaquil, de igual manera que su compañero Arturo Borja, procedía de una familia notable. Cumplió su educación media, se estableció con sus padres en la ciudad de Quito, en donde su aleteo poético, fue cobrando altura a través de periódicos y revistas. Pero su fama se extendía también al auxilio de las reuniones amicales en las que declamaba lo propio y lo ajeno, en noches de bohemia en que no faltaba la excitación letal de los paraísos artificiales. “De que vale un ansia viva de fe y amor, y ser sincero y fuerte, si la vida es tan sólo una furtiva lágrima en las pupilas de la muerte”

I was born in the country of Brazil. When, I don't quite know, but I do know that I was born in the streets of Rio des Janeiro to a teenage mother. I was adopted by a Christian American family, at about 5 yrs of age, where I was asked to make up a name, age, and birth date. Since I was a child in a foreign country with no one to communicate with, I gravitated towards grammar and language. For some reason, I was able to comprehend the English language and structure more easily through poetry. My favorite being, Robert Frost! I love poetry cause in a way, it explains an emotion, thought, or just plain life, in ways no other written language can! I'm so thankful for sights like these. It's sad because poetry, I believe, is becoming a dying art. Sights like these keep it alive and well with fans and poets like ourselves!

Edith Nesbit (married name Edith Bland; 15 August 1858 – 4 May 1924) was an English author and poet; she published her books for children under the name of E. Nesbit. She wrote or collaborated on more than 60 books of fiction for children. She was also a political activist and co-founded the Fabian Society, a socialist organisation later affiliated to the Labour Party.

Manuel Gutiérrez Nájera (22 de diciembre de 1859 - 3 de febrero de 1895) fue un escritor, poeta y periodista mexicano, nació y vivió en la Ciudad de México como observador cronista. Utilizó múltiples seudónimos, no obstante, entre sus contertulios y el público, el que más arraigado quedó fue: El Duque Job. Precursor del modernismo en México. Perteneció a una familia de clase media. Escritor y periodista toda su vida. Inició su carrera a los trece años. Escribió poesía, impresiones de teatro, crítica literaria y social, notas de viajes y relatos breves para niños. El único libro que vio publicado el duque en vida, fue una antología de cuentos a la que llamó: Cuentos Frágiles (1883); fue uno de los fundadores de la Revista Azul, órgano de difusión del modernismo en México. Gran parte de su obra apareció en diversos periódicos mexicanos bajo multitud de seudónimos: El Cura de Jalatlaco, El Duque Job, Puck, Junius, Recamier, Mr. Can-Can, Nemo, Omega, etc. Se escudaba en esa diversidad para publicar distintas versiones de un mismo trabajo, cambiando la firma y jugando a adaptar el estilo del texto a cada seudónimo. Escribió poesía romántica y amorosa. Gustó de lo afrancesado y de lo clásico, como era habitual en los intelectuales mexicanos y la alta sociedad de su tiempo. Nunca salió de México, y en pocas ocasiones de su ciudad natal, pero sus influencias son europeas: Musset, Gautier, Baudelaire, Flaubert, Leopardi.1 Siempre anheló unir el espíritu francés y las formas españolas. Su madre, ferviente católica empeñada en que su hijo fuera sacerdote, le impuso la lectura de los místicos españoles del Siglo de Oro y la formación en el seminario, influencia que se vio compensada por la fuerte corriente positivista de la sociedad de la época que pugnaba en sentido contrario. Gutiérrez Nájera abandonó el seminario a los pocos años, y cambió a San Juan de la Cruz, Santa Teresa y Fray Luis de León, que no obstante siempre influirían en su obra, por los autores franceses del siglo y por la práctica cotidiana de la literatura en periódicos locales como El Federalista, La Libertad, El Cronista Mexicano o El Universal. En 1894 fundó, con Carlos Díaz Dufoo, La Revista Azul, publicación que lideró el modernismo mexicano durante dos años. A Manuel Gutiérrez Nájera se le define como «especie de sonrisa del alma» por la gracia sutil de su estilo, elegante, delicado y con ternura de sentimientos. En el fondo fue siempre poeta romántico. Entre sus obras poéticas más importantes se encuentran: La Duquesa Job, Hamlet a Ofelia, Odas Breves, La Serenata de Schubert y el afamado poema «Non omnis moriar» (No moriré del todo). Cultivó la prosa en cuentos, a los que aportó una nueva forma, y en crónicas: el libro de relatos Cuentos Frágiles fue el único que publicó en vida como tal, pero ordenó con distintos criterios sus entregas a periódicos y revistas: Cuentos del domingo, Cuentos vistos, Cuentos color de humo, Crónicas color de oro, Crónicas color de lluvia, etc. lo que ha orientado los criterios de sus editores. Referencias Wikipedia - http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manuel_Gutiérrez_Nájera

Hi, my name Is Variksha. I'm from South Africa. I have a passion for writing,I love writing poems,stories & lyrics. I write about anything and everything that comes to mind,I love writing from my heart,I write about my experiences as well about experiences of close friends & relatives. Please feel free to facebook me,email or tweet me,you may comment on my poems,it's always good to get different opinions,I'm open minded & cool so don't be afraid to say what you really think of my work. Much love <3 Xoxo

Rubén Bonifaz Nuño (Córdoba, 12 de noviembre de 1923 - México D. F., 31 de enero de 2013) fue un poeta y clasicista mexicano. Bonifaz Nuño nació en Córdoba (Veracruz) y estudió derecho en la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) entre 1940 y 1947. En 1960, empezó a enseñar latín en la Facultad de Filosofía y Letras de la UNAM y recibió un doctorado en Arte y cultura clásica en 1970. Bonifaz Nuño ha publicado traducciones de las obras de Catulo, Propercio, Lucrecio: De la natura de las cosas, Píndaro, Ovidio: Metamorfosis, Arte de amar y Remedios del amor, Lucano, Virgilio: La Eneida y las Geórgicas, Julio César: Guerra gálica, Cicerón: Acerca de los deberes y otros autores clásicos al español. Su traducción de 1973 de la Eneida fue aclamada por la crítica. Fue elegido miembro de número de la Academia Mexicana de la Lengua el 19 de agosto de 1962, tomando posesión de la silla V el 30 de agosto de 1963. Bonifaz renunció al cargo el 26 de julio de 1996.1 Fue admitido en el Colegio Nacional en 1972 con el discurso de ingreso "La fundación de la ciudad".2 Fue ganador del Premio Nacional de Literatura y Lingüística en 1974. Rubén Bonifaz Nuño murió en la ciudad de México el 31 de enero de 2013. Traducciones * Eneida (1973) * Arte de amar, Remedios del amor (1975) * Metamorfosis (1979) *De la natura de las cosas (1984) *Hipólito (1998) *Ilíada (2008) Ensayos * El amor y la cólera: Cayo Valerio Catulo (1977) * Los reinos de Cintia. Sobre Propercio (1978) Poesía * La muerte del ángel (1945) * Imágenes (1953) * Los demonios y los días (1956) * El manto y la corona (1958) * Canto llano a Simón Bolívar (1958) * Fuego de pobres (1961) * Siete de espadas (1966) * El ala del tigre (1969) * La flama en el espejo (1971) * Tres poemas de antes (1978) * As de oros (1981) * El corazón de la espiral (1983) * Albur de amor (1987) * Pulsera para Lucía Méndez (1989) * Del templo de su cuerpo (1992 * Trovas del mar unido (1994). Referencias Wikipedia - http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rubén_Bonifaz_Nuño

Alfred Noyes CBE (16 September 1880– 25 June 1958) was an English poet, short-story writer and playwright, best known for his ballads, “The Highwayman” and “The Barrel-Organ”. Early years Noyes was born in Wolverhampton, England, the son of Alfred and Amelia Adams Noyes. When he was four, the family moved to Aberystwyth, Wales, where his father taught Latin and Greek. The Welsh coast and mountains were an early inspiration to Noyes. In 1898, he left Aberystwyth for Exeter College, Oxford, where he distinguished himself at rowing, but failed to get his degree because, on a crucial day of his finals in 1903, he was meeting his publisher to arrange publication of his first volume of poems, The Loom of Years (1902). From 1903 to 1913, Noyes published five additional volumes of poetry, among them The Flower of Old Japan (1903) and Poems (1904), which included one of his most popular poems, “The Barrel-Organ”. His most famous poem, “The Highwayman”, was first published in the August 1906 issue of Blackwood’s Magazine, and included the following year in Forty Singing Seamen and Other Poems. In a nationwide poll conducted by the BBC in 1995 to find Britain’s favourite poem, “The Highwayman” was voted the nation’s 15th favourite poem. Noyes’ major work in this phase of his career was Drake, a 200-page epic in blank verse about the Elizabethan naval commander Sir Francis Drake, which was published in two volumes (1906 and 1908). Both in style and subject, the poem shows the clear influence of Romantic poets such as Tennyson and Wordsworth. Noyes’ only full-length play, Sherwood, was published in 1911; it was reissued in 1926, with alterations, as Robin Hood. One of his most popular poems, “A Song of Sherwood”, also dates from 1911. He published in 1913 another long poem, Tales of the Mermaid Tavern, which evokes several of the great figures of the Elizabethan era, among them Shakespeare, Jonson, Marlowe and Raleigh. First marriage and America In 1907, Noyes married Garnett Daniels, youngest daughter of US Army Colonel Byron G. Daniels, a Civil War veteran who was for some years US Consul at Hull. Noyes first visited America in February 1913, partly to lecture on world peace and disarmament and partly to satisfy his wife’s desire that he should gather fresh experiences in her homeland. His first lecture tour lasted six weeks, extending as far west as Chicago. It proved so successful that he decided to make a second trip to the US in October and to stay six months. In this trip, he visited the principal American universities, including Princeton, where the impression he made on the faculty and undergraduates was so favourable that in February 1914 he was asked to join the staff as a visiting professor, lecturing on modern English literature from February to June. He accepted, and for the next nine years he and his wife divided their year between England and the US. At Princeton, Noyes’ students included F. Scott Fitzgerald, Edmund Wilson and John Peale Bishop. He resigned his professorship in 1923, but continued to travel and lecture throughout the United States for the rest of his life. His wife died in 1926 at Saint-Jean-de-Luz, France, where she and Noyes were staying with friends. War Noyes is often portrayed by hostile critics as a militarist and jingoist. Actually, he was a pacifist who hated war and lectured against it, but felt that, when threatened by an aggressive and unreasoning enemy, a nation could not but fight. On this principle, he opposed the Boer War, but supported the Allies in both the World Wars. In 1913, when it seemed that war might yet be avoided, he published a long anti-war poem called The Wine Press. One American reviewer wrote that Noyes was “inspired by a fervent hatred of war and all that war means”, and had used “all the resources of his varied art” to depict its “ultimate horror”. The poet and critic Helen Bullis found Noyes’ “anti-militarist” poem “remarkable”, “passionate and inspiring”, but, in its “unsparing realism”, lacking in “the large vision, which sees the ultimate truth rather than the immediate details”. In her view, Noyes failed to address the “vital questions” raised, for example, by William James’ observation that for modern man, “War is the strong life; it is life in extremis”, or by John Fletcher’s invocation in The Two Noble Kinsmen of war as the “great corrector” that heals and cures “sick” times. Bullis, a Freudian (unlike Noyes, for whom psychoanalysis was a pseudo-science), thought war had deeper roots than Noyes acknowledged. She saw looming “the great figures of the Fates back of the conflict, while Mr Noyes sees only the 'five men in black tail-coats’ whose cold statecraft is responsible for it”. In 1915, Upton Sinclair included some striking passages from The Wine Press in his anthology of the literature of social protest, The Cry for Justice. During World War I, Noyes was debarred by defective eyesight from serving at the front. Instead, from 1916, he did his military service on attachment to the Foreign Office, where he worked with John Buchan on propaganda. He also did his patriotic chore as a literary figure, writing morale-boosting short stories and exhortatory odes and lyrics recalling England’s military past and asserting the morality of her cause. These works are now forgotten, apart from two ghost stories, “The Lusitania Waits” and “The Log of the Evening Star”, which are still occasionally reprinted in collections of tales of the uncanny. “The Lusitania Waits” is a ghost revenge story based on the sinking of the Lusitania by a German submarine in 1915—although the tale hinges on an erroneous claim that the submarine crew had been awarded the Goetz medal for sinking the ship. During World War II, Noyes wrote the same kind of patriotic poems, but he also wrote a much longer and more considered work, If Judgement Comes, in which Hitler stands accused before the tribunal of history. It was first published separately (1941) and then in the collection, Shadows on the Down and Other Poems (1945). The only fiction Noyes published in World War II was The Last Man (1940), a science fiction novel whose message could hardly be more anti-war. In the first chapter, a global conflict wipes out almost the entire human race. Noyes’ best-known anti-war poem, “The Victory Ball” (aka “A Victory Dance”), was first published in The Saturday Evening Post in 1920. He wrote it after attending a ball held in London soon after the Armistice, where he found himself wondering what the ghosts of the soldiers who had died in the war would say if they could observe the thoughtless frivolity of the dancers. The message of the poem lies in the line, “Under the dancing feet are the graves.” A brief passage about a girl “fresh from school” who “begs for a dose of the best cocaine” was replaced by something innocuous in the Post version, but reinstated when the poem appeared in a collection of Noyes’ verse. “The Victory Ball” was turned into a symphonic poem by Ernest Schelling and into a ballet by Benjamin Zemach. In 1966, at the height of the Vietnam War, Congressman H. R. Gross, indignant at a White House dinner dance that went on until 3 a.m. while American soldiers were giving their lives, inserted Noyes’ poem in the Congressional Record as bearing “directly on the subject matter in hand”. Middle years In 1918, Noyes’ short story collection, Walking Shadows: Sea Tales and Others, came out. It included both “The Lusitania Waits” and “The Log of the Evening Star”. In 1924 Noyes published another collection, The Hidden Player, which included a novella, Beyond the Desert: A Tale of Death Valley, already published separately in America in 1920. For the Pageant of Empire at the 1924 British Empire Exhibition, Noyes wrote a series of poems set to music by Sir Edward Elgar and known as Pageant of Empire. Among these poems was Shakespeare’s Kingdom. In 1929, Noyes published the first of his three novels, The Return of the Scare-Crow (US title: The Sun Cure). A light-hearted story combining adventure, satire and comedy, it is about an earnest young clergyman named Basil who decides to take the sun cure to get over his infatuation with a beautiful girl and inadvertently ends up in a nudist camp. Having lost his clothes, he has to battle his way back to them through a terrifying series of mental hazards—all the latest intellectual fads and follies—and ends up rather less naïve than before. Second marriage and Catholicism In 1927, the year after his first wife’s death, Noyes married Mary Angela née Mayne (1889–1976), widow of Lieutenant Richard Shireburn Weld-Blundell, a member of the old recusant Catholic Weld-Blundell family, who had been killed in World War I. Later that year, Noyes himself converted to Catholicism. He gives an account of his conversion in his autobiography, Two Worlds for Memory (1953), but sets forth the more intellectual steps by which he was led from agnosticism to the Catholic faith in The Unknown God (1934), a widely read work of Christian apologetics which has been described as “the spiritual biography of a generation”. In 1929, Noyes and Mary Angela settled at Lisle Combe, on the Undercliff near Ventnor, Isle of Wight. They had three children: Hugh (1929–2000), Veronica and Margaret. Noyes’ younger daughter married Michael Nolan (later Lord Nolan) in 1953. The Torch-Bearers Noyes’ ambitious epic verse trilogy The Torch-Bearers– comprising Watchers of the Sky (1922), The Book of Earth (1925) and The Last Voyage (1930)– deals with the history of science. In the “Prefatory Note” to Watchers of the Sky, Noyes expresses his purpose in writing the trilogy: This volume, while it is complete in itself, is also the first of a trilogy, the scope of which is suggested in the prologue. The story of scientific discovery has its own epic unity– a unity of purpose and endeavour– the single torch passing from hand to hand through the centuries; and the great moments of science when, after long labour, the pioneers saw their accumulated facts falling into a significant order– sometimes in the form of a law that revolutionised the whole world of thought– have an intense human interest, and belong essentially to the creative imagination of poetry. It is with these moments that my poem is chiefly concerned, not with any impossible attempt to cover the whole field or to make a new poetic system, after the Lucretian model, out of modern science. Watchers of the Sky Noyes adds that the theme of the trilogy had long been in his mind, but the first volume, dealing with Watchers of the Sky, began to take definite shape only on the night of 1/2 November 1917, when the 100-inch reflecting telescope at Mount Wilson Observatory was first tested by starlight. George Ellery Hale, the man who conceived and founded the observatory, had invited Noyes, who was then in California, to be his guest on this momentous occasion, and the prologue, subtitled “The Observatory”, gives Noyes’ detailed description of that “unforgettable... night”. In his review of Watchers of the Sky, the scholar and historian of science Frederick E. Brasch writes that Noyes’ “journey up to the mountain’s top, the observatory, the monastery, telescopes and mirrors, clockwork, switchboard, the lighted city below, planets and stars, atoms and electrons all are woven into... beautiful narrative poetry. It seems almost incredible that technical terms and concepts could lend themselves for that purpose.” After the prologue come seven long poems, each of which depicts salient episodes in the career of a major scientist, so as to bring out both the “intensely human drama” ("Prefatory Note") of his life and his contribution to astronomy. Noyes’ seven scientists are Nicolaus Copernicus, Tycho Brahe, Johannes Kepler, Galileo Galilei, Isaac Newton, and William and John Herschel– though due mention is also made of the contribution of Caroline Herschel, sister to William and aunt to John. In the epilogue, Noyes meditates once more upon the mountain in the morning, before bringing his narrative to a close in the form of a prayer. In his review, Frederick E. Brasch writes that Noyes’ “knowledge of the science of astronomy and its history... seems remarkable in one who is so entirely unrelated to the work of an observatory”. Watchers of the Sky, he adds, will no doubt appeal to the layman “for its beauty and the music of its narrative verse, broken and interspersed with epic poetry. But it remains for the astronomer and other scholars in science to enjoy it to the fullness which is adequate to Noyes’ ability as a poet.” The Book of Earth The Book of Earth is the second volume in the trilogy. In eight sections framed by a meditative prologue and epilogue, it follows the discoveries of scientists in their struggles to solve the mysteries of the earth, of life forms, and of human origins. Starting in ancient Greece with Pythagoras and Aristotle, it then moves to the Middle East for Farabi and Avicenna. The scene then shifts successively to Italy for Leonardo, France for Guettard, Sweden for Linnaeus, France again for Buffon, Lamarck, Lavoisier, and Cuvier, and then Germany for Goethe, before ending in England with Darwin. Reviewing The Book of Earth for Nature, F. S. Marvin wrote, “It deals with a much more difficult subject from the point of view of poetic presentation, namely biology, or rather geology as a preface to zoology and evolution as crowning geology.” Nevertheless, it does not “belie the... expectations” raised by its predecessor. The Last Voyage Before Noyes had begun proper work on the final volume in the trilogy, The Last Voyage, two events occurred which were to influence it greatly: his first wife’s death and his conversion to Roman Catholicism. Death is a major theme in The Last Voyage, as its very title suggests. The tone, more sombre than that of its predecessors, is also more religious—though religion was hardly absent from the earlier volumes—and, as might be expected, more specifically Catholic. The Last Voyage begins at night in mid-Atlantic, where an ocean liner, “a great ship like a lighted city”, is battling through a raging storm. A little girl is mortally ill. The ship’s surgeon prepares to operate, but with little hope of success, for the case is complicated and he is no specialist. Luckily, the captain knows from the wireless news that a top specialist from Johns Hopkins is on another liner 400 miles away– within wireless range. The ship’s surgeon will be able to consult him, and stay in touch with him throughout the operation. Suddenly, the little girl’s chances of survival are much improved. In a manner of speaking, all the scientific discoveries and inventions of the past are being brought to bear in the attempt to save her life. When the poet asks a casually-met fellow-passenger, “You think they’ll save her?” the stranger replies, “They may save her,” and then adds enigmatically, “But who are They?” Reflecting, the poet realises that They are all the seekers and discoverers of scientific truths through the ages– people like Harvey, Pasteur and Lister in the field of medicine or Faraday, Maxwell and Hertz in the development of the wireless. Nevertheless, despite the united efforts of all, the little girl dies, and in the darkness of that loss the poet finds that only in Faith can a flicker of light be found. Science cannot defeat death in the long run, and sometimes, as in the little girl’s case, not even in the short run, but if “Love, not Death” is the ultimate reality, death will not have the final word. Of course, the “last voyage” of the title is not just that of the little girl or of Noyes’ wife– though there are lyrics mourning her in Section XIII and another in the Dedication at the end– but of everyman and everywoman. F. S. Marvin, who reviewed all three volumes of The Torch-Bearers for Nature, wrote that “the third volume is certainly the best from the artistic point of view. It contains one well-conceived and highly interesting incident, around which the author’s pictures of the past and incidental lyrics are effectively grouped, and it leads up to a full and eloquent exposition of the religious synthesis with which the history of science inspires him.” The Last Man In 1940 Noyes published a science-fiction novel, The Last Man (US title: No Other Man), in which the human race is almost wiped out by a powerful death ray capable of killing everyone, friend or foe, unless they are in a steel chamber deep under the surface of the sea. The inventor’s chief assistant unscrupulously sells the plans to the leading nations of the world, who declare they will use the ray only as a “last resort”. When events spiral out of control, however, they all activate it, killing everyone living on the earth. When the death ray strikes, a 29-year-old Englishman named Mark Adams is trapped in a sunken submarine. Managing to escape, he finds himself the only survivor in Britain. He travels to Paris in the hope of finding another survivor. There he discovers a clue which gives him hope. His search leads him to Italy, where he finally finds the other survivor, an American girl named Evelyn Hamilton. At the time when the death ray struck, she was in a diving bell deep below the surface of the Mediterranean, where, under the guidance of Mardok, an immensely wealthy magnate and scientific genius, she was engaged in photographing the floor of the sea. Her companion turns out to be the villain of the story. Knowing the power of the ray, for whose development he had been largely responsible, he had made sure that, at the time of its activation, he was safely out of its reach, along with an attractive young woman with whom he could later begin the repopulation of the planet. Evelyn, however, finds him repulsive, and the arrival of the upstanding, handsome young Englishman further upsets Mardok’s plan. In the ensuing competition between the two men for the girl, Mark Adams’ surname is a clear hint at which of the two is better fitted to be Adam to Evelyn’s Eve. The two young people fall in love, but Mardok kidnaps Evelyn. After her escape and Mardok’s death, the novel concludes with the young couple’s discovery of some other survivors at Assisi. For Charles Holland, reviewing the novel in the 1940s, Noyes’ combination of “such elements of human interest as apologetics, art, travel and a captivating love story” mean that the reader of The Last Man is assured of both “an intellectual treat and real entertainment”. Eric Atlas, writing in an early science fiction fanzine, found the novel, despite some flaws, “well worth the reading– perhaps twice”. The philosophico-religious theme, he wrote, “detracts in no way from the forceful characterizations... of Mark and Evelyn”. Besides, most of the novel is set “in Italy, where Noyes’ descriptive powers as a poet come to the fore”. The Last Man seems to be the novel which introduced the idea of a doomsday weapon. It is thought to have been among the influences on George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four. Later years In 1940, Noyes returned to North America, where he lectured and advocated the British war position. The following year, he gave the Josiah Wood lectures at Mount Allison University, New Brunswick, Canada. Titled The Edge of the Abyss, they were first published in Canada in 1942 and then, in a revised version, in the United States the same year and in Britain two years later. In The Edge of the Abyss, Noyes ponders the future of the world, attacking totalitarianism, bureaucracy, the pervasive power of the state, and the collapse of moral standards. George Orwell reviewed the book for The Observer and, like The Last Man, it is considered a probable influence on Nineteen Eighty-Four. In his review, Orwell wrote that The Edge of the Abyss “raises a real problem”– the “decay in the belief in absolute good and evil”, with the result that the “rules of behaviour on which any stable society has to rest are dissolving” and “even the prudential reasons for common decency are being forgotten”. Indeed, in Orwell’s view, Noyes “probably even underemphasises the harm done to ordinary common sense by the cult of 'realism’, with its inherent tendency to assume that the dishonest course is always the profitable one”. On the other hand, Orwell finds Noyes’ suggested remedy, a return to Christianity, “doubtful, even from the point of view of practicality”. He agrees that the “real problem of our time is to restore the sense of absolute right and wrong”, which in the past had ultimately rested on “faith”, but he thinks that Noyes “is probably wrong in imagining that the Christian faith, as it existed in the past, can be restored even in Europe”. Orwell offers no suggestion, however, as to what, other than faith, could serve as a basis for morality. Noyes remained in retirement in California for some years. In 1943, he published The Secret of Pooduck Island, a children’s story set off the coast of Maine. It features a family of squirrels threatened by natural enemies (skunks, weasels) and humans, the ghost of a Native American man who suffered a terrible sorrow in the colonial era, and a teenage boy who has ambitions to be an artist and who is able to help both the squirrels and the ghost. It is, however, far more profound and terrible than the lighthearted accounts of animal behaviour seem on the surface to indicate; a mysterious voice keeps whispering words of mystery to the artist Solo, and most of the characters turn out to be incarnations of the various follies and stupidities of mankind: the fierce lonely boy-artist (who is nearly locked up as insane by the petty spiteful villagers) and the pudgy but wise priest, as well as the solemn ghost of Squando, being the only exceptions against which the others are contrasted. The entire “secret” of Pooduck Island consists in the gleams of the supernatural that blaze through the canopy of the material world, like a glimpse of the ocean through an arch in the woods that Solo names the “Eye” of the island. The mysterious Voice, who is hinted to be Glooskap himself, appears indirectly as an invisible model for a portrait of the Squirrel family, who think they are seated on a stump: but the picture records him. In 1949, Noyes returned to his home on the Isle of Wight. As a result of increasing blindness, he dictated all his subsequent works. In 1952 he brought out another book for children, Daddy Fell into the Pond and Other Poems. The title poem has remained a firm favourite with children ever since. In 2005, it was one of the few poems that featured in both of two major anthologies of poetry for children published that year, one edited by Caroline Kennedy, the other by Elise Paschen. In 1955, Noyes published the satirical fantasy novel The Devil Takes A Holiday, in which the Devil, in the guise of Mr Lucius Balliol, an international financier, comes to Santa Barbara, California, for a pleasant little holiday. He finds however, that his work is being so efficiently performed by humankind that he has become redundant. The unwonted soul-searching this leads him to is not only painful but also– owing to a tragicomic twist at the end– ultimately futile. Noyes’ last book of poetry, A Letter to Lucian and Other Poems, came out in 1956, two years before his death by polio. The Accusing Ghost In 1957, Noyes published his last book, The Accusing Ghost, or Justice for Casement (US title: The Accusing Ghost of Roger Casement). In 1916, the renowned human rights campaigner Roger Casement was hanged for his involvement in the Irish Nationalist revolt in Dublin known as the Easter Rising. To forestall calls for clemency, the British authorities showed public figures and known sympathizers selected pages from some of Casement’s diaries– known as the Black Diaries– that exposed him as a promiscuous homosexual. In an era of unthinking homophobia, this underhand tactic worked and the expected protests and petitions for Casement’s reprieve did not materialise. Among those who read these extracts was Noyes, who was then working in the News Department of the Foreign Office and who described the pages as a “foul record” of “the lowest depths that human degradation has ever touched”. Later that year in Philadelphia, when Noyes was about to give a lecture on the English poets, he was confronted by Casement’s sister, Nina, who denounced him as a “blackguardly scoundrel” and cried, “Your countrymen hanged my brother Roger Casement.” Worse was to come. After Casement’s death, the British authorities held the diaries in conditions of extraordinary secrecy, arousing strong suspicions among Casement’s supporters that they were forged. In 1936, there appeared a book by an American doctor, William J. Maloney, called The Forged Casement Diaries. After reading it, W. B. Yeats wrote a protest poem, “Roger Casement”, which was published with great prominence in The Irish Press. In the fifth stanza of the poem, Yeats named Alfred Noyes and called on him to desert the side of the forger and perjurer. Noyes immediately responded with a letter to The Irish Press in which he explained why he had assumed the diaries were authentic, confessed he might have been misled, and called for the setting up of a committee to examine the original documents and settle the matter. In response to what he called Noyes’ “noble” letter, Yeats amended his poem, removing Noyes’ name. Over twenty years later, Casement’s diaries were still being held in the same conditions of secrecy. In 1957, therefore, Noyes published The Accusing Ghost, or Justice for Casement, a stinging rebuke of British policy in which, making full amends for his previous harsh judgement, he argued that Casement had indeed been the victim of a British Intelligence plot. In 2002, a forensic examination of the Black Diaries concluded that they were authentic. Death Noyes’ last poem, Ballade of the Breaking Shell, was written in May 1958, one month before his death. He died at the age of 77, and is buried in the Roman Catholic cemetery at Freshwater, Isle of Wight. Works Poetry * The Loom of Years (1902) * The Flower of Old Japan (1903) * The Forest of Wild Thyme (1905) * The Highwayman (1906) * Drake (1906–08) * The Golden Hynde (1908) * Tales of the Mermaid Tavern (1913) * Watchers of the Sky (1922) * The Book of Earth (1925) * The Last Voyage (1930) * Shadows on the Down (1941) * Collected Poems (1950) * Daddy Fell into the Pond (1952) * A Letter to Lucian (1956) Other Works * William Morris (1908) Biography. * Rada (1914) Drama. * Walking Shadow (1906) Short Stories. * The Hidden Player (1924) Short Stories. * Some Aspects of Modern Poetry (1924) Criticism. * The Opalescent Parrot (1929) Criticism. * Orchard’s Bay (1936) Essays. * The Last Man (1940) Novel. * Pageant of Letters (1940) Criticism. * Two Worlds for Memory (1953) Autobiography. * The Accusing Ghost (1957) Films based on Noyes’ works * Dick Turpin’s Ride Songs based on Noyes’ works * Pageant of Empire References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alfred_Noyes