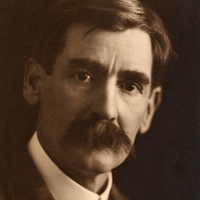

Alfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson, FRS (6 August 1809 – 6 October 1892) was Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom during much of Queen Victoria's reign and remains one of the most popular poets in the English language. A number of phrases from Tennyson’s work have become commonplaces of the English language, including “Nature, red in tooth and claw”, “'Tis better to have loved and lost / Than never to have loved at all”, “Theirs not to reason why, / Theirs but to do and die”, “My strength is as the strength of ten, / Because my heart is pure”, “Knowledge comes, but Wisdom lingers”, and “The old order changeth, yielding place to new”. He is the ninth most frequently quoted writer in The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations.

Miguel Hernández (Orihuela, 1910 – Alicante, 1942) Poeta español. Adscrito a la Generación del 27, destacó por la hondura y autenticidad de sus versos, reflejo de su compromiso social y político. Nacido en el seno de una familia humilde y criado en el ambiente campesino de Orihuela, de niño fue pastor de cabras y no tuvo acceso más que a estudios muy elementales, por lo que su formación fue autodidacta.

I am an American Patriot, a Believer, and a lover of God and Country. I am a widow, a mother of five children ❤️ and five grandchildren. ❤️ I’m very proud, and honored to have borne such loving, talented and hard working children. Being a Mother was my destiny. Being a writer is also part of my destiny that I truly thank God for. It’s a gift from God It was after my children were grown and left home that I became serious about writing. I have written a book titled (American Poetry and Music) that has been published by Christian Faith Publishing. Which can be purchased on Amazon.com, Barnes and Noble, and Thrift Books.com I get my inspiration from the Creator, and I go under the heading of H.S.I. Which stands for (Holy Spirit Inspiration) Some of these poems on Poeticous.com appear in my book . I am grateful for them allowing me to publish my poems on this site also. I’ve come to love this site very much. All Poems, and Original Music Videos on this site are my own original compositions, and are covered under U.S.Copyright laws.© 2024. For more info -You can find me on (Youtube) and (Facebook). Email no longer public, but if you message me from Facebook or here on Poeticous I’ll give it to you privately. No copyright infringement intended with any Pictures or videos used on these poetry pages. Some videos of artist I enjoy were obtained from Youtube, and some pictures are from Public Domain sites. Mostly they are the property of Poeticous I do not claim rights for any works except my own Original Work. Thank you, Charlotte B. Williams

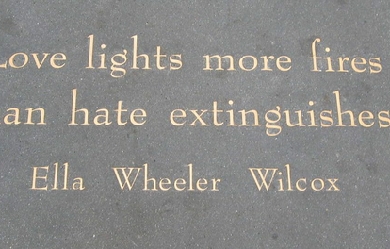

Ella Wheeler Wilcox (November 5, 1850– October 30, 1919) was an American author and poet. Her best-known work was Poems of Passion. Her most enduring work was “Solitude”, which contains the lines, “Laugh, and the world laughs with you; weep, and you weep alone”. Her autobiography, The Worlds and I, was published in 1918, a year before her death. Biography Ella Wheeler was born in 1850 on a farm in Johnstown, Wisconsin, east of Janesville, the youngest of four children. The family soon moved north of Madison. She started writing poetry at a very early age, and was well known as a poet in her own state by the time she graduated from high school. Her most famous poem, “Solitude”, was first published in the February 25, 1883 issue of The New York Sun. The inspiration for the poem came as she was travelling to attend the Governor’s inaugural ball in Madison, Wisconsin. On her way to the celebration, there was a young woman dressed in black sitting across the aisle from her. The woman was crying. Miss Wheeler sat next to her and sought to comfort her for the rest of the journey. When they arrived, the poet was so depressed that she could barely attend the scheduled festivities. As she looked at her own radiant face in the mirror, she suddenly recalled the sorrowful widow. It was at that moment that she wrote the opening lines of “Solitude”: Laugh, and the world laughs with you; Weep, and you weep alone. For the sad old earth must borrow its mirth But has trouble enough of its own She sent the poem to the Sun and received $5 for her effort. It was collected in the book Poems of Passion shortly after in May 1883. In 1884, she married Robert Wilcox of Meriden, Connecticut, where the couple lived before moving to New York City and then to Granite Bay in the Short Beach section of Branford, Connecticut. The two homes they built on Long Island Sound, along with several cottages, became known as Bungalow Court, and they would hold gatherings there of literary and artistic friends. They had one child, a son, who died shortly after birth. Not long after their marriage, they both became interested in theosophy, new thought, and spiritualism. Early in their married life, Robert and Ella Wheeler Wilcox promised each other that whoever went first through death would return and communicate with the other. Robert Wilcox died in 1916, after over thirty years of marriage. She was overcome with grief, which became ever more intense as week after week went without any message from him. It was at this time that she went to California to see the Rosicrucian astrologer, Max Heindel, still seeking help in her sorrow, still unable to understand why she had no word from her Robert. She wrote of this meeting: In talking with Max Heindel, the leader of the Rosicrucian Philosophy in California, he made very clear to me the effect of intense grief. Mr. Heindel assured me that I would come in touch with the spirit of my husband when I learned to control my sorrow. I replied that it seemed strange to me that an omnipotent God could not send a flash of his light into a suffering soul to bring its conviction when most needed. Did you ever stand beside a clear pool of water, asked Mr. Heindel, and see the trees and skies repeated therein? And did you ever cast a stone into that pool and see it clouded and turmoiled, so it gave no reflection? Yet the skies and trees were waiting above to be reflected when the waters grew calm. So God and your husband’s spirit wait to show themselves to you when the turbulence of sorrow is quieted. Several months later, she composed a little mantra or affirmative prayer which she said over and over “I am the living witness: The dead live: And they speak through us and to us: And I am the voice that gives this glorious truth to the suffering world: I am ready, God: I am ready, Christ: I am ready, Robert.”. Wilcox made efforts to teach occult things to the world. Her works, filled with positive thinking, were popular in the New Thought Movement and by 1915 her booklet, What I Know About New Thought had a distribution of 50,000 copies, according to its publisher, Elizabeth Towne. The following statement expresses Wilcox’s unique blending of New Thought, Spiritualism, and a Theosophical belief in reincarnation: “As we think, act, and live here today, we built the structures of our homes in spirit realms after we leave earth, and we build karma for future lives, thousands of years to come, on this earth or other planets. Life will assume new dignity, and labor new interest for us, when we come to the knowledge that death is but a continuation of life and labor, in higher planes”. Her final words in her autobiography The Worlds and I: “From this mighty storehouse (of God, and the hierarchies of Spiritual Beings ) we may gather wisdom and knowledge, and receive light and power, as we pass through this preparatory room of earth, which is only one of the innumerable mansions in our Father’s house. Think on these things”. Ella Wheeler Wilcox died of cancer on October 30, 1919 in Short Beach. Poetry A popular poet rather than a literary poet, in her poems she expresses sentiments of cheer and optimism in plainly written, rhyming verse. Her world view is expressed in the title of her poem “Whatever Is—Is Best”, suggesting an echo of Alexander Pope’s “Whatever is, is right,” a concept formally articulated by Gottfried Leibniz and parodied by Voltaire’s character Doctor Pangloss in Candide. None of Wilcox’s works were included by F. O. Matthiessen in The Oxford Book of American Verse, but Hazel Felleman chose no fewer than fourteen of her poems for Best Loved Poems of the American People, while Martin Gardner selected “The Way Of The World” and “The Winds of Fate” for Best Remembered Poems. She is frequently cited in anthologies of bad poetry, such as The Stuffed Owl: An Anthology of Bad Verse and Very Bad Poetry. Sinclair Lewis indicates Babbitt’s lack of literary sophistication by having him refer to a piece of verse as “one of the classic poems, like 'If’ by Kipling, or Ella Wheeler Wilcox’s ‘The Man Worth While.’” The latter opens: It is easy enough to be pleasant, When life flows by like a song, But the man worth while is one who will smile, When everything goes dead wrong. Her most famous lines open her poem “Solitude”: Laugh and the world laughs with you, Weep, and you weep alone; The good old earth must borrow its mirth, But has trouble enough of its own. “The Winds of Fate” is a marvel of economy, far too short to summarize. In full: One ship drives east and another drives west With the selfsame winds that blow. ’Tis the set of the sails, And Not the gales, That tell us the way to go. Like the winds of the sea are the ways of fate; As we voyage along through life, ’Tis the set of a soul That decides its goal, And not the calm or the strife. Ella Wheeler Wilcox cared about alleviating animal suffering, as can be seen from her poem, “Voice of the Voiceless”. It begins as follows: So many gods, so many creeds, So many paths that wind and wind, While just the art of being kind Is all the sad world needs. I am the voice of the voiceless; Through me the dumb shall speak, Till the deaf world’s ear be made to hear The wrongs of the wordless weak. From street, from cage, and from kennel, From stable and zoo, the wail Of my tortured kin proclaims the sin Of the mighty against the frail.

Pedro Salinas Serrano (Madrid, 27 de noviembre de 1891 – Boston, 4 de diciembre de 1951) fue un escritor español conocido sobre todo por su poesía y ensayos. Dentro del contexto de la Generación del 27, se le considera uno de sus mayores poetas. Sus traducciones de Proust contribuyeron al conocimiento del novelista francés en el mundo hispanohablante. Al concluir la guerra civil española, se exilió en Estados Unidos hasta su muerte.

Francisco Gómez de Quevedo Villegas y Santibáñez Cevallos (Madrid, 14 de septiembre de 15801-Villanueva de los Infantes, Ciudad Real, 8 de septiembre de 1645) fue un noble, político y escritor español del Siglo de Oro. Fue caballero de la Orden de Santiago a partir de 16182 y señor de Torre de Juan Abad a partir de 1620.3 Junto con Luis de Góngora, con quien mantuvo una enemistad durante toda su vida, es reconocido como uno de los más notables poetas de la literatura española. Además de su poesía, fue un prolífico escritor de narrativa y teatro, así como de textos filosóficos y humanísticos. Salutación Mi señor don Francisco de Quevedo y Villegas, que con el verso esgrimes y con la esgrima juegas, haciendo –para orgullo del verso y de la esgrima– donaire del acero y acero de la rima: caballero bizarro de las nocturnas bregas, sabias prosas y empresas galantes y andariegas; cuya torcida planta huella la noble cima cortesana y el fondo canalla de la sima plebeya, con la misma genial desenvoltura: hidalgo aventurero de múltiple aventura (amor, poder, intriga, presión, peligro), terso, leal, como tu espada de amigo y de enemigo: en mi siniestra Torre de Juan Abad bendigo tu nombre, Caballero se Santiago y del Verso. —Alfredo Arvelo Larriva

Love is the essence of pure thought. There is nowhere that this thought is not. I grew up in a small town in Oklahoma, just beyond the outskirts of several gypsum plateaus, miles of desert sand and vast horizons. I would go out into fields of sunflowers with my pen and paper, watching the currents of wind moving through miles and miles of wheat to write about the lucid imagery I would see when I closed my eyes, the experiences of coming out in a conservative community and finding my way as an artist in a place that did not nurture the arts. Words have always been my primary way to sort out my experiences into streams of consciousness that act as a form of self-discovery. Called by the overwhelming pull to follow my dreams, I relocated to the Catskills to follow my passions and put every idea into motion. I am currently working on several video projects, performances in several venues, live music, Sparkle Poetic radio ads, and many new things that you can keep up with on my website below. Welcome to the realm of words. Love is real. www.sparklepoetics.com

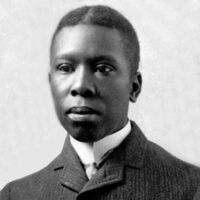

Paul Laurence Dunbar was the first African-American poet to garner national critical acclaim. Born in Dayton, Ohio, in 1872, Dunbar penned a large body of dialect poems, standard English poems, essays, novels and short stories before he died at the age of 33. His work often addressed the difficulties encountered by members of his race and the efforts of African-Americans to achieve equality in America. He was praised both by the prominent literary critics of his time and his literary contemporaries. Dunbar was born on June 27, 1872, to Matilda and Joshua Dunbar, both natives of Kentucky. His mother was a former slave and his father had escaped from slavery and served in the 55th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment and the 5th Massachusetts Colored Cavalry Regiment during the Civil War. Matilda and Joshua had two children before separating in 1874. Matilda also had two children from a previous marriage. The family was poor, and after Joshua left, Matilda supported her children by working in Dayton as a washerwoman. One of the families she worked for was the family of Orville and Wilbur Wright, with whom her son attended Dayton's Central High School. Though the Dunbar family had little material wealth, Matilda, always a great support to Dunbar as his literary stature grew, taught her children a love of songs and storytelling. Having heard poems read by the family she worked for when she was a slave, Matilda loved poetry and encouraged her children to read. Dunbar was inspired by his mother, and he began reciting and writing poetry as early as age 6. Dunbar was the only African-American in his class at Dayton Central High, and while he often had difficulty finding employment because of his race, he rose to great heights in school. He was a member of the debating society, editor of the school paper and president of the school's literary society. He also wrote for Dayton community newspapers. He worked as an elevator operator in Dayton's Callahan Building until he established himself locally and nationally as a writer. He published an African-American newsletter in Dayton, the Dayton Tattler, with help from the Wright brothers. His first public reading was on his birthday in 1892. A former teacher arranged for him to give the welcoming address to the Western Association of Writers when the organization met in Dayton. James Newton Matthews became a friend of Dunbar's and wrote to an Illinois paper praising Dunbar's work. The letter was reprinted in several papers across the country, and the accolade drew regional attention to Dunbar; James Whitcomb Riley, a poet whose works were written almost entirely in dialect, read Matthew's letter and acquainted himself with Dunbar's work. With literary figures beginning to take notice, Dunbar decided to publish a book of poems. Oak and Ivy, his first collection, was published in 1892. Though his book was received well locally, Dunbar still had to work as an elevator operator to help pay off his debt to his publisher. He sold his book for a dollar to people who rode the elevator. As more people came in contact with his work, however, his reputation spread. In 1893, he was invited to recite at the World's Fair, where he met Frederick Douglass, the renowned abolitionist who rose from slavery to political and literary prominence in America. Douglass called Dunbar "the most promising young colored man in America." Dunbar moved to Toledo, Ohio, in 1895, with help from attorney Charles A. Thatcher and psychiatrist Henry A. Tobey. Both were fans of Dunbar's work, and they arranged for him to recite his poems at local libraries and literary gatherings. Tobey and Thatcher also funded the publication of Dunbar's second book, Majors and Minors. It was Dunbar's second book that propelled him to national fame. William Dean Howells, a novelist and widely respected literary critic who edited Harper's Weekly, praised Dunbar's book in one of his weekly columns and launched Dunbar's name into the most respected literary circles across the country. A New York publishing firm, Dodd Mead and Co., combined Dunbar's first two books and published them as Lyrics of a Lowly Life. The book included an introduction written by Howells. In 1897, Dunbar traveled to England to recite his works on the London literary circuit. His national fame had spilled across the Atlantic. After returning from England, Dunbar married Alice Ruth Moore, a young writer, teacher and proponent of racial and gender equality who had a master's degree from Cornell University. Dunbar took a job at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. He found the work tiresome, however, and it is believed the library's dust contributed to his worsening case of tuberculosis. He worked there for only a year before quitting to write and recite full time. In 1902, Dunbar and his wife separated. Depression stemming from the end of his marriage and declining health drove him to a dependence on alcohol, which further damaged his health. He continued to write, however. He ultimately produced 12 books of poetry, four books of short stories, a play and five novels. His work appeared in Harper's Weekly, the Sunday Evening Post, the Denver Post, Current Literature and a number of other magazines and journals. He traveled to Colorado and visited his half-brother in Chicago before returning to his mother in Dayton in 1904. He died there on Feb. 9, 1906. Literary style Dunbar's work is known for its colorful language and a conversational tone, with a brilliant rhetorical structure. These traits were well matched to the tune-writing ability of Carrie Jacobs-Bond (1862–1946), with whom he collaborated. Use of dialect Much of Dunbar's work was authored in conventional English, while some was rendered in African-American dialect. Dunbar remained always suspicious that there was something demeaning about the marketability of dialect poems. One interviewer reported that Dunbar told him, "I am tired, so tired of dialect", though he is also quoted as saying, "my natural speech is dialect" and "my love is for the Negro pieces". Though he credited William Dean Howells with promoting his early success, Dunbar was dismayed by his demand that he focus on dialect poetry. Angered that editors refused to print his more traditional poems, he accused Howells of "[doing] my irrevocable harm in the dictum he laid down regarding my dialect verse." Dunbar, however, was continuing a literary tradition that used Negro dialect; his predecessors included Mark Twain, Joel Chandler Harris, and George Washington Cable. Two brief examples of Dunbar's work, the first in standard English and the second in dialect, demonstrate the diversity of the poet's production: (From "Dreams") What dreams we have and how they fly Like rosy clouds across the sky; Of wealth, of fame, of sure success, Of love that comes to cheer and bless; And how they wither, how they fade, The waning wealth, the jilting jade — The fame that for a moment gleams, Then flies forever, — dreams, ah — dreams! (From "A Warm Day In Winter") "Sunshine on de medders, Greenness on de way; Dat's de blessed reason I sing all de day." Look hyeah! What you axing'? What meks me so merry? 'Spect to see me sighin' W'en hit's wa'm in Febawary? List of works * Oak and Ivy (1892) * Majors and Minors (1896) * Lyrics of Lowly Life (1896) * Folks from Dixie (1898) * The Strength of Gideon (1900) * In Old Plantation Days (1903) * The Heart of Happy Hollow (1904) * Lyrics of Sunshine and Shadow (1905) References Paul Laurence Dunbar Website - www.dunbarsite.org/biopld.asp Wikipedia- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Laurence_Dunbar

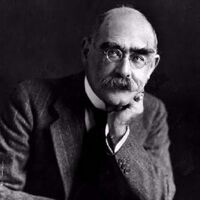

Joseph Rudyard Kipling (30 December 1865 – 18 January 1936) was an English novelist, short-story writer, poet, and journalist. He was born in British India, which inspired much of his work. Kipling was one of the most popular writers in England, in both prose and verse, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Henry James said: “Kipling strikes me personally as the most complete man of genius (as distinct from fine intelligence) that I have ever known.”

Gloria Fuertes (Madrid, 28 de julio de 1917 – Madrid, 27 de noviembre de 1998) fue una poetisa española. Nació en Lavapiés, en la época, un modesto barrio del Madrid antiguo. Su madre era costurera y sirvienta; su padre, bedel. Poco se sabe de su vida familiar, a lo que ha contribuido que la escritora siempre guardara celosamente su intimidad. Se ha especulado sobre su homosexualidad, que aparecería sutilmente declarada en poemas como «Lo que me enerva», «Me siento abierta a todo», «A Jenny», etc. Dice Gloria Fuertes: Sale caro, señores, ser poeta. La gente va y se acuesta tan tranquila que después del trabajo da buen sueño−. Trabajo como esclavo llego a casa, me siento ante la mesa sin cocina, me pongo a meditar lo que sucede. La duda me acribilla todo espanta; comienzo a ser comida por las sombras las horas se me pasan sin bostezo el dormir se me asusta se me huye −escribiendo me da la madrugada−. Y luego los amigos me organizan recitales, a los que acudo y leo como tonta, y la gente no sabe de esto nada. Que me dejo la linfa en lo que escribo, me caigo de la rama de la rima asalto las trincheras de la angustia que nombran su héroe los fantasmas, me cuesta respirar cuando termino. Sale caro señores ser poeta.

Worked in Manufacturing for 45 years. I am now a retired Tool&Die Maker. I am married with two grown children. I write poems, short stories, and some children's stories. I have published Poems in Quarterlies across the US in the 1980's, some awards and honorable mentions. My stories and some poems are now published on Booksie.com --- Author names = D. Thurmond --- & --- JE Falcon.

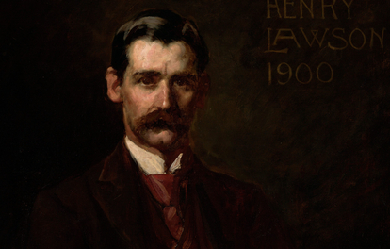

Henry Archibald Hertzberg Lawson (17 June 1867 – 2 September 1922) was an Australian writer and poet. Along with his contemporary Banjo Paterson, Lawson is among the best-known Australian poets and fiction writers of the colonial period and is often called Australia's “greatest short story writer”. He was the son of the poet, publisher and feminist Louisa Lawson.

Carl Sandburg was born in Galesburg, Illinois, on January 6, 1878. His parents, August and Clara Johnson, had emigrated to America from the north of Sweden. After encountering several August Johnsons in his job for the railroad, the Sandburg's father renamed the family. The Sandburgs were very poor; Carl left school at the age of thirteen to work odd jobs, from laying bricks to dishwashing, to help support his family. At seventeen, he traveled west to Kansas as a hobo. He then served eight months in Puerto Rico during the Spanish-American war. While serving, Sandburg met a student at Lombard College, the small school located in Sandburg's hometown. The young man convinced Sandburg to enroll in Lombard after his return from the war.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning (6 March 1806 – 29 June 1861) was one of the most prominent poets of the Victorian era. Her poetry was widely popular in both England and the United States during her lifetime. A collection of her last poems was published by her husband, Robert Browning, shortly after her death. Barrett Browning opposed slavery and published two poems highlighting the barbarity of slavers and her support for the abolitionist cause. The poems opposing slavery include "The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim's Point" and "A Curse for a Nation"; in the first she describes the experience of a slave woman who is whipped, raped, and made pregnant as she curses the slavers. She declared herself glad that the slaves were "virtually free" when the Emancipation Act abolishing slavery in British colonies was passed in 1833, despite the fact that her father believed that Abolitionism would ruin his business.

There are much better writers than I Who have written of love, God and philosophy Not much that I can add But my unique life experiences I will stick to what I know and feel In hopes my written word can reach places that I have not Relying more on natural simplicity than technique and form Check out my work at: www.amazon.com/Laura-Alaniz

Juana Fernández Morales, cuyo seudónimo era Juana de Ibarbourou, conocida popularmente como Juana de América, (8 de marzo de 1892, Melo - 15 de julio de 1979, Montevideo), fue una poetisa uruguaya. El 10 de agosto de 1929 recibió, en el Salón de los Pasos Perdidos del Palacio Legislativo, el título de «Juana de América» de la mano de Juan Zorrilla de San Martín y una multitud de poetas y personalidades. Fue enterrada con honores de Ministro de Estado en el panteón de su familia del Cementerio del Buceo.

Wystan Hugh Auden (21 February 1907 – 29 September 1973), who published as W. H. Auden, was an Anglo-American poet, born in England, later an American citizen, regarded by many as one of the greatest writers of the 20th century. His work is noted for its stylistic and technical achievements, its engagement with moral and political issues, and its variety of tone, form and content. The central themes of his poetry are love, politics and citizenship, religion and morals, and the relationship between unique human beings and the anonymous, impersonal world of nature. Auden grew up in Birmingham in a professional middle class family and read English literature at Christ Church, Oxford. His early poems, written in the late 1920s and early 1930s, alternated between telegraphic modern styles and fluent traditional ones, were written in an intense and dramatic tone, and established his reputation as a left-wing political poet and prophet. He became uncomfortable in this role in the later 1930s, and abandoned it after he moved to the United States in 1939, where he became an American citizen in 1946. His poems in the 1940s explored religious and ethical themes in a less dramatic manner than his earlier works, but still combined traditional forms and styles with new forms devised by Auden himself. In the 1950s and 1960s many of his poems focused on the ways in which words revealed and concealed emotions, and he took a particular interest in writing opera librettos, a form ideally suited to direct expression of strong feelings.

I am very passionate about writing especially poetry because it speaks to my soul. I'm looking forward to become a professional writer someday and get published. I want to share my writing talent worldwide and I won't stop until I do. While I'm here at "Poeticous". I would like to receive honest feedback on my writings, but I can see people don't really comment, they only view. So what's the point of Poet's like myself sharing our poetry? if no one is willing to comment. Also, they may like the poem but refuse to press the "like" button..........I just don't understand that!!!

Flora Alejandra Pizarnik (Avellaneda, 29 de abril de 1936 – Buenos Aires, 25 de septiembre de 1972) fue una poetisa, ensayista y traductora argentina. Estudió filosofía y Letras en la Universidad de Buenos Aires y pintura con Juan Batlle Planas. Entre 1960 y 1964, Pizarnik vivió en París, donde trabajó para la revista Cuadernos y algunas editoriales francesas, publicó poemas y críticas en varios diarios y tradujo a Antonin Artaud, Henri Michaux, Aimé Césaire e Yves Bonnefoy. Además, estudió historia de la religión y literatura francesa en La Sorbona. Tras su retorno a Buenos Aires, Pizarnik publicó tres de sus principales volúmenes: Los trabajos y las noches, Extracción de la piedra de locura y El infierno musical, así como su trabajo en prosa La condesa sangrienta.

Hello. My name is Mike. I'm a 30something turning 102 this year. I'm the father to an amazing little girl who I'm unable to see as much as I would like, because I was unable to save her from a lifetime of pain. On this page you'll hear me drone on about topics such as this, being a victim of partners and parents with personality disorders, OCD, PTSD, suicidal ideation, and the occasional nonsensical poem about a snail or a garden gnome. There are horrible people in the world, and many of them are inescapable, and most of you would not believe the chaotic hell my life has led me through. But I have always tried to be the sort of person who I wish others would be. It's so much harder to be a bad person than a good person. Given the issues in my life, I might suffer hazards that would prevent me from furthering this message, so let me attempt to do so here. Be a good person. Know that nothing you do will ever change the world, and that all the help you give to others will ultimately be pointless. But that shouldn't stop you from trying to be the best person you can be. Live as altruistically and conscientiously towards others as possible. Hold open doors, be humble, apologize, offer help. If you see someone in need, don't wait for someone else to come along, because they might not. If you see a need, fill a need. Treat others with kindness and fairness, empathy and equity. If you hurt someone, find out how you can prevent yourself from doing so again in the future. Let people in when you're driving, spare some change to panhandlers, defend kids and animals when you see they're in trouble. The meaning of life is progress. Without growth, there can only be decay. It's too late for humanity as a species, but if everyone reading this could just try a little harder, maybe life wouldn't have to be so unfair. I want to take the time to thank those who follow me directly, as well as those who view my poems in passing. It does not go undetected or unappreciated, truly. Thank you for your support. I hope you all find whatever you’re looking for.

William Shakespeare (baptised 26 April 1564; died 23 April 1616) was an English poet and playwright, widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's national poet and the "Bard of Avon". His surviving works, including some collaborations, consist of about 38 plays, 154 sonnets, two long narrative poems, and several other poems. His plays have been translated into every major living language and are performed more often than those of any other playwright. Authorship Around 230 years after Shakespeare’s death, doubts began to be expressed about the authorship of the works attributed to him. Proposed alternative candidates include Francis Bacon, Christopher Marlowe, and Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford. Several “group theories” have also been proposed. All but a few Shakespeare scholars and literary historians consider it a fringe theory, with only a small minority of academics who believe that there is reason to question the traditional attribution, but interest in the subject, particularly the Oxfordian theory of Shakespeare authorship, continues into the 21st century.

Reinaldo Bustillo Cuevas nació en San Juan Nepomuceno, Colombia, hijo del poeta Ismael Bustillo Angulo y Doña Elena Cuevas Arrieta, hija a su vez del Medico Honoris Causa Don Manuel Cuevas Martínez. Fue profesor de Matemática y Literatura en La Normal Superior para Señoritas Mercedes Elena de Pareja; en la Concentración de Educación Media Diógenes Arrieta; y en el Colegio de Bachillerato Silvia S de Arrieta donde fungió de rector. Fue elegido Diputado a la Asamblea de Bolívar por el partido Nuevo Liberalismo, comandado a nivel nacional por el mártir Luis Carlos Galán Sarmiento. Ha publicado tres poemarios: “Te Espero en la Orilla del Recuerdo”; “Migajas de Amor” y “El Cielo de mi Tierra es Diferente”; un ensayo: “Diógenes Arrieta, Guerrero de la Pluma y la Palabra”; es autor de numerosos poemas, cuentos y ensayos, publicados en Revistas Nacionales y Extranjeras; colaborador del diario “La Libertad de Barranquilla”; de “El Espectador” de Bogotá”; Letra Digital” del Uruguay; Symbolos de México D.F; “Comparto mi Cultura” de Argentina; ha sido traducido al portugués por Urda Alice Klueger; referenciado por Jaime González Sánchez catedrático de la Universidad Santa Cruz de la Sierra de Bolivia por el Trabajo “Moral Antropológica“; lector invitado varias veces por la Radio La Quebrada de Argentina en el “Programa Una Noche Inolvidable”; Mención Especial de SADE (Sociedad Argentina de Escritores), con el soneto Mi Terruño, dedicado a San Juan Nepomuceno, en el Concurso Internacional del Soneto en Dolores; Miembro del Club Internacional de Escritores “Palabra sobre palabra” de España, donde fue Creador del “ Grupo Amantes del Soneto”, adscrito al Grupo PsP y designado como profesor de CEL ( Centro de Estudios Literarios). Obtuvo el primer lugar en el Concurso Internacional de “Un Soneto Para Soria- España”, convocado por “Amistad Numancia” con el propósito de exaltar los méritos heroicos de Numancia, ciudad celtibera, que no pudo ser tomada por las armas del Imperio Romano en el sitio que le infligió en el 133 antes de Cristo , sino que únicamente por un asedio de dieciocho meses se doblegó ante seiscientos mil legionarios, bajo el mando del nieto del Escipión el Africano, Publio Cornelio Escipion Emiliano. Aceptado como Miembro de SELAE (Sociedad de Escritores Latinoamericanos y europeos) con sede en Milán- Italia y de donde es colaborador; y Embajador ante los Escritores Colombianos. Últimamente fue aceptado como colaborados del Blog Corazón del verbo de Sevilla- España, donde publico el soneto “El COLIBRÍ” Y DE LA Revista ALDABA de Sevilla- España. EL CIELO DE MI TIERRA ES DIFERENTE Por Jocé Daniels García El Cielo de mi tierra es diferente es uno de los buenos libros de poesía que en los últimos tiempos ha caído, por voluntad de las musas, en mis manos, y como todos los libros de Reinaldo Bustillo Cuevas lleva el estigma indeleble de quien a través de los años conoce las leyes de la poesía clásica y sabe cuál es la música, el tono y la melancolía que debe llevar un verso libre. Desde los primeros poemas fluye ese remolino lírico y entonces observamos que detrás de bambalinas, las metáforas ocultan un código referido a San Juan Nepomuceno. Demuestra como todo buen aeda que cuando quiere algo lo imagina, lo crea y lo eterniza con su pluma, donde lentamente aparece el ingenio y la imaginación, la gracia y la fantasía, la sutileza y el conocimiento de la naturaleza humana, como un hijo de aquellos campos florecidos, como un hijo del espíritu errante de Trino el brujo el cantor de los Montes de María. El Soneto como la máxima expresión del género poético, desarrollado por los poetas castellanos desde Félix Lope de Vega Carpio hasta el caballero del Soneto, don Miguel Rasch Isla, y que en nuestro país ha tenido tantos seguidores, también tiene un espacio en la poética de Bustillo Cuevas. Son Sonetos de Mentira en donde surge una poesía límpida que consolida su estilo personal y como las flautas al viento que cantan el preludio al trinar de los pájaros, Bustillo Cuevas, con sus marcadas influencias piedracielistas, modernistas y románticos pergeña una poesía que se gesta en una realidad vivida, con nombres propios y compromete el paisaje del San Juan de sus recuerdos, su entorno humano y lo viste con las mejores galas de la belleza natural. Conocí a Bustillo Cuevas en las mismas circunstancias en que se conocen todos los poetas de este mundo, una tarde de otoño cuando nos disponíamos a develar los secretos enterrados en una de las criptas del viejo mausoleo donde se decía estaban los versos más bellos de Diógenes Arrieta y que había escrito en tiempos en que las doncellas que buscaban destino con sus multicolores miriñaques coqueteaban muy cerca de donde estaban los otrora empresarios del tabaco. Desde aquellas lluvias hasta nuestros días me he deleitado con sus poesías, bellas tristes, alegres y frescas, libres de estridencias y ambages retóricos, cuyos antecedentes se encuentran sumergidos en otros grandes poetas de San Juan Nepomuceno. Sus versos contrastan con la poesía frívola, cursi y floja de algunos poetas de nuestro tiempo que en medio de la manigua de una ciudad tan anquilosada en material cultural como Cartagena surgen como una gran cártel con sus turiferarios y corifeos para conformar una sociedad de elogios mutuos y así endilgarse epítetos sonoros y coronarse de laurel y presentarse en el panorama intelectual como la pléyade de los elegidos. Organizan concursos y eventos y como en la corrompida Roma de Nerón tocan la lira del triunfo, se ríen de sus propias pilatunas, y al igual que los zoilos de la desgracia, bautizan y excomulgan, pontifican con sus poesías tan débiles que se desgranan en el cernidor de la crítica para quedar regados en el solar de los infortunios. He ahí la diferencia. Bustillo Cuevas con sus versos libres ruge y avasalla, sin facilismo o ilusorios, sin la veleidad cotidiana que ha invadido los fértiles campos de la poesía. En El Cielo de mi tierra es Diferente nos topamos con versos acrisolados que se riegan en el ambiente como un ramillete multicolor y dejan efluvios agradables al espíritu. Gracias a Dios y a Trino el Brujo, aún quedan buenos aedas. Benéfica influencia del soneto en la poesía Libre Artes, Artes literarias, Poesía Rafael Núñez Moledo, poeta autor del Himno Nacional de Colombia y Presidente de le Republica, alguna vez dijo: El cerebro mana el pensamiento como la caña miel. Sin justificar la verdad científica de esta expresión quiero tomar el fundamento metafórico del mensaje para colegir con él, que cada vez que el hombre se expresa, lo hace en armonía con lo que abunda en su cerebro; y que, por lo tanto, el poeta cuando habla hace poesía. Le oí decir a alguien, en alguna ocasión, que poesía es el modo natural de expresarse el vate. Todo lo anterior para decir que la Poesía Libre, como su mismo nombre indica, es poesía; y afirmar, sin el más mínimo temor de desacertar, que en esta forma de poesía se han escrito piezas trascendentales de la Poesía Universal. Pero pido licencia para hacer algunas elucubraciones, de las que respondo sin comprometer a ninguna Escuela y menos a algún autor, sobre lo que considero justificó, en parte, la poesía Libre. Séame así mismo permitido hacer uso de un símil para encontrar el sendero expedito que me conduzca a demostrar la hipótesis que pretendo exponerles. Imaginemos a un malabarista, que cansado de aumentar el número de objetos que lanza, al aire, describiendo un arco, para recibirlos con la otra mano, resuelve tomar objetos de diferentes pesos, ya sea por su tamaño o por el peso específico de los materiales de que hace uso. El público que observa, se siente incapaz de distinguir a simple vista el peso relativo de cada uno de los objetos que forman el arco armonioso del artista. Así el poeta que cansado del isosilabismo resuelve versificar con versos anisosilábicos, no olvida nunca el ritmo, que es en esencia un retomar el concepto griego del uso de los pies, concepto este merecedor de suma atención, para comprender la musicalidad de cada idioma. Decimos, pues, que la poesía versolibrista, consistió en sus orígenes, en el abandono del isosilabismo, pero cada vez que hizo uso de un verso de determinado número de sílabas, su autor se sintió comprometido a cumplir con el ritmo propio de él, no es pues prosa escrita en renglones cortos; recordemos que el verso es un renglón con medida; la libertad a la que alude el término no debe entenderse como despreocupación de la musicalidad, que es condición constitutiva del verso. Es célebre la advertencia, en este sentido, de Machado: Verso libre, verso libre, líbrate mejor del verso cuando te esclavice. Resumiendo diremos que el versolibrismo emplea el verso anisosilábico, pero que cada vez que hace uso de uno cualquiera, está en la obligación de respetar y acatar su ritmo, distribución de acentos, de la manera como la naturaleza del verso en particular requiera. Aquí es donde viene la influencia benéfica del Soneto en la Poesía Libre, en cuanto que estando el soneto sometido a una estricta distribución de acentos, enseña al poeta versolibrista a cumplir este requisito que enriquecerá y hermoseará su verso. Podemos decir, sin el mínimo riesgo de error, que el experto en escribir sonetos tendrá la habilidad de escribir versos libres más rítmicos Por otro lado los poetas que escriben versolibrismo no deben olvidar que la exoneración que se les brinda en cuanto a la rima y al número de sílabas no llega nunca, no puede llegar, a liberarlo del ritmo, pues su producción dejaría de ser verso y se convertiría en prosa; prosa poética si se quiere, pero prosa. El poema Libre, para que quede cabal, exige cadencia, ritmo interno y musicalidad, atributos que vienen dados en formas diferentes que en el soneto , o en general, en la poesía isosilábica. En todo caso el verso libre no es prosa en renglones cortos, es una forma diferente de poetizar, pero que, aunque parezca contradictorio, tiene sus leyes. © Reinaldo Bustillo Cuevas Reinaldo Bustillo Cuevas, después de terminar sus estudios elementales en su pueblo natal, San Juan Nepomuceno, en la Escuela Pública para Varones, entidad única educacional existente en la localidad, para ese entonces, regentada por Don Roque Jacinto Borré Paz, viajó a Cartagena de Indias para asistir a una convocatoria que el Gobierno Central hacía a los estudiantes que aspiraran cursar estudios de Bachillerato. Allí conoció el mar: inmensidad azul, que a las seis de la tarde se salía de su lecho para besarle los pies al sorprendido joven que, sentado en un tronco viejo, no ha podido nunca desgravarlo de su mente y sus amores. Ganó una Beca para el Colegio Nacional Simón Araujo, en Sincelejo actual capital del Departamento de Sucre, pero en esas calendas la segunda ciudad en importancia en el Departamento de Bolívar, donde queda San Juan Nepomuceno. Recién llegado compite en una convocatoria para “El Cuento del Araujo”, con la gratísima sorpresa de salir triunfador con su trabajo “El Beso Amargo”. Para profesores y amigos era sorprendente que un joven con inclinaciones poéticas se destacara además como el mejor estudiante en matemática. Desde entonces estas dos tendencias lo irán marcando para el resto de su vida. Como matemático se destacó, casi de inmediato, como orientador de sus mismos condiscípulos. En el segundo año de Bachillerato por la falta temporal del profesor de matemática y siendo encargado un profesor desconocedor de la materia, se encarga del desarrollo del programa escolar en la materia, bajo el control disciplinario del docente encargado de la asignatura. Durante el resto del bachillerato fue profesor de matemática de sus compañeros e inclusive en algunas ocasiones orientador de alumnos de cursos superiores. Pero su oculta afición hacía la poesía seguía en ascenso, hasta llegar a escribir su primer soneto: Azul. Terminados sus estudios secundarios se traslada a Bogotá a estudiar Ingeniera Civil, pero descuida sus estudios superiores por dedicar la mayor parte de su tiempo a desempeñarse como profesor de literatura, actividad que constituía su principal fuente de ingresos, entonces conoce a una niña que le recuerda, con sus ojos su lejano mar y con su andar a las gacelas de su San juan distante y le dedica el soneto Levedad La fragancia de amor de su sonrisa riega su esplendidez en la mañana, cuando devota llama la campana al santo sacrificio de la misa. Con garbo de gacela, anda de prisa, como emergiendo de una luz temprana que le cede al andar gracia liviana en alígeros pliegues de la brisa. Va pintando de azul con su mirada el tapete de armiño de la nieve, que el frío mañanero patrocina, si burila en el prado su pisada con gracia femenil que, el rastro leve, va inventando el sendero en que camina. Sin concluir sus estudios profesionales regresa a su ciudad natal en calidad de profesor de matemática y de literatura en la Normal Superior “Diógenes Arrieta” y en la “Concentración de Educación Media Departamental, recién establecidas y funda el “Colegio de Bachillerato Silvia S. de Arrieta” donde dictó las asignaturas de literatura y matemática y fungió de rector. Por circunstancia, inesperadas y sorprendentes de la vida, pues nunca había ejercido la actividad política, llega bajo el patrocinio del Líder y posteriormente mártir de la Patria: Luis Carlos Galán Sarmiento a la Asamblea Departamental de Bolívar. No ha dejado nunca de desempeñarse como orientador de las juventudes de la región como guía en literatura. Fue columnista del “Espectador Costa” de Bogotá, y del diario “La Libertad” de Barranquilla durante largo tiempo; y se ha desempeñado como conferenciante en eventos literarios, como presidente fundador de la Casa de la Cultura de San Juan Nepomuceno, y como miembro del “Fondo Mixto para la Cultura del departamento de Bolívar”.