Info

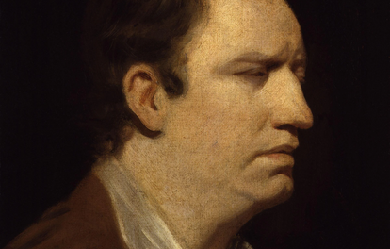

Girl Bundling Asparagus

John Atkinson

1771

Yale Center for British Art

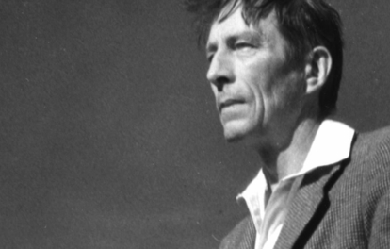

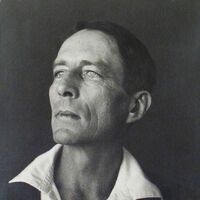

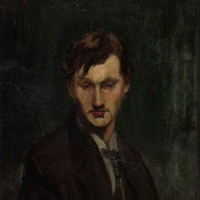

John Robinson Jeffers (January 10, 1887 – January 20, 1962) was an American poet, known for his work about the central California coast. Much of Jeffers' poetry was written in narrative and epic form, but he is also known for his shorter verse and is considered an icon of the environmental movement. Influential and highly regarded in some circles, despite or because of his philosophy of "inhumanism," Jeffers believed that transcending conflict required human concerns to be de-emphasized in favor of the boundless whole. This led him to oppose U.S. participation in World War II, a stand that was controversial at the time. Jeffers was born in Allegheny, Pennsylvania (now part of Pittsburgh), the son of a Presbyterian minister and biblical scholar, Reverend Dr. William Hamilton Jeffers, and Annie Robinson Tuttle. His brother was Hamilton Jeffers, who became a well-known astronomer, working at Lick Observatory. His family was supportive of his interest in poetry. He traveled through Europe during his youth and attended school in Switzerland. He was a child prodigy, interested in classics and Greek and Latin language and literature. At sixteen he entered Occidental College. At school, he was an avid outdoorsman, and active in the school's literary societies. After he graduated from Occidental, Jeffers went to the University of Southern California to study at first literature, and then medicine. He met Una Call Kuster in 1906; she was three years older than he was, a graduate student, and the wife of a Los Angeles attorney. In 1910 he enrolled as a forestry student at the University of Washington in Seattle, a course of study that he abandoned after less than one year, at which time he returned to Los Angeles. Sometime before this, he and Una had begun an affair that became a scandal, reaching the front page of the Los Angeles Times in 1912. After Una spent some time in Europe to quiet things down, the two were married in 1913, and moved to Carmel, California, where Jeffers constructed Tor House and Hawk Tower. The couple had a daughter who died a day after birth in 1914, and then twin sons (Donnan and Garth) in 1916. Una died of cancer in 1950. Jeffers died in 1962; an obituary can be found in the New York Times, January 22, 1962. Poetic career In the 1920s and 1930s, at the height of his popularity, Jeffers was famous for being a tough outdoorsman, living in relative solitude and writing of the difficulty and beauty of the wild. He spent most of his life in Carmel, California, in a granite house that he had built himself called "Tor House and Hawk Tower". Tor is a term for a craggy outcrop or lookout. Before Jeffers and Una purchased the land where Tor House would be built, they rented two cottages in Carmel, and enjoyed many afternoon walks and picnics at the "tors" near the site that would become Tor House. To build the first part of Tor House, a small, two story cottage, Jeffers hired a local builder, Michael Murphy. He worked with Murphy, and in this short, informal apprenticeship, he learned the art of stonemasonry. He continued adding on to Tor House throughout his life, writing in the mornings and working on the house in the afternoon. Many of his poems reflect the influence of stone and building on his life. He later built a large four-story stone tower on the site called Hawk Tower. While he had not visited Ireland at this point in his life, it is possible that Hawk Tower is based on Francis Joseph Bigger's 'Castle Séan' at Ardglass, County Down, which had also in turn influenced Yeats' poets tower, Thoor Ballylee. Construction on Tor House continued into the late 1950s and early 1960s, and was completed by his eldest son. The completed residence was used as a family home until his descendants decided to turn it over to the Tor House Foundation, formed by Ansel Adams, for historic preservation. The romantic Gothic tower was named after a hawk that appeared while Jeffers was working on the structure, and which disappeared the day it was completed. The tower was a gift for his wife Una, who had a fascination for Irish literature and stone towers. In Una's special room on the second floor were kept many of her favorite items, photographs of Jeffers taken by the artist Weston, plants and dried flowers from Shelley's grave, and a rosewood melodeon which she loved to play. The tower also included a secret interior staircase – a source of great fun for his young sons. During this time, Jeffers published volumes of long narrative blank verse that shook up the national literary scene. These poems, including Tamar and Roan Stallion, introduced Jeffers as a master of the epic form, reminiscent of ancient Greek poets. These poems were full of controversial subject matter such as incest, murder and parricide. Jeffers' short verse includes "Hurt Hawks," "The Purse-Seine" and "Shine, Perishing Republic." His intense relationship with the physical world is described in often brutal and apocalyptic verse, and demonstrates a preference for the natural world over what he sees as the negative influence of civilization. Jeffers did not accept the idea that meter is a fundamental part of poetry, and, like Marianne Moore, claimed his verse was not composed in meter, but "rolling stresses." He believed meter was imposed on poetry by man and not a fundamental part of its nature. nitially, Tamar and Other Poems received no acclaim, but when East Coast reviewers discovered the work and began to compare Jeffers to Greek tragedians, Boni & Liveright reissued an expanded edition as Roan Stallion, Tamar and Other Poems (1925). In these works, Jeffers began to articulate themes that contributed to what he later identified as Inhumanism. Mankind was too self-centered, he complained, and too indifferent to the "astonishing beauty of things." Jeffers's longest and most ambitious narrative, The Women at Point Sur (1927), startled many of his readers, heavily loaded as it was with Nietzschean philosophy. The balance of the 1920s and the early 1930s were especially productive for Jeffers, and his reputation was secure. In 1934, he made the acquaintance of the philosopher J Krishnamurti and was struck by the force of Krishnamurti's person. He wrote a poem entitled "Credo" which many feel refers to Krishnamurti. In Cawdor and Other Poems (1928), Dear Judas and Other Poems (1929), Descent to the Dead, Poems Written in Ireland and Great Britain (1931), Thurso's Landing (1932), and Give Your Heart to the Hawks (1933), Jeffers continued to explore the questions of how human beings could find their proper relationship (free of human egocentrism) with the divinity of the beauty of things. These poems, set in the Big Sur region (except Dear Judas and Descent to the Dead), enabled Jeffers to pursue his belief that the natural splendor of the area demanded tragedy: the greater the beauty, the greater the demand. As Euripides had, Jeffers began to focus more on his own characters' psychologies and on social realities than on the mythic. The human dilemmas of Phaedra, Hippolytus, and Medea fascinated him. Many books followed Jeffers' initial success with the epic form, including an adaptation of Euripides' Medea, which became a hit Broadway play starring Dame Judith Anderson. D. H. Lawrence, Edgar Lee Masters, Benjamin De Casseres, and George Sterling were close friends of Jeffers, Sterling having the longest and most intimate relationship with him. While living in Carmel, Jeffers became the focal point for a small but devoted group of admirers. At the peak of his fame, he was one of the few poets to be featured on the cover of Time Magazine. He was also asked to read at the Library of Congress, and was posthumously put on a U.S. postage stamp. Part of the decline of Jeffers' popularity was due to his staunch opposition to the United States' entering World War II. In fact, his book The Double Axe and Other Poems (1948), a volume of poems that was largely critical of U.S. policy, came with an extremely unconventional note from Random House that the views expressed by Jeffers were not those of the publishing company. Soon after, his work was received negatively by several influential literary critics. Several particularly scathing pieces were penned by Yvor Winters, as well as by Kenneth Rexroth, who had been very positive in his earlier commentary on Jeffers' work. Jeffers would publish poetry intermittently during the 1950s but his poetry never again attained the same degree of popularity that it had in the 1920s and the 1930s. Inhumanism Jeffers coined the word inhumanism, the belief that mankind is too self-centered and too indifferent to the "astonishing beauty of things." In the famous poem "Carmel Point," Jeffers called on humans to "uncenter" themselves. In "The Double Axe," Jeffers explicitly described inhumanism as "a shifting of emphasis and significance from man to notman; the rejection of human solipsism and recognition of the trans-human magnificence. ... This manner of thought and feeling is neither misanthropic nor pessimist. ... It offers a reasonable detachment as rule of conduct, instead of love, hate and envy ... it provides magnificence for the religious instinct, and satisfies our need to admire greatness and rejoice in beauty." In The Loyalties of Robinson Jeffers,the first in-depth study of Jeffers not written by one of his circle, poet and critic J. Radcliffe Squires addresses the question of a reconciliation of the beauty of the world and potential beauty in mankind: “Jeffers has asked us to look squarely at the universe. He has told us that materialism has its message, its relevance, and its solace. These are different from the message, relevance, and solace of humanism. Humanism teaches us best why we suffer, but materialism teaches us how to suffer.” Influence His poems have been translated into many languages and published all over the world. Outside of the United States he is most popular in Japan and the Czech Republic. William Everson, Edward Abbey, Gary Snyder, and Mark Jarman are just a few recent authors who have been influenced by Jeffers. Charles Bukowski remarked that Jeffers was his favorite poet. Polish poet Czesław Miłosz also took an interest in Jeffers' poetry and worked as a translator for several volumes of his poems. Jeffers also exchanged some letters with his Czech translator and popularizer, the poet Kamil Bednář. Writer Paul Mooney (1904–1939), son of American Indian authority James Mooney (1861–1921) and collaborator of travel writer Richard Halliburton (1900–1939), "was known always to carry with him (a volume of Jeffers) as a chewer might carry a pouch of tobacco ... and, like Jeffers," writes Gerry Max in Horizon Chasers, "worshipped nature ... (taking) refuge (from the encroachments of civilization) in a sort of chthonian mysticism rife with Greek dramatic elements ..." Jeffers was an inspiration and friend to western U.S. photographers of the early twentieth century, including Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, and Morley Baer. In fact, the elegant book of Baer's photographs juxtaposed with Jeffers' poetry, combines the creative talents of those two residents of the Big Sur coast. Although Jeffers has largely been marginalized in the mainstream academic community over the last thirty years, several important contemporary literary critics, including Albert Gelpi of Stanford University, and poet, critic and NEA chairman Dana Gioia, have consistently cited Jeffers as a formidable presence in modern literature. His poem "The Beaks of Eagles" was made into a song by The Beach Boys on their album Holland (1973). Two lines from Jeffers' poem "We Are Those People" are quoted toward the end of the 2008 film Visioneers. Several lines from Jeffers' poem "Wise Men in Their Bad Hours" ("Death's a fierce meadowlark: but to die having made / Something more equal to the centuries / Than muscle and bone, is mostly to shed weakness.") appear in Christopher McCandless' diary. Robinson Jeffers is mentioned in the 2004 film I Heart Huckabees by the character Albert Markovski played by Jason Schwartzman, when defending Jeffers as a nature writer against another character's claim that environmentalism is socialism. Markovski says, "Henry David Thoreau, Robinson Jeffers, the National Geographic Society...all socialists?" Further reading and research The largest collections of Jeffers' manuscripts and materials are in the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin and in the libraries at Occidental College, the University of California, and Yale University. A collection of his letters has been published as The Selected Letters of Robinson Jeffers, 1887–1962 (1968). Other books of criticism and poetry by Jeffers are: Poetry, Gongorism and a Thousand Years (1949), Themes in My Poems (1956), Robinson Jeffers: Selected Poems (1965), The Alpine Christ and Other Poems (1974), What Odd Expedients" and Other Poems (1981), and Rock and Hawk: A Selection of Shorter Poems by Robinson Jeffers (1987). Stanford University Press recently released a five-volume collection of the complete works of Robinson Jeffers. In an article titled, "A Black Sheep Joins the Fold", written upon the release of the collection in 2001, Stanford Magazine commented that it was remarkable that, due to a number of circumstances, "there was never an authoritative, scholarly edition of California’s premier bard" until the complete works published by Stanford. Biographical studies include George Sterling, Robinson Jeffers: The Man and the Artist (1926); Louis Adamic, Robinson Jeffers (1929); Melba Bennett, Robinson Jeffers and the Sea (1936) and The Stone Mason of Tor House (1966); Radcliffe Squires, The Loyalties of Robinson Jeffers (1956); Edith Greenan, Of Una Jeffers (1939); Mabel Dodge Luhan, Una and Robin (1976; written in 1933); Ward Ritchie, Jeffers: Some Recollections of Robinson Jeffers (1977); and James Karman, Robinson Jeffers: Poet of California (1987). Books about Jeffers's career include L. C. Powell, Robinson Jeffers: The Man and His Work (1940; repr. 1973); William Everson, Robinson Jeffers: Fragments of an Older Fury (1968); Arthur B. Coffin, Robinson Jeffers: Poet of Inhumanism (1971); Bill Hotchkiss, Jeffers: The Sivaistic Vision (1975); James Karman, ed., Critical Essays on Robinson Jeffers (1990); Alex Vardamis The Critical Reputation of Robinson Jeffers (1972); and Robert Zaller, ed., Centennial Essays for Robinson Jeffers (1991). The Robinson Jeffers Newsletter, ed. Robert Brophy, is a valuable scholarly resource. In a rare recording, Jeffers can be heard reading his "The Day Is A Poem" (September 19, 1939) on Poetry Speaks – Hear Great Poets Read Their Work from Tennyson to Plath, Narrated by Charles Osgood (Sourcebooks, Inc., c2001), Disc 1, #41; including text, with Robert Hass on Robinson Jeffers, pp. 88–95. Jeffers was also on the cover of Time – The Weekly Magazine, April 4, 1932 (pictured on p. 90. Poetry Speaks). Jeffers Studies, a journal of research on the poetry of Robinson Jeffers and related topics, is published semi-annually by the Robinson Jeffers Association. Bibliography * Flagons and Apples. Los Angeles: Grafton, 1912. * Californians. New York: Macmillan, 1916. * Tamar and Other Poems. New York: Peter G. Boyle, 1924. * Roan Stallion, Tamar, and Other Poems. New York: Boni and Liveright, 1925. * The Women at Point Sur. New York: Liveright, 1927. * Cawdor and Other Poems. New York: Liveright, 1928. * Dear Judas and Other Poems. New York: Liveright, 1929. * Thurso's Landing and Other Poems. New York: Liveright, 1932. * Give Your Heart to the Hawks and other Poems. New York: Random House, 1933. * Solstice and Other Poems. New York: Random House, 1935. * Such Counsels You Gave To Me and Other Poems. New York: Random House, 1937. * The Selected Poetry of Robinson Jeffers. New York: Random House, 1938. * Be Angry at the Sun. New York: Random House, 1941. * Medea. New York: Random House, 1946. * The Double Axe and Other Poems. New York: Random House, 1948. * Hungerfield and Other Poems. New York: Random House, 1954. * The Beginning and the End and Other Poems. New York: Random House, 1963. * Robinson Jeffers: Selected Poems. New York: Vintage, 1965. * Stones of the Sur. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robinson_Jeffers

Ben Jonson (originally Benjamin Jonson; c. 11 June 1572 – 6 August 1637) was an English playwright, poet, and literary critic of the seventeenth century, whose artistry exerted a lasting impact upon English poetry and stage comedy. He popularised the comedy of humours. He is best known for the satirical plays Every Man in His Humour (1598), Volpone, or The Foxe (1605), The Alchemist (1610), and Bartholomew Fayre: A Comedy (1614), and for his lyric poetry; he is generally regarded as the second most important English dramatist, after William Shakespeare, during the reign of James I. He was a classically educated, well-read, and cultured man of the English Renaissance with an appetite for controversy (personal and political, artistic and intellectual) whose cultural influence was of unparalleled breadth upon the playwrights and the poets of the Jacobean era (1603–1625) and of the Caroline era (1625–1642).

I'm not scared of toasters, but it's ok if you are. Fearing things that can hurt you is natural. Unfortunately, I'm a sucker for huckleberry jam on toast, so I take that risk every day. I don't have forever, and life isn't always enjoyable, but have you TRIED huckleberry jam? It's hard to hate the world when you have that slightly chunky, gelatinous concentration on a piece of glutenous (or should I say gluttonous) bread.

Erica Jong (née Mann; born March 26, 1942) is an American novelist and poet, known particularly for her 1973 novel Fear of Flying. The book became famously controversial for its attitudes towards female sexuality and figured prominently in the development of second-wave feminism. According to Washington Post, it has sold more than 20 million copies worldwide. Born in New York, she was the second of three daughters of Seymore Mann and Eda Mirsky. Attended New York’s Public High School of Music and Art in the 1950’s where she developed her passion for art and writing. As a student at Barnard College, she edited the Barnard Literary Magazine and created poetry programs for the Columbia University campus radio station.

James Augustine Aloysius Joyce (2 February 1882 – 13 January 1941) was an Irish novelist and poet, considered to be one of the most influential writers in the modernist avant-garde of the early 20th century. Joyce is best known for Ulysses (1922), a landmark work in which the episodes of Homer's Odyssey are paralleled in an array of contrasting literary styles, perhaps most prominently the stream of consciousness technique he perfected. Other major works are the short-story collection Dubliners (1914), and the novels A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916) and Finnegans Wake (1939). His complete oeuvre includes three books of poetry, a play, occasional journalism, and his published letters.

I don't write to please Only to put this need at ease I can't force my poems, spontanious as fire They flow in when they desire Like emotions, they never seem to dim It's my job to scramble; keeping up with them So they are not a loss of time To view my work I won't charge one dime All my hardships are not my demise This life I live is such a prize

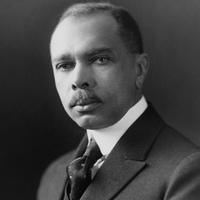

James Weldon Johnson (June 17, 1871– June 26, 1938) was an American author, educator, lawyer, diplomat, songwriter, and civil rights activist. Johnson is best remembered for his leadership of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), where he started working in 1917. In 1920 he was the first African American to be chosen as executive secretary of the organization, effectively the operating officer. He served in that position from 1920 to 1930. Johnson established his reputation as a writer, and was known during the Harlem Renaissance for his poems, novels, and anthologies collecting both poems and spirituals of black culture. He was appointed under President Theodore Roosevelt as US consul in Venezuela and Nicaragua for most of the period from 1906 to 1913. In 1934 he was the first African-American professor to be hired at New York University. Later in life he was a professor of creative literature and writing at Fisk University.

Helen Maria Hunt Jackson, born Helen Fiske (October 15, 1830 – August 12, 1885), was a United States writer who became an activist on behalf of improved treatment of Native Americans by the U.S. government. She detailed the adverse effects of government actions in her history A Century of Dishonor (1881). Her novel Ramona dramatized the federal government's mistreatment of Native Americans in Southern California and attracted considerable attention to her cause, although its popularity was based on its romantic and picturesque qualities rather than its political content. It was estimated to have been reprinted 300 times, and contributed to the growth of tourism in Southern California. Early years She was born Helen Fiske in Amherst, Massachusetts, the daughter of Nathan Welby Fiske and Deborah Waterman Vinal. She had two brothers, both of whom died after birth, and a sister Anne. Her father was a minister, author, and professor of Latin, Greek, and philosophy at Amherst College. Her mother died in 1844 when Helen was fourteen, and her father three years later. Her father provided for her education and arranged for an aunt to care for her. Fiske attended Ipswich Female Seminary and the Abbott Institute, a boarding school run by Reverend J.S.C. Abbott in New York City. She was a classmate of the poet Emily Dickinson, also from Amherst. The two corresponded for the rest of their lives, but few of their letters have survived. Marriage and family In 1852 at age 22, Fiske married U.S. Army Captain Edward Bissell Hunt. They had two sons, one of whom, Murray Hunt, died as an infant in 1854 of a brain disease. In 1863, her husband died in a military accident. Her second son, Rennie Hunt, died of diphtheria in 1865. About 1873-1874, Hunt met William Sharpless Jackson, a wealthy banker and railroad executive, while visiting at Colorado Springs, Colorado, at the resort of Seven Falls. They married in 1875 and she took the name Jackson, under which she was best known for her writings. She was a Unitarian. Career Helen Hunt began writing after the deaths of her family members. She published her early work anonymously, usually under the name "H.H." Ralph Waldo Emerson admired her poetry and used several of her poems in his public readings. He included five of them in his anthology Parnassus. She traveled widely. In the winter of 1873-1874 she was in Colorado Springs, Colorado, in search of a cure for tuberculosis. Here she met the man who would become her second husband. Over the next two years, she published three novels in the anonymous No Name Series, including Mercy Philbrick's Choice and Hetty's Strange History. In 1879 her interests turned to Native Americans after hearing a lecture in Boston by the Ponca Chief Standing Bear. He described the forcible removal of the Ponca from their Nebraska reservation and transfer to the Quapaw Reservation in Indian Territory, where they suffered from disease, climate and poor supplies. Upset about the mistreatment of Native Americans by government agents, Jackson became an activist. She started investigating and publicizing government misconduct, circulating petitions, raising money, and writing letters to the New York Times on behalf of the Ponca. A fiery and prolific writer, Jackson engaged in heated exchanges with federal officials over the injustices committed against American Indians. Among her special targets was U.S. Secretary of Interior Carl Schurz, whom she once called "the most adroit liar I ever knew." She exposed the government's violation of treaties with the American Indian tribes. She documented the corruption of US Indian agents, military officers, and settlers who encroached on and stole Indian lands. Jackson won the support of several newspaper editors who published her reports. Among her correspondents were editor William Hayes Ward of the New York Independent, Richard Watson Guilder of the Century Magazine, and publisher Whitelaw Reid of the New York Daily Tribune. Jackson also wrote a book, the first published under her own name, condemning state and federal Indian policy, and detailing the history of broken treaties. A Century of Dishonor (1881) called for significant reform in government policy toward Native Americans.[10] Jackson sent a copy to every member of Congress with a quote from Benjamin Franklin printed in red on the cover: "Look upon your hands: they are stained with the blood of your relations." The New York Times later wrote that she "soon made enemies at Washington by her often unmeasured attacks, and while on general lines she did some good, her case was weakened by her inability, in some cases, to substantiate the charges she had made; hence many who were at first sympathetic fell away." Jackson went to southern California for respite. Having been interested in the area's missions and the Mission Indians on an earlier visit, she began an in-depth study. While in Los Angeles, she met Don Antonio Coronel, former mayor of the city and a well-known authority on early Californio life in the area. He had served as inspector of missions for the Mexican government. Coronel told her about the plight of the Mission Indians after 1833. They were buffeted by the secularization policies of the Mexican government, as well as later U.S. policies, both of which led to their removal from mission lands. Under its original land grants, the Mexican government provided for resident Indians to continue to occupy such lands. After taking control of the territory in 1848, the U.S. generally disregarded such Mission Indian occupancy claims. In 1852, there were an estimated 15,000 Mission Indians in Southern California. By the time of Jackson's visit, they numbered fewer than 4,000. Coronel's account inspired Jackson to action. The U.S. Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Hiram Price, recommended her appointment as an Interior Department agent. Jackson's assignment was to visit the Mission Indians, ascertain the location and condition of various bands, and determine what lands, if any, should be purchased for their use. With the help of the US Indian agent Abbot Kinney, Jackson traveled throughout Southern California and documented conditions. At one point, she hired a law firm to protect the rights of a family of Saboba Indians facing dispossession from their land at the foot of the San Jacinto Mountains. In 1883, Jackson completed her 56-page report. It recommended extensive government relief for the Mission Indians, including the purchase of new lands for reservations and the establishment of more Indian schools. A bill embodying her recommendations passed the U.S. Senate but died in the House of Representatives. Jackson decided to write a novel to reach a wider audience. When she wrote Coronel asking for details about early California and any romantic incidents he could remember, she explained her purpose: "I am going to write a novel, in which will be set forth some Indian experiences in a way to move people's hearts. People will read a novel when they will not read serious books."[14] She was inspired by her friend Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852). "If I could write a story that would do for the Indian one-hundredth part what Uncle Tom's Cabin did for the Negro, I would be thankful the rest of my life," she wrote. Although Jackson started an outline in California, she began writing the novel in December 1883 in her New York hotel room, and completed it in about three months. Originally titled In The Name of the Law, she published it as Ramona (1884). It featured Ramona, an orphan girl who was half Indian and half Scots, raised in Spanish Californio society, and her Indian husband Alessandro, and their struggles for land of their own. The characters were based on people known by Jackson and incidents which she had encountered. The book achieved rapid success among a wide public and was popular for generations; it was estimated to have been reprinted 300 times. Its romantic story also contributed to the growth of tourism to Southern California. Encouraged by the popularity of her book, Jackson planned to write a children's story about Indian issues, but did not live to complete it. Her last letter was written to President Grover Cleveland and said: "From my death bed I send you message of heartfelt thanks for what you have already done for the Indians. I ask you to read my Century of Dishonor. I am dying happier for the belief I have that it is your hand that is destined to strike the first steady blow toward lifting this burden of infamy from our country and righting the wrongs of the Indian race." Jackson died of stomach cancer in 1885 in San Francisco, California. Her husband arranged for her burial on a one-acre plot on a high plateau overlooking Colorado Springs, Colorado. Her grave was later moved to Evergreen Cemetery in Colorado Springs. At the time of her death, her estate was valued at $12,642. She used her married names, Helen Hunt and Helen Jackson, but she is most often referred to as Helen Hunt Jackson. The New York Times referred to her as Helen Hunt Jackson in 1885, reporting on her final illness, and in 1886, reporting on visitors to her grave. The name was used during her lifetime by others, though she disliked the practice. "It is not proper to keep one's first married name, after a second marriage", she wrote to Moncure Conway. To Caroline Healey Dall, she admitted she was "positively waging war" against being called "Helen Hunt Jackson". Critical response and legacy Jackson's A Century of Dishonor remains in print, as does a collection of her poetry. A New York Times reviewer said of Ramona that "by one estimate, the book has been reprinted 300 times." One year after Jackson's death the North American Review called Ramona "unquestionably the best novel yet produced by an American woman" and named it, along with Uncle Tom's Cabin, one of two most ethical novels of the 19th century. Sixty years after its publication, 600,000 copies had been sold. There have been over 300 reissues to date and the book has never been out of print. The novel has been adapted for other media, including three films, stage, and television productions. Valery Sherer Mathes assessed the writer and her work: Ramona may not have been another Uncle Tom's Cabin, but it served, along with Jackson's writings on the Mission Indians of California, as a catalyst for other reformers ....Helen Hunt Jackson cared deeply for the Indians of California. She cared enough to undermine her health while devoting the last few years of her life to bettering their lives. Her enduring writings, therefore, provided a legacy to other reformers, who cherished her work enough to carry on her struggle and at least try to improve the lives of America's first inhabitants. Her friend Emily Dickinson once described her limitations: "she has the facts but not the phosphorescence." In a review of a film version, a journalist wrote about the novel, calling it "the long and lugubrious romance by Helen Hunt Jackson, over which America wept unnumbered gallons in the eighties and nineties," and complained of "the long, uneventful stretches of the novel."[26] In reviewing the history of her publisher, Houghton Mifflin, a 1970 reviewer noted that Jackson typified the house's success: "Middle aged, middle class, middlebrow." Jackson herself wrote, "My Century of Dishonor and Ramona are the only things I have done of which I am glad.... They will live, and... bear fruit." A portion of Jackson's Colorado home has been reconstructed in the Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum and furnished with her possessions.

I work hard and play hard. I am a dad and that is the most important attribute about my self. I have a strong belief in God and trust that he guides me. I also have a soft heart and writing helps getting out the pain i may feel or i may just simply be sharing things i have written in the past. I love to write I do not claim to be good at it, but i enjoy it so much. Writing is my reading. I do not like to read books so writing is my way of exercising my brain. Feel free to critique my writing if it helps me then i thank you, if it is just to banter me then keep it to your self.

Emily Pauline Johnson (also known in Mohawk as Tekahionwake –pronounced: dageh-eeon-wageh, literally: ‘double-life’) (10 March 1861– 7 March 1913), commonly known as E. Pauline Johnson or just Pauline Johnson, was a Canadian writer and performer popular in the late 19th century. Johnson was notable for her poems and performances that celebrated her Aboriginal heritage; her father was a hereditary Mohawk chief of mixed ancestry. She also drew from English influences, as her mother was an English immigrant. One such poem is the frequently anthologized “The Song My Paddle Sings”. Johnson’s poetry was published in Canada, the United States and Great Britain. Johnson was one of a generation of widely read writers who began to define a Canadian literature. While her literary reputation declined after her death, since the later 20th century, there has been renewed interest in her life and works. A complete collection of her known poetry was published in 2002. Life and work Early life and education Pauline Johnson was born at Chiefswood, the family home built by her father in 1856 on his 225-acre estate at the Six Nations reserve outside Brantford, Ontario. She was the youngest of four children of Emily Susanna Howells Johnson (1824–1898), a native of England, and George Henry Martin Johnson (1816–1884), a Mohawk hereditary clan chief. His mother was of partial Dutch descent and born into the Wolf clan. Her mother was a Dutch girl who became assimilated as Mohawk after being taken captive and adopted by a Wolf clan family. Howells had immigrated to the United States in 1832 as a young child with her father, stepmother and siblings. Although Emily and George Johnson’s marriage had been opposed by both their families, and they were concerned that their mixed-race family would not be socially accepted, they were acknowledged as a leading Canadian family (Gray 2002, p. 61). The Johnsons enjoyed a high standard of living, and their family and home were well known. Chiefswood was visited by such intellectual and political guests as the inventor Alexander Graham Bell, painter Homer Watson, noted anthropologist Horatio Hale, and Lady and Lord Dufferin, Governor General of Canada. Emily and George Johnson encouraged their four children to respect and learn about both the Mohawk and the English aspects of their heritage. Because the children were born to a Native father, by British law they were legally considered Mohawk and wards of the British Crown. But under the Mohawk kinship system, because their mother was not Mohawk they were not born into a tribal clan; they were excluded from important aspects of the tribe’s matrilineal culture. Their paternal grandfather John Smoke Johnson, who had been elected an honorary Pine Tree Chief, was an authority in the lives of his grandchildren. He told them many stories in the Mohawk language, which they comprehended but did not speak fluently. Pauline Johnson said that she inherited her talent for elocution from her grandfather. Late in life, she expressed regret for not learning more of his Mohawk heritage. A sickly child, Johnson did not attend Brantford’s Mohawk Institute. It was established in 1834 as one of Canada’s first residential schools for Native children. Her education was mostly at home and informal, derived from her mother, a series of non-Native governesses, a few years at the small school on the reserve, and self-directed reading in the family’s expansive library. She became familiar with literary works by Byron, Tennyson, Keats, Browning, and Milton. She enjoyed reading tales about Native peoples, such as Longfellow’s epic poem The Song of Hiawatha and John Richardson’s Wacousta. At the age 14, Johnson went to Brantford Central Collegiate with her brother Allen, and she graduated in 1877. A schoolmate was Sara Jeannette Duncan, who developed her own journalistic and literary career. Literary and stage career During the 1880s, Pauline Johnson wrote and performed in amateur theatre productions. She enjoyed the Canadian outdoors, where she traveled by canoe. In 1883 she published her first full-length poem, “My Little Jean,” in the New York Gems of Poetry. She began to increase the pace of her writing and publishing afterward. Shortly after her father’s death in 1884, the family rented out Chiefswood. Pauline Johnson moved with her widowed mother and sister to a modest home in Brantford. She worked to support them all, and found that her stage performances allowed her to make a living. Johnson supported her mother until her death in 1898. In 1885, Charles G.D. Roberts published Johnson’s “A Cry from an Indian Wife” in The Week, Goldwin Smith’s Toronto magazine. She based it on events of the battle of Cut Knife Creek during the Riel Rebellion. Roberts and Johnson became lifelong friends. Johnson promoted her identity as a Mohawk, but as an adult spent little time with people of that culture. In 1885, Johnson traveled to Buffalo, New York to attend a ceremony honoring the Iroquois leader Sagoyewatha, also known as Red Jacket. She wrote a poem expressing admiration for him and a plea for reconciliation between British and Native peoples (Gray 2002, p. 90). In 1886, Johnson was commissioned to write a poem to mark the unveiling in Brantford of a statue honoring Joseph Brant, the important Mohawk leader who was allied with the British during and after the American Revolutionary War. Her “Ode to Brant” was read at a 13 October ceremony before “the largest crowd the little city had ever seen.” It called for brotherhood between Native and white Canadians under British imperial authority (Gray 2002, p. 90). The poem sparked a long article in the Toronto Globe, and increased interest in Johnson’s poetry and heritage. The Brantford businessman William F. Cockshutt read the poem at the ceremony, as Johnson was reportedly too shy. During the 1880s, Johnson built her reputation as a Canadian writer, regularly publishing in periodicals such as Globe, The Week, and Saturday Night. In the late 1880s and early 1890s, she published nearly every month, mostly in Saturday Night. Johnson was one of a group of Canadian authors contributing to a distinct national literature,. The inclusion of two of her poems in W.D. Lighthall’s anthology, Songs of the Great Dominion (1889), signaled her recognition and Theodore Watts-Dunton noted her for praise in his review of the book; he quoted her entire poem “In the Shadows” and called her “the most interesting poetess now living.” In her early works, Johnson wrote mostly about Canadian life, landscapes, and love in a post-Romantic mode, reflective of literary interests shared with her mother rather than her Mohawk heritage. The Young Men’s Liberal Association invited Johnson to a Canadian Authors Evening, held 16 January 1892 at the Toronto Art School Gallery. The only woman at the event, she read to an overflow crowd, along with luminaries such as Lighthall, William Wilfred Campbell, and Duncan Campbell Scott. “The poise and grace of this beautiful young woman standing before them captivated the audience even before she began to recite—not read, as the others had done”—her “Cry from an Indian Wife.” She was the only author to be called back for an encore. “She had scored a personal triumph and saved the evening from turning into a disaster.” The success of this performance began the poet’s 15-year stage career, as she was signed up by Frank Yeigh, who had organized the Liberal event. He gave her the headline for her first show on 19 February 1892, where she debuted a new poem written for the event, “The Song My Paddle Sings”. Johnson was perceived as quite young (although she was then 31), a beauty, and an exotic Native performer. After her first recital season, she decided to emphasize the Native aspects of her public figure by assembling and wearing a feminine Native costume. She wore it during the first part of the show, when reciting her dramatic “Indian” lyrics. At intermission she changed into fashionable English dress; in the second half, she appeared as a Victorian lady to recite her “English” verse. Johnson’s decision to develop her stage persona, and the popularity it inspired, showed that the audiences she encountered in Canada, England, and the United States recognized and were entertained by Native peoples in performance. There was great interest in Native Americans; the 1890s were also the period of popularity of Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show and ethnological aboriginal exhibits. Johnson and her siblings inherited an artifact collection from their father, which included significant items such as Mohawk wampum belts and spiritual masks. She used some items in her stage performances, but sold most later to museums, such as the Ontario Provincial Museum, or to collectors, such as the prominent American George Gustav Heye. Scholars have had difficulty identifying Johnson’s complete works, as much was published in periodicals. Her first volume of poetry, The White Wampum, was published in London, England in 1895. It was followed by Canadian Born in 1903. The contents of these volumes, together with additional poems, were published as the collection Flint and Feather in 1912. Reprinted many times, this book has been one of the best-selling titles of Canadian poetry. Since the 1917 edition, Flint and Feather has been misleadingly subtitled “The Complete Poems of E. Pauline Johnson”. But in 2002, professors Carole Gerson and Veronica Strong-Boag produced an edition, Tekahionwake: Collected Poems and Selected Prose, that contains all of Johnson’s poems found up to that date. Later life After retiring from the stage in August 1909, Johnson moved to Vancouver, British Columbia and continued writing. Her pieces included a series of articles for the Daily Province, based on stories related by her friend Chief Joe Capilano of the Squamish people of North Vancouver. In 1911, to help support Johnson, who was ill and poor, a group of friends organized the publication of these stories under the title Legends of Vancouver. They remain classics of that city’s literature. One of the stories was a Squamish legend of shape shifting: how a man was transformed into Siwash Rock “as an indestructible monument to Clean Fatherhood”. In another, Johnson told the history of Deadman’s Island, a small islet off Stanley Park. In a poem in the collection, she named one of her favourite areas “Lost Lagoon”, as the inlet seemed to disappear when the water emptied at low tide. The body of water has since been transformed into a permanent, fresh-water lake at Stanley Park, but it is still called “Lost Lagoon”. The posthumous Shagganappi (1913) and The Moccasin Maker (1913) are collections of selected stories first published in periodicals. Johnson wrote on a variety of sentimental, didactic, and biographical topics. Veronica Strong-Boag and Carole Gerson provided a provisional chronological list of Johnson’s writings in their book Paddling Her Own Canoe: The Times and Texts of E. Pauline Johnson (Tekahionwake) (2000). Johnson died of breast cancer in Vancouver, British Columbia on 7 March 1913. Her funeral (the largest until then in Vancouver history) was held on what would have been her 52nd birthday. Her ashes were buried near Siwash Rock in Stanley Park. In 1922 a cairn was erected at the burial site, with an inscription reading in part, “in memory of one whose life and writings were an uplift and a blessing to our nation”. Criticism and legacy Despite the acclaim she received from contemporaries, Johnson had a decline in reputation in the decades after her death. It was not until 1961, with commemoration of the centenary of her birth, that Johnson began to be recognized as an important Canadian cultural figure. A number of biographers and literary critics have downplayed her literary contributions, as they contend that her performances contributed most to her literary reputation during her lifetime. W. J. Keith wrote: “Pauline Johnson’s life was more interesting than her writing... with ambitions as a poet, she produced little or nothing of value in the eyes of critics who emphasize style rather than content.” The author Margaret Atwood admitted that she did not study literature by Native authors when preparing Survival: A Thematic Guide to Canadian Literature (1972), her seminal work. At its publication, she had said she could not find Native works. She mused, “Why did I overlook Pauline Johnson? Perhaps because, being half-white, she somehow didn’t rate as the real thing, even among Natives; although she is undergoing reclamation today.” Atwood’s comments indicated that Johnson’s multicultural identity contributed to her neglect by critics. As Atwood noted, since the late 20th century, Johnson’s writings and performance career have been reevaluated by literary, feminist, and postcolonial critics. They have appreciated her importance as a New Woman and a figure of resistance to dominant ideas about race, gender, Native Rights, and Canada. The growth in literature written by First Nations people during the 1980s and 1990s has prompted writers and scholars to investigate Native oral and written literary history, to which Johnson made a significant contribution. Legacy and honours * In 1922, the city of Vancouver erected a monument in Pauline Johnson’s honour at her well-loved Stanley Park. * 1945, Johnson was designated a Person of National Historic Significance. * In 1961, on the centennial of her birth, Johnson was celebrated with a commemorative stamp bearing her image, “rendering her the first woman (other than the Queen), the first author, and the first aboriginal Canadian to be thus honored.”. * Four Canadian schools have been named in Johnson’s honour: elementary schools in West Vancouver, British Columbia; Scarborough, Ontario; Hamilton, Ontario; and Burlington, Ontario; and a high school in Brantford, Ontario. * Chiefswood, Johnson’s childhood home constructed in 1856 in Brantford, has been listed as a National Historic Site because of both her father’s and her own historical importance. Preserved as a house museum, it is the oldest Native mansion surviving from pre-Confederation times. * An Ontario Historical Plaque was erected in front of the Chiefswood house museum by the province to commemorate E. Pauline Johnson’s role in the region’s heritage. * The Canadian actor Donald Sutherland read the following quote from her poem “Autumn’s Orchestra”, at the opening ceremonies of the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver. * Know by the thread of music woven through * This fragile web of cadences I spin, * That I have only caught these songs since you * Voiced them upon your haunting violin. * In 2010, composer Jeff Enns was commissioned to create a song based on Johnson’s poem “At Sunset”. His work was sung and recorded by the Canadian Chamber Choir under the artistic direction of Julia Davids. * The City Opera of Vancouver commissioned Pauline, a chamber opera dealing with her life, her multicultural identity, and her art. The composer is the Canadian Tobin Stokes, and the libretto was written by Margaret Atwood. The work premiered on 23 May 2014, at the York Theatre in Vancouver. The first opera to be written about Pauline Johnson, it is set 101 years earlier, in the last week of her life. Family history * The Mohawk ancestors of Johnson’s father, Chief George Henry Martin Johnson, had historically lived in what became the state of New York, the Mohawk traditional homeland in the present-day United States. In 1758, her great-grandfather Tekahionwake was born in New York. When he was baptized, he took the name Jacob Johnson, taking his surname from Sir William Johnson, the influential British Superintendent of Indian Affairs, who acted as his godfather. The Johnson surname was subsequently passed down in the family. * After the American Revolutionary War started, Loyalists in the Mohawk Valley came under intense pressure. The Mohawk and three other Iroquois tribes were allies of the British rather than the rebel colonists. Jacob Johnson and his family moved to Canada. After the war they settled permanently in Ontario on land given by the Crown in partial compensation for Iroquois losses of territory in New York. * His son John Smoke Johnson had a talent for oratory, spoke English as well as Mohawk, and demonstrated his patriotism to the Crown during the War of 1812. As a result, John Smoke Johnson was made a Pine Tree Chief at the request of the British government. Although John Smoke Johnson’s title could not be inherited, his wife Helen Martin was descended from the Wolf Clan and a founding family of the Six Nations. Through her lineage and influence (as the Mohawk were matrilineal), their son George Johnson was named chief. * Chief George Johnson inherited his father’s gift for languages and began his career as a church translator on the Six Nations reserve. Assisting the Anglican missionary, Johnson met his sister-in-law Emily Howells. They fell in love and married. In 1853, the couple’s interracial marriage displeased both the Johnson and Howells families. (Several prominent Canadian families were descended from 18th and 19th-century marriages between British fur traders, who had capital and social standing, and daughters of First Nations chiefs, which had been considered economic and social alliances.) The birth of their first child reconciled the Johnson family to the marriage. In 1856 Johnson built Chiefswood, a wood mansion where the family lived for years. * In his roles as government interpreter and hereditary Chief, George Johnson developed a reputation as a talented mediator between Native and European interests. He was well respected in Ontario. He also made enemies because of his efforts to stop illegal trading of reserve timber. Physically attacked by Native and non-Native men involved in this traffic, Johnson suffered from health problems afterward. He died of a fever in 1884. * Emily Howells was born in England to a well-established British family who immigrated to the United States in 1832. Her father Henry Howells was a Quaker and intended to join the American abolitionist movement. Emily’s mother Mary Best Howells had died when the girl was five, before the family left England. Her father married again before they immigrated. In the US, he moved his family to several American cities, where he founded schools to gain an income, before settling in Eaglewood, New Jersey. After his second wife died (women had a high mortality in childbirth), Howells married a third time, and fathered a total of 24 children. He opposed slavery and encouraged his children to “pray for the blacks and to pity the poor Indians. Nevertheless, his compassion did not preclude the view that his own race was superior to others”. * At the age of 21, Emily Howells moved to the Six Nations reserve in Ontario, Canada to join her older sister, who had moved there with her Anglican missionary husband. Emily helped her care for her growing family. After falling in love with the Mohawk George Johnson, Howells gained a better understanding of the Native peoples and some perspective on her father’s beliefs.

My name is Jessica Joehanson I am fourteen I live in Farmington Maine and Jesus is my number one. I am an a métier poet. I'm at a very low point in my life but I find myself more and more inspired every day by my crushing heartbreak. I have no plans to become and professional poet it's just a hobby. My poems are based on real life events and my emotions, thoughts, and dreams. My favorite quote is "Somethings are to beautiful captured, you just have to let them be." I am a dreamer and I will always be this way.

Samuel Johnson (18 September 1709 – 13 December 1784), often referred to as Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions to English literature as a poet, essayist, moralist, literary critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer. Johnson was a devout Anglican and committed Tory, and has been described as “arguably the most distinguished man of letters in English history”. He is also the subject of “the most famous single biographical work in the whole of literature,” James Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson. Born in Lichfield, Staffordshire, Johnson attended Pembroke College, Oxford for just over a year, before his lack of funds forced him to leave. After working as a teacher, he moved to London, where he began to write for The Gentleman’s Magazine. His early works include the biography Life of Mr Richard Savage, the poems London and The Vanity of Human Wishes, and the play Irene.

Hi, My name is Amanda Joannevaeh Steinbrecher. Everyone calls me Lady J. I am 27 years old. I have two children, a nine year old son named Shayn Azriel and a three year old daughter named Nacirema Jillian. I used to be very shy and timid. I would hide all of my poetry, so no one would see my true feelings and emotions. I have been writing poetry for as long as I can remember. In second grade I won an Echoes Theatre Award for my writing, and the awards, certificates, and recognitions have continued consistently on in my life. Poetry is my greatest outlet to express myself. I ahve always used poetry as my escape from pain, and always go back to re read everything I write to see where I have been in the past emotionally and mentally, and to stay update reading how far I have come. Some of my poetry will make you sad, or be sensitive to some readers, so I ask that you read at your own risk. Other pieces I have written are very motivatioanl and inspirational. I hope and pray that through my poetry I can help inspire others who may have faced some of the same struggles I have myself. I pray everyone on here with be abundantly bless with joy,peace,harmony, happiness, laughter, and Love. God Bless You All !! Sincerely, <3 Lady J. <3

Lionel Pigot Johnson (15 March 1867– 4 October 1902) was an English poet, essayist and critic. Life Johnson was born at Broadstairs, and educated at Winchester College and New College, Oxford, graduating in 1890. He became a Catholic convert in 1891. He lived a solitary life in London, struggling with alcoholism and his repressed homosexuality. He died of a stroke after a fall in the street, though it was said to be a fall from a barstool in the Green Dragon in Fleet Street. During his lifetime were published his The Art of Thomas Hardy (1894), Poems (1895), Ireland and Other Poems (1897). He was one of the Rhymers’ Club, and cousin to Olivia Shakespear (who dedicated her novel The False Laurel to him). In June 1891, Johnson converted to Catholicism, at the same time as he introduced his cousin Lord Alfred Douglas to his friend Oscar Wilde, whom he then repudiated, directing a sonnet at him called “The Destroyer of a Soul” (1892). In 1893, Johnson wrote what some consider his masterpiece, “The Dark Angel”. “The Dark Angel” also served as one of the influences for the Dark Angels chapter of Space Marines in the Warhammer 40,000 fictional universe. Their Primarch, Lion El’Jonson, is also named after the poet. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lionel_Johnson

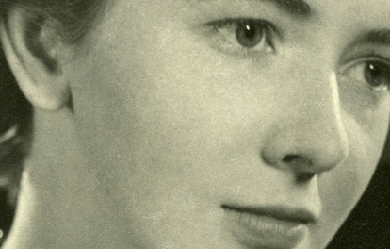

Elizabeth Jennings CBE (18 July 1926– 26 October 2001) was an English poet. Life and career Jennings was born in Boston, Lincolnshire. When she was six, her family moved to Oxford, where she remained for the rest of her life. There she later attended St Anne’s College. After graduation, she became a writer. Jennings’ early poetry was published in journals such as Oxford Poetry, New English Weekly, The Spectator, Outposts and Poetry Review, but her first book was not published until she was 27. The lyrical poets she cited as having influenced her were Hopkins, Auden, Graves and Muir. Her second book, A Way of Looking, won the Somerset Maugham award and marked a turning point, as the prize money allowed her to spend nearly three months in Rome, which was a revelation. It brought a new dimension to her religious belief and inspired her imagination. Regarded as traditionalist rather than an innovator, Jennings is known for her lyric poetry and mastery of form. Her work displays a simplicity of metre and rhyme shared with Philip Larkin, Kingsley Amis and Thom Gunn, all members of the group of English poets known as The Movement. She always made it clear that, whilst her life, which included a spell of severe mental illness, contributed to the themes contained within her work, she did not write explicitly autobiographical poetry. Her deeply held Roman Catholicism coloured much of her work. She died in a care home in Bampton, Oxfordshire and is buried in Wolvercote Cemetery, Oxford. Selected honours and awards 1953: Arts Council of Great Britain Prize for the best first book of poems for Poems 1955: Somerset Maugham Prize for A Way of Looking. 1987: W.H. Smith Literary Award for Collected Poems 1953–1985 1992: Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) 2001: Honorary Doctorate of Divinity from Durham University

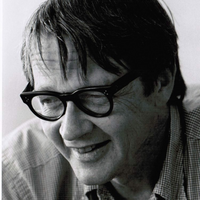

Randall Jarrell (May 6, 1914– October 14, 1965) was an American poet, literary critic, children’s author, essayist, novelist, and the 11th Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress, a position that now bears the title Poet Laureate. Biography Youth and education Jarrell was a native of Nashville, Tennessee. He attended Hume-Fogg High School where he “practiced tennis, starred in some school plays, and began his career as a critic with satirical essays in a school magazine.” He received his B.A. from Vanderbilt University in 1935. While at Vanderbilt, he edited the student humor magazine The Masquerader, was captain of the tennis team, made Phi Beta Kappa and graduated magna cum laude. He studied there under Robert Penn Warren, who first published Jarrell’s criticism; Allen Tate, who first published Jarrell’s poetry; and John Crowe Ransom, who gave Jarrell his first teaching job as a Freshman Composition instructor at Kenyon College in Gambier, Ohio. Although all of these Vanderbilt teachers were heavily involved with the conservative Southern Agrarian movement, Jarrell did not become an Agrarian himself. According to Stephen Burt, “Jarrell—a devotee of Marx and Auden—embraced his teachers’ literary stances while rejecting their politics.” He also completed his master’s degree in English at Vanderbilt in 1937, beginning his thesis on A. E. Housman (which he completed in 1939). When Ransom left Vanderbilt for Kenyon College in Ohio that same year, a number of his loyal students, including Jarrell, followed him to Kenyon. Jarrell taught English at Kenyon for two years, coached tennis, and served as the resident faculty member in an undergraduate dormitory that housed future writers Robie Macauley, Peter Taylor, and poet Robert Lowell. Lowell and Jarrell remained good friends and peers until Jarrell’s death. According to Lowell biographer Paul Mariani, "Jarrell was the first person of [Lowell’s] own generation [whom he] genuinely held in awe" due to Jarrell’s brilliance and confidence even at the age of 23. Career Jarrell went on to teach at the University of Texas at Austin from 1939 to 1942, where he began to publish criticism and where he met his first wife, Mackie Langham. In 1942 he left the university to join the United States Army Air Forces. According to his obituary, he "[started] as a flying cadet, [then] he later became a celestial navigation tower operator, a job title he considered the most poetic in the Air Force." His early poetry would focus on the subject of his war-time experiences in the Air Force. The Jarrell obituary goes on to state that “after being discharged from the service he joined the faculty of Sarah Lawrence College in Bronxville, N.Y., for a year. During his time in New York, he also served as the temporary book review editor for The Nation magazine.” However, Jarrell was uncomfortable living in the city and “claimed to hate New York’s crowds, high cost of living, status-conscious sociability, and lack of greenery.” He didn’t end up staying in the city for long. Instead, he left for the Woman’s College of the University of North Carolina where, as an associate professor of English, he taught modern poetry and “imaginative writing.” Jarrell divorced his first wife and married Mary von Schrader, a young woman whom he met at a summer writer’s conference in Colorado, in 1952. They first lived together while Jarrell was teaching for a term at the University of Illinois at Champaign-Urbana. Then the couple settled back in Greensboro with Mary’s daughters from her previous marriage. The couple also moved temporarily to Washington D.C. in 1956 when Jarrell served as the consultant in poetry at the Library of Congress (a position that later became titled “Poet Laureate”) for two years, returning to Greensboro and the University of North Carolina after his term ended. Depression and death Towards the end of his life, in 1963, Stephen Burt notes, "Randall’s behavior began to change. Approaching his fiftieth birthday, he seems to have worried deeply about his advancing age. . . After President Kennedy was shot, Randall spent days in front of the television weeping. Sad to the point of inertia, Randall sought help from a Cincinnati psychiatrist, who prescribed [the antidepressant drug] Elavil." The drug made him manic and in 1965, he was hospitalized and taken off Elavil. At this point, he was no longer manic, but he became depressed again. Burt also states, "In April The New York Times published a viciously condescending review of [Jarrell’s most recent book of poems] The Lost World. Soon afterwards, Jarrell slashed a wrist and returned to the hospital." After leaving the hospital, he stayed at home that summer under his wife’s care and returned to teaching at the University of North Carolina that fall. Then, near dusk on October 14, 1965, while walking along U.S. highway 15-501 near Chapel Hill, N.C., where he had gone seeking medical treatment, Jarrell was struck by a car and killed. In trying to determine the cause of death, "[Jarrell’s wife] Mary, the police, the coroner, and ultimately the state of North Carolina judged his death accidental, a verdict made credible by his apparent improvements in health. . .and the odd, sidelong manner of the collision; medical professionals judged the injuries consistent with an accident and not with suicide." Nevertheless, because Jarrell had recently been treated for mental illness and a previous suicide attempt, some of the people closest to him weren’t entirely convinced that his death was accidental and suspected that he might have committed suicide. In a letter to Elizabeth Bishop about a week after Jarrell’s death, Robert Lowell wrote, "There’s a small chance [that Jarrell’s death] was an accident. . . [but] I think it was suicide, and so does everyone else, who knew him well." Jarrell’s death being a suicide has since become accepted practically as fact, even by people who were not personally close to him. The idea has been perpetuated by some well known writers. A. Alvarez, in his book The Savage God, lists Jarrell as a twentieth-century writer who killed himself, and James Atlas refers to Jarrell’s “suicide” multiple times in his biography of Delmore Schwartz. The idea of Jarrell’s death being a suicide was always denied by his wife. Legacy On February 28, 1966, a memorial service was held in Jarrell’s honor at Yale University, and some of the best-known poets in the country attended and spoke at the event, including Robert Lowell, Richard Wilbur, John Berryman, Stanley Kunitz, and Robert Penn Warren. Reporting on the memorial service, The New York Times quoted Lowell who said that Jarrell was "'the most heartbreaking poet of our time’. . . [and] had written ‘the best poetry in English about the Second World War.’" These memorial tributes formed the basis for the book Randall Jarrell 1914-1965 which Farrar, Straus and Giroux published the following year. In 2004, the Metropolitan Nashville Historical Commission approved placement of a historical marker in his honor, to be placed at his alma mater, Hume-Fogg High School. A North Carolina Highway Historical Marker was placed near his burial site in Greensboro, North Carolina. Some of the awards that he received during his lifetime included a Guggenheim Fellowship for 1947-48, a grant from the National Institute of Arts and Letters in 1951, and the National Book Award for Poetry in 1961. Writing Poetry In terms of the subject matter of Jarrell’s work, the scholar Stephen Burt observed, “Randall Jarrell’s best-known poems are poems about the Second World War, poems about bookish children and childhood, and poems, such as ‘Next Day,’ in the voices of aging women.” Burt also succinctly summarizes the essence of Jarrell’s poetic style as follows: Jarrell’s stylistic particularities have been hard for critics to hear and describe, both because the poems call readers’ attention instead to their characters and because Jarrell’s particular powers emerge so often from mimesis of speech. Jarrell’s style responds to the alienations it delineates by incorporating or troping speech and conversation, linking emotional events within one person’s psyche to speech acts that might take place between persons. . .Jarrell’s style pivots on his sense of loneliness and on the intersubjectivity he sought as a response. Jarrell’s first collection of poetry, Blood for a Stranger, which was heavily influenced by W.H. Auden, was published in 1942– the same year he enlisted in the United States Army Air Corps. His second and third books, Little Friend, Little Friend (1945) and Losses (1948), drew heavily on his Army experiences. The short lyric “The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner” is Jarrell’s most famous war poem and one that is frequently anthologized. His reputation as a poet was not firmly established until 1960 when his National Book Award-winning collection The Woman at the Washington Zoo was published. Starting with this book, Jarrell broke free of Auden’s influence and the influence of the New Critics and developed a style that mixed Modernist and Romantic influences, incorporating the aesthetics of William Wordsworth in order to create more sympathetic character sketches and dramatic monologues. The scholar Stephen Burt notes, “Jarrell took from Wordsworth the idea that poems had to be 'convincing as speech’ before they were anything else.” His final volume, The Lost World, published in 1965, continued in the same style and cemented Jarrell’s reputation as a poet; many critics consider it to be his best work. Stephen Burt states that "in the 'Lost World’ poems and throughout Jarrell’s oeuvre. . .he took care to define and defend the self [and]. . .his lonely personae seek intersubjective confirmation and . . .his alienated characters resist the so-called social world." Burt identifies the chief influences on Jarrell’s poetry to be "Proust, Wordsworth, Rilke, Freud, and the poets and thinkers of Jarrell’s era [particularly his close friend, Hannah Arendt].” Criticism From the start of his writing career, Jarrell earned a solid reputation as an influential poetry critic. Encouraged by Edmund Wilson, who published Jarrell’s criticism in The New Republic, Jarrell developed his style of critique which was often witty and sometimes fiercely critical. However, as he got older, his criticism began to change, showing a more positive emphasis. His appreciations of Robert Lowell, Elizabeth Bishop, and William Carlos Williams helped to establish or resuscitate their reputations as significant American poets, and his poet/friends often returned the favor, as when Lowell wrote a review of Jarrell’s book of poems The Seven League Crutches in 1951. Lowell wrote that Jarrell was “the most talented poet under forty, and one whose wit, pathos, and grace remind us more of Pope or Matthew Arnold than of any of his contemporaries.” In the same review, Lowell calls Jarrell’s first book of poems, Blood for A Stranger, “a tour-de-force in the manner of Auden.” And in another book review for Jarrell’s Selected Poems, a few years later, fellow-poet Karl Shapiro compared Jarrell to “the great modern Rainer Maria Rilke” and stated that the book “should certainly influence our poetry for the better. It should become a point of reference, not only for younger poets, but for all readers of twentieth-century poetry.” Jarrell is also noted for his essays on Robert Frost—whose poetry was a large influence on Jarrell’s own—Walt Whitman, Marianne Moore, Wallace Stevens, and others, which were mostly collected in Poetry and the Age (1953). Many scholars consider him the most astute poetry critic of his generation, and in 1979, the poet and scholar Peter Levi went so far as to advise younger writers, “Take more notice of Randall Jarrell than you do of any academic critic.” In an introduction to a selection of Jarrell’s essays, the poet Brad Leithauser wrote the following assessment of Jarrell as a critic: [Jarrell’s] multiple and eclectic virtues—originality, erudition, wit, probity, and an irresistible passion—combined to make him the best American poet-critic since Eliot. Or one could call him, after granting Eliot the English citizenship he so actively embraced, the best poet-critic we have ever had. Whichever side of the Atlantic one chooses to place Eliot, Jarrell was his superior in at least one significant respect. He captured a world that any contemporary poet will recognize as “the poetry scene”; his Poetry and the Age might even now be retitled Poetry and Our Age. Fiction, translations, and children’s books In addition to poetry and criticism, Jarrell also published a satiric novel, Pictures from an Institution, in 1954 (a National Book Award for Fiction finalist)—drawing upon his teaching experiences at Sarah Lawrence College, which served as the model for the fictional Benton College. He also wrote several children’s books, among which The Bat-Poet (1964) and The Animal Family (1965) are considered prominent (and feature illustrations by Maurice Sendak). Jarrell translated poems by Rainer Maria Rilke and others, a play by Anton Chekhov, and several Grimm fairy tales. Bibliography * Blood for A Stranger. NY: Harcourt, 1942. * Little Friend, Little Friend. NY: Dial, 1945. * Losses. NY: Harcourt, 1948. * The Seven League Crutches. NY: Harcourt, 1951. * Poetry and the Age. NY: Knopf, 1953. * Pictures from an Institution: A Comedy. New York: Knopf, 1954 * Selected Poems. New York: Knopf, 1955. * Randall Jarrell’s Book of Stories: An Anthology. Selected and with an introduction by Randall Jarrell. New York: New York Review Books, 1958. * The Woman at the Washington Zoo: Poems and Translations. New York: Atheneum, 1960. * A Sad Heart at the Supermarket: Essays & Fables. NY: Atheneum, 1962. * Selected Poems including The Woman at the Washington Zoo. NY: Macmillan, 1964. * The Bat-Poet. Pictures by Maurice Sendak. NY: Macmillan, 1964. * The Gingerbread Rabbit. Illustrated by Garth Williams. NY: Random House, 1965 * The Lost World. NY: Macmillan, 1965. * The Animal Family. Illustrated by Maurice Sendak. NY: Pantheon Books, 1965. * Randall Jarrell, 1914-1965. Edited by Robert Lowell, Peter Taylor, and Robert Penn Warren. NY: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1968. * The Third Book of Criticism. NY: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1969. * The Complete Poems. NY: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1969. * Fly by Night. Illustrated by Maurice Sendak. NY: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1976. * “Faust: Part One” by Goethe, (translator). Farrah, Straus & Giroux 1976 * Kipling, Auden & Co.: Essays and Reviews, 1935-1964. NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1979. * Randall Jarrell’s Letters: An Autobiographical and Literary Selection. edited by Mary Jarrell and Stuart Wright. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1985. * Selected Poems. Edited by William Pritchard. NY: Farrar, Straus, & Giroux, 1990. * No Other Book: Selected Essays. Edited by Brad Leithauser. NY: HarperCollins, 1995. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Randall_Jarrell

"O God, I could be bounded in a nutshell, and count myself a king of infinite space – were it not that I have bad dreams." – William Shakespeare (Hamlet: Act 2, Scene 2) Hey, I'm Jett. My poetry is what it looks like in my mind. I live more in my head than I do in my house. Age: 17 Pronouns: She/Her Zodiac: Aquarius Region: North America

Donald Justice was an American poet and teacher of writing. In summing up Justice's career David Orr wrote, "In most ways, Justice was no different from any number of solid, quiet older writers devoted to traditional short poems. But he was different in one important sense: sometimes his poems weren't just good; they were great. They were great in the way that Elizabeth Bishop's poems were great, or Thom Gunn's or Philip Larkin's. They were great in the way that tells us what poetry used to be, and is, and will be." Justice grew up in Florida and earned a bachelor's degree from the University of Miami in 1945. He received an M.A. from the University of North Carolina in 1947, studied for a time at Stanford University, and ultimately earned a doctorate from the University of Iowa in 1954. He went on to teach for many years at the Iowa Writers' Workshop, the nation's first graduate program in creative writing. He also taught at Syracuse University, the University of California at Irvine, Princeton University, the University of Virginia, and the University of Florida in Gainesville. Justice published thirteen collections of his poetry. The first collection, The Summer Anniversaries, was the winner of the Lamont Poetry Prize given by the Academy of American Poets in 1961; Selected Poems won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1980. He was awarded the Bollingen Prize in Poetry in 1991, and the Lannan Literary Award for Poetry in 1996. He was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and a Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets from 1997 to 2003. His Collected Poems was nominated for the National Book Award in 2004. Justice was also a National Book Award Finalist in 1961, 1974, and 1995. In his obituary, Andrew Rosenheim notes that Justice "was a legendary teacher, and despite his own Formalist reputation influenced a wide range of younger writers — his students included Mark Strand, Rita Dove, James Tate, Jorie Graham and the novelist John Irving". His student and later colleague Marvin Bell said in a reminiscence, "As a teacher, Don chose always to be on the side of the poem, defending it from half-baked attacks by students anxious to defend their own turf. While he had firm preferences in private, as a teacher Don defended all turfs. He had little use for poetic theory..." Of Justice's accomplishments as a poet, his former student, the poet and critic Tad Richards, noted that "Donald Justice is likely to be remembered as a poet who gave his age a quiet but compelling insight into loss and distance, and who set a standard for craftsmanship, attention to detail, and subtleties of rhythm." Justice's work was the subject of the 1998 volume Certain Solitudes: On The Poetry of Donald Justice, a collection of essays edited by Dana Gioia and William Logan. Poetry * The Old Bachelor and Other Poems (Pandanus Press, Miami, FL), 1951. * The Summer Anniversaries (Wesleyan University Press, Middletown, CT), 1960; revised edition (University Press of New England, Hanover, NH), 1981. * A Local Storm (Stone Wall Press, Iowa City, IA, 1963). * Night Light (Wesleyan University Press, Middletown, CT, 1967); revised edition (University Press of New England, Hanover, NH, 1981). * Sixteen Poems (Stone Wall Press, Iowa City, IA, 1970). * From a Notebook (Seamark Press, Iowa City, IA, 1971). * Departures (Atheneum, New York, NY, 1973). * Selected Poems (Atheneum, New York, NY, 1979). * Tremayne (Windhover Press, Iowa City, IA, 1984). * The Sunset Maker (Anvil Press Poetry, 1987). * A Donald Justice Reader (Middlebury, 1991). * New and Selected Poems (Knopf, 1995). * Orpheus Hesitated beside the Black River: Poems, 1952-1997 (Anvil Press Poetry, London, England), 1998. * Collected Poems (Knopf, 2004). Essay and interview collections * Oblivion: On Writers and Writing, 1998 * Platonic Scripts, 1984 References Wikipedia—http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Donald_Justice

I have always used poetry as a means to express my highest thoughts and deepest feelings down on paper. Now, I hope they can inspire you, to perhaps do the same, and look inward. For a more in-depth look into my work, click the link to my debut novel. https://www.philosophypsychologyprinciplespractice.com/ Also, check out my Pinterest page for more inspirational content: https://www.pinterest.com.au/SigmaSocrates/_created/

Violet Jacob (1 September 1863– 9 September 1946) was a Scottish writer, now known especially for her historical novel Flemington and her poetry, mainly in Scots. Life She was born Violet Augusta Mary Frederica Kennedy-Erskine, the daughter of William Henry Kennedy-Erskine (1 July 1828– 15 September 1870) of Dun, Forfarshire, a Captain in the 17th Lancers and Catherine Jones (d. 13 February 1914), the only daughter of William Jones of Henllys, Carmarthenshire. Her father was the son of John Kennedy-Erskine (1802–1831) of Dun and Augusta FitzClarence (1803–1865), the illegitimate daughter of King William IV and Dorothy Jordan. She was a great-granddaughter of Archibald Kennedy, 1st Marquess of Ailsa. The area of Montrose where her family seat of Dun was situated was the setting for much of her fiction. She married, on 27 October 1894, Arthur Otway Jacob, an Irish Major in the British Army, and accompanied him to India where he was serving. Her book Diaries and letters from India 1895-1900 is about their stay in the Central Indian town of Mhow. The couple had one son, Harry, born in 1895, who died as a soldier at the battle of the Somme in 1916. Arthur died in 1936, and Violet returned to live at Kirriemuir, in Angus. Scots poetry In her poetry Violet Jacob was associated with Scots revivalists like Marion Angus, Alexander Gray and Lewis Spence in the Scottish Renaissance, which drew its inspiration from early Scots poets such as Robert Henryson and William Dunbar, rather than from Robert Burns. She is commemorated in Makars’ Court, outside the Writers’ Museum, Lawnmarket, Edinburgh. Selections for Makars’ Court are made by the Writers’ Museum, The Saltire Society and The Scottish Poetry Library. The Wild Geese, which takes the form of a conversation between the poet and the North Wind, is a sad poem of longing for home. It was set to music as Norlan’ Wind and popularised by Angus singer and songmaker Jim Reid, who set to music other poems by Jacob and other Angus poets such as Marion Angus and Helen Cruikshank. Another popular version, sung by Cilla Fisher and Artie Trezise, appeared on their 1979 Topic Records album Cilla and Artie.