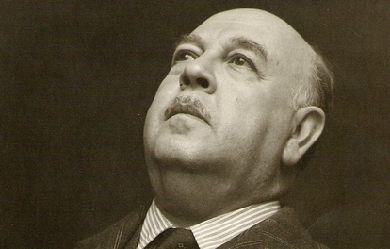

James Whitcomb Riley (October 7, 1849 – July 22, 1916) was an American writer, poet, and best-selling author. During his lifetime he was known as the "Hoosier Poet" and "Children's Poet" for his dialect works and his children's poetry respectively. His poems tended to be humorous or sentimental, and of the approximately one thousand poems that Riley authored, the majority are in dialect. His famous works include "Little Orphant Annie" and "The Raggedy Man". Riley began his career writing verses as a sign maker and submitting poetry to newspapers. Thanks in part to an endorsement from poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, he eventually earned successive jobs at Indiana newspaper publishers during the latter 1870s. Riley gradually rose in prominence during the 1880s through his poetry reading tours. He traveled a touring circuit first in the Midwest, and then nationally, holding shows and making joint appearances on stage with other famous talents. Regularly struggling with his alcohol addiction, Riley never married or had children, and created a scandal in 1888 when he became too drunk to perform. He became more popular in spite of the bad press he received, and as a result extricated himself from poorly negotiated contracts that limited his earnings; he quickly became very wealthy. Riley became a bestselling author in the 1890s. His children's poems were compiled into a book and illustrated by Howard Chandler Christy. Titled the Rhymes of Childhood, the book was his most popular and sold millions of copies. As a poet, Riley achieved an uncommon level of fame during his own lifetime. He was honored with annual Riley Day celebrations around the United States and was regularly called on to perform readings at national civic events. He continued to write and hold occasional poetry readings until a stroke paralyzed his right arm in 1910. Riley's chief legacy was his influence in fostering the creation of a midwestern cultural identity and his contributions to the Golden Age of Indiana Literature. Along with other writers of his era, he helped create a caricature of midwesterners and formed a literary community that produced works rivaling the established eastern literati. There are many memorials dedicated to Riley, including the James Whitcomb Riley Hospital for Children. Family and background James Whitcomb Riley was born on October 7, 1849, in the town of Greenfield, Indiana, the third of the six children of Reuben Andrew and Elizabeth Marine Riley.[n 1] Riley's father was an attorney, and in the year before Riley's birth, he was elected a member of the Indiana House of Representatives as a Democrat. He developed a friendship with James Whitcomb, the governor of Indiana, after whom he named his son. Martin Riley, Riley's uncle, was an amateur poet who occasionally wrote verses for local newspapers. Riley was fond of his uncle who helped influence his early interest in poetry. Shortly after Riley's birth, the family moved into a larger house in town. Riley was "a quiet boy, not talkative, who would often go about with one eye shut as he observed and speculated." His mother taught him to read and write at home before sending him to the local community school in 1852. He found school difficult and was frequently in trouble. Often punished, he had nothing kind to say of his teachers in his writings. His poem "The Educator" told of an intelligent but sinister teacher and may have been based on one of his instructors. Riley was most fond of his last teacher, Lee O. Harris. Harris noticed Riley's interest in poetry and reading and encouraged him to pursue it further. Riley's school attendance was sporadic, and he graduated from grade eight at age twenty in 1869. In an 1892 newspaper article, Riley confessed that he knew little of mathematics, geography, or science, and his understanding of proper grammar was poor. Later critics, like Henry Beers, pointed to his poor education as the reason for his success in writing; his prose was written in the language of common people which spurred his popularity. Childhood influences Riley lived in his parents' home until he was twenty-one years old. At five years old he began spending time at the Brandywine Creek just outside Greenfield. His poems "The Barefoot Boy" and "The Old Swimmin' Hole" referred back to his time at the creek. He was introduced in his childhood to many people who later influenced his poetry. His father regularly brought home a variety of clients and disadvantaged people to give them assistance. Riley's poem "The Raggedy Man" was based on a German tramp his father hired to work at the family home. Riley picked up the cadence and character of the dialect of central Indiana from travelers along the old National Road. Their speech greatly influenced the hundreds of poems he wrote in nineteenth century Hoosier dialect. Riley's mother frequently told him stories of fairies, trolls, and giants, and read him children's poems. She was very superstitious, and influenced Riley with many of her beliefs. They both placed "spirit rappings" in their homes on places like tables and bureaus to capture any spirits that may have been wandering about. This influence is recognized in many of his works, including "Flying Islands of the Night." As was common at that time, Riley and his friends had few toys and they amused themselves with activities. With his mother's aid, Riley began creating plays and theatricals which he and his friends would practice and perform in the back of a local grocery store. As he grew older, the boys named their troupe the Adelphians and began to have their shows in barns where they could fit larger audiences. Riley wrote of these early performances in his poem "When We First Played 'Show'," where he referred to himself as "Jamesy." Many of Riley's poems are filled with musical references. Riley had no musical education, and could not read sheet music, but learned from his father how to play guitar, and from a friend how to play violin. He performed in two different local bands, and became so proficient on the violin he was invited to play with a group of adult Freemasons at several events. A few of his later poems were set to music and song, one of the most well known being A Short'nin' Bread Song—Pieced Out. When Riley was ten years old, the first library opened in his hometown. From an early age he developed a love of literature. He and his friends spent time at the library where the librarian read stories and poems to them. Charles Dickens became one Riley's favorites, and helped inspire the poems "St. Lirriper," "Christmas Season," and "God Bless Us Every One." Riley's father enlisted in the Union Army during the American Civil War, leaving his wife to manage the family home. While he was away, the family took in a twelve-year-old orphan named Mary Alice "Allie" Smith. Smith was the inspiration for Riley's poem "Little Orphant Annie". Riley intended to name the poem "Little Orphant Allie", but a typesetter's error changed the name of the poem during printing. Finding poetry Riley's father returned from the war partially paralyzed. He was unable to continue working in his legal practice and the family soon fell into financial distress. The war had a negative physiological effect on him, and his relationship with his family quickly deteriorated. He opposed Riley's interest in poetry and encouraged him to find a different career. The family finances finally disintegrated and they were forced to sell their town home in April 1870 and return to their country farm. Riley's mother was able to keep peace in the family, but after her death in August from heart disease, Riley and his father had a final break. He blamed his mother's death on his father's failure to care for her in her final weeks. He continued to regret the loss of his childhood home and wrote frequently of how it was so cruelly snatched from him by the war, subsequent poverty, and his mother's death. After the events of 1870, he developed an addiction to alcohol which he struggled with for the remainder of his life. Becoming increasingly belligerent toward his father, Riley moved out of the family home and briefly had a job painting houses before leaving Greenfield in November 1870. He was recruited as a Bible salesman and began working in the nearby town of Rushville, Indiana. The job provided little income and he returned to Greenfield in March 1871 where he started an apprenticeship to a painter. He completed the study and opened a business in Greenfield creating and maintaining signs. His earliest known poems are verses he wrote as clever advertisements for his customers. Riley began participating in local theater productions with the Adelphians to earn extra income, and during the winter months, when the demand for painting declined, Riley began writing poetry which he mailed to his brother living in Indianapolis. His brother acted as his agent and offered the poems to the newspaper Indianapolis Mirror for free. His first poem was featured on March 30, 1872 under the pseudonym "Jay Whit." Riley wrote more than twenty poems to the newspaper, including one that was featured on the front page. In July 1872, after becoming convinced sales would provide more income than sign painting, he joined the McCrillus Company based in Anderson, Indiana. The company sold patent medicines that they marketed in small traveling shows around Indiana. Riley joined the act as a huckster, calling himself the "Painter Poet". He traveled with the act, composing poetry and performing at the shows. After his act he sold tonics to his audience, sometimes employing dishonesty. During one stop, Riley presented himself as a formerly blind painter who had been cured by a tonic, using himself as evidence to encourage the audience to purchase his product. Riley began sending poems to his brother again in February 1873. About the same time he and several friends began an advertisement company. The men traveled around Indiana creating large billboard-like signs on the sides of buildings and barns and in high places that would be visible from a distance. The company was financially successful, but Riley was continually drawn to poetry. In October he traveled to South Bend where he took a job at Stockford & Blowney painting verses on signs for a month; the short duration of his job may have been due to his frequent drunkenness at that time. In early 1874, Riley returned to Greenfield to become a writer full-time. In February he submitted a poem entitled "At Last" to the Danbury News, a Connecticut newspaper. The editors accepted his poem, paid him for it, and wrote him a letter encouraging him to submit more. Riley found the note and his first payment inspiring. He began submitting poems regularly to the editors, but after the newspaper shut down in 1875, Riley was left without a paying publisher. He began traveling and performing with the Adelphians around central Indiana to earn an income while he searched for a new publisher. In August 1875 he joined another traveling tonic show run by the Wizard Oil Company. Newspaper work Riley began sending correspondence to the famous American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow during late 1875 seeking his endorsement to help him start a career as a poet. He submitted many poems to Longfellow, whom he considered to be the greatest living poet. Not receiving a prompt response, he sent similar letters to John Townsend Trowbridge, and several other prominent writers askng for an endorsement. Longfellow finally replied in a brief letter, telling Riley that "I have read [the poems] in great pleasure, and think they show a true poetic faculty and insight." Riley carried the letter with him everywhere and, hoping to receive a job offer and to create a market for his poetry, he began sending poems to dozens of newspapers touting Longfellow's endorsement. Among the newspapers to take an interest in the poems was the Indianapolis Journal, a major Republican Party metropolitan newspaper in Indiana. Among the first poems the newspaper purchased from Riley were "Song of the New Year", "An Empty Nest", and a short story entitled "A Remarkable Man". The editors of the Anderson Democrat discovered Riley's poems in the Indianapolis Journal and offered him a job as a reporter in February 1877. Riley accepted. He worked as a normal reporter gathering local news, writing articles, and assisting in setting the typecast on the printing press. He continued to write poems regularly for the newspaper and to sell other poems to larger newspapers. During the year Riley spent working in Anderson, he met and began to court Edora Mysers. The couple became engaged, but terminated the relationship after they decided against marriage in August. After a rejection of his poems by an eastern periodical, Riley began to formulate a plot to prove his work was of good quality and that it was being rejected only because his name was unknown in the east. Riley authored a poem imitating the style of Edgar Allan Poe and submitted it to the Kokomo Dispatch under a fictitious name claiming it was a long lost Poe poem. The Dispatch published the poem and reported it as such. Riley and two other men who were part of the plot waited two weeks for the poem to be published by major newspapers in Chicago, Boston, and New York to gauge their reaction; they were disappointed. While a few newspapers believed the poem to be authentic, the majority did not, claiming the quality was too poor to be authored by Poe. An employee of the Dispatch learned the truth of the incident and reported it to the Kokomo Tribune, which published an expose that outed Riley as a conspirator behind the hoax. The revelation damaged the credibility of the Dispatch and harmed Riley's reputation. In the aftermath of the Poe plot, Riley was dismissed from the Democrat, so he returned to Greenfield to spend time writing poetry. Back home, he met Clara Louise Bottsford, a school teacher boarding in his father's home. They found they had much in common, particularly their love of literature. The couple began a twelve-year intermittent relationship which would be Riley's longest lasting. In mid-1878 the couple had their first breakup, caused partly by Riley's alcohol addiction. The event led Riley to make his first attempt to give up liquor. He joined a local temperance organization, but quit after a few weeks. Performing poet Without a steady income, his financial situation began to deteriorate. He began submitting his poems to more prominent literary magazines, including Scribner's Monthly, but was informed that although he showed promise, his work was still short of the standards required for use in their publications. Locally, he was still dealing with the stigma of the Poe plot. The Indianapolis Journal and other newspapers refused to accept his poetry, leaving Riley desperate for income. In January 1878 on the advice of a friend, Riley paid an entrance fee to join a traveling lecture circuit where he could give poetry readings. In exchange, he received a portion of the profit his performances earned. Such circuits were popular at the time, and Riley quickly earned a local reputation for his entertaining readings. In August 1878, Riley followed Indiana Governor James D. Williams as speaker at a civic event in a small town near Indianapolis. He recited a recently composed poem, "A Childhood Home of Long Ago," telling of life in pioneer Indiana. The poem was well received and was given good reviews by several newspapers. "Flying Islands of the Night" is the only play that Riley wrote and published. Authored while Riley was traveling with the Adelphians, but never performed, the play has similarities to A Midsummer Night's Dream, which Riley may have used as a model. Flying Islands concerns a kingdom besieged by evil forces of a sinister queen who is defeated eventually by an angel-like heroine. Most reviews were positive. Riley published the play and it became popular in the central Indiana area during late 1878, helping Riley to convince newspapers to again accept his poetry. In November 1879 he was offered a position as a columnist at the Indianapolis Journal and accepted after being encouraged by E.B. Matindale, the paper's chief editor. Although the play and his newspaper work helped expose him to a wider audience, the chief source of his increasing popularity was his performances on the lecture circuit. He made both dramatic and comedic readings of his poetry, and by early 1879 could guarantee large crowds whenever he performed. In an 1894 article, Hamlin Garland wrote that Riley's celebrity resulted from his reading talent, saying "his vibrant individual voice, his flexible lips, his droll glance, united to make him at once poet and comedian—comedian in the sense in which makes for tears as well as for laughter." Although he was a good performer, his acts were not entirely original in style; he frequently copied practices developed by Samuel Clemens and Will Carleton. His tour in 1880 took him to every city in Indiana where he was introduced by local dignitaries and other popular figures, including Maurice Thompson with whom he began to develop a close friendship. Developing and maintaining his publicity became a constant job, and received more of his attention as his fame grew. Keeping his alcohol addiction secret, maintaining the persona of a simple rural poet and a friendly common person became most important. Riley identified these traits as the basis of his popularity during the mid-1880s, and wrote of his need to maintain a fictional persona. He encouraged the stereotype by authoring poetry he thought would help build his identity. He was aided by editorials he authored and submitted to the Indianapolis Journal offering observations on events from his perspective as a "humble rural poet". He changed his appearance to look more mainstream, and began by shaving his mustache off and abandoning the flamboyant dress he employed in his early circuit tours. By 1880 his poems were beginning to be published nationally and were receiving positive reviews. "Tom Johnson's Quit" was carried by newspapers in twenty states, thanks in part to the careful cultivation of his popularity. Riley became frustrated that despite his growing acclaim, he found it difficult to achieve financial success. In the early 1880s, in addition to his steady performing, Riley began producing many poems to increase his income. Half of his poems were written during the period. The constant labor had adverse effects on his health, which was worsened by his drinking. At the urging of Maurice Thompson, he again attempted to stop drinking liquor, but was only able to give it up for a few months. Politics In March 1888, Riley traveled to Washington, D.C. where he had dinner at the White House with other members of the International Copyright League and President of the United States Grover Cleveland. Riley made a brief performance for the dignitaries at the event before speaking about the need for international copyright protections. Cleveland was enamored by Riley's performance and invited him back for a private meeting during which the two men discussed cultural topics. In the 1888 Presidential Election campaign, Riley's acquaintance Benjamin Harrison was nominated as the Republican candidate. Although Riley had shunned politics for most of his life, he gave Harrison a personal endorsement and participated in fund-raising events and vote stumping. The election was exceptionally partisan in Indiana, and Riley found the atmosphere of the campaign stressful; he vowed never to become involved with politics again. Upon Harrison's election, he suggested Riley be named the national poet laureate, but Congress failed to act on the request. Riley was still honored by Harrison and visited him at the White House on several occasions to perform at civic events. Pay problems and scandal Riley and Nye made arrangements with James Pond to make two national tours during 1888 and 1889. The tours were popular and generally sold out, with hundreds having to be turned away. The shows were usually forty-five minutes to an hour long and featured Riley reading often humorous poetry interspersed by stories and jokes from Nye. The shows were informal and the two men adjusted their performances based on their audiences reactions. Riley memorized forty of his poems for the shows to add to his own versatility. Many prominent literary and theatrical people attended the shows. At a New York City show in March 1888, Augustin Daly was so enthralled by the show he insisted on hosting the two men at a banquet with several leading Broadway theatre actors. Despite Riley serving as the act's main draw, he was not permitted to become an equal partner in the venture. Nye and Pond both received a percentage of the net profit, while Riley was paid a flat rate for each performance. In addition, because of Riley's past agreements with the Redpath Lyceum Bureau, he was required to pay half of his fee to his agent Amos Walker. This caused the other men to profit more than Riley from his own work. To remedy this situation, Riley hired his brother-in-law Henry Eitel, an Indianapolis banker, to manage his finances and act on his behalf to try and extricate him from his contract. Despite discussions and assurances from Pond that he would work to address the problem, Eitel had no success. Pond ultimately made the situation worse by booking months of solid performances, not allowing Riley and Nye a day of rest. These events affected Riley physically and emotionally; he became despondent and began his worst period of alcoholism. During November 1889, the tour was forced to cancel several shows after Riley became severely inebriated at a stop in Madison, Wisconsin. Walker began monitoring Riley and denying him access to liquor, but Riley found ways to evade Walker. At a stop at the Masonic Temple Theatre in Louisville, Kentucky, in January 1890, Riley paid the hotel's bartender to sneak whiskey to his room. He became too drunk to perform, and was unable to travel to the next stop. Nye terminated the partnership and tour in response. The reason for the breakup could not be kept secret, and hotel staff reported to the Louisville Courier-Journal that they saw Riley in a drunken stupor walking around the hotel. The story made national news and Riley feared his career was ruined. He secretly left Louisville at night and returned to Indianapolis by train. Eitel defended Riley to the press in an effort to gain sympathy for Riley, explaining the abusive financial arrangements his partners had made. Riley however refused to speak to reporters and hid himself for weeks. Much to Riley's surprise, the news reports made him more popular than ever. Many people thought the stories were exaggerated, and Riley's carefully cultivated image made it difficult for the public to believe he was an alcoholic. Riley had stopped sending poetry to newspapers and magazines in the aftermath, but they soon began corresponding with him requesting that he resume writing. This encouraged Riley, and he made another attempt to give up liquor as he returned to his public career. The negative press did not end however, as Nye and Pond threatened to sue Riley for causing their tour to end prematurely. They claimed to have lost $20,000. Walker threatened a separate suit demanding $1,000. Riley hired Indianapolis lawyer William P. Fishback to represent him and the men settled out of court. The full details of the settlement were never disclosed, but whatever the case, Riley finally extricated himself from his old contracts and became a free agent. The exorbitant amount Riley was being sued for only reinforced public opinion that Riley had been mistreated by his partners, and helped him maintain his image. Nye and Riley remained good friends, and Riley later wrote that Pond and Walker were the source of the problems. Riley's poetry had become popular in Britain, in large part due to his book Old-Fashioned Roses. In May 1891 he traveled to England to make a tour and what he considered a literary pilgrimage. He landed in Liverpool and traveled first to Dumfries, Scotland, the home and burial place of Robert Burns. Riley had long been compared to Burns by critics because they both used dialect in their poetry and drew inspiration from their rural homes. He then traveled to Edinburgh, York, and London, reciting poetry for gatherings at each stop. Augustin Daly arranged for him to give a poetry reading to prominent British actors in London. Riley was warmly welcomed by its literary and theatrical community and he toured places that Shakespeare had frequented. Riley quickly tired of traveling abroad and began longing for home, writing to his nephew that he regretted having left the United States. He curtailed his journey and returned to New York City in August. He spent the next months in his Greenfield home attempting to write an epic poem, but after several attempts gave up, believing he did not possess the ability. By 1890, Riley had authored almost all of his famous poems. The few poems he did write during the 1890s were generally less well received by the public. As a solution, Riley and his publishers began reusing poetry from other books and printing some of his earliest works. When Neighborly Poems was published in 1891, a critic working for the Chicago Tribune pointed out the use of Riley's earliest works, commenting that Riley was using his popularity to push his crude earlier works onto the public only to make money. Riley's newest poems published in the 1894 book Armazindy received very negative reviews that referred to poems like "The Little Dog-Woggy" and "Jargon-Jingle" as "drivel" and to Riley as a "worn out genius." Most of his growing number of critics suggested that he ignored the quality of the poems for the sake of making money. National poet Riley had become very wealthy by the time he ended touring in 1895, and was earning $1,000 a week. Although he retired, he continued to make minor appearances. In 1896, Riley performed four shows in Denver. Most of the performances of his later life were at civic celebrations. He was a regular speaker at Decoration Day events and delivered poetry before the unveiling of monuments in Washington, D.C. Newspapers began referring to him as the "National Poet", "the poet laureate of America", and "the people's poet laureate". Riley wrote many of his patriotic poems for such events, including "The Soldier", "The Name of Old Glory", and his most famous such poem, "America!". The 1902 poem "America, Messiah of Nations" was written and read by Riley for the dedication of the Indianapolis Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument. The only new poetry Riley published after the end of the century were elegies for famous friends. The poetic qualities of the poems were often poor, but they contained many popular sentiments concerning the deceased. Among those he eulogized were Benjamin Harrison, Lew Wallace, and Henry Lawton. Because of the poor quality of the poems, his friends and publishers requested that he stop writing them, but he refused. In 1897, Riley's publishers suggested that he create a multi-volume series of books containing his complete life works. With the help of his nephew, Riley began working to compile the books, which eventually totaled sixteen volumes and were finally completed in 1914. Such works were uncommon during the lives of writers, attesting to the uncommon popularity Riley had achieved. His works had become staples for Ivy League literature courses and universities began offering him honorary degrees. The first was Yale in 1902, followed by a Doctorate of Letters from the University of Pennsylvania in 1904. Wabash College and Indiana University granted him similar awards. In 1908 he was elected member of the National Institute of Arts and Letters, and in 1912 they conferred upon him a special medal for poetry. Riley was influential in helping other poets start their careers, having particularly strong influences on Hamlin Garland, William Allen White, and Edgar Lee Masters. He discovered aspiring African American poet Paul Laurence Dunbar in 1892. Riley thought Dunbar's work was "worthy of applause", and wrote him letters of recommendation to help him get his work published. Declining health In 1901, Riley's doctor diagnosed him with neurasthenia, a nervous disorder, and recommended long periods of rest as a cure.[173] Riley remained ill for the rest of his life and relied on his landlords and family to aid in his care. During the winter months he moved to Miami, Florida, and during summer spent time with his family in Greenfield. He made only a few trips during the decade, including one to Mexico in 1906. He became very depressed by his condition, writing to his friends that he thought he could die at any moment, and often used alcohol for relief.[174] In March 1909, Riley was stricken a second time with Bell's palsy, and partial deafness, the symptoms only gradually eased over the course of the year.[175] Riley was a difficult patient, and generally refused to take any medicine except the patent medicines he had sold in his earlier years; the medicines often worsened his conditions, but his doctors could not sway his opinion.[176] On July 10, 1910 he suffered a stroke that paralyzed the right side of his body. Hoping for a quick recovery, his family kept the news from the press until September. Riley found the loss of use of his writing hand the worst part of the stroke, which served only to further depress him.[174][177] With his health so poor, he decided to work on a legacy by which to be remembered in Indianapolis. In 1911 he donated land and funds to build a new library on Pennsylvania Avenue.[178] By 1913, with the aid of a cane, Riley began to recover his ability to walk. His inability to write, however, nearly ended his production of poems. George Ade worked with him from 1910 through 1916 to write his last five poems and several short autobiographical sketches as Riley dictated. His publisher continued recycling old works into new books, which remained in high demand.[178] Since the mid-1880s, Riley had been the nation's most read poet, a trend that accelerated at the turn of the century. In 1912 Riley recorded readings of his most popular poetry to be sold by Victor Records. Riley was the subject of three paintings by T. C. Steele. The Indianapolis Arts Association commissioned a portrait of Riley to be created by world famous painter John Singer Sargent. Riley's image became a nationally known icon and many businesses capitalized on his popularity to sell their products; Hoosier Poet brand vegetables became a major trade-name in the midwest.[179] In 1912, the governor of Indiana instituted Riley Day on the poet's birthday. Schools were required to teach Riley's poems to their children, and banquet events were held in his honor around the state. In 1915 and 1916 the celebration was national after being proclaimed in most states. The annual celebration continued in Indiana until 1968.[180] In early 1916 Riley was filmed as part of a movie to celebrate Indiana's centennial, the video is on display at the Indiana State Library.[181][182] Death and legacy On July 22, 1916, Riley suffered a second stroke. He recovered enough during the day to speak and joke with his companions. He died before dawn the next morning, July 23.[183] Riley's death shocked the nation and made front page headlines in major newspapers.[184] President Woodrow Wilson wrote a brief note to Riley's family offering condolences on behalf the entire nation. Indiana Governor Samuel M. Ralston offered to allow Riley to lie in state at the Indiana Statehouse—Abraham Lincoln being the only other person to have previously received such an honor.[185] During the ten hours he lay in state on July 24, more than thirty-five thousand people filed past his bronze casket; the line was still miles long at the end of the day and thousands were turned away. The next day a private funeral ceremony was held and attended by many dignitaries. A large funeral procession then carried him to Crown Hill Cemetery where he was buried in a tomb at the top of the hill, the highest point in the city of Indianapolis.[186] Within a year of Riley's death many memorials were created, including several by the James Whitcomb Riley Memorial Association. The James Whitcomb Riley Hospital for Children was created and named in his honor by a group of wealthy benefactors and opened in 1924. In the following years, other memorials intended to benefit children were created, including Camp Riley for youth with disabilities.[187][188] The memorial foundation purchased the poet's Lockerbie home in Indianapolis and it is now maintained as a museum. The James Whitcomb Riley Museum Home is the only late-Victorian home in Indiana that is open to the public and the United States' only late-Victorian preservation, featuring authentic furniture and decor from that era. His birthplace and boyhood home, now the James Whitcomb Riley House, is preserved as a historical site.[189] A Liberty ship, commissioned April 23, 1942, was christened the SS James Whitcomb Riley. It served with the United States Maritime Commission until being scrapped in 1971. James Whitcomb Riley High School opened in South Bend, Indiana in 1924. In 1950, there was a James Whitcomb Riley Elementary School in Hammond, Indiana, but it was torn down in 2006. East Chicago, Indiana had a Riley School at one time, as did neighboring Gary, Indiana and Anderson, Indiana. One of New Castle, Indiana's elementary schools is named for Riley as is the road on which it is located. The former Greenfield High School was converted to Riley Elementary School and listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1986. In 1940, the U.S. Postal Service issued a 10-cent stamp honoring Riley.[190] As a lasting tribute, the citizens of Greenfield hold a festival every year in Riley's honor. Taking place the first or second weekend of October, the "Riley Days" festival traditionally commences with a flower parade in which local school children place flowers around Myra Reynolds Richards' statue of Riley on the county courthouse lawn, while a band plays lively music in honor of the poet. Weeks before the festival, the festival board has a queen contest. The 2010–2011 queen was Corinne Butler. The pageant has been going on many years in honor of the Hoosier poet[191] According to historian Elizabeth Van Allen, Riley was instrumental in helping form a midwestern cultural identity. The midwestern United States had no significant literary community before the 1880s.[192] The works of the Western Association of Writers, most notably those of Riley and Wallace, helped create the midwest's cultural identity and create a rival literary community to the established eastern literari. For this reason, and the publicity Riley's work created, he was commonly known as the "Hoosier Poet." Critical reception and style Riley was among the most popular writers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, known for his "uncomplicated, sentimental, and humorous" writing.[195] Often writing his verses in dialect, his poetry caused readers to recall a nostalgic and simpler time in earlier American history. This gave his poetry a unique appeal during a period of rapid industrialization and urbanization in the United States. Riley was a prolific writer who "achieved mass appeal partly due to his canny sense of marketing and publicity."[195] He published more than fifty books, mostly of poetry and humorous short stories, and sold millions of copies.[195] Riley is often remembered for his most famous poems, including the "The Raggedy Man" and "Little Orphant Annie". Many of his poems, including those, where partially autobiographical, as he used events and people from his childhood as an inspiration for subject matter.[195] His poems often contained morals and warnings for children, containing messages telling children to care for the less fortunate of society. David Galens and Van Allen both see these messages as Riley's subtle response to the turbulent economic times of the Gilded Age and the growing progressive movement.[196] Riley believed that urbanization robbed children of their innocence and sincerity, and in his poems he attempted to introduce and idolize characters who had not lost those qualities.[197] His children's poems are "exuberant, performative, and often display Riley's penchant for using humorous characterization, repetition, and dialect to make his poetry accessible to a wide-ranging audience."[195][198] Although hinted at indirectly in some poems, Riley wrote very little on serious subject matter, and actually mocked attempts at serious poetry. Only a few of his sentimental poems concerned serious subjects. "Little Mandy's Christmas-Tree", "The Absence of Little Wesley", and "The Happy Little Cripple" were about poverty, the death of a child, and disabilities. Like his children's poems, they too contained morals, suggesting society should pity the downtrodden and be charitable.[195][198] Riley wrote gentle and romantic poems that were not in dialect. They generally consisted of sonnets and were strongly influenced by the works of John Greenleaf Whittier, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and Alfred, Lord Tennyson. His standard English poetry was never as popular as his Hoosier dialect poems.[195] Still less popular were the poems Riley authored in his later years; most were to commemorate important events of American history and to eulogize the dead.[195] Riley's contemporaries acclaimed him "America's best-loved poet".[195][198] In 1920, Henry Beers lauded the works of Riley "as natural and unaffected, with none of the discontent and deep thought of cultured song."[195] Samuel Clemens, William Dean Howells, and Hamlin Garland, each praised Riley's work and the idealism he expressed in his poetry. Only a few critics of the period found fault with Riley's works. Ambrose Bierce criticized Riley for his frequent use of dialect. Bierce accused Riley of using dialect to "cover up [the] faulty construction" of his poems.[195] Edgar Lee Masters found Riley's work to be superficial, claiming it lacked irony and that he had only a "narrow emotional range".[195] By the 1930s popular critical opinion towards Riley's works began to shift in favor of the negative reviews. In 1951, James T. Farrell said Riley's works were "cliched." Galens wrote that modern critics consider Riley to be a "minor poet, whose work—provincial, sentimental, and superficial though it may have been—nevertheless struck a chord with a mass audience in a time of enormous cultural change."[195] Thomas C. Johnson wrote that what most interests modern critics was Riley's ability to market his work, saying he had a unique understanding of "how to commodify his own image and the nostalgic dreams of an anxious nation."[195] Among the earliest widespread criticisms of Riley were opinions that his dialect writing did not actually represent the true dialect of central Indiana. In 1970 Peter Revell wrote that Riley's dialect was more similar to the poor speech of a child rather than the dialect of his region. Revell made extensive comparison to historical texts and Riley's dialect usage. Philip Greasley wrote that that while "some critics have dismissed him as sub-literary, insincere, and an artificial entertainer, his defenders reply that an author so popular with millions of people in different walks of life must contribute something of value, and that his faults, if any, can be ignored." References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Whitcomb_Riley

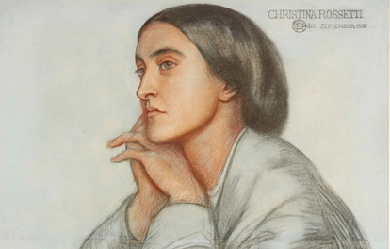

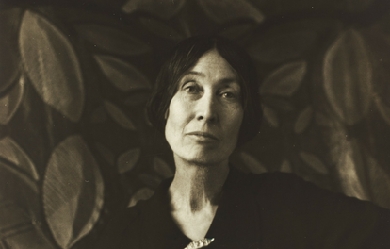

In 1830, Christina Rossetti was born in London, one of four children of Italian parents. Her father was the poet Gabriele Rossetti; her brother Dante Gabriel Rossetti also became a poet and a painter. Rossetti’s first poems were written in 1842 and printed in the private press of her grandfather. In 1850, under the pseudonym Ellen Alleyne, she contributed seven poems to the Pre-Raphaelite journal The Germ, which had been founded by her brother William Michael and his friends.

[b.] September 25, 1974, Tempe, AZ; [p.] Mr. Phil and Barbara K. Ransopher; [ed.] Bachelor of Arts in English (Language and Lit.); [occ.] library assistant, writer, editor; [memb.] Yahoo Groups: Appreciating Poetry (owner), Erotica Gallery (owner), Ex BBC Poetry Group (moderator), AATNAANPT (An All Totally New An All New Poetry Thread), Adult Amatuer (sic) Writers Emporium; [hon.] November 19, 2010 Poetic Skies Poem Of The Week (Her Love Has A Cold Wet Nose), May 15, 2015, First weekly winner for Fortune Poets group A Soldier's Fortune, 2015 Poet of the year for Fortune Poets; [pers.] I write what I see in my mind, what I feel in my heart, and what I know in my soul; [a.] Garland, TX

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (12 May 1828 – 9 April 1882) was an English poet, illustrator, painter and translator. He founded the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in 1848 with William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais, and was later to be the main inspiration for a second generation of artists and writers influenced by the movement, most notably William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones. His work also influenced the European Symbolists and was a major precursor of the Aesthetic movement.

I am very passionate about writing especially poetry because it speaks to my soul. I'm looking forward to become a professional writer someday and get published. I want to share my writing talent worldwide and I won't stop until I do. While I'm here at "Poeticous". I would like to receive honest feedback on my writings, but I can see people don't really comment, they only view. So what's the point of Poet's like myself sharing our poetry? if no one is willing to comment. Also, they may like the poem but refuse to press the "like" button..........I just don't understand that!!!

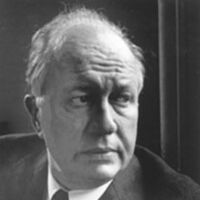

Edwin Arlington Robinson (December 22, 1869—April 6, 1935) was an American poet who won three Pulitzer Prizes for his work. He was born in Head Tide, Lincoln County, Maine but his family moved to Gardiner, Maine in 1871. He described his childhood in Maine as “stark and unhappy”: His parents (who had wanted a girl) did not name him until he was six months old, when they visited a holiday resort—whereupon, other vacationers decided that he should have a name and selected a man from Arlington, Massachusetts to draw a name out of a hat. Throughout his life, he not only hated his given name, but also his family’s habit of calling him “Win.” As an adult, he always used the signature “E. A.”

Welcome to my poetry page, I think its a blast, Some of my Poetry is about my past. Lots of wonderful words are written and funny, I don't get paid so it wont cost you money. My poems are of the wonders of life someone said I have written about the dead. Some people may be offended by some of my rhymes, So if your offended don't come back to read next time. But if my poetry makes you laugh please come back, Because this Yorkshire man has a sense of humour and can be really daft.

Alfonso Reyes Ochoa (Monterrey, 17 de mayo de 1889 - México, D.F., 27 de diciembre de 1959) fue un poeta, ensayista, narrador, diplomático y pensador mexicano. Se le conoce también como «el regiomontano universal». Fue el noveno de los doce hijos del general Bernardo Reyes y de doña Aurelia Ochoa. Su padre ocupó importantes cargos durante los gobiernos de Porfirio Díaz (fue gobernador del estado de Nuevo León y Secretario de Guerra y Marina). Alfonso Reyes es un escritor clásico, formalista, comedido, su prosa nos hace pensar en el modelo apolíneo de Nietzsche. Sus temas y preocupaciones fueron siempre los grandes temas de la cultura clásica griega. Fue considerado por Borges “el mejor prosista del idioma español del siglo XX”.

Lonnie Rutledge is a prolific artist, songwriter, and poet from the United States. He is known for his peculiar methods, intense concepts, experimental writing and often demented production. He has described his style as 'Schizodelic'; a term he is noted for coining in the mid 1990's. Lxnnnie has released many albums under assorted aliases in multiple genres of music. He has had songs featured in major motion pictures, produced music for a number of commercials, designed album covers and published a book of poetry.

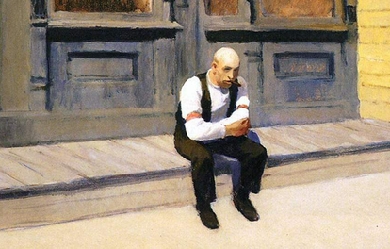

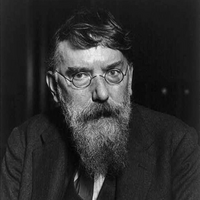

Theodore Roethke (ret-kee; May 25, 1908 – August 1, 1963) was an American poet, who published several volumes of poetry characterized by its rhythm, rhyming, and natural imagery. He was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for poetry in 1954 for his book, The Waking, and he won the annual National Book Award for Poetry twice, in 1959 for Words for the Wind and posthumously in 1965 for The Far Field. Roethke was born in Saginaw, Michigan and grew up on the west side of the Saginaw River. His father, Otto, was a German immigrant, a market-gardener who owned a large local 25 acre greenhouse, along with his brother (Theodore's uncle). Much of Theodore's childhood was spent in this greenhouse, as reflected by the use of natural images in his poetry. The poet's adolescent years were jarred, however, by his uncle's suicide and by the death of his father from cancer, both in early 1923, when Theodore (Ted) was only 15. These deaths shaped Roethke's psyche and creative life. He attended the University of Michigan, earning A.B. and M.A. degrees. He briefly attended law school before entering Harvard University, where he studied under the poet Robert Hillyer. Abandoning graduate study because of the Great Depression, he taught English at several universities, including Lafayette College, Pennsylvania State University, and Bennington College. In 1940, he was expelled from his position at Lafayette and he returned to Michigan. Just prior to his return, he had an affair with established poet and critic Louise Bogan, who later became one of his strongest early supporters. While teaching at Michigan State University in East Lansing, he began to suffer from manic depression, which fueled his poetic impetus. His last teaching position was at the University of Washington, leading to an association with the poets of the American Northwest. Some of his best known students included James Wright, Carolyn Kizer, Jack Gilbert, Richard Hugo, and David Wagoner. In 1953, Roethke married Beatrice O'Connell, a former student. Like many other American poets of his generation, Roethke was a heavy drinker and susceptible, as mentioned, to bouts of mental illness. He did not inform O'Connell of his repeated episodes of depression, yet she remained dedicated to him and his work. She ensured the posthumous publication of his final volume of poetry, The Far Field, which includes the poem "Meditation at Oyster River." In 1961, "The Return" was featured on George Abbe's album Anthology of Contemporary American Poetry on Folkways Records. The following year, Roethke released his own album on the label entitled, Words for the Wind: Poems of Theodore Roethke. He suffered a heart attack in his friend S. Rasnics' swimming pool in 1963 and died on Bainbridge Island, Washington, aged 55. The pool was later filled in and is now a zen rock garden, which can be viewed by the public at the Bloedel Reserve, a 150-acre (60 hectare) former private estate. There is no sign to indicate that the rock garden was the site of Roethke's death. There is a sign that commemorates his boyhood home and burial in Saginaw, Michigan. The historical marker notes in part: Theodore Roethke (1908–1963) wrote of his poetry: The greenhouse "is my symbol for the whole of life, a womb, a heaven-on-earth." Roethke drew inspiration from his childhood experiences of working in his family's Saginaw floral company. Beginning is 1941 with Open House, the distinguished poet and teacher published extensively, receiving a Pulitzer Prize for poetry and two National Book Awards among an array of honors. In 1959 Pennsylvania University awarded him the Bollingen Prize. Roethke taught at Michigan State College, (present-day Michigan State University) and at colleges in Pennsylvania and Vermont, before joining the faculty of the University of Washington at Seattle in 1947. Roethke died in Washington in 1963. His remains are interred in Saginaw's Oakwood Cemetery. The Friends of Theodore Roethke Foundation maintains his birthplace at 1805 Gratiot in Saginaw as a museum. In 1995, the Seattle alley between Seventh and Eighth Avenues N.E. running from N.E. 45th Street to N.E. 47th Street was named Roethke Mews in his honor. It adjoins the Blue Moon Tavern, one of Roethke's haunts. Critical responses The poet Stanley Kunitz said of Roethke, "The poet of my generation who meant most to me, in his person and in his art, was Theodore Roethke." The Poetry Foundation entry on Roethke notes early reviews of his work and Roethke's response to that early criticism: W. H. Auden called [Roethke's first book] Open House "completely successful." In another review of the book, Elizabeth Drew felt "his poems have a controlled grace of movement and his images the utmost precision; while in the expression of a kind of gnomic wisdom which is peculiar to him as he attains an austerity of contemplation and a pared, spare strictness of language very unusual in poets of today." Roethke kept both Auden's and Drew's reviews, along with other favorable reactions to his work. As he remained sensitive to how peers and others he respected should view his poetry, so too did he remain sensitive to his introspective drives as the source of his creativity. Understandably, critics picked up on the self as the predominant preoccupation in Roethke's poems. Roethke's breakthrough book, The Lost Son, also won him considerable praise. For instance, Michael Harrington felt "Roethke found his own voice and central themes in The Lost Son and Stanley Kunitz saw a "confirmation that he was in full possession of his art and of his vision." In Against Oblivion, an examination of forty-five twentieth century poets, the critic Ian Hamilton also praised this book, writing, "In Roethke's second book, The Lost Son, there are several of these greenhouse poems and they are among the best things he wrote; convincing and exact, and rich in loamy detail." In addition to the well-known greenhouse poems, the Poetry Foundation notes that Roethke also won praise "for his love poems which first appeared in The Waking and earned their own section in the new book [and] 'were a distinct departure from the painful excavations of the monologues and in some respects a return to the strict stanzaic forms of the earliest work,' [according to the poet] Stanley Kunitz. [The critic] Ralph Mills described 'the amatory verse' as a blend of 'consideration of self with qualities of eroticism and sensuality; but more important, the poems introduce and maintain a fascination with something beyond the self, that is, with the figure of the other, or the beloved woman.'" In reviewing his posthumously published Collected Poems in 1966, Karl Malkoff of The Sewanee Review wrote: Bibliography * Open House (1941) * The Lost Son and Other Poems (1948) * Praise to the End! (1951) * The Waking (1953) * Words For The Wind (1958) * I Am! Says The Lamb (1961) * Party at the Zoo" (1963) (A Modern Masters Book for Children, illustrated by Al Swiller) * The Far Field (1964) * Dirty Dinky and Other Creatures: Poems for Children (1973) * On Poetry and Craft: Selected Prose and Craft of Theodore Roethke (Copper Canyon Press, 2001) * Straw for the Fire: From the Notebooks of Theodore Roethke, 1943-63 (1972; Copper Canyon * Press, 2006) (selected and arranged by David Wagoner) References Wikipedia - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theodore_Roethke

I have been writing poetry since 2011 and I love doing it because I can express myself. I was bored one day and pick up a pen and paper and started putting words together on paper and now I am passionate about it. I write songs and short stories also but I am more better at writing poetry. I love music very much and I love fashion.

Adrienne Cecile Rich (May 16, 1929– March 27, 2012) was an American poet, essayist and radical feminist. She was called “one of the most widely read and influential poets of the second half of the 20th century”, and was credited with bringing “the oppression of women and lesbians to the forefront of poetic discourse.” Her first collection of poetry, A Change of World, was selected by renowned poet W. H. Auden for the Yale Series of Younger Poets Award. Auden went on to write the introduction to the published volume. She famously declined the National Medal of Arts, protesting the vote by House Speaker Newt Gingrich to end funding for the National Endowment for the Arts. Adrienne Rich was born in Baltimore, Maryland, the elder of two sisters. Her father, renowned pathologist Arnold Rice Rich, was the Chairman of Pathology at The Johns Hopkins Medical School. Her mother, Helen Elizabeth (Jones) Rich, was a concert pianist and a composer. Her father was from a Jewish family, and her mother was Southern Protestant; the girls were raised as Christians. Adrienne Rich’s early poetic influence stemmed from her father who encouraged her to read but also to write her own poetry. Her interest in literature was sparked within her father’s library where she read the work of writers such as Ibsen, Arnold, Blake, Keats, Rossetti, and Tennyson. Her father was ambitious for Adrienne and “planned to create a prodigy.” Adrienne Rich and her younger sister were home schooled by their mother until Adrienne began public education in the fourth grade. The poems Sources and After Dark document her relationship with her father, describing how she worked hard to fulfill her parents’ ambitions for her—moving into a world in which she was expected to excel.

I am a believing and practicing Christian. I study God's word daily. I write Christian poetry but I also write on other topics. My poems are very simple. I don't use fancy or big words so this may be disappointing to some. I love the old Classic Poets like Sara Teasdale, Robert Louis Stevenson, and a whole host of others. I love all kinds of music from hard rock to classical. I'd like to share a few quotes, sorry I do not have all the names of the authors; Never allow someone to be your priority while allowing yourself to be their option” “A woman often thinks she regrets the lover, when she only regrets the love” By Francois de la Rochefoucauld “One of the hardest things in life is watching the person you love, love someone else.” “The one that seems to love the least, has the most control, in a relationship” “I love walking in the rain, 'cause then no-one knows I'm crying.” “Until this moment, I never understood how hard it was to lose something you never had.” “Being hurt by someone you truly care about leaves a hole in you heart that only love can fill.” “The love that lasts the longest is the love that is never returned.” "I dropped a tear in the ocean, and when you find it, that is when I will stop loving you. A few Quotes from Me, Debra A man should always, say what he means, and mean what he says, because, this is his signature. The more people you have in your life, the more problems, there will be to endure. Smart is a woman who guards her heart. Foolish is a woman, who lets a man, tare her heart apart. © Debra

John Crowe Ransom (April 30, 1888– July 3, 1974) was an American educator, scholar, literary critic, poet, essayist and editor. He is considered to be a founder of the New Criticism school of literary criticism. As a faculty member at Kenyon College, he was the first editor of the widely regarded Kenyon Review. Highly respected as a teacher and mentor to a generation of accomplished students, he also was a prize-winning poet and essayist.

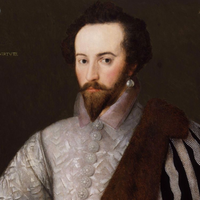

Sir Walter Ralegh (or Raleigh), British explorer, poet and historian, was born probably in 1552, though the date is not quite certain. His father, Walter Ralegh of Fardell, in the parish of Cornwood, near Plymouth, was a country gentleman of old family, but of reduced estate. Walter Ralegh the elder was three times married. His famous son was the child of his third marriage with Catherine, daughter of Sir Philip Champernown of Modbury, and widow of Otho Gilbert of Compton. By her first marriage she had three sons, John, Humphrey and Adrian Gilbert.

George William Russell (10 April 1867– 17 July 1935) who wrote with the pseudonym Æ (sometimes written AE or A.E.), was an Irish writer, editor, critic, poet, artistic painter and Irish nationalist. He was also a writer on mysticism, and a central personage in the group of devotees of theosophy which met in Dublin for many years.

My name is Amber, I have three beautiful children who never seize to inspire me . I have been writing poetry from the age of 14 until now , and I consider it to be a tremendous release . I recently joined "The Greater Cleveland's Writer's Group" , I look forward to gaining as much insight and inspiration as I can from fellow writers My oldest daughter (Tabitha) is deaf , Through her I have learned so much , I went to College to obtain an Associates degree in American Sign Language, which I am fluent in , something I thought I would never be able to do , through my daughter , I have learned there are no limitations on what we can accomplish as an individual or together , the only limitations are the ones we set for ourselves , and fear will only hold you back , "It only takes 20 seconds of courage and I promise ,something great will happen"- We bought A Zoo (one of our favorite movies) .

Mary Robinson (née Darby) (27 November 1757? – 26 December 1800) was an English actress, poet, dramatist, novelist, and celebrity figure. During her lifetime she was known as "the English Sappho".[1][2] She earned her nickname "Perdita" for her role as Perdita (heroine of Shakespeare's The Winter's Tale) in 1779. She was the first public mistress of King George IV while he was still Prince of Wales. Biography Early life Robinson was born in Bristol, England to John Darby, a naval captain, and his wife Hester (née Seys). In her memoirs, Robinson gives her birth in 1758 but the year 1757 seems more likely according to recently published research (see appendix to Byrne, 2005). Her father deserted her mother and took on a mistress when Robinson was still a child. The family hoped for a reconciliation, but Captain Darby made it clear that this was not going to happen. Without the support of her husband, Hester Darby supported herself and the five children born of the marriage by starting a school for young girls in Little Chelsea, London, (where Robinson taught by her 14th birthday). However, during one of his brief returns to the family, Captain Darby had the school closed (which he was entitled to do by English law). Robinson, who at one point attended a school run by the social reformer Hannah More, came to the attention of actor David Garrick. Marriage Hester Darby encouraged her daughter to accept the proposal of an articled clerk, Thomas Robinson, who claimed to have an inheritance. Mary was against this idea; however, after being stricken ill, and watching him take care of her and her younger brother, she felt that she owed him, and she did not want to disappoint her mother who was pushing for the engagement. After the early marriage, Robinson discovered that her husband did not have an inheritance. He continued to live an elaborate lifestyle, however, and had multiple affairs that he made no effort to hide. Subsequently, Mary supported their family. After her husband squandered their money, the couple fled to Wales (where Robinson’s only daughter, Mary Elizabeth, was born in November). Her husband was imprisoned for debt in the Fleet Prison where she accompanied him for many months. During this time, Mary Robinson found a patron in Georgiana Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire, who sponsored the publication of Robinson’s first volume of poems, Captivity. Theatre After her husband obtained his release from prison, Robinson decided to return to the theatre. She launched her acting career and took to the stage, playing Juliet, at Drury Lane Theatre in December 1776. Robinson was best known for her facility with the 'breeches parts’, her performances as Viola in William Shakespeare’sTwelfth Night and Rosalind in As You Like It won her extensive praise. But she gained popularity with playing in Florizel and Perdita, an adaptation of Shakespeare, with the role of Perdita (heroine of The Winter’s Tale) in 1779. It was during this performance that she attracted the notice of the young Prince of Wales, later King George IV of the United Kingdom. He offered her twenty thousand pounds to become his mistress. With her new social prominence, Robinson became a trend-setter in London, introducing a loose, flowing muslin style of gown based upon Grecian statuary that became known as the Perdita. It took Robinson a considerable amount of time to decide to leave her husband for the Prince, as she did not want to be seen by the public as that type of woman. Throughout much of her life she struggled to live in the public eye and also to stay true to the values in which she believed. She eventually gave in to her desires to be with a man whom she thought would treat her better than Mr. Robinson. However, the Prince ended the affair in 1781, refusing to pay the promised sum. “Perdita” Robinson was left to support herself through an annuity promised by the Crown (but rarely paid), in return for some letters written by the Prince, and through her writings. Later life and death Mary Robinson, who now lived separately from her husband, went on to have several love affairs, most notably with Banastre Tarleton, a soldier who had recently distinguished himself fighting in the American War of Independence. Their relationship survived for the next 15 years, through Tarleton’s rise in military rank and his concomitant political successes, through Mary’s own various illnesses, through financial vicissitudes and the efforts of Tarleton’s own family to end the relationship. They had no children, although Robinson had a miscarriage. However, in the end, Tarleton married Susan Bertie, an heiress and an illegitimate daughter of the young 4th Duke of Ancaster, and niece of his sisters Lady Willoughby de Eresby and Lady Cholmondeley. In 1783, Robinson suffered a mysterious illness that left her partially paralysed. Biographer Paula Byrne speculates that a streptococcal infection resulting from a miscarriage led to a severe rheumatic fever that left her disabled for the rest of her life. From the late 1780s, Robinson became distinguished for her poetry and was called “the English Sappho”. In addition to poems, she wrote eight novels, three plays, feminist treatises, and an autobiographical manuscript that was incomplete at the time of her death. Like her contemporary Mary Wollstonecraft, she championed the rights of women and was an ardent supporter of the French Revolution. She died in late 1800 in poverty at the age of 43, having survived several years of ill health, and was survived by her daughter, who was also a published novelist. Literature After years of scholarly neglect, Robinson’s literary afterlife continues apace. While most of the early literature written about Robinson focused on her sexuality, emphasizing her affairs and fashions, she began to receive the attention of feminists and literary scholars in the 1990s. In addition to regaining literary and cultural notability, she has re-attained a degree of celebrity in recent years when several biographies of her appeared, including one by Paula Byrne entitled Perdita: The Literary, Theatrical, and Scandalous Life of Mary Robinson that became a top-ten best-seller after being selected for the Richard & Judy Book Club. Poetry Poems (1775) Captivity, A Poem and Celadon and Lydia, a Tale (1777) Poems (Vol. 1, 1791 / Vol. 2, 1793) London’s Summer Morning (1795) Sappho and Phaon: In a Series of Legitimate Sonnets (1796) Lyrical Tales (1800) Novels Vancenza; or, The Dangers of Credulity (1792) The Widow; or, A Picture of Modern Times (1794) Angelina; A Novel (1796) Hubert de Sevrac, A Romance, of the Eighteenth Century (1796) Walsingham: or, The Pupil of Nature, A Domestic Story (1797) The False Friend; A Domestic Story (1799) The Natural Daughter. With Portraits of the Leadenhead Family. A Novel (1799) Jasper, A Fragment [published posthumously in Memoirs of the Late Mrs. Robinson, Written by Herself (1801)] Dramas The Lucky Escape, A Comic Opera (Drury Lane, 1778) Nobody: A Comedy in Two Acts (Drury Lane, 1794) The Sicilian Lover: A Tragedy in Five Acts (never performed) Socio-political texts Impartial Reflections of the Present Situation of the Queen of France (1791) A Letter to the Women of England, on the Injustice of Mental Subordination (1799) Memoir Robinson, Mary [and Maria Elizabeth Robinson]. Memoirs of the Late Mrs. Robinson, Written by Herself. With Some Posthumous Pieces. 4 vols. London, 1801. Biographies of Robinson Byrne, Paula. Perdita: The Literary, Theatrical, and Scandalous Life of Mary Robinson. New York: Random House, 2004. Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). “Robinson, Mary”. Encyclopædia Britannica 23 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. Davenport, Hester. The Prince’s Mistress: Perdita, a Life of Mary Robinson. Stroud: Sutton Publishing, 2004. Gristwood, Sarah. Perdita: Royal Mistress, Writer, Romantic. London: Bantam, 2005. Memoirs of Mary Robinson 1895. Knight, John Joseph (1897). “Robinson, Mary”. In Lee, Sidney. Dictionary of National Biography 49. London: Smith, Elder & Co. Ledoux, Ellen Malenas. “Florizel and Perdita Affair, 1779–80.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. 2 June 2013. Robinson, Mary [and Maria Elizabeth Robinson]. Memoirs of the Late Mrs. Robinson, Written by Herself. With Some Posthumous Pieces. 4 vols. London, 1801. Levy, Martin J. "Robinson, Mary [Perdita] (1756/1758?–1800)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/23857. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) Resources on Robinson and her literature Brewer, William D., ed. The Works of Mary Robinson. 8 vols. Pickering & Chatto, 2009–2010. Gamer, Michael, and Terry F. Robinson. “Mary Robinson and the Dramatic Art of the Comeback.” Studies in Romanticism 48.2 (Summer 2009): 219–256. Pascoe, Judith. Mary Robinson: Selected Poems. Peterborough, ON: Broadview Press, 1999. Robinson, Daniel. The Poetry of Mary Robinson: Form and Fame. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011. Robinson, Terry F. “Introduction.” Nobody. By Mary Robinson. Romantic Circles. Web. March 2013. Fictional works about Robinson Elyot, Amanda. All For Love: The Scandalous Life and Times of Royal Mistress Mary Robinson. A Novel. 2008. Lightfoot, Freda. Lady of Passion: The Story of Mary Robinson. 2013. Plaidy, Jean. Perdita’s Prince. 1969.

Lola Ridge, born Rose Emily Ridge (12 December 1873 Dublin—19 May 1941 Brooklyn) was an Irish-American anarchist poet and an influential editor of avant-garde, feminist, and Marxist publications. She is best remembered for her long poems and poetic sequences, published in numerous magazines and collected in five books of poetry. Along with other political poets of the early Modernist period, Ridge has received renewed critical attention since the beginning of the 21st century and is praised for making poetry directly from harsh urban life. A new selection of her poetry was published in 2007 and a biography in 2016.

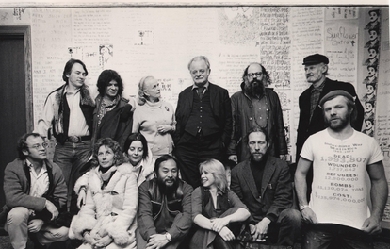

Kenneth Charles Marion Rexroth (December 22, 1905– June 6, 1982) was an American poet, translator and critical essayist. He is regarded as a central figure in the San Francisco Renaissance, and paved the groundwork for the movement. Although he did not consider himself to be a Beat poet, and disliked the association, he was dubbed the “Father of the Beats” by Time Magazine. He was among the first poets in the United States to explore traditional Japanese poetic forms such as haiku. He was also a prolific reader of Chinese literature.

Theodore Goodridge Roberts (July 7, 1877– February 24, 1953) was a Canadian novelist and poet. He was the author of thirty-four novels and over one hundred published stories and poems. He was the brother of poet Charles G.D. Roberts, and the father of painter Goodridge Roberts. Life He was born George Edwards Theodore Goodridge Roberts in Fredericton, to Emma Wetmore Bliss and Anglican Rev. George Goodridge Roberts. The poet Charles G.D. Roberts, and the writers William Carman Roberts and Jane Roberts MacDonald, were his siblings. He published his first poem in 1899, when he was eleven, in the New York Independent (where his cousin Bliss Carman was working), and his first prose piece (a comparison of the Battle of Waterloo and the Battle of Gettysburg) in the Century two years later. Roberts attended Fredericton Collegiate School, though (since school records were lost in a fire) the exact years are unknown. He later went to University of New Brunswick (UNB), but left without graduating. He published poetry in UNB’s University Magazine. In 1897 he moved to New York City, living with his brothers Charles and William and working at The Independent. In 1898 the magazine sent him to Cuba, as a special correspondent, to cover the Spanish–American War. While on the island he contracted malaria—he was sent back to New York and consulted specialists, who sent him back to Fredericton “to die.” An unnamed surgeon saved Roberts’s life, and he was nursed back to heath by Frances Seymour Allen (whom he would subsequently marry). The next year he travelled to Newfoundland, where he helped to found and edit The Newfoundland Magazine. He published his first book of poetry (Northand Lyrics, an anthology edited by Charles G.D. Roberts and featuring his three siblings) in 1899, and his first novel, The House of Isstens, in 1900. In 1901 Roberts sailed on a barkentine to Brazil. In 1902 he returned to Fredericton and briefly edited a second magazine, The Kit-Bag. Roberts married Frances Seymour Allen in November 1903, and they had a two-year honeymoon in Barbados where their first child was born. They would have four children: William Goodridge, Dorothy Mary Gostwick, Theodora Frances Bliss and Loveday (who died as an infant). Roberts averaged three novels a year from 1908 until 1914. At that time his “many novels of adventure and romance” already enoyed a “wide popularity in English-speaking lands.” A former militiaman, Roberts re-enlisted in 1914 when World War I broke out, serving as a lieutenant in the 12th Canadian Infantry Battalion, commanded by Lt.-Col. Harry Fulton McLeod of Fredericton—Roberts’ entire family followed him to England. When the 12th Battalion was assigned to a reserve and training roll in early 1915, Roberts was transferred to a position perhaps better fitted to his combination of military knowledge and literary skill. "In the summer of 1915, he was transferred to the Canadian War Records Office at the request of Max Aitken, Lord Beaverbrook. Roberts wrote official reports and battlefield accounts and published three works in collaboration with others." He was promoted captain early in 1916. When Roberts was in Europe he left his manuscripts and papers, including work not yet published, with a Dr. Wainwright in Saint John, who stored them in his basement. They were destroyed in the spring of 1919 when the Saint John River flooded. In 1929 Roberts wrote a weekly column for the Saint John Telegraph-Journal, “Under the Sun.” From April through September 1930 he edited another small magazine, Acadie. In 1932 he undertook his last major sea cruise, sailing through the Panama Canal to Vancouver and back. The same year he did a cross-Canada reading tour, which “culminated with festivities in Vancouver.” Roberts moved to Toronto in 1935, and in 1937 briefly edited another magazine, Spotlight. In 1939 he relocated to Aylmer, Quebec, where he briefly founded another magazine, Swizzles. He returned to New Brunswick in 1941, and in 1945 moved to Digby, Nova Scotia, where he would die eight years later. He is buried beside Charles G.D. Roberts and Bliss Carman in Fredericton’s Forest Hill Cemetery. Writing The Dictionary of Literary Biography (DLB) says that T.G. Roberts’s “poetry and fiction, staggering in sheer quantity and variety, show at their best Roberts’s most enduring gifts: in his poetry a love of nature well served by a keen eye for local color and detail, a good ear for clean, clear rhythm and rhyme, and a forceful, uncluttered narrative line; and in fiction a talent for presenting his abiding perception of universal struggles between good and evil either in mythic tales of adventure or in regional stories animated by local settings, customs, and dialects.” Of the poems in his 1926 collection, The Lost Shipmate, The Encyclopedia of Literature commented: "Had this volume appeared forty years earlier it might have won for Theodore a reputation equal to that of his brother Charles or of Bliss Carman. Poems such as ‘The sandbar’ and ‘Magic’ are unmatched in Canadian poetry for a facility and clarity of image suggestive of high-realist painting. However, much of what Roberts wrote has been forgotten with time, or has not stood the tests of time and changing fashion. The Merriest Knight The writing that Roberts is most likely to be recognized for today is The Merriest Knight, his collection of Arthurian tales. This looks like the one book by Roberts currently in print - ironically, considering that it was never published as a book during Roberts’s lifetime. Roberts began to write Arthurian fiction in the 1920s; most of these stories, though, were published in the late 1940s and early 1950s in the fiction magazine Blue Book. Roberts planned to publish them as a collection, but died in 1953 before he could do so. In 2001 Mike Ashley, editor of the Mammoth publishing group, brought them out under his Green Knight imprint. A review for SFSite called the collection’s writing “polished,” “erudite,” and “eminently readable,” but “somewhat tame”: “literature for the afternoon tea and crumpets crowd– in a word 'polite’ Arthurian fiction.” Still, it concluded, “if you’re looking for something a bit more upbeat, some Arthuriana-lite, The Merriest Knight is just the book for you.” Recognition The University of New Brunswick awarded Roberts a Doctorate of literature in 1930. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada in 1934. Publications Fiction * The House of Isstens. Boston: L.C. Page, 1900. * Hemming the Adventurer. Boston: L.C. Page, 1904. * Brothers in Peril: A Story of Old Newfoundland, 1905. Boston: L.C. Page & Company, 1905. * Red Feathers: a story of remarkable adventures when the world was young. Boston: L.C. Page, 1907. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. ISBN 978-0-7710-9227-5 * Captain Love. Boston: L.C. Page & Company, 1908. * Flying Plover: His Stories, Told Him by Squat-by-the-Fire. Boston: L.C. Page, 1909. * A Cavalier of Virginia: a romance. Chicago: M.A. Donohue, 1910. * Comrades of the Trails. Boston: L.C. Page & Company, 1910. * Love on a Smokey River. 1911. * A Captain of Raleigh’s: a romance. Boston: L.C. Page & Company, 1911. * A Soldier of Valley Forge. with Robert Neilson Stephens. Boston: L.C. Page, 1911. * Blessington’s Folly. London: John Long, 1912. * Rayton: a backwoods mystery. Boston: L.C. Page, 1912. * The Harbor Master. Chicago: M.A. Donohue, 1913. * Two Shall Be Born. New York: Cassell, 1913. * The Wasp. Toronto: Bell & Cockburn, 1914. * The Toll of the Tides. 1914. * In the High Woods. London: John. Long, 1916. * Forest Fugitives. Toronto: McClelland, Goodchild & Stewart, 1917. * The Islands of Adventure. London; Toronto: Hodder and Stoughton, 1918. * Jess of the River. London: John Long, 1918. * The Exiled Lover. London: John Long, 1919. * Honest Fool. New York: F.A. Munsey, 1925. * The Master of the Moosehorn and Other Backwoods Stories. London; Toronto: Hodder and Stoughton, 1919. * Moonshine. London: Hodder and Stoughton, [1920?]. * The Lure of Piper’s Glen. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Page, 1921. * The Fighting Starkleys. George Varian illus. Boston: Page, 1922. * Musket House. 1922. * Tom Akerley: his adventures in the tall timber and at Gaspard’s clearing on the Indian River. Boston: L.C. Page, 1923. * Green Timber Thoroughbreds. New York: Garden City, 1924. * The Stranger from Up-Along. Garden City, NJ: Doubleday, Page & co., 1924. * The Red Pirogue: a tale of adventure in the Canadian wilds. Boston: L.C. Page, 1924. * The Oxford Wizard. Garden City, NY: Garden City Pub., 1924. * The Lost Shipmate. Toronto: Ryerson, 1926. * The Golden Highlanders. Boston: L.C. Page, 1929. * The Merriest Knight: The Collected Arthurian Tales of Theodore Goodridge Roberts. Mike Ashley ed. Green Knight, 2001. ISBN 978-1-928999-18-8 Non-fiction * Patrols and Trench Raids. 1916. * Battalion Histories. 1918. * Thirty Canadian V.Cs 23rd April 1915 to 30th March 1918, with Robin Richards and Stuart Martin. London: Skeffington, 1918. * Loyalists: a compilation of histories, biographies and genealogies of United empire loyalists and their descendants. Toronto: T. Goodridge Roberts, 1937. Poetry * Northland Lyrics, William Carman Roberts, Theodore Roberts & Elizabeth Roberts Macdonald; selected and arranged with a prologue by Charles G.D. Roberts and an epilogue by Bliss Carman. Boston: Small, Maynard & Co., 1899. ISBN 0-665-12501-1 * Seven Poems. private, 1925. chapbook. * The Lost Shipmate. Toronto: Ryerson Chapbook, 1926. * The Leather Bottle. Toronto: Ryerson, 1934. * That Far River: Selected Poems of Theodore Goodridge Roberts. Martin Ware, ed. London, ON: Canadian Poetry Press, 1998. * Except where noted, bibliographical information courtesy St. Thomas University. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theodore_Goodridge_Roberts