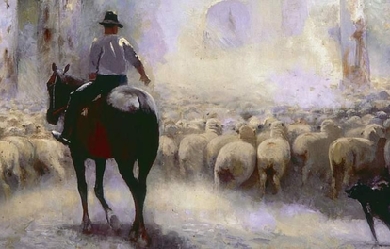

Info

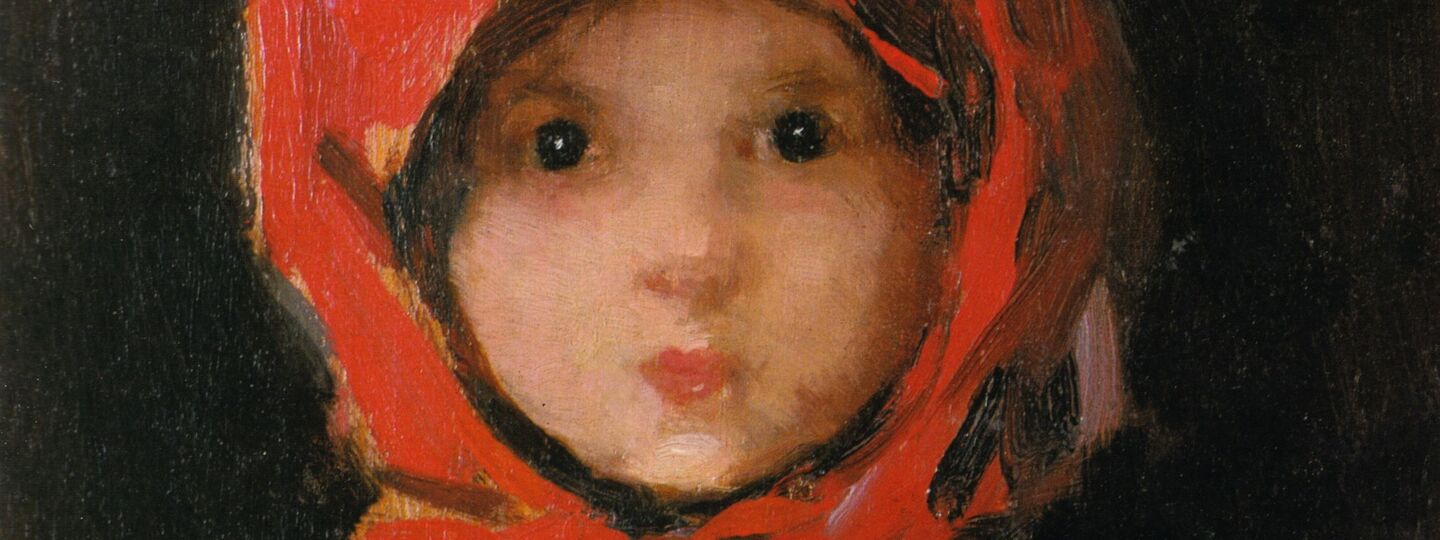

Portrait of a little girl

Nicolae Grigorescu

second half of the 19th century

National Museum of Art of Romania

Lisel Mueller was born in Hamburg, Germany, on February 8, 1924 and immigrated to America at the age of 15. She won the U.S. National Book Award in 1981 and the Pulitzer Prize in 1997. Her poems are extremely accessible, yet intricate and layered. While at times whimsical and possessing a sly humor, there is an underlying sadness in much of her work.

I used to keep my feelings bottled up until I started to write You shouldn't feel alone when you're always around people right? But I always do and I really don't know why Letting it out in poems feels better than to cry One day I was in my room and I knew no one would understand me So I grabbed a pen and paper and I felt free I started to jot down what I was feeling All the pain started healing

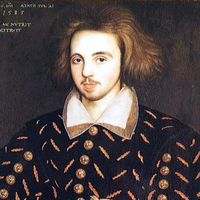

Christopher Marlowe, also known as Kit Marlowe (baptised 26 February 1564– 30 May 1593), was an English playwright, poet and translator of the Elizabethan era. Marlowe was the foremost Elizabethan tragedian of his day. He greatly influenced William Shakespeare, who was born in the same year as Marlowe and who rose to become the pre-eminent Elizabethan playwright after Marlowe’s mysterious early death. Marlowe’s plays are known for the use of blank verse and their overreaching protagonists. A warrant was issued for Marlowe’s arrest on 18 May 1593. No reason was given for it, though it was thought to be connected to allegations of blasphemy—a manuscript believed to have been written by Marlowe was said to contain “vile heretical conceipts”. On 20 May, he was brought to the court to attend upon the Privy Council for questioning. There is no record of their having met that day, however, and he was commanded to attend upon them each day thereafter until “licensed to the contrary”. Ten days later, he was stabbed to death by Ingram Frizer. Whether the stabbing was connected to his arrest has never been resolved. Early life Marlowe was born in Canterbury to shoemaker John Marlowe and his wife Catherine. His date of birth is not known, but he was baptised on 26 February 1564, and is likely to have been born a few days before. Thus, he was just two months older than his contemporary William Shakespeare, who was baptised on 26 April 1564 in Stratford-upon-Avon. Marlowe attended The King’s School in Canterbury (where a house is now named after him) and Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, where he studied on a scholarship and received his Bachelor of Arts degree in 1584. In 1587, the university hesitated to award him his Master of Arts degree because of a rumour that he intended to go to the English college at Rheims, presumably to prepare for ordination as a Roman Catholic priest. However, his degree was awarded on schedule when the Privy Council intervened on his behalf, commending him for his “faithful dealing” and “good service” to the Queen. The nature of Marlowe’s service was not specified by the Council, but its letter to the Cambridge authorities has provoked much speculation, notably the theory that Marlowe was operating as a secret agent working for Sir Francis Walsingham’s intelligence service. No direct evidence supports this theory, although the Council’s letter is evidence that Marlowe had served the government in some secret capacity. Literary career Of the dramas attributed to Marlowe, Dido, Queen of Carthage is believed to have been his first. It was performed by the Children of the Chapel, a company of boy actors, between 1587 and 1593. The play was first published in 1594; the title page attributes the play to Marlowe and Thomas Nashe. Marlowe’s first play performed on the regular stage in London, in 1587, was Tamburlaine the Great, about the conqueror Timur (Tamerlane), who rises from shepherd to warlord. It is among the first English plays in blank verse, and, with Thomas Kyd’s The Spanish Tragedy, generally is considered the beginning of the mature phase of the Elizabethan theatre. Tamburlaine was a success, and was followed with Tamburlaine the Great, Part II. The two parts of Tamburlaine were published in 1590; all Marlowe’s other works were published posthumously. The sequence of the writing of his other four plays is unknown; all deal with controversial themes. * The Jew of Malta (first published as The Famous Tragedy of the Rich Jew of Malta), about a Maltese Jew’s barbarous revenge against the city authorities, has a prologue delivered by a character representing Machiavelli. It was probably written in 1589 or 1590, and was first performed in 1592. It was a success, and remained popular for the next fifty years. The play was entered in the Stationers’ Register on 17 May 1594, but the earliest surviving printed edition is from 1633. * Edward the Second is an English history play about the deposition of King Edward II by his barons and the Queen, who resent the undue influence the king’s favourites have in court and state affairs. The play was entered into the Stationers’ Register on 6 July 1593, five weeks after Marlowe’s death. The full title of the earliest extant edition, of 1594, is The troublesome reigne and lamentable death of Edward the second, King of England, with the tragicall fall of proud Mortimer. * The Massacre at Paris is a short and luridly written work, the only surviving text of which was probably a reconstruction from memory of the original performance text, portraying the events of the Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre in 1572, which English Protestants invoked as the blackest example of Catholic treachery. It features the silent “English Agent”, whom subsequent tradition has identified with Marlowe himself and his connections to the secret service. The Massacre at Paris is considered his most dangerous play, as agitators in London seized on its theme to advocate the murders of refugees from the low countries and, indeed, it warns Elizabeth I of this possibility in its last scene. Its full title was The Massacre at Paris: With the Death of the Duke of Guise. * Doctor Faustus (or The Tragical History of the Life and Death of Doctor Faustus), based on the German Faustbuch, was the first dramatised version of the Faust legend of a scholar’s dealing with the devil. While versions of “The Devil’s Pact” can be traced back to the 4th century, Marlowe deviates significantly by having his hero unable to “burn his books” or repent to a merciful God in order to have his contract annulled at the end of the play. Marlowe’s protagonist is instead carried off by demons, and in the 1616 quarto his mangled corpse is found by several scholars. Doctor Faustus is a textual problem for scholars as two versions of the play exist: the 1604 quarto, also known as the A text, and the 1616 quarto or B text. Both were published after Marlowe’s death. Scholars have disagreed which text is more representative of Marlowe’s original, and some editions are based on a combination of the two. The latest scholarly consensus (as of the late 20th century) holds the A text is more representative because it contains irregular character names and idiosyncratic spelling, which are believed to reflect a text based on the author’s handwritten manuscript, or “foul papers.” The B text, in comparison, was highly edited, censored because of shifting theater laws regarding religious words onstage, and contains several additional scenes which scholars believe to be the additions of other playwrights, particularly Samuel Rowley and William Bird (alias Borne). Marlowe’s plays were enormously successful, thanks in part, no doubt, to the imposing stage presence of Edward Alleyn. Alleyn was unusually tall for the time, and the haughty roles of Tamburlaine, Faustus, and Barabas were probably written especially for him. Marlowe’s plays were the foundation of the repertoire of Alleyn’s company, the Admiral’s Men, throughout the 1590s. Marlowe also wrote the poem Hero and Leander (published in 1598, and with a continuation by George Chapman the same year), the popular lyric “The Passionate Shepherd to His Love”, and translations of Ovid’s Amores and the first book of Lucan’s Pharsalia. In 1599, his translation of Ovid was banned and copies publicly burned as part of Archbishop Whitgift’s crackdown on offensive material. Marlowe has been credited in the New Oxford Shakespeare series as co-author of the three Henry VI plays. Legend As with other writers of the period, little is known about Marlowe. What evidence there is can be found in legal records and other official documents. This has not stopped writers of both fiction and non-fiction from speculating about his activities and character. Marlowe has often been described as a spy, a brawler, and a heretic, as well as a “magician”, “duellist”, “tobacco-user”, “counterfeiter”, and “rakehell”. J. A. Downie and Constance Kuriyama have argued against the more lurid speculation, but J. B. Steane remarked, “it seems absurd to dismiss all of these Elizabethan rumours and accusations as 'the Marlowe myth’”. Spying Marlowe is alleged to have been a government spy (Park Honan’s 2005 biography even had “Spy” in its title). The author Charles Nicholl speculates this was the case and suggests that Marlowe’s recruitment took place when he was at Cambridge. As noted above, in 1587 the Privy Council ordered the University of Cambridge to award Marlowe his degree of Master of Arts, denying rumours that he intended to go to the English Catholic college in Rheims, saying instead that he had been engaged in unspecified “affaires” on “matters touching the benefit of his country”. Surviving college records from the period also indicate that Marlowe had had a series of unusually lengthy absences from the university– much longer than permitted by university regulations– that began in the academic year 1584–1585. Surviving college buttery (provisions store) accounts indicate he began spending lavishly on food and drink during the periods he was in attendance– more than he could have afforded on his known scholarship income. It has sometimes been theorised that Marlowe was the “Morley” who was tutor to Arbella Stuart in 1589. This possibility was first raised in a TLS letter by E. St John Brooks in 1937; in a letter to Notes and Queries, John Baker has added that only Marlowe could be Arbella’s tutor due to the absence of any other known “Morley” from the period with an MA and not otherwise occupied. If Marlowe was Arbella’s tutor (and some biographers think that the “Morley” in question may have been a brother of the musician Thomas Morley), it might indicate that he was there as a spy, since Arbella, niece of Mary, Queen of Scots, and cousin of James VI of Scotland, later James I of England, was at the time a strong candidate for the succession to Elizabeth’s throne. Frederick S. Boas dismisses the possibility of this identification, based on surviving legal records which document his "residence in London between September and December 1589". Marlowe had been party to a fatal quarrel involving his neighbours and the poet Thomas Watson in Norton Folgate, and was held in Newgate Prison for a fortnight. In fact the quarrel and his arrest was on 18 September, he was released on bail on 1 October, and he had to attend court– where he was cleared of any wrongdoing– on 3 December, but there is no record of where he was for the intervening two months. In 1592 Marlowe was arrested in the town of Flushing (Vlissingen) (then an English garrison town) in the Netherlands for his alleged involvement in the counterfeiting of coins, presumably related to the activities of seditious Catholics. He was sent to be dealt with by the Lord Treasurer (Burghley) but no charge or imprisonment resulted. This arrest may have disrupted another of Marlowe’s spying missions, perhaps by giving the resulting coinage to the Catholic cause. He was to infiltrate the followers of the active Catholic plotter William Stanley and report back to Burghley. Arrest and death In early May 1593 several bills were posted about London threatening Protestant refugees from France and the Netherlands who had settled in the city. One of these, the “Dutch church libel”, written in rhymed iambic pentameter, contained allusions to several of Marlowe’s plays and was signed, “Tamburlaine”. On 11 May the Privy Council ordered the arrest of those responsible for the libels. The next day, Marlowe’s colleague Thomas Kyd was arrested. Kyd’s lodgings were searched and a 3-page fragment of a heretical tract was found. In a letter to Sir John Puckering, Kyd asserted that it had belonged to Marlowe, with whom he had been writing “in one chamber” some two years earlier. In a second letter, Kyd described Marlowe as blasphemous, disorderly, holding treasonous opinions, being an irreligious reprobate, and ‘intemperate & of a cruel hart’. At that time they had both been working for an aristocratic patron, probably Ferdinando Stanley, Lord Strange. A warrant for Marlowe’s arrest was issued on 18 May, when the Privy Council apparently knew that he might be found staying with Thomas Walsingham, whose father was a first cousin of the late Sir Francis Walsingham, Elizabeth’s principal secretary in the 1580s and a man more deeply involved in state espionage than any other member of the Privy Council. Marlowe duly presented himself on 20 May but, there apparently being no Privy Council meeting on that day, was instructed to “give his daily attendance on their Lordships, until he shall be licensed to the contrary”. On Wednesday, 30 May, Marlowe was killed. Various accounts of Marlowe’s death were current over the next few years. In his Palladis Tamia, published in 1598, Francis Meres says Marlowe was “stabbed to death by a bawdy serving-man, a rival of his in his lewd love” as punishment for his “epicurism and atheism.” In 1917, in the Dictionary of National Biography, Sir Sidney Lee wrote that Marlowe was killed in a drunken fight, and this is still often stated as fact today. The official account came to light only in 1925 when the scholar Leslie Hotson discovered the coroner’s report of the inquest on Marlowe’s death, held two days later on Friday 1 June 1593, by the Coroner of the Queen’s Household, William Danby. Marlowe had spent all day in a house in Deptford, owned by the widow Eleanor Bull, and together with three men: Ingram Frizer, Nicholas Skeres and Robert Poley. All three had been employed by one or other of the Walsinghams. Skeres and Poley had helped snare the conspirators in the Babington plot and Frizer would later describe Thomas Walsingham as his “master” at that time although his role was probably more that of a financial or business agent as he was for Walsingham’s wife Audrey a few years later. These witnesses testified that Frizer and Marlowe had argued over payment of the bill (now famously known as the 'Reckoning’) exchanging “divers malicious words” while Frizer was sitting at a table between the other two and Marlowe was lying behind him on a couch. Marlowe snatched Frizer’s dagger and wounded him on the head. In the ensuing struggle, according to the coroner’s report, Marlowe was stabbed above the right eye, killing him instantly. The jury concluded that Frizer acted in self-defence, and within a month he was pardoned. Marlowe was buried in an unmarked grave in the churchyard of St. Nicholas, Deptford immediately after the inquest, on 1 June 1593. The complete text of the inquest report was published by Leslie Hotson in his book, The Death of Christopher Marlowe, in the introduction to which Prof. G. L. Kittredge said “The mystery of Marlowe’s death, heretofore involved in a cloud of contradictory gossip and irresponsible guess-work, is now cleared up for good and all on the authority of public records of complete authenticity and gratifying fullness”, but this confidence proved fairly short-lived. Hotson himself had considered the possibility that the witnesses had “concocted a lying account of Marlowe’s behaviour, to which they swore at the inquest, and with which they deceived the jury” but came down against that scenario. Others, however, began to suspect that this was indeed the case. Writing to the Times Literary Supplement shortly after the book’s publication, Eugénie de Kalb disputed that the struggle and outcome as described were even possible, and Samuel A. Tannenbaum (a graduate of the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons) insisted the following year that such a wound could not have possibly resulted in instant death, as had been claimed. Even Marlowe’s biographer John Bakeless acknowledged that “some scholars have been inclined to question the truthfulness of the coroner’s report. There is something queer about the whole episode” and said that Hotson’s discovery “raises almost as many questions as it answers.” It has also been discovered more recently that the apparent absence of a local county coroner to accompany the Coroner of the Queen’s Household would, if noticed, have made the inquest null and void. One of the main reasons for doubting the truth of the inquest concerns the reliability of Marlowe’s companions as witnesses. As an agent provocateur for the late Sir Francis Walsingham, Robert Poley was a consummate liar, the “very genius of the Elizabethan underworld”, and is even on record as saying “I will swear and forswear myself, rather than I will accuse myself to do me any harm.” The other witness, Nicholas Skeres, had for many years acted as a confidence trickster, drawing young men into the clutches of people in the money-lending racket, including Marlowe’s apparent killer, Ingram Frizer, with whom he was currently engaged in just such a swindle. In other words, despite their being referred to as “generosi” (gentlemen) in the inquest report, they were all professional liars. Some biographers, such as Kuriyama and Downie, nevertheless take the inquest to be a true account of what occurred, but in trying to explain what really happened if the account was not true, others have come up with a variety of murder theories. Jealous of her husband Thomas’s relationship with Marlowe, Audrey Walsingham arranged for the playwright to be murdered. Sir Walter Raleigh arranged the murder, fearing that under torture Marlowe might incriminate him. With Skeres the main player, the murder resulted from attempts by the Earl of Essex to use Marlowe to incriminate Sir Walter Raleigh. He was killed on the orders of father and son Lord Burghley and Sir Robert Cecil, who thought that his plays contained Catholic propaganda. He was accidentally killed while Frizer and Skeres were pressuring him to pay back money he owed them. Marlowe was murdered at the behest of several members of the Privy Council who feared that he might reveal them to be atheists. The Queen herself ordered his assassination because of his subversively atheistic behaviour. Frizer murdered him because he envied Marlowe’s close relationship with his master Thomas Walsingham and feared the effect that Marlowe’s behaviour might have on Walsingham’s reputation. There is even a theory that Marlowe’s death was faked to save him from trial and execution for subversive atheism. However, since there are only written documents on which to base any conclusions, and since it is probable that the most crucial information about his death was never committed to writing at all, it is unlikely that the full circumstances of Marlowe’s death will ever be known. Philosophy During his lifetime, Marlowe was reputed to be an atheist which, at that time, held the dangerous implication of being an enemy of God and, by association, the state. With the rise of public fears concerning The School of Night, or “School of Atheism” in the late 16th century, accusations of atheism were closely associated with disloyalty to the Protestant monarchy of England. Some modern historians consider that Marlowe’s professed atheism, as with his supposed Catholicism, may have been no more than an elaborate and sustained pretense adopted to further his work as a government spy. Contemporary evidence comes from Marlowe’s accuser in Flushing, an informer called Richard Baines. The governor of Flushing had reported that each of the men had “of malice” accused the other of instigating the counterfeiting, and of intending to go over to the Catholic “enemy”; such an action was considered atheistic by the Church of England. Following Marlowe’s arrest in 1593, Baines submitted to the authorities a “note containing the opinion of one Christopher Marly concerning his damnable judgment of religion, and scorn of God’s word.” Baines attributes to Marlowe a total of eighteen items which “scoff at the pretensions of the Old and New Testament” such as, "Christ was a bastard and his mother dishonest [unchaste]", “the woman of Samaria and her sister were whores and that Christ knew them dishonestly”, and, “St John the Evangelist was bedfellow to Christ and leaned always in his bosom” (cf. John 13:23–25), and, “that he used him as the sinners of Sodom”. He also implies that Marlowe had Catholic sympathies. Other passages are merely skeptical in tone: “he persuades men to atheism, willing them not to be afraid of bugbears and hobgoblins”. The final paragraph of Baines’s document reads: These thinges, with many other shall by good & honest witnes be aproved to be his opinions and Comon Speeches, and that this Marlowe doth not only hould them himself, but almost into every Company he Cometh he persuades men to Atheism willing them not to be afeard of bugbeares and hobgoblins, and vtterly scorning both god and his ministers as I Richard Baines will Justify & approue both by mine oth and the testimony of many honest men, and almost al men with whome he hath Conversed any time will testify the same, and as I think all men in Cristianity ought to indevor that the mouth of so dangerous a member may be stopped, he saith likewise that he hath quoted a number of Contrarieties oute of the Scripture which he hath giuen to some great men who in Convenient time shalbe named. When these thinges shalbe Called in question the witnes shalbe produced. Similar examples of Marlowe’s statements were given by Thomas Kyd after his imprisonment and possible torture (see above); both Kyd and Baines connect Marlowe with the mathematician Thomas Harriot and Sir Walter Raleigh’s circle. Another document claimed at around the same time that “one Marlowe is able to show more sound reasons for Atheism than any divine in England is able to give to prove divinity, and that... he hath read the Atheist lecture to Sir Walter Raleigh and others.” Some critics believe that Marlowe sought to disseminate these views in his work and that he identified with his rebellious and iconoclastic protagonists. However, plays had to be approved by the Master of the Revels before they could be performed, and the censorship of publications was under the control of the Archbishop of Canterbury. Presumably these authorities did not consider any of Marlowe’s works to be unacceptable other than the Amores. Sexuality Like William Shakespeare, Marlowe is frequently claimed to have been homosexual. Others argue that the question of whether an Elizabethan was gay or homosexual in a modern sense is anachronistic. For the Elizabethans, what is often today termed homosexual or bisexual was more likely to be recognised as a sexual act, rather than an exclusive sexual orientation and identity. Some scholars argue that the evidence is inconclusive and that the reports of Marlowe’s homosexuality may simply be exaggerated rumours produced after his death. Richard Baines reported Marlowe as saying: “All they that love not Tobacco and Boys are fools”. David Bevington and Eric Rasmussen describe Baines’s evidence as “unreliable testimony” and make the comment: “These and other testimonials need to be discounted for their exaggeration and for their having been produced under legal circumstances we would regard as a witch-hunt”. One critic, J.B. Steane, remarked that he considers there to be “no evidence for Marlowe’s homosexuality at all.” Other scholars, however, point to homosexual themes in Marlowe’s writing: in Hero and Leander, Marlowe writes of the male youth Leander, “in his looks were all that men desire” and that when the youth swims to visit Hero at Sestos, the sea god Neptune becomes sexually excited, "[i]magining that Ganymede, displeas’d, [h]ad left the Heavens... [t]he lusty god embrac’d him, call’d him love... He watched his arms and, as they opened wide [a]t every stroke, betwixt them would he slide [a]nd steal a kiss,... And dive into the water, and there pry [u]pon his breast, his thighs, and every limb,... [a]nd talk of love", while the boy, naive and unaware of Greek love practices, protests, “'You are deceiv’d, I am no woman, I.' Thereat smil’d Neptune.” Edward the Second contains the following passage supporting homosexual relationships: Marlowe wrote the only play about the life of Edward II up to his time, taking the humanist literary discussion of male sexuality much further than his contemporaries. The play was extremely bold, dealing with a star-crossed love story between Edward II and Piers Gaveston. Though it was common practice at the time to reveal characters as gay to give audiences reason to suspect them as culprits of a given crime, Christopher Marlowe’s Edward II is portrayed as a sympathetic character. Reputation among contemporary writers Whatever the particular focus of modern critics, biographers and novelists, for his contemporaries in the literary world, Marlowe was above all an admired and influential artist. Within weeks of his death, George Peele remembered him as “Marley, the Muses’ darling”; Michael Drayton noted that he "Had in him those brave translunary things / That the first poets had", and Ben Jonson wrote of “Marlowe’s mighty line”. Thomas Nashe wrote warmly of his friend, “poor deceased Kit Marlowe”. So too did the publisher Edward Blount, in the dedication of Hero and Leander to Sir Thomas Walsingham. Among the few contemporary dramatists to say anything negative about Marlowe was the anonymous author of the Cambridge University play The Return From Parnassus (1598) who wrote, "Pity it is that wit so ill should dwell, / Wit lent from heaven, but vices sent from hell.” The most famous tribute to Marlowe was paid by Shakespeare in As You Like It, where he not only quotes a line from Hero and Leander ("Dead Shepherd, now I find thy saw of might, ‘Who ever loved that loved not at first sight?’") but also gives to the clown Touchstone the words “When a man’s verses cannot be understood, nor a man’s good wit seconded with the forward child, understanding, it strikes a man more dead than a great reckoning in a little room.” This appears to be a reference to Marlowe’s murder which involved a fight over the “reckoning”, the bill, as well as to a line in Marlowe’s Jew of Malta– “Infinite riches in a little room”. Shakespeare was heavily influenced by Marlowe in his work, as can be seen in the re-using of Marlovian themes in Antony and Cleopatra, The Merchant of Venice, Richard II, and Macbeth (Dido, Jew of Malta, Edward II and Doctor Faustus, respectively). In Hamlet, after meeting with the travelling actors, Hamlet requests the Player perform a speech about the Trojan War, which at 2.2.429–32 has an echo of Marlowe’s Dido, Queen of Carthage. In Love’s Labour’s Lost Shakespeare brings on a character “Marcade” (three syllables) in conscious acknowledgement of Marlowe’s character “Mercury”, also attending the King of Navarre, in Massacre at Paris. The significance, to those of Shakespeare’s audience who had read Hero and Leander, was Marlowe’s identification of himself with the god Mercury. As Shakespeare A theory has arisen centered on the notion that Marlowe may have faked his death and then continued to write under the assumed name of William Shakespeare. However, orthodox academic consensus rejects alternative candidates for authorship, including Marlowe. Memorials A Marlowe Memorial in the form of a bronze sculpture of The Muse of Poetry by Edward Onslow Ford was erected by subscription in Buttermarket, Canterbury in 1891. In July 2002, a memorial window to Marlowe– a gift of the Marlowe Society– was unveiled in Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey. Controversially, a question mark was added to the generally accepted date of death. On 25 October 2011 a letter from Paul Edmondson and Stanley Wells was published by The Times newspaper, in which they called on the Dean and Chapter to remove the question mark on the grounds that it “flew in the face of a mass of unimpugnable evidence”. In 2012, they renewed this call in their e-book Shakespeare Bites Back, adding that it “denies history”, and again the following year in their book Shakespeare Beyond Doubt. Fictional works about Marlowe Wilbur G. Zeigler’s novel It was Marlowe (1895) was the first book to argue that Marlowe’s death was faked—apparently in support of Zeigler’s claim that Marlowe was the actual author of Hamlet, which was written after Marlowe’s recorded death. Herbert Lom’s Enter a Spy: The Double Life of Christopher Marlowe (1978), a historical novel. Philip Lindsay’s One Dagger For Two (1932), novel which claims that Marlowe was stabbed in a dispute over a woman. Leo Rost’s Marlowe (1981), was an American rock musical staged on Broadway. Peter Whelan’s play The School of Night (1992), about Marlowe’s links to the freethinking “school of night” and the young Shakespeare, was performed by the Royal Shakespeare Company in Stratford-upon-Avon. Anthony Burgess’s A Dead Man in Deptford (1993), an imaginative treatment of Marlowe’s death, was the last of Burgess’s novels to be published in his lifetime. Marlowe appears in Harry Turtledove’s Ruled Britannia (2002), an alternate history depicting an England where the Spanish Armada was successful in 1588 and imposed the rule of King Philip II of Spain. In this depiction, Marlowe is still alive in 1598 and is active among conspirators seeking to overthrow Spanish rule and restore the imprisoned Queen Elizabeth. This involvement leads to Marlowe being killed, five years later than in actual history, and he does not live to see the success of the rebellion he helped foment. Louise Welsh’s 2004 novel Tamburlaine Must Die about Marlowe’s last days was chosen as a BBC Radio 4 “Book at Bedtime” in April 2006. The 2010 Dr Who audio play Point of Entry starring Colin Baker has Marlowe haunted by a demon seeking an Aztec dagger. Marlowe plays a major role in Elizabeth Bear’s Promethean Age Series (2006-2013), which combines elements of secret history and fantasy. Among other things, in this account Marlowe and Shakespeare had a secret, deeply emotional homosexual love affair and many of Shakespeare’s Sonnets were written to express his love for Marlowe. Also, as depicted in the Promethean Age series, Christopher Marlowe was not assassinated in 1593 as history records but was taken into Faerie where he became the lover of the witch Morgan le Fay. The Christopher Marlowe Mysteries was a 4-episode BBC Radio 4 series, first broadcast in 2007. Michael Butt’s radio play, The Killing, was performed as “Afternoon Drama” on BBC Radio 4 in August 2010. D. Lawrence-Young’s novel Marlowe: “Soul’d to the Devil” (2010) is close to a biography of Marlowe’s life. Ros Barber’s verse novel The Marlowe Papers (2012), in which Marlowe looks back on his past and faked death, was winner of the Desmond Elliott Prize and joint winner of the Authors’ Club First Novel Award for 2013. M. J. Trow’s The Kit Marlowe Series (2011 - ), in which Marlowe is depicted as a detective and spy for Sir Francis Walsingham Ellen Wilson’s novel, In the Shadow of Shakespeare (2013), mixing historical fiction, romance, and science fiction, the heroine, Alice, travels back in time and meets Christopher Marlowe. Marlowe is a character in the 2015 film Bill. Marlowe (played by Jamie Campbell-Bower) is a main character in the 2017 TNT series Will. Michelle Butler Hallett’s This Marlowe (2016) explores the relationship between Kyd and Marlowe, and gives an account of Kyd’s interrogation and the murder of Marlowe. Works (The dates of composition are approximate.) Plays * Dido, Queen of Carthage (c. 1586) (possibly co-written with Thomas Nashe) * Tamburlaine the Great, part 1 (c. 1587), part 2 (c. 1587–1588) * The Jew of Malta (c. 1589) * The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus (c. 1589, or, c. 1593) * Edward II (c. 1592) * The Massacre at Paris (c. 1593) * The play Lust’s Dominion was attributed to Marlowe upon its initial publication in 1657, though scholars and critics have almost unanimously rejected the attribution. Poetry * Translation of Book One of Lucan’s Pharsalia (date unknown) * Translation of Ovid’s Amores (c. 1580s?) * “The Passionate Shepherd to His Love” (pre-1593) * Hero and Leander (c. 1593, unfinished; completed by George Chapman, 1598) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christopher_Marlowe

Hi, this is The wise girl behind the mask, I just want to say I love writing poems. Its fun and actually calms me in some way. So just for heads up when I write, its going to be based off my mood. For example, if I am happy I'll write a happy poem, if I am angry I'll write a angry poem. And I can get very, very angry, so please don't write any bad reviews. I picked The wise girl behind the mask as my name because I am shy. I don't really talk that much but when I do, people are shocked how mature I sound. People say that when I talk, my words are filled with weight and wisdom. Well that explains the wise girl, let me tell you behind the mask girl. When I go out in public I where a mask, I pretend that I'm happy, goofy, and pretend to be a air head. However, I am really smart and don't forget it, I am a straight A and high honor roll student. I hate it when everyone treats me like a child, like a idiot. I am just trying to please my family and friends, but its hard, tiring, humiliating, and I hate it. Though, its not like I have a choice, if my family and friends knew the real me, they will just judge and not listen. I like to write poems, even though I curse sometimes, I only do it to get out my feelings, that they make me feel. Now let me tell you about the real me, I love writing, books, outdoor activities, and parks. I might sound like a stiff, but I can be a bit of a trouble-maker, I love to pull pranks sometimes. I also love music, I can not survive without music. My favorite color is blue, I'm a girl, not telling you my age, but I am young. I hate pink, most ugliest color in the world, I am tall for my age, love animals. My goal is to be a veterinarian in the future. Now that everything is settled, come and read my poems, tell me what you think. Have a jolly day, and good bye for now.

Archibald MacLeish (May 7, 1892– April 20, 1982) was an American poet, writer, and the Librarian of Congress. He is associated with the Modernist school of poetry. He received three Pulitzer Prizes for his work. MacLeish was born in Glencoe, Illinois. His father, Scottish-born Andrew MacLeish, worked as a dry goods merchant. His mother, Martha (née Hillard), was a college professor and had served as president of Rockford College. He grew up on an estate bordering Lake Michigan. He attended the Hotchkiss School from 1907 to 1911 before entering Yale University, where he majored in English, was elected to Phi Beta Kappa, and was selected for the Skull and Bones society. He then enrolled in Harvard Law School, where he served as an editor of the Harvard Law Review. In 1916, he married Ada Hitchcock. His studies were interrupted by World War I, in which he served first as an ambulance driver and later as a captain of artillery. His brother, Kenneth MacLeish was killed in action during the war. He graduated from law school in 1919, taught law for a semester for the government department at Harvard, then worked briefly as an editor for The New Republic. He next spent three years practicing law.

Gerald Massey (29 May 1828 – 29 October 1907) was an English poet and writer on Spiritualism and Ancient Egypt. Early life Massey was born near Tring, Hertfordshire in England to poor parents. When little more than a child, he was made to work hard in a silk factory, which he afterward deserted for the equally laborious occupation of straw plaiting. These early years were rendered gloomy by much distress and deprivation, against which the young man strove with increasing spirit and virility, educating himself in his spare time, and gradually cultivating his innate taste for literary work. He was attracted by the movement known as Christian Socialism, into which he threw himself with whole-hearted vigour, and so became associated with Frederick Denison Maurice and Charles Kingsley. Later life From about 1870 onwards, Massey became increasingly interested in Egyptology and the similarities that exist between ancient Egyptian mythology and the Gospel stories. He studied the extensive Egyptian records housed in the Assyrian and Egyptology section of the British Museum in London where he worked closely with the curator, Dr. Samuel Birch, and other leading Egyptologists of his day, even learning hieroglyphics at the time the Temple of Horus at Edfu was first being excavated. Writing career Massey's first public appearance as a writer was in connection with a journal called the Spirit of Freedom, of which he became editor, and he was only twenty-two when he published his first volume of poems, Voices of Freedom and Lyrics of Love (1850). These he followed in rapid succession with The Ballad of Babe Christabel (1854), War Waits (1855), Havelock's March (1860), and A Tale of Eternity (1869). In 1889, Massey published a two-volume collection of his poems called My Lyrical Life. He also published works dealing with Spiritualism, the study of Shakespeare's sonnets (1872 and 1890), and theological speculation. It is generally understood that he was the original of George Eliot's Felix Holt.[1] Massey's poetry has a certain rough and vigorous element of sincerity and strength which easily accounts for its popularity at the time of its production. He treated the theme of Sir Richard Grenville before Tennyson thought of using it, with much force and vitality. Indeed, Tennyson's own praise of Massey's work is still its best eulogy, for the Laureate found in him a poet of fine lyrical impulse, and of a rich half-Oriental imagination. The inspiration of his poetry is a combination of his vast knowledge based on travels, research and experiences; he was a patriotic humanist to the core. His poem "The Merry, Merry May" was set to music in 1894 by the composer Cyril Rootham and then in a popular song by composer Christabel Baxendale. In regard to Ancient Egypt, Massey first published The Book of the Beginnings, followed by The Natural Genesis. His most prolific work is Ancient Egypt: The Light of the World, published shortly before his death. Massey was a believer in spiritual evolution; he opined that Darwin's theory of evolution was incomplete without spiritualism: The theory contains only one half the explanation of man's origins and needs spiritualism to carry it through and complete it. For while this ascent on the physical side has been progressing through myriads of ages, the Divine descent has also been going on – man being spiritually an incarnation from the Divine as well as a human development from the animal creation. The cause of the development is spiritual. Mr. Darwin's theory does not in the least militate against ours – we think it necessitates it; he simply does not deal with our side of the subject. He can not go lower than the dust of the earth for the matter of life; and for us, the main interest of our origin must lie in the spiritual domain. Assertions about Jesus and Horus One of the more important aspects of Massey's writings were his assertions that there were parallels between Jesus and the Egyptian god Horus, primarily contained in book The Natural Genesis first published in 1883. Massey, for example, argued in the book his belief that: both Horus and Jesus were born of virgins on 25 December, raised men from the dead (Massey speculates that the biblical Lazarus, raised from the dead by Jesus, has a parallel in El-Asar-Us, a title of Osiris), died by crucifixion and were resurrected three days later.[5] These assertions have influenced various later writers such as Alvin Boyd Kuhn, Tom Harpur, Yosef Ben-Jochannan, and Dorothy M. Murdock.[6][7][unreliable source?] Like Godfrey Higgins a half-century earlier, Massey believed that Western religions had mythical roots. The human mind has long suffered an eclipse and been darkened and dwarfed in the shadow of ideas the real meaning of which has been lost to moderns. Myths and allegories whose significance was once unfolded in the Mysteries have been adopted in ignorance and reissued as real truths directly and divinely vouchsafed to humanity for the first and only time! The early religions had their myths interpreted. We have ours misinterpreted. And a great deal of what has been imposed on us as God’s own true and sole revelation to us is a mass of inverted myths. Christian ignorance notwithstanding, the Gnostic Jesus is the Egyptian Horus who was continued by the various sects of gnostics under both the names of Horus and of Jesus. In the gnostic iconography of the Roman Catacombs child-Horus reappears as the mummy-babe who wears the solar disc. The royal Horus is represented in the cloak of royalty, and the phallic emblem found there witnesses to Jesus being Horus of the resurrection. Criticism Christian theologian W. Ward Gasque, a Ph.D. from Harvard and Manchester University, sent emails to twenty Egyptologists that he considered leaders of the field – including Kenneth Kitchen of the University of Liverpool and Ron Leprohan of the University of Toronto – in Canada, the United States, Britain, Australia, Germany and Austria to verify academic support for some of these assertions. His primary targets were Tom Harpur, Alvin Boyd Kuhn and the Christ myth theory, and only indirectly Massey. Ten out of twenty responded, but most were not named. According to Gasque, Massey's work, which draws comparisons between the Judeo-Christian religion and the Egyptian religion, is not considered significant in the field of modern Egyptology and is not mentioned in the Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt or similar reference works of modern Egyptology. Gasque reports that those who responded were unanimous in dismissing the proposed etymologies for Jesus and Christ, and one unspecified Egyptologist referred to Alvin Boyd Kuhn's comparison as "fringe nonsense."[11][unreliable source?] However, Harpur's response to Gasque quotes leading contemporary Egyptologist Erik Hornung that there are parallels between Christianity and ancient Egypt, as do the writings of biblical expert Thomas L. Thompson. Theologian Stanley E. Porter has pointed out that Massey's analogies include a number of errors, for example Massey stated that 25 December as the date of birth of Jesus was selected based on the birth of Horus, but the New Testament does not include any reference to the date or season of the birth of Jesus. The earliest known source recognizing 25 December as the date of birth of Jesus is by Hippolytus of Rome, written around the beginning of the 3rd century, based on the assumption that the conception of Jesus took place at the Spring equinox. Hippolytus placed the equinox on 25 March and then added 9 months to get 25 December, thus establishing the date for festivals. The Roman Chronography of 354 then included an early reference to the celebration of a Nativity feast in December, as of the fourth century. Porter states that Massey's serious historical errors often render his works nonsensical, for example Massey states that the biblical references to Herod the Great were based on the myth of "Herrut" the evil hydra serpent, while the existence of Herod the Great can be well established without reliance on Christian sources. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gerald_Massey

William Stanley Merwin (born September 30, 1927) is an American poet, credited with over fifty books of poetry, translation and prose. During the 1960s anti-war movement, Merwin’s unique craft was thematically characterized by indirect, unpunctuated narration. In the 1980s and 1990s, Merwin’s writing influence derived from his interest in Buddhist philosophy and deep ecology. Residing in Hawaii, he writes prolifically and is dedicated to the restoration of the islands’ rainforests. Merwin has received many honors, including the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry (in both 1971 and 2009), the National Book Award for Poetry (2005) and the Tanning Prize, one of the highest honors bestowed by the Academy of American Poets, as well as the Golden Wreath of the Struga Poetry Evenings. In 2010, the Library of Congress named Merwin the seventeenth United States Poet Laureate to replace the outgoing Kay Ryan. Following his receiving the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 2009, Merwin is recognized as one of the principal contributors to poetry in the early 21st century. Early life W. S. Merwin was born in New York City on September 30, 1927. He grew up on the corner of Fourth Street and New York Avenue in Union City, New Jersey until 1936, when his family moved to Scranton, Pennsylvania. As a child, he was enamored of the natural world, sometimes finding himself talking to the large tree in his back yard. He was also fascinated with things that he saw as links to the past, such as the building behind his home that had once been a barn that housed a horse and carriage. At the age of five he started writing hymns for his father, who was a Presbyterian minister. Career After attending Princeton University, Merwin married his first wife, Dorothy Jeanne Ferry, and moved to Spain. During his stay there, while visiting the renowned poet Robert Graves at his homestead on the island of Majorca, he served as tutor to Graves’s son. There, he met Dido Milroy—fifteen years older than he—with whom he collaborated on a play and whom he later married and lived with in London. In 1956, Merwin moved to Boston for a fellowship at the Poets’ Theater. He returned to London where he was friends with Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes. In 1968, Merwin moved to New York City, separating from his wife who stayed at their home in France. In the late 1970s, Merwin moved to Hawaii and eventually was divorced from Dido Milroy. He married Paula Schwartz in 1983. In 1952 Merwin’s first book of poetry, A Mask for Janus, was published in the Yale Younger Poets Series. W. H. Auden selected the work for that distinction. Later, in 1971 Auden and Merwin would exchange harsh words in the pages of The New York Review of Books. Merwin had published “On Being Awarded the Pulitzer Prize” in the June 3, 1971, issue of The New York Review of Books outlining his objections to the Vietnam War and stating that he was donating his prize money to the draft resistance movement. From 1956 to 1957 Merwin was also playwright-in-residence at the Poet’s Theatre in Cambridge, Massachusetts; he became poetry editor at The Nation in 1962. Besides being a prolific poet (he has published over fifteen volumes of his works), he is also a respected translator of Spanish, French, Latin and Italian poetry (including Dante’s Purgatorio) as well as poetry from Sanskrit, Yiddish, Middle English, Japanese and Quechua. He also served as selector of poems of the late American poet Craig Arnold (1967–2009). Merwin is probably best known for his poetry about the Vietnam War, and can be included among the canon of Vietnam War-era poets which includes such luminaries as Robert Bly, Adrienne Rich; Denise Levertov; Robert Lowell; Allen Ginsberg and Yusef Komunyakaa. In 1998, Merwin wrote Folding Cliffs: A Narrative, an ambitious novel-in-verse about Hawaiʻi in history and legend. Merwin’s early subjects were frequently tied to mythological or legendary themes, while many of his poems featured animals. A volume called The Drunk in the Furnace (1960) marked a change for Merwin, in that he began to write in a much more autobiographical way. The title-poem is about Orpheus, seen as an old drunk. 'Where he gets his spirits / it’s a mystery’, Merwin writes; 'But the stuff keeps him musical’. Another poem of this period—'Odysseus’—reworks the traditional theme in a way that plays off poems by Stevens and Graves on the same topic. In the 1960s, Merwin lived in a small apartment in New York City’s Greenwich Village, and began to experiment boldly with metrical irregularity. His poems became much less tidy and controlled. He played with the forms of indirect narration typical of this period, a self-conscious experimentation explained in an essay called 'On Open Form’ (1969). The Lice (1967) and The Carrier of Ladders (1970) remain his most influential volumes. These poems often used legendary subjects (as in 'The Hydra’ or 'The Judgment of Paris’) to explore highly personal themes. In Merwin’s later volumes—such as The Compass Flower (1977), Opening the Hand (1983), and The Rain in the Trees (1988)—one sees him transforming earlier themes in fresh ways, developing an almost Zen-like indirection. His latest poems are densely imagistic, dream-like, and full of praise for the natural world. He has lived in Hawaii since the 1970s. Migration: New and Selected Poems won the 2005 National Book Award for poetry. A lifelong friend of James Wright, Merwin wrote an elegy to him that appears in the 2008 volume From the Other World: Poems in Memory of James Wright. The Shadow of Sirius, published in 2008 by Copper Canyon Press, was awarded the 2009 Pulitzer Prize for poetry. In June 2010, the Library of Congress named Merwin the seventeenth United States Poet Laureate to replace the outgoing Kay Ryan. He is the subject of the 2014 documentary film Even Though the Whole World Is Burning. Merwin appeared in the PBS documentary “The Buddha,” released in 2010. He had moved to Hawaii to study with the Zen Buddhist master Robert Aitkin in 1976. Personal life Today, Merwin lives on a former pineapple plantation built atop a dormant volcano on the northeast coast of Maui. Awards * Each year links to its corresponding "[year] in poetry" or "[year] in literature" article: * 1952: Yale Younger Poets Prize for A Mask for Janus * 1954: Kenyon Review Fellowship in Poetry * 1956: Rockefeller Fellowship * 1957: National Institute of Arts and Letters grant * 1957: Playwrighting Bursary, Arts Council of Great Britain * 1961: Rabinowitz Foundation Grant * 1962: Bess Hokin Prize, Poetry magazine * 1964/1965: Ford Foundation Grant * 1966: Chapelbrook Foundation Fellowship * 1967: Harriet Monroe Memorial Prize, Poetry magazine * 1969: PEN Translation Prize for Selected Translations 1948-1968 * 1969: Rockefeller Foundation Grant * 1971: Pulitzer Prize for Poetry for The Carrier of Ladders (published in 1971) * 1973: Academy of American Poets Fellowship * 1974: Shelley Memorial Award * 1979: Bollingen Prize for Poetry, Yale University Library * 1987: Governor’s Award for Literature of the state of Hawaii * 1990: Maurice English Poetry Award * 1993: The Tanning Prize for mastery in the art of poetry * 1993: Lenore Marshall Poetry Prize for Travels * 1994: Lila Wallace-Reader’s Digest Writers’ Award * 1998: Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize, awarded by The Poetry Foundation * 1999: Poetry Consultant to the Library of Congress, a jointly-held position with Rita Dove and Louise Glück * 2005: National Book Award for Poetry for Migration: New and Selected Poems * 2004: Golden Wreath Award of the Struga Poetry Evenings Festival in Macedonia * 2004: Lannan Lifetime Achievement Award * 2008: Golden Plate Award, American Academy of Achievement * 2009: Pulitzer Prize for Poetry for The Shadow of Sirius (published in 2008) * 2010: Kenyon Review Award for Literary Achievement * 2010: United States Poet Laureate * 2013: The Zbigniew Herbert International Literary Award Other accolades * Merwin’s former home town of Union City, New Jersey honored him in 2006 by renaming a local street near his former home W.S. Merwin Way. Bibliography * * Each year links to its corresponding "[year] in poetry" or "[year] in literature" article: Poetry - collections * * 1952: A Mask for Janus, New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press; awarded the Yale Younger Poets Prize, 1952 (reprinted as part of The First Four Books of Poems, 1975) * 1954: The Dancing Bears, New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press (reprinted as part of The First Four Books of Poems, 1975) * 1956: Green with Beasts, New York: Knopf (reprinted as part of The First Four Books of Poems, 1975) * 1960: The Drunk in the Furnace, New York: Macmillan (reprinted as part of The First Four Books of Poems, 1975) * 1963: The Moving Target, New York: Atheneum * 1966: Collected Poems, New York: Atheneum * 1967: The Lice, New York: Atheneum * 1969: Animae, San Francisco: Kayak * 1970: The Carrier of Ladders, New York: Atheneum;—winner of the Pulitzer Prize * 1970: Signs, illustrated by A. D. Moore; Iowa City, Iowa: Stone Wall Press * 1973: Writings to an Unfinished Accompaniment, New York: Atheneum * 1975: The First Four Books of Poems, containing A Mask for Janus, The Dancing Bears, Green with Beasts, and The Drunk in the Furnace, New York: Atheneum; (reprinted in 2000, Port Townsend, Washington: Copper Canyon Press) * 1977: The Compass Flower, New York: Atheneum * 1978: Feathers From the Hill, Iowa City, Iowa: Windhover * 1982: Finding the Islands, San Francisco: North Point Press * 1983: Opening the Hand, New York: Atheneum * 1988: The Rain in the Trees, New York: Knopf * 1988: Selected Poems, New York: Atheneum * 1993: The Second Four Books of Poems, Port Townsend, Washington: Copper Canyon Press * 1993: Travels: Poems, New York: Knopf winner of the 1993 Lenore Marshall Poetry Prize * 1996: The Vixen: Poems, New York: Knopf * 1997: Flower and Hand: Poems, 1977-1983 Port Townsend, Washington: Copper Canyon Press * 1998: The Folding Cliffs: A Narrative, a “novel-in-verse” New York: Knopf * 1999: The River Sound: Poems, New York: Knopf * 2001: The Pupil, New York: Knopf * 2005: Migration: New and Selected Poems, Port Townsend, Washington: Copper Canyon Press—winner of the National Book Award for Poetry * 2005: Present Company, Port Townsend, Washington: Copper Canyon Press * 2008: The Shadow of Sirius, Port Townsend, Washington: Copper Canyon Press—winner of the Pulitzer Prize * 2013: The Collected Poems of W. S. Merwin, New York: Library of America * 2014: The Moon Before Morning, Port Townsend, Washington: Copper Canyon Press Poems * Prose * * 1970: The Miner’s Pale Children, New York: Atheneum (reprinted in 1994, New York: Holt) * 1977: Houses and Travellers, New York: Atheneum (reprinted in 1994, New York: Holt) * Regions of Memory * 1982: Unframed Originals: Recollections * 1992: The Lost Uplands: Stories of Southwest France, New York: Knopf * 2002: The Mays of Ventadorn, National Geographic Directions Series; Washington: National Geographic * 2004: The Ends of the Earth, essays, Washington: Shoemaker & Hoard * 2005: Summer Doorways: A Memoir * 2007: The Book of Fables, Port Townsend, Washington: Copper Canyon Press Plays * * 1956: Darkling Child (with Dido Milroy), produced this year * 1957: Favor Island, produced this year at Poets’ Theatre in Cambridge, Massachusetts (broadcast in 1958 by Third Programme, British Broadcasting Corporation) * 1961: The Gilded West, produced this year at Belgrade Theatre, Coventry, England Translations * * 1959: The Poem of the Cid, London: Dent (American edition, 1962, New York: New American Library) * 1960: The Satires of Persius, Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press * 1961: Some Spanish Ballads, London: Abelard (American edition: Spanish Ballads, 1961, New York: Doubleday Anchor) * 1962: The Life of Lazarillo de Tormes: His Fortunes and Adversities, a Spanish novella; New York: Doubleday Anchor * 1963: The Song of Roland * 1969: Selected Translations, 1948 - 1968, New York: Atheneum; winner of the PEN Translation Prize * 1969: Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair, poems by Pablo Neruda; London: Jonathan Cape (reprinted in 2004 with an introduction by Christina Garcia, New York: Penguin Books) * 1969: Products of the Perfected Civilization, Selected Writings of Chamfort, also author of the introduction; New York: Macmillan * 1969: Voices: Selected Writings of Antonio Porchia, Chicago: Follett (reprinted in 1988 and 2003, Port Townsend, Washington: Copper Canyon Press) * 1969: Transparence of the World, poems by Jean Follain, New York: Atheneum (reprinted in 2003, Port Townsend, Washington: Copper Canyon Press) * 1971: “Eight Quechua Poems”, The Hudson Review * 1973: Asian Figures, New York: Atheneum * 1974: Osip Mandelstam: Selected Poems (with Clarence Brown), New York: Oxford University Press (reprinted in 2004 as The Selected Poems of Osip Mandelstam, New York: New York Review of Books) * 1977: Sanskrit Love Poetry (with J. Moussaieff Masson), New York: Columbia University Press (published in 1981 as Peacock’s Egg: Love Poems from Ancient India, San Francisco: North Point Press) * 1977: Vertical Poetry, poems by Roberto Juarroz; San Francisco: Kayak (reprinted in 1988; San Francisco: North Point Press) * 1978: Euripides’ Iphigeneia at Aulis (with George E. Dimock, Jr.), New York: Oxford University Press * 1979: Selected Translations, 1968-1978, New York: Atheneum * 1981: Robert the Devil, an anonymous French play; with an introduction by the translator; Iowa City, Iowa: Windhover * 1985: Four French Plays, including Robert the Devil; The Rival of His Master and Turcaret by Alain-René Lesage; and The False Confessions by Pierre de Marivaux; New York: Atheneum * 1985: From the Spanish Morning, consisting of Spanash Ballads by Lope de Rueda and Eufemia: The Life of Lazarillo de Torres (originally translated in Tulane Drama Review, December 1958); New York: Atheneum * 1989: Sun at Midnight, poems by Musō Soseki (with Soiku Shigematsu) * 1996: Pieces of Shadow: Selected Poems of Jaime Sabines * 1998: East Window: The Asian Translations, translated poems from earlier collections, Port Townsend, Washington: Copper Canyon Press * 2000: Purgatorio from The Divine Comedy of Dante; New York: Knopf * 2005: Gawain and the Green Knight, a New Verse Translation, New York: Knopf * 2013: Selected Translations, translated poems from 1948 - 2010, Port Townsend, Washington: Copper Canyon Press * 2013: Collected Haiku of Yosa Buson, Port Townsend, Washington: Copper Canyon Press (with Takako Lento) * 2013: Sun At Midnight, poems by Muso Soseki, Port Townsend, Washington: Copper Canyon Press (with Soiku Shigematsu) (updated and reissued) Editor * * 1961: West Wind: Supplement of American Poetry, London: Poetry Book Society * 1996: Lament for the Makers: A Memorial Anthology (compiler), Washington: Counterpoint Other sources * * The Union City Reporter March 12, 2006. Archives * * Merwin’s literary papers are held at The Rare Book & Manuscript Library (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign). The collection, which is open to researchers, consists of some 5,500 archival items and 450 printed books. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/W._S._Merwin

All the extraordinary events happen in my mind when I am dazing off into a fantasy life. I do love words, I think they are magical. When I write, I escape to another world and sometimes I even get lost. Call me crazy, but at least I am honest. I do not try to control my mind when writing because that will seclude all interest. To write is to harmonize your thoughts peacefully onto paper. Even if you are writing about war. My philosophy is too odd, maybe you won't understand.

Edwin Muir (15 May 1887– 3 January 1959) was an Orcadian poet, novelist and translator, born on a farm in Deerness. He is remembered for his deeply felt and vivid poetry in plain language with few stylistic preoccupations, and for his extensive translations of Franz Kafka’s works with his wife Willa Muir. Biography Muir was born at the farm of Folly in Deerness, the same parish in which his mother was born. The family then moved to the island of Wyre, followed by the mainland of Orkney. In 1901, when he was 14, his father lost his farm, and the family moved to Glasgow. In quick succession his father, two brothers, and his mother died within the space of a few years. His life as a young man was a depressing experience, and involved a raft of unpleasant jobs in factories and offices, including working in a factory that turned bones into charcoal. “He suffered psychologically in a most destructive way, although perhaps the poet of later years benefitted from these experiences as much as from his Orkney 'Eden’.” In 1919, Muir married Willa Anderson, and the two moved to London. About this, Muir wrote simply 'My marriage was the most fortunate event in my life’. They would later collaborate on highly acclaimed English translations of such writers as Franz Kafka, Gerhart Hauptmann, Sholem Asch, Heinrich Mann, and Hermann Broch. Between 1921 and 1923, Muir lived in Prague, Dresden, Italy, Salzburg and Vienna; he returned to the UK in 1924. Between 1925 and 1956, Muir published seven volumes of poetry which were collected after his death and published in 1991 as The Complete Poems of Edwin Muir. From 1927 to 1932 he published three novels, and in 1935 he came to St Andrews, where he produced his controversial Scott and Scotland (1936). From 1946 to 1949 he was Director of the British Council in Prague and Rome. 1950 saw his appointment as Warden of Newbattle Abbey College (a college for working-class men) in Midlothian, where he met fellow Orcadian poet, George Mackay Brown. In 1955 he was made Norton Professor of English at Harvard University. He returned to Britain in 1956 but died in 1959 at Swaffham Prior, Cambridge, and was buried there. A memorial bench was erected in 1962 to Muir in the idyllic village of Swanston, Edinburgh, where he spent time during the 1950s. Work His childhood in remote and unspoiled Orkney represented an idyllic Eden to Muir, while his family’s move to the city corresponded in his mind to a deeply disturbing encounter with the “fallen” world. The emotional tensions of that dichotomy shaped much of his work and deeply influenced his life. His psychological distress led him to undergo Jungian analysis in London. A vision in which he witnessed the creation strengthened the Edenic myth in his mind, leading him to see his life and career as the working-out of an archetypal fable. In his Autobiography he wrote, “the life of every man is an endlessly repeated performance of the life of man...”. He also expressed his feeling that our deeds on Earth constitute “a myth which we act almost without knowing it.” Alienation, paradox, the existential dyads of good and evil, life and death, love and hate, and images of journeys and labyrinths are key elements in his work. His Scott and Scotland advanced the claim that Scotland can create a national literature only by writing in English, an opinion that placed him in direct opposition to the Lallans movement of Hugh MacDiarmid. He had little sympathy for Scottish nationalism. In 1965 a volume of his selected poetry was edited and introduced by T. S. Eliot. Many of Edwin and Willa Muir’s translations of German novels are still in print. The following quotation expresses the basic existential dilemma of Edwin Muir’s life: “I was born before the Industrial Revolution, and am now about two hundred years old. But I have skipped a hundred and fifty of them. I was really born in 1737, and till I was fourteen no time-accidents happened to me. Then in 1751 I set out from Orkney for Glasgow. When I arrived I found that it was not 1751, but 1901, and that a hundred and fifty years had been burned up in my two-days’ journey. But I myself was still in 1751, and remained there for a long time. All my life since I have been trying to overhaul that invisible leeway. No wonder I am obsessed with Time." (Extract from Diary 1937–39.) Muir came to regard his family’s movement from Orkney to Glasgow as a movement from Eden to Hell. In 1958, Edwin and Willa Muir were granted the Johann-Heinrich-Voss Translation Award. Works * We Moderns: Enigmas and Guesses, under the pseudonym Edward Moore, London, George Allen & Unwin, 1918 * Latitudes, New York, B. W. Huebsch, 1924 * First Poems, London, Hogarth Press, 1925 * Chorus of the Newly Dead, London, Hogarth Press, 1926 * Transition: Essays on Contemporary Literature, London, Hogarth Press, 1926 * The Marionette, London, Hogarth Press, 1927 * The Structure of the Novel, London, Hogarth Press, 1928 * John Knox: Portrait of a Calvinist, London, Jonathan Cape, 1929 * The Three Brothers, London, Heinemann, 1931 * Poor Tom, London, J. M. Dent & Sons, 1932 * Variations on a Time Theme, London, J. M. Dent & Sons, 1934 * Scottish Journey London, Heinemann in association with Victor Gollancz, 1935 * Journeys and Places, London, J. M. Dent & Sons, 1937 * The Present Age from 1914, London, Cresset Press, 1939 * The Story and the Fable: An Autobiography, London, Harrap, 1940 * The Narrow Place, London, Faber, 1943 * The Scots and Their Country, London, published for the British Council by Longman, 1946 * The Voyage, and Other Poems, London, Faber, 1946 * Essays on Literature and Society, London, Hogarth Press, 1949 * The Labyrinth, London, Faber, 1949 * Collected Poems, 1921–1951, London, Faber, 1952 * An Autobiography, London: Hogarth Press, 1954 * Prometheus, illustrated by John Piper, London, Faber, 1954 * One Foot in Eden, New York, Grove Press, 1956 * New Poets, 1959 (edited), London, Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1959 * The Estate of Poetry, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press, 1962 * Collected Poems, London and New York, Oxford University Press, 1965 * The Politics of King Lear, New York, Haskell House, 1970 Translations by Willa and Edwin Muir * Power by Lion Feuchtwanger, New York, Viking Press, 1926 * The Ugly Duchess: A Historical Romance by Lion Feuchtwanger, London, Martin Secker, 1927 * Two Anglo-Saxon Plays: The Oil Islands and Warren Hastings, by Lion Feuchtwanger, London, Martin Secker, 1929 * Success: A Novel by Lion Feuchtwanger, New York, Viking Press, 1930 * The Castle by Franz Kafka, London, Martin Secker, 1930 * The Sleepwalkers: A Trilogy by Hermann Broch, Boston, MA, Little, Brown & Company, 1932 * Josephus by Lion Feuchtwanger, New York, Viking Press, 1932 * Salvation by Sholem Asch, New York, G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1934 * The Hill of Lies by Heinrich Mann, London, Jarrolds, 1934 * Mottke, the Thief by Sholem Asch, New York, G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1935 * The Unknown Quantity by Hermann Broch, New York, Viking Press, 1935 * The Jew of Rome: A Historical Romance by Lion Feuchtwanger, London, Hutchinson, 1935 * The Loom of Justice by Ernst Lothar, New York, G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1935 * Night over the East by Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn, London, Sheed & Ward, 1936 * The Pretender by Lion Feuchtwanger, New York, The Viking Press, 1937 * Amerika by Franz Kafka, New York, Doubleday/New Directions, 1946 * The Trial by Franz Kafka, London, Martin Secker, 1937, reissued New York, The Modern Library, 1957 * Metamorphosis and Other Stories by Franz Kafka, Harmondsworth, Penguin Books, 1961. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edwin_Muir

I was born in chicago public housing in the mid 70s. The lack of a male role model drove me in the wrong direction. I've always had a creative mind, I left home at an early age an spent most of my time in the streets. It was there I found my way into music an managed to get a record deal with an independent label. Things didn't go accordingly I ended up dealing drugs which almost cost me my life. Today I'm just a lonely soul trying to find its way.

James Montgomery (4 November 1771– 30 April 1854) was a British poet, hymnwriter and editor. He was particularly associated with humanitarian causes such as the campaigns to abolish slavery and to end the exploitation of child chimney sweeps. Montgomery was born at Irvine in Ayrshire in south-west Scotland, the son of a pastor and missionary of the Moravian Brethren.

I write out my emotions, as every poet does of course. I am a passionate believer that poetry indeed is not just merely told, or thought, it is felt with the heart. True poetry is an extension of one's soul on paper, to touch other's souls in order for the author to be understood or to tell a story. I am Josiah, I am 17 years old. Most of my other poems were written to a girl I was infatuated with, and got my heart miserably broken, but we are best friends now. I still love to write about love though; nowadays my more romantic poems are directed to a wonderful young woman who I regard as the one. She is a true blessing. My other poems are about beautiful things, or my mental hardships that plague me, but are not forever. I hope all of you thoroughly enjoy my poetry.

William Cosmo Monkhouse (18 March 1840– 20 July 1901) was an English poet and critic. He was born in London. His father, Cyril John Monkhouse, was a solicitor; his mother’s maiden name was Delafosse. He was educated at St Paul’s School, quitting it at seventeen to enter the board of trade as a junior supplementary clerk, from which grade he rose eventually to be the assistant-secretary to the finance department of the office. In 1870–71 he visited South America in connection with the hospital accommodation for seamen at Valparaíso, Chile, and other ports; and he served on different departmental committees, notably that of 1894–96 on the Mercantile Marine Fund. He was twice married: first, to Laura, daughter of James Keymer of Dartford; and, secondly, to Leonora Eliza, daughter of Commander Blount, R.N.

Margarita Michelena (Pachuca de Soto, Hidalgo, 21 de julio de 1917 - Ciudad de México, 27 de marzo de 1998) fue una poeta, crítica literaria, periodista y traductora mexicana. Fue fundadora del diario "El Cotidiano"; directora de "El Libro y el Pueblo", "Respuesta", "La Cultura en México" y "Cuestión" y editora de "Novedades y Excélsior". También trabajó como guionista para la XEW y como conductora en XEMX Radio Femenina. Se distinguió por una fina sensibilidad y pureza lírica de bien dibujados símbolos poéticos. Figura en antologías de poesía mexicana e hispanoamericana editadas en México, España y Argentina.

Harriet Monroe (December 23, 1860– September 26, 1936) was an American editor, scholar, literary critic, poet and patron of the arts. She is best known as the founding publisher and long-time editor of Poetry magazine, which made its debut in 1912. As a supporter of the poets Wallace Stevens, Ezra Pound, H. D., T. S. Eliot, William Carlos Williams, Carl Sandburg, Max Michelson and others, she played an important role in the development of modern poetry. Because she was a longtime correspondent of the poets she supported, her letters provide a wealth of information on their thoughts and motives. Monroe was born in Chicago, Illinois. She read at an early age; her father had a large library that provided refuge from domestic discord. In her autobiography, A Poet’s Life: Seventy Years in a Changing World, published two years after her death, Monroe recalls: “I started in early with Shakespeare, Byron, Shelley, with Dickens and Thackeray; and always the book-lined library gave me a friendly assurance of companionship with lively and interesting people, gave me friends of the spirit to ease my loneliness.”

Juan Francisco Manzano (Matanzas, 1797-1856) fue un poeta cubano que nació esclavo durante el periodo colonial. Escribió dos poemarios y su autobiografía, que se publicaron antes de que obtuviera la libertad en 1836. Su Autobiografía constituye el texto más divulgado de la narrativa antiesclavista y se considera un texto clave para comprender el periodo colonial. En 1844 fue víctima de una acusación falsa por supuestamente haber participado en la Conspiración de la Escalera. Fue condenado a prisión y después de salir de la cárcel no volvió a escribir, muriendo en la pobreza en 1856. Juan Francisco Manzano es considerado hoy como uno de los más valiosos e influyentes escritores cubanos del siglo XIX. Infancia Se acepta el año de 1797 como el año de nacimiento de Juan Francisco Manzano en El Molino, una plantación de caña de azúcar cerca de la ciudad de Matanzas. Sus padres eran esclavizados. Su padre era un sastre y su madre, María del Pilar, era una de las esclavizadas preferidas de la señora Beatriz Agustina de Jústiz y Zayas-Bazán, casada con el I marqués de Jústiz de Santa Ana, Manuel José Aparicio del Manzano y Jústiz. Manzano recibió el apellido de sus dueños como era costumbre en esa época. Sus amos le trataban bien, siempre acompañaba a su señora como «un niño de su vejez». De niño recitaba de memoria sermones, el Catecismo, loas y entremeses aprendidos en las misas y representaciones de ópera a las que asistía acompañando a sus amos, que se comportaban benévolamente con él y le permitían corretear por la casa, lo que indica la cierta libertad de la que gozaba Manzano. Desde su adolescencia era conocido en su ambiente como versificador ingenioso, ya que le era fácil resaltar. Sus padrinos eran blancos y el niño esclavizado estaba muy vinculado en general con el mundo de los blancos. Se decía que el niño pasaba más tiempo en los brazos de su señora marquesa que de la propia madre. A pesar del humilde trabajo que ejercía su madre nunca se separaba de ella, solo para dormir. Se le envió a la escuela de su madrina de bautismo enseguida que cumplió los seis años de edad, en dónde lo consideraban «rápido» para aprender. Después de la muerte de su propietaria la marquesa Jústiz de Santa Ana, su propiedad fue transferida a su hija segunda, la marquesa consorte de Prado Ameno, quién abusaba de su poder y le trataba con mucha crueldad. Manzano era maltratado y sufrió frecuentemente varios castigos: era encerrado en una carbonera, pasaba hambre y recibía azotes y golpes. Primeros escritos En 1818, Nicolás de Cárdenas y Manzano, segundo hijo de la marquesa consorte de Prado Ameno,2 lo recibió como sirviente de su casa. Fue entonces cuando Manzano aprendió a leer y escribir. En los libros de su nuevo amo también estudió retórica. Con un permiso –necesario debido a su condición social- pronto publicó sus versos en el volumen lírico Cantos a Lesbia (1821), hoy perdido, al igual que sus nanas y décimas, divulgadas anónimamente en Matanzas . Igual fortuna corrió el poemario Flores pasajeras, compuesto hacia 1830, y también buena parte de la producción que apareció de forma esporádica en periódicos de la época, si bien se salvó parte de ella. Entre los años 1837 y 1838 colaboró con las revistas El Aguinaldo Habanero y El Álbum. Otra obra de Manzano extraviada es la segunda parte de su autobiografía, Apuntes autobiográficos que escribió con su propia y rudimentaria ortografía, ya que se negaba la más elemental instrucción a los esclavos. Esta segunda parte se perdió cuando la conservaba el escritor cubano-español Ramón de Palma, vinculado al Círculo de Domingo del Monte. Manzano escribió la primera parte de su autobiografía en 1839, por iniciativa del activo animador intelectual Domingo del Monte (1804-1853), quien se la había pedido para que formara parte de una serie de alegatos antiesclavistas entregados al comisionado inglés, el abolicionista Richard Robert Madden. References Wikipedia—https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juan_Francisco_Manzano

William Matthews (November 11, 1942– November 12, 1997) was an American poet and essayist. Born and raised in Cincinnati, Ohio, Matthews attended Berkshire School and later earned a bachelor’s degree from Yale University as well as a master’s from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.