Edith Wharton (born Edith Newbold Jones; January 24, 1862– August 11, 1937) was a Pulitzer Prize-winning American novelist, short story writer, and designer. She was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1927, 1928 and 1930. Wharton combined her insider’s view of America’s privileged classes with a brilliant, natural wit to write humorous, incisive novels and short stories of social and psychological insight. She was well acquainted with many of her era’s other literary and public figures, including Theodore Roosevelt.

Poetry is something I do to try and understand the emotions and voice in the back of my head. It's highly therapeutic for me just now, and as a result my work isn't always nice or happy. Sometimes it's quite brutal. But I feel poetry is a multi-faceted tool that should reflect all aspects of life, both good and bad, so this isn't necessarily a negative thing. I am still learning, so bear with me. My aim is to try and produce something accessible to everyone, but also meaningful to me. I also want to make my poetry less insular and more outward looking. Hopefully I'm on the right path with at least some of these goals. Please comment to let me know how I'm getting on.

John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester (1 April 1647– 26 July 1680), was an English poet and courtier of King Charles II’s Restoration court. The Restoration reacted against the “spiritual authoritarianism” of the Puritan era. Rochester was the embodiment of the new era, and he is as well known for his rakish lifestyle as his poetry, although the two were often interlinked. He died at the age of 33 from venereal disease. Rochester’s contemporary Andrew Marvell described him as “the best English satirist,” and he is generally considered to be the most considerable poet and the most learned among the Restoration wits. His poetry, despite being widely censored during the Victorian era, enjoyed a revival from the 1920s onwards, with notable champions including Graham Greene and Ezra Pound. The critic Vivian de Sola Pinto linked Rochester’s libertinism to Hobbesian materialism. During his lifetime, he was best known for A Satyr Against Reason and Mankind, and it remains among his best known works today. Life Upbringing and teens John Wilmot was born at Ditchley House in Oxfordshire on 1 April 1647. His father, Henry, Viscount Wilmot would be created Earl of Rochester in 1652 for his military service to Charles II during the King’s exile under the Commonwealth. Paul Davis describes Henry as "a Cavalier legend, a dashing bon viveur and war-hero who single-handedly engineered the future Charles II’s escape to the Continent (including the famous concealment in an oak tree) after the disastrous battle of Worcester in 1651". His mother, Anne St. John, was a strong-willed Puritan from a noble Wiltshire family. From the age of seven, Rochester was privately tutored, two years later attending the grammar school in nearby Burford. His father died in 1658, and John Wilmot inherited the title of the Earl of Rochester in April of that year. In January 1660, Rochester was admitted as a Fellow commoner to Wadham College, Oxford, a new and comparatively poor college. Whilst there, it is said, the 13-year-old “grew debauched”. In September 1661 he was awarded an honorary M.A. by the newly elected Chancellor of the university, Edward Hyde, Earl of Clarendon, a family friend. As an act of gratitude towards the son of Henry Wilmot, Charles II conferred on Rochester an annual pension of £500. In November 1661 Charles sent Rochester on a three year Grand Tour of France and Italy, and appointed the physician Andrew Balfour as his governor. This exposed him to an unusual degree to European (especially French) writing and thought. In 1664 Rochester returned to London, and made his formal début at the Restoration court on Christmas Day. It has been suggested by a number of scholars that the King took a paternal role in Rochester’s life. Charles II suggested a marriage between Rochester and the wealthy heiress Elizabeth Malet. Her wealth-hungry relatives opposed marriage to the impoverished Rochester, who conspired with his mother to abduct the young Countess. Samuel Pepys described the attempted abduction in his diary on 28 May 1665: Thence to my Lady Sandwich’s, where, to my shame, I had not been a great while before. Here, upon my telling her a story of my Lord Rochester’s running away on Friday night last with Mrs. Mallett, the great beauty and fortune of the North, who had supped at White Hall with Mrs. Stewart, and was going home to her lodgings with her grandfather, my Lord Haly, by coach; and was at Charing Cross seized on by both horse and foot men, and forcibly taken from him, and put into a coach with six horses, and two women provided to receive her, and carried away. Upon immediate pursuit, my Lord of Rochester (for whom the King had spoke to the lady often, but with no successe [sic]) was taken at Uxbridge; but the lady is not yet heard of, and the King mighty angry, and the Lord sent to the Tower. 18-year-old Rochester spent three weeks in the Tower, and was only released after he wrote a penitent apology to the King. Rochester attempted to redeem himself by volunteering for the navy in the Second Dutch War in the winter of 1665, serving under the Earl of Sandwich. His courage at the Battle of Vågen, serving onboard the ship of Thomas Teddeman, made him a war hero. Pleased with his conduct, Charles appointed Rochester a Gentleman of the Bedchamber in March 1666, which granted him prime lodgings in Whitehall and a pension of £1,000 a year. The role encompassed, one week in every four, Rochester helping the King to dress and undress, serve his meals when dining in private, and sleeping at the foot of the King’s bed. In the summer of 1666, Rochester returned to sea, serving under Edward Spragge. He again showed extraordinary courage in battle. Upon returning from sea, Rochester resumed his courtship of Elizabeth Malet. Defying her family’s wishes, Malet eloped with Rochester again in January 1667, and they were married at the Knightsbridge chapel. In October 1667, the monarch granted Rochester special licence to enter the House of Lords early, despite being seven months underage. The act was an attempt by the King to bolster his number of supporters among the Lords. Teenage actress Nell Gwyn “almost certainly” took him as her lover; she was later to become the mistress of Charles II. Gwyn remained a lifelong friend and political associate, and her relationship with the King gave Rochester influence and status within the Court. 20s and last years Rochester’s life was divided between domesticity in the country and a riotous existence at court, where he was renowned for drunkenness, vivacious conversation, and “extravagant frolics” as part of the Merry Gang (as Andrew Marvell described them). The Merry Gang flourished for about 15 years after 1665 and included Henry Jermyn; Charles Sackville, Earl of Dorset; John Sheffield, Earl of Mulgrave; Henry Killigrew; Sir Charles Sedley; the playwrights William Wycherley and George Etherege; and George Villiers, 2nd Duke of Buckingham. Gilbert Burnet wrote of him that, "For five years together he was continually Drunk... [and] not... perfectly Master of himself... [which] led him to... do many wild and unaccountable things." In 1669 he committed treason by boxing the ears of Thomas Killigrew in sight of the monarch and was banned from the court, although the King soon called for his return. In 1673, Rochester began to train Elizabeth Barry as an actress. She went on to become the most famous actress of her age. He took her as his mistress in 1675. The relationship lasted for around five years, and produced a daughter, before descending into acrimony after Rochester began to resent her success. Rochester wrote afterwards, "With what face can I incline/To damn you to be only mine?... Live up to thy might mind/And be the mistress of mankind". When the King’s advisor and friend of Rochester, George Villiers lost power in 1673, Rochester’s standing fell as well. At the Christmas festivities at Whitehall of that year, Rochester delivered a satire to Charles II, “In the Isle of Britain”– which criticized the King for being obsessed with sex at the expense of his kingdom. Charles’ reaction to this satirical portrayal resulted in Rochester’s exile from the court until February. During this time Rochester dwelt at his estate in Adderbury. Despite this, in February 1674, after much petitioning by Rochester, the King appointed him Ranger of Woodstock Park. In June 1675 “Lord Rochester in a frolick after a rant did... beat downe the dyill (i.e. sundial) which stood in the middle of the Privie Garding, which was esteemed the rarest in Europ”. John Aubrey learned what Rochester said on this occasion when he came in from his “revells” with Charles Sackville, Lord Buckhurst, and Fleetwood Sheppard to see the object: “'What... doest thou stand here to fuck time?' Dash they fell to worke”. It has been speculated that the comment refers not to the dial itself, which was not phallic in appearance, but a painting of the King next to the dial that featured his phallic sceptre. Rochester fled the court again. Rochester fell into disfavour again in 1676. During a late-night scuffle with the night watch, one of Rochester’s companions was killed by a pike-thrust. Rochester was reported to have fled the scene of the incident, and his standing with the monarch reached an all time low. Following this incident, Rochester briefly fled to Tower Hill, where he impersonated a mountebank “Doctor Bendo”. Under this persona, he claimed skill in treating “barrenness” (infertility), and other gynecological disorders. Gilbert Burnet wryly noted that Rochester’s practice was “not without success”, implying his intercession of himself as surreptitious sperm donor. On occasion, Rochester also assumed the role of the grave and matronly Mrs. Bendo, presumably so that he could inspect young women privately without arousing their husbands’ suspicions. Death By the age of 33, Rochester was dying, from what is usually described as the effects of syphilis, gonorrhea, or other venereal diseases, combined with the effects of alcoholism. Carol Richards has disputed this, arguing that it is more likely that he died of renal failure due to chronic nephritis as a result of suffering from Bright’s disease. His mother had him attended in his final weeks by her religious associates, particularly Gilbert Burnet, later Bishop of Salisbury. After hearing of Burnet’s departure from his side, Rochester muttered his last words; “Has my friend left me? then I shall die shortly”. In the early morning of 26 July 1680, Rochester died “without a shudder or a sound”. He was buried at Spelsbury Church in Oxfordshire. A deathbed renunciation of libertinism was published and promulgated as the conversion of a prodigal son. Because the first published account of this story appears in Burnet’s own writings, its accuracy has been disputed by some scholars, who accuse Burnet with having shaped the account of Rochester’s denunciation of libertinism to enhance his own reputation. Works * Three major critical editions of Rochester in the twentieth century have taken very different approaches to authenticating and organizing his canon. David Vieth’s 1968 edition adopts a heavily biographical organization, modernizing spellings and heading the sections of his book “Prentice Work”, “Early Maturity”, “Tragic Maturity”, and “Disillusionment and Death”. Keith Walker’s 1984 edition takes a genre-based approach, returning to the older spellings and accidentals in an effort to present documents closer to those a seventeenth century audience would have received. Harold Love’s Oxford University Press edition of 1999, now the scholarly standard, notes the variorum history conscientiously, but arranges works in genre sections ordered from the private to the public. Scholarship has identified approximately 75 authentic Rochester poems. * Rochester’s poetic work varies widely in form, genre, and content. He was part of a “mob of gentlemen who wrote with ease”, who continued to produce their poetry in manuscripts, rather than in publication. As a consequence, some of Rochester’s work deals with topical concerns, such as satires of courtly affairs in libels, to parodies of the styles of his contemporaries, such as Sir Carr Scroope. He is also notable for his impromptus, one of which is a teasing epitaph of King Charles II: * We have a pretty witty king, * And whose word no man relies on, * He never said a foolish thing, * And never did a wise one” * to which Charles supposedly said “that’s true, for my words are my own, but my actions are those of my ministers”. * Rochester’s poetry displays a range of learning and influences. These included imitations of Malherbe, Ronsard, and Boileau. He also translated or adapted from classical authors such as Petronius, Lucretius, Ovid, Anacreon, Horace, and Seneca. * Rochester’s writings were at once admired and infamous. A Satyr Against Mankind (1675), one of the few poems he published (in a broadside in 1679) is a scathing denunciation of rationalism and optimism that contrasts human perfidy with animal wisdom. * The majority of his poetry was not published under his name until after his death. Because most of his poems circulated only in manuscript form during his lifetime, it is likely that much of his writing does not survive. Burnet claimed that Rochester’s conversion experience led him to ask that “all his profane and lewd writings” be burned; it is unclear how much, if any, of Rochester’s writing was destroyed. * Rochester was also interested in the theatre. In addition to an interest in actresses, he wrote an adaptation of Fletcher’s Valentinian (1685), a scene for Sir Robert Howard’s The Conquest of China, a prologue to Elkanah Settle’s The Empress of Morocco (1673), and epilogues to Sir Francis Fane’s Love in the Dark (1675), Charles Davenant’s Circe, a Tragedy (1677). The best-known dramatic work attributed to Rochester, Sodom, or the Quintessence of Debauchery, has never been successfully proven to be written by him. Posthumous printings of Sodom, however, gave rise to prosecutions for obscenity, and were destroyed. On 16 December 2004 one of the few surviving copies of Sodom was sold by Sotheby’s for £45,600. * Rochester’s letters to his wife and to his friend Henry Savile show an admirable mastery of easy, colloquial prose. Reception and influence * Rochester was the model for a number of rake heroes in plays of the period, such as Don John in Thomas Shadwell’s The Libertine (1675) and Dorimant in George Etherege’s The Man of Mode (1676). Meanwhile he was eulogised by his contemporaries such as Aphra Behn and Andrew Marvell, who described him as “the only man in England that had the true vein of satire”. Daniel Defoe quoted him in Moll Flanders, and discussed him in other works. Voltaire, who spoke of Rochester as “the man of genius, the great poet”, admired his satire for its “energy and fire” and translated some lines into French to “display the shining imagination his lordship only could boast”. * By the 1750s, Rochester’s reputation suffered as the liberality of the Restoration era subsided; Samuel Johnson characterised him as a worthless and dissolute rake. Horace Walpole described him as “a man whom the muses were fond to inspire but ashamed to avow”. Despite this general disdain for Rochester, William Hazlitt commented that his “verses cut and sparkle like diamonds” while his “epigrams were the bitterest, the least laboured, and the truest, that ever were written”. Referring to Rochester’s perspective, Hazlitt wrote that “his contempt for everything that others respect almost amounts to sublimity”. Meanwhile, Goethe quoted A Satyr against Reason and Mankind in English in his Autobiography. Despite this, Rochester’s work was largely ignored throughout the Victorian era. * Rochester’s reputation would not begin to revive until the 1920s. Ezra Pound, in his ABC of Reading, compared Rochester’s poetry favourably to better known figures such as Alexander Pope and John Milton. Graham Greene characterised Rochester as a “spoiled Puritan”. Although F. R. Leavis argued that “Rochester is not a great poet of any kind”, William Empson admired him. More recently, Germaine Greer has questioned the validity of the appraisal of Rochester as a drunken rake, and hailed the sensitivity of some of his lyrics. * Rochester was listed #6 in Time Out’s "Top 30 chart of London’s most erotic writers". Tom Morris, the associate director, of the National Theatre said ‘Rochester reminds me of an unhinged poacher, moving noiselessly through the night and shooting every convention that moves. Bishop Burnett, who coached him to an implausible death-bed repentance, said that he was unable to express any feeling without oaths and obscenities. He seemed like a punk in a frock coat. But once the straw dolls have been slain, Rochester celebrates in a sexual landscape all of his own.’ In popular culture * A play, The Libertine (1994), was written by Stephen Jeffreys, and staged by the Royal Court Theatre. The 2004 film The Libertine, based on Jeffreys’ play, starred Johnny Depp as Rochester, Samantha Morton as Elizabeth Barry, John Malkovich as King Charles II and Rosamund Pike as Elizabeth Malet. Michael Nyman set to music an excerpt of Rochester’s poem, “Signor Dildo” for the film. * Rochester is the central character in Anna Lieff Saxby’s 1996 erotic novella 'No Paradise But Pleasure’ References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Wilmot,_2nd_Earl_of_Rochester

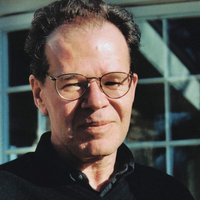

Arthur Yvor Winters (17 October 1900– 25 January 1968) was an American poet and literary critic. Life Winters was born in Chicago, Illinois and he grew up in Eagle Rock, California. He attended the University of Chicago where he was a member of a literary circle that included Glenway Wescott, Elizabeth Madox Roberts and his future wife Janet Lewis. He suffered from tuberculosis in his late teens and moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico. There he recuperated, wrote his early published verse and taught. In 1923 Winters published one of his first critical essays, “Notes on the Mechanics of the Poetic Image,” in the expatriate literary journal Secession. In 1925 he became an undergraduate at the University of Colorado. In 1926, Winters married the poet and novelist Janet Lewis, also from Chicago and a tuberculosis sufferer. After graduating he taught at the University of Idaho and then started a doctorate at Stanford University. He remained at Stanford, living in Los Altos, until two years before his death from throat cancer. His students included the poets Edgar Bowers, Thom Gunn, Donald Hall, Jim McMichael, N. Scott Momaday, Robert Pinsky, John Matthias, Moore Moran, Roger Dickinson-Brown and Robert Hass, the critic Gerald Graff, and the theater director and writer Herbert Blau. He was also a mentor to Donald Justice, J.V. Cunningham and Bunichi Kagawa. He edited the literary magazine Gyroscope with his wife from 1929 to 1931; and Hound & Horn from 1932 to 1934. He was awarded the 1961 Bollingen Prize for Poetry for his Collected Poems. As modernist Winters’s early poetry appeared in small avant-garde magazines alongside work by writers like James Joyce and Gertrude Stein and was written in the modernist idiom; it was heavily influenced both by Native American poetry and by Imagism, being described as 'arriving late at the Imagist feast’. His essay, “The Testament of a Stone,” gives an account of his poetics during this early period. Although beginning his career as an admirer and imitator of the Imagist poets, Winters by the end of the 1920s had formulated a neo-classic poetics. Around 1930, he turned away from modernism and developed an Augustan style of writing, notable for its clarity of statement and its formality of rhyme and rhythm, with most of his poetry thereafter being in the accentual-syllabic form. As critic Winters’s critical style was comparable to that of F. R. Leavis, and in the same way he created a school of students (of mixed loyalty). His affiliations and proposed canon, however, were quite different: Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence above any one novel by Henry James, Robert Bridges above T. S. Eliot, Charles Churchill above Alexander Pope, Fulke Greville and George Gascoigne above Sidney and Spenser. In his view, “a poem in the first place should offer us a new perception . . . bringing into being a new experience.” He attacked Romanticism, particularly in its American manifestations, and assailed Emerson’s reputation as that of a sacred cow. Ironically, his first book of poems, Diadems and Fagots, takes its title from one of Emerson’s poems. In this he was probably influenced by Irving Babbitt. Winters was sometimes and questionably associated with the New Criticism, largely because John Crowe Ransom devoted a chapter to him in his book of the same name. He bestowed the sobriquet “the cool master” on the American poet Wallace Stevens. Winters is best known for his argument attacking the “fallacy of imitative form”: “To say that a poet is justified in employing a disintegrating form in order to express a feeling of disintegration, is merely a sophistical justification for bad poetry, akin to the Whitmanian notion that one must write loose and sprawling poetry to 'express’ the loose and sprawling American continent. In fact, all feeling, if one gives oneself (that is, one’s form) up to it, is a way of disintegration; poetic form is by definition a means to arrest the disintegration and order the feeling; and in so far as any poetry tends toward the formless, it fails to be expressive of anything.” Bibliography * Diadems and Fagots (1921) poems * The Immobile Wind (1921) poems * The Magpie’s Shadow (1922) poems * Secession certain Notes on the Mechanics of the Image (1923) a magazine * The Bare Hills (1927) poems * The Proof (1930) poems * The Journey and Other Poems (1931) poems * Before Disaster (1934) poems * Primitivism and Decadence: A Study of American Experimental Poetry Arrow Editions, New York, 1937 * Maule’s Curse: Seven Studies in the History of American Obscurantism (1938) * Poems (1940) * The Giant Weapon (1943) poems * The Anatomy of Nonsense (1943) * Edwin Arlington Robinson (1946) * In Defense of Reason (1947) collects Primitivism, Maule and Anatomy * To the Holy Spirit (1947) poems * Three Poems (1950) * Collected Poems (1952, revised 1960) * The Function of Criticism: Problems and Exercises (1957) * On Modern Poets: Stevens, Eliot, Ransom, Crane, Hopkins, Frost (1959) * The Early Poems of Yvor Winters, 1920–1928 (1966) * Forms of Discovery: Critical and Historical Essays on the Forms of the Short Poem in English (1967) * Uncollected Essays and Reviews (1976) * The Collected Poems of Yvor Winters; with an introduction by Donald Davie (1978) * Uncollected Poems 1919–1928 (1997) * Uncollected Poems 1929–1957 (1997) * Yvor Winters: Selected Poems (2003) edited by Thom Gunn * As editor * Twelve Poets of the Pacific (1937) * Selected Poems, by Elizabeth Daryush (1948); with a foreword by Winters * Poets of the Pacific, Second Series (1949) * Quest for Reality: An Anthology of Short Poems in English (1969); with, and with an introduction by, Kenneth Fields References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yvor_Winters

Franz Wright (March 18, 1953– May 14, 2015) was an American poet. He and his father James Wright are the only parent/child pair to have won the Pulitzer Prize in the same category. Life and career Wright was born in Vienna, Austria. He graduated from Oberlin College in 1977. Wheeling Motel (Knopf, 2009), had selections put to music for the record Readings from Wheeling Motel. Wright wrote the lyrics to and performs the Clem Snide song "Encounter at 3AM" on the album Hungry Bird (2009). Wright’s most recent books include Kindertotenwald (Knopf, 2011), a collection of sixty-five prose poems concluding with a love poem to his wife, written while Wright had terminal lung cancer. The poem won Poetry magazine’s premier annual literary prize for best work published in the magazine during 2011. The prose poem collection was followed in 2012 by Buson: Haiku, a collection of translations of 30 haiku by the Japanese poet Yosa Buson, published in a limited edition of a few hundred copies by Tavern Books. . In 2013 Wright’s primary publisher, Knopf in New York, brought out another full length collection of verse and prose poems, F, which was begun in the ICU of a Boston hospital after excision of part of a lung. F was the most positively received to any of Wright’s work. Writing in the Huffington Post, Anis Shivani placed it among the best books of poetry yet produced by an American, and called Wright “our greatest contemporary poet.” In 2013 Wright recorded 15 prose poems from Kindertotenwald for inclusion in a series of improvisational concerts performed in European venues, arranged by David Sylvian, Stephan Mathieu and Christian Fennesz. Prior to his death, Wright had been working on a new manuscript. First its name was “Changed,” then “Axe in Blossom,” and has probably ended up taking the form of a chapbook available as of 2016, entitled, “The Toy Throne.” Wright has been anthologised in works such as The Best of the Best American Poetry as well as Czeslaw Milosz’s anthology A Book of Luminous Things Bearing the Mystery: Twenty Years of Image, and American Alphabets: 25 Contemporary Poets. Death Wright died of cancer at his home in Waltham, Massachusetts on May 14, 2015. Criticism Writing in the New York Review of Books, Helen Vendler said "Wright’s scale of experience, like Berryman’s, runs from the homicidal to the ecstatic... [His poems’] best forms of originality [are] deftness in patterning, startling metaphors, starkness of speech, compression of both pain and joy, and a stoic self-possession with the agonies and penalties of existence." Novelist Denis Johnson has said Wright’s poems “are like tiny jewels shaped by blunt, ruined fingers—miraculous gifts.” The Boston Review has called Wright’s poetry “among the most honest, haunting, and human being written today.” Critic Ernest Hilbert wrote for Random House’s magazine Bold Type that “Wright oscillates between direct and evasive dictions, between the barroom floor and the arts club podium, from aphoristic aside to icily poetic abstraction.” Walking to Martha’s Vineyard (2003) in particular, was well received. According to Publishers Weekly, the collection features "[h]eartfelt but often cryptic poems... fans will find Wright’s self-diagnostics moving throughout." The New York Times noted that Wright promises, and can deliver, great depths of feeling, while observing that Wright depends very much on our sense of his tone, and on our belief not just that he means what he says but that he has said something new...[on this score] Walking to Martha’s Vineyard sometimes succeeds.” Poet Jordan Davis, writing for The Constant Critic, suggested that Wright’s collection was so accomplished it would have to be kept “out of the reach of impulse kleptomaniacs.” Added Davis, “deader than deadpan, any particular Wright poem may not seem like much, until, that is, you read a few of them. Once the context kicks in, you may find yourself trying to track down every word he’s written.” Some critics were less welcoming. According to New Criterion critic William Logan, with whom Wright would later publicly feud, "[t]his poet is surprisingly vague about the specifics of his torment (most of his poems are shouts and curses in the dark). He was cruelly affected by the divorce of his parents, though perhaps after forty years there should be a statute of limitation... ‘The Only Animal,’ the most accomplished poem in the book, collapses into the same kitschy sanctimoniousness that puts nodding Jesus dolls on car dashboards." “Wright offers the crude, unprocessed sewage of suffering”, he comments. “He has drunk harder and drugged harder than any dozen poets in our health-conscious age, and paid the penalty in hospitals and mental wards.” The critical reception of Wright’s 2011 collection, Kindertotenwald (Knopf), has been positive on the whole. Writing in the Washington Independent Book Review, Grace Cavalieri speaks of the book as a departure from Wright’s best known poems. “The prose poems are intriguing thought patterns that show poetry as mental process... This is original material, and if a great poet cannot continue to be original, then he is really not all that great... In this text there is a joyfulness that energizes and makes us feel the writing as a purposeful surge. It is a life force. This is a good indicator of literary art... Memory and the past, mortality, longing, childhood, time, space, geography and loneliness, are all the poet’s playthings. In these conversations with himself, Franz Wright shows how the mind works with his feelings and his brain’s agility in its struggle with the heart.” Cultural critic for the Chicago Tribune Julia Keller says that Kindertotenwald is “ultimately about joy and grace and the possibility of redemption, about coming out whole on the other side of emotional catastrophe.” “This collection, like all of Wright’s book, combines familiar, colloquial phrases—the daily lingo you hear everywhere—with the sudden sharpness of a phrase you’ve never heard anywhere, but that sounds just as familiar, just as inevitable. These pieces are written in closely packed prose, like miniature short stories, but they have a fierce lilting beauty that marks them as poetry. Reading 'Kindertotenwald’ is like walking through a plate-glass window on purpose. There is—predictably—pain, but once you’ve made it a few steps past the threshold, you realize it wasn’t glass after all, only air, and that the shattering sound you heard was your own heart breaking. Healing, though, is possible. ”Soon, soon," the poet writes in “Nude With Handgun and Rosary,” “between one instant and the next, you will be well.” Awards * 1985, 1992 National Endowment for the Arts grant * 1989 Guggenheim Fellowship * 1991 Whiting Award * 1996 PEN/Voelcker Award for Poetry * 2004 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry, for Walking to Martha’s Vineyard Selected works * * The Writing, Argos Books, 2015, ISBN 978-1-938247-09-5 * F, Knopf, 2013 * Kindertotenwald Alfred A. Knopf, 2011, ISBN 978-0-307-27280-5 * "7 Prose", Marick Press, 2010, ISBN 978-1934851-17-3 * Wheeling Motel Alfred A. Knopf, 2009, ISBN 9780307265685 * Earlier Poems, Random House, Inc., 2007, ISBN 978-0-307-26566-1 * God’s Silence, Knopf, 2006, ISBN 978-1-4000-4351-4 * Walking to Martha’s Vineyard Alfred A. Knopf, 2003, ISBN 978-0-375-41518-0 * The Beforelife A.A. Knopf, 2001, ISBN 978-0-375-41154-0 * Knell Short Line Editions, 1999 * ILL LIT: Selected & New Poems Oberlin College Press, 1998, ISBN 978-0-932440-83-9 * Rorschach test, Carnegie Mellon University Press, 1995, ISBN 978-0-88748-209-0 * The Night World and the Word Night Carnegie Mellon University Press, 1993, ISBN 978-0-88748-154-3 * Entry in an Unknown Hand Carnegie Mellon University Press, 1989, ISBN 978-0-88748-078-2 * Going North in Winter Gray House Press, 1986 * The One Whose Eyes Open When You Close Your Eyes Pym-Randall Press, 1982, ISBN 978-0-913219-35-5 * 8 Poems (1982) * The Earth Without You Cleveland State University Poetry Center, 1980, ISBN 9780914946236 * Tapping the White Cane of Solitude (1976) Translations * * The Unknown Rilke: Selected Poems, Rainer Maria Rilke, Translator Franz Wright, Oberlin College Press, 1990, ISBN 978-0-932440-56-3 * Valzhyna Mort: Factory of Tears (Copper Canyon Press, 2008) (translated from the Belarusian language in collaboration with the author and Elizabeth Oehlkers Wright) * “The Unknown Rilke: Expanded Edition” (1991) * “No Siege is Absolute: Versions of Rene Char” (1984) * "Buson: Haiku (2012) The Life of Mary (poems of R.M. Rilke) (1981) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Franz_Wright

Dorothy Mae Ann Wordsworth (25 December 1771 – 25 January 1855) was an English author, poet and diarist. She was the sister of the Romantic poet William Wordsworth, and the two were close all their lives. Wordsworth had no ambitions to be an author, and her writings consist only of series of letters, diary entries, poems and short stories. Life She was born on Christmas Day in Cockermouth, Cumberland in 1771. Despite the early deaths of both her parents, Dorothy, William and their three siblings had a happy childhood. When in 1783, their father died and the children were sent to live with various relatives. Wordsworth was sent alone to live with her aunt, Elizabeth Threlkeld, in Halifax, West Yorkshire. After she was able to reunite with William firstly at Racedown Lodge in Dorset in 1795 and afterwards (1797/98) at Alfoxden House in Somerset, they became inseparable companions. The pair lived in poverty at first; and would often beg for cast-off clothes from their friends. William wrote of her in his famous Tintern Abbey poem: Of this fair river; thou my dearest Friend, My dear, dear Friend; and in thy voice I catch The language of my former heart, and read My former pleasures in the shooting lights Of thy wild eyes [...] My dear, dear Sister! Wordsworth was a diarist and somewhat amateur poet with little interest in becoming an established writer. "I should detest the idea of setting myself up as an author," she once wrote, "give Wm. the Pleasure of it." She almost published her travel account with William to Scotland in 1803 Recollections of a Tour Made in Scotland, but a publisher was not found and it would not be published until 1874. She wrote a very early account of an ascent of Scafell Pike in 1818 (perhaps predated only by Samuel Taylor Coleridge's of 1802), climbing the mountain in the company of her friend Mary Barker, Miss Barker's maid, and two local people to act as guide and porter. Dorothy's work was used in 1822 by her brother William, unattributed, in his popular guide book to the Lake District - and this was then copied by Harriet Martineau in her equally successful guide[5] (in its fourth edition by 1876), but with attribution, if only to William Wordsworth. Consequently this story was very widely read by the many visitors to the Lake District over more than half of the 19th century. She never married, and after William married Mary Hutchinson in 1802, continued to live with them. She was by now 31, and thought of herself as too old for marriage. In 1829 she fell seriously ill and was to remain an invalid for the remainder of her life. She died at eighty-three in 1855, having spent the past twenty years in, according to the biographer Richard Cavendish, "a deepening haze of senility". Her Grasmere Journal was published in 1897, edited by William Angus Knight. The journal eloquently described her day-to-day life in the Lake District, long walks she and her brother took through the countryside, and detailed portraits of literary lights of the early 19th century, including Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Sir Walter Scott, Charles Lamb and Robert Southey, a close friend who popularised the fairytale Goldilocks and the Three Bears. Dorothy's works came to light just as literary critics were beginning to re-examine women's role in literature. The success of the Grasmere Journal led to a renewed interest in Wordsworth, and several other journals and collections of her letters have since been published. The Grasmere Journal and Wordsworth's other works revealed how vital she was to her brother's success. William relied on her detailed accounts of nature scenes and borrowed freely from her journals. For example Dorothy wrote in her journal of 5 April 1802 "... I never saw daffodils so beautiful they grew among the mossy stones about & about them, some rested their heads upon these stones as on a pillow for weariness & the rest tossed & reeled & danced & seemed as if they verily laughed with the wind that blew upon them over the Lake,...". This passage is clearly brought to mind when reading William's "Daffodils", where her brother, in this poem of two years later, describes what appears to be the shared experience in the journal as his own solitary observation. References Wikipeda - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dorothy_Wordsworth

I'm just a junior in high school that has never attempted poetry before this year. I'm open to any sort of criticism and would love for people to critic my poems so i can grow in the art. I don't, at least haven't, restricted myself to just one form of poetry. I just like to write how i feel in the moment, not how I think other people want to hear about how I feel.

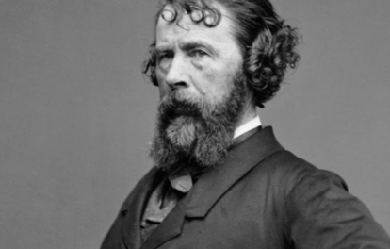

Nathaniel Parker Willis (January 20, 1806 – January 20, 1867), also known as N. P. Willis, was an American author, poet and editor who worked with several notable American writers including Edgar Allan Poe and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. He became the highest-paid magazine writer of his day. For a time, he was the employer of former slave and future writer Harriet Jacobs. His brother was the composer Richard Storrs Willis and his sister Sara wrote under the name Fanny Fern. Born in Portland, Maine, Willis came from a family of publishers. His grandfather Nathaniel Willis owned newspapers in Massachusetts and Virginia, and his father Nathaniel Willis was the founder of Youth’s Companion, the first newspaper specifically for children. Willis developed an interest in literature while attending Yale College and began publishing poetry. After graduation, he worked as an overseas correspondent for the New York Mirror. He eventually moved to New York and began to build his literary reputation. Working with multiple publications, he was earning about $100 per article and between $5,000 and $10,000 per year. In 1846, he started his own publication, the Home Journal, which was eventually renamed Town & Country. Shortly after, Willis moved to a home on the Hudson River where he lived a semi-retired life until his death in 1867. Willis embedded his own personality into his writing and addressed his readers personally, specifically in his travel writings, so that his reputation was built in part because of his character. Critics, including his sister in her novel Ruth Hall, occasionally described him as being effeminate and Europeanized. Willis also published several poems, tales, and a play. Despite his intense popularity for a time, at his death Willis was nearly forgotten. Life and career Early life and family Nathaniel Parker Willis was born on January 20, 1806, in Portland, Maine. His father Nathaniel Willis was a newspaper proprietor there and his grandfather owned newspapers in Boston, Massachusetts and western Virginia. His mother was Hannah Willis (née Parker) from Holliston, Massachusetts and it was her husband’s offer to edit the Eastern Argus in Maine that caused their move to Portland. Willis’s younger sister was Sara Willis Parton, who would later become a writer under the pseudonym Fanny Fern. His brother, Richard Storrs Willis, became a musician and music journalist known for writing the melody for “It Came Upon the Midnight Clear”. His other siblings were Lucy Douglas (born 1804), Louisa Harris (1807), Julia Dean (1809), Mary Perry (1813), Edward Payson (1816), and Ellen Holmes (1821).In 1816, the family moved to Boston, where Willis’s father established the Boston Recorder and, nine years later, the Youth’s Companion, the world’s first newspaper for children. The elder Willis’s emphasis on religious themes earned him the nickname “Deacon” Willis. After attending a Boston grammar school and Phillips Academy at Andover, Nathaniel Parker Willis entered Yale College in October 1823 where he roomed with Horace Bushnell. Willis credited Bushnell with teaching him the proper technique for sharpening a razor by “drawing it from heel to point both ways... the two cross frictions correct each other”. At Yale, he further developed an interest in literature, often neglecting his other studies. He graduated in 1827 and spent time touring parts of the United States and Canada. In Montreal, he met Chester Harding, with whom he would become a lifelong friend. Years later, Harding referred to Willis during this period as “the 'lion’ of the town”. Willis began publishing poetry in his father’s Boston Periodical, often using one of two literary personalities under the pen names “Roy” (for religious subjects) and “Cassius” (for more secular topics). The same year, Willis published a volume of poetical Sketches. Literary career In the latter part of the 1820s, Willis began contributing more frequently to magazines and periodicals. In 1829, he served as editor for the gift book The Token, making him the only person to be editor in the book’s 15-year history besides its founder, Samuel Griswold Goodrich. That year, Willis founded the American Monthly Magazine, which began publishing in April 1829 until it was discontinued in August 1831. He blamed its failure on the “tight purses of Boston culture” and moved to Europe to serve as foreign editor and correspondent of the New York Mirror. In 1832, while in Florence, Italy, he met Horatio Greenough, who sculpted a bust of the writer. Between 1832 and 1836, Willis contributed a series of letters for the Mirror, about half of which were later collected as Pencillings by the Way, printed in London in 1835. The romantic descriptions of scenes and modes of life in Europe sold well despite the then high price tag of $7 a copy. The work became popular and boosted Willis’s literary reputation enough that an American edition was soon issued. Despite this popularity, he was censured by some critics for indiscretion in reporting private conversations. At one point he fought a bloodless duel with Captain Frederick Marryat, then editor of the Metropolitan Magazine, after Willis sent a private letter of Marryat’s to George Pope Morris, who had it printed. Still, in 1835 Willis was popular enough to introduce Henry Wadsworth Longfellow to important literary figures in England, including Ada Byron, daughter of Lord Byron.While abroad, Willis wrote to a friend, “I should like to marry in England”. He soon married Mary Stace, daughter of General William Stace of Woolwich, on October 1, 1835, after a month-long engagement. The couple took a two-week honeymoon in Paris. The couple moved to London where, in 1836, Willis met Charles Dickens, who was working for the Morning Chronicle at the time.In 1837, Willis and his wife returned to the United States and settled at a small estate on Owego Creek in New York, just above its junction with the Susquehanna River. He named the home Glenmary and the 200-acre (0.81 km2) rural setting inspired him to write Letters from under a Bridge. On October 20, 1838, Willis began a series of articles called “A New Series of Letters from London”, one of which suggested an illicit relationship between writer Letitia Elizabeth Landon and editor William Jordan. The article caused some scandal, for which Willis’s publisher had to apologize.On June 20, 1839, Willis’s play Tortesa, the Usurer premiered in Philadelphia at the Walnut Street Theatre. Edgar Allan Poe called it “by far the best play from the pen of an American author”. That year, he was also editor of the short-lived periodical The Corsair, for which he enlisted William Makepeace Thackery to write short sketches of France. Another major work, Two Ways of Dying for a Husband, was published in England during a short visit there in 1839–1840. Shortly after returning to the United States, his personal life was touched with grief when his first child was stillborn on December 4, 1840. He and Stace had a second daughter, Imogen, who was born June 20, 1842.Later that year, Willis attended a ball in honor of Charles Dickens in New York. After dancing with Dickens’s wife, Willis and Dickens went out for “rum toddy and broiled oysters”. By this time, his fame had grown enough that he was often invited to lecture and recite poetry, including his presentation to the Linonian Society at Yale on August 17, 1841. Willis was invited to submit a column to the each weekly issue of Brother Johnathan, a publication from New York with 20,000 subscribers, which he did until September 1841. By 1842, Willis was earning the unusually high salary of $4,800 a year. As a later journalist remarked, this made Willis “the first magazine writer who was tolerably well paid”.In 1842, Willis employed Harriet Jacobs, an escaped slave from North Carolina, as a house servant and nanny. When her owners sought to have her returned to their plantation, Willis’s wife bought her freedom for $300. Nearly two decades later, Jacobs would write in her pseudonymized autobiography Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, which she began composing while working for the Willis family, that she “was convinced that... Nathaniel Parker Willis was proslavery”. Willis is depicted as “Mr. Bruce”, an unattractive Southern sympathizer in the book. One of Willis’s tales, “The Night Funeral of a Slave”, featured an abolitionist who visits the South and regrets his anti-slavery views; Frederick Douglass later used the work to criticize Northerners who were pro-slavery. Evening Mirror Returning to New York City, Willis reorganized, along with George Pope Morris, the weekly New York Mirror as the daily Evening Mirror in 1844 with a weekly supplement called the Weekly Mirror, in part due to the rising cost of postage. By this time, Willis was a popular writer (a joke was that Johann Wolfgang von Goethe was Germany’s version of N. P. Willis) and one of the first commercially successful magazine writers in America. In the fall of that year, he also became the first editor of the annual gift book The Opal founded by Rufus Wilmot Griswold. During this time, he became the highest-paid magazine writer in America, earning about $100 per article and $5,000 per year, a number which would soon double. Even the popular poet Longfellow admitted his jealousy of Willis’s salary.As a critic, Willis did not believe in including discussions of personalities of writers when reviewing their works. He also believed that, though publications should discuss political topics, they should not express party opinions or choose sides. The Mirror flourished at a time when many publications were discontinuing. Its success was due to the shrewd management of Willis and Morris and the two demonstrated that the American public could support literary endeavors. Willis was becoming an expert in American literature and so, in 1845, Willis and Morris issued an anthology, The Prose and Poetry of America.While Willis was editor of the Evening Mirror, its issue for January 29, 1845, included the first printing of Poe’s poem “The Raven” with his name attached. In his introduction, Willis called it “unsurpassed in English poetry for subtle conception, masterly ingenuity of versification, and consistent, sustaining of imaginative lift... It will stick to the memory of everybody who reads it”. Willis and Poe were close friends, and Willis helped Poe financially during his wife Virginia’s illness and while Poe was suing Thomas Dunn English for libel. Willis often tried to persuade Poe to be less destructive in his criticism and concentrate on his poetry. Even so, Willis published many pieces of what would later be referred to as “The Longfellow War”, a literary battle between Poe and the supporters of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, whom Poe called overrated and guilty of plagiarism. Willis also introduced Poe to Fanny Osgood; the two would later carry out a very public literary flirtation.Willis’s wife Mary Stace died in childbirth on March 25, 1845. Their daughter, Blanche, died as well and Willis wrote in his notebook that she was “an angel without fault or foible”. He brought his surviving daughter Imogen to England to be with her mother’s family and left her behind when he returned to the United States. In October 1846, he married Cornelia Grinnell, a wealthy Quaker from New Bedford and the adopted daughter of a local Congressman. She was two decades younger than Willis at the time and vocally disliked slavery, unlike her new husband. After the marriage, Willis’s daughter Imogen came to live with the newlyweds in New York. Home Journal In 1846, Willis and Morris left the Evening Mirror and attempted to edit a new weekly, the National Press, which was renamed the Home Journal after eight months. Their prospectus for the publication, published November 21, 1846, announced their intentions to create a magazine “to circle around the family table”. Willis intended the magazine for the middle and lower classes and included the message of upward social mobility, using himself as an example, often describing in detail his personal possessions. When discussing his own social climbing, however, he emphasized his frustrations rather than his successes, endearing him to his audience. He edited the Home Journal until his death in 1867. It was renamed Town & Country in 1901, and it is still published under that title as of 2011. During Willis’s time at the journal, he especially promoted the works of women poets, including Frances Sargent Osgood, Anne Lynch Botta, Grace Greenwood, and Julia Ward Howe. Willis and his editors favorably reviewed many works now considered important today, including Henry David Thoreau’s Walden and Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Blithedale Romance. Idlewild In 1846, Willis settled near the banks of Canterbury Creek near the Hudson River in New York and named his new home Idlewild. When Willis first visited the property, the owners said it had little value and that it was “an idle wild of which nothing could ever be made”. He built a fourteen-room “cottage”, as he called it, at the edge of a plateau by Moodna Creek next to a sudden 200-foot (61 m) drop into a gorge. Willis worked closely with the architect, Calvert Vaux, to carefully plan each gable and piazza to fully take advantage of the dramatic view of the river and mountains.Because of failing health Willis spent the remainder of his life chiefly in retirement at Idlewild. His wife Cornelia was also recovering from a difficult illness after the birth of their first child together, a son named Grinnell, who was born April 28, 1848. They had four other children: Lilian (born April 27, 1850), Edith (born September 28, 1853), Bailey (born May 31, 1857), and a daughter who died only a few minutes after her birth on October 31, 1860. Harriet Jacobs was re-hired by Willis to work for the family.During these last years at Idlewild, Willis continued contributing a weekly letter to the Home Journal. In 1850 he assisted Rufus Wilmot Griswold in preparing an anthology of the works of Poe, who had died mysteriously the year before. Griswold also wrote the first biography of Poe in which he purposely set out to ruin the dead author’s reputation. Willis was one of the most vocal of Poe’s defenders, writing at one point: “The indictment (for it deserves no other name) is not true. It is full of cruel misrepresentations. It deepens the shadows unto unnatural darkness, and shuts out the rays of sunshines that ought to relieve them”.Willis was involved in the 1850 divorce suit between the actor Edwin Forrest and his wife Catherine Norton Sinclair Forrest. In January 1849, Forrest had found a love letter to his wife from fellow actor George W. Jamieson. As a result, he and Catherine separated in April 1849. He moved to Philadelphia and filed for divorce in February 1850 though the Pennsylvania legislature denied his application. Catharine went to live with the family of Parke Godwin and the separation became a public affair, with newspapers throughout New York reporting on supposed infidelities and other gossip.Willis defended Catharine, who maintained her innocence, in the Home Journal and suggested that Forrest was merely jealous of her intellectual superiority. On June 17, 1850, shortly after Forrest had filed for divorce in the New York Supreme Court, Forrest beat Willis with a gutta-percha whip in New York’s Washington Square, shouting “this man is the seducer of my wife”. Willis, who was recovering from a rheumatic fever at the time, was unable to fight back. His wife soon received an anonymous letter with an accusation that Willis was in an adulterous relationship with Catherine Forrest. Willis later sued Forrest for assault and, by March 1852, was awarded $2,500 plus court costs. Throughout the Forrest divorce case, which lasted six weeks, several witnesses made additional claims that Catherine Forrest and Nathaniel Parker Willis were having an affair, including a waiter who claimed he had seen the couple “lying on each other”. As the press reported, “thousands and thousands of the anxious public” awaited the court’s verdict; ultimately, the court sided with Catherine Forrest and Willis’s name was cleared. Ruth Hall Willis arbitrarily refused to print the work of his sister Sara Willis ("Fanny Fern") after 1854, though she previously had contributed anonymous book reviews to the Home Journal. She had recently been widowed, became destitute, and was publicly denounced by her abusive second husband. Criticizing what he perceived as her restlessness, Willis once made her the subject of his poem “To My Wild Sis”. As Fanny Fern, she had published Fern Leaves, which sold over 100,000 copies the year before. Willis, however, did not encourage his sister’s writings. “You overstrain the pathetic, and your humor runs into dreadful vulgarity sometimes... I am sorry that any editor knows that a sister of mine wrote some of these which you sent me”, he wrote. In 1854 she published Ruth Hall, a Domestic Tale of the Present Time, a barely concealed semi-autobiographical account of her own difficulties in the literary world. Nathaniel Willis was represented as “Hyacinth Ellet”, an effeminate, self-serving editor who schemes to ruin his sister’s prospects as a writer. Willis did not publicly protest but in private he asserted that, despite his fictitious equivalent, he had done his best to support his sister during her difficult times, especially after the death of her first husband.Among his later works, following in his traditional sketches about his life and people he has met, were Hurry-Graphs (1851), Out-Doors at Idlewild (1854), and Ragbag (1855). Willis had complained that his magazine writing prevented him from writing a longer work. He finally had the time in 1856, and he wrote his only novel, Paul Fane, which was published a year later. The character Bosh Blivins, who served as comic relief in the novel, may have been based on painter Chester Harding. His final work was The Convalescent (1859), which included a chapter on his time spent with Washington Irving at Sunnyside. Final years and death In July 1860, Willis took his last major trip. Along with his wife, he stopped in Chicago and Yellow Springs, Ohio, as far west as Madison, Wisconsin, and also took a steamboat down the Mississippi River to St. Louis, Missouri, and returned through Cincinnati, Ohio and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. In 1861, Willis allowed the Home Journal to break its pledge to avoid taking sides in political discussions when the Confederate States of America was established, calling the move a purposeful act to bring on war. On May 28, 1861, Willis was part of a committee of literary figures—including William Cullen Bryant, Charles Anderson Dana, and Horace Greeley—to invite Edward Everett to speak in New York on behalf of maintaining the Union. The Home Journal lost many subscribers during the American Civil War, Morris died in 1864, and the Willis family had to take in boarders and for a time turned Idlewild into a girls’ school for income.Willis was very sick in these final years: he suffered from violent epileptic seizures and, early in November 1866, fainted in the streets, prompting Harriet Jacobs to return to help his wife. Willis died on his 61st birthday, January 20, 1867, and was buried in Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Four days later, the day of his funeral, all bookstores in the city were closed as a token of respect. His pallbearers included Longfellow, James Russell Lowell, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Samuel Gridley Howe, and James Thomas Fields. Reputation Throughout his literary career, Willis was well liked and known for his good nature amongst friends. Well traveled and clever, he had a striking appearance at six feet tall and was typically dressed elegantly. Many, however, remarked that Willis was effeminate, Europeanized, and guilty of “Miss Nancyism”. One editor called him “an impersonal passive verb—a pronoun of the feminine gender”. A contemporary caricature depicted him wearing a fashionable beaver hat and tightly closed coat and carrying a cane, reflecting Willis’s wide reputation as a “dandy”. Willis put considerable effort into his appearance and his fashion sense, presenting himself as a member of an upcoming American aristocracy. As Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. once said, Willis was “something between a remembrance of Count D’Orsay and an anticipation of Oscar Wilde”. Publisher Charles Frederick Briggs once wrote that “Willis was too Willisy”. He described his writings as the “novelty and gossip of the hour” and was not necessarily concerned about facts but with the “material of conversation and speculation, which may be mere rumor, may be the truth”. Willis’s behavior in social groups annoyed fellow poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. “He is too artificial”, Longfellow wrote to his friend George Washington Greene. “And his poetry has now lost one of its greatest charms for me—its sincerity”. E. Burke Fisher, a journalist in Pittsburgh, wrote that “Willis is a kind of national pet and we must regard his faults as we do those of a spoiled stripling, in the hope that he will amend”.Willis built up his reputation in the public at a time when readers were interested in the personal lives of writers. In his writings, he described the “high life” of the “Upper Ten Thousand”, a phrase he coined. His travel writings in particular were popular for this reason as Willis was actually living the life he was describing and recommending to readers. Even so, he manufactured a humble and modest persona, questioned his own literary merit, and purposely used titles, such as Pencillings by the Way and Dashes at Life With Free Pencil, which downplayed their own quality. His informally toned editorials, which covered a variety of topics, were also very successful. Using whimsicality and humor, he was purposely informal to allow his personality to show in his writing. He addressed his readers personally, as if having a private conversation with them. As he once wrote: “We would have you... indulge us in our innocent egotism as if it were all whispered in your private ear and over our iced Margaux”. When women poets were becoming popular in the 1850s, he emulated their style and focused on sentimental and moral subjects.In the publishing world, Willis was known as a shrewd magazinist and an innovator who focused on appealing to readers’ special interests while still recognizing new talent. In fact, Willis became the standard by which other magazinists were judged. According to writer George William Curtis, "His gayety [sic] and his graceful fluency made him the first of our proper 'magazinists’". For a time, it was said that Willis was the “most-talked-about author” in the United States. Poe questioned Willis’s fame, however. “Willis is no genius–a graceful trifler–no more”, he wrote in a letter to James Russell Lowell. “In me, at least, he never excites an emotion.” Minor Southern writer Joseph Beckham Cobb wrote: “No sane person, we are persuaded, can read his poetry”. Future senator Charles Sumner reported: “I find Willis is much laughed at for his sketches”. Even so, most contemporaries recognized how prolific he was as a writer and how much time he put into all of his writings. James Parton said of him: Of all the literary men whom I have ever known, N. P. Willis was the one who took the most pains with his work. It was no very uncommon thing for him to toil over a sentence for an hour; and I knew him one evening to write and rewrite a sentence for two hours before he had got it to his mind. By 1850 and with the publication of Hurry-Graphs, Willis was becoming a forgotten celebrity. In August 1853, future President James A. Garfield discussed Willis’s declining popularity in his diary: “Willis is said to be a licentious man, although an unrivaled poet. How strange that such men should go to ruin, when they might soar perpetually in the heaven of heavens”. After Willis’s death, obituaries reported that he had outlived his fame. One remarked, “the man who withdraws from the whirling currents of active life is speedily forgotten”. This obituary also stated that Americans “will ever remember and cherish Nathaniel P. Willis as one worthy to stand with Fenimore Cooper and Washington Irving”. In 1946, the centennial issue of Town & Country reported that Willis “led a generation of Americans through a gate where weeds gave way to horticulture”. More modern scholars have dismissed Willis’s work as “sentimental prattle” or refer to him only as an obstacle in the progress of his sister as well as Harriet Jacobs. As biographer Thomas N. Baker wrote, Willis is today only referred to as a footnote in relation to other authors. Selected list of works Prose Sketches (1827) Pencillings by the Way (1835) Inklings of Adventure (1836) À l’Abri; or, The Tent Pitched (1839) Loiterings of Travel (1840) The Romance of Travel (1840) American Scenery (2 volumes 1840) Canadian Scenery (2 volumes 1842) Dashes at Life with a Free Pencil (1845) Rural Letters and Other Records of Thoughts at Leisure (1849) People I Have Met (1850) Life Here and There (1850) Hurry-Graphs (1851) Summer Cruise in the Mediterranean (1853) Fun Jottings; or, Laughs I have taken a Pen to (1853) Health Trip to the Tropics (1854) Ephemera (1854) Famous Persons and Places (1854) Out-Doors at Idlewild; or, The Shaping of a Home on the Banks of the Hudson (1855) The Rag Bag. A Collection of Ephemera (1855) Paul Fane; or, Parts of a Life Else Untold. A Novel (1857) The Convalescent (1859)Plays Bianca Visconti; or, The Heart Overtasked. A Tragedy in Five Acts (1839) Tortesa; or, The Userer Matched (1839)Poetry Fugitive Poetry (1829) Melanie and Other Poems (1831) The Sacred Poems of N. P. Willis (1843) Poems of Passion (1843) Lady Jane and Humorous Poems (1844) The Poems, Sacred, Passionate, and Humorous (1868) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nathaniel_Parker_Willis

As a beginner I simply wish to share my experiences in life that have made me who I am; A strong individual, who possesses the ability to accept the worst of losses such as the trust of close friends, a sister's, a mother's, and a lover's. I write to forget, or perhaps, to live in the past where my heart seems to dwell.

David McKee Wright (6 August 1869– 5 February 1928) was an Irish-born poet and journalist, active in New Zealand and Australia. Early life Wright was born at Ballynaskeagh, County Down, Ireland, the second son of Rev. William Wright, D.D. (1837-1899), a Congregational missionary working in Damascus, scholar and author, and his wife Ann (d.1877), née McKee, daughter of the Rev. David McKee, an educationist and author. David Wright was born while his parents were home on furlough and was left with a grandmother (Rebecca McKee) until he was seven years old. Wright was educated at the local Glascar School and then from 1876 in England at Mr Pope’s School and the Crystal Palace School of Engineering, London. New Zealand Wright migrated to New Zealand in 1887 and spent several years as a rabbiter on stations in Central Otago. During this time he wrote in both prose and verse for major provincial newspapers about station life. He studied for the Congregational ministry and Wright studied divinity from 1896 at the University of Otago. Wright had done a lot of private reading, but found that apart from English his education was generally below that of the other students. In 1897 Wright was awarded a Stuart prize for poetry. Wright published four volumes of ballads, Aorangi and other Verses (1896), Station Ballads and other Verses (1897), Wisps of Tussock (1900), and New Zealand Chimes (1900). As a clergyman Wright was liked, but he found the work uncongenial and gave it up for journalism in which he had considerable experience in New Zealand. Wright married Elizabeth Couper at Dunedin on 3 August 1899; a son David was born in 1900, but the marriage failed. Wright joined the New Zealand Mail as parliamentary reporter in 1907. Australia Wright moved to Sydney in 1910 and did a large amount of successful freelance work for the Sun, The Bulletin, and other papers. Wright was editor of the Red Page of The Bulletin 1916–1926 and encouraged many of the rising writers of the time, and continued to do a large amount of writing himself in both prose and verse. Much of this appeared over pen-names such as “Pat O’Maori” and “Mary McCommonwealth” and much was signed with his initials. As Wright grew older his mind turned more and more to the country of his birth, he published his most important volume, An Irish Heart (1918). In 1920 he was awarded the prize for the best poem in commemoration of the visit of the Prince of Wales, and in the same year the Rupert Brooke memorial prize for a long poem, “Gallipoli”. Neither of these poems has been published in book form. From 1912-18 Wright lived with the writer 'Margaret Fane’ (Beatrice Florence Osborne, 1887-1962) in Sydney; they had four sons. From 1918 Wright lived with Zora Cross in Greeanawn, Glenbrook, Blue Mountains. He died there on 5 February 1928. The couple had two daughters, Davidina Wright and April McKee Wright (also known as April Hersey), who went on to write at least one wartime thriller. Legacy Wright was a friend of Christopher Brennan, Randolph Bedford, Frank Morton and Henry Lawson. Though much of a Bohemian, something of the clergyman still clung to him. Zora Cross, in An Introduction to the Study of Australian Literature, gave him a high position among Australian poets. Charming though An Irish Heart may be, it is too derivative to be work of the highest kind. It is not a question of individual words or phrases, but rather of a man steeping himself in the modern Irish school of poetry, and with all the skill of his practised craftsmanship reproducing its spirit in another land. A large amount of his work, including some short plays, has never been collected. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_McKee_Wright

Hi, my names Will I'm 26 years old and live in the North East. I've been writing poetry for about a year so if you have any constructive criticism that would be appreciated ([email protected]). Most of my poems are based on truth or a variation. It all started when I was told I needed to write down how I felt and they just ended up getting written in such a way it could be read as poetry. I don't use punctuation in any of my poems, this isn't for any particular reason, just never thought it was needed. I have a lot more poems written but I am trying to enter competitions and the majority of which do not accept poems that have been broadcast in any way.

i am a 20 year old college student who has been writing poetry since middle school. i'm completely self taught, and hope to publish my own collection of poetry soon! i write about many different topics that interest me and get inspiration from songs, movies, the weather, and real-life experiences.

Hi people! I am here because I love writing poetry. It is one of my passions as well as art, photography and writing. You can find my stories and some of poems on my wattpad too: http://www.wattpad.com/user/WhiteSnowflakes123 You can also find some here: http://whitesnowflakes123.deviantart.com So, my great grandfather was a poet. Poetry runs in the family, although my dad and I are the only ones who really write it. For school projects, I go and re-read my great grandfathers published poetry tips which I find really helpful. I occasionally read his poems again too. My great grandma was an artist. My mum does art for fun as well. Photography, well my uncle does that. You never see him, because he is always in the background. He does a lot of work. He is very skilled and gives me tips all the time. Sometimes we make movies together with my brother. He has met many famous people, mostly football players and their coaches. For example, all the Real Madrid players and their old coach meriño or whatever. So yes, our family is Spanish. He has also met some Barcelona players, I'm pretty sure. Anyways. I'm here for poetry. Please tell me what you think.

I am just trying something new writing has never been in my interests . For some reason I am starting to like the idea of it . I hope to meet people on here I have read some amazing things through out this website and any feedback to what I write I will appreciate it. maybe one day I might be as talented as some of you .

Barry G. Wick worked for many years in the broadcasting and advertising industry. A native of South Dakota, he retired to Coralville, Iowa next to Iowa City in 2014. He writes poetry and some fiction. Most everything he's ever written is unpublished. This poet is available to the whole world free of charge at http://agereasonmistake.blogspot.comm