Sylvia Plath (October 27, 1932 – February 11, 1963) was an American poet, novelist and short story writer. Born in Boston, Massachusetts, she studied at Smith College and Newnham College, Cambridge before receiving acclaim as a professional poet and writer. She married fellow poet Ted Hughes in 1956 and they lived together first in the United States and then England, having two children together: Frieda and Nicholas. Following a long struggle with depression and a marital separation, Plath committed suicide in 1963. Controversy continues to surround the events of her life and death, as well as her writing and legacy. Plath is credited with advancing the genre of confessional poetry and is best known for her two published collections: The Colossus and Other Poems and Ariel. In 1982, she became the first poet to win a Pulitzer Prize posthumously, for The Collected Poems. She also wrote The Bell Jar, a semi-autobiographical novel published shortly before her death.

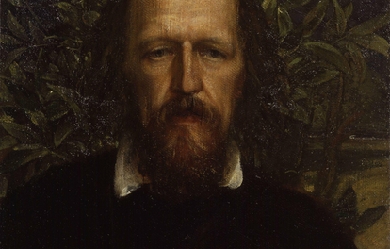

Alfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson, FRS (6 August 1809 – 6 October 1892) was Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom during much of Queen Victoria's reign and remains one of the most popular poets in the English language. A number of phrases from Tennyson’s work have become commonplaces of the English language, including “Nature, red in tooth and claw”, “'Tis better to have loved and lost / Than never to have loved at all”, “Theirs not to reason why, / Theirs but to do and die”, “My strength is as the strength of ten, / Because my heart is pure”, “Knowledge comes, but Wisdom lingers”, and “The old order changeth, yielding place to new”. He is the ninth most frequently quoted writer in The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations.

I'm a highly intelligent, articulate and well-educated human being with an intuitive but enterprising sense of responsibility and a strong moral compass that instinctively demarcates what's right and wrong. Trust, confidentiality and having the courage, regardless of what I do, to formulate and stand by my own personal convictions are key aspects of my life and, unsurprisingly, are also principal characteristics I attach great importance to and naturally expect from those who want to play a meaningful role in my life. I don't suffer fools gladly, in fact not at all and most definitely haven’t got any interest in or time for egotists, time-wasters, attention seekers or the narcissistic. Furthermore, I’m an adult and in my private and professional lives prefer to deal with genuine adults, so anyone who wants to act childishly and thinks they can have any kind of relationship with me, then you’re wrong! And my advice to you in that regard is to go and enrol in a kindergarten as you'll possibly have better luck there. My website is: www.politicoacademic.blogspot.com and my twitter feed if you're interested is: www.twitter.com/DerAkademiker

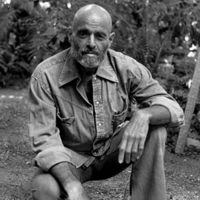

Sheldon Allan Shel Silverstein (September 25, 1930 – May 10, 1999), was an American poet, singer-songwriter, cartoonist, screenwriter, and author of children's books. He styled himself as Uncle Shelby in some works. Translated into more than 30 languages, his books have sold over 20 million copies.

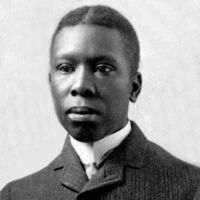

Paul Laurence Dunbar was the first African-American poet to garner national critical acclaim. Born in Dayton, Ohio, in 1872, Dunbar penned a large body of dialect poems, standard English poems, essays, novels and short stories before he died at the age of 33. His work often addressed the difficulties encountered by members of his race and the efforts of African-Americans to achieve equality in America. He was praised both by the prominent literary critics of his time and his literary contemporaries. Dunbar was born on June 27, 1872, to Matilda and Joshua Dunbar, both natives of Kentucky. His mother was a former slave and his father had escaped from slavery and served in the 55th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment and the 5th Massachusetts Colored Cavalry Regiment during the Civil War. Matilda and Joshua had two children before separating in 1874. Matilda also had two children from a previous marriage. The family was poor, and after Joshua left, Matilda supported her children by working in Dayton as a washerwoman. One of the families she worked for was the family of Orville and Wilbur Wright, with whom her son attended Dayton's Central High School. Though the Dunbar family had little material wealth, Matilda, always a great support to Dunbar as his literary stature grew, taught her children a love of songs and storytelling. Having heard poems read by the family she worked for when she was a slave, Matilda loved poetry and encouraged her children to read. Dunbar was inspired by his mother, and he began reciting and writing poetry as early as age 6. Dunbar was the only African-American in his class at Dayton Central High, and while he often had difficulty finding employment because of his race, he rose to great heights in school. He was a member of the debating society, editor of the school paper and president of the school's literary society. He also wrote for Dayton community newspapers. He worked as an elevator operator in Dayton's Callahan Building until he established himself locally and nationally as a writer. He published an African-American newsletter in Dayton, the Dayton Tattler, with help from the Wright brothers. His first public reading was on his birthday in 1892. A former teacher arranged for him to give the welcoming address to the Western Association of Writers when the organization met in Dayton. James Newton Matthews became a friend of Dunbar's and wrote to an Illinois paper praising Dunbar's work. The letter was reprinted in several papers across the country, and the accolade drew regional attention to Dunbar; James Whitcomb Riley, a poet whose works were written almost entirely in dialect, read Matthew's letter and acquainted himself with Dunbar's work. With literary figures beginning to take notice, Dunbar decided to publish a book of poems. Oak and Ivy, his first collection, was published in 1892. Though his book was received well locally, Dunbar still had to work as an elevator operator to help pay off his debt to his publisher. He sold his book for a dollar to people who rode the elevator. As more people came in contact with his work, however, his reputation spread. In 1893, he was invited to recite at the World's Fair, where he met Frederick Douglass, the renowned abolitionist who rose from slavery to political and literary prominence in America. Douglass called Dunbar "the most promising young colored man in America." Dunbar moved to Toledo, Ohio, in 1895, with help from attorney Charles A. Thatcher and psychiatrist Henry A. Tobey. Both were fans of Dunbar's work, and they arranged for him to recite his poems at local libraries and literary gatherings. Tobey and Thatcher also funded the publication of Dunbar's second book, Majors and Minors. It was Dunbar's second book that propelled him to national fame. William Dean Howells, a novelist and widely respected literary critic who edited Harper's Weekly, praised Dunbar's book in one of his weekly columns and launched Dunbar's name into the most respected literary circles across the country. A New York publishing firm, Dodd Mead and Co., combined Dunbar's first two books and published them as Lyrics of a Lowly Life. The book included an introduction written by Howells. In 1897, Dunbar traveled to England to recite his works on the London literary circuit. His national fame had spilled across the Atlantic. After returning from England, Dunbar married Alice Ruth Moore, a young writer, teacher and proponent of racial and gender equality who had a master's degree from Cornell University. Dunbar took a job at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. He found the work tiresome, however, and it is believed the library's dust contributed to his worsening case of tuberculosis. He worked there for only a year before quitting to write and recite full time. In 1902, Dunbar and his wife separated. Depression stemming from the end of his marriage and declining health drove him to a dependence on alcohol, which further damaged his health. He continued to write, however. He ultimately produced 12 books of poetry, four books of short stories, a play and five novels. His work appeared in Harper's Weekly, the Sunday Evening Post, the Denver Post, Current Literature and a number of other magazines and journals. He traveled to Colorado and visited his half-brother in Chicago before returning to his mother in Dayton in 1904. He died there on Feb. 9, 1906. Literary style Dunbar's work is known for its colorful language and a conversational tone, with a brilliant rhetorical structure. These traits were well matched to the tune-writing ability of Carrie Jacobs-Bond (1862–1946), with whom he collaborated. Use of dialect Much of Dunbar's work was authored in conventional English, while some was rendered in African-American dialect. Dunbar remained always suspicious that there was something demeaning about the marketability of dialect poems. One interviewer reported that Dunbar told him, "I am tired, so tired of dialect", though he is also quoted as saying, "my natural speech is dialect" and "my love is for the Negro pieces". Though he credited William Dean Howells with promoting his early success, Dunbar was dismayed by his demand that he focus on dialect poetry. Angered that editors refused to print his more traditional poems, he accused Howells of "[doing] my irrevocable harm in the dictum he laid down regarding my dialect verse." Dunbar, however, was continuing a literary tradition that used Negro dialect; his predecessors included Mark Twain, Joel Chandler Harris, and George Washington Cable. Two brief examples of Dunbar's work, the first in standard English and the second in dialect, demonstrate the diversity of the poet's production: (From "Dreams") What dreams we have and how they fly Like rosy clouds across the sky; Of wealth, of fame, of sure success, Of love that comes to cheer and bless; And how they wither, how they fade, The waning wealth, the jilting jade — The fame that for a moment gleams, Then flies forever, — dreams, ah — dreams! (From "A Warm Day In Winter") "Sunshine on de medders, Greenness on de way; Dat's de blessed reason I sing all de day." Look hyeah! What you axing'? What meks me so merry? 'Spect to see me sighin' W'en hit's wa'm in Febawary? List of works * Oak and Ivy (1892) * Majors and Minors (1896) * Lyrics of Lowly Life (1896) * Folks from Dixie (1898) * The Strength of Gideon (1900) * In Old Plantation Days (1903) * The Heart of Happy Hollow (1904) * Lyrics of Sunshine and Shadow (1905) References Paul Laurence Dunbar Website - www.dunbarsite.org/biopld.asp Wikipedia- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Laurence_Dunbar

Frederic Ogden Nash (August 19, 1902 – May 19, 1971) was an American poet well known for his light verse. At the time of his death in 1971, The New York Times said his “droll verse with its unconventional rhymes made him the country’s best-known producer of humorous poetry”. Nash wrote over 500 pieces of comic verse. The best of his work was published in 14 volumes between 1931 and 1972.

There are much better writers than I Who have written of love, God and philosophy Not much that I can add But my unique life experiences I will stick to what I know and feel In hopes my written word can reach places that I have not Relying more on natural simplicity than technique and form Check out my work at: www.amazon.com/Laura-Alaniz

English Romantic poet John Keats was born on October 31, 1795, in London. The oldest of four children, he lost both his parents at a young age. His father, a livery-stable keeper, died when Keats was eight; his mother died of tuberculosis six years later. After his mother's death, Keats's maternal grandmother appointed two London merchants, Richard Abbey and John Rowland Sandell, as guardians. Abbey, a prosperous tea broker, assumed the bulk of this responsibility, while Sandell played only a minor role. When Keats was fifteen, Abbey withdrew him from the Clarke School, Enfield, to apprentice with an apothecary-surgeon and study medicine in a London hospital. In 1816 Keats became a licensed apothecary, but he never practiced his profession, deciding instead to write poetry.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning (6 March 1806 – 29 June 1861) was one of the most prominent poets of the Victorian era. Her poetry was widely popular in both England and the United States during her lifetime. A collection of her last poems was published by her husband, Robert Browning, shortly after her death. Barrett Browning opposed slavery and published two poems highlighting the barbarity of slavers and her support for the abolitionist cause. The poems opposing slavery include "The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim's Point" and "A Curse for a Nation"; in the first she describes the experience of a slave woman who is whipped, raped, and made pregnant as she curses the slavers. She declared herself glad that the slaves were "virtually free" when the Emancipation Act abolishing slavery in British colonies was passed in 1833, despite the fact that her father believed that Abolitionism would ruin his business.

I am an American Patriot, a Believer, and a lover of God and Country. I am a widow, a mother of five children ❤️ and five grandchildren. ❤️ I’m very proud, and honored to have borne such loving, talented and hard working children. Being a Mother was my destiny. Being a writer is also part of my destiny that I truly thank God for. It’s a gift from God It was after my children were grown and left home that I became serious about writing. I have written a book titled (American Poetry and Music) that has been published by Christian Faith Publishing. Which can be purchased on Amazon.com, Barnes and Noble, and Thrift Books.com I get my inspiration from the Creator, and I go under the heading of H.S.I. Which stands for (Holy Spirit Inspiration) Some of these poems on Poeticous.com appear in my book . I am grateful for them allowing me to publish my poems on this site also. I’ve come to love this site very much. All Poems, and Original Music Videos on this site are my own original compositions, and are covered under U.S.Copyright laws.© 2024. For more info -You can find me on (Youtube) and (Facebook). Email no longer public, but if you message me from Facebook or here on Poeticous I’ll give it to you privately. No copyright infringement intended with any Pictures or videos used on these poetry pages. Some videos of artist I enjoy were obtained from Youtube, and some pictures are from Public Domain sites. Mostly they are the property of Poeticous I do not claim rights for any works except my own Original Work. Thank you, Charlotte B. Williams

Percy Bysshe Shelley (4 August 1792 – 8 July 1822) was one of the major English Romantic poets and is critically regarded as among the finest lyric poets in the English language. Shelley was famous for his association with John Keats and Lord Byron. The novelist Mary Shelley (née Godwin) was his second wife. Shelley's unconventional life and uncompromising idealism, combined with his strong disapproving voice, made him a marginalized figure during his life, important in a fairly small circle of admirers, and opened him to criticism as well as praise afterward.

Clarence Michael James Stanislaus Dennis, better kn (own as C. J. Dennis, (7 September 1876– 22 June 1938) was an Australian poet known for his humorous poems, especially “The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke”, published in the early 20th century. Though Dennis’s work is less well known today, his 1916 publication of The Sentimental Bloke sold 65,000 copies in its first year, and by 1917 he was the most prosperous poet in Australian history. Together with Banjo Paterson and Henry Lawson, both of whom he collaborated with, he is often considered among Australia’s three most famous poets. When he died at the age of 61, the Prime Minister of Australia Joseph Lyons suggested he was destined to be remembered as the “Australian Robert Burns”. Biography C. J. Dennis was born in Auburn, South Australia. His father owned hotels in Auburn, and then later in Gladstone and Laura. His mother suffered ill health, so Clarrie (as he was known) was raised initially by his great-aunts, then went away to school, Christian Brothers College, Adelaide as a teenager. At the age of 19 he was employed as a solicitor’s clerk. It was while he was working in this job that, like banker’s clerk Banjo Paterson before him, his first poem was published under the pseudonym “The Best of the Six”. He later went on to publish in The Worker, under his own name, and as “Den”, and in The Bulletin. His collected poetry was published by Angus & Robertson. He joined the literary staff of The Critic in 1897, and after a spell doing odd jobs around Broken Hill, returned to The Critic, serving for a time c. 1904 as editor, to be succeeded by Conrad Eitel. He founded a short-lived literary paper The Gadfly. From 1922 he served as staff poet on the Melbourne Herald. C. J. Dennis is buried in Box Hill Cemetery, Melbourne. The Box Hill Historical Society has attached a commemorative plaque to the gravestone. Dennis is also commemorated with a plaque on Circular Quay in Sydney which forms part of the NSW Ministry for the Arts - Writers Walk series, and by a bust outside the town hall of the town of Laura. Books * Backblock Ballads and Other Verses (1913) * The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke (1915) * The Moods of Ginger Mick (1916) * The Glugs of Gosh (1917) * Doreen (1917) * Digger Smith (1918) * Backblock Ballads and Later Verses (1918) * Jim of the Hills (1919) * A Book for Kids (1921) (reissued as Roundabout, 1935) * Rose of Spadgers (1924) * The Singing Garden (1935) Shorter poems of note “The Austra-laise” (1908) Many shorter works were also published in a wide variety of Australian newspapers and magazines. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/C._J._Dennis

I am very passionate about writing especially poetry because it speaks to my soul. I'm looking forward to become a professional writer someday and get published. I want to share my writing talent worldwide and I won't stop until I do. While I'm here at "Poeticous". I would like to receive honest feedback on my writings, but I can see people don't really comment, they only view. So what's the point of Poet's like myself sharing our poetry? if no one is willing to comment. Also, they may like the poem but refuse to press the "like" button..........I just don't understand that!!!

Carl Sandburg was born in Galesburg, Illinois, on January 6, 1878. His parents, August and Clara Johnson, had emigrated to America from the north of Sweden. After encountering several August Johnsons in his job for the railroad, the Sandburg's father renamed the family. The Sandburgs were very poor; Carl left school at the age of thirteen to work odd jobs, from laying bricks to dishwashing, to help support his family. At seventeen, he traveled west to Kansas as a hobo. He then served eight months in Puerto Rico during the Spanish-American war. While serving, Sandburg met a student at Lombard College, the small school located in Sandburg's hometown. The young man convinced Sandburg to enroll in Lombard after his return from the war.

Madison Julius Cawein (March 23, 1865 – December 8, 1914) was a poet from Louisville, Kentucky. He was the fifth child of William and Christiana (Stelsly) Cawein. His father made patent medicines from herbs thus, as a child, Cawein became acquainted with and developed a love for local nature.

Robert Burns (25 January 1759 – 21 July 1796) (also known as Rabbie Burns, Scotland's favourite son, the Ploughman Poet, Robden of Solway Firth, the Bard of Ayrshire and in Scotland as simply The Bard) was a Scottish poet and a lyricist. He is widely regarded as the national poet of Scotland, and is celebrated worldwide. He is the best known of the poets who have written in the Scots language, although much of his writing is also in English and a “light” Scots dialect, accessible to an audience beyond Scotland. He also wrote in standard English, and in these his political or civil commentary is often at its most blunt.

Love is the essence of pure thought. There is nowhere that this thought is not. I grew up in a small town in Oklahoma, just beyond the outskirts of several gypsum plateaus, miles of desert sand and vast horizons. I would go out into fields of sunflowers with my pen and paper, watching the currents of wind moving through miles and miles of wheat to write about the lucid imagery I would see when I closed my eyes, the experiences of coming out in a conservative community and finding my way as an artist in a place that did not nurture the arts. Words have always been my primary way to sort out my experiences into streams of consciousness that act as a form of self-discovery. Called by the overwhelming pull to follow my dreams, I relocated to the Catskills to follow my passions and put every idea into motion. I am currently working on several video projects, performances in several venues, live music, Sparkle Poetic radio ads, and many new things that you can keep up with on my website below. Welcome to the realm of words. Love is real. www.sparklepoetics.com

Joseph Rudyard Kipling (30 December 1865 – 18 January 1936) was an English novelist, short-story writer, poet, and journalist. He was born in British India, which inspired much of his work. Kipling was one of the most popular writers in England, in both prose and verse, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Henry James said: “Kipling strikes me personally as the most complete man of genius (as distinct from fine intelligence) that I have ever known.”

I am a 27-year-old Christian (the modern term for Follower of the Way). Some bands that I've drawn inspiration from include Demon Hunter, Skillet, Disturbed, Breaking Benjamin, All That Remains and War of Ages. I write lyrical poems, which I have been writing since I was 12 years old. A lot of my lyrics are based on life views and experiences, as well as struggles regarding my Christian faith. I am not ashamed and I will not shy away from admitting to my faith. I hope that my lyrics might open up solutions to readers that can relate to my lyrics. Thank you and God bless.

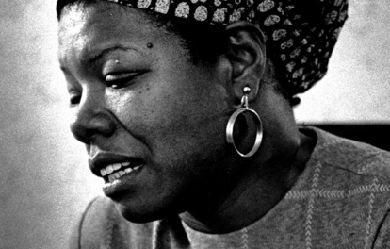

Maya Angelou (born Marguerite Ann Johnson; April 4, 1928 – May 28, 2014) was an American author and poet. She published seven autobiographies, three books of essays, and several books of poetry, and is credited with a list of plays, movies, and television shows spanning more than fifty years. She received dozens of awards and over thirty honorary doctoral degrees. Angelou is best known for her series of seven autobiographies, which focus on her childhood and early adult experiences. The first, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings (1969), tells of her life up to the age of seventeen, and brought her international recognition and acclaim. Angelou's long list of occupations has included pimp, prostitute, night-club dancer and performer, cast-member of the musical Porgy and Bess, coordinator for Martin Luther King, Jr.'s Southern Christian Leadership Conference, author, journalist in Egypt and Ghana during the days of decolonization, and actor, writer, director, and producer of plays, movies, and public television programs.