Info

I am a 27-year-old Christian (the modern term for Follower of the Way). Some bands that I've drawn inspiration from include Demon Hunter, Skillet, Disturbed, Breaking Benjamin, All That Remains and War of Ages. I write lyrical poems, which I have been writing since I was 12 years old. A lot of my lyrics are based on life views and experiences, as well as struggles regarding my Christian faith. I am not ashamed and I will not shy away from admitting to my faith. I hope that my lyrics might open up solutions to readers that can relate to my lyrics. Thank you and God bless.

Robert Burns (25 January 1759 – 21 July 1796) (also known as Rabbie Burns, Scotland's favourite son, the Ploughman Poet, Robden of Solway Firth, the Bard of Ayrshire and in Scotland as simply The Bard) was a Scottish poet and a lyricist. He is widely regarded as the national poet of Scotland, and is celebrated worldwide. He is the best known of the poets who have written in the Scots language, although much of his writing is also in English and a “light” Scots dialect, accessible to an audience beyond Scotland. He also wrote in standard English, and in these his political or civil commentary is often at its most blunt.

Welcome to my poetry page, I think its a blast, Some of my Poetry is about my past. Lots of wonderful words are written and funny, I don't get paid so it wont cost you money. My poems are of the wonders of life someone said I have written about the dead. Some people may be offended by some of my rhymes, So if your offended don't come back to read next time. But if my poetry makes you laugh please come back, Because this Yorkshire man has a sense of humour and can be really daft.

Robert Laurence Binyon, CH (10 August 1869– 10 March 1943) was an English poet, dramatist and art scholar. His most famous work, For the Fallen, is well known for being used in Remembrance Sunday services. Pre-war life Laurence Binyon was born in Lancaster, Lancashire, England. His parents were Frederick Binyon, and Mary Dockray. Mary’s father, Robert Benson Dockray, was the main engineer of the London and Birmingham Railway. The family were Quakers. Binyon studied at St Paul’s School, London. Then he read Classics (Honour Moderations) at Trinity College, Oxford, where he won the Newdigate Prize for poetry in 1891. Immediately after graduating in 1893, Binyon started working for the Department of Printed Books of the British Museum, writing catalogues for the museum and art monographs for himself. In 1895 his first book, Dutch Etchers of the Seventeenth Century, was published. In that same year, Binyon moved into the Museum’s Department of Prints and Drawings, under Campbell Dodgson. In 1909, Binyon became its Assistant Keeper, and in 1913 he was made the Keeper of the new Sub-Department of Oriental Prints and Drawings. Around this time he played a crucial role in the formation of Modernism in London by introducing young Imagist poets such as Ezra Pound, Richard Aldington and H.D. to East Asian visual art and literature. Many of Binyon’s books produced while at the Museum were influenced by his own sensibilities as a poet, although some are works of plain scholarship– such as his four-volume catalogue of all the Museum’s English drawings, and his seminal catalogue of Chinese and Japanese prints. In 1904 he married historian Cicely Margaret Powell, and the couple had three daughters. During those years, Binyon belonged to a circle of artists, as a regular patron of the Wiener Cafe of London. His fellow intellectuals there were Ezra Pound, Sir William Rothenstein, Walter Sickert, Charles Ricketts, Lucien Pissarro and Edmund Dulac. Binyon’s reputation before the war was such that, on the death of the Poet Laureate Alfred Austin in 1913, Binyon was among the names mentioned in the press as his likely successor (others named included Thomas Hardy, John Masefield and Rudyard Kipling; the post went to Robert Bridges). For the Fallen Moved by the opening of the Great War and the already high number of casualties of the British Expeditionary Force, in 1914 Laurence Binyon wrote his For the Fallen, with its Ode of Remembrance, as he was visiting the cliffs on the north Cornwall coast, either at Polzeath or at Portreath (at each of which places there is a plaque commemorating the event, though Binyon himself mentioned Polzeath in a 1939 interview. The confusion may be related to Porteath Farm being near Polzeath). The piece was published by The Times newspaper in September, when public feeling was affected by the recent Battle of Marne. Today Binyon’s most famous poem, For the Fallen, is often recited at Remembrance Sunday services in the UK; is an integral part of Anzac Day services in Australia and New Zealand and of the 11 November Remembrance Day services in Canada. The third and fourth verses of the poem (although often just the fourth) have thus been claimed as a tribute to all casualties of war, regardless of nation. They went with songs to the battle, they were young. Straight of limb, true of eyes, steady and aglow. They were staunch to the end against odds uncounted, They fell with their faces to the foe. They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old: Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn. At the going down of the sun and in the morning, We will remember them. They mingle not with their laughing comrades again; They sit no more at familiar tables of home; They have no lot in our labour of the day-time; They sleep beyond England’s foam Three of Binyon’s poems, including “For the Fallen”, were set by Sir Edward Elgar in his last major orchestra/choral work, The Spirit of England. In 1915, despite being too old to enlist in the First World War, Laurence Binyon volunteered at a British hospital for French soldiers, Hôpital Temporaire d’Arc-en-Barrois, Haute-Marne, France, working briefly as a hospital orderly. He returned in the summer of 1916 and took care of soldiers taken in from the Verdun battlefield. He wrote about his experiences in For Dauntless France (1918) and his poems, “Fetching the Wounded” and “The Distant Guns”, were inspired by his hospital service in Arc-en-Barrois. Artists Rifles, a CD audiobook published in 2004, includes a reading of For the Fallen by Binyon himself. The recording itself is undated and appeared on a 78 rpm disc issued in Japan. Other Great War poets heard on the CD include Siegfried Sassoon, Edmund Blunden, Robert Graves, David Jones and Edgell Rickword. Post-war life After the war, he returned to the British Museum and wrote numerous books on art; in particular on William Blake, Persian art, and Japanese art. His work on ancient Japanese and Chinese cultures offered strongly contextualised examples that inspired, among others, the poets Ezra Pound and W. B. Yeats. His work on Blake and his followers kept alive the then nearly-forgotten memory of the work of Samuel Palmer. Binyon’s duality of interests continued the traditional interest of British visionary Romanticism in the rich strangeness of Mediterranean and Oriental cultures. In 1931, his two volume Collected Poems appeared. In 1932, Binyon rose to be the Keeper of the Prints and Drawings Department, yet in 1933 he retired from the British Museum. He went to live in the country at Westridge Green, near Streatley (where his daughters also came to live during the Second World War). He continued writing poetry. In 1933–1934, Binyon was appointed Norton Professor of Poetry at Harvard University. He delivered a series of lectures on The Spirit of Man in Asian Art, which were published in 1935. Binyon continued his academic work: in May 1939 he gave the prestigious Romanes Lecture in Oxford on Art and Freedom, and in 1940 he was appointed the Byron Professor of English Literature at University of Athens. He worked there until forced to leave, narrowly escaping the German invasion of Greece in April 1941 . He was succeeded by Lord Dunsany, who held the chair in 1940-1941. Binyon had been friends with Ezra Pound since around 1909, and in the 1930s the two became especially close; Pound affectionately called him “BinBin”, and assisted Binyon with his translation of Dante. Another protégé was Arthur Waley, whom Binyon employed at the British Museum. Between 1933 and 1943, Binyon published his acclaimed translation of Dante’s Divine Comedy in an English version of terza rima, made with some editorial assistance by Ezra Pound. Its readership was dramatically increased when Paolo Milano selected it for the “The Portable Dante” in Viking’s Portable Library series. Binyon significantly revised his translation of all three parts for the project, and the volume went through three major editions and eight printings (while other volumes in the same series went out of print) before being replaced by the Mark Musa translation in 1981. At his death he was also working on a major three-part Arthurian trilogy, the first part of which was published after his death as The Madness of Merlin (1947). He died in Dunedin Nursing Home, Bath Road, Reading, on 10 March 1943 after an operation. A funeral service was held at Trinity College Chapel, Oxford, on 13 March 1943. There is a slate memorial in St. Mary’s Church, Aldworth, where Binyon’s ashes were scattered. On 11 November 1985, Binyon was among 16 Great War poets commemorated on a slate stone unveiled in Westminster Abbey’s Poets’ Corner. The inscription on the stone quotes a fellow Great War poet, Wilfred Owen. It reads: “My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity.” Daughters His three daughters Helen, Margaret and Nicolete became artists. Helen Binyon (1904–1979) studied with Paul Nash and Eric Ravilious, illustrating many books for the Oxford University Press, and was also a marionettist. She later taught puppetry and published Puppetry Today (1966) and Professional Puppetry in England (1973). Margaret Binyon wrote children’s books, which were illustrated by Helen. Nicolete, as Nicolete Gray, was a distinguished calligrapher and art scholar. Bibliography of key works Poems and verse * Lyric Poems (1894) * Porphyrion and other Poems (1898) * Odes (1901) * Death of Adam and Other Poems (1904) * London Visions (1908) * England and Other Poems (1909) * “For The Fallen”, The Times, 21 September 1914 * Winnowing Fan (1914) * The Anvil (1916) * The Cause (1917) * The New World: Poems (1918) * The Idols (1928) * Collected Poems Vol 1: London Visions, Narrative Poems, Translations. (1931) * Collected Poems Vol 2: Lyrical Poems. (1931) * The North Star and Other Poems (1941) * The Burning of the Leaves and Other Poems (1944) * The Madness of Merlin (1947) In 1915 Cyril Rootham set “For the Fallen” for chorus and orchestra, first performed in 1919 by the Cambridge University Musical Society conducted by the composer. Edward Elgar set to music three of Binyon’s poems ("The Fourth of August", “To Women”, and “For the Fallen”, published within the collection “The Winnowing Fan”) as The Spirit of England, Op. 80, for tenor or soprano solo, chorus and orchestra (1917). English arts and myth * Dutch Etchers of the Seventeenth Century (1895), Binyon’s first book on painting * John Crone and John Sell Cotman (1897) * William Blake: Being all his Woodcuts Photographically Reproduced in Facsimile (1902) * English Poetry in its relation to painting and the other arts (1918) * Drawings and Engravings of William Blake (1922) * Arthur: A Tragedy (1923) * The Followers of William Blake (1925) * The Engraved Designs of William Blake (1926) * Landscape in English Art and Poetry (1931) * English Watercolours (1933) * Gerard Hopkins and his influence (1939) * Art and freedom. (The Romanes lecture, delivered 25 May 1939). Oxford: The Clarendon press, (1939) Japanese and Persian arts * Painting in the Far East (1908) * Japanese Art (1909) * Flight of the Dragon (1911) * The Court Painters of the Grand Moguls (1921) * Japanese Colour Prints (1923) * The Poems of Nizami (1928) (Translation) * Persian Miniature Painting (1933) * The Spirit of Man in Asian Art (1936) Autobiography * For Dauntless France (1918) (War memoir) Biography * Botticelli (1913) * Akbar (1932) Stage plays * Brief Candles A verse-drama about the decision of Richard III to dispatch his two nephews * “Paris and Oenone”, 1906 * Godstow Nunnery: Play * Boadicea; A Play in eight Scenes * Attila: a Tragedy in Four Acts * Ayuli: a Play in three Acts and an Epilogue * Sophro the Wise: a Play for Children * (Most of the above were written for John Masefield’s theatre). * Charles Villiers Stanford wrote incidental music for Attila in 1907. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laurence_Binyon

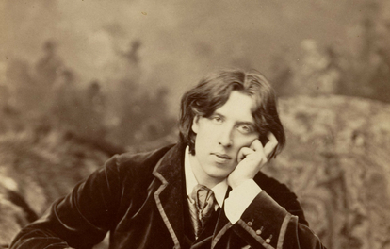

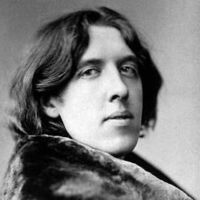

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 1854 – 30 November 1900) was an Irish writer and poet. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of London's most popular playwrights in the early 1890s. Today he is remembered for his epigrams, plays and the circumstances of his imprisonment, followed by his early death. At the turn of the 1890s, he refined his ideas about the supremacy of art in a series of dialogues and essays, and incorporated themes of decadence, duplicity, and beauty into his only novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890). The opportunity to construct aesthetic details precisely, and combine them with larger social themes, drew Wilde to write drama. He wrote Salome (1891) in French in Paris but it was refused a licence. Unperturbed, Wilde produced four society comedies in the early 1890s, which made him one of the most successful playwrights of late Victorian London.

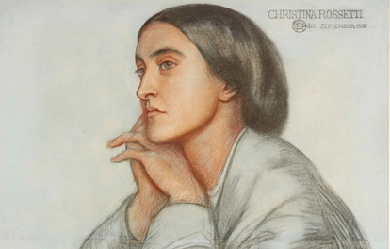

In 1830, Christina Rossetti was born in London, one of four children of Italian parents. Her father was the poet Gabriele Rossetti; her brother Dante Gabriel Rossetti also became a poet and a painter. Rossetti’s first poems were written in 1842 and printed in the private press of her grandfather. In 1850, under the pseudonym Ellen Alleyne, she contributed seven poems to the Pre-Raphaelite journal The Germ, which had been founded by her brother William Michael and his friends.

Hello. My name is Mike. I'm a 30something turning 102 this year. I'm the father to an amazing little girl who I'm unable to see as much as I would like, because I was unable to save her from a lifetime of pain. On this page you'll hear me drone on about topics such as this, being a victim of partners and parents with personality disorders, OCD, PTSD, suicidal ideation, and the occasional nonsensical poem about a snail or a garden gnome. There are horrible people in the world, and many of them are inescapable, and most of you would not believe the chaotic hell my life has led me through. But I have always tried to be the sort of person who I wish others would be. It's so much harder to be a bad person than a good person. Given the issues in my life, I might suffer hazards that would prevent me from furthering this message, so let me attempt to do so here. Be a good person. Know that nothing you do will ever change the world, and that all the help you give to others will ultimately be pointless. But that shouldn't stop you from trying to be the best person you can be. Live as altruistically and conscientiously towards others as possible. Hold open doors, be humble, apologize, offer help. If you see someone in need, don't wait for someone else to come along, because they might not. If you see a need, fill a need. Treat others with kindness and fairness, empathy and equity. If you hurt someone, find out how you can prevent yourself from doing so again in the future. Let people in when you're driving, spare some change to panhandlers, defend kids and animals when you see they're in trouble. The meaning of life is progress. Without growth, there can only be decay. It's too late for humanity as a species, but if everyone reading this could just try a little harder, maybe life wouldn't have to be so unfair. I want to take the time to thank those who follow me directly, as well as those who view my poems in passing. It does not go undetected or unappreciated, truly. Thank you for your support. I hope you all find whatever you’re looking for.

Anne Sexton (November 9, 1928, Newton, Massachusetts – October 4, 1974, Weston, Massachusetts) was an American poetese, known for her highly personal, confessional verse. She won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry in 1967. Themes of her poetry include her suicidal tendencies, long battle against depression and various intimate details from her private life, including her relationships with her husband and children. Sexton suffered from severe mental illness for much of her life, her first manic episode taking place in 1954.

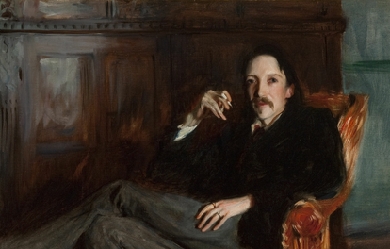

Robert Louis Balfour Stevenson (13 November 1850 – 3 December 1894) was a Scottish novelist, poet, essayist and travel writer. His best-known books include Treasure Island, Kidnapped, and Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. A literary celebrity during his lifetime, Stevenson now ranks among the 26 most translated authors in the world. He has been greatly admired by many authors, including Jorge Luis Borges, Ernest Hemingway, Rudyard Kipling, Marcel Schwob, Vladimir Nabokov, J. M. Barrie, and G. K. Chesterton, who said of him that he “seemed to pick the right word up on the point of his pen, like a man playing spillikins”.

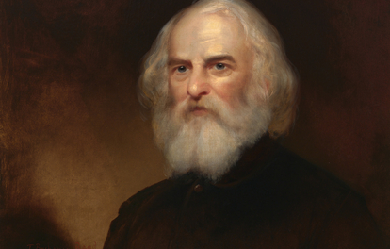

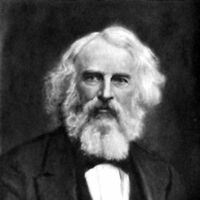

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (February 27, 1807 – March 24, 1882) was an American poet and educator whose works include "Paul Revere's Ride", The Song of Hiawatha, and Evangeline. He was also the first American to translate Dante Alighieri's The Divine Comedy and was one of the five Fireside Poets. Longfellow was born in Portland, Maine, then part of Massachusetts, and studied at Bowdoin College. After spending time in Europe he became a professor at Bowdoin and, later, at Harvard College. His first major poetry collections were Voices of the Night (1839) and Ballads and Other Poems (1841). Longfellow retired from teaching in 1854 to focus on his writing, living the remainder of his life in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in a former headquarters of George Washington. His first wife, Mary Potter, died in 1835 after a miscarriage. His second wife, Frances Appleton, died in 1861 after sustaining burns from her dress catching fire. After her death, Longfellow had difficulty writing poetry for a time and focused on his translation. He died in 1882.

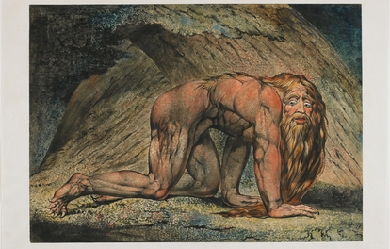

William Blake (28 November 1757 – 12 August 1827) was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his lifetime, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of both the poetry and visual arts of the Romantic Age. His prophetic poetry has been said to form “what is in proportion to its merits the least read body of poetry in the English language”. His visual artistry has led one contemporary art critic to proclaim him “far and away the greatest artist Britain has ever produced”. Although he lived in London his entire life except for three years spent in Felpham he produced a diverse and symbolically rich corpus, which embraced the imagination as “the body of God”, or “Human existence itself”.

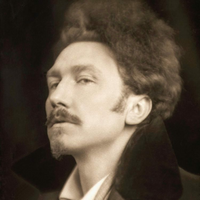

Ezra Weston Loomis Pound (30 October 1885 – 1 November 1972) was an American expatriate poet, critic and a major figure of the early modernist movement. His contribution to poetry began with his promotion of Imagism, a movement that derived its technique from classical Chinese and Japanese poetry, stressing clarity, precision and economy of language. His best-known works include Ripostes (1912), Hugh Selwyn Mauberley (1920), and his unfinished 120-section epic, The Cantos (1917–1969). Working in London in the early 20th century as foreign editor of several American literary magazines, Pound helped to discover and shape the work of contemporaries such as T. S. Eliot, James Joyce, Robert Frost, and Ernest Hemingway. He was responsible for the publication in 1915 of Eliot's “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” and for the serialization from 1918 of Joyce's Ulysses. Hemingway wrote of him in 1925: “He defends [his friends] when they are attacked, he gets them into magazines and out of jail. ... He writes articles about them. He introduces them to wealthy women. He gets publishers to take their books. He sits up all night with them when they claim to be dying... he advances them hospital expenses and dissuades them from suicide.”

I was born in Hamilton, Ohio, in 1925, a confession that I am an old geezer. I served in the infantry during World War II, was wounded and discharged in 1946. I then obtained a B.A. degree with honors in English in 1949. Subsequently I taught in Cincinnati public schools and at the University of Cincinnati for the next 35 years. My poetry has appeared in: * Wall Street Journal * Hellas * Lyric * Envoi * Midwest Poetry Review (a sonnet won awards) * Aethlon * Light * Poet's View * Classical Outlook * Mind over Matter Several books have been self-published but Wormwood and Whines, a compilation of many of my poems, was published by Superior Books in 1999.

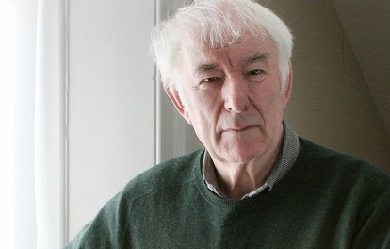

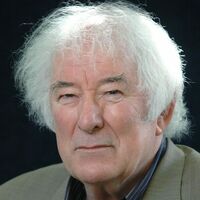

Seamus Justin Heaney (13 April 1939 – 30 August 2013) was an Irish poet, playwright and translator. He received the 1995 Nobel Prize in Literature. Among his best-known works is Death of a Naturalist (1966), his first major published volume. Heaney was and is still recognised as one of the principal contributors to poetry in Ireland during his lifetime. American poet Robert Lowell described him as “the most important Irish poet since Yeats”, and many others, including the academic John Sutherland, have said that he was “the greatest poet of our age”. Robert Pinsky has stated that “with his wonderful gift of eye and ear Heaney has the gift of the story-teller.” Upon his death in 2013, The Independent described him as “probably the best-known poet in the world”.

_and_brother_Ronald_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

George MacDonald (10 December 1824– 18 September 1905) was a Scottish author, poet, and Christian minister. He was a pioneering figure in the field of fantasy literature and the mentor of fellow writer Lewis Carroll. His writings have been cited as a major literary influence by many notable authors including W. H. Auden, C. S. Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien, Walter de la Mare, E. Nesbit and Madeleine L’Engle. C. S. Lewis wrote that he regarded MacDonald as his “master”: “Picking up a copy of Phantastes one day at a train-station bookstall, I began to read. A few hours later,” said Lewis, “I knew that I had crossed a great frontier.” G. K. Chesterton cited The Princess and the Goblin as a book that had “made a difference to my whole existence”. Elizabeth Yates wrote of Sir Gibbie, “It moved me the way books did when, as a child, the great gates of literature began to open and first encounters with noble thoughts and utterances were unspeakably thrilling.” Even Mark Twain, who initially disliked MacDonald, became friends with him, and there is some evidence that Twain was influenced by MacDonald. Christian author Oswald Chambers (1874–1917) wrote in Christian Disciplines, vol. 1, (pub. 1934) that “it is a striking indication of the trend and shallowness of the modern reading public that George MacDonald’s books have been so neglected”. In addition to his fairy tales, MacDonald wrote several works on Christian apologetics including several that defended his view of Christian Universalism. Early life George MacDonald was born on 10 December 1824 at Huntly, Aberdeenshire, Scotland. His father, a farmer, was one of the MacDonalds of Glen Coe, and a direct descendant of one of the families that suffered in the massacre of 1692. The Doric dialect of the Aberdeenshire area appears in the dialogue of some of his non-fantasy novels. MacDonald grew up in the Congregational Church, with an atmosphere of Calvinism. But MacDonald never felt comfortable with some aspects of Calvinist doctrine; indeed, legend has itt that when the doctrine of predestination was first explained to him, he burst into tears (although assured that he was one of the elect). Later novels, such as Robert Falconer and Lilith, show a distaste for the idea that God’s electing love is limited to some and denied to others. MacDonald graduated from the University of Aberdeen, and then went to London, studying at Highbury College for the Congregational ministry. In 1850 he was appointed pastor of Trinity Congregational Church, Arundel, but his sermons (preaching God’s universal love and the possibility that none would, ultimately, fail to unite with God) met with little favour and his salary was cut in half. Later he was engaged in ministerial work in Manchester. He left that because of poor health, and after a short sojourn in Algiers he settled in London and taught for some time at the University of London. MacDonald was also for a time editor of Good Words for the Young, and lectured successfully in the United States during 1872–1873. Work George MacDonald’s best-known works are Phantastes, The Princess and the Goblin, At the Back of the North Wind, and Lilith, all fantasy novels, and fairy tales such as “The Light Princess”, “The Golden Key”, and “The Wise Woman”. “I write, not for children,” he wrote, “but for the child-like, whether they be of five, or fifty, or seventy-five.” MacDonald also published some volumes of sermons, the pulpit not having proved an unreservedly successful venue. MacDonald also served as a mentor to Lewis Carroll (the pen-name of Rev. Charles Lutwidge Dodgson); it was MacDonald’s advice, and the enthusiastic reception of Alice by MacDonald’s many sons and daughters, that convinced Carroll to submit Alice for publication. Carroll, one of the finest Victorian photographers, also created photographic portraits of several of the MacDonald children. MacDonald was also friends with John Ruskin and served as a go-between in Ruskin’s long courtship with Rose La Touche. MacDonald was acquainted with most of the literary luminaries of the day; a surviving group photograph shows him with Tennyson, Dickens, Wilkie Collins, Trollope, Ruskin, Lewes, and Thackeray. While in America he was a friend of Longfellow and Walt Whitman. In 1877 he was given a civil list pension. From 1879 he and his family moved to Bordighera in a place much loved by British expatriates, the Riviera dei Fiori in Liguria, Italy, almost on the French border. In that locality there also was an Anglican Church, which he attended. Deeply enamoured of the Riviera, he spent there 20 years, writing almost half of his whole literary production, especially the fantasy work. In that Ligurian town MacDonald founded a literary studio named Casa Coraggio (Bravery House), which soon became one of the most renowned cultural centres of that period, well attended by British and Italian travellers, and by locals. In that house representations were often held of classic plays, and readings were given of Dante and Shakespeare. In 1900 he moved into St George’s Wood, Haslemere, a house designed for him by his son, Robert Falconer MacDonald, and the building overseen by his eldest son, Greville MacDonald. He died on 18 September 1905 in Ashtead, (Surrey). He was cremated and his ashes buried in Bordighera, in the English cemetery, along with his wife Louisa and daughters Lilia and Grace. As hinted above, MacDonald’s use of fantasy as a literary medium for exploring the human condition greatly influenced a generation of such notable authors as C. S. Lewis (who featured him as a character in his The Great Divorce), J. R. R. Tolkien, and Madeleine L’Engle. MacDonald’s non-fantasy novels, such as Alec Forbes, had their influence as well; they were among the first realistic Scottish novels, and as such MacDonald has been credited with founding the “kailyard school” of Scottish writing. His son Greville MacDonald became a noted medical specialist, a pioneer of the Peasant Arts movement, and also wrote numerous fairy tales for children. Greville ensured that new editions of his father’s works were published. Another son, Ronald MacDonald, was also a novelist. Ronald’s son, Philip MacDonald, (George MacDonald’s grandson) became a very well known Hollywood screenwriter. Theology MacDonald rejected the doctrine of penal substitutionary atonement as developed by John Calvin, which argues that Christ has taken the place of sinners and is punished by the wrath of God in their place, believing that in turn it raised serious questions about the character and nature of God. Instead, he taught that Christ had come to save people from their sins, and not from a Divine penalty for their sins. The problem was not the need to appease a wrathful God but the disease of cosmic evil itself. George MacDonald frequently described the Atonement in terms similar to the Christus Victor theory. MacDonald posed the rhetorical question, “Did he not foil and slay evil by letting all the waves and billows of its horrid sea break upon him, go over him, and die without rebound—spend their rage, fall defeated, and cease? Verily, he made atonement!” MacDonald was convinced that God does not punish except to amend, and that the sole end of His greatest anger is the amelioration of the guilty. As the doctor uses fire and steel in certain deep-seated diseases, so God may use hell-fire if necessary to heal the hardened sinner. MacDonald declared, “I believe that no hell will be lacking which would help the just mercy of God to redeem his children.” MacDonald posed the rhetorical question, “When we say that God is Love, do we teach men that their fear of Him is groundless?” He replied, “No. As much as they fear will come upon them, possibly far more.... The wrath will consume what they call themselves; so that the selves God made shall appear.” However, true repentance, in the sense of freely chosen moral growth, is essential to this process, and, in MacDonald’s optimistic view, inevitable for all beings (see universal reconciliation). He recognised the theoretical possibility that, bathed in the eschatological divine light, some might perceive right and wrong for what they are but still refuse to be transfigured by operation of God’s fires of love, but he did not think this likely. In this theology of divine punishment, MacDonald stands in opposition to Augustine of Hippo, and in agreement with the Greek Church Fathers Clement of Alexandria, Origen, and St. Gregory of Nyssa, although it is unknown whether MacDonald had a working familiarity with Patristics or Eastern Orthodox Christianity. At least an indirect influence is likely, because F. D. Maurice, who influenced MacDonald, knew the Greek Fathers, especially Clement, very well. MacDonald states his theological views most distinctly in the sermon Justice found in the third volume of Unspoken Sermons. In his introduction to George MacDonald: An Anthology, C. S. Lewis speaks highly of MacDonald’s theology: “This collection, as I have said, was designed not to revive MacDonald’s literary reputation but to spread his religious teaching. Hence most of my extracts are taken from the three volumes of Unspoken Sermons. My own debt to this book is almost as great as one man can owe to another: and nearly all serious inquirers to whom I have introduced it acknowledge that it has given them great help—sometimes indispensable help toward the very acceptance of the Christian faith. ... I know hardly any other writer who seems to be closer, or more continually close, to the Spirit of Christ Himself. Hence his Christ-like union of tenderness and severity. Nowhere else outside the New Testament have I found terror and comfort so intertwined.... In making this collection I was discharging a debt of justice. I have never concealed the fact that I regarded him as my master; indeed I fancy I have never written a book in which I did not quote from him. But it has not seemed to me that those who have received my books kindly take even now sufficient notice of the affiliation. Honesty drives me to emphasize it.” Bibliography Fantasy * Phantastes: A Fairie Romance for Men and Women (1858) * “Cross Purposes” (1862) * Adela Cathcart (1864), containing “The Light Princess”, “The Shadows”, and other short stories * The Portent: A Story of the Inner Vision of the Highlanders, Commonly Called “The Second Sight” (1864) * Dealings with the Fairies (1867), containing “The Golden Key”, “The Light Princess”, “The Shadows”, and other short stories * At the Back of the North Wind (1871) * Works of Fancy and Imagination (1871), including Within and Without, “Cross Purposes”, “The Light Princess”, “The Golden Key”, and other works * The Princess and the Goblin (1872) * The Wise Woman: A Parable (1875) (Published also as “The Lost Princess: A Double Story”; or as “A Double Story”.) * The Gifts of the Child Christ and Other Tales (1882; republished as Stephen Archer and Other Tales) * The Day Boy and the Night Girl (1882) * The Princess and Curdie (1883), a sequel to The Princess and the Goblin * The Flight of the Shadow (1891) * Lilith: A Romance (1895) Realistic fiction * David Elginbrod (1863; republished as The Tutor’s First Love), originally published in three volumes * Alec Forbes of Howglen (1865; republished as The Maiden’s Bequest) * Annals of a Quiet Neighbourhood (1867) * Guild Court: A London Story (1868) * Robert Falconer (1868; republished as The Musician’s Quest) * The Seaboard Parish (1869), a sequel to Annals of a Quiet Neighbourhood * Ranald Bannerman’s Boyhood (1871) * Wilfrid Cumbermede (1871–72) * The Vicar’s Daughter (1871–72), a sequel to Annals of a Quiet Neighborhood and The Seaboard Parish * The History of Gutta Percha Willie, the Working Genius (1873), usually called simply Gutta Percha Willie * Malcolm (1875) * St. George and St. Michael (1876) * Thomas Wingfold, Curate (1876; republished as The Curate’s Awakening) * The Marquis of Lossie (1877; republished as The Marquis’ Secret), the second book of Malcolm * Paul Faber, Surgeon (1879; republished as The Lady’s Confession), a sequel to Thomas Wingfold, Curate * Sir Gibbie (1879; republished as The Baronet’s Song) * Mary Marston (1881; republished as A Daughter’s Devotion) * Warlock o’ Glenwarlock (1881; republished as Castle Warlock and The Laird’s Inheritance) * Weighed and Wanting (1882; republished as A Gentlewoman’s Choice) * Donal Grant (1883; republished as The Shepherd’s Castle), a sequel to Sir Gibbie * What’s Mine’s Mine (1886; republished as The Highlander’s Last Song) * Home Again: A Tale (1887; republished as The Poet’s Homecoming) * The Elect Lady (1888; republished as The Landlady’s Master) * A Rough Shaking (1891) * There and Back (1891; republished as The Baron’s Apprenticeship), a sequel to Thomas Wingfold, Curate and Paul Faber, Surgeon * Heather and Snow (1893; republished as The Peasant Girl’s Dream) * Salted with Fire (1896; republished as The Minister’s Restoration) * Far Above Rubies (1898) Poetry * Twelve of the Spiritual Songs of Novalis (1851), privately printed translation of the poetry of Novalis * Within and Without: A Dramatic Poem (1855) * Poems (1857) * “A Hidden Life” and Other Poems (1864) * “The Disciple” and Other Poems (1867) * Exotics: A Translation of the Spiritual Songs of Novalis, the Hymn-book of Luther, and Other Poems from the German and Italian (1876) * Dramatic and Miscellaneous Poems (1876) * Diary of an Old Soul (1880) * A Book of Strife, in the Form of the Diary of an Old Soul (1880), privately printed * The Threefold Cord: Poems by Three Friends (1883), privately printed, with Greville Matheson and John Hill MacDonald * Poems (1887) * The Poetical Works of George MacDonald, 2 Volumes (1893) * Scotch Songs and Ballads (1893) * Rampolli: Growths from a Long-planted Root (1897) Nonfiction * Unspoken Sermons (1867) * England’s Antiphon (1868, 1874) * The Miracles of Our Lord (1870) * Cheerful Words from the Writing of George MacDonald (1880), compiled by E. E. Brown * Orts: Chiefly Papers on the Imagination, and on Shakespeare (1882) * “Preface” (1884) to Letters from Hell (1866) by Valdemar Adolph Thisted * The Tragedie of Hamlet, Prince of Denmarke: A Study With the Test of the Folio of 1623 (1885) * Unspoken Sermons, Second Series (1885) * Unspoken Sermons, Third Series (1889) * A Cabinet of Gems, Cut and Polished by Sir Philip Sidney; Now, for the More Radiance, Presented Without Their Setting by George MacDonald (1891) * The Hope of the Gospel (1892) * A Dish of Orts (1893) * Beautiful Thoughts from George MacDonald (1894), compiled by Elizabeth Dougall In popular culture * (Alphabetical by artist) * Christian celtic punk band Ballydowse have a song called “George MacDonald” on their album Out of the Fertile Crescent. The song is both taken from MacDonald’s poem “My Two Geniuses” and liberally quoted from Phantastes. * American classical composer John Craton has utilized several of MacDonald’s stories in his works, including “The Gray Wolf” (in a tone poem of the same name for solo mandolin– 2006) and portions of “The Cruel Painter”, Lilith, and The Light Princess (in Three Tableaux from George MacDonald for mandolin, recorder, and cello– 2011). * Contemporary new-age musician Jeff Johnson wrote a song titled “The Golden Key” based on George MacDonald’s story of the same name. He has also written several other songs inspired by MacDonald and the Inklings. * Jazz pianist and recording artist Ray Lyon has a song on his CD Beginning to See (2007), called “Up The Spiral Stairs”, which features lyrics from MacDonald’s 26 and 27 September devotional readings from the book Diary of an Old Soul. * A verse from The Light Princess is cited in the “Beauty and the Beast” song by Nightwish. * Rock group The Waterboys titled their album Room to Roam (1990) after a passage in MacDonald’s Phantastes, also found in Lilith. The title track of the album comprises a MacDonald poem from the text of Phantastes set to music by the band. The novels Lilith and Phantastes are both named as books in a library, in the title track of another Waterboys album, Universal Hall (2003). (The Waterboys have also quoted from C. S. Lewis in several songs, including “Church Not Made With Hands” and “Further Up, Further In”, confirming the enduring link in modern pop culture between MacDonald and Lewis.) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_MacDonald

I was born with verse in my blood. I was raised with poetry mixed in with my mother's milk. We were immersed in poetry from our school days; we were taught to read it, appreciate it, glean wisdom from it, knew all the poets of old by heart...Ironcally, in my culture, writing poetry is the high art and privilege of men seasoned by age and gifted by Creator with this rare talent; it was not for the young to 'fool around' with, so we were not taught or encouraged to express ourselves through verse. So I never knew I had it... It was in my young adulthood that I started to feel the Song of the heart stirring in me. A friend shared with me his poetry, showed me that we all have the capability, if only we tune into ourselves and listen. The first few tentative poems were born from under my pen. Then life happened, I tuned out, forgot that part of myself, shut the door on it for more than a decade. I do not know what prompted for my Song to resurface, one day it just started pouring out of me, but I am grateful for the reawakening of that part of my soul that I'd given up for lost, as well as for the people around me who fuel my inspiration. Whether intentionally or not, they keep the fire burning. An enormous Thank You to all of you for reading, commenting, sharing and inspiring. This is a wonderful and nurturing community for all aspiring poets. Prose is the language of the mind, poetry is the language of the soul.

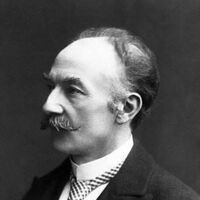

Thomas Hardy (2 June 1840 – 11 January 1928) was an English novelist and poet. While his works typically belong to the Naturalism movement, several poems display elements of the previous Romantic and Enlightenment periods of literature, such as his fascination with the supernatural. While he regarded himself primarily as a poet who composed novels mainly for financial gain, he became and continues to be widely regarded for his novels, such as Tess of the d'Urbervilles and Far from the Madding Crowd. Hardy's poetry, first published in his fifties, has come to be as well regarded as his novels and has had a significant influence over modern English poetry, especially after The Movement poets of the 1950s and 1960s cited Hardy as a major figure.

I started dabbling at age 13, and after a while, I was writing full poems, however, I only have poetry from when I was 16 and up. I am now 28, and I have found that it is so much easier to say things through poetry than it is to verbalize them. I draw inspiration for my poetry from writers, musicians, movies, daily interactions, my faith, and much more. As far as writers go, when I was younger I got introduced to Langston Hughes, and I have learned to take from his style of writing. I also enjoy some good old Shakespeare every once in a while. Most of my influence, however, comes from music; I draw my influence from genres that include but are not limited to, hip-hop, folk, rock, and country. Another thing that really impacts my poetry are events that have taken place in my life. Movie characters and themes also have a chance to have their fair share of influence in my poetry. I am a Christ-follower first and foremost, so, beneath most of my poems stories, there is a spiritual undertone. My plainly faith-based poems, however, are a written (hard) memory of the headspace that I was in at that time in my life. People can create all sorts of art without having to fabricate who they are, and without compromising who they are as a person; it's being able to take from other peoples experiences and write about them, based on the writer's interpretation, that can set a writer apart from others. I write mainly Free Verse poetry, because to me poetry is a lot of self-expression, and if I were to follow the set guidelines of a certain type of poetry, I would then be forfeiting my creative license. Sometimes, however, I like to take from certain styles of poetry, especially when I am trying to convey a particular emotion, for example, I not only write Free Verse but, I also have learned to take from styles, such as Blank Verse & Limericks. I have a friend who said this, "If there is one thing I have learned about writing over the years it is that the best work comes from writing without the audience in mind." I find this quote to be accurate for not only my writing but for writing in general. Love y'all!

Robert Herrick (baptized 24 August 1591 – buried 15 October 1674) was a 17th-century English poet. Born in Cheapside, London, he was the seventh child and fourth son of Julia Stone and Nicholas Herrick, a prosperous goldsmith. His father died in a fall from a fourth-floor window in November 1592, when Robert was a year old (whether this was suicide remains unclear). The tradition that Herrick received his education at Westminster is groundless. It is more likely that (like his uncle's children) he attended The Merchant Taylors' School. In 1607 he became apprenticed to his uncle, Sir William Herrick, who was a goldsmith and jeweler to the king. The apprenticeship ended after only six years when Herrick, at age twenty-two, matriculated at St John's College, Cambridge. He graduated in 1617. Robert Herrick became a member of the Sons of Ben, a group centered upon an admiration for the works of Ben Jonson. Herrick wrote at least five poems to Jonson. Herrick took holy orders in 1623, and in 1629 he became vicar of Dean Prior in Devonshire. In 1647, in the wake of the English Civil War, Herrick was ejected from his vicarage for refusing the Solemn League and Covenant. He then returned to London, living in Westminster and depending on the charity of his friends and family. He spent some time preparing his lyric poems for publication, and had them printed in 1648 under the title Hesperides; or the Works both Human and Divine of Robert Herrick, with a dedication to the Prince of Wales. When King Charles II was restored to the throne in 1660, Herrick petitioned for his own restoration to his living. Perhaps King Charles felt kindly towards this genial man, who had written verses celebrating the births of both Charles II and his brother James before the Civil War. Herrick became the vicar of Dean Prior again in the summer of 1662 and lived there until his death in October 1674, at the ripe age of 83. His date of death is not known, but he was buried on 15 October. Herrick was a bachelor all his life, and many of the women he names in his poems are thought to be fictional. Poetic style and stature Herrick wrote over 2,500 poems, about half of which appear in his major work, Hesperides. Hesperides also includes the much shorter Noble Numbers, his first book, of spiritual works, first published in 1647. He is well-known for his style and, in his earlier works, frequent references to lovemaking and the female body. His later poetry was more of a spiritual and philosophical nature. Among his most famous short poetical sayings are the unique monometers, such as "Thus I / Pass by / And die,/ As one / Unknown / And gone." Herrick sets out his subject-matter in the poem he printed at the beginning of his collection, The Argument of his Book. He dealt with English country life and its seasons, village customs, complimentary poems to various ladies and his friends, themes taken from classical writings and a solid bedrock of Christian faith, not intellectualized but underpinning the rest. Herrick never married, and none of his love-poems seem to connect directly with any one beloved woman. He loved the richness of sensuality and the variety of life, and this is shown vividly in such poems as Cherry-ripe, Delight in Disorder and Upon Julia’s Clothes. The over-riding message of Herrick’s work is that life is short, the world is beautiful, love is splendid, and we must use the short time we have to make the most of it. This message can be seen clearly in To the Virgins, to make much of Time, To Daffodils, To Blossoms and Corinna going a-Maying, where the warmth and exuberance of what seems to have been a kindly and jovial personality comes over strongly. The opening stanza in one of his more famous poems, "To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time", is as follows: Gather ye rosebuds while ye may, Old Time is still a-flying; And this same flower that smiles today, Tomorrow will be dying. This poem is an example of the carpe diem genre; the popularity of Herrick's poems of this kind helped revive the genre. His poems were not widely popular at the time they were published. His style was strongly influenced by Ben Jonson, by the classical Roman writers, and by the poems of the late Elizabethan era. This must have seemed quite old-fashioned to an audience whose tastes were tuned to the complexities of the metaphysical poets such as John Donne and Andrew Marvell. His works were rediscovered in the early nineteenth century, and have been regularly printed ever since. The Victorian poet Swinburne described Herrick as the greatest song writer...ever born of English race. It is certainly true that despite his use of classical allusions and names, his poems are easier for modern readers to understand than those of many of his contemporaries. Robert Herrick is a major character in Rose Macaulay's 1932 historical novel, They Were Defeated. References Wikipedia - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Herrick_(poet)

Born and raised in Soweto. God, my family and sports and music are the most important things in my life. I started writing poems as a hobby and then developed a greater liking for it. The poems I write are based on the emotions I feel at that time, but also sometimes they are inspired by music & movies. I write poetry to entertain and inspire other people to better themselves and that through them, they will learn & most importantly, know how strong and mighty God is.

Dylan Marlais Thomas (27 October 1914 – 9 November 1953) was a Welsh poet and writer who wrote exclusively in English. In addition to poetry, he wrote short stories and scripts for film and radio, which he often performed himself. His public readings, particularly in America, won him great acclaim; his sonorous voice with a subtle Welsh lilt became almost as famous as his works. His best-known works include the “play for voices” Under Milk Wood and the celebrated villanelle for his dying father, “Do not go gentle into that good night”. Appreciative critics have also noted the craftsmanship and compression of poems such as “In my Craft or Sullen Art”, and the rhapsodic lyricism in “And death shall have no dominion” and “Fern Hill”.