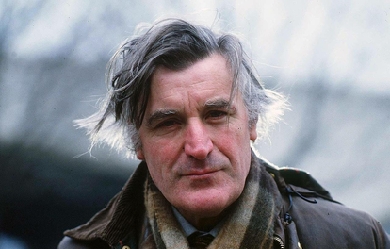

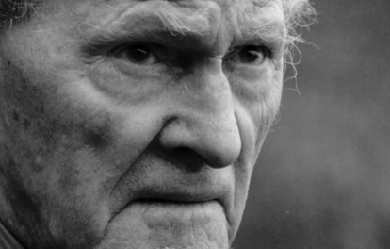

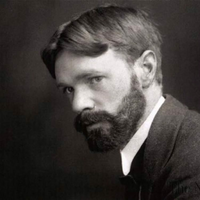

Edward James (Ted) Hughes was born in Mytholmroyd, in the West Riding district of Yorkshire, on August 17, 1930. His childhood was quiet and dominately rural. When he was seven years old, his family moved to the small town of Mexborough in South Yorkshire, and the landscape of the moors of that area informed his poetry throughout his life. Hughes graduated from Cambridge in 1954. A few years later, in 1956, he co-founded the literary magazine St. Botolph’s Review with a handful of other editors. At the launch party for the magazine, he met Sylvia Plath. A few short months later, on June 16, 1956, they were married.

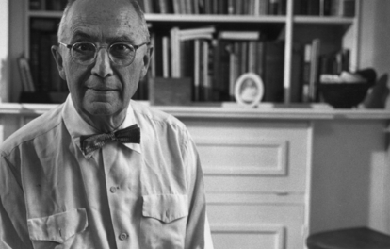

Edward Estlin Cummings (October 14, 1894 – September 3, 1962), popularly known as E. E. Cummings, with the abbreviated form of his name often written by others in lowercase letters as e.e. cummings (in the style of some of his poems—see name and capitalization, below), was an American poet, painter, essayist, author, and playwright. His body of work encompasses approximately 2,900 poems, two autobiographical novels, four plays and several essays, as well as numerous drawings and paintings. He is remembered as a preeminent voice of 20th century poetry.

I am an enthusiastic scholar of American, Irish, and English history, Victorian literature, myths, legends, folklore, and Pagan religions. My prose and poetry are generally Gothic in theme and usually set in historical periods. My favourite authors are Edgar Allen Poe, Samuel Clemens, Charles Dickens, Henry James, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, H.P. Lovecraft, M. R. James, Washington Irving, and Oscar Wilde, just to name a few, and my favourite poets are Keats, Byron, Yeats, Wordsworth, Tennyson, and Longfellow. I have three books of poetry currently on the market, three Gothic novels, one anthology of six horror stories, and several novellas and novelettes. I was raised in Wheatridge, Colorado and attended The University of Colorado at Denver. I currently live in Corvallis, Montana in the great Pacific Northwest.

Richard Le Gallienne (20 January 1866– 15 September 1947) was an English author and poet. The American actress Eva Le Gallienne (1899–1991) was his daughter, by his second marriage. Life and career He was born in Liverpool. He started work in an accountant’s office, but abandoned this job to become a professional writer. The book My Ladies’ Sonnets appeared in 1887, and in 1889 he became, for a brief time, literary secretary to Wilson Barrett. He joined the staff of the newspaper The Star in 1891, and wrote for various papers by the name Logroller. He contributed to The Yellow Book, and associated with the Rhymers’ Club. His first wife, Mildred Lee, died in 1894. They had one daughter, Hesper. In 1897 he married the Danish journalist Julie Norregard, who left him in 1903 and took their daughter Eva to live in Paris. Le Gallienne subsequently became a resident of the United States. He has been credited with the 1906 translation from the Danish of Peter Nansen’s Love’s Trilogy; but most sources and the book itself attribute it to Julie. They were divorced in June 1911. On October 27, 1911, he married Mrs. Irma Perry, née Hinton, whose previous marriage to her first cousin, the painter and sculptor Roland Hinton Perry, had been dissolved in 1904. Le Gallienne and Irma had known each other for some time, and had jointly published an article as early as 1906. Irma’s daughter Gwendolyn Perry subsequently called herself “Gwen Le Gallienne”, but was almost certainly not his natural daughter, having been born in 1900. Le Gallienne and Irma lived in Paris from the late 1920s, where Gwen was by then an established figure in the expatriate bohéme (see, e.g.) and where he wrote a regular newspaper column. Le Gallienne lived in Menton on the French Riviera during the 1940s. During the Second World War Le Gallienne was prevented from returning to his Menton home and lived in Monaco for the rest of the war. Le Gallienne’s house in Menton was occupied by German troops and his library was nearly sent back to Germany as bounty. Le Gallienne appealed to a German officer in Monaco who allowed him to return to Menton to collect his books. During the war Le Gallienne refused to write propaganda for the local German and Italian authorities, and with no income, once collapsed in the street due to hunger. In later times he knew Llewelyn Powys and John Cowper Powys. Asked how to say his name, he told The Literary Digest the stress was “on the last syllable: le gal-i-enn’. As a rule I hear it pronounced as if it were spelled ‘gallion,’ which, of course, is wrong.” (Charles Earle Funk, What’s the Name, Please?, Funk & Wagnalls, 1936.) A number of his works are now available online. He also wrote the foreword to “The Days I Knew” by Lillie Langtry 1925, George H. Doran Company on Murray Hill New York. Works * My Ladies’ Sonnets and Other Vain and Amatorious Verses (1887) * Volumes in Folio (1889) poems * George Meredith: Some Characteristics (1890) * The Book-Bills of Narcissus (1891) * English Poems (1892) * The Religion of a Literary Man (1893) * Robert Louis Stevenson: An Elegy and Other Poems (1895) * Quest of the Golden Girl (1896) novel * Prose Fancies (1896) * Retrospective Reviews (1896) * Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam (1897) * If I Were God (1897) * The Romance Of Zion Chapel (1898) * In Praise of Bishop Valentine (1898) * Young Lives (1899) * Sleeping Beauty and Other Prose Fancies (1900) * The Worshipper Of The Image (1900) * The Love Letters of the King, or The Life Romantic (1901) * An Old Country House (1902) * Odes from the Divan of Hafiz (1903) translation * Old Love Stories Retold (1904) * Painted Shadows (1904) * Romances of Old France (1905) * Little Dinners with the Sphinx and other Prose Fancies (1907) * Omar Repentant (1908) * Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde (1909) Translator * Attitudes and Avowals (1910) essays * October Vagabonds (1910) * New Poems (1910) * The Maker of Rainbows and Other Fairy-Tales and Fables (1912) * The Lonely Dancer and Other Poems (1913) * The Highway to Happiness (1913) * Vanishing Roads and Other Essays (1915) * The Silk-Hat Soldier and Other Poems in War Time (1915) * The Chain Invisible (1916) * Pieces of Eight (1918) * The Junk-Man and Other Poems (1920) * A Jongleur Strayed (1922) poems * Woodstock: An Essay (1923) * The Romantic '90s (1925) memoirs * The Romance of Perfume (1928) * There Was a Ship (1930) * From a Paris Garret (1936) memoirs * The Diary of Samuel Pepys (editor) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Le_Gallienne

Rare & Strange...Lover of Wine, Sports, Skulls, The Sun, All Things Fast, Giving & Taking Chances, People Watching, Music, Poetry, Animals, Dialogue, Sensuality, Sexuality, Passion & Passionate People, Confidence, Art, Movies, Conversations, Romance, Philosophy & Johnny Depp.....Watching movies that make you think - like A waking life or with great dialogue. It's all about the lighting... What makes us different, you & I? I'm on my life mission of seeking the strange, yet the similar, the one who will make me think, make me not think, who will drive me wild with words, passion and love. I wear my heart on my sleeve and won't stop to let the world take away my spirit. I refuse to settle even if it means I never stop ...but I know he's out there my eclectic twin soul who will love adventure, random rants, giving and caring for others, fitting in between the cracks with me and standing out in the crowd too. Intelligent and Cultured , both city and country lover, who will pack up run through the mountains taking random photos of cemeteries and visions in the clouds, who will jump on a horse and ride a wild ride with me...a best friend, a soul mate, the other half who inspires me and I inspire he and long talks with large glasses of wine and endless nights in electric passion ...tantric, twisted, non-judging just accepting each other completely, swallowing each other ...

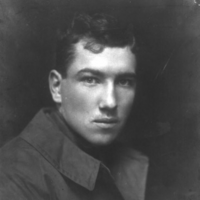

On July 24, 1895, Robert Graves was born in Wimbledon, near London. His father, Alfred Perceval Graves, was a Gaelic scholar and minor Irish poet. His mother, Amalie von Ranke Graves, was a relation of Leopold von Ranke, one of the founding fathers of modern historical studies. One of ten children, Robert was greatly influenced by his mother's puritanical beliefs and his father's love of Celtic poetry and myth. As a young man, he was more interested in boxing and mountain climbing than studying, although poetry later sustained him through a turbulent adolescence. In 1913 Graves won a scholarship to continue his studies at St. John's College, Oxford, but in August 1914 he enlisted as a junior officer in the Royal Welch Fusiliers. He fought in the Battle of Loos and was injured in the Somme offensive in 1916. While convalescing, he published his first collection of poetry, Over the Brazier. By 1917, though still an active serviceman, Graves had published three volumes. In 1918, he spent a year in the trenches, where he was again severely wounded. In January 1918, at the age of twenty-two, he married eighteen-year-old Nancy Nicholson, with whom he was to have four children. Traumatized by the war, he went to Oxford with his wife and took a position at St. John's College. Graves's early volumes of poetry, like those of his contemporaries, deal with natural beauty and bucolic pleasures, and with the consequences of the First World War. Over the Brazier and Fairies and Fusiliers earned for Graves the reputation as an accomplished war poet. After meeting the American poet and theorist Laura Riding in 1926, Graves's poetry underwent a significant transformation. Douglas Day has written that the "influence of Laura Riding is quite possibly the most important single element in [Graves's] poetic career: she persuaded him to curb his digressiveness and his rambling philosophizing and to concentrate instead on terse, ironic poems written on personal themes." In 1927, Graves and his first wife separated permanently, and in 1929 he published Goodbye to All That, an autobiography that announced his psychological accommodation with the residual horror of his war experiences. Shortly afterward, he departed to Majorca with Laura Riding. In addition to completing many books of verse while in Majorca, Graves also wrote several volumes of criticism, some in collaboration with Riding. The couple cofounded Seizin Press in 1928 and Epilogue, a semiannual magazine, in 1935. During that period, he evolved his theory of poetry as spiritually cathartic to both the poet and the reader. Although Graves claimed that he wrote novels only to earn money, it was through these that he attained status as a major writer in 1934, with the publication of the historical novel I, Claudius, and its sequel, Claudius the God and His Wife Messalina. (During the 1970's, the BBC adapted the novels into an internationally popular television series.) At the onset of the Spanish Civil War in 1936, Graves and Riding fled Majorca, eventually settling in America. In 1939, Laura Riding left Graves for the writer Schuyler Jackson; one year later Graves began a relationship with Beryl Hodge that was to last until his death. It was in the 1940s, after his break with Riding, that Graves formulated his personal mythology of the White Goddess. Inspired by late nineteenth-century studies of matriarchal societies and goddess cults, this mythology was to pervade all of his later work. After World War II, Graves returned to Majorca, where he lived with Hodge and continued to write. By the 1950s, Graves had won an enormous international reputation as a poet, novelist, literary scholar, and translator. In 1962, W. H. Auden went as far as to assert that Graves was England's "greatest living poet." In 1968, he received the Queen's Gold Medal for Poetry. During his lifetime he published more than 140 books, including fifty-five collections of poetry (he reworked his Collected Poems repeatedly during his career), fifteen novels, ten translations, and forty works of nonfiction, autobiography, and literary essays. From 1961 to 1966, Graves returned to England to serve as a professor of poetry at Oxford. In the 1970s his productivity fell off; and the last decade of his life was lost in silence and senility. Robert Graves died in Majorca in 1985, at the age of ninety. Poetry * Over the Brazier (1916) * Goliath and David (1917) * Fairies and Fusiliers (1918) * Treasure Box (1920) * Country Sentiment (1920) * The Pier-Glass (1921) * Whipperginny (1923) * To Whom Else? Deyá (1931) * The Poems of Robert Graves (1958) * Man Does, Woman Is (1964) * Love Respelt (1966) * Poems About Love (1969) * Love Respelt Again (1969) * Poems: Abridged for Dolls and Princes (1971) * Poems 1970-1972 (1973) * New Collected Poems (1977) * The Complete Poems, ed. Beryl Graves and Dunstan Ward (2000) References Poets.org - www.poets.org/poet.php/prmPID/193

Lonnie Rutledge is a prolific artist, songwriter, and poet from the United States. He is known for his peculiar methods, intense concepts, experimental writing and often demented production. He has described his style as 'Schizodelic'; a term he is noted for coining in the mid 1990's. Lxnnnie has released many albums under assorted aliases in multiple genres of music. He has had songs featured in major motion pictures, produced music for a number of commercials, designed album covers and published a book of poetry.

William Carlos Williams (September 17, 1883 – March 4, 1963) was an American poet closely associated with modernism and Imagism. He was also a pediatrician and general practitioner of medicine with a medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine. Williams "worked harder at being a writer than he did at being a physician" but excelled at both. Although his primary occupation was as a family doctor, Williams had a successful literary career as a poet. In addition to poetry (his main literary focus), he occasionally wrote short stories, plays, novels, essays, and translations. He practiced medicine by day and wrote at night. Early in his career, he briefly became involved in the Imagist movement through his friendships with Ezra Pound and H.D. (also known as Hilda Doolittle, another well-known poet whom he befriended while attending the University of Pennsylvania), but soon he began to develop opinions that differed from those of his poet/friends.

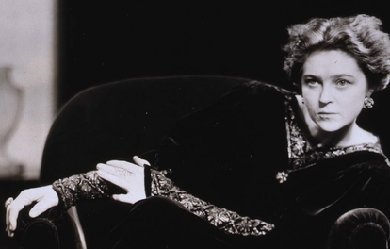

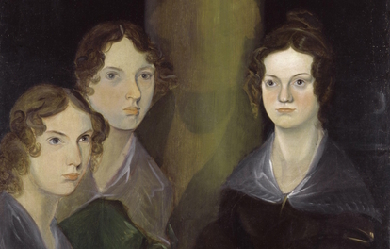

Emily Jane Brontë (30 July 1818 – 19 December 1848) was an English novelist and poet, best remembered for her solitary novel, Wuthering Heights, now considered a classic of English literature. Emily was the third eldest of the four surviving Brontë siblings, between the youngest Anne and her brother Branwell. She published under the pen name Ellis Bell. She was born in Thornton, near Bradford in Yorkshire, to Maria Branwell and Patrick Brontë. She was the younger sister of Charlotte Brontë and the fifth of six children. In 1824, the family moved to Haworth, where Emily's father was perpetual curate, and it was in these surroundings that their literary gifts flourished.

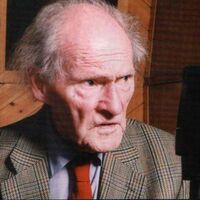

Ronald Stuart Thomas (29 March 1913 – 25 September 2000), published as R. S. Thomas, was a Welsh poet and Anglican priest who was noted for his nationalism, spirituality and deep dislike of the anglicisation of Wales. In 1955, John Betjeman, in his introduction to the first collection of Thomas’s poetry to be produced by a major publisher, Song at the Year's Turning, predicted that Thomas would be remembered long after Betjeman himself was forgotten. M. Wynn Thomas said: "He was the Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn of Wales because he was such a troubler of the Welsh conscience. He was one of the major English language and European poets of the 20th century." R. S. Thomas was born in Cardiff, the only child of Thomas Hubert and Margaret (née Davis). The family moved to Holyhead in 1918 because of his father's work in the merchant navy. He was awarded a bursary in 1932 to study at Bangor University, where he read Classics. In 1936, having completed his theological training at St. Michael's College, Llandaff, he was ordained as a priest in the Church in Wales. From 1936 to 1940 he was the curate of Chirk, Denbighshire, where he met his future wife, Mildred (Elsi) Eldridge, an English artist. He subsequently became curate at Tallarn Green, Flintshire. Thomas and Mildred were married in 1940 and remained together until her death in 1991. Their son, Gwydion, was born 29 August 1945. The Thomas family lived on a tiny income and lacked the comforts of modern life, largely by the Thomas's choice. One of the few household amenities the family ever owned, a vacuum cleaner, was rejected because Thomas decided it was too noisy. For twelve years, from 1942 to 1954, Thomas was rector at Manafon, near Welshpool in rural Montgomeryshire. It was during his time at Manafon that he first began to study Welsh and that he published his first three volumes of poetry, The Stones of the Field, An Acre of Land and The Minister. Thomas' poetry achieved a breakthrough with the publication of his fourth book Song at the Year's Turning, in effect a collected edition of his first three volumes, which was critically very well received and opened with Betjeman's famous introduction. His position was also helped by winning the Royal Society of Literature's Heinemann Award. Thomas learnt the Welsh language at age 30, too late in life, he said, to be able to write poetry in it. The 1960s saw him working in a predominantly Welsh speaking community and he later wrote two prose works in Welsh, Neb (English: Nobody), an ironic and revealing autobiography written in the third person, and Blwyddyn yn Llŷn (English: A Year in Llŷn). In 1964 he won the Queen's Gold Medal for Poetry. From 1967 to 1978 he was vicar at St Hywyn's Church (built 1137) in Aberdaron at the western tip of the Llŷn Peninsula. Thomas retired from church ministry in 1978 and he and his wife relocated to Y Rhiw, in "a tiny, unheated cottage in one of the most beautiful parts of Wales, where, however, the temperature sometimes dipped below freezing", according to Theodore Dalrymple. Free from the constraints of the church he was able to become more political and active in the campaigns that were important to him. He became a fierce advocate of Welsh nationalism, although he never supported Plaid Cymru because he believed they did not go far enough in their opposition to England. In 1996 Thomas was nominated for the Nobel Prize for Literature (the winner that year was Seamus Heaney). Thomas died on 25 September 2000, aged 87, at his home at Pentrefelin near Criccieth. He had been ill with heart trouble and had been treated at Gwynnedd hospital until two weeks before he died. After his death an event celebrating his life and poetry was held in Westminster Abbey with readings from Heaney, Andrew Motion, Gillian Clarke and John Burnside. Thomas's ashes are buried close to the door of St. John's Church, Porthmadog, Gwynedd. Beliefs Thomas believed in what he called "the true Wales of my imagination", a Welsh-speaking, aboriginal community that was in tune with the natural world. He viewed western (specifically English) materialism and greed, represented in the poetry by his mythical "Machine", as the destroyers of community. He could tolerate neither the English who bought up Wales and, in his view, stripped it of its wild and essential nature, nor the Welsh whom he saw as all too eager to kowtow to English money and influence. This may help explain why Thomas was an ardent supporter of CND and described himself as a pacifist but also why he supported the Meibion Glyndŵr fire-bombings of English-owned holiday cottages in rural Wales. On this subject he said in 1998, "what is one death against the death of the whole Welsh nation?" He was also active in wildlife preservation and worked with the RSPB and Welsh volunteer organisations for the preservation of the Red Kite. He resigned his RSPB membership over their plans to introduce non-native kites to Wales. Thomas's son, Gwydion, a resident of Thailand, recalls his father's sermons, in which he would "drone on" to absurd lengths about the evil of refrigerators, washing machines, televisions and other modern devices. Thomas preached that they were all part of the temptation of scrambling after gadgets rather than attending to more spiritual needs. "It was the Machine, you see", Gwydion Thomas explained to a biographer. "This to a congregation that didn’t have any of these things and were longing for them." Although he may have taken some ideas to extreme lengths, Theodore Dalrymple wrote, Thomas "was raising a deep and unanswered question: What is life for? Is it simply to consume more and more, and divert ourselves with ever more elaborate entertainments and gadgetry? What will this do to our souls?" Although he was a cleric, he was not always charitable and was known for being awkward and taciturn. Some critics have interpreted photographs of him as indicating he was "formidable, bad-tempered, and apparently humorless." Works Almost all of Thomas's work concerns the Welsh landscape and the Welsh people, themes with both political and spiritual subtext. His views on the position of the Welsh people, as a conquered people are never far below the surface. As a cleric, his religious views are also present in his works. His earlier works focus on the personal stories of his parishioners, the farm labourers and working men and their wives, challenging the cosy view of the traditional pastoral poem with harsh and vivid descriptions of rural lives. The beauty of the landscape, although ever-present, is never suggested as a compensation for the low pay or monotonous conditions of farm work. This direct view of "country life" comes as a challenge to many English writers writing on similar subjects and challenging the more pastoral works of such as contemporary poets as Dylan Thomas. Thomas's later works were of a more metaphysical nature, more experimental in their style and focusing more overtly on his spirituality. Laboratories of the Spirit (1975) gives, in its title, a hint at this development and also reveals Thomas's increasing experiments with scientific metaphor. He described this shift as an investigation into the "adult geometry of the mind".} Fearing that poetry was becoming a dying art, inaccessible to those who most needed it, "he attempted to make spiritually minded poems relevant within, and relevant to, a science-minded, post-industrial world", to represent that world both in form and in content even as he rejected its machinations. Despite his nationalism Thomas could be hard on his fellow countrymen. Often his works read as more of a criticism of Welshness than a celebration. He himself said there is a "lack of love for human beings" in his poetry. Other critics have not been so harsh. Al Alvarez said: "He was wonderful, very pure, very bitter but the bitterness was beautifully and very sparely rendered. He was completely authoritative, a very, very fine poet, completely off on his own, out of the loop but a real individual. It's not about being a major or minor poet. It's about getting a work absolutely right by your own standards and he did that wonderfully well." Thomas's final works commonly sold 20,000 copies in Britain alone. Books * The Stones of the Field (1946) * An Acre of Land (1952) * The Minister (1953) * Song at the Year's Turning (1955) * Poetry for Supper (1958) * Tares, [Corn-weed] (1961) * The Bread of Truth (1963) * Words and the Poet (1964, lecture) * Pietà (1966) * Not That He Brought Flowers (1968) * H'm (1972) * What is a Welshman? (1974) * Laboratories of the Spirit (1975) * Abercuawg (1976, lecture) * The Way of It (1977) * Frequencies (1978) * Between Here and Now (1981) * Ingrowing Thoughts (1985) * Neb (1985) in Welsh, autobiography, written in the third person * Experimenting with an Amen (1986) * Welsh Airs (1987) * The Echoes Return Slow (1988) * Counterpoint (1990) * Blwyddyn yn Llŷn (1990) in Welsh * Pe Medrwn Yr Iaith : ac ysgrifau eraill ed. Tony Brown & Bedwyr L. Jones, essays in Welsh (1990) * Mass for Hard Times (1992) * No Truce with the Furies (1995) * Autobiographies (1997, collection of prose writings) * Residues (2002, posthumously) References Wikipedia - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/R._S._Thomas

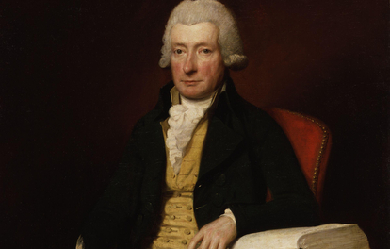

William Cowper (26 November 1731– 25 April 1800) was an English poet and hymnodist. One of the most popular poets of his time, Cowper changed the direction of 18th century nature poetry by writing of everyday life and scenes of the English countryside. In many ways, he was one of the forerunners of Romantic poetry. Samuel Taylor Coleridge called him “the best modern poet”, whilst William Wordsworth particularly admired his poem Yardley-Oak. He was a nephew of the poet Judith Madan.

.jpg)

One that knows about the beauty of simplicity. Although giving up to the temptation of complexity, severing the link with the eventual reader. As time allows I'll post brief explanations of knots and obscure references that were not avoided. Not a fan of editing, outside real English native speakers reality. So pardon me for all artificiality. I am trying to make amends to my native language, an ongoing project. As English literature is concerned and especially American, British and Irish poetry... I love it. Beyond any regret, written words may conflict with the spirit of times. I don't aspire, rather transpire toxic thoughts, beauty feeds equilibrium. Ethics and principles, hope and resilience. I see that bucket of Web Dubois. Subtle take over that I never thought possible twenty years ago, on the turn of 20th century, full of lessons turned into caricatures by a cold underlying, unrevealed power(s). And yet, "quality of life" has never been higher, even for "the dispossessed". Looking closely, hearing whispers returning, how would I like to live other people's lives, to ascertain facts and legends. Pace of life, mythologic infinity, eradicated impossible. Maybe. But if here remains even one "pico of doubt"...( maybe not). For those who read strange portuguese...one exemple infra. https://www.escritas.org/pt/n/mgenthbjpafa21 (credits: yukino_neko_girl_anime_star_wreath. Congrats for the art.)

William Sydney Porter (September 11, 1862– June 5, 1910), known by his pen name O. Henry, was an American short story writer. His stories are known for their surprise endings. Biography Early life William Sidney Porter was born on September 11, 1862, in Greensboro, North Carolina. He changed the spelling of his middle name to Sydney in 1898. His parents were Dr. Algernon Sidney Porter (1825–88), a physician, and Mary Jane Virginia Swaim Porter (1833–65). William’s parents had married on April 20, 1858. When William was three, his mother died from tuberculosis, and he and his father moved into the home of his paternal grandmother. As a child, Porter was always reading, everything from classics to dime novels; his favorite works were Lane’s translation of One Thousand and One Nights and Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy. Porter graduated from his aunt Evelina Maria Porter’s elementary school in 1876. He then enrolled at the Lindsey Street High School. His aunt continued to tutor him until he was fifteen. In 1879, he started working in his uncle’s drugstore in Greensboro, and on August 30, 1881, at the age of nineteen, Porter was licensed as a pharmacist. At the drugstore, he also showed off his natural artistic talents by sketching the townsfolk. Move to Texas Porter traveled with Dr. James K. Hall to Texas in March 1882, hoping that a change of air would help alleviate a persistent cough he had developed. He took up residence on the sheep ranch of Richard Hall, James’ son, in La Salle County and helped out as a shepherd, ranch hand, cook, and baby-sitter. While on the ranch, he learned bits of Spanish and German from the mix of immigrant ranch hands. He also spent time reading classic literature. Porter’s health did improve. He traveled with Richard to Austin in 1884, where he decided to remain and was welcomed into the home of Richard’s friends, Joseph Harrell and his wife. Porter resided with the Harrells for three years. He went to work briefly for the Morley Brothers Drug Company as a pharmacist. Porter then moved on to work for the Harrell Cigar Store located in the Driskill Hotel. He also began writing as a sideline and wrote many of his early stories in the Harrell house. As a young bachelor, Porter led an active social life in Austin. He was known for his wit, story-telling and musical talents. He played both the guitar and mandolin. He sang in the choir at St. David’s Episcopal Church and became a member of the “Hill City Quartette”, a group of young men who sang at gatherings and serenaded young women of the town. Porter met and began courting Athol Estes, then seventeen years old and from a wealthy family. Historians believe Porter met Athol at the laying of the cornerstone of the Texas State Capitol on March 2, 1885. Her mother objected to the match because Athol was ill, suffering from tuberculosis. On July 1, 1887, Porter eloped with Athol and were married in the parlor of the home of Reverend R. K. Smoot, pastor of the Central Presbyterian Church, where the Estes family attended church. The couple continued to participate in musical and theater groups, and Athol encouraged her husband to pursue his writing. Athol gave birth to a son in 1888, who died hours after birth, and then a daughter, Margaret Worth Porter, in September 1889. Porter’s friend Richard Hall became Texas Land Commissioner and offered Porter a job. Porter started as a draftsman at the Texas General Land Office (GLO) on January 12, 1887 at a salary of $100 a month, drawing maps from surveys and fieldnotes. The salary was enough to support his family, but he continued his contributions to magazines and newspapers. In the GLO building, he began developing characters and plots for such stories as “Georgia’s Ruling” (1900), and “Buried Treasure” (1908). The castle-like building he worked in was even woven into some of his tales such as "Bexar Scrip No. 2692" (1894). His job at the GLO was a political appointment by Hall. Hall ran for governor in the election of 1890 but lost. Porter resigned on January 21, 1891, the day after the new governor, Jim Hogg, was sworn in. The same year, Porter began working at the First National Bank of Austin as a teller and bookkeeper at the same salary he had made at the GLO. The bank was operated informally, and Porter was apparently careless in keeping his books and may have embezzled funds. In 1894, he was accused by the bank of embezzlement and lost his job but was not indicted at the time. He then worked full-time on his humorous weekly called The Rolling Stone, which he started while working at the bank. The Rolling Stone featured satire on life, people and politics and included Porter’s short stories and sketches. Although eventually reaching a top circulation of 1500, The Rolling Stone failed in April 1895, since the paper never provided an adequate income. However, his writing and drawings had caught the attention of the editor at the Houston Post. Porter and his family moved to Houston in 1895, where he started writing for the Post. His salary was only $25 a month, but it rose steadily as his popularity increased. Porter gathered ideas for his column by loitering in hotel lobbies and observing and talking to people there. This was a technique he used throughout his writing career. While he was in Houston, federal auditors audited the First National Bank of Austin and found the embezzlement shortages that led to his firing. A federal indictment followed, and he was arrested on charges of embezzlement. Flight and return Porter’s father-in-law posted bail to keep him out of jail. He was due to stand trial on July 7, 1896, but the day before, as he was changing trains to get to the courthouse, an impulse hit him. He fled, first to New Orleans and later to Honduras, with which the United States had no extradition treaty at that time. William lived in Honduras for only six months, until January 1897. There he became friends with Al Jennings, a notorious train robber, who later wrote a book about their friendship. He holed up in a Trujillo hotel, where he wrote Cabbages and Kings, in which he coined the term “banana republic” to qualify the country, a phrase subsequently used widely to describe a small, unstable tropical nation in Latin America with a narrowly focused, agrarian economy. Porter had sent Athol and Margaret back to Austin to live with Athol’s parents. Unfortunately, Athol became too ill to meet Porter in Honduras as he had planned. When he learned that his wife was dying, Porter returned to Austin in February 1897 and surrendered to the court, pending trial. Athol Estes Porter died from tuberculosis (then known as consumption) on July 25, 1897. Porter had little to say in his own defense at his trial and was found guilty on February 17, 1898 of embezzling $854.08. He was sentenced to five years in prison and imprisoned on March 25, 1898, at the Ohio Penitentiary in Columbus, Ohio. Porter was a licensed pharmacist and was able to work in the prison hospital as the night druggist. He was given his own room in the hospital wing, and there is no record that he actually spent time in the cell block of the prison. He had fourteen stories published under various pseudonyms while he was in prison but was becoming best known as “O. Henry”, a pseudonym that first appeared over the story “Whistling Dick’s Christmas Stocking” in the December 1899 issue of McClure’s Magazine. A friend of his in New Orleans would forward his stories to publishers so that they had no idea that the writer was imprisoned. Porter was released on July 24, 1901, for good behavior after serving three years. He reunited with his daughter Margaret, now age 11, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where Athol’s parents had moved after Porter’s conviction. Margaret was never told that her father had been in prison—just that he had been away on business. Later life and death Porter’s most prolific writing period started in 1902, when he moved to New York City to be near his publishers. While there, he wrote 381 short stories. He wrote a story a week for over a year for the New York World Sunday Magazine. His wit, characterization, and plot twists were adored by his readers but often panned by critics. Porter married again in 1907 to childhood sweetheart Sarah (Sallie) Lindsey Coleman, whom he met again after revisiting his native state of North Carolina. Sarah Lindsey Coleman was herself a writer and wrote a romanticized and fictionalized version of their correspondence and courtship in her novella Wind of Destiny. Porter was a heavy drinker, and by 1908, his markedly deteriorating health affected his writing. In 1909, Sarah left him, and he died on June 5, 1910, of cirrhosis of the liver, complications of diabetes, and an enlarged heart. After funeral services in New York City, he was buried in the Riverside Cemetery in Asheville, North Carolina. His daughter, Margaret Worth Porter, had a short writing career from 1913 to 1916. She married cartoonist Oscar Cesare of New York in 1916; they were divorced four years later. She died of tuberculosis in 1927 and is buried next to her father. Stories O. Henry’s stories frequently have surprise endings. In his day he was called the American answer to Guy de Maupassant. While both authors wrote plot twist endings, O. Henry’s stories were considerably more playful. His stories are also known for witty narration. Most of O. Henry’s stories are set in his own time, the early 20th century. Many take place in New York City and deal for the most part with ordinary people: policemen, waitresses, etc. O. Henry’s work is wide-ranging, and his characters can be found roaming the cattle-lands of Texas, exploring the art of the con-man, or investigating the tensions of class and wealth in turn-of-the-century New York. O. Henry had an inimitable hand for isolating some element of society and describing it with an incredible economy and grace of language. Some of his best and least-known work is contained in Cabbages and Kings, a series of stories each of which explores some individual aspect of life in a paralytically sleepy Central American town, while advancing some aspect of the larger plot and relating back one to another. Cabbages and Kings was his first collection of stories, followed by The Four Million. The second collection opens with a reference to Ward McAllister’s “assertion that there were only 'Four Hundred’ people in New York City who were really worth noticing. But a wiser man has arisen—the census taker—and his larger estimate of human interest has been preferred in marking out the field of these little stories of the ‘Four Million.’” To O. Henry, everyone in New York counted. He had an obvious affection for the city, which he called “Bagdad-on-the-Subway”, and many of his stories are set there—while others are set in small towns or in other cities. His final work was “Dream”, a short story intended for the magazine The Cosmopolitan but left incomplete at the time of his death. Among his most famous stories are: “The Gift of the Magi” about a young couple, Jim and Della, who are short of money but desperately want to buy each other Christmas gifts. Unbeknownst to Jim, Della sells her most valuable possession, her beautiful hair, in order to buy a platinum fob chain for Jim’s watch; while unbeknownst to Della, Jim sells his own most valuable possession, his watch, to buy jeweled combs for Della’s hair. The essential premise of this story has been copied, re-worked, parodied, and otherwise re-told countless times in the century since it was written. “The Ransom of Red Chief”, in which two men kidnap a boy of ten. The boy turns out to be so bratty and obnoxious that the desperate men ultimately pay the boy’s father $250 to take him back. “The Cop and the Anthem” about a New York City hobo named Soapy, who sets out to get arrested so that he can be a guest of the city jail instead of sleeping out in the cold winter. Despite efforts at petty theft, vandalism, disorderly conduct, and “mashing” with a young prostitute, Soapy fails to draw the attention of the police. Disconsolate, he pauses in front of a church, where an organ anthem inspires him to clean up his life—and is ironically charged for loitering and sentenced to three months in prison. “A Retrieved Reformation”, which tells the tale of safecracker Jimmy Valentine, recently freed from prison. He goes to a town bank to case it before he robs it. As he walks to the door, he catches the eye of the banker’s beautiful daughter. They immediately fall in love and Valentine decides to give up his criminal career. He moves into the town, taking up the identity of Ralph Spencer, a shoemaker. Just as he is about to leave to deliver his specialized tools to an old associate, a lawman who recognizes him arrives at the bank. Jimmy and his fiancée and her family are at the bank, inspecting a new safe when a child accidentally gets locked inside the airtight vault. Knowing it will seal his fate, Valentine opens the safe to rescue the child. However, much to Valentine’s surprise, the lawman denies recognizing him and lets him go. “The Duplicity of Hargraves”. A short story about a nearly destitute father and daughter’s trip to Washington, D.C. “The Caballero’s Way”, in which Porter’s most famous character, the Cisco Kid, is introduced. It was first published in 1907 in the July issue of Everybody’s Magazine and collected in the book Heart of the West that same year. In later film and TV depictions, the Kid would be portrayed as a dashing adventurer, perhaps skirting the edges of the law, but primarily on the side of the angels. In the original short story, the only story by Porter to feature the character, the Kid is a murderous, ruthless border desperado, whose trail is dogged by a heroic Texas Ranger. The twist ending is, unusually for Porter, tragic. Pen name Porter used a number of pen names (including “O. Henry” or “Olivier Henry”) in the early part of his writing career; other names included S.H. Peters, James L. Bliss, T.B. Dowd, and Howard Clark. Nevertheless, the name “O. Henry” seemed to garner the most attention from editors and the public, and was used exclusively by Porter for his writing by about 1902. He gave various explanations for the origin of his pen name. In 1909 he gave an interview to The New York Times, in which he gave an account of it: It was during these New Orleans days that I adopted my pen name of O. Henry. I said to a friend: “I’m going to send out some stuff. I don’t know if it amounts to much, so I want to get a literary alias. Help me pick out a good one.” He suggested that we get a newspaper and pick a name from the first list of notables that we found in it. In the society columns we found the account of a fashionable ball. “Here we have our notables,” said he. We looked down the list and my eye lighted on the name Henry, “That’ll do for a last name,” said I. “Now for a first name. I want something short. None of your three-syllable names for me.” “Why don’t you use a plain initial letter, then?” asked my friend. “Good,” said I, “O is about the easiest letter written, and O it is.” A newspaper once wrote and asked me what the O stands for. I replied, “O stands for Olivier, the French for Oliver.” And several of my stories accordingly appeared in that paper under the name Olivier Henry. William Trevor writes in the introduction to The World of O. Henry: Roads of Destiny and Other Stories (Hodder & Stoughton, 1973) that “there was a prison guard named Orrin Henry” in the Ohio State Penitentiary “whom William Sydney Porter... immortalised as O. Henry”. According to J. F. Clarke, it is from the name of the French pharmacist Etienne Ossian Henry, whose name is in the U. S. Dispensary which Porter used working in the prison pharmacy. Writer and scholar Guy Davenport offers his own hypothesis: “The pseudonym that he began to write under in prison is constructed from the first two letters of Ohio and the second and last two of penitentiary.” Legacy The O. Henry Award is a prestigious annual prize named after Porter and given to outstanding short stories. A film was made in 1952 featuring five stories, called O. Henry’s Full House. The episode garnering the most critical acclaim was “The Cop and the Anthem” starring Charles Laughton and Marilyn Monroe. The other stories are “The Clarion Call”, “The Last Leaf”, “The Ransom of Red Chief” (starring Fred Allen and Oscar Levant), and “The Gift of the Magi”. The O. Henry House and O. Henry Hall, both in Austin, Texas, are named for him. O. Henry Hall, now owned by the Texas State University System, previously served as the federal courthouse in which O. Henry was convicted of embezzlement. Porter has elementary schools named for him in Greensboro, North Carolina (William Sydney Porter Elementary) and Garland, Texas (O. Henry Elementary), as well as a middle school in Austin, Texas (O. Henry Middle School). The O. Henry Hotel in Greensboro is also named for Porter, as is US 29 which is O. Henry Boulevard. In 1962, the Soviet Postal Service issued a stamp commemorating O. Henry’s 100th birthday. On September 11, 2012, the U.S. Postal Service issued a stamp commemorating the 150th anniversary of O. Henry’s birth. On November 23, 2011, Barack Obama quoted O. Henry while granting pardons to two turkeys named “Liberty” and “Peace”. In response, political science professor P. S. Ruckman, Jr., and Texas attorney Scott Henson filed a formal application for a posthumous pardon in September 2012, the same month that the U.S. Postal Service issued its O. Henry stamp. Previous attempts were made to obtain such a pardon for Porter in the administrations of Woodrow Wilson, Dwight Eisenhower, and Ronald Reagan, but no one had ever bothered to file a formal application. Ruckman and Henson argued that Porter deserved a pardon because (1) he was a law-abiding citizen prior to his conviction; (2) his offense was minor; (3) he had an exemplary prison record; (4) his post-prison life clearly indicated rehabilitation; (5) he would have been an excellent candidate for clemency in his time, had he but applied for pardon; (6) by today’s standards, he remains an excellent candidate for clemency; and (7) his pardon would be a well-deserved symbolic gesture and more. O. Henry’s love of language inspired the O. Henry Pun-Off, an annual spoken word competition began in 1978 that takes place at the O. Henry House. Bibliography * Cabbages and Kings (1904) * The Four Million (1906), short stories * The Trimmed Lamp (1907), short stories: “The Trimmed Lamp”, “A Madison Square Arabian Night”, “The Rubaiyat of a Scotch Highball”, “The Pendulum”, “Two Thanksgiving Day Gentlemen”, “The Assessor of Success”, “The Buyer from Cactus City”, “The Badge of Policeman O’Roon”, “Brickdust Row”, “The Making of a New Yorker”, “Vanity and Some Sables”, “The Social Triangle”, “The Purple Dress”, "The Foreign Policy of Company 99", “The Lost Blend”, “A Harlem Tragedy”, “'The Guilty Party’”, “According to Their Lights”, “A Midsummer Knight’s Dream”, “The Last Leaf”, “The Count and the Wedding Guest”, “The Country of Elusion”, “The Ferry of Unfulfilment”, “The Tale of a Tainted Tenner”, “Elsie in New York” * Heart of the West (1907), short stories: “Hearts and Crosses”, “The Ransom of Mack”, “Telemachus, Friend”, “The Handbook of Hymen”, “The Pimienta Pancakes”, “Seats of the Haughty”, “Hygeia at the Solito”, “An Afternoon Miracle”, “The Higher Abdication”, "Cupid à la Carte", “The Caballero’s Way”, “The Sphinx Apple”, “The Missing Chord”, “A Call Loan”, “The Princess and the Puma”, “The Indian Summer of Dry Valley Johnson”, “Christmas by Injunction”, “A Chaparral Prince”, “The Reformation of Calliope” * The Voice of the City (1908), short stories: “The Voice of the City”, “The Complete Life of John Hopkins”, “A Lickpenny Lover”, “Dougherty’s Eye-opener”, “'Little Speck in Garnered Fruit’”, “The Harbinger”, “While the Auto Waits”, “A Comedy in Rubber”, “One Thousand Dollars”, “The Defeat of the City”, “The Shocks of Doom”, “The Plutonian Fire”, “Nemesis and the Candy Man”, “Squaring the Circle”, “Roses, Ruses and Romance”, “The City of Dreadful Night”, “The Easter of the Soul”, “The Fool-killer”, “Transients in Arcadia”, “The Rathskeller and the Rose”, “The Clarion Call”, “Extradited from Bohemia”, “A Philistine in Bohemia”, “From Each According to His Ability”, “The Memento” * The Gentle Grafter (1908), short stories: “The Octopus Marooned”, “Jeff Peters as a Personal Magnet”, “Modern Rural Sports”, “The Chair of Philanthromathematics”, “The Hand That Riles the World”, “The Exact Science of Matrimony”, “A Midsummer Masquerade”, “Shearing the Wolf”, “Innocents of Broadway”, “Conscience in Art”, “The Man Higher Up”, “Tempered Wind”, “Hostages to Momus”, “The Ethics of Pig” * Roads of Destiny (1909), short stories: “Roads of Destiny”, “The Guardian of the Accolade”, “The Discounters of Money”, “The Enchanted Profile”, “Next to Reading Matter”, “Art and the Bronco”, "Phœbe", “A Double-dyed Deceiver”, “The Passing of Black Eagle”, “A Retrieved Reformation”, “Cherchez la Femme”, “Friends in San Rosario”, “The Fourth in Salvador”, “The Emancipation of Billy”, “The Enchanted Kiss”, “A Departmental Case”, “The Renaissance at Charleroi”, “On Behalf of the Management”, “Whistling Dick’s Christmas Stocking”, “The Halberdier of the Little Rheinschloss”, “Two Renegades”, “The Lonesome Road” * Options (1909), short stories: “'The Rose of Dixie’”, “The Third Ingredient”, “The Hiding of Black Bill”, “Schools and Schools”, “Thimble, Thimble”, “Supply and Demand”, “Buried Treasure”, “To Him Who Waits”, “He Also Serves”, “The Moment of Victory”, “The Head-hunter”, “No Story”, “The Higher Pragmatism”, “Best-seller”, “Rus in Urbe”, “A Poor Rule” * Strictly Business (1910), short stories: “Strictly Business”, “The Gold That Glittered”, “Babes in the Jungle”, “The Day Resurgent”, “The Fifth Wheel”, “The Poet and the Peasant”, “The Robe of Peace”, “The Girl and the Graft”, “The Call of the Tame”, “The Unknown Quantity”, “The Thing’s the Play”, “A Ramble in Aphasia”, “A Municipal Report”, “Psyche and the Pskyscraper”, “A Bird of Bagdad”, “Compliments of the Season”, “A Night in New Arabia”, “The Girl and the Habit”, “Proof of the Pudding”, “Past One at Rooney’s”, “The Venturers”, “The Duel”, “'What You Want’” * Whirligigs (1910), short stories: “The World and the Door”, “The Theory and the Hound”, “The Hypotheses of Failure”, “Calloway’s Code”, “A Matter of Mean Elevation”, “Girl”, “Sociology in Serge and Straw”, “The Ransom of Red Chief”, “The Marry Month of May”, “A Technical Error”, “Suite Homes and Their Romance”, “The Whirligig of Life”, “A Sacrifice Hit”, “The Roads We Take”, “A Blackjack Bargainer, ”The Song and the Sergeant", “One Dollar’s Worth”, “A Newspaper Story”, “Tommy’s Burglar”, “A Chaparral Christmas Gift”, “A Little Local Colour”, “Georgia’s Ruling”, “Blind Man’s Holiday”, “Madame Bo-Peep of the Ranches” * Sixes and Sevens (1911), short stories: “The Last of the Troubadours”, “The Sleuths”, “Witches’ Loaves”, “The Pride of the Cities”, “Holding Up a Train”, “Ulysses and the Dogman”, “The Champion of the Weather”, “Makes the Whole World Kin”, “At Arms with Morpheus”, “A Ghost of a Chance”, “Jimmy Hayes and Muriel”, “The Door of Unrest”, “The Duplicity of Hargraves”, “Let Me Feel Your Pulse”, “October and June”, “The Church with an Overshot-Wheel”, “New York by Camp Fire Light”, “The Adventures of Shamrock Jolnes”, “The Lady Higher Up”, “The Greater Coney”, “Law and Order”, “Transformation of Martin Burney”, “The Caliph and the Cad”, “The Diamond of Kali”, “The Day We Celebrate” * Rolling Stones (1912), short stories: “The Dream”, “A Ruler of Men”, “The Atavism of John Tom Little Bear”, “Helping the Other Fellow”, “The Marionettes”, “The Marquis and Miss Sally”, “A Fog in Santone”, “The Friendly Call”, “A Dinner at———”, “Sound and Fury”, “Tictocq”, “Tracked to Doom”, “A Snapshot at the President”, “An Unfinished Christmas Story”, “The Unprofitable Servant”, “Aristocracy Versus Hash”, “The Prisoner of Zembla”, “A Strange Story”, “Fickle Fortune, or How Gladys Hustled”, “An Apology”, “Lord Oakhurst’s Curse”, "Bexar Scrip No. 2692” * Waifs and Strays (1917), short stories References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/O._Henry

These are writings from the inner workings of a mind in constant thought about LIFE and everything it entails for the purpose of self-transcendence and with the intention to bring more understanding and healing to my own life and possibly those of others. My journey is one of self-exploration and discovery. Since my beliefs lie on the premise that we are so strongly connected to everything in existence, in getting to know myself I am getting to know the world. Learning about the world teaches me about myself. I find freedom in understanding and expression. My one true love is the paradox of questioning existence.

Khalil Gibran (Arabic pronunciation: [xaˈliːl ʒiˈbrɑːn]) (January 6, 1883 - April 10, 1931); born Gubran Khalil Gubran, was a Lebanese-American artist, poet, and writer. Born in the town of Bsharri in modern-day Lebanon (then part of the Ottoman Mount Lebanon mutasarrifate), as a young man he emigrated with his family to the United States where he studied art and began his literary career. In the Arab world, Gibran is regarded as a literary and political rebel. His Romantic style was at the heart of a renaissance in modern Arabic literature, especially prose poetry, breaking away from the classical school. In Lebanon, he is still celebrated as a literary hero. He is chiefly known in the English-speaking world for his 1923 book The Prophet, an early example of inspirational fiction including a series of philosophical essays written in poetic English prose. The book sold well despite a cool critical reception, gaining popularity in the 1930s and again especially in the 1960s counterculture. Gibran is the third best-selling poet of all time, behind Shakespeare and Lao-Tzu. In academic contexts his name is often spelled Jubrān Khalīl Jubrān,:217:255 Jibrān Khalīl Jibrān,:217:559 or Jibrān Xalīl Jibrān;:189 Arabic جبران خليل جبران , January 6, 1883 – April 10, 1931) also known as Kahlil Gibran, In Lebanon Gibran was born to a Maronite Catholic family from the historical town of Bsharri in northern Lebanon. His mother Kamila, daughter of a priest, was thirty when he was born; his father Khalil was her third husband. As a result of his family's poverty, Gibran received no formal schooling during his youth. However, priests visited him regularly and taught him about the Bible, as well as the Arabic and Syriac languages. Gibran's father initially worked in an apothecary but, with gambling debts he was unable to pay, he went to work for a local Ottoman-appointed administrator. Around 1891, extensive complaints by angry subjects led to the administrator being removed and his staff being investigated. Gibran's father was imprisoned for embezzlement, and his family's property was confiscated by the authorities. Kamila Gibran decided to follow her brother to the United States. Although Gibran's father was released in 1894, Kamila remained resolved and left for New York on June 25, 1895, taking Khalil, his younger sisters Mariana and Sultana, and his elder half-brother Peter (in Arabic, Butrus). In the United States The Gibrans settled in Boston's South End, at the time the second largest Syrian/Lebanese-American community in the United States. Due to a mistake at school, he was registered as Kahlil Gibran. His mother began working as a seamstress peddler, selling lace and linens that she carried from door to door. Gibran started school on September 30, 1895. School officials placed him in a special class for immigrants to learn English. Gibran also enrolled in an art school at a nearby settlement house. Through his teachers there, he was introduced to the avant-garde Boston artist, photographer, and publisher Fred Holland Day, who encouraged and supported Gibran in his creative endeavors. A publisher used some of Gibran's drawings for book covers in 1898. Gibran's mother, along with his elder brother Peter, wanted him to absorb more of his own heritage rather than just the Western aesthetic culture he was attracted to, so at the age of fifteen, Gibran returned to his homeland to study at a Maronite-run preparatory school and higher-education institute in Beirut, called Al-Hikma (The Wisdom). He started a student literary magazine with a classmate and was elected "college poet". He stayed there for several years before returning to Boston in 1902, coming through Ellis Island (a second time) on May 10. Two weeks before he got back, his sister Sultana died of tuberculosis at the age of 14. The next year, Peter died of the same disease and his mother died of cancer. His sister Marianna supported Gibran and herself by working at a dressmaker’s shop. Art and poetry Gibran held his first art exhibition of his drawings in 1904 in Boston, at Day's studio. During this exhibition, Gibran met Mary Elizabeth Haskell, a respected headmistress ten years his senior. The two formed an important friendship that lasted the rest of Gibran’s life. Though publicly discreet, their correspondence reveals that the two were lovers. In fact, Gibran twice proposed to her but marriage was not possible in the face of her family's conservatism. Haskell influenced not only Gibran’s personal life, but also his career. She became his editor, and introduced him to Charlotte Teller, a journalist,and Emilie Michel (Micheline), a French teacher, who accepted to pose for him as a model and became close friends. In 1908, Gibran went to study art in Paris for two years. While there he met his art study partner and lifelong friend Youssef Howayek. While most of Gibran's early writings were in Arabic, most of his work published after 1918 was in English. His first book for the publishing company Alfred A. Knopf, in 1918, was The Madman, a slim volume of aphorisms and parables written in biblical cadence somewhere between poetry and prose. Gibran also took part in the New York Pen League, also known as the "immigrant poets" (al-mahjar), alongside important Lebanese-American authors such as Ameen Rihani, Elia Abu Madi and Mikhail Naimy, a close friend and distinguished master of Arabic literature, whose descendants Gibran declared to be his own children, and whose nephew, Samir, is a godson of Gibran's. Much of Gibran's writings deal with Christianity, especially on the topic of spiritual love. But his mysticism is a convergence of several different influences : Christianity, Islam, Sufism, Hinduism and theosophy. He wrote : "You are my brother and I love you. I love you when you prostrate yourself in your mosque, and kneel in your church and pray in your synagogue. You and I are sons of one faith - the Spirit." Juliet Thompson, one of Gibran's acquaintances, reported several anecdotes relating to Gibran: She recalls Gibran met `Abdu'l-Bahá, the leader of the Bahá’í Faith at the time of his visit to the United States, circa 1911–1912. Barbara Young, in "This Man from Lebanon: A Study of Khalil Gibran", records Gibran was unable to sleep the night before meeting `Abdu'l-Bahá who sat for a pair of portraits. Thompson reports Gibran saying that all the way through writing of "Jesus, The Son of Man", he thought of `Abdu'l-Bahá. Years later, after the death of `Abdu'l-Bahá, there was a viewing of the movie recording of `Abdu'l-Bahá – Gibran rose to talk and in tears, proclaimed an exalted station of `Abdu'l-Bahá and left the event weeping. His poetry is notable for its use of formal language, as well as insights on topics of life using spiritual terms. Gibran's best-known work is The Prophet, a book composed of twenty-six poetic essays. Its popularity grew markedly during the 1960s with the American counterculture and then with the flowering of the New Age movements. It has remained popular with these and with the wider population to this day. Since it was first published in 1923, The Prophet has never been out of print. Having been translated into more than forty languages, it was one of the bestselling books of the twentieth century in the United States. One of his most notable lines of poetry is from "Sand and Foam" (1926), which reads: "Half of what I say is meaningless, but I say it so that the other half may reach you". This line was used by John Lennon and placed, though in a slightly altered form, into the song "Julia" from The Beatles' 1968 album The Beatles (a.k.a. "The White Album”). Drawing and painting Gibran was an accomplished artist, especially in drawing and watercolour, having attended art school in Paris from 1908 to 1910, pursuing a symbolist and romantic style over then up-and-coming realism. His more than 700 images include portraits of his friends WB Yeats, Carl Jung and August Rodin. A possible Gibran painting was the subject of a June 2012 episode of the PBS TV series History Detectives. Political thought Gibran was by no means a politician. He used to say : "I am not a politician, nor do I wish to become one" and "Spare me the political events and power struggles, as the whole earth is my homeland and all men are my fellow countrymen". Nevertheless, Gibran called for the adoption of Arabic as a national language of Syria, considered from a geographic point of view, not as a political entity. When Gibran met `Abdu'l-Bahá in 1911–12, who traveled to the United States partly to promote peace, Gibran admired the teachings on peace but argued that "young nations like his own" be freed from Ottoman control. Gibran also wrote the famous "Pity The Nation" poem during these years, posthumously published in The Garden of the Prophet. When the Ottomans were finally driven out of Syria during World War I, Gibran's exhilaration was manifested in a sketch called "Free Syria" which appeared on the front page of al-Sa'ih's special "victory" edition. Moreover, in a draft of a play, still kept among his papers, Gibran expressed great hope for national independence and progress. This play, according to Khalil Hawi, "defines Gibran's belief in Syrian nationalism with great clarity, distinguishing it from both Lebanese and Arab nationalism, and showing us that nationalism lived in his mind, even at this late stage, side by side with internationalism.” Death and legacy Gibran died in New York City on April 10, 1931: the cause was determined to be cirrhosis of the liver and tuberculosis. Before his death, Gibran expressed the wish that he be buried in Lebanon. This wish was fulfilled in 1932, when Mary Haskell and his sister Mariana purchased the Mar Sarkis Monastery in Lebanon, which has since become the Gibran Museum. The words written next to Gibran's grave are "a word I want to see written on my grave: I am alive like you, and I am standing beside you. Close your eyes and look around, you will see me in front of you ...." Gibran willed the contents of his studio to Mary Haskell. There she discovered her letters to him spanning twenty-three years. She initially agreed to burn them because of their intimacy, but recognizing their historical value she saved them. She gave them, along with his letters to her which she had also saved, to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Library before she died in 1964. Excerpts of the over six hundred letters were published in "Beloved Prophet" in 1972. Mary Haskell Minis (she wed Jacob Florance Minis in 1923) donated her personal collection of nearly one hundred original works of art by Gibran to the Telfair Museum of Art in Savannah, Georgia in 1950. Haskell had been thinking of placing her collection at the Telfair as early as 1914. In a letter to Gibran, she wrote "I am thinking of other museums ... the unique little Telfair Gallery in Savannah, Ga., that Gari Melchers chooses pictures for. There when I was a visiting child, form burst upon my astonished little soul." Haskell's gift to the Telfair is the largest public collection of Gibran’s visual art in the country, consisting of five oils and numerous works on paper rendered in the artist’s lyrical style, which reflects the influence of symbolism. The future American royalties to his books were willed to his hometown of Bsharri, to be "used for good causes”. Works In Arabic: * Nubthah fi Fan Al-Musiqa (Music, 1905) * Ara'is al-Muruj (Nymphs of the Valley, also translated as Spirit Brides and Brides of the Prairie, 1906) * al-Arwah al-Mutamarrida (Rebellious Spirits, 1908) * al-Ajniha al-Mutakassira (Broken Wings, 1912) * Dam'a wa Ibtisama (A Tear and A Smile, 1914) * al-Mawakib (The Processions, 1919) * al-‘Awāsif (The Tempests, 1920) * al-Bada'i' waal-Tara'if (The New and the Marvellous, 1923) In English, prior to his death: * The Madman (1918) (downloadable free version) * Twenty Drawings (1919) * The Forerunner (1920) * The Prophet, (1923) * Sand and Foam (1926) * Kingdom of the Imagination (1927) * Jesus, The Son of Man (1928) * The Earth Gods (1931) Posthumous, in English: * The Wanderer (1932) * The Garden of the Prophet (1933, Completed by Barbara Young) * Lazarus and his Beloved (Play, 1933) Collections: * Prose Poems (1934) * Secrets of the Heart (1947) * A Treasury of Kahlil Gibran (1951) * A Self-Portrait (1959) * Thoughts and Meditations (1960) * A Second Treasury of Kahlil Gibran (1962) * Spiritual Sayings (1962) * Voice of the Master (1963) * Mirrors of the Soul (1965) * Between Night & Morn (1972) * A Third Treasury of Kahlil Gibran (1975) * The Storm (1994) * The Beloved (1994) * The Vision (1994) * Eye of the Prophet (1995) * The Treasured Writings of Kahlil Gibran (1995) Other: * Beloved Prophet, The love letters of Khalil Gibran and Mary Haskell, and her private journal (1972, edited by Virginia Hilu) Memorials and honors * Lebanese Ministry of Post and Telecommunications published a stamp in his honor in 1971. * Gibran Museum in Bsharri, Lebanon * Gibran Khalil Gibran Garden, Beirut, Lebanon * Gibran Khalil Gibran collectin, Soumaya Museum, Mexico. * Kahlil Gibran Street, Ville Saint-Laurent, Quebec, Canada inaugurated on 27 Sept. 2008 on occasion of the 125th anniversary of his birth. * Gibran Kahlil Gibran Skiing Piste, The Cedars Ski Resort, Lebanon * Kahlil Gibran Memorial Garden in Washington, D.C., dedicated in 1990 * The Kahlil Gibran Chair for Values and Peace, University of Maryland, currently held by Suheil Bushrui * Pavilion K. Gibran at École Pasteur in Montréal, Quebec, Canada * Gibran Memorial Plaque in Copley Square, Boston, Massachusetts see Kahlil Gibran (sculptor). * Khalil Gibran International Academy, a public high school in Brooklyn, NY, opened in September 2007 * Khalil Gibran Park (Parcul Khalil Gibran) in Bucharest, Romania * Gibran Kalil Gibran sculpture on a marble pedestal indoors at Arab Memorial building at Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil * Gibran Khalil Gibran Memorial, in front of Plaza de las Naciones. Buenos Aires. References Wikipedia - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Khalil_Gibran

I'm a teenage experimental poet, song writer, and author. I come from a good home but a not so good past. I explain myself through poetry and writing, because there is no other way to described me. I'm just awkward. I have severe depression and anxiety, along with other problems and struggles, and writing helps ease it all. I have love and passion for my work, and I plan on becoming a published author in the future. I try to use all senses of perspective in my writing; I wish to help change the world one poem at a time. ***PLEASE DO NOT COPYRIGHT WHAT IS PUBLISHED ON THIS BLOG. ONLY SHARE UNDER MY NAME AND ESTABLISH CORRECT OWNERSHIP. I CLAIM THESE WORKS AS MY OWN AND UNDER NO CIRCUMSTANCES SHOULD I BE BLAMED FOR FRAUD, OR HAVE PERSONS DENY ME MY RIGHTS BECAUSE OF MY AGE AND SOCIAL STANDING. MY WRITINGS, MY NAME, MY STORY, MY RIGHT. PLEASE RESPECT MY OWNERSHIP AND RESPECT MY WISHES AS A YOUNG ADULT WRITER.*** ~THANK YOU~

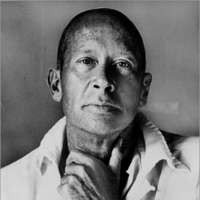

James Mercer Langston Hughes (February 1, 1902 – May 22, 1967) was an American poet, social activist, novelist, playwright, and columnist. He was one of the earliest innovators of the then-new literary art form jazz poetry. Hughes is best known for his work during the Harlem Renaissance. He famously wrote about the period that “the negro was in vogue” which was later paraphrased as “when Harlem was in vogue”.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (12 May 1828 – 9 April 1882) was an English poet, illustrator, painter and translator. He founded the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in 1848 with William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais, and was later to be the main inspiration for a second generation of artists and writers influenced by the movement, most notably William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones. His work also influenced the European Symbolists and was a major precursor of the Aesthetic movement.

I am from Cecina in Tuscany, Italy. I moved to Davis, California, in 2009. My life experience in Davis has inspired many of my recent poems. I write my poetry only in Italian language. During the last few summer seasons I have been actively sharing my poems in Tuscany where I participate frequently in cultural and poetry events. As a child, after recognizing that I had a gift for poetry, my parents submitted my work in a variety of different contests. In 1989 I won my first prize. Starting in 1998, I published my poetry in newspapers and magazines, mostly in the area of Tuscany where I was raised. My first book, "Sono un Angelo Dimenticato," was published in 1998 from Ed.La Palma; in 2008 a second book, called "Nessuna Musa di Cristallo” was also published. My poem “Sto per lasciare tutto “(English version: “I’m about to leave everything”) was published in USA, for the Davis Poetry Book 2011. My books: "Extreme Fishing" 2011, "I colori dentro" 2016, both available on Amazon. "Sospesa fra due mondi" was published in Italy by Mds Editore, 2019. In 2020 I moved back to my country and I live in Turin where I work as a teacher.