Info

The Funeral of Shelley

Louis Edouard Fournier

1889

Walker Art Gallery

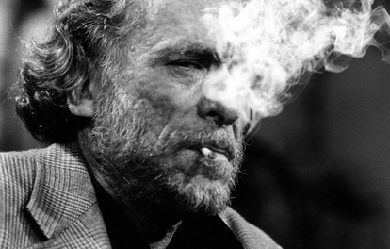

Henry Charles Bukowski (born Heinrich Karl Bukowski; August 16, 1920 – March 9, 1994) was an American poet, novelist and short story writer. His writing was influenced by the social, cultural and economic ambience of his home city of Los Angeles. It is marked by an emphasis on the ordinary lives of poor Americans, the act of writing, alcohol, relationships with women and the drudgery of work.

Emily Elizabeth Dickinson (December 10, 1830 – May 15, 1886) was an American poet. Little-known during her life, she has since been regarded as one of the most important figures in American poetry. Evidence suggests that Dickinson lived much of her life in isolation. Considered an eccentric by locals, she developed a penchant for white clothing and was known for her reluctance to greet guests or, later in life, to even leave her bedroom. Dickinson never married, and most friendships between her and others depended entirely upon correspondence.

POETRY: * Influenced by the passion and vibrant imagery created by the words of Khalil Gibran, Pablo Neruda, Grace Chacon Leon, Catherine Stanger, Cory Garcia, Nelson Reyes, and J Ann Crowder. * Author of six books; "Wings of Inspiration," "Rhymes of the Joke Machine," "The Air Almighty," "Martin's World," "Secrets of the Wind," and "Mother of Life." (published by Cyberwit.net), Published works in Mature Years, Alive Now, Torrid Literature Journal, Universal Oneness Anthology, Taj Mahal Review, Inkling Magazine, Page & Spine, Charles Carter Anthologies, Purpose Magazine, Terror House Magazine, Brief Wilderness, Cowboy Poetry Press, The Voices Project, Aberration Labyrinth, Long Shot Books, Academy of Hearts & Minds, Blue Lake Review, Gival Press, The Higgs Weldon, Funny In Five Hundred, Verse-Virtual, Wilderness House Literary Review, White Liquor Mag, Ygdrasil Literary Journal, Poetica, Green Silk Journal, Madswirl, Lyrical Passion Poetry E-Zine, Poet's Pen, Storyteller, FreeXpression, Poets' Espresso, Long Story Short, Oddball Magazine, Asinine Poetry, Write On!!, American Legion On-Line, Pegasus Review, Prayerworks, Stepping Stones, Love's Chance, Poet's Haven, Jerry Jazz Musician, Fullosia Press, The Sheltered Poet, The Belt and Beyond, Blue Minaret, and Ego Phobia. * Wrote two chapbooks entitled "In Reverence to Life" and "A Sage's Diary," (published by In His Steps Publishing). Won two poetry awards (Faith and Hope) and appeared in many anthology books. MUSIC: * Playing, writing, and arranging music for most of life. * Studied music at Westlake College of Music in Hollywood, California in 1958 and majored in piano. * Played in the 82nd Army Band in Stuttgard, Germany from 1962 until 1964. * Played in the Jimmy Dorsey Band in 1965. * Played in a band in Bergen, Norway in 1966. * Composed score for Dr. Ira Cochin's Rally George in Valley Forge children's play. * Playing the organ at 1st Methodist Church in Wind Gap, PA for the past thirty years... THE REST OF LIFE: Born in Ashtabula, Ohio, and moved to New York City shortly thereafter. Got married in 1984 and had a wonderful daughter in 1985. Can be found at his home in Bangor, PA at his keyboard, or in front of a yellow legal pad, pen in hand...

Edgar Albert Guest (20 August 1881 in Birmingham, England – 5 August 1959 in Detroit, Michigan) (aka Eddie Guest) was a prolific English-born American poet who was popular in the first half of the 20th century and became known as the People’s Poet. In 1891, Guest moved with his family to the United States from England. After he began at the Detroit Free Press as a copy boy and then a reporter, his first poem appeared 11 December 1898. He became a naturalized citizen in 1902. For 40 years, Guest was widely read throughout North America, and his sentimental, optimistic poems were in the same vein as the light verse of Nick Kenny, who wrote syndicated columns during the same decades. Guest’s most famous poem is the oft-quoted “Home”: It don’t make a difference how rich ye get t’ be’ How much yer chairs and tables cost, how great the luxury; It ain’t home t’ ye, though it be the palace of a king, Until somehow yer soul is sort o’ wrapped round everything. Within the hi how are you there’s got t’ be some babies born an’ then... Right there ye’ve got t’ bring em up t’ women good, an’ men; Home ain’t a place that gold can buy or get up in a minute; Afore it’s home there’s got t’ be a heap o’ living in it.” —Excerpt from “Home,” It takes A Heap o’ Livin’ (1916) When you’re up against a trouble, Meet it squarely, face to face, Lift your chin, and set your shoulders, Plant your feet and take a brace, When it’s vain to try to dodge it, Do the best that you can do. You may fail, but you may conquer— See it through! —Excerpt from “See It Through” Guest’s most motivating poem: You can do as much as you think you can, But you'll never accomplish more; If you're afraid of yourself, young man, There's little for you in store. For failure comes from the inside first, It's there, if we only knew it, And you can win, though you face the worst, If you feel that you're going to do it. —Excerpt from “The Secret of the Ages” (1926)

Donal Mahoney, a native of Chicago, lives in St. Louis, Missouri. His fiction and poetry have appeared in various publications, including The Wisconsin Review, The Kansas Quarterly, The South Carolina Review, The Christian Science Monitor, The Beloit Poetry Journal, Commonweal, The Galway Review (Ireland), Public Republic (Bulgaria), Revival (Ireland), The Istanbul Literary Review (Turkey) and other magazines. Some of his earliest work can be found at http://booksonblog12.blogspot.com; some newer work at http://eyeonlifemag.com/the-poetry-locksmith/donal-mahoney-poet.html#sthash.OSYzpgmQ.dpbs=

William Butler Yeats (13 June 1865 – 28 January 1939) was an Irish poet and one of the foremost figures of 20th-century literature. A pillar of the Irish literary establishment, he helped to found the Abbey Theatre, and in his later years served two terms as a Senator of the Irish Free State. He was a driving force behind the Irish Literary Revival along with Lady Gregory, Edward Martyn and others. Yeats was born in Sandymount, Ireland and educated there and in London. He spent childhood holidays in County Sligo and studied poetry from an early age when he became fascinated by Irish legends and the occult. These topics feature in the first phase of his work, which lasted roughly until the turn of the 20th century. His earliest volume of verse was published in 1889, and its slow-paced and lyrical poems display debts to Edmund Spenser, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and the poets of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. From 1900, his poetry grew more physical and realistic. He largely renounced the transcendental beliefs of his youth, though he remained preoccupied with physical and spiritual masks, as well as with cyclical theories of life. In 1923, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.

The Story of Me The Abridged “Cliff Notes” Version Enter, Stage Right Not much to tell So this will be quick Nothing special happened Though many memorable moments I was born smart More clever than most But sadly, I did not apply My mind to its full potential I’ve fallen in love And then out of love Once, twice, maybe thrice And now, fallen in love once more I led a quiet life Never been famous Never been filthy rich Done nothing exceptional Children I raised Fine, grown up now I’m glad they’re not like me They’ll realize all of their dreams Others, I help Whenever I could I try to pay it forward Hoping to get it on the flipside Some I’ve rubbed The wrong way, and so I hope they will forgive me Before I leave starship Earth The story of me Quite long in years Short on accomplishments A busload of pleasant memories Exit, stage left The End. Vic Evora 08-26-2015

Robert William Service (January 16, 1874 – September 11, 1958) was a poet and writer who has often been called "the Bard of the Yukon". He was born in Preston, Lancashire, England and he is best known for his poems "The Shooting of Dan McGrew" and "The Cremation of Sam McGee", from his first book, Songs of a Sourdough (1907; also published as The Spell of the Yukon and Other Verses).

Robert Lee Frost (March 26, 1874 – January 29, 1963) was an American poet. His work was initially published in England before it was published in the United States. Known for his realistic depictions of rural life and his command of American colloquial speech, Frost frequently wrote about settings from rural life in New England in the early 20th century, using them to examine complex social and philosophical themes. Frequently honored during his lifetime, Frost is the only poet to receive four Pulitzer Prizes for Poetry. He became one of America’s rare “public literary figures, almost an artistic institution”. He was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in 1960 for his poetic works. On July 22, 1961, Frost was named poet laureate of Vermont.

John Prophet is considered by many in the literary community to be the Salvador Dalí of poetry. His rough-hewn unfettered style mimics the artist’s unconventional view of perceived reality. Prophet encourages (through the skeletal nature of his writings) the reader to focus on the individual meaning of each word, thus allowing its message to be front and center. Meaning that can be muted within sentences and paragraphs. This creates vividness otherwise hidden. The skeletal nature of his efforts also allows the reader to flesh out meaning based on the readers personal worldview. Thus, no two observers are reading the exact same creation.

Madison Julius Cawein (March 23, 1865 – December 8, 1914) was a poet from Louisville, Kentucky. He was the fifth child of William and Christiana (Stelsly) Cawein. His father made patent medicines from herbs thus, as a child, Cawein became acquainted with and developed a love for local nature.

“Who am I? I'm a poet. What do I do? I write. And how do I live? I live.” –Rodolpho, in Puccini's La Bohème Before Passion Becomes Philosophy Such Beauty Such Fair Beauty That We Should Know In Them And Call Them Ours… The Rose, Symbol of Passion. The embodiment of life. Its scent enchanting... Its petals enticing... In each silky-smooth... fragile fold... Images of past, present, and future Are suggestively rendered And ready to be found. The Rose, Symbol of Philosophy The representation of opposites. A source of profound beauty And at the same time, If one fails to grasp it properly, A source of prolific pain And resonant regret. This Blog is dedicated to the Passion of Life Before the Philosophy of tomorrow gives it Its meaning. The yearnings... the longings... The desirous aching found Within each unrestricted beat Of a man's heart. This is my story and these are my songs Now and for all time WELCOME TO THE PLAYGROUND OF MY MIND…

Percy Bysshe Shelley (4 August 1792 – 8 July 1822) was one of the major English Romantic poets and is critically regarded as among the finest lyric poets in the English language. Shelley was famous for his association with John Keats and Lord Byron. The novelist Mary Shelley (née Godwin) was his second wife. Shelley's unconventional life and uncompromising idealism, combined with his strong disapproving voice, made him a marginalized figure during his life, important in a fairly small circle of admirers, and opened him to criticism as well as praise afterward.

▪️▪️▪️▪️▪️▪️▪️▪️▪️▪️ ▪️▪️▪️▪️▪️▪️▪️▪️ ▪️▪️▪️▪️▪️▪️ ▪️▪️▪️▪️ ▪️▪️▪️ ▪️▪️ ▪️ Finding my way with writing and poetry. 🪶The world makes more sense with poetry. Connect with me on: Tumblr: 1introvertedsage My Poetic Side: Introverted Sage All Poetry: Introverted Sage Substack: Introverted Sage

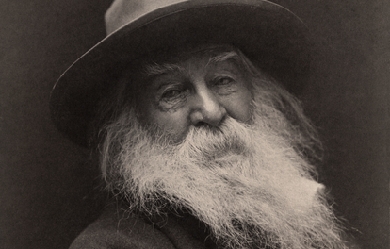

Walter Whitman (May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist and journalist. A humanist, he was a part of the transition between transcendentalism and realism, incorporating both views in his works. Whitman is among the most influential poets in the American canon, often called the father of free verse. His work was controversial in his time, particularly his 1855 poetry collection Leaves of Grass, which was described as obscene for its overt sensuality.

[b.] September 25, 1974, Tempe, AZ; [p.] Mr. Phil and Barbara K. Ransopher; [ed.] Bachelor of Arts in English (Language and Lit.); [occ.] library assistant, writer, editor; [memb.] Yahoo Groups: Appreciating Poetry (owner), Erotica Gallery (owner), Ex BBC Poetry Group (moderator), AATNAANPT (An All Totally New An All New Poetry Thread), Adult Amatuer (sic) Writers Emporium; [hon.] November 19, 2010 Poetic Skies Poem Of The Week (Her Love Has A Cold Wet Nose), May 15, 2015, First weekly winner for Fortune Poets group A Soldier's Fortune, 2015 Poet of the year for Fortune Poets; [pers.] I write what I see in my mind, what I feel in my heart, and what I know in my soul; [a.] Garland, TX

Rabindranath Tagoreα (7 May 1861 – 7 August 1941) was an Indian Bengali polymath who reshaped his region’s literature and music. Author of Gitanjali and its “profoundly sensitive, fresh and beautiful verse”, he became the first non-European to win the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1913. In translation his poetry was viewed as spiritual and mercurial; his seemingly mesmeric personality, flowing hair, and other-worldly dress earned him a prophet-like reputation in the West. His “elegant prose and magical poetry” remain largely unknown outside Bengal.

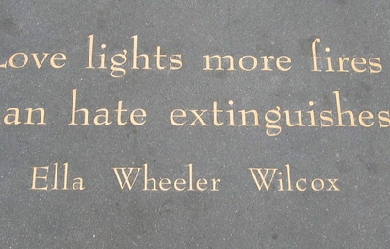

Ella Wheeler Wilcox (November 5, 1850– October 30, 1919) was an American author and poet. Her best-known work was Poems of Passion. Her most enduring work was “Solitude”, which contains the lines, “Laugh, and the world laughs with you; weep, and you weep alone”. Her autobiography, The Worlds and I, was published in 1918, a year before her death. Biography Ella Wheeler was born in 1850 on a farm in Johnstown, Wisconsin, east of Janesville, the youngest of four children. The family soon moved north of Madison. She started writing poetry at a very early age, and was well known as a poet in her own state by the time she graduated from high school. Her most famous poem, “Solitude”, was first published in the February 25, 1883 issue of The New York Sun. The inspiration for the poem came as she was travelling to attend the Governor’s inaugural ball in Madison, Wisconsin. On her way to the celebration, there was a young woman dressed in black sitting across the aisle from her. The woman was crying. Miss Wheeler sat next to her and sought to comfort her for the rest of the journey. When they arrived, the poet was so depressed that she could barely attend the scheduled festivities. As she looked at her own radiant face in the mirror, she suddenly recalled the sorrowful widow. It was at that moment that she wrote the opening lines of “Solitude”: Laugh, and the world laughs with you; Weep, and you weep alone. For the sad old earth must borrow its mirth But has trouble enough of its own She sent the poem to the Sun and received $5 for her effort. It was collected in the book Poems of Passion shortly after in May 1883. In 1884, she married Robert Wilcox of Meriden, Connecticut, where the couple lived before moving to New York City and then to Granite Bay in the Short Beach section of Branford, Connecticut. The two homes they built on Long Island Sound, along with several cottages, became known as Bungalow Court, and they would hold gatherings there of literary and artistic friends. They had one child, a son, who died shortly after birth. Not long after their marriage, they both became interested in theosophy, new thought, and spiritualism. Early in their married life, Robert and Ella Wheeler Wilcox promised each other that whoever went first through death would return and communicate with the other. Robert Wilcox died in 1916, after over thirty years of marriage. She was overcome with grief, which became ever more intense as week after week went without any message from him. It was at this time that she went to California to see the Rosicrucian astrologer, Max Heindel, still seeking help in her sorrow, still unable to understand why she had no word from her Robert. She wrote of this meeting: In talking with Max Heindel, the leader of the Rosicrucian Philosophy in California, he made very clear to me the effect of intense grief. Mr. Heindel assured me that I would come in touch with the spirit of my husband when I learned to control my sorrow. I replied that it seemed strange to me that an omnipotent God could not send a flash of his light into a suffering soul to bring its conviction when most needed. Did you ever stand beside a clear pool of water, asked Mr. Heindel, and see the trees and skies repeated therein? And did you ever cast a stone into that pool and see it clouded and turmoiled, so it gave no reflection? Yet the skies and trees were waiting above to be reflected when the waters grew calm. So God and your husband’s spirit wait to show themselves to you when the turbulence of sorrow is quieted. Several months later, she composed a little mantra or affirmative prayer which she said over and over “I am the living witness: The dead live: And they speak through us and to us: And I am the voice that gives this glorious truth to the suffering world: I am ready, God: I am ready, Christ: I am ready, Robert.”. Wilcox made efforts to teach occult things to the world. Her works, filled with positive thinking, were popular in the New Thought Movement and by 1915 her booklet, What I Know About New Thought had a distribution of 50,000 copies, according to its publisher, Elizabeth Towne. The following statement expresses Wilcox’s unique blending of New Thought, Spiritualism, and a Theosophical belief in reincarnation: “As we think, act, and live here today, we built the structures of our homes in spirit realms after we leave earth, and we build karma for future lives, thousands of years to come, on this earth or other planets. Life will assume new dignity, and labor new interest for us, when we come to the knowledge that death is but a continuation of life and labor, in higher planes”. Her final words in her autobiography The Worlds and I: “From this mighty storehouse (of God, and the hierarchies of Spiritual Beings ) we may gather wisdom and knowledge, and receive light and power, as we pass through this preparatory room of earth, which is only one of the innumerable mansions in our Father’s house. Think on these things”. Ella Wheeler Wilcox died of cancer on October 30, 1919 in Short Beach. Poetry A popular poet rather than a literary poet, in her poems she expresses sentiments of cheer and optimism in plainly written, rhyming verse. Her world view is expressed in the title of her poem “Whatever Is—Is Best”, suggesting an echo of Alexander Pope’s “Whatever is, is right,” a concept formally articulated by Gottfried Leibniz and parodied by Voltaire’s character Doctor Pangloss in Candide. None of Wilcox’s works were included by F. O. Matthiessen in The Oxford Book of American Verse, but Hazel Felleman chose no fewer than fourteen of her poems for Best Loved Poems of the American People, while Martin Gardner selected “The Way Of The World” and “The Winds of Fate” for Best Remembered Poems. She is frequently cited in anthologies of bad poetry, such as The Stuffed Owl: An Anthology of Bad Verse and Very Bad Poetry. Sinclair Lewis indicates Babbitt’s lack of literary sophistication by having him refer to a piece of verse as “one of the classic poems, like 'If’ by Kipling, or Ella Wheeler Wilcox’s ‘The Man Worth While.’” The latter opens: It is easy enough to be pleasant, When life flows by like a song, But the man worth while is one who will smile, When everything goes dead wrong. Her most famous lines open her poem “Solitude”: Laugh and the world laughs with you, Weep, and you weep alone; The good old earth must borrow its mirth, But has trouble enough of its own. “The Winds of Fate” is a marvel of economy, far too short to summarize. In full: One ship drives east and another drives west With the selfsame winds that blow. ’Tis the set of the sails, And Not the gales, That tell us the way to go. Like the winds of the sea are the ways of fate; As we voyage along through life, ’Tis the set of a soul That decides its goal, And not the calm or the strife. Ella Wheeler Wilcox cared about alleviating animal suffering, as can be seen from her poem, “Voice of the Voiceless”. It begins as follows: So many gods, so many creeds, So many paths that wind and wind, While just the art of being kind Is all the sad world needs. I am the voice of the voiceless; Through me the dumb shall speak, Till the deaf world’s ear be made to hear The wrongs of the wordless weak. From street, from cage, and from kennel, From stable and zoo, the wail Of my tortured kin proclaims the sin Of the mighty against the frail.

Vocabulary & words give me joy & a beautiful outlet to create artful expressions of creativity..I’m also a lover of nature & metaphors. I believe nature is our greatest teacher. Using a combination of vocabulary, nature, & metaphor in a variety of writing formats is what I love, from research papers, to public speaking, to story telling & poetry. I typically write in a freestyle format, but am not afraid to venture out & try new styles of poetry. I’ve always loved poetry, & am drawn to poets like Alfred Lord Tennyson, Emily Dickinson & others.

Carl Sandburg was born in Galesburg, Illinois, on January 6, 1878. His parents, August and Clara Johnson, had emigrated to America from the north of Sweden. After encountering several August Johnsons in his job for the railroad, the Sandburg's father renamed the family. The Sandburgs were very poor; Carl left school at the age of thirteen to work odd jobs, from laying bricks to dishwashing, to help support his family. At seventeen, he traveled west to Kansas as a hobo. He then served eight months in Puerto Rico during the Spanish-American war. While serving, Sandburg met a student at Lombard College, the small school located in Sandburg's hometown. The young man convinced Sandburg to enroll in Lombard after his return from the war.

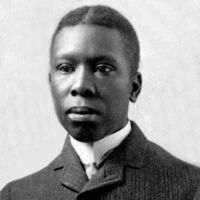

Paul Laurence Dunbar was the first African-American poet to garner national critical acclaim. Born in Dayton, Ohio, in 1872, Dunbar penned a large body of dialect poems, standard English poems, essays, novels and short stories before he died at the age of 33. His work often addressed the difficulties encountered by members of his race and the efforts of African-Americans to achieve equality in America. He was praised both by the prominent literary critics of his time and his literary contemporaries. Dunbar was born on June 27, 1872, to Matilda and Joshua Dunbar, both natives of Kentucky. His mother was a former slave and his father had escaped from slavery and served in the 55th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment and the 5th Massachusetts Colored Cavalry Regiment during the Civil War. Matilda and Joshua had two children before separating in 1874. Matilda also had two children from a previous marriage. The family was poor, and after Joshua left, Matilda supported her children by working in Dayton as a washerwoman. One of the families she worked for was the family of Orville and Wilbur Wright, with whom her son attended Dayton's Central High School. Though the Dunbar family had little material wealth, Matilda, always a great support to Dunbar as his literary stature grew, taught her children a love of songs and storytelling. Having heard poems read by the family she worked for when she was a slave, Matilda loved poetry and encouraged her children to read. Dunbar was inspired by his mother, and he began reciting and writing poetry as early as age 6. Dunbar was the only African-American in his class at Dayton Central High, and while he often had difficulty finding employment because of his race, he rose to great heights in school. He was a member of the debating society, editor of the school paper and president of the school's literary society. He also wrote for Dayton community newspapers. He worked as an elevator operator in Dayton's Callahan Building until he established himself locally and nationally as a writer. He published an African-American newsletter in Dayton, the Dayton Tattler, with help from the Wright brothers. His first public reading was on his birthday in 1892. A former teacher arranged for him to give the welcoming address to the Western Association of Writers when the organization met in Dayton. James Newton Matthews became a friend of Dunbar's and wrote to an Illinois paper praising Dunbar's work. The letter was reprinted in several papers across the country, and the accolade drew regional attention to Dunbar; James Whitcomb Riley, a poet whose works were written almost entirely in dialect, read Matthew's letter and acquainted himself with Dunbar's work. With literary figures beginning to take notice, Dunbar decided to publish a book of poems. Oak and Ivy, his first collection, was published in 1892. Though his book was received well locally, Dunbar still had to work as an elevator operator to help pay off his debt to his publisher. He sold his book for a dollar to people who rode the elevator. As more people came in contact with his work, however, his reputation spread. In 1893, he was invited to recite at the World's Fair, where he met Frederick Douglass, the renowned abolitionist who rose from slavery to political and literary prominence in America. Douglass called Dunbar "the most promising young colored man in America." Dunbar moved to Toledo, Ohio, in 1895, with help from attorney Charles A. Thatcher and psychiatrist Henry A. Tobey. Both were fans of Dunbar's work, and they arranged for him to recite his poems at local libraries and literary gatherings. Tobey and Thatcher also funded the publication of Dunbar's second book, Majors and Minors. It was Dunbar's second book that propelled him to national fame. William Dean Howells, a novelist and widely respected literary critic who edited Harper's Weekly, praised Dunbar's book in one of his weekly columns and launched Dunbar's name into the most respected literary circles across the country. A New York publishing firm, Dodd Mead and Co., combined Dunbar's first two books and published them as Lyrics of a Lowly Life. The book included an introduction written by Howells. In 1897, Dunbar traveled to England to recite his works on the London literary circuit. His national fame had spilled across the Atlantic. After returning from England, Dunbar married Alice Ruth Moore, a young writer, teacher and proponent of racial and gender equality who had a master's degree from Cornell University. Dunbar took a job at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. He found the work tiresome, however, and it is believed the library's dust contributed to his worsening case of tuberculosis. He worked there for only a year before quitting to write and recite full time. In 1902, Dunbar and his wife separated. Depression stemming from the end of his marriage and declining health drove him to a dependence on alcohol, which further damaged his health. He continued to write, however. He ultimately produced 12 books of poetry, four books of short stories, a play and five novels. His work appeared in Harper's Weekly, the Sunday Evening Post, the Denver Post, Current Literature and a number of other magazines and journals. He traveled to Colorado and visited his half-brother in Chicago before returning to his mother in Dayton in 1904. He died there on Feb. 9, 1906. Literary style Dunbar's work is known for its colorful language and a conversational tone, with a brilliant rhetorical structure. These traits were well matched to the tune-writing ability of Carrie Jacobs-Bond (1862–1946), with whom he collaborated. Use of dialect Much of Dunbar's work was authored in conventional English, while some was rendered in African-American dialect. Dunbar remained always suspicious that there was something demeaning about the marketability of dialect poems. One interviewer reported that Dunbar told him, "I am tired, so tired of dialect", though he is also quoted as saying, "my natural speech is dialect" and "my love is for the Negro pieces". Though he credited William Dean Howells with promoting his early success, Dunbar was dismayed by his demand that he focus on dialect poetry. Angered that editors refused to print his more traditional poems, he accused Howells of "[doing] my irrevocable harm in the dictum he laid down regarding my dialect verse." Dunbar, however, was continuing a literary tradition that used Negro dialect; his predecessors included Mark Twain, Joel Chandler Harris, and George Washington Cable. Two brief examples of Dunbar's work, the first in standard English and the second in dialect, demonstrate the diversity of the poet's production: (From "Dreams") What dreams we have and how they fly Like rosy clouds across the sky; Of wealth, of fame, of sure success, Of love that comes to cheer and bless; And how they wither, how they fade, The waning wealth, the jilting jade — The fame that for a moment gleams, Then flies forever, — dreams, ah — dreams! (From "A Warm Day In Winter") "Sunshine on de medders, Greenness on de way; Dat's de blessed reason I sing all de day." Look hyeah! What you axing'? What meks me so merry? 'Spect to see me sighin' W'en hit's wa'm in Febawary? List of works * Oak and Ivy (1892) * Majors and Minors (1896) * Lyrics of Lowly Life (1896) * Folks from Dixie (1898) * The Strength of Gideon (1900) * In Old Plantation Days (1903) * The Heart of Happy Hollow (1904) * Lyrics of Sunshine and Shadow (1905) References Paul Laurence Dunbar Website - www.dunbarsite.org/biopld.asp Wikipedia- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Laurence_Dunbar

Born and raised in the subs of Dublin city, Ireland. I'm a 33year old tarot reader witch bitch. I wrote under a ghost name (alexis faye) as frankly I love poetry mine isn't viewed by anyone so i wanted to share it, and got the courage to do so when I stopped relying on other people and started to carve my own path. I write mostly depression riddled poetry. Some are about my past including being sexual assaulted, abuse at the hands of several exs and alot of my poems are actually based around my ex fiance who is actually in jail for murder. My life isnt what I wanted but I'm here now sure.

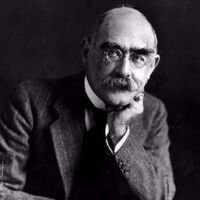

Joseph Rudyard Kipling (30 December 1865 – 18 January 1936) was an English novelist, short-story writer, poet, and journalist. He was born in British India, which inspired much of his work. Kipling was one of the most popular writers in England, in both prose and verse, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Henry James said: “Kipling strikes me personally as the most complete man of genius (as distinct from fine intelligence) that I have ever known.”

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron FRS; 22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824), simply known as Lord Byron, was an English poet and peer. One of the leading figures of the Romantic movement, Byron is regarded as one of the greatest English poets. He remains widely read and influential. Among his best-known works are the lengthy narrative poems Don Juan and Childe Harold's Pilgrimage; many of his shorter lyrics in Hebrew Melodies also became popular. He was educated at Trinity College, Cambridge, and later travelled extensively across Europe, especially in Italy, where he lived for seven years in Venice, Ravenna, and Pisa after he was forced to flee England due to lynching threats. During his stay in Italy, he frequently visited his friend and fellow poet Percy Bysshe Shelley. Later in life Byron joined the Greek War of Independence fighting the Ottoman Empire and died leading a campaign during that war, for which Greeks revere him as a folk hero. He died in 1824 at the age of 36 from a fever contracted after the First and Second Sieges of Missolonghi.