Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening

John T. Ogilvie

The visible sign of the poet's preoccupation—the word is not too strong—is the recurrent image, particularly in his earlier work, of dark woods and trees, Often, as in the lyric with which we have begun, the world of the woods..., a world offering perfect quiet and solitude, exists side by side with the realization that there is also another world, a world of people and social obligations. Both worlds have claims on the poet. He stops by woods on this "darkest evening of the year" to watch them "fill up with snow," and lingers so long that his "little horse" shakes his harness bells "to ask if there is some mistake." The poet is put in mind of the "promises" he has to keep, of the miles he still must travel. We are not told, however, that the call of social responsibility proves stronger than the attraction of the woods, which are "lovely" as well as "dark and deep"; the poet and his horse have not moved on at the poem's end. The dichotomy of the poet's obligations both to the woods and to a world of "promises"—the latter filtering like a barely heard echo through the almost hypnotic state induced by the woods and falling snow-is what gives this poem its singular interest.... The artfulness of "Stopping by Woods" consists in the way the two worlds are established and balanced. The poet is aware that the woods by which he is stopping belong to someone in the village; they are owned by the world of men. But at the same time they are his, the poet's woods, too, by virtue of what they mean to him in terms of emotion and private signification.

. . . .

What appears to be "simple" is shown to be not really simple, what appears to be innocent not really innocent.... The poet is fascinated and lulled by the empty wastes of white and black. The repetition of "sleep" in the final two lines suggests that he may succumb to the influences that are at work. There is no reason to suppose that these influences are benignant. It is, after all, "the darkest evening of the year," and the poet is alone "between the woods and frozen lake." His one bond with the security and warmth of the "outer" world, the "little horse" who wants to be about his errand, is an unsure one. The ascription of "lovely" to this scene of desolate woods, effacing snow, and black night complicates rather than alleviates the mood when we consider how pervasive are the connotations of dangerous isolation and menacing death.

From "From Woods to Stars: A Pattern of Imagery in Robert Frost’s Poetry." South Atlantic Quarterly. Winter 1959.Reuben A. Brower

Throughout the poem—brief in actual time, but with the deceptive length of dream—we are being drawn into silence and sleep, yet always with the slightest contrary pull of having to go on. The very tentative tone of the opening line lets us into the mood without our quite sensing where it will lead, just as the ordinariness of 'though' at the end of the second line assures us that we are in this world. But by repeating the ‘o’ sound, 'though' also starts the series of rhymes that will soon get the better of traveler and reader. The impression of aloneness in the first two lines prepares for concentration on seeing the strange process not of snow falling, but of woods 'filling up.' The intimacy of

reminds us again of the everyday man and his life back home, but 'queer' leads to an even lonelier scene, a kind of northern nowhere connected with the strangeness of the winter solstice,

In this second stanza the unbroken curve of rhythm adds to the sense of moving imperceptibly into a spell-world, as we dimly note the linking of the rhymes with the first stanza. The pattern is catching on to the reader, pulling him into its drowsy current.

The lone spaciousness and quiet of the third stanza is heightened by the 'shake' of bells, but 'to ask,' humorously taking the horse's point of view, tells us that the driver is awake and sane. The sounds he now attends to so closely are very like silence, images of regular movement and softness of touch. The transition to the world of sleep, almost reached in the next stanza—goes by diminution of consonantal sounds, from 'gives . . . shake . . . ask . . . mistake (gutturals easily roughened to fit the alert movement of the horse) to the sibilant ‘sound's the sweep / Of easy wind . . . 'Sweep,' by virtue of the morpheme ‘-eep,’ is closely associated with other words used for 'hushed, diminishing' actions: seep, sleep, peep, weep, creep. The quietness, concentration, and rocking motion of the last two lines of stanza three prepare perfectly for the hypnosis of the fourth. ( Compare similar effects in 'After Apple-Picking.') 'Lonely' recalls the tender alluringness of 'easy' and 'down'; 'dark' and 'deep' the strangeness of the time and the mystery of the slowly filling woods. The closing lines combine most beautifully the contrary pulls of the poem, with the repetitions, the settling down on one sleepy rhyme running against what is being said, and with the speaker echoing his prose sensible self in 'I have promises' and 'miles to go' while he almost seems to be nodding off.

'There is nothing more composing than composition,' Frost has said, and 'Stopping by Woods' shows both the process and the effect as the poet-traveler composes himself for sleep. The metaphorical implication is well hidden, with no hint offered like

To the dark and lament.

The dark nowhere of the woods, the seen and heard movement of things, and the lullaby of inner speech are an invitation to sleep—and winter sleep is again close to easeful death. ('Dark' and 'deep' are typical Romantic adjectives.) All of these poetic suggestions are in the purest sense symbolic: we cannot say in other terms what they are 'of,' though we feel their power. There are critics who have gone much further in defining what Frost 'meant'; but perhaps sleep is mystery enough. Frost's poem is symbolic in the manner of Keats's 'To Autumn,' where the over-meaning is equally vivid and equally unnameable. In contrast to 'The Oven Bird' and 'Come In,' the question of putting the mystery in words is not raised; indeed the invitation has been expressed more by song than speech. The rejection though outspoken is as instinctive as the felt attraction to the alluring darkness. From this and similar lyrics, Frost might be described as a poet of rejected invitations to voyage in the 'definitely imagined regions' that Keats and Yeats more readily enter.

From The Poetry of Robert Frost: Constellations of Intention. New York: Oxford UP, 1963. Copyright © 1963 by Reuben A. BrowerRichard Poirier

As in "Desert Places" the seasonal phase is winter, the diurnal phase is night, but, . . .the scene, we are reminded four times over, is a wood. Woods, especially when as here they are "lovely, dark and deep," are much more seductive to Frost than is a field, the "blank whiteness of benighted snow" in "Desert Places" or the frozen swamp in "The Wood-Pile." In fact, the woods are not, as the Lathem edition would have it (with its obtuse emendation of a comma after the second adjective in line 13), merely "lovely, dark, and deep." Rather, as Frost in all the editions he supervised intended, they are "lovely, [i.e.] dark and deep"; the loveliness thereby partakes of the depth and darkness which make the woods so ominous. The recognition of the power of nature, especially of snow, to obliterate the limits and boundaries of things and of his own being is, in large part, a function here of some furtive impulse toward extinction, an impulse no more predominate in Frost than it is in nature. It is in him, nonetheless, anxious to be acknowledged, and it significantly qualifies any tendency he might have to become a poet whose descriptive powers, however botanically or otherwise accurate, would be used to deny the mysterious blurrings of time and place which occur whenever he finds himself somehow participating in the inhuman transformations of the natural world. If Wallace Stevens in his poem "The Creations of Sound" has Frost in mind when he remarks that the poems of "X" "do not make the visible a little hard / To see," that is because Stevens failed to catch the characteristic strangeness of performances like "Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening." And if he has Frost in mind when, in the same poem, he speaks of "X" as "a man / Too exactly himself," it is because he would not see that Frost's emphasis on the dramatic and on the contestation of voices in poetry was a clue more to a need for self-possession than to an arrogant superfluity of it.

That need is in many ways the subject of "Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening." As its opening words suggest—"Whose woods these are I think I know"—it is a poem concerned with ownership and also with someone who cannot be or does not choose to be very emphatic even about owning himself. He does not want or expect to be seen. And his reason, aside from being on someone else's property, is that it would apparently be out of character for him to be there, communing alone with a woods fast filling up with snow. He is, after all, a man of business who has promised his time, his future to other people. It would appear that he is not only a scheduled man but a fairly convivial one. He knows who owns which parcels of land, or thinks he does, and his language has a sort of pleasant neighborliness, as in the phrase "stopping by." It is no wonder that his little horse would think his actions "queer" or that he would let the horse, instead of himself, take responsibility for the judgment. He is in danger of losing himself; and his language by the end of the third stanza begins to carry hints of a seductive luxuriousness unlike anything preceding it—"Easy wind and downy flake . . . lovely, dark and deep." Even before the somnolent repetition of the last two lines, he is ready to drop off. His opening question about who owns the woods becomes, because of the very absence from the poem of any man "too exactly himself," a question of whether the woods are to "own" him. With the drowsy repetitiousness of rhymes in the last stanza, four in a row, it takes some optimism to be sure that (thanks mostly to his little horse, who makes the only assertive sound in the poem) he will be able to keep his promises. At issue, of course, is really whether or not he will be able to "keep" his life.

From Robert Frost: The Work of Knowing. Copyright © 1977 by Oxford University Press.Guy Rotella

I have argued that the concepts of indeterminacy, correspondence, and complementarity are useful for developing a sense of Frost's poems and of their modernity. As illustration, a single poem will have to serve, a famous one. "Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening" stages its play of opposites at typically Frostian borders between night and day, storm and hearth, nature and culture, individual and group, freedom and responsibility. It works them, not "out" to resolution but in permanent suspension as complementary counters in mens animi, the feeling thought of active mind. The poem is made to make the mind just that. It unsettles certitude even in so small a matter as the disposition of accents in the opening line: "Whose woods these are I think I know." The monosyllabic tetrameter declares itself as it declares. Yet the "sound of sense" is uncertain. As an expression of doubtful guessing, "think" opposes "know," with its air of certitude. The line might be read to emphasize doubt (Whose woods these are I think I know) or confident knowledge (Whose woods these are I think I know). Once the issue is introduced, even a scrupulously "neutral" reading points it up. The evidence for choosing emphasis is insufficient to the choice.

One of Frost's characteristic devices is to set up and undermine a case of the pathetic fallacy in such a way that both construction and collapse stay actively in play. In "Stopping by Woods," the undermining nearly precedes the setting up. "Must" gives the game away, as the speaker (exercising indeterminacy) interferes with the reality he observes, imposing his thoughts and feelings on it. "Darkest" contributes to the pattern. Is the evening, say, the winter solstice, literally darkest? Could it be, given the way that snow concentrates light? Or is "darkest" a judgment the speaker projects? In the next stanza, the speaker's "reading into" nature intensifies to the point where harness bells "actually" speak. Then, as if to emphasize that such speaking is a human addition to a speechless scene, we hear that the only other sound is the "sweep" of light wind on softly falling snow. Those two categories of evidence, the self-consciously imposed and therefore suspect yet understandable human one, and the apparently indifferent yet comfortingly beautiful natural one, seem to produce the description of the woods as "lovely" and "dark and deep," a place of both (dangerous) attraction and (self-protective) threat. The oppositions are emphasized by Frost's intended punctuation—a comma after "lovely"; none after "dark," and the double doubleness of attraction and threat complicates the blunt "But" that begins the next line. Which woods, if any, is being rejected? How far does recalling that one has "promises to keep" go toward keeping them in fact?

The poem's formal qualities, while not obviously "experimental," also contribute to its balancing act. The closing repetition emphasizes the speaker's commitment to his responsibilities. It also emphasizes the repetitive tedium that makes the woods an attractive alternative to those responsibilities. This leaves open the question of just how much arguing is left to be done before any action is taken. The rhyme scheme contributes to the play. Its linked pattern seems completed and resolved in the final stanza, underlining the effect of closure: aaba, bbcb, ccdc, dddd. But is a repeated word a rhyme? Is the resolution excessive; does the repeated line work as a sign of forced closure? None of this is resolved; it is kept in complementary suspension. Similarly, the poem is clearly a made thing, an object or artifact, as its formal regularities attest; it is also an event in continuous process, as its present participial title announces and as the present tense employed throughout suggests. At the same time, the poem has a narrative thrust that tempts us to see the speaker move on (even though he does not), just as too much insistence on the poem as stranded in the present tense falsely makes it out as static. In the words of "Education by Poetry," "A thing, they say, is an event. . . . I believe it is almost an event." Balancing, unbalancing, rebalancing, those acts are the life of the poem, of the poet making and the reader taking it. Indeterminacy and complementarity are implicit in them.

from "Comparing Conceptions: Frost and Eddington, Heisenberg and Bohr." In On Frost: The Best from American Literature. Ed. Edwin H. Cady and Louis J. Budd. Durham, NC: Duke UP, 1991. Copyright © 1991 by Duke UP. Orginally published in American Literature 59:2 (May 1987).

George Montiero

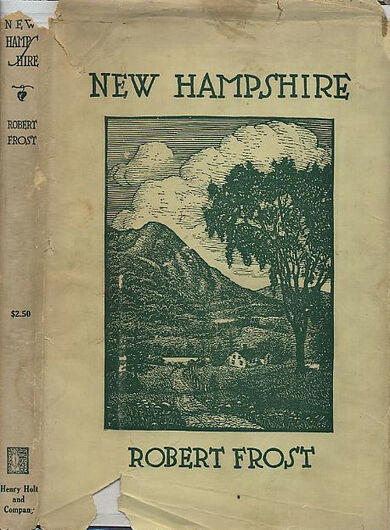

The "dark forest" in the tradition of "The Choice of the Two Paths" and the "forest dark" of Longfellow's translation of the Inferno also foreshadow the imagery of the famous Frost poem published in New Hampshire (1923), the last stanza of which begins: "The woods are lovely; dark and deep." In spurning the word "forest" for "woods," a term that is perhaps more appropriate for New England, Frost was, whether he knew it or not, following Charles Eliot Norton, whose translation of the Inferno reads "dark wood" and who glosses the opening of Dante's poem: "The dark wood is the forest of the world of sense, 'the erroneous wood of this life' . . . , that is, the wood in which man loses his way." In "the darkest evening of the year," the New England poet finds himself standing before a scene he finds attractive enough to make him linger. Frost's poem employs, significantly; the present tense. Dante's poem (through Longfellow) employs the past tense. It is as if Frost were casually remembering some familiar engraving that hung on a schoolroom wall in Lawrence as he was growing up in the 1880s, and the poet slides into the picture. He enters, so to speak, the mind of the figure who speaks the poem, a figure whose body is slowly turned into the scene, head fully away from the foreground, bulking small, holding the reins steadily and loosely. The horse and team are planted, though poised to move. And so begins the poet's dramatization of this rural and parochial tableau. "Whose woods these are I think I know. / His house is in the village though. / He will not see me stopping here / To watch his woods fill up with snow." And then, having entered the human being, he witnesses the natural drift of that human being's thoughts to the brain of his "little horse," who thinks it "queer" that the rider has decided to stop here. And then, in an equally easy transition, the teamster returns to himself, remembering that he has promises to keep and miles to go before he sleeps. Duties, responsibilities—many must have them, we think, as echolalia closes the poem, all other thoughts already turning away from the illustration on the schoolroom wall. And even as the "little horse" has been rid of the man's intrusion, so too must the rider's mind be freed of the poet's incursion. The poet's last line resonates, dismissing the reader from his, the poet's, dreamy mind and that mind's preoccupations, and returning to the poet's inside reading of the still-"fe drama that goes on forever within its frame hanging on the classroom wall.

The ways in which Frost's poem "Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening" converses with Longfellow's translation of Dante are evident from other shared echoes and images. The Inferno continues:

So full was I of slumber at the moment

In which I had abandoned the true way.

But after I had reached a mountain's foot,

At that point where the valley terminated,

Which had with consternation pierced my heart,

Upward I looked, and I beheld its shoulders,

Vested already with that planet's rays

Which leadeth others right by every road.

Then was the fear a little quieted

That in my heart's lake had endured throughout

That night, which I had passed so piteously.

What Frost "fetched" here (as in "The Road Not Taken") were the motifs of risk and decision characterizing both "The Choice of the Two Paths" and Dante's Inferno.

"The Draft Horse," a poem published at the end of Frost's life in his final volume, In the Clearing (1962), reminds us curiously of Frost's anecdote in 1912 about recognizing "another" self and not encountering that self and also of the poem "Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening." In addition it is reminiscent of "The Road Not Taken." In each case—anecdote, autumnal poem, and winter poem—the poet must make a choice. Will he "go forward to the touch," or will he "stand still in wonderment and let him pass by" in the anecdote? He will choose the "road less traveled by" (but he will leave the other for a later passing, though he probably will not return to it). He will not succumb to the aesthetic (and perhaps psychological) attractions of the woods, which are "lovely, dark and deep," but will go forth to keep his promises—of both kinds (as Frost explained): "those that I myself make for myself and those that my ancestors made for me, known as the social contract."

In too frail a buggy we drove

Behind too heavy a horse

Through a pitch-dark limitless grove. And a man came out of the trees

And took our horse by the head

And reaching back to his ribs

Deliberately stabbed him dead. The ponderous beast went down

With a crack of a broken shaft.

And the night drew through the trees

In one long invidious draft. The most unquestioning pair

That ever accepted fate

And the least disposed to ascribe

Any more than we had to hate, We assumed that the man himself

Or someone he had to obey

Wanted us to get down

And walk the rest of the way.

The "little horse" of the earlier poem is replaced by "the too-heavy horse" of the later one. The "woods" have now been replaced by "a pitch-dark limitless grove." The hint in "grove" is one of sacrificial rites and ordered violence. The "sweep of easy wind and downy flake" of "Stopping by Woods" is echoed more ominously in "The Draft Horse" in that after "the ponderous beast went down" "the night drew through the trees / In one long invidious draft." The man was alone; here he is part of an "unquestioning pair." "Stopping by Woods" was given in the first person. "The Draft Horse," like the beginning of the Inferno, takes place in the past. There is resolution in the former—even if it evinces some fatigue; in the latter there is resignation. At the time of the poem and in an earlier day, the loss of a man's horse may be as great a loss as that of one's life—probably because its loss would often lead to the death of the horse's owner. And for the poet the assassination has no rhyme or reason that he will discern. He knows only that the man "came out of the trees" (compare the intruders in "Two Tramps in Mud Time" or the neighbor in "Mending Wall" who resembles "an old-stone savage armed"). Insofar as the poet knows, this act involves motiveless malevolence less than unmalevolent motive—if there is a motive. In the Inferno, the beast that threatens the poet's pathway gives way to the poet—"Not man; man once I was," he says—who will guide him. Frost's couple have the misfortune to encounter not a guide but an assassin. "A man feared that he might find an assassin; / Another that he might find a victim," wrote Stephen Crane. "One was more wise than the other." It is not too far-fetched, I think, to see the equanimity of the poet at the end of "The Draft Horse" as a response to the anecdote, many years earlier, when the poet avoided meeting his "other" self, thereby committing the "fatal omission" of not trying to find out what "purpose . . . if we could but have made out" there was in the near-encounter. It is chilling to read the poem against its Frostian antecedents. Yet, as Keeper prefers in A Masque of Mercy (1947)—in words out of another context which might better fit the romantic poet of "The Wood- Pile"—"I say I'd rather be lost in the woods / Than found in church."

From Robert Frost and the New England Renaissance. Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky, 1988. Copyright © 1988 by the UP of Kentucky.Jeffrey Meyers

Like "The Road Not Taken," it suggests vast thematic implications through a lucid narrative. . . .

The most amazing thing about this work is that three of the fifteen lines (the last line repeats the previous one) are transformations from other poems. "He gives his harness bells a shake" comes from Scott's "The Rover" (in Palgrave): "He gave the bridle-reins a shake.: "The woods are lovely, dark and deep" comes from Thomas Lovell Beddoes' "The Phantom Wooer": "Our bed is lovely, dark, and sweet." The concluding "And miles to go before I sleep" comes from Keats' "Keen Fitful Gusts": "And I have many miles on foot to fare." Though these three lines are variations from other poets, Frost, writing in the tradition of English verse, makes them original and new, and integrates them perfectly into his own poem.

The theme of "Stopping by Woods"—despite Frost's disclaimer—is the temptation of death, even suicide, symbolized by the woods that are filling up with snow on the darkest evening of the year. The speaker is powerfully drawn to these woods and—like Hans Castorp in the "Snow' chapter of Mann's Magic Mountain—wants to lie down and let the snow cover and bury him. The third quatrain, with its drowsy, dream-like line: "Of easy wind and downy flake," opposes the horse's instinctive urge for home with the man's subconscious desire for death in the dark, snowy woods. The speaker says, "The woods are lovely, dark and deep," but he resists their morbid attraction.

From Robert Frost: A Biography. Copyright © 1996 by Jeffrey Meyers.Richard Gray

The duality of the narrator's response to the woods is caught in the contrast between the relaxed, conversational idiom of the first three lines (note the gentle emphasis given to ‘think', the briskly colloquial ‘though') and the dream-like descriptive detail and hypnotic verbal music ('watch . . . woods', 'his . . . fill . . . with') of the last. Clearing and wilderness, law and freedom, civilisation and nature, fact and dream: these oppositions reverberate throughout American writing. And they are registered here in Frost's own quietly ironic contrast between the road along which the narrator travels, connecting marketplace to marketplace, promoting community and culture - and the white silence of the woods, where none of the ordinary limitations of the world seem to apply. In a minor key, they are caught also in the implicit comparison between the owner of these woods, who apparently regards them as a purely financial investment (he lives in the village) and the narrator who sees them, at least potentially, as a spiritual one.

This contrast between what might be termed, rather reductively perhaps, 'realistic' and 'romantic' attitudes is then sustained through the next two stanzas: the commonsensical response is now playfully attributed to the narrator's horse which, like any practical being, wants to get on down the road to food and shelter. The narrator himself, however, continues to be lured by the mysteries of the forest just as the Romantic poets were lured by the mysteries of otherness, sleep and death. And, as before, the contrast is a product of tone and texture as much as dramatic intimation: the poem communicates its debate in how it says things as much as in what it says. So, the harsh gutturals and abrupt movement of lines like, 'He gives his harness bells a shake / To ask if there is some mistake', give verbal shape to the matter-of-fact attitude attributed to the horse, just as the soothing sibilants and gently rocking motion of the lines that follow this ('The only other sound's the sweep / Of easy wind and downy flake') offer a tonal equivalent of the strange, seductive world into which the narrator is tempted to move. 'Everything that is written', Frost once said, 'is as good as it is dramatic'; and in a poem like this the words of the poem become actors in the drama.

The final stanza of 'Stopping by Woods' does not resolve its tensions; on the contrary, it rehearses them in particularly memorable language.

But I have promises to keep,

And miles to go before I sleep,

And miles to go before I sleep.

Having paid tribute to the dangerous seductiveness of the woods, the narrator seems to be trying to shake himself back into commonsense reality by invoking his 'promises' or mundane responsibilities. The last line is repeated, however; and while at first it seems little more than a literal reference to the journey he has to complete (and so a way of telling himself to continue on down the road), the repetition gives it particular resonance. This could, after all, be a metaphorical reference to the brief span of human life and the compulsion this puts the narrator under to take risks and explore the truth while he can. Only a few 'miles' to go before 'I sleep' in death: such a chilling memento mori perhaps justifies stopping by the woods in the first place and considering the spiritual quest implicit in the vision they offer. Perhaps: the point is that neither narrator nor reader can be sure. 'The poem is the act of having the thought', Frost insisted; it is process rather than product, it invites us to share in the experiences of seeing, feeling, and thinking, not simply to look at their results. So the most a piece like 'Stopping by Woods' will offer - and it is a great deal - is an imaginative resolution of its tensions: the sense that its conflicts and irresolutions have been given appropriate dramatic expression, revelation and equipoise.

From American Poetry of the Twentieth Century. Copyright © 1990 by Longman Group UK Limited.William H. Pritchard

With respect to his most anthologized poem, "Stopping By Woods. . ." which he called "my best bid for remembrance," such "feats" are seen in its rhyme scheme, with the third unrhyming line in each of the first three stanzas becoming the rhyme word of each succeeding stanza until the last one, all of whose end words rhyme and whose final couplet consists of a repeated "And miles to go before I sleep." Or they can be heard in the movement of the last two lines of stanza three:

To ask if there is some mistake.

The only other sound's the sweep

Of easy wind and downy flake.

As with "Her early leaf's a flower," the contraction effortlessly carries us along into "the sweep / Of easy wind" so that we arrive at the end almost without knowing it.

Discussion of this poem has usually concerned itself with matters of "content" or meaning (What do the woods represent? Is this a poem in which suicide is contemplated?). Frost, accordingly, as he continued to read it in public made fun of efforts to draw out or fix its meaning as something large and impressive, something to do with man's existential loneliness or other ultimate matters. Perhaps because of these efforts, and on at least one occasion—his last appearance in 1962 at the Ford Forum in Boston—he told his audience that the thing which had given him most pleasure in composing the poem was the effortless sound of that couplet about the horse and what it does when stopped by the woods: "He gives his harness bells a shake / To ask if there is some mistake." We might guess that he held these lines up for admiration because they are probably the hardest ones in the poem out of which to make anything significant: regular in their iambic rhythm and suggesting nothing more than they assert, they establish a sound against which the "other sound" of the following lines can, by contrast, make itself heard. Frost's fondness for this couplet suggests that however much he cared about the "larger" issues or questions which "Stopping By Woods . . ." raises and provokes, he wanted to direct his readers away from solemnly debating them; instead he invited them simply to be pleased with how he had put it. He was to say later on about Edwin Arlington Robinson something which could more naturally have been said about himself—that his life as a poet was "a revel in the felicities of language." "Stopping By Woods . . ." can be appreciated only by removing it from its pedestal and noting how it is a miniature revel in such felicities.

From Frost: A Literary Life Reconsidered. Copyright © 1984 by William Pritchard.Derek Walcott

A parody of Frost, on the other hand would use the doggerel of the greeting card. The trap is the poem, which snaps back at us and catches our fingers with the slow revelation of its betraying our sing-along into wisdom. Frost said it with less venom: "A poem begins in delight and ends in wisdom." This leaves out the turmoil contradictions, and anguish of the process, the middle of the journey.

[quotes poem]

And even this poem, we now know, cannot be trusted. "Whose woods these are I think I know." He does know, so why the hesitancy? Certainly, by the end of the line, he has a pretty good guess. No, the subject is not the ownership of the woods, the legal name of their proprietor, it is the fear of naming the woods, of the anthropomorphic heresy or the hubris of possession by owners and poets.

The next line, generally read as an intoned filler for the rhymes, and also praised for the regionality of that "though" as being very American, is a daring, superfluous, and muted parenthesis. "His house is in the village though." Why not? Why shouldn't he live in the woods? What is he scared of? Of possession, of the darkness of the world in the woods, from his safe world of light and known, named things. He's lucky, the frightened poem says while I'm out here in the dark evening with the first flakes of snow beginning to blur my vision and causing my horse to shudder, shake its reins, and ask why we have stopped. The poem darkens with terror in every homily.

From "The Road Taken." In Brodsky, Joseph, Seamus Heaney, and Derek Walcott (eds.) Homage to Robert Frost. New York: Farrar, Strauss, & Giroux, 1996.Karen L. Kilcup

The poem as a whole, of course, encodes many of the tensions between popular and elite poetry. For example, it appears in an anthology of children's writing alongside Amy Lowell's "Crescent Moon," Joyce Kilmer's "Trees," and Edward Lear's "Owl and the Pussy-Cat." Pritchard situates it among a number of poems that "have ... repelled or embarrassed more highbrow sensibilities," which suggests the question: "haven't these poems ['The Pasture,' 'Stopping by Woods...,' 'Birches,' 'Mending Wall'] been so much exclaimed over by people whose poetic taste is dubious or hardly existent, that on these grounds alone Frost is to be distrusted?" The views represented—and the representations of the poem itself, affiliated with the work of Dickinson, Longfellow, Dante, and the Romantics—range from emphasis on its gentility to its modernist ambiguity. Nevertheless, more than one critic underscores its threat to individualism, its "dangerous prospect of boundarilessness," which suggests the masculine conception of poetic selfhood with which the poem is commonly framed.

. . . .

Seasons were a conventional means to illustrate feelings, as in Helen Hunt Jackson's "'Down to Sleep'":

November days are clear and bright;

Each noon burns up the morning's chill;

The morning's snow is gone by night;

Each day my steps grow slow, grow light,

As through the woods I reverent creep,

Watching all things lie "down to sleep." I never knew before what beds,

Fragrant to smell, and soft to touch,

The forest sifts and shapes and spreads;

I never knew before how much

Of human sound there is in such

Low tones as through the forest sweep

When all wild things lie "down to sleep." Each day I find new coverlids

Tucked in and more sweet eyes shut tight;

Sometimes the viewless mother bids

Her ferns kneel down full in my sight;

I hear their chorus of "good night,"

And half I smile, and half I weep,

Listening while they lie "down to sleep." November woods are bare and still;

November days are bright and good;

Life's noon burns up life's morning chill;

Life's night rests feet which long have stood;

Some warm soft bed, in field or wood,

The mother will not fail to keep,

Where we can "lay us down to sleep.”

Jackson's poem relies on associations with the mother as well as the seasonal metaphor to make its point, making explicit what Frost's intimates: his speaker's desire to merge with the lovely, snow-clad woods suggests a desire to merge with the mother (Mother Nature) as strong as Jackson's. Having removed the traces of religiosity encoded in the refrain "down to sleep," a child's nighttime prayer to God, Frost's speaker nevertheless evinces his prayerful attitude in "the woods are lovely, dark and deep," as well is in the hymnlike regularity of the stanzas. And, in the affectionate reference to "my little horse" reminiscent of the cow-calf image in "The Pasture," he suggests the connection between human and animal parallel to Jackson's explicit observation: "I never knew before how much / Of human sound there is in such / Low tones as through the forest sweep / When all wild things lie 'down to sleep.'" "Sweep," of course, recurs in Frost's quiet poem: "The only other sound's the sweep / Of easy wind and downy flake." Though probably accidental, Frost's echoing of the sweep-sleep rhyme indicates some of the emotional resonances and connections, especially with "weep," itself embedded in "sweep," that are explicit in Jackson. Finally, Jackson's narrator acknowledges only slightly more directly the movement toward age and death that Frost's suggests: "Each day my steps grow slow, grow light / As through the woods I reverent creep." The subjectivity of both Frost's and Jackson's poems is simultaneously individual and representative, suggesting that "Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening" is a feminine poem with close connections to its popular antecedents.

Once again we can trace the emotional resonance of Frost's poem back to the concrete situation that helped engender it. Shortly before Christmas of 1905, Frost had made an unsuccessful trip into town to sell eggs in order to raise money for his children's Christmas presents. "Alone in the driving snow, the memory of his years of hopeful but frustrated struggle welled up, and he let his long-pent feelings out in tears." The intensity of this tearful moment translates into the affective content that permeates but never overwhelms "Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening." The fact that the poem would be written seventeen years after the moment that it reflected testifies to the deep suffering that this experience engendered; too painful to be dwelt upon, it would be only with time and distance that the emotions of that awful moment could be balanced, in a "momentary stay against confusion," by the comforting restraint of formal expression.

"Stopping by Woods" provides a doorway into an understanding of the poet's great popularity with "ordinary" readers. Jarrell observes, "ordinary readers think Frost the greatest poet alive, and love some of his best poems almost as much as they love some of his worst ones. He seems to them a sensible, tender, humorous poet who knows all about trees and farms and folks in New England." This view crashes with that of "intellectuals," who have "neglected or depreciated" him: "the reader of Eliot or Auden usually dismisses Frost as something inconsequentially good that he knew all about long ago."

From Karen L. Kilcup. Robert Frost and Feminine Literary Tradition. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1998: 45, 46-47.'''Mark Richardson

The idea that the "inner" materials of the artist are "re-formed" by the "outer" materials in which he works helps us understand the implications of the reading of "Stop- ping by Woods on a Snowy Evening" given by Frost himself in "The Constant Symbol." Much commentary on "Stopping by Woods" has suggested that the poem expresses a complicated desire for self-annihilation. The idea is well handled by Richard Poirier in Robert Frost: The Work of Knowing: "The recognition of the power of nature, especially of snow, to obliterate the limits and boundaries of things and of his own being is, in large part, a function here of some furtive impulse toward extinction, an impulse no more predominate in Frost than in nature" (181). Frank Lentricchia makes a similar point about Frost's winter landscapes in general and quotes an especially apposite passage from Gas- ton Bachelard's The Poetics of Space: "In the outside world, snow covers all tracks, blurs the road, muffles every sound, conceals all colors. As a result of this universal whiteness, we feel a form of cosmic negation in action" (qtd. in Lentricchia, Landscapes 31).

During Frost's own lifetime, however, the matter was often handled much less sensitively. Indeed, critics sometimes set his teeth on edge with intimations about personal themes in the poem, as if it expressed a wish quite literally for suicide or marked some especially dark passage in the poet's life. Louis Mertins quotes him in conversation (and similar remarks may be found in transcripts of a number of Frost's public readings):

I suppose people think I lie awake nights worrying about what people like [John] Ciardi of the Saturday Review write and publish about me [in 19S8]…Now Ciardi is a nice fellow—one of those bold, brassy fellows who go ahead and say all sorts of things. He makes my "Stopping By Woods" out a death poem. Well, it would be like this if it were. I'd say, "This is all very lovely, but I must be getting on to heaven." There'd be no absurdity in that. That's all right, but it's hardly a death poem. Just as if I should say here tonight, "This is all very well, but I must be getting on to Phoenix, Arizona, to lecture there." [Mertins 371]

As does Eliot, Frost often couples suggestions 0f private sorrows and griefs with statements about their irrelevance. William Pritchard describes the practice well in pointing out how Frost typically "[holds] back any particular reference to his private sorrows while bidding us to respond to the voice of a man who has been acquainted with grief" (230). It is worth bearing in mind that, later in the conversation with Mertins, Frost says: "If you feel it, let's just exchange glances and not say anything about it. There are a lot of things between best friends that're never said, and if you—if they're brought out, right out, too baldly, something's lost" (371-72). To similar effect, he writes in a letter to Sidney Cox: "Poetry...is a measured amount of all we could say an we would. We shall be judged finally by the delicacy of our feeling for when to stop short. The right people know, and we artists should know better than they know" (CPPP 714). I think of Eliot in "Tradition and the Individual Talent": "Poetry is not a turning loose of emotion, but an escape from emotion; it is not the expression of personality, but an escape from personality. But, of course, only those who have personality and emotions know what it means to want to escape from these things" (Selected Essays 10-11). He has in mind exactly the sort of readers and writers Frost acknowledges here: "The right people know, and we artists should know better than they know." In any event, Frost’s subtle caveat to Mertins is probably meant equally to validate Ciardi's suggestion about "Stopping by Woods" and to lay a polite injunction against it.

But his turning aside of Ciardi's reading is more than an example of tact. He speaks out of fidelity to his belief that the emotions that give rise to a poem are in some way alienated by it in the result, and his alternative reading of "Stopping by Woods" is worth dwelling on as a roundabout contribution to the theory of personality and motive in poetry. Frost directs our attention not to the poem's theme or content but to its form: the interlocking pattern of rhyme among the stanzas. He once remarked to an audience at Bread Loaf, again discouraging biographical or thematic readings of the poem: "If I were reading it for someone else, I'd begin to wonder what he's up to. See. Not what he means but what he's up to" (Cook 81). The emphasis is on the performance of the writer and on the act of writing. Following are Frost's brief comments on it in "The Constant Symbol":

There's an indulgent smile I get for the recklessness of the unnecessary commitment I made when I came to the first line in the second stanza of a poem in this book called "Stopping By Woods On a Snowy Evening." I was riding too high to care what trouble I incurred. And it was all right so long as I didn't suffer deflection. (CPPP 788)

In emphasizing the lyric's form Frost really only defers the question of theme or content. It is not that the poem does not have a theme, or one worth a reader's consideration; the form simply is the theme. If this seems surprising, it is only because Frost's emphasis makes for so complete a reversal in mood. The mood of the poem at this second level of form-as-theme is anything but suggestive of self-annihilation: "I was riding too high to care what trouble I incurred." This is the kind of transformation Poirier has in mind when he remarks in The Performing Self (1971), quoting an interview with Frost originally published in the Paris Review in 1960: "If [a] poem expresses grief, it also expresses—as an act, as a composition, a performance, a 'making,'—the opposite of grief; it shows or expresses 'what a hell of a good time I had writing it'" (892). I would point out further that Frost's reading, appearing as it does in "The Constant Symbol," lends the last two lines of "Stopping by Woods" added resonance: "promises" are still the concern, though in "The Constant Symbol" he speaks of them as "commitments" to poetic form. Viewed in these terms "Stopping by Woods" dramatizes the artist's negotiation of the responsibilities of his craft. What may seem to most readers hardly a metapoetical lyric actually speaks to the central concern of the poet as a poet when the form of the poem is taken as its theme.

The question immediately presents itself, however, of a possible disjunction between form and theme, even as they seem to work in tandem. The "unnecessary commitment" that exhilarated Frost-the rhyme scheme—does in fact "suffer deflection" in the last stanza: here there are four matched end rhymes, not three. Promises are broken, not kept, as Frost relinquishes the pattern he carried through the first three stanzas. Of course, as John Ciardi points out in the Saturday Review article alluded to above, this relinquishment is really built into the design itself: the only way not to break the pattern would have been to rhyme the penultimate line 0f the poem with the first, thereby creating a symmetrical, circular rhyme scheme. Frost chose not to keep this particular promise, with the result that the progress of the poem illustrates one form of the lassitude that it apparently resigns itself to being a stay against-to put the matter somewhat paradoxically. Paradox is only fitting, however, in acknowledging the mixture of motives animating the poem: motives, on the one hand, of self-relinquishment in what Poirier calls Frost's "recognition of the power of nature...to obliterate the limits and boundaries of things and of his own being"; and motives, on the other hand, of self-assertion and exhilaration in what Frost calls the experience of "riding ...high." Frost's remark about Robinson's poetry in the introduction to King Jasper seems to apply rather well to "Stopping by Woods": "So sad and at the same time so happy in achievement" (CPPP 747].

A slighter example of dark emotion redeemed by poetic form and thereby brought to happy achievement is Frost's little poem "Beyond Words":

Feels like my armory of hate;

And you, you ...you, you utter…

You wait!

If the hatred truly were "beyond words" it could not have found expression, let alone expression in a poem. Here, form has "disciplined" the hatred to which the lines allude into the obviously very different mood and feeling that we get from reading the poem itself. The playful rhyme of "gutter" to "utter" has the peculiar subsidiary grace of suggesting the guttural tone in which the poem thinks of itself as being uttered. In his "'Letter' to The Amherst Student" Frost says that, so long as we have form to go on, we are "lost to the larger excruciations" (CPPP 740). "Beyond Words" helps us see what he means. Resources of rhythm and rhyme transform darker, chaotic emotions into the lighter, altogether more manageable one of what Frost liked to call "play." In "Beyond Words" this "play" is also felt in the tension between the iambic rhythms that underlie the lines and the more agitated rhythms of the spoken phrases. The only true "materialist," Frost explains in "Education by Poetry," is the person who gets "lost in his material" without a guiding metaphor to throw it into shape (CPPP 724). Here, a metaphor comparing icicles along a gutter to an "armory of hate," together with the sonic equation of "gutter" to "utter," essentially tame a troubling experience. "Beyond Words" offers an example of how hatred can find a profitable, even redemptive outlet—just as an urge toward self-relinquishment may find its outlet in "Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening."

———————-

Another implication of Frost's reading of "Stopping by Woods" is that any distinction between form and theme must remain provisional. Relative to readings of "Stopping by Woods" as a poem concerned with possibilities of self-annihilation, Frost’s own reading seems rather too exclusively fixed upon form and doubtless has struck many readers as evasive. But in the context of the essay in which his reading of the poem appears, "The Constant Symbol," that reading is quite thematic in its concerns, not at all formalistic—as should presently become clear. And in the larger work comprising both the poem and his commentary on it, Frost is in fact interested in destabilizing the oppositions of theme to form and of content to form.

Three terms concern us: content, theme, form. In approaching some poems it is necessary first to describe the content. Reading Wallace Stevens's poem "The Emperor of Ice Cream," for example, we may say that it describes a funeral—a statement about content. (By contrast, nothing could be plainer than the content of most of Frost's lyrics, especially "Stopping by Woods.") In any event a critic needs some intelligible ground against which to work in speaking of the theme, or if you prefer, the "concern" of the poem—what it aims to draw our attention to as readers of poetry. What the poem "has in mind" is not to be confused with what it "has in view," though the two categories often overlap. "The Emperor of Ice Cream" may or may not have a funereal theme; "Stopping by Woods" mayor may not be "thinking" of a man in a sleigh. Form is still another matter, and to address it a critic usually has to define and stabilize for purposes of investigation some notion of theme to work against. Which yields these three (somewhat unstable) concepts: what a poem describes—its content; what it has in mind—its theme; and how it holds together—its form.

Whatever a critic's terminology, it is perhaps inevitable that she rely on each of these concepts. I am suggesting that Frost's critical theory and practice show how they are exchangeable: each term must be considered for its place in a kind of escalation of significance in which theme, form, and content change places. This is, it seems to me, the meaning of Frost's definition in "The Constant Symbol": "Every poem is an epitome of the great predicament; a figure of the will braving alien entanglements" (CPPP 787). Here is a theme which is not one: that is to say, a theme which stands in no comfortable opposition either to content or form. "Figure" works in three senses here: in the sense of metaphor; in the sense of "subject" or "theme," as when we say that a painting is of a human figure; and in the sense of "pattern" or form. The "figure" or pattern a poem makes may "pose" and become either the content or the theme of a particular poem; that is, a poem may either have that pattern "in view" or "in mind." In Frost's reading of "Stopping by Woods," for example, the figure that poem makes, its rhyme and stanza scheme, becomes its "figure" or theme. But it is not enough to say that a poem is a "figure"—whether we mean metaphor or theme—of the will braving alien entanglements: it is also an example of it, not merely a representation, and this directs our attention to the act of description in a poem rather than to the things it describes. More precisely, it extends the category of "things described" (the content) to include also the act of description. Considered in this light the content of every poem "written regular" (as Frost says) is this "figure of the will braving alien entanglements." His reading plainly undermines the distinction between form and content: the container becomes the thing contained—which brings us to the very heart of the matter. This exchange and merger of container and contained—of outside and inside, form and content—is central to Frost's understanding of motive. When he writes to Lesley Frost: "I want to be good, but that is not enough the state says I have got to be good," the observation quite naturally occurs to him in connection with a discussion of form in poetry. This suggests the broader implications of the fact that outer motivations become indistinguishable from the inner motivations of the agent—whether he is a poet writing a poem or a citizen simply endeavoring to be good. It is as impossible to define the essential motive of "Stopping by Woods"—intrinsic? extrinsic? personal? formal?—as it would be to define the essential motive of the desire to be virtuous. In both cases the motive is the product, not the antecedent, of engagements with alien entanglements—that is, with the coercive motives, however benign, of form and state.

Since this points to the indissociability of external and internal motivations it naturally bears closely on the question of personality in poetry. To say that a poet "expresses" himself is to assign priority to intrinsic motives as against extrinsic ones and to elevate autobiographical impulses above the act of composition. Furthermore, in putting content above form, expressive theories of poetry necessarily assume a stable opposition of message to vehicle, in which the former remains uncontaminated by the latter. Thinking of poetry in terms of expression inevitably engages the battery of assumptions Derrida skeptically describes in "Signature Event Context": "If men write it is: (1) because they have to communicate; (2) because what they have to communicate is their 'thought,' their 'ideas,' their representations. Thought, as representation, precedes and governs communication, which transports the 'idea,' the signified content." In Frost's Derridean-Burkean grammar the sentence must always read: a poem is expressed, which captures the mixture of external and internal motives he finds in himself and in writing. No pure governing intention precedes a poem to be embodied in it. We must speak instead of a "succession" of intention.

From The Ordeal of Robert Frost: The Poet and His Poetics. Copyright © 1997 by the Board of Trustees of the University of IllinoisThomas C. Harrison

Poets have the whole phonetic structures of their languages to work with when they compose. Some poetic devices such as meter and rhyme are so well represented in the general vocabulary as to need little comment, but subtler effects that poets presumably put into their work, and that readers or listeners get "by feel," may benefit from a closer, and perhaps more specialized, analysis. Two examples that show particularly well how a poet slows the reader down at the appropriate spots, especially one reading aloud, are cited below. One is from Robert Frost's "Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening," the other from Theodore Roethke's "The Bat."

English vowels come in tense and lax pairs: beet-bit, bait-bet, pool-pull, pole-Paul. Tips of finger and thumb pressed up into the soft tissue behind the chin while one repeats beet-bit will show why they are called tense and lax. Tense vowels take longer to say than lax ones (although it is vowel quality, not length, that is distinctive in English).

Diphthongs, two vowels at a time—the diphthong in bite (a sound spelled ai in romance languages) and the au diphthong in house—also take longer to say. Other sounds that add length to words are fricatives-f, v, s, z, sh, and the voiced version of sh found in pleasure. They are called fricatives because the air flowing through the vocal tract produces friction that creates their distinctive sounds. These sounds have a duration that stops-p, t, k, b, d, g—do not have. In addition to fricatives, nasals—m, n, and the consonant at the end of sing, which is a single consonant although spelled with two letters—have duration and add length. Finally, liquids—l and r—add length.

These consonants slow things down especially when they come in clusters, for example, in strengths, which has an intrusive k in the pronunciation of most Americans, making it sound like "strengkths." This give it seven consonants, three before and four after the vowel, and make it the most complex syllable in English.

When Robert Frost gets to the heart of his poem in the third stanza of "Stopping by Woods," he uses all these devices:

To ask if there is some mistake.

The only other sound's the sweep

Of easy wind and downy flake.

What happens in the poem happens in the last two lines of this stanza, leading to "The woods are lovely, dark and deep," where the speaker is about to fall face-first into the snow. Start with "only," with tense vowel followed by nasal and liquid. "Sound's" begins with a sibilant fricative, followed by a diphthong, followed by a consonant cluster ndz, nasal, stop, and fricative. In the last line, "easy" has a tense vowel and fricative, and "downy" a diphthong followed by a nasal.

Add to these effects those of alliteration ("only other," "sound's [. . .] sweep") and assonance ("sound's [. . .] downy," "sweep [. . .] easy"), and the poem, which has been moving along at a fairly brisk pace, stops attentive readers—especially those reading aloud—and squeezes them through a dense sieve of sound. Then we are almost ready to fall into the snow with the speaker.

[. . . .]

In each of these rather different poems the poet has made conscious use of poetic devices . . . . They also take advantage of other characteristics of language that, regrettably, may not be so readily understood because only certain specialists have the language needed to interpret them.

From The Explicator 59.1 (Fall 2000)'''Clint Stevens''

This is an elegant poem. It is by no means the most psychologically rich poem Frost ever wrote, yet in its starkness and clarity we as readers only benefit. Perhaps the first thing we notice is that the poem is an interior monologue. The first line establishes the tone of a person musing quietly to himself on the situation before him: "Whose woods these are I think I know." He pauses here on "the darkest evening of the year," the point in time poised between the day and the night, between consciousness and unconsciousness, between waking and sleeping, between life and oblivion. There is a slight lack of surety in the speaker saying to himself, "I think I know," thus again signifying the meeting ground between what he knows and what he does not. These antimonies, his lack of certainty, and the muted sense of passion provide the tension by which the poem operates.

The reader will notice along with this that the first line consists entirely of monosyllables. Typically, monosyllabic lines are difficult to scan, yet Frost, having written the poem almost entirely in monosyllables demonstrates by this his technical prowess, as the poem scans in perfect iambic tetrameter. And so, any lack of certainty we might first suspect is smoothed over by this regular rhythm. Frost, likewise, stabilizes the poem by the rhyme scheme of aaba/ bbcb/ ccdc/ dddd, without a single forced rhyme. This combination of regular rhythms and rhymes produces a pleasant hypnotic effect, which only increases as the poem progresses. Richard Gray has marked this in explaining how the poem moves from a more conversational tone to the charming effect that characterizes the ending. The language does indeed demonstrate this change: we move from the colloquial "His house is in the village though" to the poetic "Of easy wind and downy flake// The woods are lovely, dark and deep."

If there is any generalization that is apt to describe Frost’s poetics, it is that his characters are almost always of two minds. John Ogilvie has noted the slight contrast between the speaker’s public obligations and his private will. The speaker, we may assume, is "half in love with easeful death." Yet, though the poem is an interior monologue, the speaker does not look inward; rather, he focuses on recreating in his imagination the sense of his surroundings. Indeed, he seems much more conscious of his surroundings than he is of the inner-workings of his mind (which, at least for the reader remain nearly as inscrutable as the dark woods). In such a way, the speaker by implication hints that the outer-wilderness corresponds to his inner one. This is of course most evident in the final refrain in which the outward journey becomes a symbol for his inner journey, but it is furthered by the concentration on his perception of his surroundings; in other words, by opening his mind to the surroundings rather than sealing it off in self-referential language, he becomes what he beholds, or, to quote another poem which most certainly was influenced by this one:

To regard the frost and the boughs

Of the pine-trees crusted with snow

Richard Poirier has marked that "woods" is mentioned four times in the poem. Along with this the reader will note that "I" is mentioned five times. These two realities, the subjective and the objective, are merged over the course of the poem. Such that, while the speaker focuses almost exclusively on the physical fact of his surroundings, he is at the same time articulating his own mental landscape, which seems ever-intent "to fade far away, dissolve, and quite forget." There is in the end the uncertainty in choosing between his death impulse and his desire to continue on the road of life. Which wins in the end, I think I know, but it scarcely matters; the speaker has had his solitary vision; whether he stays or goes, the woods will go with him and the reader, who are now well-acquainted with the coming night.

Copyright © 2003 Clint Stevens