_and_brother_Ronald_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

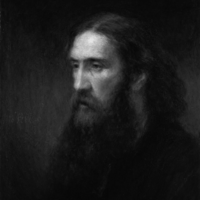

George MacDonald

George MacDonald (10 December 1824– 18 September 1905) was a Scottish author, poet, and Christian minister. He was a pioneering figure in the field of fantasy literature and the mentor of fellow writer Lewis Carroll. His writings have been cited as a major literary influence by many notable authors including W. H. Auden, C. S. Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien, Walter de la Mare, E. Nesbit and Madeleine L’Engle. C. S. Lewis wrote that he regarded MacDonald as his “master”: “Picking up a copy of Phantastes one day at a train-station bookstall, I began to read. A few hours later,” said Lewis, “I knew that I had crossed a great frontier.” G. K. Chesterton cited The Princess and the Goblin as a book that had “made a difference to my whole existence”.

George MacDonald (10 December 1824– 18 September 1905) was a Scottish author, poet, and Christian minister. He was a pioneering figure in the field of fantasy literature and the mentor of fellow writer Lewis Carroll. His writings have been cited as a major literary influence by many notable authors including W. H. Auden, C. S. Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien, Walter de la Mare, E. Nesbit and Madeleine L’Engle. C. S. Lewis wrote that he regarded MacDonald as his “master”: “Picking up a copy of Phantastes one day at a train-station bookstall, I began to read. A few hours later,” said Lewis, “I knew that I had crossed a great frontier.” G. K. Chesterton cited The Princess and the Goblin as a book that had “made a difference to my whole existence”.

Elizabeth Yates wrote of Sir Gibbie, “It moved me the way books did when, as a child, the great gates of literature began to open and first encounters with noble thoughts and utterances were unspeakably thrilling.”

Even Mark Twain, who initially disliked MacDonald, became friends with him, and there is some evidence that Twain was influenced by MacDonald. Christian author Oswald Chambers (1874–1917) wrote in Christian Disciplines, vol. 1, (pub. 1934) that “it is a striking indication of the trend and shallowness of the modern reading public that George MacDonald’s books have been so neglected”.

In addition to his fairy tales, MacDonald wrote several works on Christian apologetics including several that defended his view of Christian Universalism.

Early life

George MacDonald was born on 10 December 1824 at Huntly, Aberdeenshire, Scotland. His father, a farmer, was one of the MacDonalds of Glen Coe, and a direct descendant of one of the families that suffered in the massacre of 1692. The Doric dialect of the Aberdeenshire area appears in the dialogue of some of his non-fantasy novels.

MacDonald grew up in the Congregational Church, with an atmosphere of Calvinism. But MacDonald never felt comfortable with some aspects of Calvinist doctrine; indeed, legend has itt that when the doctrine of predestination was first explained to him, he burst into tears (although assured that he was one of the elect). Later novels, such as Robert Falconer and Lilith, show a distaste for the idea that God’s electing love is limited to some and denied to others.

MacDonald graduated from the University of Aberdeen, and then went to London, studying at Highbury College for the Congregational ministry.

In 1850 he was appointed pastor of Trinity Congregational Church, Arundel, but his sermons (preaching God’s universal love and the possibility that none would, ultimately, fail to unite with God) met with little favour and his salary was cut in half. Later he was engaged in ministerial work in Manchester. He left that because of poor health, and after a short sojourn in Algiers he settled in London and taught for some time at the University of London. MacDonald was also for a time editor of Good Words for the Young, and lectured successfully in the United States during 1872–1873.

Work

George MacDonald’s best-known works are Phantastes, The Princess and the Goblin, At the Back of the North Wind, and Lilith, all fantasy novels, and fairy tales such as “The Light Princess”, “The Golden Key”, and “The Wise Woman”. “I write, not for children,” he wrote, “but for the child-like, whether they be of five, or fifty, or seventy-five.” MacDonald also published some volumes of sermons, the pulpit not having proved an unreservedly successful venue.

MacDonald also served as a mentor to Lewis Carroll (the pen-name of Rev. Charles Lutwidge Dodgson); it was MacDonald’s advice, and the enthusiastic reception of Alice by MacDonald’s many sons and daughters, that convinced Carroll to submit Alice for publication. Carroll, one of the finest Victorian photographers, also created photographic portraits of several of the MacDonald children.

MacDonald was also friends with John Ruskin and served as a go-between in Ruskin’s long courtship with Rose La Touche.

MacDonald was acquainted with most of the literary luminaries of the day; a surviving group photograph shows him with Tennyson, Dickens, Wilkie Collins, Trollope, Ruskin, Lewes, and Thackeray. While in America he was a friend of Longfellow and Walt Whitman.

In 1877 he was given a civil list pension. From 1879 he and his family moved to Bordighera in a place much loved by British expatriates, the Riviera dei Fiori in Liguria, Italy, almost on the French border. In that locality there also was an Anglican Church, which he attended. Deeply enamoured of the Riviera, he spent there 20 years, writing almost half of his whole literary production, especially the fantasy work. In that Ligurian town MacDonald founded a literary studio named Casa Coraggio (Bravery House), which soon became one of the most renowned cultural centres of that period, well attended by British and Italian travellers, and by locals. In that house representations were often held of classic plays, and readings were given of Dante and Shakespeare.

In 1900 he moved into St George’s Wood, Haslemere, a house designed for him by his son, Robert Falconer MacDonald, and the building overseen by his eldest son, Greville MacDonald. He died on 18 September 1905 in Ashtead, (Surrey). He was cremated and his ashes buried in Bordighera, in the English cemetery, along with his wife Louisa and daughters Lilia and Grace.

As hinted above, MacDonald’s use of fantasy as a literary medium for exploring the human condition greatly influenced a generation of such notable authors as C. S. Lewis (who featured him as a character in his The Great Divorce), J. R. R. Tolkien, and Madeleine L’Engle. MacDonald’s non-fantasy novels, such as Alec Forbes, had their influence as well; they were among the first realistic Scottish novels, and as such MacDonald has been credited with founding the “kailyard school” of Scottish writing.

His son Greville MacDonald became a noted medical specialist, a pioneer of the Peasant Arts movement, and also wrote numerous fairy tales for children. Greville ensured that new editions of his father’s works were published. Another son, Ronald MacDonald, was also a novelist. Ronald’s son, Philip MacDonald, (George MacDonald’s grandson) became a very well known Hollywood screenwriter.

Theology

MacDonald rejected the doctrine of penal substitutionary atonement as developed by John Calvin, which argues that Christ has taken the place of sinners and is punished by the wrath of God in their place, believing that in turn it raised serious questions about the character and nature of God. Instead, he taught that Christ had come to save people from their sins, and not from a Divine penalty for their sins. The problem was not the need to appease a wrathful God but the disease of cosmic evil itself. George MacDonald frequently described the Atonement in terms similar to the Christus Victor theory. MacDonald posed the rhetorical question, “Did he not foil and slay evil by letting all the waves and billows of its horrid sea break upon him, go over him, and die without rebound—spend their rage, fall defeated, and cease? Verily, he made atonement!”

MacDonald was convinced that God does not punish except to amend, and that the sole end of His greatest anger is the amelioration of the guilty. As the doctor uses fire and steel in certain deep-seated diseases, so God may use hell-fire if necessary to heal the hardened sinner. MacDonald declared, “I believe that no hell will be lacking which would help the just mercy of God to redeem his children.” MacDonald posed the rhetorical question, “When we say that God is Love, do we teach men that their fear of Him is groundless?” He replied, “No. As much as they fear will come upon them, possibly far more.... The wrath will consume what they call themselves; so that the selves God made shall appear.”

However, true repentance, in the sense of freely chosen moral growth, is essential to this process, and, in MacDonald’s optimistic view, inevitable for all beings (see universal reconciliation). He recognised the theoretical possibility that, bathed in the eschatological divine light, some might perceive right and wrong for what they are but still refuse to be transfigured by operation of God’s fires of love, but he did not think this likely.

In this theology of divine punishment, MacDonald stands in opposition to Augustine of Hippo, and in agreement with the Greek Church Fathers Clement of Alexandria, Origen, and St. Gregory of Nyssa, although it is unknown whether MacDonald had a working familiarity with Patristics or Eastern Orthodox Christianity. At least an indirect influence is likely, because F. D. Maurice, who influenced MacDonald, knew the Greek Fathers, especially Clement, very well. MacDonald states his theological views most distinctly in the sermon Justice found in the third volume of Unspoken Sermons.

In his introduction to George MacDonald: An Anthology, C. S. Lewis speaks highly of MacDonald’s theology:

Bibliography

Fantasy

Phantastes: A Fairie Romance for Men and Women (1858)

“Cross Purposes” (1862)

Adela Cathcart (1864), containing “The Light Princess”, “The Shadows”, and other short stories

The Portent: A Story of the Inner Vision of the Highlanders, Commonly Called “The Second Sight” (1864)

Dealings with the Fairies (1867), containing “The Golden Key”, “The Light Princess”, “The Shadows”, and other short stories

At the Back of the North Wind (1871)

Works of Fancy and Imagination (1871), including Within and Without, “Cross Purposes”, “The Light Princess”, “The Golden Key”, and other works

The Princess and the Goblin (1872)

The Wise Woman: A Parable (1875) (Published also as “The Lost Princess: A Double Story”; or as “A Double Story”.)

The Gifts of the Child Christ and Other Tales (1882; republished as Stephen Archer and Other Tales)

The Day Boy and the Night Girl (1882)

The Princess and Curdie (1883), a sequel to The Princess and the Goblin

The Flight of the Shadow (1891)

Lilith: A Romance (1895)

Realistic fiction

David Elginbrod (1863; republished as The Tutor’s First Love), originally published in three volumes

Alec Forbes of Howglen (1865; republished as The Maiden’s Bequest)

Annals of a Quiet Neighbourhood (1867)

Guild Court: A London Story (1868)

Robert Falconer (1868; republished as The Musician’s Quest)

The Seaboard Parish (1869), a sequel to Annals of a Quiet Neighbourhood

Ranald Bannerman’s Boyhood (1871)

Wilfrid Cumbermede (1871–72)

The Vicar’s Daughter (1871–72), a sequel to Annals of a Quiet Neighborhood and The Seaboard Parish

The History of Gutta Percha Willie, the Working Genius (1873), usually called simply Gutta Percha Willie

Malcolm (1875)

St. George and St. Michael (1876)

Thomas Wingfold, Curate (1876; republished as The Curate’s Awakening)

The Marquis of Lossie (1877; republished as The Marquis’ Secret), the second book of Malcolm

Paul Faber, Surgeon (1879; republished as The Lady’s Confession), a sequel to Thomas Wingfold, Curate

Sir Gibbie (1879; republished as The Baronet’s Song)

Mary Marston (1881; republished as A Daughter’s Devotion)

Warlock o’ Glenwarlock (1881; republished as Castle Warlock and The Laird’s Inheritance)

Weighed and Wanting (1882; republished as A Gentlewoman’s Choice)

Donal Grant (1883; republished as The Shepherd’s Castle), a sequel to Sir Gibbie

What’s Mine’s Mine (1886; republished as The Highlander’s Last Song)

Home Again: A Tale (1887; republished as The Poet’s Homecoming)

The Elect Lady (1888; republished as The Landlady’s Master)

A Rough Shaking (1891)

There and Back (1891; republished as The Baron’s Apprenticeship), a sequel to Thomas Wingfold, Curate and Paul Faber, Surgeon

Heather and Snow (1893; republished as The Peasant Girl’s Dream)

Salted with Fire (1896; republished as The Minister’s Restoration)

Far Above Rubies (1898)

Poetry

Twelve of the Spiritual Songs of Novalis (1851), privately printed translation of the poetry of Novalis

Within and Without: A Dramatic Poem (1855)

Poems (1857)

“A Hidden Life” and Other Poems (1864)

“The Disciple” and Other Poems (1867)

Exotics: A Translation of the Spiritual Songs of Novalis, the Hymn-book of Luther, and Other Poems from the German and Italian (1876)

Dramatic and Miscellaneous Poems (1876)

Diary of an Old Soul (1880)

A Book of Strife, in the Form of the Diary of an Old Soul (1880), privately printed

The Threefold Cord: Poems by Three Friends (1883), privately printed, with Greville Matheson and John Hill MacDonald

Poems (1887)

The Poetical Works of George MacDonald, 2 Volumes (1893)

Scotch Songs and Ballads (1893)

Rampolli: Growths from a Long-planted Root (1897)

Nonfiction

Unspoken Sermons (1867)

England’s Antiphon (1868, 1874)

The Miracles of Our Lord (1870)

Cheerful Words from the Writing of George MacDonald (1880), compiled by E. E. Brown

Orts: Chiefly Papers on the Imagination, and on Shakespeare (1882)

“Preface” (1884) to Letters from Hell (1866) by Valdemar Adolph Thisted

The Tragedie of Hamlet, Prince of Denmarke: A Study With the Test of the Folio of 1623 (1885)

Unspoken Sermons, Second Series (1885)

Unspoken Sermons, Third Series (1889)

A Cabinet of Gems, Cut and Polished by Sir Philip Sidney; Now, for the More Radiance, Presented Without Their Setting by George MacDonald (1891)

The Hope of the Gospel (1892)

A Dish of Orts (1893)

Beautiful Thoughts from George MacDonald (1894), compiled by Elizabeth Dougall

In popular culture

(Alphabetical by artist)

Christian celtic punk band Ballydowse have a song called “George MacDonald” on their album Out of the Fertile Crescent. The song is both taken from MacDonald’s poem “My Two Geniuses” and liberally quoted from Phantastes.

American classical composer John Craton has utilized several of MacDonald’s stories in his works, including “The Gray Wolf” (in a tone poem of the same name for solo mandolin– 2006) and portions of “The Cruel Painter”, Lilith, and The Light Princess (in Three Tableaux from George MacDonald for mandolin, recorder, and cello– 2011).

Contemporary new-age musician Jeff Johnson wrote a song titled “The Golden Key” based on George MacDonald’s story of the same name. He has also written several other songs inspired by MacDonald and the Inklings.

Jazz pianist and recording artist Ray Lyon has a song on his CD Beginning to See (2007), called “Up The Spiral Stairs”, which features lyrics from MacDonald’s 26 and 27 September devotional readings from the book Diary of an Old Soul.

A verse from The Light Princess is cited in the “Beauty and the Beast” song by Nightwish.

Rock group The Waterboys titled their album Room to Roam (1990) after a passage in MacDonald’s Phantastes, also found in Lilith. The title track of the album comprises a MacDonald poem from the text of Phantastes set to music by the band. The novels Lilith and Phantastes are both named as books in a library, in the title track of another Waterboys album, Universal Hall (2003). (The Waterboys have also quoted from C. S. Lewis in several songs, including “Church Not Made With Hands” and “Further Up, Further In”, confirming the enduring link in modern pop culture between MacDonald and Lewis.)

References

Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_MacDonald