Notes

1. I have sent for thee holy friar.

Of the history of Tamerlane little is known; and with that little, I have taken the full liberty of a poet.—That he was descended from the family of Zinghis Khan is more than probable—but he is vulgarly supposed to have been the son of a shepherd, and to have raised himself to the throne by his own address. He died in the year 1405, in the time of Pope Innocent VII.

How I shall account for giving him “a friar,” as a death-bed confessor—I cannot exactly determine. He wanted some one to listen to his tale—and why not a friar? It does not pass the bounds of possibility—quite sufficient for my purpose—and I have at least good authority on my side for such innovations.

2. The mists of the Taglay have shed, &c.

The mountains of Belur Taglay are a branch of the Immaus, in the southern part of Independent Tartary.—They are celebrated for the singular wildness, and beauty of their vallies.

3. No purer thought

Dwelt in a seraph’s breast than thine.

I must beg the reader’s pardon for making Tamerlane, a Tartar of the fourteenth century, speak in the same language as a Boston gentleman of the nineteenth; but of the Tartar mythology we have little information.

4. Which blazes upon Edis’ shrine.

A deity presiding over virtuous love, upon whose imaginary altar, a sacred fire was continually blazing.

5.—————who hardly will conceive

That any should become “great,” born

Born in their own sphere.

Although Tamerlane speaks this, it is not the less true. It is a matter of the greatest difficulty to make the generality of mankind believe that one, with whom they are upon terms of intimacy, shall be called, in the world, a “great man.” The reason is evident. There are few great men. Their actions are consequently viewed by the mass of the people thro’ the medium of distance.—The prominent parts of their character are alone noted; and those properties, which are minute and common to every one, not being observed, seem to have no connection with a great character.

Who ever read the private memorials, correspondence, &c. which have become so common in our time, without wondering that “great men” should act and thnik [think] “so abominably?”

6. Her own Alexis who should plight, &c.

That Tamerlane acquir’d his renown under a feigned name is not entirely a fiction.

7. Look ’round thee now on Samarcand.

I believe it was after the battle of Angoria that Tamerlane made Samarcand his residence. It became for a time the seat of learning and the arts.

8. And who her sov’reign? Timur, &c.

He was called Timur Bek as well as Tamerlane. [back]

9. The Zinghis’ yet re-echoing fame.

The conquests of Tamerlane far exceeded those of Zinghis Khan. He boasted to have two thirds of the world at his command.

10. The sound of the coming darkness (known

To those whose spirits hark’n.)

I have often fancied that I could distinctly hear the sound of the darkness, as it steals over the horizon—a foolish fancy perhaps, but not more unintelligible than to see music—

“The mind the music breathing from her face.”

11. Let life then, as the day-flow’r, fall.

There is a flow’r, (I have never known its botanic name,) vulgarly called the day flower. It blooms beautifully in the day-light, but withers towards evening, and by night its leaves appear totally shrivelled and dead. I have forgotten, however, to mention in the text, that it lives again in the morning. If it will not flourish in Tartary, I must be forgiven for carrying it thither.

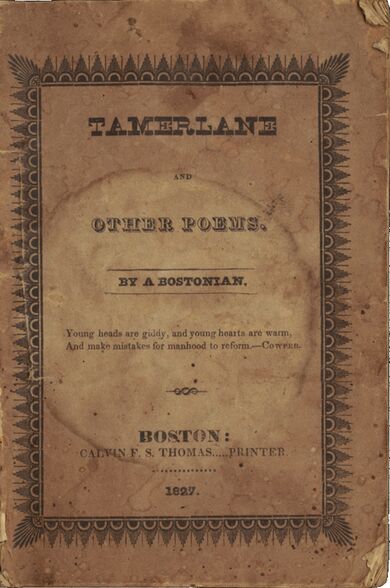

[Although Poe republished “Tamerlane” in all three of his subsequent collections of poems, none of these editions include any notes to the poem.]