Info

Nacimiento de san Juan Bautista

Artemisia Gentileschi

1635

Museo Nacional del Prado

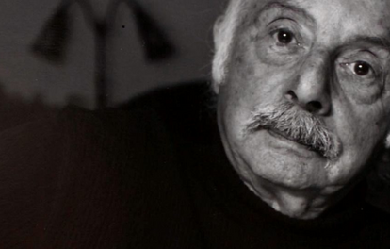

Charles John Huffam Dickens (7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic who is generally regarded as the greatest novelist of the Victorian period and the creator of some of the world's most memorable fictional characters. During his lifetime Dickens' works enjoyed unprecedented popularity and fame, but it was in the twentieth century that his literary genius was fully recognized by critics and scholars. His novels and short stories continue to enjoy an enduring popularity among the general reading public. Born in Portsmouth, England, Dickens left school to work in a factory after his father was thrown into debtors' prison. Though he had little formal education, his early impoverishment drove him to succeed. He edited a weekly journal for 20 years, wrote 15 novels and hundreds of short stories and non-fiction articles, lectured and performed extensively, was an indefatigable letter writer, and campaigned vigorously for children's rights, education, and other social reforms. Dickens rocketed to fame with the 1836 serial publication of The Pickwick Papers. Within a few years he had become an international literary celebrity, celebrated for his humour, satire, and keen observation of character and society. His novels, most published in monthly or weekly instalments, pioneered the serial publication of narrative fiction, which became the dominant Victorian mode for novel publication. The instalment format allowed Dickens to evaluate his audience's reaction, and he often modified his plot and character development based on such feedback. For example, when his wife's chiropodist expressed distress at the way Miss Mowcher in David Copperfield seemed to reflect her disabilities, Dickens went on to improve the character with positive lineaments. Fagin in Oliver Twist apparently mirrors the famous fence, Ikey Solomon; His caricature of Leigh Hunt in the figure of Mr Skimpole in Bleak House was likewise toned down on advice from some of his friends, as they read episodes: In the same novel, both Lawrence Boythorne and Mooney the beadle are drawn from real life – Boythorne from Walter Savage Landor) and Mooney from a certain 'Looney', a beadle at Salisbury Square. Though his plots were carefully constructed, Dickens would often weave in elements harvested from topical events into his narratives. Masses of the illiterate poor chipped in ha'pennies to have each new monthly episode read to them, opening up and inspiring a new class of readers. Dickens was regarded as the 'literary colossus' of his age. His 1843 novella, A Christmas Carol, is one of the most influential works ever written, and it remains popular and continues to inspire adaptations in every artistic genre. His creative genius has been praised by fellow writers—from Leo Tolstoy to G. K. Chesterton and George Orwell—for its realism, comedy, prose style, unique characterisations, and social criticism. On the other hand Oscar Wilde, Henry James and Virginia Woolf complained of a lack of psychological depth, loose writing, and a vein of saccharine sentimentalism. Early years Charles Dickens was born on 7 February 1812, at Landport in Portsea, the second of eight children to John and Elizabeth Dickens. His father was a clerk in the Navy Pay Office and was temporarily on duty in the district. Very soon after the birth of Charles the family moved to Norfolk Street, Bloomsbury, and then, when he was four, to Chatham, Kent, where he spent his formative years until the age of 11. His early years seem to have been idyllic, though he thought himself a "very small and not-over-particularly-taken-care-of boy". Charles spent time outdoors, but also read voraciously, especially the picaresque novels of Tobias Smollett and Henry Fielding. He retained poignant memories of childhood, helped by a near-photographic memory of the people and events, which he used in his writing. His father's brief period as a clerk in the Navy Pay Office afforded him a few years of private education, first at a dame-school, and then at a school run by William Giles, a dissenter, in Chatham. This period came to an abrupt end when, because of financial difficulties, the Dickens family moved from Kent to Camden Town in London in 1822. Prone to living beyond his means, John Dickens was eventually imprisoned in the Marshalsea debtors' prison in Southwark London in 1824. Shortly afterwards, his wife and the youngest children joined him there, as was the practice at the time. Charles, then 12 years old, was boarded with Elizabeth Roylance, a family friend, in Camden Town. Mrs. Roylance was "a reduced [impoverished] old lady, long known to our family", whom Dickens later immortalised, "with a few alterations and embellishments", as "Mrs. Pipchin", in Dombey and Son. Later, he lived in a back-attic in the house of an agent for the Insolvent Court, Archibald Russell, "a fat, good-natured, kind old gentleman ... with a quiet old wife" and lame son, in Lant Street in The Borough. They provided the inspiration for the Garlands in The Old Curiosity Shop. On Sundays—with his sister Frances, free from her studies at the Royal Academy of Music—he spent the day at the Marshalsea. Dickens would later use the prison as a setting in Little Dorrit. To pay for his board and to help his family, Dickens was forced to leave school and work ten-hour days at Warren's Blacking Warehouse, on Hungerford Stairs, near the present Charing Cross railway station, where he earned six shillings a week pasting labels on pots of boot blacking. The strenuous and often cruel working conditions deeply impressed Dickens and later influenced his fiction and essays, becoming the foundation of his interest in the reform of socio-economic and labour conditions, the rigors of which he believed were unfairly borne by the poor. He would later write that he wondered "how I could have been so easily cast away at such an age" As he recalled to John Forster (from The Life of Charles Dickens): The blacking-warehouse was the last house on the left-hand side of the way, at old Hungerford Stairs. It was a crazy, tumble-down old house, abutting of course on the river, and literally overrun with rats. Its wainscoted rooms, and its rotten floors and staircase, and the old grey rats swarming down in the cellars, and the sound of their squeaking and scuffling coming up the stairs at all times, and the dirt and decay of the place, rise up visibly before me, as if I were there again. The counting-house was on the first floor, looking over the coal-barges and the river. There was a recess in it, in which I was to sit and work. My work was to cover the pots of paste-blacking; first with a piece of oil-paper, and then with a piece of blue paper; to tie them round with a string; and then to clip the paper close and neat, all round, until it looked as smart as a pot of ointment from an apothecary's shop. When a certain number of grosses of pots had attained this pitch of perfection, I was to paste on each a printed label, and then go on again with more pots. Two or three other boys were kept at similar duty down-stairs on similar wages. One of them came up, in a ragged apron and a paper cap, on the first Monday morning, to show me the trick of using the string and tying the knot. His name was Bob Fagin; and I took the liberty of using his name, long afterwards, in Oliver Twist. After only a few months in Marshalsea, John Dickens's paternal grandmother, Elizabeth Dickens, died and bequeathed him the sum of £450. On the expectation of this legacy, Dickens was granted release from prison. Under the Insolvent Debtors Act, Dickens arranged for payment of his creditors, and he and his family left Marshalsea, for the home of Mrs. Roylance. Although Dickens eventually attended the Wellington House Academy in North London, his mother Elizabeth Dickens did not immediately remove him from the boot-blacking factory. The incident may have done much to confirm Dickens's view that a father should rule the family, a mother find her proper sphere inside the home. "I never afterwards forgot, I never shall forget, I never can forget, that my mother was warm for my being sent back". His mother's failure to request his return was no doubt a factor in his dissatisfied attitude towards women. Righteous anger stemming from his own situation and the conditions under which working-class people lived became major themes of his works, and it was this unhappy period in his youth to which he alluded in his favourite, and most autobiographical, novel, David Copperfield: "I had no advice, no counsel, no encouragement, no consolation, no assistance, no support, of any kind, from anyone, that I can call to mind, as I hope to go to heaven!" The Wellington House Academy was not a good school. "Much of the haphazard, desultory teaching, poor discipline punctuated by the headmaster's sadistic brutality, the seedy ushers and general run-down atmosphere, are embodied in Mr. Creakle's Establishment in David Copperfield." Dickens worked at the law office of Ellis and Blackmore, attorneys, of Holborn Court, Gray's Inn, as a junior clerk from May 1827 to November 1828. Then, having learned Gurney's system of shorthand in his spare time, he left to become a freelance reporter. A distant relative, Thomas Charlton, was a freelance reporter at Doctors' Commons, and Dickens was able to share his box there to report the legal proceedings for nearly four years. This education was to inform works such as Nicholas Nickleby, Dombey and Son, and especially Bleak House—whose vivid portrayal of the machinations and bureaucracy of the legal system did much to enlighten the general public and served as a vehicle for dissemination of Dickens's own views regarding, particularly, the heavy burden on the poor who were forced by circumstances to "go to law". In 1830, Dickens met his first love, Maria Beadnell, thought to have been the model for the character Dora in David Copperfield. Maria's parents disapproved of the courtship and effectively ended the relationship by sending her to school in Paris. Journalism and early novels In 1832, at age 20, Dickens was energetic, full of good humour, enjoyed mimicry and popular entertainment, and lacked a clear sense of what he wanted to become, yet knowing he wanted to be famous. He was drawn to the theatre and landed an acting audition a Covent Garden, for which he prepared meticulously but which he missed because of a cold, ending his aspirations for a career on the stage. A year later he submitted his first story, A Dinner at Poplar Walk to the London periodical, Monthly Magazine. He rented rooms at Furnival's Inn becoming a political journalist, reporting on parliamentary debate and travelling across Britain to cover election campaigns for the Morning Chronicle. His journalism, in the form of sketches in periodicals, formed his first collection of pieces Sketches by Boz—Boz being a family nickname he employed as a pseudonym for some years—published in 1836. He continued to contribute to and edit journals throughout his literary career. The success of these sketches led to a proposal from publishers Chapman and Hall for Dickens to supply text to match Robert Seymour's engraved illustrations in a monthly letterpress. Seymour committed suicide after the second instalment and Dickens, who wanted to write a connected series or sketches, hired "Phiz" to provide the engravings (which were reduced from four to two per instalment) to enhance the story. The resulting story was the The Pickwick Papers with the final instalment selling 40,000 copies. In November 1836 Dickens accepted the job of editor of Bentley's Miscellany, a position he held for three years, until he fell out with the owner. In 1836 as he finished the last instalments of The Pickwick Papers he began writing the beginning instalments of Oliver Twist—writing as many as 90 pages a month—while continuing work on Bentley's, writing four plays, the production of which he oversaw. Oliver Twist, published in 1838, became one of Dicken's better known stories, with dialogue that transferred well to the stage (most likely because he was writing stage plays at the same time) and more importantly, it was the first Victorian with a child protagonist. On 2 April 1836, after a one year engagement during which he wrote The Pickwick Papers, he married Catherine Thomson Hogarth (1816–1879), the daughter of George Hogarth, editor of the Evening Chronicle. After a brief honeymoon in Chalk, Kent, they returned to lodgings at Furnival's Inn. The first of ten children, Charley, was born in January 1837, and a few months later the family set up home in Bloomsbury at 48 Doughty Street, London, (on which Charles had a three year lease at £80 a year) from 25 March 1837 until December 1839. Dickens's younger brother Frederick and Catherine's 17-year-old sister Mary moved in with them. Dickens became very attached to Mary, and she died in his arms after a brief illness in 1837. Dickens idealised her and is thought to have drawn on memories of her for his later descriptions of Rose Maylie, Little Nell and Florence Dombey. He grief was so great that he was unable to make the deadline for the June instalment of Pickwick Papers and had to cancel the Oliver Twist instalment that month as well. At the same time, his success as a novelist continued, Nicholas Nickleby (1838–39), The Old Curiosity Shop and, finally, Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty as part of the Master Humphrey's Clock series (1840–41)—all published in monthly instalments before being made into books. First visit to the United States In 1842, Dickens and his wife made his first trip to the United States and Canada. At this time Georgina Hogarth, another sister of Catherine, joined the Dickens household, now living at Devonshire Terrace, Marylebone, to care for the young family they had left behind. She remained with them as housekeeper, organiser, adviser and friend until Dickens's death in 1870. He described his impressions in a travelogue entitled American Notes for General Circulation. Some of the episodes in Martin Chuzzlewit (1843–44) also drew on these first-hand experiences. Dickens includes in Notes a powerful condemnation of slavery, which he had attacked as early as The Pickwick Papers, correlating the emancipation of the poor in England with the abolition of slavery abroad. During his visit, Dickens spent a month in New York City, giving lectures and raising the question of international copyright laws and the pirating of his work in America. He persuaded twenty five writers, headed by Washington Irving to sign a petition for him to take to congress, but the press were generally hostile to this saying that he should be grateful for his popularity and that it was mercenary to complain about his work being pirated. In the early 1840 Dickens showed an interest in Unitarian Christianity, although he never strayed from his attachment to popular lay Anglicanism. Soon after his return to England, Dickens began work on the first of his Christmas stories, A Christmas Carol, written in 1843, which was followed by The Chimes in 1844 and The Cricket on the Hearth in 1845. Of these A Christmas Carol was most popular and, tapping in to an old tradition, did much promote a renewed enthusiasm for the joys of Christmas in Britain and America. The seeds for the story were planted in Dickens's mind during a trip to Manchester to witness conditions of the manufacturing workers there. This, along with scenes he had recently witnessed at the Field Lane Ragged School, caused Dickens to resolve to "strike a sledge hammer blow" for the poor. As the idea for the story took shape and the writing began in earnest, Dickens became engrossed in the book. He wrote that as the tale unfolded he "wept and laughed, and wept again" as he "walked about the black streets of London fifteen or twenty miles many a night when all sober folks had gone to bed." After living briefly abroad in Italy (1844) Dickens travelled to Switzerland (1846); it was here he began work on Dombey and Son (1846–48). This and David Copperfield (1849–50) mark a significant artistic break in Dickens's career as his novels became more serious in theme and more carefully planned than his early works. Philanthropy In May 1846 Angela Burdett Coutts, heir to the Coutts banking fortune, approached Dickens about setting up a home for the redemption of fallen women from the working class. Coutts envisioned a home that would replace the punitive regimes of existing institutions with a reformative environment conducive to education and proficiency in domestic household chores. After initially resisting, Dickens eventually founded the home, named "Urania Cottage", in the Lime Grove section of Shepherds Bush, which he was to manage for ten years, setting the house rules and reviewing the accounts and interviewing prospective residents. Emigration and marriage were central to Dickens' agenda for the women on leaving Urania Cottage, from which it is estimated that about 100 women graduated between 1847 and 1859. Middle years In late November 1851, Dickens moved into Tavistock House where he would write Bleak House (1852), Hard Times (1854) and Little Dorrit (1857). It was here he indulged in the amateur theatricals which are described in Forster's "Life". In 1856, the income he was earning from his writing allowed him to buy Gad's Hill Place in Higham, Kent. As a child, Dickens had walked past the house and dreamed of living in it. The area was also the scene of some of the events of Shakespeare's Henry IV, Part 1 and this literary connection pleased him. In 1857, Dickens hired professional actresses for the play The Frozen Deep, which he and his protégé Wilkie Collins had written. Dickens fell deeply in love with one of the actresses, Ellen Ternan, which was to last the rest of his life. Dickens was 45 and Ternan 18 when he made the decision, which went strongly against Victorian convention, to separate from his wife, Catherine, in 1858—divorce was still unthinkable for someone as famous as he was. When Catherine left, never to see her husband again, she took with her one child, leaving the other children to be raised by her sister Georgina who chose to stay at Gad's Hill. During this period, whilst pondering about giving public readings for his own profit, Dickens was approached by Great Ormond Street Hospital to help it survive its first major financial crisis through a charitable appeal. His 'Drooping Buds’ essay in Household Words earlier in 3 April 1852 was considered by the hospital’s founders to have been the catalyst for the hospital’s success. Dickens, whose philanthropy was well-known, was asked by his friend, the hospital's founder Charles West, to preside and he threw himself into the task, heart and soul. Dickens' public readings secured sufficient funds for an endowment to put the hospital on a sound financial footing — one of February 9, 1858 alone raised £3,000. After separating from Catherine, Dickens undertook a series of hugely popular and remunerative reading tours which, together with his journalism, were to absorb most of his creative energies for the next decade, in which he was to write only two more novels. His first reading tour, lasting from April 1858 to February 1859, consisted of 129 appearances in 49 different towns throughout England, Scotland and Ireland.[63] Dickens' continued fascination with the theatrical world was written into the theatre scenes in Nicholas Nickleby, but more importantly he found an outlet in public readings. In 1866, he undertook a series of public readings in England and Scotland, with more the following year in England and Ireland. Major works, A Tale of Two Cities (1859); and Great Expectations (1861) soon followed and would prove resounding successes. During this time he was also the publisher and editor of, and a major contributor to, the journals Household Words (1850–1859) and All the Year Round (1858–1870). In early September 1860, in a field behind Gad's Hill, Dickens made a great bonfire of almost his entire correspondence—only those letters on business matters were spared. Since Ellen Ternan also destroyed all of his letters to her, the extent of the affair between the two remains speculative. In the 1930s, Thomas Wright recounted that Ternan had unburdened herself with a Canon Benham, and gave currency to rumours they had been lovers. That the two had a son who died in infancy was alleged by Dickens' daughter, Kate Perugini, whom Gladys Storey had interviewed before her death in 1929, and published her account in Dickens and Daughter, although no contemporary evidence exists. On his death, Dickens settled an annuity on Ternan which made her a financially independent woman. Claire Tomalin's book, The Invisible Woman, argues that Ternan lived with Dickens secretly for the last 13 years of his life. The book was subsequently turned into a play, Little Nell, by Simon Gray. In the same period, Dickens furthered his interest in the paranormal, becoming one of the early members of The Ghost Club. Last years On 9 June 1865, while returning from Paris with Ternan, Dickens was involved in the Staplehurst rail crash. The first seven carriages of the train plunged off a cast iron bridge under repair. The only first-class carriage to remain on the track was the one in which Dickens was travelling. Before rescuers arrived, Dickens tended and comforted the wounded and the dying with a flask of brandy and a hat refreshed with water and saved some lives. Before leaving, he remembered the unfinished manuscript for Our Mutual Friend, and he returned to his carriage to retrieve it. Dickens later used this experience as material for his short ghost story, "The Signal-Man", in which the central character has a premonition of his own death in a rail crash. He also based the story on several previous rail accidents, such as the Clayton Tunnel rail crash of 1861. Dickens managed to avoid an appearance at the inquest to avoid disclosing that he had been travelling with Ternan and her mother, which would have caused a scandal. Although physically unharmed, Dickens never really recovered from the trauma of the Staplehurst crash, and his normally prolific writing shrank to completing Our Mutual Friend and starting the unfinished The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Second visit to the United States On 9 November 1867, Dickens sailed from Liverpool for his second American reading tour. Landing at Boston, he devoted the rest of the month to a round of dinners with such notables as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and his American publisher James Thomas Fields. In early December, the readings began—he was to 76 readings, netting £19,000, from December 1867 to April 1868 and Dickens spent the month shuttling between Boston and New York, where alone he gave 22 readings at Steinway Hall for this period. Although he had started to suffer from what he called the "true American catarrh", he kept to a schedule that would have challenged a much younger man, even managing to squeeze in some sleighing in Central Park. . During his travels, he saw a significant change in the people and the circumstances of America. His final appearance was at a banquet the American Press held in his honour at Delmonico's on 18 April, when he promised never to denounce America again. By the end of the tour, the author could hardly manage solid food, subsisting on champagne and eggs beaten in sherry. On 23 April, he boarded his ship to return to Britain, barely escaping a Federal Tax Lien against the proceeds of his lecture tour. Farewell readings Between 1868 and 1869, Dickens gave a series of "farewell readings" in England, Scotland, and Ireland, beginning on the 6th October. He managed, of a contracted 100 readings, to deliver 75 in the provinces, with a further 12 in London. As he pressed on he was affected by giddiness and fits of paralysis and collapsed on 22 April 1869, at Preston in Lancashire, and on doctor's advice, the tour was cancelled. After further provincial readings were cancelled, he began work on his final novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood. It was fashionable in the 1860s to 'do the slums' and, in company, Dickens visited opium dens in Shadwell, where he witnessed an elderly addict known as "Laskar Sal", who formed the model for the "Opium Sal" subsequently featured in his mystery novel, Edwin Drood. When he had regained sufficient strength, Dickens arranged, with medical approval, for a final series of readings at least partially to make up to his sponsors what they had lost due to his illness. There were to be 12 performances, running between 11 January and 15 March 1870, the last taking place at 8:00 pm at St. James's Hall in London. Although in grave health by this time, he read A Christmas Carol and The Trial from Pickwick. On 2 May, he made his last public appearance at a Royal Academy Banquet in the presence of the Prince and Princess of Wales, paying a special tribute to the passing of his friend, illustrator Daniel Maclise. Death On 8 June 1870, Dickens suffered another stroke at his home, after a full day's work on Edwin Drood. He never regained consciousness, and the next day, on 9 June, five years to the day after the Staplehurst rail crash (9 June 1865), he died at Gad's Hill Place. Contrary to his wish to be buried at Rochester Cathedral "in an inexpensive, unostentatious, and strictly private manner," he was laid to rest in the Poets' Corner of Westminster Abbey. A printed epitaph circulated at the time of the funeral reads: "To the Memory of Charles Dickens (England's most popular author) who died at his residence, Higham, near Rochester, Kent, 9 June 1870, aged 58 years. He was a sympathiser with the poor, the suffering, and the oppressed; and by his death, one of England's greatest writers is lost to the world." His last words were: "On the ground", in response to his daughter Georgina's request that he lie down. On Sunday, 19 June 1870, five days after Dickens was buried in the Abbey, Dean Arthur Penrhyn Stanley delivered a memorial elegy, lauding "the genial and loving humorist whom we now mourn", for showing by his own example "that even in dealing with the darkest scenes and the most degraded characters, genius could still be clean, and mirth could be innocent." Pointing to the fresh flowers that adorned the novelist's grave, Stanley assured those present that "the spot would thenceforth be a sacred one with both the New World and the Old, as that of the representative of literature, not of this island only, but of all who speak our English tongue." Literary style Dickens loved the style of the 18th century picaresque novels which he found in abundance on his father's shelves. According to Ackroyd, other than these, perhaps the most important literary influence on him was derived from the fables of The Arabian Nights. His writing style is marked by a profuse linguistic creativity. Satire, flourishing in his gift for caricature is his forte. An early reviewer compared him to Hogarth for his keen practical sense of the ludicrous side of life, though his acclaimed mastery of varieties of class idiom may in fact mirror the conventions of contemporary popular theatre. Dickens worked intensively on developing arresting names for his characters that would reverberate with associations for his readers, and assist the development of motifs in the storyline, giving what one critic calls an "allegorical impetus" to the novels' meanings. To cite one of numerous examples, the name Mr. Murdstone in David Copperfield conjures up twin allusions to "murder" and stony coldness. His literary style is also a mixture of fantasy and realism. His satires of British aristocratic snobbery—he calls one character the "Noble Refrigerator"—are often popular. Comparing orphans to stocks and shares, people to tug boats, or dinner-party guests to furniture are just some of Dickens's acclaimed flights of fancy. The author worked closely with his illustrators, supplying them with a summary of the work at the outset and thus ensuring that his characters and settings were exactly how he envisioned them. He would brief the illustrator on plans for each month's instalment so that work could begin before he wrote them. Marcus Stone, illustrator of Our Mutual Friend, recalled that the author was always "ready to describe down to the minutest details the personal characteristics, and ... life-history of the creations of his fancy." Characters Dickens's biographer Claire Tomalin regards him as the greatest creator of character in English fiction after Shakespeare. Dickensian characters, especially so because of their typically whimsical names, are amongst the most memorable in English literature. The likes of Ebenezer Scrooge, Tiny Tim, Jacob Marley, Bob Cratchit, Oliver Twist, The Artful Dodger, Fagin, Bill Sikes, Pip, Miss Havisham, Charles Darnay, David Copperfield, Mr. Micawber, Abel Magwitch, Daniel Quilp, Samuel Pickwick, Wackford Squeers, Uriah Heep are so well known as to be part and parcel of British culture, and in some cases have passed into ordinary language: a scrooge, for example, is a miser. His characters were often so memorable that they took on a life of their own outside his books. Gamp became a slang expression for an umbrella from the character Mrs. Gamp and Pickwickian, Pecksniffian, and Gradgrind all entered dictionaries due to Dickens's original portraits of such characters who were quixotic, hypocritical, or vapidly factual. Many were drawn from real life: Mrs Nickleby is based on his mother, though she didn't recognize herself in the portrait, just as Mr Micawber is constructed from aspects of his father's 'rhetorical exuberance': Harold Skimpole in Bleak House, is based on James Henry Leigh Hunt: his wife's dwarfish chiropodist recognized herself in Miss Mowcher in David Copperfield. Perhaps Dickens' impressions on his meeting with Hans Christian Andersen informed the delineation of Uriah Heep. Virginia Woolf maintained that "we remodel our psychological geography when we read Dickens" as he produces "characters who exist not in detail, not accurately or exactly, but abundantly in a cluster of wild yet extraordinarily revealing remarks." One "character" vividly drawn throughout his novels is London itself. From the coaching inns on the outskirts of the city to the lower reaches of the Thames, all aspects of the capital are described over the course of his body of work. Autobiographical elements Authors frequently draw their portraits of characters from people they've known in real life. David Copperfield is regarded as strongly autobiographical. The scenes in Bleak House of interminable court cases and legal arguments reflect Dickens's experiences as law clerk and court reporter, and in particular his direct experience of the law's procedural delay during 1844 when he sued publishers in Chancery for breach of copyright. Dickens's own father was sent to prison for debt, and this became a common theme in many of his books, with the detailed depiction of life in the Marshalsea prison in Little Dorrit resulting from Dickens's own experiences of the institution. Lucy Stroughill, a childhood sweetheart may have affected several of Dickens' portraits of girls such as Little Em'ly in David Copperfield and Lucie Manette in A Tale of Two Cities. Dickens may have drawn on his childhood experiences, but he was also ashamed of them and would not reveal that this was where he gathered his realistic accounts of squalor. Very few knew the details of his early life until six years after his death when John Forster published a biography on which Dickens had collaborated. Even figures based on real people can, at the same time, represent at the same time elements of the writer's own personality. Though Skimpole brutally sends up Leigh Hunt, some critics have detected in his portrait features of Dickens' own character, which he sought to exorcise by self-parody. Episodic writing Most of Dickens's major novels were first written in monthly or weekly instalments in journals such as Master Humphrey's Clock and Household Words, later reprinted in book form. These instalments made the stories cheap, accessible and the series of regular cliff-hangers made each new episode widely anticipated. When The Old Curiosity Shop was being serialized, American fans even waited at the docks in New York, shouting out to the crew of an incoming ship, "Is little Nell dead?" Part of Dickens's great talent was to incorporate this episodic writing style but still end up with a coherent novel at the end. Another important impact of Dickens's episodic writing style resulted from his exposure to the opinions of his readers and friends. His friend Forster had a significant hand, reviewing his drafts, that went beyond matters of punctation. He toned down melodramatic and sensationalist exaggerations, cut long passages, (such as the episode of Quilp's drowning in The Old Curiosity Shop), and made suggestions about plot and character. It was he who suggested that Charley Bates should be redeemed in Oliver Twist. Dickens had not thought of killing Little Nell, and it was Forster who advised him to entertain this possibility as necessary to his conception of the heroine. Social commentary Dickens's novels were, among other things, works of social commentary. He was a fierce critic of the poverty and social stratification of Victorian society. In a New York address, he expressed his belief that, "Virtue shows quite as well in rags and patches as she does in purple and fine linen" Dickens's second novel, Oliver Twist (1839), shocked readers with its images of poverty and crime: it destroyed middle class polemics about criminals, making any pretence to ignorance about what poverty entailed impossible spurred the clearing of the actual London slum, Jacob's Island, that was the basis of the story. In addition, with the character of the tragic prostitute, Nancy, Dickens "humanised" such women for the reading public; women who were regarded as "unfortunates", inherently immoral casualties of the Victorian class/economic system. Bleak House and Little Dorrit elaborated expansive critiques of the Victorian institutional apparatus: the interminable lawsuits of the Court of Chancery that destroyed people's lives in Bleak House and a dual attack in Little Dorrit on inefficient, corrupt patent offices and unregulated market speculation. Literary techniques Dickens is often described as using 'idealised' characters and highly sentimental scenes to contrast with his caricatures and the ugly social truths he reveals. The story of Nell Trent in The Old Curiosity Shop (1841) was received as extraordinarily moving by contemporary readers but viewed as ludicrously sentimental by Oscar Wilde. "You would need to have a heart of stone", he declared in one of his famous witticisms, "not to laugh at the death of little Nell."[104] G. K. Chesterton, stating that "It is not the death of little Nell, but the life of little Nell, that I object to", argued that the maudlin effect of his description of her life owed much to the gregarious nature of Dickens' grief, his 'despotic' use of pedople's feelings to move them to tears in works like this. In Oliver Twist Dickens provides readers with an idealised portrait of a boy so inherently and unrealistically 'good' that his values are never subverted by either brutal orphanages or coerced involvement in a gang of young pickpockets. While later novels also centre on idealised characters (Esther Summerson in Bleak House and Amy Dorrit in Little Dorrit), this idealism serves only to highlight Dickens's goal of poignant social commentary. Many of his novels are concerned with social realism, focusing on mechanisms of social control that direct people's lives (for instance, factory networks in Hard Times and hypocritical exclusionary class codes in Our Mutual Friend).[citation needed] Dickens' fiction, reflecting what he believed to be true of his own life, scintillates with coincidences. Oliver Twist turns out to be the lost nephew of the upper class family that randomly rescues him from the dangers of the pickpocket group). Such coincidences are a staple of 18th-century picaresque novels, such as Henry Fielding's Tom Jones that Dickens enjoyed reading as a youth. Reception Dickens was the most popular novelist of his time, and remains one of the best known and most read of English authors. His works have never gone out of print and have been adapted continuously for the screen since the invention of cinema, with at least 200 motion pictures and TV adaptations based on Dickens's works documented. Many of his works were adapted for the stage during his own lifetime and as early as 1913, a silent film of The Pickwick Papers was made. Among fellow writers, Dickens has been both lionized and mocked. Leo Tolstoy, G.K, Chesterton and George Orwell praised his realism, comic voice, prose fluency, and genius for satiric caricature, as well as his passionate advocacy on behalf of children and the poor. On the other hand, Oscar Wilde generally disparaged his depiction of character, whiloe admiring his gift for caricature; Henry James denied him a premier position, calling him, "the greatest of superficial novelists": Dickens failed to endow his characters with psychological depth and the novels, "loose baggy monsters" betrayed a "cavalier organisation"; Virginia Woolf had a love-hate relationship with his works, finding his novels "mesmerizing" while reproving him for his sentimentalism and a commonplace style. It is likely that A Christmas Carol stands as his best-known story, with frequent new adaptations. It is also the most-filmed of Dickens's stories, with many versions dating from the early years of cinema. According to the historian Ronald Hutton, the current state of the observance of Christmas is largely the result of a mid-Victorian revival of the holiday spearheaded by A Christmas Carol. Dickens catalysed the emerging Christmas as a family-centred festival of generosity, in contrast to the dwindling community-based and church-centred observations, as new middle-class expectations arose. Its archetypal figures (Scrooge, Tiny Tim, the Christmas ghosts) entered into Western cultural consciousness. A prominent phrase from the tale, 'Merry Christmas', was popularised following the appearance of the story. The term Scrooge became a synonym for miser, and his dismissive put-down exclamation 'Bah! Humbug!' likewise gained currency as an idiom. Novelist William Makepeace Thackeray called the book "a national benefit, and to every man and woman who reads it a personal kindness". At a time when Britain was the major economic and political power of the world, Dickens highlighted the life of the forgotten poor and disadvantaged within society. Through his journalism he campaigned on specific issues—such as sanitation and the workhouse—but his fiction probably demonstrated its greatest prowess in changing public opinion in regard to class inequalities. He often depicted the exploitation and oppression of the poor and condemned the public officials and institutions that not only allowed such abuses to exist, but flourished as a result. His most strident indictment of this condition is in Hard Times (1854), Dickens's only novel-length treatment of the industrial working class. In this work, he uses both vitriol and satire to illustrate how this marginalised social stratum was termed "Hands" by the factory owners; that is, not really "people" but rather only appendages of the machines that they operated. His writings inspired others, in particular journalists and political figures, to address such problems of class oppression. For example, the prison scenes in The Pickwick Papers are claimed to have been influential in having the Fleet Prison shut down. Karl Marx asserted that Dickens" ... issued to the world more political and social truths than have been uttered by all the professional politicians, publicists and moralists put together" George Bernard Shaw even remarked that Great Expectations was more seditious than Marx's own Das Kapital. The exceptional popularity of his novels, even those with socially oppositional themes (Bleak House, 1853; Little Dorrit, 1857; Our Mutual Friend, 1865) underscored not only his almost preternatural ability to create compelling storylines and unforgettable characters, but also ensured that the Victorian public confronted issues of social justice that had commonly been ignored. It has been argued that his technique of flooding his narratives with an 'unruly superfluity of material' that, in the gradual dénouement, yields up an unsuspected order, influenced the organisation of Charles Darwin's The Origin of the Species. His fiction, with often vivid descriptions of life in 19th-century England, has inaccurately and anachronistically come to symbolise on a global level Victorian society (1837 – 1901) as uniformly "Dickensian", when in fact, his novels' time scope spanned from the 1770s to the 1860s. In the decade following his death in 1870, a more intense degree of socially and philosophically pessimistic perspectives invested British fiction; such themes stood in marked contrast to the religious faith that ultimately held together even the bleakest of Dickens's novels. Dickens clearly influenced later Victorian novelists such as Thomas Hardy and George Gissing; their works display a greater willingness to confront and challenge the Victorian institution of religion. They also portray characters caught up by social forces (primarily via lower-class conditions), but they usually steered them to tragic ends beyond their control. Influence and legacy Museums and festivals celebrating Dickens's life and works exist in many places with which Dickens was associated, such as the Charles Dickens Birthplace Museum in Portsmouth, the house in which he was born. The original manuscripts of many of his novels, as well as printers' proofs, first editions, and illustrations from the collection of Dickens' friend John Forster are held at the Victoria and Albert Museum. Dickens's will stipulated that no memorial be erected in his honour. The only life-size bronze statue of Dickens, cast in 1891 by Francis Edwin Elwell, can be found in Clark Park in the Spruce Hill neighbourhood of Philadelphia. Dickens was commemorated on the Series E £10 note issued by the Bank of England that was in circulation in the UK between 1992 and 2003. His portrait appeared on the reverse of the note accompanied by a scene from The Pickwick Papers. A theme park, Dickens World, standing in part on the site of the former naval dockyard where Dickens's father once worked in the Navy Pay Office, opened in Chatham in 2007, and to celebrate the 200th anniversary of the birth of Charles Dickens in 2012, the Museum of London will the UK's first major exhibition on the author in 40 years. In the UK survey entitled The Big Read carried out by the BBC in 2003, five of Dickens's books were named in the Top 100. Notable works * Charles Dickens published over a dozen major novels, a large number of short stories (including a number of Christmas-themed stories), a handful of plays, and several non-fiction books. Dickens's novels were initially serialised in weekly and monthly magazines, then reprinted in standard book formats. Novels * The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club (Monthly serial, April 1836 to November 1837)[125] * The Adventures of Oliver Twist (Monthly serial in Bentley's Miscellany, February 1837 to April 1839) * The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby (Monthly serial, April 1838 to October 1839) * The Old Curiosity Shop (Weekly serial in Master Humphrey's Clock, 25 April 1840, to 6 February 1841) * Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty (Weekly serial in Master Humphrey's Clock, 13 February 1841, to 27 November 1841) The Christmas books: * A Christmas Carol (1843) * The Chimes (1844) * The Cricket on the Hearth (1845) * The Battle of Life (1846) * The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain (1848) * The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit (Monthly serial, January 1843 to July 1844) * Dombey and Son (Monthly serial, October 1846 to April 1848) * David Copperfield (Monthly serial, May 1849 to November 1850) * Bleak House (Monthly serial, March 1852 to September 1853) * Hard Times: For These Times (Weekly serial in Household Words, 1 April 1854, to 12 August 1854) * Little Dorrit (Monthly serial, December 1855 to June 1857) * A Tale of Two Cities (Weekly serial in All the Year Round, 30 April 1859, to 26 November 1859) * Great Expectations (Weekly serial in All the Year Round, 1 December 1860 to 3 August 1861) * Our Mutual Friend (Monthly serial, May 1864 to November 1865) * The Mystery of Edwin Drood (Monthly serial, April 1870 to September 1870. Only six of twelve planned numbers completed) Short story collections * Sketches by Boz (1836) * The Mudfog Papers (1837) in Bentley's Miscellany magazine * Reprinted Pieces (1861) * The Uncommercial Traveller (1860–1869) * Christmas numbers of Household Words magazine: * What Christmas Is, as We Grow Older (1851) * A Round of Stories by the Christmas Fire (1852) * Another Round of Stories by the Christmas Fire (1853) *The Seven Poor Travellers (1854) * The Holly-Tree Inn (1855) * The Wreck of the "Golden Mary" (1856) * The Perils of Certain English Prisoners (1857) * A House to Let (1858) * Christmas numbers of All the Year Round magazine: * The Haunted House (1859) * A Message from the Sea (1860) * Tom Tiddler's Ground (1861) * Somebody's Luggage (1862) * Mrs. Lirriper's Lodgings (1863) * Mrs. Lirriper's Legacy (1864) * Doctor Marigold's Prescriptions (1865) * Mugby Junction (1866) * No Thoroughfare (1867) Selected non-fiction, poetry, and plays * The Village Coquettes (Plays, 1836) * The Fine Old English Gentleman (poetry, 1841) * Memoirs of Joseph Grimaldi (1838) * American Notes: For General Circulation (1842) * Pictures from Italy (1846) * The Life of Our Lord: As written for his children (1849) * A Child's History of England (1853) * The Frozen Deep (play, 1857) * Speeches, Letters and Sayings (1870) References Wikipedia - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Dickens

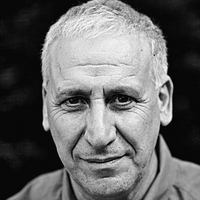

Edward Hirsch (born January 20, 1950) is an American poet and critic who wrote a national bestseller about reading poetry. He has published nine books of poems, including The Living Fire: New and Selected Poems (2010), which brings together thirty-five years of work, and Gabriel: A Poem (2014), a book-length elegy for his son that The New Yorker calls “a masterpiece of sorrow.” He has also published five prose books about poetry. He is president of the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation in New York City (not to be mistaken with E.D. Hirsch, Jr.). Life Hirsch was born in Chicago. He had a childhood involvement with poetry, which he later explored at Grinnell College and the University of Pennsylvania, where he received a Ph.D. in folklore. Hirsch was a professor of English at Wayne State University. In 1985, he joined the faculty at the University of Houston, where he spent 17 years as a professor in the Creative Writing Program and Department of English. He was appointed the fourth president of the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation on September 3, 2002. He holds seven honorary degrees. Career Hirsch is a well-known advocate for poetry whose essays have been published in the American Poetry Review, The New York Times Book Review, The New York Review of Books, and elsewhere. He wrote a weekly column on poetry for The Washington Post Book World from 2002-2005, which resulted in his book Poet’s Choice (2006). His other prose books include Responsive Reading (1999), The Demon and the Angel: Searching for the Source of Artistic Inspiration (2002), and A Poet’s Glossary (2014), a complete compendium of poetic terms. He is the editor of Transforming Vision: Writers on Art (1994), Theodore Roethke’s Selected Poems (2005) and To a Nightingale (2007). He is the co-editor of A William Maxwell Portrait: Memories and Appreciations and The Making of a Sonnet: A Norton Anthology (2008). He also edits the series “The Writer’s World” (Trinity University Press). Hirsch’s first collection of poems, For the Sleepwalkers, received the Lavan Younger Poets Award from the Academy of American Poets and the Delmore Schwartz Memorial Award from New York University. His second book, Wild Gratitude, received the National Book Critics Circle Award in 1986. He was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1985 and a five-year MacArthur Fellowship in 1997. He received the William Riley Parker Prize from the Modern Language Association for the best scholarly essay in PMLA for the year 1991. He has also received an Ingram Merrill Foundation Award, a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, the Rome Prize from the American Academy in Rome, a Pablo Neruda Presidential Medal of Honor, and the American Academy of Arts and Letters Award for Literature. He is a former Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets. Hirsch’s book, How to Read a Poem and Fall in Love with Poetry (1999), was a surprise bestseller and is widely taught throughout the country. Works Poetry collections * For the Sleepwalkers, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1981) * Wild Gratitude, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1986) * The Night Parade, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1989) * Earthly Measures, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1994) ISBN 0-679-76566-2 * On Love, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1998) * Lay Back the Darkness (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2003) ISBN 0-375-41521-1 * Special Orders (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2008) ISBN 0-307-26681-8 * Gabriel A Poem (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2014) ISBN 978-0-385-35357-1 Non-fiction books * Transforming Vision: Writers on Art, Selected and Introduced by Edward Hirsch, (Boston: Little, Brown, 1994) ISBN 0-8212-2126-4 * How to Read a Poem and Fall in Love with Poetry, (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1999) ISBN 0-15-100419-6 * Responsive Reading, (1999) * 'Introduction’ in John Keats, Complete Poems and Selected Letters of John Keats, (New York: Modern Library, 2001) ISBN 0-375-75669-8 * The Demon and the Angel: Searching for the Source of Artistic Expression, (New York: Harcourt Brace, 2002) * Poet’s Choice, (New York: Harcourt, 2006) ISBN 0-15-101356-X * A Poet’s Glossary, (Boston & New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014) ISBN 978-0-15-101195-7 Editor * Transforming Vision: Writers on Art, (The Art Institute of Chicago/ Bulfinch Press, 1994) ISBN 978-0821221266 * A William Maxwell Portrait, (Norton, 2004) ISBN 978-0393057713 * Theodore Roethke: Selected Poems, (The Library of America, 2005) ISBN 978-1931082785 * Irish Writers on Writing, edited with Eavan Boland, (Trinity University Press, 2007) ISBN 9781595340320 * Polish Writers on Writing, edited with Adam Zagajewski, (Trinity University Press, 2007) ISBN 9781595340337 * To a Nightingale: Poems from Sappho to Borges, (Braziller, 2007) ISBN 978-0807616277 * The Making of a Sonnet, (Norton, 2008) ISBN 978-0393333534 * Hebrew Writers on Writing, edited with Peter Cole (Trinity University Press, 2008) ISBN 9781595340528 * Nineteenth-Century American Writers on Writing, edited with Brenda Wineapple (Trinity University Press, 2010) ISBN 9781595340696 * Chinese Writers on Writing, edited with Arthur Sze (Trinity University Press, 2010) ISBN 9781595340634 * Romanian Writers on Writing, edited with Norman Manea, (Trinity University Press, 2011) ISBN 9781595340825 References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Hirsch

George Gascoigne (c. 1535– 7 October 1577) was an English poet, soldier and unsuccessful courtier. He is considered the most important poet of the early Elizabethan era, following Sir Thomas Wyatt and Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey and leading to the emergence of Philip Sidney. He was the first poet to deify Queen Elizabeth I, in effect establishing her cult as a virgin goddess married to her kingdom and subjects. His most noted works include A Discourse of the Adventures of Master FJ (1573), an account of courtly sexual intrigue and one of the earliest English prose fictions; The Supposes, (performed in 1566, printed in 1573), an early translation of Ariosto and the first comedy written in English prose, which was used by Shakespeare as a source for The Taming of the Shrew; the frequently anthologised short poem “Gascoignes wodmanship” (1573); and “Certayne Notes of Instruction concerning the making of verse or ryme in English” (1575), the first essay on English versification. Early life The eldest son of Sir John Gascoigne of Cardington, Bedfordshire, Gascoigne was educated at Trinity College, Cambridge, and on leaving the university is supposed to have joined the Middle Temple. He became a member of Gray’s Inn in 1555. He has been identified without much show of evidence with a lawyer named Gastone who was in prison in 1548 under very discreditable circumstances. There is no doubt that his escapades were notorious, and that he was imprisoned for debt. George Whetstone says that Sir John Gascoigne disinherited his son on account of his follies, but by his own account he was obliged to sell his patrimony to pay the debts contracted at court. He was M.P. for Bedford in 1557–1558 and 1558–1559, but when he presented himself in 1572 for election at Midhurst he was refused on the charges of being “a defamed person and noted for manslaughter”, “a common Rymer and a deviser of slaunderous Pasquelles”, “a notorious rufilanne”, and a constantly indebted atheist. His poems, with the exception of some commendatory verses, were not published before 1572, but they may have circulated in manuscript before that date. He tells us that his friends at Gray’s Inn importuned him to write on Latin themes set by them, and that two of his plays were acted there. He repaired his fortunes by marrying the wealthy widow of William Breton, thus becoming stepfather to the poet, Nicholas Breton. In 1568 an inquiry into the disposition of William Breton’s property with a view to the protection of the children’s rights was instituted before the Lord Mayor, but the matter was probably settled in a friendly manner, for Gascoigne continued to hold the Breton Walthamstow estate, which he had from his wife, until his death. Plays at Grays Inn Gascoigne translated two plays performed in 1566 at Grays Inn, the most aristocratic of the Renaissance London Inns of Court: the prose comedy Supposes based on Ariosto’s Suppositi, and Jocasta, a tragedy in blank verse which is said to have derived from Euripides’s Phoenissae, but appears more directly as a translation from the Italian of Lodovico Dolce’s Giocasta. Hundredth Sundry Flowres (1573) and Posies of Gascoigne (1575) Gascoigne’s best known and controversial work was originally published in 1573 under the title A Hundredth Sundry Flowres bound up in one small Posie. Gathered partly (by translation) in the fyne outlandish Gardens of Euripides, Ovid, Petrarch, Ariosto and others; and partly by Invention out of our owne fruitfull Orchardes in Englande, Yelding Sundrie Savours of tragical, comical and moral discourse, bothe pleasaunt and profitable, to the well-smelling noses of learned readers, by London printer Richarde Smith. The book purports to be an anthology of courtly poets, gathered and edited by Gascoigne and two other editors known only by the initials “H.W.” and “G.T.” The book’s content is throughout suggestive of courtly scandal, and the aura of scandal is skillfully elaborated through the effective use of initials and posies—Latin or English tags supposed to denote particular authors—in place of the real names of actual or alleged authors. For reasons that are still unclear, the book was republished, with certain additions and deletions, two years later under the alternative title, The Posies of George Gascoigne, Esquire. The new edition contains three new dedicatory epistles, signed by Gascoigne, which apologize for some offense that the original edition had caused and effect to transfer sole responsibility for the book’s content to Gascoigne himself. At war in the Netherlands When Gascoigne sailed as a soldier of fortune to the Low Countries in 1572, his ship was driven by stress of weather to Brielle, which luckily for him had just fallen into the hands of the Dutch. He obtained a captain’s commission, and took an active part in the campaigns of the next two years including the Middelburg siege, during which he acquired a profound dislike of the Dutch, and a great admiration for William of Orange, who had personally intervened on his behalf in a quarrel with his colonel, and secured him against the suspicion caused by his clandestine visits to a lady at the Hague. Taken prisoner after the evacuation of Valkenburg by English troops during the Siege of Leiden, he was sent to England in the autumn of 1574. He dedicated to Lord Grey de Wilton the story of his adventures, The Fruites of Warres (printed in the edition of 1575) and Gascoigne’s Voyage into Hollande. In 1575 he had a share in devising the masques, published in the next year as The Princely Pleasures at the Courte at Kenelworth, which celebrated the queen’s visit to the Earl of Leicester. At Woodstock in 1575 he delivered a prose speech before Elizabeth, and was present at a reading of the Pleasant Tale of Hemetes the Hermit, a brief romance, probably written by the queen’s host, Sir Henry Lee. At the queen’s annual gift exchange with members of her court the following New Year’s, Gascoigne gave her a manuscript of Hemetes which he had translated into Latin, Italian, and French. Its frontispiece shows the Queen rewarding the kneeling poet with an accolade and a purse; its motto, “Tam Marti, quam Mercurio,” indicates that he will serve her as a soldier, as a scholar-poet, or as both. He also drew three emblems, with accompanying text in the three other languages. He also translated Jacques du Fouilloux’s La Venerie (1561) into English as The Noble Arte of Venerie or Hunting (1575) which was printed together with George Turberville’s The Book of Falconrie or Hawking and is thus sometimes misattributed to Turberville though in fact it was a work by Gascoigne. Later writings and influences Most of his works were published during the last years of his life after his return from the wars. He died 7 October 1577 at Walcot Hall, Barnack, near Stamford, where he was the guest of George Whetstone and was buried in the Whetstone family vault at St John the Baptist’s Church, Barnack. Gascoigne’s theory of metrical composition is explained in a short critical treatise, “Certayne Notes of Instruction concerning the making of verse or ryme in English, written at the request of Master Edouardo Donati,” prefixed to his Posies (1575). He acknowledged Chaucer as his master, and differed from the earlier poets of the school of Surrey and Wyatt chiefly in the greater smoothness and sweetness of his verse. Ancestry References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Gascoigne

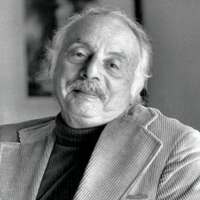

Karl Jay Shapiro (November 10, 1913– May 14, 2000) was an American poet. He was appointed the fifth Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress in 1946. Biography Karl Shapiro was born in Baltimore, Maryland and graduated from the Baltimore City College high school. He attended the University of Virginia before World War II, and immortalized it in a scathing poem called “University,” which noted that “to hate the Negro and avoid the Jew is the curriculum.” He did not return after his military service. Karl Shapiro, a stylish writer with a commendable regard for his craft, wrote poetry in the Pacific Theater while he served there during World War II. His collection V-Letter and Other Poems, written while Shapiro was stationed in New Guinea, was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1945, while Shapiro was still in the military. Shapiro was American Poet Laureate in 1946 and 1947. (At the time this title was Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress which was changed by Congress in 1985 to Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress.) Poems from his earlier books display a mastery of formal verse with a modern sensibility that viewed such topics as automobiles, house flies, and drug stores as worthy of attention. In 1963, the poet/critic Randall Jarrell praised Shapiro’s work: Karl Shapiro’s poems are fresh and young and rash and live; their hard clear outlines, their flat bold colors create a world like that of a knowing and skillful neoprimitive painting, without any of the confusion or profundity of atmosphere, of aerial perspective, but with notable visual and satiric force. The poet early perfected a style, derived from Auden but decidedly individual, which he has not developed in later life but has temporarily replaced with the clear Rilke-like rhetoric of his Adam and Eve poems, the frankly Whitmanesque convolutions of his latest work. His best poem—poems like “The Leg,” “Waitress,” “Scyros,” “Going to School,” “Cadillac”—have a real precision, a memorable exactness of realization, yet they plainly come out of life’s raw hubbub, out of the disgraceful foundations, the exciting and disgraceful surfaces of existence. In his later work, he experimented with more open forms, beginning with The Bourgeois Poet (1964) and continuing with White-Haired Lover (1968). The influences of Walt Whitman, D. H. Lawrence, W. H. Auden and William Carlos Williams were evident in his work. Shapiro’s interest in formal verse and prosody led to his writing multiple books on the subject including the long poem Essay on Rime (1945), A Bibliography of Modern Prosody (1948), and A Prosody Handbook (with Robert Beum, 1965; reissued 2006). His Selected Poems appeared in 1968. Shapiro also published one novel, Edsel (1971) and a three-part autobiography simply titled, “Poet” (1988–1990). Shapiro edited the prestigious magazine, Poetry for several years, and he was a professor of English at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, where he edited Prairie Schooner, and at the University of California, Davis, from which he retired in the mid-1980s. His other works include Person, Place and Thing (1942), (with Ernst Lert) the libretto to Hugo Weisgall’s opera The Tenor (1950), To Abolish Children (1968), and The Old Horsefly (1993). Shapiro received the 1969 Bollingen Prize for Poetry, sharing the award that year with John Berryman. He died in New York City, aged 86, on May 14, 2000. More recent editions of his work include The Wild Card: Selected Poems Early and Late (1998) and Selected Poems (2003). Shapiro’s last work, Coda: Last Poems, (2008) was recently published in a volume organized posthumously by editor Robert Phillips. The poems, divided into three sections according to love poems to his last wife, poems concerning roses, and other various poems, were discovered in the drawers of Shapiro’s desk by his wife two years after his death. Awards * Jeanette S Davis Prize and Levinson prize, both from Poetry in 1942 * Contemporary Poetry prize, 1943 * American Academy of Arts and Letters grant, 1944 * Guggenheim Foundation fellowships, 1944, 1953 * Pulitzer Prize in poetry, 1945, for V-Letter and Other Poems * Shelley Memorial Prize, 1946 * Poetry Consultant at the Library of Congress (United States Poet Laureate), 1946–47 * Kenyon School of Letters fellowship, 1956–57 * Eunice Tietjens Memorial Prize, 1961 * Oscar Blumenthal Prize, Poetry, 1963 * Bollingen Prize, 1968 * Robert Kirsch Award, LA Times, 1989 * Charity Randall Citation, 1990 * Fellow in American Letters, Library of Congress Bibliography Poetry collections * * Adult Bookstore (1976) * Collected Poems, 1940–1978 (1978) * Essay on Rime (1945) * New and Selected Poems, 1940–1987 (1988) * Person, Place, and Thing (1942) * Place of Love (1943) * Poems (1935) * Poems 1940-1953 (1953) * Poems of a Jew (1950) * Selected Poems (Random House, 1968) * Selected Poems (Library of America, 2003), edited by John Updike. * The Bourgeois Poet (1964) * The Old Horsefly (1993) * The Place of Love (1943) * Trial of a Poet (1947) * V-Letter and Other Poems (1945) * White Haired Lover (1968) * The Wild Card: Selected Poems, Early and Late (1998) * Coda: Last Poems (2008) Autobiography * * Poet: Volume I: The Younger Son (1988) * Reports of My Death (1990) * Poet: An Autobiography in Three Parts (Chapel Hill: Algonquin Books, 1988–1990) Essay collections * * The Poetry Wreck (1975) * To Abolish children and Other Essays (1968) * A Primer for Poets (1965) * In Defense of Ignorance (1960) * Randall Jarrell (1967) * Start With the Sun: Studies in the Whitman Tradition, with James E. Miller, Jr., and Bernice Slote (1963) * Prose Keys to Modern Poetry (1962) Novels * * Edsel (1971) Secondary sources * * Lee Bartlett, Karl Shapiro: A Descriptive Bibliography 1933-1977 (New York: Garland, 1979) * Gail Gloston, Karl Shapiro, Delmore Schwartz, and Randall Jarrell: The Image of the Poet in the Late 1940s (Thesis: Reed College, 1957) * Charles F. Madden, Talks With Authors (Carbondale: Southern Illinois U. Press, 1968) * Hans Ostrom, "Karl Shapiro 1913-2000" (poem), in The Coast Starlight: Collected Poems 1976-2006 (Indianapolis, 2006) * Joseph Reino, Karl Shapiro (New York: Twayne, 1981) * Stephen Stepanchev, American Poetry Since 1945: A Critical Survey (1965) * Melvin B. Tolson, Harlem Gallery (1965), with an introduction by Karl Shapiro * Sue Walker, ed., Seriously Meeting Karl Shapiro (Mobile: Negative Capability Press, 1993) * William White, Karl Shapiro: A Bibliography, with a note by Karl Shapiro (Detroit: Wayne State U. Press, 1960) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karl_Shapiro

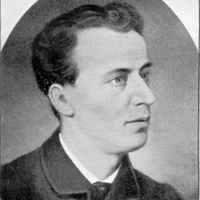

James Thomson (23 November 1834– 3 June 1882), who wrote under the pseudonym Bysshe Vanolis, was a Scottish Victorian-era poet famous primarily for the long poem The City of Dreadful Night (1874), an expression of bleak pessimism in a dehumanized, uncaring urban environment. Life Thomson was born in Port Glasgow, Scotland, and, after his father suffered a stroke, he was sent to London where he was raised in an orphanage, the Royal Caledonian Asylum on Chalk (later Caledonian after the asylum) Road near Holloway. He spoke with a London accent. He received his education at the Caledonian Asylum and the Royal Military Academy and served in Ireland, where in 1851, at the age of 17, he made the acquaintance of the 18-year-old Charles Bradlaugh, who was already notorious as a freethinker, having published his first atheist pamphlet a year earlier. More than a decade later, Thomson left the military and moved to London, where he worked as a clerk. He remained in contact with Bradlaugh, who was by now issuing his own weekly National Reformer, a “publication for the working man”. For the remaining 19 years of his life, starting in 1863, Thomson submitted stories, essays and poems to various publications, including the National Reformer, which published the sombre poem which remains his most famous work. The City of Dreadful Night came about from the struggle with insomnia, alcoholism and chronic depression which plagued Thomson’s final decade. Increasingly isolated from friends and society in general, he even became hostile towards Bradlaugh. In 1880, nineteen months before his death, the publication of his volume of poetry, The City of Dreadful Night and Other Poems elicited encouraging and complimentary reviews from a number of critics, but came too late to prevent Thomson’s downward slide. Thomson’s remaining poems rarely appear in modern anthologies, although the autobiographical Insomnia and Mater Tenebrarum are well-regarded and contain some striking passages. He admired and translated the works of the pessimistic Italian poet Giacomo Leopardi (1798–1837), but his own lack of hope was darker than that of Leopardi. He is considered by some students of the Victorian age as the bleakest of that era’s poets. He died in London at the age of 47. In 1889, seven years after Thomson’s death, Henry Stephens Salt wrote his first major biography, The Life of James Thomson (B.V.). Thomson’s pseudonym, Bysshe Vanolis, derives from the names of the poets Percy Bysshe Shelley and Novalis. He is often distinguished from the earlier Scottish poet James Thomson by the letters B.V. after the name. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Thomson_(poet,_born_1834)