Richard Lovelace (1618–1657) was an English poet in the seventeenth century. He was a cavalier poet who fought on behalf of the king during the Civil war. His best known works are To Althea, from Prison, and To Lucasta, Going to the Warres. Early life and family Richard Lovelace was born in 1618. His exact birthplace is unknown, but it is documented that it was either Woolwich, Kent, or Holland. He was the oldest son of Sir William Lovelace and Anne Barne Lovelace and had four brothers and three sisters. His father was from an old distinguished military and legal family and the Lovelace family owned a considerable amount of property in Kent. His father, Sir William Lovelace, knt., was a member of the Virginia Company and an incorporator in the second Virginia Company in 1609. He was a soldier and he died during the war with Spain and Holland in the siege of Grol, a few days before the town fell. Richard was only 9 years old when his father died. Richard's father was the son of Sir William Lovelace and Elizabeth Aucher who was the daughter of Mabel Wroths and Edward Aucher, Esq. who inherited, under his father's Will, the manors of Bishopsbourne and Hautsborne. Elizabeth's nephew was Sir Anthony Aucher (1614 – 31 May 1692) an English politician and Cavalier during the English Civil War. He was the son of her brother Sir Anthony Aucher and his wife Hester Collett. Richard Lovelace's mother, Anne Barne (1587–1633), was the daughter of Sir William Barne and the granddaughter of Sir George Barne III (1532- d. 1593), the Lord Mayor of London and a prominent merchant and public official from London during the reign of Elizabeth I; and Anne Gerrard, daughter of Sir William Garrard, who was Lord Mayor of London in 1555. Richard Lovelace's mother was also the daughter of Anne Sandys and the granddaughter of Cicely Wilford and the Most Reverend Dr. Edwin Sandys, an Anglican church leader who successively held the posts of the Bishop of Worcester (1559–1570), Bishop of London (1570–1576), and the Archbishop of York (1576–1588). He was one of the translators of the Bishops' Bible. Anne Barne Lovelace married as her second husband, on 20 January 1630, at Greenwich, England, the Very Rev. Dr. Jonathan Browne They were the parents of one child, Anne Browne, who married Herbert Crofte, S.T.P. and D.D and were the parents of Sir Herbert Croft, 1st Baronet. His brother, Francis Lovelace (1621–1675), was the second governor of the New York colony appointed by the Duke of York, later King James II of England. He was also the great nephew of both George Sandys (2 March 1577 – March 1644), an English traveller, colonist and poet; and of Sir Edwin Sandys (9 December 1561 – October 1629), an English statesman and one of the founders of the London Company. In 1629, when Lovelace was eleven, he went to Sutton’s Foundation at Charterhouse School, then located in London. However, there is not a clear record that Lovelace actually attended because it is believed that he studied as a “boarder” because he did not need financial assistance like the “scholars”. He spent five years at Charterhouse, three of which were spent with Richard Crashaw, who also became a poet. On 5 May 1631, Lovelace was sworn in as a “Gentleman Wayter Extraordinary” to the King. This was an “honorary position for which one paid a fee”. He then went on to Gloucester Hall, Oxford, in 1634. Collegiate career Richard Lovelace attended Oxford University and he was praised by one of his contemporaries, Anthony Wood. for being “the most amiable and beautiful person that ever eye beheld; a person also of innate modesty, virtue and courtly deportment, which made him then, but especially after, when he retired to the great city, much admired and adored by the female sex" At the age of eighteen, during a three-week celebration at Oxford, he was granted the degree of Master of Arts. While at school, he tried to portray himself more as a social connoisseur rather than a scholar, continuing his image of being a Cavalier. Being a Cavalier poet, Lovelace wrote to praise a friend or fellow poet, to give advice in grief or love, to define a relationship, to articulate the precise amount of attention a man owes a woman, to celebrate beauty, and to persuade to love. Lovelace wrote a comedy, 'The Scholars,' and a tragedy titled 'The Soldiers,' while at Oxford. He then left for Cambridge University for a few months where he met Lord Goring, who led him into political trouble. Politics and prison Lovelace’s poetry was often influenced by his experiences with politics and association with important figures of his time. At the age of thirteen, Lovelace became a "Gentlemen Wayter Extraordinary" to the King and at nineteen he contributed a verse to a volume of elegies commemorating Princess Katharine. In 1639 Lovelace joined the regiment of Lord Goring, serving first as a senior ensign and later as a captain in the Bishops’ Wars. This experience inspired the 'Sonnet. To Generall Goring.' Upon his return to his home in Kent in 1640, Lovelace served as a country gentleman and a justice of the peace where he encountered firsthand the civil turmoil regarding religion and politics. In 1641 Lovelace led a group of men to seize and destroy a petition for the abolition of Episcopal rule, which had been signed by fifteen thousand people. The following year he presented the House of Commons with Dering’s pro-Royalist petition which was supposed to have been burned. These actions resulted in Lovelace’s first imprisonment. Shortly thereafter, he was released on bail with the stipulation that he avoid communication with the House of Commons without permission. This prevented Lovelace, who had done everything to prove himself during the Bishops’ Wars, from participating in the first phase of the English Civil War. However, this first experience of imprisonment did result in some good, as it brought him to write one of his finest and most beloved lyrics, 'To Althea, from Prison,' in which he illustrates his noble and paradoxical nature. Lovelace did everything he could to remain in the king’s favor despite his inability to participate in the war. Richard Lovelace did his part again during the political chaos of 1648, though it is unclear specifically what his actions were. He did, however, manage to warrant himself another prison sentence; this time for nearly a year. When he was released in April 1649, the king had been executed and Lovelace’s cause seemed lost. As in his previous incarceration, this experience led to creative production—this time in the form of spiritual freedom, as reflected in the release of his first volume of poetry, Lucasta. Literature Richard Lovelace first started writing while he was a student at Oxford and wrote almost 200 poems from that time until his death. His first work was a drama titled The Scholars. The play was never published; however, it was performed at college and then in London. In 1640, he wrote a tragedy titled 'The Soldier' which was based on his own military experience. When serving in the Bishops' Wars, he wrote the sonnet 'To Generall Goring,' which is a poem of Bacchanalian celebration rather than a glorification of military action. One of his extremely famous poems is 'To Lucasta, Going to the Warres,' written in 1640 and exposed in his first political action. During his first imprisonment in 1642, he wrote his most famous poem 'To Althea, From Prison.' Later on that year during his travels to Holland with General Goring, he wrote 'The Rose,' following with 'The Scrutiny' and on 14 May 1649, 'Lucasta' was published. He also wrote poems analyzing the details of many simple insects. 'The Ant,' 'The Grasse-hopper,' 'The Snayl,' 'The Falcon,' 'The Toad and Spyder.' Of these poems, 'The Grasse-hopper' is his most well-known. In 1660, after Lovelace died, "Lucasta: Postume Poems" was published; it contains 'A Mock-Song,' which has a much darker tone than his previous works. William Winstanley, who praised much of Richard Lovelace's works, thought highly of him and compared him to an idol; "I can compare no Man so like this Colonel Lovelace as Sir Philip Sidney,” of which it is in an Epitaph made of him; Nor is it fit that more I should aquaint Lest Men adore in one A Scholar, Souldier, Lover, and a Saint His most quoted excerpts are from the beginning of the last stanza of To Althea, From Prison: Stone walls do not a prison make, Nor iron bars a cage; Minds innocent and quiet take That for an hermitage and the end of To Lucasta. Going to the Warres: I could not love thee, dear, so much, Lov'd I not Honour more. Chronology 1618- Richard Lovelace born, either in Woolwich, Kent, or in Holland. 1629- King Charles I nominated “Thomas [probably Richard] Lovelace,” upon petition of Lovelace’s mother, Anne Barne Lovelace, to Sutton’s foundation at Charterhouse. 1631- On 5 May, Lovelace is made “Gentleman Wayter Extraordinary” to the King. 1634- On 27 June, he matriculates as Gentleman Commoner at Gloucester Hall, Oxford. 1635- Writes a comedy, The Scholars. 1636- On 31 August, the degree of M.A. is presented to him. 1637- On 4 October, he enters Cambridge University. 1638-1639- His first printed poems appear: ‘An Elegy” on Princess Katherine; prefaces to several books. 1639- He is senior ensign in General Goring’s regiment - in the First Scottish Expedition. “Sonnet to Goring.” 1640- Commissioned captain in the Second Scottish Expedition; writes a tragedy, The Soldier. He then returns home at 21, into the possession of his family’s property. 1641- Lovelace tears up a pro-Parliament, anti-Episcopacy petition at a meeting in Maidstone, Kent. 1642- 30 April, he presents the anti-Parliamentary Petition of Kent and is imprisoned at Gatehouse. After appealing, he is released on bail, 21 June. The Civil war begins on 22 August, he writes “To Althea, from Prison,” “To Lucasta.” In September, he goes to Holland with General Goring. He writes “The Rose.” 1642-1646-Probably serves in Holland and France with General Goring. He writes “The Scrutiny.” 1643- Sells some of his property to Richard Hulse. 1646- In October, he is wounded at Dunkirk, while fighting under the Great Conde against the Spaniards. 1647- He is admitted to the Freedom at the Painters’ Company. 1648-On 4 February, Lucasta is licensed at the Stationer’s Register. On 9 June, Lovelace is again imprisoned at Peterhouse. 1649- On 9 April, he is released from jail. He then sells the remaining family property and portraits to Richard Hulse. On 14 May, Lucasta is published. 1650-1657- Lovelace’s whereabouts unknown, though various poems are written. 1657- Lovelace dies. 1659-1660- Lucasta, Postume Poems is published. References Wikipedia - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Lovelace

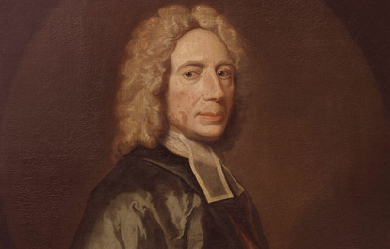

Isaac Watts (17 July 1674– 25 November 1748) was an English Christian minister, hymnwriter, theologian and logician. A prolific and popular hymn writer, his work was part of evangelization. He was recognized as the “Father of English Hymnody”, credited with some 750 hymns. Many of his hymns remain in use today and have been translated into numerous languages.

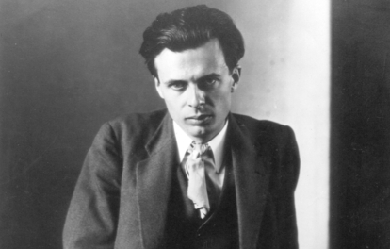

John Milton (9 December 1608 – 8 November 1674) was an English poet, polemicist, a scholarly man of letters, and a civil servant for the Commonwealth (republic) of England under Oliver Cromwell. He wrote at a time of religious flux and political upheaval, and is best known for his epic poem Paradise Lost. Milton's poetry and prose reflect deep personal convictions, a passion for freedom and self determination, and the urgent issues and political turbulence of his day. Writing in English, Latin, and Italian, he achieved international renown within his lifetime, and his celebrated Areopagitica, (written in condemnation of pre-publication censorship) is among history’s most influential and impassioned defenses of free speech and freedom of the press.

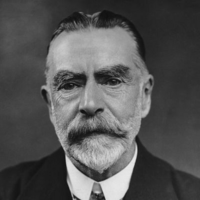

William Ernest Henley (23 August 1849 – 11 July 1903) was an English poet, critic and editor, best remembered for his 1875 poem “Invictus”. Henley was born in Gloucester and was the oldest of a family of six children, five sons and a daughter. His father, William, a bookseller and stationer, died in 1868 and was survived by young children and creditors. His mother, Mary Morgan, was descended from the poet and critic Joseph Wharton. Between 1861 and 1867, Henley was a pupil at the Crypt Grammar School (founded 1539).

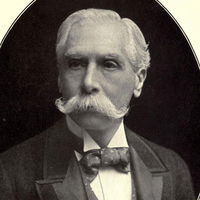

John Newton (24 July 1725– 21 December 1807) was an English sailor, in the Royal Navy for a period, and later a captain of slave ships. He became ordained as an evangelical Anglican cleric, served Olney, Buckinghamshire for two decades, and also wrote hymns, known for “Amazing Grace” and “Glorious Things of Thee Are Spoken”. Newton started his career at sea at a young age, and worked on slave ships in the slave trade for several years. After experiencing a period of Christian conversion Newton eventually renounced his trade and became a prominent supporter of abolitionism, living to see Britain’s abolition of the African slave trade in 1807. Early life John Newton was born in Wapping, London, in 1725, the son of Elizabeth (née Scatliff) and John Newton Sr., a shipmaster in the Mediterranean service. Elizabeth was the only daughter of Simon Scatliff, an instrument maker from London (the marriage register records her maiden name as Seatcliffe). Elizabeth was brought up as a Nonconformist. She died of tuberculosis (then called consumption) in July 1732, about two weeks before John’s seventh birthday. Newton spent two years at boarding school before going to live in Aveley in Essex, the home of his father’s new wife. At age eleven he first went to sea with his father. Newton sailed six voyages before his father retired in 1742. At that time, Newton’s father made plans for him to work at a sugarcane plantation in Jamaica. Instead, Newton signed on with a merchant ship sailing to the Mediterranean Sea. Impressment into naval service In 1743, while going to visit friends, Newton was captured and pressed into the naval service by the Royal Navy. He became a midshipman aboard HMS Harwich. At one point Newton tried to desert and was punished in front of the crew of 350. Stripped to the waist and tied to the grating, he received a flogging of eight dozen lashes and was reduced to the rank of a common seaman. Following that disgrace and humiliation, Newton initially contemplated murdering the captain and committing suicide by throwing himself overboard. He recovered, both physically and mentally. Later, while Harwich was en route to India, he transferred to Pegasus, a slave ship bound for West Africa. The ship carried goods to Africa and traded them for slaves to be shipped to the colonies in the Caribbean and North America. Enslavement and rescue Newton did not get along with the crew of Pegasus. They left him in West Africa with Amos Clowe, a slave dealer. Clowe took Newton to the coast and gave him to his wife, Princess Peye of the Sherbro people. She abused and mistreated Newton equally as much as she did her other slaves. Newton later recounted this period as the time he was “once an infidel and libertine, a servant of slaves in West Africa.” Early in 1748 he was rescued by a sea captain who had been asked by Newton’s father to search for him, and returned to England on the merchant ship Greyhound, which was carrying beeswax and dyer’s wood, now referred to as camwood. Spiritual conversion During his 1748 voyage to England after his rescue, Newton had a spiritual conversion. The ship encountered a severe storm off the coast of County Donegal in Ulster, Ireland, and almost sank. Newton awoke in the middle of the night and, as the ship filled with water, called out to God. The cargo shifted and stopped up the hole, and the ship drifted to safety. Newton marked this experience as the beginning of his conversion to evangelical Christianity. He began to read the Bible and other religious literature. By the time he reached Britain, he had accepted the doctrines of evangelical Christianity. The date was 10 March 1748, an anniversary he marked for the rest of his life. From that point on, he avoided profanity, gambling, and drinking. Although he continued to work in the slave trade, he had gained sympathy for the slaves during his time in Africa. He later said that his true conversion did not happen until some time later: “I cannot consider myself to have been a believer in the full sense of the word, until a considerable time afterwards.” Slave trading Newton returned in 1748 to Liverpool, England, a major port for the Triangle Trade. Partly due to the influence of his father’s friend Joseph Manesty, he obtained a position as first mate aboard the slave ship Brownlow, bound for the West Indies via the coast of Guinea. While in west Africa (1748–49), Newton acknowledged the inadequacy of his spiritual life. He became ill with a fever and professed his full belief in Christ, asking God to take control of his destiny. He later said that this was the first time he felt totally at peace with God. Newton did not however immediately renounce working in the slave trade. After his return to England in 1750, he made three voyages as captain of the slave ships Duke of Argyle (1750) and African (1752–53 and 1753–54). After suffering a severe stroke in 1754, he gave up seafaring and slave-trading activities. But he continued to invest in Manesty’s slaving operations. Marriage and family In 1750 Newton married his childhood sweetheart, Mary Catlett, in St. Margaret’s Church, Rochester. Newton adopted his two orphaned nieces, Elizabeth and Eliza Catlett, children of one of his brothers-in-law and his wife. Newton’s niece Alys Newton later married Mehul, a prince from India. Anglican priest In 1755 Newton was appointed as tide surveyor (a tax collector) of the Port of Liverpool, again through the influence of Manesty. In his spare time, he studied Greek, Hebrew, and Syriac, preparing for serious religious study. He became well known as an evangelical lay minister. In 1757, he applied to be ordained as a priest in the Church of England, but it was more than seven years before he was eventually accepted. During this period, he also applied to the Methodists, Independents and Presbyterians. He mailed applications directly to the Bishops of Chester and Lincoln and the Archbishops of Canterbury and York. Eventually, in 1764, he was introduced by Thomas Haweis to William Legge, 2nd Earl of Dartmouth, who was influential in recommending Newton to William Markham, Bishop of Chester. Haweis suggested Newton for the living of Olney, Buckinghamshire. On 29 April 1764 Newton received deacon’s orders, and finally was ordained as a priest on 17 June. As curate of Olney, Newton was partly sponsored by John Thornton, a wealthy merchant and evangelical philanthropist. He supplemented Newton’s stipend of £60 a year with £200 a year “for hospitality and to help the poor”. Newton soon became well known for his pastoral care, as much as for his beliefs. His friendship with Dissenters and evangelical clergy led to his being respected by Anglicans and Nonconformists alike. He spent sixteen years at Olney. His preaching was so popular that the congregation added a gallery to the church to accommodate the many persons who flocked to hear him. Some five years later, in 1772, Thomas Scott took up the curacy of the neighbouring parishes of Stoke Goldington and Weston Underwood. Newton was instrumental in converting Scott from a cynical ‘career priest’ to a true believer, a conversion which Scott related in his spiritual autobiography The Force Of Truth (1779). Later Scott became a biblical commentator and co-founder of the Church Missionary Society, In 1779 Newton was invited by John Thornton to become Rector of St Mary Woolnoth, Lombard Street, London, where he officiated until his death. The church had been built by Nicholas Hawksmoor in 1727 in the fashionable Baroque style. Newton was one of only two evangelical Anglican priests in the capital, and he soon found himself gaining in popularity amongst the growing evangelical party. He was a strong supporter of evangelicalism in the Church of England. He remained a friend of Dissenters (such as Methodists and Baptists) as well as Anglicans. Young churchmen and people struggling with faith sought his advice, including such well-known social figures as the writer and philanthropist Hannah More, and the young William Wilberforce, a Member of Parliament who had recently suffered a crisis of conscience and religious conversion while contemplating leaving politics. The younger man consulted with Newton, who encouraged Wilberforce to stay in Parliament and “serve God where he was”. In 1792, Newton was presented with the degree of Doctor of Divinity by the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University). Abolitionist In 1788, 34 years after he had retired from the slave trade, Newton broke a long silence on the subject with the publication of a forceful pamphlet Thoughts Upon the Slave Trade, in which he described the horrific conditions of the slave ships during the Middle Passage. He apologized for “a confession, which... comes too late... It will always be a subject of humiliating reflection to me, that I was once an active instrument in a business at which my heart now shudders.” He had copies sent to every MP, and the pamphlet sold so well that it swiftly required reprinting. Newton became an ally of William Wilberforce, leader of the Parliamentary campaign to abolish the African slave trade. He lived to see the British passage of the Slave Trade Act 1807, which enacted this event. Some modern writers have criticised Newton for continuing to participate in the slave trade after his religious conversion, but Christianity did not deter thousands of slaveholders in the colonies from owning other men, nor many others from profiting by the slave trade. Newton came to believe that during the first five of his nine years as a slave trader he had not been a Christian in the full sense of the term. In 1763 he wrote: “I was greatly deficient in many respects... I cannot consider myself to have been a believer in the full sense of the word, until a considerable time afterwards.” Writer and hymnist In 1767 William Cowper, the poet, moved to Olney. He worshipped in Newton’s church, and collaborated with the priest on a volume of hymns; it was published as Olney Hymns in 1779. This work had a great influence on English hymnology. The volume included Newton’s well-known hymns: “Glorious Things of Thee Are Spoken,” “How Sweet the Name of Jesus Sounds!,” “Let Us Love, and Sing, and Wonder,” “Come, My Soul, Thy Suit Prepare,” “Approach, My Soul, the Mercy-seat”, and “Faith’s Review and Expectation,” which has come to be known by its opening phrase, “Amazing Grace”. Many of Newton’s (as well as Cowper’s) hymns are preserved in the Sacred Harp, a hymnal used in the American South during the Second Great Awakening. Hymns were scored according to the tonal scale for shape note singing. Easily learned and incorporating singers into four-part harmony, shape note music was widely used by evangelical preachers to reach new congregants. Newton also contributed to the Cheap Repository Tracts. He wrote an autobiography entitled An Authentic Narrative of Some Remarkable And Interesting Particulars in the Life of———Communicated, in a Series of Letters, to the Reverend T. Haweiss, which he published anonymously. It was later described as 'written in an easy style, distinguished by great natural shrewdness, and sanctified by the Lord God and prayer’. Final years Newton’s wife Mary Catlett died in 1790, after which he published Letters to a Wife (1793), in which he expressed his grief. Plagued by ill health and failing eyesight, Newton died on 21 December 1807 in London. He was buried beside his wife in St. Mary Woolnoth in London. Both were reinterred at the Church of St. Peter and Paul in Olney in 1893. Commemoration Newton is memorialized with his self-penned epitaph on his gravestone at Olney. When he was initially interred in London, a memorial plaque to Newton, containing his self-penned epitaph, was installed on the wall of St Mary Woolnoth. At the bottom of the plaque are the words: "The above Epitaph was written by the Deceased who directed it to be inscribed on a plain Marble Tablet. He died on December the 21st December 1807. Aged 82 Years, and his Mortal Remains are deposited in the Vault beneath the Church.” The town of Newton, Sierra Leone is named after him. To this day his former town of Olney provides philanthropy for the African town. In 1982, Newton was recognized for his influential hymns by the Gospel Music Association when he was inducted into the Gospel Music Hall of Fame. Portrayals in media Film The film Amazing Grace (2006) highlights Newton’s influence on William Wilberforce. Albert Finney portrays Newton, Ioan Gruffudd is Wilberforce, and the film was directed by Michael Apted. The film portrays Newton as a penitent haunted by the ghosts of 20,000 slaves. The Nigerian film The Amazing Grace (2006), the creation of Nigerian director/writer/producer Jeta Amata, provides an African perspective on the slave trade. Nigerian actors Joke Silva, Mbong Odungide, and Fred Amata (brother of the director) portray Africans who are captured and taken away from their homeland by slave traders. Newton is played by Nick Moran. The 2014 film Freedom tells the story of an American slave (Samuel Woodward, played by Cuba Gooding, Jr.) escaping to freedom via the Underground Railroad. A parallel earlier story depicts John Newton (played by Bernhard Forcher) as the captain of a slave ship bound for America carrying Samuel’s grandfather. Newton’s conversion is explored as well. Stage productions African Snow (2007), a play by Murray Watts, takes place in the mind of John Newton. It was first produced at the York Theatre Royal as a co-production with Riding Lights Theatre Company, transferring to the Trafalgar Studios in London’s West End and a National Tour. Newton was played by Roger Alborough and Olaudah Equiano by Israel Oyelumade. The musical Amazing Grace is a dramatisation of Newton’s life. The 2014 pre-Broadway and 2015 Broadway productions starred Josh Young as Newton. Television Newton is portrayed by actor John Castle in the British television miniseries, The Fight Against Slavery (1975). Novels Caryl Phillips’ novel, Crossing the River (1993), includes nearly verbatim excerpts of Newton’s logs from his Journal of a Slave Trader. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Newton

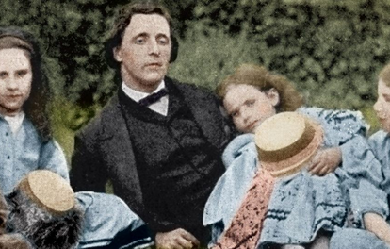

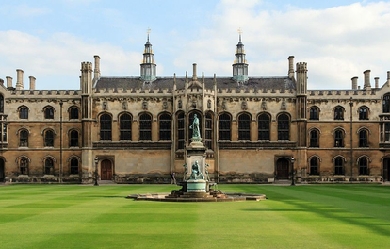

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (27 January 1832 – 14 January 1898), better known by the pseudonym Lewis Carroll, was an English author, mathematician, logician, Anglican deacon and photographer. His most famous writings are Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and its sequel Through the Looking-Glass, as well as the poems "The Hunting of the Snark" and "Jabberwocky", all examples of the genre of literary nonsense. He is noted for his facility at word play, logic, and fantasy, and there are societies in many parts of the world (including the United Kingdom, Japan, the United States, and New Zealand) dedicated to the enjoyment and promotion of his works and the investigation of his life. Antecedents Dodgson's family was predominantly northern English, with Irish connections. Conservative and High Church Anglican, most of Dodgson's ancestors were army officers or Church of England clergy. His great-grandfather, also named Charles Dodgson, had risen through the ranks of the church to become the Bishop of Elphin. His grandfather, another Charles, had been an army captain, killed in action in Ireland in 1803 when his two sons were hardly more than babies. His mother's name was Frances Jane Lutwidge. The elder of these sons – yet another Charles Dodgson – was Carroll's father. He reverted to the other family tradition and took holy orders. He went to Westminster School, and then to Christ Church, Oxford. He was mathematically gifted and won a double first degree, which could have been the prelude to a brilliant academic career. Instead he married his first cousin in 1827 and became a country parson. Dodgson was born in the little parsonage of Daresbury in Cheshire near the towns of Warrington and Runcorn, the eldest boy but already the third child of the four-and-a-half-year-old marriage. Eight more children were to follow. When Charles was 11, his father was given the living of Croft-on-Tees in North Yorkshire, and the whole family moved to the spacious rectory. This remained their home for the next twenty-five years. Young Charles' father was an active and highly conservative cleric of the Church of England who later became the Archdeacon of Richmond and involved himself, sometimes influentially, in the intense religious disputes that were dividing the church. He was High Church, inclining to Anglo-Catholicism, an admirer of John Henry Newman and the Tractarian movement, and did his best to instill such views in his children. Young Charles was to develop an ambiguous relationship with his father's values and with the Church of England as a whole. Education Home life During his early youth, Dodgson was educated at home. His "reading lists" preserved in the family archives testify to a precocious intellect: at the age of seven the child was reading The Pilgrim's Progress. He also suffered from a stammer – a condition shared by most of his siblings – that often influenced his social life throughout his years. At age twelve he was sent to Richmond Grammar School (now part of Richmond School) at nearby Richmond. Rugby In 1846, young Dodgson moved on to Rugby School, where he was evidently less happy, for as he wrote some years after leaving the place: I cannot say ... that any earthly considerations would induce me to go through my three years again ... I can honestly say that if I could have been ... secure from annoyance at night, the hardships of the daily life would have been comparative trifles to bear. Scholastically, though, he excelled with apparent ease. "I have not had a more promising boy at his age since I came to Rugby", observed R.B. Mayor, then Mathematics master. Oxford He left Rugby at the end of 1849 and matriculated at Oxford in May 1850 as a member of his father's old college, Christ Church. After waiting for rooms in college to become available, he went into residence in January 1851. He had been at Oxford only two days when he received a summons home. His mother had died of "inflammation of the brain" – perhaps meningitis or a stroke – at the age of forty-seven. His early academic career veered between high promise and irresistible distraction. He did not always work hard, but was exceptionally gifted and achievement came easily to him. In 1852 he obtained first-class honours in Mathematics Moderations, and was shortly thereafter nominated to a Studentship by his father's old friend, Canon Edward Pusey. In 1854 he obtained first-class honours in the Final Honours School of Mathematics, graduating Bachelor of Arts. He remained at Christ Church studying and teaching, but the next year he failed an important scholarship through his self-confessed inability to apply himself to study. Even so, his talent as a mathematician won him the Christ Church Mathematical Lectureship in 1855, which he continued to hold for the next twenty-six years. Despite early unhappiness, Dodgson was to remain at Christ Church, in various capacities, until his death. Character and appearance Health challenges The young adult Charles Dodgson was about six feet tall, slender, and had curling brown hair and blue or grey eyes (depending on the account). He was described in later life as somewhat asymmetrical, and as carrying himself rather stiffly and awkwardly, though this may be on account of a knee injury sustained in middle age. As a very young child, he suffered a fever that left him deaf in one ear. At the age of seventeen, he suffered a severe attack of whooping cough, which was probably responsible for his chronically weak chest in later life. Another defect he carried into adulthood was what he referred to as his "hesitation", a stammer he acquired in early childhood and which plagued him throughout his life. The stammer has always been a potent part of the conceptions of Dodgson; it is part of the belief that he stammered only in adult company and was free and fluent with children, but there is no evidence to support this idea. Many children of his acquaintance remembered the stammer while many adults failed to notice it. Dodgson himself seems to have been far more acutely aware of it than most people he met; it is said he caricatured himself as the Dodo in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, referring to his difficulty in pronouncing his last name, but this is one of the many "facts" often-repeated, for which no firsthand evidence remains. He did indeed refer to himself as the dodo, but that this was a reference to his stammer is simply speculation. Although Dodgson's stammer troubled him, it was never so debilitating that it prevented him from applying his other personal qualities to do well in society. At a time when people commonly devised their own amusements and when singing and recitation were required social skills, the young Dodgson was well-equipped to be an engaging entertainer. He reportedly could sing tolerably well and was not afraid to do so before an audience. He was adept at mimicry and storytelling, and was reputedly quite good at charades. Social connections In the interim between his early published writing and the success of the Alice books, Dodgson began to move in the Pre-Raphaelite social circle. He first met John Ruskin in 1857 and became friendly with him. He developed a close relationship with Dante Gabriel Rossetti and his family, and also knew William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, and Arthur Hughes, among other artists. He also knew the fairy-tale author George MacDonald well – it was the enthusiastic reception of Alice by the young MacDonald children that convinced him to submit the work for publication. Politics, religion and philosophy In broad terms, Dodgson has traditionally been regarded as politically, religiously, and personally conservative. Martin Gardner labels Dodgson as a Tory who was "awed by lords and inclined to be snobbish towards inferiors." The Revd W. Tuckwell, in his Reminiscences of Oxford (1900), regarded him as "austere, shy, precise, absorbed in mathematical reverie, watchfully tenacious of his dignity, stiffly conservative in political, theological, social theory, his life mapped out in squares like Alice's landscape." However, Dodgson also expressed interest in philosophies and religions that seem at odds with this assessment. For example, he was a founding member of the Society for Psychical Research. It has been argued by the proponents of the 'Carroll Myth' that these factors require a reconsideration of Gardner's diagnosis, and that perhaps, Dodgson's true outlook was more complex than previously believed (see 'the Carroll Myth' below). Dodgson wrote some studies of various philosophical arguments. In 1895, he developed a philosophical regressus-argument on deductive reasoning in his article "What the Tortoise Said to Achilles", which appeared in one of the early volumes of the philosophical journal Mind. The article was reprinted in the same journal a hundred years later, in 1995, with a subsequent article by Simon Blackburn titled Practical Tortoise Raising. Artistic activities Literature From a young age, Dodgson wrote poetry and short stories, both contributing heavily to the family magazine Mischmasch and later sending them to various magazines, enjoying moderate success. Between 1854 and 1856, his work appeared in the national publications, The Comic Times and The Train, as well as smaller magazines like the Whitby Gazette and the Oxford Critic. Most of this output was humorous, sometimes satirical, but his standards and ambitions were exacting. "I do not think I have yet written anything worthy of real publication (in which I do not include the Whitby Gazette or the Oxonian Advertiser), but I do not despair of doing so some day," he wrote in July 1855. Sometime after 1850, he did write puppet plays for his siblings' entertainment, of which one has survived, La Guida di Bragia. In 1856 he published his first piece of work under the name that would make him famous. A romantic poem called "Solitude" appeared in The Train under the authorship of "Lewis Carroll." This pseudonym was a play on his real name; Lewis was the anglicised form of Ludovicus, which was the Latin for Lutwidge, and Carroll an Irish surname similar to the Latin name Carolus, from which the name Charles comes. Alice In the same year, 1856, a new Dean, Henry Liddell, arrived at Christ Church, bringing with him his young family, all of whom would figure largely in Dodgson's life and, over the following years, greatly influence his writing career. Dodgson became close friends with Liddell's wife, Lorina, and their children, particularly the three sisters: Lorina, Edith and Alice Liddell. He was for many years widely assumed to have derived his own "Alice" from Alice Liddell. This was given some apparent substance by the fact the acrostic poem at the end of Through the Looking Glass spells out her name, and that there are many superficial references to her hidden in the text of both books. It has been pointed out that Dodgson himself repeatedly denied in later life that his "little heroine" was based on any real child, and frequently dedicated his works to girls of his acquaintance, adding their names in acrostic poems at the beginning of the text. Gertrude Chataway's name appears in this form at the beginning of The Hunting of the Snark, and no one has ever suggested this means any of the characters in the narrative are based on her. Though information is scarce (Dodgson's diaries for the years 1858–1862 are missing), it does seem clear that his friendship with the Liddell family was an important part of his life in the late 1850s, and he grew into the habit of taking the children (first the boy, Harry, and later the three girls) on rowing trips accompanied by an adult friend to nearby Nuneham Courtenay or Godstow. It was on one such expedition, on 4 July 1862, that Dodgson invented the outline of the story that eventually became his first and largest commercial success. Having told the story and been begged by Alice Liddell to write it down, Dodgson eventually (after much delay) presented her with a handwritten, illustrated manuscript entitled Alice's Adventures Under Ground in November 1864. Before this, the family of friend and mentor George MacDonald read Dodgson's incomplete manuscript, and the enthusiasm of the MacDonald children encouraged Dodgson to seek publication. In 1863, he had taken the unfinished manuscript to Macmillan the publisher, who liked it immediately. After the possible alternative titles Alice Among the Fairies and Alice's Golden Hour were rejected, the work was finally published as Alice's Adventures in Wonderland in 1865 under the Lewis Carroll pen-name, which Dodgson had first used some nine years earlier. The illustrations this time were by Sir John Tenniel; Dodgson evidently thought that a published book would need the skills of a professional artist. The overwhelming commercial success of the first Alice book changed Dodgson's life in many ways. The fame of his alter ego "Lewis Carroll" soon spread around the world. He was inundated with fan mail and with sometimes unwanted attention. Indeed, according to one popular story, Queen Victoria herself enjoyed Alice In Wonderland so much that she suggested he dedicate his next book to her, and was accordingly presented with his next work, a scholarly mathematical volume entitled An Elementary Treatise on Determinants. Dodgson himself vehemently denied this story, commenting "...It is utterly false in every particular: nothing even resembling it has occurred"; and it is unlikely for other reasons: as T.B. Strong comments in a Times article, "It would have been clean contrary to all his practice to identify [the] author of Alice with the author of his mathematical works". He also began earning quite substantial sums of money but continued with his seemingly disliked post at Christ Church. Late in 1871, a sequel – Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There – was published. (The title page of the first edition erroneously gives "1872" as the date of publication.) Its somewhat darker mood possibly reflects the changes in Dodgson's life. His father had recently died (1868), plunging him into a depression that lasted some years. The Hunting of the Snark In 1876, Dodgson produced his last great work, The Hunting of the Snark, a fantastical "nonsense" poem, exploring the adventures of a bizarre crew of tradesmen, and one beaver, who set off to find the eponymous creature. The painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti reputedly became convinced the poem was about him. Photography In 1856, Dodgson took up the new art form of photography, first under the influence of his uncle Skeffington Lutwidge, and later his Oxford friend Reginald Southey. He soon excelled at the art and became a well-known gentleman-photographer, and he seems even to have toyed with the idea of making a living out of it in his very early years. A recent study by Roger Taylor and Edward Wakeling exhaustively lists every surviving print, and Taylor calculates that just over fifty percent of his surviving work depicts young girls, though this may be a highly distorted figure as approximately 60% of his original photographic portfolio is now missing, so any firm conclusions are difficult. Dodgson also made many studies of men, women, male children and landscapes; his subjects also include skeletons, dolls, dogs, statues and paintings, and trees. His pictures of children were taken with a parent in attendance and many of the pictures were taken in the Liddell garden, because natural sunlight was required for good exposures. He also found photography to be a useful entrée into higher social circles. During the most productive part of his career, he made portraits of notable sitters such as John Everett Millais, Ellen Terry, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Julia Margaret Cameron, Michael Faraday and Alfred, Lord Tennyson. Dodgson abruptly ceased photography in 1880. Over 24 years, he had completely mastered the medium, set up his own studio on the roof of Tom Quad, and created around 3, images. Fewer than 1, have survived time and deliberate destruction. He reported that he stopped taking photographs because keeping his studio working was difficult (he used the wet collodion process) and commercial photographers (who started using the dry plate process in the 1870s) took pictures more quickly. With the advent of Modernism, tastes changed, and his photography was forgotten from around 1920 until the 1960s. Inventions To promote letter writing, Dodgson invented The Wonderland Postage-Stamp Case in 1889. This was a cloth-backed folder with twelve slots, two marked for inserting the then most commonly used penny stamp, and one each for the other current denominations to one shilling. The folder was then put into a slip case decorated with a picture of Alice on the front and the Cheshire Cat on the back. All could be conveniently carried in a pocket or purse. When issued it also included a copy of Carroll's pamphletted lecture, Eight or Nine Wise Words About Letter-Writing. Reconstructed nyctograph, with scale demonstrated by a 5 euro cent. Another invention is a writing tablet called the nyctograph for use at night that allowed for note-taking in the dark; thus eliminating the trouble of getting out of bed and striking a light when one wakes with an idea. The device consisted of a gridded card with sixteen squares and system of symbols representing an alphabet of Dodgson's design, using letter shapes similar to the Graffiti writing system on a Palm device. Among the games he devised outside of logic there are a number of word games, including an early version of what today is known as Scrabble. He also appears to have invented, or at least certainly popularised, the Word Ladder (or "doublet" as it was known at first); a form of brain-teaser that is still popular today: the game of changing one word into another by altering one letter at a time, each successive change always resulting in a genuine word. For instance, CAT is transformed into DOG by the following steps: CAT, COT, DOT, DOG. Other items include a rule for finding the day of the week for any date; a means for justifying right margins on a typewriter; a steering device for a velociam (a type of tricycle); new systems of parliamentary representation; more nearly fair elimination rules for tennis tournaments; a new sort of postal money order; rules for reckoning postage; rules for a win in betting; rules for dividing a number by various divisors; a cardboard scale for the college common room he worked in later in life, which, held next to a glass, ensured the right amount of liqueur for the price paid; a double-sided adhesive strip for things like the fastening of envelopes or mounting things in books; a device for helping a bedridden invalid to read from a book placed sideways; and at least two ciphers for cryptography. Mathematical work Within the academic discipline of mathematics, Dodgson worked primarily in the fields of geometry, matrix algebra, mathematical logic and recreational mathematics, producing nearly a dozen books under his real name. Dodgson also developed new ideas in the study of elections (e.g., Dodgson's method) and committees; some of this work was not published until well after his death. He worked as a mathematics tutor at Oxford, an occupation that gave him some financial security. Later years Over the remaining twenty years of his life, throughout his growing wealth and fame, his existence remained little changed. He continued to teach at Christ Church until 1881, and remained in residence there until his death. His last novel, the two-volume Sylvie and Bruno, was published in 1889 and 1893 respectively. It achieved nowhere near the success of the Alice books. Its intricacy was apparently not appreciated by contemporary readers. The reviews and its sales, only 13, copies, were disappointing. The only occasion on which (as far as is known) he travelled abroad was a trip to Russia in 1867 as an ecclesiastical together with the Reverend Henry Liddon. He recounts the travel in his "Russian Journal", which was first commercially published in 1935. On his way to Russia and back Lewis Carroll also saw different cities in Belgium, Germany, the partitioned Poland, and France. He died on 14 January 1898 at his sisters' home, "The Chestnuts" in Guildford, of pneumonia following influenza. He was two weeks away from turning 66 years old. He is buried in Guildford at the Mount Cemetery. Controversies and mysteries "Carroll Myth” Since 1999 a group of scholars, notably Karoline Leach, Hugues Lebailly and Sherry L. Ackerman, John Tufail, Douglas Nickel and others, argue that what Leach terms the "Carroll Myth" has wildly distorted biographical perception of his life and his work. Leach's book, In the Shadow of the Dreamchild, raised a considerable amount of controversy. In brief the claim is that: * In general terms Dodgson's life has been simplified and 'infantilised' by a combination of inaccurate biography and the longstanding unavailability of key evidence, which allowed legends to proliferate unchecked. * By the time the evidence did become available the 'mythic' image of the man had become so embedded in scholastic and popular thinking it remained unquestioned, despite the fact the evidence failed to support it. * If the evidence is examined dispassionately it shows many of the most famous legends about the man (e.g. his 'paedophilia', and his exclusive adoration of small girls) are untrue, or at least grossly simplified. In more detail, Lebailly has endeavoured to set Dodgson's child-photography within the "Victorian Child Cult", which perceived child-nudity as essentially an expression of innocence. Lebailly claims that studies of child nudes were mainstream and fashionable in Dodgson's time and that most photographers, including Oscar Gustave Rejlander and Julia Margaret Cameron, made them as a matter of course. Lebailly continues that child nudes even appeared on Victorian Christmas cards, implying a very different social and aesthetic assessment of such material. Lebailly concludes that it has been an error of Dodgson's biographers to view his child-photography with 20th or 21st century eyes, and to have presented it as some form of personal idiosyncrasy, when it was in fact a response to a prevalent aesthetic and philosophical movement of the time. Leach's reappraisal of Dodgson focused in particular on his controversial sexuality. She argues that the allegations of paedophilia rose initially from a misunderstanding of Victorian morals, as well as the mistaken idea, fostered by Dodgson's various biographers, that he had no interest in adult women. She termed the traditional image of Dodgson "the Carroll Myth". She drew attention to the large amounts of evidence in his diaries and letters that he was also keenly interested in adult women, married and single, and enjoyed several scandalous (by the social standards of his time) relationships with them. She also pointed to the fact that many of those he described as "child-friends" were girls in their late teens and even twenties. She argues that suggestions of paedophilia evolved only many years after his death, when his well-meaning family had suppressed all evidence of his relationships with women in an effort to preserve his reputation, thus giving a false impression of a man interested only in little girls. Similarly, Leach traces the claim that many of Carroll's female friendships ended when the girls reached the age of 14 to a 1932 biography by Langford Reed. The concept of the Carroll Myth has produced polarised reactions from Carroll scholars. In 2004 Contrariwise, the Association for new Lewis Carroll studies. was established, and those such as Carolyn Sigler and Cristopher Hollingsworth have joined the ranks of those calling for a major reassessment. But the concept of the Myth has been opposed by some leading Carroll scholars, in particular Morton N. Cohen and Martin Gardner (their comments, and those of more positive reviewers, can be found on Karoline Leach's own page). Biographer Jenny Woolf, while agreeing that Carroll's image has been comprehensively misrepresented in the past, believes that this can be attributed partly to Carroll's own behaviour and in particular his tendency to self-caricature in later life. Ordination Dodgson had been groomed for the ordained ministry in the Anglican Church from a very early age and was expected, as a condition of his residency at Christ Church, to take holy orders within four years of obtaining his master's degree. He delayed the process for some time but eventually took deacon's orders on 22 December 1861. But when the time came a year later to progress to priestly orders, Dodgson appealed to the dean for permission not to proceed. This was against college rules and initially Dean Liddell told him he would have to consult the college ruling body, which would almost undoubtedly have resulted in his being expelled. For unknown reasons, Dean Liddell changed his mind overnight and permitted Dodgson to remain at the college in defiance of the rules. Uniquely amongst senior students of his time Dodgson never became a priest. There is currently no conclusive evidence about why Dodgson rejected the priesthood. Some have suggested his stammer made him reluctant to take the step, because he was afraid of having to preach. Wilson quotes letters by Dodgson describing difficulty in reading lessons and prayers rather than preaching in his own words. But Dodgson did indeed preach in later life, even though not in priest's orders, so it seems unlikely his impediment was a major factor affecting his choice. Wilson also points out that the then Bishop of Oxford, Samuel Wilberforce, who ordained Dodgson, had strong views against clergy going to the theatre, one of Dodgson's great interests. Others have suggested that he was having serious doubts about Anglicanism. He was interested in minority forms of Christianity (he was an admirer of F.D. Maurice) and "alternative" religions (theosophy). Dodgson became deeply troubled by an unexplained sense of sin and guilt at this time (the early 1860s) and frequently expressed the view in his diaries that he was a "vile and worthless" sinner, unworthy of the priesthood, and this sense of sin and unworthiness may well have affected his decision to abandon being ordained to the priesthood. Missing diaries At least four complete volumes and around seven pages of text are missing from Dodgson's 13 diaries. The loss of the volumes remains unexplained; the pages have been deliberately removed by an unknown hand. Most scholars assume the diary material was removed by family members in the interests of preserving the family name, but this has not been proven. Except for one page, the period of his diaries from which material is missing is between 1853 and 1863 (when Dodgson was 21–31 years old). This was a period when Dodgson began suffering great mental and spiritual anguish and confessing to an overwhelming sense of his own sin. This was also the period of time when he composed his extensive love poetry, leading to speculation that the poems may have been autobiographical. Many theories have been put forward to explain the missing material. A popular explanation for one particular missing page (27 June 1863) is that it might have been torn out to conceal a proposal of marriage on that day by Dodgson to the 11-year-old Alice Liddell; there has never been any evidence to suggest this was so, and a paper discovered by Karoline Leach in the Dodgson family archive in 1996 offers some evidence to the contrary. This paper, known as the "cut pages in diary document", was compiled by various members of Carroll's family after his death. Part of it may have been written at the time the pages were destroyed, though this is unclear. The document offers a brief summary of two diary pages that are now missing, including the one for 27 June 1863. The summary for this page states that Mrs. Liddell told Dodgson there was gossip circulating about him and the Liddell family's governess, as well as about his relationship with "Ina", presumably Alice's older sister, Lorina Liddell. The "break" with the Liddell family that occurred soon after was presumably in response to this gossip. An alternative interpretation has been made regarding Carroll's rumoured involvement with "Ina": Lorina was also the name of Alice Liddell's mother. What is deemed most crucial and surprising is that the document seems to imply Dodgson's break with the family was not connected with Alice at all. Until a primary source is discovered, the events of 27 June 1863 remain inconclusive. Migraine and epilepsy In his diary for 1880, Dodgson recorded experiencing his first episode of migraine with aura, describing very accurately the process of 'moving fortifications' that are a manifestation of the aura stage of the syndrome. Unfortunately there is no clear evidence to show whether this was his first experience of migraine per se, or if he may have previously suffered the far more common form of migraine without aura, although the latter seems most likely, given the fact that migraine most commonly develops in the teens or early adulthood. Another form of migraine aura, Alice in Wonderland Syndrome, has been named after Dodgson's little heroine, because its manifestation can resemble the sudden size-changes in the book. Also known as micropsia and macropsia, it is a brain condition affecting the way objects are perceived by the mind. For example, an afflicted person may look at a larger object, like a basketball, and perceive it as if it were the size of a golf ball. Some authors have suggested that Dodgson may have suffered from this type of aura, and used it as an inspiration in his work, but there is no evidence that he did. Dodgson also suffered two attacks in which he lost consciousness. He was diagnosed by three different doctors; a Dr. Morshead, Dr. Brooks, and Dr. Stedman, believed the attack and a consequent attack to be an "epileptiform" seizure (initially thought to be fainting, but Brooks changed his mind). Some have concluded from this he was a lifetime sufferer of this condition, but there is no evidence of this in his diaries beyond the diagnosis of the two attacks already mentioned. Some authors, in particular Sadi Ranson, have suggested Carroll may have suffered from temporal lobe epilepsy in which consciousness is not always completely lost, but altered, and in which the symptoms mimic many of the same experiences as Alice in Wonderland. Carroll had at least one incidence in which he suffered full loss of consciousness and awoke with a bloody nose, which he recorded in his diary and noted that the episode left him not feeling himself for "quite sometime afterward". This attack was diagnosed as possibly "epileptiform" and Carroll himself later wrote of his "seizures" in the same diary. Most of the standard diagnostic tests of today were not available in the nineteenth century. Recently, Dr Yvonne Hart, consultant neurologist at the Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, considered Dodgson's symptoms. Her conclusion, quoted in Jenny Woolf's The Mystery of Lewis Carroll, is that Dodgson very likely had migraine, and may have had epilepsy, but she emphasises that she would have considerable doubt about making a diagnosis of epilepsy without further information. Suggestions of paedophilia Stuart Dodgson Collingwood (Dodgson's nephew and biographer) wrote: And now as to the secondary causes which attracted him to children. First, I think children appealed to him because he was pre-eminently a teacher, and he saw in their unspoiled minds the best material for him to work upon. In later years one of his favourite recreations was to lecture at schools on logic; he used to give personal attention to each of his pupils, and one can well imagine with what eager anticipation the children would have looked forward to the visits of a schoolmaster who knew how to make even the dullest subjects interesting and amusing. Despite comments like this, Dodgson's friendships with young girls and psychological readings of his work – especially his photographs of nude or semi-nude girls – have all led to speculation that he was a paedophile. This possibility has underpinned numerous modern interpretations of his life and work, particularly Dennis Potter's play Alice and his screenplay for the motion picture, Dreamchild, Robert Wilson's Alice, and a number of recent biographies, including Michael Bakewell's Lewis Carroll: A Biography (1996), Donald Thomas's Lewis Carroll: A Portrait with Background (1995), and Morton N. Cohen's Lewis Carroll: A Biography (1995). All of these works more or less unequivocally assume that Dodgson was a paedophile, albeit a repressed and celibate one. Cohen claims Dodgson's "sexual energies sought unconventional outlets", and further writes: We cannot know to what extent sexual urges lay behind Charles's preference for drawing and photographing children in the nude. He contended the preference was entirely aesthetic. But given his emotional attachment to children as well as his aesthetic appreciation of their forms, his assertion that his interest was strictly artistic is naïve. He probably felt more than he dared acknowledge, even to himself. Cohen notes that Dodgson "apparently convinced many of his friends that his attachment to the nude female child form was free of any eroticism", but adds that "later generations look beneath the surface" (p. 229). Cohen and other biographers argue that Dodgson may have wanted to marry the 11-year-old Alice Liddell, and that this was the cause of the unexplained "break" with the family in June 1863. There has never been significant evidence to support the idea, however, and the 1996 discovery of the "cut pages in diary document" (see above) seems to make it highly probable that the 1863 "break" had nothing to do with Alice, but was perhaps connected with rumours involving her older sister Lorina (born 11 May 1849, so she would have been 14 at the time), her governess, or her mother who was also nicknamed "Ina". Some writers, e.g., Derek Hudson and Roger Lancelyn Green, stop short of identifying Dodgson as a paedophile, but concur that he had a passion for small female children and next to no interest in the adult world. The basis for Dodgson's interest in female children has been challenged in the last ten years by several writers and scholars (see the 'Carroll Myth' above). Literary works * La Guida di Bragia, a Ballad Opera for the Marionette Theatre (around 1850) * A Tangled Tale * Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865) * Facts * Rhyme? And Reason? (also published as Phantasmagoria) * Pillow Problems * Sylvie and Bruno * Sylvie and Bruno Concluded * The Hunting of the Snark (1876) * Three Sunsets and Other Poems * Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There (includes "Jabberwocky" and "The Walrus and the Carpenter") (1871) * What the Tortoise Said to Achilles Mathematical works * A Syllabus of Plane Algebraic Geometry (1860) * The Fifth Book of Euclid Treated Algebraically (1858 and 1868) * An Elementary Treatise on Determinants, With Their Application to Simultaneous Linear Equations and Algebraic Equations * Euclid and his Modern Rivals (1879), both literary and mathematical in style * Symbolic Logic Part I * Symbolic Logic Part II (published posthumously) * The Alphabet Cipher (1868) * The Game of Logic * Some Popular Fallacies about Vivisection * Curiosa Mathematica I (1888) * Curiosa Mathematica II (1892) * The Theory of Committees and Elections, collected, edited, analysed, and published in 1958, by Duncan Black References Wikipedia - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lewis_Carroll

Sir Philip Sidney (30 November 1554– 17 October 1586) was an English poet, courtier, scholar, and soldier, who is remembered as one of the most prominent figures of the Elizabethan age. His works include Astrophel and Stella, The Defence of Poesy (also known as The Defence of Poetry or An Apology for Poetry), and The Countess of Pembroke’s Arcadia. Early life Born at Penshurst Place, Kent, he was the eldest son of Sir Henry Sidney and Lady Mary Dudley. His mother was the eldest daughter of John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland, and the sister of Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester. His younger brother, Robert was a statesman and patron of the arts, and was created Earl of Leicester in 1618. His younger sister, Mary, married Henry Herbert, 2nd Earl of Pembroke and was a writer, translator and literary patron. Sidney dedicated his longest work, the Arcadia, to her. After her brother’s death, Mary reworked the Arcadia, which became known as The Countess of Pembroke’s Arcadia. Philip was educated at Shrewsbury School and Christ Church, Oxford. Politics and marriage In 1572, in which year he turned 18, he was elected to Parliament as Member of Parliament for Shrewsbury and in the same year travelled to France as part of the embassy to negotiate a marriage between Elizabeth I and the Duc D’Alençon. He spent the next several years in mainland Europe, moving through Germany, Italy, Poland, the Kingdom of Hungary and Austria. On these travels, he met a number of prominent European intellectuals and politicians. Returning to England in 1575, Sidney met Penelope Devereux, the future Lady Rich; though much younger, she would inspire his famous sonnet sequence of the 1580s, Astrophel and Stella. Her father, Walter Devereux, 1st Earl of Essex, is said to have planned to marry his daughter to Sidney, but he died in 1576. In England, Sidney occupied himself with politics and art. He defended his father’s administration of Ireland in a lengthy document. More seriously, he quarrelled with Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, probably because of Sidney’s opposition to the French marriage, which de Vere championed. In the aftermath of this episode, Sidney challenged de Vere to a duel, which Elizabeth forbade. He then wrote a lengthy letter to the Queen detailing the foolishness of the French marriage. Characteristically, Elizabeth bristled at his presumption, and Sidney prudently retired from court. During a 1577 diplomatic visit to Prague, Sidney secretly visited the exiled Jesuit priest Edmund Campion. Sidney had returned to court by the middle of 1581 and in 1584 was MP for Kent. That same year Penelope Devereux was married, apparently against her will, to Lord Rich. Sidney was knighted in 1583. An early arrangement to marry Anne Cecil, daughter of Sir William Cecil and eventual wife of de Vere, had fallen through in 1571. In 1583, he married Frances, teenage daughter of Sir Francis Walsingham. In the same year, he made a visit to Oxford University with Giordano Bruno, who subsequently dedicated two books to Sidney. Literary writings His artistic contacts were more peaceful and more significant for his lasting fame. During his absence from court, he wrote Astrophel and Stella and the first draft of The Arcadia and The Defence of Poesy. Somewhat earlier, he had met Edmund Spenser, who dedicated The Shepheardes Calender to him. Other literary contacts included membership, along with his friends and fellow poets Fulke Greville, Edward Dyer, Edmund Spenser and Gabriel Harvey, of the (possibly fictitious) 'Areopagus’, a humanist endeavour to classicise English verse. Military activity Both through his family heritage and his personal experience (he was in Walsingham’s house in Paris during the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre), Sidney was a keenly militant Protestant. In the 1570s, he had persuaded John Casimir to consider proposals for a united Protestant effort against the Roman Catholic Church and Spain. In the early 1580s, he argued unsuccessfully for an assault on Spain itself. Promoted General of Horse in 1583, his enthusiasm for the Protestant struggle was given a free rein when he was appointed governor of Flushing in the Netherlands in 1585. In the Netherlands, he consistently urged boldness on his superior, his uncle the Earl of Leicester. He conducted a successful raid on Spanish forces near Axel in July, 1586. Injury and death Later that year, he joined Sir John Norris in the Battle of Zutphen, fighting for the Protestant cause against the Spanish. During the battle, he was shot in the thigh and died of gangrene 26 days later, at the age of 31. As he lay dying, Sidney composed a song to be sung by his deathbed. According to the story, while lying wounded he gave his water to another wounded soldier, saying, “Thy necessity is yet greater than mine”. This became possibly the most famous story about Sir Phillip, intended to illustrate his noble and gallant character. It also inspired evolutionary biologist John Maynard Smith to formulate a problem in signalling theory which is known as the Sir Philip Sidney game. Sidney’s body was returned to London and interred in the Old St. Paul’s Cathedral on 16 February 1587. The grave and monument were destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666. A modern monument in the crypt lists him among the important graves lost. Already during his own lifetime, but even more after his death, he had become for many English people the very epitome of a Castiglione courtier: learned and politic, but at the same time generous, brave, and impulsive. The funeral procession was one of the most elaborate ever staged, so much so that his father-in-law, Francis Walsingham, almost went bankrupt. Never more than a marginal figure in the politics of his time, he was memorialised as the flower of English manhood in Edmund Spenser’s Astrophel, one of the greatest English Renaissance elegies. An early biography of Sidney was written by his friend and schoolfellow, Fulke Greville. While Sidney was traditionally depicted as a staunch and unwavering Protestant, recent biographers such as Katherine Duncan-Jones have suggested that his religious loyalties were more ambiguous. Works * The Lady of May– This is one of Sidney’s lesser-known works, a masque written and performed for Queen Elizabeth in 1578 or 1579. * Astrophel and Stella– The first of the famous English sonnet sequences, Astrophel and Stella was probably composed in the early 1580s. The sonnets were well-circulated in manuscript before the first (apparently pirated) edition was printed in 1591; only in 1598 did an authorised edition reach the press. The sequence was a watershed in English Renaissance poetry. In it, Sidney partially nativised the key features of his Italian model, Petrarch: variation of emotion from poem to poem, with the attendant sense of an ongoing, but partly obscure, narrative; the philosophical trappings; the musings on the act of poetic creation itself. His experiments with rhyme scheme were no less notable; they served to free the English sonnet from the strict rhyming requirements of the Italian form. * The Countess of Pembroke’s Arcadia– The Arcadia, by far Sidney’s most ambitious work, was as significant in its own way as his sonnets. The work is a romance that combines pastoral elements with a mood derived from the Hellenistic model of Heliodorus. In the work, that is, a highly idealised version of the shepherd’s life adjoins (not always naturally) with stories of jousts, political treachery, kidnappings, battles, and rapes. As published in the sixteenth century, the narrative follows the Greek model: stories are nested within each other, and different storylines are intertwined. The work enjoyed great popularity for more than a century after its publication. William Shakespeare borrowed from it for the Gloucester subplot of King Lear; parts of it were also dramatised by John Day and James Shirley. According to a widely-told story, King Charles I quoted lines from the book as he mounted the scaffold to be executed; Samuel Richardson named the heroine of his first novel after Sidney’s Pamela. Arcadia exists in two significantly different versions. Sidney wrote an early version (the Old Arcadia) during a stay at Mary Herbert’s house; this version is narrated in a straightforward, sequential manner. Later, Sidney began to revise the work on a more ambitious plan, with much more backstory about the princes, and a much more complicated story line, with many more characters. He completed most of the first three books, but the project was unfinished at the time of his death—the third book breaks off in the middle of a sword fight. There were several early editions of the book. Fulke Greville published the revised version alone, in 1590. The Countess of Pembroke, Sidney’s sister, published a version in 1593, which pasted the last two books of the first version onto the first three books of the revision. In the 1621 version, Sir William Alexander provided a bridge to bring the two stories back into agreement. It was known in this cobbled-together fashion until the discovery, in the early twentieth century, of the earlier version. * An Apology for Poetry (also known as A Defence of Poesie and The Defence of Poetry)– Sidney wrote the Defence before 1583. It is generally believed that he was at least partly motivated by Stephen Gosson, a former playwright who dedicated his attack on the English stage, The School of Abuse, to Sidney in 1579, but Sidney primarily addresses more general objections to poetry, such as those of Plato. In his essay, Sidney integrates a number of classical and Italian precepts on fiction. The essence of his defence is that poetry, by combining the liveliness of history with the ethical focus of philosophy, is more effective than either history or philosophy in rousing its readers to virtue. The work also offers important comments on Edmund Spenser and the Elizabethan stage. * The Sidney Psalms– These English translations of the Psalms were completed in 1599 by Philip Sidney’s sister Mary. In popular culture * A memorial, erected in 1986 at the location where he was mortally wounded by the Spanish, can be found at the entrance of a footpath (" 't Gallee") located in front of the petrol station at the Warnsveldseweg 170. * In Arnhem, in front of the house in the Bakkerstraat 68, an inscription on the ground reads: "IN THIS HOUSE DIED ON THE 17 OCTOBER 1586 * SIR PHILIP SIDNEY * ENGLISH POET, DIPLOMAT AND SOLDIER, FROM HIS WOUNDS SUFFERED AT THE BATTLE OF ZUTPHEN. HE GAVE HIS LIFE FOR OUR FREEDOM". The inscription was unveiled on 17 October 2011, exactly 425 years after his death, in the presence of Philip Sidney, Viscount De L’Isle, a descendant of the brother of Philip Sidney. * The city of Sidney, Ohio, in the United States and a street in Zutphen, Netherlands, have been named after Sir Philip. A statue of him can be found in the park at the Coehoornsingel where, in the harsh winter of 1795, English and Hanoverian soldiers were buried who had died while retreating from advancing French troops. * Another statue of Sidney, by Arthur George Walker, forms the centrepiece of Shrewsbury School’s war memorial to alumni who died serving in World War I (unveiled 1924). * Sidney features as a friend of Giordano Bruno and an agent for Sir Francis Walsingham in the historical crime novels of S J Parris. * W. B. Yeats appears to allude to Sidney as a model of the ideal man in his poem “In Memory of Major Robert Gregory” when he calls Robert Gregory “Our Sidney and our perfect man”. * Sidney is referenced in the T.S. Eliot’s poem “A Cooking Egg”, published in his 1920 poetry collection Aras Vos Prec, where Eliot expresses a desire to speak with Sir Philip in heaven. * An extended sketch from Monty Python’s Flying Circus (Series 3, Episode 10 “E. Henry Thripshaw’s Disease”) featured a police officer, disguised as Sir Philip Sidney, finding himself transported to the Tudor era after raiding a pornography shop. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philip_Sidney

William Arthur Dunkerley (12 November 1852 – 23 January 1941) was an English journalist, novelist and poet. He was born in Manchester, spent a short time after his marriage in the US before moving to Ealing, West London, where he served as deacon and teacher at the Ealing Congregational Church from the 1880s. In 1922 he moved to Worthing in Sussex, where he became the town’s mayor.Dunkerley wrote under his own name, and also as John Oxenham for his poetry, hymn-writing, and novels. His poetry includes Bees in Amber: A Little Book of Thoughtful Verse (1913), which became a bestseller. He also wrote the poem “Greatheart”. He used the pseudonym Julian Ross for journalism. In February 1892 Robert Barr and Dunkerley founded The Idler, a monthly “general interest magazine, one of the first to appear following the enthusiastic reception of The Strand, but not a slavish imitation”. Barr and Dunkerley/Oxenham both contributed as writers. The editors were Barr and Jerome K. Jerome initially.Dunkerley had two sons and four daughters, of whom the eldest, and eldest child, Elsie Jeanette, became well known as a children’s writer, particularly through her Abbey Series of girls’ school stories. Another daughter, Erica, also used the Oxenham pen-name. The elder son, Roderic Dunkerley, had several titles published under his own name. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Arthur_Dunkerley

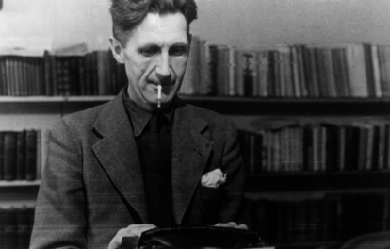

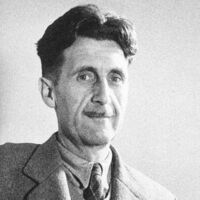

Eric Arthur Blair (25 June 1903 – 21 January 1950), better known by his pen name George Orwell, was an English novelist and journalist. His work is marked by clarity, intelligence and wit, awareness of social injustice, opposition to totalitarianism, and belief in democratic socialism. Considered perhaps the 20th century's best chronicler of English culture, Orwell wrote literary criticism, poetry, fiction and polemical journalism. He is best known for the dystopian novel Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) and the allegorical novella Animal Farm (1945), which together have sold more copies than any two books by any other 20th-century author. His book Homage to Catalonia (1938), an account of his experiences in the Spanish Civil War, is widely acclaimed, as are his numerous essays on politics, literature, language and culture. In 2008, The Times ranked him second on a list of "The 50 greatest British writers since 1945”.