Info

Paisaje de verano con vacas.

Hjalmar Munsterhjelm

?

Private collection

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (12 May 1828 – 9 April 1882) was an English poet, illustrator, painter and translator. He founded the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in 1848 with William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais, and was later to be the main inspiration for a second generation of artists and writers influenced by the movement, most notably William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones. His work also influenced the European Symbolists and was a major precursor of the Aesthetic movement.

English Romantic poet John Keats was born on October 31, 1795, in London. The oldest of four children, he lost both his parents at a young age. His father, a livery-stable keeper, died when Keats was eight; his mother died of tuberculosis six years later. After his mother's death, Keats's maternal grandmother appointed two London merchants, Richard Abbey and John Rowland Sandell, as guardians. Abbey, a prosperous tea broker, assumed the bulk of this responsibility, while Sandell played only a minor role. When Keats was fifteen, Abbey withdrew him from the Clarke School, Enfield, to apprentice with an apothecary-surgeon and study medicine in a London hospital. In 1816 Keats became a licensed apothecary, but he never practiced his profession, deciding instead to write poetry.

Charles Baudelaire est un poète français. Né à Paris le 9 avril 1821, il meurt dans la même ville le 31 août 1867. Baudelaire naît le 9 avril 1821 au 13 rue Hautefeuille à Paris. Sa mère, Caroline Dufaÿs, a vingt-sept ans. Son père, Joseph-François Baudelaire, né en 1759 à La Neuville-au-Pont, en Champagne, est alors sexagénaire. Quand il meurt en 1827, Charles n’a que six ans. Cet homme lettré, épris des idéaux des Lumières et amateur de peinture, peintre lui-même, laisse à Charles un héritage dont il n’aura jamais le total usufruit. Il avait épousé en premières noces, le 7 mai 1797, Jeanne Justine Rosalie Janin, avec laquelle il avait eu un fils, Claude Alphonse Baudelaire, demi-frère de Charles. « Dante d’une époque déchue » selon le mot de Barbey d’Aurevilly, « tourné vers le classicisme, nourri de romantisme », à la croisée entre le Parnasse et le symbolisme, chantre de la « modernité », il occupe une place considérable parmi les poètes français pour un recueil certes bref au regard de l’œuvre de son contemporain Victor Hugo (Baudelaire s’ouvrit à son éditeur de sa crainte que son volume ne ressemblât trop à une plaquette…), mais qu’il aura façonné sa vie durant : Les Fleurs du mal.

Edward Estlin Cummings (October 14, 1894 – September 3, 1962), popularly known as E. E. Cummings, with the abbreviated form of his name often written by others in lowercase letters as e.e. cummings (in the style of some of his poems—see name and capitalization, below), was an American poet, painter, essayist, author, and playwright. His body of work encompasses approximately 2,900 poems, two autobiographical novels, four plays and several essays, as well as numerous drawings and paintings. He is remembered as a preeminent voice of 20th century poetry.

Robert Herrick (baptized 24 August 1591 – buried 15 October 1674) was a 17th-century English poet. Born in Cheapside, London, he was the seventh child and fourth son of Julia Stone and Nicholas Herrick, a prosperous goldsmith. His father died in a fall from a fourth-floor window in November 1592, when Robert was a year old (whether this was suicide remains unclear). The tradition that Herrick received his education at Westminster is groundless. It is more likely that (like his uncle's children) he attended The Merchant Taylors' School. In 1607 he became apprenticed to his uncle, Sir William Herrick, who was a goldsmith and jeweler to the king. The apprenticeship ended after only six years when Herrick, at age twenty-two, matriculated at St John's College, Cambridge. He graduated in 1617. Robert Herrick became a member of the Sons of Ben, a group centered upon an admiration for the works of Ben Jonson. Herrick wrote at least five poems to Jonson. Herrick took holy orders in 1623, and in 1629 he became vicar of Dean Prior in Devonshire. In 1647, in the wake of the English Civil War, Herrick was ejected from his vicarage for refusing the Solemn League and Covenant. He then returned to London, living in Westminster and depending on the charity of his friends and family. He spent some time preparing his lyric poems for publication, and had them printed in 1648 under the title Hesperides; or the Works both Human and Divine of Robert Herrick, with a dedication to the Prince of Wales. When King Charles II was restored to the throne in 1660, Herrick petitioned for his own restoration to his living. Perhaps King Charles felt kindly towards this genial man, who had written verses celebrating the births of both Charles II and his brother James before the Civil War. Herrick became the vicar of Dean Prior again in the summer of 1662 and lived there until his death in October 1674, at the ripe age of 83. His date of death is not known, but he was buried on 15 October. Herrick was a bachelor all his life, and many of the women he names in his poems are thought to be fictional. Poetic style and stature Herrick wrote over 2,500 poems, about half of which appear in his major work, Hesperides. Hesperides also includes the much shorter Noble Numbers, his first book, of spiritual works, first published in 1647. He is well-known for his style and, in his earlier works, frequent references to lovemaking and the female body. His later poetry was more of a spiritual and philosophical nature. Among his most famous short poetical sayings are the unique monometers, such as "Thus I / Pass by / And die,/ As one / Unknown / And gone." Herrick sets out his subject-matter in the poem he printed at the beginning of his collection, The Argument of his Book. He dealt with English country life and its seasons, village customs, complimentary poems to various ladies and his friends, themes taken from classical writings and a solid bedrock of Christian faith, not intellectualized but underpinning the rest. Herrick never married, and none of his love-poems seem to connect directly with any one beloved woman. He loved the richness of sensuality and the variety of life, and this is shown vividly in such poems as Cherry-ripe, Delight in Disorder and Upon Julia’s Clothes. The over-riding message of Herrick’s work is that life is short, the world is beautiful, love is splendid, and we must use the short time we have to make the most of it. This message can be seen clearly in To the Virgins, to make much of Time, To Daffodils, To Blossoms and Corinna going a-Maying, where the warmth and exuberance of what seems to have been a kindly and jovial personality comes over strongly. The opening stanza in one of his more famous poems, "To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time", is as follows: Gather ye rosebuds while ye may, Old Time is still a-flying; And this same flower that smiles today, Tomorrow will be dying. This poem is an example of the carpe diem genre; the popularity of Herrick's poems of this kind helped revive the genre. His poems were not widely popular at the time they were published. His style was strongly influenced by Ben Jonson, by the classical Roman writers, and by the poems of the late Elizabethan era. This must have seemed quite old-fashioned to an audience whose tastes were tuned to the complexities of the metaphysical poets such as John Donne and Andrew Marvell. His works were rediscovered in the early nineteenth century, and have been regularly printed ever since. The Victorian poet Swinburne described Herrick as the greatest song writer...ever born of English race. It is certainly true that despite his use of classical allusions and names, his poems are easier for modern readers to understand than those of many of his contemporaries. Robert Herrick is a major character in Rose Macaulay's 1932 historical novel, They Were Defeated. References Wikipedia - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Herrick_(poet)

Gustavo Adolfo Domínguez Bastida (Sevilla, 17 de febrero de 1836 – Madrid, 22 de diciembre de 1870), más conocido como Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer, fue un poeta y narrador español, perteneciente al movimiento del Romanticismo, aunque escribió en una etapa literaria perteneciente al Realismo. Por ser un romántico tardío, ha sido asociado igualmente con el movimiento posromántico. Aunque, mientras vivió, fue moderadamente conocido, sólo comenzó a ganar verdadero prestigio cuando, tras su muerte, fueron publicadas muchas de sus obras. Nació en Sevilla el 17 de febrero de 1836, hijo del pintor José Domínguez Insausti, que firmaba sus cuadros con el apellido de sus antepasados como José Domínguez Bécquer. Sus más conocidos trabajos son sus Rimas y Leyendas. Los poemas e historias incluidos en esta colección son esenciales para el estudio de la Literatura hispana, siendo ampliamente reconocidos por su influencia posterior. Gustavo Adolfo por Mercedes de Velilla En la margen del Betis murmurante, donde expira, entre flores, la onda inquieta, en monumento digno del poeta, su hermosa estatua se alzará triunfante. El sol le ofrecerá nimbo radiante; sus perfumes, la rosa y la violeta; la aurora, el beso de su luz discreta; el crepúsculo, brisa refrescante. Traerá la noche espíritus y hadas, visiones de Leyendas peregrinas que poblarán las verdes enramadas. La alondra y las obscuras golondrinas cantarán, al lucir las alboradas, las Rimas inmortales y divinas.

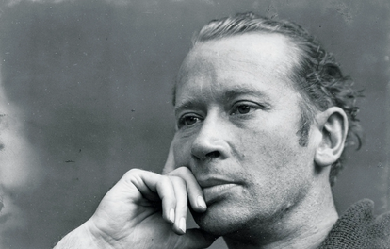

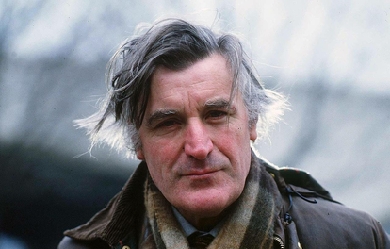

Edward James (Ted) Hughes was born in Mytholmroyd, in the West Riding district of Yorkshire, on August 17, 1930. His childhood was quiet and dominately rural. When he was seven years old, his family moved to the small town of Mexborough in South Yorkshire, and the landscape of the moors of that area informed his poetry throughout his life. Hughes graduated from Cambridge in 1954. A few years later, in 1956, he co-founded the literary magazine St. Botolph’s Review with a handful of other editors. At the launch party for the magazine, he met Sylvia Plath. A few short months later, on June 16, 1956, they were married.

Rosario Castellanos Figueroa (Ciudad de México, 25 de mayo de 1925 - Tel Aviv, 7 de agosto de 1974) fue una escritora, periodista y diplomática mexicana, considerada una de las literatas mexicanas más importantes del siglo XX. ...si es necesaria una definición para el papel de identidad, apunte que soy una mujer de buenas intenciones y que he pavimentado un camino directo y fácil al infierno. –Rosario Castellanos

Joseph Skipsey (1832– 1903) was a Northumberland born poet and songwriter in the middle and late 19th century. His best known work is arguably “The Hartley Calamity” about the Hartley Colliery Disaster, a devastating mining accident in Hartley, Northumberland, England in 1862 in which 204 lives were lost. He was known as “The Pitman Poet”.

Robert Browning was born on May 7, 1812, in Camberwell, England. His mother was an accomplished pianist and a devout evangelical Christian. His father, who worked as a bank clerk, was also an artist, scholar, antiquarian, and collector of books and pictures. His rare book collection of more than 6,000 volumes included works in Greek, Hebrew, Latin, French, Italian, and Spanish. Much of Browning's education came from his well-read father. It is believed that he was already proficient at reading and writing by the age of five. A bright and anxious student, Browning learned Latin, Greek, and French by the time he was fourteen. From fourteen to sixteen he was educated at home, attended to by various tutors in music, drawing, dancing, and horsemanship.

Alfonsina Storni Martignoni (Sala Capriasca, Suiza, 29 de mayo de 1892 – Mar del Plata, Argentina, 25 de octubre de 1938) fue una poetisa y escritora argentina del modernismo. Su prosa es feminista y, según la crítica, posee una originalidad que cambió el sentido de las letras de Latinoamérica. En su poesía deja de lado el erotismo y aborda el tema desde un punto de vista más abstracto y reflexivo. Sus composiciones reflejan, además, la enfermedad que padeció durante gran parte de su vida y muestran la espera del punto final de su vida, expresándolo mediante el dolor, el miedo y otros sentimientos desmotivacionales.

Juana Inés de Asbaje y Ramírez de Santillana, más conocida como Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, (San Miguel Nepantla, 12 de noviembre de 1651—Ciudad de México, 17 de abril de 1695) fue una religiosa y escritora novohispana del Barroco en el Siglo de Oro. Cultivó la lírica, el auto sacramental y el teatro, así como la prosa. Por la importancia de su obra, recibió los sobrenombres de «el fénix de América», «la Décima Musa» o «la Décima Musa mexicana». A muy temprana edad aprendió a leer y a escribir. Perteneció a la corte de Antonio de Toledo y Salazar, marqués de Mancera y 25° virrey novohispano. En 1667 ingresó a la vida religiosa a fin de consagrarse por completo a la literatura. Sus más importantes mecenas fueron los marqueses de la Laguna, virreyes de la Nueva España, quienes publicaron sus obras en la España peninsular. Murió a causa de una epidemia el 17 de abril de 1695.

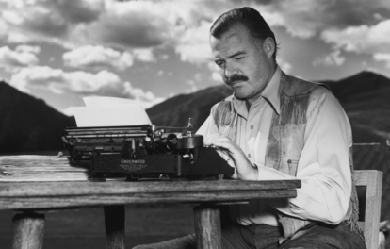

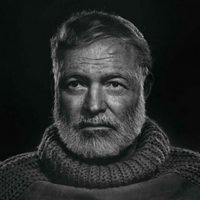

Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961) was one of the most significant American authors of the Twentieth century . His novels and short fictions have left an indelible mark on the literary production of the United States and the world. Although most often remembered for his economical and understated fiction, he was also a noted journalist. In 1954, Ernest Hemingway was awarded the Novel Prize in Literature. Hemingway is also known for his heroic, adventurous and often stereotypically “manly” public persona. The myth he cultivated of himself as a man of action aided the important Modernist reading of many of his works.

Celia Laighton Thaxter (June 29, 1835 – August 25, 1894) was an American writer of poetry and stories. She was born in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Thaxter grew up in the Isles of Shoals, first on White Island, where her father, Thomas Laighton, was a lighthouse keeper, and then on Smuttynose and Appledore Islands. When she was sixteen, she married Levi Thaxter and moved to the mainland, residing first in Watertown, Massachusetts at a property his father owned. Celia died suddenly while on Appledore Island. She was buried not far from her cottage, which unfortunately burned in the 1914 fire that destroyed The Appledore House hotel.

William Carlos Williams (September 17, 1883 – March 4, 1963) was an American poet closely associated with modernism and Imagism. He was also a pediatrician and general practitioner of medicine with a medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine. Williams "worked harder at being a writer than he did at being a physician" but excelled at both. Although his primary occupation was as a family doctor, Williams had a successful literary career as a poet. In addition to poetry (his main literary focus), he occasionally wrote short stories, plays, novels, essays, and translations. He practiced medicine by day and wrote at night. Early in his career, he briefly became involved in the Imagist movement through his friendships with Ezra Pound and H.D. (also known as Hilda Doolittle, another well-known poet whom he befriended while attending the University of Pennsylvania), but soon he began to develop opinions that differed from those of his poet/friends.

Carilda Oliver Labra. Poetisa cubana, Premio Nacional de Literatura (1998), nacida el 6 de julio de 1922 en la occidental provincia de Matanzas, específicamente en la capital provincial, ciudad en la que siempre ha vivido. Graduada de Derecho en la Universidad de La Habana en 1945, profesión que ha ejercido en su ciudad natal junto a su pasión por la poesía. Carilda Oliver: “He sido muy feliz siendo poeta” En el programa "Con 2 que se quieran”, 4 enero 2011. Amaury Pérez: Muy buenas noches, estamos en Con 2 que se quieran, ahora aquí en 5ta. Avenida y calle 32, en el barrio de Miramar, en los maravillosos Estudios Abdala. Una noche verdaderamente especial. Durante todos estos programas que han transcurrido hasta este momento, ustedes la pidieron, ustedes la solicitaron mediante sus correos, mediante sus cartas. Es la persona que más han solicitado. Yo lo he ido apuntando y así es y aquí está. Los ojos más bellos de la literatura cubana: una mujer extraordinariamente hermosa, una escritora de excelencia. Para cualquiera es emotivo presentarla, tenerla delante. Una mujer que irradia dulzura y ternura, la eminente poetisa cubana, matancera Carilda Oliver Labra. Señora, un beso, otro beso. Muchas gracias, yo estoy abrumado por su presencia, usted ha venido de Matanzas a estar aquí con nosotros y yo no puedo menos que rendirme a sus pies y agradecérselo. Y empezaremos nuestra conversación, más que una entrevista. Usted es Premio Nacional de Literatura. La pregunta sería. ¿Llegó a tiempo el Premio Nacional de Literatura? Carilda. Claro que te voy contestar y te voy a tratar de tú. Aunque no hemos tenido mucha oportunidad de vernos personalmente, pero te he visto en escena, en televisión, y en sueños… Amaury. Ay, Dios mío… Carilda. Primero, tengo que agradecerte la invitación. Amaury. Gracias, muchas gracias. Carilda. Después, todas esas cosas lindísimas que has dicho y en el transcurso del programa creo que se podrá ir haciendo presente esa admiración que es mutua. Amaury. Ah, muchas gracias. Carilda. Y que hoy para que no parezca esto una asociación de bombos recíprocos no te puedo hablar de tu música ni de tus interpretaciones. Yo creo que tú eres un poeta, lo de músico, ¡figúrate!, pero bueno, vamos a pasar a responder tu pregunta. Que si llegó, si tomó mucho tiempo… eso, en cierto modo, pues no es descorazonador, diríamos, no, no me angustió. Fui candidata 9 veces, o sea, 9 años seguidos, al Premio Nacional de Literatura que es, como todo el mundo sabe, el premio más importante en la carrera de un escritor. Fueron escogiendo los mejores escritores de Cuba, no puedo decir otra cosa, pero bueno, mi turno no llegaba y yo pensaba: bueno, es que yo no soy tan buena, yo no soy tan buena. Además, yo había tenido mis problemas, había estado fuera de las editoriales mucho tiempo, y decía: esto puede ser que influencie, era un tribunal, parece que compasivo, digo yo, también, a lo mejor no era tan justo, pero dirían: esta pobre mujer lleva 9 años esperando seguramente. No, yo ya no esperaba. Amaury. ¿No esperaba nada? Carilda. Cuando me lo dieron, que me llamaron por teléfono para decírmelo. Dije: Esto es una broma, esto es una broma. ¡Pero era verdad! Amaury. ¡Pero era verdad!, ¿y lo disfrutó? Carilda. ¡Ay, cómo no! Lo disfruté muchísimo, lo estoy disfrutando todavía. Sí, sí, porque eso, claro, es un compromiso, es un compromiso histórico y algo que nos obliga a tratar de ser mejores y ya va siendo imposible porque la vida…, con sus añitos… es posible que nos esté haciendo daño. Desde luego, nosotros no nos damos cuenta. Esto es una coquetería, esto es una coquetería. Amaury. Téngala conmigo porque la está teniendo con los televidentes nada más. La veo que mira para la cámara y para la cámara, tiene que hablarme a mí, porque me estoy poniendo celoso. Carilda. Yo coqueteo con los televidentes… (risas) Amaury. (risas) Yo estoy celoso, me estoy poniendo celoso de la cámara. Carilda. No esté celoso, porque más celoso estará mi marido. (risas) Amaury. Ah, sí, seguramente. (risas) Carilda. Y ten cuidado no se cele de ti porque es karateca. (risas) Amaury. ¡No. no, no! Además él sabe que usted es un amor antiguo mío, pero somos amigos, usted lo sabe, Raydel y yo somos amigos, así que no se va a poner celoso conmigo. Ahora, ¿Usted escogió el camino de la poesía, Carilda, o la poesía la escogió a usted? Carilda. Bueno, yo creo que sería presumir mucho por parte mía si digo que yo fui escogida por la poesía. Es presumir mucho. Lo que pasa que de ella no me he podido escapar. He sido muy feliz siendo poeta. No hubiera querido ser nada más. Amo mucho la música, la plástica. He intentado y hasta me he graduado de pintura, pero realmente… el ballet, bueno, el teatro, todas las artes, pero, sinceramente, nací poeta. Y quiero decirlo, porque cuando yo tenía tres o cuatro años, que mi mamá me cantaba canciones, ella me contó mucho tiempo después, que yo le modificaba las canciones. Amaury. ¿Ah, sí? Carilda. La letra. Amaury. La letra, claro. Carilda. Entonces ella dijo: esta niña va a ser poeta y parece que resultó. Claro, la poesía es muy difícil y me parece a mí, que aparte del don que se pueda traer, hay que estudiar y tiene mucho que ver con la técnica y con la inspiración. Amaury. Ahí vamos, porque hay gente que dice que no hace falta… que la inspiración no existe. Carilda. ¡Pero imagínate!, si no existiera la inspiración, si fuera una cosa de aprender lo que es un endecasílabo, lo que es una cesura, lo que es un hemistiquio, lo que es un soneto, lo que es un verso libre, pues sería, vaya, un objetivo de cualquier persona. Amaury. Cualquier persona se aprende la técnica y ya es poeta. Carilda. Claro y yo creo que…, claro, se pueden hacer versos, pero una cosa es un verso y otra cosa es la poesía, ¿eh?. El verso es la línea, el fondo, la forma, diría, la forma. Pero tú puedes aprender…, bueno, vamos a hacer octosílabos. Me voy a leer a Martí, que era magnífico poeta y que además en los octosílabos, sí, era un príncipe y ya, voy cogiendo esa música, que la rima y el ritmo, pero si se te fue la chispa, que es el fuego, es más que el fuego, la luz del verso, no puedes hacer poesía. Bueno, no es una lección, es una idea muy humilde. Amaury. Bueno, es humilde pero está viniendo de Carilda Oliver. No me lo está diciendo cualquiera. Carilda. Además, no creo que sea una idea mía, yo creo que todos los que escribimos sabemos. Hay veces que uno hace cosas que rompen. Que las miras después y en todo…, uno puede escribir un poema breve de cinco o seis o siete versos y tener un solo verso, y si merece la pena lo dejamos porque es imposible que, por ejemplo, en un soneto, los catorce versos sean buenos. Ahora, me preguntaba Gabriela Mistral. ¡Ay, bueno, es una anécdota…! Perdóname que te la haga. Amaury. No, ¡pero qué bueno que me la hace! Por favor. Carilda. Bueno, el día que tuve la dicha de conocerla, porque fue tan generosa Dulce María Loynaz, nuestra enorme, inmensa, inolvidable Dulce María, que me invitó a su casa, la primera vez que fui, porque estaba allí Gabriela. Y entonces Gabriela, después que leyó unos sonetos míos, me dice: con una modestia, que es digna de mencionar. No por lo que entraña el elogio que me hizo, sino por la forma en que ella asumió el conocimiento de una muchacha, como ella llamaba “del campo”, una niña del campo, porque yo era matancera y Dulce María era capitalina y además una mujer que había viajado y yo no había salido de Tirry 81 (calle y número de la casa de Carilda en Matanzas). Amaury. De Calzada de Tirry 81. Carilda. Fue después que he viajado y he tenido otras oportunidades, pero bueno, Tirry 81, para mí, es el planeta. Entonces, ¿qué pasa?, que ella me dice: ¿Y cómo cierra tan bien los sonetos? porque en el último verso a mí siempre se me va la fuerza, palabra textuales de Gabriela, y luego paso mucho trabajo y a fin de cuentas lo dejo así, ¿pero cómo tú lo cierras tan bien? y entonces yo le dije: A mí, casi siempre, los sonetos me suceden en los momentos menos oportunos. Estoy sentada en el cine viendo una película, y me viene un solo verso y me levanto y voy para mi casa a escribir, porque después se me olvida. Es así, eso va en aumento, porque la inspiración es como que se consolida en determinado momento, ya es como una efervescencia, como una llama que crece, que crece y que luego no se vuelve humo, sino se vuelve luz. Y ese verso de la luz, a veces, aparece en el segundo terceto, en el último, o aparece en el primer cuarteto, en cualquier parte, pero uno tiene que darse cuenta y dice: este es el final y lo pone al final y después empieza la rima de abajo para arriba. Amaury. Nunca había oído que nadie empezara un soneto de abajo para arriba. Carilda. Sí, pero eso es una técnica, que yo no sé si yo la descubrí, yo creo que no, pero es un recurso, es un apoyo, y ahí está el soneto a mi madre. Búscalo. Amaury. ¡A claro, claro! Aquí, este soneto, por ejemplo. (Amaury le acerca el soneto Madre mía que estás en una carta, escrito por Carilda) Carilda. No lo vamos a leer todo completo. Amaury. ¡Léalo completo!. Carilda. Ah, ¿completo? Amaury. Completo. Carilda. Y entonces ustedes verán que el último verso, que no lo voy a decir ahora, es realmente el cierre, pero es que ese fue el primero que yo escribí y no lo puse arriba porque echaba a perder el soneto. Amaury. ¡Qué bárbaro! Carilda. ¿Comprende? él se llama: “Madre mía que estás en una carta”. Madre mía que estás en una carta Y en un regaño antiguo que no encuentro. Quédate para siempre aquí en el centro de la rosa total que no se aparta. Madre mía que estás tan lejos Harta de la nieve y la bruma, Espera que entro a ponerte a vivir con el sol dentro Madre mía que estás en una carta. Puedes darle al misterio alguna cita, Convenir con las sombras hechiceras. Puede ser una piedra que se quita O secarte ahora mismo las ojeras, pero acuérdate madre de tu hijita, ¡No te atrevas a todo, no te mueras! Amaury. ¡Madre santa, es que eso es un poema! ¿Cuán duro fue, ya que me leyó esto, el exilio de sus padres, para usted, que decidió quedarse? Carilda. Bueno, imagínate si fue duro el exilio, que yo los acompañé al aeropuerto y en el momento que el avión despegó, yo me quedé sin habla y sin oír. Y recuperé el habla a las pocas horas y todavía me falta por recuperar, que ya es imposible, de eso hace muchos años, el oído derecho. Yo oigo solo de este oído, del izquierdo, que lo recuperé después, de la impresión. Eso fue muy duro, pero la decisión la tomé sin dame cuenta. Desde que empezaron con el asunto de los pasaportes y tengo que significar que ninguno de los dos era desafecto a la Revolución. Pero se iban en pos de hijos y en pos de nietos. Amaury. Claro. Carilda. Mi papá era abogado y quería sacarme el pasaporte como para embullarme, pero sin decírmelo, siempre me respetaron mucho mi opinión, ni siquiera hicieron presión. Y, era muy triste, porque imagínese, ellos se iban…, aparte del amor, de la compañía, yo estaba en aquel momento sola, no tenía a nadie. Pero yo soy una palma que nací aquí y aquí tengo la raíz y no me podía, de ningún modo cortar las raíces, me quedé, eso fue todo. Amaury. Bueno, ya no sé ni cómo hacer las preguntas. La gente tiene una imagen, la imagen que se quiere crear de Carilda. Pero evidentemente hay una Carilda imaginada y hay una Carilda real. Hay una oculta, la que habita en Tirry 81, la que tiene una familia, la que tiene hace veinte años un compañero, un matrimonio, su esposo. Y hay una que es la que la gente quiere fantasear, que es la que acusan de… los términos son feos, pero la Carilda que dicen que es libertina (Carilda ríe), que cuando uno se pone a buscar los sinónimos de libertina… Y yo, yo puedo dar fe en televisión de que usted es una dama, de que usted es una señora. Carilda. Gracias, gracias. Bueno, eso es hasta simpático, no me ha traumatizado, aunque desde luego, en cierto modo ha tergiversado la personalidad literaria de uno. A mí no me afecta desde el punto de vista personal. A mí…, Carilda, es así, es asao… generalmente los artistas arrastramos una serie de comentarios, que son muy convenientes porque así hablan de nosotros, buscan las poesías, y se venden los libros y entonces uno puede hacer una carrera, pudiéramos decir, vamos a llamarle así a esto de ser poeta, que no es ninguna carrera. Ser poeta es una cosa muy difícil, cuando uno, bueno, quiere serlo de verdad. Entonces ¿qué pasa?, que yo, figúrate, muy jovencita escribí el tal “Me desordeno…” y la gente siguió desordenándose por su cuenta (risas), pero me han echado la culpa a mí de todo. La cantidad de hombres que me han dicho a mí y de mujeres: Ay, le agradezco su Me desordeno, porque con esa poesía yo he enamorado y he hecho, y qué sé yo. Y a mí me da risa, porque esa poesía es hasta inocente, es inocente incluso esa parte que dice: “Cuando quiero besarte arrodillada“, esa parte, la gente le da unas explicaciones… que bueno, no lo voy a decir aquí porque estamos en la televisión (risas), pero los televidentes ya saben de lo que estoy hablando. Entonces…, me van a tachar todo esto… (risas) Amaury. (risas) No le vamos a tachar nada. Carilda. ¿Qué dirá el ICRT? (risas) Amaury. No, no, nada, el ICRT es muy comprensivo con este programa. (risas) Carilda. Ay, perdónenme, pero yo, bueno, soy un poco irreverente, pero buena muchacha. (risas) Lo de muchacha es peor que lo de irreverente (risas). Amaury. (risas) ¡Señora, señora, señora! Carilda. Bueno, chico, pero me estoy divirtiendo un poco. (risas) Amaury. Claro que sí, diviértase. Carilda. En estos programas hay que reírse también. Amaury. Claro, no se puede ser tan grave… Carilda. A veces tenemos que llorar por cosas…, que tampoco debiéramos llorar… Amaury. No, pero si yo lo que la quiero es ver divertida. ¿Cómo llorando? No, yo no quiero verla llorando. Carilda. Estoy divertida, pero es culpa tuya, porque yo no sé qué vueltas me has dado, que mira dónde me has puesto (risas), porque yo no iba a venir a ningún programa. Bueno, entonces me atreví a celebrar las piernas de los hombres, de un hombre. Amaury. De uno, claro, no de los hombres. Carilda. En uno están todos los demás. Entonces la boca, los ojos, vaya, decirles piropos a los hombres. Porque siempre eran a las mujeres y bueno, pues yo rompí con eso, porque yo no veo nada en eso de extraordinario, ni de cosas subversivas, irreverentes, que estoy faltando el respeto, porque piensan que estoy hablando de una cosa carnal. Y el amor es espiritual y carnal y tiene que integrarse de las dos cosas, porque si no realmente no responde a la verdadera esencia del amor. Y bueno, todas esas cosas empezaron a traerme, aparte de algunas cosas de la vida de uno, que se han ido deformando y se han exagerado cosas y pasiones. Han inventado cosas con Hemingway, que no pasó nada en lo absoluto, ese era un hombre muy caballeroso, que me dio un elogio, un piropo delante de periodistas y eso empezó a dar vueltas, es un ejemplo que pongo. Y bueno, a cada rato pues a la gente le ha parecido muy natural que yo tenga romances de acuerdo con los versos que he escrito y esos versos están escritos para mis esposos, para las personas que yo he amado y que me han amado. Mi vida ¡figúrate!, en la Ciudad de Matanzas, que es una ciudad como todo el mundo sabe, como todas las provincias de Cuba. Yo allí salía sola con mi novio, cosa que la gente no hacía, mi familia me lo permitía. Estoy hablando de los años 50. Mi primer matrimonio data del 52. Íbamos a sentarnos en el parque…, allí lo más que hacíamos era cogernos las manos. El primer noviazgo mío eran dos días a la semana por la noche, dos horas, y mi mamá sentada cerca, que uno no se podía dar ni un beso porque, ¡imagínate!, ella, cuando ya el novio se iba, se paraba a la mitad del zaguán y ya. Esas cosas de la época…, que ahora los jóvenes disfrutan de otra libertad que ¡bienvenida sea!, porque creo que todo aquello era… Mi mamá era de una educación española. Mis abuelos eran españoles, por parte de madre, pero siempre mi madre, a pesar de haberse educado en aquel sitio, me respetaba, me veía como…, ella decía que no se podía interferir en la vida de los hijos hasta el extremo de querer dirigirlos en todo, que había que dejarles que respiraran el aire de la libertad, que ella no lo había tenido de niña, que siempre estaba con la religión a cuestas. Y, fíjate que todo eso no juega con que después yo escribiera determinados versos, pero a lo mejor era aquel hálito que había en mi casa de respeto lo que me hizo soltarme como un pájaro y volar. Amaury. Y no como un papalote donde hay una cuerda. Porque el papalote parece que está libre, pero hay una cuerda que lo ata. Carilda. Exacto, perfecta la imagen, perfecta la imagen. No sé si te contesté. Amaury. Sí, claro que me contestó. No, me contestó, y de más, qué maravilla. Carilda. Me he casado tres veces. Estuve muchos años sin compañía. Luego llegó un muchacho joven a mi vida, demasiado joven. Toda la ciudad se escandalizó y yo diría que toda Cuba, cuando él empezó a visitarme. Él estuvo como dos años detrás de mí y yo me acuerdo que el primer día que lo vi, lo vi a través de la mirilla de la puerta. Esto no viene al caso, pero bueno. (risas) Amaury. ¡No, cómo no!, sí viene al caso, claro, porque yo voy a leer ahora una cosa que él me mandó. Carilda. ¿Ah, sí? Amaury. Así que sí viene al caso, aquí todo viene al caso y, viniendo de usted, más al caso. Carilda. Bueno, pues entonces yo lo veía por la mirilla de la puerta. Él tenía el pelo largo -¡imagínese! que andaba por los veinte años y yo andaba por… vamos a no hablar de eso. Amaury. No lo diga, no lo diga. Carilda. Yo decía: Este es otro de esos muchachos que vienen a leer versos y a enamorarla a una, porque yo tenía una casa y vivía sola en la casa ¿comprende?, y sabe cómo son las cosas, como había tanta diferencia de edad, yo siempre pensaba… y eso es cosa de malicia también del pueblo. Amaury. Claro. Carilda. Que no nos perdonaron cuando empezamos el romance y cuando nos casamos. Siempre creyeron que él venía por la casa y porque ya yo tenía cierto nombre, y que él era un muchacho joven que empezaba. Pero yo me enamoré de aquel muchacho por muchas cosas. La primera porque la soledad es una cosa terrible, llevaba años viuda…, con mis gatos. Amaury. Con sus gatos, ¡qué maravilla! Carilda. Mis gatos que han sido mis nenés, mis niñitos, mis compañeros. Bueno, y ahí me conoció él, que yo no tenía ni un centavo y él tenía una casa magnífica donde vivir, había huido del campo porque quería estudiar y esa es la historia de ese joven. Amaury. Claro, él me manda hoy, porque no pudo venir al programa por asuntos personales vinculados con su mamá. Él me manda una carta que no voy a leer completamente porque es una carta privada, pero hay una parte que sí quiero compartir con Carilda, que no la conoce. Carilda. No. Amaury. Y con ustedes. Él me dice, bueno, empieza con “Mi muy admirado Amaury”, muy cariñoso. “Lamento profundamente no asistir a este encuentro con nuestra Carilda. Pero me ha resultado imposible” (y ahí me explica por qué). Pero después dice: “Gracias Amaury por llevarte contigo, en esta feliz ocasión, a una mujer que ya no se puede amar desde un solo cuerpo, que se ha hecho menos mía para volverse propiedad de un pueblo que ha encontrado en su voz la suya propia, prohijada por un deseo interminable de amor y de vida.” Y después me señala: “Hay muchas personas que tal vez contemplen nuestra pareja como un sacrilegio porque nos hemos atrevido a unir nuestras dos juventudes en un matrimonio que ya casi cumple dos decenios.” Y es lo que usted ahora ha estado aclarando y eso es lo que me manda a decir. Carilda. ¡Qué casualidad! Amaury. Ahora, él toca aquí un punto, fíjese que yo no lo tenía ni anotado… pero él toca un punto donde dice, hablando de usted y, ahora entonces vamos a hablar de este tema que él toca aquí. “Carilda ha tenido fe en la justicia, en el amor de su gente y en el triunfo de la verdad. Por ello en mi opinión creo que durante aquellos casi veinte años de silencio en su amada Patria, no supo en la soledad ser infeliz.” ¿Por qué usted cree que hubo tanto tiempo sin que a usted la consideraran lo que siempre ha sido? Una cubana fiel, digna y amante de su Patria. Carilda. Bueno, hay cosas que realmente ni el tiempo ha podido aclarar. Porque la verdad, sí, yo siempre creí que todo pasaría y así fue, todo pasó. Yo había escrito, inclusive, un Canto a Fidel cuando estaba en la Sierra (Maestra) porque yo había conocido a Fidel en la Universidad. Ya yo terminando en la Universidad, Derecho, él empezaba y, naturalmente, al ver que estaba en la Sierra -y esa historia no la voy a hacer porque es larga y ya se ha publicado- Me emocionó mucho aquel compañero de la adolescencia, que alentaba una Revolución que era una esperanza. Amaury. Un símbolo. Carilda. Y así, bueno, entonces ¿qué sucede? La Revolución realmente triunfó, pero inmediatamente, casi, a mí me dejaron cesante de mi trabajo. ¿Por qué? porque yo trabajaba en la Alcaldía de Matanzas. Porque las revoluciones son convulsas y cuando comienzan, como en este caso, hay un problema: Que hay mucha gente que se sube al carro de la Revolución sin haber estado en esa Revolución. Y a mí me parece que los intermediarios fueron, no en este caso, pero en muchos casos, fueron responsables de las injusticias y de las cosas que pasaron. Yo tuve la suerte de que no me quedé completamente cesante y esto es muy bueno decirlo, porque siempre hay alguien que esclarece, que salva, que es un abogado, que hoy es muy notable y es uno de los defensores de los Cinco Héroes, que es el doctor Rodolfo Dávalos. Amaury. Una eminencia, el doctor Dávalos es una eminencia. Carilda. Una eminencia, jurista y él me dijo: no, no importa, tú eres abogada y tú no has cometido delitos… Además, tú tienes ese Canto a Fidel. Él es poeta, pero de esos silenciosos, que no publican. Amaury. Sí, que no quiere publicar. Carilda. Tremendo escritor ¿eh?. Y entonces, bueno, entré en aquel bufete colectivo y fui muy feliz en ese bufete, porque allí se pudo hacer mucha justicia y muchas cosas y no se habló de nada. Pero el veto empezó a pesar de estar yo en el bufete. Amaury. ¿Y no se le publicaba entonces, nada? Carilda. Esto es bueno que se sepa, ¡qué me van a publicar! Pasaron muchas cosas. Amaury. ¿Y cuándo termina el veto? Carilda. Eso termina un día, un buen día, un magnífico día, estoy nombrando personas porque estoy hablando verdades. Amaury. Claro, claro. Carilda. No me gusta hacer anonimatos, y fulano, y que esto. Bueno y además, estoy muy agradecida al doctor Armando Hart. Amaury. Un hombre de la cultura y un hombre justiciero. Carilda. Se apareció en Matanzas un día, a averiguar qué pasaba conmigo, porque él no entendía nada. Amaury. Pero usted nunca abandonó ninguna Revolución ¿qué Revolución abandonó usted? Carilda. ¿Pero qué abandono?, ¡pero si no me exilé con toda mi familia y seguí en mi Tirry 81 pasando calamidades! Yo he comido sopas de yerbas y todas esas cosas. Yo tuve que arrancar las puertas grandes de Tirry 81, que están detrás de las ventanas, para un pobre guajiro que vino, bueno, no era pobre porque tenía más dinero que yo, y me compró las puertas y con eso comí como seis meses. ¡Ay, pero no soy ninguna víctima! Amaury. ¡Claro que no!. Carilda. No, no, no. Amaury. ¡Y con esos ojos!. Carilda. Muy dichosa. Muy dichosa, porque escribí más poesía que nunca. Escribe y escribe y escribe y feliz, feliz. Amaury. Bueno, aquí están sobre la mesa sus libros… Carilda trajo sus libros. Yo me he quedado frío. Carilda. Tengo 43 libros. Claro, entre ediciones, reediciones y cosas en el extranjero. En España tengo cinco libros. Amaury. Ahora, yo quiero de todas maneras, porque cuando hablamos por teléfono el otro día… Carilda. Sí. Amaury. …Hablamos mucho, hablamos más por teléfono que lo que vamos a hablar en la entrevista. Y pasó una cosa bien curiosa, porque yo le dije que a mí me encantaba este soneto, de Sonetos a mi padre, el cuarto soneto. Carilda. Ah, sí. Amaury. Y usted de pronto me dijo: qué casualidad, era el que le gustaba a ¡Eliseo Diego! Carilda. Sí, así mismo es. Amaury. Léame, por favor, ese soneto. Carilda. ¿El último? Amaury. Ese soneto, el último, yo se lo escogí. Carilda. Este es el Cuarto Soneto de la colección, pero cuatro son demasiado. Tu sillón de dentista ¿dónde está? Tu violín de estudiante, ¿cómo suena? Enterrabas centavos en la arena Y otros nombres ponías a mamá. Guardo todas tus cartas y retratos En mis sueños tu próstata se cura, Por el fondo del patio y la ternura Se encaminan tus últimos zapatos. Quiero verte salir en un postigo, ¡Ven fantasma, ven ángel oportuno! Ya no sé lo que hago, lo que digo, Porque quiero beber el desayuno, Con mi padre, mi sabio, mi mendigo En Calzada de Tirry 81. Amaury. ¡Es que es algo…, es precioso ese soneto! y se ve que a usted le afecta, todavía le afecta. No sé ni para qué lo traje. Fíjese qué rápido vamos a hablar de otro tema. A ver si usted me quiere decir este secreto. En este libro (Amaury le muestra un libro) hay una carta, están sus prosas, aparte que hay una foto aquí tremenda, la foto de la portada, con el pelo corto. Carilda. Está agotado ese libro. Amaury. Ese libro está agotado, ah, bueno. Pero ya uno va teniendo cosas que están agotadas, uno se va quedando con ellas. Pero hay un momento, donde hay varias cartas. Usted no quiere, ya me lo dijo por teléfono, hablar de a quién le había hecho las cartas y yo, por supuesto, respeto eso, pero no puedo privar al televidente de esa Carilda irónica que aparece aquí en un momento de esta carta. Carilda. ¡Ah!, va a leer esa, ¡vale!. Amaury. En un momento de esta carta yo por poquito me…, yo me arrastré cuando la leí la primera vez -carta número 4 se llama-, Te escribo por recomendación de este papel amarillo que vi sobre la mesa y para que me perdones el incumplimiento de la amenaza: El director tropieza con todos los sueños, así que dispuso sin mi permiso, que trabajara hoy de noche. Como te encantan las sorpresas, estarás muy contento de ver a otra mujer y no a la que pronosticó el telegrama. Pues bien, deseo con todos los humores negros de mi venganza, que solo caiga en tus brazos una soprano calva de 190 libras. No vamos a hablar de a quién se la hizo, pero vamos a hablar de esa Carilda maldita, esa Carilda, que vaya, es que no… “Lo que deseo es que caiga en tus brazos una soprano calva de 190 libras“. (risas) Carilda. (risas) Ay, son cosas de la juventud. Amaury. Ahora, ¿cómo fue aquello del tren que viene de Santiago, pasa por Matanzas y una persona que la amaba le ponía mensajes en el tren? ¿Qué cosa es eso, Carilda? Carilda. Ay, pero mira lo que estás sacando hoy. Óyeme, pero ¿cuántos cuentos te han hecho? Qué cosas… Amaury. Pero es que eso es tan bello. Carilda. Bueno, es verdad, es una cosa de…, y estoy hablando del año 50, porque fue el año, lo recuerdo perfectamente, en que salió Al sur de mi garganta. Al sur… nace en el 49, pero se lleva el Premio Nacional de Poesía del 50. Y entonces él es un poeta, por cierto, un poeta muy singular, porque es que tenía muchos oficios y era matemático, era graduado de La Sorbona, de Yale, yo no sé de cuántos lugares. Era un hombre muy talentoso que apareció en Cuba. Y como él quería enamorarse, porque él quería enamorarse de algún modo de alguna cubana, y sobre todo que fuera un amor imposible, digo yo, porque hizo todo lo posible. Yo tenía mi novio, yo era novia de Hugo Ania que era un noviazgo reciente y que después nos casamos. Y entonces, pues… No voy a contar lo que pasó en el medio, porque hubo problemas muy serios. Amaury. No, no. Carilda. Esa es la mitología con que el pueblo cubano me ha adornado a mí, porque ese mito es un adorno. Amaury. Claro. Carilda. La gente quiere que yo sea como me han inventado. Amaury. Exactamente. Carilda. Y realmente yo soy una señora muy respetable, ¡Ay!, ¿qué dije? (se tapa la boca) Amaury. No, sí lo es. Sí, Carilda, sí lo es. Carilda. No, pero es que todo el mundo se va a disgustar. Amaury. No, nadie se va a disgustar. Carilda. ¿Tú crees que no? Amaury. No, nadie se va a disgustar. La gente va a seguir con la mitología que quiera crearse sobre usted. Pero es bueno que de una vez se diga, que lo importante de usted, aparte de su belleza, aparte de su talento, de su simpatía, es su gran obra poética, que es lo que la va a trascender. Y la mitología que la gente se crea sobre los artistas, esa se va a quedar en el camino y lo que va a quedar al final, son estos poemas, son estos libros, eso es lo que va… Carilda. …Ay, Amaury. ¡Qué generoso eres! Amaury. No, generoso no, soy justo con usted. Carilda. Te quiero. Amaury. Carilda ¿Y entonces lo del tren? ¿El tren salía de dónde? Carilda. Él tren venía de Santiago y llegaba a La Habana, aquí, pero claro, pasaba por Matanzas. Y entonces, este escritor, uruguayo, me escribía, después que se fue de Matanzas, me escribía desde allá. Pero él quería que llegaran las cosas tan pronto que iba al último vagón del tren. Ya me lo había advertido por teléfono: por la mañana me decía: Carilda, ahora voy a escribirte un mensaje en la pared del vagón último del tren, bueno, yo iba por la noche cuando llegaba el tren a Matanzas a ver aquello, a leer aquello. ¡Qué lindas cosas escribía! Amaury. Por eso ahí empiezan las historias. Carilda. Y ahí empiezan las historias de Carilda ¿comprende? Amaury. Claro Carilda. Que después de todo son historias muy lindas y no hay por qué renunciar a ellas. Amaury. Pero mire, yo le voy a decir algo. El pueblo cubano, el lector cubano y más que el lector cubano, incluso, el que no la ha leído -que se está perdiendo una de las maravillas del mundo- la quiere a usted, usted es amada. Usted es amada por todo el mundo. Carilda. No, porque amo, porque amo al pueblo. Amaury. Claro, porque eso va y viene, eso es un efecto de ida y vuelta. Ahora, yo quiero, Carilda, porque ya el programa lo estamos terminando. Mire, usted me trajo hoy de regalo la última edición de Al sur de mi garganta, es esta. Carilda. 60 años cumplió el año pasado. Amaury. Con una dedicatoria que es para mi corazón, yo no voy a leer lo que dice, que es muy emocionante y ya yo tengo hace rato los ojos aguados. Pero es que yo traje para que Carilda me firmara… Carilda. …¡Ay, chico!… Amaury. …La edición Príncipe… Carilda. …Eso me emocionó… Amaury. …De Al sur de mi garganta... Carilda. Porque nadie la tiene, porque se hicieron 300 ejemplares. Imagínense, en el año 49. Amaury. Claro, del 49 y esto se lo regala a mi tío Raúl y por supuesto a mi tía María Luisa también, Pascualito, un amigo, el 11 de marzo de 1950. Y aquí está con las ilustraciones. ¿Cuántos libros se hicieron de esta edición? Carilda. 300 nada más. Esto lo pagó mi padre. Entonces no había editoriales. Amaury. ¡Fíjese que es propiedad del autor!. Carilda. Y tuve la suerte de que con ese librito gané el premio. Amaury. Entonces usted me va a hacer el favor de poner su nombre aquí. Y después, porque estamos en televisión, me pone una cosita más, porque eso es un tesoro de la biblioteca nuestra, de mi esposa y mía. Un programa bien emotivo y bien difícil. Esto no se puede creer. Carilda. Es que tú no habías nacido cuando el libro se publicó. Amaury. ¡Claro que no había nacido!. Carilda. Ah, imagínate. Amaury. Pero ya había nacido usted, había nacido su poesía y a lo mejor, quién sabe si yo nací de algún poema de estos. Entonces, ahora va a terminar el programa usted. Yo antes le voy a agradecer su gentileza, su viaje, el suyo y el de sus compañeros que la han traído. Ha sido un programa muy especial. Es además el programa con el que estamos comenzando este año 2011, es el primer programa de enero de 2011. Todavía hay una grata temperatura afuera, hemos acabado de pasar las Navidades…, yo quiero que usted me lea este poema que es uno de los poemas que más me gusta suyo, y que de esa manera despida el programa y le agradezco señora, su poesía, su talante, su genio, su gentileza, su belleza. Su amor a Cuba, su amor a la Patria. Carilda. Gracias, la agradecida soy yo. Gracias. Adiós locura de mis treinta años, Besado en julio bajo luna llena, Al tiempo de la herida y la azucena Adiós mi venda de taparme daños. Adiós mi excusa, mi desorden bello, mi alarma tierna, mi ignorante fruta Estrella transitoria que se enluta, Esperanza de todo por mi cuello. Adiós muchacho de la cita corta, Adiós pequeña ayuda de mi aorta, Tristísimo juguete violentado Adiós verde placer, falso delito Adiós sin una queja, sin un grito Adiós mi sueño nunca abandonado. Amaury. Gracias, Carilda, muchas gracias por existir. Nos veremos pronto. Carilda. Gracias. Petí arregla el vestido de la poeta y Solís verifica que el micrófono permita escuchar con nitidez la voz de Carilda. El programa está por comenzar. Referencias Cuba Debate - www.cubadebate.cu/noticias/2011/01/04/carilda-oliver-he-sido-muy-feliz-siendo-poeta/ BIOGRAFÍA Su primer libro, "Preludio Lírico", fue publicado en Matanzas en 1943. En esta selección de poemas escritos entre 1939 y 1942, ya se hacen presentes: -El amor, con sus devanes, inquietudes, zozobras, desalientos, aciertos, quizás con una pluma inexperta que no sabía dominar emociones e impregnada del entorno un tanto melodramático que a muchos atacaba; -La familia, la abuela, la madre y el padre presentes en un cuadro que no desaparecerá nunca de su obra. Después de obtener el Segundo Lugar en el Concurso Internacional de Poesía, organizado por la National Broadcasting Co. de Nueva York, Estados Unidos, publica en 1949 "Al sur de mi garganta", libro con el que ganó el Premio Nacional de Poesía, al mismo tiempo que trabaja en la biblioteca Gener y del Monte, es declarada Hija Eminente de la Atenas de Cuba. En esa misma temporada culmina sus estudios en la Escuela de Artes Plásticas de Matanzas que la acreditan como profesora de Dibujo, Pintura y Escultura y contrajo nupcias con el abogado y poeta Hugo Ania Mercier, de quien se divorciaría en 1955 tras una relación turbulenta. Tuvo otros 2 matrimonios: Félix Pons, cuya muerte la inspiró para su libro "Se me ha perdido un hombre" y finalmente Raidel Hernández, muy joven, con quien comparte ahora su vida. Se le reconoce una intensa labor como profesora en escuelas de su natal Matanzas, ligando a su amor por el magisterio su trabajo como abogada y su pasión por la poesía. Hasta la actualidad cuenta con 43 publicaciones que incluyen prosa y poesía, más varios premios y reconocimientos. Poemas suyos han sido traducidos al inglés, francés, italiano, ruso, búlgaro, rumano y vietnamita. Desde 1980 funciona en Madrid una Tertulia Poética que lleva su nombre y que, además, convoca anualmente a un Premio Internacional de Poesía. Aunque su obra transmite muchas veces dolor, añoranza o vacío, desde el "Me desordeno amor..." que hizo con tan solo 24 años, su poesía está cargada de sensualidad, desenfado, seducción, y la muestran progresista, liberal y hasta un tanto irreverente. En una ocasión comentó: "Tal vez me colgaron la etiqueta de erótica porque conocen más esa proyección mía que las otras. Es la que escogen los declamadores, la que aparece en programas radiales y aquella que se ha musicalizado y difundido casi sin yo darme cuenta." Ella misma nos da su receta de erotismo: “Hay que renunciar a traducir su misterio. Entre el erotismo y la profanación, entre lo que debe ser y lo que tiene que ser hay una línea divisoria muy fina. Nace, no se aprende”. Referencias Wikipedia - es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carilda_Oliver Cuba Literaria - www.cubaliteraria.cu/autor/carilda_oliver/biografia.html Ecured - www.ecured.cu/index.php/Carilda_Oliver_Labra

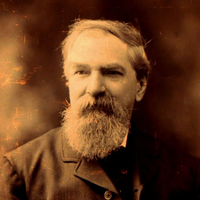

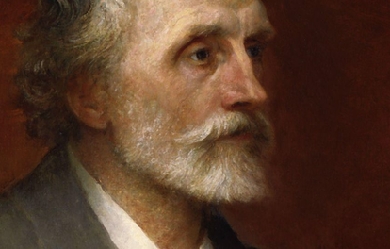

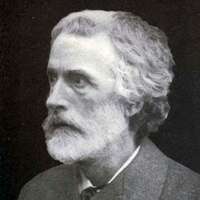

George Meredith, OM (12 February 1828 – 18 May 1909) was an English novelist and poet of the Victorian era. Meredith was born in Portsmouth, England, a son and grandson of naval outfitters. His mother died when he was five. At the age of 14 he was sent to a Moravian School in Neuwied, Germany, where he remained for two years. He read law and was articled as a solicitor, but abandoned that profession for journalism and poetry. He collaborated with Edward Gryffydh Peacock, son of Thomas Love Peacock in publishing a privately circulated literary magazine, the Monthly Observer. He married Edward Peacock's widowed sister Mary Ellen Nicolls in 1849 when he was twenty-one years old and she was twenty-eight. He collected his early writings, first published in periodicals, into Poems, published to some acclaim in 1851. His wife ran off with the English Pre-Raphaelite painter Henry Wallis [1830–1916] in 1858; she died three years later. The collection of "sonnets" entitled Modern Love (1862) came of this experience as did The Ordeal of Richard Feverel, his first "major novel". He married Marie Vulliamy in 1864 and settled in Surrey. He continued writing novels and poetry, often inspired by nature. His writing was characterised by a fascination with imagery and indirect references. He had a keen understanding of comedy and his Essay on Comedy (1877) is still quoted in most discussions of the history of comic theory. In The Egoist, published in 1879, he applies some of his theories of comedy in one of his most enduring novels. Some of his writings, including The Egoist, also highlight the subjugation of women during the Victorian period. During most of his career, he had difficulty achieving popular success. His first truly successful novel was Diana of the Crossways published in 1885. Meredith supplemented his often uncertain writer's income with a job as a publisher's reader. His advice to Chapman and Hall made him influential in the world of letters. His friends in the literary world included, at different times, William and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Algernon Charles Swinburne, Leslie Stephen, Robert Louis Stevenson, George Gissing and J. M. Barrie. His contemporary Sir Arthur Conan Doyle paid him homage in the short-story The Boscombe Valley Mystery, when Sherlock Holmes says to Dr. Watson during the discussion of the case, "And now let us talk about George Meredith, if you please, and we shall leave all minor matters until to-morrow." Oscar Wilde, in his dialogue The Decay of Lying, implies that Meredith, along with Balzac, is his favourite novelist, saying "Ah, Meredith! Who can define him? His style is chaos illumined by flashes of lightning". In 1868 he was introduced to Thomas Hardy by Frederick Chapman of Chapman & Hall the publishers. Hardy had submitted his first novel, The Poor Man and the Lady. Meredith advised Hardy not to publish his book as it would be attacked by reviewers and destroy his hopes of becoming a novelist. Meredith felt the book was too bitter a satire on the rich and counselled Hardy to put it aside and write another 'with a purely artistic purpose' and more of a plot. Meredith spoke from experience; his first big novel, The Ordeal of Richard Feverel, was judged so shocking that Mudie's circulating library had cancelled an order of 300 copies. Hardy continued to try and publish the novel: however it remained unpublished, though he clearly took Meredith's advice seriously. Before his death, Meredith was honoured from many quarters: he succeeded Lord Tennyson as president of the Society of Authors; in 1905 he was appointed to the Order of Merit by King Edward VII. In 1909, he died at his home in Box Hill, Surrey. Works Essays * Essay on Comedy (1877) Novels * The Shaving of Shagpat (1856) * Farina (1857) * The Ordeal of Richard Feverel (1859) * Evan Harrington (1861) * Emilia in England (1864), republished as Sandra Belloni in 1887 * Rhoda Fleming (1865) * Vittoria (1867) * The Adventures of Harry Richmond (1871) * Beauchamp's Career (1875) * The House on the Beach (1877) * The Case of General Ople and Lady Camper (1877) * The Tale of Chloe (1879) * The Egoist (1879) * The Tragic Comedians (1880) * Diana of the Crossways (1885) * One of our Conquerors (1891) * Lord Ormont and his Aminta (1894) * The Amazing Marriage (1895) * Celt and Saxon (1910) Poetry * Poems (1851) * Modern Love (1862) * Poems and Lyrics of the Joy of Earth (1883) * The Woods of Westermain (1883) * A Faith on Trial (1885) * Ballads and Poems of Tragic Life (1887) * A Reading of Earth (1888) * The Empty Purse (1892) * Odes in Contribution to the Song of French History(1898) * A Reading of Life (1901) * Last Poems (1909) * Lucifer in Starlight * The Lark Ascending (the inspiration for Vaughan Williams' instrumental work The Lark Ascending). References Wikipedia - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Meredith

Siegfried Loraine Sassoon (8 September 1886 – 1 September 1967) was an English poet, author and soldier. Decorated for bravery on the Western Front, he became one of the leading poets of the First World War. His poetry both described the horrors of the trenches, and satirised the patriotic pretensions of those who, in Sassoon's view, were responsible for a vainglorious war. He later won acclaim for his prose work, notably his three-volume fictionalised autobiography, collectively known as the "Sherston Trilogy". Motivated by patriotism, Sassoon joined the British Army just as the threat of World War I was realised, and was in service with the Sussex Yeomanry on the day the United Kingdom declared war (4 August 1914). He broke his arm badly in a riding accident and was put out of action before even leaving England, spending the spring of 1915 convalescing.

John Clare (13 July 1793 – 20 May 1864) was an English poet, the son of a farm labourer, who came to be known for his celebratory representations of the English countryside and his lamentation of its disruption. His poetry underwent a major re-evaluation in the late 20th century and he is often now considered to be among the most important 19th-century poets. His biographer Jonathan Bate states that Clare was "the greatest labouring-class poet that England has ever produced. No one has ever written more powerfully of nature, of a rural childhood, and of the alienated and unstable self”. Early life Clare was born in Helpston, six miles to the north of the city of Peterborough. In his life time, the village was in the Soke of Peterborough in Northamptonshire and his memorial calls him "The Northamptonshire Peasant Poet". Helpston now lies in the Peterborough unitary authority of Cambridgeshire. He became an agricultural labourer while still a child; however, he attended school in Glinton church until he was twelve. In his early adult years, Clare became a pot-boy in the Blue Bell public house and fell in love with Mary Joyce; but her father, a prosperous farmer, forbade her to meet him. Subsequently he was a gardener at Burghley House. He enlisted in the militia, tried camp life with Gypsies, and worked in Pickworth as a lime burner in 1817. In the following year he was obliged to accept parish relief. Malnutrition stemming from childhood may be the main culprit behind his 5-foot stature and may have contributed to his poor physical health in later life. Early poems Clare had bought a copy of Thomson's Seasons and began to write poems and sonnets. In an attempt to hold off his parents' eviction from their home, Clare offered his poems to a local bookseller named Edward Drury. Drury sent Clare's poetry to his cousin John Taylor of the publishing firm of Taylor & Hessey, who had published the work of John Keats. Taylor published Clare's Poems Descriptive of Rural Life and Scenery in 1820. This book was highly praised, and in the next year his Village Minstrel and other Poems were published. Midlife He had married Martha ("Patty") Turner in 1820. An annuity of 15 guineas from the Marquess of Exeter, in whose service he had been, was supplemented by subscription, so that Clare became possessed of £45 annually, a sum far beyond what he had ever earned. Soon, however, his income became insufficient, and in 1823 he was nearly penniless. The Shepherd's Calendar (1827) met with little success, which was not increased by his hawking it himself. As he worked again in the fields his health temporarily improved; but he soon became seriously ill. Earl FitzWilliam presented him with a new cottage and a piece of ground, but Clare could not settle in his new home. Clare was constantly torn between the two worlds of literary London and his often illiterate neighbours; between the need to write poetry and the need for money to feed and clothe his children. His health began to suffer, and he had bouts of severe depression, which became worse after his sixth child was born in 1830 and as his poetry sold less well. In 1832, his friends and his London patrons clubbed together to move the family to a larger cottage with a smallholding in the village of Northborough, not far from Helpston. However, he felt only more alienated. His last work, the Rural Muse (1835), was noticed favourably by Christopher North and other reviewers, but this was not enough to support his wife and seven children. Clare's mental health began to worsen. As his alcohol consumption steadily increased along with his dissatisfaction with his own identity, Clare's behaviour became more erratic. A notable instance of this behaviour was demonstrated in his interruption of a performance of The Merchant of Venice, in which Clare verbally assaulted Shylock. He was becoming a burden to Patty and his family, and in July 1837, on the recommendation of his publishing friend, John Taylor, Clare went of his own volition (accompanied by a friend of Taylor's) to Dr Matthew Allen's private asylum High Beach near Loughton, in Epping Forest. Taylor had assured Clare that he would receive the best medical care. Later life and death During his first few asylum years in Essex (1837–1841), Clare re-wrote famous poems and sonnets by Lord Byron. His own version of Child Harold became a lament for past lost love, and Don Juan, A Poem became an acerbic, misogynistic, sexualised rant redolent of an aging Regency dandy. Clare also took credit for Shakespeare's plays, claiming to be the Renaissance genius himself. "I'm John Clare now," the poet claimed to a newspaper editor, "I was Byron and Shakespeare formerly." In 1841, Clare left the asylum in Essex, to walk home, believing that he was to meet his first love Mary Joyce; Clare was convinced that he was married with children to her and Martha as well. He did not believe her family when they told him she had died accidentally three years earlier in a house fire. He remained free, mostly at home in Northborough, for the five months following, but eventually Patty called the doctors in. Between Christmas and New Year in 1841, Clare was committed to the Northampton General Lunatic Asylum (now St Andrew's Hospital). Upon Clare's arrival at the asylum, the accompanying doctor, Fenwick Skrimshire, who had treated Clare since 1820, completed the admission papers. To the enquiry "Was the insanity preceded by any severe or long-continued mental emotion or exertion?", Dr Skrimshire entered: "After years of poetical prosing." He remained here for the rest of his life under the humane regime of Dr Thomas Octavius Prichard, encouraged and helped to write. Here he wrote possibly his most famous poem, I Am. He died on 20 May 1864, in his 71st year. His remains were returned to Helpston for burial in St Botolph’s churchyard. Today, children at the John Clare School, Helpston's primary, parade through the village and place their 'midsummer cushions' around Clare's gravestone (which has the inscriptions "To the Memory of John Clare The Northamptonshire Peasant Poet" and "A Poet is Born not Made") on his birthday, in honour of their most famous resident. The thatched cottage where he was born was bought by the John Clare Education & Environment Trust in 2005 and is restoring the cottage to its 18th century state. Poetry In his time, Clare was commonly known as "the Northamptonshire Peasant Poet". Since his formal education was brief, Clare resisted the use of the increasingly standardised English grammar and orthography in his poetry and prose. Many of his poems would come to incorporate terms used locally in his Northamptonshire dialect, such as 'pooty' (snail), 'lady-cow' (ladybird), 'crizzle' (to crisp) and 'throstle' (song thrush). In his early life he struggled to find a place for his poetry in the changing literary fashions of the day. He also felt that he did not belong with other peasants. Clare once wrote "I live here among the ignorant like a lost man in fact like one whom the rest seemes careless of having anything to do with—they hardly dare talk in my company for fear I should mention them in my writings and I find more pleasure in wandering the fields than in musing among my silent neighbours who are insensible to everything but toiling and talking of it and that to no purpose.” It is common to see an absence of punctuation in many of Clare's original writings, although many publishers felt the need to remedy this practice in the majority of his work. Clare argued with his editors about how it should be presented to the public. Clare grew up during a period of massive changes in both town and countryside as the Industrial Revolution swept Europe. Many former agricultural workers, including children, moved away from the countryside to over-crowded cities, following factory work. The Agricultural Revolution saw pastures ploughed up, trees and hedges uprooted, the fens drained and the common land enclosed. This destruction of a centuries-old way of life distressed Clare deeply. His political and social views were predominantly conservative ("I am as far as my politics reaches 'King and Country'—no Innovations in Religion and Government say I."). He refused even to complain about the subordinate position to which English society relegated him, swearing that "with the old dish that was served to my forefathers I am content." His early work delights both in nature and the cycle of the rural year. Poems such as Winter Evening, Haymaking and Wood Pictures in Summer celebrate the beauty of the world and the certainties of rural life, where animals must be fed and crops harvested. Poems such as Little Trotty Wagtail show his sharp observation of wildlife, though The Badger shows his lack of sentiment about the place of animals in the countryside. At this time, he often used poetic forms such as the sonnet and the rhyming couplet. His later poetry tends to be more meditative and use forms similar to the folks songs and ballads of his youth. An example of this is Evening. His knowledge of the natural world went far beyond that of the major Romantic poets. However, poems such as I Am show a metaphysical depth on a par with his contemporary poets and many of his pre-asylum poems deal with intricate play on the nature of linguistics. His 'bird's nest poems', it can be argued, illustrate the self-awareness, and obsession with the creative process that captivated the romantics. Clare was the most influential poet, aside from Wordsworth to practice in an older style. Revival of interest in the twentieth century Clare was relatively forgotten during the later nineteenth century, but interest in his work was revived by Arthur Symons in 1908, Edmund Blunden in 1920 and John and Anne Tibble in their ground-breaking 1935 2-volume edition. Benjamin Britten set some of 'May' from A Shepherd's Calendar in his Spring Symphony of 1948, and included a setting of The Evening Primrose in his Five Flower Songs Copyright to much of his work has been claimed since 1965 by the editor of the Complete Poetry (OUP, 9 vols., 1984–2003), Professor Eric Robinson though these claims were contested. Recent publishers have refused to acknowledge the claim (especially in recent editions from Faber and Carcanet) and it seems the copyright is now defunct. The John Clare Trust purchased Clare Cottage in Helpston in 2005, preserving it for future generations. In May 2007 the Trust gained £1.m of funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund and commissioned Jefferson Sheard Architects to create the new landscape design and Visitor Centre, including a cafe, shop and exhibition space. The Cottage has been restored using traditional building methods and opened to the public. The largest collection of original Clare manuscripts are housed at Peterborough Museum, where they are available to view by appointment. Since 1993, the John Clare Society of North America has organised an annual session of scholarly papers concerning John Clare at the annual Convention of the Modern Language Association of America. Poetry collections by Clare (chronological) * Poems Descriptive of Rural Life and Scenery. London, 1820. * The Village Minstrel, and Other Poems. London, 1821. * The Shepherd's Calendar with Village Stories and Other Poems. London, 1827 * The Rural Muse. London, 1835. * Sonnet. London 1841 * First Love * Snow Storm. * The Firetail. * The Badger – Time unknown References Wikipedia - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Clare

Arturo Borja Pérez, (n. Quito, 1892 - f. Ibídem, 13 de noviembre de 1912) fue un poeta ecuatoriano, perteneciente al movimiento llamado “La Generación Decapitada” y el primero del grupo en despuntar como modernista. Es muy escasa su obra artística pero suficiente para determinar la calidad de poeta: una corona de veinte composiciones forma el libro titulado La flauta de ónix, y seis poemas más; obras que fueron publicadas póstumamente. Se suicidó en la ciudad de Quito, el 13 de noviembre de 1912, contando apenas con 20 años de edad. Ofrenda de rosas (A Arturo Borja) Recuerdo que te hallé por mi camino como un Verlaine aún adolescente, ¡y daba el signo de un fatal destino tu alma de estirpe lírica y ardiente! Y ambos fraternizamos; que tus rosas para todas las almas entreabrías, ¡haciéndote en las horas humildosas dueño de todas las melancolías...! Quién volviera a tus ojos, en ofrenda, la vida humilde que suspira y canta, como el Rubí de manos de leyenda que antaño dijo a Lázaro: ¡Levanta! Evoco el sueño juvenil de un día que, en el Claustro del Arte bien sentido, matamos la viril hipocrecía, y laboramos lentos el gemido. Y ahora la luna de tu sistro agrestre, al visitar nuestro santurario frío, da su color de lágrima celeste en el cristal de tu crisol vacío... ¡Adiós, fuente de lánguido quebranto!, que volvías un Fénix mi rosal, ¡encantando las rosas sin encanto cuando el encanto huía con el mal! ¡Adiós, fuente de lágrimas cantoras que halagaron el viaje juvenil!; de la angustia de Abril refrescadoras como lluvias caídas en Abril... Duerme y reposa; que quizás es bueno sólo el sueño sin sueño en que caíste, ¡la flor de espino y el laurel de heleno entremezclados en tu frente triste! —Humberto Fierro Feliz tú, hermano mío (Al espíritu fraternal de Arturo Borja) Poeta, hermano mío, que como yo sufriste, el frío del vacío y la grandeza triste de saberte una nube en prisión de rocío; tu buen hermano en lira, en rosa, azul y luna que inspira la mentira de la verde laguna, sabe envidiar tu suerte porque tu suerte admira. Lloro tu vida breve por lo que dado hubieras, pero la leve nieve de tus quimeras en nube se transforma y desde lo alto llueve. Poeta, hermano mío, ya no estarás más triste, ni el frío del vacío sentirás que sentiste... Ya no eres una nube encerrada en rocío; después de que partiste tu lluvia se hizo un río que da savia a tu rosa y a tu bulbul alpiste... ¡Feliz tú, hermano mío! —Alejandro Sux

Sara Teasdale (August 8, 1884 – January 29, 1933) was an American lyric poet. She was born Sarah Trevor Teasdale in St. Louis, Missouri, and used the name Sara Teasdale Filsinger after her marriage in 1914. She had such poor health for so much of her childhood, home schooled until age 9, that it was only at age 10 that she was well enough to begin school. She started at Mary Institute in 1898, but switched to Hosmer Hall in 1899, graduating in 1903. I Shall Not Care WHEN I am dead and over me bright April Shakes out her rain-drenched hair, Tho' you should lean above me broken-hearted, I shall not care. I shall have peace, as leafy trees are peaceful When rain bends down the bough, And I shall be more silent and cold-hearted Than you are now.

Vicente García-Huidobro Fernández (Santiago, 10 de enero de 1893 – Cartagena, 2 de enero de 1948), más conocido como Vicente Huidobro, fue un poeta chileno. Iniciador y exponente del creacionismo, es considerado uno de los más destacados poetas chilenos, junto con Gabriela Mistral, Pablo Neruda y Pablo de Rokha. Nació en el seno de una familia adinerada, relacionada con la política y la banca. Su padre era el heredero del marquesado de Casa Real y su madre, una activista feminista y anfitriona de numerosas veladas literarias.

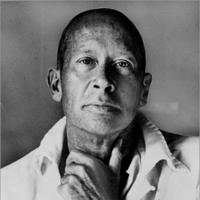

James Mercer Langston Hughes (February 1, 1902 – May 22, 1967) was an American poet, social activist, novelist, playwright, and columnist. He was one of the earliest innovators of the then-new literary art form jazz poetry. Hughes is best known for his work during the Harlem Renaissance. He famously wrote about the period that “the negro was in vogue” which was later paraphrased as “when Harlem was in vogue”.

Amy Lawrence Lowell (February 9, 1874 – May 12, 1925) was an American poet of the imagist school from Brookline, Massachusetts, who posthumously won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1926. Amy was born into Brookline’s Lowell family, sister to astronomer Percival Lowell and Harvard president Abbott Lawrence Lowell. She never attended college because her family did not consider it proper for a woman to do so. She compensated for this lack with avid reading and near-obsessive book collecting. She lived as a socialite and travelled widely, turning to poetry in 1902 (age 28) after being inspired by a performance of Eleonora Duse in Europe.

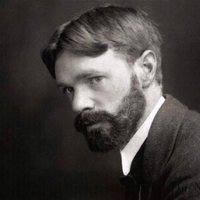

David Herbert Richards Lawrence (11 September 1885 – 2 March 1930) was an English novelist, poet, playwright, essayist, literary critic and painter who published as D. H. Lawrence. His collected works represent an extended reflection upon the dehumanising effects of modernity and industrialisation. In them, Lawrence confronts issues relating to emotional health and vitality, spontaneity, and instinct. Lawrence’s opinions earned him many enemies and he endured official persecution, censorship, and misrepresentation of his creative work throughout the second half of his life, much of which he spent in a voluntary exile which he called his “savage pilgrimage”. At the time of his death, his public reputation was that of a pornographer who had wasted his considerable talents. E. M. Forster, in an obituary notice, challenged this widely held view, describing him as, “The greatest imaginative novelist of our generation”. Later, the influential Cambridge critic F. R. Leavis championed both his artistic integrity and his moral seriousness, placing much of Lawrence's fiction within the canonical “great tradition” of the English novel. Lawrence is now valued by many as a visionary thinker and significant representative of modernism in English literature.