Info

Goethe en la Campaña Romana

Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein

1787

Städel Museum

Emily Elizabeth Dickinson (December 10, 1830 – May 15, 1886) was an American poet. Little-known during her life, she has since been regarded as one of the most important figures in American poetry. Evidence suggests that Dickinson lived much of her life in isolation. Considered an eccentric by locals, she developed a penchant for white clothing and was known for her reluctance to greet guests or, later in life, to even leave her bedroom. Dickinson never married, and most friendships between her and others depended entirely upon correspondence.

Ella Wheeler Wilcox (November 5, 1850– October 30, 1919) was an American author and poet. Her best-known work was Poems of Passion. Her most enduring work was “Solitude”, which contains the lines, “Laugh, and the world laughs with you; weep, and you weep alone”. Her autobiography, The Worlds and I, was published in 1918, a year before her death. Biography Ella Wheeler was born in 1850 on a farm in Johnstown, Wisconsin, east of Janesville, the youngest of four children. The family soon moved north of Madison. She started writing poetry at a very early age, and was well known as a poet in her own state by the time she graduated from high school. Her most famous poem, “Solitude”, was first published in the February 25, 1883 issue of The New York Sun. The inspiration for the poem came as she was travelling to attend the Governor’s inaugural ball in Madison, Wisconsin. On her way to the celebration, there was a young woman dressed in black sitting across the aisle from her. The woman was crying. Miss Wheeler sat next to her and sought to comfort her for the rest of the journey. When they arrived, the poet was so depressed that she could barely attend the scheduled festivities. As she looked at her own radiant face in the mirror, she suddenly recalled the sorrowful widow. It was at that moment that she wrote the opening lines of “Solitude”: Laugh, and the world laughs with you; Weep, and you weep alone. For the sad old earth must borrow its mirth But has trouble enough of its own She sent the poem to the Sun and received $5 for her effort. It was collected in the book Poems of Passion shortly after in May 1883. In 1884, she married Robert Wilcox of Meriden, Connecticut, where the couple lived before moving to New York City and then to Granite Bay in the Short Beach section of Branford, Connecticut. The two homes they built on Long Island Sound, along with several cottages, became known as Bungalow Court, and they would hold gatherings there of literary and artistic friends. They had one child, a son, who died shortly after birth. Not long after their marriage, they both became interested in theosophy, new thought, and spiritualism. Early in their married life, Robert and Ella Wheeler Wilcox promised each other that whoever went first through death would return and communicate with the other. Robert Wilcox died in 1916, after over thirty years of marriage. She was overcome with grief, which became ever more intense as week after week went without any message from him. It was at this time that she went to California to see the Rosicrucian astrologer, Max Heindel, still seeking help in her sorrow, still unable to understand why she had no word from her Robert. She wrote of this meeting: In talking with Max Heindel, the leader of the Rosicrucian Philosophy in California, he made very clear to me the effect of intense grief. Mr. Heindel assured me that I would come in touch with the spirit of my husband when I learned to control my sorrow. I replied that it seemed strange to me that an omnipotent God could not send a flash of his light into a suffering soul to bring its conviction when most needed. Did you ever stand beside a clear pool of water, asked Mr. Heindel, and see the trees and skies repeated therein? And did you ever cast a stone into that pool and see it clouded and turmoiled, so it gave no reflection? Yet the skies and trees were waiting above to be reflected when the waters grew calm. So God and your husband’s spirit wait to show themselves to you when the turbulence of sorrow is quieted. Several months later, she composed a little mantra or affirmative prayer which she said over and over “I am the living witness: The dead live: And they speak through us and to us: And I am the voice that gives this glorious truth to the suffering world: I am ready, God: I am ready, Christ: I am ready, Robert.”. Wilcox made efforts to teach occult things to the world. Her works, filled with positive thinking, were popular in the New Thought Movement and by 1915 her booklet, What I Know About New Thought had a distribution of 50,000 copies, according to its publisher, Elizabeth Towne. The following statement expresses Wilcox’s unique blending of New Thought, Spiritualism, and a Theosophical belief in reincarnation: “As we think, act, and live here today, we built the structures of our homes in spirit realms after we leave earth, and we build karma for future lives, thousands of years to come, on this earth or other planets. Life will assume new dignity, and labor new interest for us, when we come to the knowledge that death is but a continuation of life and labor, in higher planes”. Her final words in her autobiography The Worlds and I: “From this mighty storehouse (of God, and the hierarchies of Spiritual Beings ) we may gather wisdom and knowledge, and receive light and power, as we pass through this preparatory room of earth, which is only one of the innumerable mansions in our Father’s house. Think on these things”. Ella Wheeler Wilcox died of cancer on October 30, 1919 in Short Beach. Poetry A popular poet rather than a literary poet, in her poems she expresses sentiments of cheer and optimism in plainly written, rhyming verse. Her world view is expressed in the title of her poem “Whatever Is—Is Best”, suggesting an echo of Alexander Pope’s “Whatever is, is right,” a concept formally articulated by Gottfried Leibniz and parodied by Voltaire’s character Doctor Pangloss in Candide. None of Wilcox’s works were included by F. O. Matthiessen in The Oxford Book of American Verse, but Hazel Felleman chose no fewer than fourteen of her poems for Best Loved Poems of the American People, while Martin Gardner selected “The Way Of The World” and “The Winds of Fate” for Best Remembered Poems. She is frequently cited in anthologies of bad poetry, such as The Stuffed Owl: An Anthology of Bad Verse and Very Bad Poetry. Sinclair Lewis indicates Babbitt’s lack of literary sophistication by having him refer to a piece of verse as “one of the classic poems, like 'If’ by Kipling, or Ella Wheeler Wilcox’s ‘The Man Worth While.’” The latter opens: It is easy enough to be pleasant, When life flows by like a song, But the man worth while is one who will smile, When everything goes dead wrong. Her most famous lines open her poem “Solitude”: Laugh and the world laughs with you, Weep, and you weep alone; The good old earth must borrow its mirth, But has trouble enough of its own. “The Winds of Fate” is a marvel of economy, far too short to summarize. In full: One ship drives east and another drives west With the selfsame winds that blow. ’Tis the set of the sails, And Not the gales, That tell us the way to go. Like the winds of the sea are the ways of fate; As we voyage along through life, ’Tis the set of a soul That decides its goal, And not the calm or the strife. Ella Wheeler Wilcox cared about alleviating animal suffering, as can be seen from her poem, “Voice of the Voiceless”. It begins as follows: So many gods, so many creeds, So many paths that wind and wind, While just the art of being kind Is all the sad world needs. I am the voice of the voiceless; Through me the dumb shall speak, Till the deaf world’s ear be made to hear The wrongs of the wordless weak. From street, from cage, and from kennel, From stable and zoo, the wail Of my tortured kin proclaims the sin Of the mighty against the frail.

Margaret Eleanor Atwood (born November 18, 1939) is a Canadian poet, novelist, literary critic, essayist, teacher, environmental activist, and inventor. Since 1961, she has published 18 books of poetry, 18 novels, 11 books of non-fiction, nine collections of short fiction, eight children's books, and two graphic novels, and a number of small press editions of both poetry and fiction. Atwood has won numerous awards and honors for her writing, including two Booker Prizes, the Arthur C. Clarke Award, the Governor General's Award, the Franz Kafka Prize, Princess of Asturias Awards, and the National Book Critics and PEN Center USA Lifetime Achievement Awards. A number of her works have been adapted for film and television.

Sylvia Plath (October 27, 1932 – February 11, 1963) was an American poet, novelist and short story writer. Born in Boston, Massachusetts, she studied at Smith College and Newnham College, Cambridge before receiving acclaim as a professional poet and writer. She married fellow poet Ted Hughes in 1956 and they lived together first in the United States and then England, having two children together: Frieda and Nicholas. Following a long struggle with depression and a marital separation, Plath committed suicide in 1963. Controversy continues to surround the events of her life and death, as well as her writing and legacy. Plath is credited with advancing the genre of confessional poetry and is best known for her two published collections: The Colossus and Other Poems and Ariel. In 1982, she became the first poet to win a Pulitzer Prize posthumously, for The Collected Poems. She also wrote The Bell Jar, a semi-autobiographical novel published shortly before her death.

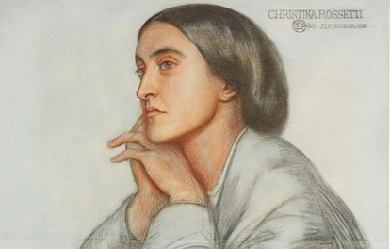

In 1830, Christina Rossetti was born in London, one of four children of Italian parents. Her father was the poet Gabriele Rossetti; her brother Dante Gabriel Rossetti also became a poet and a painter. Rossetti’s first poems were written in 1842 and printed in the private press of her grandfather. In 1850, under the pseudonym Ellen Alleyne, she contributed seven poems to the Pre-Raphaelite journal The Germ, which had been founded by her brother William Michael and his friends.

Maya Angelou (born Marguerite Ann Johnson; April 4, 1928 – May 28, 2014) was an American author and poet. She published seven autobiographies, three books of essays, and several books of poetry, and is credited with a list of plays, movies, and television shows spanning more than fifty years. She received dozens of awards and over thirty honorary doctoral degrees. Angelou is best known for her series of seven autobiographies, which focus on her childhood and early adult experiences. The first, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings (1969), tells of her life up to the age of seventeen, and brought her international recognition and acclaim. Angelou's long list of occupations has included pimp, prostitute, night-club dancer and performer, cast-member of the musical Porgy and Bess, coordinator for Martin Luther King, Jr.'s Southern Christian Leadership Conference, author, journalist in Egypt and Ghana during the days of decolonization, and actor, writer, director, and producer of plays, movies, and public television programs.

Anne Sexton (November 9, 1928, Newton, Massachusetts – October 4, 1974, Weston, Massachusetts) was an American poetese, known for her highly personal, confessional verse. She won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry in 1967. Themes of her poetry include her suicidal tendencies, long battle against depression and various intimate details from her private life, including her relationships with her husband and children. Sexton suffered from severe mental illness for much of her life, her first manic episode taking place in 1954.

Emily Jane Brontë (30 July 1818 – 19 December 1848) was an English novelist and poet, best remembered for her solitary novel, Wuthering Heights, now considered a classic of English literature. Emily was the third eldest of the four surviving Brontë siblings, between the youngest Anne and her brother Branwell. She published under the pen name Ellis Bell. She was born in Thornton, near Bradford in Yorkshire, to Maria Branwell and Patrick Brontë. She was the younger sister of Charlotte Brontë and the fifth of six children. In 1824, the family moved to Haworth, where Emily's father was perpetual curate, and it was in these surroundings that their literary gifts flourished.

Sara Teasdale (August 8, 1884 – January 29, 1933) was an American lyric poet. She was born Sarah Trevor Teasdale in St. Louis, Missouri, and used the name Sara Teasdale Filsinger after her marriage in 1914. She had such poor health for so much of her childhood, home schooled until age 9, that it was only at age 10 that she was well enough to begin school. She started at Mary Institute in 1898, but switched to Hosmer Hall in 1899, graduating in 1903. I Shall Not Care WHEN I am dead and over me bright April Shakes out her rain-drenched hair, Tho' you should lean above me broken-hearted, I shall not care. I shall have peace, as leafy trees are peaceful When rain bends down the bough, And I shall be more silent and cold-hearted Than you are now.

Dorothy Parker (August 22, 1893 – June 7, 1967) was an American poet, short story writer, critic and satirist, best known for her wit, wisecracks, and eye for 20th-century urban foibles. From a conflicted and unhappy childhood, Parker rose to acclaim, both for her literary output in such venues as The New Yorker and as a founding member of the Algonquin Round Table. Following the breakup of the circle, Parker traveled to Hollywood to pursue screenwriting. Her successes there, including two Academy Award nominations, were curtailed as her involvement in left-wing politics led to a place on the Hollywood blacklist. Dismissive of her own talents, she deplored her reputation as a “wisecracker”. Nevertheless, her literary output and reputation for her sharp wit have endured.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning (6 March 1806 – 29 June 1861) was one of the most prominent poets of the Victorian era. Her poetry was widely popular in both England and the United States during her lifetime. A collection of her last poems was published by her husband, Robert Browning, shortly after her death. Barrett Browning opposed slavery and published two poems highlighting the barbarity of slavers and her support for the abolitionist cause. The poems opposing slavery include "The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim's Point" and "A Curse for a Nation"; in the first she describes the experience of a slave woman who is whipped, raped, and made pregnant as she curses the slavers. She declared herself glad that the slaves were "virtually free" when the Emancipation Act abolishing slavery in British colonies was passed in 1833, despite the fact that her father believed that Abolitionism would ruin his business.

Amy Lawrence Lowell (February 9, 1874 – May 12, 1925) was an American poet of the imagist school from Brookline, Massachusetts, who posthumously won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1926. Amy was born into Brookline’s Lowell family, sister to astronomer Percival Lowell and Harvard president Abbott Lawrence Lowell. She never attended college because her family did not consider it proper for a woman to do so. She compensated for this lack with avid reading and near-obsessive book collecting. She lived as a socialite and travelled widely, turning to poetry in 1902 (age 28) after being inspired by a performance of Eleonora Duse in Europe.

Elizabeth Bishop (February 8, 1911 – October 6, 1979) was an American poet, short-story writer, and recipient of the 1976 Neustadt International Prize for Literature. She was the Poet Laureate of the United States from 1949 to 1950, the Pulitzer Prize winner for Poetry in 1956 and the National Book Award winner in 1970.

Erica Jong (née Mann; born March 26, 1942) is an American novelist and poet, known particularly for her 1973 novel Fear of Flying. The book became famously controversial for its attitudes towards female sexuality and figured prominently in the development of second-wave feminism. According to Washington Post, it has sold more than 20 million copies worldwide. Born in New York, she was the second of three daughters of Seymore Mann and Eda Mirsky. Attended New York’s Public High School of Music and Art in the 1950’s where she developed her passion for art and writing. As a student at Barnard College, she edited the Barnard Literary Magazine and created poetry programs for the Columbia University campus radio station.

Felicia Dorothea Hemans (25 September 1793 – 16 May 1835) was an English poet. Her first poems, dedicated to the Prince of Wales, were published in Liverpool in 1808, when she was fourteen, arousing the interest of poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, who briefly corresponded with her. She quickly followed them up with “England and Spain” (1808) and “The Domestic Affections” (1812).

Edna St. Vincent Millay (February 22, 1892 – October 19, 1950) was an American poet and playwright. She received the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1923, the third woman to win the award for poetry, and was also known for her feminist activism. She used the pseudonym Nancy Boyd for her prose work. The poet Richard Wilbur asserted, "She wrote some of the best sonnets of the century."

Celia Laighton Thaxter (June 29, 1835 – August 25, 1894) was an American writer of poetry and stories. She was born in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Thaxter grew up in the Isles of Shoals, first on White Island, where her father, Thomas Laighton, was a lighthouse keeper, and then on Smuttynose and Appledore Islands. When she was sixteen, she married Levi Thaxter and moved to the mainland, residing first in Watertown, Massachusetts at a property his father owned. Celia died suddenly while on Appledore Island. She was buried not far from her cottage, which unfortunately burned in the 1914 fire that destroyed The Appledore House hotel.

Caroline Elizabeth Sarah Norton (22 March 1808 – 15 June 1877) was an English social reformer, and author of the early and mid-nineteenth century. Caroline left her husband in 1836, following which her husband sued her close friend Lord Melbourne, the then Whig Prime Minister, for criminal conversation. The jury threw out the claim, but Caroline was unable to obtain a divorce and was denied access to her three sons. Caroline's intense campaigning led to the passing of the Custody of Infants Act 1839, the Matrimonial Causes Act 1857 and the Married Women's Property Act 1870. Caroline modelled for the fresco of Justice in the House of Lords by Daniel Maclise, who chose her because she was seen by many as a famous victim of injustice.

Louise Elisabeth Glück (born April 22, 1943) is an American poet. She was appointed Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress in 2003. Louise was born in New York City of Hungarian Jewish heritage and grew up on Long Island. Her father, Daniel, an immigrant from Hungary, helped invent and market the X-Acto Knife. She graduated in 1961 from George W. Hewlett High School and went on to attend Sarah Lawrence College and later Columbia University; however, she did not graduate from either of them. Glück won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1993 for her collection The Wild Iris.

Judith Arundell Wright (31 May 1915– 25 June 2000) was an Australian poet, environmentalist and campaigner for Aboriginal land rights. Biography Judith Wright was born in Armidale, New South Wales. The eldest child of Phillip Wright and his first wife, Ethel, she spent most of her formative years in Brisbane and Sydney. Wright was of Cornish ancestry. After the early death of her mother, she lived with her aunt and then boarded at New England Girls’ School after her father’s remarriage in 1929. After graduating, Wright studied Philosophy, English, Psychology and History at the University of Sydney. At the beginning of World War II, she returned to her father’s station to help during the shortage of labour caused by the war. Wright’s first book of poetry, The Moving Image, was published in 1946 while she was working at the University of Queensland as a research officer. Then, she also worked with Clem Christesen on the literary magazine Meanjin. In 1950 she moved to Mount Tamborine, Queensland, with the novelist and abstract philosopher Jack McKinney. Their daughter Meredith was born in the same year. They married in 1962, but Jack was to live only until 1966. In 1966, she published The Nature of Love, her first collection of short stories, through Sun Press, Melbourne. Set mainly in Queensland, they include 'The Vineyard Woman’, 'Eighty Acres’, 'The Dugong’, 'The Weeping Fig’ and 'The Nature of Love’, all first published in The Bulletin. With David Fleay, Kathleen McArthur and Brian Clouston, Wright was a founding member and, from 1964 to 1976, President, of the Wildlife Preservation Society of Queensland. She was the second Australian to receive the Queen’s Gold Medal for Poetry, in 1991. For the last three decades of her life, she lived near the New South Wales town of Braidwood. Allegedly, she had moved to the Braidwood area to be closer to H. C. Coombs, who was based in Canberra. She started to lose her hearing in her mid-20s, and she became completely deaf by 1992. Judith Wright died in Canberra on 25 June 2000, aged 85. Poet and critic Judith Wright was the author of several collections of poetry, including The Moving Image, Woman to Man, The Gateway, The Two Fires, Birds, The Other Half, Magpies, Shadow, Hunting Snake, among others. Her work is noted for a keen focus on the Australian environment, which began to gain prominence in Australian art in the years following World War II. She deals with the relationship between settlers, Indigenous Australians and the bush, among other themes. Wright’s aesthetic centres on the relationship between mankind and the environment, which she views as the catalyst for poetic creation. Her images characteristically draw from the Australian flora and fauna, yet contain a mythic substrata that probes at the poetic process, limitations of language, and the correspondence between inner existence and objective reality. Her poems have been translated into several languages, including Italian, Japanese and Russian. Birds In 2003, the National Library of Australia published an expanded edition of Wright’s collection titled Birds. Most of these poems were written in the 1950s when she was living on Tamborine Mountain in southeast Queensland. Meredith McKinney, Wright’s daughter, writes that they were written at “a precious and dearly-won time of warmth and bounty to counterbalance at last what felt, in contrast, the chilly dearth and difficulty of her earlier years”. McKinney goes on to say that “many of these poems have a newly relaxed, almost conversational tone and rhythm, an often humorous ease and an intimacy of voice that surely reflects the new intimacies and joys of her life”. Despite the joy reflected in the poems, however, they also acknowledge "the experiences of cruelty, pain and death that are inseparable from the lives of birds as of humans... and [turn] a sorrowing a clear-sighted gaze on the terrible damage we have done and continue to do to our world, even as we love it". Environmentalist and social activist Wright was well known for her campaigning in support of the conservation of the Great Barrier Reef and Fraser Island. With some friends, she helped found one of the earliest nature conservation movements. Wright was also an impassioned advocate for the Aboriginal land rights movement. Tom Shapcott, reviewing With Love and Fury, her posthumous collection of selected letters published in 2007, comments that her letter on this topic to the Australian Prime Minister John Howard was “almost brutal in its scorn”. Shortly before her death, she attended a march in Canberra for reconciliation between non-indigenous Australians and the Aboriginal people. Awards * 1976 - Christopher Brennan Award * 1991 - Queen’s Gold Medal for Poetry * 1994 - Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission Poetry Award for Collected Poems Recognition * In June 2006 the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) announced that the new federal electorate in Queensland, which was to be created at the 2007 federal election, would be named Wright in honor of her accomplishments as a “poet and in the areas of arts, conservation and indigenous affairs in Queensland and Australia”. However, in September 2006 the AEC announced it would name the seat after John Flynn, the founder of the Royal Flying Doctor Service, due to numerous objections from people fearing the name Wright may be linked to disgraced former Queensland Labor MP Keith Wright. Under the 2009 redistribution of Queensland, a new seat in southeast Queensland was created and named in Wright’s honour; it was first contested in 2010. * The Judith Wright Centre of Contemporary Arts in Fortitude Valley, Brisbane is named after her. * On 2 January 2008, it was announced that a future suburb in the district of Molonglo Valley, Canberra would be named “Wright”. There is a street in the Canberra suburb of Franklin named after her, as well. Another of the Molonglo Valley suburbs is to be named after Wright’s lover, “Nugget” Coombs.

Dora Maria Sigerson Shorter (16 August 1866– 6 January 1918) was an Irish poet and sculptor, who after her marriage in 1895 wrote under the name Dora Sigerson Shorter. She was born in Dublin, Ireland, the daughter of George Sigerson, a surgeon and writer, and Hester (née Varian), also a writer. She was a major figure of the Irish Literary Revival, publishing many collections of poetry from 1893. Her friends included Katharine Tynan, Rose Kavanagh and Alice Furlong, writers and poets. In 1895 she married Clement King Shorter, an English journalist and literary critic. They lived together in London, until her death at age 51 from undisclosed causes.

Edith Nesbit (married name Edith Bland; 15 August 1858 – 4 May 1924) was an English author and poet; she published her books for children under the name of E. Nesbit. She wrote or collaborated on more than 60 books of fiction for children. She was also a political activist and co-founded the Fabian Society, a socialist organisation later affiliated to the Labour Party.

Alice Walker is a poetese, essayist, and novelist born on February 9, 1944, in Eatonton, Georgia, the eighth and last child of sharecroppers Willie Lee and Minnie Lou Grant Walker. She attended Spelman College and received a B.A. from Sarah Lawrence College. In 1982, she wrote The Color Purple, which won the Pulitzer Prize.

Frances Anne “Fanny” Kemble (27 November 1809– 15 January 1893) was a notable British actress from a theatre family in the early and mid-19th century. She was a well-known and popular writer, whose published works included plays, poetry, eleven volumes of memoirs, travel writing and works about the theatre.

Adrienne Cecile Rich (May 16, 1929– March 27, 2012) was an American poet, essayist and radical feminist. She was called “one of the most widely read and influential poets of the second half of the 20th century”, and was credited with bringing “the oppression of women and lesbians to the forefront of poetic discourse.” Her first collection of poetry, A Change of World, was selected by renowned poet W. H. Auden for the Yale Series of Younger Poets Award. Auden went on to write the introduction to the published volume. She famously declined the National Medal of Arts, protesting the vote by House Speaker Newt Gingrich to end funding for the National Endowment for the Arts. Adrienne Rich was born in Baltimore, Maryland, the elder of two sisters. Her father, renowned pathologist Arnold Rice Rich, was the Chairman of Pathology at The Johns Hopkins Medical School. Her mother, Helen Elizabeth (Jones) Rich, was a concert pianist and a composer. Her father was from a Jewish family, and her mother was Southern Protestant; the girls were raised as Christians. Adrienne Rich’s early poetic influence stemmed from her father who encouraged her to read but also to write her own poetry. Her interest in literature was sparked within her father’s library where she read the work of writers such as Ibsen, Arnold, Blake, Keats, Rossetti, and Tennyson. Her father was ambitious for Adrienne and “planned to create a prodigy.” Adrienne Rich and her younger sister were home schooled by their mother until Adrienne began public education in the fourth grade. The poems Sources and After Dark document her relationship with her father, describing how she worked hard to fulfill her parents’ ambitions for her—moving into a world in which she was expected to excel.

Lucy Maud Montgomery OBE (November 30, 1874– April 24, 1942), publicly known as L. M. Montgomery, was a Canadian author best known for a series of novels beginning in 1908 with Anne of Green Gables. The book was an immediate success. The central character, Anne Shirley, an orphaned girl, made Montgomery famous in her lifetime and gave her an international following. The first novel was followed by a series of sequels with Anne as the central character. Montgomery went on to publish 20 novels as well as 530 short stories, 500 poems, and 30 essays. Most of the novels were set in Prince Edward Island, and locations within Canada’s smallest province became a literary landmark and popular tourist site—namely Green Gables farm, the genesis of Prince Edward Island National Park. She was made an officer of the Order of the British Empire in 1935. Montgomery’s work, diaries and letters have been read and studied by scholars and readers worldwide. Early life Lucy Maud Montgomery was born in Clifton (now New London) in Prince Edward Island on November 30, 1874. Her mother Clara Woolner Macneill Montgomery died of tuberculosis when Maud was 21 months old. Stricken with grief over his wife’s death, Hugh John Montgomery gave custody to Montgomery’s maternal grandparents. Later he moved to Prince Albert, North-West Territories (now Prince Albert, Saskatchewan) when Montgomery was seven. She went to live with her maternal grandparents, Alexander Marquis Macneill and Lucy Woolner Macneill, in the nearby community of Cavendish and was raised by them in a strict and unforgiving manner. Montgomery’s early life in Cavendish was very lonely. Despite having relatives nearby, much of her childhood was spent alone. Montgomery credits this time of her life, in which she created many imaginary friends and worlds to cope with her loneliness, with developing her creativity. Montgomery completed her early education in Cavendish with the exception of one year (1890–1891) during which time she was in Prince Albert with her father and her stepmother, Mary Ann McRae. In November 1890, while in Prince Albert, Montgomery’s first work, a poem entitled “On Cape LeForce,” was published in the Charlottetown paper, The Daily Patriot. She was as excited about this as she was about her return to her beloved Prince Edward Island in 1891. The return to Cavendish was a great relief to her. Her time in Prince Albert was unhappy, for she did not get along with her stepmother and because by, “... Maud’s account, her father’s marriage was not a happy one.” In 1893, following the completion of her grade school education in Cavendish, she attended Prince of Wales College in Charlottetown, and obtained a teacher’s license. She completed the two-year program in one year. In 1895 and 1896, she studied literature at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Writing career, romantic interests, and family life Published books and suitors Upon leaving Dalhousie, Montgomery worked as a teacher in various Prince Edward Island schools. Though she did not enjoy teaching, it afforded her time to write. Beginning in 1897, she began to have her short stories published in magazines and newspapers. Montgomery was prolific and had over 100 stories published from 1897 to 1907. During her teaching years, Montgomery had numerous love interests. As a highly fashionable young woman, she enjoyed “slim, good looks” and won the attention of several young men. In 1889, at 14, Montgomery began a relationship with a Cavendish boy named Nate Lockhart. To Montgomery, the relationship was merely a humorous and witty friendship. It ended abruptly when Montgomery refused his marriage proposal. The early 1890s brought unwelcome advances from John A. Mustard and Will Pritchard. Mustard, her teacher, quickly became her suitor; he tried to impress her with his knowledge of religious matters. His best topics of conversation were his thoughts on Predestination and “other dry points of theology”, which held little appeal for Montgomery. During the period when Mustard’s interest became more pronounced, Montgomery found a new interest in Will Pritchard, the brother of her friend Laura Pritchard. This friendship was more amiable but, again, he felt more for Montgomery than she did for him. When Pritchard sought to take their friendship further, Montgomery resisted. Montgomery refused both marriage proposals; the former was too narrow-minded, and the latter was merely a good chum. She ended the period of flirtation when she moved to Prince Edward Island. However, she and Pritchard did continue to correspond for over six years, until Pritchard caught influenza and died in 1897. In 1897, Montgomery accepted the proposal of Edwin Simpson, who was a student in French River near Cavendish. Montgomery wrote that she accepted his proposal out of a desire for “love and protection” and because she felt her prospects were rather low. While teaching in Lower Bedeque, she had a brief but passionate romantic attachment to Herman Leard, a member of the family with which she boarded. In 1898, after much unhappiness and disillusionment, Montgomery broke off her engagement to Simpson. Montgomery no longer sought romantic love. In 1898, Montgomery moved back to Cavendish to live with her widowed grandmother. For a nine-month period between 1901 and 1902, she worked in Halifax as a substitute proofreader for the newspapers Morning Chronicle and The Daily Echo. Montgomery was inspired to write her first books during this time on Prince Edward Island. Until her grandmother’s death in March 1911, Montgomery stayed in Cavendish to take care of her. This coincided with a period of considerable income from her publications. Although she enjoyed this income, she was aware that “marriage was a necessary choice for women in Canada.” Marriage and family In 1908, Montgomery published her first book, Anne of Green Gables. An immediate success, it established Montgomery’s career, and she would write and publish material (Including numerous sequels to Anne) continuously for the rest of her life. Shortly after her grandmother’s death in 1911, she married Ewen (spelled in her notes and letters as “Ewan”) Macdonald (1870–1943), a Presbyterian minister, and they moved to Ontario where he had taken the position of minister of St. Paul’s Presbyterian Church, Leaskdale in present-day Uxbridge Township, also affiliated with the congregation in nearby Zephyr. Montgomery wrote her next eleven books from the Leaskdale manse. The structure was subsequently sold by the congregation and is now the Lucy Maud Montgomery Leaskdale Manse Museum. The Macdonalds had three sons; the second was stillborn. The great increase of Montgomery’s writings in Leaskdale is the result of her need to escape the hardships of real life. Montgomery underwent several periods of depression while trying to cope with the duties of motherhood and church life and with her husband’s attacks of religious melancholia (endogenous major depressive disorder) and deteriorating health: "For a woman who had given the world so much joy, [life] was mostly an unhappy one." For much of her life, writing was her one great solace. Also, during this time, Montgomery was engaged in a series of "acrimonious, expensive, and trying lawsuits with the publisher L.C. Page, that dragged on until she finally won in 1929.” Montgomery stopped writing about Anne in about 1920, writing in her journal that she had tired of the character. She preferred instead to create books about other young, female characters, feeling that her strength was writing about characters who were either very young or very old. Other series written by Montgomery include the “Emily” and “Pat” books, which, while successful, did not reach the same level of public acceptance as the “Anne” volumes. She also wrote a number of stand-alone novels, which were also generally successful, if not as successful as her Anne books. Later life In 1926, the family moved into the Norval Presbyterian Charge, in present-day Halton Hills, Ontario, where today the Lucy Maud Montgomery Memorial Garden can be seen from Highway 7. In 1935, upon her husband’s retirement, Montgomery moved to Swansea, Ontario, a suburb of Toronto, buying a house which she named Journey’s End, situated on Riverside Drive along the east bank of the Humber River. Montgomery continued to write, and (in addition to writing other material) returned to writing about Anne after a 15-year hiatus, filling in previously unexplored gaps in the chronology she had developed for the character. She published Anne of Windy Poplars in 1936 and Anne of Ingleside in 1939. Jane of Lantern Hill, a non-Anne novel, was also composed around this time and published in 1937. In the last year of her life, Montgomery completed what she intended to be a ninth book featuring Anne, titled The Blythes Are Quoted. It included fifteen short stories (many of which were previously published) that she revised to include Anne and her family as mainly peripheral characters; forty-one poems (most of which were previously published) that she attributed to Anne and to her son Walter, who died as a soldier in the Great War; and vignettes featuring the Blythe family members discussing the poems. The book was delivered to Montgomery’s publisher on the day of her death, but for reasons unexplained, the publisher declined to issue the book at the time. Montgomery scholar Benjamin Lefebvre speculates that the book’s dark tone and anti-war message (Anne speaks very bitterly of WWI in one passage) may have made the volume unsuitable to publish in the midst of the second world war. An abridged version of this book, which shortened and reorganized the stories and omitted all the vignettes and all but one of the poems, was published as a collection of short stories called The Road to Yesterday in 1974, more than 30 years after the original work had been submitted. A complete edition of The Blythes Are Quoted, edited by Benjamin Lefebvre, was finally published in its entirety by Viking Canada in October 2009, more than 67 years after it was composed. Death Montgomery died on April 24, 1942. A note was found beside her bed, reading, in part, “I have lost my mind by spells and I do not dare think what I may do in those spells. May God forgive me and I hope everyone else will forgive me even if they cannot understand. My position is too awful to endure and nobody realizes it. What an end to a life in which I tried always to do my best.” Montgomery died from coronary thrombosis in Toronto. However, it was revealed by her granddaughter, Kate Macdonald Butler, in September 2008 that Montgomery suffered from depression– possibly as a result of caring for her mentally ill husband for decades– and may have taken her own life via a drug overdose. But, there is another point of view. According to Mary Rubio, who wrote a biography of Montgomery, Lucy Maud Montgomery: The Gift of Wings (2008), the message may have been intended to be a journal entry as part of a journal that can no longer be found, rather than a simple suicide note. During her lifetime, Montgomery published 20 novels, over 500 short stories, an autobiography, and a book of poetry. Aware of her fame, by 1920 Montgomery began editing and recopying her journals, presenting her life as she wanted it remembered. In doing so certain episodes were changed or omitted. She was buried at the Cavendish Community Cemetery in Cavendish following her wake in the Green Gables farmhouse and funeral in the local Presbyterian church. Legacy Collections The L. M. Montgomery Institute, founded in 1993, at the University of Prince Edward Island, promotes scholarly inquiry into the life, works, culture, and influence of L. M. Montgomery and coordinates most of the research and conferences surrounding her work. The Montgomery Institute collection consists of novels, manuscripts, texts, letters, photographs, sound recordings and artifacts and other Montgomery ephemera. Her major collections are archived at the University of Guelph. The first biography of Montgomery was The Wheel of Things: A Biography of L. M. Montgomery (1975), written by Mollie Gillen. Dr. Gillen also discovered over 40 of Montgomery’s letters to her pen-friend George Boyd MacMillan in Scotland and used them as the basis for her work. Beginning in the 1980s, her complete journals, edited by Mary Rubio and Elizabeth Waterston, were published by the Oxford University Press. From 1988–95, editor Rea Wilmshurst collected and published numerous short stories by Montgomery. Most of her essays, along with interviews with Montgomery, commentary on her work, and coverage of her death and funeral, appear in Benjamin Lefebvre’s The L. M. Montgomery Reader, Volume 1: A Life in Print (2013). Despite the fact that Montgomery published over twenty books, “she never felt she achieved her one 'great’ book”. Her readership, however, has always found her characters and stories to be among the best in fiction. Mark Twain said Montgomery’s Anne was “the dearest and most moving and delightful child since the immortal Alice". Montgomery was honoured by being the first female in Canada to be named a fellow of the Royal Society of Arts in England and by being invested in the Order of the British Empire in 1935. However, her fame was not limited to Canadian audiences. Anne of Green Gables became a success worldwide. For example, every year, thousands of Japanese tourists “make a pilgrimage to a green-gabled Victorian farmhouse in the town of Cavendish on Prince Edward Island”. In 2012, the original novel Anne of Green Gables was ranked number nine among all-time best children’s novels in a survey published by School Library Journal, a monthly with primarily U.S. audience. The British public ranked it number 41 among all novels in The Big Read, a 2003 BBC survey to determine the “nation’s best-loved novel”. Landmarked places Montgomery’s home of Leaskdale Manse in Ontario, and the area surrounding Green Gables and her Cavendish home in Prince Edward Island, have both been designated National Historic Sites. Montgomery herself was designated a Person of National Historic Significance by the Government of Canada in 1943. Bala’s Museum in Bala, Ontario, is a house museum established in 1992. Officially it is “Bala’s Museum with Memories of Lucy Maud Montgomery”, for Montgomery and her family stayed in the boarding house during a July 1922 holiday that inspired her novel The Blue Castle (1926). The museum hosts some events pertaining to Montgomery or her fiction, including re-enactment of the holiday visit. Honours and awards Montgomery was honoured by Britain’s King George V as an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE), as there were no Canadian orders, decorations or medals for civilians until the 1970s. Montgomery was named a National Historic Person in 1943 by the Canadian federal government. Her Ontario residence was designated a National Historic Site (NHS) in 1997 (Leaskdale Manse NHS), while the place that inspired her famous novels, Green Gables, was designated “L. M. Montgomery’s Cavendish NHS” in 2004. On May 15, 1975, the Post Office Department issued a stamp to “Lucy Maud Montgomery, Anne of Green Gables” designed by Peter Swan and typographed by Bernard N. J. Reilander. The 8¢ stamps are perforated 13 and were printed by Ashton-Potter Limited. A pair of stamps was issued in 2008 by Canada Post, marking the centennial of the publication of Montgomery’s classic first novel. The City of Toronto named a park for her (Lucy Maud Montgomery Park) and in 1983 placed a historical marker there near the house where she lived from 1935 until her death in 1942. On November 30, 2015 (her 141st birthday), Google honoured Lucy Maud Montgomery with a Google Doodle published in twelve countries.

Amy Judith Levy (10 November 1861– 10 September 1889) was a British essayist, poet, and novelist best remembered for her literary gifts; her experience as the first Jewish woman at Cambridge University and as a pioneering woman student at Newnham College, Cambridge; her feminist positions; her friendships with others living what came later to be called a “new woman” life, some of whom were lesbians; and her relationships with both women and men in literary and politically activist circles in London during the 1880s. Biography Levy was born in Clapham, an affluent district of London, on November 10, 1861, to Lewis and Isobel Levy. She was the second of seven children born into a Jewish family with a “casual attitude toward religious observance” who sometimes attended a Reform synagogue in Upper Berkeley Street. As an adult, Levy continued to identify herself as Jewish and wrote for The Jewish Chronicle. Levy showed interest in literature from an early age. At 13, she wrote a criticism of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s feminist work Aurora Leigh; at 14, Levy’s first poem, “Ida Grey: A Story of Woman’s Sacrifice”, was published in the journal Pelican. Her family was supportive of women’s education and encouraged Amy’s literary interests; in 1876, she was sent to Brighton and Hove High School and later studied at Newnham College, Cambridge. Levy was the first Jewish student at Newnham when she arrived in 1879 but left before her final year without taking her exams. Her circle of friends included Clementina Black, Dollie Radford, Eleanor Marx (daughter of Karl Marx), and Olive Schreiner. While travelling in Florence in 1886, Levy met Vernon Lee, a fiction writer and literary theorist six years her senior, and fell in love with her. Both women would go on to write works with themes of sapphic love. Lee inspired Levy’s poem “To Vernon Lee.” Literary career The Romance of a Shop (1888), Levy’s first novel, is regarded as an early “New Woman” novel and depicts four sisters who experience the difficulties and opportunities afforded to women running a business in 1880s London, Levy wrote her second novel, Reuben Sachs (1888), to fill the literary need for “serious treatment... of the complex problem of Jewish life and Jewish character”, which she identified and discussed in her 1886 article “The Jew in Fiction.” Levy wrote stories, essays, and poems for popular or literary periodicals; the stories “Cohen of Trinity” and “Wise in Their Generation”, both published in Oscar Wilde’s magazine The Woman’s World, are among her most notable. In 1886, Levy began writing a series of essays on Jewish culture and literature for The Jewish Chronicle, including The Ghetto at Florence, The Jew in Fiction, Jewish Humour, and Jewish Children. Levy’s works of poetry, including the daring A Ballad of Religion and Marriage, reveal her feminist concerns. Xantippe and Other Verses (1881) includes “Xantippe”, a poem in the voice of Socrates’s wife; the volume A Minor Poet and Other Verse (1884) includes more dramatic monologues as well as lyric poems. Her final book of poems, A London Plane-Tree (1889), contains lyrics that are among the first to show the influence of French symbolism. Suicide Levy suffered from episodes of major depression from an early age. In her later years, her depression worsened in connection to her distress surrounding her romantic relationships and her awareness of her growing deafness. Two months away from her 28th birthday, she committed suicide at the residence of her parents... [at] Endsleigh Gardens by inhaling carbon monoxide. Oscar Wilde wrote an obituary for her in Women’s World in which he praised her gifts.

Lesbia Harford (1891–1927) was an Australian poet, novelist and political activist. Life Lesbia Venner Keogh was the first child of Edmund Joseph Keogh and Beatrice Eleanor Moore, great-great-granddaughter of an Earl of Drogheda. Lesbia was born at Brighton, Victoria, on 9 April 1891. From 1893 to 1900, the family lived at “Wangrabel”, 6 Horsburgh Grove, Armadale (the house still stands today). Her father left home for Western Australia when his real estate business failed about 1900. She and her three siblings were raised by their mother, who took genteel jobs, begged handouts from Keogh relations and took in boarders. Lesbia was educated at the Sacré Cœur School at “Clifton”, Malvern, Victoria; Mary’s Mount school at Ballarat, Victoria; and the University of Melbourne, where she graduated LL.B. in 1916. She was one of the university’s few women students and one of its few opponents of Australia’s part in the First World War. Her brother, Esmond Venner (Bill) Keogh (1895–1970), became a prominent medical administrator and cancer researcher. Lesbia advocated free love in human relations. She herself formed lifelong parallel attachments to both men and women, most notably to Katie Lush, philosophy tutor at Ormond College. Becoming interested in social questions, she worked in textile and clothing factories to gain first hand knowledge of the conditions under which women worked. She became state vice-president of the Federated Clothing and Allied Trades Union. She campaigned strongly against conscription in World War I. She was a friend of Norman Jeffrey and lover of Guido Baracchi, founding members of the Communist Party of Australia (but which she never joined). In Sydney Lesbia sang her poems to Guido as they crossed the harbour on the Manly ferry. In 1918 she moved to Sydney to campaign for the release of the Sydney Twelve, members of the Industrial Workers of the World (the Wobblies) arrested and charged with treason, arson, sedition and forgery. She worked in clothing factories and as a university coach. She was also for a time a Fairfax housemaid (glimpsed in the poem “Miss Mary Fairfax”). She married Patrick John (Pat) Harford, sometime soldier, clicker in his uncle’s Fitzroy boot factory and a fellow Wobbly, in 1920. They shared an interest in painting and aesthetics. He was feckless and alcoholic but Pat wasn’t Pat last night at all. He was the rain,— The Spring,— Young Dionysus, white and warm,— Lilac and everything. They returned to her mother’s boarding house in Elsternwick, Melbourne in the early Twenties. Pat worked for the post-impressionist painter William Frater and himself became a painter under Frater’s influence, later moving towards modernism and cubism. The Harfords had no children and were estranged in the last years of Lesbia’s life. Some writers claim they were divorced but there is no documentary evidence of it. In 1926 Lesbia completed her articles with a Melbourne law firm. Authors agree on her always-delicate health but not on the cause: a severe attack of rheumatic fever while a young child (Serle); tuberculosis (Lamb); born with a heart problem that prevented her blood oxygenating (Sparrow). She often had to walk slowly. Her lips were sometimes quite blue. She died aged 36 of lung and heart failure in St Vincent’s Hospital on 5 July 1927. Writing Harford had begun writing verse in 1910, and in May 1921 Birth, a small poetry magazine published at Melbourne, gave the whole of one number to a selection from her poems. Harford’s 59-page The Law Relating to Hire Purchase in Australia and New Zealand, “just written for the money it will bring”, was published in 1923. In 1927 three of her poems were included in Serle’s An Australasian Anthology. The critic H.M. Green wrote “She has written some of the best lyrics among today’s and certainly, I would say, the best love lyrics written out here.” Mrs Keogh thought Lesbia’s writing was “beautiful” and in 1939 was still trying to get her novel and more poems published. In 1941 a small volume (54 poems) of The Poems of Lesbia Harford, edited by Nettie Palmer for Melbourne University Press, “revealed a poet of originality and charm.” In 1985 a much larger selection of poems appeared, edited by Marjorie Pizer and Drusilla Modjeska with a long introduction by Modjeska, acknowledging that some of Harford’s sexual relations were with women and much of her love poetry was addressed to them. Les Murray published 86 of these poems and a page of biography in a 2005 anthology. Lehmann and Gray’s obese 2011 Australian poetry since 1788 prints only thirteen poems (given “as much space as Brennan”) but provides a scholarly and detailed critical biography. The biggest selection in print is Collected Poems, which has 250 poems, a two-page foreword by Les Murray and an eight-page introduction by the editor, Oliver Dennis. Harford wrote a long-lost 190-page novel, The Invaluable Mystery, eventually published in 1987 with a foreword by Helen Garner and an introduction by Richard Nile and Robert Darby. Papers For decades it was thought that “On her death her father took custody of her notebooks and they were lost when his shack was destroyed by fire” but this is now known to be false. All known Harford poems are in the exercise books in Folders 1–3 of the Marjorie Pizer Papers, Mitchell Library, NSW, MLMSS 7428. Another ten folders collect manuscripts, typescript, letters and photos relating mainly to publication of her work. The typescript of The Invaluable Mystery is in the National Archive of Australia, Canberra, Series A699, control 1958/3640, barcode 278433. Legacy The political rock band Redgum recorded part of Harford’s poem “Periodicity” set to music as “Women in Change” on their 1980 album Virgin Ground. In Melbourne, the Victorian Women Lawyers’ biennial Lesbia Harford Oration, given by an eminent speaker on an issue of importance for women, is named in her honour. In 1991, the Playbox Theatre Company Melbourne presented Earthly Paradise; a Picture of Lesbia Harford, by the playwright Darryl Emmerson. This play was also published by Currency Press, Sydney.

Charlotte Turner Smith (4 May 1749– 28 October 1806) was an English Romantic poet and novelist. She initiated a revival of the English sonnet, helped establish the conventions of Gothic fiction, and wrote political novels of sensibility. Smith was born into a wealthy family and received a typical education for a woman during the late 18th century. However, her father’s reckless spending forced her to marry early. In a marriage that she later described as prostitution, she was given by her father to the violent and profligate Benjamin Smith. Their marriage was deeply unhappy, although they had twelve children together. Charlotte joined Benjamin in debtor’s prison, where she wrote her first book of poetry, Elegiac Sonnets. Its success allowed her to help pay for Benjamin’s release. Benjamin’s father attempted to leave money to Charlotte and her children upon his death, but legal technicalities prevented her from ever acquiring it. Charlotte Smith eventually left Benjamin and began writing to support their children. Smith’s struggle to provide for her children and her frustrated attempts to gain legal protection as a woman provided themes for her poetry and novels; she included portraits of herself and her family in her novels as well as details about her life in her prefaces. Her early novels are exercises in aesthetic development, particularly of the Gothic and sentimentality. “The theme of her many sentimental and didactic novels was that of a badly married wife helped by a thoughtful sensible lover” (Smith’s entry in British Authors Before 1800: A Biographical Dictionary Ed. Stanley Kunitz and Howard Haycraft. New York: H.W. Wilson, 1952. pg. 478.) Her later novels, including The Old Manor House, often considered her best, support the ideals of the French Revolution. Smith was a successful writer, publishing ten novels, three books of poetry, four children’s books, and other assorted works, over the course of her career. She always saw herself as a poet first and foremost, however, as poetry was considered the most exalted form of literature at the time. Scholars credit Smith with transforming the sonnet into an expression of woeful sentiment that would pave the way for poets such as Coleridge, Wordsworth, Shelly and Keats. Smith’s poetry and prose was praised by contemporaries such as Romantic poets William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge as well as novelist Walter Scott. Coleridge, in 1796, even remarked that “those sonnets appear to me the most exquisite, in which moral Sentiments, Affections, or Feelings, are deduced from, and associated with the scenery of Nature”. After 1798, Smith’s popularity waned and by 1803 she was destitute and ill—she could barely hold a pen. She had to sell her books to pay off her debts. In 1806, Smith died. Largely forgotten by the middle of the 19th century, her works have now been republished and she is recognized as an important Romantic writer. Early life Smith was born on 4 May 1749 in London and baptized on 12 June; she was the oldest child of well-to-do Nicholas Turner and Anna Towers. Her two younger siblings, Nicholas and Catherine Ann, were born within the next five years. Smith’s childhood was shaped by her mother’s early death (probably in giving birth to Catherine) and her father’s reckless spending. After losing his wife, Nicholas Turner travelled and the children were raised by Lucy Towers, their maternal aunt (when exactly their father returned is unknown). At the age of six, Charlotte went to school in Chichester and took drawing lessons from the painter George Smith. Two years later, she, her aunt, and her sister moved to London and she attended a girls school in Kensington where she learned dancing, drawing, music, and acting. She loved to read and wrote poems, which her father encouraged. She even submitted a few to the Lady’s Magazine for publication, but they were not accepted. Marriage and first publication Smith’s father encountered financial difficulties upon his return to England and he was forced to sell some of the family’s holdings and to marry the wealthy Henrietta Meriton in 1765. Smith entered society at the age of twelve, leaving school and being tutored at home. On 23 February 1765, at the age of fifteen, she married Benjamin Smith, the son of Richard Smith, a wealthy West Indian merchant and a director of the East India Company. The proposal was accepted for her by her father; forty years later, Smith condemned her father’s action, which she wrote had turned her into a “legal prostitute”. Smith’s marriage was unhappy. She detested living in commercial Cheapside (the family later moved to Southgate and Tottenham) and argued with her in-laws, who she believed were unrefined and uneducated. They, in turn, mocked her for spending time reading, writing, and drawing. Even worse, Benjamin proved to be violent, unfaithful, and profligate. Only her father-in-law, Richard, appreciated her writing abilities, although he wanted her to use them to further his business interests. Richard Smith owned plantations in Barbados and he and his second wife brought five slaves to England, who, along with their descendants, were included as part of the family property in his will. Although Charlotte Smith later argued against slavery in works such as The Old Manor House (1793) and “Beachy Head”, she herself benefited from the income and slave labor of Richard Smith’s plantations. In 1766, Charlotte and Benjamin had their first child, who died the next year just days after the birth of their second, Benjamin Berney (1767–77). Between 1767 and 1785, the couple had ten more children: William Towers (born 1768), Charlotte Mary (born c. 1769), Braithwaite (born 1770), Nicholas Hankey (1771–1837), Married Anni Petroose (1779–1843), Charles Dyer (born 1773), Anna Augusta (1774–94), Lucy Eleanor (born 1776), Lionel (1778–1842), Harriet (born c. 1782), and George (born c. 1785). Only six of Smith’s children survived her. Smith assisted in the family business that her husband had abandoned by helping Richard Smith with his correspondence. She persuaded Richard to set Benjamin up as a gentleman farmer in Hampshire and lived with him at Lys Farm from 1774 until 1783. Worried about Charlotte’s future and that of his grandchildren and concerned that his son would continue his irresponsible ways, Richard Smith willed the majority of his property to Charlotte’s children. However, because he had drawn up the will himself, the documents contained legal problems. The inheritance, originally worth nearly £36,000, was tied up in chancery after his death in 1776 for almost forty years. Smith and her children saw little of it. (It has been proposed that this real case may have inspired the famous fictional case of Jarndyce and Jarndyce, in Dickens’s Bleak House.) In fact, Benjamin illegally spent at least a third of the legacy and ended up in King’s Bench Prison in December 1783. Smith moved in with him and it was in this environment that she wrote and published her first work, Elegiac Sonnets (1784). Elegiac Sonnets achieved instant success, allowing Charlotte to pay for their release from prison. Smith’s sonnets helped initiate a revival of the form and granted an aura of respectability to her later novels (poetry was considered the highest art form at the time). Smith revised Elegiac Poems several times over the years, eventually creating a two-volume work. Novelist After Benjamin Smith was released from prison, the entire family moved to Dieppe, France to avoid further creditors. Charlotte returned to negotiate with them, but failed to come to an agreement. She went back to France and in 1784 began translating works from French into English. In 1787 she published The Romance of Real Life, consisting of translated selections from François Gayot de Pitaval’s trials. She was forced to withdraw her other translation, Manon Lescaut, after it was argued that the work was immoral and plagiarized. In 1786, she published it anonymously. In 1785, the family returned to England and moved to Woolbeding House near Midhurst, Sussex. Smith’s relationship with her husband did not improve and on 15 April 1787, after twenty-two years of marriage, she left him. She wrote that she might “have been contented to reside in the same house with him”, had not “his temper been so capricious and often so cruel” that her “life was not safe”. When Charlotte left Benjamin, she did not secure a legal agreement that would protect her profits—he would have access to them under English primogeniture laws. Smith knew that her children’s future rested on a successful settlement of the lawsuit over her father-in-law’s will, therefore she made every effort to earn enough money to fund the suit and retain the family’s genteel status. Smith claimed the position of gentlewoman, signing herself “Charlotte Smith of Bignor Park” on the title page of Elegiac Sonnets. All of her works were published under her own name, “a daring decision” for a woman at the time. Her success as a poet allowed her to make this choice. Throughout her career, Smith identified herself as a poet. Although she published far more prose than poetry and her novels brought her more money and fame, she believed poetry would bring her respectability. As Sarah Zimmerman claimed in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, “She prized her verse for the role it gave her as a private woman whose sorrows were submitted only reluctantly to the public.” After separating from her husband, Smith moved to a town near Chichester and decided to write novels, as they would make her more money than poetry. Her first novel, Emmeline (1788), was a success, selling 1500 copies within months. She wrote nine more novels in the next ten years: Ethelinde (1789), Celestina (1791), Desmond (1792), The Old Manor House (1793), The Wanderings of Warwick (1794), The Banished Man (1794), Montalbert (1795), Marchmont (1796), and The Young Philosopher (1798). Smith began her career as a novelist during the 1780s at a time when women’s fiction was expected to focus on romance and to foreground “a chaste and flawless heroine subjected to repeated melodramatic distresses until reinstated in society by the virtuous hero”. Although Smith’s novels employed this structure, they also incorporated political commentary, particularly support of the French Revolution, through the voices of male characters. At times, she challenged the typical romance plot by including “narratives of female desire” or “tales of females suffering despotism”. Smith’s novels contributed to the development of Gothic fiction and the novel of sensibility. Smith’s novels are autobiographical. While a common device at the time, Antje Blank writes in The Literary Encyclopedia, “few exploited fiction’s potential of self-representation with such determination as Smith”. For example, Mr. and Mrs. Stafford in Emmeline are portraits of Charlotte and Benjamin. The prefaces to Smith’s novels told the story of her own struggles, including the deaths of several of her children. According to Zimmerman, "Smith mourned most publicly for her daughter Anna Augusta, who married an émigré... and died aged twenty in 1795." Smith’s prefaces positioned her as both a suffering sentimental heroine as well as a vocal critic of the laws that kept her and her children in poverty. Smith’s experiences prompted her to argue for legal reforms that would grant women more rights, making the case for these reforms through her novels. Smith’s stories showed the “legal, economic, and sexual exploitation” of women by marriage and property laws. Initially readers were swayed by her arguments and writers such as William Cowper patronized her. However, as the years passed, readers became exhausted by Smith’s stories of struggle and inequality. Public opinion shifted towards the view of poet Anna Seward, who argued that Smith was “vain” and “indelicate” for exposing her husband to “public contempt”. Smith moved frequently due to financial concerns and declining health. During the last twenty years of her life, she lived in: Chichester, Brighton, Storrington, Bath, Exmouth, Weymouth, Oxford, London, Frant, and Elstead. She eventually settled at Tilford, Surrey. Smith became involved with English radicals while she was living in Brighton from 1791 to 1793. Like them, she supported the French Revolution and its republican principles. Her epistolary novel Desmond tells the story of a man who journeys to revolutionary France and is convinced of the rightness of the revolution and contends that England should be reformed as well. The novel was published in June 1792, a year before France and England went to war and before the Reign of Terror began, which shocked the British public, turning them against the revolutionaries. Like many radicals, Smith criticized the French, but she still endorsed the original ideals of the revolution. In order to support her family, Smith had to sell her works, thus she was eventually forced to, as Blank claims, “tone down the radicalism that had characterised the authorial voice in Desmond and adopt more oblique techniques to express her libertarian ideals”. She therefore set her next novel, The Old Manor House (1793), during the American Revolutionary War, which allowed her to discuss democratic reform without directly addressing the French situation. However, in her last novel, The Young Philosopher (1798), Smith wrote a final piece of “outspoken radical fiction”. Smith’s protagonist leaves Britain for America, as there is no hope for a reform in Britain. The Old Manor House is "frequently deemed [Smith’s] best" novel for its sentimental themes and development of minor characters. Novelist Walter Scott labeled it as such and poet and critic Anna Laetitia Barbauld chose it for her anthology of The British Novelists (1810). As a successful novelist and poet, Smith communicated with famous artists and thinkers of the day, including musician Charles Burney (father of Frances Burney), poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, scientist and poet Erasmus Darwin, lawyer and radical Thomas Erskine, novelist Mary Hays, playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan, and poet Robert Southey. A wide array of periodicals reviewed her works, including the Anti-Jacobin Review, the Analytical Review, the British Critic, The Critical Review, the European Magazine, the Gentleman’s Magazine, the Monthly Magazine, and the Universal Magazine. Smith earned the most money between 1787 and 1798, after which she was no longer as popular; several reasons have been suggested for the public’s declining interest in Smith, including “a corresponding erosion of the quality of her work after so many years of literary labour, an eventual waning of readerly interest as she published, on average, one work per year for twenty-two years, and a controversy that attached to her public profile” as she wrote about the French revolution. Both radical and conservative periodicals criticized her novels about the revolution. Her insistence on pursuing the lawsuit over Richard Smith’s inheritance lost her several patrons. Also, her increasingly blunt prefaces made her less appealing to the public. In order to continue earning money, Smith began writing in less politically charged genres. She published a collection of tales, Letters of a Solitary Wanderer (1801–02) and the play What Is She? (1799, attributed). Her most successful new foray was into children’s literature: Rural Walks (1795), Rambles Farther (1796), Minor Morals (1798), and Conversations Introducing Poetry (1804). She also wrote two volumes of a history of England (1806) and A Natural History of Birds (1807, posthumous). She also returned to writing poetry and Beachy Head and Other Poems (1807) was published posthumously. Publishers did not pay as much for these works, however, and by 1803, Smith was poverty-stricken. She could barely afford food and had no coal. She even sold her beloved library of 500 books in order to pay off debts, but feared being sent to jail for the remaining £20. Illness and death Smith complained of gout for many years (it was probably rheumatoid arthritis), which made it increasingly difficult and painful for her to write. By the end of her life, it had almost paralyzed her. She wrote to a friend that she was “literally vegetating, for I have very little locomotive powers beyond those that appertain to a cauliflower”. On 23 February 1806, her husband died in a debtors’ prison and Smith finally received some of the money he owed her, but she was too ill to do anything with it. She died a few months later, on 28 October 1806, at Tilford and was buried at Stoke Church, Stoke Park, near Guildford. The lawsuit over her father-in-law’s estate was settled seven years later, on 22 April 1813, more than thirty-six years after Richard Smith’s death. Legacy Stuart Curran, the editor of Smith’s poems, has written that Smith is “the first poet in England whom in retrospect we would call Romantic”. She helped shape the “patterns of thought and conventions of style” for the period. Romantic poet William Wordsworth was the most affected by her works. He said of Smith in the 1830s that she was “a lady to whom English verse is under greater obligations than are likely to be either acknowledged or remembered”. By the second half of the 19th century, Smith was largely forgotten. Smith’s novels were republished again at the end of the 20th century, and “critics interested in the period’s women poets and prose writers, the Gothic novel, the historical novel, the social problem novel, and post-colonial studies” have argued for her significance as a writer. They looked to the contemporary documentation of her importance, discovering that she helped to revitalize the English sonnet, a fact recognized by Coleridge and others. Scott wrote that she “preserves in her landscapes the truth and precision of a painter” and poet and Barbauld claimed that Smith was the first to include sustained natural description in novels. It was not until 2008 however, that Smith’s entire prose collection became available to the general public. The edition contains each novel, the children’s stories and rural walks.