Info

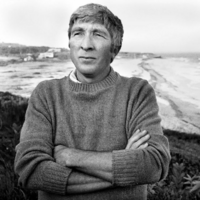

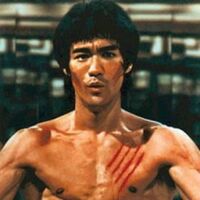

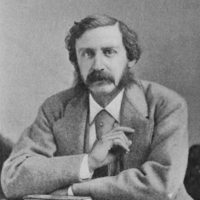

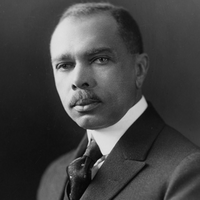

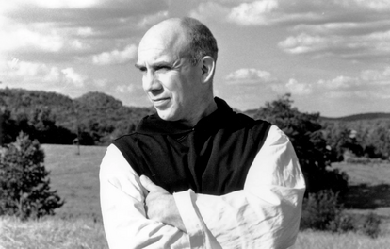

William Edgar Stafford (January 17, 1914 – August 28, 1993) was an American poet and pacifist, and the father of poet and essayist Kim Stafford. He was appointed the twentieth Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress in 1970. Early years Stafford was born in Hutchinson, Kansas, the oldest of three children in a highly literate family. During the Depression, his family moved from town to town in an effort to find work for his father. Stafford helped contribute to family income by delivering newspapers, working in sugar beet fields, raising vegetables, and working as an electrician's apprentice. During this time he had a near death experience in a local swimming hole. He graduated from high school in the town of Liberal, Kansas in 1933. After attending junior college, he received a B.A. from the University of Kansas in 1937. He was drafted into the United States armed forces in 1941, while pursuing his master's degree at the University of Kansas, but declared himself a conscientious objector. As a registered pacifist, he performed alternative service from 1942 to 1946 in the Civilian Public Service camps. The work consisted of forestry and soil conservation work in Arkansas, California, and Illinois for $2.50 per month. While working in California in 1944, he met and married Dorothy Hope Frantz with whom he later had four children (Bret, who died in 1988; Kim, writer; Kit, artist; Barbara, artist). He received his M.A. from the University of Kansas in 1947. His master's thesis, the prose memoir Down In My Heart, was published in 1948 and described his experience in the forest service camps. That same year he moved to Oregon to teach at Lewis & Clark College. In 1954, he received a Ph.D. from the University of Iowa. Stafford taught for one academic year (1955–1956) in the English department at Manchester College in Indiana, a college affiliated with the Church of the Brethren where he had received training during his time in Civilian Public Service. The following year (1956–57), he taught at San Jose State in California, and the next year returned to the faculty of Lewis & Clark. Career One striking feature of his career is its late start. Stafford was 46 years old when his first major collection of poetry was published, Traveling Through the Dark, which won the 1963 National Book Award for Poetry. The title poem is one of his best known works. It describes encountering a recently killed doe on a mountain road. Before pushing the doe into a canyon, the narrator discovers that she was pregnant and the fawn inside is still alive. Stafford had a quiet daily ritual of writing and his writing focuses on the ordinary. His gentle quotidian style has been compared to Robert Frost. Paul Merchant writes, "His poems are accessible, sometimes deceptively so, with a conversational manner that is close to everyday speech. Among predecessors whom he most admired are William Wordsworth, Thomas Hardy, Walt Whitman, and Emily Dickinson." His poems are typically short, focusing on the earthy, accessible details appropriate to a specific locality. Stafford said this in a 1971 interview: I keep following this sort of hidden river of my life, you know, whatever the topic or impulse which comes, I follow it along trustingly. And I don't have any sense of its coming to a kind of crescendo, or of its petering out either. It is just going steadily along. Stafford was a close friend and collaborator with poet Robert Bly. Despite his late start, he was a frequent contributor to magazines and anthologies and eventually published fifty-seven volumes of poetry. James Dickey called Stafford one of those poets "who pour out rivers of ink, all on good poems."[6] He kept a daily journal for 50 years, and composed nearly 22,000 poems, of which roughly 3,000 were published. In 1970, he was named Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress, a position that is now known as Poet Laureate. In 1975, he was named Poet Laureate of Oregon; his tenure in the position lasted until 1990. In 1980, he retired from Lewis & Clark College but continued to travel extensively and give public readings of his poetry. In 1992, he won the Western States Book Award for lifetime achievement in poetry. Death Stafford died of a heart attack in Lake Oswego, Oregon on August 28, 1993, having written a poem that morning containing the lines, "'You don't have to / prove anything,' my mother said. 'Just be ready / for what God sends.'" In 2008, the Stafford family gave William Stafford's papers, including the 20,000 pages of his daily writing, to the Special Collections Department at Lewis & Clark College. Kim Stafford, who serves as literary executor for the Estate of William Stafford, has written a memoir Early Morning: Remembering My Father, William Stafford (Graywolf Press). References Wikipedia—http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Stafford_(poet)

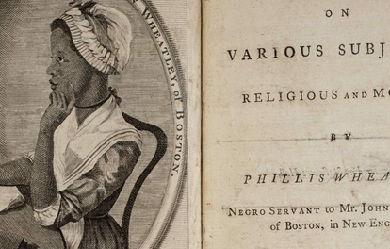

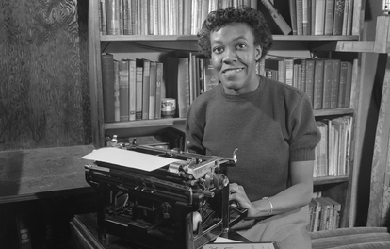

Phillis Wheatley was the first black poet in America to publish a book. She was born around 1753 in West Africa and brought to New England in 1761, where John Wheatley of Boston purchased her as a gift for his wife. Although they brought her into the household as a slave, the Wheatleys took a great interest in Phillis's education. Many biographers have pointed to her precocity; Wheatley learned to read and write English by the age of nine, and she became familiar with Latin, Greek, the Bible, and selected classics at an early age. She began writing poetry at thirteen, modeling her work on the English poets of the time, particularly John Milton, Thomas Gray, and Alexander Pope. Her poem "On the Death of the Rev. Mr. George Whitefield" was published as a broadside in cities such as Boston, New York, and Philadelphia and garnered Wheatley national acclaim. This poem was also printed in London. Over the next few years, she would print a number of broadsides elegizing prominent English and colonial leaders. Wheatley's doctor suggested that a sea voyage might improve her delicate health, so in 1771 she accompanied Nathaniel Wheatley on a trip to London. She was well received in London and wrote to a friend of the "unexpected and unmerited civility and complaisance with which I was treated by all." In 1773, thirty-nine of her poems were published in London as Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral. The book includes many elegies as well as poems on Christian themes; it also includes poems dealing with race, such as the often-anthologized "On Being Brought from Africa to America." She returned to America in 1773. After Mr. and Mrs. Wheatley died, Phillis was left to support herself as a seamstress and poet. It is unclear precisely when Wheatley was freed from slavery, although scholars suggest it occurred between 1774 and 1778. In 1776, Wheatley wrote a letter and poem in support of George Washington; he replied with an invitation to visit him in Cambridge, stating that he would be "happy to see a person so favored by the muses." In 1778, she married John Peters, who kept a grocery store. They had three children together, all of whom died young. Because of the war and the poor economy, Wheatley experienced difficulty publishing her poems. She solicited subscribers for a new volume that would include thirty-three new poems and thirteen letters, but was unable to raise the funds. Phillis Wheatley, who had once been internationally celebrated, died alone in a boarding house in 1784. She was thirty-one years old. Many of the poems for her proposed second volume disappeared and have never been recovered.

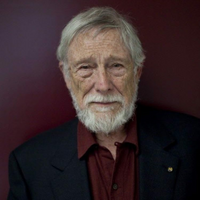

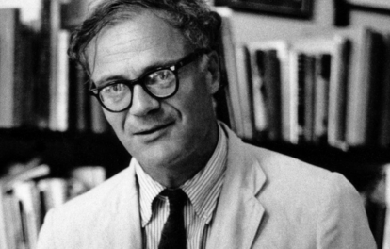

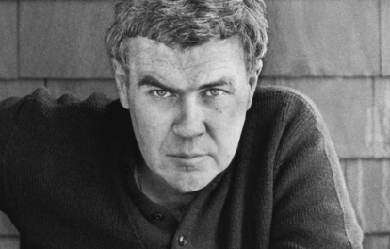

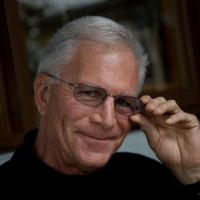

John Updike was a poet, essayist, short-story writer, critic, and novelist John Updike was born in Shillington, Pennsylvania, on March 18, 1932. His father taught high school math, and his mother wrote short stories and novels. Updike received his BA from Harvard University in 1954, the year he began to publish in The New Yorker. Thomas M. Disch wrote in Poetry magazine, "Updike enjoys such pre-eminence as a novelist that his poetry could be mistaken as a hobby or a foible," adding, "It is a poetry of civility—in its epigrammatical lucidity . . . and in its tone of vulgar bonhomie and good appetite." The Los Angeles Times noted that he "has earned an . . . imposing stance on the literary landscape . . . earning virtually every American literary award, repeated bestsellerdom and the near-royal status of the American author-celebrity." Updike is the author of more than fifty books. Among his volumes of poetry are Americana and Other Poems (Alfred A. Knopf, 2001), Collected Poems 1953-1993 (1993), Facing Nature (1985), Tossing and Turning (1977), Seventy Poems (1972), Midpoint and Other Poems (1969), and The Carpentered Hen and Other Tame Creatures (1958). His novels and short-story collections include Toward the End of Time (1997), The Afterlife and Other Stories (1994), Problems and Other Stories (1981), Marry Me (1976), Rabbit Redux (1971), and Couples (1968). Updike received numerous honors and awards including the National Book Award, American Book Award, National Book Critics Circle Award, and a National Arts Club Medal of Honor. He was awarded a Pulitzer Prize in 1982 for Rabbit is Rich and another Pulitzer Prize in 1990 for Rabbit at Rest. John Updike died due to complications of lung cancer on January 27, 2009. Poetry The Carpentered Hen and Other Tame Creatures (Harper and Brothers, 1958) Telephone Poles and Other Poems (Alfred A. Knopf, 1963) Midpoint and Other Poems (1969) Tossing and Turning (1977) Facing Nature (1985) Collected Poems 1953-1993 (1993) Americana: and Other Poems (2001) References Poets.org - www.poets.org/poet.php/prmPID/660

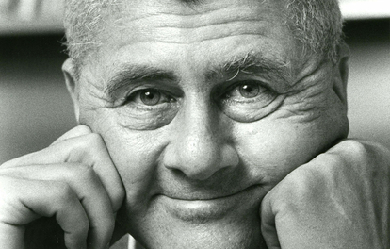

Gary Snyder (born May 8, 1930) is an American man of letters. Perhaps best known as a poet (often associated with the Beat Generation and the San Francisco Renaissance), he is also an essayist, lecturer, and environmental activist. He has been described as the "poet laureate of Deep Ecology". Snyder is a winner of a Pulitzer Prize for Poetry and the American Book Award. His work, in his various roles, reflects an immersion in both Buddhist spirituality and nature. Snyder has translated literature into English from ancient Chinese and modern Japanese. For many years, Snyder served as a faculty member at the University of California, Davis, and he also served for a time on the California Arts Council. Early life Gary Sherman Snyder was born in San Francisco, California to Harold and Lois Hennessy Snyder. Snyder is of German, Scots-Irish, and English ancestry. His family, impoverished by the Great Depression, moved to King County, Washington, when he was two years old. There they tended dairy cows, kept laying hens, had a small orchard, and made cedar-wood shingles, until moving to Portland, Oregon ten years later. At the age of seven, Snyder was laid up for four months by an accident. "So my folks brought me piles of books from the Seattle Public Library," he recalled in interview, "and it was then I really learned to read and from that time on was voracious — I figure that accident changed my life. At the end of four months, I had read more than most kids do by the time they're eighteen. And I didn't stop." Also during his ten childhood years in Washington, Snyder became aware of the presence of the Coast Salish people and developed an interest in the Native American peoples in general and their traditional relationship with nature. In 1942, following his parents' divorce, Snyder moved to Portland, Oregon with his mother and his younger sister, Anthea. Their mother, Lois Snyder Hennessy (born Wilkey), worked during this period as a reporter for The Oregonian. One of Gary's boyhood jobs was as a newspaper copy boy, also at the Oregonian. Also, during his teen years, he attended Lincoln High School, worked as a camp counselor, and went mountain climbing with the Mazamas youth group. Climbing remained an interest of his, especially during his twenties and thirties. In 1947, he started attending Reed College on a scholarship. Here he met, and for a time, roomed with the education author Carl Proujan and Philip Whalen and Lew Welch. At Reed, Snyder published his first poems in a student journal. He also spent the summer of 1948 working as a seaman. He joined the now defunct Marine Cooks and Stewards union to get this job, and would later work as a seaman in the mid-1950s to gain experience of other cultures in port cities. Snyder married Alison Gass in 1950; they separated after seven months, and divorced in 1952. While attending Reed, Snyder did folklore research on the Warm Springs Indian Reservation in central Oregon. He graduated with a dual degree in anthropology and literature in 1951. He spent the following few summers working as a timber scaler at Warm Springs, developing relationships with its people that were less rooted in academia. This experience formed the basis for some of his earliest published poems (including "A Berry Feast"), later collected in the book The Back Country. He also encountered the basic ideas of Buddhism and, through its arts, some of the Far East's traditional attitudes toward nature. He went to Indiana University with a graduate fellowship to study anthropology. (Snyder also began practicing self-taught Zen meditation.) He left after a single semester to return to San Francisco and to 'sink or swim as a poet'. Snyder worked for two summers in the North Cascades in Washington as a fire lookout, on Crater Mountain in 1952 and Sourdough Mountain in 1953 (both locations on the upper Skagit River). His attempts to get another lookout stint in 1954 (at the peak of McCarthyism), however, failed. He had been barred from working for the government, due to his association with the Marine Cooks and Stewards. Instead, he went back to Warm Springs to work in logging as a chokersetter (fastening cables to logs). This experience contributed to his Myths and Texts and the essay Ancient Forests of the Far West. The Beats Back in San Francisco, Snyder lived with Whalen, who shared his growing interest in Zen. Snyder's reading of the writings of D.T. Suzuki had in fact been a factor in his decision not to continue as a graduate-student in anthropology, and in 1953 he enrolled at the University of California, Berkeley to study Asian culture and languages. He studied ink and wash painting under Chiura Obata and Tang Dynasty poetry under Ch'en Shih-hsiang. Snyder continued to spend summers working in the forests, including one summer as a trail-builder in Yosemite. He spent some months in 1955 and 1956 living in a cabin (which he dubbed "Marin-an") outside Mill Valley, California with Jack Kerouac. It was also at this time that Snyder was an occasional student at the American Academy of Asian Studies, where Saburō Hasegawa and Alan Watts, among others, were teaching. Hasegawa introduced Snyder to the treatment of landscape painting as a meditative practice. This inspired Snyder to attempt something equivalent in poetry, and with Hasegawa's encouragement, he began work on Mountains and Rivers without End, which would be completed and published forty years later. During these years, Snyder was writing and collecting his own work, as well as embarking on the translation of the "Cold Mountain" poems by the 8th-century Chinese recluse Han Shan; this work appeared in chapbook-form in 1969, under the title Riprap & Cold Mountain Poems. Snyder met Allen Ginsberg when the latter sought Snyder out on the recommendation of Kenneth Rexroth. Then, through Ginsberg, Snyder and Kerouac came to know each other. This period provided the materials for Kerouac's novel The Dharma Bums, and Snyder was the inspiration for the novel's main character, Japhy Ryder, in the same way Neal Cassady had inspired Dean Moriarty in On the Road. As the large majority of people in the Beat movement had urban backgrounds, writers like Ginsberg and Kerouac found Snyder, with his backcountry and manual-labor experience and interest in things rural, a refreshing and almost exotic individual. Lawrence Ferlinghetti later referred to Snyder as 'the Thoreau of the Beat Generation'. Snyder read his poem "A Berry Feast" at the poetry reading at the Six Gallery in San Francisco (October 7, 1955) that heralded what was to become known as the San Francisco Renaissance. This also marked Snyder's first involvement with the Beats, although he was not a member of the original New York circle, but rather entered the scene through his association with Kenneth Rexroth. As recounted in Kerouac's Dharma Bums, even at age 25 Snyder felt he could have a role in the fateful future meeting of West and East. Snyder's first book, Riprap, which drew on his experiences as a forest lookout and on the trail-crew in Yosemite, was published in 1959. Japan and India Independently, some of the Beats, including Philip Whalen, had become interested in Zen, but Snyder was one of the more serious scholars of the subject among them, preparing in every way he could think of for eventual study in Japan. In 1955, the First Zen Institute of America offered him a scholarship for a year of Zen training in Japan, but the State Department refused to issue him a passport, informing him that "it has been alleged you are a Communist." A subsequent District of Columbia Court of Appeals ruling forced a change in policy, and Snyder got his passport. In the end, his expenses were paid by Ruth Fuller Sasaki, for whom he was supposed to work; but initially he served as personal attendant and English tutor to Zen abbot Miura Isshu, at Rinko-in, a temple in Shokoku-ji in Kyoto, where Dwight Goddard and R. H. Blyth had preceded him. Mornings, after zazen, sutra chanting, and chores for Miura, he took Japanese classes, bringing his spoken Japanese up to a level sufficient for kōan study. He developed a friendship with Philip Yampolsky, who took him around Kyoto. In early July 1955, he took refuge and requested to become Miura's disciple, thus formally becoming a Buddhist. He returned to California via the Persian Gulf, Turkey, Sri Lanka and various Pacific Islands, in 1958, voyaging as a crewman in the engine room on the oil freighter Sappa Creek, and took up residence at Marin-an again. He turned one room into a zendo, with about six regular participants. In early June, he met the poet Joanne Kyger. She became his girlfriend, and eventually his wife. In 1959, he shipped for Japan again, where he rented a cottage outside Kyoto. He became the first foreign disciple of Oda Sesso Roshi, the new abbot of Daitoku-ji. He married Kyger on February 28, 1960, immediately after her arrival, which Sasaki insisted they do, if they were to live together and be associated with the First Zen Institute of America. Snyder and Joanne Kyger were married from 1960 to 1965. During the period between 1956 and 1969, Snyder went back and forth between California and Japan, studying Zen, working on translations with Ruth Fuller Sasaki, and finally living for a while with a group of other people on the small, volcanic island of Suwanosejima. His previous study of written Chinese assisted his immersion in the Zen tradition (with its roots in Tang Dynasty China) and enabled him to take on certain professional projects while he was living in Japan. Snyder received the Zen precepts and a dharma name (Chofu, "Listen to the Wind"), and lived sometimes as a de facto monk, but never registered to become a priest and planned eventually to return to the United States to 'turn the wheel of the dharma'. During this time, he published a collection of his poems from the early to mid '50s, Myths & Texts (1960), and Six Sections from Mountains and Rivers Without End (1965). This last was the beginning of a project that he was to continue working on until the late 1990s. Much of Snyder's poetry expresses experiences, environments, and insights involved with the work he has done for a living: logger, fire-lookout, steam-freighter crew, translator, carpenter, and itinerant poet, among other things. During his years in Japan, Snyder was also initiated into Shugendo, a form of ancient Japanese animism, (see also Yamabushi). In the early 1960s he traveled for six months through India with his wife Joanne, Allen Ginsberg, and Peter Orlovsky. Snyder and Joanne Kyger separated soon after a trip to India, and divorced in 1965. Dharma Bums In the 1950s, Snyder took part in the rise of a strand of Buddhist anarchism emerging from the Beat movement. Snyder was the inspiration for the character Japhy Rider in Jack Kerouac's novel The Dharma Bums (1958). Snyder had spent considerable time in Japan studying Zen Buddhism, and in 1961 published an essay, Buddhist Anarchism, where he described the connection he saw between these two traditions, originating in different parts of the world: "The mercy of the West has been social revolution; the mercy of the East has been individual insight into the basic self/void." He advocated "using such means as civil disobedience, outspoken criticism, protest, pacifism, voluntary poverty and even gentle violence" and defended "the right of individuals to smoke ganja, eat peyote, be polygymous, polyandrous or homosexual" which he saw as being banned by "the Judaeo-Capitalist-Christian-Marxist West". Kitkitdizze In 1966, Snyder joined Allen Ginsberg, Zentatsu Richard Baker, Roshi of the San Francisco Zen Center, and Donald Walters, a.k.a. "Swami Kriyananda," to buy 100 acres (0.40 km2) in the Sierra foothills, north of Nevada City, California. In 1970, this would become his home, with the Snyder family's portion being named Kitkitdizze. Snyder spent the summers of 1967 and 1968 with a group of Japanese back-to-the-land drop-outs known as "the Tribe" on Suwanosejima (a small Japanese island in the East China Sea), where they combed the beaches, gathered edible plants, and fished. On the island, on August 6, 1967, he married Masa Uehara, whom he had met in Osaka a year earlier. In 1968, they moved to California with their infant son, Kai (born April 1968). Their second son, Gen, was born a year later. In 1971, they moved to the San Juan Ridge in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada of Northern California, near the South Yuba River, where they and friends built a house that drew on rural-Japanese and Native-American architectural ideas. In 1967 his book The Back Country appeared, again mainly a collection of poems stretching back over about fifteen years. Snyder devoted a section at the end of the book to his translations of eighteen poems by Kenji Miyazawa. Later life and writings Regarding Wave appeared in 1969, a stylistic departure offering poems that were more emotional, metaphoric, and lyrical. From the late 1960s, the content of Snyder's poetry increasingly had to do with family, friends, and community. He continued to publish poetry throughout the 1970s, much of it reflecting his re-immersion in life on the American continent and his involvement in the back-to-the-land movement in the Sierra foothills. His 1974 book Turtle Island, titled after a Native American name for the North American continent, won a Pulitzer Prize. It also influenced numerous West Coast Generation X writers, including Alex Steffen, Bruce Barcott and Mark Morford. His 1983 book Axe Handles, won an American Book Award. Snyder wrote numerous essays setting forth his views on poetry, culture, social experimentation, and the environment. Many of these were collected in Earth House Hold (1969), The Old Ways (1977), The Real Work (1980), The Practice of the Wild (1990), A Place in Space (1995), and The Gary Snyder Reader (1999). In 1979, Snyder published He Who Hunted Birds in His Father's Village: The Dimensions of a Haida Myth, based on his Reed thesis. Snyder's journals from his travel in India in the mid-1960s appeared in 1983 under the title Passage Through India. In these, his wide-ranging interests in cultures, natural history, religions, social critique, contemporary America, and hands-on aspects of rural life, as well as his ideas on literature, were given full-blown articulation. In 1986, Snyder became a professor in the writing-program at the University of California, Davis. Snyder is now professor emeritus of English. Snyder was married to Uehara for twenty-two years; the couple divorced in 1989. Snyder married Carole Lynn Koda (October 3, 1947 – June 29, 2006), who would write Homegrown: Thirteen brothers and sisters, a century in America, in 1991, and remained married to her until her death of cancer. She had been born in the third generation of a successful Japanese-American farming family, noted for its excellent rice. She shared Buddhism, extensive travels, and work with Snyder, and performed independent work as a naturalist. As Snyder's involvement in environmental issues and his teaching grew, he seemed to move away from poetry for much of the 1980s and early 1990s. However, in 1996 he published the complete Mountains and Rivers Without End, a mixture of the lyrical and epic modes celebrating the act of inhabitation on a specific place on the planet. This work was written over a 40-year period. It has been translated into Japanese and French. In 2004 Snyder published Danger on Peaks, his first collection of new poems in twenty years. Snyder was awarded the Levinson Prize from the journal Poetry, the American Poetry Society Shelley Memorial Award (1986), was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters (1987), and won the 1997 Bollingen Prize for Poetry and, that same year, the John Hay Award for Nature Writing. Snyder also has the distinction of being the first American to receive the Buddhism Transmission Award (for 1998) from the Japan-based Bukkyo Dendo Kyokai Foundation. For his ecological and social activism, Snyder was named as one of the 100 visionaries selected in 1995 by Utne Reader. Snyder's life and work was celebrated in John J. Healy's 2010 documentary The Practice of the Wild. The film, which debuted at the 53rd San Francisco International Film Festival, features wide-ranging, running conversations between Snyder and poet, writer and longtime colleague Jim Harrison, filmed mostly on the Hearst Ranch in San Simeon, California. The film also shows archival photographs and film of Snyder's life. Poetic work Gary Snyder uses mainly common speech-patterns as the basis for his lines, though his style has been noted for its "flexibility" and the variety of different forms his poems have taken. He does not typically use conventional meters nor intentional rhyme. "Love and respect for the primitive tribe, honour accorded the Earth, the escape from city and industry into both the past and the possible, contemplation, the communal", such, according to Glyn Maxwell, is the awareness and commitment behind the specific poems. The author and editor Stewart Brand once wrote: "Gary Snyder's poetry addresses the life-planet identification with unusual simplicity of style and complexity of effect." According to Jody Norton, this simplicity and complexity derives from Snyder's use of natural imagery (geographical formations, flora, and fauna)in his poems. Such imagery can be both sensual at a personal level yet universal and generic in nature. In the 1968 poem "Beneath My Hand and Eye the Distant Hills, Your Body," the author compares the intimate experience of a lover's caress with the mountains, hills, cinder cones, and craters of the Uintah Mountains. Readers become explorers on both a very private level as well as a very public and grand level. A simplistic touch becoming a very complex interaction occurring at multiple levels. This is the effect Snyder intended. In an interview with Faas, he states." There is a direction which is very beautiful, and that's the direction of the organism being less and less locked into itself, less and less locked into its own body structure and its relatively inadequate sense organs, towards a state where the organism can actually go out from itself and share itself with others." Snyder has always maintained that his personal sensibility arose from his interest in Native Americans and their involvement with nature and knowledge of it; indeed, their ways seemed to resonate with his own. And he has sought something akin to this through Buddhist practices, Yamabushi initiation, and other experiences and involvements. However, since his youth he has been quite literate, and he has written about his appreciation of writers of similar sensibilities, like D. H. Lawrence, William Butler Yeats, and some of the great ancient Chinese poets. William Carlos Williams was another influence, especially on Snyder's earliest published work. Starting in high school, Snyder read and loved the work of Robinson Jeffers, his predecessor in poetry of the landscape of the American West; but, whereas Jeffers valued nature over humankind, Snyder saw humankind as part of nature. Snyder commented in interview "I have some concerns that I'm continually investigating that tie together biology, mysticism, prehistory, general systems theory". Snyder argues that poets, and humans in general, need to adjust to very long timescales, especially when judging the consequences of their actions. His poetry examines the gap between nature and culture so as to point to ways in which the two can be more closely integrated. In 2004, receiving the Masaoka Shiki International Haiku Awards Grand Prize, Snyder highlighted traditional ballads and folk songs, Native American songs and poems, William Blake, Walt Whitman, Jeffers, Ezra Pound, Noh drama, Zen aphorisms, Federico García Lorca, and Robert Duncan as significant influences on his poetry, but added, "the influence from haiku and from the Chinese is, I think, the deepest." Romanticism Snyder is among those writers who have sought to dis-entrench conventional thinking about primitive peoples that has viewed them as simple-minded, ignorantly superstitious, brutish, and prone to violent emotionalism. In the 1960s Snyder developed a "neo-tribalist" view akin to the "post-modernist" theory of French Sociologist Michel Maffesoli. The "re-tribalization" of the modern, mass-society world envisioned by Marshall McLuhan, with all of the ominous, dystopian possibilities that McLuhan warned of, subsequently accepted by many modern intellectuals, is not the future that Snyder expects or works toward. Snyder's is a positive interpretation of the tribe and of the possible future. Todd Ensign describes Snyder's interpretation as blending ancient tribal beliefs and traditions, philosophy, physicality, and nature with politics to create his own form of Postmodern-environmentalism. Snyder rejects the perspective which portrays nature and humanity in direct opposition to one another. Instead, he chooses to write from multiple viewpoints. He purposely sets out to bring about change on the emotional, physical, and political levels by emphasizing the ecological problems faced by today's society. Beat Gary Snyder is widely regarded as a member of the Beat Generation circle of writers: he was one of the poets that read at the famous Six Gallery event, and was written about in one of Kerouac's most popular novels, The Dharma Bums. Some critics argue that Snyder's connection with the Beats is exaggerated and that he might better be regarded as a member of the West-Coast group the San Francisco Renaissance, which developed independently. Snyder himself has some reservations about the label "Beat", but does not appear to have any strong objection to being included in the group. He often talks about the Beats in the first person plural, referring to the group as "we" and "us". A quotation from a 1974 interview at the University of North Dakota Writers Conference (published in The Beat Vision): I never did know exactly what was meant by the term 'The Beats', but let's say that the original meeting, association, comradeship of Allen [Ginsberg], myself, Michael [McClure], Lawrence [Ferlinghetti], Philip Whalen, who's not here, Lew Welch, who's dead, Gregory [Corso], for me, to a somewhat lesser extent (I never knew Gregory as well as the others) did embody a criticism and a vision which we shared in various ways, and then went our own ways for many years. Where we began to come really close together again, in the late '60s, and gradually working toward this point, it seems to me, was when Allen began to take a deep interest in Oriental thought and then in Buddhism which added another dimension to our levels of agreement; and later through Allen's influence, Lawrence began to draw toward that; and from another angle, Michael and I after the lapse of some years of contact, found our heads very much in the same place, and it's very curious and interesting now; and Lawrence went off in a very political direction for a while, which none of us had any objection with, except that wasn't my main focus. It's very interesting that we find ourselves so much on the same ground again, after having explored divergent paths; and find ourselves united on this position of powerful environmental concern, critique of the future of the individual state, and an essentially shared poetics, and only half-stated but in the background very powerfully there, a basic agreement on some Buddhist type psychological views of human nature and human possibilities. Snyder has also commented "The term Beat is better used for a smaller group of writers ... the immediate group around Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac, plus Gregory Corso and a few others. Many of us ... belong together in the category of the San Francisco Renaissance. ... Still, beat can also be defined as a particular state of mind ... and I was in that mind for a while". Bibliography * Myths & Texts (1960) * Six Sections from Mountains and Rivers Without End (1965) * The Back Country (1967) * Riprap and Cold Mountain Poems (1969) * Regarding Wave (1969) * Earth House Hold (1969) * Turtle Island (1974) * The Old Ways (1977) * He Who Hunted Birds in His Father's Village: The Dimensions of a Haida Myth (1979) * The Real Work: Interviews & Talks 1964-1979 (1980) * Axe Handles (1983) * Passage Through India (1983) * Left Out in the Rain (1988) * The Practice of the Wild (1990) * No Nature: New and Selected Poems (1992) * A Place in Space (1995) * narrator of the audio book version of Kazuaki Tanahashi's Moon in a Dewdrop from Dōgen's Shōbōgenzō * Mountains and Rivers Without End (1996) * The Gary Snyder Reader: Prose, Poetry, and Translations (1999) * The High Sierra of California, with Tom Killion (2002) * Look Out: a Selection of Writings (November 2002) * Danger on Peaks (2005) * Back on the Fire: Essays (2007) * The Selected Letters of Allen Ginsberg and Gary Snyder, 1956-1991"(2009) * Tamalpais Walking, with Tom Killion (2009) * The Etiquette of Freedom, with Jim Harrison (2010) film by Will Hearst with book edited by Paul Ebenkamp * Nobody Home: Writing, Buddhism, and Living in Places, with Julia Martin, Trinity University Press (2014). * This Present Moment (April 2015) * Distant Neighbors: The Selected Letters of Wendell Berry and Gary Snyder (May 2015) * The Great Clod: Notes and Memories on the Natural History of China and Japan (March 2016) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gary_Snyder

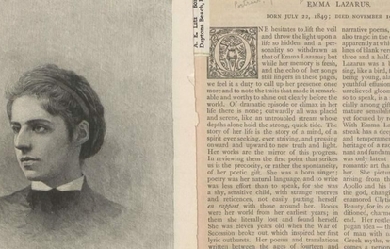

Emma Lazarus (July 22, 1849– November 19, 1887) was an American poet born in New York City. She is best known for “The New Colossus”, a sonnet written in 1883; its lines appear inscribed on a bronze plaque in the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty installed in 1903, a decade and a half after Lazarus’s death. Lazarus was born into a large Sephardic-Ashkenazi Jewish family, the fourth of seven children of Moses Lazarus and Esther Nathan, The Lazarus family was from Germany, and the Nathan family was originally from Portugal and resident in New York long before the American Revolution.

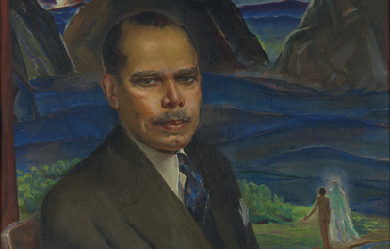

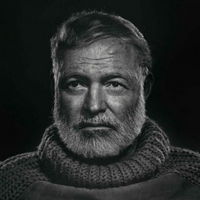

Born on July 21, 1899, in Garrettsville, Ohio, Harold Hart Crane was a highly anxious and volatile child. He began writing verse in his early teenage years, and though he never attended college, read regularly on his own, digesting the works of the Elizabethan dramatists and poets—Shakespeare, Marlowe, and Donne—and the nineteenth-century French poets—Vildrac, Laforgue, and Rimbaud. His father, a candy manufacturer, attempted to dissuade him from a career in poetry, but Crane was determined to follow his passion to write. Living in New York City, he associated with many important figures in literature of the time, including Allen Tate, Katherine Anne Porter, E. E. Cummings, and Jean Toomer, but his heavy drinking and chronic instability frustrated any attempts at lasting friendship. An admirer of T. S. Eliot, Crane combined the influences of European literature and traditional versification with a particularly American sensibility derived from Walt Whitman. His major work, the book-length poem, The Bridge, expresses in ecstatic terms a vision of the historical and spiritual significance of America. Like Eliot, Crane used the landscape of the modern, industrialized city to create a powerful new symbolic literature. Hart Crane committed suicide in 1932, at the age of thirty-three, by jumping from the deck of a steamship sailing back to New York from Mexico. A SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY Poetry The Complete Poems and Selected Letters and Prose (1966) The Bridge (1930) White Buildings (1926) Prose Letters (1952) References Poets.org – http://www.poets.org/poet.php/prmPID/233

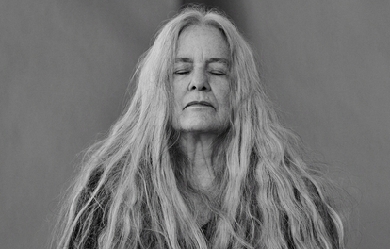

Sharon Olds, born November 19, 1942 in San Francisco, California, is an American poet recipient of many awards including the 2013 Pulitzer Prize in Poetry, the 1984 National Book Critics Circle Award, and the first San Francisco Poetry Center Award in 1980. She currently teaches creative writing at New York University.

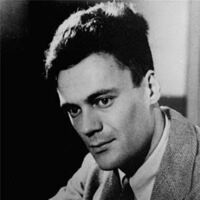

John Lawrence Ashbery (born July 28, 1927) is an American poet. He has published more than twenty volumes of poetry and won nearly every major American award for poetry, including a Pulitzer Prize in 1976 for his collection Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror. Renowned for its postmodern complexity and opacity, Ashbery's work still proves controversial. Ashbery has stated that he wishes his work to be accessible to as many people as possible, and not to be a private dialogue with himself. At the same time, he once joked that some critics still view him as "a harebrained, homegrown surrealist whose poetry defies even the rules and logic of Surrealism." Langdon Hammer, chairman of the English Department at Yale University, wrote in 2008, "No figure looms so large in American poetry over the past 50 years as John Ashbery" and "No American poet has had a larger, more diverse vocabulary, not Whitman, not Pound." Stephen Burt, a poet and Harvard professor of English, has compared Ashbery to T. S. Eliot, calling Ashbery "the last figure whom half the English-language poets alive thought a great model, and the other half thought incomprehensible". Life Ashbery was born in Rochester, New York, the son of Helen (née Lawrence), a biology teacher, and Chester Frederick Ashbery, a farmer. He was raised on a farm near Lake Ontario; his brother died when they were children. Ashbery was educated at Deerfield Academy, an all-boys school, where he read such poets as W. H. Auden and Dylan Thomas and began writing poetry. Two of his poems were published in Poetry magazine under the name of a classmate who had submitted them without Ashbery's knowledge or permission. Ashbery also published a handful of poems, including a sonnet about his frustrated love for a fellow student, and a piece of short fiction in the school newspaper, the Deerfield Scroll. His first ambition was to be a painter. From the age of 11 until he was 15 Ashbery took weekly classes at the art museum in Rochester. Ashbery at a 2007 tribute to W.H. Auden at Cooper Union in New York City. Ashbery graduated in 1949 with an A.B., cum laude, from Harvard College, where he was a member of the Harvard Advocate, the university's literary magazine, and the Signet Society. He wrote his senior thesis on the poetry of W. H. Auden. At Harvard he befriended fellow writers Kenneth Koch, Barbara Epstein, V. R. Lang, Frank O'Hara and Edward Gorey, and was a classmate of Robert Creeley, Robert Bly and Peter Davison. Ashbery went on to study briefly at New York University, and received an M.A. from Columbia in 1951. After working as a copywriter in New York from 1951 to 1955, from the mid-1950s, when he received a Fulbright Fellowship, through 1965, Ashbery lived in France. He was an editor of the 12 issues of Art and Literature (1964–67) and the New Poetry issue of Harry Mathews' Locus Solus (# 3/4; 1962). To make ends meet he translated French murder mysteries, served as the art editor for the European edition of the New York Herald Tribune and was an art critic for Art International (1960–65) and a Paris correspondent for Art News (1963–66), when Thomas Hess took over as editor. During this period he lived with the French poet Pierre Martory, whose books Every Question but One (1990), The Landscape is behind the Door (1994) and The Landscapist he has translated (2008), as he has Arthur Rimbaud (Illuminations), Max Jacob (The Dice Cup), Pierre Reverdy (Haunted House), and many titles by Raymond Roussel. After returning to the United States, he continued his career as an art critic for New York and Newsweek magazines while also serving on the editorial board of ARTNews until 1972. Several years later, he began a stint as an editor at Partisan Review, serving from 1976 to 1980. During the fall of 1963, Ashbery became acquainted with Andy Warhol at a scheduled poetry reading at the Literary Theatre in New York. He had previously written favorable reviews of Warhol's art. That same year he reviewed Warhol's Flowers exhibition at Galerie Illeana Sonnabend in Paris, describing Warhol's visit to Paris as "the biggest transatlantic fuss since Oscar Wilde brought culture to Buffalo in the nineties". Ashbery returned to New York near the end of 1965 and was welcomed with a large party at the Factory. He became close friends with poet Gerard Malanga, Warhol's assistant, on whom he had an important influence as a poet. In 1967 his poem Europe was used as the central text in Eric Salzman's Foxes and Hedgehogs as part of the New Image of Sound series at Hunter College, conducted by Dennis Russell Davies. When the poet sent Salzman Three Madrigals in 1968, the composer featured them in the seminal Nude Paper Sermon, released by Nonesuch Records in 1989. In the early 1970s, Ashbery began teaching at Brooklyn College, where his students included poet John Yau. He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1983. In the 1980s, he moved to Bard College, where he was the Charles P. Stevenson, Jr., Professor of Languages and Literature, until 2008, when he retired; since that time, he has continued to win awards, present readings, and work with graduate and undergraduates at many other institutions. He was the poet laureate of New York State from 2001 to 2003, and also served for many years as a chancellor of the Academy of American Poets. He serves on the contributing editorial board of the literary journal Conjunctions. He was a Millet Writing Fellow at Wesleyan University, in 2010, and participated in Wesleyan's Distinguished Writers Series. Ashbery lives in New York City and Hudson, New York, with his partner, David Kermani. Work Ashbery's long list of awards began with the Yale Younger Poets Prize in 1956. The selection, by W. H. Auden, of Ashbery's first collection, Some Trees, later caused some controversy. His early work shows the influence of Auden, along with Wallace Stevens, Boris Pasternak, and many of the French surrealists (his translations from French literature are numerous). In the late 1950s, John Bernard Myers, co-owner of the Tibor de Nagy Gallery, categorized the common traits of Ashbery's avant-garde poetry, as well as that of Kenneth Koch, Frank O'Hara, James Schuyler, Barbara Guest, Kenward Elmslie and others, as constituting a "New York School". Ashbery published some work in the avant-garde little magazine Nomad at the beginning of the 1960s. He then wrote two collections while in France, the highly controversial The Tennis Court Oath (1962) and Rivers and Mountains (1966), before returning to New York to write The Double Dream of Spring, published in 1970. Increasing critical recognition in the 1970s transformed Ashbery from an obscure avant-garde experimentalist into one of America's most important poets (though still one of its most controversial). After the publication of Three Poems (1973) came Self-portrait in a Convex Mirror, for which he was awarded the three major American poetry awards: the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Award and the National Book Critics Circle Award). The collection's title poem is considered to be one of the masterpieces of late-20th-century American poetic literature. His subsequent collection, the more difficult Houseboat Days (1977), reinforced Ashbery's reputation, as did 1979's As We Know, which contains the long, double-columned poem "Litany". By the 1980s and 1990s, Ashbery had become a central figure in American and more broadly English-language poetry, as his number of imitators attested. Ashbery's works are characterized by a free-flowing, often disjunctive syntax; extensive linguistic play, often infused with considerable humor; and a prosaic, sometimes disarmingly flat or parodic tone. The play of the human mind is the subject of a great many of his poems. Ashbery once said that his goal was "to produce a poem that the critic cannot even talk about". Formally, the earliest poems show the influence of conventional poetic practice, yet by The Tennis Court Oath a much more revolutionary engagement with form appears. Ashbery returned to something approaching a reconciliation between tradition and innovation with many of the poems in The Double Dream of Spring, though his Three Poems are written in long blocks of prose. Although he has never again approached the radical experimentation of The Tennis Court Oath poems or "The Skaters" and "Into the Dusk-Charged Air" from his collection Rivers and Mountains, syntactic and semantic experimentation, linguistic expressiveness, deft, often abrupt shifts of register, and insistent wit remain consistent elements of his work. Ashbery's art criticism has been collected in the 1989 volume Reported Sightings, Art Chronicles 1957-1987, edited by the poet David Bergman. He has written one novel, A Nest of Ninnies, with fellow poet James Schuyler, and in his 20s and 30s penned several plays, three of which have been collected in Three Plays (1978). Ashbery's Charles Eliot Norton Lectures at Harvard University were published as Other Traditions in 2000. A larger collection of his prose writings, Selected Prose, appeared in 2005. In 2008, his Collected Poems 1956–1987 was published as part of the Library of America series. Poetry Collections * Turandot and other poems (1953) * Some Trees (1956), winner of the Yale Younger Poets Prize * The Tennis Court Oath (1962) * Rivers and Mountains (1966) * The Double Dream of Spring (1970) * Three Poems (1972) * The Vermont Notebook (1975), illustrated prose poems * Self-portrait in a Convex Mirror (1975), awarded the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Award and the National Book Critics Circle Award Houseboat Days (1977) * As We Know (1979) * Shadow Train (1981) * A Wave (1984), awarded the Lenore Marshall Poetry Prize and the Bollingen Prize * April Galleons (1987) * Flow Chart (1991), book-length poem * Hotel Lautréamont (1992) * And the Stars Were Shining (1994) * Can You Hear, Bird? (1995) * Wakefulness (1998) * Girls on the Run (1999), a book-length poem inspired by the work of Henry Darger * Your Name Here (2000) * As Umbrellas Follow Rain (2001) * Chinese Whispers (2002) * Where Shall I Wander (2005) (finalist for the National Book Award) * Notes from the Air: Selected Later Poems (2007) (winner of the 2008 International Griffin Poetry Prize) * A Worldly Country (2007) * Planisphere (2009) * Collected Poems 1956-87 (Carcanet Press) (2010), ed. Mark Ford Quick Question (2012) * Breezeway (2015) * No i wiesz (1993) (translated into Polish by Bohdan Zadura, Andrzej Sosnowski and Piotr Sommer) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Ashbery

Charles Simic (born Dušan Simić; May 9, 1938) is a Serbian-American poet and was co-poetry editor of the Paris Review. He received the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1990 for The World Doesn’t End, and was a finalist of the Pulitzer Prize in 1986 for Selected Poems, 1963-1983 and in 1987 for Unending Blues. He was appointed the fifteenth Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress in 2007. Biography Early years Dušan Simić was born in Belgrade. In his early childhood, during World War II, he and his family were forced to evacuate their home several times to escape indiscriminate bombing of Belgrade. Growing up as a child in war-torn Europe shaped much of his world-view, Simic states. In an interview from the Cortland Review he said, “Being one of the millions of displaced persons made an impression on me. In addition to my own little story of bad luck, I heard plenty of others. I’m still amazed by all the vileness and stupidity I witnessed in my life.” Simic immigrated to the United States with his brother and mother in order to join his father in 1954 when he was sixteen. He grew up in Chicago. In 1961 he was drafted into the U.S. Army, and in 1966 he earned his B.A. from New York University while working at night to cover the costs of tuition. He is professor emeritus of American literature and creative writing at the University of New Hampshire, where he has taught since 1973 and lives on the shore of Bow Lake in Strafford, New Hampshire. Career He began to make a name for himself in the early to mid-1970s as a literary minimalist, writing terse, imagistic poems. Critics have referred to Simic’s poems as “tightly constructed Chinese puzzle boxes”. He himself stated: “Words make love on the page like flies in the summer heat and the poet is merely the bemused spectator.” Simic writes on such diverse topics as jazz, art, and philosophy. He is a translator, essayist and philosopher, opining on the current state of contemporary American poetry. He held the position of poetry editor of The Paris Review and was replaced by Dan Chiasson. He was elected to The American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1995, received the Academy Fellowship in 1998, and was elected a Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets in 2000. Simic was one of the judges for the 2007 Griffin Poetry Prize and continues to contribute poetry and prose to The New York Review of Books. Simic received the US$100,000 Wallace Stevens Award in 2007 from the Academy of American Poets. He was selected by James Billington, Librarian of Congress, to be the fifteenth Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress, succeeding Donald Hall. In choosing Simic as the poet laureate, Billington cited “the rather stunning and original quality of his poetry”. In 2011, he was the recipient of the Frost Medal, presented annually for “lifetime achievement in poetry.” Awards * PEN Translation Prize (1980) * Ingram Merrill Foundation Fellowship (1983) * MacArthur Fellowship (1984–1989) * Pulitzer Prize finalist (1986) * Pulitzer Prize finalist (1987) * Pulitzer Prize for Poetry (1990) * Wallace Stevens Award (2007) * Frost Medal (2011) * Vilcek Prize in Literature (2011) * The Zbigniew Herbert International Literary Award (2014) * Golden Wreath of the Struga Poetry Evenings (2017) Bibliography References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Simic

Katharine Lee Bates (August 12, 1859– March 28, 1929) was an American songwriter. She is remembered as the author of the words to the anthem “America the Beautiful”. She popularized “Mrs. Santa Claus” through her poem Goody Santa Claus on a Sleigh Ride (1889). Life and career Bates was born in Falmouth, Massachusetts, the daughter of Congregational pastor William Bates and his wife, Cornelia Frances Lee. She graduated from Wellesley High School in 1874 and from Wellesley College with a B.A. in 1880. She taught at Natick High School during 1880–81 and at Dana Hall School from 1885 until 1889. She returned to Wellesley as an instructor, then an associate professor 1891–93 when she was awarded an M.A. and became full professor of English literature. She studied at Oxford University during 1890–91. While teaching at Wellesley, she was elected a member of the newly formed Pi Gamma Mu honor society for the social sciences because of her interest in history and politics. Bates was a prolific author of many volumes of poetry, travel books, and children’s books. She popularized Mrs. Claus in her poem Goody Santa Claus on a Sleigh Ride from the collection Sunshine and other Verses for Children (1889). She contributed regularly to periodicals, sometimes under the pseudonym James Lincoln, including Atlantic Monthly, The Congregationalist, Boston Evening Transcript, Christian Century, Contemporary Verse, Lippincott’s and Delineator. A lifelong, active Republican, Bates broke with the party to endorse Democratic presidential candidate John W. Davis in 1924 because of Republican opposition to American participation in the League of Nations. She said: “Though born and bred in the Republican camp, I cannot bear their betrayal of Mr. Wilson and their rejection of the League of Nations, our one hope of peace on earth.” Bates never married. In 1910, when a colleague described “free-flying spinsters” as “fringe on the garment of life”, Bates answered: “I always thought the fringe had the best of it. I don’t think I mind not being woven in.” Bates died in Wellesley, Massachusetts, on September 28, 1929, and is buried in Oak Grove Cemetery at Falmouth. The historic home and birthplace of Bates in Falmouth, was sold to Ruth P. Clark in November 2013 for $1,200,000. Relationship with Katharine Coman Bates lived in Wellesley with Katharine Coman, who was a history and political economy teacher and founder of the Wellesley College School Economics department. The pair lived together for twenty-five years until Coman’s death in 1915. In 1922, Bates published Yellow Clover: A Book of Remembrance, a collection of poems written “to or about my Friend” Katharine Coman, some of which had been published in Coman’s lifetime. Some describe the couple as intimate lesbian partners, citing as an example Bates’ 1891 letter to Coman: "It was never very possible to leave Wellesley [for good], because so many love-anchors held me there, and it seemed least of all possible when I had just found the long-desired way to your dearest heart... Of course I want to come to you, very much as I want to come to Heaven." Others contest the use of the term lesbian to describe such a “Boston marriage”. Writes one: “We cannot say with certainty what sexual connotations these relationships conveyed. We do know that these relationships were deeply intellectual; they fostered verbal and physical expressions of love.” America the Beautiful The first draft of “America the Beautiful” was hastily jotted down in a notebook during the summer of 1893, which Bates spent teaching English at Colorado College in Colorado Springs, Colorado. Later she remembered: One day some of the other teachers and I decided to go on a trip to 14,000-foot Pikes Peak. We hired a prairie wagon. Near the top we had to leave the wagon and go the rest of the way on mules. I was very tired. But when I saw the view, I felt great joy. All the wonder of America seemed displayed there, with the sea-like expanse. The words to her only famous poem first appeared in print in The Congregationalist, a weekly journal, for Independence Day, 1895. The poem reached a wider audience when her revised version was printed in the Boston Evening Transcript on November 19, 1904. Her final expanded version was written in 1913. When a version appeared in her collection America the Beautiful, and Other Poems (1912), a reviewer in the New York Times wrote: “we intend no derogation to Miss Katharine Lee Bates when we say that she is a good minor poet.” The hymn has been sung to several tunes, but the familiar one is by Samuel A. Ward (1847–1903), written for his hymn “Materna” (1882). Honors The Bates family home on Falmouth’s Main Street is preserved by the Falmouth Historical Society. There is also a street named in her honor, “Katharine Lee Bates Road” in Falmouth. A plaque marks the site of the home where she lived as an adult on Centre Street in Newton, Massachusetts. The Katharine Lee Bates Elementary School on Elmwood Road in Wellesley, Massachusetts, and the Katharine Lee Bates Elementary School, founded in 1957 in Colorado Springs, Colorado, and Bates Hall dormitory at Wellesley College are named for her. The Katharine Lee Bates Professorship was established at Wellesley shortly after her death. Bates was inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1970. Collections of Bates’s manuscripts are housed at the Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, Radcliffe College; Falmouth Historical Society; Houghton Library, Harvard University; Wellesley College Archives. In 2012, she was listed as one of the 31 LGBT history “icons” by the organisers of LGBT History Month.

Anne Bradstreet was born in Northampton, England, in the year 1612, daughter of Thomas Dudley and Dorothy Yorke; Dudley, who had been a leader of volunteer soldiers in the English Reformation and Elizabethan Settlement, was then a steward to the Earl of Lincoln; Dorothy was a gentlewoman of noble heritage and she was also well educated. At the age of 16, Anne was married to Simon Bradstreet, a 25 year old assistant in the Massachusetts Bay Company and the son of a Puritan minister, who had been in the care of the Dudleys since the death of his father. Anne and her family emigrated to America in 1630 on the Arabella, one of the first ships to bring Puritans to New England in hopes of setting up plantation colonies. The journey was difficult; many perished during the three month journey, unable to cope with the harsh climate and poor living conditions, as sea squalls rocked the vessel, and scurvy brought on by malnutrition claimed their lives. Anne, who was a well educated girl, tutored in history, several languages and literature, was ill prepared for such rigorous travel, and would find the journey very difficult. Their trials and tribulations did not end upon their arrival, though, and many of those who had survived the journey, either died shortly thereafter, or elected to return to England, deciding they had suffered through enough. Thomas Dudley and his friend John Winthrop made up the Boston settlement's government; Winthrop was Governor, Dudley Deputy-Governor and Bradstreet Chief-Administrator. The colonists' fight for survival had become daily routine, and the climate, lack of food, and primitive living arrangements made it very difficult for Anne to adapt. She turned inwards and let her faith and imagination guide her through the most difficult moments; images of better days back in England, and the belief that God had not abandoned them helped her survive the hardships of the colony. Having previously been afflicted with smallpox, Anne would once again fall prey to illness as paralysis took over her joints; surprisingly, she did not let her predicament dim her passion for living, and she and her husband managed to make a home for themselves, and raise a family. Despite her poor health, she had eight children, and loved them dearly. Simon eventually came to prosper in the new land, and for a while it seemed things would not be so bad. Tragedy struck once more, when one night the Bradstreet home was engulfed in flames; a devastating fire which left the family homeless and devoid of personal belongings. It did not take too long for them to get back on their feet, thanks to their hard work, and to Simon's social standing in the community. While Anne and her husband were very much in love, Simon's political duties kept him traveling to various colonies on diplomatic errands, so Anne would spend her lonely days and nights reading from her father's vast collection of books, and educating her children. The reading would not only keep her from being lonely, but she also learned a great deal about religion, science, history, the arts, and medicine; most of all, reading helped her cope with life in New England. Anne Bradstreet was especially fond of poetry, which she had begun to write herself; her works were kept private though, as it was frowned upon for women to pursue intellectual enlightenment, let alone create and air their views and opinions. She wrote for herself, her family, and close circle of educated friends, and did not intend on publication. One of her closest friends, Anne Hutchinson, who was also a religious and educated woman had made the mistake of airing her views publicly, and was banished from her community. However, Anne's work would not remained unnoticed... Her brother-in-law, John Woodbridge, had secretly copied Anne's work, and would later bring it to England to have it published, albeit without her permission. Woodbridge even admitted to it in the preface of her first collection, "The Tenth Muse Lately Sprung Up in America, By a Gentlewoman of Those Parts", which was published in 1650. The book did fairly well in England, and was to be the last of her poetry to be published during her lifetime. All her other poems were published posthumously. Anne Bradstreet's poetry was mostly based on her life experience, and her love for her husband and family. One of the most interesting aspects of her work is the context in which she wrote; an atmosphere where the search for knowledge was frowned upon as being against God's will, and where women were relegated to traditional roles. Yet, we cAnneot help but feel the love she had for both God, and her husband, and her intense devotion to both, and to her family, despite the fact that she clearly valued knowledge and intellect, and was a free thinker, who could even be considered an early feminist. By Anne Bradstreet's health was slowly failing; she had been through many ailments, and was now afflicted with tuberculosis. Shortly after contracting the disease, she lost her daughter Dorothy to illness as well, but her will was strong, and perhaps, as a reflection of her own acceptance of death, she found solace in thinking of her daughter in a better place. Soon thereafter, Anne Bradstreet's long and difficult battle with illness would be at an end, and she passed away on September 16, 1672, in Andover, Massachusetts, at the age 60.

Helen Maria Hunt Jackson, born Helen Fiske (October 15, 1830 – August 12, 1885), was a United States writer who became an activist on behalf of improved treatment of Native Americans by the U.S. government. She detailed the adverse effects of government actions in her history A Century of Dishonor (1881). Her novel Ramona dramatized the federal government's mistreatment of Native Americans in Southern California and attracted considerable attention to her cause, although its popularity was based on its romantic and picturesque qualities rather than its political content. It was estimated to have been reprinted 300 times, and contributed to the growth of tourism in Southern California. Early years She was born Helen Fiske in Amherst, Massachusetts, the daughter of Nathan Welby Fiske and Deborah Waterman Vinal. She had two brothers, both of whom died after birth, and a sister Anne. Her father was a minister, author, and professor of Latin, Greek, and philosophy at Amherst College. Her mother died in 1844 when Helen was fourteen, and her father three years later. Her father provided for her education and arranged for an aunt to care for her. Fiske attended Ipswich Female Seminary and the Abbott Institute, a boarding school run by Reverend J.S.C. Abbott in New York City. She was a classmate of the poet Emily Dickinson, also from Amherst. The two corresponded for the rest of their lives, but few of their letters have survived. Marriage and family In 1852 at age 22, Fiske married U.S. Army Captain Edward Bissell Hunt. They had two sons, one of whom, Murray Hunt, died as an infant in 1854 of a brain disease. In 1863, her husband died in a military accident. Her second son, Rennie Hunt, died of diphtheria in 1865. About 1873-1874, Hunt met William Sharpless Jackson, a wealthy banker and railroad executive, while visiting at Colorado Springs, Colorado, at the resort of Seven Falls. They married in 1875 and she took the name Jackson, under which she was best known for her writings. She was a Unitarian. Career Helen Hunt began writing after the deaths of her family members. She published her early work anonymously, usually under the name "H.H." Ralph Waldo Emerson admired her poetry and used several of her poems in his public readings. He included five of them in his anthology Parnassus. She traveled widely. In the winter of 1873-1874 she was in Colorado Springs, Colorado, in search of a cure for tuberculosis. Here she met the man who would become her second husband. Over the next two years, she published three novels in the anonymous No Name Series, including Mercy Philbrick's Choice and Hetty's Strange History. In 1879 her interests turned to Native Americans after hearing a lecture in Boston by the Ponca Chief Standing Bear. He described the forcible removal of the Ponca from their Nebraska reservation and transfer to the Quapaw Reservation in Indian Territory, where they suffered from disease, climate and poor supplies. Upset about the mistreatment of Native Americans by government agents, Jackson became an activist. She started investigating and publicizing government misconduct, circulating petitions, raising money, and writing letters to the New York Times on behalf of the Ponca. A fiery and prolific writer, Jackson engaged in heated exchanges with federal officials over the injustices committed against American Indians. Among her special targets was U.S. Secretary of Interior Carl Schurz, whom she once called "the most adroit liar I ever knew." She exposed the government's violation of treaties with the American Indian tribes. She documented the corruption of US Indian agents, military officers, and settlers who encroached on and stole Indian lands. Jackson won the support of several newspaper editors who published her reports. Among her correspondents were editor William Hayes Ward of the New York Independent, Richard Watson Guilder of the Century Magazine, and publisher Whitelaw Reid of the New York Daily Tribune. Jackson also wrote a book, the first published under her own name, condemning state and federal Indian policy, and detailing the history of broken treaties. A Century of Dishonor (1881) called for significant reform in government policy toward Native Americans.[10] Jackson sent a copy to every member of Congress with a quote from Benjamin Franklin printed in red on the cover: "Look upon your hands: they are stained with the blood of your relations." The New York Times later wrote that she "soon made enemies at Washington by her often unmeasured attacks, and while on general lines she did some good, her case was weakened by her inability, in some cases, to substantiate the charges she had made; hence many who were at first sympathetic fell away." Jackson went to southern California for respite. Having been interested in the area's missions and the Mission Indians on an earlier visit, she began an in-depth study. While in Los Angeles, she met Don Antonio Coronel, former mayor of the city and a well-known authority on early Californio life in the area. He had served as inspector of missions for the Mexican government. Coronel told her about the plight of the Mission Indians after 1833. They were buffeted by the secularization policies of the Mexican government, as well as later U.S. policies, both of which led to their removal from mission lands. Under its original land grants, the Mexican government provided for resident Indians to continue to occupy such lands. After taking control of the territory in 1848, the U.S. generally disregarded such Mission Indian occupancy claims. In 1852, there were an estimated 15,000 Mission Indians in Southern California. By the time of Jackson's visit, they numbered fewer than 4,000. Coronel's account inspired Jackson to action. The U.S. Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Hiram Price, recommended her appointment as an Interior Department agent. Jackson's assignment was to visit the Mission Indians, ascertain the location and condition of various bands, and determine what lands, if any, should be purchased for their use. With the help of the US Indian agent Abbot Kinney, Jackson traveled throughout Southern California and documented conditions. At one point, she hired a law firm to protect the rights of a family of Saboba Indians facing dispossession from their land at the foot of the San Jacinto Mountains. In 1883, Jackson completed her 56-page report. It recommended extensive government relief for the Mission Indians, including the purchase of new lands for reservations and the establishment of more Indian schools. A bill embodying her recommendations passed the U.S. Senate but died in the House of Representatives. Jackson decided to write a novel to reach a wider audience. When she wrote Coronel asking for details about early California and any romantic incidents he could remember, she explained her purpose: "I am going to write a novel, in which will be set forth some Indian experiences in a way to move people's hearts. People will read a novel when they will not read serious books."[14] She was inspired by her friend Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852). "If I could write a story that would do for the Indian one-hundredth part what Uncle Tom's Cabin did for the Negro, I would be thankful the rest of my life," she wrote. Although Jackson started an outline in California, she began writing the novel in December 1883 in her New York hotel room, and completed it in about three months. Originally titled In The Name of the Law, she published it as Ramona (1884). It featured Ramona, an orphan girl who was half Indian and half Scots, raised in Spanish Californio society, and her Indian husband Alessandro, and their struggles for land of their own. The characters were based on people known by Jackson and incidents which she had encountered. The book achieved rapid success among a wide public and was popular for generations; it was estimated to have been reprinted 300 times. Its romantic story also contributed to the growth of tourism to Southern California. Encouraged by the popularity of her book, Jackson planned to write a children's story about Indian issues, but did not live to complete it. Her last letter was written to President Grover Cleveland and said: "From my death bed I send you message of heartfelt thanks for what you have already done for the Indians. I ask you to read my Century of Dishonor. I am dying happier for the belief I have that it is your hand that is destined to strike the first steady blow toward lifting this burden of infamy from our country and righting the wrongs of the Indian race." Jackson died of stomach cancer in 1885 in San Francisco, California. Her husband arranged for her burial on a one-acre plot on a high plateau overlooking Colorado Springs, Colorado. Her grave was later moved to Evergreen Cemetery in Colorado Springs. At the time of her death, her estate was valued at $12,642. She used her married names, Helen Hunt and Helen Jackson, but she is most often referred to as Helen Hunt Jackson. The New York Times referred to her as Helen Hunt Jackson in 1885, reporting on her final illness, and in 1886, reporting on visitors to her grave. The name was used during her lifetime by others, though she disliked the practice. "It is not proper to keep one's first married name, after a second marriage", she wrote to Moncure Conway. To Caroline Healey Dall, she admitted she was "positively waging war" against being called "Helen Hunt Jackson". Critical response and legacy Jackson's A Century of Dishonor remains in print, as does a collection of her poetry. A New York Times reviewer said of Ramona that "by one estimate, the book has been reprinted 300 times." One year after Jackson's death the North American Review called Ramona "unquestionably the best novel yet produced by an American woman" and named it, along with Uncle Tom's Cabin, one of two most ethical novels of the 19th century. Sixty years after its publication, 600,000 copies had been sold. There have been over 300 reissues to date and the book has never been out of print. The novel has been adapted for other media, including three films, stage, and television productions. Valery Sherer Mathes assessed the writer and her work: Ramona may not have been another Uncle Tom's Cabin, but it served, along with Jackson's writings on the Mission Indians of California, as a catalyst for other reformers ....Helen Hunt Jackson cared deeply for the Indians of California. She cared enough to undermine her health while devoting the last few years of her life to bettering their lives. Her enduring writings, therefore, provided a legacy to other reformers, who cherished her work enough to carry on her struggle and at least try to improve the lives of America's first inhabitants. Her friend Emily Dickinson once described her limitations: "she has the facts but not the phosphorescence." In a review of a film version, a journalist wrote about the novel, calling it "the long and lugubrious romance by Helen Hunt Jackson, over which America wept unnumbered gallons in the eighties and nineties," and complained of "the long, uneventful stretches of the novel."[26] In reviewing the history of her publisher, Houghton Mifflin, a 1970 reviewer noted that Jackson typified the house's success: "Middle aged, middle class, middlebrow." Jackson herself wrote, "My Century of Dishonor and Ramona are the only things I have done of which I am glad.... They will live, and... bear fruit." A portion of Jackson's Colorado home has been reconstructed in the Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum and furnished with her possessions.