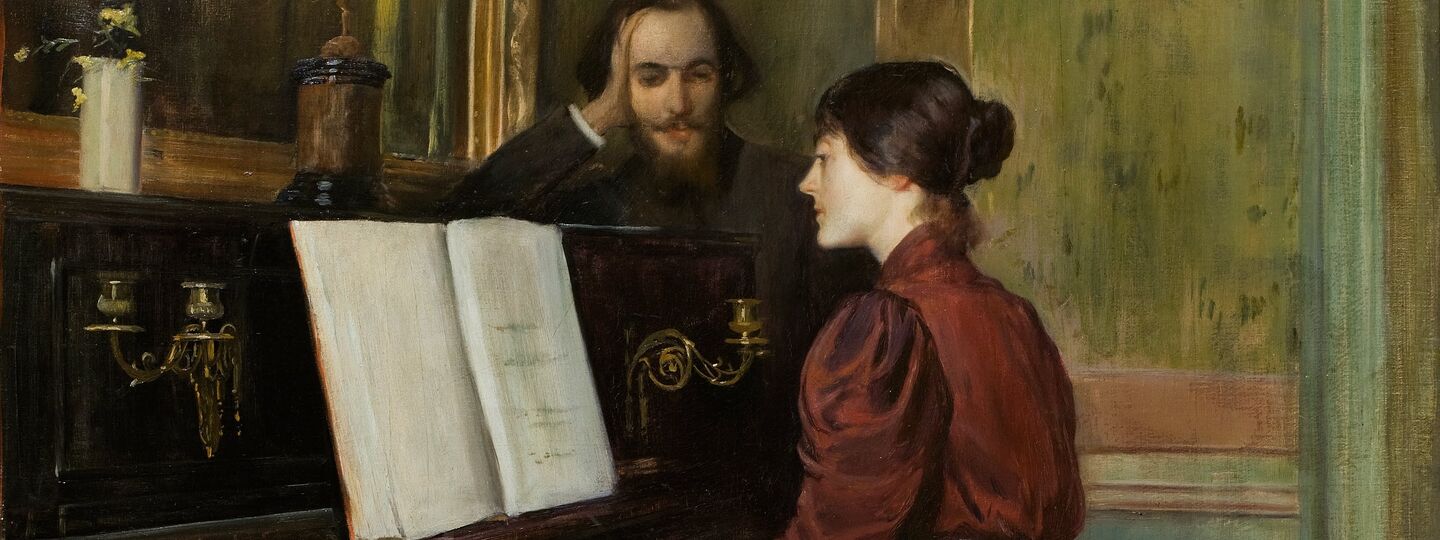

Info

Une romance

Santiago Rusiñol

1894

Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya - MNAC, Barcelona

Anne Finch (née Kingsmill), Countess of Winchilsea (April 1661– 5 August 1720), was an English poet, the third child of Sir William Kingsmill of Sydmonton Court and his wife, Anne Haslewood. She was well-educated as her family believed in good education for girls as well as for boys. In 1682, Anne Kingsmill went to St James’s Palace to become a maid of honour to Mary of Modena (wife of James, Duke of York, who later became King James II). There she met the courtier Heneage Finch whom she married on 15 May 1684. It was a happy marriage and Anne wrote several love poems to her husband, most famous perhaps A Letter to Dafnis, though her most well-known works speak on her bouts of depression and her fervent belief in social justice for women. Finch’s works often express a desire for respect as a female poet, lamenting her difficult position as a woman in the literary establishment and the court, while writing of an intense artistic impulse to write despite the difficulties. On 4 August 1712, Charles Finch, 4th Earl of Winchilsea, died childless. This made Anne’s husband, his uncle, the 5th Earl of Winchilsea, and Anne, the Countess of Winchilsea. She died in Westminster in 1720 and was buried at her home at Eastwell, Kent. Works * Did I, my lines intend for public view, How many censures, would their faults pursue, Some would, because such words they do affect, Cry they’re insipid, empty, and uncorrect. And many have attained, dull and untaught, The name of wit only by finding fault. True judges might condemn their want of wit, * And all might say, they’re by a woman writ…" (Finch, The Introduction) * With these lines, written in the poem The Introduction by Anne Finch, Countess of Winchilsea, readers are welcomed into a vibrant, emotional, and opinionated style. They are unapologetically let in on the distinctly female voice that is to come. Melancholy, full of wit, and socially conscious, Anne Finch wrote verse and dramatic literature with a talent that has caused her works to not only survive, but to flourish in an impressive poetic legacy throughout the centuries since her death. * Finch’s range as a writer was vast. She experimented with the poetic traditions of her day, often straying from the fold through her use of rhyme, meter and content, which ranged from the simplistic to the metaphysical. Additionally, Finch wrote several satiric vignettes modelled after the short tales of French fabulist Jean de La Fontaine. She mocked La Fontaine’s fables, offering social criticism through biting sarcasm. Finch’s more melancholy fare, however, gained her wider acclaim. Her famous poems in this sullen vein include A Nocturnal Reverie and Ardelia to Melancholy, both depicting severe depression. Her poetry is often considered to fall in the category of Augustan, reflecting upon nature and finding both an emotional and religious relationship to it in her verse. Finch also skilfully employed the Pindaric ode, exploring complex and irregular structures and rhyme schemes. Her most famous example of this technique is in The Spleen (1709), a poetic expression of depression and its effects: * What art thou, Spleen, which ev’ry thing dost ape? * Thou Proteus to abused mankind, Who never yet thy real cause could find, Or fix thee to remain in one continued shape. Still varying thy perplexing form, Now a Dead Sea thou’lt represent, A calm of stupid discontent, Then, dashing on the rocks wilt rage into a storm. Trembling sometimes thou dost appear, * Dissolved into a panic fear… (Finch, The Spleen) * This poem was first published anonymously, though it went on to become one of her most renowned pieces. As Virginia Woolf, a later proponent of intellectual investigation into Finch’s life and work, once famously wrote, “I would venture to guess that Anon, who wrote so many poems without signing them, was often a woman” (Woolf, A Room of One’s Own). * Anne Finch is known today as one of the most versatile and gifted poets (one of her poems was set to music by Purcell) of her generation. Biography * (The following essay is taken from the Biography Reference Center.) * As a poet, Finch attained a modest amount of notoriety during her lifetime, which spanned the late 17th and early 18th centuries. However, her large body of work, written during the Augustan period (approximately 1660–1760), would earn greater attention after her death. While Finch also authored fables and plays, today she is best known for her poetry: lyric poetry, odes, love poetry and prose poetry. Later literary critics recognised the diversity of her poetic output as well as its personal and intimate style. * In her works Finch drew upon her own observations and experiences, demonstrating an insightful awareness of the social mores and political climate of her era. But she also artfully recorded her private thoughts, which could be joyful or despairing, playful or despondent. The poems also revealed her highly developed spiritual side. * Finch was born Anne Kingsmill in April 1661 in Sydmonton, Hampshire, located in the southern part of England. Her parents were Sir William Kingsmill and Anne Haslewood. She was the youngest of three children. Her siblings included William and Bridget Kingsmill. * The young Anne never knew her father, as he died only five months after she was born. In his will, he specified that his daughters receive financial support equal to that of their brother for their education. Her mother remarried in 1662, to Sir Thomas Ogle, and later bore Anne Kingsmill’s half-sister, Dorothy Ogle. Anne would remain close to Dorothy for most of their lives. * Finch’s mother died in 1664. Shortly before her death she wrote a will giving control of her estate to her second husband. The will was successfully challenged in a Court of Chancery by Anne Kingsmill’s uncle, William Haslewood. Subsequently, Anne and Bridget Kingsmill lived with their grandmother, Lady Kingsmill, in Charing Cross, London, while their brother lived with his uncle William Haslewood. * In 1670 Lady Kingsmill filed her own Court of Chancery suit, demanding from William Haslewood a share in the educational and support monies for Anne and Bridget. The court split custody and financial support between Haslewood and Lady Kingsmill. When Lady Kingsmill died in 1672, Anne and Bridget rejoined their brother to be raised by Haslewood. The sisters received a comprehensive and progressive education, something that was uncommon for females at the time, and Anne Kingsmill learned about Greek and Roman mythology, the Bible, French and Italian languages, history, poetry, and drama. At the court of Charles II * The sisters remained in the Haslewood household until their uncle’s death in 1682. 21 years old at the time, Anne Kingsmill then went to live at St James’s Palace, joining the court of Charles II. She became one of six maids of honour to Mary of Modena, who was the wife of James, Duke of York, who would later become King James II. * Apparently Anne’s interest in poetry began at the palace, and she started writing her own verse. Her friends included Sarah Churchill and Anne Killigrew, two other maids of honour who also shared poetic interests. However, when Anne Kingsmill witnessed the derision within the court that greeted Killigrew’s poetic efforts (poetry was not a pursuit considered suitable for women), she decided to keep her own writing attempts to herself and her close friends. She remained secretive about her poetry until much later in her life, when she was encouraged to publish under her own name. * While residing at court, Anne Kingsmill also met Colonel Heneage Finch, the man who would become her husband. A courtier as well as a soldier, Colonel Finch had been appointed Groom of the Bedchamber to James, Duke of York, in 1683. His family had strong Royalist connections, as well as a pronounced loyalty to the Stuart dynasty, and his grandmother had become Countess of Winchilsea in 1628. Finch met Kingsmill and fell in love with her, but she at first resisted his romantic overtures. However, Finch proved a persistent suitor and the couple was finally married on 15 May 1684. * Upon her marriage, Anne Finch resigned her court position, but her husband retained his own appointment and would serve in various government positions. As such, the couple remained involved in court life. During the 1685 coronation of James II, Heneage Finch carried the canopy of the Queen, Mary of Modena, who had specifically requested his service. * The couple’s marriage proved to be enduring and happy, in part due to the aspects of equality in their partnership. Indeed, part of the development of her poetic skills was brought about by expressing her joy in her love for her husband and the positive effects of his lack of patriarchal impingement on her artistic development. These early works, many written to her husband (such as "A Letter to Dafnis: April 2d 1685"), celebrated their relationship and ardent intimacy. In expressing herself in such a fashion, Anne Finch quietly defied contemporary social conventions. In other early works she aimed a satiric disapproval at prevailing misogynistic attitudes. Still, her husband strongly supported her writing activities. * Despite their court connections, Anne and Heneage Finch led a rather sedate life. At first they lived in Westminster; then, as Heneage Finch became more involved in public affairs, they moved to London. His involvement had increased when James II took the throne in 1685. The couple demonstrated great loyalty to the king in what turned out to be a brief reign. Refusal to take Oath of Allegiance to King William * James II was deposed in 1688 during the “Bloodless Revolution”. During his short reign, James fell under intense criticism for his autocratic manner of rule. Eventually he fled England for exile in Saint-Germain, France. As a result, the British Parliament offered William of Orange the English crown. When the new monarchs, William and Mary, assumed the throne, oaths of allegiance became a requirement for both the public and the clergy. William and Mary were Protestants, and the Finches remained loyal to the Catholic Stuart court, refusing to take the oath. They also viewed their oaths to the previous monarchy as morally binding and constant. But such a stance invited trouble. Heneage Finch lost his government position and retreated from public life. As the loss of his position entailed a loss of income, the Finches were forced to live with friends in London for a period. However, while living in the city the couple faced harassment, fines and potential imprisonment. * In April 1690 Heneage Finch was arrested and charged with Jacobitism for attempting to join the exiled James II in France. It was a difficult time for Jacobites and Nonjurors (those who had refused to take the oath of allegiance, such as the Finches), as their arrests and punishments were abusive. Because of his arrest, Heneage and Anne Finch remained separated from April until November of that year. Understandably, the circumstances caused the couple a great deal of emotional turmoil. Living with friends in Kent while her husband prepared his defence in London, Anne Finch often succumbed to bouts of depression, something that afflicted her for most of her adult life. The poems that she wrote during this period, such as “Ardelia to Melancholy”, reflected her mental state. Other poems involved political themes. But all of her work was noticeably less playful and joyous than her earlier output. Move to country estate * After Heneage Finch was released and his case dismissed, his nephew Charles Finch, the fourth Earl of Winchelsea, invited the couple to permanently move into the family’s Eastwell Park, Kent, estate. The Finches took up residence in late 1690 and found peace and security on the beautiful estate, where they would live for more than 25 years in the quiet countryside. * For Anne Finch, the estate provided a fertile and supportive environment for her literary efforts. Charles Finch was a patron of the arts and, along with Heneage Finch, he encouraged Anne’s writing. Her husband’s support was practical. He began collecting a portfolio of her 56 poems, writing them out by hand and making corrective changes. One significant change involved Anne’s pen name, which Heneage changed from “Areta” to “Ardelia”. * The peace and seclusion at Eastwell fostered the development of Finch’s poetry, and the retirement in the country provided her with her most productive writing period. Her work revealed her growing knowledge of contemporary poetic conventions, and the themes she addressed included metaphysics, the beauty of nature (as expressed in “A Nocturnal Reverie”), and the value of friendship (as in “The Petition for an Absolute Retreat”). Return to public life * By the early 18th century the political climate in England had generally improved for the Finches. King William died in 1702, and his death was followed by the succession to the throne of Queen Anne, the daughter of James II, who had died in 1701. With these developments, the Finches felt ready to embrace a more public lifestyle. Heneage Finch ran for a parliamentary seat three times (in 1701, 1705, and 1710), but was never elected. Still, the Finches felt the time was right to leave the seclusion of the country life and move into a house in London. * In London, Anne Finch was encouraged to publish her poetry under her own name. Earlier, in 1691, she had anonymously published some of her poetry. In 1701 she published “The Spleen” anonymously. This well-received reflection on depression would prove to be the most popular of her poems in her lifetime. When the Finches returned to London, Anne acquired some important and influential friends, including renowned writers such as Jonathan Swift and Alexander Pope, who encouraged her to write and publish much more openly. * She was reluctant, as she felt the current social and political climate remained oppressive as far as women were concerned. (In her poem “The Introduction,” which was privately circulated, she reflected on contemporary attitudes toward female poets.) When she published Miscellany Poems, on Several Occasions in 1713, the cover page of the first printing indicated that the collected works (which included 86 poems as well as a play) were “Written by a Lady.” However, on subsequent printings, Finch (as Anne, Countess of Winchilsea) received credit as the author. Lady Winchilsea * Anne Finch became Countess of Winchilsea upon the sudden and unexpected death of Charles Finch on 4 August 1712. As Charles Finch had no children, his uncle Heneage Finch (died 1726) became the Earl of Winchilsea, making Anne the Countess. However, the titles came with a cost. The Finches had to assume Charles Finch’s financial and legal burdens. The issues were eventually settled in the Finches’ favour in 1720, but not before the couple had endured nearly seven years of emotional strain. * During this period, Heneage and Anne Finch faced renewed strains resulting from court politics. When Queen Anne died in 1714, she was succeeded by George I. Subsequently, a Whig government, which was hostile to the Jacobite cause, rose to power. The Jacobite rebellion, which took place in Scotland in 1715, further aggravated the tense political situation. The Finches became greatly concerned about their safety, especially after a friend, Matthew Prior, who shared their political sympathies, was sent to prison. Deteriorating health * All of her worries combined started to take a toll on Anne Finch’s health, which began to seriously deteriorate. For years she had been vulnerable to depression, and in 1715 she became seriously ill. Her later poems reflected her turmoil. In particular, “A Suplication for the joys of Heaven” and “A Contemplation” expressed her concerns about her life and political and spiritual beliefs. * She died in Westminster, London, and her body was returned to Eastwell for burial, according to her previously stated wishes. Her husband produced an obituary that praised her talents as a writer and her virtues as an individual. A portion of it read, “To draw her Ladyship’s just Character, requires a masterly Pen like her own (She being a fine Writer, and an excellent Poet); we shall only presume to say, she was the most faithful Servant to her Royall Mistresse, the best Wife to her Noble Lord, and in every other Relation, publick and private, so illustrious an Example of such extraordinary Endowments, both of Body and Mind, that the Court of England never bred a more accomplished Lady, nor the Church of England a better Christian.” Poetry rediscovered * The only major collection of Anne Finch’s writings that appeared in her lifetime was Miscellany Poems, on Several Occasions. Nearly a century after her death her poetic output had been largely forgotten, until the great English poet William Wordsworth praised her nature poetry in an essay included in his 1815 volume Lyrical Ballads. * A major collection titled The Poems of Anne, Countess of Winchilsea, edited by Myra Reynolds, was published in 1903. For many years it was considered the definitive collection of her writings. It remains the only scholarly collection of Finch’s poetry, and includes all of the poems from Miscellany Poems and poems retrieved from manuscripts. Further, Reynolds’s impressive introduction did as much to re-establish Finch’s reputation as Wordsworth’s previous praise. * Later, The Wellesley Manuscript, which contained 53 unpublished poems, was released. Literary scholars have noted Finch’s distinctive voice and her poems’ intimacy, sincerity, and spirituality. They also expressed appreciation for her experimentation as well as her assured usage of Augustan diction and forms. * According to James Winn (The Review of English Studies, lix, 2008, pp 67–85) Anne Finch is the librettist of Venus and Adonis, with music by John Blow; the work is considered by some scholars to be the first true opera in the English language. In his critical edition of the opera for the Purcell Society, Bruce Wood agrees with Winn. * In 1929, in her classic essay A Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf both critiques Finch’s writing and expresses great admiration for it. In Woolf’s examination of the “female voice” and her search for the history of female writers, she argues that Finch’s writing is “harassed and distracted with hates and grievances,” pointing out that to Finch “men are hated and feared, because they have the power to bar her way to what she wants to do—which is to write.” However, Woolf excuses the flaws she perceives in Finch’s work by claiming that Finch surely had to “encourage herself to write by supposing that what she writes will never be published.” She goes on to acknowledge that in Finch’s work, "Now and again words issue of pure poetry…It was a thousand pities that the woman who could write like that, whose mind was turned to nature, and reflection, should have been forced to anger and bitterness." Woolf goes on in defence of her as a gifted but sometimes understandably misguided example of women’s writing. It is evident that Woolf sympathises deeply with Finch’s plight as a female poet, and though she takes issue with some of the content in Finch’s writing, she expresses grief that Finch is so unknown: "…when one comes to seek out the facts about Lady Winchilsea, one finds, as usual, that almost nothing is known about her." Woolf wishes to know more about “this melancholy lady, who loved wandering in the fields and thinking about unusual things and scorned, so rashly, so unwisely, ‘the dull manage of a servile house.’”

Jessie Pope (18 March 1868– 14 December 1941) was an English poet, writer and journalist, who remains best known for her patriotic motivational poems published during World War I. Wilfred Owen directed his 1917 poem Dulce et Decorum Est at Pope, whose literary reputation has faded into relative obscurity as those of war poets such as Owen and Siegfried Sassoon have grown. Early career Born in Leicester, she was educated at North London Collegiate School. She was a regular contributor to Punch, The Daily Mail and The Daily Express, also writing for Vanity Fair, Pall Mall Magazine and the Windsor. Prose editor A lesser-known literary contribution was Pope’s discovery of Robert Tressell’s novel The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists, when his daughter mentioned the manuscript to her after his death. Pope recommended it to her publisher, who commissioned her to abridge it before publication. This, a partial bowdlerisation, moulded it to a standard working-class tragedy while greatly downgrading its socialist political content. Verse Other works include Paper Pellets (1907), an anthology of humorous verse. She also wrote verses for children’s books, such as The Cat Scouts (Blackie, 1912) and the following eulogy to her friend, Bertram Fletcher Robinson (published in the Daily Express on Saturday 26 January 1907): Good Bye, kind heart; our benisons preceding, Shall shield your passing to the other side. The praise of your friends shall do your pleading In love and gratitude and tender pride. To you gay humorist and polished writer, We will not speak of tears or startled pain. You made our London merrier and brighter, God bless you, then, until we meet again! War poetry Pope’s war poetry was originally published in The Daily Mail; it encouraged enlistment and handed a white feather to youths who would not join the colours. Nowadays, this poetry is considered to be jingoistic, consisting of simple rhythms and rhyme schemes, with extensive use of rhetorical questions to persuade (and sometimes pressure) young men to join the war. This extract from Who’s for the Game? is typical in style: Who’s for the game, the biggest that’s played, The red crashing game of a fight? Who’ll grip and tackle the job unafraid? And who thinks he’d rather sit tight? Other poems, such as The Call (1915)– “Who’s for the trench– Are you, my laddie?”– expressed similar sentiments. Pope was widely published during the war, apart from newspaper publication producing three volumes: Jessie Pope’s War Poems (1915), More War Poems (1915) and Simple Rhymes for Stirring Times (1916). Criticism Her treatment of the subject is markedly in stark contrast to the anti-war stance of soldier poets such as Owen and Siegfried Sassoon. Many of these men found her work distasteful, Owen in particular. His poem Dulce et Decorum Est was a direct response to her writing, originally dedicated “To Jessie Pope etc.”. A later draft amended this as “To a certain Poetess”, later being removed completely to turn the poem into a general reproach on anyone sympathetic to the war. Pope is prominently remembered first for her pro-war poetry, but also as a representative of homefront female propagandists such as Mrs Humphry Ward, May Wedderburn Cannan, Emma Orczy, and entertainers such as Vesta Tilley. In particular, the poem “War Girls”, similar in structure to her pro-war poetry, states how "No longer caged and penned up/They’re going to keep their end up/Until the khaki soldier boys come marching back". Though largely unknown at the time, the War poets like Nichols, Sassoon and Owen, as well as later writers such as Edmund Blunden, Robert Graves, and Richard Aldington, have come to define the experience of the First World War. Reappraisal Pope’s work is today often presented in schools and anthologies as a counterpoint to the work of the War Poets, a comparison by which her pro-war work suffers both technically and politically. Some writers have attempted a partial re-appraisal of her work as an early pioneer of English women in the workforce, while still critical of both the content and artistic merit of her war poetry. Reminded that Pope was primarily a humourist and writer of light verse, her success in publishing and journalism during the pre-war era, when she was described as the “foremost woman humourist” of her day has been overshadowed by her propagandistic war poems. Her verse has been mined for sympathetic portrayals of the poor and powerless, of women urged to be strong and self-reliant. Her portrayal of the Suffragettes in a pair of counterpointed 1909 poems makes a case both for and against their actions. Later life After the war, Pope continued to rewrite, penning a short novel, poems—many of which continued to reflect upon the war and its aftermath—and books for children. She married a widower bank manager in 1929, when she was 61, and moved from London to Fritton, near Great Yarmouth. She died on 14 December 1941 in Devon.

Sir Henry John Newbolt, CH (6 June 1862– 19 April 1938) was an English poet, novelist and historian. He also had a very powerful role as a government adviser, particularly on Irish issues and with regard to the study of English in England. He is perhaps best remembered for his poems "Vitaï Lampada" and “Drake’s Drum”. Background Henry John Newbolt was born in Bilston, Wolverhampton (then located in Staffordshire, but now in the West Midlands), son of the vicar of St Mary’s Church, the Rev. Henry Francis Newbolt, and his second wife, Emily. After his father’s death, the family moved to Walsall, where Henry was educated. Education Newbolt attended Queen Mary’s Grammar School, Walsall, and Caistor Grammar School, from where he gained a scholarship to Clifton College, where he was head of the school (1881) and edited the school magazine. His contemporaries there included John McTaggart, Arthur Quiller-Couch, Roger Fry, William Birdwood, Francis Younghusband and Douglas Haig. Graduating from Corpus Christi College, Oxford, Newbolt was called to the bar at Lincoln’s Inn in 1887 and practised until 1899. Family He married Margaret Edwina Duckworth of the prominent publishing family; they had two children; a boy, Francis and a daughter, Celia. In 1914 Celia Newbolt married Lt. Col. Sir Ralph Dolignon Furse (1887–1973), the Head of Recruitment at HM Colonial Service from 1931 to 1948; they had four children. Lady Furse died in 1975. Subsequently it became apparent that behind the prim Edwardian exterior lay a far more complicated domestic life for Newbolt: a ménage à trois. His wife had a long-running lesbian affair with her cousin and childhood love, Ella Coltman. One of his poems, in which he refers to someone as “dearest”, is entitled “To E.C.” He became Coltman’s lover after a couple of years of marriage, and according to Chitty he divided his time between the two women so there was no jealousy. Publications * His first book was a novel, Taken from the Enemy (1892), and in 1895 he published a tragedy, Mordred; but it was the publication of his ballads, Admirals All (1897), that created his literary reputation. By far the best-known of these is "Vitaï Lampada". They were followed by other volumes of stirring verse, including The Island Race (1898), The Sailing of the Long-ships (1902), Songs of the Sea (1904) and Songs of the Fleet (1910). * In 1914, Newbolt published Aladore, a fantasy novel about a bored but dutiful knight who abruptly abandons his estate and wealth to discover his heart’s desire and woo a half-fae enchantress. It is a tale filled with allegories about the nature of youth, service, individuality and tradition. It was reissued in a new edition by Newcastle Publishing Company in 1975. "Vitaï Lampada" * Probably the best known of all Newbolt’s poems which was written in 1892, and for which he is now chiefly remembered is "Vitaï Lampada". The title is taken from a quotation by Lucretius and means “the torch of life”. It refers to how a schoolboy, a future soldier, learns selfless commitment to duty in cricket matches in the famous Close at Clifton College: * There’s a breathless hush in the Close to-night— * Ten to make and the match to win— * A bumping pitch and a blinding light, * An hour to play and the last man in. * And it’s not for the sake of a ribboned coat, * Or the selfish hope of a season’s fame, * But his captain’s hand on his shoulder smote * “Play up! play up! and play the game!” * The sand of the desert is sodden red,— * Red with the wreck of a square that broke;— * The Gatling’s jammed and the Colonel dead, * And the regiment blind with dust and smoke. * The river of death has brimmed his banks, * And England’s far, and Honour a name, * But the voice of a schoolboy rallies the ranks: * “Play up! play up! and play the game!” * This is the word that year by year, * While in her place the school is set, * Every one of her sons must hear, * And none that hears it dare forget. * This they all with a joyful mind * Bear through life like a torch in flame, * And falling fling to the host behind— * “Play up! play up! and play the game!” * The engagement mentioned in verse two is the Battle of Abu Klea in Sudan in January 1885 during the unsuccessful expedition to rescue General Gordon. Frederick Gustavus Burnaby is the colonel referred to in the line “The Gatling’s jammed and the Colonel’s dead...”, although it was a Gardner machine gun which jammed. The poem was both highly regarded and repeatedly satirised by those who experienced World War I. Drake’s Drum * According to legend a drum owned by Sir Francis Drake will beat in times of national crisis and the spirit of Drake will return to aid his country. Sir Henry reinforced the myth with his 1897 poem Drake’s Drum, “Drake he’s in his hammock an’ a thousand mile away...”, which has been widely anthologised. * The poem has been set to both classical and folk tunes. “'Drakes Drum” is the first of five poetic settings by the composer Charles Villiers Stanford. Stanford has two song cycles, both using the poetry of Newbolt, the Songs of the Sea and also Songs of the Fleet. Monthly Review * Between 1900 and 1905, Newbolt was the editor of the Monthly Review. He was also a member of the Athenaeum and the Coefficients dining club. War and history * At the start of the First World War, Newbolt– along with over 20 other leading British writers– was brought into the War Propaganda Bureau which had been formed to promote Britain’s interests during the war and maintain public opinion in favour of the war. * He subsequently became Controller of Telecommunications at the Foreign Office. His poems about the war include “The War Films”, printed on the leader page of The Times on 14 October 1916, which seeks to temper the shock effect on cinema audiences of footage of the Battle of the Somme. * Newbolt was knighted in 1915 and was appointed Companion of Honour in 1922. * In 1921 he had been the author of a government Report entitled “The Teaching of English in England” which established the foundations for modern English Studies and professionalised the forms of teaching of English Literature. It established a canon, argued that English must become the linguistic and literary standard throughout the British Empire, and even proposed salary rates for lecturers. For many years it was a standard work for English teachers in teacher training Colleges. * Newbolt was also part of the inner advisory circle of Herbert Asquith’s government and would subsequently advise governments on policy in Ireland. Legacy * In his home town of Bilston, a public house was named after him, and a blue plaque is displayed on Barclay’s bank near the street where he was born. * In June 2013 a campaign was launched by The Black Country Bugle to erect a statue in Newbolt’s memory. * Recordings were made of Newbolt reading some of his own poems. They were on four 78rpm sides in the Columbia Records “International Educational Society” Lecture series, Lecture 92 (D40181/2). Death * Newbolt died at his home in Campden Hill, Kensington, London, on 19 April 1938, aged 75. A blue plaque there commemorates his residency. He is buried in the churchyard of St Mary’s church on an island in the lake on the Orchardleigh Estate of the Duckworth family in Somerset. Works * * Mordred: A Tragedy– an Arthurian drama * Admirals All (1897)– including Drake’s Drum * The Old Country (1906) * The New June (1909) * Aladore (1914)– a novel * St George’s Day & Other Poems (1918)– published by John Murray. * The Naval History of the Great War: Based on Official Documents Volumes IV and V– Newbolt took over after Sir Julian Corbett died * A Ballad of Sir Pertab Singh * He Fell among Thieves * Story of the Oxfordshire & Buckinghamshire Light Infantry (The Old 43rd & 52nd Regiments) * My World as in My Time (1932)– his autobiography * A Note on the History of Submarine War * Submarine and Anti-Submarine (1919) Sources and references * * This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). “article name needed”. Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. External links * * Works by Henry John Newbolt at Project Gutenberg * Works by or about Henry Newbolt at Internet Archive * Works by Henry Newbolt at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks) * Text of the poem Mors Janua . References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Newbolt

Samuel Johnson (18 September 1709 – 13 December 1784), often referred to as Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions to English literature as a poet, essayist, moralist, literary critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer. Johnson was a devout Anglican and committed Tory, and has been described as “arguably the most distinguished man of letters in English history”. He is also the subject of “the most famous single biographical work in the whole of literature,” James Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson. Born in Lichfield, Staffordshire, Johnson attended Pembroke College, Oxford for just over a year, before his lack of funds forced him to leave. After working as a teacher, he moved to London, where he began to write for The Gentleman’s Magazine. His early works include the biography Life of Mr Richard Savage, the poems London and The Vanity of Human Wishes, and the play Irene.

Henry James Pye (/paɪ/; 10 February 1744– 11 August 1813) was an English poet. Pye was Poet Laureate from 1790 until his death. He was the first poet laureate to receive a fixed salary of £27 instead of the historic tierce of Canary wine (though it was still a fairly nominal payment; then as now the Poet Laureate had to look to extra sales generated by the prestige of the office to make significant money from the Laureateship). Life Pye was born in London, the son of Henry Pye of Faringdon House in Berkshire, and his wife, Mary James. He was the nephew of Admiral Thomas Pye. He was educated at Magdalen College, Oxford. His father died in 1766, leaving him a legacy of debt amounting to £50,000, and the burning of the family home further increased his difficulties. In 1784 he was elected Member of Parliament for Berkshire. He was obliged to sell the paternal estate, and, retiring from Parliament in 1790, became a police magistrate for Westminster. Although he had no command of language and was destitute of poetic feeling, his ambition was to obtain recognition as a poet, and he published many volumes of verse. Of all he wrote his prose Summary of the Duties of a Justice of the Peace out of Sessions (1808) is most worthy of record. He was made poet laureate in 1790, perhaps as a reward for his faithful support of William Pitt the Younger in the House of Commons. The appointment was looked on as ridiculous, and his birthday odes were a continual source of contempt. The 20th century British historian Lord Blake called Pye “the worst Poet Laureate in English history with the possible exception of Alfred Austin.” Indeed, Pye’s successor, Robert Southey, wrote in 1814: “I have been rhyming as doggedly and dully as if my name had been Henry James Pye.” After his death, Pye remained one of the unfortunate few who have been classified as a “poetaster.” As a prose writer, Pye was far from contemptible. He had a fancy for commentaries and summaries. His “Commentary on Shakespeare’s commentators”, and that appended to his translation of the Poetics, contain some noteworthy matter. A man, who, born in 1745, could write “Sir Charles Grandison is a much more unnatural character than Caliban,” may have been a poetaster but was certainly not a fool. He died in Pinner, Middlesex on 11 August 1813. Pye married twice. He had two daughters by his first wife. He married secondly in 1801 Martha Corbett, by whom he had a son Henry John Pye, who in 1833 inherited the Clifton Hall, Staffordshire estate of a distant cousin and who was High Sheriff of Staffordshire in 1840. Works Prose * Summary of the Duties of a Justice of the Peace out of Sessions (1808) * The Democrat (1795) * The Aristocrat (1799) Poetry * Poems on Various Subjects (1787), first substantial collection of Pye’s verse * Adelaide: a Tragedy in Five Acts (1800) * Alfred (1801) Translations * Aristotle’s Poetics (1792) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_James_Pye

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (baptized 26 May 1689– 21 August 1762) was an English aristocrat, letter writer and poet. Lady Mary is today chiefly remembered for her letters, particularly her letters from travels to the Ottoman Empire, as wife to the British ambassador to Turkey, which have been described by Billie Melman as “the very first example of a secular work by a woman about the Muslim Orient”. Aside from her writing, Lady Mary is also known for introducing and advocating for smallpox inoculation to Britain after her return from Turkey. Her writings usually address and challenge the hindering contemporary social attitudes towards women and their intellectual and social growth. Early life and education Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, Mary Pierrepont, was born in May 1689; her baptism took place on 26 May, at a few days old, at St. Paul’s Church in Covent Garden. She was the eldest child of Evelyn Pierrepont, 1st Duke of Kingston-upon-Hull, and his first wife, Mary (Fielding) Pierrepont. Her mother had three more children, two girls and a boy, before dying in October 1692. The children were raised by their Pierrepont grandmother until Mary was nine years old. Lady Mary was then passed to the care of her father upon her grandmother’s death. She began her education in her father’s home. Family holdings were extensive, including Thoresby Hall and Holme Pierrepont Hall in Nottinghamshire, and a house in West Dean in Wiltshire. To supplement the instruction of a despised governess, Lady Mary used the library in her father’s mansion, Thoresby Hall in Nottinghamshire, to “steal” her education, teaching herself Latin, a language reserved for men at the time. By 1705, at the age of fourteen or fifteen, Mary Pierrepont had written two albums filled with poetry, a brief epistolary novel, and a prose-and-verse romance modeled after Aphra Behn’s Voyage to the Isle of Love (1684). She also corresponded with two bishops, Thomas Tenison and Gilbert Burnet. Marriage and embassy to Ottoman Empire By 1710 Lady Mary had two possible suitors to choose from: Edward Wortley Montagu and Clotworthy Skeffington. Lady Mary corresponded with Edward Wortley Montagu via letters from 28 March 1710 to 2 May 1711. After May 1711 there was a break in contact between Lady Mary and Edward Wortley Montagu. Mary’s father, now Marquess of Dorchester, rejected Wortley Montagu as a prospect because he refused to entail his estate on a possible heir. Her father pressured her to marry Clotworthy Skeffington, heir to an Irish peerage. In order to avoid marriage to Skeffington, she eloped with Wortley. The marriage license is dated 17 August 1712, the marriage probably took place on 23 August 1712. The early years of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu’s married life were spent in the country. She had a son, Edward Wortley Montagu the younger, on 16 May 1713, in London. A couple of months later, on 1 July 1713 Lady Mary’s brother, aged twenty, died of smallpox and left behind two children. On 13 October 1714, her husband accepted post as Junior Commissioner of Treasury. When Lady Mary joined him in London, her wit and beauty soon made her a prominent figure at court. She was among the society of George I and the Prince of Wales, and counted amongst her friends Molly Skerritt, Lady Walpole, John, Lord Hervey, Mary Astell, Sarah Churchill, Duchess of Marlborough, Alexander Pope, John Gay, and Abbé Antonio Conti. In December 1715, Lady Mary contracted smallpox. She survived, but while she was ill someone circulated the satirical “court eclogues” she had been writing. One of the poems was read as an attack on Caroline, Princess of Wales, in spite of the fact that the “attack” was voiced by a character who was herself heavily satirized. In 1716, Edward Wortley Montagu was appointed Ambassador at Istanbul. In August 1716, Lady Mary accompanied him to Vienna, and thence to Adrianople and Istanbul. He was recalled in 1717, but they remained at Istanbul until 1718. While away from England, the Wortley Montagu’s had a daughter on 19 January 1718, who would grow up to be Mary, Countess of Bute. After an unsuccessful delegation between Austria and Turkey/Ottoman Empire, they set sail for England via the Mediterranean, and reached London on 2 October 1718. The story of this voyage and of her observations of Eastern life is told in Letters from Turkey, a series of lively letters full of graphic descriptions; Letters is often credited as being an inspiration for subsequent female travelers/writers, as well as for much Orientalist art. During her visit she was sincerely charmed by the beauty and hospitality of the Ottoman women she encountered, and she recorded her experiences in a Turkish bath. She also recorded a particularly amusing incident in which a group of Turkish women at a bath in Sofia, horrified by the sight of the stays she was wearing, exclaimed that "the husbands in England were much worse than in the East, for [they] tied up their wives in little boxes, the shape of their bodies". Lady Mary wrote about misconceptions previous travelers, specifically male travelers, had recorded about the religion, traditions and the treatment of women in the Ottoman Empire. Her gender and class status provided her with access to female spaces, that were closed off to males. Her personal interactions with Ottoman women enabled her to provide a more accurate account of Turkish women, their dress, habits, traditions, limitations and liberties. Lady Mary returned to the West with knowledge of the Ottoman practice of inoculation against smallpox, known as variolation. Ottoman smallpox inoculation Lady Mary Wortley Montagu defied convention most memorably by introducing smallpox inoculation to Western medicine after witnessing it during her travels and stay in the Ottoman Empire. In the Ottoman Empire, she visited the women in their segregated zenanas, making friends and learning about Turkish customs. There she witnessed the practice of inoculation against smallpox—variolation—which she called engrafting, and wrote home about it a number of her letters. Variolation used live smallpox virus in the pus taken from a smallpox blister in a mild case of the disease and introduced it into scratched skin of a previously uninfected person to promote immunity to the disease. Lady Mary’s brother had died of smallpox in 1713 and her own famous beauty had been marred by a bout with the disease in 1715. Lady Mary was eager to spare her children, thus, in March 1718 she had her nearly five-year-old son inoculated with the help of Embassy surgeon Charles Maitland. On her return to London, she enthusiastically promoted the procedure, but encountered a great deal of resistance from the medical establishment, because it was an Oriental folk treatment process. In April 1721, when a smallpox epidemic struck England, she had her daughter inoculated by Charles Maitland, the same physician who had inoculated her son at the Embassy in Turkey, and publicized the event. This was the first such operation done in Britain. She persuaded Princess Caroline to test the treatment. In August 1721, seven prisoners at Newgate Prison awaiting execution were offered the chance to undergo variolation instead of execution: they all survived and were released. Controversy over smallpox inoculation intensified, however, Caroline, Princess of Wales was convinced. The Princess’s two daughters were successfully inoculated in April 1722 by French-born surgeon Claudiius Amyand. In response to the general fear of inoculation, Lady Mary, under a pseudonym, wrote and published an article describing and advocating in favor of inoculation in September 1722. In later years, Edward Jenner, who was 13 years old when Lady Mary died, developed the much safer technique of vaccination using cowpox instead of smallpox. As vaccination gained acceptance, variolation gradually fell out of favor. Later years After returning to England, Lady Mary took less interest in court compared to her earlier years. Instead she was more focused on the upbringing of her children, reading, writing and editing her travel letters—which she then chose not to publish. Before starting for the East Lady Mary Wortley Montagu had met Alexander Pope, and during her Embassy travels with her husband, they wrote each other a series of letters. While Pope may have been fascinated by her wit and elegance, Lady Mary’s replies to his letters reveal that she was not equally smitten. Very few letters passed between them after Lady Mary’s return to England, and various reasons have been suggested for the subsequent estrangement. In 1728, Pope attacked Lady Mary in his Dunciad inaugurating a decade in which most of his publications made some sort of allegation against her. Lady Mary went through a series of trials with her children. In 1726 and 1727, Lady Mary’s son ran away from Westminster School several times. He was entrusted to a tutor with strict orders to keep young Edward Montagu abroad. In later years her son managed to return to England without permission and continued to have a strained relationship with both his parents. In August 1736, Lady Mary’s daughter, married John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute, despite her parent’s disapproval of the match. The same year Lady Mary met and fell in love with Francesco Algarotti, Count Algarotti, competing with an equally smitten John Hervey for the Count’s affections. Lady Mary wrote many letters to Algarotti in English and in French after his departure from England in September 1736. In July 1739 Lady Mary departed England ostensibly for health reasons declaring her intentions to winter in the south of France. In reality, she left to visit and live with Algarotti in Venice. Their relationship ended in 1741 after Lady Mary and Algarotti were both on diplomatic mission in Turin. Lady Mary stayed abroad and traveled extensively. After traveling to Venice, Florence, Rome, Genoa and Geneva, she finally settled in Avignon in 1742. She left Avignon in 1746 for Brescia, where she fell ill and stayed for nearly a decade, leaving for Lovere in 1754. After August 1756, she resided in Venice and Padua and saw Algarotti again in November. Lady Mary exchanged letters with her daughter, Lady Bute, discussing topics such as philosophy, literature, and the education of girls, as well as conveying details of her geographical and social surroundings. Lady Mary received news of her husband Edward Wortley Montagu’s death in 1761 and left Venice for England. En route to London, she handed her Embassy Letters to the Rev. Benjamin Sowden of Rotterdam, for safe keeping and “to be dispos’d of as he thinks proper”. Lady Mary reached London in January 1762, and died in the year of her return, on 21 August 1762. Important works and literary place Although Lady Mary Wortley Montagu is now best known for her Embassy Letters, she wrote poetry and essays as well. A number of Lady Mary’s poems and essays were printed in her lifetime, either without or with her permission, in newspapers, in miscellanies, and independently. Montagu did not intend to publish her poetry, but it did circulate widely, in manuscript, among members of her own social circle. Lady Mary was highly suspicious of any idealizing literary language. She wrote most often in heroic couplets, a serious poetic form to employ, and, according to Susan Staves,"excelled at “answer poems.”. Some of her widely anthologized poems include “Constantinople” and “Epistle from Mrs. Yonge to her Husband.” “Constantinople,” written January 1718, is a beautiful poem in heroic couplets describing Britain and Turkey through human history, and representing the state of mind “of knaves, coxcombs, the mob, and party zealous—all characteristic of the London of her time.”. “Epistle from Mrs. Yonge to her Husband,” written 1724, stages a letter from Mrs. Yonge to her libertine husband and exposes the social double standard which led to the shaming and distress of Mrs. Yonge after her divorce. In 1737 and 1738, Lady Mary published anonymously a political periodical called the Nonsense of Common-Sense, supporting the Robert Walpole government (the title was a reference to a journal of the liberal opposition entitled Common Sense). She wrote six Town Eclogues. She wrote notable letters describing her travels through Europe and the Ottoman Empire; these appeared after her death in three volumes. Lady Mary corresponded with Anne Wortley and wrote courtship letters to her future husband Edward Wortley Montagu, as well as love letters to Francesco Algarotti. She corresponded with notable writers, intellectuals and aristocrats of her day. She wrote gossip letters and letters berating the vagaries of fashionable people to her sister, Lady Mar, and exchanged intellectual letters with her adult daughter, Lady Bute. Although, not published during her lifetime, her letters from Turkey were clearly intended for print. She revised them extensively and gave a transcript to the Rev. Benjamin Sowden in Rotterdam in 1761. During the twentieth century Lady Mary’s letters were edited separately from her essays, poems and plays. Montagu’s Turkish letters were to prove an inspiration to later generations of European women travelers and writers. In particular, Montagu staked a claim to the authority of women’s writing, due to their ability to access private homes and female-only spaces where men were not permitted. The title of her published letters refers to “Sources that Have Been Inaccessible to Other Travellers”. The letters themselves frequently draw attention to the fact that they present a different (and, Montagu asserts, more accurate) description than that provided by previous (male) travelers: “You will perhaps be surpriz’d at an Account so different from what you have been entertaind with by the common Voyage-writers who are very fond of speaking of what they don’t know.”. Montagu provides an intimate description of the women’s bathhouse in Sofia, in which she derides male descriptions of the bathhouse as a site for unnatural sexual practices, instead insisting that it was “the Women’s coffee house, where all the news of the Town is told, Scandal invented, etc”. However, Montagu’s detailed descriptions of nude Oriental beauties provided inspiration for male artists such as Ingres, who restored the explicitly erotic content that Montagu had denied. In general, Montagu dismisses the quality of European travel literature of the 18th century as nothing more than "trite observations…superficial…[of] boys [who] only remember where they met with the best wine or the prettyest women.". Montagu’s Turkish letters were frequently cited by imperial women travelers, more than a century after her journey. Such writers cited Montagu’s assertion that women travelers could gain an intimate view of Turkish life that was not available to their male counterparts. However, they also added corrections or elaborations to her observations. In 1739 a book was printed by an unknown author under the pseudonym “Sophia, a person of quality”, titled Woman not Inferior to Man. This book is often attributed to Lady Mary. Her Letters and Works were published in 1837. Montagu’s octogenarian granddaughter Lady Louisa Stuart contributed to this, anonymously, an introductory essay called Biographical Anecdotes of Lady M. W. Montagu, from which it was clear that Stuart was troubled by her grandmother’s focus on sexual intrigues and did not see Lady Mary Wortley Montagu’s Account of the Court of George I at his Accession as history. However, Montagu’s historical observations, both in the “Anecdotes” and the “Turkish Embassy Letters,” prove quite accurate when put in context. Despite the availability of her work in print and the revival efforts of Feminist scholars, the complexity and brilliance of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu’s extensive body of work has not yet been recognized to the fullest.

Charlotte Mary Mew (15 November 1869– 24 March 1928) was an English poetess, whose work spans the cusp between Victorian poetry and Modernism. She was born in Bloomsbury, London, the daughter of the architect Frederick Mew, who designed Hampstead town hall, and Anna Kendall.The marriage produced seven children. Charlotte, nicknamed Lotti by her family, attended Gower Street School, where she became infatuated with the school’s headmistress, Lucy Harrison, and lectures at University College London. Her father died in 1898 without making adequate provision for his family; two of her siblings suffered from mental illness, and were committed to institutions, and three others died in early childhood leaving Charlotte, her mother and her sister, Anne. Charlotte and Anne made a pact never to marry for fear of passing on insanity to their children. (One author calls Charlotte “almost certainly chastely lesbian)”. Through most of her adult life, Mew wore masculine attire and kept her hair short, adopting the appearance of a dandy.

Adrian Mitchell (24 October 1932– 20 December 2008) was an English poet, novelist and playwright. A former journalist, he became a noted figure on the British Left. For almost half a century he was the foremost poet of the country’s anti-Bomb movement. The critic Kenneth Tynan called him “the British Mayakovsky”. Mitchell sought in his work to counteract the implications of his own assertion that, “Most people ignore most poetry because most poetry ignores most people.” In a National Poetry Day poll in 2005 his poem “Human Beings” was voted the one most people would like to see launched into space. In 2002 he was nominated, semi-seriously, Britain’s “Shadow Poet Laureate”. Mitchell was for some years poetry editor of the New Statesman, and was the first to publish an interview with the Beatles. His work for the Royal Shakespeare Company included Peter Brook’s US and the English version of Peter Weiss’s Marat/Sade. Ever inspired by the example of his own favourite poet and precursor William Blake, about whom he wrote the acclaimed Tyger for the National Theatre, his often angry output swirled from anarchistic anti-war satire, through love poetry to, increasingly, stories and poems for children. He also wrote librettos. The Poetry Archive identified his creative yield as hugely prolific. The Times said that Mitchell’s had been a “forthright voice often laced with tenderness.” His poems on such topics as nuclear war, Vietnam, prisons and racism had become “part of the folklore of the Left. His work was often read and sung at demonstrations and rallies.” Biography Early life and career Adrian Mitchell was born near Hampstead Heath, North London. His mother, Kathleen Fabian, was a Fröbel-trained nursery school teacher and his father, Jock Mitchell, a research chemist from Cupar in Fife. He was educated at Monkton Combe School in Bath. He then went to Greenways School, at Ashton Gifford House in Wiltshire, run at the time by a friend of his mother. This, said Mitchell, was “a school in Heaven, where my first play, The Animals’ Brains Trust, was staged when I was nine to my great satisfaction.” His schooling was completed as a boarder at Dauntsey’s School, after which he did his National Service in the RAF. He commented that this “confirmed (his) natural pacificism”. He went on to study English at Christ Church, Oxford, where he was taught by J. R. R. Tolkien’s son. He became chairman of the university’s poetry society and the literary editor of Isis magazine. On graduating Mitchell got a job as a reporter on the Oxford Mail and, later, at the Evening Standard in London. “Inheriting enough money to live on for a year, I wrote my first novel and my first TV play. Soon afterwards I became a freelance journalist, writing about pop music for the Daily Mail and TV for the pre-tabloid Sun and the Sunday Times. I quit journalism in the mid-Sixties and since then have been a free-falling poet, playwright and writer of stories.” Career Mitchell gave frequent public readings, particularly for left-wing causes. Satire was his speciality. Commissioned to write a poem about Prince Charles and his special relationship (as Prince of Wales) with the people of Wales, his measured response was short and to the point: “Royalty is a neurosis. Get well soon.” In “Loose Leaf Poem”, from Ride the Nightmare, he wrote: My brain socialist My heart anarchist My eyes pacifist My blood revolutionary Mitchell was in the habit of stipulating in any preface to his collections: “None of the work in this book is to be used in connection with any examination whatsoever.” His best-known poem, “To Whom It May Concern”, was his bitterly sarcastic reaction to the televised horrors of the Vietnam War. The poem begins: I was run over by the truth one day. Ever since the accident I’ve walked this way So stick my legs in plaster Tell me lies about Vietnam He first read it to thousands of nuclear disarmament protesters who, having marched through central London on CND’s first new format one-day Easter March, finally crammed into Trafalgar Square on the afternoon of Easter Day 1964. As Mitchell delivered his lines from the pavement in front of the National Gallery, angry demonstrators in the square below scuffled with police. In 1972 he confronted then-prime minister Edward Heath about germ warfare and the war in Northern Ireland. He was later responsible for the well-respected stage adaptation of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, a production of the Royal Shakespeare Company that premiered in November 1998. Over the years he updated the poem to take into account recent events. “He never let up. Most calls—'Can you do this one, Adrian?'—were answered, 'Sure, I’ll be there.' His reading of 'Tell Me Lies’ at a City Hall benefit just before the 2003 invasion of Iraq was electrifying. Of course, he couldn’t stop that war, but he performed as if he could.” One Remembrance Sunday he laid the Peace Pledge Union’s White Poppy wreath on the Cenotaph in Whitehall. On one International Conscientious Objectors’ Day he read a poem at the ceremony at the Conscientious Objectors Commemorative Stone in Tavistock Square in London. Fellow writers could be effusive in their tributes. John Berger said that, “Against the present British state he opposes a kind of revolutionary populism, bawdiness, wit and the tenderness sometimes to be found between animals.” Angela Carter once wrote that he was “a joyous, acrid and demotic tumbling lyricist Pied Piper, determinedly singing us away from catastrophe.” Ted Hughes: “In the world of verse for children, nobody has produced more surprising verse or more genuinely inspired fun than Adrian Mitchell.” Mitchell died at the age of 76 in a North London hospital from a suspected heart attack. For two months he had been suffering from pneumonia. Two days earlier he had completed what turned out to be his last poem, “My Literary Career So Far”. He intended it as a Christmas gift to “all the friends, family and animals he loved”. “Adrian”, said fellow-poet Michael Rosen, “was a socialist and a pacifist who believed, like William Blake, that everything human was holy. That’s to say he celebrated a love of life with the same fervour that he attacked those who crushed life. He did this through his poetry, his plays, his song lyrics and his own performances. Through this huge body of work, he was able to raise the spirits of his audiences, in turn exciting, inspiring, saddening and enthusing them.... He has sung, chanted, whispered and shouted his poems in every kind of place imaginable, urging us to love our lives, love our minds and bodies and to fight against tyranny, oppression and exploitation.” In 2009 Frances Lincoln Children’s Books published an adaptation of Ovid: Shapeshifters: tales from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, written by Mitchell and illustrated by Alan Lee. Family Mitchell is survived by his wife, the actress Celia Hewitt, whose bookshop, Ripping Yarns, is in Highgate, and their two daughters Sasha and Beattie. He also has two sons and a daughter from his previous marriage to Maureen Bush: Briony, Alistair and Danny. There are nine grandchildren: Robin, Arthur, Charlotte, Natasha, Zoe, Caitlin, Annie, Lola and Lilly. Selected bibliography * If You See Me Comin′ (Jonathan Cape, 1962) * Poems (Jonathan Cape, 1964; 978-0224608732) * Out Loud (Cape Goliard, 1968) * Ride the Nightmare (Cape, 1971; ISBN 978-0224005630) * Tyger: A Celebration Based on the Life and Works of William Blake (Cape, 1971; ISBN 978-0224006521) * The Apeman Cometh (Cape, 1975; ISBN 978-0224011471) * Man Friday, novel (Futura, 1975; ISBN 978-0860072744) * For Beauty Douglas: Collected Poems 1953–79, illus. Ralph Steadman (Allison & Busby, 1981; ISBN 978-0850313994) * On the Beach at Cambridge: New Poems (Allison and Busby, 1984; ISBN 978-0850315639) * Nothingmas Day, illus. John Lawrence (Allison & Busby, 1984; ISBN 978-0850315325) * Love Songs of World War Three: Collected Stage Lyrics (Allison and Busby, 1988; ISBN 978-0850319910) * All My Own Stuff, illus. Frances Lloyd (Simon & Schuster, 1991; ISBN 978-0750004466) * Adrian Mitchell’s Greatest Hits– The Top Forty, illus. Ralph Steadman (Bloodaxe Books, 1991; ISBN 978-1852241643) * Blue Coffee: Poems 1985–1996 (Bloodaxe, 1996; 1997 reprint, ISBN 978-1852243623) * Heart on the Left: Poems 1953–1984 (Bloodaxe, 1997; ISBN 978-1852244255) * Balloon Lagoon and Other Magic Islands of Poetry, illus. Tony Ross (Orchard Books, 1997; ISBN 978-1860396595) * Nobody Rides the Unicorn, illus. Stephen Lambert (Corgi Children’s, new edn 2000; ISBN 978-0552546171) * All Shook Up: Poems 1997–2000 (Bloodaxe, 2000; ISBN 978-1852245139) * The Shadow Knows: Poems 2001–2004 (Bloodaxe, 2004) * Tell Me Lies: Poems 2005–2008, illus. Ralph Steadman (Bloodaxe, 2009; ISBN 978-1852248437) * Umpteen Pockets, illus. Tony Ross (Orchard Books, 2009; ISBN 978-1408303634) * Daft as a Doughnut (Orchard Books, 2009; ISBN 978-1408308073) * Shapeshifters: Tales from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, illus. Alan Lee (Frances Lincoln, 2009; ISBN 978-1845075361) * Come on Everybody: Poems 1953–2008 (Bloodaxe, 2012; ISBN 978-1852249465) Awards * * 1961 Eric Gregory Award * 1966 PEN Translation Prize * 1971 Tokyo Festival Television Film Award * 2005 CLPE Poetry Award (shortlist) for Daft as a Doughnut References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adrian_Mitchell

John Drinkwater (1 June 1882 – 25 March 1937) was an English poet and dramatist. Drinkwater was born in Leytonstone, London, and worked as an insurance clerk. In the period immediately before the First World War he was one of the group of poets associated with the Gloucestershire village of Dymock, along with Rupert Brooke and others. In 1919 he had his first major success with his play Abraham Lincoln. He followed it with others in a similar vein, including Mary Stuart and Oliver Cromwell. In 1924, his Lincoln play was adapted for a two-reel short film made by Lee DeForest and J. Searle Dawley featuring Frank McGlynn Sr. as Lincoln, and made in DeForest's Phonofilm sound-on-film process. He had published poetry since The Death of Leander in 1906; the first volume of his Collected Poems was published in 1923. He also compiled anthologies and wrote literary criticism (e.g. Swinburne: an estimate (1913)), and later became manager of Birmingham Repertory Theatre. He was married to Daisy Kennedy, the ex-wife of Benno Moiseiwitsch. Papers relating to John Drinkwater and collected by his stepdaughter are held at the University of Birmingham Special Collections. John Drinkwater made recordings in Columbia Records' International Educational Society Lecture series. They include Lecture 10 – a lecture on The Speaking of Verse (Four 78rpm sides, Cat no. D 40018-40019), and Lecture 70 John Drinkwater reading his own poems (Four 78rpm sides, Cat no. D 40140-40141). Death and commemoration Drinkwater died in London in 1937. He is buried at Piddington, Oxfordshire, where he had spent summer holidays as a child. A road in Leytonstone, formerly a 1960s council estate, is named after Drinkwater, as is a small development of modern houses in Piddington. References Wikipedia – en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Drinkwater_(playwright)

Ernest Christopher Dowson (2 August 1867– 23 February 1900) was an English poet, novelist, and short-story writer, often associated with the Decadent movement. He was born in Lee, London, in 1867. His great-uncle was Alfred Domett, a poet and politician who became Premier of New Zealand and had allegedly been the subject of Robert Browning’s poem “Waring.” Dowson attended The Queen’s College, Oxford, but left in March 1888 before obtaining a degree.

Andrew Marvell (31 March 1621– 16 August 1678) was an English metaphysical poet, satirist and politician who sat in the House of Commons at various times between 1659 and 1678. During the Commonwealth period he was a colleague and friend of John Milton. His poems range from the love-song “To His Coy Mistress”, to evocations of an aristocratic country house and garden in “Upon Appleton House” and “The Garden”, the political address “An Horatian Ode upon Cromwell’s Return from Ireland”, and the later personal and political satires “Flecknoe” and “The Character of Holland”. Early life Marvell was born in Winestead-in-Holderness, East Riding of Yorkshire, near the city of Kingston upon Hull, the son of a Church of England clergyman also named Andrew Marvell. The family moved to Hull when his father was appointed Lecturer at Holy Trinity Church there, and Marvell was educated at Hull Grammar School. A secondary school in the city, the Andrew Marvell Business and Enterprise College, is now named after him. At the age of 13, Marvell attended Trinity College, Cambridge and eventually received a BA degree. A portrait of Marvell attributed to Godfrey Kneller hangs in Trinity College’s collection. Afterwards, from the middle of 1642 onwards, Marvell probably travelled in continental Europe. He may well have served as a tutor for an aristocrat on the Grand Tour, but the facts are not clear on this point. While England was embroiled in the civil war, Marvell seems to have remained on the continent until 1647. It is not known exactly where his travels took him, except that he was in Rome in 1645 and Milton later reported that Marvell had mastered four languages, including French, Italian and Spanish. First poems and Marvell’s time at Nun Appleton Marvell’s first poems, which were written in Latin and Greek and published when he was still at Cambridge, lamented a visitation of the plague and celebrated the birth of a child to King Charles I and Queen Henrietta Maria. He only belatedly became sympathetic to the successive regimes during the Interregnum after Charles I’s execution on 30 January 1649. His “Horatian Ode”, a political poem dated to early 1650, responds with lament to the regicide even as it praises Oliver Cromwell’s return from Ireland. Circa 1650–52, Marvell served as tutor to the daughter of the Lord General Thomas Fairfax, who had recently relinquished command of the Parliamentary army to Cromwell. He lived during that time at Nun Appleton Hall, near York, where he continued to write poetry. One poem, “Upon Appleton House, To My Lord Fairfax”, uses a description of the estate as a way of exploring Fairfax’s and Marvell’s own situation in a time of war and political change. Probably the best-known poem he wrote at this time is “To His Coy Mistress”. Anglo-Dutch War and employment as Latin secretary During the period of increasing tensions leading up to the First Anglo-Dutch War of 1653, Marvell wrote the satirical “Character of Holland,” repeating the then current stereotype of the Dutch as “drunken and profane”: "This indigested vomit of the Sea,/ Fell to the Dutch by Just Propriety.” He became a tutor to Cromwell’s ward, William Dutton, in 1653, and moved to live with his pupil at the house of John Oxenbridge in Eton. Oxenbridge had made two trips to Bermuda, and it is thought that this inspired Marvell to write his poem Bermudas. He also wrote several poems in praise of Cromwell, who was by this time Lord Protector of England. In 1656 Marvell and Dutton travelled to France, to visit the Protestant Academy of Saumur. In 1657, Marvell joined Milton, who by that time had lost his sight, in service as Latin secretary to Cromwell’s Council of State at a salary of £200 a year, which represented financial security at that time. Oliver Cromwell died in 1658. He was succeeded as Lord Protector by his son Richard. In 1659 Marvell was elected Member of Parliament for Kingston-upon-Hull in the Third Protectorate Parliament. He was paid a rate of 6 shillings, 8 pence per day during sittings of parliament, a financial support derived from the contributions of his constituency. He was re-elected MP for Hull in 1660 for the Convention Parliament. After the Restoration The monarchy was restored to Charles II in 1660. Marvell avoided punishment for his own co-operation with republicanism, and he helped convince the government of Charles II not to execute John Milton for his antimonarchical writings and revolutionary activities. The closeness of the relationship between the two former colleagues is indicated by the fact that Marvell contributed an eloquent prefatory poem, entitled “On Mr. Milton’s Paradise Lost”, to the second edition of Milton’s epic Paradise Lost. According to a biographer: “Skilled in the arts of self-preservation, he was not a toady.” In 1661 Marvell was re-elected MP for Hull in the Cavalier Parliament. He eventually came to write several long and bitterly satirical verses against the corruption of the court. Although circulated in manuscript form, some finding anonymous publication in print, they were too politically sensitive and thus dangerous to be published under his name until well after his death. Marvell took up opposition to the 'court party’, and satirised them anonymously. In his longest verse satire, Last Instructions to a Painter, written in 1667, Marvell responded to the political corruption that had contributed to English failures during the Second Anglo-Dutch War. The poem did not find print publication until after the Revolution of 1688–9. The poem instructs an imaginary painter how to picture the state without a proper navy to defend them, led by men without intelligence or courage, a corrupt and dissolute court, and dishonest officials. Of another such satire, Samuel Pepys, himself a government official, commented in his diary, “Here I met with a fourth Advice to a Painter upon the coming in of the Dutch and the End of the War, that made my heart ake to read, it being too sharp and so true.” From 1659 until his death in 1678, Marvell was serving as London agent for the Hull Trinity House, a shipmasters’ guild. He went on two missions to the continent, one to the Dutch Republic and the other encompassing Russia, Sweden, and Denmark. He spent some time living in a cottage on Highgate Hill in north London, where his time in the area is recorded by a bronze plaque that bears the following inscription: Four feet below this spot is the stone step, formerly the entrance to the cottage in which lived Andrew Marvell, poet, wit, and satirist; colleague with John Milton in the foreign or Latin secretaryship during the Commonwealth; and for about twenty years M.P. for Hull. Born at Winestead, Yorkshire, 31st March, 1621, died in London, 18th August, 1678, and buried in the church of St. Giles-in-the-Fields. This memorial is placed here by the London County Council, December, 1898. A floral sundial in the nearby Lauderdale House bears an inscription quoting lines from of his poem “The Garden”. He died suddenly in 1678, while in attendance at a popular meeting of his old constituents at Hull. His health had previously been remarkably good; and it was supposed by many that he was poisoned by some of his political or clerical enemies. Marvell was buried in the church of St Giles in the Fields in central London. His monument, erected by his grateful constituency, bears the following inscription: Near this place lyeth the body of Andrew Marvell, Esq., a man so endowed by Nature, so improved by Education, Study, and Travel, so consummated by Experience, that, joining the peculiar graces of Wit and Learning, with a singular penetration and strength of judgment; and exercising all these in the whole course of his life, with an unutterable steadiness in the ways of Virtue, he became the ornament and example of his age, beloved by good men, feared by bad, admired by all, though imitated by few; and scarce paralleled by any. But a Tombstone can neither contain his character, nor is Marble necessary to transmit it to posterity; it is engraved in the minds of this generation, and will be always legible in his inimitable writings, nevertheless. He having served twenty years successfully in Parliament, and that with such Wisdom, Dexterity, and Courage, as becomes a true Patriot, the town of Kingston-upon-Hull, from whence he was deputed to that Assembly, lamenting in his death the public loss, have erected this Monument of their Grief and their Gratitude, 1688. It may be noted that his epitaph pays more tribute to his political career than his poetry. Prose works Marvell also wrote anonymous prose satires criticizing the monarchy and Catholicism, defending Puritan dissenters, and denouncing censorship. The Rehearsal Transpros’d, an attack on Samuel Parker, was published in two parts in 1672 and 1673. In 1676, Mr. Smirke; or The Divine in Mode, a work critical of intolerance within the Church of England, was published together with a “Short Historical Essay, concerning General Councils, Creeds, and Impositions, in matters of Religion.” Marvell’s pamphlet An Account of the Growth of Popery and Arbitrary Government in England, published in late 1677, alleged that: “There has now for diverse Years, a design been carried on, to change the Lawfull Government of England into an Absolute Tyranny, and to convert the established Protestant Religion into down-right Popery”. John Kenyon described it as “one of the most influential pamphlets of the decade” and G. M. Trevelyan called it: “A fine pamphlet, which throws light on causes provocative of the formation of the Whig party”. A 1678 work published anonymously ("by a Protestant") in defense of John Howe against the attack of his fellow-dissenter, the severe Calvinist Thomas Danson, is also probably by Marvell. Its full title is Remarks upon a late disingenuous discourse, writ by one T.D. under the pretence de causa Dei, and of answering Mr. John Howe’s letter and postscript of God’s prescience, &c., affirming, as the Protestant docrine, that GOd doth by efficacious influence universally move and determine men to all their actions, even to those that are most wicked. Views Although Marvell became a Parliamentarian, he was not a Puritan. He had flirted briefly with Catholicism as a youth, and was described in his thirties (on the Saumur visit) as “a notable English Italo-Machiavellian”. During his lifetime, his prose satires were much better known than his verse. Vincent Palmieri noted that Marvell is sometimes known as the “British Aristides” for his incorruptible integrity in life and poverty at death. Many of his poems were not published until 1681, three years after his death, from a collection owned by Mary Palmer, his housekeeper. After Marvell’s death she laid dubious claim to having been his wife, from the time of a secret marriage in 1667. Marvell’s poetic style T. S. Eliot wrote of Marvell’s style that 'It is more than a technical accomplishment, or the vocabulary and syntax of an epoch; it is, what we have designated tentatively as wit, a tough reasonableness beneath the slight lyric grace’. He also identified Marvell and the metaphysical school with the 'dissociation of sensibility’ that occurred in 17th-century English literature; Eliot described this trend as 'something which... happened to the mind of England... it is the difference between the intellectual poet and the reflective poet’. Poets increasingly developed a self-conscious relationship to tradition, which took the form of a new emphasis on craftsmanship of expression and an idiosyncratic freedom in allusions to Classical and Biblical sources. Marvell’s most celebrated lyric, “To His Coy Mistress”, combines an old poetic conceit (the persuasion of the speaker’s lover by means of a carpe diem philosophy) with Marvell’s typically vibrant imagery and easy command of rhyming couplets. Other works incorporate topical satire and religious themes. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrew_Marvell

Sydney Thompson Dobell (5 April 1824– 22 August 1874) was an English poet and critic, and a member of the so-called Spasmodic school. He was born at Cranbrook, Kent. His father, John Dobell, was a wine merchant, his mother a daughter of Samuel Thompson (1766–1837), a London political reformer. The family moved to Cheltenham when Dobell was twelve years old. He was educated privately, and never attended either school or university. He refers to this in some lines on Cheltenham College in imitation of Chaucer, written in his eighteenth year. After a five-year engagement he married, in 1844, Emily Fordham, a lady of good family. Acquaintance with James Stansfeld (subsequently Sir James Stansfeld) and with the Birmingham preacher-politician George Dawson fed the young enthusiast’s ardour for the liberalism of the day, and later led to the foundation of the Society of the Friends of Italy.