Aphra Behn (14 December 1640? April 1689) was an English playwright, poet, translator and fiction writer from the Restoration era. As one of the first English women to earn her living by her writing, she broke cultural barriers and served as a literary role model for later generations of women authors. Rising from obscurity, she came to the notice of Charles II, who employed her as a spy in Antwerp. Upon her return to London and a probable brief stay in debtors’ prison, she began writing for the stage. She belonged to a coterie of poets and famous libertines such as John Wilmot, Lord Rochester. She wrote under the pastoral pseudonym Astrea. During the turbulent political times of the Exclusion Crisis, she wrote an epilogue and prologue that brought her into legal trouble; she thereafter devoted most of her writing to prose genres and translations. A staunch supporter of the Stuart line, she declined an invitation from Bishop Burnet to write a welcoming poem to the new king William III. She died shortly after.She is remembered in Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own: “All women together ought to let flowers fall upon the tomb of Aphra Behn which is, most scandalously but rather appropriately, in Westminster Abbey, for it was she who earned them the right to speak their minds.” Her grave is not included in the Poets’ Corner but lies in the East Cloister near the steps to the church. Life and work Versions of her early life Information regarding Behn’s life is scant, especially regarding her early years. This may be due to intentional obscuring on Behn’s part. One version of Behn’s life tells that she was born to a barber named John Amis and his wife Amy. Another story has Behn born to a couple named Cooper. The Histories And Novels of the Late Ingenious Mrs. Behn (1696) states that Behn was born to Bartholomew Johnson, a barber, and Elizabeth Denham, a wet-nurse. Colonel Thomas Colepeper, the only person who claimed to have known her as a child, wrote in Adversaria that she was born at “Sturry or Canterbury” to a Mr Johnson and that she had a sister named Frances. Another contemporary, Anne Finch, wrote that Behn was born in Wye in Kent, the “Daughter to a Barber”. In some accounts the profile of her father fits Eaffrey Johnson.Behn was born during the buildup of the English Civil War, a child of the political tensions of the time. One version of Behn’s story has her travelling with a Bartholomew Johnson to Surinam. He was said to die on the journey, with his wife and children spending some months in the country, though there is no evidence of this. During this trip Behn said she met an African slave leader, whose story formed the basis for one of her most famous works, Oroonoko. It is possible that she acted a spy in the colony. There is little verifiable evidence to confirm any one story. In Oroonoko Behn gives herself the position of narrator and her first biographer accepted the assumption that Behn was the daughter of the lieutenant general of Surinam, as in the story. There is little evidence that this was the case, and none of her contemporaries acknowledge any aristocratic status. There is also no evidence that Oroonoko existed as an actual person or that any such slave revolt, as is featured in the story, really happened. Writer Germaine Greer has called Behn “a palimpsest; she has scratched herself out,” and biographer Janet Todd noted that Behn “has a lethal combination of obscurity, secrecy and staginess which makes her an uneasy fit for any narrative, speculative or factual. She is not so much a woman to be unmasked as an unending combination of masks”. It is notable that her name is not mentioned in tax or church records. During her lifetime she was also known as Ann Behn, Mrs Bean, agent 160 and Astrea. Career Shortly after her supposed return to England from Surinam in 1664, Behn may have married Johan Behn (also written as Johann and John Behn). He may have been a merchant of German or Dutch extraction, possibly from Hamburg. He died or the couple separated soon after 1664, however from this point the writer used “Mrs Behn” as her professional name.Behn may have had a Catholic upbringing. She once commented that she was “designed for a nun,” and the fact that she had so many Catholic connections, such as Henry Neville who was later arrested for his Catholicism, would have aroused suspicions during the anti-Catholic fervour of the 1680s. She was a monarchist, and her sympathy for the Stuarts, and particularly for the Catholic Duke of York may be demonstrated by her dedication of her play The Rover II to him after he had been exiled for the second time. Behn was dedicated to the restored King Charles II. As political parties emerged during this time, Behn became a Tory supporter.By 1666 Behn had become attached to the court, possibly through the influence of Thomas Culpeper and other associates. The Second Anglo-Dutch War had broken out between England and the Netherlands in 1665, and she was recruited as a political spy in Antwerp on behalf of King Charles II, possibly under the auspices of courtier Thomas Killigrew. This is the first well-documented account we have of her activities. Her code name is said to have been Astrea, a name under which she later published many of her writings. Her chief role was to establish an intimacy with William Scot, son of Thomas Scot, a regicide who had been executed in 1660. Scot was believed to be ready to become a spy in the English service and to report on the doings of the English exiles who were plotting against the King. Behn arrived in Bruges in July 1666, probably with two others, as London was wracked with plague and fire. Behn’s job was to turn Scot into a double agent, but there is evidence that Scot betrayed her to the Dutch.Behn’s exploits were not profitable however; the cost of living shocked her, and she was left unprepared. One month after arrival, she pawned her jewellry. King Charles was slow in paying (if he paid at all), either for her services or for her expenses whilst abroad. Money had to be borrowed so that Behn could return to London, where a year’s petitioning of Charles for payment was unsuccessful. It may be that she was never paid by the crown. A warrant was issued for her arrest, but there is no evidence it was served or that she went to prison for her debt, though apocryphally it is often given as part of her history. Forced by debt and her husband’s death, Behn began to work for the King’s Company and the Duke’s Company players as a scribe. She had, however, written poetry up until this point. While she is recorded to have written before she adopted her debt, John Palmer said in a review of her works that, “Mrs. Behn wrote for a livelihood. Playwriting was her refuge from starvation and a debtor’s prison.” The theatres that had been closed under Cromwell were now re-opening under Charles II, plays enjoying a revival. Her first play, The Forc’d Marriage, was staged in 1670, followed by The Amorous Prince (1671). After her third play, The Dutch Lover, failed, Behn falls off the public record for three years. It is speculated that she went travelling again, possibly in her capacity as a spy. She gradually moved towards comic works, which proved more commercially successful. Her most popular works included The Rover. Behn became friends with notable writers of the day, including John Dryden, Elizabeth Barry, John Hoyle, Thomas Otway and Edward Ravenscroft, and was acknowledged as a part of the circle of the Earl of Rochester. Behn often used her writings to attack the parliamentary Whigs claiming, “In public spirits call’d, good o’ th’ Commonwealth... So tho’ by different ways the fever seize... in all ’tis one and the same mad disease.” This was Behn’s reproach to parliament which had denied the king funds. Final years and death In 1688, in the year before her death, she published A Discovery of New Worlds, a translation of a French popularisation of astronomy, Entretiens sur la pluralité des mondes, by Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle, written as a novel in a form similar to her own work, but with her new, religiously oriented preface. In all she would write and stage 19 plays, contribute to more, and become one of the first prolific, high-profile female dramatists in Britain. During the 1670s and 1680s she was one of the most productive playwrights in Britain, second only to Poet Laureate John Dryden.In her last four years, Behn’s health began to fail, beset by poverty and debt, but she continued to write ferociously, though it became increasingly hard for her to hold a pen. In her final days, she wrote the translation of the final book of Abraham Cowley’s Six Books of Plants. She died on 16 April 1689, and was buried in the East Cloister Westminster Abbey. The inscription on her tombstone reads: “Here lies a Proof that Wit can never be Defence enough against Mortality.” She was quoted as stating that she had led a “life dedicated to pleasure and poetry.” Published works Behn earned a living writing, one of the earliest Englishwoman to do so. After John Dryden she was the most prolific writer of the English Restoration. Behn was not the first woman in England to publish a play. In 1613 Lady Elizabeth Cary had published The Tragedy of Miriam, in the 1650s Margaret Cavendish published two volumes of plays, and in 1663 a translation of Corneille’s Pompey by Katherine Philips was performed in Dublin and London. Women had been excluded from theatre in the Elizabethan era, but in Restoration England they made up a significant part of the audience and professional actresses played the women’s parts. This changed the nature and themes of Restoration theatre.Behn’s first play The Forc’d Marriage was a romantic tragicomedy on arranged marriages and was staged by the Duke’s Company in September 1670. The performance ran for six nights, which was regarded as a good run for an unknown author. Six months later Behn’s play The Amorous Prince was successfully staged. Again, Behn used the play to comment on the harmful effects of arranged marriages. Behn did not hide the fact that she was a woman, instead she made a point of it. When in 1673 the Dorset Garden Theatre staged The Dutch Lover, critics sabotaged the play on the grounds that the author was a woman. Behn tackled the critics head on in Epistle to the Reader. She argued that women had been held back by their unjust exclusion from education, not their lack of ability. After a three-year publication pause, Behn published four plays in close succession. In 1676 she published Abdelazar, The Town Fop and The Rover. In early 1678 Sir Patient Fancy was published. This succession of box-office successes led to frequent attacks on Behn. She was attacked for her private life, the morality of her plays was questioned and she was accused of plagiarising The Rover. Behn countered these public attacks in the prefaces of her published plays. In the preface to Sir Patient Fancy she argued that she was being singled out because she was a woman, while male playwrights were free to live the most scandalous lives and write bawdy plays.Under Charles II of England prevailing Puritan ethics was reversed in the fashionable society of London. The King associated with playwrights that poured scorn on marriage and the idea of consistency in love. Among the King’s favourite was the Earl of Rochester John Wilmot, who became famous for his cynical libertinism. Behn was a friend of Wilmot and Behn became a bold proponent of sexual freedom for both women and men. Like her contemporary male libertines, she wrote freely about sex. In the infamous poem The Disappointment she wrote a comic account of male impotence from a woman’s perspective. Critics Lisa Zeitz and Peter Thoms contend that the poem “playfully and wittily questions conventional gender roles and the structures of oppression which they support”. In The Dutch Lover Behn forthrightly acknowledged female sexual desire. Critics of Behn were provided with ammunition because of her public liaison with John Hoyle, a bisexual lawyer who scandalised his contemporaries.By the late 1670s Behn was among the leading playwrights of England. Her plays were staged frequently and attended by the King. The Rover became a favourite at the King’s court. Behn became heavily involved in the political debate about the succession. Because Charles II had no heir a prolonged political crisis ensued. Mass hysteria commenced as in 1678 the rumoured Popish Plot suggested the King should be replaced with his Roman Catholic brother James. Political parties developed, the Whigs wanted to exclude James, while the Tories did not believe succession should be altered in any way. Charles II eventually dissolved the Cavalier Parliament and James II succeeded him in 1685. Behn supported the Tory position and in the two years between 1681 and 1682 produced five plays to discredit the Whigs. The London audience, mainly Tory sympathisers, attended the plays in large numbers. But Behn was arrested on the order of King Charles II when she used one of the plays to attack James Scott, Duke of Monmouth, the illegitimate son of the King.As audience numbers declined, theatres staged mainly old works to save costs. Nevertheless, Behn published The Luckey Chance in 1686. In response to the criticism levelled at they play she articulated a long and passionate defence of women writers. Her play The Emperor of the Moon was published and staged in 1687, it became one of her longest running plays. Behn stopped writing plays and turned to prose fiction. Today she is mostly known for the novels she wrote in the later part of her life. Her first novel was the three-part Love-Letters Between a Nobleman and His Sister, published between 1682 and 1687. The novels were inspired by a contemporary scandal, which saw Lord Grey elope with his sister-in-law Lady Henrietta Berkeley. At the time of publication Love Letters was very popular and went through more than 16 editions. Today Behn’s prose work is critically acknowledged as having been important to the development of the English novel. Following Behn’s death, new female dramatists such as Delarivier Manley, Mary Pix, Susanna Centlivre and Catherine Trotter acknowledged Behn as their most vital predecessor, who opened up public space for women writers.In 1688, less than a year before her death, Behn published Oroonoko: or, The Royal Oroonoko, the story of the enslaved Oroonoko and his love Imoinda. It was based on Behn’s travel to Surinam twenty years earlier. The novel became a great success. In 1696 it was adapted for the stage by Thomas Southerne and continuously performed throughout the 18th century. In 1745 the novel was translated into French, going through seven French editions. As abolitionism gathered pace in the late 18th century the novel was celebrated as the first anti-slavery novel. Legacy and re-evaluation After her death in 1689 Behn’s literary work was marginalised and dismissed outright. Until the mid-20th century Behn was repeatedly dismissed as morally depraved minor writer. In the 18th century her literary work was scandalised as lewd by Thomas Brown, William Wycherley, Richard Steele and John Duncombe. Alexander Pope penned the famous lines “The stage how loosely does Astrea tread, Who fairly puts all characters to bed!”. In the 19th century Mary Hays, Matilda Betham, Alexander Dyce, Jane Williams and Julia Kavanagh decided that Behn’s writings were unfit to read, because they were corrupt and deplorable. Among the few critics who believed that Behn was an important writer were Leigh Hunt, William Forsyth and William Henry Hudson.The life and times of Behn were recounted by a long line of biographers, among them Dyce, Edmund Gosse, Ernest Bernbaum, Montague Summers, Vita Sackville-West, Virginia Woolf, George Woodcock, William J. Cameron and Frederick Link.Of Behn’s considerable literary output only Oroonoko was seriously considered by literary scholars. The late 18th century the novel is regarded as one of the first abolitionist and humanitarian novel published in the English language. It is credited as precursor to Jean-Jaques Rousseau’s Discourses on Inequality. Since the 1970s Behn’s literary works have been re-evaluated by feminist critics and writers. Behn was rediscovered as a significant female writer by Maureen Duffy, Angeline Goreau, Ruth Perry, Hilda Lee Smith, Moira Ferguson, Jane Spencer, Dale Spender, Elaine Hobby and Janet Todd. This led to the reprinting of her works. The Rover was republished in 1967, Oroonoko was republished in 1973, Love Letters between a Nobleman and His Sisters was published again in 1987 and The Lucky Chance was reprinted in 1988. Montague Summers, an author of scholarly works on the English drama of the 17th century, published a six-volume collection of her work, in hopes of rehabilitating her reputation. Summers was fiercely passionate about the work of Behn and found himself incredibly devoted to the appreciation of 17th century literature. Felix Schelling wrote in The Cambridge History of English Literature, that she was “a very gifted woman, compelled to write for bread in an age in which literature... catered habitually to the lowest and most depraved of human inclinations,” and that, “Her success depended upon her ability to write like a man.” Edmund Gosse remarked that she was, “...the George Sand of the Restoration”.The criticism of Behn’s poetry focuses on the themes of gender, sexuality, femininity, pleasure, and love. A feminist critique tends to focus on Behn’s inclusion of female pleasure and sexuality in her poetry, which was a radical concept at the time she was writing. One critic, Alison Conway, views Behn as instrumental to the formation of modern thought around the female gender and sexuality: "Behn wrote about these subjects before the technologies of sexuality we now associate were in place, which is, in part, why she proves so hard to situate in the trajectories most familiar to us”. Virginia Woolf wrote, in A Room of One’s Own: All women together, ought to let flowers fall upon the grave of Aphra Behn... for it was she who earned them the right to speak their minds... Behn proved that money could be made by writing at the sacrifice, perhaps, of certain agreeable qualities; and so by degrees writing became not merely a sign of folly and a distracted mind but was of practical importance. Adaptations of Behn in Literature Behn’s life has been adapted for the stage in the 2014 play Empress of the Moon: The Lives of Aphra Behn by Chris Braak, and the 2015 play [exit Mrs Behn] or, The Leo Play by Christopher VanderArk. She is one of the characters in the 2010 play Or, by Liz Duffy Adams. Behn appears as a character in Daniel O’Mahony’s Newtons Sleep, in Phillip Jose Farmer’s The Magic Labyrinth and Gods of Riverworld, in Molly Brown’s Invitation to a Funeral (1999), and in Diana Norman’s The Vizard Mask. She is referred to in Patrick O’Brian’s novel Desolation Island.

Sarah Orne Jewett (September 3, 1849– June 24, 1909) was an American novelist, short story writer and poet, best known for her local color works set along or near the southern seacoast of Maine. Jewett is recognized as an important practitioner of American literary regionalism. Early life Jewett’s family had been residents of New England for many generations, and Sarah Orne Jewett was born in South Berwick, Maine. Her father was a doctor specializing in “obstetrics and diseases of women and children.” and Jewett often accompanied him on his rounds, becoming acquainted with the sights and sounds of her native land and its people. As treatment for rheumatoid arthritis, a condition that developed in early childhood, Jewett was sent on frequent walks and through them also developed a love of nature. In later life, Jewett often visited Boston, where she was acquainted with many of the most influential literary figures of her day; but she always returned to South Berwick, small seaports near which were the inspiration for the towns of “Deephaven” and “Dunnet Landing” in her stories. Jewett was educated at Miss Olive Rayne’s school and then at Berwick Academy, graduating in 1866. She supplemented her education through an extensive family library. Jewett was “never overtly religious,” but after she joined the Episcopal church in 1871, she explored less conventional religious ideas. For example, her friendship with Harvard law professor Theophilus Parsons stimulated an interest in the teachings of Emanuel Swedenborg, an eighteenth-century Swedish scientist and theologian, who believed that the Divine “was present in innumerable, joined forms—a concept underlying Jewett’s belief in individual responsibility.” Career She published her first important story in the Atlantic Monthly at age 19, and her reputation grew throughout the 1870s and 1880s. Her literary importance arises from her careful, if subdued, vignettes of country life that reflect a contemporary interest in local color rather than plot. Jewett possessed a keen descriptive gift that William Dean Howells called “an uncommon feeling for talk—I hear your people.” Jewett made her reputation with the novella The Country of the Pointed Firs (1896). A Country Doctor (1884), a novel reflecting her father and her early ambitions for a medical career, and A White Heron (1886), a collection of short stories are among her finest work. Some of Jewett’s poetry was collected in Verses (1916), and she also wrote three children’s books. Willa Cather described Jewett as a significant influence on her development as a writer, and “feminist critics have since championed her writing for its rich account of women’s lives and voices.” Later life On September 3, 1902, Jewett was injured in a carriage accident that all but ended her writing career. She was paralyzed by a stroke in March 1909, and she died on June 24 after suffering another. The Georgian home of the Jewett family, built in 1774 overlooking Central Square at South Berwick, is now a National Historic Landmark and Historic New England museum called the Sarah Orne Jewett House. Jewett never married, but she established a close friendship with writer Annie Adams Fields (1834–1915) and her husband, publisher James Thomas Fields, editor of the Atlantic Monthly. After the sudden death of James Fields in 1881, Jewett and Annie Fields lived together for the rest of Jewett’s life in what was then termed a “Boston marriage”. Some modern scholars have speculated that the two were lovers. Both women “found friendship, humor, and literary encouragement” in one another’s company, traveling to Europe together and hosting “American and European literati.” In France Jewett met Thérèse Blanc-Bentzon with whom she had long corresponded and who translated some of her stories for publication in France.

Helen Joy Davidman (18 April 1915 – 13 July 1960) was an American poet and writer. Often referred to as a child prodigy, she earned a master's degree from Columbia University in English literature at age twenty in 1935. For her book of poems, Letter to a Comrade, she won the Yale Series of Younger Poets Competition in 1938 and the Russell Loines Award for Poetry in 1939. She was the author of several books, including two novels.

Sojourner Truth (born Isabella ("Bell") Baumfree; C. 1797– November 26, 1883) was an African-American abolitionist and women’s rights activist. Truth was born into slavery in Swartekill, Ulster County, New York, but escaped with her infant daughter to freedom in 1826. After going to court to recover her son, in 1828 she became the first black woman to win such a case against a white man. She gave herself the name Sojourner Truth in 1843 after she became convinced that God had called her to leave the city and go into the countryside “testifying the hope that was in her.” Her best-known speech was delivered extemporaneously, in 1851, at the Ohio Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio. The speech became widely known during the Civil War by the title “Ain’t I a Woman?,” a variation of the original speech re-written by someone else using a stereotypical Southern dialect; whereas Sojourner Truth was from New York and grew up speaking Dutch as her first language. During the Civil War, Truth helped recruit black troops for the Union Army; after the war, she tried unsuccessfully to secure land grants from the federal government for former slaves. In 2014, Truth was included in Smithsonian magazine’s list of the "100 Most Significant Americans of All Time". Early years Truth was one of the ten or twelve children born to James and Elizabeth Baumfree (or Bomefree). Colonel Hardenbergh bought James and Elizabeth Baumfree from slave traders and kept their family at his estate in a big hilly area called by the Dutch name Swartekill (just north of present-day Rifton), in the town of Esopus, New York, 95 miles (153 km) north of New York City. Charles Hardenbergh inherited his father’s estate and continued to enslave people as a part of that estate’s property. When Charles Hardenbergh died in 1806, nine-year-old Truth (known as Belle), was sold at an auction with a flock of sheep for $100 to John Neely, near Kingston, New York. Until that time, Truth spoke only Dutch. She later described Neely as cruel and harsh, relating how he beat her daily and once even with a bundle of rods. Neely sold her in 1808, for $105, to Martinus Schryver of Port Ewen, a tavern keeper, who owned her for eighteen months. Schryver sold her in 1810 to John Dumont of West Park, New York. Although this fourth owner was kindly disposed toward her, considerable tension existed between Truth and Dumont’s second wife, Elizabeth Waring Dumont, who harassed her and made her life more difficult. (John Dumont’s first wife, Sarah “Sally” Waring Dumont (Elizabeth’s sister), died around 1805, five years before he bought Truth.) Around 1815, Truth met and fell in love with a slave named Robert from a neighboring farm. Robert’s owner (Charles Catton, Jr., a landscape painter) forbade their relationship; he did not want the people he enslaved to have children with people he was not enslaving, because he would not own the children. One day Robert sneaked over to see Truth. When Catton and his son found him, they savagely beat Robert until Dumont finally intervened, and Truth never saw Robert again. He later died some years later, perhaps as a result of the injuries, and the experience haunted Truth throughout her life. Truth eventually married an older slave named Thomas. She bore five children: James, her firstborn, who died in childhood, Diana (1815), fathered by either Robert or John Dumont, and Peter (1821), Elizabeth (1825), and Sophia (ca. 1826), all born after she and Thomas united. Freedom The state of New York began, in 1799, to legislate the abolition of slavery, although the process of emancipating those people enslaved in New York was not complete until July 4, 1827. Dumont had promised to grant Truth her freedom a year before the state emancipation, “if she would do well and be faithful.” However, he changed his mind, claiming a hand injury had made her less productive. She was infuriated but continued working, spinning 100 pounds of wool, to satisfy her sense of obligation to him. Late in 1826, Truth escaped to freedom with her infant daughter, Sophia. She had to leave her other children behind because they were not legally freed in the emancipation order until they had served as bound servants into their twenties. She later said “I did not run off, for I thought that wicked, but I walked off, believing that to be all right.” She found her way to the home of Isaac and Maria Van Wagenen in New Paltz, who took her and her baby in. Isaac offered to buy her services for the remainder of the year (until the state’s emancipation took effect), which Dumont accepted for $20. She lived there until the New York State Emancipation Act was approved a year later. Truth learned that her son Peter, then five years old, had been sold illegally by Dumont to an owner in Alabama. With the help of the Van Wagenens, she took the issue to court and in 1828, after months of legal proceedings, she got back her son, who had been abused by those who were enslaving him. Truth became one of the first black women to go to court against a white man and win the case. Truth had a life-changing religious experience during her stay with the Van Wagenens, and became a devout Christian. In 1829 she moved with her son Peter to New York City, where she worked as a housekeeper for Elijah Pierson, a Christian Evangelist. While in New York, she befriended Mary Simpson, a grocer on John Street who claimed she had once been enslaved by George Washington. They shared an interest in charity for the poor and became intimate friends. In 1832, she met Robert Matthews, also known as Prophet Matthias, and went to work for him as a housekeeper at the Matthias Kingdom communal colony. Elijah Pierson died, and Robert Matthews and Truth were accused of stealing from and poisoning him. Both were acquitted of the murder, though Matthews was convicted of lesser crimes, served time, and moved west. In 1839, Truth’s son Peter took a job on a whaling ship called the Zone of Nantucket. From 1840 to 1841, she received three letters from him, though in his third letter he told her he had sent five. Peter said he also never received any of her letters. When the ship returned to port in 1842, Peter was not on board and Truth never heard from him again. “The Spirit Calls Me” 1843 was a turning point for Truth. She became a Methodist, and on June 1, she changed her name to Sojourner Truth. She told friends: “The Spirit calls me, and I must go” and left to make her way traveling and preaching about the abolition of slavery. At that time, Truth began attending Millerite Adventist campmeetings. However, that did not last since Jesus failed to appear in 1843 and then again in 1844. Like many others disappointed, Truth distanced herself from her Millerite friends for a while. In 1844, she joined the Northampton Association of Education and Industry in Northampton, Massachusetts. Founded by abolitionists, the organization supported women’s rights and religious tolerance as well as pacifism. There were, in its four-and-a-half year history, a total of 240 members, though no more than 120 at any one time. They lived on 470 acres (1.9 km2), raising livestock, running a sawmill, a gristmill, and a silk factory. While there, Truth met William Lloyd Garrison, Frederick Douglass, and David Ruggles. In 1846, the group disbanded, unable to support itself. In 1845, she joined the household of George Benson, the brother-in-law of William Lloyd Garrison. In 1849, she visited John Dumont before he moved west. Truth started dictating her memoirs to her friend Olive Gilbert, and in 1850 William Lloyd Garrison privately published her book, The Narrative of Sojourner Truth: A Northern Slave. That same year, she purchased a home in what would become the village of Florence in Northampton for $300, and spoke at the first National Women’s Rights Convention in Worcester, Massachusetts. In 1854, with proceeds from sales of the Narrative and cartes-de-visite entitled “I sell the shadow to support the substance,” she paid off the mortgage held by her friend from the Community, Samuel L. Hill. “Ain’t I a Woman?” In 1851, Truth joined George Thompson, an abolitionist and speaker, on a lecture tour through central and western New York State. In May, she attended the Ohio Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio, where she delivered her famous extemporaneous speech on women’s rights, later known as “Ain’t I a Woman.” Her speech demanded equal human rights for all women as well as for all blacks. The convention was organized by Hannah Tracy and Frances Dana Barker Gage, who both were present when Truth spoke. Different versions of Truth’s words have been recorded, with the first one published a month later by Marius Robinson, a newspaper owner and editor who was in the audience. Robinson’s recounting of the speech included no instance of the question “Ain’t I a Woman?” Twelve years later in May 1863, Gage published another, very different, version. In it, Truth’s speech pattern had characteristics of Southern slaves, and the speech included sentences and phrases that Robinson didn’t report. Gage’s version of the speech became the historic standard version, and is known as “Ain’t I a Woman?” because that question was repeated four times. It is highly unlikely that Truth’s own speech pattern was Southern in nature, as she was born and raised in New York, and she spoke only Dutch until she was nine years old. In contrast to Robinson’s report, Gage’s 1863 version included Truth saying her 13 children were sold away from her into slavery. Truth is widely believed to have had five children, with one sold away, and was never known to boast more children. Gage’s 1863 recollection of the convention conflicts with her own report directly after the convention: Gage wrote in 1851 that Akron in general and the press in particular were largely friendly to the woman’s rights convention, but in 1863 she wrote that the convention leaders were fearful of the “mobbish” opponents. Other eyewitness reports of Truth’s speech told a calm story, one where all faces were “beaming with joyous gladness” at the session where Truth spoke; that not “one discordant note” interrupted the harmony of the proceedings. In contemporary reports, Truth was warmly received by the convention-goers, the majority of whom were long-standing abolitionists, friendly to progressive ideas of race and civil rights. In Gage’s 1863 version, Truth was met with hisses, with voices calling to prevent her from speaking. Over the next 10 years, Truth spoke before dozens, perhaps hundreds, of audiences. From 1851 to 1853, Truth worked with Marius Robinson, the editor of the Ohio Anti-Slavery Bugle, and traveled around that state speaking. In 1853, she spoke at a suffragist “mob convention” at the Broadway Tabernacle in New York City; that year she also met Harriet Beecher Stowe. In 1856, she traveled to Battle Creek, Michigan, to speak to a group called the “Friends of Human Progress.” In 1858, someone interrupted a speech and accused her of being a man; Truth opened her blouse and revealed her breasts. Other notable speeches Northampton Camp Meeting—1844, Northampton, Massachusetts: At a camp meeting where she was participating as an itinerant preacher, a band of “wild young men” disrupted the camp meeting, refused to leave, and threatening to burn down the tents. Truth caught the sense of fear pervading the worshipers and hid behind a trunk in her tent, thinking that since she was the only black person present, the mob would attack her first. However, she reasoned with herself and resolved to do something: as the noise of the mob increased and a female preacher was “trembling on the preachers’ stand,” Truth went to a small hill and began to sing “in her most fervid manner, with all the strength of her most powerful voice, the hymn on the resurrection of Christ." Her song, “It was Early in the Morning,” gathered the rioters to her and quieted them. They urged her to sing, preach, and pray for their entertainment. After singing songs and preaching for about an hour, Truth bargained with them to leave after one final song. The mob agreed and left the camp meeting. Abolitionist Convention—1840s, Boston, Massachusetts: William Lloyd Garrison invited Sojourner Truth to give a speech at an annual antislavery convention. Wendell Phillips was supposed to speak after her, which made her nervous since he was known as such a good orator. So Truth sang a song, “I am Pleading for My people,” which was her own original composition sung to the tune of Auld Lang Syne. Mob Convention—September 7, 1853: At the convention, young men greeted her with "a perfect storm,” hissing and groaning. In response, Truth said, “You may hiss as much as you please, but women will get their rights anyway. You can’t stop us, neither”. Sojourner, like other public speakers, often adapted her speeches to how the audience was responding to her. In her speech, Sojourner speaks out for women’s rights. She incorporates religious references in her speech, particularly the story of Esther. She then goes on to say that, just as women in scripture, women today are fighting for their rights. Moreover, Sojourner scolds the crowd for all their hissing and rude behavior, reminding them that God says to “Honor thy father and thy mother.” American Equal Rights Association—May 9–10, 1867: Her speech was addressed to the American Equal Rights Association, and divided into three sessions. Sojourner was received with loud cheers instead of hisses, now that she had a better-formed reputation established. The Call had advertised her name as one of the main convention speakers. For the first part of her speech, she spoke mainly about the rights of black women. Sojourner argued that because the push for equal rights had led to black men winning new rights, now was the best time to give black women the rights they deserve too. Throughout her speech she kept stressing that “we should keep things going while things are stirring” and fears that once the fight for colored rights settles down, it would take a long time to warm people back up to the idea of colored women’s having equal rights. In the second sessions of Sojourner’s speech, she utilized a story from the Bible to help strengthen her argument for equal rights for women. She ended her argument by accusing men of being self-centered, saying, “man is so selfish that he has got women’s rights and his own too, and yet he won’t give women their rights. He keeps them all to himself.” For the final session of Sojourner’s speech, the center of her attention was mainly on women’s right to vote. Sojourner told her audience that she owned her own house, as did other women, and must therefore pay taxes. Nevertheless, they were still unable to vote because they were women. Black women who were enslaved were made to do hard manual work, such as building roads. Sojourner argues that if these women were able to perform such tasks, then they should be allowed to vote because surely voting is easier than building roads. Eighth Anniversary of Negro Freedom—New Year’s Day, 1871: On this occasion the Boston papers related that “...seldom is there an occasion of more attraction or greater general interest. Every available space of sitting and standing room was crowded". She starts off her speech by giving a little background about her own life. Sojourner recounts how her mother told her to pray to God that she may have good masters and mistresses. She goes on to retell how her masters were not good to her, about how she was whipped for not understanding English, and how she would question God why he had not made her masters be good to her. Sojourner admits to the audience that she had once hated white people, but she says once she met her final master, Jesus, she was filled with love for everyone. Once enslaved folks were emancipated, she tells the crowd she knew her prayers had been answered. That last part of Sojourner’s speech brings in her main focus. Some freed enslaved people were living on government aid at that time, paid for by taxpayers. Sojourner announces that this is not any better for those colored people than it is for the members of her audience. She then proposes that black people are given their own land. Because a portion of the South’s population contained rebels that were unhappy with the abolishment of slavery, that region of the United States was not well suited for colored people. She goes on to suggest that colored people be given land out west to build homes and prosper on. On a mission In 1856, Truth bought a neighboring lot in Northampton, but she did not keep the new property for long. On September 3, 1857, she sold all her possessions, new and old, to Daniel Ives and moved to Battle Creek, Michigan, where she rejoined former members of the Millerite Movement who had formed the Seventh-day Adventist Church. Antislavery movements had begun early in Michigan and Ohio. Here, she also joined the nucleus of the Michigan abolitionists, the Progressive Friends, some who she had already met at national conventions. According to the 1860 census, her household in Harmonia included her daughter, Elizabeth Banks (age 35), and her grandsons James Caldwell (misspelled as “Colvin”; age 16) and Sammy Banks (age 8). During the Civil War, Truth helped recruit black troops for the Union Army. Her grandson, James Caldwell, enlisted in the 54th Massachusetts Regiment. In 1864, Truth was employed by the National Freedman’s Relief Association in Washington, D.C., where she worked diligently to improve conditions for African-Americans. In October of that year, she met President Abraham Lincoln. In 1865, while working at the Freedman’s Hospital in Washington, Truth rode in the streetcars to help force their desegregation. Truth is credited with writing a song, “The Valiant Soldiers”, for the 1st Michigan Colored Regiment; it was said to be composed during the war and sung by her in Detroit and Washington, D.C. It is sung to the tune of “John Brown’s Body” or “The Battle Hymn of the Republic”. Although Truth claimed to have written the words, it has been disputed (see “Marching Song of the First Arkansas”). In 1867, Truth moved from Harmonia to Battle Creek. In 1868, she traveled to western New York and visited with Amy Post, and continued traveling all over the East Coast. At a speaking engagement in Florence, Massachusetts, after she had just returned from a very tiring trip, when Truth was called upon to speak she stood up and said “Children, I have come here like the rest of you, to hear what I have to say.” In 1870, Truth tried to secure land grants from the federal government to former enslaved people, a project she pursued for seven years without success. While in Washington, D.C., she had a meeting with President Ulysses S. Grant in the White House. In 1872, she returned to Battle Creek and tried to vote in the presidential election, but was turned away at the polling place. Truth spoke about abolition, women’s rights, prison reform, and preached to the Michigan Legislature against capital punishment. Not everyone welcomed her preaching and lectures, but she had many friends and staunch support among many influential people at the time, including Amy Post, Parker Pillsbury, Frances Gage, Wendell Phillips, William Lloyd Garrison, Laura Smith Haviland, Lucretia Mott, Ellen G. White, and Susan B. Anthony.” Death and legacy Several days before Sojourner Truth died, a reporter came from the Grand Rapids Eagle to interview her. “Her face was drawn and emaciated and she was apparently suffering great pain. Her eyes were very bright and mind alert although it was difficult for her to talk.” Truth died at her Battle Creek home on November 26, 1883. On November 28 her funeral was held at the Congregational-Presbyterian Church officiated by its pastor, the Reverend Reed Stuart. Some of the prominent citizens of Battle Creek acted as pall-bearers. Truth was buried in the city’s Oak Hill Cemetery. The calendar of saints of the Episcopal Church remembers Sojourner Truth annually, together with Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Amelia Bloomer and Harriet Ross Tubman on July 20. The calendar of saints of the Lutheran Church remembers Sojourner Truth together with Harriet Tubman on March 10. A larger-than-life sculpture of Sojourner Truth by artist Tina Allen, was dedicated in 1999, which is the estimated bicentennial of Sojourner’s birth. The 12-foot tall Sojourner monument is cast bronze. Cultural references and commemorations Other honors and commemorations include (by year): 1862– William Wetmore Story’s statue, The Libyan Sibyl, inspired by Sojourner Truth, won an award at the London World Exhibition. 1892– Albion artist Frank Courter is commissioned to paint the meeting between Truth and President Abraham Lincoln. 1969– The leftist group the Sojourner Truth Organization is named after her. The group folded in 1985. 1971– Sojourner Truth Library at New Paltz State University of New York is named in Truth’s honor. 1976– Interstate 194 is named for her in Michigan. 1979– The artwork The Dinner Party features a place setting for Truth. 1980– The Inter Cooperative Council at the University of Michigan and the residents of the then Lenny Bruce House rename it as Sojourner Truth House in her honor. 1981– Truth is inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in Seneca Falls, New York. 1981– Feminist theorist and author bell hooks titles her first major work after Truth’s “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech. 1983– Truth is in the first group of women inducted into the Michigan Women’s Hall of Fame in Lansing. 1986– The U.S. Postal Service issues a commemorative postage stamp honoring Sojourner Truth. 1987– Truth is commemorated in a monument of “Michigan Legal Milestones” erected by the State Bar of Michigan. 1997– The NASA Mars Pathfinder mission’s robotic rover is named “Sojourner” after her. 1998– S.T. Writes Home appears on the web offering “Letters to Mom from Sojourner Truth,” in which the Mars Pathfinder Rover at times echoes its namesake. 1999– A 12-foot-high monument is built to honor her in Battle Creek, Michigan. 1999– The Broadway musical The Civil War includes an abridged version of Truth’s “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech as a spoken-word segment. On the 1999 cast recording, the track was performed by Maya Angelou. 2002– Scholar Molefi Kete Asante lists Sojourner Truth on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans. 2002– A statue was installed in Florence Massachusetts to honor Sojourner Truth in a small park located on Pine Street and Park Street, on which she lived for ten years. 2004– The King’s College, located inside the Empire State Building in New York City, names one of their houses “The House of Sojourner Truth”. 2009– Truth becomes the first black woman honored with a bust in the U.S. Capitol. The bust was sculpted by noted artist Artis Lane. It is in Emancipation Hall of the Capitol Visitor Center. v2014– Truth was included in the Smithsonian Institution’s list of the "100 Most Significant Americans". 2014– Asteroid (249521) Truth is named in her honor. 2015– A statue of Sojourner Truth is unveiled at the University of California, San Diego. The statue resides in Marshall College. As of March 2015, K-12 schools in several states, including California, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York and Oregon, are named after her, as is Sojourner–Douglass College in Baltimore. Ten-dollar bill On April 20, 2016 Treasury Secretary Jacob Lew announced that several denominations of United States currency would be redesigned prior to 2020, the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment. The newly designed $10 bill will include images on the reverse which will pay homage to the women’s suffrage movement and feature the images of Truth, Lucretia Mott, Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Alice Paul, and the 1913 Woman Suffrage Procession.

Amy Clampitt (June 15, 1920– September 10, 1994) was an American poet and author. Life Amy Clampitt was born on June 15, 1920 of Quaker parents, and brought up in New Providence, Iowa. In the American Academy of Arts and Letters and at nearby Grinnell College she began a study of English literature that eventually led her to poetry. She graduated from Grinnell College, and from that time on lived mainly in New York City. To support herself, she worked as a secretary at the Oxford University Press, a reference librarian at the Audubon Society, and a freelance editor. Not until the mid-1960s, when she was in her forties, did she return to writing poetry. Her first poem was published by The New Yorker in 1978. In 1983, at the age of sixty-three, she published her first full-length collection, The Kingfisher. In the decade that followed, Clampitt published five books of poetry, including What the Light Was Like (1985), Archaic Figure (1987), and Westward (1990). Her last book, A Silence Opens, appeared in 1994. She also published a book of essays and several privately printed editions of her longer poems. She taught at the College of William and Mary, Smith College, and Amherst College, but it was her time spent in Manhattan, in a remote part of Maine, and on various trips to Europe, the former Soviet Union, Iowa, Wales, and England that most directly influenced her work. Clampitt was the recipient of a 1982 Guggenheim Fellowship, a MacArthur Fellowship (1992), and she was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the American Academy of Poets. She died of cancer in September 1994.

Dame Emilie Rose Macaulay, DBE (1 August 1881– 30 October 1958) was an English writer, most noted for her award-winning novel The Towers of Trebizond, about a small Anglo-Catholic group crossing Turkey by camel. The story is seen as a spiritual autobiography, reflecting her own changing and conflicting beliefs. Macaulay’s novels were partly-influenced by Virginia Woolf; she also wrote biographies and travelogues. Early years and education Macaulay was born in Rugby, Warwickshire the daughter of George Campbell Macaulay, a Classical scholar, and his wife, Grace Mary (née Conybeare). Her father was descended in the male-line directly from the Macaulay family of Lewis. She was educated at Oxford High School for Girls and read Modern History at Somerville College at Oxford University. Career Macaulay began writing her first novel, Abbots Verney (published 1906), after leaving Somerville and while living with her parents at Ty Isaf, near Aberystwyth, in Wales. Later novels include The Lee Shore (1912), Potterism (1920), Dangerous Ages (1921), Told by an Idiot (1923), And No Man’s Wit (1940), The World My Wilderness (1950), and The Towers of Trebizond (1956). Her non-fiction work includes They Went to Portugal, Catchwords and Claptrap, a biography of Milton, and Pleasure of Ruins. Macaulay’s fiction was influenced by Virginia Woolf and Anatole France. During World War I Macaulay worked in the British Propaganda Department, after some time as a nurse and later as a civil servant in the War Office. She pursued a romantic affair with Gerald O’Donovan, a writer and former Jesuit priest, from 1918 until his death in 1942. During the interwar period she was a sponsor of the pacifist Peace Pledge Union; however she resigned from the PPU and later recanted her pacifism in 1940. Her London flat was utterly destroyed in the Blitz, and she had to rebuild her life and library from scratch, as documented in the semi-autobiographical short story, Miss Anstruther’s Letters, which was published in 1942. The Towers of Trebizond, her final novel, is generally regarded as her masterpiece. Strongly autobiographical, it treats with wistful humour and deep sadness the attractions of mystical Christianity, and the irremediable conflict between adulterous love and the demands of the Christian faith. For this work, she received the James Tait Black Memorial Prize in 1956. Personal life Macaulay was never a simple believer in “mere Christianity”; however, and her writings reveal a more complex, mystical sense of the divine. That said, she did not return to the Anglican church until 1953; she had been an ardent secularist before and, while religious themes pervade her novels, previous to her conversion she often treats Christianity satirically, for instance in Going Abroad and The World My Wilderness. She never married, as a result of her lengthy and secret relationship with Gerald O’Donovan. They met in 1918 and the affair lasted until his death in 1942. She was created a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBE) on 31 December 1957 in the 1958 New Years Honours. Macaulay was an active feminist throughout her life. Dame Rose Macaulay died on 30 October 1958, aged 77. Memorable quotes From The Towers of Trebizond: “Adultery is a meanness and a stealing, a taking away from someone what should be theirs, a great selfishness, and surrounded and guarded by lies lest it should be found out. And out of meanness and selfishness and lying flow love and joy and peace beyond anything that can be imagined.” First line of The Towers of Trebizond, cited by librarian Nancy Pearl in “Famous First Words: A Librarian Shares Favorite Literary Opening Lines,” [1] hosted by Steve Inskeep on NPR’s Morning Edition, 8 September 2004, as an example among “some notable opening lines that have made Pearl’s heart pound”. “Take my camel, dear”, said my Aunt Dot, as she climbed down from this animal on her return from High Mass. From Staying with Relations. Discussing the coat worn by a visitor, a character remarks: “Is rabbit fur disgusting because it’s cheap, or is it cheap because it’s disgusting?”

May Sarton is the pen name of Eleanore Marie Sarton ( (May 3, 1912– July 16, 1995), an American poet, novelist and memoirist. Biography Sarton was born in Wondelgem, Belgium (today a part of the city of Ghent). Her parents were science historian George Sarton and his wife, the English artist Mabel Eleanor Elwes. When German troops invaded Belgium after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in 1914, her family fled to Ipswich, England, where Sarton’s maternal grandmother lived. One year later, they moved to Boston, Massachusetts, where her father started working at Harvard University. She went to school in Cambridge, Massachusetts, graduating from Cambridge High and Latin School in 1929. She started theatre lessons in her late teens, but continued writing poetry. She published her first collection in 1937, entitled Encounter in April. In 1945 in Santa Fe, New Mexico, she met Judy Matlack, who became her partner for the next thirteen years. They separated in 1956, when Sarton’s father died and Sarton moved to Nelson, New Hampshire. Honey in the Hive (1988) is about their relationship. In her memoir At Seventy, Sarton reflected on Judy’s importance in her life and how her Unitarian Universalist upbringing shaped her. She was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1958. Sarton later moved to York, Maine. In 1990, she suffered a stroke, severely reducing her ability to concentrate and write. After several months, she was able to dictate her final journals, starting with Endgame, with the help of a tape recorder. She died of breast cancer on July 16, 1995, and is buried in Nelson, New Hampshire. Works and themes Despite the quality of some of her many novels and poems, May Sarton’s best and most enduring work probably lies in her journals and memoirs, particularly Plant Dreaming Deep (about her early years at Nelson, ca. 1958-68), Journal of a Solitude (1972-1973, often considered her best), The House by the Sea (1974-1976), Recovering (1978-1979) and At Seventy (1982-1983). In these fragile, rambling and honest accounts of her solitary life, she deals with such issues as aging, isolation, solitude, friendship, love and relationships, lesbianism, self-doubt, success and failure, envy, gratitude for life’s simple pleasures, love of nature (particularly of flowers), the changing seasons, spirituality and, importantly, the constant struggles of a creative life. Sarton’s later journals are not of the same quality, as she endeavoured to keep writing through ill health and by dictation. Although many of her earlier works, such as Encounter in April, contain vivid erotic female imagery, May Sarton often emphasized in her journals that she didn’t see herself as a “lesbian” writer, instead wanting to touch on what is universally human about love in all its manifestations. When publishing her novel Mrs. Stevens Hears the Mermaids Singing in 1965, she feared that writing openly about lesbianism would lead to a diminution of the previously established value of her work. “The fear of homosexuality is so great that it took courage to write Mrs. Stevens Hears the Mermaids Singing,” she wrote in Journal of a Solitude, “to write a novel about a woman homosexual who is not a sex maniac, a drunkard, a drug-taker, or in any way repulsive, to portray a homosexual who is neither pitiable nor disgusting, without sentimentality ...” After the book’s release, many of Sarton’s works began to be studied in university level women’s studies classes, being embraced by feminists and lesbians alike. However, Sarton’s work should not be classified as 'lesbian literature’ alone, as her works tackle many deeply human issues of love, loneliness, aging, nature, self-doubt etc., common to both men and women. Margot Peters’ controversial biography (1998) revealed May Sarton as a complex individual who often struggled in her relationships.

Lilian Helen Bowes Lyon (1895–1949) was a British poet. Biography Born 23 December 1895 at Ridley Hall, Northumberland. She was the youngest daughter of the Honourable Francis Bowes Lyon and was a first cousin of Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon, Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother. During the First World War, Bowes Lyon helped at Glamis Castle (owned by her uncle) which became a convalescence home for soldiers. Her brother Charles Bowes Lyon was killed in the war on 23 October 1914, inspiring her poem “Battlefield” which was later published in Bright Feather Fading. After the Great War, Bowes Lyon studied for a time at the University of Oxford and then moved to London. She was independently wealthy. In 1929, she met the writer William Plomer CBE and through him, Laurens van der Post. She published two novels, The Buried Stream (1929) and Under the Spreading Tree (1931) but thereafter focused on poetry. Bowes Lyon published six individual collections with Jonathan Cape and a Collected Poems in 1948. Her “Collected Poems” contains an introduction by C. Day-Lewis, who noted the influences of Emily Dickinson, Hopkins and Christina Rossetti. Her verse appeared in many periodicals and anthologies including The Adelphi, Country Life, Kingdom Come, The Listener, The London Mercury, The Lyric (USA), The Observer, Orion, Punch, The Spectator, Time and Tide and “Poetry” (USA). During the Second World War, Bowes Lyon moved to the East End of London, where she used the Tilbury Docks unofficial air raid shelter and assisted with nursing the injured. She had several amputations due to thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s Disease), losing toes, a foot, her lower legs and eventually both her legs below her hips. She returned to her home in Kensington and continued to write poetry despite the thromboangitis obliterans beginning to affect her hands. These poems, found amongst William Plomer’s papers at University of Durham, were published in “Uncollected Poems” by Tragara Press. She died on 25 July 1949.

Agnes Ethelwyn Wetherald was born of English-Quaker parents at Rockwood, Ontario, April 26th, 1857. Her father was the late Rev. William Wetherald, who founded the Rockwood Academy about the middle of the last century, and was its principal for some years. He was a lover of good English, spoken and written, and his talented daughter has owed much to his careful teaching. He was the teacher whom the late James J. Hill, the railway magnate, had held in such grateful remembrance. Additional education was received by Miss Wetherald at the Friends' Boarding School, Union Springs, N.Y., and at Pickering College. Miss Wetherald began the writing of poetry later in life than most poets and her first book of verse, The House of the Trees and Other Poems, did not appear until 1895. This book at once gave her high rank among women poets. Prior to this, she had collaborated with G. Mercer Adam on writing and publishing a novel, An Algonquin Maiden, and had conducted the Woman's Department in The Globe, Toronto, under the nom de plume, 'Bel Thistlewaite.' In 1902, appeared her second volume of verse, Tangled in Stars, and, in 1904, her third volume, The Radiant Road. In the autumn of 1907, a collection of Miss Wetherald's best poems was issued, entitled, The Last Robin: Lyrics and Sonnets. It was warmly welcomed generally, by reviewers and lovers of poetry. The many exquisite gems therein so appealed to Earl Grey, the then Governor-General of Canada, that he wrote a personal letter of appreciation to the author, and purchased twenty-five copies of the first edition for distribution among his friends. For years Miss Wetherald has resided on the homestead farm, near the village of Fenwick, in Pelham Township, Weland county, Ontario, and there in the midst of a large orchard and other rural charms, has dreamed, and visioned, and sung, pouring out her soul in rare, sweet songs, with the naturalness of a bird. And like a bird she has a nest in a large willow tree, cunningly contrived by a nature-loving brother, where her muse broods contentedly, intertwining her spirit with every aspect of the beautiful environment.

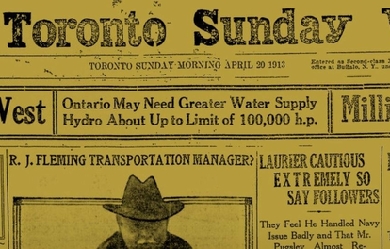

Florence Randall Livesay, daughter of Stephen and Mary Louisa Randal, was born at Compton, P. Q., and educated at Compton Ladies' College, now King's Hall. She taught for one year in a private school in New York, and subsequently for seven years was a member of the staff of the Evening Journal, Ottawa,–editor of the Woman's Page. In 1902, the Hon. Joseph Chamberlain requested Canada to send some teachers to the Boer Concentration Camps and Miss Randal, offering her services, was one of the forty chosen. She remained for one year and then returned to Canada, locating at Winnipeg. She joined the staff of the Winnipeg Telegram, and three years later that of the Manitoba Free Press. For several years she edited the Children's Department of the latter, but now writes as a 'free lance.' In 1908, she married Mr. J. Fred. B. Livesay of Winnipeg, Manager and Secretary of the Western Associated Press, Limited, and is now the mother of two girls. Of recent years, Mrs. Livesay has contributed poems, short stories and articles to Canadian and American magazines and journals, and a volume of her verse, entitled Songs of Ukraina is now being published by J. M. Dent & Sons. Mrs. Livesay's folk songs translated from the Ruthenian are unusual and notable, but her poetical gift is quite as discernible in her other poems. She has the imagination and the practiced touch of the artist., daughter of Stephen and Mary Louisa Randal, was born at Compton, P. Q., and educated at Compton Ladies' College, now King's Hall. She taught for one year in a private school in New York, and subsequently for seven years was a member of the staff of the Evening Journal, Ottawa,–editor of the Woman's Page. In 1902, the Hon. Joseph Chamberlain requested Canada to send some teachers to the Boer Concentration Camps and Miss Randal, offering her services, was one of the forty chosen. She remained for one year and then returned to Canada, locating at Winnipeg. She joined the staff of the Winnipeg Telegram, and three years later that of the Manitoba Free Press. For several years she edited the Children's Department of the latter, but now writes as a 'free lance.' In 1908, she married Mr. J. Fred. B. Livesay of Winnipeg, Manager and Secretary of the Western Associated Press, Limited, and is now the mother of two girls. Of recent years, Mrs. Livesay has contributed poems, short stories and articles to Canadian and American magazines and journals, and a volume of her verse, entitled Songs of Ukraina is now being published by J. M. Dent & Sons. Mrs. Livesay's folk songs translated from the Ruthenian are unusual and notable, but her poetical gift is quite as discernible in her other poems. She has the imagination and the practiced touch of the artist.

In a very real sense Miss Laura Elizabeth McCully is a Toronto writer, as, with the exception of one academic year in the United States and a few months in Ottawa, she has lived all her life in this city. She is a grand niece of the late Hon. John McCully, of Truro, Nova Scotia, one of the Fathers of Confederation; and is the daughter of Samuel Edward McCully, M.D., and Helen (Fitzgibbon) McCully. Her father is of Manx descent, and her mother is a descendant of the late James McBride of Halton county, Ontario, magistrate, who was one of the pioneers of this province, and who heroically cleared off forest and left to his heirs, one thousand acres of valuable farm lands. Miss McCully's poetry is enriched by classical illustrations, and expressed in forceful and melodious language. Her imagination relates us to the universe and to humanity. Wordsworth found new lessons in the fields and woods, and taught them; Lanier made trees, flowers and clouds our intimate friends; when we read Miss McCully's nature poems we are not conscious of the moralizing of the poet, we are in the glens ourselves looking at the afterglow, with the purity, the glory, the growth spirit and the transforming beauty of nature flowing into our lives. In a few flaming lines her stories reveal the love, the despair, and the ultimately triumphant faith of humanity. With tender pathos she unveils the evils of social and industrial conditions, and in clear tones arouses each soul, and makes it conscious of the splendour of the better conditions ahead, and thrills it with the determination to achieve for justice, freedom, and truth. – JAMES L. HUGHES, LL. D.

Cicely Mary Hamilton (née Hammill, 15 June 1872– 6 December 1952), was an English actress, writer, journalist, suffragist and feminist, part of the struggle for women’s suffrage in the United Kingdom. She is now best known for the play How the Vote was Won, which sees all of England’s female workers returning to their nearest male relative for financial support.. She is also credited as author of one of the most frequently performed suffrage plays, A Pageant of Great Women (1909), which first put Jane Austen on the stage as one of its “Learned Women.” Biography Cicely Mary Hammill was born in Paddington, London and educated in Malvern, Worcestershire. After a short spell in teaching she acted in a touring company. Then she wrote drama, including feminist themes, and enjoyed a period of success in the commercial theatre. In 1908 she and Bessie Hatton founded the Women Writers’ Suffrage League. This grew to around 400 members, including Ivy Compton-Burnett, Sarah Grand, Violet Hunt, Marie Belloc Lowndes, Alice Meynell, Olive Schreiner, Evelyn Sharp, May Sinclair and Margaret L. Woods. It produced campaigning literature, written by Sinclair amongst others, and recruited many prominent male supporters. Hamilton supplied the lyrics of “The March of the Women”, the song which Ethel Smyth composed in 1910 for the Women’s Social and Political Union. In the days before radio, one effective way to get a message out into society and to have it discussed was to produce short plays that could be performed around the country, and so suffrage drama was born. Elizabeth Robins’s Votes for Women and Cicely Hamilton and Christopher St. John’s How the Vote Was Won are two predominant examples of the genre. Hamilton also wrote A Pageant of Great Women, a highly successful women’s suffrage play based on the ideas of her friend, the theatre director Edith Craig. Hamilton played Woman while Craig played the painter Rosa Bonheur, one of the 50 or so great women in the play. It was produced all over the UK from 1909 until the First World War. Hamilton was a member of Craig’s theatre society, the Pioneer Players. Her play Jack and Jill and a Friend was one of the three plays in the Pioneer Players’ first production in May 1911. During World War I Hamilton initially worked in the organisation of nursing care, and then joined the army as an auxiliary. Later she formed a repertory company to entertain the troops. After the war, she wrote as a freelance journalist, particularly on birth control, and as a playwright for the Birmingham Repertory Company. In 1938 she was given a Civil List pension. Hamilton’s Theodore Savage (1922, vt. Lest Ye Die 1928) is a science-fiction novel about a Britain devastated by a war. In July 2017, the Finborough Theatre staged the first London production of Hamilton’s play 'Just to Get Married’ in over 100 years. It received positive reviews (4 stars) from The Times The Observer The Evening Standard and The New York Times The production was directed by Melissa Dunne and the cast included Tania Amsel, Nicola Blackman, Joanne Ferguson, Lauren Fitzpatrick, Jonny McPherson, Stuart Nunn, Philippa Quinn, Simon Rhodes and Joshua Riley.

Paula Gunn Allen (October 24, 1939 – May 29, 2008) was a Native American poet, literary critic, activist, professor, and novelist. Of mixed-race European-American, Native American, and Arab-American descent, she identified with her mother's people, the Laguna Pueblo and childhood years. She drew from its oral traditions for her fiction poetry and also wrote numerous essays on its themes. She edited four collections of Native American traditional stories and contemporary works and wrote two biographies of Native American women.