Info

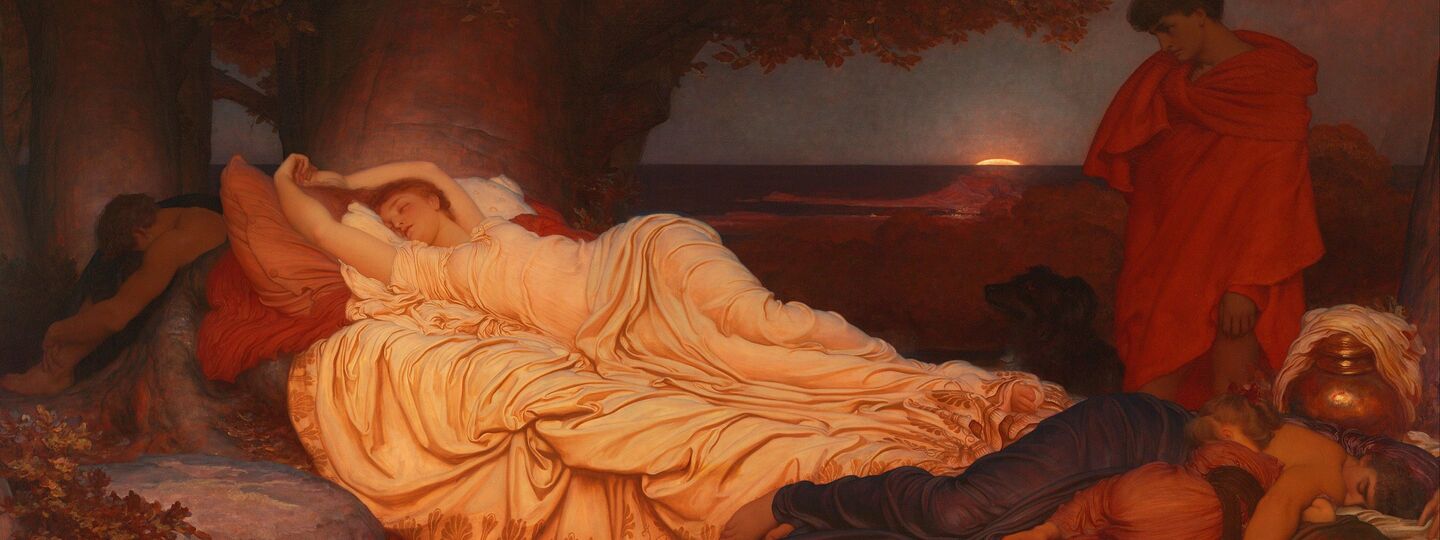

Cimon et Iphigénie

Edmund Leighton

1884

Art Gallery of New South Wales

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron FRS; 22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824), simply known as Lord Byron, was an English poet and peer. One of the leading figures of the Romantic movement, Byron is regarded as one of the greatest English poets. He remains widely read and influential. Among his best-known works are the lengthy narrative poems Don Juan and Childe Harold's Pilgrimage; many of his shorter lyrics in Hebrew Melodies also became popular. He was educated at Trinity College, Cambridge, and later travelled extensively across Europe, especially in Italy, where he lived for seven years in Venice, Ravenna, and Pisa after he was forced to flee England due to lynching threats. During his stay in Italy, he frequently visited his friend and fellow poet Percy Bysshe Shelley. Later in life Byron joined the Greek War of Independence fighting the Ottoman Empire and died leading a campaign during that war, for which Greeks revere him as a folk hero. He died in 1824 at the age of 36 from a fever contracted after the First and Second Sieges of Missolonghi.

.jpg?locale=fr)

Andrés de Jesús María y José Bello López (Caracas, 29 de noviembre de 1781 - Santiago, 15 de octubre de 1865) fue un filósofo, poeta, traductor, filólogo, ensayista, educador, político y jurista venezolano de la época pre-republicana de la Capitanía General de Venezuela. Considerado como uno de los humanistas más importantes de América, contribuyó en innumerables campos del conocimiento. De una profunda educación autodidacta, nació en la ciudad de Caracas, en la entonces Capitanía General de Venezuela, donde vivió hasta 1810. Fue maestro del Libertador Simón Bolívar y participó en el proceso que llevaría a la independencia de Venezuela. Como parte del bando revolucionario, integró la primera misión diplomática a Londres conjuntamente con Luis López Méndez y Simón Bolívar, lugar donde residiría por casi veinte años. En 1829 embarca junto a su familia hacia Chile, donde es contratado por su gobierno, desarrollando grandes obras en el campo del derecho y las humanidades. Como reconocimiento a su mérito humanístico, el Congreso Nacional de Chile le otorgó la nacionalidad por gracia en 1832. En Santiago alcanzaría a desempeñar cargos como senador y profesor, además de dirigir diversos periódicos del lugar. En su desempeño como legislador sería el principal impulsor y redactor del Código Civil, una de las obras jurídicas americanas más novedosas e influyentes de su época. Bajo su inspiración y con su decisivo apoyo, en 1842 se crea la Universidad de Chile, institución de la que se convertirá en su primer rector por más de dos décadas. Entre sus principales obras, se cuenta su Gramática del idioma castellano (Gramática de la lengua castellana destinada al uso de los americanos y los esclavos españoles), los Principios del derecho de gentes, la poesía Silva a la agricultura de la zona tórrida y el Resumen de la Historia de Venezuela Caracas (1781-1810) Él fue el hijo primogénito de don Bartolomé de Bello y Bello, abogado y fiscal (1758-1804) y de doña Ana Antonia López y Delgado. En su Caracas natal, el joven Andrés cursó las primeras letras en la academia de Ramón Vanlonsten. Leyó los clásicos del siglo de oro, y desde muy joven frecuentaba el Convento de Las Mercedes, donde aprende latín de manos del padre Cristóbal de Quesada. A la muerte de éste (1796) Bello traduce el libro V de la Eneida. En 1797 comienza estudios en la Real y Pontificia Universidad de Caracas, graduándose de Bachiller en Artes el 14 de junio de 1800. Ese mismo año, antes de graduarse, recibe en Caracas al naturalista alemán Alexander von Humboldt y a su compañero, Aimé Bonpland, y los acompaña a subir y explorar el Cerro Ávila. En su ciudad natal realiza también estudios inacabados de derecho y medicina, aprende por su propia cuenta inglés y francés, y da clases particulares, contándose el joven Simón Bolívar entre sus alumnos. Sus traducciones y adaptaciones de textos clásicos le proporcionan prestigio, y en 1802 gana por concurso el rango de Oficial Segundo de Secretaría del gobierno colonial. Durante el período entre 1802 y 1810 Bello se convierte en una de las personas intelectualmente más influyentes en la sociedad de Caracas, destacándose al desempeñar labores políticas para la administración colonial, además de ganar notoriedad como poeta, al traducir la tragedia de Voltaire, Zulima. Al llegar la primera imprenta a Caracas en 1808, la gran notoriedad de Bello lo hace el candidato ideal para asumir la dirección de la recién creada Gaceta de Caracas, una de las primeras publicaciones venezolanas. Los sucesos revolucionarios del 19 de abril de 1810 dan inicio a la independencia de Venezuela. En ellos participa el joven Bello, y la Junta enseguida lo nombra Oficial Primero de la Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores. El 10 de junio de ese año, zarpa de las costas de su patria para ejecutar una delicada misión diplomática como representante de la naciente República: es comisionado junto con Simón Bolívar y Luis López Méndez para lograr el apoyo británico a la causa de la independencia. Bello es escogido por sus amplios conocimientos y su dominio de la lengua inglesa, que había adquirido de forma autodidacta. Sale destino a Londres en la corbeta Wellington, que puso a disposición de la Junta Suprema de Caracas el almirante Thomas Cochrane. Londres (1810-1829) La corbeta en la cual viajaba la comisión llegó al puerto de Portsmouth el 10 de julio de 1810, lugar desde el que se dirigieron hacia Londres con el fin de establecer contactos con miembros de las altas esferas británicas. La misión encomendada a Bello, Bolívar y López encuentra graves problemas para desarrollar su labor, puesto que la situación política había cambiado el eje de los intereses ingleses respecto de América. Por un lado, la invasión napoleónica a España había acercado al Reino Unido con su tradicional enemigo, frente al peligro común que consistía Napoleón Bonaparte. Esto significó para el gobierno de Londres tener que ayudar a la causa hispana, otorgándole créditos y ayuda a la Junta Suprema Central que gobernaba en nombre del "cautivo" Fernando VII. Sin perjuicio de aquello, y utilizando un doble discurso, Londres toleraba la propaganda independentista americana en su territorio, en especial la realizada por el también venezolano Francisco de Miranda, al mismo tiempo que le otorgaba a los americanos la calificación de beligerantes. Los intereses británicos con la independencia de las colonias españolas de América no iban más allá. Con esos antecedentes, la delegación venezolana fue recibida por el canciller británico Richard Wellesley, hermano del duque de Wellington, en cinco entrevistas no oficiales realizadas en su domicilio particular. La postura británica fue clara y desde el principio dieron a entender que en esos momentos, el apoyo político a la causa de la independencia era imposible y trataron de desviar las negociaciones hacia acuerdos comerciales más acordes con los intereses británicos, en un intento además de presionar a España para que les dejase comerciar libremente con sus colonias. Otra de las razones para permitir el recibimiento informal de la embajada venezolana, era el de evitar que los mismos tuvieran que recurrir a la ayuda francesa, pese al escaso interés mostrado por Bonaparte por la región. El fracaso de la misión provoca el regreso de Bolívar al Nuevo Mundo, con el fin de sumarse a la guerra que arreciaba entonces en el continente. Bello y López quedan entonces a cargo de la embajada, empezando a vivir diversas penurias económicas ante el cada vez más escaso aporte realizado por el gobierno de la naciente república. En esta época Bello empieza a desenvolverse dentro de la sociedad londinense, trabando una breve pero influyente amistad durante el escaso tiempo que confluyeron en dicha ciudad con Francisco de Miranda. Pese a conocerse desde la época en que ambos residían en Caracas, Miranda, en su rol de líder de la causa independentista americana en Europa, aprovechó los amplios conocimientos de Bello para sumar a distintos actores a la causa. Miranda en aquella época residía bajo el amparo británico en Londres, con el fin de escapar de la constante persecución española, quien lo había convertido en uno de sus principales enemigos. Bolívar, López y Bello fueron recibidos por Miranda en su casa de Grafton Street, a donde concurrieron reiteradamente con el fin de acceder a las esferas de influencia que Miranda había desarrollado. Después de la partida de Bolívar, Bello es acogido por un tiempo en casa de Miranda, en donde es iniciado en la masonería, en una nueva logia llamada Nº 7 de Caballeros Racionales, de la cual fueron sus fundadores Carlos de Alvear, José de San Martín y Matías Zapiola, mientras que López Méndez ejercía de venerable y Bello de secretario. Otro de los personajes que ejercería una amplia influencia sería su amigo José María Blanco White, protegido de Lord Holland. Sería este último bajo instancias de Blanco, quien le proporcionaría cierta estabilidad a Bello al contratarlo como su bibliotecario y profesor particular. Junto con éste se desempeña en el periódico El Español, que no abogaba por una independencia total de España. En tal medio se desempeñó como redactor, y en su calidad de tal tomó contacto con personajes como Francisco Antonio Pinto, futuro presidente de Chile, Antonio José de Irisarri, encargado de negocios de Chile y quien impulsaría su viaje a Santiago, Servando Teresa de Mier, con quien colaboraría en El Español, James Mill, economista y político escocés y padre de John Stuart Mill, Jeremy Bentham, filósofo inglés, padre del utilitarismo, Vicente Salvá, filólogo español, Bartolomé José Gallardo y Antonio Puigblanch, entre otros. Pese a la ayuda recibida por Blanco White, la situación económica de Bello se hace cada vez más precaria. En 1812 manifiesta su intención de regresar a Venezuela, pese a lo cual un gran terremoto que asola Caracas el 26 de marzo de 1812 no permite que su familia pueda ayudarlo, dada la pérdida de buena parte del patrimonio familiar. Para agravar más la situación, la derrota patriota y la caída de la Primera República, significa el fin de todo apoyo económico desde América y el encarcelamiento de su amigo Francisco de Miranda. Ante tales descalabros, Andrés Bello presenta una solicitud de amnistía que tentativamente habían anunciado el gobierno español ante el fracaso momentáneo de la independencia americana. Tal solicitud aparece presentada en la embajada española en Londres, fechada el 31 de junio de 1813, un curioso error en un eficiente y minucioso funcionario público. En una parte de aquella petición Bello expresa: El suplicante puede alegar también en su favor la notoria moderación de sus opiniones y conducta, que aun llegaron a hacerle mirar como desafecto de la causa de la Revolución; y cita en su abono el testimonio de cuantas personas le hayan conocido en Caracas, de las cuales no será difícil se encuentren muchas en Cádiz La petición de Bello no tuvo ningún resultado. Al año siguiente traba relación por medio de El Español con el sacerdote Servando Teresa de Mier, destacado revolucionario mexicano quien publicaría varios textos en defensa de la causa americana. Además se relaciona con Francisco Antonio Pinto, quien en esos momentos se desempeñaba como agregado comercial en la capital británica. Éste le da a conocer a Bello que los patriotas chilenos se han inspirado en el poema épico de La Araucana de Alonso de Ercilla para su causa. Pinto, quien anteriormente se desempeñaba como agente comercial, había sido comisionado por el gobierno de Chile como su agente, primero en Buenos Aires y después en Londres. En este lugar se enfrenta al igual que Bello con la caída del gobierno patriota tras la derrota de Rancagua, que lo sume en una gran pobreza. Pese a encontrarse en una situación similar, Bello ayuda en todo lo posible junto a Manuel de Sarratea al infortunado diplomático. Así traban los dos una profunda amistad, siendo Pinto uno de los escasos miembros de su círculo cercano. De regreso a Chile, Pinto tomaría parte en las victorias patriotas en Chacabuco y Maipú, formado parte de la cúpula política del país. En 1827, ante la renuncia del capitán general Ramón Freire a la primera magistratura, Pinto es elegido como Presidente de Chile. Durante su breve ejercicio del cargo, en vísperas de la guerra civil y la derrota liberal en Lircay, en uno de sus últimos decretos nombra a Bello como oficial segundo del Ministerio de Hacienda de Chile. Sus penurias económicas no menguan con su matrimonio con la joven inglesa de 20 años Mary Ann Boyland, con la que se casa en mayo de 1814. De esta unión nacerían sus primeros tres hijos Carlos (1815), Francisco (1817) y Juan Pablo Antonio (1820). Su vida familiar se ve constantemente afectada por la falta de sustento, los cuales intenta mejorar solicitando un empleo al gobierno de Cundinamarca en 1815, y al de las Provincias Unidas del Río de la Plata al año siguiente. En este último caso, el trabajo fue concedido a Bello, pero por razones poco claras nunca lo asumió en propiedad. Sus situación alcanza en 1816 a mejorar un poco al recibir alguna ayuda por parte del gobierno británico, con lo que puede realizar algunas investigaciones en la biblioteca del Museo Británico. En este lugar se encuentra trabajando, cuando Thomas Bruce, conde de Elgin, presenta los mármoles del Partenón, en 1819. Al año siguiente colabora con James Mill en la transcripción en limpio de los manuscritos de Jeremy Bentham. Su esposa se ve afectada por la tuberculosis, enfermedad de la que fallece el 9 de mayo de 1821, seguida por su hijo Juan Pablo en diciembre de aquel año, siendo el primero de nueve de sus hijos que viera morir en vida. En esta época trabaría también amistad con el granadino Juan García del Río, y más importante aún para su futuro, conoce en 1819 a Antonio José de Irisarri, quien se había desempeñado como director supremo interino de Chile en 1814, y después de la independencia de Chile como canciller de la nueva República. Ese mismo año escribe a Irisarri solicitándole explícitamente ayuda, con el fin de ser contratado en la legación chilena en Londres. La respuesta positiva se demora, pese a los intentos del embajador en acelerarlos. Tal designación demora más de seis meses, logrando Bello finalmente ser designado para un empleo estable, como secretario de la legación en junio de 1822. Durante su desempeño como secretario, Bello sigue las instrucciones de Irisarri, a quién se le encomienda lograr el reconocimiento de Chile por Francia y el Reino Unido, además de conseguir un empréstito para la naciente república. El encargado Irisarri responde a órdenes directas del director supremo Bernardo O'Higgins, quien se desempeña en el mando hasta su forzada abdicación el 28 de enero de 1823. Irisarri se ve entonces interpelado por un nuevo delegado del gobierno, Mariano Egaña, quien mantenía una antigua disputa con Irisarri. Bello se ve envuelto en medio de un desagradable conflicto, en el cual se enfrenta con el titular del cargo y su superior directo (Egaña), al mismo tiempo que debe un gran aprecio a su antiguo jefe (Irisarri). Sin embargo, las suspicacias y temores iniciales de Egaña se disipan en el tiempo, al descubrir en Bello una mente brillante. No escatima entonces elogios para hablar de quien se convertiría en uno de sus grandes amigos, haciendo presente en una recomendación enviada en 1826, cuando Bello ya no se desempeñaba en la legación, con el fin de favorecer su contratación por parte del gobierno de Chile. Dice Mariano Egaña en su informe: La feliz circunstancia de que existan en Santiago mismo personas que han tratado a Bello en Europa, me releva en gran parte de la necesidad de hacer el elogio de este literato: básteme decir que no se presentaría fácilmente una persona tan a propósito para llenar aquella plaza. Educación escogida y clásica, profundos conocimientos en literatura, posesión completa de lenguas principales, antiguas y modernas, práctica en la diplomacia, y un buen carácter, a que da bastante realce la modestia, le constituyen, no sólo de desempeñar muy satisfactoriamente el cargo de oficial mayor, si no que su mérito justificaría la preferencia que le diese el gobierno respecto de otros que solicitasen igual destino Durante esta época Bello realiza buena parte de su trabajo como escritor y poeta, dirigiendo y redactando en gran medida el El Censor Americano (1820), La Biblioteca Americana (1823) y siendo el director de El Repertorio Americano (1826). Todas estas obras constituyen por muchos la más grande manifestación europea del pensamiento americano, en la cual se publican diversas y variadas obras sobre ciencias eruditas, filología, estudios de críticas y análisis. En ellas se publican dos de los grandes poemas de Bello, la Alocución a la poesía de 1823, y la Agricultura en la zona tórrida de 1826. Se desempeña en la legación chilena hasta 1825, cuando termina su contrato. En ese mismo año pasa a desempeñar labores iguales en la embajada de la Gran Colombia, en las cuales sufre una gran decepción al no ser designado titular del cargo que ha quedado vacante por parte de Bolívar. En su intercambio epistolar Bello manifiesta su decepción por lo sucedido, manifestando su deseo de abandonar de manera definitiva Europa. En 1828, y ante reiteradas solicitudes de Egaña, el gobierno de Chile contrata a Bello para un puesto en el Ministerio de Hacienda, abandonado definitivamente el Reino Unido el 14 de febrero de 1829. Santiago (1829-1865) Andrés Bello llega a Chile en 1829, junto con su esposa Isabel Dunn, con quien había contraído matrimonio el 24 de febrero de 1824. Su designación titular es de Oficial Mayor del Ministerio de Hacienda, Académico del Instituto Nacional, y fue el fundador del Colegio de Santiago, rival del Liceo de Chile creado por José Joaquín de Mora. Tuvo una importante participación en la actividad literaria y cultural en el llamado Movimiento Literario de 1842. En ese mismo año con la fundación de la nueva Universidad de Chile se le otorga el título de primer rector. Participa en la edición del diario El Araucano entre 1840 a 1860, siendo el medio cultural de referencia casi obligatoria en aquella época. Participa en el debate y polémica sobre el carácter de la educación pública junto con Domingo Faustino Sarmiento. En estos años, durante su estadía en Chile, publíca sus principales obras sobre gramática y derecho, recibiendo distintos reconocimientos por tal labor, siendo el más importante el recibido en 1851 al ser nombrado miembro honorario de la Real Academia Española. El Congreso Nacional le otorgó unánimemente la nacionalidad chilena por gracia el 17 de octubre de 1832. Sin embargo, este acuerdo no fue publicado en el diario oficial de la época, El Araucano. Posteriormente, en la edición del 7 de diciembre de 1832 de ese periódico se publicó un “aviso oficial” que señaló: “Se han dado cartas de naturaleza á favor de don Benito Fernandez Maqueira, de don Carlos Eduardo Mitchall, de don Victorino Garrido, de don Andres Bello y de don Tomas Ovejero”. En consecuencia, Andrés Bello no recibió la nacionalidad por gracia sino que él la solicitó conforme al reglamento sobre la materia publicado el 9 de noviembre de 1832, tal como cualquier otro extranjero. Andrés Bello se desempeñó como senador por la ciudad de Santiago entre los años 1837 y 1864. Fue el principal y casi exclusivo redactor del Código Civil chileno entre 1840 a 1855, considerado una de las obras más originales de la legislación americana. Entre su obra literaria, destaca su traducción libre de la "Oración por todos" de Víctor Hugo, considerada por muchos la mejor poesía chilena del siglo XIX. Impulsor de la Universidad de Chile, fue designado su primer rector, desempeñando el cargo hasta su muerte. Falleció en la ciudad de Santiago, el día 15 de octubre de 1865 y fue enterrado en el Cementerio General de dicha ciudad. Reconocimientos * Cenotafio en honor a Andrés Bello en el Panteón Nacional de Caracas, Venezuela. * En 1832, el congreso chileno le otorga la nacionalidad de ese país por gracia. * En 1883, una ciudad colombiana adoptó su apellido (la ciudad de Bello, en Antioquia); por solicitud de sus pobladores, quienes consideraban el nombre de Bello “Más culto, más propio y más digno del gran patriarca de las letras americanas”. * En 1927, Chile instituyó el Día del Libro, a celebrarse en el aniversario de su nacimiento. * En 1953 se fundó en Caracas la Universidad Católica Andrés Bello, una de las instituciones privadas más importantes de Venezuela. * El 15 de octubre de 1965, el Congreso venezolano crea la condecoración de la Orden Andrés Bello, con la que se premia a personajes destacados en el ámbito de la educación, la investigación científica, las letras y las artes. * En 1970 entra en vigor el Convenio Andrés Bello, organización internacional para la integración educativa, artística y científica entre los países de Iberoamérica. * El 29 de noviembre de 1981, en el bicentenario de su nacimiento, se inaugura un cenotafio en su honor en el Panteón Nacional de Caracas, por ser uno de los intelectuales caraqueños más destacados y por sus esfuerzos como diplomático a la causa de la independencia de Venezuela. * En 1988, una universidad privada de Chile adopta su nombre, la actual Universidad Nacional Andrés Bello. * Asimismo entre 1959 y 1999, una radio también acuñaba su nombre, aunque hoy es sustituida por FM2, de Iberoamericana Radio Chile. * A finales del siglo XX, se le representaba primero en el billete de 50 y luego en el de 2000 bolívares de Venezuela y en los billetes de 20.000 pesos de Chile. Obras * Obras completas de don Andrés Bello, Santiago de Chile: tomos I-XIII, Imp. de Pedro G. Ramírez, 1881-1890; tomos XIV-XV, Imprenta Cervantes, 1891-1893; (1881-1893), 15 vols. Los volúmenes III y V a XI llevan introducciones de Miguel Luis Amunátegui; los volúmenes del XII al XV de Miguel Luis Amunátegui Reyes. * I. Filosofía del entendimiento. Lógica. * II. Poema del Cid. * III. Poesías. * IV. Gramática de la lengua castellana * V. Opúsculos gramaticales. * VI-VIII. Opúsculos literarios y críticos. * IX. Opúsculos jurídicos. * X. Derecho internacional. * XI. Proyecto de código civil. * XII. Proyecto de código civil (1853) * XIII. Proyecto inédito de código civil. * XIV. Opúsculos científicos. * XV. Miscelánea * Obras completas, Caracas: Fundación La Casa de Bello, 1981-1986, 26 vols. Poemas * El romance a un samán, (Caracas) * A un Artista, (Caracas) * Oda al Anauco, 1800. * Oda a la vacuna, 1804. * Tirsis habitador del Tajo umbrío (1805) * Los sonetos a la victoria de Bailén (1808) * A la nave (imitación de Horacio) (1808) * Alocución a la Poesía, Londres, 1823. * Silva a la Agricultura de la Zona Tórrida, Londres, 1826. * El incendio de la Compañía (canto elegíaco), Santiago de Chile, Imprenta del Estado, 1841. Obra jurídica * Principios de derecho de gentes, Santiago de Chile, Imprenta de La Opinión, 1832; tuvo una segunda ed. corregida y aumentada, destinada al uso de los americanos, con el título Principios de Derecho Internacional, Valparaíso, Imprenta de El Mercurio, 1844. * Compendio (Santiago de Chile, 1850). * Proyecto de Código Civil Santiago de Chile, Imprenta Chilena, 1853, 4 vols. * Código Civil de la República de Chile. Santiago de Chile, Imprenta Nacional, 1856. * Código Civil Colombiano. Bogotá, 1887. 6 * Crítica literaria[editar] * Opúsculos literarios y críticos, publicados en diversos periódicos desde el año 1834 hasta 1849, Santiago de Chile: B.I.M. Editores, 1850. * Compendio de la historia de la literatura; por don Andrés Bello redactado para la enseñanza del Instituto Nacional, Santiago de Chile, Imprenta Chilena, 1850. * Historia de la literatura antigua * Arte de escribir con propiedad, compuesto por el Abate Condillac, traducido del francés y arreglado a la lengua castellana, Caracas, Tomás Antero, 1824. * El Otro Bello * Crítica a Homero * Crítica a Ovidio * Crítica a Horacio. Filosofía * La sociología de lo bello * Filosofía del entendimiento, manuscrito. Hay ediciones modernas: Filosofía del entendimiento y otros escritos filosóficos, prólogo de Juan David García Bacca y Filosofía del entendimiento, (introducción de José Gaos), México: FCE, 1948. *También en el tomo I de Obras completas de don Andrés Bello, Santiago de Chile, Imp. de Pedro G. Ramírez, 1881. * Filosofía Moral (Psicología mental y ética). * Lójica. Teatro * Venezuela Consolada (1805), drama. Historia y Geografía * Cosmografía o descripción del universo conforme a los últimos descubrimientos, Santiago de Chile, Imprenta de La Opinión, 1848. * Resumen de la Historia de Venezuela (Caracas, 1810) * Tratado de Cartología Métrica. * Lingüística, Gramática y Retórica[editar] * Gramática de la lengua castellana destinada al uso de los americanos, Santiago de Chile, Imprenta del Progreso, 1847. * Gramática de la lengua latina, Santiago de Chile, Imprenta de La Opinión, 1838. * Análisis ideológica de los tiempos de la conjugación castellana, Valparaíso, Imprenta de M. Rivadeneyra, 1841. * Principios de la ortología y métrica de la lengua castellana, Santiago de Chile, Imprenta de La Opinión, 1835. * Estudio sobre el Poema del Cid (1816) * Estudio sobre la Crónica de Turpín (1816) * Esbozo de la Gramática Castellana * Estudio de la raíz de todas las ciencias relativas al lenguaje. Traducciones * Mateo Boyardo, Orlando Enamorado, 1862. * Víctor Hugo, Oración por todos, 1843. * Alejandro Dumas, Teresa; drama en prosa y en cinco actos, por Alejandro Dumas, traducido al castellano y arreglado por don Andrés Bello; representado por primera vez en Santiago, en noviembre de 1839, Santiago de Chile, Imprenta del Siglo (Galería Dramática Chilena; Colección de Piezas Originales y Traducidas en el País), 1846. * Arte de escribir con propiedad, compuesto por el Abate Condillac, traducido del francés y arreglado a la lengua castellana, Caracas, Tomás Antero, 1824. Varios * Mis deseos, (Caracas) * Venezuela consolada y España restaurada, (Caracas) * Calendario manual y guía universal de forasteros en Venezuela para el año de 1810, con superior permiso, Caracas, Imprenta de Gallagher y Lamb, 1810; hay ed. facsimilar en Pedro Grases, El primer libro impreso en Venezuela, Caracas, Ediciones del Ministerio de Educación, Dirección de Cultura y Bellas Artes, 1952. * Discurso de inauguración de D. Andrés Bello, rector, Santiago de Chile, Imprenta del Estado, 1842 [sic: 1843]. Referencias Wikipedia - https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrés_Bello

.jpeg?locale=fr)

William Butler Yeats (13 June 1865 – 28 January 1939) was an Irish poet and one of the foremost figures of 20th-century literature. A pillar of the Irish literary establishment, he helped to found the Abbey Theatre, and in his later years served as a Senator of the Irish Free State for two terms. He was a driving force behind the Irish Literary Revival along with Lady Gregory, Edward Martyn and others. Yeats was born in Sandymount, Ireland and educated there and in London. He spent childhood holidays in County Sligo and studied poetry from an early age when he became fascinated by Irish legends and the occult. These topics feature in the first phase of his work, which lasted roughly until the turn of the 20th century. His earliest volume of verse was published in 1889, and its slow-paced and lyrical poems display debts to Edmund Spenser, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and the poets of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. From 1900, his poetry grew more physical and realistic. He largely renounced the transcendental beliefs of his youth, though he remained preoccupied with physical and spiritual masks, as well as with cyclical theories of life. In 1923, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. Biography Early years William Butler Yeats was born at Sandymount in County Dublin, Ireland. His father, John Butler Yeats (1839–1922), was a descendant of Jervis Yeats, a Williamite soldier, linen merchant, and well-known painter who died in 1712. Benjamin Yeats, Jervis’s grandson and William’s great-great-grandfather, had in 1773 married Mary Butler of a landed family in County Kildare. Following their marriage, they kept the name Butler. Mary was of the Butler of Neigham (pronounced Nyam) Gowran family, descended from an illegitimate brother of the 8th Earl of Ormond.By his marriage, William’s father John Yeats was studying law but abandoned his studies to study art at Heatherley School of Fine Art in London. His mother, Susan Mary Pollexfen, came from a wealthy merchant family in Sligo, who owned a milling and shipping business. Soon after William’s birth the family relocated to the Pollexfen home at Merville, Sligo to stay with her extended family, and the young poet came to think of the area as his childhood and spiritual home. Its landscape became, over time, both literally and symbolically, his “country of the heart”. So also did its location on the sea; John Yeats stated that “by marriage with a Pollexfen, we have given a tongue to the sea cliffs”. The Butler Yeats family were highly artistic; his brother Jack became an esteemed painter, while his sisters Elizabeth and Susan Mary—known to family and friends as Lollie and Lily—became involved in the Arts and Crafts movement.Yeats was raised a member of the Protestant Ascendancy, which was at the time undergoing a crisis of identity. While his family was broadly supportive of the changes Ireland was experiencing, the nationalist revival of the late 19th century directly disadvantaged his heritage, and informed his outlook for the remainder of his life. In 1997, his biographer R. F. Foster observed that Napoleon’s dictum that to understand the man you have to know what was happening in the world when he was twenty “is manifestly true of W.B.Y.” Yeats’s childhood and young adulthood were shadowed by the power-shift away from the minority Protestant Ascendancy. The 1880s saw the rise of Charles Stewart Parnell and the home rule movement; the 1890s saw the momentum of nationalism, while the Catholics became prominent around the turn of the century. These developments had a profound effect on his poetry, and his subsequent explorations of Irish identity had a significant influence on the creation of his country’s biography.In 1867, the family moved to England to aid their father, John, to further his career as an artist. At first the Yeats children were educated at home. Their mother entertained them with stories and Irish folktales. John provided an erratic education in geography and chemistry, and took William on natural history explorations of the nearby Slough countryside. On 26 January 1877, the young poet entered the Godolphin school, which he attended for four years. He did not distinguish himself academically, and an early school report describes his performance as “only fair. Perhaps better in Latin than in any other subject. Very poor in spelling”. Though he had difficulty with mathematics and languages (possibly because he was tone deaf), he was fascinated by biology and zoology. In 1879 the family moved to Bedford Park taking a two-year lease on 8 Woodstock Road. For financial reasons, the family returned to Dublin toward the end of 1880, living at first in the suburbs of Harold’s Cross and later Howth. In October 1881, Yeats resumed his education at Dublin’s Erasmus Smith High School. His father’s studio was nearby and William spent a great deal of time there, where he met many of the city’s artists and writers. During this period he started writing poetry, and, in 1885, the Dublin University Review published Yeats’s first poems, as well as an essay entitled “The Poetry of Sir Samuel Ferguson”. Between 1884 and 1886, William attended the Metropolitan School of Art—now the National College of Art and Design—in Thomas Street. In March 1888 the family moved to 3 Blenheim Road in Bedford Park. The rent on the house was £50 a year.He began writing his first works when he was seventeen; these included a poem—heavily influenced by Percy Bysshe Shelley—that describes a magician who set up a throne in central Asia. Other pieces from this period include a draft of a play about a bishop, a monk, and a woman accused of paganism by local shepherds, as well as love-poems and narrative lyrics on German knights. The early works were both conventional and, according to the critic Charles Johnston, “utterly unIrish”, seeming to come out of a “vast murmurous gloom of dreams”. Although Yeats’s early works drew heavily on Shelley, Edmund Spenser, and on the diction and colouring of pre-Raphaelite verse, he soon turned to Irish mythology and folklore and the writings of William Blake. In later life, Yeats paid tribute to Blake by describing him as one of the “great artificers of God who uttered great truths to a little clan”. In 1891, Yeats published John Sherman and “Dhoya”, one a novella, the other a story. The influence of Oscar Wilde is evident in Yeats’s theory of aesthetics, especially in his stage plays, and runs like a motif through his early works. The theory of masks, developed by Wilde in his polemic The Decay of Lying can clearly be seen in Yeats’s play The Player Queen, while the more sensual characterisation of Salomé, in Wildes play of the same name, provides the template for the changes Yeats made in his later plays, especially in On Baile’s Strand (1904), Deirdre (1907), and his dance play The King of the Great Clock Tower (1934). Young poet The family returned to London in 1887. In March 1890 Yeats joined the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, and with Ernest Rhys co-founded the Rhymers’ Club, a group of London-based poets who met regularly in a Fleet Street tavern to recite their verse. Yeats later sought to mythologize the collective, calling it the “Tragic Generation” in his autobiography, and published two anthologies of the Rhymers’ work, the first one in 1892 and the second one in 1894. He collaborated with Edwin Ellis on the first complete edition of William Blake’s works, in the process rediscovering a forgotten poem, “Vala, or, the Four Zoas”.Yeats had a lifelong interest in mysticism, spiritualism, occultism and astrology. He read extensively on the subjects throughout his life, became a member of the paranormal research organisation “The Ghost Club” (in 1911) and was especially influenced by the writings of Emanuel Swedenborg. As early as 1892, he wrote: “If I had not made magic my constant study I could not have written a single word of my Blake book, nor would The Countess Kathleen ever have come to exist. The mystical life is the centre of all that I do and all that I think and all that I write.” His mystical interests—also inspired by a study of Hinduism, under the Theosophist Mohini Chatterjee, and the occult—formed much of the basis of his late poetry. Some critics disparaged this aspect of Yeats’s work.His first significant poem was “The Island of Statues”, a fantasy work that took Edmund Spenser and Shelley for its poetic models. The piece was serialized in the Dublin University Review. Yeats wished to include it in his first collection, but it was deemed too long, and in fact was never republished in his lifetime. Quinx Books published the poem in complete form for the first time in 2014. His first solo publication was the pamphlet Mosada: A Dramatic Poem (1886), which comprised a print run of 100 copies paid for by his father. This was followed by the collection The Wanderings of Oisin and Other Poems (1889), which arranged a series of verse that dated as far back as the mid-1880s. The long title poem contains, in the words of his biographer R. F. Foster, "obscure Gaelic names, striking repetitions [and] an unremitting rhythm subtly varied as the poem proceeded through its three sections"; “The Wanderings of Oisin” is based on the lyrics of the Fenian Cycle of Irish mythology and displays the influence of both Sir Samuel Ferguson and the Pre-Raphaelite poets. The poem took two years to complete and was one of the few works from this period that he did not disown in his maturity. Oisin introduces what was to become one of his most important themes: the appeal of the life of contemplation over the appeal of the life of action. Following the work, Yeats never again attempted another long poem. His other early poems, which are meditations on the themes of love or mystical and esoteric subjects, include Poems (1895), The Secret Rose (1897), and The Wind Among the Reeds (1899). The covers of these volumes were illustrated by Yeats’s friend Althea Gyles.During 1885, Yeats was involved in the formation of the Dublin Hermetic Order. The society held its first meeting on 16 June, with Yeats acting as its chairman. The same year, the Dublin Theosophical lodge was opened in conjunction with Brahmin Mohini Chatterjee, who travelled from the Theosophical Society in London to lecture. Yeats attended his first séance the following year. He later became heavily involved with the Theosophy and with hermeticism, particularly with the eclectic Rosicrucianism of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. During séances held from 1912, a spirit calling itself “Leo Africanus” apparently claimed it was Yeats’s Daemon or anti-self, inspiring some of the speculations in Per Amica Silentia Lunae. He was admitted into the Golden Dawn in March 1890 and took the magical motto Daemon est Deus inversus—translated as 'Devil is God inverted’. He was an active recruiter for the sect’s Isis-Urania Temple, and brought in his uncle George Pollexfen, Maud Gonne, and Florence Farr. Although he reserved a distaste for abstract and dogmatic religions founded around personality cults, he was attracted to the type of people he met at the Golden Dawn. He was involved in the Order’s power struggles, both with Farr and Macgregor Mathers, and was involved when Mathers sent Aleister Crowley to repossess Golden Dawn paraphernalia during the “Battle of Blythe Road”. After the Golden Dawn ceased and splintered into various offshoots, Yeats remained with the Stella Matutina until 1921. Maud Gonne In 1889, Yeats met Maud Gonne, a 23-year-old English heiress and ardent Irish Nationalist. She was eighteen months younger than Yeats and later claimed she met the poet as a “paint-stained art student.” Gonne admired “The Island of Statues” and sought out his acquaintance. Yeats began an obsessive infatuation, and she had a significant and lasting effect on his poetry and his life thereafter. In later years he admitted, "it seems to me that she [Gonne] brought into my life those days—for as yet I saw only what lay upon the surface—the middle of the tint, a sound as of a Burmese gong, an over-powering tumult that had yet many pleasant secondary notes." Yeats’s love was unrequited, in part due to his reluctance to participate in her nationalist activism.In 1891 he visited Gonne in Ireland and proposed marriage, but was rejected. He later admitted that from that point “the troubling of my life began”. Yeats proposed to Gonne three more times: in 1899, 1900 and 1901. She refused each proposal, and in 1903, to his dismay, married the Irish nationalist Major John MacBride. His only other love affair during this period was with Olivia Shakespear, whom he first met in 1894, and parted from in 1897. Yeats derided MacBride in letters and in poetry. He was horrified by Gonne’s marriage, at losing his muse to another man; in addition, her conversion to Catholicism before marriage offended him; Yeats was Protestant/agnostic. He worried his muse would come under the influence of the priests and do their bidding.Gonne’s marriage to MacBride was a disaster. This pleased Yeats, as Gonne began to visit him in London. After the birth of her son, Seán MacBride, in 1904, Gonne and MacBride agreed to end the marriage, although they were unable to agree on the child’s welfare. Despite the use of intermediaries, a divorce case ensued in Paris in 1905. Gonne made a series of allegations against her husband with Yeats as her main 'second’, though he did not attend court or travel to France. A divorce was not granted, for the only accusation that held up in court was that MacBride had been drunk once during the marriage. A separation was granted, with Gonne having custody of the baby and MacBride having visiting rights. Yeats’s friendship with Gonne ended, yet, in Paris in 1908, they finally consummated their relationship. “The long years of fidelity rewarded at last” was how another of his lovers described the event. Yeats was less sentimental and later remarked that “the tragedy of sexual intercourse is the perpetual virginity of the soul.” The relationship did not develop into a new phase after their night together, and soon afterwards Gonne wrote to the poet indicating that despite the physical consummation, they could not continue as they had been: “I have prayed so hard to have all earthly desire taken from my love for you and dearest, loving you as I do, I have prayed and I am praying still that the bodily desire for me may be taken from you too.” By January 1909, Gonne was sending Yeats letters praising the advantage given to artists who abstain from sex. Nearly twenty years later, Yeats recalled the night with Gonne in his poem “A Man Young and Old”: In 1896, Yeats was introduced to Lady Gregory by their mutual friend Edward Martyn. Gregory encouraged Yeats’s nationalism, and convinced him to continue focusing on writing drama. Although he was influenced by French Symbolism, Yeats concentrated on an identifiably Irish content and this inclination was reinforced by his involvement with a new generation of younger and emerging Irish authors. Together with Lady Gregory, Martyn, and other writers including J. M. Synge, Seán O’Casey, and Padraic Colum, Yeats was one of those responsible for the establishment of the “Irish Literary Revival” movement. Apart from these creative writers, much of the impetus for the Revival came from the work of scholarly translators who were aiding in the discovery of both the ancient sagas and Ossianic poetry and the more recent folk song tradition in Irish. One of the most significant of these was Douglas Hyde, later the first President of Ireland, whose Love Songs of Connacht was widely admired. Abbey Theatre In 1899, Yeats, Lady Gregory, Edward Martyn and George Moore began the Irish Literary Theatre to present Irish plays. The ideals of the Abbey were derived from the avant-garde French theatre, which sought to express the "ascendancy of the playwright rather than the actor-manager à l’anglais." The group’s manifesto, which Yeats wrote, declared, "We hope to find in Ireland an uncorrupted & imaginative audience trained to listen by its passion for oratory... & that freedom to experiment which is not found in the theatres of England, & without which no new movement in art or literature can succeed."The collective survived for about two years but was not successful. Working with two Irish brothers with theatrical experience, William and Frank Fay, Yeats’s unpaid yet independently wealthy secretary Annie Horniman, and the leading West End actress Florence Farr, the group established the Irish National Theatre Society. Along with Synge, they acquired property in Dublin and on 27 December 1904 opened the Abbey Theatre. Yeats’s play Cathleen ni Houlihan and Lady Gregory’s Spreading the News were featured on the opening night. Yeats remained involved with the Abbey until his death, both as a member of the board and a prolific playwright. In 1902, he helped set up the Dun Emer Press to publish work by writers associated with the Revival. This became the Cuala Press in 1904, and inspired by the Arts and Crafts Movement, sought to “find work for Irish hands in the making of beautiful things.” From then until its closure in 1946, the press—which was run by the poet’s sisters—produced over 70 titles; 48 of them books by Yeats himself. Yeats met the American poet Ezra Pound in 1909. Pound had travelled to London at least partly to meet the older man, whom he considered “the only poet worthy of serious study.” From that year until 1916, the two men wintered in the Stone Cottage at Ashdown Forest, with Pound nominally acting as Yeats’s secretary. The relationship got off to a rocky start when Pound arranged for the publication in the magazine Poetry of some of Yeats’s verse with Pound’s own unauthorised alterations. These changes reflected Pound’s distaste for Victorian prosody. A more indirect influence was the scholarship on Japanese Noh plays that Pound had obtained from Ernest Fenollosa’s widow, which provided Yeats with a model for the aristocratic drama he intended to write. The first of his plays modelled on Noh was At the Hawk’s Well, the first draft of which he dictated to Pound in January 1916.The emergence of a nationalist revolutionary movement from the ranks of the mostly Roman Catholic lower-middle and working class made Yeats reassess some of his attitudes. In the refrain of "Easter, 1916" ("All changed, changed utterly / A terrible beauty is born"), Yeats faces his own failure to recognise the merits of the leaders of the Easter Rising, due to his attitude towards their ordinary backgrounds and lives.Yeats was close to Lady Gregory and her home place of Coole Park, Co, Galway. He would often visit and stay there as it was a central meeting place for people who supported the resurgence of Irish literature and cultural traditions. His poem, “The Wild Swans at Coole” was written there, between 1916 and 1917. He wrote prefaces for two books of Irish mythological tales, compiled by Augusta, Lady Gregory: Cuchulain of Muirthemne (1902), and Gods and Fighting Men (1904). In the preface of the later he wrote: “One must not expect in these stories the epic lineaments, the many incidents, woven into one great event of, let us say the War for the Brown Bull of Cuailgne, or that of the last gathering at Muirthemne.” Politics Yeats was an Irish Nationalist, who sought a kind of traditional lifestyle articulated through poems such as 'The Fisherman’. However, as his life progressed, he sheltered much of his revolutionary spirit and distanced himself from the intense political landscape until 1922, when he was appointed Senator for the Irish Free State.In the earlier part of his life, Yeats was a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood. Due to the escalating tension of the political scene, Yeats distanced himself from the core political activism in the midst of the Easter Rising, even holding back his poetry inspired by the events until 1920. In the 1930s Yeats was fascinated with the authoritarian, anti-democratic, nationalist movements of Europe, and he composed several marching songs for the right-wing Blueshirts, although they were never used. He was a fierce opponent of individualism and political liberalism, and saw the fascist movements as a triumph of public order and the needs of the national collective over petty individualism. On the other hand, he was also an elitist who abhorred the idea of mob-rule, and saw democracy as a threat to good governance and public order. After the Blueshirt movement began to falter in Ireland, he distanced himself somewhat from his previous views, but maintained a preference for authoritarian and nationalist leadership. D. P. Moran called him a minor poet and “crypto-Protestant conman.” Marriage to Georgie Hyde Lees By 1916, Yeats was 51 years old and determined to marry and produce an heir. His rival John MacBride had been executed for his role in the 1916 Easter Rising, so Yeats hoped that his widow might remarry. His final proposal to Maud Gonne took place in mid-1916. Gonne’s history of revolutionary political activism, as well as a series of personal catastrophes in the previous few years of her life—including chloroform addiction and her troubled marriage to MacBride—made her a potentially unsuitable wife; biographer R. F. Foster has observed that Yeats’s last offer was motivated more by a sense of duty than by a genuine desire to marry her. Yeats proposed in an indifferent manner, with conditions attached, and he both expected and hoped she would turn him down. According to Foster “when he duly asked Maud to marry him, and was duly refused, his thoughts shifted with surprising speed to her daughter.” Iseult Gonne was Maud’s second child with Lucien Millevoye, and at the time was twenty-one years old. She had lived a sad life to this point; conceived as an attempt to reincarnate her short-lived brother, for the first few years of her life she was presented as her mother’s adopted niece. When Maud told her that she was going to marry, Iseult cried and told her mother that she hated MacBride. When Gonne took action to divorce MacBride in 1905, the court heard allegations that he had sexually assaulted Iseult, then eleven. At fifteen, she proposed to Yeats. In 1917, he proposed to Iseult, but was rejected. That September, Yeats proposed to 25-year-old Georgie Hyde-Lees (1892–1968), known as George, whom he had met through Olivia Shakespear. Despite warnings from her friends—"George... you can’t. He must be dead"—Hyde-Lees accepted, and the two were married on 20 October. Their marriage was a success, in spite of the age difference, and in spite of Yeats’s feelings of remorse and regret during their honeymoon. The couple went on to have two children, Anne and Michael. Although in later years he had romantic relationships with other women, Georgie herself wrote to her husband “When you are dead, people will talk about your love affairs, but I shall say nothing, for I will remember how proud you were.”During the first years of marriage, they experimented with automatic writing; she contacted a variety of spirits and guides they called “Instructors” while in a trance. The spirits communicated a complex and esoteric system of philosophy and history, which the couple developed into an exposition using geometrical shapes: phases, cones, and gyres. Yeats devoted much time to preparing this material for publication as A Vision (1925). In 1924, he wrote to his publisher T. Werner Laurie, admitting: “I dare say I delude myself in thinking this book my book of books”. Nobel Prize In December 1923, Yeats was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, “for his always inspired poetry, which in a highly artistic form gives expression to the spirit of a whole nation”. He was aware of the symbolic value of an Irish winner so soon after Ireland had gained independence, and sought to highlight the fact at each available opportunity. His reply to many of the letters of congratulations sent to him contained the words: “I consider that this honour has come to me less as an individual than as a representative of Irish literature, it is part of Europe’s welcome to the Free State.”Yeats used the occasion of his acceptance lecture at the Royal Academy of Sweden to present himself as a standard-bearer of Irish nationalism and Irish cultural independence. As he remarked, “The theatres of Dublin were empty buildings hired by the English traveling companies, and we wanted Irish plays and Irish players. When we thought of these plays we thought of everything that was romantic and poetical, because the nationalism we had called up—the nationalism every generation had called up in moments of discouragement—was romantic and poetical.” The prize led to a significant increase in the sales of his books, as his publishers Macmillan sought to capitalise on the publicity. For the first time he had money, and he was able to repay not only his own debts, but those of his father. Old age and death By early 1925, Yeats’s health had stabilised, and he had completed most of the writing for A Vision (dated 1925, it actually appeared in January 1926, when he almost immediately started rewriting it for a second version). He had been appointed to the first Irish Senate in 1922, and was re-appointed for a second term in 1925. Early in his tenure, a debate on divorce arose, and Yeats viewed the issue as primarily a confrontation between the emerging Roman Catholic ethos and the Protestant minority. When the Roman Catholic Church weighed in with a blanket refusal to consider their anti position, The Irish Times countered that a measure to outlaw divorce would alienate Protestants and “crystallise” the partition of Ireland. In response, Yeats delivered a series of speeches that attacked the “quixotically impressive” ambitions of the government and clergy, likening their campaign tactics to those of “medieval Spain.” “Marriage is not to us a Sacrament, but, upon the other hand, the love of a man and woman, and the inseparable physical desire, are sacred. This conviction has come to us through ancient philosophy and modern literature, and it seems to us a most sacrilegious thing to persuade two people who hate each other... to live together, and it is to us no remedy to permit them to part if neither can re-marry.” The resulting debate has been described as one of Yeats’s “supreme public moments”, and began his ideological move away from pluralism towards religious confrontation. His language became more forceful; the Jesuit Father Peter Finlay was described by Yeats as a man of “monstrous discourtesy”, and he lamented that, “It is one of the glories of the Church in which I was born that we have put our Bishops in their place in discussions requiring legislation”. During his time in the Senate, Yeats further warned his colleagues: “If you show that this country, southern Ireland, is going to be governed by Roman Catholic ideas and by Catholic ideas alone, you will never get the North... You will put a wedge in the midst of this nation”. He memorably said of his fellow Irish Protestants, “we are no petty people”. In 1924, he chaired a coinage committee charged with selecting a set of designs for the first currency of the Irish Free State. Aware of the symbolic power latent in the imagery of a young state’s currency, he sought a form that was “elegant, racy of the soil, and utterly unpolitical”. When the house finally decided on the artwork of Percy Metcalfe, Yeats was pleased, though he regretted that compromise had led to “lost muscular tension” in the finally depicted images. He retired from the Senate in 1928 because of ill health. Towards the end of his life—and especially after the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and Great Depression, which led some to question whether democracy could cope with deep economic difficulty—Yeats seems to have returned to his aristocratic sympathies. During the aftermath of the First World War, he became sceptical about the efficacy of democratic government, and anticipated political reconstruction in Europe through totalitarian rule. His later association with Pound drew him towards Benito Mussolini, for whom he expressed admiration on a number of occasions. He wrote three “marching songs”—never used—for the Irish General Eoin O’Duffy’s Blueshirts. At the age of 69 he was 'rejuvenated’ by the Steinach operation which was performed on 6 April 1934 by Norman Haire. For the last five years of his life Yeats found a new vigour evident from both his poetry and his intimate relations with younger women. During this time, Yeats was involved in a number of romantic affairs with, among others, the poet and actress Margot Ruddock, and the novelist, journalist and sexual radical Ethel Mannin. As in his earlier life, Yeats found erotic adventure conducive to his creative energy, and, despite age and ill-health, he remained a prolific writer. In a letter of 1935, Yeats noted: “I find my present weakness made worse by the strange second puberty the operation has given me, the ferment that has come upon my imagination. If I write poetry it will be unlike anything I have done”. In 1936, he undertook editorship of the Oxford Book of Modern Verse, 1892–1935.He died at the Hôtel Idéal Séjour, in Menton, France, on 28 January 1939, aged 73. He was buried after a discreet and private funeral at Roquebrune-Cap-Martin. Attempts had been made at Roquebrune to dissuade the family from proceeding with the removal of the remains to Ireland due to the uncertainty of their identity. His body had earlier been exhumed and transferred to the ossuary. Yeats and George had often discussed his death, and his express wish was that he be buried quickly in France with a minimum of fuss. According to George, "His actual words were 'If I die bury me up there [at Roquebrune] and then in a year’s time when the newspapers have forgotten me, dig me up and plant me in Sligo’." In September 1948, Yeats’s body was moved to the churchyard of St Columba’s Church, Drumcliff, County Sligo, on the Irish Naval Service corvette LÉ Macha. The person in charge of this operation for the Irish Government was Seán MacBride, son of Maud Gonne MacBride, and then Minister of External Affairs. His epitaph is taken from the last lines of “Under Ben Bulben”, one of his final poems: French ambassador Stanislas Ostroróg was involved in returning the remains of the Irish poet from France to Ireland in 1948; in a letter to the European director of the Foreign Ministry in Paris “Ostrorog tells how Yeats’s son Michael sought official help in locating the poet’s remains. Neither Michael Yeats nor Sean MacBride, the Irish foreign minister who organised the ceremony, wanted to know the details of how the remains were collected, Ostrorog notes. He repeatedly urges caution and discretion and says the Irish ambassador in Paris should not be informed.” Yeats’ body was exhumed in 1946 and the remains were moved to on ossuary and mixed with other remains. The French Foreign Ministry authorized Ostrorog to secretly cover the cost of repatriation from his slush fund. Authorities were worried about the fact that the much-loved poet’s remains were thrown into a communal grave, causing embarrassment for both Ireland and France. “Mr Rebouillat, (a) forensic doctor in Roquebrune would be able to reconstitute a skeleton presenting all the characteristics of the deceased.” per a letter from Ostroróg to his superiors. Style Yeats is generally considered one of the twentieth century key English language poets. He was a Symbolist poet, using allusive imagery and symbolic structures throughout his career. He chose words and assembled them so that, in addition to a particular meaning, they suggest abstract thoughts that may seem more significant and resonant. His use of symbols is usually something physical that is both itself and a suggestion of other, perhaps immaterial, timeless qualities. Unlike other modernists who experimented with free verse, Yeats was a master of the traditional forms. The impact of modernism on his work can be seen in the increasing abandonment of the more conventionally poetic diction of his early work in favour of the more austere language and more direct approach to his themes that increasingly characterises the poetry and plays of his middle period, comprising the volumes In the Seven Woods, Responsibilities and The Green Helmet. His later poetry and plays are written in a more personal vein, and the works written in the last twenty years of his life include mention of his son and daughter, as well as meditations on the experience of growing old. In his poem, “The Circus Animals’ Desertion”, he describes the inspiration for these late works: During 1929, he stayed at Thoor Ballylee near Gort in County Galway (where Yeats had his summer home since 1919) for the last time. Much of the remainder of his life was lived outside Ireland, although he did lease Riversdale house in the Dublin suburb of Rathfarnham in 1932. He wrote prolifically through his final years, and published poetry, plays, and prose. In 1938, he attended the Abbey for the final time to see the premiere of his play Purgatory. His Autobiographies of William Butler Yeats was published that same year. In 1913, Yeats wrote the preface for the English translation of Rabindranath Tagore’s Gitanjali (Song Offering) for which Tagore received Nobel Prize in literature. While Yeats’s early poetry drew heavily on Irish myth and folklore, his later work was engaged with more contemporary issues, and his style underwent a dramatic transformation. His work can be divided into three general periods. The early poems are lushly pre-Raphaelite in tone, self-consciously ornate, and, at times, according to unsympathetic critics, stilted. Yeats began by writing epic poems such as The Isle of Statues and The Wanderings of Oisin. His other early poems are lyrics on the themes of love or mystical and esoteric subjects. Yeats’s middle period saw him abandon the pre-Raphaelite character of his early work and attempt to turn himself into a Landor-style social ironist.Critics who admire his middle work might characterize it as supple and muscular in its rhythms and sometimes harshly modernist, while others find these poems barren and weak in imaginative power. Yeats’s later work found new imaginative inspiration in the mystical system he began to work out for himself under the influence of spiritualism. In many ways, this poetry is a return to the vision of his earlier work. The opposition between the worldly minded man of the sword and the spiritually minded man of God, the theme of The Wanderings of Oisin, is reproduced in A Dialogue Between Self and Soul.Some critics claim that Yeats spanned the transition from the nineteenth century into twentieth-century modernism in poetry much as Pablo Picasso did in painting while others question whether late Yeats has much in common with modernists of the Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot variety.Modernists read the well-known poem “The Second Coming” as a dirge for the decline of European civilisation, but it also expresses Yeats’s apocalyptic mystical theories, and is shaped by the 1890s. His most important collections of poetry started with The Green Helmet (1910) and Responsibilities (1914). In imagery, Yeats’s poetry became sparer and more powerful as he grew older. The Tower (1928), The Winding Stair (1933), and New Poems (1938) contained some of the most potent images in twentieth-century poetry.Yeats’s mystical inclinations, informed by Hinduism, theosophical beliefs and the occult, provided much of the basis of his late poetry, which some critics have judged as lacking in intellectual credibility. The metaphysics of Yeats’s late works must be read in relation to his system of esoteric fundamentals in A Vision (1925). Legacy Yeats is commemorated in Sligo town by a statue, created in 1989 by sculptor Ronan Gillespie. It was erected outside the Ulster Bank, at the corner of Stephen Street and Markievicz Road, on the 50th anniversary of the poet’s death. Yeats had remarked, on receiving his Nobel Prize that the Royal Palace in Stockholm “resembled the Ulster Bank in Sligo”. Across the river is the Yeats Memorial Building, home to the Sligo Yeats Society. References Wikipedia—yeats