Info

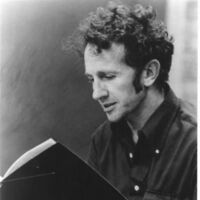

Henry Charles Bukowski (born Heinrich Karl Bukowski; August 16, 1920 – March 9, 1994) was an American poet, novelist and short story writer. His writing was influenced by the social, cultural and economic ambience of his home city of Los Angeles. It is marked by an emphasis on the ordinary lives of poor Americans, the act of writing, alcohol, relationships with women and the drudgery of work.

Emily Elizabeth Dickinson (December 10, 1830 – May 15, 1886) was an American poet. Little-known during her life, she has since been regarded as one of the most important figures in American poetry. Evidence suggests that Dickinson lived much of her life in isolation. Considered an eccentric by locals, she developed a penchant for white clothing and was known for her reluctance to greet guests or, later in life, to even leave her bedroom. Dickinson never married, and most friendships between her and others depended entirely upon correspondence.

Ella Wheeler Wilcox (November 5, 1850 – October 30, 1919) was an American author and poet. Her best-known work was Poems of Passion. Her most enduring work was “Solitude”, which contains the lines, “Laugh, and the world laughs with you; weep, and you weep alone”. Her autobiography, The Worlds and I, was published in 1918, a year before her death. Ella was born on a farm in Johnstown, Wisconsin, east of Janesville, the youngest of four children. The family soon moved north of Madison. She started writing poetry at a very early age, and was well known as a poet in her own state by the time she graduated from high school. Her most famous poem, “Solitude”, was first published in the February 25, 1883 issue of The New York Sun. The inspiration for the poem came as she was travelling to attend the Governor’s inaugural ball in Madison, Wisconsin. On her way to the celebration, there was a young woman dressed in black sitting across the aisle from her. The woman was crying. Miss Wheeler sat next to her and sought to comfort her for the rest of the journey. When they arrived, the poet was so depressed that she could barely attend the scheduled festivities. As she looked at her own radiant face in the mirror, she suddenly recalled the sorrowful widow. It was at that moment that she wrote the opening lines of “Solitude”: Laugh, and the world laughs with you; Weep, and you weep alone. For the sad old earth must borrow its mirth But has trouble enough of its own

#Americans #Women #XIXCentury #XXCentury

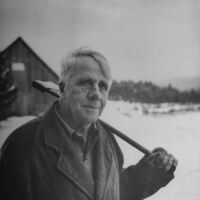

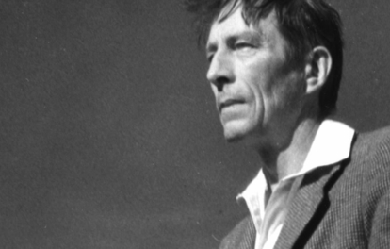

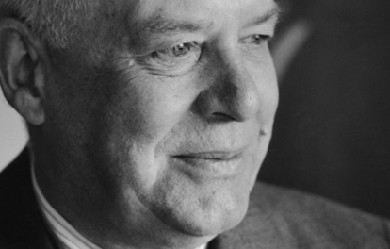

Robert Lee Frost (March 26, 1874 – January 29, 1963) was an American poet. His work was initially published in England before it was published in the United States. Known for his realistic depictions of rural life and his command of American colloquial speech, Frost frequently wrote about settings from rural life in New England in the early 20th century, using them to examine complex social and philosophical themes. Frequently honored during his lifetime, Frost is the only poet to receive four Pulitzer Prizes for Poetry. He became one of America’s rare “public literary figures, almost an artistic institution”. He was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in 1960 for his poetic works. On July 22, 1961, Frost was named poet laureate of Vermont.

#Americans #PulitzerPrize #XIXCentury #XXCentury

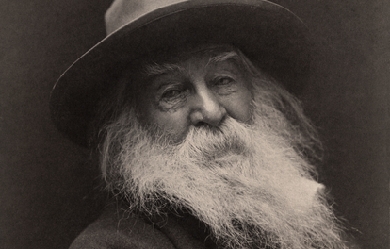

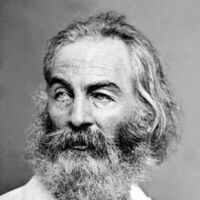

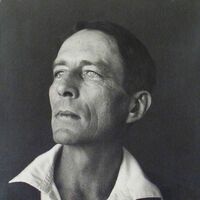

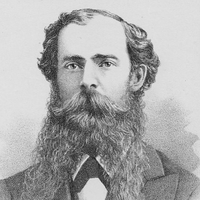

Walter Whitman (May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist and journalist. A humanist, he was a part of the transition between transcendentalism and realism, incorporating both views in his works. Whitman is among the most influential poets in the American canon, often called the father of free verse. His work was controversial in his time, particularly his 1855 poetry collection Leaves of Grass, which was described as obscene for its overt sensuality.

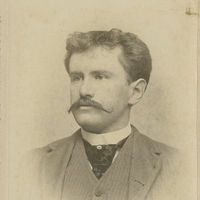

Madison Julius Cawein (March 23, 1865 – December 8, 1914) was a poet from Louisville, Kentucky. He was the fifth child of William and Christiana (Stelsly) Cawein. His father made patent medicines from herbs thus, as a child, Cawein became acquainted with and developed a love for local nature.

#Americans #XIXCentury #XXCentury

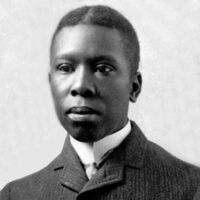

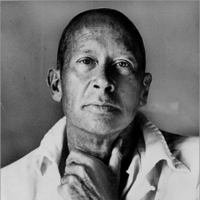

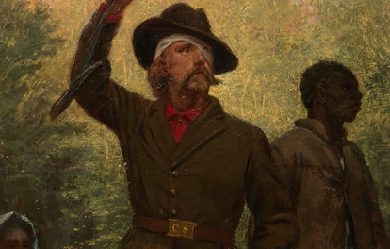

Paul Laurence Dunbar was the first African-American poet to garner national critical acclaim. Born in Dayton, Ohio, in 1872, Dunbar penned a large body of dialect poems, standard English poems, essays, novels and short stories before he died at the age of 33. His work often addressed the difficulties encountered by members of his race and the efforts of African-Americans to achieve equality in America. He was praised both by the prominent literary critics of his time and his literary contemporaries. Dunbar was born on June 27, 1872, to Matilda and Joshua Dunbar, both natives of Kentucky. His mother was a former slave and his father had escaped from slavery and served in the 55th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment and the 5th Massachusetts Colored Cavalry Regiment during the Civil War. Matilda and Joshua had two children before separating in 1874. Matilda also had two children from a previous marriage.

#Americans #Blacks #XIXCentury

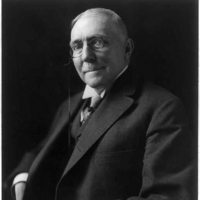

Carl Sandburg was born in Galesburg, Illinois, on January 6, 1878. His parents, August and Clara Johnson, had emigrated to America from the north of Sweden. After encountering several August Johnsons in his job for the railroad, the Sandburg's father renamed the family. The Sandburgs were very poor; Carl left school at the age of thirteen to work odd jobs, from laying bricks to dishwashing, to help support his family. At seventeen, he traveled west to Kansas as a hobo. He then served eight months in Puerto Rico during the Spanish-American war. While serving, Sandburg met a student at Lombard College, the small school located in Sandburg's hometown. The young man convinced Sandburg to enroll in Lombard after his return from the war.

#Americans #PulitzerPrice #XIXCentury #XXCentury

James Whitcomb Riley (October 7, 1849 – July 22, 1916) was an American writer, poet, and best-selling author. During his lifetime he was known as the "Hoosier Poet" and "Children's Poet" for his dialect works and his children's poetry respectively. His poems tended to be humorous or sentimental, and of the approximately one thousand poems that Riley authored, the majority are in dialect. His famous works include "Little Orphant Annie" and "The Raggedy Man". Riley began his career writing verses as a sign maker and submitting poetry to newspapers. Thanks in part to an endorsement from poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, he eventually earned successive jobs at Indiana newspaper publishers during the latter 1870s. Riley gradually rose in prominence during the 1880s through his poetry reading tours. He traveled a touring circuit first in the Midwest, and then nationally, holding shows and making joint appearances on stage with other famous talents. Regularly struggling with his alcohol addiction, Riley never married or had children, and created a scandal in 1888 when he became too drunk to perform.

#Americans #XIXCentury #XXCentury

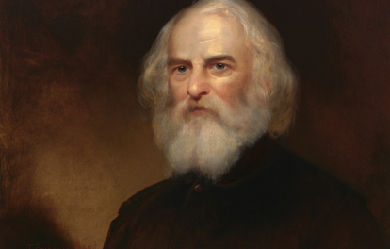

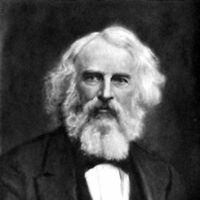

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (February 27, 1807 – March 24, 1882) was an American poet and educator whose works include "Paul Revere's Ride", The Song of Hiawatha, and Evangeline. He was also the first American to translate Dante Alighieri's The Divine Comedy and was one of the five Fireside Poets. Longfellow was born in Portland, Maine, then part of Massachusetts, and studied at Bowdoin College. After spending time in Europe he became a professor at Bowdoin and, later, at Harvard College. His first major poetry collections were Voices of the Night (1839) and Ballads and Other Poems (1841). Longfellow retired from teaching in 1854 to focus on his writing, living the remainder of his life in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in a former headquarters of George Washington. His first wife, Mary Potter, died in 1835 after a miscarriage. His second wife, Frances Appleton, died in 1861 after sustaining burns from her dress catching fire. After her death, Longfellow had difficulty writing poetry for a time and focused on his translation. He died in 1882.

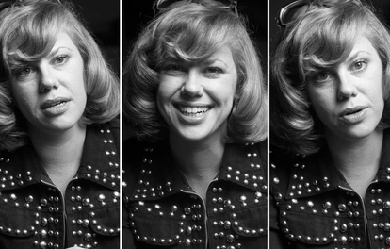

Anne Sexton (November 9, 1928, Newton, Massachusetts – October 4, 1974, Weston, Massachusetts) was an American poetese, known for her highly personal, confessional verse. She won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry in 1967. Themes of her poetry include her suicidal tendencies, long battle against depression and various intimate details from her private life, including her relationships with her husband and children. Sexton suffered from severe mental illness for much of her life, her first manic episode taking place in 1954.

#Americans #Suicide #Women #XXCentury

Sheldon Allan Shel Silverstein (September 25, 1930 – May 10, 1999), was an American poet, singer-songwriter, cartoonist, screenwriter, and author of children's books. He styled himself as Uncle Shelby in some works. Translated into more than 30 languages, his books have sold over 20 million copies.

#Americans #Children #Jews #XXCentury

Sylvia Plath (October 27, 1932 – February 11, 1963) was an American poet, novelist and short story writer. Born in Boston, Massachusetts, she studied at Smith College and Newnham College, Cambridge before receiving acclaim as a professional poet and writer. She married fellow poet Ted Hughes in 1956 and they lived together first in the United States and then England, having two children together: Frieda and Nicholas. Following a long struggle with depression and a marital separation, Plath committed suicide in 1963. Controversy continues to surround the events of her life and death, as well as her writing and legacy. Plath is credited with advancing the genre of confessional poetry and is best known for her two published collections: The Colossus and Other Poems and Ariel. In 1982, she became the first poet to win a Pulitzer Prize posthumously, for The Collected Poems. She also wrote The Bell Jar, a semi-autobiographical novel published shortly before her death.

#Americans #Suicide #Women #XXCentury

Oliver Wendell Holmes (August 29, 1809 – October 7, 1894) was an American physician, poet, and polymath based in Boston. Grouped among the fireside poets, he was acclaimed by his peers as one of the best writers of the day. His most famous prose works are the "Breakfast-Table" series, which began with The Autocrat of the Breakfast-Table (1858). He was also an important medical reformer. In addition to his work as an author and poet, Holmes also served as a physician, professor, lecturer, inventor, and, although he never practiced it, he received formal training in law.

Ambrose Gwinnett Bierce (June 24, 1842 – circa 1914) was an American Civil War soldier, wit, and writer. Bierce’s book The Devil’s Dictionary was named as one of “The 100 Greatest Masterpieces of American Literature” by the American Revolution Bicentennial Administration. His story An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge has been described as “one of the most famous and frequently anthologized stories in American literature”; and his book Tales of Soldiers and Civilians (also published as In the Midst of Life) was named by the Grolier Club as one of the 100 most influential American books printed before 1900.

#Americans #XIXCentury #XXCentury

Frederic Ogden Nash (August 19, 1902 – May 19, 1971) was an American poet well known for his light verse. At the time of his death in 1971, The New York Times said his “droll verse with its unconventional rhymes made him the country’s best-known producer of humorous poetry”. Nash wrote over 500 pieces of comic verse. The best of his work was published in 14 volumes between 1931 and 1972.

John Greenleaf Whittier (December 17, 1807 – September 7, 1892) was an American Quaker poet and advocate of the abolition of slavery in the United States. Frequently listed as one of the Fireside Poets, he was influenced by the Scottish poet Robert Burns. Whittier is remembered particularly for his anti-slavery writings as well as his book Snow-Bound.

Edgar Lee Masters (August 23, 1868 – March 5, 1950) was an American attorney, poet, biographer, and dramatist born in Garnett, Kansas. He is the author of Spoon River Anthology, The New Star Chamber and Other Essays, Songs and Satires, The Great Valley, The Serpent in the Wilderness An Obscure Tale, The Spleen, Mark Twain: A Portrait, Lincoln: The Man, and Illinois Poems. In all, Masters published twelve plays, twenty-one books of poetry, six novels and six biographies, including those of Abraham Lincoln, Mark Twain, Vachel Lindsay, and Walt Whitman.

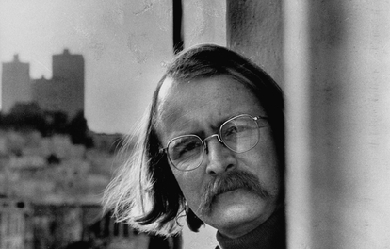

Ezra Weston Loomis Pound (30 October 1885 – 1 November 1972) was an American expatriate poet, critic and a major figure of the early modernist movement. His contribution to poetry began with his promotion of Imagism, a movement that derived its technique from classical Chinese and Japanese poetry, stressing clarity, precision and economy of language. His best-known works include Ripostes (1912), Hugh Selwyn Mauberley (1920), and his unfinished 120-section epic, The Cantos (1917–1969). Working in London in the early 20th century as foreign editor of several American literary magazines, Pound helped to discover and shape the work of contemporaries such as T. S. Eliot, James Joyce, Robert Frost, and Ernest Hemingway. He was responsible for the publication in 1915 of Eliot's “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” and for the serialization from 1918 of Joyce's Ulysses. Hemingway wrote of him in 1925: “He defends [his friends] when they are attacked, he gets them into magazines and out of jail. ... He writes articles about them. He introduces them to wealthy women. He gets publishers to take their books. He sits up all night with them when they claim to be dying... he advances them hospital expenses and dissuades them from suicide.”

Sara Teasdale (August 8, 1884 – January 29, 1933) was an American lyric poet. She was born Sarah Trevor Teasdale in St. Louis, Missouri, and used the name Sara Teasdale Filsinger after her marriage in 1914. She had such poor health for so much of her childhood, home schooled until age 9, that it was only at age 10 that she was well enough to begin school. She started at Mary Institute in 1898, but switched to Hosmer Hall in 1899, graduating in 1903. I Shall Not Care WHEN I am dead and over me bright April Shakes out her rain-drenched hair, Tho' you should lean above me broken-hearted, I shall not care. I shall have peace, as leafy trees are peaceful When rain bends down the bough, And I shall be more silent and cold-hearted Than you are now.

#Americans #PulitzerPrize #Suicide #Women #XXCentury

William Carlos Williams (September 17, 1883 – March 4, 1963) was an American poet closely associated with modernism and Imagism. He was also a pediatrician and general practitioner of medicine with a medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine. Williams "worked harder at being a writer than he did at being a physician" but excelled at both. Although his primary occupation was as a family doctor, Williams had a successful literary career as a poet. In addition to poetry (his main literary focus), he occasionally wrote short stories, plays, novels, essays, and translations. He practiced medicine by day and wrote at night. Early in his career, he briefly became involved in the Imagist movement through his friendships with Ezra Pound and H.D. (also known as Hilda Doolittle, another well-known poet whom he befriended while attending the University of Pennsylvania), but soon he began to develop opinions that differed from those of his poet/friends.

#Americans #Modernism #XXCentury

Edward Estlin Cummings (October 14, 1894 – September 3, 1962), popularly known as E. E. Cummings, with the abbreviated form of his name often written by others in lowercase letters as e.e. cummings (in the style of some of his poems—see name and capitalization, below), was an American poet, painter, essayist, author, and playwright. His body of work encompasses approximately 2,900 poems, two autobiographical novels, four plays and several essays, as well as numerous drawings and paintings. He is remembered as a preeminent voice of 20th century poetry.

#Americans #Modernism #XXCentury

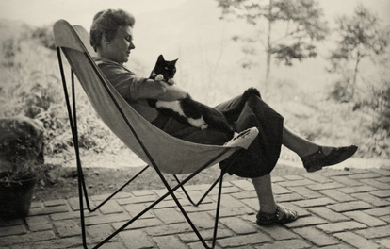

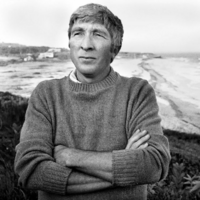

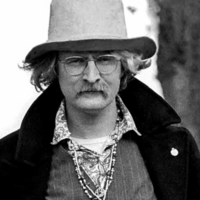

John Robinson Jeffers (January 10, 1887 – January 20, 1962) was an American poet, known for his work about the central California coast. Much of Jeffers' poetry was written in narrative and epic form, but he is also known for his shorter verse and is considered an icon of the environmental movement. Influential and highly regarded in some circles, despite or because of his philosophy of "inhumanism," Jeffers believed that transcending conflict required human concerns to be de-emphasized in favor of the boundless whole. This led him to oppose U.S. participation in World War II, a stand that was controversial at the time. Jeffers was born in Allegheny, Pennsylvania (now part of Pittsburgh), the son of a Presbyterian minister and biblical scholar, Reverend Dr. William Hamilton Jeffers, and Annie Robinson Tuttle. His brother was Hamilton Jeffers, who became a well-known astronomer, working at Lick Observatory. His family was supportive of his interest in poetry. He traveled through Europe during his youth and attended school in Switzerland. He was a child prodigy, interested in classics and Greek and Latin language and literature. At sixteen he entered Occidental College. At school, he was an avid outdoorsman, and active in the school's literary societies. After he graduated from Occidental, Jeffers went to the University of Southern California to study at first literature, and then medicine. He met Una Call Kuster in 1906; she was three years older than he was, a graduate student, and the wife of a Los Angeles attorney. In 1910 he enrolled as a forestry student at the University of Washington in Seattle, a course of study that he abandoned after less than one year, at which time he returned to Los Angeles. Sometime before this, he and Una had begun an affair that became a scandal, reaching the front page of the Los Angeles Times in 1912. After Una spent some time in Europe to quiet things down, the two were married in 1913, and moved to Carmel, California, where Jeffers constructed Tor House and Hawk Tower. The couple had a daughter who died a day after birth in 1914, and then twin sons (Donnan and Garth) in 1916. Una died of cancer in 1950. Jeffers died in 1962; an obituary can be found in the New York Times, January 22, 1962. Poetic career In the 1920s and 1930s, at the height of his popularity, Jeffers was famous for being a tough outdoorsman, living in relative solitude and writing of the difficulty and beauty of the wild. He spent most of his life in Carmel, California, in a granite house that he had built himself called "Tor House and Hawk Tower". Tor is a term for a craggy outcrop or lookout. Before Jeffers and Una purchased the land where Tor House would be built, they rented two cottages in Carmel, and enjoyed many afternoon walks and picnics at the "tors" near the site that would become Tor House. To build the first part of Tor House, a small, two story cottage, Jeffers hired a local builder, Michael Murphy. He worked with Murphy, and in this short, informal apprenticeship, he learned the art of stonemasonry. He continued adding on to Tor House throughout his life, writing in the mornings and working on the house in the afternoon. Many of his poems reflect the influence of stone and building on his life. He later built a large four-story stone tower on the site called Hawk Tower. While he had not visited Ireland at this point in his life, it is possible that Hawk Tower is based on Francis Joseph Bigger's 'Castle Séan' at Ardglass, County Down, which had also in turn influenced Yeats' poets tower, Thoor Ballylee. Construction on Tor House continued into the late 1950s and early 1960s, and was completed by his eldest son. The completed residence was used as a family home until his descendants decided to turn it over to the Tor House Foundation, formed by Ansel Adams, for historic preservation. The romantic Gothic tower was named after a hawk that appeared while Jeffers was working on the structure, and which disappeared the day it was completed. The tower was a gift for his wife Una, who had a fascination for Irish literature and stone towers. In Una's special room on the second floor were kept many of her favorite items, photographs of Jeffers taken by the artist Weston, plants and dried flowers from Shelley's grave, and a rosewood melodeon which she loved to play. The tower also included a secret interior staircase – a source of great fun for his young sons. During this time, Jeffers published volumes of long narrative blank verse that shook up the national literary scene. These poems, including Tamar and Roan Stallion, introduced Jeffers as a master of the epic form, reminiscent of ancient Greek poets. These poems were full of controversial subject matter such as incest, murder and parricide. Jeffers' short verse includes "Hurt Hawks," "The Purse-Seine" and "Shine, Perishing Republic." His intense relationship with the physical world is described in often brutal and apocalyptic verse, and demonstrates a preference for the natural world over what he sees as the negative influence of civilization. Jeffers did not accept the idea that meter is a fundamental part of poetry, and, like Marianne Moore, claimed his verse was not composed in meter, but "rolling stresses." He believed meter was imposed on poetry by man and not a fundamental part of its nature. nitially, Tamar and Other Poems received no acclaim, but when East Coast reviewers discovered the work and began to compare Jeffers to Greek tragedians, Boni & Liveright reissued an expanded edition as Roan Stallion, Tamar and Other Poems (1925). In these works, Jeffers began to articulate themes that contributed to what he later identified as Inhumanism. Mankind was too self-centered, he complained, and too indifferent to the "astonishing beauty of things." Jeffers's longest and most ambitious narrative, The Women at Point Sur (1927), startled many of his readers, heavily loaded as it was with Nietzschean philosophy. The balance of the 1920s and the early 1930s were especially productive for Jeffers, and his reputation was secure. In 1934, he made the acquaintance of the philosopher J Krishnamurti and was struck by the force of Krishnamurti's person. He wrote a poem entitled "Credo" which many feel refers to Krishnamurti. In Cawdor and Other Poems (1928), Dear Judas and Other Poems (1929), Descent to the Dead, Poems Written in Ireland and Great Britain (1931), Thurso's Landing (1932), and Give Your Heart to the Hawks (1933), Jeffers continued to explore the questions of how human beings could find their proper relationship (free of human egocentrism) with the divinity of the beauty of things. These poems, set in the Big Sur region (except Dear Judas and Descent to the Dead), enabled Jeffers to pursue his belief that the natural splendor of the area demanded tragedy: the greater the beauty, the greater the demand. As Euripides had, Jeffers began to focus more on his own characters' psychologies and on social realities than on the mythic. The human dilemmas of Phaedra, Hippolytus, and Medea fascinated him. Many books followed Jeffers' initial success with the epic form, including an adaptation of Euripides' Medea, which became a hit Broadway play starring Dame Judith Anderson. D. H. Lawrence, Edgar Lee Masters, Benjamin De Casseres, and George Sterling were close friends of Jeffers, Sterling having the longest and most intimate relationship with him. While living in Carmel, Jeffers became the focal point for a small but devoted group of admirers. At the peak of his fame, he was one of the few poets to be featured on the cover of Time Magazine. He was also asked to read at the Library of Congress, and was posthumously put on a U.S. postage stamp. Part of the decline of Jeffers' popularity was due to his staunch opposition to the United States' entering World War II. In fact, his book The Double Axe and Other Poems (1948), a volume of poems that was largely critical of U.S. policy, came with an extremely unconventional note from Random House that the views expressed by Jeffers were not those of the publishing company. Soon after, his work was received negatively by several influential literary critics. Several particularly scathing pieces were penned by Yvor Winters, as well as by Kenneth Rexroth, who had been very positive in his earlier commentary on Jeffers' work. Jeffers would publish poetry intermittently during the 1950s but his poetry never again attained the same degree of popularity that it had in the 1920s and the 1930s. Inhumanism Jeffers coined the word inhumanism, the belief that mankind is too self-centered and too indifferent to the "astonishing beauty of things." In the famous poem "Carmel Point," Jeffers called on humans to "uncenter" themselves. In "The Double Axe," Jeffers explicitly described inhumanism as "a shifting of emphasis and significance from man to notman; the rejection of human solipsism and recognition of the trans-human magnificence. ... This manner of thought and feeling is neither misanthropic nor pessimist. ... It offers a reasonable detachment as rule of conduct, instead of love, hate and envy ... it provides magnificence for the religious instinct, and satisfies our need to admire greatness and rejoice in beauty." In The Loyalties of Robinson Jeffers,the first in-depth study of Jeffers not written by one of his circle, poet and critic J. Radcliffe Squires addresses the question of a reconciliation of the beauty of the world and potential beauty in mankind: “Jeffers has asked us to look squarely at the universe. He has told us that materialism has its message, its relevance, and its solace. These are different from the message, relevance, and solace of humanism. Humanism teaches us best why we suffer, but materialism teaches us how to suffer.” Influence His poems have been translated into many languages and published all over the world. Outside of the United States he is most popular in Japan and the Czech Republic. William Everson, Edward Abbey, Gary Snyder, and Mark Jarman are just a few recent authors who have been influenced by Jeffers. Charles Bukowski remarked that Jeffers was his favorite poet. Polish poet Czesław Miłosz also took an interest in Jeffers' poetry and worked as a translator for several volumes of his poems. Jeffers also exchanged some letters with his Czech translator and popularizer, the poet Kamil Bednář. Writer Paul Mooney (1904–1939), son of American Indian authority James Mooney (1861–1921) and collaborator of travel writer Richard Halliburton (1900–1939), "was known always to carry with him (a volume of Jeffers) as a chewer might carry a pouch of tobacco ... and, like Jeffers," writes Gerry Max in Horizon Chasers, "worshipped nature ... (taking) refuge (from the encroachments of civilization) in a sort of chthonian mysticism rife with Greek dramatic elements ..." Jeffers was an inspiration and friend to western U.S. photographers of the early twentieth century, including Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, and Morley Baer. In fact, the elegant book of Baer's photographs juxtaposed with Jeffers' poetry, combines the creative talents of those two residents of the Big Sur coast. Although Jeffers has largely been marginalized in the mainstream academic community over the last thirty years, several important contemporary literary critics, including Albert Gelpi of Stanford University, and poet, critic and NEA chairman Dana Gioia, have consistently cited Jeffers as a formidable presence in modern literature. His poem "The Beaks of Eagles" was made into a song by The Beach Boys on their album Holland (1973). Two lines from Jeffers' poem "We Are Those People" are quoted toward the end of the 2008 film Visioneers. Several lines from Jeffers' poem "Wise Men in Their Bad Hours" ("Death's a fierce meadowlark: but to die having made / Something more equal to the centuries / Than muscle and bone, is mostly to shed weakness.") appear in Christopher McCandless' diary. Robinson Jeffers is mentioned in the 2004 film I Heart Huckabees by the character Albert Markovski played by Jason Schwartzman, when defending Jeffers as a nature writer against another character's claim that environmentalism is socialism. Markovski says, "Henry David Thoreau, Robinson Jeffers, the National Geographic Society...all socialists?" Further reading and research The largest collections of Jeffers' manuscripts and materials are in the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin and in the libraries at Occidental College, the University of California, and Yale University. A collection of his letters has been published as The Selected Letters of Robinson Jeffers, 1887–1962 (1968). Other books of criticism and poetry by Jeffers are: Poetry, Gongorism and a Thousand Years (1949), Themes in My Poems (1956), Robinson Jeffers: Selected Poems (1965), The Alpine Christ and Other Poems (1974), What Odd Expedients" and Other Poems (1981), and Rock and Hawk: A Selection of Shorter Poems by Robinson Jeffers (1987). Stanford University Press recently released a five-volume collection of the complete works of Robinson Jeffers. In an article titled, "A Black Sheep Joins the Fold", written upon the release of the collection in 2001, Stanford Magazine commented that it was remarkable that, due to a number of circumstances, "there was never an authoritative, scholarly edition of California’s premier bard" until the complete works published by Stanford. Biographical studies include George Sterling, Robinson Jeffers: The Man and the Artist (1926); Louis Adamic, Robinson Jeffers (1929); Melba Bennett, Robinson Jeffers and the Sea (1936) and The Stone Mason of Tor House (1966); Radcliffe Squires, The Loyalties of Robinson Jeffers (1956); Edith Greenan, Of Una Jeffers (1939); Mabel Dodge Luhan, Una and Robin (1976; written in 1933); Ward Ritchie, Jeffers: Some Recollections of Robinson Jeffers (1977); and James Karman, Robinson Jeffers: Poet of California (1987). Books about Jeffers's career include L. C. Powell, Robinson Jeffers: The Man and His Work (1940; repr. 1973); William Everson, Robinson Jeffers: Fragments of an Older Fury (1968); Arthur B. Coffin, Robinson Jeffers: Poet of Inhumanism (1971); Bill Hotchkiss, Jeffers: The Sivaistic Vision (1975); James Karman, ed., Critical Essays on Robinson Jeffers (1990); Alex Vardamis The Critical Reputation of Robinson Jeffers (1972); and Robert Zaller, ed., Centennial Essays for Robinson Jeffers (1991). The Robinson Jeffers Newsletter, ed. Robert Brophy, is a valuable scholarly resource. In a rare recording, Jeffers can be heard reading his "The Day Is A Poem" (September 19, 1939) on Poetry Speaks – Hear Great Poets Read Their Work from Tennyson to Plath, Narrated by Charles Osgood (Sourcebooks, Inc., c2001), Disc 1, #41; including text, with Robert Hass on Robinson Jeffers, pp. 88–95. Jeffers was also on the cover of Time – The Weekly Magazine, April 4, 1932 (pictured on p. 90. Poetry Speaks). Jeffers Studies, a journal of research on the poetry of Robinson Jeffers and related topics, is published semi-annually by the Robinson Jeffers Association. Bibliography * Flagons and Apples. Los Angeles: Grafton, 1912. * Californians. New York: Macmillan, 1916. * Tamar and Other Poems. New York: Peter G. Boyle, 1924. * Roan Stallion, Tamar, and Other Poems. New York: Boni and Liveright, 1925. * The Women at Point Sur. New York: Liveright, 1927. * Cawdor and Other Poems. New York: Liveright, 1928. * Dear Judas and Other Poems. New York: Liveright, 1929. * Thurso's Landing and Other Poems. New York: Liveright, 1932. * Give Your Heart to the Hawks and other Poems. New York: Random House, 1933. * Solstice and Other Poems. New York: Random House, 1935. * Such Counsels You Gave To Me and Other Poems. New York: Random House, 1937. * The Selected Poetry of Robinson Jeffers. New York: Random House, 1938. * Be Angry at the Sun. New York: Random House, 1941. * Medea. New York: Random House, 1946. * The Double Axe and Other Poems. New York: Random House, 1948. * Hungerfield and Other Poems. New York: Random House, 1954. * The Beginning and the End and Other Poems. New York: Random House, 1963. * Robinson Jeffers: Selected Poems. New York: Vintage, 1965. * Stones of the Sur. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robinson_Jeffers

William Sydney Porter (September 11, 1862– June 5, 1910), known by his pen name O. Henry, was an American short story writer. His stories are known for their surprise endings. Biography Early life William Sidney Porter was born on September 11, 1862, in Greensboro, North Carolina. He changed the spelling of his middle name to Sydney in 1898. His parents were Dr. Algernon Sidney Porter (1825–88), a physician, and Mary Jane Virginia Swaim Porter (1833–65). William’s parents had married on April 20, 1858. When William was three, his mother died from tuberculosis, and he and his father moved into the home of his paternal grandmother. As a child, Porter was always reading, everything from classics to dime novels; his favorite works were Lane’s translation of One Thousand and One Nights and Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy. Porter graduated from his aunt Evelina Maria Porter’s elementary school in 1876. He then enrolled at the Lindsey Street High School. His aunt continued to tutor him until he was fifteen. In 1879, he started working in his uncle’s drugstore in Greensboro, and on August 30, 1881, at the age of nineteen, Porter was licensed as a pharmacist. At the drugstore, he also showed off his natural artistic talents by sketching the townsfolk. Move to Texas Porter traveled with Dr. James K. Hall to Texas in March 1882, hoping that a change of air would help alleviate a persistent cough he had developed. He took up residence on the sheep ranch of Richard Hall, James’ son, in La Salle County and helped out as a shepherd, ranch hand, cook, and baby-sitter. While on the ranch, he learned bits of Spanish and German from the mix of immigrant ranch hands. He also spent time reading classic literature. Porter’s health did improve. He traveled with Richard to Austin in 1884, where he decided to remain and was welcomed into the home of Richard’s friends, Joseph Harrell and his wife. Porter resided with the Harrells for three years. He went to work briefly for the Morley Brothers Drug Company as a pharmacist. Porter then moved on to work for the Harrell Cigar Store located in the Driskill Hotel. He also began writing as a sideline and wrote many of his early stories in the Harrell house. As a young bachelor, Porter led an active social life in Austin. He was known for his wit, story-telling and musical talents. He played both the guitar and mandolin. He sang in the choir at St. David’s Episcopal Church and became a member of the “Hill City Quartette”, a group of young men who sang at gatherings and serenaded young women of the town. Porter met and began courting Athol Estes, then seventeen years old and from a wealthy family. Historians believe Porter met Athol at the laying of the cornerstone of the Texas State Capitol on March 2, 1885. Her mother objected to the match because Athol was ill, suffering from tuberculosis. On July 1, 1887, Porter eloped with Athol and were married in the parlor of the home of Reverend R. K. Smoot, pastor of the Central Presbyterian Church, where the Estes family attended church. The couple continued to participate in musical and theater groups, and Athol encouraged her husband to pursue his writing. Athol gave birth to a son in 1888, who died hours after birth, and then a daughter, Margaret Worth Porter, in September 1889. Porter’s friend Richard Hall became Texas Land Commissioner and offered Porter a job. Porter started as a draftsman at the Texas General Land Office (GLO) on January 12, 1887 at a salary of $100 a month, drawing maps from surveys and fieldnotes. The salary was enough to support his family, but he continued his contributions to magazines and newspapers. In the GLO building, he began developing characters and plots for such stories as “Georgia’s Ruling” (1900), and “Buried Treasure” (1908). The castle-like building he worked in was even woven into some of his tales such as "Bexar Scrip No. 2692" (1894). His job at the GLO was a political appointment by Hall. Hall ran for governor in the election of 1890 but lost. Porter resigned on January 21, 1891, the day after the new governor, Jim Hogg, was sworn in. The same year, Porter began working at the First National Bank of Austin as a teller and bookkeeper at the same salary he had made at the GLO. The bank was operated informally, and Porter was apparently careless in keeping his books and may have embezzled funds. In 1894, he was accused by the bank of embezzlement and lost his job but was not indicted at the time. He then worked full-time on his humorous weekly called The Rolling Stone, which he started while working at the bank. The Rolling Stone featured satire on life, people and politics and included Porter’s short stories and sketches. Although eventually reaching a top circulation of 1500, The Rolling Stone failed in April 1895, since the paper never provided an adequate income. However, his writing and drawings had caught the attention of the editor at the Houston Post. Porter and his family moved to Houston in 1895, where he started writing for the Post. His salary was only $25 a month, but it rose steadily as his popularity increased. Porter gathered ideas for his column by loitering in hotel lobbies and observing and talking to people there. This was a technique he used throughout his writing career. While he was in Houston, federal auditors audited the First National Bank of Austin and found the embezzlement shortages that led to his firing. A federal indictment followed, and he was arrested on charges of embezzlement. Flight and return Porter’s father-in-law posted bail to keep him out of jail. He was due to stand trial on July 7, 1896, but the day before, as he was changing trains to get to the courthouse, an impulse hit him. He fled, first to New Orleans and later to Honduras, with which the United States had no extradition treaty at that time. William lived in Honduras for only six months, until January 1897. There he became friends with Al Jennings, a notorious train robber, who later wrote a book about their friendship. He holed up in a Trujillo hotel, where he wrote Cabbages and Kings, in which he coined the term “banana republic” to qualify the country, a phrase subsequently used widely to describe a small, unstable tropical nation in Latin America with a narrowly focused, agrarian economy. Porter had sent Athol and Margaret back to Austin to live with Athol’s parents. Unfortunately, Athol became too ill to meet Porter in Honduras as he had planned. When he learned that his wife was dying, Porter returned to Austin in February 1897 and surrendered to the court, pending trial. Athol Estes Porter died from tuberculosis (then known as consumption) on July 25, 1897. Porter had little to say in his own defense at his trial and was found guilty on February 17, 1898 of embezzling $854.08. He was sentenced to five years in prison and imprisoned on March 25, 1898, at the Ohio Penitentiary in Columbus, Ohio. Porter was a licensed pharmacist and was able to work in the prison hospital as the night druggist. He was given his own room in the hospital wing, and there is no record that he actually spent time in the cell block of the prison. He had fourteen stories published under various pseudonyms while he was in prison but was becoming best known as “O. Henry”, a pseudonym that first appeared over the story “Whistling Dick’s Christmas Stocking” in the December 1899 issue of McClure’s Magazine. A friend of his in New Orleans would forward his stories to publishers so that they had no idea that the writer was imprisoned. Porter was released on July 24, 1901, for good behavior after serving three years. He reunited with his daughter Margaret, now age 11, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where Athol’s parents had moved after Porter’s conviction. Margaret was never told that her father had been in prison—just that he had been away on business. Later life and death Porter’s most prolific writing period started in 1902, when he moved to New York City to be near his publishers. While there, he wrote 381 short stories. He wrote a story a week for over a year for the New York World Sunday Magazine. His wit, characterization, and plot twists were adored by his readers but often panned by critics. Porter married again in 1907 to childhood sweetheart Sarah (Sallie) Lindsey Coleman, whom he met again after revisiting his native state of North Carolina. Sarah Lindsey Coleman was herself a writer and wrote a romanticized and fictionalized version of their correspondence and courtship in her novella Wind of Destiny. Porter was a heavy drinker, and by 1908, his markedly deteriorating health affected his writing. In 1909, Sarah left him, and he died on June 5, 1910, of cirrhosis of the liver, complications of diabetes, and an enlarged heart. After funeral services in New York City, he was buried in the Riverside Cemetery in Asheville, North Carolina. His daughter, Margaret Worth Porter, had a short writing career from 1913 to 1916. She married cartoonist Oscar Cesare of New York in 1916; they were divorced four years later. She died of tuberculosis in 1927 and is buried next to her father. Stories O. Henry’s stories frequently have surprise endings. In his day he was called the American answer to Guy de Maupassant. While both authors wrote plot twist endings, O. Henry’s stories were considerably more playful. His stories are also known for witty narration. Most of O. Henry’s stories are set in his own time, the early 20th century. Many take place in New York City and deal for the most part with ordinary people: policemen, waitresses, etc. O. Henry’s work is wide-ranging, and his characters can be found roaming the cattle-lands of Texas, exploring the art of the con-man, or investigating the tensions of class and wealth in turn-of-the-century New York. O. Henry had an inimitable hand for isolating some element of society and describing it with an incredible economy and grace of language. Some of his best and least-known work is contained in Cabbages and Kings, a series of stories each of which explores some individual aspect of life in a paralytically sleepy Central American town, while advancing some aspect of the larger plot and relating back one to another. Cabbages and Kings was his first collection of stories, followed by The Four Million. The second collection opens with a reference to Ward McAllister’s “assertion that there were only 'Four Hundred’ people in New York City who were really worth noticing. But a wiser man has arisen—the census taker—and his larger estimate of human interest has been preferred in marking out the field of these little stories of the ‘Four Million.’” To O. Henry, everyone in New York counted. He had an obvious affection for the city, which he called “Bagdad-on-the-Subway”, and many of his stories are set there—while others are set in small towns or in other cities. His final work was “Dream”, a short story intended for the magazine The Cosmopolitan but left incomplete at the time of his death. Among his most famous stories are: “The Gift of the Magi” about a young couple, Jim and Della, who are short of money but desperately want to buy each other Christmas gifts. Unbeknownst to Jim, Della sells her most valuable possession, her beautiful hair, in order to buy a platinum fob chain for Jim’s watch; while unbeknownst to Della, Jim sells his own most valuable possession, his watch, to buy jeweled combs for Della’s hair. The essential premise of this story has been copied, re-worked, parodied, and otherwise re-told countless times in the century since it was written. “The Ransom of Red Chief”, in which two men kidnap a boy of ten. The boy turns out to be so bratty and obnoxious that the desperate men ultimately pay the boy’s father $250 to take him back. “The Cop and the Anthem” about a New York City hobo named Soapy, who sets out to get arrested so that he can be a guest of the city jail instead of sleeping out in the cold winter. Despite efforts at petty theft, vandalism, disorderly conduct, and “mashing” with a young prostitute, Soapy fails to draw the attention of the police. Disconsolate, he pauses in front of a church, where an organ anthem inspires him to clean up his life—and is ironically charged for loitering and sentenced to three months in prison. “A Retrieved Reformation”, which tells the tale of safecracker Jimmy Valentine, recently freed from prison. He goes to a town bank to case it before he robs it. As he walks to the door, he catches the eye of the banker’s beautiful daughter. They immediately fall in love and Valentine decides to give up his criminal career. He moves into the town, taking up the identity of Ralph Spencer, a shoemaker. Just as he is about to leave to deliver his specialized tools to an old associate, a lawman who recognizes him arrives at the bank. Jimmy and his fiancée and her family are at the bank, inspecting a new safe when a child accidentally gets locked inside the airtight vault. Knowing it will seal his fate, Valentine opens the safe to rescue the child. However, much to Valentine’s surprise, the lawman denies recognizing him and lets him go. “The Duplicity of Hargraves”. A short story about a nearly destitute father and daughter’s trip to Washington, D.C. “The Caballero’s Way”, in which Porter’s most famous character, the Cisco Kid, is introduced. It was first published in 1907 in the July issue of Everybody’s Magazine and collected in the book Heart of the West that same year. In later film and TV depictions, the Kid would be portrayed as a dashing adventurer, perhaps skirting the edges of the law, but primarily on the side of the angels. In the original short story, the only story by Porter to feature the character, the Kid is a murderous, ruthless border desperado, whose trail is dogged by a heroic Texas Ranger. The twist ending is, unusually for Porter, tragic. Pen name Porter used a number of pen names (including “O. Henry” or “Olivier Henry”) in the early part of his writing career; other names included S.H. Peters, James L. Bliss, T.B. Dowd, and Howard Clark. Nevertheless, the name “O. Henry” seemed to garner the most attention from editors and the public, and was used exclusively by Porter for his writing by about 1902. He gave various explanations for the origin of his pen name. In 1909 he gave an interview to The New York Times, in which he gave an account of it: It was during these New Orleans days that I adopted my pen name of O. Henry. I said to a friend: “I’m going to send out some stuff. I don’t know if it amounts to much, so I want to get a literary alias. Help me pick out a good one.” He suggested that we get a newspaper and pick a name from the first list of notables that we found in it. In the society columns we found the account of a fashionable ball. “Here we have our notables,” said he. We looked down the list and my eye lighted on the name Henry, “That’ll do for a last name,” said I. “Now for a first name. I want something short. None of your three-syllable names for me.” “Why don’t you use a plain initial letter, then?” asked my friend. “Good,” said I, “O is about the easiest letter written, and O it is.” A newspaper once wrote and asked me what the O stands for. I replied, “O stands for Olivier, the French for Oliver.” And several of my stories accordingly appeared in that paper under the name Olivier Henry. William Trevor writes in the introduction to The World of O. Henry: Roads of Destiny and Other Stories (Hodder & Stoughton, 1973) that “there was a prison guard named Orrin Henry” in the Ohio State Penitentiary “whom William Sydney Porter... immortalised as O. Henry”. According to J. F. Clarke, it is from the name of the French pharmacist Etienne Ossian Henry, whose name is in the U. S. Dispensary which Porter used working in the prison pharmacy. Writer and scholar Guy Davenport offers his own hypothesis: “The pseudonym that he began to write under in prison is constructed from the first two letters of Ohio and the second and last two of penitentiary.” Legacy The O. Henry Award is a prestigious annual prize named after Porter and given to outstanding short stories. A film was made in 1952 featuring five stories, called O. Henry’s Full House. The episode garnering the most critical acclaim was “The Cop and the Anthem” starring Charles Laughton and Marilyn Monroe. The other stories are “The Clarion Call”, “The Last Leaf”, “The Ransom of Red Chief” (starring Fred Allen and Oscar Levant), and “The Gift of the Magi”. The O. Henry House and O. Henry Hall, both in Austin, Texas, are named for him. O. Henry Hall, now owned by the Texas State University System, previously served as the federal courthouse in which O. Henry was convicted of embezzlement. Porter has elementary schools named for him in Greensboro, North Carolina (William Sydney Porter Elementary) and Garland, Texas (O. Henry Elementary), as well as a middle school in Austin, Texas (O. Henry Middle School). The O. Henry Hotel in Greensboro is also named for Porter, as is US 29 which is O. Henry Boulevard. In 1962, the Soviet Postal Service issued a stamp commemorating O. Henry’s 100th birthday. On September 11, 2012, the U.S. Postal Service issued a stamp commemorating the 150th anniversary of O. Henry’s birth. On November 23, 2011, Barack Obama quoted O. Henry while granting pardons to two turkeys named “Liberty” and “Peace”. In response, political science professor P. S. Ruckman, Jr., and Texas attorney Scott Henson filed a formal application for a posthumous pardon in September 2012, the same month that the U.S. Postal Service issued its O. Henry stamp. Previous attempts were made to obtain such a pardon for Porter in the administrations of Woodrow Wilson, Dwight Eisenhower, and Ronald Reagan, but no one had ever bothered to file a formal application. Ruckman and Henson argued that Porter deserved a pardon because (1) he was a law-abiding citizen prior to his conviction; (2) his offense was minor; (3) he had an exemplary prison record; (4) his post-prison life clearly indicated rehabilitation; (5) he would have been an excellent candidate for clemency in his time, had he but applied for pardon; (6) by today’s standards, he remains an excellent candidate for clemency; and (7) his pardon would be a well-deserved symbolic gesture and more. O. Henry’s love of language inspired the O. Henry Pun-Off, an annual spoken word competition began in 1978 that takes place at the O. Henry House. Bibliography * Cabbages and Kings (1904) * The Four Million (1906), short stories * The Trimmed Lamp (1907), short stories: “The Trimmed Lamp”, “A Madison Square Arabian Night”, “The Rubaiyat of a Scotch Highball”, “The Pendulum”, “Two Thanksgiving Day Gentlemen”, “The Assessor of Success”, “The Buyer from Cactus City”, “The Badge of Policeman O’Roon”, “Brickdust Row”, “The Making of a New Yorker”, “Vanity and Some Sables”, “The Social Triangle”, “The Purple Dress”, "The Foreign Policy of Company 99", “The Lost Blend”, “A Harlem Tragedy”, “'The Guilty Party’”, “According to Their Lights”, “A Midsummer Knight’s Dream”, “The Last Leaf”, “The Count and the Wedding Guest”, “The Country of Elusion”, “The Ferry of Unfulfilment”, “The Tale of a Tainted Tenner”, “Elsie in New York” * Heart of the West (1907), short stories: “Hearts and Crosses”, “The Ransom of Mack”, “Telemachus, Friend”, “The Handbook of Hymen”, “The Pimienta Pancakes”, “Seats of the Haughty”, “Hygeia at the Solito”, “An Afternoon Miracle”, “The Higher Abdication”, "Cupid à la Carte", “The Caballero’s Way”, “The Sphinx Apple”, “The Missing Chord”, “A Call Loan”, “The Princess and the Puma”, “The Indian Summer of Dry Valley Johnson”, “Christmas by Injunction”, “A Chaparral Prince”, “The Reformation of Calliope” * The Voice of the City (1908), short stories: “The Voice of the City”, “The Complete Life of John Hopkins”, “A Lickpenny Lover”, “Dougherty’s Eye-opener”, “'Little Speck in Garnered Fruit’”, “The Harbinger”, “While the Auto Waits”, “A Comedy in Rubber”, “One Thousand Dollars”, “The Defeat of the City”, “The Shocks of Doom”, “The Plutonian Fire”, “Nemesis and the Candy Man”, “Squaring the Circle”, “Roses, Ruses and Romance”, “The City of Dreadful Night”, “The Easter of the Soul”, “The Fool-killer”, “Transients in Arcadia”, “The Rathskeller and the Rose”, “The Clarion Call”, “Extradited from Bohemia”, “A Philistine in Bohemia”, “From Each According to His Ability”, “The Memento” * The Gentle Grafter (1908), short stories: “The Octopus Marooned”, “Jeff Peters as a Personal Magnet”, “Modern Rural Sports”, “The Chair of Philanthromathematics”, “The Hand That Riles the World”, “The Exact Science of Matrimony”, “A Midsummer Masquerade”, “Shearing the Wolf”, “Innocents of Broadway”, “Conscience in Art”, “The Man Higher Up”, “Tempered Wind”, “Hostages to Momus”, “The Ethics of Pig” * Roads of Destiny (1909), short stories: “Roads of Destiny”, “The Guardian of the Accolade”, “The Discounters of Money”, “The Enchanted Profile”, “Next to Reading Matter”, “Art and the Bronco”, "Phœbe", “A Double-dyed Deceiver”, “The Passing of Black Eagle”, “A Retrieved Reformation”, “Cherchez la Femme”, “Friends in San Rosario”, “The Fourth in Salvador”, “The Emancipation of Billy”, “The Enchanted Kiss”, “A Departmental Case”, “The Renaissance at Charleroi”, “On Behalf of the Management”, “Whistling Dick’s Christmas Stocking”, “The Halberdier of the Little Rheinschloss”, “Two Renegades”, “The Lonesome Road” * Options (1909), short stories: “'The Rose of Dixie’”, “The Third Ingredient”, “The Hiding of Black Bill”, “Schools and Schools”, “Thimble, Thimble”, “Supply and Demand”, “Buried Treasure”, “To Him Who Waits”, “He Also Serves”, “The Moment of Victory”, “The Head-hunter”, “No Story”, “The Higher Pragmatism”, “Best-seller”, “Rus in Urbe”, “A Poor Rule” * Strictly Business (1910), short stories: “Strictly Business”, “The Gold That Glittered”, “Babes in the Jungle”, “The Day Resurgent”, “The Fifth Wheel”, “The Poet and the Peasant”, “The Robe of Peace”, “The Girl and the Graft”, “The Call of the Tame”, “The Unknown Quantity”, “The Thing’s the Play”, “A Ramble in Aphasia”, “A Municipal Report”, “Psyche and the Pskyscraper”, “A Bird of Bagdad”, “Compliments of the Season”, “A Night in New Arabia”, “The Girl and the Habit”, “Proof of the Pudding”, “Past One at Rooney’s”, “The Venturers”, “The Duel”, “'What You Want’” * Whirligigs (1910), short stories: “The World and the Door”, “The Theory and the Hound”, “The Hypotheses of Failure”, “Calloway’s Code”, “A Matter of Mean Elevation”, “Girl”, “Sociology in Serge and Straw”, “The Ransom of Red Chief”, “The Marry Month of May”, “A Technical Error”, “Suite Homes and Their Romance”, “The Whirligig of Life”, “A Sacrifice Hit”, “The Roads We Take”, “A Blackjack Bargainer, ”The Song and the Sergeant", “One Dollar’s Worth”, “A Newspaper Story”, “Tommy’s Burglar”, “A Chaparral Christmas Gift”, “A Little Local Colour”, “Georgia’s Ruling”, “Blind Man’s Holiday”, “Madame Bo-Peep of the Ranches” * Sixes and Sevens (1911), short stories: “The Last of the Troubadours”, “The Sleuths”, “Witches’ Loaves”, “The Pride of the Cities”, “Holding Up a Train”, “Ulysses and the Dogman”, “The Champion of the Weather”, “Makes the Whole World Kin”, “At Arms with Morpheus”, “A Ghost of a Chance”, “Jimmy Hayes and Muriel”, “The Door of Unrest”, “The Duplicity of Hargraves”, “Let Me Feel Your Pulse”, “October and June”, “The Church with an Overshot-Wheel”, “New York by Camp Fire Light”, “The Adventures of Shamrock Jolnes”, “The Lady Higher Up”, “The Greater Coney”, “Law and Order”, “Transformation of Martin Burney”, “The Caliph and the Cad”, “The Diamond of Kali”, “The Day We Celebrate” * Rolling Stones (1912), short stories: “The Dream”, “A Ruler of Men”, “The Atavism of John Tom Little Bear”, “Helping the Other Fellow”, “The Marionettes”, “The Marquis and Miss Sally”, “A Fog in Santone”, “The Friendly Call”, “A Dinner at———”, “Sound and Fury”, “Tictocq”, “Tracked to Doom”, “A Snapshot at the President”, “An Unfinished Christmas Story”, “The Unprofitable Servant”, “Aristocracy Versus Hash”, “The Prisoner of Zembla”, “A Strange Story”, “Fickle Fortune, or How Gladys Hustled”, “An Apology”, “Lord Oakhurst’s Curse”, "Bexar Scrip No. 2692” * Waifs and Strays (1917), short stories References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/O._Henry

Herman Melville (August 1, 1819– September 28, 1891) was an American novelist, short story writer, and poet of the American Renaissance period best known for Typee (1846), a romantic account of his experiences in Polynesian life, and his whaling novel Moby-Dick (1851). His work was almost forgotten during his last thirty years. His writing draws on his experience at sea as a common sailor, exploration of literature and philosophy, and engagement in the contradictions of American society in a period of rapid change. He developed a complex, baroque style: the vocabulary is rich and original, a strong sense of rhythm infuses the elaborate sentences, the imagery is often mystical or ironic, and the abundance of allusion extends to Scripture, myth, philosophy, literature, and the visual arts.

Eugene Field, Sr. (September 2, 1850 – November 4, 1895) was an American writer, best known for his children's poetry and humorous essays. Field was born in St. Louis, Missouri where today his boyhood home is open to the public as The Eugene Field House and St. Louis Toy Museum. After the death of his mother in 1856, he was raised by a cousin, Mary Field French, in Amherst, Massachusetts.

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835– April 21, 1910), better known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, entrepreneur, publisher, and lecturer. Among his novels are The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) and its sequel, the Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1885), the latter often called “The Great American Novel”.

Amy Lawrence Lowell (February 9, 1874 – May 12, 1925) was an American poet of the imagist school from Brookline, Massachusetts, who posthumously won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1926. Amy was born into Brookline’s Lowell family, sister to astronomer Percival Lowell and Harvard president Abbott Lawrence Lowell. She never attended college because her family did not consider it proper for a woman to do so. She compensated for this lack with avid reading and near-obsessive book collecting. She lived as a socialite and travelled widely, turning to poetry in 1902 (age 28) after being inspired by a performance of Eleonora Duse in Europe.

#Americans #Lesbian #PulitzerPrize #Women

Dorothy Parker (August 22, 1893 – June 7, 1967) was an American poet, short story writer, critic and satirist, best known for her wit, wisecracks, and eye for 20th-century urban foibles. From a conflicted and unhappy childhood, Parker rose to acclaim, both for her literary output in such venues as The New Yorker and as a founding member of the Algonquin Round Table. Following the breakup of the circle, Parker traveled to Hollywood to pursue screenwriting. Her successes there, including two Academy Award nominations, were curtailed as her involvement in left-wing politics led to a place on the Hollywood blacklist. Dismissive of her own talents, she deplored her reputation as a “wisecracker”. Nevertheless, her literary output and reputation for her sharp wit have endured.

Edna St. Vincent Millay (February 22, 1892 – October 19, 1950) was an American poet and playwright. She received the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1923, the third woman to win the award for poetry, and was also known for her feminist activism. She used the pseudonym Nancy Boyd for her prose work. The poet Richard Wilbur asserted, "She wrote some of the best sonnets of the century."

#Americans #PulitzerPrize #Women #XXCentury

George Henry Boker (October 6, 1823 – January 2, 1890) was an American poet, playwright, and diplomat. Boker was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. His father was Charles S. Boker, a wealthy banker, whose financial expertness weathered the Girard National Bank through the panic years of 1838-40, and whose honour, impugned after his 1857 death, was defended many years later by his son in “The Book of the Dead.” Charles Boker was also a director of the Mechanics National Bank.

Maya Angelou (born Marguerite Ann Johnson; April 4, 1928 – May 28, 2014) was an American author and poet. She published seven autobiographies, three books of essays, and several books of poetry, and is credited with a list of plays, movies, and television shows spanning more than fifty years. She received dozens of awards and over thirty honorary doctoral degrees. Angelou is best known for her series of seven autobiographies, which focus on her childhood and early adult experiences. The first, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings (1969), tells of her life up to the age of seventeen, and brought her international recognition and acclaim. Angelou's long list of occupations has included pimp, prostitute, night-club dancer and performer, cast-member of the musical Porgy and Bess, coordinator for Martin Luther King, Jr.'s Southern Christian Leadership Conference, author, journalist in Egypt and Ghana during the days of decolonization, and actor, writer, director, and producer of plays, movies, and public television programs.

Celia Laighton Thaxter (June 29, 1835 – August 25, 1894) was an American writer of poetry and stories. She was born in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Thaxter grew up in the Isles of Shoals, first on White Island, where her father, Thomas Laighton, was a lighthouse keeper, and then on Smuttynose and Appledore Islands. When she was sixteen, she married Levi Thaxter and moved to the mainland, residing first in Watertown, Massachusetts at a property his father owned. Celia died suddenly while on Appledore Island. She was buried not far from her cottage, which unfortunately burned in the 1914 fire that destroyed The Appledore House hotel.

Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803 – April 27, 1882), who went by his middle name Waldo, was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher, abolitionist, and poet who led the Transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century. He was seen as a champion of individualism and critical thinking, as well as a prescient critic of the countervailing pressures of society and conformity. Friedrich Nietzsche thought he was “the most gifted of the Americans,” and Walt Whitman called him his “master”.

Franklin Pierce Adams (November 15, 1881 – March 23, 1960) was an American columnist, well known by his initials F.P.A., and wit, best known for his newspaper column, “The Conning Tower”, and his appearances as a regular panelist on radio’s Information Please. A prolific writer of light verse, he was a member of the Algonquin Round Table of the 1920s and 1930s. Adams was born Franklin Leopold Adams to Moses and Clara Schlossberg Adams in Chicago on November 15, 1881. He changed his middle name to “Pierce” when he had a Jewish confirmation ceremony at age 13. Adams graduated from the Armour Scientific Academy (now Illinois Institute of Technology) in 1899, attended the University of Michigan for one year and worked in insurance for three years.

Thomas Stearns Eliot OM (26 September 1888– 4 January 1965) was a British essayist, publisher, playwright, literary and social critic, and “one of the twentieth century’s major poets”. He moved from his native United States to England in 1914 at the age of 25, settling, working, and marrying there. He was eventually naturalised as a British subject in 1927 at the age of 39, renouncing his American citizenship. Eliot attracted widespread attention for his poem “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” (1915), which was seen as a masterpiece of the Modernist movement. It was followed by some of the best-known poems in the English language, including The Waste Land (1922), “The Hollow Men” (1925), “Ash Wednesday” (1930), and Four Quartets (1943). He was also known for his seven plays, particularly Murder in the Cathedral (1935). He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1948, “for his outstanding, pioneer contribution to present-day poetry”.

Edwin Arlington Robinson (December 22, 1869—April 6, 1935) was an American poet who won three Pulitzer Prizes for his work. He was born in Head Tide, Lincoln County, Maine but his family moved to Gardiner, Maine in 1871. He described his childhood in Maine as “stark and unhappy”: His parents (who had wanted a girl) did not name him until he was six months old, when they visited a holiday resort—whereupon, other vacationers decided that he should have a name and selected a man from Arlington, Massachusetts to draw a name out of a hat. Throughout his life, he not only hated his given name, but also his family’s habit of calling him “Win.” As an adult, he always used the signature “E. A.”

Nicholas Vachel Lindsay (November 10, 1879 – December 5, 1931) was an American poet. He is considered a founder of modern singing poetry, as he referred to it, in which verses are meant to be sung or chanted. Crushed by financial worry and in failing health from his six-month road trip, Lindsay sank into depression. While in New York in 1905 Lindsay turned to poetry in earnest. He tried to sell his poems on the streets. Self-printing his poems, he began to barter a pamphlet titled “Rhymes To Be Traded For Bread”, which he traded for food as a self-perceived modern version of a medieval troubadour. On December 5, 1931, he committed suicide by drinking a bottle of Lysol. His last words were: “They tried to get me; I got them first!”

#Americans #Suicide #XIXCentury #XXCentury

Henry David Thoreau (July 12, 1817– May 6, 1862) was an American author, poet, philosopher, abolitionist, naturalist, tax resister, development critic, surveyor, and historian. A leading transcendentalist, Thoreau is best known for his book Walden, a reflection upon simple living in natural surroundings, and his essay Resistance to Civil Government (also known as Civil Disobedience), an argument for disobedience to an unjust state. He was a lifelong abolitionist, delivering lectures that attacked the Fugitive Slave Law while praising the writings of Wendell Phillips and defending abolitionist John Brown. Thoreau’s philosophy of civil disobedience later influenced the political thoughts and actions of such notable figures as Leo Tolstoy, Mahatma Gandhi, and Martin Luther King, Jr.

James Mercer Langston Hughes (February 1, 1902 – May 22, 1967) was an American poet, social activist, novelist, playwright, and columnist. He was one of the earliest innovators of the then-new literary art form jazz poetry. Hughes is best known for his work during the Harlem Renaissance. He famously wrote about the period that “the negro was in vogue” which was later paraphrased as “when Harlem was in vogue”.

Elizabeth Bishop (February 8, 1911 – October 6, 1979) was an American poet, short-story writer, and recipient of the 1976 Neustadt International Prize for Literature. She was the Poet Laureate of the United States from 1949 to 1950, the Pulitzer Prize winner for Poetry in 1956 and the National Book Award winner in 1970.

#Americans #PulitzerPrize #Women

Erica Jong (née Mann; born March 26, 1942) is an American novelist and poet, known particularly for her 1973 novel Fear of Flying. The book became famously controversial for its attitudes towards female sexuality and figured prominently in the development of second-wave feminism. According to Washington Post, it has sold more than 20 million copies worldwide. Born in New York, she was the second of three daughters of Seymore Mann and Eda Mirsky. Attended New York’s Public High School of Music and Art in the 1950’s where she developed her passion for art and writing. As a student at Barnard College, she edited the Barnard Literary Magazine and created poetry programs for the Columbia University campus radio station.

Wallace Stevens was born in Reading, Pennsylvania, on October 2, 1879. He attended Harvard University as an undergraduate from 1897 to 1900. He planned to travel to Paris as a writer, but after a working briefly as a reporter for the New York Herald Times, he decided to study law. He graduated with a degree from New York Law School in 1903 and was admitted to the U.S. Bar in 1904. He practised law in New York City until 1916. Though he had serious determination to become a successful lawyer, Stevens had several friends among the New York writers and painters in Greenwich Village, including the poets William Carlos Williams, Marianne Moore, and E. E. Cummings. In 1914, under the pseudonym "Peter Parasol," he sent a group of poems under the title "Phases" to Harriet Monroe for a war poem competition for Poetry magazine. Stevens did not win the prize, but was published by Monroe in November of that year. Stevens moved to Connecticut in 1916, having found employment at the Hartford Accident and Indemnity Co., of which he became vice president in 1934. He had began to establish an identity for himself outside the world of law and business, however, and his first book of poems, Harmonium, published in 1923, exhibited the influence of both the English Romantics and the French symbolists, an inclination to aesthetic philosophy, and a wholly original style and sensibility: exotic, whimsical, infused with the light and color of an Impressionist painting. For the next several years, Stevens focused on his business life. He began to publish new poems in 1930, however, and in the following year, Knopf published an second edition of Harmonium, which included fourteen new poems and left out three of the decidedly weaker ones. More than any other modern poet, Stevens was concerned with the transformative power of the imagination. Composing poems on his way to and from the office and in the evenings, Stevens continued to spend his days behind a desk at the office, and led a quiet, uneventful life. Though now considered one of the major American poets of the century, he did not receive widespread recognition until the publication of his Collected Poems, just a year before his death. His major works include Ideas of Order (1935), The Man With the Blue Guitar (1937), Notes Towards a Supreme Fiction (1942), and a collection of essays on poetry, The Necessary Angel (1951). Stevens died in Hartford in 1955. Poetry Harmonium (1923) Ideas of Order (1935) Owl's Clover (1936) The Man With the Blue Guitar (1937) Notes Towards a Supreme Fiction (1942) Parts of a World (1942) Esthétique du Mal (1945) Three Academic Pieces (1947) Transport to Summer (1947) Primitive Like an Orb (1948) Auroras of Autumn (1950) Collected Poems (1954) Opus Posthumous (1957) The Palm at the End of the Mind (1967) Prose The Necessary Angel (1951) Plays Three Travellers Watch the Sunrise (1916) Carlos Among the Candles (1917) References Poets.org — http://www.poets.org/poet.php/prmPID/124

#Americans Modern

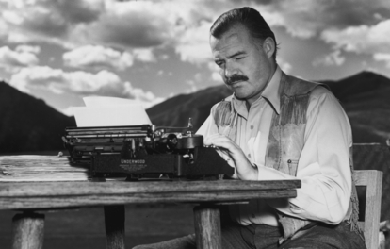

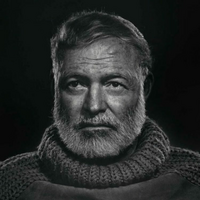

Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961) was one of the most significant American authors of the Twentieth century . His novels and short fictions have left an indelible mark on the literary production of the United States and the world. Although most often remembered for his economical and understated fiction, he was also a noted journalist. In 1954, Ernest Hemingway was awarded the Novel Prize in Literature. Hemingway is also known for his heroic, adventurous and often stereotypically “manly” public persona. The myth he cultivated of himself as a man of action aided the important Modernist reading of many of his works.

Conrad Potter Aiken (August 5, 1889– August 17, 1973) was an American writer, whose work includes poetry, short stories, novels, a play, and an autobiography. Aiken was the son of wealthy, socially prominent New Englanders, William Ford and Anna (Potter) Aiken, who had moved to Savannah, Georgia, where his father became a respected physician and brain surgeon. Then something happened for which, as Aiken later said, no one could ever find a reason. Without warning or apparent cause, his father became increasingly irascible, unpredictable, and violent. Finally, early in the morning of February 27, 1901, he murdered his wife and shot himself. According to his own writings, Aiken (who was eleven years old) heard the gunshots and discovered the bodies. He was then raised by his great aunt in Massachusetts and was educated at private schools and at Middlesex School in Concord, Massachusetts, then at Harvard University where he edited the Advocate with T. S. Eliot, who became a lifelong friend and associate.

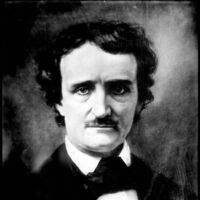

Edgar Allan Poe (born Edgar Poe, January 19, 1809 – October 7, 1849) was an American author, poet, editor and literary critic, considered part of the American Romantic Movement. Best known for his tales of mystery and the macabre, Poe was one of the earliest American practitioners of the short story and is considered the inventor of the detective fiction genre. He is further credited with contributing to the emerging genre of science fiction. He was the first well-known American writer to try to earn a living through writing alone, resulting in a financially difficult life and career. He was born as Edgar Poe in Boston, Massachusetts; he was orphaned young when his mother died shortly after his father abandoned the family. Poe was taken in by John and Frances Allan, of Richmond, Virginia, but they never formally adopted him. He attended the University of Virginia for one semester but left due to lack of money. After enlisting in the Army and later failing as an officer's cadet at West Point, Poe parted ways with the Allans. His publishing career began humbly, with an anonymous collection of poems, Tamerlane and Other Poems (1827), credited only to “a Bostonian”.

James Russell Lowell (February 22, 1819– August 12, 1891) was an American Romantic poet, critic, editor, and diplomat. He is associated with the Fireside Poets, a group of New England writers who were among the first American poets who rivaled the popularity of British poets. These poets usually used conventional forms and meters in their poetry, making them suitable for families entertaining at their fireside. Lowell graduated from Harvard College in 1838, despite his reputation as a troublemaker, and went on to earn a law degree from Harvard Law School. He published his first collection of poetry in 1841 and married Maria White in 1844. He and his wife had several children, though only one survived past childhood. The couple soon became involved in the movement to abolish slavery, with Lowell using poetry to express his anti-slavery views and taking a job in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, as the editor of an abolitionist newspaper. After moving back to Cambridge, Lowell was one of the founders of a journal called The Pioneer, which lasted only three issues. He gained notoriety in 1848 with the publication of A Fable for Critics, a book-length poem satirizing contemporary critics and poets. The same year, he published The Biglow Papers, which increased his fame.