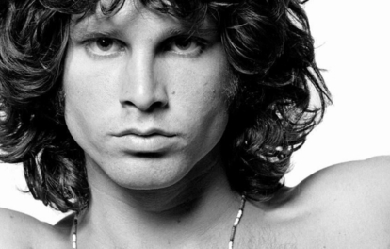

James Douglas “Jim” Morrison (December 8, 1943– July 3, 1971) was an American singer, songwriter, and poet, best remembered as the lead singer of The Doors. As a result of his lyrics, wild personality, performances, and the dramatic circumstances surrounding his life and death, Morrison is regarded by critics and fans as one of the most iconic and influential frontmen in rock music history. In the later part of the 20th century, his fame endured as one of the popular culture’s most rebellious and oft-displayed icons, representing the generation gap and youth counterculture. He was also well known for improvising spoken word poetry passages while the band played live. Morrison was ranked number 47 on Rolling Stone’s list of the "100 Greatest Singers of All Time", and number 22 on Classic Rock magazine’s "50 Greatest Singers In Rock". Ray Manzarek, who co-founded the Doors with him, said Morrison “embodied hippie counterculture rebellion”. Morrison was sometimes referred to by other nicknames, such as “Lizard King” and “King of Orgasmic Rock”. Morrison developed an alcohol dependency during the 1960s, which at times affected his performances on stage. He died at the age of 27 in Paris, possibly from an accidental heroin overdose. As no autopsy was performed, the exact cause of Morrison’s death is still disputed. Morrison is interred at Père Lachaise Cemetery in eastern Paris. Early years James Douglas Morrison was born in Melbourne, Florida, the son of Clara Virginia (née Clarke) and Rear Admiral George Stephen Morrison, USN, who commanded US naval forces during the Gulf of Tonkin incident, which provided the pretext for the US invasion of South Vietnam in 1965. Morrison had a sister, Anne Robin, who was born in 1947 in Albuquerque, New Mexico; and a brother, Andrew Lee Morrison, who was born in 1948 in Los Altos, California. His ancestors were Scottish, Irish, and English. In 1947, Morrison, then four years old, allegedly witnessed a car accident in the desert, in which a family of Native Americans were injured and possibly killed. He referred to this incident in the Doors’ song “Peace Frog” on the 1970 album Morrison Hotel, as well as in the spoken word performances “Dawn’s Highway” and “Ghost Song” on the posthumous 1978 album An American Prayer. Morrison believed this incident to be the most formative event of his life, and made repeated references to it in the imagery in his songs, poems, and interviews. His family does not recall this incident happening in the way he told it. According to the Morrison biography No One Here Gets Out Alive, Morrison’s family did drive past a car accident on an Indian reservation when he was a child, and he was very upset by it. The book The Doors, written by the remaining members of the Doors, explains how different Morrison’s account of the incident was from that of his father. This book quotes his father as saying, "We went by several Indians. It did make an impression on him [the young James]. He always thought about that crying Indian." This is contrasted sharply with Morrison’s tale of “Indians scattered all over the highway, bleeding to death.” In the same book, his sister is quoted as saying, “He enjoyed telling that story and exaggerating it. He said he saw a dead Indian by the side of the road, and I don’t even know if that’s true.” Raised a military brat, Morrison’s family moved often. He spent part of his childhood in San Diego. He completed third grade at a Fairfax County Elementary School Fairfax County, Virginia. His father was stationed at NAS Kingsville in 1952, he attended Charles H. Flato Elementary School in Kingsville, Texas. He continued at St. John’s Methodist School in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and then Longfellow School Sixth Grade Graduation Program from San Diego, California. In 1957, Morrison attended Alameda High School in Alameda, California. He graduated from George Washington High School, now George Washington Middle School, in Alexandria, Virginia in June 1961. Cass Elliot also attended high school there, that same year. Morrison read widely and voraciously—being particularly inspired by the writings of philosophers and poets. He was influenced by Friedrich Nietzsche, whose views on aesthetics, morality, and the Apollonian and Dionysian duality would appear in his conversation, poetry and songs. He read Plutarch’s “Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans”. He read the works of the French Symbolist poet Arthur Rimbaud, whose style would later influence the form of Morrison’s short prose poems. He was also influenced by William S. Burroughs, Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Charles Baudelaire, Molière, Franz Kafka, Honoré de Balzac and Jean Cocteau, along with most of the French existentialist philosophers. His senior-year English teacher said, “Jim read as much and probably more than any student in class, but everything he read was so offbeat I had another teacher (who was going to the Library of Congress) check to see if the books Jim was reporting on actually existed. I suspected he was making them up, as they were English books on sixteenth– and seventeenth-century demonology. I’d never heard of them, but they existed, and I’m convinced from the paper he wrote that he read them, and the Library of Congress would’ve been the only source.” Morrison went to live with his paternal grandparents in Clearwater, Florida, where he attended classes at St. Petersburg College (then known as a junior college). In 1962, he transferred to Florida State University (FSU) in Tallahassee, where he appeared in a school recruitment film. While attending FSU, Morrison was arrested for a prank following a home football game. In January 1964, Morrison moved to Los Angeles to attend the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). Shortly thereafter on August 2, 1964, Morrison’s father, George Stephen Morrison, commanded a carrier division of the United States fleet during the Gulf of Tonkin Incident, which resulted in the United States’ rapid escalation of the Vietnam War. At UCLA, Morrison enrolled in Jack Hirschman’s class on Antonin Artaud in the Comparative Literature program within the UCLA English Department. Artaud’s brand of surrealist theatre had a profound impact on Morrison’s dark poetic sensibility of cinematic theatricality. Morrison completed his undergraduate degree at UCLA’s film school within the Theater Arts department of the College of Fine Arts in 1965. At the time of graduation ceremony, he went to Venice, and his diploma was mailed to his mother at Coronado. He made several short films while attending UCLA. First Love, the first of these films, made with Morrison’s classmate and roommate Max Schwartz, was released to the public when it appeared in a documentary about the film Obscura. During these years, while living in Venice Beach, he became friends with writers at the Los Angeles Free Press, for which he advocated until his death in 1971. He conducted a lengthy and in-depth interview with Bob Chorush and Andy Kent, both working for the Free Press at the time (approximately December 6–8, 1970), and was planning on visiting the headquarters of the busy newspaper shortly before leaving for Paris. The Doors In the summer of 1965, after graduating with a bachelor’s degree from the UCLA film school, Morrison led a bohemian lifestyle in Venice Beach. Living on the rooftop of a building inhabited by his old UCLA cinematography friend, Dennis Jakobs, he wrote the lyrics of many of the early songs the Doors would later perform live and record on albums, the most notable being “Moonlight Drive” and “Hello, I Love You”. According to Jakobs, he lived on canned beans and LSD for several months. Morrison and fellow UCLA student, Ray Manzarek, were the first two members of the Doors, forming the group during that summer. They had met months earlier as cinematography students. The now-legendary story claims that Manzarek was lying on the beach at Venice one day, where he accidentally encountered Morrison. He was impressed with Morrison’s poetic lyrics, claiming that they were “rock group” material. Subsequently, guitarist Robby Krieger and drummer John Densmore joined. Krieger auditioned at Densmore’s recommendation and was then added to the lineup. All three musicians shared a common interest in the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi’s meditation practices at the time, attending scheduled classes, but Morrison was not involved in this series of classes, claiming later that he “did not meditate.” The Doors took their name from the title of Aldous Huxley’s book The Doors of Perception (a reference to the unlocking of doors of perception through psychedelic drug use). Huxley’s own title was a quotation from William Blake’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, in which Blake wrote: “If the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear to man as it is, infinite.” Although Morrison was known as the lyricist of the group, Krieger also made significant lyrical contributions, writing or co-writing some of the group’s biggest hits, including “Light My Fire”, “Love Me Two Times”, “Love Her Madly”, and “Touch Me”. On the other hand, Morrison, who didn’t write most songs using an instrument, would come up with vocal melodies for his own lyrics, with the other band members contributing chords and rhythm. Morrison did not play an instrument live (except for maracas and tambourine for most shows, and harmonica on a few occasions) or in the studio (excluding maracas, tambourine, handclaps, and whistling). However, he did play the grand piano on “Orange County Suite” and a Moog synthesizer on “Strange Days”. In June 1966, Morrison and the Doors were the opening act at the Whisky a Go Go in the last week of the residency of Van Morrison’s band Them. Van’s influence on Jim’s developing stage performance was later noted by John Densmore in his book Riders On The Storm: “Jim Morrison learned quickly from his near-namesake’s stagecraft, his apparent recklessness, his air of subdued menace, the way he would improvise poetry to a rock beat, even his habit of crouching down by the bass drum during instrumental breaks.” On the final night, the two Morrisons and their two bands jammed together on “Gloria”. In November 1966, Morrison and the Doors produced a promotional film for “Break on Through (To the Other Side)”, which was their first single release. The film featured the four members of the group playing the song on a darkened set with alternating views and close-ups of the performers while Morrison lip-synched the lyrics. Morrison and the Doors continued to make short music films, including “The Unknown Soldier”, “Moonlight Drive”, and “People Are Strange”. The Doors achieved national recognition after signing with Elektra Records in 1967. The single “Light My Fire” spent three weeks at number one on the Billboard Hot 100 chart in July/August 1967. This was a far cry from the Doors playing warm up for Simon and Garfunkel and playing at a high school as they did in Connecticut that same year. Later, the Doors appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show, a popular Sunday night variety series that had introduced the Beatles and Elvis Presley to the United States. Ed Sullivan requested two songs from the Doors for the show, “People Are Strange” and “Light My Fire”. Sullivan’s censors insisted that the Doors change the lyrics of the song “Light My Fire” from “Girl we couldn’t get much higher” to “Girl we couldn’t get much better” for the television viewers; this was reportedly due to what was perceived as a reference to drugs in the original lyrics. After giving assurances of compliance to the producer in the dressing room, the band agreed, “we’re not changing a word,” and proceeded to sing the song with the original lyrics. Sullivan was not happy and he refused to shake hands with Morrison or any other band member after their performance. Sullivan had a show producer tell the band that they would never appear on The Ed Sullivan Show again. Morrison reportedly said to the producer, in a defiant tone, “Hey man. We just 'did’ the Sullivan Show!” By the release of their second album, Strange Days, the Doors had become one of the most popular rock bands in the United States. Their blend of blues and dark psychedelic rock included a number of original songs and distinctive cover versions, such as their rendition of “Alabama Song”, from Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill’s opera, Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny. The band also performed a number of extended concept works, including the songs “The End”, “When the Music’s Over”, and “Celebration of the Lizard”. In 1966, photographer Joel Brodsky took a series of black-and-white photos of Morrison, in a photo shoot known as “The Young Lion” photo session. These photographs are considered among the most iconic images of Jim Morrison and are frequently used as covers for compilation albums, books, and other memorabilia of the Doors and Morrison. In late 1967 at an infamous concert in New Haven, Connecticut, he was arrested on stage, an incident that further added to his mystique and emphasized his rebellious image. In 1968, the Doors released their third studio album, Waiting for the Sun. The band performed on July 5 at the Hollywood Bowl, this performance became famous with the DVD: Live at the Hollywood Bowl. It’s also this year that the band played, for the first time, in Europe. Their fourth album, The Soft Parade, was released in 1969. It was the first album where the individual band members were given credit on the inner sleeve for the songs they had written. Previously, each song on their albums had been credited simply to “the Doors”. On September 6 and 7, 1968, the Doors played four performances at the Roundhouse, London, England with Jefferson Airplane which were filmed by Granada for a television documentary The Doors are Open directed by John Sheppard. Around this time, Morrison—who had long been a heavy drinker—started showing up for recording sessions visibly inebriated. He was also frequently late for live performances. By early 1969, the formerly svelte singer had gained weight, grown a beard and mustache, and had begun dressing more casually—abandoning the leather pants and concho belts for slacks, jeans and T-shirts. During a concert of March 1, 1969 at the Dinner Key Auditorium in Miami, Morrison attempted to spark a riot in the audience. He failed, but a warrant for his arrest was issued by the Dade County Police department three days later for indecent exposure. Consequently, many of the Doors’ scheduled concerts were canceled. In September 1970, Morrison was convicted of indecent exposure and profanity. Morrison, who attended the sentencing “in a wool jacket adorned with Indian designs”, silently listened as he was sentenced for six months in prison and had to pay a $500 fine. Morrison remained free on a $50,000 bond. At the sentencing, Judge Murray Goodman told Morrison that he was a “person graced with a talent” admired by many of his peers. In 2007 Florida Governor Charlie Crist suggested the possibility of a posthumous pardon for Morrison, which was announced as successful on December 9, 2010. Drummer John Densmore denied Morrison ever exposed himself on stage that night. Following The Soft Parade, the Doors released Morrison Hotel. After a lengthy break the group reconvened in October 1970 to record what would become their final album with Morrison, titled L.A. Woman. Shortly after the recording sessions for the album began, producer Paul A. Rothchild—who had overseen all of their previous recordings—left the project. Engineer Bruce Botnick took over as producer. Poetry and film Morrison began writing in earnest during his adolescence. At UCLA he studied the related fields of theater, film, and cinematography. He self-published two separate volumes of his poetry in 1969, titled The Lords / Notes on Vision and The New Creatures. The Lords consists primarily of brief descriptions of places, people, events and Morrison’s thoughts on cinema. The New Creatures verses are more poetic in structure, feel and appearance. These two books were later combined into a single volume titled The Lords and The New Creatures. These were the only writings published during Morrison’s lifetime. Morrison befriended Beat poet Michael McClure, who wrote the afterword for Danny Sugerman’s biography of Morrison, No One Here Gets Out Alive. McClure and Morrison reportedly collaborated on a number of unmade film projects, including a film version of McClure’s infamous play The Beard, in which Morrison would have played Billy the Kid. After his death, a further two volumes of Morrison’s poetry were published. The contents of the books were selected and arranged by Morrison’s friend, photographer Frank Lisciandro, and girlfriend Pamela Courson’s parents, who owned the rights to his poetry. The Lost Writings of Jim Morrison Volume I is titled Wilderness, and, upon its release in 1988, became an instant New York Times Bestseller. Volume II, The American Night, released in 1990, was also a success. Morrison recorded his own poetry in a professional sound studio on two separate occasions. The first was in March 1969 in Los Angeles and the second was on December 8, 1970. The latter recording session was attended by Morrison’s personal friends and included a variety of sketch pieces. Some of the segments from the 1969 session were issued on the bootleg album The Lost Paris Tapes and were later used as part of the Doors’ An American Prayer album, released in 1978. The album reached No. 54 on the music charts. Some poetry recorded from the December 1970 session remains unreleased to this day and is in the possession of the Courson family. Morrison’s best-known but seldom seen cinematic endeavor is HWY: An American Pastoral, a project he started in 1969. Morrison financed the venture and formed his own production company in order to maintain complete control of the project. Paul Ferrara, Frank Lisciandro and Babe Hill assisted with the project. Morrison played the main character, a hitchhiker turned killer/car thief. Morrison asked his friend, composer/pianist Fred Myrow, to select the soundtrack for the film. Personal life Morrison’s family Morrison’s early life was the semi-nomadic existence typical of military families. Jerry Hopkins recorded Morrison’s brother, Andy, explaining that his parents had determined never to use physical corporal punishment such as spanking on their children. They instead instilled discipline and levied punishment by the military tradition known as dressing down. This consisted of yelling at and berating the children until they were reduced to tears and acknowledged their failings. Once Morrison graduated from UCLA, he broke off most contact with his family. By the time Morrison’s music ascended to the top of the charts (in 1967) he had not been in communication with his family for more than a year and falsely claimed that his parents and siblings were dead (or claiming, as it has been widely misreported, that he was an only child). This misinformation was published as part of the materials distributed with the Doors’ self-titled debut album. Admiral Morrison was not supportive of his son’s career choice in music. One day, an acquaintance brought over a record thought to have Jim on the cover. The record was the Doors’ self-titled debut. The young man played the record for Morrison’s father and family. Upon hearing the record, Morrison’s father wrote him a letter telling him “to give up any idea of singing or any connection with a music group because of what I consider to be a complete lack of talent in this direction.” In a letter to the Florida Probation and Parole Commission District Office dated October 2, 1970, Morrison’s father acknowledged the breakdown in family communications as the result of an argument over his assessment of his son’s musical talents. He said he could not blame his son for being reluctant to initiate contact and that he was proud of him nonetheless. Morrison spoke fondly of his Irish and Scottish ancestry and was inspired by Celtic mythology in his poetry and songs. Celtic Family Magazine revealed in their 2016 Spring Issue his Morrison clan was originally from the Isle of Lewis, Scotland, while his Irish side, the Clelland clan whom married into the Morrison line were from County Down, Ireland. Relationships Morrison’s first major love affair was with Mary Werbelow, whom he met on the beach in Florida. The relationship lasted several years inspiring many of the songs on the first two Doors albums including the 11-minute ballad “The End” which Ray Manzarek said was originally “a short goodbye love song to Mary” calling her “Jim’s first love”. Werbelow has remained out of view to rock historians with one exception, a 2005 interview in the St. Petersburg Times where she said Morrison spoke to her before a photo shoot for the Doors’ fourth album and told her the first three albums were about her. Morrison spent nearly the entirety of his adult life with a woman named Pamela Courson after meeting while both attended university. They met before he gained fame or fortune and she encouraged him to develop his poetry. At times, Courson used the surname “Morrison” with his apparent consent, or at least lack of concern. She was buried as Pamela Susan Morrison. After Courson’s death in 1974, and after her parents petitioned the court for inheritance of Morrison’s estate, the probate court in California decided that she and Morrison had once had what qualified as a common-law marriage, despite neither having applied for such status while they were living and common-law marriage not being recognized in California. Morrison’s will lists him as “an unmarried person” but listed Courson as the sole heir. They had previously obtained marriage licenses in Colorado in 1967 and in Los Angeles in 1968. The Doors’ keyboardist Ray Manzarek described Courson as Morrison’s “other half”. Morrison spoke to Courson through his lyrics and his poetry and dedicated his published poetry book The New Creatures to her. Songs like “Love Street”, “Queen of the Highway”, “Blue Sunday", and “Indian Summer” as well as many of his poems were said to be written about her. Morrison also reportedly regularly had sex with fans ("groupies") such as Pamela Des Barres and Josépha Karcz, who wrote a novel about their night together, and had numerous short flings with other musicians, as well as writers and photographers involved in the music business. They included Nico, the singer associated with the Velvet Underground, a one-night stand with singer Grace Slick of Jefferson Airplane, an on-again, off-again relationship with 16 Magazine’s Gloria Stavers as well as an alleged alcohol-fueled encounter with Janis Joplin. Nico also wanted to marry Morrison and they cut their thumbs in the desert with a knife and let their blood mingle. Nico said, “We exchanged blood. I carry his blood inside me.” David Crosby said many years later Morrison treated Joplin meanly at a party at the Calabasas, California, home of John Davidson while Davidson was out of town. She reportedly hit him over the head with a bottle of whiskey in retaliation during a fight in front of witnesses. In 1965, Judy Huddleston met Morrison and claimed she had a four-year on-and-off relationship with him that she chronicled in her book Love Him Madly: An Intimate Memoir of Jim Morrison and an out-of-print book called This is the End My Only Friend: Living & Dying with Jim Morrison, which was updated as Like He Was God. In 1970, Morrison participated in a Celtic Pagan handfasting ceremony with rock critic author Patricia Kennealy. The couple signed a document declaring themselves wed, but none of the necessary paperwork for a legal marriage was filed with the state. Kennealy discussed her experiences with Morrison in her autobiography Strange Days: My Life With and Without Jim Morrison. In an interview reported in the book Rock Wives, Kennealy reveals that she and Jim Morrison were wed, sort of, in a witch ceremony in 1970, but that he turned “really cold” when Kennealy became pregnant—maybe, she speculates, because he had "20 paternity suits pending against him." She was asked if Morrison took the ceremony seriously and she answered “probably not too seriously”. In July 1971, Janet Erwin documented in her journal having dated Morrison during the last few weeks before he traveled to Paris. She wrote the essay “Your Ballroom Days Are Over.” On a couple of their nights together there were strong aftershocks from the 1971 San Fernando earthquake; one aftershock measured 5.0 on the Richter magnitude scale. At the time of Morrison’s death there were at least three paternity actions pending against him, although no claims were made against his estate by any of the putative paternity claimants. One persistent claim of paternity came from Cliff Morrison. Pamela Des Barres later said in her autobiography I’m With The Band: Confessions of a Groupie that Morrison “turned out to be very much a one-woman man”, referring to his relationship with Pamela Courson. Death Morrison joined Courson in Paris in March 1971, at an apartment he had rented on the rue Beautreillis (in the 4th arrondissement of Paris on the Right Bank). In letters he described going for long walks through the city, alone. During this time, Morrison shaved his beard and lost some of the weight he had gained in the previous months. Morrison died on July 3, 1971 at age 27. In the official account of his death, he was found in a Paris apartment bathtub (at 17–19 rue Beautreillis, 4th arrondissement) by Courson. The official cause of death was listed as “heart failure”, although no autopsy was performed. The absence of an autopsy left many questions regarding the cause of Morrison’s death. In Wonderland Avenue, Danny Sugerman discussed his encounter with Courson after she returned to the United States. According to Sugerman’s account, Courson stated that Morrison had died of an accidental heroin overdose, having snorted what he believed to be cocaine. Sugerman added that Courson had given numerous contradictory versions of Morrison’s death, saying at times that she had killed Morrison, or that his death was her fault. Courson’s story of Morrison’s unintentional ingestion of heroin, resulting in an accidental overdose, is supported by the confession of Alain Ronay, who has written that Morrison died of a hemorrhage after snorting Courson’s heroin, and that Courson nodded off instead of phoning for medical help, leaving Morrison alone and bleeding to death. Ronay confessed in an article in Paris that he then helped cover up the circumstances of Morrison’s death, and that there was no autopsy– the normal procedure when a young person dies suddenly– due to the medical examiner being bribed. In the epilogue of No One Here Gets Out Alive, Hopkins and Sugerman write that Ronay and Agnès Varda say Courson lied to the police who responded to the death scene, and later in her deposition, telling them Morrison never took drugs. She also claimed that she was Morrison’s cousin. In the epilogue to No One Here Gets Out Alive, Hopkins says that 20 years after Morrison’s death, Ronay and Varda broke their silence and gave this account “they arrived at the house shortly after Morrison’s death and Courson said that she and Morrison had taken heroin after a night of drinking. Morrison had been coughing badly, had gone to take a bath, and vomited blood.” Courson said that he appeared to recover and that she then went to sleep. When she awoke sometime later Morrison was unresponsive, so she called local friends. Hopkins and Sugerman also claim that Morrison had asthma and was suffering from a respiratory condition involving a chronic cough and vomiting blood on the night of his death. This theory is partially supported in The Doors (written by the remaining members of the band) in which they claim Morrison had been coughing up blood for nearly two months in Paris, but none of the members of the Doors were in Paris with Morrison in the months prior to his death. No other friends have reported witnessing Morrison coughing. According to a Madame Colinette, who was at Père Lachaise Cemetery mourning the recent loss of her husband, she witnessed Morrison’s funeral. The ceremony was “pitiful,” with several of the attendants muttering a few words, throwing a few flowers over the casket, then leaving quickly and hastily within minutes as if their lives depended upon it. Those who attended included Alain Ronay, Agnès Varda, Bill Siddons (manager), Courson, and Robin Wertle (Morrison’s Canadian private secretary at the time for a few months). In the first version of No One Here Gets Out Alive, published in 1980, Sugerman and Hopkins gave some credence to the rumor that Morrison may not have died at all, calling the fake death theory “not as far-fetched as it might seem”. This theory led to considerable distress for Morrison’s loved ones over the years, notably when fans would stalk them, searching for evidence of Morrison’s whereabouts. No proof of any kind has ever been offered to substantiate Sugerman’s suggestion that Morrison was still alive. In 1995, a new epilogue was added to Sugerman’s and Hopkins’s book, giving new facts about Morrison’s death and discounting the fake death theory saying “As time passed, some of Jim and Pamela [Courson]'s friends began to talk about what they knew, and although everything they said pointed irrefutably to Jim’s demise, there remained and probably always will be those who refuse to believe that Jim is dead and those who will not allow him to rest in peace.” In 2007, Sam Bernett, a former manager of the Rock 'n’ Roll Circus nightclub, released a (French) book titled “The End: Jim Morrison”, alleging that Morrison overdosed on heroin in his nightclub. He claims that Morrison went to the club to buy heroin for Courson, used some himself and died in the bathroom, and that his body was then moved by Patrick Chauvel, who corroborates the move, along with two unidentified drug dealers, nicknamed ‘Le Chinois’ and ‘Le Petit Robert’ out the back of the Nightclub so as to prevent a scandal and then bundled into a taxi with the two dealers, which then drove to Morrison’s rue Beautrellis apartment. Apart from Chauvel, one of the other patrons at the club who state that they helped move Morrison was interviewed in the documentary Rock Poet: Jim Morrison (2010). According to Bernett, the heroin was ultimately supplied by the aristocrat Jean de Breiteuil. In 2014, Marianne Faithfull claimed that her boyfriend, de Breiteuil, received a late-night phone call and he alone rushed over to Morrison’s apartment on the day of his death. Near the end of an 1986 audio interview, with radio host Roger Steffens and Doors drummer John Densmore. Steffens recounts that he had been told two days after Morrison’s death, by a shaking Marianne Faithfull and her lover Jean de Breiteuil in Marrakesh of the details of Morrison’s demise, with both Faithfull and Breiteuil having been in Morrison’s apartment after his return from the nightclub and seeing him dead in the bathroom, a scene which motivated them to quickly flee the country, flying to Tangier the next day and then on to Marrakesh, where Steffens happened to be living in 1971. Faithfull would consistently decline to comment on this thereafter until 2014. Steffens remarked that he found it amazing how Faithfull had never publicly discussed the tragedy from 1971 up to the time of recording, 1986. As early as the 1990s, Cameron Watson, an American working as a DJ in Paris at that time, would give the account that while working in the Parisian nightclub La Bulle in July 1971, two “well dressed” drug dealers arrived in the early morning hours at the club and told him that Jim Morrison had just died, Watson then announced this to the few remaining patrons at the club, the first public announcement of his demise and which contributed to the growth of the local parisian rumors. Paris Journal After his death, a notebook of poetry written by Morrison was recovered entitled Paris Journal which amongst other personal details, contains the allegorical foretelling of a man who will be left grieving and having to abandon his belongings, due to a police investigation into a death connected to the Chinese opium trade. Weeping, he left his pad on orders from police & furnishings hauled away, all records & momentos, & reporters calculating tears & curses for the press: “I hope the Chinese junkies get you” & they will for the [opium] poppy rules the world. The concluding stanzas of this poem end with conveying a disappointment for someone who he had an intimate relationship with and a further invocation of Billy/the killer Hitchhiker, a common character in Morrison’s body of work. This is my poem for you, Great flowing funky flower’d beast, Great perfumed wreck of hell... Someone new in your knickers & who would that be? You know, You know more, than you let on... Tell them you came & saw & look’d into my eyes & saw the shadow of the guard receding, Thoughts in time & out of season The Hitchiker stood by the side of the road & levelled his thumb in the calm calculus of reason. In 2013 another of Morrison’s notebooks from Paris, found alongside the Paris Journal in the same box, known as the 127 Fascination box, sold for $250,000. at auction. This box of personal belongings similarly contained a home movie of Pamela Courson, the only film so far recovered, to be shot by Morrison. The box also housed a number of older notebooks and journals and may have potentially included the “Steno Pad” and falsely titled “The Lost Paris Tapes” if they had not been separated from the primary collection and sold by Philippe Dalecky with this promotional title. This tape was later determined by avid listeners to be largely of Jomo & The Smoothies recordings of Morrison, friends and producer Paul Rothchild loose jamming in Los Angeles well before 1971. Grave site Morrison was buried in Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, one of the city’s most visited tourist attractions. The grave had no official marker until French officials placed a shield over it, which was stolen in 1973. The grave was listed in the cemetery directory with Morrison’s name incorrectly rearranged as “Douglas James Morrison.” In 1981, Croatian sculptor Mladen Mikulin voluntarily placed a bust of his own design and a new gravestone with Morrison’s name at the grave to commemorate the 10th anniversary of his death; the bust was defaced through the years by cemetery vandals and later stolen in 1988. Mikulin made another bust of Morrison in 1989, and a bronze portrait of him in 2001; neither piece is at the gravesite. In the early 1990s, Morrison’s father, George Stephen Morrison, after consulting with E. Nicholas Genovese, professor of classics and humanities, San Diego State University, placed a flat stone on the grave. The bronze plaque thereon bears the Greek inscription: ΚΑΤΑ ΤΟΝ ΔΑΙΜΟΝΑ ΕΑΥΤΟΥ, literally meaning “according to his own daemon, i.e., guiding spirit,” to convey the sentiment “True to Himself.” Artistic influences As a naval family the Morrisons relocated frequently. Consequently, Morrison’s early education was routinely disrupted as he moved from school to school. Nonetheless he was drawn to the study of literature, poetry, religion, philosophy and psychology, among other fields. Biographers have consistently pointed to a number of writers and philosophers who influenced Morrison’s thinking and, perhaps, his behavior. While still in his teens Morrison discovered the work of philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche. He was also drawn to the poetry of William Blake, Charles Baudelaire and Arthur Rimbaud. Beat Generation writers such as Jack Kerouac also had a strong influence on Morrison’s outlook and manner of expression; Morrison was eager to experience the life described in Kerouac’s On the Road. He was similarly drawn to the work of French writer Louis-Ferdinand Céline. Céline’s book, Voyage au Bout de la Nuit (Journey to the End of the Night) and Blake’s Auguries of Innocence both echo through one of Morrison’s early songs, “End of the Night”. Morrison later met and befriended Michael McClure, a well known beat poet. McClure had enjoyed Morrison’s lyrics but was even more impressed by his poetry and encouraged him to further develop his craft. Morrison’s vision of performance was colored by the works of 20th-century French playwright Antonin Artaud (author of Theater and its Double) and by Julian Beck’s Living Theater. Other works relating to religion, mysticism, ancient myth and symbolism were of lasting interest, particularly Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces. James Frazer’s The Golden Bough also became a source of inspiration and is reflected in the title and lyrics of the song “Not to Touch the Earth”. Morrison was particularly attracted to the myths and religions of Native American cultures. While he was still in school, his family moved to New Mexico where he got to see some of the places and artifacts important to the American Southwest Indigenous cultures. These interests appear to be the source of many references to creatures and places such as lizards, snakes, deserts and “ancient lakes” that appear in his songs and poetry. His interpretation and imagination of the practices of Native American ceremonial people (which, based on his readings, he referred to by the anthropological but inaccurate term “shamans”) influenced his stage routine, notably in seeking trance states and vision through dancing to the point of exhaustion. In particular, Morrison’s poem “The Ghost Song” was inspired by his readings about the Native American Ghost Dance. Jim Morrison’s vocal influences included Elvis Presley and Frank Sinatra, which is evident in his own baritone crooning style used in several of the Doors’ songs and in the 1981 documentary The Doors: A Tribute to Jim Morrison, producer Paul Rothchild refers his first impression of Morrison as being a “Rock and Roll Bing Crosby”. It is mentioned within the pages of No One Here Gets Out Alive by Danny Sugerman, that Morrison as a teenager was such a fan of Presley’s music that he demanded people be quiet when Elvis was on the radio. The Frank Sinatra influence is mentioned in the pages of The Doors, The Illustrated History also by Sugerman, where Frank Sinatra is listed on Morrison’s Band Bio as being his favorite singer. Reference to this can also be found in a Rolling Stone article about Jim Morrison, regarding the Top 100 rock singers of all time. Legacy Musical Morrison was, and continues to be, one of the most popular and influential singer-songwriters and iconic front men in rock history. To this day Morrison is widely regarded as the prototypical rock-star: surly, sexy, scandalous, and mysterious. The leather pants he was fond of wearing both onstage and off have since become stereotyped as rock-star apparel. In 2011, a Rolling Stone readers’ pick placed Jim Morrison in fifth place of the magazine’s “Best Lead Singers of All Time”. Iggy and the Stooges are said to have formed after lead singer Iggy Pop was inspired by Morrison while attending a Doors concert in Ann Arbor, Michigan. One of Pop’s most popular songs, “The Passenger”, is said to be based on one of Morrison’s poems. After Morrison’s death, Pop was considered as a replacement lead singer for the Doors; the surviving Doors gave him some of Morrison’s belongings and hired him as a vocalist for a series of shows. Wallace Fowlie, professor emeritus of French literature at Duke University, wrote Rimbaud and Jim Morrison, subtitled “The Rebel as Poet– A Memoir”. In this he recounts his surprise at receiving a fan letter from Morrison who, in 1968, thanked him for his latest translation of Arthur Rimbaud’s verse into English. “I don’t read French easily”, he wrote, “...your book travels around with me.” Fowlie went on to give lectures on numerous campuses comparing the lives, philosophies and poetry of Morrison and Rimbaud. The book The Doors by the remaining Doors quotes Morrison’s close friend Frank Lisciandro as saying that too many people took a remark of Morrison’s that he was interested in revolt, disorder, and chaos “to mean that he was an anarchist, a revolutionary, or, worse yet, a nihilist. Hardly anyone noticed that Jim was paraphrasing Rimbaud and the Surrealist poets.” Layne Staley, the vocalist of Alice in Chains, Eddie Vedder, the vocalist of Pearl Jam, Scott Weiland, the vocalist of Stone Temple Pilots and Velvet Revolver, Julian Casablancas of the Strokes, James LaBrie of Dream Theater, as well as Scott Stapp of Creed and Ville Valo of H.I.M., have all said that Morrison was their biggest influence and inspiration. Stone Temple Pilots and Velvet Revolver have both covered “Roadhouse Blues” by the Doors. Weiland also filled in for Morrison to perform “Break On Through (To The Other Side)” with the rest of the Doors. Stapp filled in for Morrison for “Light My Fire”, “Riders on the Storm” and “Roadhouse Blues” on VH1 Storytellers. Creed performed their version of “Roadhouse Blues” with Robby Krieger for the 1999 Woodstock Festival. Morrison’s recital of his poem “Bird Of Prey” can be heard throughout the song “Sunset” by Fatboy Slim. Rock band Bon Jovi featured Morrison’s grave in their “I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead” video clip. The band Radiohead mentions Jim Morrison in their song “Anyone Can Play Guitar”, stating “I wanna be wanna be wanna be Jim Morrison”. Alice Cooper in the liner notes of the album Killer stated that the song “Desperado” is about Jim Morrison. The leather pants of U2's Bono’s “The Fly” persona for the Achtung Baby era and subsequent Zoo TV Tour is attributed to Jim Morrison. On their 2008 album The Hawk Is Howling In 2012 electronic music producer Skrillex released “Breakn’ a Sweat” which contained vocals from an interview with Jim Morrison. In popular culture In June 2013, a new fossil analysis revealed a lizard, one of the largest ever known that lived on Myanmar, was given the moniker Barbaturex morrisoni in honor of Morrison. “This is a king lizard, and he was the lizard king, so it just fit,” said Jason Head, a paleontologist at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. The animated television show The Simpsons has made numerous references to Morrison, including Krusty the Klown singing Break On Through ("I Love Lisa", Season 4); Otto Mann telling Homer that “me and the admiral do not get along” (a reference to Morrison and his estranged father, Rear Admiral George Stephen Morrison ("The Otto Show", Season 3)); mention of Morrison’s grave ("The Devil Wears Nada", Season 21). Another reference, “I am the lizard queen!” Is bellowed by Lisa Simpson at the end of her encounter with psychedelic theme-ride river water at Duff Gardens ("Selma’s Choice", Season 4). In another episode, Morrison himself was visually depicted in the form of a hallucination had by Homer Simpson when he was forming a rock band ("Covercraft", Season 26) In Stephen King’s The Stand, Stu Redman tells a friend about his encounter with Jim Morrison long after Morrison’s supposed death, late at night at a lonely Texas gas station in the 1980s. Discography Books By Morrison * The Lords and the New Creatures (1969). 1985 edition: ISBN 0-7119-0552-5 * An American Prayer (1970) privately printed by Western Lithographers. (Unauthorized edition also published in 1983, Zeppelin Publishing Company, ISBN 0-915628-46-5. The authenticity of the unauthorized edition has been disputed.) * Arden lointain, edition bilingue (1988), trad. de l’américain et présenté par Sabine Prudent et Werner Reimann. [Paris]: C. Bourgois. 157 p. N.B.: Original texts in English, with French translations, on facing pages. ISBN 2-267-00560-3 * Wilderness: The Lost Writings Of Jim Morrison (1988). 1990 edition: ISBN 0-14-011910-8 * The American Night: The Writings of Jim Morrison (1990). 1991 edition: ISBN 0-670-83772-5 About Morrison * Linda Ashcroft, Wild Child: Life with Jim Morrison, (1997) ISBN 1-56025-249-9 * Lester Bangs, “Jim Morrison: Bozo Dionysus a Decade Later” in Main Lines, Blood Feasts, and Bad Taste: A Lester Bangs Reader, John Morthland, ed. Anchor Press (2003) ISBN 0-375-71367-0 * Stephen Davis, Jim Morrison: Life, Death, Legend, (2004) ISBN 1-59240-064-7 * John Densmore, Riders on the Storm: My Life With Jim Morrison and the Doors (1991) ISBN 0-385-30447-1 * Dave DiMartino, Moonlight Drive (1995) ISBN 1-886894-21-3 * Steven Erkel, "The Poet Behind the Doors: Jim Morrison’s Poetry and the 1960s Countercultural Movement" (2011) * Wallace Fowlie, Rimbaud and Jim Morrison (1994) ISBN 0-8223-1442-8 * Jerry Hopkins, The Lizard King: The Essential Jim Morrison (1995) ISBN 0-684-81866-3 * Jerry Hopkins and Danny Sugerman, No One Here Gets Out Alive (1980) ISBN 0-85965-138-X * Mike Jahn, “Jim Morrison and the Doors” (1969)Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 71-84745 * Dylan Jones, Jim Morrison: Dark Star, (1990) ISBN 0-7475-0951-4 * Patricia Kennealy, Strange Days: My Life With and Without Jim Morrison (1992) ISBN 0-525-93419-7 * Gerry Kirstein, “Some Are Born to Endless Night: Jim Morrison, Visions of Apocalypse and Transcendence” (2012) ISBN 1451558066 * Frank Lisciandro, Morrison: A Feast of Friends (1991) ISBN 0-446-39276-6, Morrison—Un festin entre amis (1996) (French) * Frank Lisciandro, Jim Morrison: An Hour For Magic (A Photojournal) (1982) ISBN 0-85965-246-7, James Douglas Morrison (2005) (French) * Ray Manzarek, Light My Fire (1998) ISBN 0-446-60228-0. First by Jerry Hopkins and Danny Sugerman (1981) * Peter Jan Margry, The Pilgrimage to Jim Morrison’s Grave at Père Lachaise Cemetery: The Social Construction of Sacred Space. In idem (ed.), Shrines and Pilgrimage in the Modern World. New Itineraries into the Sacred. Amsterdam University Press, 2008, p. 145–173. * Thanasis Michos, The Poetry of James Douglas Morrison (2001) ISBN 960-7748-23-9 (Greek) * Daveth Milton, We Want The World: Jim Morrison, The Living Theatre, and the FBI, (2012) ISBN 978-0957051188 * Mark Opsasnick, The Lizard King Was Here: The Life and Times of Jim Morrison in Alexandria, Virginia (2006) ISBN 1-4257-1330-0 * James Riordan & Jerry Prochnicky, Break on through: The Life and Death of Jim Morrison (1991) ISBN 0-688-11915-8 * Adriana Rubio, Jim Morrison: Ceremony... Exploring the Shaman Possession (2005) ISBN * Howard Sounes. 27: A History of the 27 Club Through the Lives of Brian Jones, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison, Kurt Cobain, and Amy Winehouse, Boston: Da Capo Press, 2013. ISBN 0-306-82168-0. * The Doors (remaining members Ray Manzarek, Robby Krieger, John Densmore) with Ben Fong-Torres, The Doors (2006) ISBN 1-4013-0303-X * Mick Wall, “Love Becomes a Funeral Pyre: A Biography of the Doors”, (2014) Films Films by Morrison * HWY: An American Pastoral Documentaries featuring Morrison Films about The Doors * The Doors (1991), A film by director Oliver Stone, starring Val Kilmer as Morrison and with cameos by Krieger and Densmore. Kilmer’s performance was praised by some critics. Ray Manzarek, The Doors’ keyboardist, harshly criticized Stone’s portrayal of Morrison, and noted that numerous events depicted in the movie were pure fiction. David Crosby on an album by CPR wrote and recorded a song about the movie with the lyric: “And I have seen that movie– and it wasn’t like that.” References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jim_Morrison

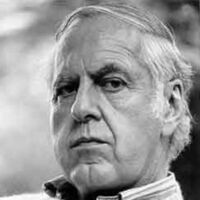

John Edward Masefield (1 June 1878 – 12 May 1967) was an English poet and writer, and Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom from 1930 until his death in 1967. He is remembered as the author of the classic children's novels The Midnight Folk and The Box of Delights, and poems, including "The Everlasting Mercy" and "Sea-Fever". Early life Masefield was born in Ledbury in Herefordshire, to Caroline and George Masefield, a solicitor. His mother died giving birth to his sister when Masefield was only six, and he went to live with his aunt. His father died soon after following a mental breakdown. After an unhappy education at the King's School in Warwick (now known as Warwick School), where he was a boarder between 1888 and 1891, he left to board the HMS Conway, both to train for a life at sea, and to break his addiction to reading, of which his aunt thought little. He spent several years aboard this ship and found that he could spend much of his time reading and writing. It was aboard the Conway that Masefield's love for story-telling grew. While on the ship, he listened to the stories told about sea lore. He continued to read, and felt that he was to become a writer and story teller himself. In 1894, Masefield boarded the Gilcruix, destined for Chile - this first voyage bringing him the experience of sea sickness. He recorded his experiences while sailing through the extreme weather, his journal entries reflecting a delight in seeing flying fish, porpoises, and birds, and was awed by the beauty of nature, including a rare sighting of a nocturnal rainbow on his voyage. On reaching Chile, Masefield suffered from sunstroke and was hospitalized. He eventually returned home to England as a passenger aboard a steam ship. In 1895, Masefield returned to sea on a windjammer destined for New York City. However, the urge to become a writer and the hopelessness of life as a sailor overtook him, and in New York, he deserted ship. He lived as a vagrant for several months, before returning to New York City, he did many odd jobs, finding work as an assistant to a bar keeper. Sometime around Christmas in 1895, Masefield read the December 1895 edition of Truth, a New York periodical, which contained the poem "The Piper of Arll" by Duncan Campbell Scott. Ten years later, Masefield wrote to Scott to tell him what reading that poem had meant to him: "I had never (till that time) cared very much for poetry, but your poem impressed me deeply, and set me on fire. Since then poetry has been the one deep influence in my life, and to my love of poetry I owe all my friends, and the position I now hold." For the next two years, Masefield was employed in a carpet factory, where long hours were expected and conditions were far from ideal. He purchased up to 20 books a week, and devoured both modern and classical literature. His interests at this time were diverse and his reading included works by George du Maurier, Dumas, Thomas Browne, Hazlitt, Dickens, Kipling, and R. L. Stevenson. Chaucer also became very important to him during this time, as well as poetry by Keats and Shelley. He eventually returned home to England in 1897 as a passenger aboard a steam ship. When Masefield was 23, he met his future wife, Constance Crommelin, who was 35. Educated in classics and English Literature, and a mathematics teacher, Constance was a match for Masefield despite the difference in age. The couple had two children (Judith, born in 1904, and Lewis, in 1910). By the time he was 24, Masefield's poems were being published in periodicals and his first collected works, Salt-Water Ballads (1902) was published, the poem "Sea-Fever" appearing in this book. Masefield then wrote the novels, Captain Margaret (1908) and Multitude and Solitude (1909). In 1911, after a long drought of poem writing, he composed "The Everlasting Mercy", the first of his narrative poems, and within the next year, Masefield had produced two more, "The Widow in the Bye Street" and "Dauber". As a result, Masefield became widely known to the public and was praised by critics, and in 1912, he was awarded the annual Edmond de Polignac prize. World War I to appointment as Poet Laureate When World War I began, though old enough to be exempted from military service, Masefield joined the staff of a British hospital for French soldiers, Hôpital Temporaire d'Arc-en-Barrois, Haute-Marne, France, serving briefly in 1915 as a hospital orderly, later publishing his own account of his experiences. After returning home, Masefield was invited to the United States on a three month lecture tour. Although Masefield's primary purpose was to lecture on English Literature, a secondary purpose was to collect information on the mood and views of Americans regarding the war in Europe. When he returned to England, he submitted a report to the British Foreign Office, and suggested that he be allowed to write a book about the failure of the allied efforts in the Dardanelles, which possibly could be used in the US in order to counter what he thought was German propaganda there. As a result, Masefield wrote Gallipoli. This work was a success, encouraging the British people, and lifting them somewhat from the disappointment they had felt as a result of the Allied losses in the Dardanelles. Due to the success of his wartime writings, Masefield met with the head of British Military Intelligence in France and was asked to write an account of the Battle of the Somme. Although Masefield had grand ideas for his book, he was denied access to the official records, and therefore, what was to be his preface to the book was published as "The Old Front Line", a description of the geography of the Somme area. In 1918, Masefield returned to America on his second lecture tour. Masefield spent much of his time speaking and lecturing to American soldiers waiting to be sent to Europe. These speaking engagements were very successful, and on one occasion, a battalion of all black soldiers danced and sang for him after his talk. During this tour, he matured as a public speaker and realized his ability to touch the emotions of his audience with his style of speaking, learning to speak publicly with his own heart, rather than from dry scripted speeches. Towards the end of his trip, both Yale and Harvard Universities conferred honorary Doctorates of Letters on him. Masefield entered the 1920s as an accomplished and respected writer. His family was able to settle on Boar's Hill, a somewhat rural setting not far from Oxford, and Masefield took up beekeeping, goat-herding and poultry-keeping. He continued to meet with success, the 1923 edition of "Collected Poems" selling approximately 80,000 copies. He produced three poems early in this decade. The first was Reynard The Fox, a poem that has been critically compared with works of Geoffrey Chaucer. This was followed by Right Royal and King Cole, poems where the relationship of humanity and nature emphasized. While Reynard is the best known of these, all met with acclaim. After King Cole Masefield turned away from the long poem and back to the novel, and from 1924 till the Second World War published twelve novels, which vary from stories of the sea (The Bird of Dawning, Victorious Troy) to social novels about modern England (The Hawbucks, The Square Peg), and from tales of an imaginary land in Central America (Sard Harker, Odtaa) to fantasies for children (The Midnight Folk, The Box of Delights). This variety in genre testifies most impressively to the breadth of his imagination, though it probably reduced his sales (which remained very respectable, however), since most readers of novels like knowing what to expect from their favourite authors. In this same period he wrote a large number of dramatic pieces. Most of these were based on Christian themes, and Masefield, to his amazement, encountered a ban on the performance of plays on biblical subjects that went back to the Reformation and had been revived a generation earlier to prevent production of Oscar Wilde's Salome. However, a compromise was reached, and in 1928 his "The Coming of Christ" was the first play to be performed in an English Cathedral since the Middle Ages. In 1921, Masefield received an Honorary Doctorate of Literature from Oxford University, and in 1923, organized the Oxford Recitations, an annual contest whose purpose was "to discover good speakers of verse and to encourage ‘the beautiful speaking of poetry.’" The Recitations were seen as a success given the numbers of contest applicants, the promotion of natural speech in poetical recitations, and the number of people learning how to listen to poetry. Masefield began to question however, whether the Recitations should continue as a contest, believing that the event should become more of a festival. In 1929, Masefield broke with the contest concept, and the Recitations came to an end. Later years and death In 1930, on the death of Robert Bridges, a new Poet Laureate was needed. Many felt that Rudyard Kipling was a likely choice, however, upon the recommendation of Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald, King George V appointed Masefield, who remained in office until his death in 1967. The only person to hold the office for a longer period was Alfred, Lord Tennyson. On his appointment The Times newspaper said of him: ... his poetry could touch to beauty the plain speech of everyday life. Although the requirements of Poet Laureate had changed, and those in the office were rarely required to write verse for special occasions, Masefield took his appointment seriously and produced a large quantity of verse. Poems composed in his official capacity were sent to The Times. Masefield's modesty was shown by his inclusion of a stamped envelope with each submission so that his composition could be returned if it were found unacceptable for publication. Masefield was commissioned to write a poem to be set to music by the Master of the King's Musick, Sir Edward Elgar and performed at the unveiling of the Queen Alexandra Memorial by the King on 8 June 1932. This was the ode "So many true Princesses who have gone". After his appointment, Masefield was awarded the Order of Merit by King George V and many honorary degrees from British universities, in 1937 being elected as President of the Society of Authors. Masefield encouraged the continued development of English literature and poetry, and began the annual awarding of the Royal Medals for Poetry for a first or second published edition of poetry by a poet under the age of 35. Additionally, his speaking engagements were calling him further away, often on much longer tours, yet he still produced significant amounts of work in a wide variety of genres. To those he had already used he now added autobiography, producing New Chum, In the Mill, and So Long to Learn. Some critics judged Masefield to be an even finer writer of prose than of verse. It was not until about the age of 70 that Masefield slowed his pace due to illness. In 1960, Constance died at 93, after a long illness. Although her death was heartrending, he had spent a tiring year watching the woman he loved die. He continued his duties as Poet Laureate; In Glad Thanksgiving, his last book, was published when he was 88 years old. In late 1966, Masefield developed gangrene in his ankle. This spread to his leg, and he died of the infection on 12 May 1967. According to his wishes, he was cremated and his ashes placed in Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey. Later, the following verse was discovered, written by Masefield, addressed to his "Heirs, Administrators, and Assigns": Let no religious rite be done or read In any place for me when I am dead, But burn my body into ash, and scatter The ash in secret into running water, Or on the windy down, and let none see; And then thank God that there's an end of me. The Masefield Centre at Warwick School, which Masefield attended, and a high school in Ledbury, Herefordshire have been named in his honour. In 1977, Folkways Records released an album of his poetry, including some read by Masefield himself. Art song settings Many of Masefield's short poems were set as art songs by British composers of the time. Best known by far is John Ireland's "Sea Fever", the lasting popularity of which belies any mismatch between the urgency of the language and the slow, swung melody. Frederick Keel crafted several songs drawn from the Salt-Water Ballads and elsewhere. Of these, "Trade Winds" was particularly popular in its day, despite the tongue-twisting challenges the text presents to the singer. Keel's defiant setting of "Tomorrow", written while interned at Ruhleben during World War I, was frequently programmed at the BBC Proms after the war. Another memorable wartime composition is Ivor Gurney's climactic declamation of "By a bierside", a setting quickly set down in 1916 during a brief spell behind the lines. References Wikipedia - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Masefield

I write poetry. It's my entire life, pretty much. Part of me wants to delete all of this, because most of it is childish and stupid. There is a part of me though that kinda wants to hang on to some of it cause it's part of my history. I no longer have physical copies of any of these, and if I delete it without copying it it'll just be gone. No editing; no rewrites; no revisions. Just gone. Never to return again. What should I do?

Charlotte Mary Mew (15 November 1869– 24 March 1928) was an English poetess, whose work spans the cusp between Victorian poetry and Modernism. She was born in Bloomsbury, London, the daughter of the architect Frederick Mew, who designed Hampstead town hall, and Anna Kendall.The marriage produced seven children. Charlotte, nicknamed Lotti by her family, attended Gower Street School, where she became infatuated with the school’s headmistress, Lucy Harrison, and lectures at University College London. Her father died in 1898 without making adequate provision for his family; two of her siblings suffered from mental illness, and were committed to institutions, and three others died in early childhood leaving Charlotte, her mother and her sister, Anne. Charlotte and Anne made a pact never to marry for fear of passing on insanity to their children. (One author calls Charlotte “almost certainly chastely lesbian)”. Through most of her adult life, Mew wore masculine attire and kept her hair short, adopting the appearance of a dandy.

Born near St. Louis, Missouri, on November 15, 1887, Marianne Moore was raised in the home of her grandfather, a Presbyterian pastor. After her grandfather's death, in 1894, Moore and her family stayed with other relatives, and in 1896 they moved to Carlisle, Pennsylvania. She attended Bryn Mawr College and received her B.A. in 1909. Following graduation, Moore studied typing at Carlisle Commercial College, and from 1911 to 1915 she was employed as a school teacher at the Carlisle Indian School. In 1918, Moore and her mother moved to New York City, and in 1921, she became an assistant at the New York Public Library. She began to meet other poets, such as William Carlos Williams and Wallace Stevens, and to contribute to the Dial, a prestigious literary magazine. She served as acting editor of the Dial from 1925 to 1929. Along with the work of such other members of the Imagist movement as Ezra Pound, Williams, and H. D., Moore's poems were published in the Egoist, an English magazine, beginning in 1915. In 1921, H.D. published Moore's first book, Poems, without her knowledge. Moore was widely recognized for her work; among her many honors were the Bollingen prize, the National Book Award, and the Pulitzer Prize. She wrote with the freedom characteristic of the other modernist poets, often incorporating quotes from other sources into the text, yet her use of language was always extraordinarily condensed and precise, capable of suggesting a variety of ideas and associations within a single, compact image. In his 1925 essay "Marianne Moore," William Carlos Williams wrote about Moore's signature mode, the vastness of the particular: "So that in looking at some apparently small object, one feels the swirl of great events." She was particularly fond of animals, and much of her imagery is drawn from the natural world. She was also a great fan of professional baseball and an admirer of Muhammed Ali, for whom she wrote the liner notes to his record, I Am the Greatest! Deeply attached to her mother, she lived with her until Mrs. Moore's death in 1947. Marianne Moore died in New York City in 1972. Poetry Collected Poems (1951) Like a Bulwark (1956) Nevertheless (1944) O to Be a Dragon (1959) Observations (1924) Poems (1921) Selected Poems (1935) Tell Me, Tell Me (1966) The Arctic Fox (1964) The Complete Poems of Marianne Moore (1967) The Pangolin and Other Verse (1936) What Are Years? (1941) Prose A Marianne Moore Reader (1961) Predilections (1955) The Complete Prose of Marianne Moore (1987)

I have always preferred to read a book than watch a film. Poetry became something I enjoyed because it doesn't always give up its meaning at first. You have to chew over it and contemplate. Some poetry expands my mind and other poetry breaks my heart. My life so far has been pretty straight forward - I have a lot to be grateful for. I'm mostly a happy person, but like everyone sometimes I get sad, and when I do I write.

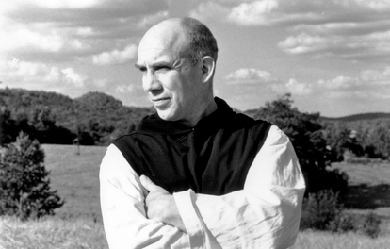

Thomas Merton (January 31, 1915 – December 10, 1968) was an American Trappist monk, writer, theologian, mystic, poet, social activist, and scholar of comparative religion. On May 26, 1949, he was ordained to the priesthood and given the name Father Louis.Merton wrote more than 70 books, mostly on spirituality, social justice and a quiet pacifism, as well as scores of essays and reviews. Among Merton’s most enduring works is his bestselling autobiography The Seven Storey Mountain (1948), which sent scores of World War II veterans, students, and even teenagers flocking to monasteries across the US, and was also featured in National Review’s list of the 100 best non-fiction books of the century. Merton was a keen proponent of interfaith understanding. He pioneered dialogue with prominent Asian spiritual figures, including the Dalai Lama, the Japanese writer D. T. Suzuki, the Thai Buddhist monk Buddhadasa, and the Vietnamese monk Thich Nhat Hanh, and authored books on Zen Buddhism and Taoism. In the years since his death, Merton has been the subject of several biographies.

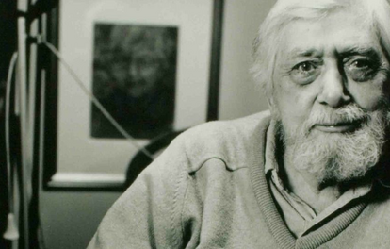

Edwin George Morgan (27 April 1920 – 17 August 2010) was a Scottish poet and translator who was associated with the Scottish Renaissance. He is widely recognised as one of the foremost Scottish poets of the 20th century. In 1999, Morgan was made the first Glasgow Poet Laureate. In 2004, he was named as the first Scottish national poet: The Scots Makar. Life and career Morgan was born in Glasgow and grew up in Rutherglen. His parents were Presbyterian. As a child he was not surrounded by books, nor did he have any literary acquaintances. Schoolmates labelled him a swot. He convinced his parents to finance his membership of several book clubs in Glasgow. The Faber Book of Modern Verse (1936) was a “revelation” to him, he later said. Morgan entered the University of Glasgow in 1937. It was at university that he studied French and Russian, while self-educating in “a good bit of Italian and German” as well. After interrupting his studies to serve in World War II as a non-combatant conscientious objector with the Royal Army Medical Corps, Morgan graduated in 1947 and became a lecturer at the University. He worked there until his retirement as a full professor in 1980. Morgan described ‘CHANGE RULES!’ as 'the supreme graffito’, whose liberating double-take suggests both a lifelong commitment to formal experimentation and his radically democratic left-wing political perspectives. From traditional sonnet to blank verse, from epic seriousness to camp and ludic nonsense; and whether engaged in time-travelling space fantasies or exploring contemporary developments in physics and technology, the range of Morgan’s voices is a defining attribute. Morgan first outlined his sexuality in Nothing Not Giving Messages: Reflections on his Work and Life (1990). He had written many famous love poems, among them “Strawberries” and “The Unspoken”, in which the love object was not gendered; this was partly because of legal problems at the time but also out of a desire to universalise them, as he made clear in an interview with Marshall Walker. At the opening of the Glasgow LGBT Centre in 1995, he read a poem he had written for the occasion, and presented it to the Centre as a gift. In 2002, he became the patron of Our Story Scotland. At the Opening of the Scottish Parliament building in Edinburgh on 9 October 2004, Liz Lochhead read a poem written especially for the occasion by Morgan, titled “Poem for the Opening of the Scottish Parliament”. She was announced as Morgan’s successor as Scots Makar in January 2011. Near the end of his life, Morgan reached a new audience after collaborating with the Scottish band Idlewild on their album The Remote Part. In the closing moments of the album’s final track "In Remote Part/ Scottish Fiction", he recites a poem, “Scottish Fiction”, written specifically for the song. In 2007, Morgan contributed two poems to the compilation Ballads of the Book, for which a range of Scottish writers created poems to be made into songs by Scottish musicians. Morgan’s songs “The Good Years” and “The Weight of Years” were performed by Karine Polwart and Idlewild respectively. Nobel Laureate Seamus Heaney "[paid] formal homage" during a 2005 visit. In later life Morgan was cared for at a residential home as his health worsened. He published a collection in April 2010, months before his death, titled Dreams and Other Nightmares to mark his 90th birthday. Up until his death, he was the last survivor of the canonical 'Big Seven’ (the others being Hugh MacDiarmid, Robert Garioch, Norman MacCaig, Iain Crichton Smith, George Mackay Brown, and Sorley MacLean). On 17 August 2010, Edwin Morgan died of pneumonia in Glasgow, Scotland, at the age of 90. The Scottish Poetry Library made the announcement in the morning. Tributes came from, among others, politicians Alex Salmond and Iain Gray, as well as Carol Ann Duffy, the UK Poet Laureate. Testamentary provisions First Minister of Scotland Alex Salmond’s leader’s speech to the Scottish National Party Conference at Inverness on 22 October 2011 referred to Morgan’s bequest of £918,000 to the party in his will as “transformational”. The next day it was announced that all of the bequest would be used for the party’s independence referendum campaign. Morgan also left £45,000 to a number of friends, former colleagues and charity organisations and set aside another £1 million for the creation of an annual award scheme for young poets in Scotland. Poetry Morgan worked in a wide range of forms and styles, from the sonnet to concrete poetry. His Collected Poems appeared in 1990. He has also translated from a wide range of languages, including Russian, Hungarian, French, Italian, Latin, Spanish, Portuguese, German and Old English (Beowulf). Many of these are collected in Rites of Passage. Selected Translations (1976). His 1952 translation of Beowulf has become a standard translation in America. Morgan was also influenced by the American beat poets, with their simple, accessible ideas and language being prominent features in his work. In 1968 Morgan wrote a poem entitled Starlings In George Square. This poem could be read as a comment on society’s reluctance to accept the integration of different races. Other people have also considered it to be about the Russian Revolution in which “Starling” could be a reference to “Stalin”. Other notable poems include: The Death of Marilyn Monroe (1962) – an outpouring of emotion after the death of one of the world’s most talented women. The Billy Boys (1968) – flashback of the gang warfare in Glasgow led by Billy Fullerton in the Thirties. Glasgow 5 March 1971 – robbery by two youths by pushing an unsuspecting couple through a shop window on Sauchiehall Street In the Snackbar – concise description of an encounter with a disabled pensioner in a Glasgow restaurant. A Good Year for Death (26 September 1977) – a description of five famous people from the world of popular culture who died in 1977 Poem for the Opening of the Scottish Parliament – which was read by Liz Lochhead at the opening ceremony because he was too ill. (9 October 2004) Books Awards and honours * 1972 PEN Memorial Medal (Hungary) * 1982 OBE * 1983 Saltire Society Scottish Book of the Year Award for Poems of Thirty Years * 1985 Soros Translation Award (New York) * 1998 Stakis Prize for Scottish Writer of the Year for Virtual and Other Realities * 2000 Queen’s Gold Medal for Poetry * 2001 Oxford-Weidenfeld Translation Prize for Jean Racine: Phaedra * 2002 The Saltire Society’s Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun award for notable service to Scotland * 2003 Jackie Forster Memorial Award for Culture * 2003 Lifetime Achievement Award for Literature, from the Saltire Society and the Scottish Arts Council * 2007 T. S. Eliot Prize for A Book of Lives. * 2008 Scottish Arts Council Book of the Year Award References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edwin_Morgan_(poet)