Info

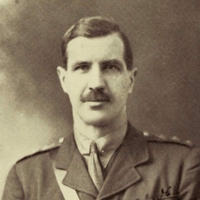

Isaac Rosenberg (25 November 1890– 1 April 1918) was an English poet and artist. His Poems from the Trenches are recognized as some of the most outstanding poetry written during the First World War. Early life Isaac Rosenberg was born in Bristol, the second of six children and the eldest son of his parents (his twin brother died at birth), Barnett (formerly Dovber) and Hacha Rosenberg, who were Lithuanian Jewish immigrants to Great Britain from Dvinsk (now in Latvia). In 1897, the family moved to Stepney, a poor district of the East End of London, and one with a strong Jewish community. Isaac Rosenberg attended St. Paul’s Primary School at Wellclose Square, St George in the East parish. Later, he went to the Baker Street Board School in Stepney, which had a strong Jewish presence. In 1902, he received a good conduct award and was allowed to take classes at the Arts and Crafts School in Stepney Green. In December 1904, he left the Baker Street School, and in January 1905, started an apprenticeship with Carl Hentschel, an engraver from Fleet Street. He became interested in both poetry and visual art, and started to attend evening classes at Birkbeck College. He withdrew from his apprenticeship in January 1911, as he had managed to find the finances to attend the Slade School of Fine Art at University College, London (UCL). During his time at Slade School, Rosenberg notably studied alongside David Bomberg, Mark Gertler, Stanley Spencer, Paul Nash, Edward Wadsworth, Dora Carrington, William Roberts, and Christopher Nevinson. He was taken up by Laurence Binyon and Edward Marsh, and began to write poetry seriously, but he suffered from ill-health. He published a pamphlet of ten poems, Night and Day, in 1912. He also exhibited paintings at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1914. Afraid that his chronic bronchitis would worsen, Rosenberg hoped to cure himself by relocating in 1914 to the warmer climate of South Africa, where his sister Mina lived in Cape Town. The Jewish Educational Aid Society of London helped by paying the fare. After arriving in Cape Town in the end of June 1914, he composed a poem On Receiving News of the War. While many wrote about war as patriotic sacrifice, Rosenberg was critical of it from the onset. However, feeling better and hoping to find employment as an artist in Britain, Rosenberg returned home in March 1915. He published a second collection of poems, Youth and then after being unable to find a permanent job enlisted in the British Army at the end of October 1915. He asked that half of his pay was sent to his mother. In a personal letter, Rosenberg described his attitude towards war, “I never joined the army for patriotic reasons. Nothing can justify war. I suppose we must all fight to get the trouble over.” First World War Rosenberg was assigned to the 12th Bantam Battalion of the Suffolk Regiment, a bantam being a designation for men under the usual minimum height of 5'3". After turning down an offer to apply for a commission to become a lance corporal, Rosenberg was transferred, first, to the South Lancashire Regiment, then, to the The King’s Own Royal Lancaster Regiment. In June 1916, he was sent with his unit to serve on the Western Front in France, where he arrived on the 3rd of June. He continued to write poetry while serving in the trenches, including Break of Day in the Trenches, Returning we Hear the Larks, and Dead Man’s Dump. In December 1916, the Poetry Magazine published his two poems. In January 1917, Rosenberg reported sick and his family and friends asked his superiors to remove him from the front lines; he was transferred to the Fortieth Division Works Battalion and started to deliver barbed wire to the trenches. He wrote his poem Dead Man’s Dump during this period. In June, he was temporarily assigned to the 229 Field Company, Royal Engineers. In September 1916, he spent ten days in London on leave. After returning to his old unit, he fell sick in October and spent two months in the 51st General Hospital. After release, he was transferred to the 1st Battalion of King’s Own Royal Regiment (KORL). He applied for a transfer to the one of all-Jewish battalions formed in Mesopotamia, but historians have been unable to track his application. On March 21, 1918, the German Army started its Spring offensive on the Western Front. A week later, Rosenberg sent his last letter with a poem Through these Pale Cold Days to England before going to the front lines with reinforcements. Having just finished night patrol, he was killed on the night of the April 1, 1918 with another 10 KORL’s soldiers; there is a dispute as to whether his death occurred at the hands of a sniper or in close combat. In either case, he died in a town called Fampoux, north-east of Arras. He was first buried in a mass grave, but in 1926, the unidentified remains of the six KORL’s soldiers were individually re-interred at Bailleul Road East Cemetery, Plot V, Saint-Laurent-Blangy, Pas de Calais, France. The Rosenberg’s gravestone is marked with his name and the words, “Buried near this spot”, as well as—"Artist and Poet". Legacy His self-portraits hang in the National Portrait Gallery and Tate Britain. A commemorative blue plaque to him hangs outside the Whitechapel Gallery, formerly the Whitechapel Library, which was unveiled by Anglo-Jewish writer Emanuel Litvinoff. On 11 November 1985, Rosenberg was among 16 Great War poets who were commemorated on a slate stone unveiled in Westminster Abbey’s Poet’s Corner. The inscription on the stone was written by a fellow Great War poet, Wilfred Owen. It reads: “My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity.” Rosenberg appears in the novel Grosse Fugue by Ian Phillips. In The Great War and Modern Memory, Paul Fussell’s landmark study of the literature of the First World War, Fussell identifies Rosenberg’s “Break of Day in the Trenches” as “the greatest poem of the war.” References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isaac_Rosenberg

Theodore Goodridge Roberts (July 7, 1877– February 24, 1953) was a Canadian novelist and poet. He was the author of thirty-four novels and over one hundred published stories and poems. He was the brother of poet Charles G.D. Roberts, and the father of painter Goodridge Roberts. Life He was born George Edwards Theodore Goodridge Roberts in Fredericton, to Emma Wetmore Bliss and Anglican Rev. George Goodridge Roberts. The poet Charles G.D. Roberts, and the writers William Carman Roberts and Jane Roberts MacDonald, were his siblings. He published his first poem in 1899, when he was eleven, in the New York Independent (where his cousin Bliss Carman was working), and his first prose piece (a comparison of the Battle of Waterloo and the Battle of Gettysburg) in the Century two years later. Roberts attended Fredericton Collegiate School, though (since school records were lost in a fire) the exact years are unknown. He later went to University of New Brunswick (UNB), but left without graduating. He published poetry in UNB’s University Magazine. In 1897 he moved to New York City, living with his brothers Charles and William and working at The Independent. In 1898 the magazine sent him to Cuba, as a special correspondent, to cover the Spanish–American War. While on the island he contracted malaria—he was sent back to New York and consulted specialists, who sent him back to Fredericton “to die.” An unnamed surgeon saved Roberts’s life, and he was nursed back to heath by Frances Seymour Allen (whom he would subsequently marry). The next year he travelled to Newfoundland, where he helped to found and edit The Newfoundland Magazine. He published his first book of poetry (Northand Lyrics, an anthology edited by Charles G.D. Roberts and featuring his three siblings) in 1899, and his first novel, The House of Isstens, in 1900. In 1901 Roberts sailed on a barkentine to Brazil. In 1902 he returned to Fredericton and briefly edited a second magazine, The Kit-Bag. Roberts married Frances Seymour Allen in November 1903, and they had a two-year honeymoon in Barbados where their first child was born. They would have four children: William Goodridge, Dorothy Mary Gostwick, Theodora Frances Bliss and Loveday (who died as an infant). Roberts averaged three novels a year from 1908 until 1914. At that time his “many novels of adventure and romance” already enoyed a “wide popularity in English-speaking lands.” A former militiaman, Roberts re-enlisted in 1914 when World War I broke out, serving as a lieutenant in the 12th Canadian Infantry Battalion, commanded by Lt.-Col. Harry Fulton McLeod of Fredericton—Roberts’ entire family followed him to England. When the 12th Battalion was assigned to a reserve and training roll in early 1915, Roberts was transferred to a position perhaps better fitted to his combination of military knowledge and literary skill. "In the summer of 1915, he was transferred to the Canadian War Records Office at the request of Max Aitken, Lord Beaverbrook. Roberts wrote official reports and battlefield accounts and published three works in collaboration with others." He was promoted captain early in 1916. When Roberts was in Europe he left his manuscripts and papers, including work not yet published, with a Dr. Wainwright in Saint John, who stored them in his basement. They were destroyed in the spring of 1919 when the Saint John River flooded. In 1929 Roberts wrote a weekly column for the Saint John Telegraph-Journal, “Under the Sun.” From April through September 1930 he edited another small magazine, Acadie. In 1932 he undertook his last major sea cruise, sailing through the Panama Canal to Vancouver and back. The same year he did a cross-Canada reading tour, which “culminated with festivities in Vancouver.” Roberts moved to Toronto in 1935, and in 1937 briefly edited another magazine, Spotlight. In 1939 he relocated to Aylmer, Quebec, where he briefly founded another magazine, Swizzles. He returned to New Brunswick in 1941, and in 1945 moved to Digby, Nova Scotia, where he would die eight years later. He is buried beside Charles G.D. Roberts and Bliss Carman in Fredericton’s Forest Hill Cemetery. Writing The Dictionary of Literary Biography (DLB) says that T.G. Roberts’s “poetry and fiction, staggering in sheer quantity and variety, show at their best Roberts’s most enduring gifts: in his poetry a love of nature well served by a keen eye for local color and detail, a good ear for clean, clear rhythm and rhyme, and a forceful, uncluttered narrative line; and in fiction a talent for presenting his abiding perception of universal struggles between good and evil either in mythic tales of adventure or in regional stories animated by local settings, customs, and dialects.” Of the poems in his 1926 collection, The Lost Shipmate, The Encyclopedia of Literature commented: "Had this volume appeared forty years earlier it might have won for Theodore a reputation equal to that of his brother Charles or of Bliss Carman. Poems such as ‘The sandbar’ and ‘Magic’ are unmatched in Canadian poetry for a facility and clarity of image suggestive of high-realist painting. However, much of what Roberts wrote has been forgotten with time, or has not stood the tests of time and changing fashion. The Merriest Knight The writing that Roberts is most likely to be recognized for today is The Merriest Knight, his collection of Arthurian tales. This looks like the one book by Roberts currently in print - ironically, considering that it was never published as a book during Roberts’s lifetime. Roberts began to write Arthurian fiction in the 1920s; most of these stories, though, were published in the late 1940s and early 1950s in the fiction magazine Blue Book. Roberts planned to publish them as a collection, but died in 1953 before he could do so. In 2001 Mike Ashley, editor of the Mammoth publishing group, brought them out under his Green Knight imprint. A review for SFSite called the collection’s writing “polished,” “erudite,” and “eminently readable,” but “somewhat tame”: “literature for the afternoon tea and crumpets crowd– in a word 'polite’ Arthurian fiction.” Still, it concluded, “if you’re looking for something a bit more upbeat, some Arthuriana-lite, The Merriest Knight is just the book for you.” Recognition The University of New Brunswick awarded Roberts a Doctorate of literature in 1930. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada in 1934. Publications Fiction * The House of Isstens. Boston: L.C. Page, 1900. * Hemming the Adventurer. Boston: L.C. Page, 1904. * Brothers in Peril: A Story of Old Newfoundland, 1905. Boston: L.C. Page & Company, 1905. * Red Feathers: a story of remarkable adventures when the world was young. Boston: L.C. Page, 1907. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. ISBN 978-0-7710-9227-5 * Captain Love. Boston: L.C. Page & Company, 1908. * Flying Plover: His Stories, Told Him by Squat-by-the-Fire. Boston: L.C. Page, 1909. * A Cavalier of Virginia: a romance. Chicago: M.A. Donohue, 1910. * Comrades of the Trails. Boston: L.C. Page & Company, 1910. * Love on a Smokey River. 1911. * A Captain of Raleigh’s: a romance. Boston: L.C. Page & Company, 1911. * A Soldier of Valley Forge. with Robert Neilson Stephens. Boston: L.C. Page, 1911. * Blessington’s Folly. London: John Long, 1912. * Rayton: a backwoods mystery. Boston: L.C. Page, 1912. * The Harbor Master. Chicago: M.A. Donohue, 1913. * Two Shall Be Born. New York: Cassell, 1913. * The Wasp. Toronto: Bell & Cockburn, 1914. * The Toll of the Tides. 1914. * In the High Woods. London: John. Long, 1916. * Forest Fugitives. Toronto: McClelland, Goodchild & Stewart, 1917. * The Islands of Adventure. London; Toronto: Hodder and Stoughton, 1918. * Jess of the River. London: John Long, 1918. * The Exiled Lover. London: John Long, 1919. * Honest Fool. New York: F.A. Munsey, 1925. * The Master of the Moosehorn and Other Backwoods Stories. London; Toronto: Hodder and Stoughton, 1919. * Moonshine. London: Hodder and Stoughton, [1920?]. * The Lure of Piper’s Glen. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Page, 1921. * The Fighting Starkleys. George Varian illus. Boston: Page, 1922. * Musket House. 1922. * Tom Akerley: his adventures in the tall timber and at Gaspard’s clearing on the Indian River. Boston: L.C. Page, 1923. * Green Timber Thoroughbreds. New York: Garden City, 1924. * The Stranger from Up-Along. Garden City, NJ: Doubleday, Page & co., 1924. * The Red Pirogue: a tale of adventure in the Canadian wilds. Boston: L.C. Page, 1924. * The Oxford Wizard. Garden City, NY: Garden City Pub., 1924. * The Lost Shipmate. Toronto: Ryerson, 1926. * The Golden Highlanders. Boston: L.C. Page, 1929. * The Merriest Knight: The Collected Arthurian Tales of Theodore Goodridge Roberts. Mike Ashley ed. Green Knight, 2001. ISBN 978-1-928999-18-8 Non-fiction * Patrols and Trench Raids. 1916. * Battalion Histories. 1918. * Thirty Canadian V.Cs 23rd April 1915 to 30th March 1918, with Robin Richards and Stuart Martin. London: Skeffington, 1918. * Loyalists: a compilation of histories, biographies and genealogies of United empire loyalists and their descendants. Toronto: T. Goodridge Roberts, 1937. Poetry * Northland Lyrics, William Carman Roberts, Theodore Roberts & Elizabeth Roberts Macdonald; selected and arranged with a prologue by Charles G.D. Roberts and an epilogue by Bliss Carman. Boston: Small, Maynard & Co., 1899. ISBN 0-665-12501-1 * Seven Poems. private, 1925. chapbook. * The Lost Shipmate. Toronto: Ryerson Chapbook, 1926. * The Leather Bottle. Toronto: Ryerson, 1934. * That Far River: Selected Poems of Theodore Goodridge Roberts. Martin Ware, ed. London, ON: Canadian Poetry Press, 1998. * Except where noted, bibliographical information courtesy St. Thomas University. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theodore_Goodridge_Roberts

I think my poetry sums me up pretty well. It's full of emotion that I was feeling in that particular moment in time. I will never claim to be a writer or a poet, but I do enjoy writing poetry nonetheless. Writing, amongst other things, has been a form of escape for me. I used to keep anything I wrote to myself and never shared it except with a few persons of my choosing. I'm still a bit uncertain to share it now but I figured, why not share it? I feel as though writing is a form of release, it is for me personally anyway. So I encourage you to try it out, at least once. I'm not going to sit here and type out every detail of my life or even share much of my story with you at all. I think what I share with you in my poetry will suffice. No, my life hasn't been an easy or smooth ride, but who's life has been? I started writing from a very young age, basically since I knew how to put letters together to form words. I'm not the best, I will misspell words, use incorrect punctuation, but I'm not writing to impress and I'm not looking for people to flaunt over what I write or say cruel things about it either. But, if you enjoy them I greatly appreciate it, and if you have constructive criticism, I welcome it. Ultimately though, I chose to share my poetry for the slight chance it could impact someone or help them to know they're not the only one with pain trapped inside of them. It's for those people who think "that's exactly how I feel right now." Because I know how much it effects me when I read a quote or poem or hear a song that explains exactly the way I'm feeling. Somehow it helps knowing I'm not alone in my lonely despair. My words are in no way anything to brag about and can even be a bit dark at times. I understand that my style will not be for everyone and that's okay, you by no means have to read it. But if you do find some enjoyment in them, I very much appreciate it.

Lizette Woodworth Reese (January 9, 1856– December 17, 1935) was an American poet. Reese was born in the Waverly section of Baltimore, Maryland to Louisa Gabler and David Reese. She also had a twin sister named Sophia. Educated in Baltimore’s public schools, Reese graduated from Eastern High School (Baltimore), where a memorial for her stands today. After graduation, she became a school teacher at St. John’s Parish School in 1873. The following year, Reese published her first poem, “The Deserted House,” in Southern Magazine. She continued to publish in various magazines until her first self-published anthology, A Branch of May, in 1887. Subsequent books followed in 1891 and 1896, A Handful of Lavender and A Quiet Road, respectively. During the late 1890s and early 1900s, Reese wrote infrequently. However, her sonnet, “Tears,” published in Scribner’s Magazine in 1899, garnered her praise and recognition, particularly from fellow Baltimore writer, H. L. Mencken, who stated that Reese’s work was “one of the imperishable glories of American literature." In 1918, Reese retired from teaching after having worked her last few years at Western High School (Baltimore). In 1931, Reese was named poet laureate of Maryland by the General Federation of Women’s Clubs. She was also honorary president of thee Poetry Society of Maryland and co-founder of the Women’s Literary Club of Baltimore. Reese died on December 17, 1935. She is buried at the St. John’s Episcopal Church. After her death, Reese’s friend and sculptor, Grace Turnbull was commissioned to create a monument to her work. The marble statue, entitled “The Good Shepherd” stands on the old grounds of Eastern High School, Reese’s alma mater, in Waverly.

Hey y'all! I'm Samantha, I am 22 years old and getting ready to graduate from LSU. When it comes to writing my passion is poetry. I have been writing poems since my freshman year of high school. Poetry is my escape and my way of venting. I love to travel! My dream job would be to write for a travel magazine and this way I could travel the rest of my life and experience all the world has to offer. Not only have a posted a few of my poems, but I have written and posted some of my travel pieces from my recent trip to Europe. I hope y'all enjoy reading my work!

Carl Rakosi (November 6, 1903– June 25, 2004) was the last surviving member of the original group of poets who were given the rubric Objectivist. He was still publishing and performing his poetry well into his 90s. Early life Rakosi was born in Berlin and lived there and in Hungary until 1910, when he moved to the United States to live with his father and stepmother. His father was a jeweler and watchmaker in Chicago and later in Gary, Indiana. The family lived in semi-poverty but contrived to send him to the University of Chicago and then to the University of Wisconsin–Madison. During his time studying at the university level, he started writing poetry. On graduating, he worked for a time as a social worker, then returned to college to study psychology. At this time, he changed his name to Callman Rawley because he felt he stood a better chance of being employed if he had a more American-sounding name. After a spell as a psychologist and teacher, he returned to social work for the rest of his working life. Early writings At the University of Wisconsin–Madison, Rakosi edited the Wisconsin Literary Magazine. His own poetry at this stage was influenced by W. B. Yeats, Wallace Stevens, and E. E. Cummings. He also started reading William Carlos Williams and T. S. Eliot. By 1925, he was publishing poems in The Little Review and Nation. Pound and the Objectivists By the late 1920s, Rakosi was in correspondence with Ezra Pound, who prompted Louis Zukofsky to contact him. This led to Rakosi’s inclusion in the Objectivist issue of Poetry and in the Objectivist Anthology. Rakosi himself had reservations about the Objectivist tag, feeling that the poets involved were too different from each other to form a group in any meaningful sense of the word. He did, however, especially admire the work of Charles Reznikoff. Later career Like a number of his fellow Objectivists, Rakosi abandoned poetry in the 1940s. After his 1941 Selected Poems he dedicated himself to social work and apparently neither read nor wrote poetry. Years earlier, shortly after his twenty-first birthday, Rakosi had legally changed his name to Callman Rawley, believing that he would not find work with his foreign-sounding name. Under his adopted name, he served as head of the Minneapolis Jewish Children’s and Family Service from 1945 until his retirement in 1968. A letter from the English poet Andrew Crozier about his early poetry was the trigger that started Rakosi writing again. His first book in 26 years, Amulet, was published by New Directions in 1967 and his Collected Poems in 1986 by the National Poetry Foundation. These were followed by several more volumes and by readings across the United States and Europe. In early November 2003, Rakosi celebrated his 100th birthday with friends at the San Francisco Public Library. Upon his death Jacket Magazine editor John Tranter observed the following: Poet Carl Rakosi died on Friday afternoon June 25 at the age of 100, after a series of strokes, in his home in San Francisco. My wife Lyn and I were passing through California in November 2003, and we stopped by to have a coffee with Carl at his home in Sunset. By a lucky coincidence, it happened to be his 100th birthday. He was, as always, kind, thoughtful, bright and alert, and as sharp as a pin. We felt privileged to know him. External links Rakosi at Modern American Poetry The Carl Rakosi Papers in the Mandeville Special Collections Library at UC San Diego Carl Rakosi Reading and Interview on KPFA’s Ode To Gravity, 13 May 1971 (from The Internet Archive) Obituary in The Guardian, UK Carl Rakosi feature at Jacket Magazine includes Rakosi in conversation with Tom Devaney & Olivier Brossard; link to audio recordings at University of Pennsylvania, and poems, dedications & remembrances from Jane Augustine, Robert Creeley, Laurie Duggan, Michael Heller and Kent Johnson “Add-Verse” a poetry-photo-video project Rakosi participated in References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carl_Rakosi

Alastair Reid (Whithorn, 22 March 1926 – Manhattan, 21 September 2014) was a Scottish poet and a scholar of South American literature. He was known for his lighthearted style of poems and for his translations of South American poets Jorge Luis Borges and Pablo Neruda. Although he was known for translations, his own poems had gained notice during his lifetime. He had lived in Spain, Switzerland, Greece, Morocco, Argentina, Mexico, Chile, the Dominican Republic, and in the United States. During the editorship of William Shawn he wrote for The New Yorker magazine, but his main income was from teaching. Reid was born at Whithorn in Galloway, Scotland, the son of a clergyman. During the Second World War he served in the Royal Navy decoding ciphers. After the war he studied Classics at the University of St Andrews and briefly taught Classics at Sarah Lawrence College, New York. In the mid-1950s he travelled to Mallorca, spending some time working as the secretary of Robert Graves. In 1984, in an interview for the Wall Street Journal, Reid admitted fabricating many details of his reporting from Spain for the New Yorker, including inventing places and ascribing statements to composite characters. He said these inventions were an attempt to present "a larger truth, of which facts form a part."[2] In his book, Whereabouts, Reid counters this article with the following: These pieces were at the center of a curious storm that blew up in the American press during June of 1984. A year or so before, I had addressed a seminar at Yale University on the wavering line between fact and fiction, using examples from various writers, Borges among them, and from my own work. A student from the seminar went on to become a reporter and published a piece in the Wall Street Journal that charged me with having made a practice of distorting facts, quoting the cases I had cited in the seminar. Many newspaper editorials took up the story as though it were fact, and used it to wag pious fingers at the New Yorker. A number of columnists reproved me for writing about an "imaginary" Spanish village, a charge that would have delighted the flesh-and-blood inhabitants.... Not a single one of my critics, as far as I could judge, had gone back to read the pieces in question. He published more than forty books of poems, translations, and travel writing, including Ounce Dice Trice, a book of word-play for children (illustrated by Ben Shahn), and two selections from his works: Outside In: Selected Prose and Inside Out: Selected Poetry and Translations (both 2008). During the 1980s and 1990s he spent much of his time on a ginger plantation in Samaná, Dominican Republic, until 2003 when tourism boomed in the area. Reid died on 21 September 2014, aged 88, due to a gastric bleed during treatment for pneumonia. References Wikipedia—http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alastair_Reid

William Harris Lloyd Roberts (31 October 1884– 28 June 1966) was a Canadian writer, poet, and playwright. He was born in Fredericton, New Brunswick, the son of noted Canadian poet Charles George Douglas Roberts and Mary Isabel Fenety. After an education by private tutors, he attended King’s Collegiate School then, in 1905, Fredericton High School. In 1903 he performed clerical work at McClure’s magazine. From 1904 until 1907 he was an assistant editor at the Outing magazine, based in New York City. He wrote short stories and poetry for various magazines, plus performing part-time newspaper work starting in 1911. On January 1, 1914, he was married to Helen Hope Farquhar Bolmain. The couple had a daughter, Patricia Bliss, before Helen died. In 1912, he became editor of immigration literature for the Canadian Department of Interior in Ottawa. Two years later, he served as a correspondent for the Timer and Grazing branch of the Interior Department in Ottawa. On August 15, 1914, he married his second wife, Lila White; the couple divorced shortly thereafter. After 1920 he retired from work in order to devote all of his time to writing fiction, drama, poetry, and special articles. From 1925 until 1939 he was a correspondent for the Christian Science Monitor, then he performed public relations for the Royal Canadian Mounted Police up to 1945. His third marriage in 1943 was to Julia Bristow, and they would have two daughters. Bibliography * England Over Seas (1914) * Come Quietly, Britain (1915) * Mother Doneby (1916) * The Book of Roberts (1923) * Along the Ottawa (1927) * I Sing of Life (1937) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Harris_Lloyd_Roberts

I'm young in age but my soul is wise and carries many messages that I hope you take the time to listen to. Music and other poets are my main source of inspiration but I'm still very capable of gaining inspiration from the small things like the way the grass wavers in the wind or how rain drops cling to my eyelashes when I'm dancing in the rain. I was born to create and words flow through my veins and impatiently rest beneath my tongue aching to be heard. My poems are cathartic and self healing but they often connect with others and help others as well. I enjoy writing for others and being their voice to portray how they feel when they lack the words needed. I live to write and I write to live. I want to improve and have constructive criticism, but compliments also help out and make me feel appreciated :)

Agnes Ethelwyn Wetherald was born of English-Quaker parents at Rockwood, Ontario, April 26th, 1857. Her father was the late Rev. William Wetherald, who founded the Rockwood Academy about the middle of the last century, and was its principal for some years. He was a lover of good English, spoken and written, and his talented daughter has owed much to his careful teaching. He was the teacher whom the late James J. Hill, the railway magnate, had held in such grateful remembrance. Additional education was received by Miss Wetherald at the Friends' Boarding School, Union Springs, N.Y., and at Pickering College. Miss Wetherald began the writing of poetry later in life than most poets and her first book of verse, The House of the Trees and Other Poems, did not appear until 1895. This book at once gave her high rank among women poets. Prior to this, she had collaborated with G. Mercer Adam on writing and publishing a novel, An Algonquin Maiden, and had conducted the Woman's Department in The Globe, Toronto, under the nom de plume, 'Bel Thistlewaite.' In 1902, appeared her second volume of verse, Tangled in Stars, and, in 1904, her third volume, The Radiant Road. In the autumn of 1907, a collection of Miss Wetherald's best poems was issued, entitled, The Last Robin: Lyrics and Sonnets. It was warmly welcomed generally, by reviewers and lovers of poetry. The many exquisite gems therein so appealed to Earl Grey, the then Governor-General of Canada, that he wrote a personal letter of appreciation to the author, and purchased twenty-five copies of the first edition for distribution among his friends. For years Miss Wetherald has resided on the homestead farm, near the village of Fenwick, in Pelham Township, Weland county, Ontario, and there in the midst of a large orchard and other rural charms, has dreamed, and visioned, and sung, pouring out her soul in rare, sweet songs, with the naturalness of a bird. And like a bird she has a nest in a large willow tree, cunningly contrived by a nature-loving brother, where her muse broods contentedly, intertwining her spirit with every aspect of the beautiful environment.

I'm from Jersey City, New Jersey, currently a full time student at NJCU obtaining a degree in English and Secondary Education. I love poetry and see it as an escape. I'm a fan of the arts, I love reading work that others produce, and I love what I do. Anyone hosting open mics in the area, let me know. Thanks! Other than that, I'm 23, passionate about poetry, in love with a wonderful woman, and have big plans for the future. I hope you enjoy my work. Follow me, share me, tell me what you think!

I'm just another person trying to spread this art in the form of words to convey an imagine that can't be seen but only heard. Don't expect a traditional poem cause my writing has no structure Hope you enjoy reading my work, please feel free to leave comments good or bad! I would love to hear what you all think of it.

The author was born in México City, in 1964; He graduated from the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México as an Orthopaedic Surgeon. His passions are, his children: Nadezda, Bruno, and his mother: Inés, to who he dedicates most of his time. About his affections: anthropology, world's history, science fiction, to enjoy a nice and spicy meal with a fine cigar, rock music... The Beatles!, gardening, to take a long afternoon walking and sports. His heroes are John Winston Ono Lennon, Vincent Van Gogh... And James Tiberius Kirk. “Life is too short to live with fear about feelings... I wish I could turn back time, to let know those who have left us, that in my life... I loved them.”

I'm 19 years old. I've been writing poetry for about 3-4 years. I do post my poems on another site called 'Booksie'. I'm just looking for another place to post my poetry and get more feedback. I'm a very loving, and caring person. I have a very open heart, so I tend to get hurt quite easily and I never learn from it.

Hello my name is Abby! I'm a very interesting person. Apparently I have a lot of energy to where I make a pot of coffee nervous. I'm very artistic and outgoing. I love CATS absolutely and I recently just got married to my best friend and it's been wonderful! I'm hoping to see the world one day. Great thing is my husband is in the US Airforce. Poetry has been great therapy to me during the good times and the bad times. My strongest points in poetry is actually during the bad times. Although those moments were the strongest moments in my life. It simply was easier for words to flow out of my pen. Poetry is beautiful and I just love the symbolism and words people use to describe events, feelings, or things. I'm just glad to be a part of it and to use my creativity. I hope that you enjoy reading my poetry just as much as I've enjoyed writing them!

I'm a singer songwriter from North Wales and maybe at times a Poet :) My real passion is writing, music and guitar. I've traveled quite a lot over the last 2 years to gain inspiration and I'm trying to grow all the time. I can't imagine my life without writing and music and I always write from the heart.

Born and raised in Limpopo by a single parent.Went to 5 different schools in my life.I have one little sister and a few friends.i absolutely enjoy poetry and music,im a debator and i see the world in a different perspective from most people.Im 19years old and i completed high school 2012.im currently in Tertiary studying electrical engineering.

i am just a girl. I am just another human trying to succeed and hoping that one day i will. The only difference between me and you is that i have the will to get up and do it, and i want to encourage others to do the same. If you like my writing please share my page and get your friends to read them too. I hope that my writing helps each any everyone who chooses to read it, and i want to thank those of you who actually do wish to spend their time doing so.

.jpg)