Info

Richard Gary Brautigan (January 30, 1935 – ca. September 16, 1984) was an American novelist, poet, and short story writer. His work often employs black comedy, parody, and satire. He is best known for his 1967 novel Trout Fishing in America. Brautigan was born in Tacoma, Washington, the only child of Bernard Frederick “Ben” Brautigan, Jr., a factory worker and laborer, and Lulu Mary “Mary Lou” Keho, a waitress. In 1984, at age 49, Richard Brautigan had moved to Bolinas, California, where he was living alone in a large, old house that he had bought with his earnings years earlier. He died of a self-inflicted .44 Magnum gunshot wound to the head.

Joseph Hilaire Pierre René Belloc (27 July 1870 – 16 July 1953) was an Anglo-French writer and historian. He was one of the most prolific writers in England during the early twentieth century. He was known as a writer, orator, poet, sailor, satirist, man of letters, soldier and political activist. His Catholic faith had a strong impact on his works. He was President of the Oxford Union and later MP for Salford from 1906 to 1910. He was a noted disputant, with a number of long-running feuds, but also widely regarded as a humane and sympathetic man. Belloc became a naturalised British subject in 1902, while retaining his French citizenship. His poetry encompassed comic verses for children and religious poetry. His widely sold Cautionary Tales for Children included “Jim, who ran away from his nurse, and was eaten by a lion” and “Matilda, who told lies and was burnt to death”. He also collaborated with G. K. Chesterton on a number of works.

Sir John Betjeman, CBE (28 August 1906 – 19 May 1984) was an English poet, writer, and broadcaster who described himself in Who’s Who as a “poet and hack”. He was Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom from 1972 until his death. He was a founding member of the Victorian Society and a passionate defender of Victorian architecture. He began his career as a journalist and ended it as one of the most popular British Poets Laureate and a much-loved figure on British television. Life Early life and education Betjeman was born “John Betjemann”. His parents, Mabel (née Dawson) and Ernest Betjemann, had a family firm at 34–42 Pentonville Road which manufactured the kind of ornamental household furniture and gadgets distinctive to Victorians. The family name was changed to the less German-looking “Betjeman” during the First World War. His father’s forebears had actually come from the present day Netherlands and had, ironically, added the extra –n during the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War to avoid the anti-Dutch sentiment existing at the time, more than a century earlier, setting up their home and business in Islington, London. Betjeman was baptised at St Anne’s Church, Highgate Rise, a 19th-century church at the foot of Highgate West Hill. The family lived at Parliament Hill Mansions in the Lissenden Gardens private estate in Gospel Oak in north London. In 1909, the Betjemanns moved half a mile north to more opulent Highgate. From West Hill they lived in the reflected glory of the Burdett-Coutts estate: “Here from my eyrie, as the sun went down, I heard the old North London puff and shunt, Glad that I did not live in Gospel Oak.” Betjeman’s early schooling was at the local Byron House and Highgate School, where he was taught by poet T. S. Eliot. After this, he boarded at the Dragon School preparatory school in North Oxford and Marlborough College, a public school in Wiltshire. In his penultimate year, he joined the secret Society of Amici in which he was a contemporary of both Louis MacNeice and Graham Shepard. He founded The Heretick, a satirical magazine that lampooned Marlborough’s obsession with sport. While at school, his exposure to the works of Arthur Machen won him over to High Church Anglicanism, a conversion of importance to his later writing and conception of the arts. Magdalen College, Oxford Betjeman entered the University of Oxford with difficulty, having failed the mathematics portion of the university’s matriculation exam, Responsions. He was, however, admitted as a commoner (i.e. a non-scholarship student) at Magdalen College and entered the newly created School of English Language and Literature. At Oxford, Betjeman made little use of the academic opportunities. His tutor, a young C. S. Lewis, regarded him as an “idle prig” and Betjeman in turn considered Lewis unfriendly, demanding, and uninspired as a teacher. Betjeman particularly disliked the coursework’s emphasis on linguistics, and dedicated most of his time to cultivating his social life and his interest in English ecclesiastical architecture, and to private literary pursuits. At Oxford he was a friend of Maurice Bowra, later (1938 to 1970) to be Warden of Wadham. Betjeman had a poem published in Isis, the university magazine, and served as editor of the Cherwell student newspaper during 1927. His first book of poems was privately printed with the help of fellow student Edward James. He famously brought his teddy bear Archibald Ormsby-Gore up to Magdalen with him, the memory of which inspired his Oxford contemporary Evelyn Waugh to include Sebastian Flyte’s teddy Aloysius in Brideshead Revisited. Much of this period of his life is recorded in his blank verse autobiography Summoned by Bells published in 1960 and made into a television film in 1976. It is a common misapprehension, cultivated by Betjeman himself, that he did not complete his degree because he failed to pass the compulsory holy scripture examination, known colloquially as “Divvers”, short for “Divinity”. In Hilary term 1928, Betjeman failed Divinity for the second time. He had to leave the university for the Trinity term to prepare for a retake of the exam; he was then allowed to return in October. Betjeman then wrote to the Secretary of the Tutorial Board at Magdalen, G. C. Lee, asking to be entered for the Pass School, a set of examinations taken on rare occasions by undergraduates who are deemed unlikely to achieve an honours degree. In Summoned by Bells Betjeman claims that his tutor, C. S. Lewis, said “You’d have only got a third”– but he had informed the tutorial board that he thought Betjeman would not achieve an honours degree of any class. Permission to sit the Pass School was granted. Betjeman famously decided to offer a paper in Welsh. Osbert Lancaster tells the story that a tutor came by train twice a week (first class) from Aberystwyth to teach Betjeman. However, Jesus College had a number of Welsh tutors who more probably would have taught him. Betjeman finally had to leave at the end of the Michaelmas term, 1928. Betjeman did pass his Divinity examination on his third try but was 'sent down’ after failing the Pass School. He had achieved a satisfactory result in only one of the three required papers (on Shakespeare and other English authors). Betjeman’s academic failure at Oxford rankled with him for the rest of his life and he was never reconciled with C.S. Lewis, towards whom he nursed a bitter detestation. This situation was perhaps complicated by his enduring love of Oxford, from which he accepted an honorary doctorate of letters in 1974. After university Betjeman left Oxford without a degree. Whilst there, however, he had made the acquaintance of people who would later influence his work, including Louis MacNeice and W. H. Auden. He worked briefly as a private secretary, school teacher and film critic for the Evening Standard, where he also wrote for their high-society gossip column, the Londoner’s Diary. He was employed by the Architectural Review between 1930 and 1935, as a full-time assistant editor, following their publishing of some of his freelance work. Timothy Mowl (2000) says, “His years at the Architectural Review were to be his true university”. At this time, while his prose style matured, he joined the MARS Group, an organisation of young modernist architects and architectural critics in Britain. Betjeman’s sexuality can best be described as bisexual, and his longest and best documented relationships were with women, and a fairer analysis of his sexuality may be that he was “the hatcher of a lifetime of schoolboy crushes– both gay and straight”, most of which progressed no further. Nevertheless, he has been considered “temperamentally gay”, and even became a penpal of Lord Alfred 'Bosie’ Douglas of Oscar Wilde fame. On 29 July 1933 he married the Hon. Penelope Chetwode, the daughter of Field Marshal Lord Chetwode. The couple lived in Berkshire and had a son, Paul, in 1937, and a daughter, Candida, in 1942. In 1937, Betjeman was a churchwarden at Uffington, the Berkshire town (since relocated to Oxfordshire) where he lived. That year, he paid for the cleaning of the church’s royal arms and later presided over the conversion of the church’s oil lamps to electricity. The Shell Guides were developed by Betjeman and Jack Beddington, a friend who was publicity manager with Shell-Mex Ltd, to guide Britain’s growing number of motorists around the counties of Britain and their historical sites. They were published by the Architectural Press and financed by Shell. By the start of World War II 13 had been published, of which Cornwall (1934) and Devon (1936) were written by Betjeman. A third, Shropshire, was written with and designed by his good friend John Piper in 1951. In 1939, Betjeman was rejected for active service in World War II but found war work with the films division of the Ministry of Information. In 1941 he became British press attaché in neutral Dublin, Ireland, working with Sir John Maffey. He may have been involved with the gathering of intelligence. He is reported to have been selected for assassination by the IRA. The order was rescinded after a meeting with an unnamed Old IRA man who was impressed by his works. Betjeman wrote a number of poems based on his experiences in “Emergency” World War II Ireland including "The Irish Unionist’s Farewell to Greta Hellstrom in 1922" (written during the war) which contained the refrain “Dungarvan in the rain”. The object of his affections, “Greta”, has remained a mystery until recently revealed to have been a member of a well-known Anglo-Irish family of Western county Waterford. His official brief included establishing friendly contacts with leading figures in the Dublin literary scene: he befriended Patrick Kavanagh, then at the very start of his career. Kavanagh celebrated the birth of Betjeman’s daughter with a poem “Candida”; another well-known poem contains the line Let John Betjeman call for me in a car. After World War II Betjeman’s wife Penelope became a Roman Catholic in 1948. The couple drifted apart and in 1951 he met Lady Elizabeth Cavendish, with whom he developed an immediate and lifelong friendship. By 1948 Betjeman had published more than a dozen books. Five of these were verse collections, including one in the USA. Sales of his Collected Poems in 1958 reached 100,000. The popularity of the book prompted Ken Russell to make a film about him, John Betjeman: A Poet in London (1959). Filmed in 35mm and running 11 minutes and 35 seconds, it was first shown on BBC’s Monitor programme. He continued writing guidebooks and works on architecture during the 1960s and 1970s and started broadcasting. He was a founder member of the Victorian Society (1958). Betjeman was closely associated with the culture and spirit of Metro-land, as outer reaches of the Metropolitan Railway were known before the war. In 1973 he made a widely acclaimed television documentary for the BBC called Metro-Land, directed by Edward Mirzoeff. On the centenary of Betjeman’s birth in 2006, his daughter led two celebratory railway trips: from London to Bristol, and through Metro-land, to Quainton Road. In 1974, Betjeman and Mirzoeff followed up Metro-Land with A Passion for Churches, a celebration of Betjeman’s beloved Church of England, filmed entirely in the Diocese of Norwich. In 1975, he proposed that the Fine Rooms of Somerset House should house the Turner Bequest, so helping to scupper the plan of the Minister for the Arts for a Theatre Museum to be housed there. In 1977 the BBC broadcast “The Queen’s Realm: A Prospect of England”, an aerial anthology of English landscape, music and poetry, selected by Betjeman and produced by Edward Mirzoeff, in celebration of the Queen’s Silver Jubilee. Betjeman was fond of the ghost stories of M.R. James and supplied an introduction to Peter Haining’s book M.R. James– Book of the Supernatural. He was susceptible to the supernatural. Diana Mitford tells the story of Betjeman staying at her country home, Biddesden House, in the 1920s. She says, “he had a terrifying dream, that he was handed a card with wide black edges, and on it his name was engraved, and a date. He knew this was the date of his death”. For the last decade of his life Betjeman suffered increasingly from Parkinson’s disease. He died at his home in Trebetherick, Cornwall on 19 May 1984, aged 77, and is buried nearby at St Enodoc’s Church. Poetry Betjeman’s poems are often humorous, and in broadcasting he exploited his bumbling and fogeyish image. His wryly comic verse is accessible and has attracted a great following for its satirical and observant grace. Auden said in his introduction to Slick But Not Streamlined, “so at home with the provincial gaslit towns, the seaside lodgings, the bicycle, the harmonium.” His poetry is similarly redolent of time and place, continually seeking out intimations of the eternal in the manifestly ordinary. There are constant evocations of the physical chaff and clutter that accumulates in everyday life, the miscellanea of an England now gone but not beyond the reach of living memory. He talks of Ovaltine and Sturmey-Archer bicycle gears. “Oh! Fuller’s angel cake, Robertson’s marmalade,” he writes, “Liberty lampshades, come shine on us all.” In a 1962 radio interview he told teenage questioners that he could not write about 'abstract things’, preferring places, and faces. Philip Larkin wrote of his work, "how much more interesting & worth writing about Betjeman’s subjects are than most other modern poets, I mean, whether so-and-so achieves some metaphysical inner unity is not really so interesting to us as the overbuilding of rural Middlesex". Betjeman was a practising Anglican and his religious beliefs come through in some of his poems. He combined piety with a nagging uncertainty about the truth of Christianity. Unlike Thomas Hardy, who disbelieved in the truth of the Christmas story while hoping it might be so, Betjeman affirms his belief even while fearing it might be false. In the poem “Christmas”, one of his most openly religious pieces, the last three stanzas that proclaim the wonder of Christ’s birth do so in the form of a question “And is it true...?” His views on Christianity were expressed in his poem “The Conversion of St. Paul”, a response to a radio broadcast by humanist Margaret Knight: Betjeman became Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom in 1972, the first Knight Bachelor to be appointed (the only other, Sir William Davenant, had been knighted after his appointment). This role, combined with his popularity as a television performer, ensured that his poetry reached an audience enormous by the standards of the time. Similarly to Tennyson, he appealed to a wide public and managed to voice the thoughts and aspirations of many ordinary people while retaining the respect of many of his fellow poets. This is partly because of the apparently simple traditional metrical structures and rhymes he uses. In the early 1970s, he began a recording career of four albums on Charisma Records which included Betjeman’s Banana Blush (1974) and Late Flowering Love (1974), where his poetry reading is set to music with overdubbing by leading musicians of the time. His recording catalogue extends to nine albums, four singles and two compilations. Betjeman and architecture Betjeman had a fondness for Victorian architecture and was a founding member of the Victorian Society. He wrote on this subject in First and Last Loves (1952) and more extensively in London’s Historic Railway Stations in 1972, defending the beauty of twelve stations. He led the campaign to save Holy Trinity, Sloane Street in London when it was threatened with demolition in the early 1970s. He fought a spirited but unsuccessful campaign to save the Propylaeum, known commonly as the Euston Arch, London. He is considered instrumental in helping to save St Pancras railway station, London, and was commemorated when it became an international terminus for Eurostar in November 2007. He called the plan to demolish St Pancras a “criminal folly”. About it he wrote, "What [the Londoner] sees in his mind’s eye is that cluster of towers and pinnacles seen from Pentonville Hill and outlined against a foggy sunset, and the great arc of Barlow’s train shed gaping to devour incoming engines, and the sudden burst of exuberant Gothic of the hotel seen from gloomy Judd Street.” On the reopening of St Pancras station in 2007, a statue of Betjeman was commissioned from curators Futurecity. A proposal by artist Martin Jennings was selected from a shortlist. The finished work was erected in the station at platform level, including a series of slate roundels depicting selections of Betjeman’s writings. Betjeman was given the remaining two-year lease on Victorian Gothic architect William Burges’s Tower House in Holland Park upon leaseholder Mrs E.R.B. Graham’s death in 1962. Betjeman felt he could not afford the financial implications of taking over the house permanently, with his potential liability for £10,000 of renovations upon the expiration of the lease. After damage from vandals, restoration began in 1966. Betjeman’s lease included furniture from the house by Burges, and Betjeman gave three pieces, the Zodiac settle, the Narcissus washstand, and the Philosophy cabinet, to Evelyn Waugh. Betjeman responded to architecture as the visible manifestation of society’s spiritual life as well as its political and economic structure. He attacked speculators and bureaucrats for what he saw as their rapacity and lack of imagination. In the preface of his collection of architectural essays First and Last Loves he says, “We accept the collapse of the fabrics of our old churches, the thieving of lead and objects from them, the commandeering and butchery of our scenery by the services, the despoiling of landscaped parks and the abandonment to a fate worse than the workhouse of our country houses, because we are convinced we must save money.” In a BBC film made in 1968 but not broadcast at that time, Betjeman described the sound of Leeds to be of “Victorian buildings crashing to the ground”. He went on to lambast John Poulson’s British Railways House (now City House), saying how it blocked all the light out to City Square and was only a testament to money with no architectural merit. He also praised the architecture of Leeds Town Hall. In 1969 Betjeman contributed the foreword to Derek Linstrum’s Historic Architecture of Leeds. Betjeman was for over 20 years a trustee of the Bath Preservation Trust and was Vice-President from 1965 to 1971, at a time when Bath—a city rich in Georgian architecture—was coming under increasing pressure from modern developers, and a major road was proposed to cut across it. He also created a short television documentary called Architecture of Bath, in which he voiced his concerns about the way the city’s architectural heritage was being mistreated. From 1946 to 1948 he had served as Secretary to the Oxford Preservation Trust. Legacy A memorial window, designed by John Piper, in All Saints’ Church, Farnborough, Hampshire, where Betjeman lived in the nearby Rectory. The Betjeman Millennium Park at Wantage in Oxfordshire, where he lived from 1951 to 1972 and where he set his book Archie and the Strict Baptists One of the roads in Pinner, a town covered in Betjeman’s film Metro-Land is called Betjeman Close, while another in Chorleywood, also covered in Metro-Land, is called Betjeman Gardens. The John Betjeman Poetry Competition for Young People (2006–) is open to 10- to 13-year-olds living anywhere in the British Isles (including the Republic of Ireland), with a first prize of £1,000. In addition to prizes for individual finalists, state schools who enter pupils may win one of six one-day poetry workshops. One of the engines on the pier railway at Southend-on-Sea is named Sir John Betjeman (the other Sir William Heygate). A British Rail Class 86 AC electric locomotive, 86229, was named Sir John Betjeman by the man in person at St Pancras station on 24 June 1983, just before his death; it was renamed Lions Group International in 1998 and is now in storage. The nameplate is now carried by Class 90 locomotive 90007, in service on the London– Norwich route. In 2003, to mark their centenary, the residents of Lissenden Gardens in north London put up a blue plaque to mark Betjeman’s birthplace. In 2006, a blue plaque was installed on Betjeman’s childhood home, 31 West Hill, Highgate, London N6. In 2006 a blue plaque was erected at Garrard’s Farm, Uffington, Oxfordshire which had been his first married home. The statue of Betjeman at St Pancras station in London by sculptor Martin Jennings was unveiled in 2007. In 2012 Betjeman featured on BBC Radio 4 as author of the week on The Write Stuff. On 1 September 2014 Betjeman was the subject of the hour-long BBC Four documentary Return to Betjemanland, presented by his biographer A. N. Wilson. At the start of the broadcast, there was a spoken tribute to Betjeman’s daughter Candida Lycett Green, who had died just twelve days earlier on 19 August, aged 71. On 28 August 2016 a bust of Betjeman based on the St Pancras statue was unveiled outside the Vale and Downland Museum in Wantage, Oxfordshire. Awards and honours * 1960 Queen’s Medal for Poetry * 1960 Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) * 1968 Companion of Literature, the Royal Society of Literature * 1969 Knight Bachelor * 1972 Poet Laureate * 1973 Honorary Member, the American Academy of Arts and Letters. * 2011 Honoured by the University of Oxford, his alma mater, as one of its 100 most distinguished members from ten centuries. Works * Mount Zion (1932) * Continual Dew (1937) * Old Lights For New Chancels (1940) * New Bats in Old Belfries (1945) * A Few Late Chrysanthemums (1954) * Poems in the Porch (1954) * Summoned by Bells (1960) * High and Low (1966) * A Nip in the Air (1974) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Betjeman

Soy lesbiana y puta desde que tengo uso de razón, me gano el café de cada día en los tétricos hostales de la perdición, me han sacudido en los catres de las casas de cita de los barrios olvidados y me dejo ensartar en cualquier poste o cañada, amo la estirpe de los poetas malditos y vivo muy apenada con Dios por ser atea. Referencias www.docstoc.com/docs/130127220/Salomón-Borrasca-POEMAS-LÉSBICOS Salomón Borrasca, nacida en Haiti, fue aclamada por policías, políticos y carniceros, aprendió a sumar contando granos de maíz, perdió la virginidad a los quince años en el zaguán de una casa de inquilinato, ejerció la prostitución decentemente durante muchos años, posterirmente se declaró lesbiana, desde entonces Haití no se sobrepone, no tiene estabilidad política. A sus noventa años administra un bar de mujeres tristes, también tiene una venta de camándulas en la entrada de un cementerio de Palmira, Colombia. Referencias http://poetascolombianos.blog.com.es/2012/05/14/poemas-eroticos-de-salomon-borrasca-13678534/

Joachim du Bellay (prononciation: /ʒɔaʃɛ̃ dy bɛlɛ/) ou Joachim Du Bellay est un poète français né vers 1522 à Liré en Anjou et mort le 1er janvier 1560 à Paris. Sa rencontre avec Pierre de Ronsard fut à l’origine de la formation de la Pléiade, groupe de poètes pour lequel du Bellay rédigea un manifeste, la Défense et illustration de la langue française. Son œuvre la plus célèbre, Les Regrets, est un recueil de sonnets d’inspiration élégiaque et satirique, écrit à l’occasion de son voyage à Rome de 1553 à 1557. Biographie En 1522 Joachim du Bellay naît à Liré, en Anjou, dans l’actuel département de Maine-et-Loire. Fils de Jean du Bellay, seigneur de Gonnord, et de Renée Chabot originaire de Liré, il appartient à la branche aînée des du Bellay. Ses parents meurent en 1532 quand il a 10 ans. De santé fragile, il est élevé par son frère aîné qui le néglige. Vers 1546, il part faire ses études de droit à l’université de Poitiers où il rencontre Salmon Macrin. En 1547 il fait la connaissance de Jacques Peletier du Mans et de Pierre de Ronsard. Il rejoint ce-dernier au collège de Coqueret à Paris. Dans cet établissement, sous l’influence du professeur de grec Jean Dorat, les deux hommes décident de former un groupe de poètes appelé d’abord la Brigade. Leur objectif est de créer des chefs-d’œuvre en français d’aussi bonne facture que ceux des Latins et des Grecs. Ce but s’accorde à la perfection avec celui de François 1er qui souhaite donner des lettres de noblesse au français. Jacques Peletier du Mans approuve leur projet et les accompagne dans leur entreprise. Du Bellay signe en 1549 un manifeste collectif, la Défense et illustration de la langue française. La Brigade se transforme en Pléiade avec l’arrivée de quatre nouveaux membres: Rémi Belleau, Étienne Jodelle, Pontus de Tyard et Jean-Antoine de Baïf. Joachim du Bellay publie dès l’année suivante, en 1550, son premier recueil de sonnets, L’Olive, imitant le style de l’italien Pétrarque. En 1553 du Bellay quitte la France pour accompagner le cardinal Jean du Bellay, cousin germain de son père, à la cour pontificale de Rome. Il doit pourvoir aux dépenses de la maison du cardinal malgré son peu de moyens financiers. Il attend avec impatience de découvrir Rome et la culture antique mais il est déçu. Chargé de l’intendance de son parent, du Bellay s’ennuie. Loin de jouir d’une liberté qu’il désirait, les intrigues de la cour du pape l’accaparent. Il est en effet mêlé directement aux événements diplomatiques entre la France et l’Italie. Il compose alors Les Regrets, œuvre dans laquelle il critique la vie romaine et exprime son envie de rejoindre son Anjou natal. Suivent Les Antiquités de Rome. En août 1557 Joachim tombe malade et souffre de plus en plus de la surdité, le cardinal Jean du Bellay le renvoie en France. Le poète loge au cloître Notre-Dame chez son ami Claude de Bize (auquel il s’adresse dans les sonnets 64, 136 et 142 de Les Regrets). De retour en France, il doit de plus se débattre dans des difficultés matérielles. En janvier 1558 il fait publier par Fédéric Morel l’Ancien son recueil Les Regrets ainsi que Les Antiquités de Rome. Du Bellay meurt des suites d’une apoplexie dans la nuit du 1er janvier 1560 au 1 rue Massillon à Paris, à l’âge de 37 ans. Il est inhumé à Paris en la chapelle de Saint-Crépin, une chapelle de Notre-Dame de Paris. Plaque commémorative posée à l’endroit où se trouvait la maison dans laquelle est mort le poète (angle des rues Massillon et Chanoinesse, Paris, IVe) Œuvres principales Défense et illustration de la langue française Défense et illustration de la langue française (La Deffence, et Illustration de la Langue Francoyse dans l’orthographe originale) est un manifeste littéraire, écrit en 1549 par le poète français Joachim du Bellay, qui expose les idées des poètes de la Pléiade. Le texte, plaidoyer en faveur de la langue française, paraît DIX ans après l’ordonnance de Villers-Cotterêts qui imposa le français comme langue du droit et de l’administration dans le royaume de France. Du Bellay montre sa reconnaissance envers François Ier, «notre feu bon Roi et père», pour son rôle dans le fleurissement des arts et de la culture. Le roi a en effet créé le Collège des lecteurs royaux. Il a en outre pérennisé une bibliothèque du roi alimentée par le dépôt légal et des achats. Du Bellay souhaite transformer la langue française, «barbare et vulgaire», en une langue élégante et digne. Il considère que la langue française est encore dans l’enfance et qu’il faut la fortifier en la pratiquant et en l’enrichissant par l’invention de nouveaux mots afin de la rendre aussi puissante que le sont le grec et le latin. Avec ses camarades de la Pléiade il envisage donc de l’enrichir afin d’en faire une langue de référence et d’enseignement. L’Olive L’Olive est un recueil de poèmes publié par Joachim du Bellay entre 1549 et 1550. Dans cet ouvrage il célèbre une maîtresse imaginaire en s’inspirant de Pétrarque. Le livre comporte d’abord 50 sonnets écrits en 1549. Mais il en comptera 115 lors de sa publication en 1550 chez Corrozet et L’Angelier. Les Regrets Les Regrets est un recueil de poèmes écrit pendant le voyage de Du Bellay à Rome de 1553 à 1557 et publié à son retour en 1558 par l’imprimeur Fédéric Morel, l’Ancien sis rue Jean-de-Beauvais à Paris. Cet ouvrage comprend 191 sonnets, tous en alexandrins. Le choix de ce mètre, plutôt que du décasyllabe, constitue une nouveauté. Contrairement au modèle pétrarquiste, le thème principal n’est pas l’amour d’une femme mais celui du pays natal et de la mélancolie due à l’éloignement. Le lecteur distingue trois tonalités principales, l’élégie (sonnets 6 à 49), la satire (sonnets 50 à 156) et l’éloge (sonnets 156 à 191). Le mythe d’Ulysse en quête du retour dans sa patrie inspire aussi le poète. Revenu en France, du Bellay y retrouve les travers observés à Rome. Ce recueil contient le sonnet le plus célèbre de son œuvre: Note: l’orthographe et la graphie employées à gauche sont celles de l’auteur au XVIe siècle, celles de droite sont les actuelles. Les Antiquités de Rome Les Antiquités de Rome est un recueil de 32 sonnets édité en 1558, alternant sonnets en décasyllabes et en alexandrins. Ce recueil est une méditation sur la grandeur de Rome et sur sa chute. Il se nourrit du mythe de la Gigantomachie. Du Bellay annonce déjà avec ce recueil le lyrisme romantique. En sa qualité d’humaniste, il reste l’héritier de Virgile, Horace, Lucain, tous poètes de la Ville éternelle. Notons aussi, en plus du thème des ruines, un tableau pittoresque qui saisit l’évolution de Rome dans ses détails. Postérité et culture populaire En 1578, une partie de ses odes est mise en musique par le compositeur Antoine de Bertrand. En 1894 la ville d’Ancenis fait ériger une statue réalisée par le sculpteur Adolphe Léonfanti. Elle représente le poète en costume du XVIe siècle, tenant à la main un exemplaire de son recueil Les Regrets. Dans les années 1960 elle est installée sur la rive gauche de la Loire, face à Liré. En 1934 son nom est donné au Collège des jeunes filles d’Angers qui devient le Collège Joachim du Bellay puis l’actuel Lycée Joachim-du-Bellay. La ville de Liré inaugure en 1947 une statue représentant le poète assis, méditant, œuvre du sculpteur Alfred Benon. Les Archives Nationales commémorent en 1949 le quatre centième anniversaire de son ouvrage Défense et illustration de la langue française. En 1958 un timbre postal de 12 f. surtaxé 4 f., vert est émis dans la série «Célébrités». Il porte le n° YT 1166. En 1960, à l’occasion du quatre centième anniversaire de sa mort, une commémoration avec conférence et récitations de ses textes a lieu devant les ruines du château de la Turmelière. Une école de la ville du Lude, dans la Sarthe, porte également son nom. En 2007 le chanteur Ridan reprend un extrait des Regrets de Joachim du Bellay. L’artiste le travaille à sa façon dans sa chanson Ulysse. En 2009, la compositrice Michèle Reverdy a mis en musique le sonnet XII des Regrets qui constitue la première pièce du cycle De l’ironie contre l’absurdité du monde. Musée Joachim du Bellay En 1957 l’Association «Les amis du Petit Lyré» acquiert à Liré une demeure de 1521 ayant appartenu à la famille du Bellay et y fonde un musée inauguré le 8 juin 1958. Le musée devient propriété communale vers 1990. Depuis 1998 il présente cinq salles dédiées à la vie et à l’œuvre de l’écrivain de la Pléiade ainsi qu’à la poésie et à la Renaissance. Le musée organise également des manifestations sur les thèmes de l’écriture, de la poésie et de la langue française. Œuvres * Il a créé de nombreuses œuvres et voici les plus connues: * Défense et illustration de la langue française (1549) * L’Olive (1549) * Vers lyriques (1549) * Recueil de poesie, presente à tres illustre princesse Madame Marguerite, seur unique du Roy […] (1549) (lire en ligne) * Le Quatriesme livre de l’Eneide, traduict en vers françoys (1552) (lire en ligne) * La Complainte de Didon à Enée, prince d’Ovide (1552) * Œuvres de l’invention de l’Auteur (1552) * Divers Jeux Rustiques (1558) * Les Regrets (1558) (lire en ligne) * Les Antiquités de Rome (1558) * Poésies latines, (1558) * Le Poète courtisan (1559) Les références Wikipedia – https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joachim_du_Bellay

Enrique Banchs (Buenos Aires, 1888 - 1968) fue un poeta argentino. Cultivó formas clásicas y diáfanas, inspiradas en el Siglo de Oro español, con fuertes reminiscencias hispanogermánicas y modernistas. Fue miembro de la Academia Argentina de Letras y desarrolló una carrera periodística. Trabajó en la publicación La Prensa, en la revista Atlántida y dirigió por varios años hasta su jubilación la revista del ex Consejo Nacional de Educación El Monitor de la Educación Común.1 Banchs se inició en el mundo literario en el primer número de la revista Nosotros, con solo algunos versos publicados. Publicó libros de poesía a comienzos del siglo XX. Su último libro está compuesto de sonetos, una forma lírica poco frecuente en los años en que escribió y dejada casi completamente de lado por los poetas posteriores. Banchs no se apartó de la vida literaria, pero no volvió a publicar poesía a lo largo de más de 50 años. Durante sus últimos días, se mantuvo en aislamiento y guardó silencio hasta su muerte, en 1968. Poesía * 1907: Las barcas * 1908: El libro de los elogios * 1909: El cascabel del halcón * 1911: La urna Prosa * 1941: Discurso de recepeción en la Academia Argentina de Letras * 1943: Averiguaciones sobre la autoridad en el idioma Referencias Wikipedia - http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Enrique_Banchs

William Lisle Bowles (24 September 1762– 7 April 1850) was an English priest, poet and critic. Life and career Bowles was born at King’s Sutton, Northamptonshire, where his father was vicar. At the age of 14 he entered Winchester College, where the headmaster at the time was Dr Joseph Warton. In 1781 Bowles left as captain of the school, and went on to Trinity College, Oxford, where he had won a scholarship. Two years later he won the Chancellor’s prize for Latin verse. Bowles came from a line of Church of England clergymen. His great-grandfather Matthew Bowles (1652–1742), grandfather Dr Thomas Bowles (1696–1773) and father William Thomas Bowles (1728–86) had all been parish priests. After taking his degree at Oxford, Bowles followed his forebears into the Church of England, and in 1792, after serving as curate in Donhead St Andrew, was appointed vicar of Chicklade in Wiltshire. In 1797 he received the vicarage of Dumbleton in Gloucestershire, and in 1804 became vicar of Bremhill in Wiltshire, where he wrote the poem seen on Maud Heath’s statue. In the same year his bishop, John Douglas, collated him to a prebendal stall in Salisbury Cathedral. In 1818 he was made chaplain to the Prince Regent, and in 1828 he was elected residentiary canon of Salisbury. Works * In 1789 he published, in a very small quarto volume, Fourteen Sonnets, which were received with extraordinary favour, not only by the general public, but by such men as Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Wordsworth. * The Sonnets even in form were a revival, a return to an older and purer poetic style, and by their grace of expression, melodious versification, tender tone of feeling and vivid appreciation of the life and beauty of nature, stood out in strong contrast to the elaborated commonplaces which at that time formed the bulk of English poetry. Bowles said thereof Poetic trifles from solitary rambles whilst chewing the cud of sweet and bitter fancy, written from memory, confined to fourteen lines, this seemed best adapted to the unity of sentiment, the verse flowed in unpremeditated harmony as my ear directed but are far from being mere elegiac couplets. * The longer poems published by Bowles are not of a very high standard, though all are distinguished by purity of imagination, cultured and graceful diction, and great tenderness of feeling. The most extensive were The Spirit of Discovery (1804), which was mercilessly ridiculed by Lord Byron; The Missionary (1813); The Grave of the Last Saxon (1822); and St John in Patmos (1833). Bowles is perhaps more celebrated as a critic than as a poet.In 1806 he published an edition of Alexander Pope’s works with notes and an essay, in which he laid down certain canons as to poetic imagery which, subject to some modification, were later accepted, but which were received at the time with strong opposition by admirers of Pope and his style. The controversy brought into sharp contrast the opposing views of poetry, which may be roughly described as the natural and the artificial. * Bowles was an amiable, absent-minded, and rather eccentric man. His poems are characterised by refinement of feeling, tenderness, and pensive thought, but are deficient in power and passion. Bowles maintained that images drawn from nature are poetically finer than those drawn from art; and that in the highest kinds of poetry the themes or passions handled should be of the general or elemental kind, and not the transient manners of any society. These positions were attacked by Byron, Thomas Campbell, William Roscoe and others, while for a time Bowles was almost solitary. William Hazlitt and the Blackwood critics came to his assistance, and on the whole Bowles had reason to congratulate himself on having established certain principles which might serve as the basis of a true method of poetical criticism, and of having inaugurated, both by precept and by example, a new era in English poetry. Among other prose works from his prolific pen was a Life of Bishop Ken (two volumes, 1830–1831). Other works include Coombe Ellen and St. Michael’s Mount (1798), The Battle of the Nile (1799), and The Sorrows of Switzerland (1801). * Bowles also enjoyed considerable reputation as an antiquary, his principal work in that department being Hermes Britannicus (1828). His Poetical Works were collected in 1855 as part of the Library Edition of the British Poets, with a memoir by George Gilfillan. Reception * Bowles’ work was important to the young Samuel Taylor Coleridge: * Bowles was the cause in the 1820s of the Alexander Pope controversy into which George Gordon, Lord Byron was drawn. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Lisle_Bowles

Grew up on a little gem in the Caribbean, a tourist attraction the eyes never misses. There I had my education, primary through college. Life has always been a challenge but with God I keep climbing, and my dreams are slowing becoming. Writer, teacher, website owner of https://www.livingtoreachacme.com/ and more. Always loved poetry. I dreamed of poetry, tried but never thought I was good enough. Today, I am here, I stand only by the Grace of God. He is just so awesome!!!!

Francisco Brines Bañó (Oliva, Valencia, 1932) es un poeta español. Pertenece al grupo poético de los años 50 o Generación del 50, junto a Claudio Rodríguez, Jaime Gil de Biedma y Ángel González Biografía Estudió derecho en la Universidad de Deusto, Valencia y Salamanca, y cursó estudios de Filosofía y Letras en Madrid. Está considerado uno de los poetas actuales de más hondo acento elegíaco. Pertenece a la segunda generación de la posguerra, y junto a Claudio Rodríguez y José Ángel Valente, entre otros, perteneció al grupo conocido como Generación del 50, si bien, a diferencia de la mayoría de los poetas del 50 o del medio siglo, nunca cultivó la poesía social (de la que hay rastros, sin embargo, en su libro El santo inocente, luego llamado Materia narrativa inexacta). Fue profesor de español en la Universidad de Oxford, y en 1988 revisó y adaptó el texto de [El alcalde de Zalamea], versión que fue estrenada en noviembre del mismo año por la Compañía de Teatro Clásico, y dirigida por José Luis Alonso. En el año 2001 fue nombrado miembro de la Real Academia Española, para ocupar el sillón X, vacante tras el fallecimiento del dramaturgo Antonio Buero Vallejo. Tomó posesión el 21 de mayo de 2006. Su obra poética, en la que se percibe una evidente influencia de Luis Cernuda, se caracteriza por un tono intimista y por la constante reflexión sobre el paso del tiempo. En su escritura, la infancia aparece como un tiempo mítico, que desconoce la muerte, ligado al espacio de Elca, la casa de la niñez en Oliva. El adulto ha sido expulsado definitivamente del paraíso de la infancia y sólo en algunos momentos (a través del erotismo, de la contemplación de la naturaleza...) el ser humano recupera la plenitud vital experimentada en la niñez y en la juventud. Por todo ello, la memoria desempeña un papel fundamental en su escritura, si bien en sus poemas se deja traslucir la convicción de que ni la poesía ni el recuerdo permiten detener el paso del tiempo y salvar los momentos de plenitud del pasado. En El otoño de las rosas, su libro más valorado por la crítica, se funden el lamento elegiaco y la exaltación vital. El tema del amor homosexual aparece recurrentemente en sus poemas, siempre con naturalidad. Según Ariadna G. García: Se reitera en la obra de Brines esta búsqueda incesante de la Pureza, en un intento por ennoblecer, moralmente, la homosexualidad. Su escritura, que tiende a un equilibrio clásico y a un tono melancólico, que intenta dominar la angustia ante la muerte mediante una asunción serena de lo inevitable, se nutre no sólo de la influencia de su admirado Luis Cernuda sino también, y en especial, en su primer libro, Las brasas, de la poesía de Juan Ramón Jiménez y del Antonio Machado más intimista. En su libro Aún no, se acerca a la poesía satírica, una línea que el poeta apenas ha cultivado posteriormente. Son muchos los poetas de las últimas generaciones que se interesan en la poesía de Brines, desde "novísimos" como Jaime Siles o Luis Antonio de Villena hasta poetas de ahora mismo. Obra poética * Las brasas (1960). Premio Adonais * El santo inocente (1965) * Palabras a la oscuridad (1966). Premio de la Crítica * Aún no (1971) * Insistencias en Luzbel (1977) * El otoño de las rosas (1986). Premio Nacional de Literatura * La última costa (1995). Premio Fastenrath de la Real Academia Española Antologías * Ensayo de una despedida. Poesía 1960-1971 (1974) * Poesía. 1960-1981 (1984) * Selección propia, Madrid, Cátedra, 1984 * Poemas excluidos (1985) * La rosa de las noches (1986) * Poemas a D. K. (1986) * El rumor del tiempo, Barcelona, Anagrama, 1989 * Espejo ciego, Generalitat Valenciana, 1993 * Breve antología personal (1997) * Francisco Brines, poesía, Universitat de Lleida, 1997 * Selección de poemas (1997) * Poesía completa (1960-1997) (1997) * Antología poética (1998) * La Iluminada Rosa Negra (2003) * Amada vida mía (2004) * Antología poética, Madrid, Espasa-Calpe, 2006 * Todos los rostros del pasado, Barcelona, Círculo, 2007 * Para quemar la noche, Madrid, Patrimonio Nacional, 2010 * Yo descanso en la luz, Madrid, Visor, 2010 Otras obras * Escritos sobre poesía española contemporánea, Valencia, Pre-Textos, 1994. * "Carmen Calvo", Caja de Ahorros de Asturias, 1999 * 2002 Luis Cernuda, Ocnos. Edición literaria de Francisco Brines. Unidad y cercanía personal en la poesía de Luis Cernuda: discurso de ingreso en la Real Academia Española, contestado por Francisco Nieva, Sevilla, Renacimiento, 2006. * 2010 ELCA. Libro de artista conjunto con Mariona Brines. Valencia, Editorial Krausse. Algunos galardones recibidos * 2010 Premio Reina Sofía de Poesía Iberoamericana. * 2007 IV Premio de Poesía Federico García Lorca * 2004 Premio a la Creatividad 'Ricardo Marín' * 1999 Premio Nacional de las Letras Españolas. * 1998 Premio Fastenrath. * 1987 Premio Nacional de Literatura. * 1967 Premio de las Letras Valencianas. * 1967 Premio Nacional de la Crítica * 1960 Premio Adonais Bibliografía sobre su obra * José Andújar Almansa, La palabra y la rosa. Sobre la poesía de Francisco Brines. Alianza, 2003. * Carlos Bousoño, Poesía poscontemporánea. Cuatro estudios y una introducción. Júcar, 1985. * Antonio García Berrio, Empatía. La poesía sentimental de Francisco Brines. Generalitat Valenciana, 2003. * José Luis Gómez Toré, La mirada elegíaca. El espacio y la memoria en la poesía de Francisco Brines. Pre-Textos, 2002. * José Olivio Jiménez, La poesía de Francisco Brines. Renacimiento, 2001. * David Pujante, Belleza mojada. La escritura poética de Francisco Brines. Renacimiento, 2004. Referencias Wikipedia – http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francisco_Brines

(SÉ QUE NO SON POEMAS) “Hay un lugar donde mueren porfin nuestras soledades donde nosotros pertenecemos con todas las libertades, en las esquinas en donde paran las penas de las ciudades, será nuestro loco paraiso de nostalgias y cuna de oscuridades. Soñamos la idea de un destino que guía todos nuestros pasos que cuida nuestras pobres almas de las glorias y los fracasos. Será cuando tenga que ser pero si es, que sea para siempre ayer mañana y pasado y todos los dias de diciembre.” (cita)

Carlos Barral y Agesta, (Barcelona, 1928 - Barcelona, 12 de diciembre de 1989), poeta, memorialista, editor y senador1 español nacido en Barcelona. Licenciado en Derecho por la Universidad de Barcelona en 1950, fue Alma mater, junto a Jaime Gil de Biedma, de la generación literaria de los 50. Es el poeta más complejo de la generación (José Agustín Goytisolo, Gabriel Ferrater, etc.) y el que consigue unos juegos del lenguaje más elevados. Escribió tres volúmenes de memorias que son un hito del género en español. Casado con Yvonne Hortet, mujer perteneciente a la alta burguesía barcelonesa, tuvo cinco hijos (la traductora, ilustradora y empresaria Dánae Barral, el escultor Dario Barral, Marco, Alexis e Yvonne), su vida estuvo fuertemente ligada al mar y a la localidad costera tarragonesa de Calafell, donde residía largas temporadas. Al asumir la jefatura de la editorial Seix Barral, empresa familiar de libros de texto fundada por sus padres en 1911, le imprimió una dirección que le llevó a ser la referencia literaria de todo el mundo hispano editando clásicos de la cultura progresista de los cincuenta, sesenta y setenta. Creó un premio de edición a escala internacional, el Formentor, el Biblioteca Breve y el premio Barral de novela, y fue uno de los artífices del boom latinoamericano y dio a conocer a autores como Juan Marsé, Mario Vargas Llosa, Alfredo Bryce Echenique o Julio Cortázar. Aficionado a la vela, y de salud delicada, fue además senador por Tarragona en 1982 y parlamentario europeo por el PSC-PSOE. En 1988 obtuvo el Premio Comillas de Tusquets Editores en la categoría de Memorias por Cuando las horas veloces. Murió en Barcelona en 1989. Escribió treinta años de Diarios y mantuvo correspondencia, entre otros, con Max Aub, María Zambrano, Camilo José Cela, Miguel Delibes, Gonzalo Torrente Ballester, Vicente Aleixandre, Caballero Bonald, Alfredo Bryce Echenique, Giulio Einaudi, Alberto Oliart, Jaime Gil de Biedma, Jaime Salinas Bonmatí y los presos políticos de Burgos. Su archivo se encuentra depositado en la Biblioteca de Cataluña. Obra * Tuvo varios poemas relevantes en la década de los 60, como vemos posteriormente. Lírica * Las aguas reiteradas (1952) * Metropolitano (1957) * Diecinueve figuras de mi historia civil (1961) * Usuras (1965) * Figuración y fuga (1966) * Informe personal sobre el alba (1970) * Usuras y figuraciones (1973) * Lecciones de cosas: Veinte poemas para el nieto Malcolm (1986) * Antología poética (1989) * Poesía completa (1998) Artículos periodísticos * Observaciones a la mina de plomo, Barcelona: Lumen, 2002. Libros de fotografías * Catalunya des del mar (1982) * Catalunya a vol d'ocell (1985)ç Memorias * Años de penitencia (1975) * Los años sin excusa (1978) * Cuando las horas veloces (1988) * Memorias; prólogos de José María Castellet y Alberto Oliart, Barcelona: Península, 2001 (edición completa de los libros anteriores) * Los diarios / 1957-1989 (1993) * Almanaque (1999, entrevistas completas). * Memorias de infancia, incompletas e inéditas. Novela * Penúltimos castigos (1983, novela autobiográfica). * El azul del infierno (novela incompleta e inédita sobre el cuadro El paso de la laguna Estigia de Patinir). Traducciones Rainer María Rilke, Sonetos a Orfeo. Filmografía En 2010 el director Sigfrid Monleón dirige la película El cónsul de Sodoma, en donde el escritor (interpretado por Josep Linuesa) conoce al poeta Jaime Gil de Biedma. referencias Wikipedia-http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carlos_Barral

Charlotte Brontë (21 April 1816 – 31 March 1855) was an English novelist and poet, the eldest of the three Brontë sisters who survived into adulthood, whose novels are English literature standards. She wrote Jane Eyre under the pen name Currer Bell. Early life and education Charlotte was born in Thornton, Yorkshire in 1816, the third of six children, to Maria (née Branwell) and her husband Patrick Brontë (formerly surnamed Brunty or Prunty), an Irish Anglican clergyman. In 1820, the family moved a few miles to the village of Haworth, where Patrick had been appointed Perpetual Curate of St Michael and All Angels Church. Charlotte's mother died of cancer on 15 September 1821, leaving five daughters and a son to be taken care of by her sister Elizabeth Branwell. In August 1824, Charlotte was sent with three of her sisters, Emily, Maria, and Elizabeth, to the Clergy Daughters' School at Cowan Bridge in Lancashire (She used the school as the basis for Lowood School in Jane Eyre). The school's poor conditions, Charlotte maintained, permanently affected her health and physical development and hastened the deaths of her two elder sisters, Maria (born 1814) and Elizabeth (born 1815), who died of tuberculosis in June 1825. Soon after their deaths, her father removed Charlotte and Emily from the school. At home in Haworth Parsonage Charlotte acted as "the motherly friend and guardian of her younger sisters". She and her surviving siblings — Branwell, Emily, and Anne – created their own literary fictional worlds, and began chronicling the lives and struggles of the inhabitants of these imaginary kingdoms. Charlotte and Branwell wrote Byronic stories about their imagined country, "Angria", and Emily and Anne wrote articles and poems about "Gondal". The sagas they created were elaborate and convoluted (and still exist in partial manuscripts) and provided them with an obsessive interest during childhood and early adolescence, which prepared them for their literary vocations in adulthood. Charlotte continued her education at Roe Head in Mirfield, from 1831 to 1832, where she met her lifelong friends and correspondents, Ellen Nussey and Mary Taylor. Shortly after she wrote the novella The Green Dwarf (1833) using the name Wellesley. Charlotte returned to Roe Head as a teacher from 1835 to 1838. In 1839, she took up the first of many positions as governess to families in Yorkshire, a career she pursued until 1841. Politically a Tory, she preached tolerance rather than revolution. She held high moral principles, and, despite her shyness in company, was always prepared to argue her beliefs. Brussels In 1842 Charlotte and Emily travelled to Brussels to enrol in a boarding school run by Constantin Heger (1809–96) and his wife Claire Zoé Parent Heger (1804–87). In return for board and tuition, Charlotte taught English and Emily taught music. Their time at the boarding school was cut short when Elizabeth Branwell, their aunt who joined the family after the death of their mother to look after the children, died of internal obstruction in October 1842. Charlotte returned alone to Brussels in January 1843 to take up a teaching post at the school. Her second stay was not a happy one; she became lonely, homesick and deeply attached to Constantin Heger. She returned to Haworth in January 1844 and used her time at the boarding school as the inspiration for some experiences in The Professor and Villette. First publication In May 1846, Charlotte, Emily, and Anne self-financed the publication of a joint collection of poetry under the assumed names of Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell. These pseudonyms veiled the sisters' gender whilst preserving their real initials, thus Charlotte was "Currer Bell". "Bell" was the middle name of Haworth's curate, Arthur Bell Nicholls, whom Charlotte later married. On the decision to use noms de plume, Charlotte wrote: Averse to personal publicity, we veiled our own names under those of Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell; the ambiguous choice being dictated by a sort of conscientious scruple at assuming Christian names positively masculine, while we did not like to declare ourselves women, because — without at that time suspecting that our mode of writing and thinking was not what is called 'feminine' – we had a vague impression that authoresses are liable to be looked on with prejudice; we had noticed how critics sometimes use for their chastisement the weapon of personality, and for their reward, a flattery, which is not true praise. Although only two copies of the collection of poetry were sold, the sisters continued writing for publication and began their first novels, continuing to use their noms de plume when sending manuscripts to potential publishers. Jane Eyre Charlotte's first manuscript, The Professor, did not secure a publisher, although she was heartened by an encouraging response from Smith, Elder & Co of Cornhill, who expressed an interest in any longer works which "Currer Bell" might wish to send. Charlotte responded by finishing and sending a second manuscript in August 1847, and six weeks later Jane Eyre: An Autobiography, was published. Jane Eyre was a success, and initially received favourable reviews. There was speculation about the identity of Currer Bell, and whether Bell was a man or a woman. The speculation heightened on the subsequent publication of novels by Charlotte's sisters: Emily's Wuthering Heights by "Ellis Bell" and Anne's Agnes Grey by "Acton Bell". Accompanying the speculation was a change in the critical reaction to Charlotte's work; accusations began to be made that Charlotte's writing was "coarse", a judgement which was made more readily once it was suspected that "Currer Bell" was a woman. However sales of Jane Eyre continued to be strong, and may even have increased due to the novel's developing reputation as an 'improper' book. Shirley and family bereavements Following the success of Jane Eyre, in 1848 Charlotte began work on the manuscript of her second novel, Shirley. The manuscript was only partially completed when the Brontë household suffered a tragic turn of events, experiencing the deaths of three family members within eight months. In September 1848 Charlotte's only brother, Branwell, died of chronic bronchitis and marasmus exacerbated by heavy drinking, although Charlotte believed his death was due to tuberculosis. Branwell was a suspected "opium eater", a laudanum addict. Emily became seriously ill shortly after Branwell's funeral, and died of pulmonary tuberculosis in December 1848. Anne died of the same disease in May 1849. Charlotte was unable to write at this time. After Anne's death Charlotte resumed writing as a way of dealing with her grief, and Shirley was published in October 1849. Shirley deals with the themes of industrial unrest and the role of women in society. Unlike Jane Eyre, which is written from the first-person perspective of the main character, Shirley is written in the third-person and lacks the emotional immediacy of Jane Eyre, and reviewers found it less shocking. In society In view of the success of her novels, particularly Jane Eyre, Charlotte was persuaded by her publisher to visit London occasionally, where she revealed her true identity and began to move in a more exalted social circle, becoming friends with Harriet Martineau and Elizabeth Gaskell, and acquainted with William Makepeace Thackeray and G. H. Lewes. She never left Haworth for more than a few weeks at a time as she did not want to leave her ageing father's side. Thackeray’s daughter, the writer Anne Isabella Thackeray Ritchie recalled a visit to her father by Charlotte: …two gentlemen come in, leading a tiny, delicate, serious, little lady, with fair straight hair, and steady eyes. She may be a little over thirty; she is dressed in a little barège dress with a pattern of faint green moss. She enters in mittens, in silence, in seriousness; our hearts are beating with wild excitement. This then is the authoress, the unknown power whose books have set all London talking, reading, speculating; some people even say our father wrote the books – the wonderful books… The moment is so breathless that dinner comes as a relief to the solemnity of the occasion, and we all smile as my father stoops to offer his arm; for, genius though she may be, Miss Brontë can barely reach his elbow. My own personal impressions are that she is somewhat grave and stern, specially to forward little girls who wish to chatter… Every one waited for the brilliant conversation which never began at all. Miss Brontë retired to the sofa in the study, and murmured a low word now and then to our kind governess… the conversation grew dimmer and more dim, the ladies sat round still expectant, my father was too much perturbed by the gloom and the silence to be able to cope with it at all… after Miss Brontë had left, I was surprised to see my father opening the front door with his hat on. He put his fingers to his lips, walked out into the darkness, and shut the door quietly behind him… long afterwards… Mrs. Procter asked me if I knew what had happened… It was one of the dullest evenings [Mrs Procter] had ever spent in her life… the ladies who had all come expecting so much delightful conversation, and the gloom and the constraint, and how finally, overwhelmed by the situation, my father had quietly left the room, left the house, and gone off to his club. Friendship with Elizabeth Gaskell Charlotte sent copies of Shirley to leading authors of the day, including Elizabeth Gaskell. Gaskell and Charlotte met in August 1850 and began a friendship which, whilst not necessarily close, was significant in that Gaskell wrote Charlotte's biography after her death in 1855. The Life of Charlotte Brontë, was published in 1857 and was unusual at the time in that, rather than analysing its subject's achievements, it concentrated on the private details of Charlotte's life, in particular placing emphasis on aspects which countered the accusations of 'coarseness' which had been levelled at Charlotte's writing. Though frank in places, Gaskell was selective about which details she revealed; for example, she suppressed details of Charlotte's love for Heger, a married man, as being too much of an affront to contemporary morals and as a source of distress to Charlotte's still-living friends, father and husband. Gaskell also provided doubtful and inaccurate information about Patrick Brontë, claiming, for example, that he did not allow his children to eat meat. This is refuted by one of Emily Brontë's diary papers, in which she describes the preparation of meat and potatoes for dinner at the parsonage, as Juliet Barker points out in her biography, The Brontës. It has been argued that the particular approach of Mrs Gaskell transferred the focus of attention away from the 'difficult' novels, not just of Charlotte but all the sisters, and began a process of sanctification of their private lives. Villette Charlotte's third published novel, and the last to be published during her lifetime, was Villette, which came out in 1853. Its main themes include isolation, how such a condition can be borne, and the internal conflict brought about by societal repression of individual desire. Its main character, Lucy Snowe, travels abroad to teach in a boarding school in the fictional town of Villette, where she encounters a culture and religion different to her own, and where she falls in love with a man ('Paul Emanuel') whom she cannot marry. Her experiences result in her having a breakdown, but eventually she achieves independence and fulfilment in running her own school. Villette marked Charlotte's return to writing from a first-person perspective (that of Lucy Snowe), a technique she had used successfully in Jane Eyre. Another similarity to Jane Eyre was Charlotte's use of aspects from her own life as inspiration for fictional events, in particular reworking her time spent at the pensionnat in Brussels into Lucy spending time teaching at the boarding school, and falling in love with Constantin Heger into Lucy falling in love with 'Paul Emanuel'. Villette was acknowledged by the critics of the day as a potent and sophisticated piece of writing, although it was criticised for its 'coarseness' and not suitably 'feminine' in its portrayal of Lucy's desires. Illness and subsequent death In June 1854, Charlotte married Arthur Bell Nicholls, her father's curate and possibly the model for Jane Eyre's St. John Rivers. She became pregnant soon after the marriage. Her health declined rapidly during this time, and according to Gaskell, she was attacked by "sensations of perpetual nausea and ever-recurring faintness." Charlotte died, with her unborn child, on 31 March 1855, at the age of 38. Her death certificate gives the cause of death as phthisis (tuberculosis), but many biographers[who?] suggest she may have died from dehydration and malnourishment, caused by excessive vomiting from severe morning sickness or hyperemesis gravidarum. There is evidence to suggest that Charlotte died from typhus she may have caught from Tabitha Ackroyd, the Brontë household's oldest servant, who died shortly before her. Charlotte was interred in the family vault in the Church of St Michael and All Angels at Haworth. Posthumously, her first-written novel was published in 1857. The fragment she worked on in her last years in 1860 has been twice completed by recent authors, the more famous version being Emma Brown: A Novel from the Unfinished Manuscript by Charlotte Brontë by Clare Boylan in 2003. Much Angria material has appeared in published form since the author's death.

i live in my mind,dance to my heart beat,a fairytale castle rooted within my soul. Ive always loved art,started painting at the age of 11 and started writing by the age of 14. i write about the journey of my life,my experiences and the influences of the environment around me.my poetry UN-folds spiritual experiences,it is a reflection of being loyal and true to your self as a person. i honor my worth and through my poetry i aim to heal,touch and groom the hearts that i can reach. my poetry simply says you're never alone in a situation.

Katharine Lee Bates (August 12, 1859– March 28, 1929) was an American songwriter. She is remembered as the author of the words to the anthem “America the Beautiful”. She popularized “Mrs. Santa Claus” through her poem Goody Santa Claus on a Sleigh Ride (1889). Life and career Bates was born in Falmouth, Massachusetts, the daughter of Congregational pastor William Bates and his wife, Cornelia Frances Lee. She graduated from Wellesley High School in 1874 and from Wellesley College with a B.A. in 1880. She taught at Natick High School during 1880–81 and at Dana Hall School from 1885 until 1889. She returned to Wellesley as an instructor, then an associate professor 1891–93 when she was awarded an M.A. and became full professor of English literature. She studied at Oxford University during 1890–91. While teaching at Wellesley, she was elected a member of the newly formed Pi Gamma Mu honor society for the social sciences because of her interest in history and politics. Bates was a prolific author of many volumes of poetry, travel books, and children’s books. She popularized Mrs. Claus in her poem Goody Santa Claus on a Sleigh Ride from the collection Sunshine and other Verses for Children (1889). She contributed regularly to periodicals, sometimes under the pseudonym James Lincoln, including Atlantic Monthly, The Congregationalist, Boston Evening Transcript, Christian Century, Contemporary Verse, Lippincott’s and Delineator. A lifelong, active Republican, Bates broke with the party to endorse Democratic presidential candidate John W. Davis in 1924 because of Republican opposition to American participation in the League of Nations. She said: “Though born and bred in the Republican camp, I cannot bear their betrayal of Mr. Wilson and their rejection of the League of Nations, our one hope of peace on earth.” Bates never married. In 1910, when a colleague described “free-flying spinsters” as “fringe on the garment of life”, Bates answered: “I always thought the fringe had the best of it. I don’t think I mind not being woven in.” Bates died in Wellesley, Massachusetts, on September 28, 1929, and is buried in Oak Grove Cemetery at Falmouth. The historic home and birthplace of Bates in Falmouth, was sold to Ruth P. Clark in November 2013 for $1,200,000. Relationship with Katharine Coman Bates lived in Wellesley with Katharine Coman, who was a history and political economy teacher and founder of the Wellesley College School Economics department. The pair lived together for twenty-five years until Coman’s death in 1915. In 1922, Bates published Yellow Clover: A Book of Remembrance, a collection of poems written “to or about my Friend” Katharine Coman, some of which had been published in Coman’s lifetime. Some describe the couple as intimate lesbian partners, citing as an example Bates’ 1891 letter to Coman: "It was never very possible to leave Wellesley [for good], because so many love-anchors held me there, and it seemed least of all possible when I had just found the long-desired way to your dearest heart... Of course I want to come to you, very much as I want to come to Heaven." Others contest the use of the term lesbian to describe such a “Boston marriage”. Writes one: “We cannot say with certainty what sexual connotations these relationships conveyed. We do know that these relationships were deeply intellectual; they fostered verbal and physical expressions of love.” America the Beautiful The first draft of “America the Beautiful” was hastily jotted down in a notebook during the summer of 1893, which Bates spent teaching English at Colorado College in Colorado Springs, Colorado. Later she remembered: One day some of the other teachers and I decided to go on a trip to 14,000-foot Pikes Peak. We hired a prairie wagon. Near the top we had to leave the wagon and go the rest of the way on mules. I was very tired. But when I saw the view, I felt great joy. All the wonder of America seemed displayed there, with the sea-like expanse. The words to her only famous poem first appeared in print in The Congregationalist, a weekly journal, for Independence Day, 1895. The poem reached a wider audience when her revised version was printed in the Boston Evening Transcript on November 19, 1904. Her final expanded version was written in 1913. When a version appeared in her collection America the Beautiful, and Other Poems (1912), a reviewer in the New York Times wrote: “we intend no derogation to Miss Katharine Lee Bates when we say that she is a good minor poet.” The hymn has been sung to several tunes, but the familiar one is by Samuel A. Ward (1847–1903), written for his hymn “Materna” (1882). Honors The Bates family home on Falmouth’s Main Street is preserved by the Falmouth Historical Society. There is also a street named in her honor, “Katharine Lee Bates Road” in Falmouth. A plaque marks the site of the home where she lived as an adult on Centre Street in Newton, Massachusetts. The Katharine Lee Bates Elementary School on Elmwood Road in Wellesley, Massachusetts, and the Katharine Lee Bates Elementary School, founded in 1957 in Colorado Springs, Colorado, and Bates Hall dormitory at Wellesley College are named for her. The Katharine Lee Bates Professorship was established at Wellesley shortly after her death. Bates was inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1970. Collections of Bates’s manuscripts are housed at the Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, Radcliffe College; Falmouth Historical Society; Houghton Library, Harvard University; Wellesley College Archives. In 2012, she was listed as one of the 31 LGBT history “icons” by the organisers of LGBT History Month.

Hello, thank you for taking the time to stop by and to read my poems, what can i say about me? how can i tell you all about me and my life? i don't normally write about me but i can only try! I am 19 years old, and i live in Australia, I still live with my parents, i have 2 dogs, Neo and Pierre, they are my babies don't know what i would do without them! I love music, movies, taking pics, i love photography! I work as a Nanny but i am also a Nurse. My life hasn't been perfect, in fact most of my late childhood or should i say the start of my teen years was a living nightmare, Hence i started poetry, when no one else was there for me Poetry was. I have written poems in my darkest moments, and they got me through. You may be asking what has happened that is so bad, Well, I have PTSD (Post-traumatic stress disorder) I have suffered depression, anxiety, and so on, Now you will be asking what has happened? When i was 13 i was raped by one of my so called male "best friend" Nobody knew until 18 months later, during the time, i suffered depression really badly, i even tried taking my life, enough of this, The things i have gone though has taught me everything happens for a reason, everything i have been through, made me the person i am today, there is always a light at the end of every dark tunnel. Each of my poems has meanings behind them, each one of them i have experienced something enough to write about it. Every body in this world has a story to tell, this is mine Anyways enough about me, i hope you enjoy reading them. and remember to SMILE :) life is to short.

Théodore Faullain de Banville, né le 14 mars 1823 à Moulins (Allier) et mort le 13 mars 1891 à Paris 6e arrondissement, est un poète, dramaturge et critique dramatique français. Célèbre pour les Odes funambulesques et Les Exilés, il est surnommé « le poète du bonheur ». Ami de Victor Hugo, de Charles Baudelaire et de Théophile Gautier, il est considéré dès son vivant comme l’un des plus éminents poètes de son époque. Théodore de Banville unit dans son œuvre le romantisme et le parnasse, dont il fut l’un des précurseurs. Il professait un amour exclusif de la beauté et la limpidité universelle de l’acte poétique, s’opposant à la fois à la poésie réaliste et à la dégénérescence du romantisme, contre lesquels il affirmait sa foi en la pureté de la création artistique. Biographie Fils du lieutenant de vaisseau Claude Théodore Faullain de Banville et de Zélie Huet, Théodore de Banville a fait ses études au lycée Condorcet à partir de 1830. Encouragé par Victor Hugo et par Théophile Gautier, il se consacra à la poésie, et fréquenta les milieux littéraires parmi les plus anticonformistes. Il méprisait la poésie officielle et commerciale, fut l’adversaire résolu de la nouvelle poésie réaliste et l’ennemi de la dérive larmoyante du romantisme. Il collabore aussi comme critique dramatique et chroniqueur littéraire aux journaux le Pouvoir (1850), puis le National (1869) ; il devient une figure très importante du monde littéraire et participe à la Revue fantaisiste (1861), où se retrouvent les poètes qui furent à l’origine du Parnasse et de tous les mouvements de ce siècle. Il rencontre Marie-Élisabeth Rochegrosse en 1862 (ils se marieront treize ans plus tard, le 15 février 1875), et organise la première représentation de Gringoire en 1866. Il publie Les Exilés en 1867, recueil qu’il dédie à sa femme et qu’il considéra comme le meilleur de son œuvre. Âgé de 16 ans, Arthur Rimbaud, initié à la poésie de son temps par la revue collective Le Parnasse contemporain, lui envoie une lettre (datée du 24 mai 1870), en y joignant plusieurs poèmes (Ophélie, Sensation, Soleil et chair), dans l’espoir d'obtenir son appui auprès de l’éditeur Alphonse Lemerre. Banville répond à Rimbaud, mais les poèmes ne sont pas publiés. En novembre 1871, Théodore de Banville héberge Arthur Rimbaud, mais dès le mois de mai, ce dernier dans ses lettres dites « du voyant » exprime sa différence et, en août 1871, dans son poème parodique, Ce qu'on dit au poète à propos de fleurs, exprime une critique ouverte de la poétique de Banville. En 1872, avec son Petit Traité de poésie française, Banville rompt avec le courant symboliste. Il publie presque une œuvre par an tout au long des années 1880, et meurt à Paris le 13 mars 1891, la veille de ses 68 ans, peu après la publication de son seul roman, Marcelle Rabe. Théodore de Banville a particulièrement travaillé, dans son œuvre, les questions de forme poétique, et a joué avec toutes les richesses de la poésie française. Il lui a été reproché d'avoir manqué de sensibilité et d'imagination, mais son influence salutaire permit à de nombreux poètes de se dégager de la sensiblerie mièvre qui survivait au véritable romantisme. Il est inhumé au cimetière du Montparnasse (13e division). Les références Wikipedia – https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Théodore_de_Banville

Blurb Saleha Begum is a writer and artist living in Birmingham. She was short-listed for the Muslim Writers award in 2011. 'Ruptures and Fragments', her first collection, combines poems with visual art. Drawn from a wide variety of sources and experiences, the poems explore human relationships, sometimes joyous, sometimes brutal, and the psyche, diving deep into the human condition, sorting and arranging, compartmentalising the external and what we are. This collection might leave the reader in a quandary but it will no doubt intrigue and encourage debate. Review "Shouting from the margins of society this is an engaging experimental collection that captures the stoicism of 21st century feminism through a combination of poetry and artistic metaphor. Saleha Begum exposes the ruptures and fragments of relationships and cultural identity through a nomadic style of wordplay that journeys both paradox and the de ja vu of similar experience." Antony Owen, author of 'The dreaded boy' "Saleha's poetry seems to dance and tease the mind, painting poignant images as they go. Lovely." Giovanni "Spoz" Esposito, Birmingham Poet Laureate 2006/7

William Barnes (22 February 1801– 7 October 1886) was an English writer, poet, Church of England priest, and philologist. He wrote over 800 poems, some in Dorset dialect, and much other work, including a comprehensive English grammar quoting from more than 70 different languages. Barnes was born at Rushay in the parish of Bagber, Dorset, the son of a farmer. His formal education finished when he was 13 years old. Between 1818 and 1823 he worked in Dorchester, the county town, as a solicitor’s clerk, then moved to Mere in neighbouring Wiltshire and opened a school. During his time here he began writing poetry in the Dorset dialect, as well as studying several languages (Italian, Persian, German and French, in addition to Greek and Latin), playing musical instruments (violin, piano and flute) and practising wood-engraving. He married Julia Miles, the daughter of an exciseman from Dorchester, in 1827, then in 1835 moved back to the county town, where again he ran a school. The school was initially in Durngate Street, then was moved to South Street. A second move to another South Street site made the school a neighbour of an architect’s practice where Thomas Hardy was an apprentice. The architect, John Hicks, was interested in literature and the classics, and when disputes about grammar occurred in the practice, Hardy would visit Barnes next door for an authoritative opinion.

André Breton, né à Tinchebray dans l'Orne le 19 février 1896 et mort à Paris le 28 septembre 1966, est un poète et écrivain français, principal animateur et théoricien du surréalisme. Auteur des livres Nadja, L'Amour fou et des différents Manifestes du surréalisme, son rôle de chef de file du mouvement surréaliste, et son œuvre critique et théorique pour l'écriture et les arts plastiques, font d'André Breton une figure majeure de l'art et de la littérature française du xxe siècle. Les références Wikipedia – https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andr%C3%A9_Breton

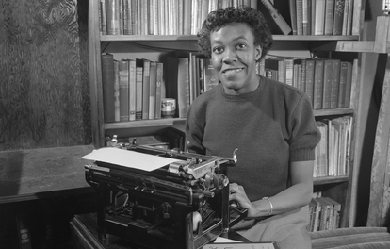

Gwendolyn Elizabeth Brooks (June 7, 1917– December 3, 2000) was an American poet and teacher. She was the first African-American woman to win a Pulitzer prize when she was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1950 for her second collection, Annie Allen. Throughout her career she received many more honors. She was appointed Poet Laureate of Illinois in 1968, a position held until her death and Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress in 1985.