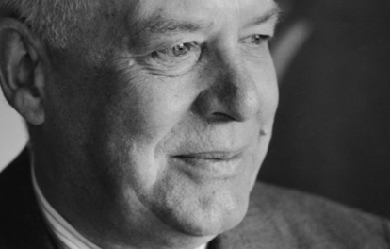

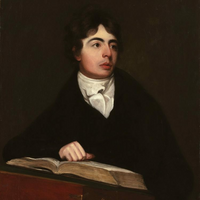

Robert William Service (January 16, 1874 – September 11, 1958) was a poet and writer who has often been called "the Bard of the Yukon". He was born in Preston, Lancashire, England and he is best known for his poems "The Shooting of Dan McGrew" and "The Cremation of Sam McGee", from his first book, Songs of a Sourdough (1907; also published as The Spell of the Yukon and Other Verses).

#English #XIXCentury #XXCentury

Wannabe poet/writer Writers are alchemists, turning mere words into gold, weaving tapestries of imagination. Whether etching sonnets or code, the love of writing is a compass, guiding us through the labyrinth of existence. It whispers, “You are here; you matter.” And so, we write—because within these sentences, we discover echoes of our own souls. My love of writing started in high school. My problem is I’m never satisfied and always too critical of myself to ever let anyone read my musings. And when I would win an award in high school, I would be so embarrassed that I would do anything I could to disguise my works or just avoid everyone, hahaha. Recently I went to a high school reunion and low and behold, someone had one of my short stories and a couple poems out on a table with other students works that had been written in 1973 and 1974. And when I re-read them I was amazed at myself. Then somehow my older sister came across some of my poems and said she wanted them and praised me again. I don’t know what has changed other than just getting older and not caring one iota any more about what people think or say. It’s therapy for me to jot down words that mean something at the time, and if someone reading them happens to identify then all the better… and yes, I have a severe inferiority complex.

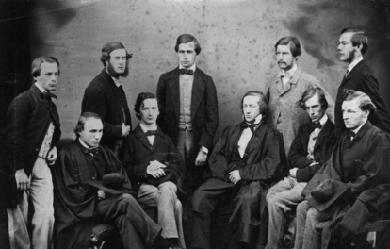

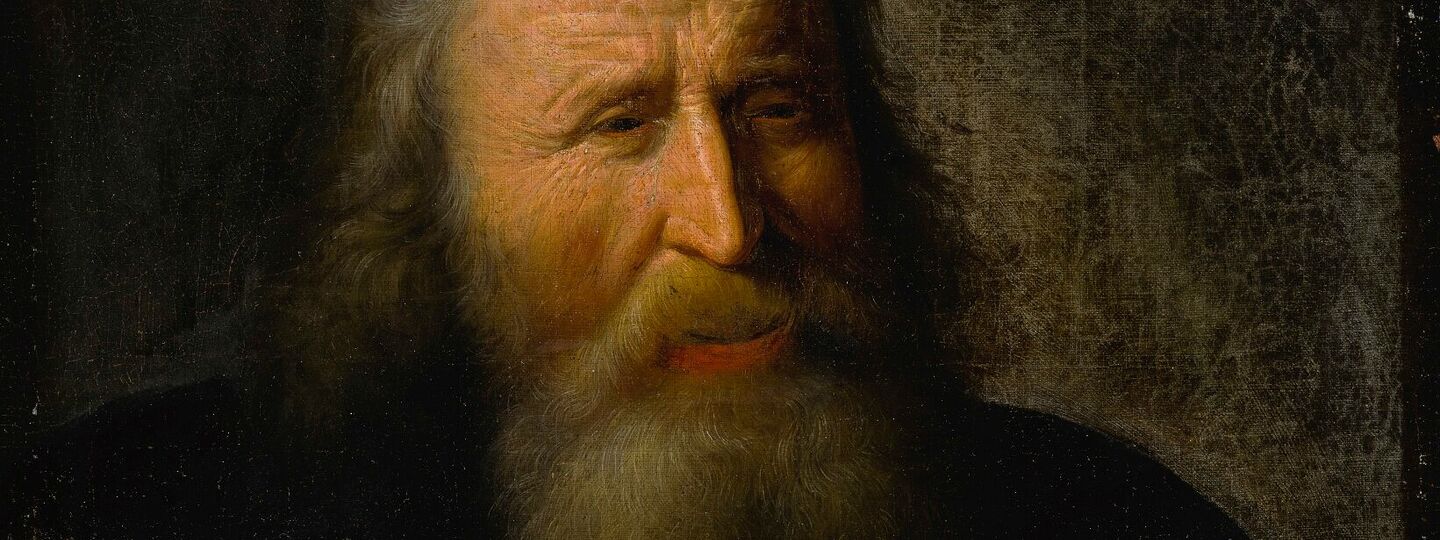

William Shakespeare (baptised 26 April 1564; died 23 April 1616) was an English poet and playwright, widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's national poet and the "Bard of Avon". His surviving works, including some collaborations, consist of about 38 plays, 154 sonnets, two long narrative poems, and several other poems. His plays have been translated into every major living language and are performed more often than those of any other playwright. Authorship Around 230 years after Shakespeare’s death, doubts began to be expressed about the authorship of the works attributed to him. Proposed alternative candidates include Francis Bacon, Christopher Marlowe, and Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford. Several “group theories” have also been proposed. All but a few Shakespeare scholars and literary historians consider it a fringe theory, with only a small minority of academics who believe that there is reason to question the traditional attribution, but interest in the subject, particularly the Oxfordian theory of Shakespeare authorship, continues into the 21st century.

#English #XVICentury #XVIICentury

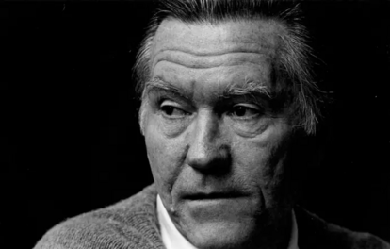

Carl Sandburg was born in Galesburg, Illinois, on January 6, 1878. His parents, August and Clara Johnson, had emigrated to America from the north of Sweden. After encountering several August Johnsons in his job for the railroad, the Sandburg's father renamed the family. The Sandburgs were very poor; Carl left school at the age of thirteen to work odd jobs, from laying bricks to dishwashing, to help support his family. At seventeen, he traveled west to Kansas as a hobo. He then served eight months in Puerto Rico during the Spanish-American war. While serving, Sandburg met a student at Lombard College, the small school located in Sandburg's hometown. The young man convinced Sandburg to enroll in Lombard after his return from the war.

#Americans #PulitzerPrice #XIXCentury #XXCentury

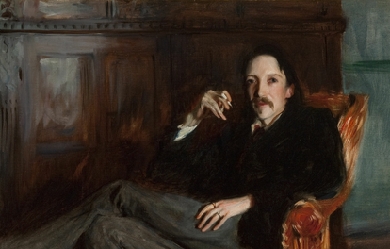

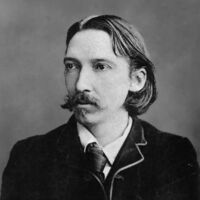

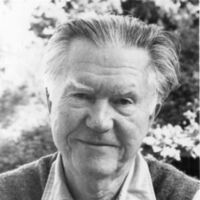

Robert Louis Balfour Stevenson (13 November 1850 – 3 December 1894) was a Scottish novelist, poet, essayist and travel writer. His best-known books include Treasure Island, Kidnapped, and Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. A literary celebrity during his lifetime, Stevenson now ranks among the 26 most translated authors in the world. He has been greatly admired by many authors, including Jorge Luis Borges, Ernest Hemingway, Rudyard Kipling, Marcel Schwob, Vladimir Nabokov, J. M. Barrie, and G. K. Chesterton, who said of him that he “seemed to pick the right word up on the point of his pen, like a man playing spillikins”.

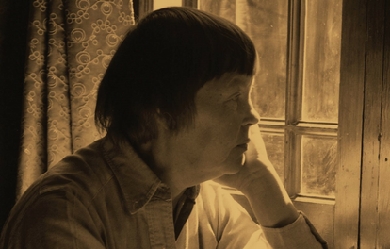

Percy Bysshe Shelley (4 August 1792 – 8 July 1822) was one of the major English Romantic poets and is critically regarded as among the finest lyric poets in the English language. Shelley was famous for his association with John Keats and Lord Byron. The novelist Mary Shelley (née Godwin) was his second wife. Shelley's unconventional life and uncompromising idealism, combined with his strong disapproving voice, made him a marginalized figure during his life, important in a fairly small circle of admirers, and opened him to criticism as well as praise afterward.

#English #Romanticism #XIXCentury

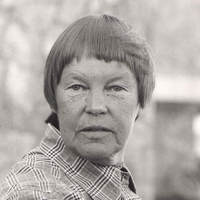

Anne Sexton (November 9, 1928, Newton, Massachusetts – October 4, 1974, Weston, Massachusetts) was an American poetese, known for her highly personal, confessional verse. She won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry in 1967. Themes of her poetry include her suicidal tendencies, long battle against depression and various intimate details from her private life, including her relationships with her husband and children. Sexton suffered from severe mental illness for much of her life, her first manic episode taking place in 1954.

#Americans #Suicide #Women #XXCentury

Sheldon Allan Shel Silverstein (September 25, 1930 – May 10, 1999), was an American poet, singer-songwriter, cartoonist, screenwriter, and author of children's books. He styled himself as Uncle Shelby in some works. Translated into more than 30 languages, his books have sold over 20 million copies.

#Americans #Children #Jews #XXCentury

Siegfried Loraine Sassoon (8 September 1886 – 1 September 1967) was an English poet, author and soldier. Decorated for bravery on the Western Front, he became one of the leading poets of the First World War. His poetry both described the horrors of the trenches, and satirised the patriotic pretensions of those who, in Sassoon's view, were responsible for a vainglorious war. He later won acclaim for his prose work, notably his three-volume fictionalised autobiography, collectively known as the "Sherston Trilogy". Motivated by patriotism, Sassoon joined the British Army just as the threat of World War I was realised, and was in service with the Sussex Yeomanry on the day the United Kingdom declared war (4 August 1914). He broke his arm badly in a riding accident and was put out of action before even leaving England, spending the spring of 1915 convalescing.

Hello and welcome. I don't know what brought you to my profile, but I do hope you enjoy my few pieces. I lack form and style, and could care less about using either in my poetry to be quite frank. I write my poetry from the heart (sorry for the -true- cliché), it is my escape, and I do hope that my words can reach others. But that's enough about me, take a look at a few of my poems if you so desire and send me critiques/commentary if you feel inclined to do so. Thanks for considering viewing my page as being worth your time.

Dora Maria Sigerson Shorter (16 August 1866 – 6 January 1918) was an Irish poet and sculptor, who after her marriage in 1895 wrote under the name Dora Sigerson Shorter. She was born in Dublin, Ireland, the daughter of George Sigerson, a surgeon and writer, and Hester (née Varian), also a writer. She was a major figure of the Irish Literary Revival, publishing many collections of poetry from 1893. Her friends included Katharine Tynan, Rose Kavanagh and Alice Furlong, writers and poets. In 1895 she married Clement King Shorter, an English journalist and literary critic. They lived together in London, until her death at age 51 from undisclosed causes.

#Irish #Women #XIXCentury #XXCentury

Edmund Spenser (c. 1552 – 13 January 1599) was an English poet best known for The Faerie Queene, an epic poem and fantastical allegory celebrating the Tudor dynasty and Elizabeth I. He is recognised as one of the premier craftsmen of Modern English verse in its infancy, and is considered one of the greatest poets in the English language.

#English #Renaissance #XVICentury

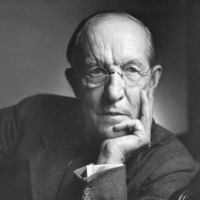

Wallace Stevens was born in Reading, Pennsylvania, on October 2, 1879. He attended Harvard University as an undergraduate from 1897 to 1900. He planned to travel to Paris as a writer, but after a working briefly as a reporter for the New York Herald Times, he decided to study law. He graduated with a degree from New York Law School in 1903 and was admitted to the U.S. Bar in 1904. He practised law in New York City until 1916. Though he had serious determination to become a successful lawyer, Stevens had several friends among the New York writers and painters in Greenwich Village, including the poets William Carlos Williams, Marianne Moore, and E. E. Cummings. In 1914, under the pseudonym "Peter Parasol," he sent a group of poems under the title "Phases" to Harriet Monroe for a war poem competition for Poetry magazine. Stevens did not win the prize, but was published by Monroe in November of that year. Stevens moved to Connecticut in 1916, having found employment at the Hartford Accident and Indemnity Co., of which he became vice president in 1934. He had began to establish an identity for himself outside the world of law and business, however, and his first book of poems, Harmonium, published in 1923, exhibited the influence of both the English Romantics and the French symbolists, an inclination to aesthetic philosophy, and a wholly original style and sensibility: exotic, whimsical, infused with the light and color of an Impressionist painting. For the next several years, Stevens focused on his business life. He began to publish new poems in 1930, however, and in the following year, Knopf published an second edition of Harmonium, which included fourteen new poems and left out three of the decidedly weaker ones. More than any other modern poet, Stevens was concerned with the transformative power of the imagination. Composing poems on his way to and from the office and in the evenings, Stevens continued to spend his days behind a desk at the office, and led a quiet, uneventful life. Though now considered one of the major American poets of the century, he did not receive widespread recognition until the publication of his Collected Poems, just a year before his death. His major works include Ideas of Order (1935), The Man With the Blue Guitar (1937), Notes Towards a Supreme Fiction (1942), and a collection of essays on poetry, The Necessary Angel (1951). Stevens died in Hartford in 1955. Poetry Harmonium (1923) Ideas of Order (1935) Owl's Clover (1936) The Man With the Blue Guitar (1937) Notes Towards a Supreme Fiction (1942) Parts of a World (1942) Esthétique du Mal (1945) Three Academic Pieces (1947) Transport to Summer (1947) Primitive Like an Orb (1948) Auroras of Autumn (1950) Collected Poems (1954) Opus Posthumous (1957) The Palm at the End of the Mind (1967) Prose The Necessary Angel (1951) Plays Three Travellers Watch the Sunrise (1916) Carlos Among the Candles (1917) References Poets.org — http://www.poets.org/poet.php/prmPID/124

#Americans Modern

Charlotte Turner Smith (4 May 1749– 28 October 1806) was an English Romantic poet and novelist. She initiated a revival of the English sonnet, helped establish the conventions of Gothic fiction, and wrote political novels of sensibility. Smith was born into a wealthy family and received a typical education for a woman during the late 18th century. However, her father’s reckless spending forced her to marry early. In a marriage that she later described as prostitution, she was given by her father to the violent and profligate Benjamin Smith. Their marriage was deeply unhappy, although they had twelve children together. Charlotte joined Benjamin in debtor’s prison, where she wrote her first book of poetry, Elegiac Sonnets. Its success allowed her to help pay for Benjamin’s release. Benjamin’s father attempted to leave money to Charlotte and her children upon his death, but legal technicalities prevented her from ever acquiring it. Charlotte Smith eventually left Benjamin and began writing to support their children. Smith’s struggle to provide for her children and her frustrated attempts to gain legal protection as a woman provided themes for her poetry and novels; she included portraits of herself and her family in her novels as well as details about her life in her prefaces. Her early novels are exercises in aesthetic development, particularly of the Gothic and sentimentality. “The theme of her many sentimental and didactic novels was that of a badly married wife helped by a thoughtful sensible lover” (Smith’s entry in British Authors Before 1800: A Biographical Dictionary Ed. Stanley Kunitz and Howard Haycraft. New York: H.W. Wilson, 1952. pg. 478.) Her later novels, including The Old Manor House, often considered her best, support the ideals of the French Revolution. Smith was a successful writer, publishing ten novels, three books of poetry, four children’s books, and other assorted works, over the course of her career. She always saw herself as a poet first and foremost, however, as poetry was considered the most exalted form of literature at the time. Scholars credit Smith with transforming the sonnet into an expression of woeful sentiment that would pave the way for poets such as Coleridge, Wordsworth, Shelly and Keats. Smith’s poetry and prose was praised by contemporaries such as Romantic poets William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge as well as novelist Walter Scott. Coleridge, in 1796, even remarked that “those sonnets appear to me the most exquisite, in which moral Sentiments, Affections, or Feelings, are deduced from, and associated with the scenery of Nature”. After 1798, Smith’s popularity waned and by 1803 she was destitute and ill—she could barely hold a pen. She had to sell her books to pay off her debts. In 1806, Smith died. Largely forgotten by the middle of the 19th century, her works have now been republished and she is recognized as an important Romantic writer. Early life Smith was born on 4 May 1749 in London and baptized on 12 June; she was the oldest child of well-to-do Nicholas Turner and Anna Towers. Her two younger siblings, Nicholas and Catherine Ann, were born within the next five years. Smith’s childhood was shaped by her mother’s early death (probably in giving birth to Catherine) and her father’s reckless spending. After losing his wife, Nicholas Turner travelled and the children were raised by Lucy Towers, their maternal aunt (when exactly their father returned is unknown). At the age of six, Charlotte went to school in Chichester and took drawing lessons from the painter George Smith. Two years later, she, her aunt, and her sister moved to London and she attended a girls school in Kensington where she learned dancing, drawing, music, and acting. She loved to read and wrote poems, which her father encouraged. She even submitted a few to the Lady’s Magazine for publication, but they were not accepted. Marriage and first publication Smith’s father encountered financial difficulties upon his return to England and he was forced to sell some of the family’s holdings and to marry the wealthy Henrietta Meriton in 1765. Smith entered society at the age of twelve, leaving school and being tutored at home. On 23 February 1765, at the age of fifteen, she married Benjamin Smith, the son of Richard Smith, a wealthy West Indian merchant and a director of the East India Company. The proposal was accepted for her by her father; forty years later, Smith condemned her father’s action, which she wrote had turned her into a “legal prostitute”. Smith’s marriage was unhappy. She detested living in commercial Cheapside (the family later moved to Southgate and Tottenham) and argued with her in-laws, who she believed were unrefined and uneducated. They, in turn, mocked her for spending time reading, writing, and drawing. Even worse, Benjamin proved to be violent, unfaithful, and profligate. Only her father-in-law, Richard, appreciated her writing abilities, although he wanted her to use them to further his business interests. Richard Smith owned plantations in Barbados and he and his second wife brought five slaves to England, who, along with their descendants, were included as part of the family property in his will. Although Charlotte Smith later argued against slavery in works such as The Old Manor House (1793) and “Beachy Head”, she herself benefited from the income and slave labor of Richard Smith’s plantations. In 1766, Charlotte and Benjamin had their first child, who died the next year just days after the birth of their second, Benjamin Berney (1767–77). Between 1767 and 1785, the couple had ten more children: William Towers (born 1768), Charlotte Mary (born c. 1769), Braithwaite (born 1770), Nicholas Hankey (1771–1837), Married Anni Petroose (1779–1843), Charles Dyer (born 1773), Anna Augusta (1774–94), Lucy Eleanor (born 1776), Lionel (1778–1842), Harriet (born c. 1782), and George (born c. 1785). Only six of Smith’s children survived her. Smith assisted in the family business that her husband had abandoned by helping Richard Smith with his correspondence. She persuaded Richard to set Benjamin up as a gentleman farmer in Hampshire and lived with him at Lys Farm from 1774 until 1783. Worried about Charlotte’s future and that of his grandchildren and concerned that his son would continue his irresponsible ways, Richard Smith willed the majority of his property to Charlotte’s children. However, because he had drawn up the will himself, the documents contained legal problems. The inheritance, originally worth nearly £36,000, was tied up in chancery after his death in 1776 for almost forty years. Smith and her children saw little of it. (It has been proposed that this real case may have inspired the famous fictional case of Jarndyce and Jarndyce, in Dickens’s Bleak House.) In fact, Benjamin illegally spent at least a third of the legacy and ended up in King’s Bench Prison in December 1783. Smith moved in with him and it was in this environment that she wrote and published her first work, Elegiac Sonnets (1784). Elegiac Sonnets achieved instant success, allowing Charlotte to pay for their release from prison. Smith’s sonnets helped initiate a revival of the form and granted an aura of respectability to her later novels (poetry was considered the highest art form at the time). Smith revised Elegiac Poems several times over the years, eventually creating a two-volume work. Novelist After Benjamin Smith was released from prison, the entire family moved to Dieppe, France to avoid further creditors. Charlotte returned to negotiate with them, but failed to come to an agreement. She went back to France and in 1784 began translating works from French into English. In 1787 she published The Romance of Real Life, consisting of translated selections from François Gayot de Pitaval’s trials. She was forced to withdraw her other translation, Manon Lescaut, after it was argued that the work was immoral and plagiarized. In 1786, she published it anonymously. In 1785, the family returned to England and moved to Woolbeding House near Midhurst, Sussex. Smith’s relationship with her husband did not improve and on 15 April 1787, after twenty-two years of marriage, she left him. She wrote that she might “have been contented to reside in the same house with him”, had not “his temper been so capricious and often so cruel” that her “life was not safe”. When Charlotte left Benjamin, she did not secure a legal agreement that would protect her profits—he would have access to them under English primogeniture laws. Smith knew that her children’s future rested on a successful settlement of the lawsuit over her father-in-law’s will, therefore she made every effort to earn enough money to fund the suit and retain the family’s genteel status. Smith claimed the position of gentlewoman, signing herself “Charlotte Smith of Bignor Park” on the title page of Elegiac Sonnets. All of her works were published under her own name, “a daring decision” for a woman at the time. Her success as a poet allowed her to make this choice. Throughout her career, Smith identified herself as a poet. Although she published far more prose than poetry and her novels brought her more money and fame, she believed poetry would bring her respectability. As Sarah Zimmerman claimed in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, “She prized her verse for the role it gave her as a private woman whose sorrows were submitted only reluctantly to the public.” After separating from her husband, Smith moved to a town near Chichester and decided to write novels, as they would make her more money than poetry. Her first novel, Emmeline (1788), was a success, selling 1500 copies within months. She wrote nine more novels in the next ten years: Ethelinde (1789), Celestina (1791), Desmond (1792), The Old Manor House (1793), The Wanderings of Warwick (1794), The Banished Man (1794), Montalbert (1795), Marchmont (1796), and The Young Philosopher (1798). Smith began her career as a novelist during the 1780s at a time when women’s fiction was expected to focus on romance and to foreground “a chaste and flawless heroine subjected to repeated melodramatic distresses until reinstated in society by the virtuous hero”. Although Smith’s novels employed this structure, they also incorporated political commentary, particularly support of the French Revolution, through the voices of male characters. At times, she challenged the typical romance plot by including “narratives of female desire” or “tales of females suffering despotism”. Smith’s novels contributed to the development of Gothic fiction and the novel of sensibility. Smith’s novels are autobiographical. While a common device at the time, Antje Blank writes in The Literary Encyclopedia, “few exploited fiction’s potential of self-representation with such determination as Smith”. For example, Mr. and Mrs. Stafford in Emmeline are portraits of Charlotte and Benjamin. The prefaces to Smith’s novels told the story of her own struggles, including the deaths of several of her children. According to Zimmerman, "Smith mourned most publicly for her daughter Anna Augusta, who married an émigré... and died aged twenty in 1795." Smith’s prefaces positioned her as both a suffering sentimental heroine as well as a vocal critic of the laws that kept her and her children in poverty. Smith’s experiences prompted her to argue for legal reforms that would grant women more rights, making the case for these reforms through her novels. Smith’s stories showed the “legal, economic, and sexual exploitation” of women by marriage and property laws. Initially readers were swayed by her arguments and writers such as William Cowper patronized her. However, as the years passed, readers became exhausted by Smith’s stories of struggle and inequality. Public opinion shifted towards the view of poet Anna Seward, who argued that Smith was “vain” and “indelicate” for exposing her husband to “public contempt”. Smith moved frequently due to financial concerns and declining health. During the last twenty years of her life, she lived in: Chichester, Brighton, Storrington, Bath, Exmouth, Weymouth, Oxford, London, Frant, and Elstead. She eventually settled at Tilford, Surrey. Smith became involved with English radicals while she was living in Brighton from 1791 to 1793. Like them, she supported the French Revolution and its republican principles. Her epistolary novel Desmond tells the story of a man who journeys to revolutionary France and is convinced of the rightness of the revolution and contends that England should be reformed as well. The novel was published in June 1792, a year before France and England went to war and before the Reign of Terror began, which shocked the British public, turning them against the revolutionaries. Like many radicals, Smith criticized the French, but she still endorsed the original ideals of the revolution. In order to support her family, Smith had to sell her works, thus she was eventually forced to, as Blank claims, “tone down the radicalism that had characterised the authorial voice in Desmond and adopt more oblique techniques to express her libertarian ideals”. She therefore set her next novel, The Old Manor House (1793), during the American Revolutionary War, which allowed her to discuss democratic reform without directly addressing the French situation. However, in her last novel, The Young Philosopher (1798), Smith wrote a final piece of “outspoken radical fiction”. Smith’s protagonist leaves Britain for America, as there is no hope for a reform in Britain. The Old Manor House is "frequently deemed [Smith’s] best" novel for its sentimental themes and development of minor characters. Novelist Walter Scott labeled it as such and poet and critic Anna Laetitia Barbauld chose it for her anthology of The British Novelists (1810). As a successful novelist and poet, Smith communicated with famous artists and thinkers of the day, including musician Charles Burney (father of Frances Burney), poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, scientist and poet Erasmus Darwin, lawyer and radical Thomas Erskine, novelist Mary Hays, playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan, and poet Robert Southey. A wide array of periodicals reviewed her works, including the Anti-Jacobin Review, the Analytical Review, the British Critic, The Critical Review, the European Magazine, the Gentleman’s Magazine, the Monthly Magazine, and the Universal Magazine. Smith earned the most money between 1787 and 1798, after which she was no longer as popular; several reasons have been suggested for the public’s declining interest in Smith, including “a corresponding erosion of the quality of her work after so many years of literary labour, an eventual waning of readerly interest as she published, on average, one work per year for twenty-two years, and a controversy that attached to her public profile” as she wrote about the French revolution. Both radical and conservative periodicals criticized her novels about the revolution. Her insistence on pursuing the lawsuit over Richard Smith’s inheritance lost her several patrons. Also, her increasingly blunt prefaces made her less appealing to the public. In order to continue earning money, Smith began writing in less politically charged genres. She published a collection of tales, Letters of a Solitary Wanderer (1801–02) and the play What Is She? (1799, attributed). Her most successful new foray was into children’s literature: Rural Walks (1795), Rambles Farther (1796), Minor Morals (1798), and Conversations Introducing Poetry (1804). She also wrote two volumes of a history of England (1806) and A Natural History of Birds (1807, posthumous). She also returned to writing poetry and Beachy Head and Other Poems (1807) was published posthumously. Publishers did not pay as much for these works, however, and by 1803, Smith was poverty-stricken. She could barely afford food and had no coal. She even sold her beloved library of 500 books in order to pay off debts, but feared being sent to jail for the remaining £20. Illness and death Smith complained of gout for many years (it was probably rheumatoid arthritis), which made it increasingly difficult and painful for her to write. By the end of her life, it had almost paralyzed her. She wrote to a friend that she was “literally vegetating, for I have very little locomotive powers beyond those that appertain to a cauliflower”. On 23 February 1806, her husband died in a debtors’ prison and Smith finally received some of the money he owed her, but she was too ill to do anything with it. She died a few months later, on 28 October 1806, at Tilford and was buried at Stoke Church, Stoke Park, near Guildford. The lawsuit over her father-in-law’s estate was settled seven years later, on 22 April 1813, more than thirty-six years after Richard Smith’s death. Legacy Stuart Curran, the editor of Smith’s poems, has written that Smith is “the first poet in England whom in retrospect we would call Romantic”. She helped shape the “patterns of thought and conventions of style” for the period. Romantic poet William Wordsworth was the most affected by her works. He said of Smith in the 1830s that she was “a lady to whom English verse is under greater obligations than are likely to be either acknowledged or remembered”. By the second half of the 19th century, Smith was largely forgotten. Smith’s novels were republished again at the end of the 20th century, and “critics interested in the period’s women poets and prose writers, the Gothic novel, the historical novel, the social problem novel, and post-colonial studies” have argued for her significance as a writer. They looked to the contemporary documentation of her importance, discovering that she helped to revitalize the English sonnet, a fact recognized by Coleridge and others. Scott wrote that she “preserves in her landscapes the truth and precision of a painter” and poet and Barbauld claimed that Smith was the first to include sustained natural description in novels. It was not until 2008 however, that Smith’s entire prose collection became available to the general public. The edition contains each novel, the children’s stories and rural walks.

Welcome!! I have some emotions that have poetic symphony. I have some philosophy and my own stories and experiences in my own perspective; I have not judged them whether they are symmetrical with anyone or differentiate with others. I love writing about the bad luck I bear, the curse I fear and the death, ridiculously, I dare. I am grateful if you read - just like a sudden visitor of an unknown grave, someone came, stood, smiled and wished - "Rest In Peace". I was born in 1979, July 26 just at 12 am. I have no siblings. My two assets are everything, One I lost in 2004; My father; Still one I have, My mother. I am an MBA of University of Chittagong. I have served a lot of companies, Branded-Non branded, Multinational-Local, Authorized-Unknown, Financial-Not Financial, Established-Liquidated, Rising-Falling, Fortunate-Misfortune, Proprietor-Public etc. I like job devotion, I hate impose of discrimination, I am always leader at the beginning, however demonstrator at the ending. I belief Pragmatic is not Truth, Real means partial Truth. I decided to suicide. Before that, I want to keep my creation safe, where they will obscure but they will survive. I can never get the recognition. Better my creations need freedom anywhere in the world. So welcome again my friend before I decay. Thank you.

Algernon Charles Swinburne (5 April 1837– 10 April 1909) was an English poet, playwright, novelist, and critic. He wrote several novels and collections of poetry such as Poems and Ballads, and contributed to the famous Eleventh Edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica. A controversial figure at the time, Swinburne was a sado-masochist and alcoholic and was obsessed with the Middle Ages and lesbianism. Swinburne wrote about many taboo topics, such as lesbianism, cannibalism, sado-masochism, and anti-theism. His poems have many common motifs, such as the Ocean, Time, and Death. Several historical people are featured in his poems, such as Sappho ("Sapphics"), Anactoria ("Anactoria"), Jesus ("Hymn to Proserpine": Galilaee, La. “Galilean”) and Catullus ("To Catullus").

#Decadents #English #XIXCentury #XXCentury

I write to voice my thoughts, convey my feelings and exercise my communicative abilities. Much of my inspiration comes from the darker places; both in the world and in my mind. I present my poems publicly in the hope that someone, somewhere, will find solace and affinity through my words. Comment is free.

Sir Philip Sidney (30 November 1554– 17 October 1586) was an English poet, courtier, scholar, and soldier, who is remembered as one of the most prominent figures of the Elizabethan age. His works include Astrophel and Stella, The Defence of Poesy (also known as The Defence of Poetry or An Apology for Poetry), and The Countess of Pembroke’s Arcadia. Early life Born at Penshurst Place, Kent, he was the eldest son of Sir Henry Sidney and Lady Mary Dudley. His mother was the eldest daughter of John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland, and the sister of Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester. His younger brother, Robert was a statesman and patron of the arts, and was created Earl of Leicester in 1618. His younger sister, Mary, married Henry Herbert, 2nd Earl of Pembroke and was a writer, translator and literary patron. Sidney dedicated his longest work, the Arcadia, to her. After her brother’s death, Mary reworked the Arcadia, which became known as The Countess of Pembroke’s Arcadia. Philip was educated at Shrewsbury School and Christ Church, Oxford. Politics and marriage In 1572, in which year he turned 18, he was elected to Parliament as Member of Parliament for Shrewsbury and in the same year travelled to France as part of the embassy to negotiate a marriage between Elizabeth I and the Duc D’Alençon. He spent the next several years in mainland Europe, moving through Germany, Italy, Poland, the Kingdom of Hungary and Austria. On these travels, he met a number of prominent European intellectuals and politicians. Returning to England in 1575, Sidney met Penelope Devereux, the future Lady Rich; though much younger, she would inspire his famous sonnet sequence of the 1580s, Astrophel and Stella. Her father, Walter Devereux, 1st Earl of Essex, is said to have planned to marry his daughter to Sidney, but he died in 1576. In England, Sidney occupied himself with politics and art. He defended his father’s administration of Ireland in a lengthy document. More seriously, he quarrelled with Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, probably because of Sidney’s opposition to the French marriage, which de Vere championed. In the aftermath of this episode, Sidney challenged de Vere to a duel, which Elizabeth forbade. He then wrote a lengthy letter to the Queen detailing the foolishness of the French marriage. Characteristically, Elizabeth bristled at his presumption, and Sidney prudently retired from court. During a 1577 diplomatic visit to Prague, Sidney secretly visited the exiled Jesuit priest Edmund Campion. Sidney had returned to court by the middle of 1581 and in 1584 was MP for Kent. That same year Penelope Devereux was married, apparently against her will, to Lord Rich. Sidney was knighted in 1583. An early arrangement to marry Anne Cecil, daughter of Sir William Cecil and eventual wife of de Vere, had fallen through in 1571. In 1583, he married Frances, teenage daughter of Sir Francis Walsingham. In the same year, he made a visit to Oxford University with Giordano Bruno, who subsequently dedicated two books to Sidney. Literary writings His artistic contacts were more peaceful and more significant for his lasting fame. During his absence from court, he wrote Astrophel and Stella and the first draft of The Arcadia and The Defence of Poesy. Somewhat earlier, he had met Edmund Spenser, who dedicated The Shepheardes Calender to him. Other literary contacts included membership, along with his friends and fellow poets Fulke Greville, Edward Dyer, Edmund Spenser and Gabriel Harvey, of the (possibly fictitious) 'Areopagus’, a humanist endeavour to classicise English verse. Military activity Both through his family heritage and his personal experience (he was in Walsingham’s house in Paris during the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre), Sidney was a keenly militant Protestant. In the 1570s, he had persuaded John Casimir to consider proposals for a united Protestant effort against the Roman Catholic Church and Spain. In the early 1580s, he argued unsuccessfully for an assault on Spain itself. Promoted General of Horse in 1583, his enthusiasm for the Protestant struggle was given a free rein when he was appointed governor of Flushing in the Netherlands in 1585. In the Netherlands, he consistently urged boldness on his superior, his uncle the Earl of Leicester. He conducted a successful raid on Spanish forces near Axel in July, 1586. Injury and death Later that year, he joined Sir John Norris in the Battle of Zutphen, fighting for the Protestant cause against the Spanish. During the battle, he was shot in the thigh and died of gangrene 26 days later, at the age of 31. As he lay dying, Sidney composed a song to be sung by his deathbed. According to the story, while lying wounded he gave his water to another wounded soldier, saying, “Thy necessity is yet greater than mine”. This became possibly the most famous story about Sir Phillip, intended to illustrate his noble and gallant character. It also inspired evolutionary biologist John Maynard Smith to formulate a problem in signalling theory which is known as the Sir Philip Sidney game. Sidney’s body was returned to London and interred in the Old St. Paul’s Cathedral on 16 February 1587. The grave and monument were destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666. A modern monument in the crypt lists him among the important graves lost. Already during his own lifetime, but even more after his death, he had become for many English people the very epitome of a Castiglione courtier: learned and politic, but at the same time generous, brave, and impulsive. The funeral procession was one of the most elaborate ever staged, so much so that his father-in-law, Francis Walsingham, almost went bankrupt. Never more than a marginal figure in the politics of his time, he was memorialised as the flower of English manhood in Edmund Spenser’s Astrophel, one of the greatest English Renaissance elegies. An early biography of Sidney was written by his friend and schoolfellow, Fulke Greville. While Sidney was traditionally depicted as a staunch and unwavering Protestant, recent biographers such as Katherine Duncan-Jones have suggested that his religious loyalties were more ambiguous. Works * The Lady of May– This is one of Sidney’s lesser-known works, a masque written and performed for Queen Elizabeth in 1578 or 1579. * Astrophel and Stella– The first of the famous English sonnet sequences, Astrophel and Stella was probably composed in the early 1580s. The sonnets were well-circulated in manuscript before the first (apparently pirated) edition was printed in 1591; only in 1598 did an authorised edition reach the press. The sequence was a watershed in English Renaissance poetry. In it, Sidney partially nativised the key features of his Italian model, Petrarch: variation of emotion from poem to poem, with the attendant sense of an ongoing, but partly obscure, narrative; the philosophical trappings; the musings on the act of poetic creation itself. His experiments with rhyme scheme were no less notable; they served to free the English sonnet from the strict rhyming requirements of the Italian form. * The Countess of Pembroke’s Arcadia– The Arcadia, by far Sidney’s most ambitious work, was as significant in its own way as his sonnets. The work is a romance that combines pastoral elements with a mood derived from the Hellenistic model of Heliodorus. In the work, that is, a highly idealised version of the shepherd’s life adjoins (not always naturally) with stories of jousts, political treachery, kidnappings, battles, and rapes. As published in the sixteenth century, the narrative follows the Greek model: stories are nested within each other, and different storylines are intertwined. The work enjoyed great popularity for more than a century after its publication. William Shakespeare borrowed from it for the Gloucester subplot of King Lear; parts of it were also dramatised by John Day and James Shirley. According to a widely-told story, King Charles I quoted lines from the book as he mounted the scaffold to be executed; Samuel Richardson named the heroine of his first novel after Sidney’s Pamela. Arcadia exists in two significantly different versions. Sidney wrote an early version (the Old Arcadia) during a stay at Mary Herbert’s house; this version is narrated in a straightforward, sequential manner. Later, Sidney began to revise the work on a more ambitious plan, with much more backstory about the princes, and a much more complicated story line, with many more characters. He completed most of the first three books, but the project was unfinished at the time of his death—the third book breaks off in the middle of a sword fight. There were several early editions of the book. Fulke Greville published the revised version alone, in 1590. The Countess of Pembroke, Sidney’s sister, published a version in 1593, which pasted the last two books of the first version onto the first three books of the revision. In the 1621 version, Sir William Alexander provided a bridge to bring the two stories back into agreement. It was known in this cobbled-together fashion until the discovery, in the early twentieth century, of the earlier version. * An Apology for Poetry (also known as A Defence of Poesie and The Defence of Poetry)– Sidney wrote the Defence before 1583. It is generally believed that he was at least partly motivated by Stephen Gosson, a former playwright who dedicated his attack on the English stage, The School of Abuse, to Sidney in 1579, but Sidney primarily addresses more general objections to poetry, such as those of Plato. In his essay, Sidney integrates a number of classical and Italian precepts on fiction. The essence of his defence is that poetry, by combining the liveliness of history with the ethical focus of philosophy, is more effective than either history or philosophy in rousing its readers to virtue. The work also offers important comments on Edmund Spenser and the Elizabethan stage. * The Sidney Psalms– These English translations of the Psalms were completed in 1599 by Philip Sidney’s sister Mary. In popular culture * A memorial, erected in 1986 at the location where he was mortally wounded by the Spanish, can be found at the entrance of a footpath (" 't Gallee") located in front of the petrol station at the Warnsveldseweg 170. * In Arnhem, in front of the house in the Bakkerstraat 68, an inscription on the ground reads: "IN THIS HOUSE DIED ON THE 17 OCTOBER 1586 * SIR PHILIP SIDNEY * ENGLISH POET, DIPLOMAT AND SOLDIER, FROM HIS WOUNDS SUFFERED AT THE BATTLE OF ZUTPHEN. HE GAVE HIS LIFE FOR OUR FREEDOM". The inscription was unveiled on 17 October 2011, exactly 425 years after his death, in the presence of Philip Sidney, Viscount De L’Isle, a descendant of the brother of Philip Sidney. * The city of Sidney, Ohio, in the United States and a street in Zutphen, Netherlands, have been named after Sir Philip. A statue of him can be found in the park at the Coehoornsingel where, in the harsh winter of 1795, English and Hanoverian soldiers were buried who had died while retreating from advancing French troops. * Another statue of Sidney, by Arthur George Walker, forms the centrepiece of Shrewsbury School’s war memorial to alumni who died serving in World War I (unveiled 1924). * Sidney features as a friend of Giordano Bruno and an agent for Sir Francis Walsingham in the historical crime novels of S J Parris. * W. B. Yeats appears to allude to Sidney as a model of the ideal man in his poem “In Memory of Major Robert Gregory” when he calls Robert Gregory “Our Sidney and our perfect man”. * Sidney is referenced in the T.S. Eliot’s poem “A Cooking Egg”, published in his 1920 poetry collection Aras Vos Prec, where Eliot expresses a desire to speak with Sir Philip in heaven. * An extended sketch from Monty Python’s Flying Circus (Series 3, Episode 10 “E. Henry Thripshaw’s Disease”) featured a police officer, disguised as Sir Philip Sidney, finding himself transported to the Tudor era after raiding a pornography shop. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philip_Sidney

Arthur William Symons (28 February 1865– 22 January 1945), was a British poet, critic and magazine editor. Life Born in Milford Haven, Wales, of Cornish parents, Symons was educated privately, spending much of his time in France and Italy. In 1884–1886 he edited four of Bernard Quaritch’s Shakespeare Quarto Facsimiles, and in 1888–1889 seven plays of the “Henry Irving” Shakespeare. He became a member of the staff of the Athenaeum in 1891, and of the Saturday Review in 1894, but his major editorial feat was his work with the short-lived Savoy. His first volume of verse, Days and Nights (1889), consisted of dramatic monologues. His later verse is influenced by a close study of modern French writers, of Charles Baudelaire, and especially of Paul Verlaine. He reflects French tendencies both in the subject-matter and style of his poems, in their eroticism and their vividness of description. Symons contributed poems and essays to The Yellow Book, including an important piece which was later expanded into The Symbolist Movement in Literature, which would have a major influence on William Butler Yeats and T. S. Eliot. From late 1895 through 1896 he edited, along with Aubrey Beardsley and Leonard Smithers, The Savoy, a literary magazine which published both art and literature. Noteworthy contributors included Yeats, George Bernard Shaw, and Joseph Conrad. Symons was also a member of the Rhymer’s Club founded by Yeats in 1890. In 1892, The Minister’s Call, Symons’s first play, was produced by the Independent Theatre Society– a private club– to avoid censorship by the Lord Chamberlain’s Office. In 1902 Symons made a selection from his earlier verse, published as Poems. He translated from the Italian of Gabriele D’Annunzio The Dead City (1900) and The Child of Pleasure (1898), and from the French of Émile Verhaeren The Dawn (1898). To The Poems of Ernest Dowson (1905) he prefixed an essay on the deceased poet, who was a kind of English Verlaine and had many attractions for Symons. In 1909 Symons suffered a psychotic breakdown, and published very little new work for a period of more than twenty years. His Confessions: A Study in Pathology (1930) has a moving description of his breakdown and treatment. Verse Days and Nights (1889) Silhouettes (1892) London Nights (1895) Amoris victima (1897) Images of Good and Evil (1899) Poems in 2 volumes.(Contains: The Loom of Dreams in the second Volume, 1901), (1902) Lyrics (1903) An anthology of poetry published in the USA only. A Book of Twenty Songs (1905) The Fool of the World and other Poems (1906) Knave of Hearts (1913). Poems written between 1894 and 1908. Love’s Cruelty (1923) Jezebel Mort, and other poems (1931) Essays An Introduction to the study of Browning (1886) Studies in Two Literatures (1897) Aubrey Beardsley: An Essay with a Preface (1898) The Symbolist Movement in Literature (1899; 1919) Cities (1903), word-pictures of Rome, Venice, Naples, Seville, etc. Plays, Acting and Music (1903) Studies in Prose and Verse (1904) Studies in Seven Arts (1906). Figures of Several Centuries (1916) Cities and Sea-Coasts and Islands (1918) Studies in the Elizabethan Drama (1919) Charles Baudelaire: A Study (1920) Dramatis Personae (1925 - US edition 1923) From Toulouse-Lautrec to Rodin (1929) Studies in Strange Souls (1929) Confessions: A Study in Pathology (1930). A book containing Symons’s description of his breakdown and treatment. Wanderings (1931) A Study of Walter Pater (1932) Fiction Spiritual Adventures (1905). With an autobiographical sketch. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arthur_Symons

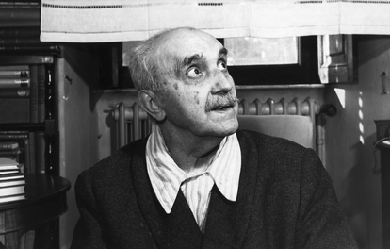

Jorge Agustín Nicolás Ruiz de Santayana y Borrás, known in English as George Santayana (December 16, 1863 – September 26, 1952), was a philosopher, essayist, poet, and novelist. Originally from Spain, Santayana was raised and educated in the United States from the age of eight and identified himself as an American, although he always kept a valid Spanish passport. He wrote in English and is generally considered an American man of letters. At the age of forty-eight, Santayana left his position at Harvard and returned to Europe permanently, never to return to the United States. His last wish was to be buried in the Spanish pantheon in Rome. Santayana is popularly known for aphorisms, such as “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it,” “Only the dead have seen the end of war,”, and the definition of beauty as “pleasure objectified”. Although an atheist, he always treasured the Spanish Catholic values, practices and world-view with which he was brought up. Santayana was a broad-ranging cultural critic spanning many disciplines.

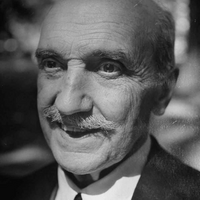

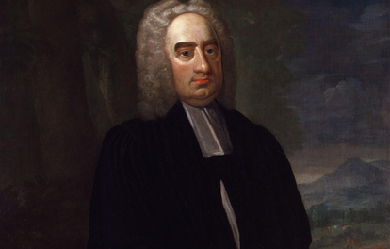

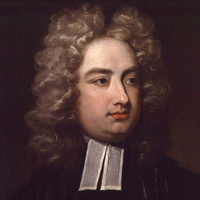

Jonathan Swift (30 November 1667– 19 October 1745) was an Anglo-Irish satirist, essayist, political pamphleteer (first for the Whigs, then for the Tories), poet and cleric who became Dean of St Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin. Swift is remembered for works such as Gulliver’s Travels, A Modest Proposal, A Journal to Stella, Drapier’s Letters, The Battle of the Books, An Argument Against Abolishing Christianity and A Tale of a Tub. He is regarded by the Encyclopædia Britannica as the foremost prose satirist in the English language, and is less well known for his poetry.

#Irish #XVIICentury #XVIIICentury

Duncan Campbell Scott (August 2, 1862– December 19, 1947) was a Canadian bureaucrat, poet and prose writer. With Charles G.D. Roberts, Bliss Carman, and Archibald Lampman, he is classed as one of Canada’s Confederation Poets. Scott was a Canadian lifetime civil servant who served as deputy superintendent of the Department of Indian Affairs from 1913 to 1932, and is better known today for advocating the assimilation of Canada’s First Nations peoples in that capacity. Life and legacy Scott was born in Ottawa, Ontario, the son of Rev. William Scott and Janet MacCallum. He was educated at Stanstead Wesleyan College. Early in life, he became an accomplished pianist. Scott wanted to be a doctor, but family finances were precarious, so in 1879 he joined the federal civil service. As the story goes, q:William Scott might not have money [but] he had connections in high places. Among his acquaintances was the prime minister, Sir John A. Macdonald, who agreed to meet with Duncan. As chance would have it, when Duncan arrived for his interview, the prime minister had a memo on his desk from the Indian Branch of the Department of the Interior asking for a temporary copying clerk. Making a quick decision while the serious young applicant waited in front of him, Macdonald wrote across the request: 'Approved. Employ Mr. Scott at $1.50.’ Scott "spent his entire career in the same branch of government, working his way up to the position of deputy superintendent of Indian Affairs in 1913, the highest non-elected position possible in his department. He remained in this post until his retirement in 1932.” Scott’s father also subsequently found work in Indian Affairs, and the entire family moved into a newly built house on 108 Lisgar St., where Duncan Campbell Scott would live for the rest of his life. In 1883 Scott met fellow civil servant, Archibald Lampman. It was the beginning of an instant friendship that would continue unbroken until Lampman’s death sixteen years later.... It was Scott who initiated wilderness camping trips, a recreation that became Lampman’s favourite escape from daily drudgery and family problems. In turn, Lampman’s dedication to the art of poetry would inspire Scott’s first experiments in verse. By the late 1880s Scott was publishing poetry in the prestigious American magazine, Scribner’s. In 1889 his poems “At the Cedars” and “Ottawa” were included in the pioneering anthology, Songs of the Great Dominion. Scott and Lampman "shared a love of poetry and the Canadian wilderness. During the 1890s the two made a number of canoe trips together in the area north of Ottawa.” In 1892 and 1893, Scott, Lampman, and William Wilfred Campbell wrote a literary column, “At the Mermaid Inn,” for the Toronto Globe. "Scott... came up with the title for it. His intention was to conjure up a vision of The Mermaid Inn Tavern in old London where Sir Walter Raleigh founded the famous club whose members included Ben Jonson, Beaumont and Fletcher, and other literary lights. In 1893 Scott published his first book of poetry, The Magic House and Other Poems. It would be followed by seven more volumes of verse: Labor and the Angel (1898), New World Lyrics and Ballads (1905), Via Borealis (1906), Lundy’s Lane and Other Poems (1916), Beauty and Life (1921), The Poems of Duncan Campbell Scott (1926) and The Green Cloister (1935). In 1894, Scott married Belle Botsford, a concert violinist, whom he had met at a recital in Ottawa. They had one child, Elizabeth, who died at 12. Before she was born, Scott asked his mother and sisters to leave his home (his father had died in 1891), causing a long-time rift in the family. In 1896 Scott published his first collection of stories, In the Village of Viger, "a collection of delicate sketches of French Canadian life. Two later collections, The Witching of Elspie (1923) and The Circle of Affection (1947), contained many fine short stories." Scott also wrote a novel, although it was not published until after his death (as The Untitled Novel, in 1979). After Lampman died in 1899, Scott helped publish a number of editions of Lampman’s poetry. Scott “was a prime mover in the establishment of the Ottawa Little Theatre and the Dominion Drama Festival.” In 1923 the Little Theatre performed his one-act play, Pierre; it was later published in Canadian Plays from Hart House Theatre (1926). His wife died in 1929. In 1931 he married poet Elise Aylen, more than 30 years his junior. After he retired the next year, "he and Elise spent much of the 1930s and 1940s travelling in Europe, Canada and the United States.” He died in December 1947 in Ottawa at the age of 85 and is buried in Ottawa’s Beechwood Cemetery. Indian Affairs Prior to taking up his position as head of the Department of Indian Affairs, in 1905 Scott was one of the Treaty Commissioners sent to negotiate Treaty No. 9 in Northern Ontario. Aside from his poetry, Scott made his mark in Canadian history as the head of the Department of Indian Affairs from 1913 to 1932. Even before Confederation, the Canadian government had adopted a policy of assimilation under the Gradual Civilization Act 1857. One biographer of Scott states that: The Canadian government’s Indian policy had already been set before Scott was in a position to influence it, but he never saw any reason to question its assumption that the 'red’ man ought to become just like the 'white’ man. Shortly after he became Deputy Superintendent, he wrote approvingly: ‘The happiest future for the Indian race is absorption into the general population, and this is the object and policy of our government.’... Assimilation, so the reasoning went, would solve the ‘Indian problem,’ and wrenching children away from their parents to 'civilize’ them in residential schools until they were eighteen was believed to be a sure way of achieving the government’s goal. Scott... would later pat himself on the back: ‘I was never unsympathetic to aboriginal ideals, but there was the law which I did not originate and which I never tried to amend in the direction of severity.’ while Scott himself wrote: I want to get rid of the Indian problem. I do not think as a matter of fact, that the country ought to continuously protect a class of people who are able to stand alone… Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic and there is no Indian question, and no Indian Department, that is the whole object of this Bill. In 1920, under Scott’s direction, and with the concurrence of the major religions involved in native education, an amendment to the Indian Act made it mandatory for all native children between the ages of seven and fifteen to attend school. Attendance at a residential school was made compulsory. Although a reading of Bill 14 states that no particular kind of school was stipulated. Scott was in favour of residential schooling for aboriginal children, as he believed removing them from the influences of home and reserve would hasten the cultural and economic transformation of the whole aboriginal population. In cases where a residential school was the only kind available, residential enrollment did become mandatory, and aboriginal children were compelled to leave their homes, their families and their culture, with or without their parents’ consent. However, in 1901, 226 of the 290 Indian schools across Canada were day schools, and by 1961, the 377 day schools far outnumbered the 56 residential institutions. CBC has reported that "In all, about 150,000 aboriginal, Inuit and Métis children were removed from their communities and forced to attend the schools." The 150,000 enrollment figure is an estimate not disputed by Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development, but it is not clear what percentage were “removed from their communities and forced to attend the schools.” A percentage of the residential schools were in or close by the children’s communities. Moreover, while many aboriginal parents distrusted the residential schools or preferred to raise and educate their children in a traditional manner, other parents willingly enrolled their children, partly from a belief that the schooling of the “white man” would benefit them, and partly from a knowledge that schools would provide shelter, food and clothing which dire conditions on the reserve could not provide. Harsh criticism has been leveled at Scott and the residential school system, as children who attended some of the more poorly maintained or administered schools lived in terrible conditions; in some cases the mortality rate exceeded fifty percent due to the spread of infectious disease. This situation was made worse by the federal policy that tied funding to enrollment numbers, which resulted in some schools enrolling sick children in order to boost their numbers. Echoing Scott’s desire to absorb aboriginals into the wider Canadian population, many residential and day schools strongly discouraged students from speaking their native language, and harsh punishments were administered. Corporal punishment was sometimes justified by the belief that it was the only way to “save souls”, “civilize” the native children and, in the residential schools, punish runaways who might make the school responsible for injury or death while trying to return home. Many reports of physical, sexual and psychological abuse in the residential schools have surfaced over the years. Because any kind of scandal coming out of the residential schools would have caused Indian Affairs, the churches and the government of the day much embarrassment, incidents of abuse were often discounted or covered up. When Scott retired, his “policy of assimilating the Indians had been so much in keeping with the thinking of the time that he was widely praised for his capable administration.” At the time, Scott was able to point to evidence of success in increasing enrollment and attendance, as the number of First Nations children enrolled in any school rose from 11,303 in 1912 to 17,163 in 1932. Residential school enrollment during the same period rose from 3,904 to 8,213. Actual attendance figures from all schools had also risen sharply, going from 64% of enrollment in 1920 to 75% in 1930, and Scott attributed this rise partly to Bill 14's section on compulsory attendance but also to a more positive attitude among First Nations people toward education. However, despite the encouraging statistics, Scott’s efforts to bring about assimilation through residential schools could be judged a failure, as many former students retained their language, went on to maintain and preserve their tribe’s culture, and refused to accept full Canadian citizenship when it was offered. Moreover, over the long history of the residential system, only a minority of all enrolled students went beyond the elementary grades, and many former students found themselves lacking the skills that would enable them to find employment on or off the reserve. Honours and awards Scott was honoured for his writing during and after his lifetime. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada in 1899 and served as its president from 1921 to 1922. The Society awarded him the second-ever Lorne Pierce Medal in 1927 for his contributions to Canadian literature. In 1934 he was made a Companion of the Order of St. Michael and St. George. He also received honorary degrees from the University of Toronto (Doctor of Letters in 1922) and Queen’s University (Doctor of Laws in 1939). In 1948, the year after his death, he was designated a Person of National Historic Significance. Poetry Scott’s "literary reputation has never been in doubt. He has been well represented in virtually all major anthologies of Canadian poetry published since 1900.” In Poets of the Younger Generation (1901), Scottish literary critic William Archer wrote of Scott: He is above everything a poet of climate and atmosphere, employing with a nimble, graphic touch the clear, pure, transparent colours of a richly-furnished palette.... Though it must not be understood that his talent is merely descriptive. There is a philosophic and also a romantic strain in it... There is scarcely a poem of Mr. Scott’s from which one could not cull some memorable descriptive passage.... As a rule Mr. Scott’s workmanship is careful and highly finished. He is before everything a colourist. He paints in lines of a peculiar and vivid translucency. But he is also a metrist of no mean skill, and an imaginative thinker of no common capacity. The Government of Canada biography of him says that: Although the quality of Scott’s work is uneven, he is at his best when describing the Canadian wilderness and Indigenous peoples. Although they constitute a small portion of his total output, Scott’s widely recognized and valued 'Indian poems’ cemented his literary reputation. In these poems, the reader senses the conflict that Scott felt between his role as an administrator committed to an assimilation policy for Canada’s Native peoples and his feelings as a poet, saddened by the encroachment of European civilization on the Indian way of life. “There is not a really bad poem in the book,” literary critic Desmond Pacey said of Scott’s first book, The Magic House and Other Poems, “and there are a number of extremely good ones.” The 'extremely good ones’ include the strange, dream-like sonnets of “In the House of Dreams.” “Probably the best known poem from the collection is ‘At the Cedars,’ a grim narrative about the death of a young man and his sweetheart during a log-jam on the Ottawa River. It is crudely melodramatic,... but its style—stark understatement, irregular lines, and abrupt rhymes—makes it the most experimental poem in the book.” His next book, Labour and the Angel, “is a slighter volume than The Magic House in size and content. The lengthy title poem makes dreary reading.... Of greater interest is his growing willingness to experiment with stanza form, variations in line length, use of partial rhyme, and lack of rhyme.” Notable new poems included “The Cup” and the sonnet “The Onandaga Madonna.” But arguably “the most memorable poem in the new collection” was the fantasy, “The Piper of Arll.” One person who long remembered that poem was future British Poet Laureate John Masefield, who read “The Piper of Arll” as a teenager and years later wrote to Scott: I had never (till that time) cared very much for poetry, but your poem impressed me deeply, and set me on fire. Since then poetry has been the one deep influence in my life, and to my love of poetry I owe all my friends, and the position I now hold. New World Lyrics and Ballads (1905) revealed “a voice that is sounding ever more different from the other Confederation Poets... his dramatic power is increasingly apparent in his response to the wilderness and the lives of the people who lived there.” The poetry included “On the Way to the Mission” and the much-anthologized “The Forsaken,” two of Scott’s best-known “Indian poems.” Lundy’s Lane and Other Poems (1916) seemed “to have been cobbled together at the insistence of his publishers, who wanted a collection of his work that had not been published in any previous volume.”. The title poem was one that had won Scott, "in the Christmas Globe contest of 1908,... the prize of one hundred dollars, offered for the best poem on a Canadian historical theme.". Other notable poems in the volume include the pretty lyric “A Love Song,” the long meditation, “The Height of Land,” and the even longer “Lines Written in Memory of Edmund Morris.” Anthologist John Garvin called the last “so original, tender and beautiful that it is destined to live among the best in Canadian literature.” “In his old age, Scott would look back upon Beauty and Life (1921) as his favourite among his volumes of verse," E.K. Brown tells us, adding: “In it most of the poetic kinds he cared about are represented.” There is a great diversity, from the moving war elegy “To a Canadian Aviator Who Died For His Country in France,” to the strange, apocalyptic “A Vision.” The Green Cloister, published after Scott’s retirement, "is a travelogue of the sites he visited in Europe with Elise: Lake Como, Ravelllo, Kensington Gardens, East Gloucester, etc.—descriptive and contemplative poems by an observant tourist. Those with a Canadian setting include two Indian poems of near-melodrama—'A Scene at Lake Manitou’ and 'At Gull Lake, August 1810'—that are in stark contrast to the overall serenity of the volume." More typical is the title poem, “Chiostro Verde.” The Circle of Affection (1947) contains 26 poems Scott had written since Cloister, and several prose pieces, including his Royal Society address on “Poetry and Progress.” It includes “At Delos,” which brings to mind the poet’s approaching death: There is no grieving in the world As beauty fades throughout the years: The pilgrim with the weary heart Brings to the grave his tears. Reputation as an assimilationist In 2003, Scott’s Indian Affairs legacy came under attack from Neu and Therrien: [Scott] took a romantic interest in Native traditions, he was after all a poet of some repute (a member of the Royal Society of Canada), as well as being an accountant and a bureaucrat . He was three people rolled into one confusing and perverse soul. The poet romanticized the whole 'noble savage’ theme, the bureaucrat lamented our inability to become civilized, the accountant refused to provide funds for the so-called civilization process. In other words, he disdained all ‘living’ Natives but “extolled the freedom of the savages”. According to Encyclopædia Britannica, Scott is "best known at the end of the 20th century," not for his writing, but “for advocating the assimilation of Canada’s First Nations peoples.” As part of their Worst Canadian poll, a panel of experts commissioned by Canada’s National History Society named Scott one of the Worst Canadians in the August 2007 issue of The Beaver. In his 2013 Conversations with a Dead Man: The Legacy of Duncan Campbell Scott, fabulist Mark Abley explored the paradoxes surrounding Scott’s career. Abley did not attempt to defend Scott’s work as a bureaucrat, but he showed that Scott is more than simply a one-dimensional villain. Controversy over Arc Poetry prize Arc Poetry Magazine renamed the annual “Archibald Lampman Award” (given to a poet in the National Capital Region) to the Lampman-Scott Award in recognition of Scott’s enduring legacy in Canadian poetry, with the first award under the new name given out in 2007. The winner of the 2008 award, Shane Rhodes, turned over half of the $1,500 prize money to the Wabano Centre for Aboriginal Health, a First Nations health centre. “Taking that money wouldn’t have been right, with what I’m writing about,” Rhodes said. The poet was researching First Nations history and found Scott’s name repeatedly referenced. In the words of a CBC News report, Rhodes felt “Scott’s legacy as a civil servant overshadows his work as a pioneer of Canadian poetry”. The editor of Arc Poetry Magazine, Anita Lahey, responded with a statement that she thought Scott’s actions as head of Indian Affairs were important to remember, but did not eclipse his role in the history of Canadian literature. “I think it matters that we’re aware of it and that we think about and talk about these things,” she said. “I don’t think controversial or questionable activities in the life of any artist or writer is something that should necessarily discount the literary legacy that they leave behind.” More recently, the magazine has stated on its website that "For the years 2007 through 2009, the Archibald Lampman Award merged with the Duncan Campbell Scott Foundation to become the Lampman-Scott Award in honour of two great Confederation Poets. This partnership came to an end in 2010, and the prize returned to its former identity as the Archibald Lampman Award for Poetry.” Publications Poetry * The Magic House and Other Poems. London: Methuen and Co. 1893. - The Magic House and Other Poems at Google Books * Labor and the Angel. Boston: Copeland & Day. 1898. – Labor and the Angel at Google Books– Labor and the Angel - Scholar’s Choice Edition at Google Books * New World Lyrics and Ballads. Toronto: Morang & Co. – New World Lyrics and Ballads at Google Books– New World Lyrics and Ballads - Scholar’s Choice Edition at Google Books * Via Borealis. Toronto: W. Tyrell. 1906. * Lundy’s Lane and Other Poems. Toronto: McClelland, Stewart & Stewart. 1916. - Lundy’s Lane and Other Poems at Google Books * To the Canadian Mothers and Three Other Poems. Toronto: Mortimer. 1917. * “After a Night of Storm” (PDF). Dalhousie Review 1 (2). 1921. * Beauty and Life. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. 1921. - Beauty and Life at Google Books * “Permanence” (PDF). Dalhousie Review 2 (4). 1923. * The Poems of Duncan Campbell Scott. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. 1926. - The Poems of Duncan Campbell Scott at Google Books * “By the Sea” (PDF). Dalhousie Review 7 (1). 1927. * The Green Cloister: Later Poems. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. 1935. - The Green Cloister: Later Poems at Google Books * Brown, E.K., ed. (1951). Selected Poems. Toronto: Ryerson. * Clever, Glenn, ed. (1974). Duncan Campbell Scott: Selected Poetry. Ottawa: Tecumseh. ISBN 978-0-9196-6252-0. * Souster, Raymond; Lochhead, Douglas, eds. (1985). Powassan’s Drum: Selected Poems of Duncan Campbell Scott. Ottawa: Tecumseh. ISBN 978-0-9196-6211-7. Fiction * In the Village of Viger. Boston: Copeland & Day. 1896. - In the Village of Viger at Google Books * The Witching of Elspie: A Book of Stories. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. 1923. * The Circle of Affection and Other Pieces in Prose and Verse. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. 1947. - mostly prose * Clever, Glenn, ed. (1987) [1972]. Selected Stories of Duncan Campbell Scott (revised 3rd ed.). Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press. ISBN 978-0-7766-0183-0. * Untitled Novel (posthumously published). Moonbeam, Ontario: Penumbra. 1979 [c. 1905]. ISBN 0-920806-04-X. * Ware, Tracy, ed. (2001). “The Uncollected Short Stories of Duncan Campbell Scott”. Duncan Campbell Scott. London, Ontario: Canadian Poetry Press. Non-fiction * John Graves Simcoe. Makers of Canada, volume VII. Toronto: Morang & Co. 1905. - John Graves Simcoe at Google Books * The Administration of Indian Affairs in Canada. Volume 3. Toronto: Canadian Institute of International Affairs. 1931. * Walter J. Phillips. Toronto: Ryerson. 1947. - Walter J. Phillips at Google Books * Bourinot, Arthur S., ed. (1960). More Letters of Duncan Campbell Scott. Ottawa: Bourinot. * Davies, Barrie, ed. (1979). At the Mermaid Inn: Wilfred Campbell, Archibald Lampman, Duncan Campbell Scott in the Globe 1892–93. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-6333-5. * Macdougall, Robert L., ed. (1983). The Poet and the Critic: A Literary Correspondence Between Duncan Campbell Scott and E.K. Brown. Ottawa: Carleton University Press. ISBN 978-0-8862-9013-9. Edited * Lampman, Archibald (1900). Scott, Duncan Campbell, ed. The Poems of Archibald Lampman. Toronto: Morang & Co. * Lampman, Archibald (1925). Scott, Duncan Campbell, ed. Lyrics of Earth: Sonnets and Ballads. Toronto: Musson. * Lampman, Archibald (1943). Scott, Duncan Campbell, ed. At the Long Sault and Other New Poems. Toronto: Ryerson. * Lampman, Archibald (1947). Scott, Duncan Campbell, ed. Selected Poems of Archibald Lampman. Toronto: Ryerson. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Duncan_Campbell_Scott

Hi, my name is, Paul Schreiner. I was born somewhere in the country of, Brasil. I don't know when or even where, I was born. Or who my biological parents may be. In fact, nobody in the American or the Brasilian government, really knows who I am or anything about me or my past. All that is known, is how I miraculously appeared in an orphanage with no birth certificate, due to my sister and I being kidnapped for sex trafficking. In 1988, my two loving parents flew down from America to Brasil, and adopted me. They gave me a name, a birthday, a home, a new country, and most of all, a family to call my own! Since I was a child, in a foreign country with no one to communicate with; I gravitated towards books, the Encyclopedia, history, and poetry. For some reason, I was able to comprehend the English language and it's structure more easily, through poetry. I love and appreciate poetry, because in a way, it explains an emotion, thoughts, or just life, in a way no other written structure can. I am so grateful for sights like these! It's sad, because poetry, I believe, is a dying art. Sights like these keep it alive and well for poets and fans, like ourselves. I hope you enjoy some of mine, almost as much as I enjoyed writing them! Go write on!!

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet, FRSE (15 August 1771– 21 September 1832) was a Scottish historical novelist, playwright and poet with many contemporary readers in Europe, Australia, and North America. Scott’s novels and poetry are still read, and many of his works remain classics of both English-language literature and of Scottish literature. Famous titles include Ivanhoe, Rob Roy, Old Mortality, The Lady of the Lake, Waverley, The Heart of Midlothian and The Bride of Lammermoor.