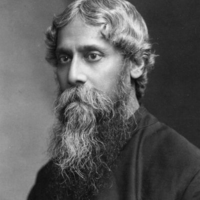

Rabindranath Tagoreα (7 May 1861 – 7 August 1941) was an Indian Bengali polymath who reshaped his region’s literature and music. Author of Gitanjali and its “profoundly sensitive, fresh and beautiful verse”, he became the first non-European to win the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1913. In translation his poetry was viewed as spiritual and mercurial; his seemingly mesmeric personality, flowing hair, and other-worldly dress earned him a prophet-like reputation in the West. His “elegant prose and magical poetry” remain largely unknown outside Bengal.

#IndianWriters #NobelPrize #XIXCentury #XXCentury

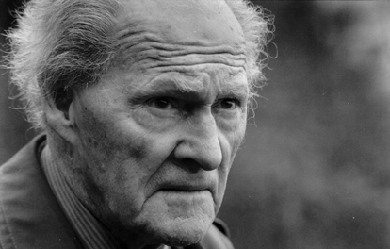

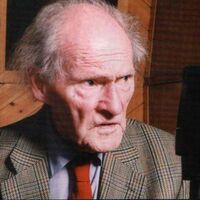

Ronald Stuart Thomas (29 March 1913 – 25 September 2000), published as R. S. Thomas, was a Welsh poet and Anglican priest who was noted for his nationalism, spirituality and deep dislike of the anglicisation of Wales. In 1955, John Betjeman, in his introduction to the first collection of Thomas’s poetry to be produced by a major publisher, Song at the Year's Turning, predicted that Thomas would be remembered long after Betjeman himself was forgotten. M. Wynn Thomas said: “He was the Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn of Wales because he was such a troubler of the Welsh conscience. He was one of the major English language and European poets of the 20th century.”

Sara Teasdale (August 8, 1884 – January 29, 1933) was an American lyric poet. She was born Sarah Trevor Teasdale in St. Louis, Missouri, and used the name Sara Teasdale Filsinger after her marriage in 1914. She had such poor health for so much of her childhood, home schooled until age 9, that it was only at age 10 that she was well enough to begin school. She started at Mary Institute in 1898, but switched to Hosmer Hall in 1899, graduating in 1903. I Shall Not Care WHEN I am dead and over me bright April Shakes out her rain-drenched hair, Tho' you should lean above me broken-hearted, I shall not care. I shall have peace, as leafy trees are peaceful When rain bends down the bough, And I shall be more silent and cold-hearted Than you are now.

#Americans #PulitzerPrize #Suicide #Women #XXCentury

Dear my followers...I'm going to be taking this page down shortly. I'm sorry but I can't keep up with it and to help ease some of the stress I have I can't keep it up. Thank you for everything though. Feel free to email me and keep writing, remember you all are beautiful and talented. Don't let this world get you down. Farewell my friends, For the last, XoxoTay.

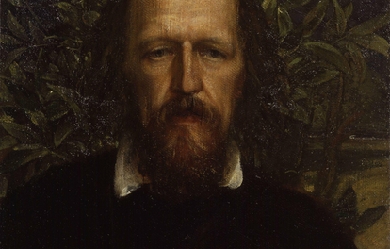

Alfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson, FRS (6 August 1809 – 6 October 1892) was Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom during much of Queen Victoria's reign and remains one of the most popular poets in the English language. A number of phrases from Tennyson’s work have become commonplaces of the English language, including “Nature, red in tooth and claw”, “'Tis better to have loved and lost / Than never to have loved at all”, “Theirs not to reason why, / Theirs but to do and die”, “My strength is as the strength of ten, / Because my heart is pure”, “Knowledge comes, but Wisdom lingers”, and “The old order changeth, yielding place to new”. He is the ninth most frequently quoted writer in The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations.

#English #Victorians #XIXCentury

I have never truly fit in with my peers. In early grade school, I had a good amount of friends my age, but by the third grade I was reading at least five grade levels above them, and had discovered my love of the written word. I immersed myself in literature as my peers immersed themselves in pop culture. My friends grew closer to each other, as I delved into my own world. A world of fiction and fantasy. As the girls fell in love with the boys, I fell in love with my favorite characters. My vocabulary expanded to the point where large, polysyllabic words were part of my normal speech, and I had to repeat and tailor my sentences to speak to my peers. This trouble communicating pushed me further from my friends and closer to my books. I chose to live my life between the pages. It was only a matter of time, I suppose, before I discovered what reading had given me. I had developed a command over the written word which I could use to create my own stories. I could share my own thoughts efficiently and creatively, and I could make it sound beautiful with the ways I could craft the syllables to my whims. Words became better friends to me than humans. Over time I have discovered myself as a writer and poet. However, I have not lost my interpersonal relationships. I have been in love, I have been hurt, I have learned to interact with my peers, and I have had the experience one receives in high school. I have taken my experiences, both real and read about, and told them with words. I have learned from life and literature, and developed a depth of maturity that separates me from my closest friends. They come to me for advice because I have an understanding of issues that has proved helpful to them, in the rare situation that they actually enact it. However, when it comes down to it, the superficiality of my fellow high school girls pushes me away. I have tried and failed to open up to my peers and have effectively, though rather unfortunately, created a vast distance between them and I. Now here I am, unable to connect with my peers on a satisfactory level, and I feel a deep loneliness despite however many people surround me at any time. I have, to my dismay, dug my own hole, -- the nature of this hole I am still unsure of, could it be my own grave, I don't know -- but I have opened up a bottle of hurt and placed myself in a crippling depression. My own ignorance has been my ruin. I put myself on a plain above my level, and when I finally came down, I came crashing down only to find that I had pushed myself too far away. I have friends whose sincerity I am irrevocably unconvinced, and I have my own thoughts. Thoughts full of pain and resentment. I used to, desperately, blame others for it, too. I blamed my peers for not being on my level, and even my doctors for treating the ADD which could have kept me back from becoming too knowledgable. However, now I see that I am alone because I put myself in solitary. It is as regrettable as the physical scars which I have made on my wrist and gut: the emotional scar I have carved in my own heart. PS: I have a bit of an affinity to Willow Trees...

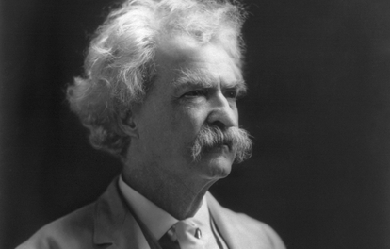

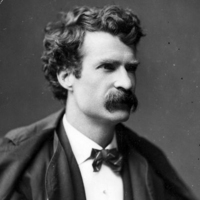

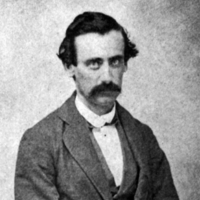

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835– April 21, 1910), better known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, entrepreneur, publisher, and lecturer. Among his novels are The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) and its sequel, the Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1885), the latter often called “The Great American Novel”.

Celia Laighton Thaxter (June 29, 1835 – August 25, 1894) was an American writer of poetry and stories. She was born in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Thaxter grew up in the Isles of Shoals, first on White Island, where her father, Thomas Laighton, was a lighthouse keeper, and then on Smuttynose and Appledore Islands. When she was sixteen, she married Levi Thaxter and moved to the mainland, residing first in Watertown, Massachusetts at a property his father owned. Celia died suddenly while on Appledore Island. She was buried not far from her cottage, which unfortunately burned in the 1914 fire that destroyed The Appledore House hotel.

Henry David Thoreau (July 12, 1817– May 6, 1862) was an American author, poet, philosopher, abolitionist, naturalist, tax resister, development critic, surveyor, and historian. A leading transcendentalist, Thoreau is best known for his book Walden, a reflection upon simple living in natural surroundings, and his essay Resistance to Civil Government (also known as Civil Disobedience), an argument for disobedience to an unjust state. He was a lifelong abolitionist, delivering lectures that attacked the Fugitive Slave Law while praising the writings of Wendell Phillips and defending abolitionist John Brown. Thoreau’s philosophy of civil disobedience later influenced the political thoughts and actions of such notable figures as Leo Tolstoy, Mahatma Gandhi, and Martin Luther King, Jr.

My name is Kailey Nicolaou (Titanium-Heart), my friends call me Kailz or Elly. My work is about my life struggles that have occurred and about faith, hope, depression etc. I have been writing poems, novels and songs since I was young to express my feelings, darkest and lightest thoughts. A lot of my poems are about my daughter Summer Rose Nicolaou who died on 18th December 2008, this was one of my darkest times that I have ever had. I do not speak to many people about my issues, so poetry is my release. I truly hope you enjoy my poetry and follow me for more of my poems, if you do follow me, I will defiantly take the time to look at your work and follow your page as well. Thank you.

Philip Edward Thomas (3 March 1878– 9 April 1917) was a British poet, essayist, and novelist. He is commonly considered a war poet, although few of his poems deal directly with his war experiences, and his career in poetry only came after he had already been a successful writer and literary critic. In 1915, he enlisted in the British Army to fight in the First World War and was killed in action during the Battle of Arras in 1917, soon after he arrived in France. Life and career Early life Thomas was born in Lambeth, London. He was educated at Battersea Grammar School, St Paul’s School in London and Lincoln College, Oxford. His family were mostly Welsh. In June 1899 he married Helen Berenice Noble (1878-1967), in Fulham, while still an undergraduate, and determined to live his life by the pen. He then worked as a book reviewer, reviewing up to 15 books every week. He was already a seasoned writer by the outbreak of war, having published widely as a literary critic and biographer as well writing on the countryside. He also wrote a novel, The Happy-Go-Lucky Morgans (1913), a “book of delightful disorder”. Thomas worked as literary critic for the Daily Chronicle in London and became a close friend of Welsh tramp poet W. H. Davies, whose career he almost single-handedly developed. From 1905, Thomas lived with his wife Helen and their family at Elses Farm near Sevenoaks, Kent. He rented to Davies a tiny cottage nearby, and nurtured his writing as best he could. On one occasion, Thomas even had to arrange for the manufacture, by a local wheelwright, of a makeshift wooden leg for Davies. Even though Thomas thought that poetry was the highest form of literature and regularly reviewed it, he only became a poet himself at the end of 1914 when living at Steep, East Hampshire, and initially published his poetry under the name Edward Eastaway. Frost in particular encouraged Thomas (then more famous as a critic) to write poetry, and their friendship was so close that the two planned to reside side by side in the United States. By August 1914, the village of Dymock in Gloucestershire had become the residence of a number of literary figures, including Lascelles Abercrombie, Wilfrid Gibson and American poet Robert Frost. Edward Thomas was a visitor at this time. Thomas immortalised the (now-abandoned) railway station at Adlestrop in a poem of that name after his train made a stop at the Cotswolds station on 24 June 1914, shortly before the outbreak of the First World War. War service Thomas enlisted in the Artists Rifles in July 1915, despite being a mature married man who could have avoided enlisting. He was unintentionally influenced in this decision by his friend Frost, who had returned to the U.S. but sent Thomas an advance copy of “The Road Not Taken”. The poem was intended by Frost as a gentle mocking of indecision, particularly the indecision that Thomas had shown on their many walks together; however, most audiences took the poem more seriously than Frost intended, and Thomas similarly took it seriously and personally, and it provided the last straw in Thomas’ decision to enlist. Thomas was promoted corporal, and in November 1916 was commissioned into the Royal Garrison Artillery as a second lieutenant. He was killed in action soon after he arrived in France at Arras on Easter Monday, 9 April 1917. To spare the feelings of his widow Helen, she was told the fiction of a “bloodless death” i.e. that Thomas was killed by the concussive blast wave of one of the last shells fired as he stood to light his pipe and that there was no mark on his body. However, a letter from his commanding officer Franklin Lushington written in 1936 (and discovered many years later in an American archive) states that in reality the cause of Thomas’ death was due to being “shot clean through the chest”. W. H. Davies was devastated by the death and his commemorative poem “Killed In Action (Edward Thomas)” was included in Davies’s 1918 collection “Raptures”. Thomas is buried in the Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery at Agny in France (Row C, Grave 43). Personal life Thomas was survived by his wife, Helen, their son Merfyn and their two daughters Bronwen and Myfanwy. After the war, Thomas’s widow, Helen, wrote about her courtship and early married life with Edward in the autobiography As it Was (1926); later she added a second volume, World Without End (1931). Myfanwy later said that the books had been written by her mother as a form of therapy to help lift herself from the deep depression into which she had fallen following Thomas’s death. Helen’s short memoir My Memory of W. H. Davies was published in 1973, after her own death. In 1988, Helen’s writings were gathered into a book published under the title Under Storm’s Wing, which included As It Was and World Without End as well as a selection of other short works by Helen and her daughter Myfanwy and six letters sent by Robert Frost to her husband. Commemorations Thomas is commemorated in Poets’ Corner, Westminster Abbey, London, by memorial windows in the churches at Steep and at Eastbury in Berkshire and with a blue plaque at 14 Lansdowne Gardens in Stockwell, south London, where he was born. There is also a plaque dedicated to him at 113 Cowley Road, Oxford, where he lodged before entering Lincoln College. East Hampshire District Council have created a “literary walk” at Shoulder of Mutton Hill in Steep dedicated to Thomas, which includes a memorial stone erected in 1935. The inscription includes the final line from one of his essays: “And I rose up and knew I was tired and I continued my journey.” As “Philip Edward Thomas poet-soldier” he is commemorated, alongside "Reginald Townsend Thomas actor-soldier died 1918", who is buried at the spot, and other family members, at the North East Surrey (Old Battersea) Cemetery. He is the subject of the biographical play The Dark Earth and the Light Sky by Nick Dear, which premiered at the Almeida Theatre, London in November 2012, with Pip Carter as Thomas and Hattie Morahan as his wife Helen. In February 2013 his poem “Words” was chosen as the poem of the week by Carol Rumens in The Guardian Poetry Thomas’s poems are noted for their attention to the English countryside and a certain colloquial style. The short poem In Memoriam exemplifies how his poetry blends the themes of war and the countryside. On 11 November 1985, Thomas was among 16 Great War poets commemorated on a slate stone unveiled in Westminster Abbey’s Poet’s Corner. The inscription, written by fellow poet Wilfred Owen, reads: “My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity.” Thomas was described by British Poet Laureate Ted Hughes as “the father of us all.” At least nineteen of his poems were set to music by the Gloucester composer Ivor Gurney. Selected works Poetry collections * Six Poems (under pseudonym Edward Eastaway) Pear Tree Press, 1916. * Poems, Holt, 1917, which included “The Sign-Post” * Last Poems, Selwyn & Blount, 1918. * Collected Poems, Selwyn & Blount, 1920. * Two Poems, Ingpen & Grant, 1927. * The Poems of Edward Thomas, ed. R. George Thomas, Oxford University Press, 1978. * Edward Thomas: A Mirror of England, ed. Elaine Wilson, Paul & Co., 1985. * Edward Thomas: Selected Poems, ed. Ian Hamilton, Bloomsbury, 1995. * The Poems of Edward Thomas, ed. Peter Sacks, Handsel Books, 2003. * The Annotated Collected Poems, ed. Edna Longley, Bloodaxe Books, 2008. Prose fiction * The Happy-Go-Lucky Morgans (novel), Duckworth, 1913. Prose * In Pursuit of Spring (travel) Thomas Nelson and Sons, April 1914 Essays and collections * Horae Solitariae, Dutton, 1902. * Oxford, A & C Black, 1903. * Beautiful Wales, Black, 1905. * The Heart of England, Dutton, 1906. * The South Country, Dutton, 1906 (reissued by Tuttle, 1993). * Rest and Unrest, Dutton, 1910. * Light and Twilight, Duckworth, 1911. * The Icknield Way, Constable, 1913. * The Last Sheaf, Jonathan Cape, 1928. References to Thomas by other writers * In 1918 W. H. Davies published his poem Killed In Action (Edward Thomas) to mark the personal loss of his close friend and mentor. * Many poems about Thomas by other poets can be found in the books Elected Friends: Poems For and About Edward Thomas, (1997, Enitharmon Press) edited by Anne Harvey, and Branch-Lines: Edward Thomas and Contemporary Poetry, (2007, Enitharmon Press) edited by Guy Cuthbertson and Lucy Newlyn. * Norman Douglas considered Thomas handicapped in life through lacking “a little touch of bestiality, a little je-m’en-fous-t-ism. He was too scrupulous”. * In his 1980 autobiography, Ways of Escape, Graham Greene references Thomas’s poem “The Other” (about a man who seems to be following his own double from hotel to hotel) in describing his own experience of being bedeviled by an imposter. * Edward Thomas’s Collected Poems was one of Andrew Motion’s ten picks for the poetry section of the “Guardian Essential Library” in October 2002. * In his 2002 novel Youth, J.M. Coetzee has his main character, intrigued by the survival of pre-modernist forms in British poetry, ask himself: “What happened to the ambitions of poets here in Britain? Have they not digested the news that Edward Thomas and his world are gone for ever?” In contrast, Irish critic Edna Longley writes that Thomas’s Lob, a 150-line poem, “strangely preempts The Waste Land through verses like: ”This is tall Tom that bore / The logs in, and with Shakespeare in the hall / Once talked". * In his 1995 novel, Borrowed Time, the author Robert Goddard bases the home of the main character at Greenhayes in the village of Steep, where Thomas lived from 1913. Goddard weaves some of the feeling from Thomas’s poems into the mood of the story and also uses some quotes from Thomas’s works. * Will Self’s 2006 novel, The Book of Dave, has a quote from The South Country as the book’s epigraph: “I like to think how easily Nature will absorb London as she absorbed the mastodon, setting her spiders to spin the winding sheet and her worms to fill in the graves, and her grass to cover it pitifully up, adding flowers—as an unknown hand added them to the grave of Nero.” * The children’s author Linda Newbery has published a novel, “Lob” (David Fickling Books, 2010, illustrated by Pam Smy) inspired by the Edward Thomas’ poem of the same name and containing oblique references to other work by him. * Woolly Wolstenholme, formerly of UK rock band Barclay James Harvest, has used a humorous variation of Thomas’ poem Adlestrop on the first song of his 2004 live album, Fiddling Meanly, where he imagines himself in a retirement home and remembers “the name” of the location where the album was recorded. The poem was read at Wolstenholme’s funeral on 19 January 2011. * Stuart Maconie in his book Adventures On The High Teas mentions Thomas and his poem “Adlestrop”. Maconie visits the now abandoned and overgrown station which was closed by Beeching in 1966. * Robert MacFarlane, in his 2012 book The Old Ways, critiques Thomas and his poetry in the context of his own explorations of paths and walking as an analogue of human consciousness. * In his 2012 novel Sweet Tooth, Ian McEwan has a character invoke Thomas’s poem “Adlestrop,” as a “sweet, old-fashioned thing” and an example of “the sense of pure existence, of being suspended in space and time, a time before a cataclysmic war.” * The last years of Thomas’s life are explored in A Conscious Englishman, a 2013 biographical novel by Margaret Keeping, published by StreetBooks. * Pat Barker’s 1995 WW1 novel, The Ghost Road, Booker Prize winner and the third novel of her Regeneration Trilogy, has as its opening epigraph 4 lines from 'Roads’. * 'Now all roads lead to France/ And heavy is the tread/ Of the living; but the dead/ Returning lightly dance:’ References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Thomas_(poet)

Dylan Marlais Thomas (27 October 1914 – 9 November 1953) was a Welsh poet and writer who wrote exclusively in English. In addition to poetry, he wrote short stories and scripts for film and radio, which he often performed himself. His public readings, particularly in America, won him great acclaim; his sonorous voice with a subtle Welsh lilt became almost as famous as his works. His best-known works include the “play for voices” Under Milk Wood and the celebrated villanelle for his dying father, “Do not go gentle into that good night”. Appreciative critics have also noted the craftsmanship and compression of poems such as “In my Craft or Sullen Art”, and the rhapsodic lyricism in “And death shall have no dominion” and “Fern Hill”.

Henry Timrod (December 8, 1829– October 7, 1867) was an American poet, often called the poet laureate of the Confederacy. Early life Timrod was born on December 8, 1829, in Charleston, South Carolina, to a family of German descent. His grandfather Heinrich Dimroth emigrated to the United States in 1765 and anglicized his name. His father, William Henry Timrod, was an officer in the Seminole Wars and a poet himself. In fact, he composed the following poem on the subject of his eldest son, Henry: Harry, my little blue-eyed boy, I love to have thee playing near; There’s music in thy shouts of joy, To a fond father’s ear. I love to see the lines of mirth Mantle thy cheeks and forehead fair, As if all the pleasures of the earth Had met to revel there. For gazing on thee do I sigh That those most happy years must flee; And thy full share of misery Must fall in life on thee. The elder Timrod died from tuberculosis on July 28, 1838, in Charleston, at the age of 44, leaving behind his wife of 25 years, Thyrza Prince Timrod, and their four children, the eldest of which was Adaline Rebecca, 14 years; Henry was nine. A few years later, their home burned down, leaving the family impoverished. He studied at the University of Georgia beginning in 1847 with the help of a financial benefactor. He was soon forced by illness to end his formal studies, however, and returned to Charleston. He took a position with a lawyer and planned to begin a law practice. From 1848 to 1853, he submitted a number of poems to the Southern Literary Messenger under the pen name Aglaus, where he attracted some attention for his abilities. He left his legal studies by December 1850, calling it “distasteful”, and focused more on writing and tutoring. He was a member of Charleston’s literati, and with John Dickson Bruns and Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve, could often be found in the company of their leader, William Gilmore Simms, whom they referred to as “Father Abbot,” from one of his novels. Career In 1856, he accepted a post as a teacher at the plantation of Colonel William Henry Cannon in the area that would later become Florence, South Carolina. Cannon had a single-room school building built in 1858 to provide for the education of the plantation children. The building measures “only about twelve by fifteen feet in size.” Among his students was the young lady who would later become his bride and the object of a number of his poems– the “fair Saxon” Kate Goodwin. These lines from “Katie”, the opening poem of The Poems of Henry Timrod (1873), are an example: The blackbird from a neighboring thorn With music brims the cup of morn, And in a thick, melodious rain The mavis pours her mellow strain! But only when my Katie’s voice Makes all the listening woods rejoice I hear—with cheeks that flush and pale— The passion of the nightingale! While teaching and tutoring, he continued also to publish his poems in literary magazines. In 1860, he published a small book, which, although a commercial failure, increased his fame. The best-known poem from the book was “A Vision of Poesy”. Civil War period With the outbreak of American Civil War, in a state of fervent patriotism, Timrod returned to Charleston to begin publishing his war poems, which drew many young men to enlist in the service of the Confederacy. His first poem of this period is “Ethnogenesis”, written in February, 1861, during the meeting of the first Confederate Congress at Montgomery, Alabama. Part of the poem was read aloud at this meeting: Hath not the morning dawned with added light? And shall not evening call another star Out of the infinite regions of the night To mark this day in Heaven? At last we are A nation among nations. And the world Shall soon behold in many a distant port Another flag unfurled! “A Cry to Arms”, “Carolina” and “The Cotton Boll” are other famous examples of his martial poetry. He was a frequent contributor of poems to Russell’s Magazine and to The Southern Literary Messenger. On March 1, 1862, Timrod enlisted into the military as a private in Company B, 30th South Carolina Regiment, and was detailed for special duty as a clerk at regimental headquarters, but his tuberculosis prevented much service, and he was sent home. After the bloody Battle of Shiloh, he tried again to live the camp life as a western war correspondent for the Charleston Mercury, but this too was short lived as he was not strong enough for the rugged task. He returned from the front and settled in Columbia, South Carolina, to become associate editor of the South Carolinian, a daily newspaper. Throughout 1864 he wrote many articles for the paper. In February 1864 he married his beloved Katie, and they soon had a son, Willie, born on Christmas Eve. This happy period in his life was short-lived. General Sherman’s troops invaded Columbia on February 17, 1865, one year and one day after his marriage. Due to the vigor of his editorials, he was forced into hiding, his home was burned, and the newspaper office was destroyed. Death The aftermath of war brought his family poverty and to him and his wife, increasing illness. He moved his family into his sister and mother’s home in Columbia. Then, his son Willie died on October 23, 1865. He expressed his sorrow in the poem “Our Willie”: ’Twas a merry Christmas when he came, Our little boy beneath the sod; And brighter burned the Christmas flame, And merrier sped the game Because within the house there lay A shape as tiny as a fay— The Christmas gift of God! He took a post as correspondent for a new newspaper based in Charleston, The Carolinian, but continued to reside in Columbia. Even after several months of work, however, he was never paid, and the paper folded. In economic desperation, he submitted poems written in his strongest style to northern periodicals, but all were coldly declined. Henry continued to seek work, but continued to be disappointed. Finally, in November, 1866, he was given an assistant clerkship under Governor James L. Orr’s staff member James S. Simons. This lasted less than a month, after which he was again dependent on charity and odd jobs to feed his family of women. Despite the harshly reduced circumstances, and mounting health problems, he was still able to produce highly regarded poetry. His “Memorial Ode”, composed in the Spring of 1867 “was sung at Magnolia Cemetery, Charleston, in May when the graves of the southern dead were decorated.” Sleep sweetly in your humble graves, Sleep, martyrs of a fallen cause; Though yet no marble column craves The pilgrim here to pause. In seeds of laurel in the earth The blossom of your flame is blown, And somewhere, waiting for its birth, The shaft is in the stone! Meanwhile, behalf the tardy years Which keep in trust your storied tombs, Behold! Your sisters bring their tears, And these memorial blooms. He finally succumbed to consumption Sunday morning, October 7, 1867, and was laid to rest in the churchyard at Trinity Episcopal Church in Columbia next to his son. Criticism and legacy Timrod’s friend and fellow poet, Paul Hamilton Hayne, posthumously edited and published The Poems of Henry Timrod, with more of Timrod’s more famous poems in 1873, including his "Ode: Sung on the Occasion of Decorating the Graves of the Confederate Dead at Magnolia Cemetery, Charleston, S.C., 1867" and “The Cotton Boll”. Later critics of Timrod’s writings, including Edd Winfield Parks and Guy A. Cardwell, Jr. of the University of Georgia, Jay B. Hubbell of Vanderbilt University and Christina Murphy, who completed a Ph.D. dissertation on Timrod at the University of Connecticut, have asserted that Timrod was one of the most important regional poets of nineteenth-century America and one of the most important Southern poets. In terms of achievement, Timrod is often compared to Sidney Lanier and John Greenleaf Whittier as poets who achieved significant stature by combining lyricism with a poetic capacity for nationalism. All three poets also explored the heroic ode as a poetic form. Today, Timrod’s poetry is included in most of the historical anthologies of American poetry, and he is regarded as a significant-though secondary-figure in 19th-century American literature. In 1901, a monument with a bronze bust of Timrod was dedicated in Charleston. The state’s General Assembly passed a resolution in 1911 instituting the verses of his poem “Carolina” as the lyrics of the official state anthem. In September 2006, an article for The New York Times noted similarities between Bob Dylan’s lyrics in the album, Modern Times and the poetry of Timrod. A wider debate developed in The Times as to the nature of “borrowing” within the folk tradition and in literature. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Timrod

William Makepeace Thackeray (18 July 1811– 24 December 1863) was an English novelist of the 19th century. He is famous for his satirical works, particularly Vanity Fair, a panoramic portrait of English society. He began as a satirist and parodist, writing works that displayed a sneaking fondness for roguish upstarts such as Becky Sharp in Vanity Fair, and the title characters of The Luck of Barry Lyndon and Catherine. In his earliest works, written under such pseudonyms as Charles James Yellowplush, Michael Angelo Titmarsh and George Savage Fitz-Boodle, he tended towards savagery in his attacks on high society, military prowess, the institution of marriage and hypocrisy.

I am the Traveller, I bring my gift to world. I have no name because I am a reflection of you, I want to show all people who read these poems that we connect inside the poetry. I am a man who is living his lifetime of happiness, joy, peace, laughter, fun, strength, courage and love. I believe we should always be happy because we remember that we are special and unique with gifts in this world that nobody has but you. We deserve the best and the world deserves the best of what we have to give. I know I have gift to share and I will share my gift with you, in hope it can help you too to share your own gift with the world.

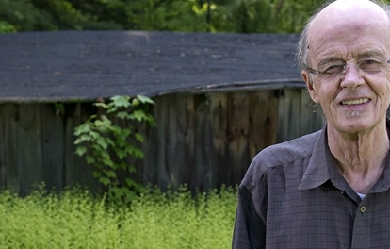

Francis Thompson (16 December 1859– 13 November 1907) was an English poet and ascetic. After attending college, he moved to London to become a writer, but could only find menial work and became addicted to opium, and was a street vagrant for years. A married couple read his poetry and rescued him, publishing his first book Poems in 1893. Thompson lived as an unbalanced invalid in Wales and at Storrington, but wrote three books of poetry, with other works and essays, before dying of tuberculosis in 1907. Life and work Thompson was born in Winckley Street, Preston, Lancashire. His father, Charles, was a doctor who had converted to Roman Catholicism, following his brother Edward Healy Thompson, a friend of Cardinal Manning. Thompson was educated at Ushaw College, near Durham, and then studied medicine at Owens College, now the University of Manchester. He took no real interest in his studies and never practised as a doctor, moving instead to London in 1885, to try to become a writer. Here he was reduced to selling matches and newspapers for a living. During this time, he became addicted to opium, which he first had taken as medicine for ill health. Thompson started living on the streets of Charing Cross and sleeping by the River Thames, with the homeless and other addicts. He was turned down by Oxford University, not because he was unqualified, but because of his drug addiction. Thompson attempted suicide in his nadir of despair, but was saved from completing the action through a vision which he believed to be that of a youthful poet Thomas Chatterton, who had committed suicide almost a century earlier. A prostitute– whose identity Thompson never revealed– befriended him, gave him lodgings and shared her income with him. Thompson was later to describe her in his poetry as his saviour. She soon disappeared, however, never to return, in his estimation because she feared she would taint his growing reputation. In 1888, he had been 'discovered’ after sending his poetry to the magazine Merrie England. He had been sought out by the magazine’s editors, Wilfrid and Alice Meynell. Recognizing the value of his work, the couple gave him a home and arranged for publication of his first book Poems in 1893. The book attracted the attention of sympathetic critics in the St James’s Gazette and other newspapers, and Coventry Patmore wrote a eulogistic notice in the Fortnightly Review of January 1894. Concerned about his opium addiction, which was at its height following his years on the streets, the Meynells sent Thompson to Our Lady of England Priory, Storrington. Thompson subsequently lived as an invalid at Pantasaph, Flintshire in Wales and at Storrington. A lifetime of extreme poverty, ill-health, and an addiction to opium took a heavy toll on Thompson, even though he found success in his last years. He would eventually die from tuberculosis at the age of 47, in the Hospital of St John and St Elizabeth and he is buried in St. Mary’s Roman Catholic Cemetery in Kensal Green. His tomb bears the last line from a poem he wrote for his godson - Look for me in the nurseries of Heaven. Style and influence His most famous poem, The Hound of Heaven, describes the pursuit of the human soul by God. This poem is the source of the phrase “with all deliberate speed,” used by the Supreme Court in Brown II, the remedy phase of the famous decision on school desegregation. A phrase in The Kingdom of God is the source of the title of Han Suyin’s novel Love Is a Many-Splendored Thing. In addition, Thompson wrote the most famous cricket poem, the nostalgic At Lord’s. He also wrote Sister Songs (1895), New Poems (1897), and a posthumously published essay, Shelley (1909). He wrote a treatise On Health and Holiness, dealing with the ascetic life, which was published in 1905. G. K. Chesterton said shortly after his death that “with Francis Thompson we lost the greatest poetic energy since Browning.” Among Thompson’s devotees was the young J. R. R. Tolkien, who purchased a volume of Thompson’s works in 1913-1914, and later said that it was an important influence on his own writing. The American novelist Madeleine L’Engle used a line from the poem The Mistress of Vision as the title of her last Vicki Austin novel, Troubling a Star. In 2011, Thompson’s life was the subject of the stage play and film script HOUND (Visions in the Life of the Poet Francis Thompson) by writer/director Chris Ward, which has been performed in various venues around London. Jack the Ripper suspect In his 1999 book Paradox, Australian author and educator Richard Patterson named Thompson as a possible identity of serial killer Jack the Ripper. On 6 November 2015, Patterson strengthened his claim. Home Thompson’s birthplace, in Winckley Street, Preston is marked by a memorial plaque. The inscription reads: "Francis Thompson poet was born in this house Dec 16 1859. Ever and anon a trumpet sounds, From the hid battlements of eternity." The home in Ashton-under-Lyne where Thompson lived from 1864 to 1885 was also marked with a blue plaque. In 2014, however, the building collapsed. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Thompson

“A day with out a smile is a day wasted.” i'm only 18 i love writing poems or just writing its my own way of self explaining myself in any type of emotional thoughts. I'm a crazy army brat i have moved from countries to states to cities , that has helped me with my writing only in the matter that i find and have more to write about

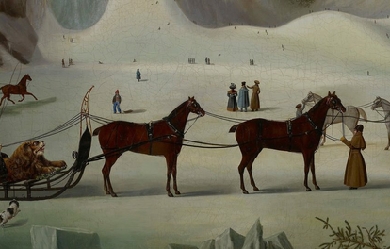

James Thomson (c. 11 September 1700– 27 August 1748) was a Scottish poet and playwright, known for his masterpiece The Seasons and the lyrics of “Rule, Britannia!”. Scotland, 1700–1725 James Thomson was born in Ednam in Roxburghshire around 11 September 1700 and baptised on 15 September. He was the fourth of nine children of Thomas Thomson and Beatrix Thomson (née Trotter). Beatrix Thomson was born in Fogo, Berwickshire and was a distant relation of the house of Hume. Thomas Thomson was the Presbyterian minister of Ednam until eight weeks after Thomson’s birth, when he was admitted as minister of Southdean, where Thomson spent most of his early years. Thomson may have attended the parish school of Southdean before going to the grammar school in Jedburgh in 1712. He failed to distinguish himself there. Shiels, his earliest biographer, writes: 'far from appearing to possess a sprightly genius, [Thomson] was considered by his schoolmaster, and those which directed his education, as being really without a common share of parts’. He was, however, encouraged to write poetry by Robert Riccaltoun (1691–1769), a farmer, poet and Presbyterian minister; and Sir William Bennet (d. 1729), a whig laird who was a patron of Allan Ramsay. While some early poems by Thomson survive, he burned most of them on New Year’s Day each year. Thomson entered the College of Edinburgh in autumn 1715, destined for the Presbyterian ministry. At Edinburgh he studied metaphysics, Logic, Ethics, Greek, Latin and Natural Philosophy. He completed his arts course in 1719 but chose not to graduate, instead entering Divinity Hall to become a minister. In 1716 Thomas Thomson died, with local legend saying that he was killed whilst performing an exorcism. At Edinburgh Thomson became a member of the Grotesque Club, a literary group, and he met his lifelong friend David Mallet. After the successful publication of some of his poems in the ‘’Edinburgh Miscellany’’ Thomson followed Mallet to London in February 1725 in an effort to publish his verse. London, 1725–1727 In London, Thomson became a tutor to the son of Charles Hamilton, Lord Binning, through connections on his mother’s side of the family. Through David Mallet, by 1724 a published poet, Thomson met the great English poets of the day including Richard Savage, Aaron Hill and Alexander Pope. Thomson’s mother died on 12 May 1725, around the time of his writing ‘Winter’, the first poem of ‘‘The Seasons’’. ‘Winter’ was first published in 1726 by John Millian, with a second edition being released (with revisions, additions and a preface) later the same year. By 1727, Thomson was working on Summer, published in February, and was working at Watt’s Academy, a school for young gentlemen and a bastion of Newtonian science. In the same year Millian published a poem by Thomson titled ‘A Poem to the Memory of Sir Isaac Newton’ (who had died in March). Leaving Watt’s academy, Thomson hoped to earn a living through his poetry, helped by his acquiring several wealthy patrons including Thomas Rundle, the countess of Hertford and Charles Talbot, 1st Baron Talbot. Later life, 1728–1748 He wrote Spring in 1728 and finally Autumn in 1730, when the set of four was published together as The Seasons. During this period he also wrote other poems, such as to the Memory of Sir Isaac Newton, and his first play, The Tragedy of Sophonisba (1729). The latter is best known today for its mention in Samuel Johnson’s Lives of the English Poets, where Johnson records that one 'feeble’ line of the poem - “O, Sophonisba, Sophonisba, O!” was parodied by the wags of the theatre as, “O, Jemmy Thomson, Jemmy Thomson, O!”. In 1730, he became tutor to the son of Sir Charles Talbot, then Solicitor-General, and spent nearly two years in the company of the young man on a tour of Europe. On his return Talbot arranged for him to become a secretary in chancery, which gave him financial security until Talbot’s death in 1737. Meanwhile, there appeared his next major work, Liberty (1734). In 1740, he collaborated with Mallet on the masque Alfred which was first performed at Cliveden, the country home of Frederick, Prince of Wales. Thomson’s words for “Rule Britannia”, written as part of that masque and set to music by Thomas Arne, became one of the best-known British patriotic songs - quite apart from the masque which is now virtually forgotten. The Prince gave him a pension of £100 per annum. He had also introduced him to George Lyttelton, who became his friend and patron. In later years, Thomson lived in Richmond upon Thames, and it was there that he wrote his final work The Castle of Indolence, which was published just before his untimely death on 27 August 1748. Johnson writes about Thomson’s death, “by taking cold on the water between London and Kew, he caught a disorder, which, with some careless exasperation, ended in a fever that put end to his life”. He is buried in St. Mary Magdalene church in Richmond. A dispute over the publishing rights to one of his works, The Seasons, gave rise to two important legal decisions (Millar v. Taylor; Donaldson v. Beckett) in the history of copyright. Thomson’s The Seasons was translated into German by Barthold Heinrich Brockes (1745). This translation formed the basis for a work with the same title by Gottfried van Swieten, which became the libretto for Haydn’s oratorio The Seasons. Memorials Thomson is one of the sixteen Scottish poets and writers appearing on the Scott Monument on Princes Street in Edinburgh. He appears on the right side of the east face. Editions Thomson, James & Bloomfield, Robert, The Seasons & Castles of Indolence / The Farmer’s Boy, Rural Tales, Banks of the Wye, &c. &c., (London: Scott, Webster & Geary, 1842). Gilfillan, Rev. George, Thomson’s Poetical Works, with Life, Critical Dissertation, and Explanatory Notes, Library Edition of the British Poets (1854). Thomson, James. The Seasons, by... A New Edition. Adorned with A Set of Engravings, from Original Paintings. Together with an Original Life of the Author, and a Critical Essay on the Seasons. by Robert Heron, (Perth: R. Morison, 1793) Thomson, James. Poems, edited by William Bayne, London: Walter Scott Publishing Co., [1900], (Series: The Canterbury poets). Thomson, James. The Seasons, edited with introduction and commentary by James Sambrook, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1981) ISBN 0-19-812713-8. Thomson, James. Liberty, The Castle of Indolence and other poems, edited with introduction and commentary by James Sambrook, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1986) ISBN 0-19-812759-6. Bayne, William, Life of James Thomson, Edinburgh: Oliphant, Anderson and Ferrier, 1898, ("Famous Scots Series"). References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Thomson_(poet,_born_1700)

I am the sun that shines when darkness tries to win. I am the prayer one will say when times are tough. I am the love in your eyes. I am the reflection in the mirror and sometimes I do what the mirror does. I am magic in your eyes. Whoever is reading this. I am the peace inside. Simply coz I am the image of God. Sifiso Alsonjnr my life is Poetry

Amable Tastu, nom de plume de Sabine Casimire Amable Voïart, née le 31 août 1798 à Metz et morte le 10 janvier 1885 à Palaiseau, est une femme de lettres française. Biographie Sabine Casimire Amable Voïart, née rue des clercs à Metz, est la fille de l’administrateur aux vivres de l’armée Jacques-Philippe Voïart et de Jeanne-Amable Bouchotte, sœur du ministre de la guerre, Jean-Baptiste Bouchotte. Elle perd sa mère en 1802 et en 1806, son père se remarie avec Anne-Élisabeth-Élise Petitpain, femme de lettres de Nancy qui partage avec Amable sa connaissance de l’anglais, de l’allemand et de l’italien. En 1816, elle épouse l’imprimeur perpignanais Joseph Tastu qui la trompe. Un an plus tard, elle met au monde un fils, Eugène. L’année suivante, en 1819, son mari quitte Perpignan et se rend à Paris pour reprendre l’imprimerie libérale des frères Beaudouin, au no 36 rue de Vaugirard. Sous son nom de plume d’Amable Tastu, elle écrit et publie des poèmes qui lui apportent la notoriété. C’est la muse romantique par excellence. En 1851, la rose Amable Tastu est créée en hommage. Après des années de prospérité, les affaires de son mari déclinent. La crise économique de 1830 a raison de son imprimerie et il fait faillite. Amable abandonne alors la poésie pour se livrer à des productions alimentaires afin de subvenir aux besoins de sa famille. Christine Planté précise: « Elle dut vivre de sa plume en rédigeant des travaux alimentaires pour combler l’indigence de son mari ruiné par la révolution de Juillet et inapte à se refaire ». Elle collabore régulièrement au Mercure de France et à La Muse française. Elle publie des ouvrages pédagogiques, des traductions, des sommes historiques, un Cours d’histoire de France, publié en accord avec le ministre de l’Instruction publique, un volume sur la littérature allemande, un autre sur la littérature italienne. Elle est également l’auteure de libretti pour des musiciens comme Saint-Saëns. En 1849, après la mort de son mari, elle suit son fils Eugène dans ses missions diplomatiques à Chypre et à Bagdad. En 1866, elle revient pour quelques années à Paris. En 1871, elle s’installe à Palaiseau où elle continue à mener une intense vie sociale et y meurt le 10 janvier 1885. Relations Elle est très appréciée de Lamartine, Sainte Beuve, Hugo, Chateaubriand, Marceline Desbordes-Valmore. Victor Hugo lui dédie son Moïse sur le Nil et Chateaubriand son Camoens. Sainte-Beuve compose en son honneur une élégie de 18 quatrains et lui consacre 16 pages dans ses Portraits contemporains.

#FemmesÉcrivains #ÉcrivainsFrançais

John Orley Allen Tate (November 19, 1899– February 9, 1979) was an American poet, essayist, social commentator, and Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress from 1943 to 1944. Life Early years Tate was born near Winchester, Kentucky, to John Orley Tate, a businessman, and Eleanor Parke Custis Varnell. In 1916 and 1917 Tate studied the violin at the Cincinnati Conservatory of Music. Vanderbilt University, Kenyon College and The Fugitives He began attending Vanderbilt University in 1918, where he met fellow poet Robert Penn Warren. Warren and Tate were invited to join an informal literary group of young Southern poets under the leadership of John Crowe Ransom; the group were known as the Fugitives. Tate contributed to the group’s magazine The Fugitive. The aim of the group, according to the critic J. A. Bryant, was "to demonstrate that a group of southerners could produce important work in the medium [of poetry], devoid of sentimentality and carefully crafted," and they wrote in the formalist tradition that valued the skillful use of meter and rhyme. Tate also joined Ransom to teach at Kenyon College in Gambier, Ohio. Some of his notable students there included the poets Robert Lowell and Randall Jarrell. Lowell’s early poetry was particularly influenced by Tate’s formalist brand of Modernism. 1920s In 1924, Tate moved to New York City where he met poet Hart Crane, with whom he had been exchanging correspondence for some time. Over a four-year period, he worked freelance for The Nation, contributed to the Hound & Horn, Poetry magazine, and others. To make ends meet, he worked as a janitor. (Some years later, he would also contribute articles to the conservative National Review.) During a summer visit with the poet Robert Penn Warren in Kentucky, he began a relationship with writer Caroline Gordon. The two lived together in Greenwich Village, but moved to “Robber Rocks”, a house in Patterson, New York, with friends Slater Brown and his wife Sue, Hart Crane, and Malcolm Cowley. Tate married Gordon in New York in May 1925. Their daughter Nancy was born in September. In 1928, along with others New York City friends, he went to Europe. In London, he visited with T. S. Eliot, whose poetry and criticism he greatly admired, and he also visited Paris. In 1928, Tate published his first book of poetry, Mr. Pope and Other Poems, which contained his most famous poem, “Ode to the Confederate Dead” (not to be confused with “Ode to the Confederate Dead at Magnolia Cemetery” by the Civil War poet Henry Timrod). That same year, Tate also published a biography Stonewall Jackson: The Good Soldier. Just before leaving for Europe in 1928, Tate described himself to John Gould Fletcher as “an enforced atheist”. He later told Fletcher, “I am an atheist, but a religious one—which means that there is no organization for my religion.” He regarded secular attempts to develop a system of thought for the modern world as misguided. “Only God,” he insisted, “can give the affair a genuine purpose.” In his essay “The Fallacy of Humanism” (1929), he criticized the New Humanists for creating a value system without investing it with any identifiable source of authority. “Religion is the only technique for the validation of values,” he wrote. Although he was attracted to Roman Catholicism, he deferred converting. Louis D. Rubin, Jr. observes that Tate may have waited “because he realized that for him at this time it would be only a strategy, an intellectual act”. In 1929, Tate published a second biography Jefferson Davis: His Rise and Fall. 1930s After two years abroad, he returned to the United States, and in 1930 was back in Tennessee. Here he took up residence in an antebellum mansion with an 85-acre estate attached, that had been bought for him by one of his brothers, “who had made a lot of northern money out of coal.” He resumed his senior position with the Fugitives. Along with fellow Fugitives, Warren and Ransom, as well as nine other Southern writers, Tate also joined the conservative political group known as the Southern Agrarians. The group was made up of 12 members who published essays on their political philosophy in the book I’ll Take My Stand published in 1930. Tate contributed the essay, “Remarks on the Southern Religion” to I’ll Take My Stand. This book was followed in 1938 by Who Owns America?, the Southern Agrarians’ response to The New Deal. During this time, Tate also became the de facto associate editor of The American Review, which was published and edited by Seward Collins. Tate believed The American Review could popularize the work of the Southern Agrarians. He objected to Collins’s open support of Fascists Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler, and condemned fascism in an article in The New Republic in 1936. Much of Tate’s major volumes of poetry were published in the 1930s, and the scholar David Havird describes this publication history in poetry as follows: By 1937, when he published his first Selected Poems, Tate had written all of the shorter poems upon which his literary reputation came to rest. This collection—which brought together work from two recent volumes, Poems: 1928-1931 (1932) and the privately printed The Mediterranean and Other Poems (1936), as well as the early Mr. Pope—included “Mother and Son,” “Last Days of Alice,” “The Wolves,” “The Mediterranean,” “Aeneas at Washington,” “Sonnets at Christmas,” and the final version of “Ode to the Confederate Dead.” In 1938 Tate published his only novel, The Fathers, which drew upon knowledge of his mother’s ancestral home and family in Fairfax County, Virginia. 1940s Tate and Gordon were divorced in 1945 and remarried in 1946. Though devoted to one another for life, they could not get along and later divorced again. Tate was a poet-in-residence at Princeton University until 1942. He founded the Creative Writing program at Princeton, and mentored Richard Blackmur, John Berryman, and others. In 1942, Tate assisted novelist and friend Andrew Lytle in transforming The Sewanee Review, America’s oldest literary quarterly, from a modest journal into one of the most prestigious in the nation. Tate and Lytle had attended Vanderbilt together prior to collaborating at The University of the South. 1950s In 1950, Tate converted to Roman Catholicism. He also married the poet Isabella Gardner in the early 1950s. 1960s While teaching at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, he met Helen Heinz, a nun enrolled in one of his courses and began an affair with her. Tate divorced Gardner and married Heinz in 1966. They moved to Sewanee, Tennessee. In 1967, Tate became the father of twin sons. The youngest died at eleven months from an accident. A third son was born in 1969. Tate died in Nashville, Tennessee ten years later. His papers are collected at the Firestone Library at Princeton University. Attitudes on race Literary scholars have questioned the relationship between the cultural attitudes of Modernist poets on issue such as race and the writing produced by these poets. The decade of the 1930s saw Tate’s most notable stances on matters that may or may not be connected to literary craft. For example, though Tate spoke well of the work of fellow Modernist poet Langston Hughes, in 1931, Tate pressured his colleague Thomas Mabry into canceling a reception for Hughes, comparing the idea of socializing with the black poet to meeting socially with his black cook. From the 1930s until as late as the 1960s, Tate held prejudices against both African-Americans and Jews. He expressed views against interracial marriage and miscegenation and refused to associate with African-American writers (like the aforementioned Langston Hughes). Up until the 1960s, Tate also believed in white supremacy. In 1933, Tate wrote a letter for Hound & Horn explaining his views on interracial sex. “The negro race is an inferior race....miscegenation due to a white woman and a negro man” threatened the white family. “Our purpose..is to keep the negro blood from passing into the white race.” According to the critic Ian Hamilton, Tate and his co-agrarians had been more than ready at the time to overlook the anti-Semitism and pro-Hitlerism of the American Review in order to promote their 'spiritual’ defence of the Deep South’s traditions. In a 1934 review, “A View of the Whole South” Tate reviews W. T. Couch’s “Culture in The South: A Symposium by Thirty-one Authors” and defends racial hegemony: “I argue it this way: the white race seems determined to rule the Negro race in its midst; I belong to the white race; therefore I intend to support white rule. Lynching is a symptom of weak, inefficient rule; but you can’t destroy lynching by fiat or social agitation; lynching will disappear when the white race is satisfied that its supremacy will not be questioned in social crises.” According to the poetry editor of The New Criterion, David Yezzi, Tate held the conventional social views of a white Southerner in 1934: an “inherited racism, a Southern legacy rooted in place and time that Tate later renounced.” Tate was born of a Scotch-Irish lumber manager whose business failures required moving several times per year, Tate said of his upbringing ""we might as well have been living, and I been born, in a tavern at a crossroads." However, his views on race were not passively incorporated; Thomas Underwood documents Tate’s pursuit of racist ideology: “Tate also drew ideas from nineteenth-century proslavery theorists such as Thomas Roderick Dew, a professor at The College of William and Mary, and William Harper, of the University of South Carolina—”We must revive these men, he said.” Bibliography References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Allen_Tate

* A creative minded Smart Girl.. * I do my thing and you do yours... I am not in this world to live up to your expectations, and you are not in this world to live up to mine. * You are you and I am I, and if by chance we find each other, then it is beautiful. If not, it cant be helped. * I am you; you are me. You are the waves; I am the ocean. Know this and be free, be divine.

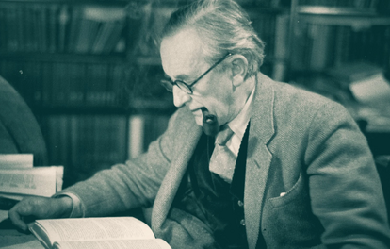

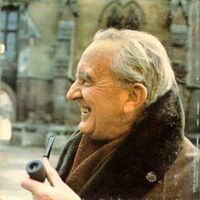

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien, 3 January 1892 – 2 September 1973) was an English writer, poet, philologist, and university professor who is best known as the author of the classic high-fantasy works The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, and The Silmarillion. He served Professor of Anglo-Saxon and English Language and Literature, and Fellow of Pembroke College, Oxford. He was at one time a close friend of C. S. Lewis—they were both members of the informal literary discussion group known as the Inklings. Tolkien was appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire by Queen Elizabeth II on 28 March 1972.

Arthur Seymour John Tessimond (Birkenhead, 19 July 1902– Chelsea, London 13 May 1962) was an English poet. He went to Birkenhead School until the age of 14, before being sent to Charterhouse School, but ran away at age 16. From 1922 to 1926 he attended the University of Liverpool, where he read English literature, French, Philosophy and Greek. He later moved to London where he worked in bookshops, and also as a copywriter. After avoiding military service in World War II, he later discovered he was unfit for service. He suffered from bipolar disorder, and received electro-convulsive therapy. He first began to publish in the 1920s in literary magazines. He was to see three volumes of poetry were published during his life: Walls of Glass in 1934, Voices in a Giant City in 1947 and Selections in 1958. He contributed several poems to a 1952 edition of Bewick’s Birds. He died in 1962 from a brain haemorrhage. In the mid-1970s he was the subject of a radio programme entitled Portrait of a Romantic. This, together with the publication of the posthumous selection Not Love Perhaps in 1972, increased interest in his work; and his poetry subsequently appeared in school books and anthologies. A 1985 anthology of his work The Collected Poems of A. S. J. Tessimond, edited by Hubert Nicholson, contains previously unpublished works. In 2010 a new collected poems, based closely on Nicholson’s edition, was published by Bloodaxe Books. In April 2010 an edition of Brian Patten’s series Lost Voices on BBC Radio Four was committed solely to Tessimond. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A._S._J._Tessimond

Namaste, Although I am now residing in sunny Florida, I grew up in Queens, New York. I am the eldest daughter of Jamaican, West Indian immigrants. We were a lively family, five siblings altogether with plenty of love and joviality to go around. From early on, I loved creating stories. My brothers and sisters also keenly enjoyed listening to them. But, being the natural artist, I preferred to retreat into the silence of my room surrounded by my dolls, where we would embark on all sorts of imaginative and adventurous tales. My siblings would listen with their ears glued to the bedroom door, occasionally a giggle of delight escaped from the other side of the door. This interest in story telling gradually metamorphosed into the art of penning poetry. Over the years I have written many poems. The fascinating thing about the imaginative process that I've observed, is that there seems to be some sort of bridge that connects us to the creative source. This is similar to what I experienced in my childhood, a quiet space within, beyond me where creative ideas flow endlessly. On another note, I am also an artist. But, LOL, all of my paintings tell a story too. My work is a visual and poetic diary of my spiritual journey. From the highest peaks in the Himalayas to many of the sacred ashrams in holy India I have been blessed with the opportunity to journey through that divine land eleven times. My spiritual quest began on June 6, 1970 with the birth of my daughter. During the birth I had an amazing out-of-body-experience which catapulted me out of ordinary three dimensional awareness into an astounding, metaphysical reality which I know survives and surpasses death, misery, joy, materialism and all that is dualistic and worldly. A space of being in which Pure Love, Life and Light exists Eternally. This event inspired me to explore the intriguing inner realms of Self through Yoga, Meditation, Rosicrucianism and other spiritually laden paths. I have written two books. The first, "Sai Rapture, The Ecstatic Journey of a Modern Day Gopi " portrays my spiritual journey. The second book, "108 Bhakti Kisses, The Ecstatic Poetry of a Modern Day Gopi" is a garland of poems celebrating the divine in everything.

Genevieve Taggard (November 28, 1894 Waitsburg, Washington– November 8, 1948 New York City) was an American poet. During the 1930s, sparked in part by the Great Depression, but also largely by her philanthropic upbringing and her commitment to socialism, her poetry began to reflect her political and social views much more prominently. During this time a Guggenheim Fellowship allowed her to spend a year in Majorca, Spain and Antibes, France. The experience of Spain in its time shortly before the Spanish Civil War gave further rise and inspiration to her cause of raising social and political awareness of civil rights issues.