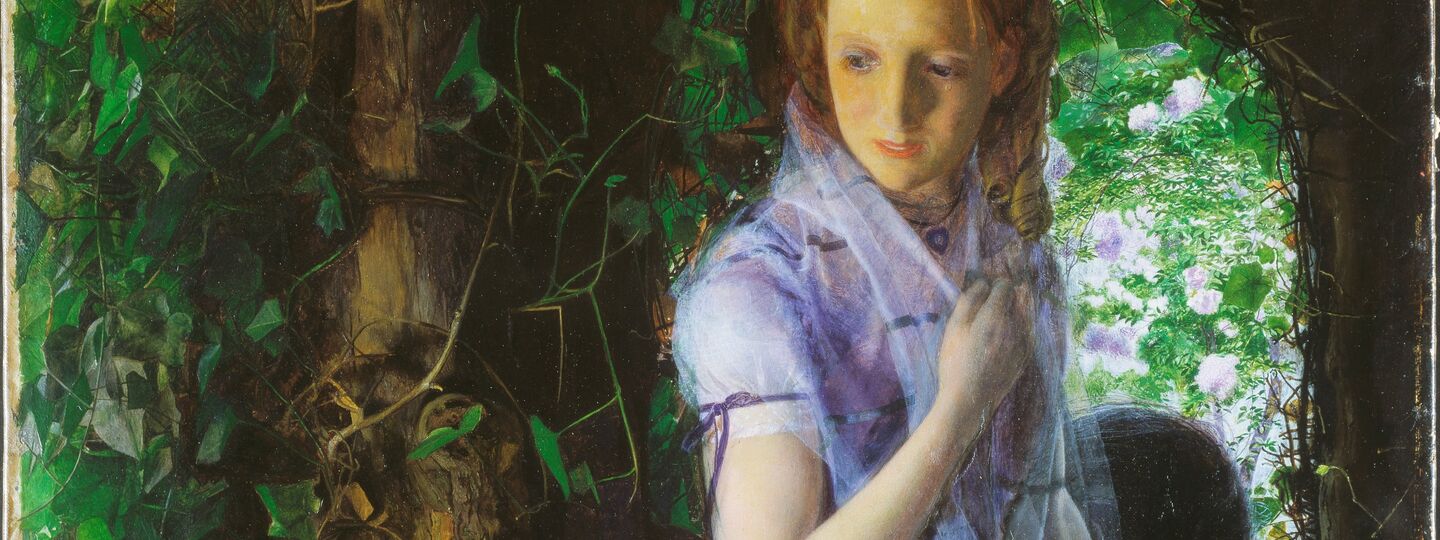

Marceline Desbordes-Valmore, née le 20 juin 1786 à Douai et morte le 23 juillet 1859 à Paris, est une poétesse française. Marceline est la fille de Catherine Lucas et Félix Desbordes, un peintre en armoiries, devenu cabaretier à Douai après avoir été ruiné par la Révolution. Fin 1801, après un séjour à Rochefort et un autre à Bordeaux, la jeune fille de 15 ans et sa mère embarquent pour la Guadeloupe afin de chercher une aide financière chez un cousin aisé, installé là-bas.

I am a very interesting person. I have been through hell and back, but I have decided to continuously go forward. I have been abused sexually, physically, and emotionally and I am a living testimony that can testify as to how a person can come out of any situation! Email me sometime to find out more questions or feel free to leave comments on my poems and entries. Thanks in advance!!

Michael Drayton (1563– 23 December 1631) was an English poet who came to prominence in the Elizabethan era. Early life Drayton was born at Hartshill, near Nuneaton, Warwickshire, England. Almost nothing is known about his early life, beyond the fact that in 1580 he was in the service of Thomas Goodere of Collingham, Nottinghamshire. Nineteenth– and twentieth-century scholars, on the basis of scattered allusions in his poems and dedications, suggested that Drayton might have studied at the University of Oxford, and been intimate with the Polesworth branch of the Goodere family. More recent work has cast doubt on those speculations. Literary career 1591–1602 In 1591 he produced his first book, The Harmony of the Church, a volume of spiritual poems, dedicated to Lady Devereux. It is notable for a version of the Song of Solomon, executed with considerable richness of expression. However, with the exception of forty copies, seized by the Archbishop of Canterbury, the whole edition was destroyed by public order. Nevertheless, Drayton published a vast amount within the next few years. In 1593 appeared Idea: The Shepherd’s Garland, a collection of nine pastorals, in which he celebrated his own love-sorrows under the poetic name of Rowland. The basic idea was expanded in a cycle of sixty-four sonnets, published in 1594, under the title of Idea’s Mirror, by which we learn that the lady lived by the river Ankor in Warwickshire. It appears that he failed to win his “Idea,” and lived and died a bachelor. It has been said Drayton’s sonnets possess a direct, instant, and universal appeal, by reason of their simple straightforward ring and foreshadowed the smooth style of Fairfax, Waller, and Dryden. Drayton was the first to bring the term ode, for a lyrical poem, to popularity in England and was a master of the short, staccato Anacreontics measure. Also in 1593 there appeared the first of Drayton’s historical poems, The Legend of Piers Gaveston, and the next year saw the publication of Matilda, an epic poem in rhyme royal. It was about this time, too, that he brought out Endimion and Phoebe, a volume which he never republished, but which contains some interesting autobiographical matter, and acknowledgments of literary help from Thomas Lodge, if not from Edmund Spenser and Samuel Daniel also. In his Fig for Momus, Lodge reciprocated these friendly courtesies. In 1596 Drayton published his long and important poem Mortimeriados, a very serious production in ottava rima. He later enlarged and modified this poem, and republished it in 1603 under the title of The Barons’ Wars. In 1596 also appeared another historical poem, The Legend of Robert, Duke of Normandy, with which Piers Gaveston was reprinted. In 1597 appeared England’s Heroical Epistles, a series of historical studies, in imitation of those of Ovid. These last poems, written in the heroic couplet, contain some of the finest passages in Drayton’s writings. 1603–1631 By 1597, the poet was resting on his laurels. It seems that he was much favoured at the court of Elizabeth, and he hoped that it would be the same with her successor. But when, in 1603, he addressed a poem of compliment to James I, on his accession, it was ridiculed, and his services rudely rejected. His bitterness found expression in a satire, The Owl (1604), but he had no talent in this kind of composition. Not much more entertaining was his scriptural narrative of Moses in a Map of his Miracles, a sort of epic in heroics printed the same year. In 1605 Drayton reprinted his most important works, his historical poems and the Idea, in a single volume which ran through eight editions during his lifetime. He also collected his smaller pieces, hitherto unedited, in a volume undated, but probably published in 1605, under the title of Poems Lyric and Pastoral; these consisted of odes, eclogues, and a fantastic satire called The Man in the Moon. Some of the odes are extremely spirited. In this volume he printed for the first time the famous Ballad of Agincourt. He had adopted as early as 1598 the extraordinary resolution of celebrating all the points of topographical or antiquarian interest in the island of Great Britain, and on this laborious work he was engaged for many years. At last, in 1613, the first part of this vast work was published under the title of Poly-Olbion, eighteen books being produced, to which the learned Selden supplied notes. The success of this great work, which has since become so famous, was very small at first, and not until 1622 did Drayton succeed in finding a publisher willing to undertake the risk of bringing out twelve more books in a second part. This completed the survey of England, and the poet, who had hoped “to crown Scotland with flowers,” and arrive at last at the Orcades, never crossed the Tweed. In 1627 he published another of his miscellaneous volumes, and this contains some of his most characteristic writing. It consists of the following pieces: The Battle of Agincourt, an historical poem in ottava rima (not to be confused with his ballad on the same subject), and The Miseries of Queen Margaret, written in the same verse and manner; Nimphidia, the Court of Faery, a most joyous and graceful little epic of fairyland; The Quest of Cinthia and The Shepherd’s Sirena, two lyrical pastorals; and finally The Moon Calf, a sort of satire. Nimphidia is the most critically acclaimed, along with his famous ballad on the battle of Agincourt; it is quite unique of its kind and full of rare fantastic fancy. The last of Drayton’s voluminous publications was The Muses’ Elizium in 1630. He died in London, was buried in Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey, and had a monument placed over him by the Countess of Dorset, with memorial lines attributed to Ben Jonson. Theatre Like other poets of his era, Drayton was active in writing for the theatre; but unlike Shakespeare, Ben Jonson, or Samuel Daniel, he invested little of his art in the genre. For a period of only five years, from 1597 to 1602, Drayton was a member of the stable of playwrights who supplied material for the theatrical syndicate of Philip Henslowe. Henslowe’s Diary links Drayton’s name with 23 plays from that period, and shows that Drayton almost always worked in collaboration with other Henslowe regulars, like Thomas Dekker, Anthony Munday, and Henry Chettle, among others. Of these 23 plays, only one has survived, that being Part 1 of Sir John Oldcastle, which Drayton composed in collaboration with Munday, Robert Wilson, and Richard Hathwaye. The text of Oldcastle shows no clear signs of Drayton’s hand; traits of style consistent through the entire corpus of his poetry (the rich vocabulary of plant names, star names, and other unusual words; the frequent use of original contractional forms, sometimes with double apostrophes, like “th’adult’rers” or “pois’ned’st”) are wholly absent from the text, suggesting that his contribution to the collaborative effort was not substantial. William Longsword, the one play that Henslowe’s Diary suggests was a solo Drayton effort, was never completed. (Drayton may have preferred the role of impresario to that of playwright; he was one of the lessees of the Whitefriars Theatre, together with Thomas Woodford, nephew of the playwright Thomas Lodge, when it was started in 1608. Around 1606, Drayton was also part of a syndicate that chartered a company of child actors, The Children of the King’s Revels. These may or may not have been the Children of Paul’s under a new name, since the latter group appears to have gone out of existence at about this time. The venture was not a success, dissolving in litigation in 1609.) Friendships Drayton was a friend of some of the most famous men of the age. He corresponded familiarly with Drummond; Ben Jonson, William Browne, George Wither and others were among his friends. There is a tradition that he was a friend of Shakespeare, supported by a statement of John Ward, once vicar of Stratford-on-Avon, that “Shakespear, Drayton and Ben Jonson had a merry meeting, and it seems, drank too hard, for Shakespear died of a feavour there contracted.” In one of his poems, an elegy or epistle to Mr Henry Reynolds, he has left some valuable criticisms on poets whom he had known. That he was a restless and discontented, as well as a worthy, man may be gathered from his own admissions. Editions In 1748 a folio edition of Drayton’s complete works was published under the editorial supervision of William Oldys, and again in 1753 there appeared an issue in four volumes quarto. But these were very unintelligently and inaccurately prepared. A complete edition of Drayton’s works with variant readings was projected by Richard Hooper in 1876, but was never carried to a conclusion; a volume of selections, edited by A. H. Bullen, appeared in 1883. See especially Oliver Elton, Michael Drayton (1906). A complete five-volume edition of Drayton’s work was published by Oxford in 1931-41 (revised 1961), edited by J. William Hebel, K. Tillotson and B. H. Newdigate. That and a two volume edition of Drayton’s poems published at Harvard in 1953, edited by John Buxton, are the only 20th century editions of his poems recorded by the Library of Congress. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michael_Drayton

Nací un día de enero de 1986, no sabía lo que venía. De hecho no sabía que existía. Hoy lo sé y me gusta saberlo, lo disfruto, me gusta. Soy payaso, acróbata y juego a cada instante. Tengo paciencia y ganas. Me gusta comunicarme de maneras atípicas, me gusta lo inentendible, el movimiento. Gracias por llegar aquí.

John Dryden (19 August [O.S. 9 August] 1631– 12 May [O.S. 1 May] 1700) was an English poet, literary critic, translator, and playwright who was made Poet Laureate in 1668. He is seen as dominating the literary life of Restoration England to such a point that the period came to be known in literary circles as the Age of Dryden. Walter Scott called him “Glorious John.” Early life Dryden was born in the village rectory of Aldwincle near Thrapston in Northamptonshire, where his maternal grandfather was Rector of All Saints. He was the eldest of fourteen children born to Erasmus Dryden and wife Mary Pickering, paternal grandson of Sir Erasmus Dryden, 1st Baronet (1553–1632) and wife Frances Wilkes, Puritan landowning gentry who supported the Puritan cause and Parliament. He was a second cousin once removed of Jonathan Swift. As a boy Dryden lived in the nearby village of Titchmarsh, Northamptonshire where it is likely that he received his first education. In 1644 he was sent to Westminster School as a King’s Scholar where his headmaster was Dr. Richard Busby, a charismatic teacher and severe disciplinarian. Having recently been re-founded by Elizabeth I, Westminster during this period embraced a very different religious and political spirit encouraging royalism and high Anglicanism. Whatever Dryden’s response to this was, he clearly respected the Headmaster and would later send two of his sons to school at Westminster. As a humanist public school, Westminster maintained a curriculum which trained pupils in the art of rhetoric and the presentation of arguments for both sides of a given issue. This is a skill which would remain with Dryden and influence his later writing and thinking, as much of it displays these dialectical patterns. The Westminster curriculum included weekly translation assignments which developed Dryden’s capacity for assimilation. This was also to be exhibited in his later works. His years at Westminster were not uneventful, and his first published poem, an elegy with a strong royalist feel on the death of his schoolmate Henry, Lord Hastings from smallpox, alludes to the execution of King Charles I, which took place on 30 January 1649, very near the school where Dr. Busby had first prayed for the King and then locked in his schoolboys to prevent their attending the spectacle. In 1650 Dryden went up to Trinity College, Cambridge. Here he would have experienced a return to the religious and political ethos of his childhood: the Master of Trinity was a Puritan preacher by the name of Thomas Hill who had been a rector in Dryden’s home village. Though there is little specific information on Dryden’s undergraduate years, he would most certainly have followed the standard curriculum of classics, rhetoric, and mathematics. In 1654 he obtained his BA, graduating top of the list for Trinity that year. In June of the same year Dryden’s father died, leaving him some land which generated a little income, but not enough to live on. Returning to London during The Protectorate, Dryden obtained work with Cromwell’s Secretary of State, John Thurloe. This appointment may have been the result of influence exercised on his behalf by his cousin the Lord Chamberlain, Sir Gilbert Pickering. At Cromwell’s funeral on 23 November 1658 Dryden processed with the Puritan poets John Milton and Andrew Marvell. Shortly thereafter he published his first important poem, Heroic Stanzas (1658), a eulogy on Cromwell’s death which is cautious and prudent in its emotional display. In 1660 Dryden celebrated the Restoration of the monarchy and the return of Charles II with Astraea Redux, an authentic royalist panegyric. In this work the interregnum is illustrated as a time of anarchy, and Charles is seen as the restorer of peace and order. Later life and career After the Restoration, as Dryden quickly established himself as the leading poet and literary critic of his day, he transferred his allegiances to the new government. Along with Astraea Redux, Dryden welcomed the new regime with two more panegyrics: To His Sacred Majesty: A Panegyric on his Coronation (1662) and To My Lord Chancellor (1662). These poems suggest that Dryden was looking to court a possible patron, but he was to instead make a living in writing for publishers, not for the aristocracy, and thus ultimately for the reading public. These, and his other nondramatic poems, are occasional—that is, they celebrate public events. Thus they are written for the nation rather than the self, and the Poet Laureate (as he would later become) is obliged to write a certain number of these per annum. In November 1662 Dryden was proposed for membership in the Royal Society, and he was elected an early fellow. However, Dryden was inactive in Society affairs and in 1666 was expelled for non-payment of his dues. On 1 December 1663 Dryden married the royalist sister of Sir Robert Howard—Lady Elizabeth. Dryden’s works occasionally contain outbursts against the married state but also celebrations of the same. Thus, little is known of the intimate side of his marriage. Lady Elizabeth bore three sons and outlived her husband. With the reopening of the theatres after the Puritan ban, Dryden wrote plays. His first play, The Wild Gallant, appeared in 1663 and was not successful but was still promising, and from 1668 on he was contracted to produce three plays a year for the King’s Company in which he became a shareholder. During the 1660s and '70s, theatrical writing was his main source of income. He led the way in Restoration comedy, his best-known work being Marriage à la Mode (1672), as well as heroic tragedy and regular tragedy, in which his greatest success was All for Love (1678). Dryden was never satisfied with his theatrical writings and frequently suggested that his talents were wasted on unworthy audiences. He thus was making a bid for poetic fame off-stage. In 1667, around the same time his dramatic career began, he published Annus Mirabilis, a lengthy historical poem which described the English defeat of the Dutch naval fleet and the Great Fire of London in 1666. It was a modern epic in pentameter quatrains that established him as the preeminent poet of his generation, and was crucial in his attaining the posts of Poet Laureate (1668) and historiographer royal (1670). When the Great Plague of London closed the theatres in 1665 Dryden retreated to Wiltshire where he wrote Of Dramatick Poesie (1668), arguably the best of his unsystematic prefaces and essays. Dryden constantly defended his own literary practice, and Of Dramatick Poesie, the longest of his critical works, takes the form of a dialogue in which four characters–each based on a prominent contemporary, with Dryden himself as 'Neander’—debate the merits of classical, French and English drama. The greater part of his critical works introduce problems which he is eager to discuss, and show the work of a writer of independent mind who feels strongly about his own ideas, ideas which demonstrate the breadth of his reading. He felt strongly about the relation of the poet to tradition and the creative process, and his best heroic play Aureng-zebe (1675) has a prologue which denounces the use of rhyme in serious drama. His play All for Love (1678) was written in blank verse, and was to immediately follow Aureng-Zebe. On 18 December 1679 he was attacked in Rose Alley near his home in Covent Garden by thugs hired by John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester, with whom he had a long-standing conflict. Dryden’s greatest achievements were in satiric verse: the mock-heroic Mac Flecknoe, a more personal product of his Laureate years, was a lampoon circulated in manuscript and an attack on the playwright Thomas Shadwell. Dryden’s main goal in the work is to “satirize Shadwell, ostensibly for his offenses against literature but more immediately we may suppose for his habitual badgering of him on the stage and in print.” It is not a belittling form of satire, but rather one which makes his object great in ways which are unexpected, transferring the ridiculous into poetry. This line of satire continued with Absalom and Achitophel (1681) and The Medal (1682). His other major works from this period are the religious poems Religio Laici (1682), written from the position of a member of the Church of England; his 1683 edition of Plutarch’s Lives Translated From the Greek by Several Hands in which he introduced the word biography to English readers; and The Hind and the Panther, (1687) which celebrates his conversion to Roman Catholicism. He wrote Britannia Rediviva celebrating the birth of a son and heir to the Catholic King and Queen on 10 June 1688. When later in the same year James II was deposed in the Glorious Revolution, Dryden’s refusal to take the oaths of allegiance to the new monarchs, William and Mary, left him out of favour at court. Thomas Shadwell succeeded him as Poet Laureate, and he was forced to give up his public offices and live by the proceeds of his pen. Dryden translated works by Horace, Juvenal, Ovid, Lucretius, and Theocritus, a task which he found far more satisfying than writing for the stage. In 1694 he began work on what would be his most ambitious and defining work as translator, The Works of Virgil (1697), which was published by subscription. The publication of the translation of Virgil was a national event and brought Dryden the sum of £1,400. His final translations appeared in the volume Fables Ancient and Modern (1700), a series of episodes from Homer, Ovid, and Boccaccio, as well as modernised adaptations from Geoffrey Chaucer interspersed with Dryden’s own poems. As a translator, he made great literary works in the older languages available to readers of English. Dryden died on 12 May 1700, and was initially buried in St. Anne’s cemetery in Soho, before being exhumed and reburied in Westminster Abbey ten days later. He was the subject of poetic eulogies, such as Luctus Brittannici: or the Tears of the British Muses; for the Death of John Dryden, Esq. (London, 1700), and The Nine Muses. A Royal Society of Arts blue plaque commemorates Dryden at 43 Gerrard Street in London’s Chinatown. He lived at 137 Long Acre from 1682 to 1686 and at 43 Gerrard Street from 1686 until his death. Reputation and influence Dryden was the dominant literary figure and influence of his age. He established the heroic couplet as a standard form of English poetry by writing successful satires, religious pieces, fables, epigrams, compliments, prologues, and plays with it; he also introduced the alexandrine and triplet into the form. In his poems, translations, and criticism, he established a poetic diction appropriate to the heroic couplet—Auden referred to him as “the master of the middle style”—that was a model for his contemporaries and for much of the 18th century. The considerable loss felt by the English literary community at his death was evident in the elegies written about him. Dryden’s heroic couplet became the dominant poetic form of the 18th century. Alexander Pope was heavily influenced by Dryden and often borrowed from him; other writers were equally influenced by Dryden and Pope. Pope famously praised Dryden’s versification in his imitation of Horace’s Epistle II.i: "Dryden taught to join / The varying pause, the full resounding line, / The long majestic march, and energy divine." Samuel Johnson summed up the general attitude with his remark that “the veneration with which his name is pronounced by every cultivator of English literature, is paid to him as he refined the language, improved the sentiments, and tuned the numbers of English poetry.” His poems were very widely read, and are often quoted, for instance, in Tom Jones and Johnson’s essays. Johnson also noted, however, that “He is, therefore, with all his variety of excellence, not often pathetic; and had so little sensibility of the power of effusions purely natural, that he did not esteem them in others. Simplicity gave him no pleasure.” Readers in the first half of the 18th century did not mind this too much, but later generations considered Dryden’s absence of sensibility a fault. One of the first attacks on Dryden’s reputation was by Wordsworth, who complained that Dryden’s descriptions of natural objects in his translations from Virgil were much inferior to the originals. However, several of Wordsworth’s contemporaries, such as George Crabbe, Lord Byron, and Walter Scott (who edited Dryden’s works), were still keen admirers of Dryden. Besides, Wordsworth did admire many of Dryden’s poems, and his famous “Intimations of Immortality” ode owes something stylistically to Dryden’s “Alexander’s Feast”. John Keats admired the “Fables”, and imitated them in his poem Lamia. Later 19th century writers had little use for verse satire, Pope, or Dryden; Matthew Arnold famously dismissed them as “classics of our prose.” He did have a committed admirer in George Saintsbury, and was a prominent figure in quotation books such as Bartlett’s, but the next major poet to take an interest in Dryden was T. S. Eliot, who wrote that he was 'the ancestor of nearly all that is best in the poetry of the eighteenth century’, and that ‘we cannot fully enjoy or rightly estimate a hundred years of English poetry unless we fully enjoy Dryden.’ However, in the same essay, Eliot accused Dryden of having a “commonplace mind.” Critical interest in Dryden has increased recently, but, as a relatively straightforward writer (William Empson, another modern admirer of Dryden, compared his “flat” use of language with Donne’s interest in the “echoes and recesses of words”) his work has not occasioned as much interest as Andrew Marvell’s or John Donne’s or Pope’s. Dryden is believed to be the first person to posit that English sentences should not end in prepositions because Latin sentences cannot end in prepositions. Dryden created the prescription against preposition stranding in 1672 when he objected to Ben Jonson’s 1611 phrase the bodies that those souls were frighted from, although he did not provide an explanation of the rationale that gave rise to his preference. The phrase “blaze of glory” is believed to have originated in Dryden’s 1686 poem The Hind and the Panther, referring to the throne of God as a “blaze of glory that forbids the sight.” Poetic style What Dryden achieved in his poetry was neither the emotional excitement of the early nineteenth-century romantics nor the intellectual complexities of the metaphysicals. His subject matter was often factual, and he aimed at expressing his thoughts in the most precise and concentrated manner. Although he uses formal structures such as heroic couplets, he tried to recreate the natural rhythm of speech, and he knew that different subjects need different kinds of verse. In his preface to Religio Laici he says that “the expressions of a poem designed purely for instruction ought to be plain and natural, yet majestic... The florid, elevated and figurative way is for the passions; for (these) are begotten in the soul by showing the objects out of their true proportion.... A man is to be cheated into passion, but to be reasoned into truth.” Translation style While Dryden had many admirers, he also had his share of critics, Mark Van Doren among them. Doren complained that in translating Vergil’s Aeneid, Dryden had added “a fund of phrases with which he could expand any passage that seemed to him curt”. Dryden did not feel such expansion was a fault, arguing that as Latin is a naturally concise language it cannot be duly represented by a comparable number of words in English. "He... recognized that Vergil 'had the advantage of a language wherein much may be comprehended in a little space’ (5:329–30). The 'way to please the best Judges... is not to Translate a Poet literally; and Virgil least of any other’ (5:329)" For example, take lines 789–795 of Book 2 when Aeneas sees and receives a message from the ghost of his wife, Creusa. iamque vale et nati serva communis amorem.' haec ubi dicta dedit, lacrimantem et multa volentem dicere deseruit, tenuisque recessit in auras. ter conatus ibi collo dare bracchia circum; ter frustra comprensa manus effugit imago, par levibus ventis volucrique simillima somno. sic demum socios consumpta nocte reviso Dryden translates it like this: I trust our common issue to your care.' She said, and gliding pass'd unseen in air. I strove to speak: but horror tied my tongue; And thrice about her neck my arms I flung, And, thrice deceiv'd, on vain embraces hung. Light as an empty dream at break of day, Or as a blast of wind, she rush'd away. Thus having pass'd the night in fruitless pain, I to my longing friends return again Dryden’s translation is based on presumed authorial intent and smooth English. In line 790 the literal translation of "haec ubi dicta dedit” is "when she gave these words.” But "she said” gets the point across, uses half the words, and makes for better English. A few lines later, with “ter conatus ibi collo dare bracchia circum; ter frustra comprensa manus effugit imago”, he alters the literal translation “Thrice trying to give arms around her neck; thrice the image grasped in vain fled the hands”, in order to fit it into meter and the emotion of the scene. In his own words, The way I have taken, is not so streight as Metaphrase, nor so loose as Paraphrase: Some things too I have omitted, and sometimes added of my own. Yet the omissions I hope, are but of Circumstances, and such as wou'd have no grace in English; and the Addition, I also hope, are easily deduc'd from Virgil's Sense. They will seem (at least I have the Vanity to think so), not struck into him, but growing out of him. (5:529) In a similar vein, Dryden writes in his Preface to the translation anthology Sylvae: Where I have taken away some of [the original authors’] Expressions, and cut them shorter, it may possibly be on this consideration, that what was beautiful in the Greek or Latin, would not appear so shining in the English; and where I have enlarg’d them, I desire the false Criticks would not always think that those thoughts are wholly mine, but that either they are secretly in the Poet, or may be fairly deduc’d from him; or at least, if both those considerations should fail, that my own is of a piece with his, and that if he were living, and an Englishman, they are such as he wou’d probably have written. Family On 1 December 1663 Dryden married Lady Elizabeth Howard (died 1714). The marriage was at St. Swithin’s, London, and the consent of the parents is noted on the license, though Lady Elizabeth was then about twenty-five. She was the object of some scandals, well or ill founded; it was said that Dryden had been bullied into the marriage by her brothers. A small estate in Wiltshire was settled upon them by her father. The lady’s intellect and temper were apparently not good; her husband was treated as an inferior by those of her social status. Both Dryden and his wife were warmly attached to their children. They had three sons: Charles (1666–1704), John (1668–1701), and Erasmus Henry (1669–1710). Lady Elizabeth Dryden survived her husband, but went insane soon after his death. Though some have historically claimed to be from the lineage of John Dryden, his three children had no children themselves. Selected works * Astraea Redux, 1660 * The Wild Gallant (comedy), 1663 * The Indian Emperour (tragedy), 1665 * Annus Mirabilis (poem), 1667 * The Tempest, or The Enchanted Island (comedy), 1667, an adaptation with William D’Avenant of Shakespeare’s The Tempest * Secret Love, or The Maiden Queen, 1667 * An Essay of Dramatick Poesie, 1668 * An Evening’s Love (comedy), 1668 * Tyrannick Love (tragedy), 1669 * The Conquest of Granada, 1670 * The Assignation, or Love in a Nunnery, 1672 * Marriage à la mode, 1672 * Amboyna, or the Cruelties of the Dutch to the English Merchants, 1673 * The Mistaken Husband (comedy), 1674 * Aureng-zebe, 1675 * All for Love, 1678 * Oedipus (heroic drama), 1679, an adaptation with Nathaniel Lee of Sophocles’ Oedipus * Absalom and Achitophel, 1681 * The Spanish Fryar, 1681 * Mac Flecknoe, 1682 * The Medal, 1682 * Religio Laici, 1682 * Threnodia Augustalis, 1685 * The Hind and the Panther, 1687 * A Song for St. Cecilia’s Day, 1687 * Britannia Rediviva, 1688, written to mark the birth of a Prince of Wales. * Epigram on Milton, 1688 * Amphitryon, 1690 * Don Sebastian (play), 1690 * Creator Spirit, by whose aid, 1690. Translation of Rabanus Maurus’ Veni Creator Spiritus * King Arthur, 1691 * Cleomenes, 1692 * Love Triumphant, 1694 * The Works of Virgil, 1697 * Alexander’s Feast, 1697 * Fables, Ancient and Modern, 1700 * The Art of Satire * To the Memory of Mr. Oldham, 1684 References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Dryden

John Drinkwater (1 June 1882 – 25 March 1937) was an English poet and dramatist. Drinkwater was born in Leytonstone, London, and worked as an insurance clerk. In the period immediately before the First World War he was one of the group of poets associated with the Gloucestershire village of Dymock, along with Rupert Brooke and others. In 1919 he had his first major success with his play Abraham Lincoln. He followed it with others in a similar vein, including Mary Stuart and Oliver Cromwell. In 1924, his Lincoln play was adapted for a two-reel short film made by Lee DeForest and J. Searle Dawley featuring Frank McGlynn Sr. as Lincoln, and made in DeForest's Phonofilm sound-on-film process. He had published poetry since The Death of Leander in 1906; the first volume of his Collected Poems was published in 1923. He also compiled anthologies and wrote literary criticism (e.g. Swinburne: an estimate (1913)), and later became manager of Birmingham Repertory Theatre. He was married to Daisy Kennedy, the ex-wife of Benno Moiseiwitsch. Papers relating to John Drinkwater and collected by his stepdaughter are held at the University of Birmingham Special Collections. John Drinkwater made recordings in Columbia Records' International Educational Society Lecture series. They include Lecture 10 – a lecture on The Speaking of Verse (Four 78rpm sides, Cat no. D 40018-40019), and Lecture 70 John Drinkwater reading his own poems (Four 78rpm sides, Cat no. D 40140-40141). Death and commemoration Drinkwater died in London in 1937. He is buried at Piddington, Oxfordshire, where he had spent summer holidays as a child. A road in Leytonstone, formerly a 1960s council estate, is named after Drinkwater, as is a small development of modern houses in Piddington. References Wikipedia – en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Drinkwater_(playwright)

I am a single father, I am a son and I am a brother but to all I am a friend. My life revolves around all that I love and all that I love means I will keep on breathing and trying. I am mid 40's with a long and fruitful life ahead dreaming of calm and serenity in all I do. I am not "that" outgoing but enjoy time away with family and friends. Life now has become a place where I can watch the fruits of our labor ripen. "As we age and as we live life becomes less of a riddle and more of a poem"

Lord Alfred Bruce Douglas (22 October 1870 – 20 March 1945), nicknamed Bosie, was a British author, poet and translator, better known as the intimate friend and lover of the writer Oscar Wilde. Much of his early poetry was Uranian in theme, though he tended, later in life, to distance himself from both Wilde's influence and his own role as a Uranian poet. Early life and background The third son of John Douglas, 9th Marquess of Queensberry and his first wife, Sibyl née Montgomery, Douglas was born at Ham Hill House in Worcestershire. He was his mother's favourite child; she called him Bosie (a derivative of Boysie), a nickname which stuck for the rest of his life. Douglas was educated at Winchester College (1884–88) and at Magdalen College, Oxford (1889–93), which he left without obtaining a degree. At Oxford, Douglas edited an undergraduate journal The Spirit Lamp (1892-3), an activity that intensified the constant conflict between him and his father. Their relationship had always been a strained one and during the Queensberry-Wilde feud, Douglas sided with Wilde, even encouraging him to prosecute his own father for libel. In 1893, Douglas had a brief affair with George Ives. In 1860, Douglas's grandfather, the 8th Marquess of Queensberry, had died in what was reported as a shooting accident, but his death was widely believed to have been suicide. In 1862, his widowed grandmother, Lady Queensberry, converted to Roman Catholicism and took her children to live in Paris. Apart from the violent death of his grandfather, there were other tragedies in Douglas's family. One of his uncles, Lord James Douglas, was deeply attached to his twin sister 'Florrie' and was heartbroken when she married. In 1885, he tried to abduct a young girl, and after that became ever more manic. In 1888, Lord James married, but this proved disastrous. Separated from Florrie, James drank himself into a deep depression, and in 1891 committed suicide by cutting his throat. Another of his uncles, Lord Francis Douglas (1847–1865) had died in a climbing accident on the Matterhorn, while his uncle Lord Archibald Edward Douglas (1850–1938) became a clergyman. (Alfred Douglas's only child was in turn to go mad, and died in a mental hospital.) Alfred Douglas's aunt, Lord James's twin Lady Florence Douglas (1855–1905), was an author, war correspondent for the Morning Post during the First Boer War, and a feminist. In 1890, she published a novel, Gloriana, or the Revolution of 1900, in which women's suffrage is achieved after a woman posing as a man named Hector l'Estrange is elected to the House of Commons. The character l'Estrange is clearly based on Oscar Wilde. Relationship with Wilde In 1891, Douglas met Oscar Wilde; although the playwright was married with two sons, they soon began an affair. In 1894, the Robert Hichens novel The Green Carnation was published. Said to be a roman a clef based on the relationship of Wilde and Douglas, it would be one of the texts used against Wilde during his trials in 1895. Douglas, known to his friends as 'Bosie', has been described as spoiled, reckless, insolent and extravagant. He would spend money on boys and gambling and expected Wilde to contribute to his tastes. They often argued and broke up, but would also always reconcile. Douglas had praised Wilde's play Salome in the Oxford magazine, The Spirit Lamp, of which he was editor (and used as a covert means of gaining acceptance for homosexuality). Wilde had originally written Salomé in French, and in 1893 he commissioned Douglas to translate it into English. Douglas's French was very poor and his translation was highly criticised: a passage that goes "On ne doit regarder que dans les miroirs" (French for "One should only look in mirrors") was translated as "One must not look at mirrors". Douglas's temper would not accept Wilde's criticism and he claimed that the errors were really in Wilde's original play. This led to a hiatus in the relationship and a row between the two men, with angry messages being exchanged and even the involvement of the publisher John Lane and the illustrator Aubrey Beardsley when they themselves objected to Douglas's work. Beardsley complained to Robbie Ross: "For one week the numbers of telegraph and messenger boys who came to the door was simply scandalous". Wilde redid much of the translation himself, but, in a gesture of reconciliation, suggested that Douglas be dedicated as the translator rather than them sharing their names on the title-page. Accepting this, Douglas, in his vanity, compared a dedication to sharing the title-page as "the difference between a tribute of admiration from an artist and a receipt from a tradesman." On another occasion, while staying together in Brighton, Douglas fell ill with influenza and was nursed back to health by Wilde, but failed to return the favour when Wilde fell ill as well. Instead Douglas moved to the Grand Hotel and, on Wilde's 40th birthday, sent him a letter saying that he had charged him the bill. Douglas also gave his old clothes to male prostitutes, but failed to remove incriminating letters exchanged between him and Wilde, which were then used for blackmail. Alfred's father, the Marquess of Queensberry, quickly suspected the liaison to be more than a friendship. He sent his son a letter, attacking him for leaving Oxford without a degree and failing to take up a proper career, such as a civil servant or lawyer. He threatened to "disown [Alfred] and stop all money supplies". Alfred responded with a telegram stating: "What a funny little man you are". Queensberry was infuriated by this attitude. In his next letter he threatened his son with a "thrashing" and accused him of being "crazy". He also threatened to "make a public scandal in a way you little dream of" if he continued his relationship with Wilde. Queensberry was well known for his temper and threatening to beat people with a horsewhip. Alfred sent his father a postcard stating "I detest you" and making it clear that he would take Wilde's side in a fight between him and the Marquess, "with a loaded revolver". In answer Queensberry wrote to Alfred (whom he addressed as "You miserable creature") that he had divorced Alfred's mother in order not to "run the risk of bringing more creatures into the world like yourself" and that, when Alfred was a baby, "I cried over you the bitterest tears a man ever shed, that I had brought such a creature into the world, and unwittingly committed such a crime... You must be demented". When Douglas' eldest brother, Lord Drumlanrig, heir to the marquessate of Queensberry, died in a suspicious hunting accident in October 1894, rumours circulated that Drumlanrig had been having a homosexual relationship with the Prime Minister, Lord Rosebery. The elder Queensberry thus embarked on a campaign to save his other son, and began a public persecution of Wilde. He and a minder confronted the playwright in his own home; later, Queensberry planned to throw rotten vegetables at Wilde during the premiere of The Importance of Being Earnest, but, forewarned of this, the playwright was able to deny him access to the theatre. Queensberry then publicly insulted Wilde by leaving, at the latter's club, a visiting card on which he had written: "For Oscar Wilde posing as a somdomite"–a misspelling of "sodomite." The wording is in dispute – the handwriting is unclear – although Hyde reports it as this. According to Merlin Holland, Wilde's grandson, it is more likely "Posing somdomite," while Queensberry himself claimed it to be "Posing as somdomite." Holland suggests that this wording ("posing [as] ...") would have been easier to defend in court. The 1895 trials In response to this card, and with Douglas's avid support, but against the advice of friends such as Robert Ross, Frank Harris, and George Bernard Shaw, Wilde had Queensberry arrested and charged with criminal libel in a private prosecution, as sodomy was then a crime. Several highly suggestive erotic letters that Wilde had written to Douglas were introduced into evidence; he claimed that they were works of art. Wilde was closely questioned about the homoerotic themes in The Picture of Dorian Gray and in The Chameleon, a single-issue magazine published by Douglas to which he had contributed a short article. Queensberry's lawyer portrayed Wilde as a vicious older man who habitually preyed upon naive young boys and seduced them into a life of homosexuality with extravagant gifts and promises of a glamorous lifestyle. Queensberry's attorney announced in court that he had located several male prostitutes who were to testify that they had had sex with Wilde. Wilde then dropped the libel charge, on his lawyers' advice, as a conviction was very unlikely if the libel were demonstrated in court to be true. Based on the evidence raised during the case, Wilde was arrested the next day and charged with committing sodomy and "gross indecency", a vague charge which covered all homosexual acts other than sodomy. Douglas's 1892 poem Two Loves, which was used against Wilde at the latter's trial, ends with the famous line that refers to homosexuality as the love that dare not speak its name. Wilde gave an eloquent but counterproductive explanation of the nature of this love on the witness stand. The trial resulted in a hung jury. In 1895, when during his trials Wilde was released on bail, Douglas's cousin Sholto Johnstone Douglas stood surety for £500 of the bail money. The prosecutor opted to retry the case. Wilde was convicted on 25 May 1895 and sentenced to two years' hard labour, first at Pentonville, then Wandsworth, then famously in Reading Gaol. Douglas was forced into exile in Europe. While in prison, Wilde wrote Douglas a very long and critical letter entitled De Profundis, describing exactly what he felt about him, which Wilde was not permitted to send, but which may or may not have been sent to Douglas after Wilde's release. Following Wilde's release (19 May 1897), the two reunited in August at Rouen, but stayed together only a few months owing to personal differences and the various pressures on them. Naples and Paris This meeting was disapproved of by the friends and families of both men. During the later part of 1897, Wilde and Douglas lived together near Naples, but for financial and other reasons, they separated. Wilde lived the remainder of his life primarily in Paris, and Douglas returned to England in late 1898. The period when the two men lived in Naples would later become quite controversial. Wilde claimed that Douglas had offered a home, but had no funds or ideas. When Douglas eventually did gain funds from his late father's estate, he refused to grant Wilde a permanent allowance, although he did give him occasional handouts. When Wilde died in 1900, he was relatively impoverished. Douglas served as chief mourner, although there reportedly was an altercation at the gravesite between him and Robert Ross. This struggle would preview the later litigations between the two former lovers of Oscar Wilde. Marriage After Wilde's death, Douglas established a close friendship with Olive Eleanor Custance, an heiress and poet. They married on 4 March 1902 and had one son, Raymond Wilfred Sholto Douglas (17 November 1902 - 10 October 1964) who was diagnosed with a schizo-affective disorder at the age of 24, and died unmarried, in a mental hospital. Repudiation of Wilde More than a decade after Wilde's death, with the release of suppressed portions of Wilde's De Profundis letter in 1912, Douglas turned against his former friend, whose homosexuality he grew to condemn. He was a defence witness in the libel case brought by Maud Allan against Noel Pemberton Billing in 1918. Billing had accused Allan, who was performing Wilde's play Salome, of being part of a homosexual conspiracy to undermine the war effort. Douglas also contributed to Billing's journal Vigilante as part of his campaign against Robert Ross. He had written a poem referring to Margot Asquith "bound with Lesbian fillets" while her husband Herbert, the Prime Minister, gave money to Ross. During the trial he described Wilde as "the greatest force for evil that has appeared in Europe during the last three hundred and fifty years". Douglas added that he intensely regretted having met Wilde, and having helped him with the translation of Salome which he described as "a most pernicious and abominable piece of work”. Libel actions Douglas started his "litigious and libellous career" by obtaining an apology and fifty guineas each from the Oxford and Cambridge university magazines The Isis and Cambridge for defamatory references to him in an article on Wilde. He was a plaintiff and defendant in several trials for civil or criminal libel. In 1913 he accused Arthur Ransome of libelling him in his book Oscar Wilde: A Critical Study. He saw this trial as a weapon against his enemy Ross, not understanding that Ross would not be called to give evidence. In a similar way he had not appreciated the fact that his father's character would not be an issue when he urged Wilde to sue back in 1895. The court found in Ransome's favour. Ransome did remove the offending passages from the 2nd edition of his book. In the most noted case, brought by Winston Churchill in 1923, Douglas was found guilty of libelling Churchill and was sentenced to six months in prison. Douglas had claimed that Churchill had been part of a Jewish conspiracy to kill Lord Kitchener, the British Secretary of State for War. Kitchener had died on 5 June 1916, while on a diplomatic mission to Russia: the ship in which he was travelling, the armoured cruiser HMS Hampshire, struck a German naval mine and sank west of the Orkney Islands. In spite of this libel claim, Douglas wrote a sonnet in praise of Churchill in 1941. In 1924, while in prison, Douglas, in an ironic echo of Wilde's composition of De Profundis (Latin for "From the Depths") during his incarceration, wrote his last major poetic work, In Excelsis (literally, "In the highest"), which contains 17 cantos. Since the prison authorities would not allow Douglas to take the manuscript with him when he was released, he had to rewrite the entire work from memory. Douglas maintained that his health never recovered from his harsh prison ordeal, which included sleeping on a plank bed without a mattress. Later life In 1911, Douglas embraced Roman Catholicism, as Oscar Wilde had also done earlier. Following his own incarceration in prison in 1924, Douglas's feelings toward Oscar Wilde began to soften considerably. He said in Oscar Wilde: A Summing Up that “Sometimes a sin is also a crime (for example, a murder or theft) but this is not the case with homosexuality, any more than with adultery”. Throughout the 1930s and until his death, Douglas maintained correspondences with many people, including Marie Stopes and George Bernard Shaw. Anthony Wynn wrote the play Bernard and Bosie: A Most Unlikely Friendship based on the letters between Shaw and Douglas. One of Douglas's final public appearances was his well-received lecture to the Royal Society of Literature on 2 September 1943, entitled The Principles of Poetry, which was published in an edition of 1, copies. He attacked the poetry of T. S. Eliot, and the talk was praised by Arthur Quiller-Couch and Augustus John. Douglas's only child, Raymond, was diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder in 1927 and entered St Andrew's Hospital, a mental institution. He was decertified and released after five years, but suffered a subsequent breakdown and returned to the hospital. When his mother, Olive Douglas, died of a cerebral hemorrhage at the age of 67, Raymond was able to attend her funeral and in June he was again decertified and released. However, his conduct rapidly deteriorated and he returned to St Andrew's in November where he stayed until his death on 10 October 1964. Death Douglas died of congestive heart failure at Lancing in West Sussex on 20 March 1945 at the age of 74. He was buried on 23 March at the Franciscan Monastery, Crawley, West Sussex, where he is interred alongside his mother, Sibyl, Marchioness of Queensberry, who died on 31 October 1935 at the age of 91. A single gravestone covers them both. The elderly Douglas, living in reduced circumstances in Hove in the 1940s, is mentioned in the Diaries of Chips Channon and the first autobiography of Sir Donald Sinden, both of whom attended his funeral. Writings Douglas published several volumes of poetry; two books about his relationship with Wilde, Oscar Wilde and Myself (1914; largely ghostwritten by T.W.H. Crosland, the assistant editor of The Academy and later repudiated by Douglas), Oscar Wilde: A Summing Up (1940); and a memoir, The Autobiography of Lord Alfred Douglas (1931). Douglas also was the editor of a literary journal, The Academy, from 1907 to 1910, and during this time he had an affair with artist Romaine Brooks, who was also bisexual (the main love of her life, Natalie Clifford Barney, also had an affair with Wilde's niece Dorothy). There are six biographies of Douglas. The earlier ones by Braybrooke and Freeman were not allowed to quote from Douglas’s copyright work, and De Profundis was unpublished. Later biographies were by Rupert Croft-Cooke, H. Montgomery Hyde (who also wrote about Oscar Wilde), Douglas Murray (who describes Braybrooke’s biography as "a rehash and exaggeration of Douglas’s book", i.e. his autobiography). The most recent is Alfred Douglas: A Poet's Life and His Finest Work by Caspar Wintermans, from Peter Owen Publishers in 2007. Poetry * Poems (1896) * Tails with a Twist 'by a Belgian Hare' (1898) * The City of the Soul (1899) * The Duke of Berwick (1899) * The Placid Pug (1906) * The Pongo Papers and the Duke of Berwick (1907) * Sonnets (1909) * The Collected Poems of Lord Alfred Douglas (1919) * In Excelsis (1924) * The Complete Poems of Lord Alfred Douglas (1928) * Sonnets (1935) * Lyrics (1935) * The Sonnets of Lord Alfred Douglas (1943) Non-fiction * Oscar Wilde and Myself (1914) (ghost-written by T. W. H. Crosland [17]) * Foreword to New Preface to the 'Life and Confessions of Oscar Wilde' by Frank Harris (1925) * Introduction to Songs of Cell by Horatio Bottomley (1928) * The Autobiography of Lord Alfred Douglas (1929; 2nd ed. 1931) * My Friendship with Oscar Wilde (1932; retitled American version of his memoir) * The True History of Shakespeare's Sonnets (1933) * Introduction to The Pantomime Man by Richard Middleton (1933) * Preface to Bernard Shaw, Frank Harris, and Oscar Wilde by Robert Harborough Sherard (1937) * Without Apology (1938) * Preface to Oscar Wilde: A Play by Leslie Stokes and Sewell Stokes (1938) * Introduction to Brighton Aquatints by John Piper (1939) * Ireland and the War Against Hitler (1940) * Oscar Wilde: A Summing Up (1940) * Introduction to Oscar Wilde and the Yellow Nineties by Frances Winwar (1941) * The Principles of Poetry (1943) * Preface to Wartime Harvest by Marie Carmichael Stopes (1944) Antisemitism In 1920 Alfred Douglas founded a fiercely antisemitic magazine Plain English in which he printed numerous anti-Jewish diatribes, made claims of "human sacrifice among the Jews", and publicly advocated The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. References Wikipedia - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lord_Alfred_Douglas

Ernest Christopher Dowson (2 August 1867– 23 February 1900) was an English poet, novelist, and short-story writer, often associated with the Decadent movement. He was born in Lee, London, in 1867. His great-uncle was Alfred Domett, a poet and politician who became Premier of New Zealand and had allegedly been the subject of Robert Browning’s poem “Waring.” Dowson attended The Queen’s College, Oxford, but left in March 1888 before obtaining a degree.

William Henry Davies or W. H. Davies (3 July 1871 – 26 September 1940) was a Welsh poet and writer. Davies spent a significant part of his life as a tramp or hobo, in the United Kingdom and United States, but became one of the most popular poets of his time. The principal themes in his work are observations about life's hardships, the ways in which the human condition is reflected in nature, his own tramping adventures and the various characters he met. Davies is usually considered one of the Georgian Poets, but much of his work is not typical in style or theme of the group. Early Life The son of an iron moulder, Davies was born at 6, Portland Street in the Pillgwenlly district of Newport, Monmouthshire, Wales, a busy port. He had an older brother, Francis Gomer Boase (who was considered "slow") and in 1874 his younger sister Matilda was born. In November 1874, when William was aged three, his father died. The following year his mother Mary Anne Davies remarried and became Mrs Joseph Hill. She agreed that care of the three children should pass to their paternal grandparents, Francis and Lydia Davies, who ran the nearby Church House Inn at 14, Portland Street. His grandfather Francis Boase Davies, originally from Cornwall, had been a sea captain. Davies was related to the famous British actor Sir Henry Irving (referred to as cousin Brodribb by the family); he later recalled that his grandmother referred to Irving as " the cousin who brought disgrace on us". Davies' grandmother was described, by a neighbour who remembered her, as wearing ".. pretty little caps, with bebe ribbon, tiny roses and puce trimmings". Writing in his Introduction to the 1943 Collected Poems of W. H. Davies, Osbert Sitwell recalled Davies telling him that, in addition to his grandparents and himself, his home consisted of "an imbecile brother, a sister ... a maidservant, a dog, a cat, a parrot, a dove and a canary bird." Sitwell also recounts that Davies' grandmother, a Baptist by denomination, was "of a more austere and religious turn of mind than her husband." In 1879 the family moved to Raglan Street, then later to Upper Lewis Street, from where William attended Temple School. In 1883 he moved to Alexandra Road School and the following year was arrested, as one of a gang of five schoolmates, and charged with stealing handbags. He was given twelve strokes of the birch. In 1885 Davies wrote his first poem entitled "Death". In his Poet's Pilgrimage (1918) Davies recounts the time when, at the age of 14, he was left with orders to sit with his dying grandfather. He missed the final moments of his grandfather's death as he was too engrossed in reading "a very interesting book of wild adventure". Delinquent to Supertramp Having finished school under the cloud of his theft he worked first for an ironmonger. In November 1886, his grandmother signed the papers for Davies to begin a five-year apprenticeship to a local picture-frame maker. Davies never enjoyed the craft, however, and never settled into any regular work. He was a difficult and somewhat delinquent young man, and made repeated requests to his grandmother to lend him the money to sail to America. When these were all refused, he eventually left Newport, took casual work and started to travel. The Autobiography of a Super-Tramp, published in 1908, covers his life in the USA between 1893 and 1899, including many adventures and characters from his travels as a drifter. During this period he crossed the Atlantic at least seven times, working on cattle ships. He travelled through many of the states, sometimes begging, sometimes taking seasonal work, but often ending up spending any savings on a drinking spree with a fellow traveller. He took advantage of the corrupt system of "boodle", in order to pass the winter in Michigan, by agreeing to be locked up in a series of different jails. Here, with his fellow tramps, Davies would enjoy the relative comfort of "card-playing, singing, smoking, reading, relating experiences and occasionally taking exercise or going out for a walk." At one stage, on his way to Memphis, Tennessee, he lay alone in a swamp for three days and nights suffering from malaria. The turning point in Davies' life came when, after a week of rambling in London, he spotted a newspaper story about the riches to be made in the Klondike and immediately set off to make his fortune in Canada. Attempting to jump a freight train at Renfrew, Ontario, on 20 March 1899, with fellow tramp Three-fingered Jack, he lost his footing and his right foot was crushed under the wheels of the train. The leg later had to be amputated below the knee and he wore a wooden leg thereafter. Davies' biographers have agreed that the significance of the accident should not be underestimated, even though Davies himself played down the story. Moult begins his biography with the incident and Stonesifer has suggested that this event, more than any other, led Davies to become a professional poet. Davies himself wrote of the accident: "I bore this accident with an outward fortitude that was far from the true state of my feelings. Thinking of my present helplessness caused me many a bitter moment, but I managed to impress all comers with a false indifference… I was soon home again, having been away less than four months; but all the wildness had been taken out of me, and my adventures after this were not of my own seeking, but the result of circumstances." Davies' view of his own disability was ambivalent. In his poem "The Fog", published in the 1913 Foliage, a blind man leads the poet through the fog, showing the reader that one who is handicapped in one domain may well have a considerable advantage in another. Poet He returned to Britain, living a rough life, particularly in London shelters and doss-houses, including the Salvation Army hostel in Southwark known as "The Ark" which he grew to despise. Fearing the contempt of his fellow tramps, he would often feign slumber in the corner of his doss-house, mentally composing his poems and only later committing them to paper in private. At one stage he borrowed money to have his poems printed on loose sheets of paper, which he then tried to sell door-to-door through the streets of residential London. When this enterprise failed, he returned to his lodgings and, in a fit of rage, burned all of the printed sheets in the fire. Davies self-published his first book of poetry, The Soul's Destroyer, in 1905, again by means of his own savings. It proved to be the beginning of success and a growing reputation. In order to even get the slim volume published, Davies had to forgo his allowance and live the life of a tramp for six months (with the first draft of the book hidden in his pocket), just to secure a loan of funds from his inheritance. When eventually published, the volume was largely ignored and he resorted to posting individual copies by hand to prospective wealthy customers chosen from the pages of Who's Who, asking them to send the price of the book, a half crown, in return. He eventually managed to sell 60 of the 200 copies printed. One of the copies was sent to Arthur Adcock, then a journalist with the Daily Mail. On reading the book, as he later wrote in his essay "Gods Of Modern Grub Street", Adcock said that he "recognised that there were crudities and even doggerel in it, there was also in it some of the freshest and most magical poetry to be found in modern books". He sent the price of the book and asked Davies to meet him. Adcock is still generally regarded as "the man who discovered Davies". The first trade edition of The Soul's Destroyer was published by Alston Rivers in 1907. A second edition followed in 1908 and a third in 1910. A 1906 edition, by Fifield, was advertised but has not been verified. Rural life in Kent On 12 October 1905 Davies met Edward Thomas, then literary critic for the Daily Chronicle in London, who was to do more to help him than anyone else. Thomas rented for Davies the tiny two-roomed "Stidulph's Cottage", in Egg Pie Lane, not far from his own home at Elses Farm near Sevenoaks in Kent. Davies moved to the cottage, from 6 Llanwern Street, Newport, via London, in the second week of February 1907. The cottage was "only two meadows off" from Thomas' own house. Thomas adopted the role of protective guardian for Davies, on one occasion even arranging for the manufacture, by a local wheelwright, of a makeshift replacement wooden leg, which was invoiced to Davies as "a novelty cricket bat". In 1907, the manuscript of The Autobiography of a Super-Tramp drew the attention of George Bernard Shaw, who agreed to write a preface (largely through the concerted efforts of his wife Charlotte). It was only because of Shaw that Davies' contract with the publishers was rewritten to allow the author to retain the serial rights, all rights after three years, royalties of fifteen per cent of selling price and a non-returnable advance of twenty five pounds. Davies was also to be given a say on the style of all illustrations, advertisement layouts and cover designs. The original publisher, Duckworth and Sons, refused to accept these demands and so the book was placed instead with London publisher Fifield. A number of anecdotes of Davies' time with the Thomas family in Kent are recounted in the brief account later published by Thomas' widow Helen. In 1911, Davies was awarded a Civil List Pension of £50, later increased to £100 and then again to £150. Davies started to spend more time in London and made many literary friends and acquaintances. Though averse to giving autographs himself, Davies began to make a collection of his own and was particularly keen to obtain that of D. H. Lawrence. Georgian poetry publisher Edward Marsh was able to secure an autograph and also invited Lawrence and wife-to-be Frieda to meet Davies on 28 July 1913. Lawrence was immediately captivated by Davies and later invited him to join them in Germany. Despite his early enthusiasm for Davies' work, however, Lawrence's opinion changed after reading Foliage and he commented after reading Nature Poems in Italy that the verses seemed "so thin, one can hardly feel them". By this time Davies had amassed a library of about fifty books in his cottage, mostly of 16th- and 17th-century poets, and including Shakespeare, Milton, Wordsworth, Byron, Burns, Shelley, Keats, Coleridge, Blake and Herrick. In December 1908 his essay "How It Feels To Be Out of Work", described by Stonesifer as "a rather pedestrian performance", appeared in the pages of The English Review. He continued to send other periodical articles out to editors, but without any success. Society life in London After lodging at a number of temporary addresses in Sevenoaks, Davies moved back to London early in 1914, settling eventually at 14 Great Russell Street in the Bloomsbury district, previously the residence of Charles Dickens. Here in a tiny two-room apartment, initially infested with mice and rats, and next door to rooms occupied by a noisy Belgian prostitute, he lived from early 1916 until 1921. It was during this time in London that Davies embarked on a series of public readings of his work, alongside such others as Hilaire Belloc and W. B. Yeats, impressing such fellow poets as Ezra Pound. He soon found that he was able to socialise with leading society figures of the day, including Lord Balfour and Lady Randolph Churchill. While in London Davies also became friendly with a number of artists, including Jacob Epstein, Harold and Laura Knight, Nina Hamnett, Augustus John, Harold Gilman, William Rothenstein, Walter Sickert, Sir William Nicholson and Osbert and Edith Sitwell. He enjoyed the society of literary men and their conversation, particularly in the rarefied atmosphere downstairs at the Café Royal. He would also meet regularly with W. H. Hudson, Edward Garrett and others at The Mont Blanc in Soho. In his poetry Davies drew extensively for material on his experiences with the seamier side of life, but also on his love of nature. By the time of his prominent place in the Edward Marsh Georgian Poetry series, he was an established figure. He is generally best known for the opening two lines of the poem "Leisure", first published in Songs Of Joy and Others in 1911: "What is this life if, full of care / We have no time to stand and stare..." In October 1917 his work was included in the anthology Welsh Poets: A Representative English selection from Contemporary Writers collated by A. G. Prys-Jones and published by Erskine Macdonald of London. In the last months of 1921, Davies moved to more comfortable quarters at 13 Avery Row, Brook Street, where he rented rooms from the Quaker poet Olaf Baker. He began to find prolonged work difficult, however, suffering from increased bouts of rheumatism and other ailments. Harlow (1993) lists a total of 14 BBC broadcasts of Davies reading his own work made between 1924 and 1940 (now held in the BBC broadcast archive) although none included his most famous work, "Leisure". Later Days, the 1925 sequel to The Autobiography of a Super-Tramp, describes the beginnings of Davies' career as a writer and his acquaintance with Belloc, Shaw and de la Mare, amongst many others. He became "the most painted literary man of his day", drawn and painted by Augustus John, Sir William Nicholson, Dame Laura Knight and Sir William Rothenstein. His head in bronze was the most successful of Epstein's smaller works. Honours, memorials and legacy In 1926 Davies was honoured with the degree of Doctor Litteris, honoris causa from the University of Wales. Davies returned to his native Newport in 1930, where a luncheon was held in his honour at the Westgate Hotel. His return, in September 1938, for the unveiling of the plaque in his honour, proved to be his last public appearance. A large collection of Davies manuscripts, including a copy of "Leisure", dated 8 May 1914, is held by the National Library of Wales. The collection includes a copy of "A Boy's Sorrow", an apparently unpublished poem of two eight-line stanzas relating to the death of a neighbour. Also included is a volume (c. 1916) containing autograph fair copies of 15 Davies poems, some of them apparently unpublished, submitted to James Guthrie (1874–1952) for publication by the Pear Tree Press as a collection entitled Quiet Streams, to which annotations have been added by Lord Kenyon. British writer Gerald Brenan (1894–1987) and his generation were influenced by Davies' Autobiography of a Super-Tramp. In 1951 Jonathan Cape published The Essential W. H. Davies, selected and with an introduction by Brian Waters, a young Gloucestershire poet and writer whose work Davies admired, who described him as "about the last of England's professional poets". The collection included The Autobiography of a Super-tramp, and extracts from Beggars, A Poet's Pilgrimage, Later Days, My Birds and My Garden, as well as over 100 poems arranged by publication period. Many of Davies' poems have been given a musical setting. "Money, O!" was set to music for piano, in G minor, by Michael Head - his 1929 Boosey & Hawkes collection also included settings for "The Likeness", "The Temper of a Maid", "Natures' Friend", "Robin Redbreast" and "A Great Time". There are also three songs by Sir Arthur Bliss - "Thunderstorms", "This Night", and "Leisure" - as well as "The Rain" for voice and piano, by Margaret Campbell Bruce, published in 1951 by J. Curwen and Sons. Experimental Irish folk group Dr Strangely Strange also sang and quoted from "Leisure" on their 1970 album Heavy Petting, with harmonium accompaniment. A musical adaptation of the same poem, with John Karvelas (vocals) and Nick Pitloglou (piano) and an animated film by Pipaluk Polanksi, may be found on YouTube. Also in 1970, Fleetwood Mac recorded "Dragonfly", a song with lyrics taken from Davies' 1927 poem, "The Dragonfly". The song was also recorded by English singer-songwriter and multi-instrumentalist Blake, for his 2011 album The First Snow. On 1 July 1971 a special First Day Cover, with a matching commemorative post-mark was issued by the UK Post Office to mark Davies' centenary. A controversial statue by Paul Bothwell-Kincaid, inspired by the poem "Leisure", was unveiled in Commercial Street, Newport in December 1990, to commemorate Davies' work, on the 50th anniversary of his death. The bronze head of Davies by Epstein, from January 1917, regarded by many as the most accurate artistic impression of Davies and a copy of which Davies owned himself, may be found at Newport Museum and Art Gallery (donated by Viscount Tredegar). In August 2010 the play Supertramp, Sickert and Jack the Ripper by Lewis Davies, concerning an imagined sitting by Davies for a portrait by Walter Sickert, premiered at the Edinburgh Festival. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/W._H._Davies