Info

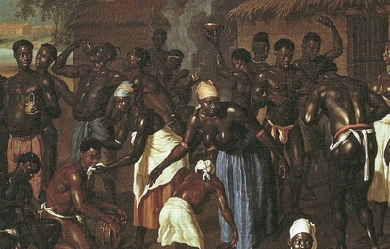

Exit of the bulls, rain

Eugenio Lucas Villaamil

1885

Museo Carmen Thyssen Málaga

Donald Hall (September 20, 1928 – June 23, 2018) was an American poet born in New Haven, Connecticut, in 1928. He began writing as an adolescent and attended the Bread Loaf Writers' Conference at the age of sixteen—the same year he had his first work published. He earned a B.A. from Harvard in 1951 and a B. Litt. from Oxford in 1953.

Gerard Manley Hopkins (28 July 1844 – 8 June 1889) was an English poet, Roman Catholic convert, and Jesuit priest, whose posthumous fame established him among the leading Victorian poets. His experimental explorations in prosody (especially sprung rhythm) and his use of imagery established him as a daring innovator in a period of largely traditional verse.

twenty-six year old poet from central scotland themes of: insomnia, solipsism, separation, confession, trippy-abstract, four a.m. word-spillage poetry & prose reader for the levatio published by honey & lime, the levatio, women in law @ the university of glasgow, vita brevis press, qmunicate ~ medium: @hollylm twitter: @hollylmckenna instagram: @beltanewean threads: @beltanewean bluesky: @hollylmckenna

Charles Harpur (23 January 1813– 10 June 1868) was an Australian poet. He was born on 23 January 1813 at Windsor, New South Wales, the third child of Joseph Harpur—originally from Kinsale, County Cork, Ireland, parish clerk and master of the Windsor district school—and Sarah, née Chidley (from Somerset; both had been transported.) Harpur received his elementary education in Windsor. This was probably largely supplemented by private study; he was an eager reader of William Shakespeare. Harpur followed various avocations in the bush and for some years in his twenties held a clerical position at the post office in Sydney.

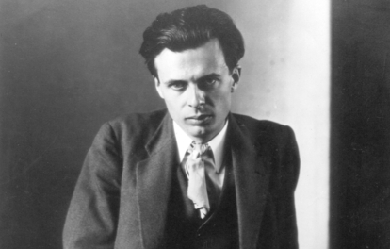

Aldous Leonard Huxley (26 July 1894 – 22 November 1963) was an English writer, philosopher and a prominent member of the Huxley family. He was best known for his novels including Brave New World, set in a dystopian London, and for non-fiction books, such as The Doors of Perception, which recalls experiences when taking a psychedelic drug, and a wide-ranging output of essays.

Thomas Hood (23 May 1799– 3 May 1845) was an English poet, author and humourist, best known for poems such as “The Bridge of Sighs” and “The Song of the Shirt”. Hood wrote regularly for The London Magazine, the Athenaeum, and Punch. He later published a magazine largely consisting of his own works. Hood, never robust, lapsed into invalidism by the age of 41 and died at the age of 45. William Michael Rossetti in 1903 called him “the finest English poet” between the generations of Shelley and Tennyson. Hood was the father of playwright and humourist Tom Hood (1835–1874).

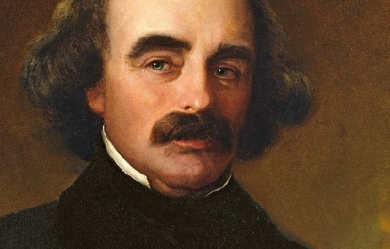

Nathaniel Hawthorne (July 4, 1804 – May 19, 1864) was an American novelist, dark romantic, and short story writer. He was born in 1804 in Salem, Massachusetts to Nathaniel Hathorne and the former Elizabeth Clarke Manning. His ancestors include John Hathorne, the only judge involved in the Salem witch trials who never repented of his actions. He entered Bowdoin College in 1821, was elected to Phi Beta Kappa in 1824, and graduated in 1825. He published his first work in 1828, the novel Fanshawe; he later tried to suppress it, feeling that it was not equal to the standard of his later work. He published several short stories in periodicals, which he collected in 1837 as Twice-Told Tales. The next year, he became engaged to Sophia Peabody. He worked at the Boston Custom House and joined Brook Farm, a transcendentalist community, before marrying Peabody in 1842. The couple moved to The Old Manse in Concord, Massachusetts, later moving to Salem, the Berkshires, then to The Wayside in Concord. The Scarlet Letter was published in 1850, followed by a succession of other novels. A political appointment as consul took Hawthorne and family to Europe before their return to Concord in 1860. Hawthorne died on May 19, 1864, and was survived by his wife and their three children. Much of Hawthorne’s writing centers on New England, many works featuring moral metaphors with an anti-Puritan inspiration. His fiction works are considered part of the Romantic movement and, more specifically, dark romanticism. His themes often center on the inherent evil and sin of humanity, and his works often have moral messages and deep psychological complexity. His published works include novels, short stories, and a biography of his college friend Franklin Pierce, the 14th President of the United States. Biography Early life Nathaniel Hawthorne was born on July 4, 1804, in Salem, Massachusetts; his birthplace is preserved and open to the public. William Hathorne was the author’s great-great-great-grandfather. He was a Puritan and was the first of the family to emigrate from England, settling in Dorchester, Massachusetts before moving to Salem. There he became an important member of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and held many political positions, including magistrate and judge, becoming infamous for his harsh sentencing. William’s son and the author’s great-great-grandfather John Hathorne was one of the judges who oversaw the Salem witch trials. Hawthorne probably added the “w” to his surname in his early twenties, shortly after graduating from college, in an effort to dissociate himself from his notorious forebears. Hawthorne’s father Nathaniel Hathorne, Sr. was a sea captain who died in 1808 of yellow fever in Suriname; he had been a member of the East India Marine Society. After his death, his widow moved with young Nathaniel and two daughters to live with relatives named the Mannings in Salem, where they lived for 10 years. Young Hawthorne was hit on the leg while playing “bat and ball” on November 10, 1813, and he became lame and bedridden for a year, though several physicians could find nothing wrong with him. In the summer of 1816, the family lived as boarders with farmers before moving to a home recently built specifically for them by Hawthorne’s uncles Richard and Robert Manning in Raymond, Maine, near Sebago Lake. Years later, Hawthorne looked back at his time in Maine fondly: “Those were delightful days, for that part of the country was wild then, with only scattered clearings, and nine tenths of it primeval woods.” In 1819, he was sent back to Salem for school and soon complained of homesickness and being too far from his mother and sisters. He distributed seven issues of The Spectator to his family in August and September 1820 for the sake of having fun. The homemade newspaper was written by hand and included essays, poems, and news featuring the young author’s adolescent humor. Hawthorne’s uncle Robert Manning insisted that the boy attend college, despite Hawthorne’s protests. With the financial support of his uncle, Hawthorne was sent to Bowdoin College in 1821, partly because of family connections in the area, and also because of its relatively inexpensive tuition rate. Hawthorne met future president Franklin Pierce on the way to Bowdoin, at the stage stop in Portland, and the two became fast friends. Once at the school, he also met future poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, future congressman Jonathan Cilley, and future naval reformer Horatio Bridge. He graduated with the class of 1825, and later described his college experience to Richard Henry Stoddard: I was educated (as the phrase is) at Bowdoin College. I was an idle student, negligent of college rules and the Procrustean details of academic life, rather choosing to nurse my own fancies than to dig into Greek roots and be numbered among the learned Thebans. Early career In 1836, Hawthorne served as the editor of the American Magazine of Useful and Entertaining Knowledge. At the time, he boarded with poet Thomas Green Fessenden on Hancock Street in Beacon Hill in Boston. He was offered an appointment as weigher and gauger at the Boston Custom House at a salary of $1,500 a year, which he accepted on January 17, 1839. During his time there, he rented a room from George Stillman Hillard, business partner of Charles Sumner. Hawthorne wrote in the comparative obscurity of what he called his “owl’s nest” in the family home. As he looked back on this period of his life, he wrote: “I have not lived, but only dreamed about living.” He contributed short stories to various magazines and annuals, including “Young Goodman Brown” and “The Minister’s Black Veil”, though none drew major attention to him. Horatio Bridge offered to cover the risk of collecting these stories in the spring of 1837 into the volume Twice-Told Tales, which made Hawthorne known locally. Marriage and family While at Bowdoin, Hawthorne wagered a bottle of Madeira wine with his friend Jonathan Cilley that Cilley would get married before Hawthorne did. By 1836, he had won the bet, but he did not remain a bachelor for life. He had public flirtations with Mary Silsbee and Elizabeth Peabody, then he began pursuing Peabody’s sister, illustrator and transcendentalist Sophia Peabody. He joined the transcendentalist Utopian community at Brook Farm in 1841, not because he agreed with the experiment but because it helped him save money to marry Sophia. He paid a $1,000 deposit and was put in charge of shoveling the hill of manure referred to as “the Gold Mine”. He left later that year, though his Brook Farm adventure became an inspiration for his novel The Blithedale Romance. Hawthorne married Sophia Peabody on July 9, 1842 at a ceremony in the Peabody parlor on West Street in Boston. The couple moved to The Old Manse in Concord, Massachusetts, where they lived for three years. His neighbor Ralph Waldo Emerson invited him into his social circle, but Hawthorne was almost pathologically shy and stayed silent at gatherings. At the Old Manse, Hawthorne wrote most of the tales collected in Mosses from an Old Manse. Like Hawthorne, Sophia was a reclusive person. Throughout her early life, she had frequent migraines and underwent several experimental medical treatments. She was mostly bedridden until her sister introduced her to Hawthorne, after which her headaches seem to have abated. The Hawthornes enjoyed a long and happy marriage. He referred to her as his “Dove” and wrote that she “is, in the strictest sense, my sole companion; and I need no other—there is no vacancy in my mind, any more than in my heart... Thank God that I suffice for her boundless heart!” Sophia greatly admired her husband’s work. She wrote in one of her journals: I am always so dazzled and bewildered with the richness, the depth, the... jewels of beauty in his productions that I am always looking forward to a second reading where I can ponder and muse and fully take in the miraculous wealth of thoughts. Poet Ellery Channing came to the Old Manse for help on the first anniversary of the Hawthornes’ marriage. A local teenager named Martha Hunt had drowned herself in the river and Hawthorne’s boat Pond Lily was needed to find her body. Hawthorne helped recover the corpse, which he described as “a spectacle of such perfect horror... She was the very image of death-agony”. The incident later inspired a scene in his novel The Blithedale Romance. The Hawthornes had three children. Their first was daughter Una, born March 3, 1844; her name was a reference to The Faerie Queene, to the displeasure of family members. Hawthorne wrote to a friend, “I find it a very sober and serious kind of happiness that springs from the birth of a child... There is no escaping it any longer. I have business on earth now, and must look about me for the means of doing it.” In October 1845, the Hawthornes moved to Salem. In 1846, their son Julian was born. Hawthorne wrote to his sister Louisa on June 22, 1846: “A small troglodyte made his appearance here at ten minutes to six o’clock this morning, who claimed to be your nephew.” Daughter Rose was born in May 1851, and Hawthorne called her his “autumnal flower”. Middle years In April 1846, Hawthorne was officially appointed as the “Surveyor for the District of Salem and Beverly and Inspector of the Revenue for the Port of Salem” at an annual salary of $1,200. He had difficulty writing during this period, as he admitted to Longfellow: I am trying to resume my pen... Whenever I sit alone, or walk alone, I find myself dreaming about stories, as of old; but these forenoons in the Custom House undo all that the afternoons and evenings have done. I should be happier if I could write. This employment, like his earlier appointment to the custom house in Boston, was vulnerable to the politics of the spoils system. Hawthorne was a Democrat and lost this job due to the change of administration in Washington after the presidential election of 1848. He wrote a letter of protest to the Boston Daily Advertiser which was attacked by the Whigs and supported by the Democrats, making Hawthorne’s dismissal a much-talked about event in New England. He was deeply affected by the death of his mother in late July, calling it “the darkest hour I ever lived”. He was appointed the corresponding secretary of the Salem Lyceum in 1848. Guests who came to speak that season included Emerson, Thoreau, Louis Agassiz, and Theodore Parker. Hawthorne returned to writing and published The Scarlet Letter in mid-March 1850, including a preface that refers to his three-year tenure in the Custom House and makes several allusions to local politicians—who did not appreciate their treatment. It was one of the first mass-produced books in America, selling 2,500 volumes within ten days and earning Hawthorne $1,500 over 14 years. The book was pirated by booksellers in London and became a best-seller in the United States; it initiated his most lucrative period as a writer. Hawthorne’s friend Edwin Percy Whipple objected to the novel’s “morbid intensity” and its dense psychological details, writing that the book “is therefore apt to become, like Hawthorne, too painfully anatomical in his exhibition of them”, though 20th-century writer D. H. Lawrence said that there could be no more perfect work of the American imagination than The Scarlet Letter. Hawthorne and his family moved to a small red farmhouse near Lenox, Massachusetts at the end of March 1850. He became friends with Herman Melville beginning on August 5, 1850 when the authors met at a picnic hosted by a mutual friend. Melville had just read Hawthorne’s short story collection Mosses from an Old Manse, and his unsigned review of the collection was printed in The Literary World on August 17 and August 24 entitled “Hawthorne and His Mosses”. Melville was composing Moby-Dick at the time, and he wrote that these stories revealed a dark side to Hawthorne, “shrouded in blackness, ten times black”. Melville dedicated Moby-Dick (1851) to Hawthorne: “In token of my admiration for his genius, this book is inscribed to Nathaniel Hawthorne.” Hawthorne’s time in the Berkshires was very productive. While there, he wrote The House of the Seven Gables (1851), which poet and critic James Russell Lowell said was better than The Scarlet Letter and called “the most valuable contribution to New England history that has been made.” He also wrote The Blithedale Romance (1852), his only work written in the first person. He also published A Wonder-Book for Girls and Boys in 1851, a collection of short stories retelling myths which he had been thinking about writing since 1846. Nevertheless, poet Ellery Channing reported that Hawthorne “has suffered much living in this place”. The family enjoyed the scenery of the Berkshires, although Hawthorne did not enjoy the winters in their small house. They left on November 21, 1851. Hawthorne noted, “I am sick to death of Berkshire... I have felt languid and dispirited, during almost my whole residence.” The Wayside and Europe In May 1852, the Hawthornes returned to Concord where they lived until July 1853. In February, they bought The Hillside, a home previously inhabited by Amos Bronson Alcott and his family, and renamed it The Wayside. Their neighbors in Concord included Emerson and Henry David Thoreau. That year, Hawthorne wrote The Life of Franklin Pierce, the campaign biography of his friend which depicted him as “a man of peaceful pursuits”. Horace Mann said, “If he makes out Pierce to be a great man or a brave man, it will be the greatest work of fiction he ever wrote.” In the biography, Hawthorne depicts Pierce as a statesman and soldier who had accomplished no great feats because of his need to make “little noise” and so “withdrew into the background”. He also left out Pierce’s drinking habits, despite rumors of his alcoholism, and emphasized Pierce’s belief that slavery could not “be remedied by human contrivances” but would, over time, “vanish like a dream”. With Pierce’s election as President, Hawthorne was rewarded in 1853 with the position of United States consul in Liverpool shortly after the publication of Tanglewood Tales. The role was considered the most lucrative foreign service position at the time, described by Hawthorne’s wife as “second in dignity to the Embassy in London”. His appointment ended in 1857 at the close of the Pierce administration, and the Hawthorne family toured France and Italy. During his time in Italy, the previously clean-shaven Hawthorne grew a bushy mustache. The family returned to The Wayside in 1860, and that year saw the publication of The Marble Faun, his first new book in seven years. Hawthorne admitted that he had aged considerably, referring to himself as “wrinkled with time and trouble”. Later years and death At the outset of the American Civil War, Hawthorne traveled with William D. Ticknor to Washington, D.C. where he met Abraham Lincoln and other notable figures. He wrote about his experiences in the essay “Chiefly About War Matters” in 1862. Failing health prevented him from completing several more romances. Hawthorne was suffering from pain in his stomach and insisted on a recuperative trip with his friend Franklin Pierce, though his neighbor Bronson Alcott was concerned that Hawthorne was too ill. While on a tour of the White Mountains, he died in his sleep on May 19, 1864 in Plymouth, New Hampshire. Pierce sent a telegram to Elizabeth Peabody asking her to inform Mrs. Hawthorne in person. Mrs. Hawthorne was too saddened by the news to handle the funeral arrangements herself. Hawthorne’s son Julian was a freshman at Harvard College, and he learned of his father’s death the next day; coincidentally, he was initiated into the Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity on the same day by being blindfolded and placed in a coffin. Longfellow wrote a tribute poem to Hawthorne published in 1866 called “The Bells of Lynn”. Hawthorne was buried on what is now known as “Authors’ Ridge” in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, Concord, Massachusetts. Pallbearers included Longfellow, Emerson, Alcott, Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr., James Thomas Fields, and Edwin Percy Whipple. Emerson wrote of the funeral: "I thought there was a tragic element in the event, that might be more fully rendered—in the painful solitude of the man, which, I suppose, could no longer be endured, & he died of it.” His wife Sophia and daughter Una were originally buried in England. However, in June 2006, they were reinterred in plots adjacent to Hawthorne. Writings Hawthorne had a particularly close relationship with his publishers William Ticknor and James Thomas Fields. Hawthorne once told Fields, “I care more for your good opinion than for that of a host of critics.” In fact, it was Fields who convinced Hawthorne to turn The Scarlet Letter into a novel rather than a short story. Ticknor handled many of Hawthorne’s personal matters, including the purchase of cigars, overseeing financial accounts, and even purchasing clothes. Ticknor died with Hawthorne at his side in Philadelphia in 1864; according to a friend, Hawthorne was left “apparently dazed”. Literary style and themes Hawthorne’s works belong to romanticism or, more specifically, dark romanticism, cautionary tales that suggest that guilt, sin, and evil are the most inherent natural qualities of humanity. Many of his works are inspired by Puritan New England, combining historical romance loaded with symbolism and deep psychological themes, bordering on surrealism. His depictions of the past are a version of historical fiction used only as a vehicle to express common themes of ancestral sin, guilt and retribution. His later writings also reflect his negative view of the Transcendentalism movement. Hawthorne was predominantly a short story writer in his early career. Upon publishing Twice-Told Tales, however, he noted, “I do not think much of them,” and he expected little response from the public. His four major romances were written between 1850 and 1860: The Scarlet Letter (1850), The House of the Seven Gables (1851), The Blithedale Romance (1852) and The Marble Faun (1860). Another novel-length romance, Fanshawe, was published anonymously in 1828. Hawthorne defined a romance as being radically different from a novel by not being concerned with the possible or probable course of ordinary experience. In the preface to The House of the Seven Gables, Hawthorne describes his romance-writing as using “atmospherical medium as to bring out or mellow the lights and deepen and enrich the shadows of the picture”. Critics have applied feminist perspectives and historicist approaches to Hawthorne’s depictions of women. Feminist scholars are interested particularly in Hester Prynne, who realized that she herself could not be the “destined prophetess,” but that “angel and apostle of the coming revelation” must be a woman." Camille Paglia saw Hester as mystical, “a wandering goddess still bearing the mark of her Asiatic origins... moving serenely in the magic circle of her sexual nature”. Lauren Berlant termed Hester "the citizen as woman [personifying] love as a quality of the body that contains the purest light of nature," her resulting “traitorous political theory” a “Female Symbolic” literalization of futile Puritan metaphors. Historicists view Hester as a protofeminist and avatar of the self-reliance and responsibility that led to women’s suffrage and reproductive emancipation. Anthony Splendora found her literary genealogy among other archetypally fallen but redeemed women, both historic and mythic. As examples, he offers Psyche of ancient legend; Heloise of twelfth-century France’s tragedy involving world-renowned philosopher Peter Abelard; Anne Hutchinson (America’s first heretic, circa 1636), and Hawthorne family friend Margaret Fuller. In Hester’s first appearance, Hawthorne likens her, “infant at her bosom”, to Mary, Mother of Jesus, “the image of Divine Maternity”. In her study of Victorian literature, in which such “galvanic outcasts” as Hester feature prominently, Nina Auerbach went so far as to name Hester’s fall and subsequent redemption, “the novel’s one unequivocally religious activity”. Regarding Hester as a deity figure, Meredith A. Powers found in Hester’s characterization “the earliest in American fiction that the archetypal Goddess appears quite graphically,” like a Goddess “not the wife of traditional marriage, permanently subject to a male overlord”; Powers noted “her syncretism, her flexibility, her inherent ability to alter and so avoid the defeat of secondary status in a goal-oriented civilization”. Aside from Hester Prynne, the model women of Hawthorne’s other novels—from Ellen Langton of Fanshawe to Zenobia and Priscilla of The Blithedale Romance, Hilda and Miriam of The Marble Faun and Phoebe and Hepzibah of The House of the Seven Gables—are more fully realized than his male characters, who merely orbit them. This observation is equally true of his short-stories, in which central females serve as allegorical figures: Rappaccini’s beautiful but life-altering, garden-bound, daughter; almost-perfect Georgiana of “The Birthmark”; the sinned-against (abandoned) Ester of “Ethan Brand”; and goodwife Faith Brown, linchpin of Young Goodman Brown’s very belief in God. “My Faith is gone!” Brown exclaims in despair upon seeing his wife at the Witches’ Sabbath.. Hawthorne also wrote nonfiction. In 2008, Library of America selected Hawthorne’s “A show of wax-figures” for inclusion in its two-century retrospective of American True Crime. Criticism Edgar Allan Poe wrote important, and somewhat unflattering, reviews of both Twice-Told Tales and Mosses from an Old Manse. Poe’s negative assessment was partly due to his own contempt of allegory and moral tales, and his chronic accusations of plagiarism, though he admitted, The style of Mr. Hawthorne is purity itself. His tone is singularly effective—wild, plaintive, thoughtful, and in full accordance with his themes... We look upon him as one of the few men of indisputable genius to whom our country has as yet given birth. Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote, “Nathaniel Hawthorne’s reputation as a writer is a very pleasing fact, because his writing is not good for anything, and this is a tribute to the man.” Henry James praised Hawthorne, saying, “The fine thing in Hawthorne is that he cared for the deeper psychology, and that, in his way, he tried to become familiar with it.” Poet John Greenleaf Whittier wrote that he admired the “weird and subtle beauty” in Hawthorne’s tales. Evert Augustus Duyckinck said of Hawthorne, “Of the American writers destined to live, he is the most original, the one least indebted to foreign models or literary precedents of any kind.” Contemporary response to Hawthorne’s work praised his sentimentality and moral purity while more modern evaluations focus on the dark psychological complexity. Beginning in the 1950s, critics have focused on symbolism and didacticism. The critic Harold Bloom has opined that only Henry James and William Faulkner challenge Hawthorne’s position as the greatest American novelist, although he admits that he favors James as the greatest American novelist. Bloom sees Hawthorne’s greatest works to be principally The Scarlet Letter, followed by The Marble Faun and certain short stories, including “My Kinsman, Major Molineux”, “Young Goodman Brown”, “Wakefield”, and “Feathertop”. Selected works * The “definitive edition” of Hawthorne’s works is The Centenary Edition of the Works of Nathaniel Hawthorne, edited by William Charvat and others, published by The Ohio State University Press in twenty-three volumes between 1962 and 1997. Tales and Sketches (1982) was the second volume to be published in the Library of America, Collected Novels (1983) the tenth. Novels * Fanshawe (published anonymously, 1828) * The New Adam and Eve (1843) * The Scarlet Letter (1850) * The House of the Seven Gables (1851) * The Blithedale Romance (1852) * The Marble Faun: Or, The Romance of Monte Beni (1860) (as Transformation: Or, The Romance of Monte Beni, UK publication, same year) * The Dolliver Romance (1863) (unfinished) * Septimius Felton; or, the Elixir of Life (unfinished, published in the Atlantic Monthly, 1872) * Doctor Grimshawe’s Secret: A Romance (unfinished, with preface and notes by Julian Hawthorne, 1882) Short story collections * Twice-Told Tales (1837) * Grandfather’s Chair (1840) * Mosses from an Old Manse (1846) * A Wonder-Book for Girls and Boys (1851) * The Snow-Image, and Other Twice-Told Tales (1852) * Tanglewood Tales (1853) * The Dolliver Romance and Other Pieces (1876) * The Great Stone Face and Other Tales of the White Mountains (1889) Selected short stories * “Roger Malvin’s Burial” (1832) * “My Kinsman, Major Molineux” (1832) * “The Minister’s Black Veil” (1832) * “Young Goodman Brown” (1835) * “The Gray Champion” (1835) * “The White Old Maid” (1835) * “Wakefield” (1835) * “The Ambitious Guest” (1835) * “The Man of Adamant” (1837) * “The May-Pole of Merry Mount” (1837) * “The Great Carbuncle” (1837) * “Dr. Heidegger’s Experiment” (1837) * “A Virtuoso’s Collection” (May 1842) * “The Birth-Mark” (March 1843) * “The Celestial Railroad” (1843) * “Egotism; or, The Bosom-Serpent” (1843) * “Rappaccini’s Daughter” (1844) * “P.'s Correspondence” (1845) * “The Artist of the Beautiful” (1846) * “Fire Worship” (1846) * “Ethan Brand” (1850) * “The Great Stone Face” (1850) * “Feathertop” (1852) Nonfiction * Twenty Days with Julian & Little Bunny (written 1851, published 1904) * Our Old Home (1863) * Passages from the French and Italian Notebooks (1871) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nathaniel_Hawthorne

Hedoné es el seudónimo de Héctor Navarro Francés, guitarrista, cantautor y poeta. Ha pertenecido a las bandas ERROR 404 (hasta 2016) y Miscelánea (2019). Es colaborador habitual del Festival Rasmia! En 2018 edita Hoy matamos a Poesía, una antología de los poemas publicados en el blog homónimo. Actualmente, se encuentra preparando su primer disco y en un proyecto conjunto con Jorge Melguizo.

Lesbia Harford (1891–1927) was an Australian poet, novelist and political activist. Life Lesbia Venner Keogh was the first child of Edmund Joseph Keogh and Beatrice Eleanor Moore, great-great-granddaughter of an Earl of Drogheda. Lesbia was born at Brighton, Victoria, on 9 April 1891. From 1893 to 1900, the family lived at “Wangrabel”, 6 Horsburgh Grove, Armadale (the house still stands today). Her father left home for Western Australia when his real estate business failed about 1900. She and her three siblings were raised by their mother, who took genteel jobs, begged handouts from Keogh relations and took in boarders. Lesbia was educated at the Sacré Cœur School at “Clifton”, Malvern, Victoria; Mary’s Mount school at Ballarat, Victoria; and the University of Melbourne, where she graduated LL.B. in 1916. She was one of the university’s few women students and one of its few opponents of Australia’s part in the First World War. Her brother, Esmond Venner (Bill) Keogh (1895–1970), became a prominent medical administrator and cancer researcher. Lesbia advocated free love in human relations. She herself formed lifelong parallel attachments to both men and women, most notably to Katie Lush, philosophy tutor at Ormond College. Becoming interested in social questions, she worked in textile and clothing factories to gain first hand knowledge of the conditions under which women worked. She became state vice-president of the Federated Clothing and Allied Trades Union. She campaigned strongly against conscription in World War I. She was a friend of Norman Jeffrey and lover of Guido Baracchi, founding members of the Communist Party of Australia (but which she never joined). In Sydney Lesbia sang her poems to Guido as they crossed the harbour on the Manly ferry. In 1918 she moved to Sydney to campaign for the release of the Sydney Twelve, members of the Industrial Workers of the World (the Wobblies) arrested and charged with treason, arson, sedition and forgery. She worked in clothing factories and as a university coach. She was also for a time a Fairfax housemaid (glimpsed in the poem “Miss Mary Fairfax”). She married Patrick John (Pat) Harford, sometime soldier, clicker in his uncle’s Fitzroy boot factory and a fellow Wobbly, in 1920. They shared an interest in painting and aesthetics. He was feckless and alcoholic but Pat wasn’t Pat last night at all. He was the rain,— The Spring,— Young Dionysus, white and warm,— Lilac and everything. They returned to her mother’s boarding house in Elsternwick, Melbourne in the early Twenties. Pat worked for the post-impressionist painter William Frater and himself became a painter under Frater’s influence, later moving towards modernism and cubism. The Harfords had no children and were estranged in the last years of Lesbia’s life. Some writers claim they were divorced but there is no documentary evidence of it. In 1926 Lesbia completed her articles with a Melbourne law firm. Authors agree on her always-delicate health but not on the cause: a severe attack of rheumatic fever while a young child (Serle); tuberculosis (Lamb); born with a heart problem that prevented her blood oxygenating (Sparrow). She often had to walk slowly. Her lips were sometimes quite blue. She died aged 36 of lung and heart failure in St Vincent’s Hospital on 5 July 1927. Writing Harford had begun writing verse in 1910, and in May 1921 Birth, a small poetry magazine published at Melbourne, gave the whole of one number to a selection from her poems. Harford’s 59-page The Law Relating to Hire Purchase in Australia and New Zealand, “just written for the money it will bring”, was published in 1923. In 1927 three of her poems were included in Serle’s An Australasian Anthology. The critic H.M. Green wrote “She has written some of the best lyrics among today’s and certainly, I would say, the best love lyrics written out here.” Mrs Keogh thought Lesbia’s writing was “beautiful” and in 1939 was still trying to get her novel and more poems published. In 1941 a small volume (54 poems) of The Poems of Lesbia Harford, edited by Nettie Palmer for Melbourne University Press, “revealed a poet of originality and charm.” In 1985 a much larger selection of poems appeared, edited by Marjorie Pizer and Drusilla Modjeska with a long introduction by Modjeska, acknowledging that some of Harford’s sexual relations were with women and much of her love poetry was addressed to them. Les Murray published 86 of these poems and a page of biography in a 2005 anthology. Lehmann and Gray’s obese 2011 Australian poetry since 1788 prints only thirteen poems (given “as much space as Brennan”) but provides a scholarly and detailed critical biography. The biggest selection in print is Collected Poems, which has 250 poems, a two-page foreword by Les Murray and an eight-page introduction by the editor, Oliver Dennis. Harford wrote a long-lost 190-page novel, The Invaluable Mystery, eventually published in 1987 with a foreword by Helen Garner and an introduction by Richard Nile and Robert Darby. Papers For decades it was thought that “On her death her father took custody of her notebooks and they were lost when his shack was destroyed by fire” but this is now known to be false. All known Harford poems are in the exercise books in Folders 1–3 of the Marjorie Pizer Papers, Mitchell Library, NSW, MLMSS 7428. Another ten folders collect manuscripts, typescript, letters and photos relating mainly to publication of her work. The typescript of The Invaluable Mystery is in the National Archive of Australia, Canberra, Series A699, control 1958/3640, barcode 278433. Legacy The political rock band Redgum recorded part of Harford’s poem “Periodicity” set to music as “Women in Change” on their 1980 album Virgin Ground. In Melbourne, the Victorian Women Lawyers’ biennial Lesbia Harford Oration, given by an eminent speaker on an issue of importance for women, is named in her honour. In 1991, the Playbox Theatre Company Melbourne presented Earthly Paradise; a Picture of Lesbia Harford, by the playwright Darryl Emmerson. This play was also published by Currency Press, Sydney.

.jpg)

Raid Jabbar HABIB, né en 1973 à Bagdad (Iraq), est un écrivain, poète et dramaturge irakien. Il est professeur de la littérature française à l'Université Al-Mustansiriyah de Bagdad. Œuvres publiées: 1. IZRAM, pièce de théâtre, publiée en 2010, France. 2. Les Conceptions de L’Aventure dans l’œuvre romanesque de Diderot, 2013. Allemagne. 3. Le Jansénisme et La Passion dans Les dernières tragédies de Racine, 2014. Allemagne. 4. Aux Côtés du Théâtre, du Roman et de la Poésie. 2017. France 5- Quelque Part Ailleurs, pièce de théâtre publiée en Arabe, Bagdad- Iraq, 2019 6- La Symphonie de l'Automne, recueil de poésie arabe, Bagdad, Iraq, 2020 7- Gouache et Hallucination, recueil de poésie en français, Paris, France, 2020 Email: [email protected]

George Moses Horton (1798–1884) was an African-American poet and the first African American poet to be published in the Southern United States. His book was published in 1828 while he was still enslaved; he remained enslaved until he was emancipated late in the Civil War. Biography Horton was born into slavery on William Horton’s plantation in Northampton County, North Carolina. He was the sixth of ten children, though the names of his parents are lost to history. As a very young child in 1800, he and several family members were moved to a tobacco farm in rural Chatham County, when his owner relocated. He was given as property to William’s relative James Horton in 1814. In 1819, the estate was broken up, and George Moses Horton’s family was separated (the poem “Division of an Estate” reflected on the experience years later). Horton disliked farm work and in his free time he taught himself to read using spelling books, the Bible, and hymnals. Learning poetry and snippets of literature, Horton composed poems in his mind. As a young adult, Horton delivered produce to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where he composed and recited poems for students, some of whom transcribed his compositions. Horton also composed poems, usually love poems, by commission for the students at 25 or 50 cents each. Considering the difficulty of earning income from poetry, Horton was likely one of the few professional poets in the South at the time. In 1829, his poems were published in a collection titled The Hope of Liberty, which was intended to raise funds for his release from slavery. The book, funded by the politically-liberal journalist Joseph Gales, appeared the same year as David Walker’s An Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World. Horton is believed to be the first Southern black to publish poetry. Though he knew how to read, he published the book before he learned how to write. As he recalled, “I fell to work in my head, and composed several undigested pieces.” By 1832, he had learned to write for himself, having learned with the aid of Caroline Lee Hentz, who was the wife of a professor and a writer herself. She also assisted in publishing at least two of his poems in a newspaper. Horton had composed a poem on the death of Hentz’s child. As he recalled: “She was extremely pleased with the dirge which I wrote on the death of her much lamented primogenial infant, and for which she gave me much credit and a handsome reward. Not being able to write myself, I dictated while she wrote.” She sent one of Horton’s poems to her hometown newspaper in Lancaster, Massachusetts, where it was published on April 8, 1828, as “Liberty and Slavery”. Horton’s first book was republished under the title Poems by a Slave in 1837 and compiled with a biography and poetry by Phillis Wheatley a year later in a book called Memoir and Poems of Phillis Wheatley, a Native African and Slave: Also Poems by a Slave. The book was published by Boston-based publisher and abolitionist Isaac Knapp, and it is believed to be the first complete collection of Wheatley’s poems in book form. In 1845, Horton released another book of poetry, The Poetical Works of George M. Horton, The Colored Bard of North-Carolina, To Which Is Prefixed The Life of the Author, Written by Himself. The moniker, “Colored Bard of North-Carolina”, was coined by his new publisher. Horton gained the admiration of North Carolina Governor John Owen, influential newspapermen Horace Greeley and William Lloyd Garrison, along with numerous Northern abolitionists. Sometime in the 1830s, Horton married an enslaved woman owned by Franklin Snipes in Chatham County. The couple had two children, Free and Rhody, though little else is known about the family. Horton had written about his interest in the new nation of Liberia, and a few of the abolitionist papers made calls to raise enough money so that Horton could see his dream of life in Liberia come true. He was not emancipated until 1865, however, when he met the Ninth Cavalry from Michigan. A young officer with that group, William H. S. Banks, collaborated with Horton on the collection Naked Genius the same year. At the age of 68, Horton moved to Pennsylvania as a freeman where he continued to write poetry for local newspapers. One such publication, “Forbidden to Ride on the Street Cars”, shows his disappointment in the unjust treatment of blacks even after emancipation. In Philadelphia, he wrote Sunday school stories on behalf of friends who lived in the city. His exact death location and date are unknown. At least one researcher suggests Horton moved to Liberia at some point. Poetry After Horton’s first poem was published in the Lancaster, Massachusetts Gazette, his works appeared in other newspapers like the Register in Raleigh, North Carolina, and the Freedom’s Journal in New York City. Horton’s poetic style was typical of contemporary European poetry and was similar to poems written by free white contemporaries, likely a reflection of his reading and his work for commission. He wrote both sonnets and ballads, and his earlier works focused on his life in servitude. Such topics, however, were more generalized and not necessarily based on his personal experience. Nevertheless, he referred to his life on “vile accursed earth” and the “drudg’ry, pain, and toil” of life, as well as his oppression “because my skin is black”. His first collection was focused heavily on the issue of slavery and bondage. Likely because sales from that book were not enough for him to purchase his freedom, his second book mentions slavery only twice. The change in theme is also likely due to the more restrictive climate in the South in the years leading up to the Civil War. His later works, especially those made after his emancipation, were more rural and pastoral. Like other early black American writers like Jupiter Hammon and Phillis Wheatley, Horton was also heavily influenced by the Bible. The earliest known critical commentary on Horton’s writing is from 1909 by UNC professor Collier Cobb, who dismissed Horton’s antislavery themes: “George never really cared for more liberty than he had, but was fond of playing to the grandstand.”. Legacy Winston-Salem, North Carolina opened the George Moses Horton Branch Library in 1927 in a YWCA building. The George Moses Horton Society for the Study of African American Poetry was founded in 1996, the same year he was inducted into the North Carolina Literary Hall of Fame. The next year, 1997, he was named Historic Poet Laureate of Chatham County, North Carolina. In 2006, UNC Chapel Hill named a dormitory for George Moses Horton; it was formerly called Hinton James North and is believed to be the first university dormitory in the country to be named for a slave. In 2015 author/illustrator Don Tate published Poet: The Remarkable Story of George Moses Horton, an illustrated biography of Horton for children. The Wilson Library at UNC hosted the national launch of the book on September 3, 2015. Published works The Hope of Liberty (1829) Poems by a Slave (1837) The Poetical Works of George M. Horton (1845) Naked Genius (1865, with William H. S. Banks) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Moses_Horton

José Hernández (Perdriel, San Martín, 1834 - Buenos Aires, 1886) Poeta argentino, autor de Martín Fierro, obra que se considera la cumbre de la literatura gauchesca y un destacado clásico de la literatura argentina. De pequeño estuvo al cuidado de tíos y abuelos mientras sus padres trabajaban en el campo. Estudió en el Liceo Argentino de San Telmo, pero una enfermedad del pecho le hizo abandonar Buenos Aires y reunirse con su padre en un campo de Camarones; para entonces la madre había muerto. Allí el joven Hernández permaneció unos años, impregnándose del mundo rural. Regresó a Buenos Aires, tras la batalla de Caseros (1852), y se vio involucrado en las luchas políticas que dividieron al país después de la caída de Juan Manuel de Rosas. De convicciones federales, se unió al gobierno de la Confederación, enfrentado con Buenos Aires. Para 1856 algunas fuentes lo sitúan en Paraná; otras atrasan esa residencia hasta 1858, pero lo cierto es que Hernández trabajó en dicha ciudad como empleado de comercio y que participó activamente en la batalla de Cepeda (1859) junto a Justo José de Urquiza. Después se retiró del ejército, obtuvo el cargo de oficial de contaduría y pasó a desempeñarse como taquígrafo del Senado. Volvió a luchar con las tropas confederadas que sufrieron la derrota de Pavón (1861). Se dedicó entonces al periodismo colaborando en El Argentino, escribió en el Eco de Corrientes y fundó más tarde, en Buenos Aires, El Río de la Plata, diario de vida efímera donde denunciaba la situación de los habitantes de la campaña. El 8 de junio de 1863 se casó con Carolina del Solar; ese mismo año fue asesinado el caudillo riojano que le inspiró la serie de artículos recopilados con el título de Vida del Chacho. Rasgos biográficos del general Angel Vicente Peñaloza. En ese texto, primer enfrentamiento con Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, muestra su calidad como cronista y su notable capacidad para la polémica. La suerte de Hernández siguió los cauces de los avatares políticos. Obligado al exilio, en el sur de Brasil escribió los primeros versos de El gaucho Martín Fierro (1872), que completó y publicó a su regreso a Buenos Aires. Después de un nuevo exilio en Uruguay, retornó definitivamente a Argentina en 1875 y resultó elegido diputado por la capital en 1879, año en que publicó La vuelta de Martín Fierro. En 1882 dio a conocer Instrucción del estanciero. Tratado completo para la plantación y manejo de campo destinado a la cría de hacienda vacuna, lanar y caballar, libro que, pese a lo específico del título, tiene un marcado cariz político. Murió en su quinta del barrio de Belgrano, el 21 de octubre de 1886. Martín Fierro No hay duda que la vida de Hernández tuvo un papel fundamental en la configuración de su obra maestra. Criado en el campo, con los gauchos, en plena lucha con la tierra y con los peligros que significaban los indios y los maleantes, su formación cultural fue autodidacta. Pero eso mismo dio carácter al hombre y a su vida, y cuando la Argentina formada en la colonia gana con su esfuerzo y su sangre la independencia, y en la nueva organización el gaucho queda en condiciones de inferioridad, llamado a desaparecer ante el empuje del criollismo más civilizado, el poeta empuña su lira en defensa de su pueblo, con el que se identifica, aunque él es criollo, y compone en las estrofas de las dos partes de su Martín Fierro el poema nacional argentino, la gesta de un país que se desarrolla y transforma, y de una raza que declina y va camino de su extinción: tal es el alcance significativo de esta dramática historia de un gaucho despojado y perseguido por la arbitrariedad del poder político y jurídico de las ciudades. Cuando Hernández escribió el Martín Fierro, la poesía gauchesca ya estaba consolidada como género literario. La definían un conjunto de fórmulas, tópicos y temas: el predominio de la forma del "diálogo", que reunía en sí una buena cantidad de rasgos gauchescos, tales como el ritual del encuentro, las fórmulas de salutación, las alusiones a los aparejos del caballo, el ofrecimiento de mate, tabaco y bebida o las quejas sobre la situación política o la personal. Estas quejas, a su vez, servían como punto de partida del relato desarrollado por cada uno de los personajes, construido siempre sobre motivos políticos, o bien sobre asuntos personales que tenían como trasfondo una determinada circunstancia política. Ésta es otra de las señales que contribuyen a definir lo gauchesco, ya que la elección de los personajes, los temas y el lenguaje rústico estuvo casi siempre ligada a opciones que desbordaban lo literario y remitían a lo político. Todas estas características aparecen ya en los "Diálogos patrióticos" de Hidalgo, en la poesía antirrosista primero y antiurquicista después de Hilario Ascasubi y (desprovisto de todo alcance político o militante, pero como una brillante síntesis formal de sus predecesores) en el Fausto de Estanislao del Campo. Pero el Martín Fierro, evidente beneficiario de la tradición de la poesía gauchesca, rompe sin embargo los moldes del género. El tradicional encuentro y el subsiguiente diálogo son reemplazados por un monólogo que modifica de manera radical las figuras del emisor y receptor del poema, y que reproduce la situación del antiguo gaucho cantor que, ante un auditorio de oyentes analfabetos, cuenta acompañándose con su guitarra las desgracias propias o ajenas. El protagonista empieza por presentarse y narrar sus relaciones con el medio, su familia y las tareas que realiza. Tal armonía se ve quebrada cuando llega la leva forzosa y lo obligan a marchar a la frontera con el indio. Ello significa la disolución de la familia, el desarraigo y muchos pesares. La amistad con el gaucho Cruz atenúa en parte los amargos sentimientos que causan en Fierro las injusticias y las violencias de que es testigo o ha protagonizado. En la segunda parte se produce el reencuentro con sus hijos, víctimas de abusos, como él, a quienes aconseja llevar una vida honrada y de trabajo. Hay también en la obra pequeñas rupturas formales. Mientras la primera parte puede leerse como un alegato contra los abusos de la presidencia de Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, en la segunda, realizada siete años más tarde, la dureza se rebaja y deja lugar a un cuadro más matizado y complejo del mundo rural. El poema, como casi toda la literatura gauchesca, está escrito en octosílabos (7210 versos), pero no agrupado en las tradicionales décimas o en cuartetas, sino en sextinas, estrofas de seis versos que posibilitan, a su vez, la división en pares, dándoles así una mayor proximidad con el lenguaje gauchesco. El gaucho Martín Fierro tuvo un gran éxito editorial en su día, pero ninguna repercusión entre la crítica literaria, por otra parte casi inexistente entonces. Los ardores nacionalistas que se vivieron con la celebración del primer centenario de la Revolución de Mayo se reflejaron, entre otras formas, en la revalorización de la obra por parte de Leopoldo Lugones y Ricardo Rojas. Desde esa fecha se convirtió en un clásico, y Jorge Luis Borges y Martínez Estrada, entre otros, le dedicaron su atención. Hoy El gaucho Martín Fierro y La vuelta de Martín Fierro se conocen como las dos partes de una misma obra, Martín Fierro, el punto más alto de la poesía gauchesca y una de las obras fundamentales de la literatura argentina. References http://www.biografiasyvidas.com/biografia/h/hernandez_jose.htm

(...) La breve pero intensa obra de José Luis Hidalgo ha merecido hasta la fecha valoraciones sumamente favorables por parte de la crítica especializada siendo de lamentar que una trayectoria tan interesante como la suya quedara truncada prematuramente por la muerte 2. De su interés e importancia dan testimonio hoy día no sólo los tres volúmenes poéticos que en vida tuvo ocasión de ordenar y de dar a la imprenta), sino los numerosos poemas que quedaron dispersos o inéditos a su fallecimiento y que M.a de Gracia lfach (Josefina Escolano) ordenó y publicó póstumamente por encargo de la Institución Cultural de Cantabria (...) José Luis Hidalgo (Torres, Cantabria, 10 de octubre de 1919 – Madrid, 3 de febrero de 1947) fue un poeta y pintor español. Su madre murió cuando él tenía nueve años. Terminada la Guerra Civil Española residió en Valencia, donde cursó los estudios de Bellas Artes. En Santander se relacionó con el grupo de la revista Proel, en la que publicó varios poemas. También colaboró en diversas revistas de ámbito nacional con sus poemas y trabajos de crítica artística. Enfermo de tuberculosis, murió en el sanatorio de Charmartín de la Rosa, en Madrid. Buena parte de su obra se publicó de forma póstuma. Obras * Raíz. Valencia, 1944 * Los animales * Los muertos * Canciones para niños, publicado en 1951 * Obra poética completa. Institución Cultural de Cantabria, 1976 (Por Francisco Ruiz Soriano) José Luis Hidalgo (Torres, Santander, 1919-Madrid, 1947) es uno de los poetas más representativos de la línea existencial de la primera promoción de posguerra, y precursor de la «Quinta del 42» santanderina que fundó la revista Proel (1944-1945; 1946-1949), donde destacarían escritores como José Hierro, Julio Maruri o Carlos Salomón. El rasgo definidor que subyace en la mayoría de sus composiciones es la indagación metafísica en torno a la Muerte, el Tiempo, el ser humano y Dios, temas esencialmente recurrentes en toda poesía meditativa, cuyos máximos exponentes habían sido Miguel de Unamuno y Antonio Machado. José Luis perdió a su madre tempranamente; esta circunstancia le marcó profundamente y está presente en algunas de sus poesías iniciales. En 1929 se trasladó a vivir a casa de su tío, don Casimiro Iglesias; allí transcurrieron su infancia y juventud. En 1934, a los quince años, empezó a publicar sus primeras composiciones, principalmente cuentos y greguerías, en El Impulsor de Torrelavega. Su interés por la literatura y el arte modernos le estimuló en su formación como incipiente pintor y escritor, y llegó a participar como conferenciante sobre poesía de vanguardia en la Biblioteca Popular de su ciudad, y como cartelista en la Olimpiada Popular de Barcelona (julio de 1936), ciudad donde le sorprendió la guerra. En agosto de ese año, visitó a Gutiérrez Solana, por quien sentía una gran admiración. Trabajó en la docencia en una escuela de Santander, y más tarde en Torrelavega. Ese mismo año conoció a José Hierro, con quien entabló una amistad que nunca se quebraría. Juntos visitaron a escritores como Gerardo Diego y Manuel Llano. En 1937 escribió Canciones para niños. En 1938 fue obligado a cumplir el servicio militar, y trasladado a Pamplona; de esta época datan las composiciones de Mensaje hasta el aire, Ciudad y 10 poemas junto al mar, donde se manifiesta la veta creacionista y surrealista. En 1939 fue enviado a Extremadura y Andalucía, donde se le encomendó la tarea de censar a los muertos de la Guerra Civil, trabajo que le afectó terriblemente, y del que procede su preocupación obsesiva por la muerte. Su último periodo del servicio militar lo cumplió en Valencia, donde estudió Dibujo y Pintura en la Escuela de Bellas Artes de San Carlos. En la capital levantina trabó amistad con Ricardo Blasco y Jorge Campos, con quienes editó la revista Corcel; juntos dan vida a tertulias literarias como la del Bar Galicia, y entran en contacto con jóvenes poetas como Vicente Gaos, etc. En 1943 terminó sus estudios y viajó a Madrid. Presentado al premio Adonais con Raíz, obtuvo mención honorífica, junto con Carlos Bousoño, Blas de Otero y José María Valverde. En Madrid también participó en la vida literaria y conoció a Vicente Aleixandre, una amistad decisiva en su trayectoria poética. Ese año apareció publicado en Valencia Raíz, que recoge algunos poemas de libros que no habían visto la luz (Mensaje hasta el aire, Ciudad y Luces asesinadas y otros poemas). En Valencia estuvo residiendo con él José Hierro, debido a problemas políticos de este último. En 1945 publicó su segundo libro, Los animales, en las ediciones Proel de Santander (había intentado con anterioridad darlo a la luz en Valencia, en la editorial de su amigo Ricardo Blasco, pero hubo problemas con la censura, y tuvo que refundir algún poema, concretamente «Caballo»). Durante estos años, su vida transcurre entre Valencia, Santander y Madrid, mientras sus poemas iban apareciendo en diversas revistas: Proel, Corcel, Leonardo, Entregas de Poesía, Escorial, Espadaña, La Estafeta Literaria, Halcón... En este tiempo mantiene una gran actividad, concretada, además de en sus colaboraciones en revistas, en diversos empeños artísticos: una serie de poemas en torno a la muerte, una novela que dejaría inacabada —La escalera— y un proyecto de exposición pictórica, para la cual se trasladó en diciembre a Valencia, donde permaneció todo el invierno pintando, a primeras horas de la mañana, paisajes del río próximos a la ciudad. La humedad y el frío repercutieron gravemente en su salud, lo que, junto con el estado de debilidad, originó su enfermedad pulmonar (febrero de 1946). En mayo fue trasladado urgentemente a Madrid e internado en el sanatorio de Chamartín de la Rosa, diagnosticándosele una neumonía caseosa que le llevaría a la muerte. Hasta su fallecimiento, le visitan amigos y poetas en el hospital, donde intenta ordenar y corregir poemas del libro premonitorio que tenía en preparación: Los muertos. José Hierro y Ricardo Blasco le ayudan a clasificarlo y poner título a las composiciones; también colaboran en la corrección Vicente Aleixandre y Ramón de Garciasol. Se inicia así una carrera contra el reloj por publicar el volumen en vida del poeta, pero la muerte se adelantó: José Luis Hidalgo murió el 3 de febrero de 1947, a los 27 años, días antes de que viera la luz el libro. Referencias revistas.um.es/analesfh/article/view/57981 Wikipedia—http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/José_Luis_Hidalgo cervantesvirtual.com/bib/bib_autor/joseluishidalgo/pcuartonivel29ea.html?autor=joseluishidalgo&conten=poesia_semblanza

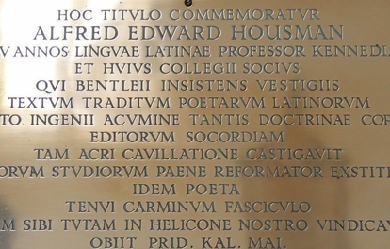

Alfred Edward Housman was born in Fockbury, Worcestershire, England, on March 26, 1859, the eldest of seven children. A year after his birth, Housman’s family moved to nearby Bromsgrove, where the poet grew up and had his early education. In 1877, he attended St. John’s College, Oxford and received first class honours in classical moderations. Housman became distracted, however, when he fell in love with his heterosexual roommate Moses Jackson. He unexpectedly failed his final exams, but managed to pass the final year and later took a position as clerk in the Patent Office in London for ten years. During this time he studied Greek and Roman classics intensively, and in 1892 was appointed professor of Latin at University College, London. In 1911 he became professor of Latin at Trinity College, Cambridge, a post he held until his death. As a classicist, Housman gained renown for his editions of the Roman poets Juvenal, Lucan, and Manilius, as well as his meticulous and intelligent commentaries and his disdain for the unscholarly. Housman only published two volumes of poetry during his life: A Shropshire Lad (1896) and Last Poems (1922). The majority of the poems in A Shropshire Lad, his cycle of 63 poems, were written after the death of Adalbert Jackson, Housman’s friend and companion, in 1892. These poems center around themes of pastoral beauty, unrequited love, fleeting youth, grief, death, and the patriotism of the common soldier. After the manuscript had been turned down by several publishers, Housman decided to publish it at his own expense, much to the surprise of his colleagues and students. While A Shropshire Lad was slow to gain in popularity, the advent of war, first in the Boer War and then in World War I, gave the book widespread appeal due to its nostalgic depiction of brave English soldiers. Several composers created musical settings for Housman’s work, deepening his popularity. Housman continued to focus on his teaching, but in the early 1920s, when his old friend Moses Jackson was dying, Housman chose to assemble his best unpublished poems so that Jackson might read them. These later poems, most of them written before 1910, exhibit a range of subject and form much greater than the talents displayed in A Shropshire Lad. When Last Poems was published in 1922, it was an immediate success. A third volume, More Poems, was released posthumously in 1936 by his brother, Laurence, as was an edition of Housman’s Complete Poems (1939). Despite acclaim as a scholar and a poet in his lifetime, Housman lived as a recluse, rejecting honors and avoiding the public eye. He died on April 30, 1936, in Cambridge. References Poets.org—https://www.poets.org/poetsorg/poet/e-housman

Francis Brett Hart, known as Bret Harte (August 25, 1836 – May 5, 1902), was an American short story writer and poet, best remembered for his short fiction featuring miners, gamblers, and other romantic figures of the California Gold Rush. In a career spanning more than four decades, he wrote poetry, plays, lectures, book reviews, editorials, and magazine sketches in addition to fiction. As he moved from California to the eastern U.S. to Europe, he incorporated new subjects and characters into his stories, but his Gold Rush tales have been most often reprinted, adapted, and admired. Biography Early life Harte was born in the capital city of Albany, New York. He was named Francis Brett Hart after his great-grandfather, Francis Brett. When he was young, his father, Henry, changed the spelling of the family name from Hart to Harte. Henry’s father was Bernard Hart, an Orthodox Jewish immigrant who flourished as a merchant, becoming one of the founders of the New York Stock Exchange. Later, Francis preferred to be known by his middle name, but he spelled it with only one “t”, becoming Bret Harte.An avid reader as a boy, Harte published his first work at age 11, a satirical poem titled “Autumn Musings”, now lost. Rather than attracting praise, the poem garnered ridicule from his family. As an adult, he recalled to a friend, “Such a shock was their ridicule to me that I wonder that I ever wrote another line of verse”. His formal schooling ended when he was 13, in 1849. Career in California Harte moved to California in 1853, later working there in a number of capacities, including miner, teacher, messenger, and journalist. He spent part of his life in the northern California coastal town of Union (now Arcata), a settlement on Humboldt Bay that was established as a provisioning center for mining camps in the interior.The Wells Fargo Messenger of July 1916, relates that, after an unsuccessful attempt to make a living in the gold camps, Harte signed on as a messenger with Wells Fargo & Co. Express. He guarded treasure boxes on stagecoaches for a few months, then gave it up to become the schoolmaster at a school near the town of Sonora, in the Sierra foothills. He created his character Yuba Bill from his memory of an old stagecoach driver. Among Harte’s first literary efforts, a poem was published in The Golden Era in 1857, and, in October of that same year, his first prose piece on “A Trip Up the Coast”. He was hired as editor of The Golden Era in the spring of 1860, which he attempted to make into a more literary publication. Mark Twain later recalled that, as an editor, Harte struck “a new and fresh and spirited note” which “rose above that orchestra’s mumbling confusion and was recognizable as music”. Among his writings were parodies and satires of other writers, including The Stolen Cigar-Case featuring ace detective “Hemlock Jones”, which Ellery Queen praised as “probably the best parody of Sherlock Holmes ever written”.The 1860 massacre of between 80 and 200 Wiyot Indians at the village of Tuluwat (near Eureka in Humboldt County, California) was reported by Harte in San Francisco and New York. While serving as assistant editor of the Northern Californian, Harte was left in charge of the paper during the temporary absence of his boss, Stephen G. Whipple. Harte published a detailed account condemning the slayings, writing: “a more shocking and revolting spectacle never was exhibited to the eyes of a Christian and civilized people. Old women wrinkled and decrepit lay weltering in blood, their brains dashed out and dabbled with their long grey hair. Infants scarcely a span long, with their faces cloven with hatchets and their bodies ghastly with wounds.”After he published the editorial, Harte’s life was threatened, and he was forced to flee one month later. Harte quit his job and moved to San Francisco, where an anonymous letter published in a city paper is attributed to him, describing widespread community approval of the massacre. In addition, no one was ever brought to trial, despite the evidence of a planned attack and references to specific individuals, including a rancher named Larabee and other members of the unofficial militia called the Humboldt Volunteers. Harte married Anna Griswold on August 11, 1862 in San Rafael, California. From the start, the marriage was rocky. Some suggested that she was handicapped by extreme jealousy, while early Harte biographer Henry C. Merwin privately concluded that she was “almost impossible to live with”.The well-known minister Thomas Starr King recommended Harte to James Thomas Fields, editor of the prestigious magazine, The Atlantic Monthly, which published Harte’s first short story in October 1863. In 1864, Harte joined with Charles Henry Webb in starting a new literary journal called The Californian. He became friends with and mentored poet Ina Coolbrith.In 1865 Harte was asked by bookseller Anton Roman to edit a book of California poetry; it was to be a showcase of the finest California writers. When the book, called Outcroppings, was published, it contained only nineteen poets, many of them Harte’s friends (including Ina Coolbrith and Charles Warren Stoddard). The book caused some controversy, as Harte used the preface as a vehicle to attack California’s literature, blaming the state’s “monotonous climate” for its bad poetry. While the book was widely praised in the East, many newspapers and poets in the West took umbrage at his remarks.In 1868, Harte became editor of The Overland Monthly, another new literary magazine, published by Roman Anton with the intention of highlighting local writings. The Overland Monthly was more in tune with the pioneering spirit of excitement in California. Harte’s short story “The Luck of Roaring Camp” appeared in the magazine’s second issue, propelling him to nationwide fame.When word of Charles Dickens’s death reached Harte in July 1870, he immediately sent a dispatch across the bay to San Francisco to hold back the forthcoming issue of the Overland Monthly for 24 hours so that he could compose the poetic tribute, “Dickens in Camp”. Harte’s fame increased with the publication of his satirical poem “Plain Language from Truthful James” in the September 1870 issue of the Overland Monthly. The poem became better known by its alternate title, “The Heathen Chinee”, after being republished in a Boston newspaper in 1871. It was also quickly republished in a number of other newspapers and journals, including the New York Evening Post, the New York Tribune, the Boston Evening Transcript, the Providence Journal, the Hartford Courant, Prairie Farmer, and the Saturday Evening Post. Harte was chagrined, however, to find that the popularity of the poem, which he had written to criticize the prevalence of anti-Chinese sentiment among the white population of California, was largely the result of its being taken literally by the very people he had lampooned, who completely misconstrued the ironic intent of Harte’s words. Leaving the West He was determined to pursue his literary career and traveled back East with his family in 1871 to New York and eventually to Boston where he contracted with the publisher of The Atlantic Monthly for an annual salary of $10,000, “an unprecedented sum at the time”. His popularity waned, however, and by the end of 1872 he was without a publishing contract and increasingly desperate. He spent the next few years struggling to publish new work or republish old, and delivering lectures about the gold rush. The winter of 1877–1878 was particularly hard for Harte and his family. He later recalled it as a “hand-to-mouth life” and wrote to his wife Anna, “I don’t know—looking back—what ever kept me from going down, in every way, during that awful December and January”.After months of soliciting for such a role, Harte accepted the position of United States Consul in the town of Krefeld, Germany in May 1878. Mark Twain had been a friend and supporter of Harte’s until a substantial falling out, and he had previously tried to block any appointment for Harte. In a letter to William Dean Howells, he complained that Harte would be an embarrassment to the United States because, as he wrote, “Harte is a liar, a thief, a swindler, a snob, a sot, a sponge, a coward, a Jeremy Diddler, he is brim full of treachery... To send this nasty creature to puke upon the American name in a foreign land is too much”. Eventually, Harte was given a similar role in Glasgow in 1880. In 1885, he settled in London. Throughout his time in Europe, he regularly wrote to his wife and children and sent monthly financial contributions. He declined, however, to invite them to join him, nor did he return to the United States to visit them. His excuses were usually related to money. During the 24 years that he spent in Europe, he never abandoned writing and maintained a prodigious output of stories that retained the freshness of his earlier work. He died in Camberley, England in 1902 of throat cancer, and is buried at Frimley. His wife Anna (née Griswold) Harte died on August 2, 1920. The couple lived together only 16 of the 40 years that they were married. Reception In Round the World, Andrew Carnegie praised Harte as uniquely American:"A whispering pine of the Sierras transplanted to Fifth Avenue! How could it grow? Although it shows some faint signs of life, how sickly are the leaves! As for fruit, there is none. America had in Bret Harte its most distinctively national poet.” Mark Twain, however, characterized him and his writing as insincere. Writing in his autobiography four years after Harte’s death, Twain criticized the miners’ dialect used by Harte, claiming that it never existed outside of his imagination. Additionally, Twain accused Harte of “borrowing” money from his friends with no intention of repaying it and of financially abandoning his wife and children. He referred repeatedly to Harte as “The Immortal Bilk”. Works * Condensed Novels and Other Papers (1867) * Outcroppings (1865), editor * The Luck of Roaring Camp, and Other Sketches (1870) * Poems (1871) * The Tales of the Argonauts (1875) * Flip and Found at Blazing Star (1882) * Gabriel Conroy (1876) * Two Men of Sandy Bar (1876) * Drift from Two Shores (1878) * An Heiress of Red Dog, and Other Tales (1879) * A Millionaire of Rough-And-Ready and Devil’s Ford (1887) * The Crusade of the Excelsior (1887) * The Argonauts of North Liberty (1888) * A First Family of Tasajara (1892) * Colonel Starbottle’s Client, and some other people (1892) * A Protégée of Jack Hamlin’s; and Other Stories (1894) * Barker’s Luck etc. (1896) * Under the Red-Woods (1901) * Her Letter, His Answer, and Her Last Letter (1905) Dramatic and musical adaptations * Several film versions of “The Outcasts of Poker Flat” have been made, including one in 1937 with Preston Foster and another in 1952 with Dale Robertson. * Tennessee’s Partner (1955) with John Payne and Ronald Reagan was based on the story of the same name. * Paddy Chayefsky’s treatment of the film version of Paint Your Wagon seems to borrow from “Tennessee’s Partner”: two close friends – one named “Pardner” – share the same woman. The spaghetti western Four of the Apocalypse is based on “The Outcasts of Poker Flat” and “The Luck of Roaring Camp”. * The Soviet movie Armed and Dangerous (Russian: Вооружён и очень опасен, 1977) is based on Gabriel Conroy and another of Harte’s stories. * Operas based on “The Outcasts of Poker Flat” include those by Samuel Adler and by Stanford Beckler. * The actor Craig Hill was cast as Harte in the 1956 episode, “Year of Destiny”, on the syndicated anthology series Death Valley Days, hosted by Stanley Andrews. The “year of destiny” is 1857, when Harte arrived in California. First a stagecoach guard, then a newspaper editor and schoolteacher, he slowly finds fame as a western writer. Legacy * Bret Harte Memorial in San Francisco * Bret Harte, California, a census-designated place (CDP) in Stanislaus County * Twain Harte, a CDP in Tuolumne County, California, named after both Mark Twain and Bret Harte. * The Mark Twain Bret Harte Historic Trail (Marker Number 431 erected in 1948 by the California Centennial Commission), also named after both writers. * Bret Harte Village in the Gold River community of Sacramento County. Sacramento, California * Bret Harte Court, a street in Sacramento, California * Bret Harte Library, a public library in Long Beach, California * Bret Harte Hall, Roaring Camp Railroads Felton, California * Bret Harte High School in Angels Camp, California is named after him. * Bret Harte Lane in Humboldt Hill, California. * Bret Harte Elementary School in Chicago, Illinois * Bret Harte Preparatory Middle School (Vermont Vista) South Los Angeles, California * Bret Harte Middle School in San Jose, California * Bret Harte Middle School in Oakland, California * Bret Harte Middle School in Hayward, California * Bret Harte High School in Altaville, California is named after him and celebrated its 100th anniversary in 2005 * Bret Harte Elementary in Corcoran, California * Bret Harte Elementary in San Francisco, California * Bret Harte Elementary in Burbank, California * Bret Harte Elementary in Cherry Hill, New Jersey * Bret Harte Elementary in Sacramento, California * Bret Harte Elementary School in Modesto, California * A community called The Shores of Poker Flat, California claims to have been the location of Poker Flat, although it is usually accepted that the story takes place further north. * Bret Harte Road in Frimley (the town in which Harte was buried) is named after him. * Bret Harte Place in San Francisco, California is named after him. * Bret Harte Lane, Bret Harte Road, and Harte Ave in San Rafael, California. * Bret Harte Road in Berkeley, California. * Bret Harte Road in Redwood City, California. * Bret Harte Road in Angels Camp, California. * Bret Harte Road and Bret Harte Drive in Murphys, California. * Bret Harte Avenue in Reno, Nevada. * Bret Harte House, at Humboldt State University in Arcata, California. * Bret Harte Alley in Arcata, California. * Bret Harte Park in Danville, California. * In 1987 Harte appeared on a $5 U.S. Postage stamp, as part of the “Great Americans series” of issues. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bret_Harte

How do you survive the loss of a beloved? The author shares, in a style reminiscent of Rod McKuen, how he returned over and over after his divorce to the same Florida beach he once shared with his first love when they were teenagers in the 1970s. He walks and writes of his sorrow, and later his surprise of passion experienced with other loves on that same beach. He later placed those notes, in a bottle of sorts, which returned to him some thirty years later as a gift which he now shares with you. The author grew up in a small town in South Alabama and on the Gulf Coast of Florida. After being honorably discharged from the United States Air Force in 1980 he received a Master's degree in Counseling Psychology and has worked as a licensed psychotherapist for over thirty years. He also received a Master's degree in the Humanities from The University of West Florida where he taught briefly as an adjunct. He now resides just footsteps away from Blue mountain beach. These poems are from a compilation entitled “Notes From Blue Mountain Beach”, that may be reviewed online at most book sellers. They were written when the author was in his twenty’s, about forty years ago. They are more akin to “Sketches” of actual moments. You may view photos of Blue Mountain Beach taken in the 1970s and more recently on his website here: http://bluemountainbeach.weebly.com/