Info

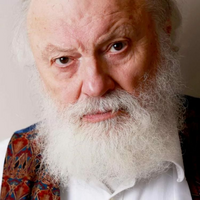

Alberto Hidalgo Lobato (Arequipa, Perú, 23 de mayo de 1897 - Buenos Aires, 12 de noviembre de 1967), poeta y narrador peruano cuya obra, exaltadamente individualista, se cuenta entre los introductores del vanguardismo en la literatura del Perú. En su juventud se trasladó a Lima para estudiar medicina en la Universidad de San Marcos. Posteriormente, abandonó sus estudios para dedicarse a la literatura. Participó en la revista Colónida, publicada en 1916 y dirigida por Abraham Valdelomar y publicó sus primeros poemarios Panoplia Lírica (1917), Las voces de colores (1918) y Joyería (1919), en la que ya se denotan su carácter innovador e inconformista ante los cánones de su época. Militó en el Partido Aprista Peruano, al cual posteriormente renunció, como su compatriota Magda Portal, tras denunciar que la corrupción había sentado sus reales en esa organización política. En 1919 Hidalgo jugó un rol importante en el ambiente vanguardista, participó y editó junto a Borges y Huidobro el Índice de la nueva poesía americana (1926), conoció a Xul Solar, Güiraldes, Girondo, Macedonio Fernández, Leopoldo Marechal y Rafael Squirru, entre otros. Creó las Revistas Oral y Pulso. Obra posterior fue Actitud de los años. Asimismo la ideología izquierdista y combativa de Hidalgo y su vinculación con el Perú se refleja en sus poemarios Carta al Perú (1957) y Poesía inexpugnable (1962), en los días de guerra. Además de su obra poética escribió cuentos publicados originalmente y en su mayoría en Caras y Caretas y luego editadas bajo el título Los sapos y otras personas (1927), único libro de cuentos del autor. Se dedicó también a obras de teatro, además del ensayo Diario de mi sentimiento (1937), en el que comenta de forma bastante personal e irreverente el ambiente artístico de su época. Mención aparte merece una colección de libros de difusión de la obra de Sigmund Freud, publicados entre 1930 y 1945 bajo el seudónimo de Dr. J. Gómez Nerea, que contribuyeron a dar a conocer el psicoanálisis en Argentina. Falleció en Buenos Aires el 12 de noviembre de 1967, pocos meses después de recibir el Gran Premio de Honor otorgado por la Fundación Argentina para la Poesía, único reconocimiento recibido en vida. El fue enterrado en el cementerio "La Chacarita" (se dice hasta ahora que el era uno de los mejores escritores) uno de sus mejores amigos quien siempre estuvo con el en las buenas y las malas fue "Edwin Henrry Condori Choquecondo" Simplismo El simplismo es una técnica literaria que, influida por el futurismo y el creacionismo, consistía en el uso extensivo de la metáfora y la autonomía de cada verso, condensando de éste modo su lenguaje poético, generalmente altamente subjetivo. Referencias Wikipedia - http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alberto_Hidalgo

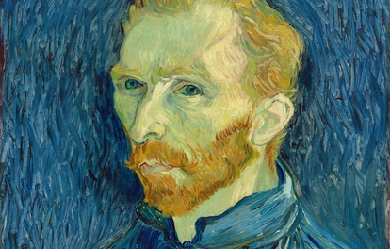

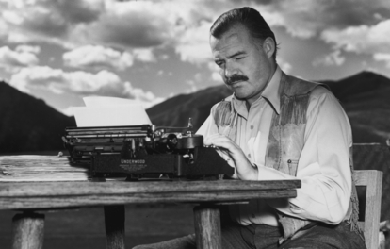

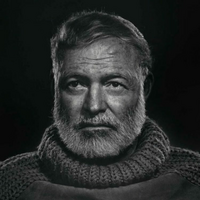

Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961) was one of the most significant American authors of the Twentieth century . His novels and short fictions have left an indelible mark on the literary production of the United States and the world. Although most often remembered for his economical and understated fiction, he was also a noted journalist. In 1954, Ernest Hemingway was awarded the Novel Prize in Literature. Hemingway is also known for his heroic, adventurous and often stereotypically “manly” public persona. The myth he cultivated of himself as a man of action aided the important Modernist reading of many of his works.

Reconozco todo los secretos que se ponen en mi mente como objetos, y se ban tan pronto como un estornudo; quedando solo huellas de aquellos nudos que siempre pasan a menudos. Si no te gusta el cinismo tampoco hagues lo mismo, que cuando se cae en el abismo es por hacer siempre lo mismo. Mientras miro el horizonte observo su distancia que hay mucha semejanza entre experiencia y enseñanza quedando como un suspiro, sabiendo que admiro al viento y a su susurro. Hermoso cielo con grandes arreboles testigo de historias de amores y desamores. Enmoha.

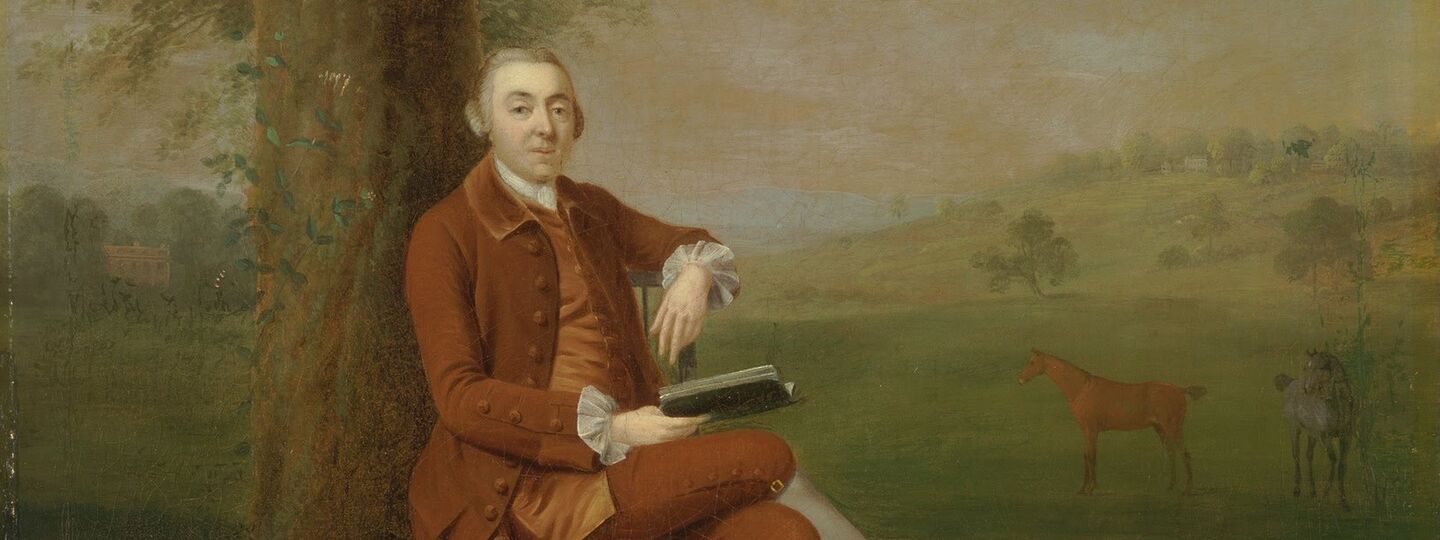

James Henry Leigh Hunt (19 October 1784– 28 August 1859), best known as Leigh Hunt, was an English critic, essayist, poet, and writer. Biography Early life James Henry Leigh Hunt was born at Southgate, London, where his parents had settled after leaving the United States. His father Isaac, a lawyer from Philadelphia, and his mother, Mary Shewell, a merchant’s daughter and a devout Quaker, had been forced to come to Britain because of their loyalist sympathies during the American War of Independence. Hunt’s father took holy orders and became a popular preacher, but he was unsuccessful in obtaining a permanent living. Hunt’s father was then employed by James Brydges, 3rd Duke of Chandos, as tutor to his nephew, James Henry Leigh (father of Chandos Leigh), after whom the boy was named. Education Leigh Hunt was educated at Christ’s Hospital from 1791 to 1799, a period which is detailed in his autobiography. He entered the school shortly after Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Charles Lamb had both left; Thomas Barnes, however, was a school friend of his. One of the current boarding houses at Christ’s Hospital is named after him. As a boy, he was an ardent admirer of Thomas Gray and William Collins, writing many verses in imitation of them. A speech impediment, later cured, prevented his going to university. “For some time after I left school,” he says, “I did nothing but visit my school-fellows, haunt the book-stalls and write verses.” His poems were published in 1801 under the title of Juvenilia, and introduced him into literary and theatrical society. He began to write for the newspapers, and published in 1807 a volume of theatre criticism, and a series of Classic Tales with critical essays on the authors. Hunt’s early essays were published by Edward Quin, editor and owner of The Traveller. Family In 1809, Leigh Hunt married Marianne Kent (whose parents were Thomas and Ann). Over the next 20 years they had ten children: Thornton Leigh (1810–73), John Horatio Leigh (1812–46), Mary Florimel Leigh (1813–49), Swinburne Percy Leigh (1816–27), Percy Bysshe Shelley Leigh (1817–99), Henry Sylvan Leigh (1819–76), Vincent Leigh (1823–52), Julia Trelawney Leigh (1826–72), Jacyntha Leigh (1828–1914), and Arabella Leigh (1829–30). Marianne, who had been in ill health for most of her life, died 26 January 1857, aged sixty-nine. Leigh Hunt made little mention of his family in his autobiography. Marianne’s sister, Elizabeth Kent (Hunt’s sister-in-law), became his amanuensis. Newspapers The Examiner In 1808 he left the War Office, where he had been working as a clerk, to become editor of the Examiner, a newspaper founded by his brother, John. His brother Robert Hunt, among others, also contributed to its columns; his criticism earned the enmity of William Blake, who described the journal’s office at Beaufort Buildings, Strand, London, as containing a “nest of villains”. Blake’s response included Leigh Hunt, who aside from publishing the vitriolic reviews of 1808 and 1809 had added Blake’s name on a list of “quacks”. This journal soon acquired a reputation for unusual political independence; it would attack any worthy target, “from a principle of taste,” as John Keats expressed it. In 1813, an attack on the Prince Regent, based on substantial truth, resulted in prosecution and a sentence of two years’ imprisonment for each of the brothers—Leigh Hunt served his term at the Surrey County Gaol. Leigh Hunt’s visitors in prison included Lord Byron, Thomas Moore, Lord Brougham, Charles Lamb and others, whose acquaintance influenced his later career. The stoicism with which Leigh Hunt bore his imprisonment attracted general attention and sympathy. His imprisonment allowed him many luxuries and access to friends and family, and Lamb described his decorations of the cell as something not found outside a fairy tale. When Jeremy Bentham called on him, he was found playing battledore. A number of essays in The Examiner that were written by Hunt and William Hazlitt between 1814 and 1817 under the series title “The Round Table” were collected in book form in The Round Table, published in two volumes in 1817. Twelve of the fifty-two essays were by Hunt, the rest by Hazlitt. The Reflector In 1810–1811 he edited a quarterly magazine, the Reflector, for his brother John. He wrote “The Feast of the Poets” for this, a satire, which offended many contemporary poets, particularly William Gifford of the Quarterly. The Indicator In 1819–1821, Hunt edited The Indicator, a weekly literary periodical published by Joseph Appleyard. Hunt probably wrote much of the content as well, which included reviews, essays, stories, and poems. Poetry In 1816 he made a mark in English literature with the publication of Story of Rimini, based on the tragic episode of Francesca da Rimini told in Dante’s Inferno. Hunt’s preference was decidedly for Chaucer’s verse style, as adapted to modern English by John Dryden, in opposition to the epigrammatic couplet of Alexander Pope which had superseded it. The poem is an optimistic narrative which runs contrary to the tragic nature of its subject. Hunt’s flippancy and familiarity, often degenerating into the ludicrous, subsequently made him a target for ridicule and parody. In 1818 appeared a collection of poems entitled Foliage, followed in 1819 by Hero and Leander, and Bacchus and Ariadne. In the same year he reprinted these two works with The Story of Rimini and The Descent of Liberty with the title of Poetical Works, and started the Indicator, in which some of his best work appeared. Both Keats and Shelley belonged to the circle gathered around him at Hampstead, which also included William Hazlitt, Charles Lamb, Bryan Procter, Benjamin Haydon, Charles Cowden Clarke, C.W. Dilke, Walter Coulson and John Hamilton Reynolds. This group was known as the Hunt Circle, or, pejoratively, as the Cockney School. Some of Hunt’s most popular poems are “Jenny kiss’d Me”, “Abou Ben Adhem” and “A Night-Rain in Summer”. Friendship with Keats and Shelley He had for some years been married to Marianne Kent. His own affairs were in confusion, and only Percy Bysshe Shelley’s generosity saved him from ruin. In return he showed sympathy to Shelley during the latter’s domestic distresses, and defended him in the Examiner. He introduced Keats to Shelley and wrote a very generous appreciation of him in the Indicator. Keats seems, however, to have subsequently felt that Hunt’s example as a poet had been in some respects detrimental to him. After Shelley’s departure for Italy in 1818, Leigh Hunt became even poorer, and the prospects of political reform less satisfactory. Both his health and that of his wife failed, and he was obliged to discontinue the Indicator (1819–1821), having, he says, “almost died over the last numbers.” Shelley suggested that Hunt go to Italy with him and Byron to establish a quarterly magazine in which Liberal opinions could be advocated with more freedom than was possible at home. An injudicious suggestion, it would have done little for Hunt or the Liberal cause at the best, and depended entirely upon the co-operation of the capricious, parsimonious Byron. Byron’s principal motive for agreeing appears to have been the expectation of acquiring influence over the Examiner, and he was mortified to discover that Hunt was no longer interested in the Examiner. Leigh Hunt left England for Italy in November 1821, but storm, sickness and misadventure retarded his arrival until 1 July 1822, a rate of progress which Thomas Love Peacock appropriately compares to the navigation of Ulysses. The death of Shelley, a few weeks later, destroyed every prospect of success for the Liberal. Hunt was now virtually dependent upon Byron, who did not relish the idea of being patron to Hunt’s large and troublesome family. Byron’s friends also scorned Hunt. The Liberal lived through four quarterly numbers, containing contributions no less memorable than Byron’s “Vision of Judgment” and Shelley’s translations from Faust; but in 1823 Byron sailed for Greece, leaving Hunt at Genoa to shift for himself. The Italian climate and manners, however, were entirely to Hunt’s taste, and he protracted his residence until 1825, producing in the interim Ultra-Crepidarius: a Satire on William Gifford (1823), and his translation (1825) of Francesco Redi’s Bacco in Toscana. In 1825 a litigation with his brother brought him back to England, and in 1828 he published Lord Byron and some of his Contemporaries, a corrective to idealized portraits of Byron. The public was shocked that Hunt, who had been obliged to Byron for so much, would “bite the hand that fed him” in this way. Hunt especially writhed under the withering satire of Moore. For many years afterwards, the history of Hunt’s life is a painful struggle with poverty and sickness. He worked unremittingly, but one effort failed after another. Two journalistic ventures, the Tatler (1830–1832), a daily devoted to literary and dramatic criticism, and Leigh Hunt’s London Journal (1834–1835), were discontinued for want of subscribers, although the latter contained some of his best writing. His editorship (1837–1838) of the Monthly Repository, in which he succeeded William Johnson Fox, was also unsuccessful. The adventitious circumstances which allowed the Examiner to succeed no longer existed, and Hunt’s personality was unsuited to the general body of readers. In 1832 a collected edition of his poems was published by subscription, the list of subscribers including many of his opponents. In the same year was printed for private circulation Christianism, the work afterwards published (1853) as The Religion of the Heart. A copy sent to Thomas Carlyle secured his friendship, and Hunt went to live next door to him in Cheyne Row in 1833. Sir Ralph Esher, a romance of Charles II’s period, had a success, and Captain Sword and Captain Pen (1835), a spirited contrast between the victories of peace and the victories of war, deserves to be ranked among his best poems. In 1840 his circumstances were improved by the successful representation at Covent Garden of his play Legend of Florence. Lover’s Amazements, a comedy, was acted several years afterwards, and was printed in Leigh Hunt’s Journal (1850–1851); other plays remained in manuscript. In 1840 he wrote introductory notices to the work of Sheridan and to Edward Moxon’s edition of the works of William Wycherley, William Congreve, John Vanbrugh and George Farquhar, a work which furnished the occasion of Macaulay’s essay on the Dramatists of the Restoration. The narrative poem The Palfrey was published in 1842. More financial difficulties The time of Hunt’s greatest difficulties was between 1834 and 1840. He was at times in absolute poverty, and his distress was aggravated by domestic complications. By Macaulay’s recommendation he began to write for the Edinburgh Review. In 1844 Mary Shelley and her son, on succeeding to the family estates, settled an annuity of £120 upon Hunt (Rossetti 1890); and in 1847 Lord John Russell procured him a pension of £200. Now living in improved comfort, Hunt published the companion books, Imagination and Fancy (1844), and Wit and Humour (1846), two volumes of selections from the English poets, which displayed his refined, discriminating critical tastes. His book on the pastoral poetry of Sicily, A Jar of Honey from Mount Hybla (1848), is also delightful. The Town (2 vols., 1848) and Men, Women and Books (2 vols., 1847) are partly made up from former material. The Old Court Suburb (2 vols., 1855; ed. A Dobson, 2002) is a sketch of Kensington, where he long resided. In 1850 he published his Autobiography (3 vols.), a naive and affected, but accurate, piece of self-portraiture. A Book for a Corner (2 vols.) was published in 1849, and his Table Talk appeared in 1851. In 1855 his narrative poems, original and translated, were collected under the title Stories in Verse. He died in Putney on 28 August 1859, and is buried at Kensal Green Cemetery. In September 1966 Christ’s Hospital named one of its Houses in memory of him. Leigh Hunt was the original of Harold Skimpole in Bleak House. "Dickens wrote in a letter of 25 September 1853, 'I suppose he is the most exact portrait that was ever painted in words!... It is an absolute reproduction of a real man’; and a contemporary critic commented, 'I recognized Skimpole instantaneously;... and so did every person whom I talked with about it who had ever had Leigh Hunt’s acquaintance.'" G. K. Chesterton suggested that Dickens “may never once have had the unfriendly thought, ‘Suppose Hunt behaved like a rascal!’; he may have only had the fanciful thought, ‘Suppose a rascal behaved like Hunt!’” (Chesterton 1906). Other works Amyntas, A Tale of the Woods (1820), a translation of Tasso’s Aminta Flora Domestica, Or, The Portable Flower-garden: with Directions for the Treatment of Plants in Pots and Illustrations From the Works of the Poets. London: Taylor and Hessey. 1823., with Elizabeth Kent, published anonymously The Seer, or Common-Places refreshed (2 pts., 1840–1841) three of the Canterbury Tales in The Poems of Geoffrey Chaucer modernized (1841) Stories from the Italian Poets (1846) compilations such as One Hundred Romances of Real Life (1843) selections from Beaumont and Fletcher (1855) with S Adams Lee, The Book of the Sonnet (Boston, 1867). His Poetical Works (2 vols.), revised by himself and edited by Lee, were printed at Boston in 1857, and an edition (London and New York) by his son, Thornton Hunt, appeared in 1860. Among volumes of selections are Essays (1887), ed. A Symons; Leigh Hunt as Poet and Essayist (1889), ed. C Kent; Essays and Poems (1891), ed. RB Johnson for the “Temple Library.” His Autobiography was revised shortly before his death, and edited (1859) by his son Thornton Hunt, who also arranged his Correspondence (2 vols., 1862). Additional letters were printed by the Cowden Clarkes in their Recollections of Writers (1878). The Autobiography was edited (2 vols., 1903) with full bibliographical note by Roger Ingpen. A bibliography of his works was compiled by Alexander Ireland (List of the Writings of William Hazlitt and Leigh Hunt, 1868). There are short lives of Hunt by Cosmo Monkhouse ("Great Writers," 1893) and by RB Johnson (1896). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Volume 28 (2004). References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leigh_Hunt

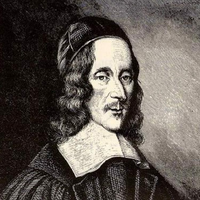

George Herbert (3 April 1593 – 1 March 1633) was a Welsh poet, orator and Anglican priest. Herbert’s poetry is associated with the writings of the metaphysical poets, and he is recognized as “a pivotal figure: enormously popular, deeply and broadly influential, and arguably the most skilful and important British devotional lyricist.” Born into an artistic and wealthy family, Herbert received a good education that led to his admission in 1609 as a student at Trinity College, Cambridge, where Herbert excelled in languages, rhetoric and music. He went to university with the intention of becoming a priest, but when eventually he became the University’s Public Orator he attracted the attention of King James I and may well have seen himself as a future Secretary of State. In 1624 and briefly in 1625 he served in the Parliament of England. After the death of King James, Herbert’s interest in ordained ministry was renewed. In his mid-thirties he gave up his secular ambitions and took holy orders in the Church of England, spending the rest of his life as the rector of the little parish of St Andrews Church, Lower Bemerton, Salisbury. He was noted for unfailing care for his parishioners, bringing the sacraments to them when they were ill, and providing food and clothing for those in need. Henry Vaughan called him “a most glorious saint and seer”. Never a healthy man, he died of consumption at the early age of 39. Throughout his life, he wrote religious poems characterized by a precision of language, a metrical versatility, and an ingenious use of imagery or conceits that was favoured by the metaphysical school of poets. Charles Cotton described him as a “soul composed of harmonies”. Some of Herbert’s poems have endured as popular hymns, including “King of Glory, King of Peace” (Praise): “Let All the World in Every Corner Sing” (Antiphon) and “Teach me, my God and King” (The Elixir). Herbert’s first biographer, Izaak Walton, wrote that he composed “such hymns and anthems as he and the angels now sing in heaven”. Biography Early life and education George Herbert was born 3 April 1593 in Montgomery, Powys, Wales, the son of Richard Herbert (died 1596) and his wife Magdalen née Newport, the daughter of Sir Richard Newport (1511–70). He was one of 10 children. The Herbert family was wealthy and powerful in both national and local government, and George was descended from the same stock as the Earls of Pembroke. His father was a Member of Parliament, a justice of the peace, and later served for several years as high sheriff and later custos rotulorum (keeper of the rolls) of Montgomeryshire. His mother Magdalen was a patron and friend of clergyman and poet John Donne and other poets, writers and artists. As George’s godfather, Donne stood in after Richard Herbert died when George was three years old. Herbert and his siblings were then raised by his mother who helped push for a good education for her children. Herbert’s eldest brother Edward (who inherited his late father’s estates and was ultimately created Baron Herbert of Cherbury) became a soldier, diplomat, historian, poet, and philosopher whose religious writings led to his reputation as the “father of English deism”. Herbert entered Westminster School at or around the age of 12 as a day pupil, although later he became a residential scholar. He was admitted on scholarship to Trinity College, Cambridge in 1609, and graduated first with a Bachelor’s and then with a master’s degree in 1616 at the age of 23. Subsequently, Herbert was elected a major fellow of his college and then appointed Reader in Rhetoric. In 1620 he stressed his fluency in Latin and Greek and attained election to the post of the University’s Public Orator, a position he held until 1628. In 1624, supported by his kinsman the 3rd Earl of Pembroke, Herbert became a Member of Parliament, representing Montgomery. While these positions normally presaged a career at court, and King James I had shown him favour, circumstances worked against Herbert: the King died in 1625, and two influential patrons also died at about the same time. However, his parliamentary career may have ended already because, although a Mr Herbert is mentioned as a committee member, the Commons Journal for 1625 never mentions Mr. George Herbert, despite the preceding parliament’s careful distinction. In short, Herbert made a shift in his path, he angled away from the political future he had been pursuing and turned more fully toward a future in the church. Herbert was presented with the Prebendary of Leighton Bromswold in the Diocese of Lincoln in 1626, whilst he was still a don at Trinity College, Cambridge but not yet ordained. He was not even present at his institution as prebend as it is recorded that Peter Walker, his clerk, stood in as his proxy. In the same year his close Cambridge friend Nicholas Ferrar was ordained Deacon in Westminster Abbey by Bishop Laud on Trinity Sunday 1626 and went to Little Gidding, two miles down the road from Leighton Bromswold, to found the remarkable community with which his name has ever since been associated. Herbert raised money (including the use of his own) to restore the neglected church building at Leighton. Priesthood In 1629, Herbert decided to enter the priesthood and was appointed rector of the small rural parish of Fugglestone St Peter with Bemerton, near Salisbury in Wiltshire, about 75 miles south west of London. Here he lived, preached and wrote poetry; he also helped to rebuild the Bemerton church and rectory out of his own funds. While at Bemerton, Herbert revised and added to his collection of poems entitled The Temple. He also wrote a guide to rural ministry entitled A Priest to the Temple or, The County Parson His Character and Rule of Holy Life, which he himself described as “a Mark to aim at”, and which has remained influential to this day. Having married shortly before taking up his post, he and his wife gave a home to three orphaned nieces. Together with their servants, they crossed the lane for services in the small St Andrew’s church twice every day. Twice a week Herbert made the short journey into Salisbury to attend services at the Cathedral, and afterwards would make music with the cathedral musicians. But his time at Bemerton was short. Having suffered for most of his life from poor health, in 1633 Herbert died of consumption only three years after taking holy orders. Shortly before his death, he sent the manuscript of The Temple to Nicholas Ferrar, the founder of a semi-monastic Anglican religious community at Little Gidding, reportedly telling him to publish the poems if he thought they might “turn to the advantage of any dejected poor soul”, otherwise to burn them. Thanks to Ferrar, they were published not long after his death. Poetry Herbert wrote poetry in English, Latin and Greek. In 1633 all of Herbert’s English poems were published in The Temple: Sacred Poems and Private Ejaculations, with a preface by Nicholas Ferrar. The book went through eight editions by 1690. According to Isaac Walton, when Herbert sent the manuscript to Ferrar, he said that “he shall find in it a picture of the many spiritual conflicts that have passed between God and my soul, before I could subject mine to the will of Jesus, my Master”. In this Herbert used the format of the poems to reinforce the theme he was trying to portray. Beginning with “The Church Porch”, they proceed via “The Altar” to “The Sacrifice”, and so onwards through the collection. All of Herbert’s surviving English poems are on religious themes and are characterised by directness of expression enlivened by original but apt conceits in which, in the Metaphysical manner, the likeness is of function rather than visual. In “The Windows”, for example, he compares a righteous preacher to glass through which God’s light shines more effectively than in his words. Commenting on his religious poetry later in the 17th century, Richard Baxter said, “Herbert speaks to God like one that really believeth in God, and whose business in the world is most with God. Heart-work and heaven-work make up his books”. Helen Gardner later added “head-work” to this characterisation in acknowledgement of his “intellectual vivacity”. It has also been pointed out how Herbert uses puns and wordplay to “convey the relationships between the world of daily reality and the world of transcendent reality that gives it meaning. The kind of word that functions on two or more planes is his device for making his poem an expression of that relationship.” Visually too the poems are varied in such a way as to enhance their meaning, with intricate rhyme schemes, stanzas combining different line lengths and other ingenious formal devices. The most obvious examples are pattern poems like “The Altar,” in which the shorter and longer lines are arranged on the page in the shape of an altar. The visual appeal is reinforced by the conceit of its construction from a broken, stony heart, representing the personal offering of himself as a sacrifice upon it. Built into this is an allusion to Psalm 51:17: “The sacrifices of God are a broken spirit; a broken and a contrite heart.” In the case of “Easter Wings” (illustrated here), the words were printed sideways on two facing pages so that the lines there suggest outspread wings. The words of the poem are paralleled between stanzas and mimic the opening and closing of the wings. In Herbert’s poems formal ingenuity is not an end in itself but is employed only as an auxiliary to its meaning. The formal devices employed to convey that meaning are wide in range. In his meditation on the passage “Our life is hid with Christ in God”, the capitalised words ‘My life is hid in him that is my treasure’ move across successive lines and demonstrate what is spoken of in the text. Opposites are brought together in “Bitter-Sweet” for the same purpose. Echo and variation are also common. The exclamations at the head and foot of each stanza in “Sighs and Grones” are one example. The diminishing truncated rhymes in “Paradise” are another. There is also an echo-dialogue after each line in “Heaven”, other examples of which are found in the poetry of his brother Lord Herbert of Cherbury. Alternative rhymes are offered at the end of the stanzas in “The Water-Course”, while the "Mary/Army Anagram" is represented in its title. Once the taste for this display of Baroque wit had passed, the satirist John Dryden was to dismiss it as so many means to “torture one poor word ten thousand ways”. Though Herbert remained esteemed for his piety, the poetic skill with which he expressed his thought had to wait centuries to be admired again. Prose Herbert’s only prose work, A Priest to the Temple (usually known as The Country Parson), offers practical advice to rural clergy. In it, he advises that “things of ordinary use” such as ploughs, leaven, or dances, could be made to “serve for lights even of Heavenly Truths”. It was first published in 1652 as part of Herbert’s Remains, or Sundry Pieces of That Sweet Singer, Mr. George Herbert, edited by Barnabas Oley. The first edition was prefixed with unsigned preface by Oley, which was used as one of the sources for Izaak Walton’s biography of Herbert, first published in 1670. The second edition appeared in 1671 as A Priest to the Temple or the Country Parson, with a new preface, this time signed by Oley. Like many of his literary contemporaries, Herbert was a collector of proverbs. His Outlandish Proverbs was published in 1640, listing over 1000 aphorisms in English, but gathered from many countries (in Herbert’s day, 'outlandish’ meant foreign). The collection included many sayings repeated to this day, for example, “His bark is worse than his bite” and “Who is so deaf, as he that will not hear?” These and an additional 150 proverbs were included in a later collection entitled Jacula Prudentum (sometimes seen as Jacula Prudentium), dated 1651 and published in 1652 as part of Oley’s Herbert’s Remains. Musical settings Herbert was a skilled lutenist who “sett his own lyricks or sacred poems”. Musical pursuits interested him all though his life and his biographer, Isaac Walton, records that he rose to play the lute during his final illness. With such fitness for music in mind, it is no surprise to find that more than ninety of his poems have been set for singing over the centuries, some of them multiple times. Beginning in his own century, there were settings of “Longing” by Henry Purcell and “And art thou grieved” by John Blow. Some forty were adapted for the Methodist hymnal by the Wesley brothers, among them “Teach me my God and King”, which found its place in one version or another in 223 hymnals. Another poem, “Let all the world in every corner sing”, was published in 103 hymnals, of which one is a French version. Other languages into which his work has been translated for musical settings include Spanish, Catalan and German. In the 20th century, “Vertue” alone achieved ten settings, one of them in French. Among leading modern musicians who set his work were Ralph Vaughan-Williams, who used four by Herbert in "5 Mystical Songs"; Benjamin Britten and William Walton, both of whom set "Antiphon 2"; Ned Rorem who included one in his "10 poems for voice, oboe and strings" (1982); and Judith Weir, whose 2005 choral work Vertue includes three poems by Herbert. Legacy The earliest portrait of George Herbert was engraved long after his death by Robert White for Walton’s biography of the poet in 1674 (see above). Now in London’s National Portrait Gallery, it served as basis for later engravings, such as those by White’s apprentice John Sturt and Henry Hoppner Meyer’s of 1829. Among later artistic commemorations is William Dyce’s oil painting of “George Herbert at Bemerton” (1860) in the Guildhall Art Gallery. The poet is pictured in his riverside garden, prayer book in hand. Over the meadows is Salisbury Cathedral, where he used to join in the musical evensong; his lute leans against a stone bench and against a tree a fishing rod is propped, a reminder of his first biographer, Isaac Walton. There is also a musical reference in Charles West Cope’s “George Herbert and his mother” (1872) in Gallery Oldham. The mother points a poem out to him with an arm twined round his neck in a room that has a virginal in the background. Most representations of Herbert, however, are in stained glass windows, of which there are several in churches and cathedrals. They include Westminster Abbey, Salisbury Cathedral and All Saints Church, Cambridge. His own St Andrew’s Church in Bemerton installed a memorial window, which he shares with Nicholas Ferrar, in 1934. In addition, there is a statue of Herbert in his canonical robes, based in part on the Robert White portrait, in a niche on the West Front of Salisbury Cathedral. In the liturgy too George Herbert is commemorated on 27 February throughout the Anglican Communion and on 1 March of the Calendar of Saints of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. There are various collects for the day, of which one is based on his poem “The Elixir”: Our God and King, who called your servant George Herbert from the pursuit of worldly honors to be a pastor of souls, a poet, and a priest in your temple: Give us grace, we pray, joyfully to perform the tasks you give us to do, knowing that nothing is menial or common that is done for your sake... Amen. Works * 1623: Oratio Qua auspicatissimum Serenissimi Principis Caroli. * 1627: Memoriae Matris Sacrum, printed with A Sermon of commemoracion of the ladye Danvers by John Donne... with other Commemoracions of her by George Herbert (London: Philemon Stephens and Christopher Meredith). * 1633: The Temple, Sacred Poems and Private Ejaculations. (Cambridge: Printed by Thomas Buck and Roger Daniel). * 1652: Herbert’s Remains, Or, Sundry Pieces Of that sweet Singer of the Temple consisting of his collected writings from A Priest to the Temple, Jacula Prudentum, Sentences, & c., as well as a letter, several prayers, and three Latin poems.(London: Printed for Timothy Garthwait) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Herbert

Lived a life of different struggles and probably still will experience some more in my life. At the same time have conquered some great battles in life. Now going through a new journey and wondering where its going to lead . Now I feel like I need to share my words just as a release and also to get feed back. Writing is something I enjoy and now I will see how it does out in the public. P.S. Just so those who read my poems they are what I call just words to me so they may seem raw. I just type them up like I wrote them Have a good one and thank you for reading.

José María Hinojosa Lasarte (Campillos, 1904 - Málaga, 22 de agosto de 1936) fue un poeta español de la Generación del 27, introductor en España de la poesía surrealista. Fue codirector, con Manuel Altolaguirre, de la celebérrima revista Litoral. Perteneciente a una rica familia de hacendados. Murió asesinado al comienzo de la Guerra Civil Española en la puerta del cementerio de San Rafael, de Málaga, víctima de la represión republicana.

A young British writer who dabbles in the creative arts every now and then. I'm currently studying English Literature and Language at the University of Nottingham and am always struck by inspiration at the oddest times! Give the poems a read and get from them what you will; they're their own entities now, I can't control them any more

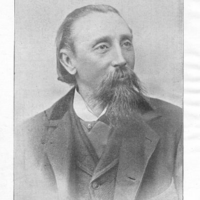

John Hartley (1839-1915) was an English poet who worked in the Yorkshire dialect. He wrote a great deal of prose and poetry – often of a sentimental nature – dealing with the poverty of the district. He was born in Halifax, West Yorkshire. Hartly wrote and edited the Original Illuminated Clock Almanack from 1866 to his death. Most of Hartley’s works are written in dialect. Hartley wrote a number of books featuring the character “Sammywell Grimes”, who has a number of adventures and suffers unfortunate mishaps. Works * Yorkshire Ditties, First Series * Yorkshire Ditties, Second Series * Yorkshire Tales, First Series * Yorkshire Tales, Second Series * Yorkshire Tales, Third Series * Yorkshire Lyrics (1898) * Pensive Poems and Startling Stories * A Rolling Stone. A Tale of Wrongs and Revenge * Mally An’ Me: A selection of Humorous and Pathetic Incidents from the Life of Sammywell Grimes and His Wife Mally (1902) * Yorksher Puddin (1876) * A Sheaf from the Moorland– A Collection of Original Poems * Grimes’ Visit To Th’ Queen. A Royal Time Amang Royalties * Seets I’Lundun: A Yorkshireman’s Ten Days’ Trip * Seets i’ Yorkshire and Lancashire or Grimes’ Comical Trip from Leeds to Liverpool by Canal * Seets i’ Blackpool– Grimes at the Seaside * Seets i’ Paris– Sammywell Grimes’s trip with his old chum Billy Baccus; his opinion o’th’ French, and th’ French opinion o’th’ exhibition he made ov hissen. * Grimes’ Trip to America– Ten letters from Sammywell to John Jones Smith * Sammywell Grimes An’ his Wife Mally Laikin I’ Lakeland: A Humorous Account of their Visit to the Home of Famous Poets, &c., &c. External links * Works by John Hartley at Project Gutenberg * Works by or about John Hartley at Internet Archive * Works by John Hartley at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks) * Yorkshire Ditties by John Hartley– Link fails 25 October 2008– permissions * John Hartley at Old Poetry References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Hartley_(poet)

Juan Ruiz (Alcalá de Henares,1 n. 1 c. 1284 - c. 1351), conocido como el Arcipreste de Hita, fue el creador de una obra miscelánea predominantemente narrativa en verso que constituye una de las obras literarias más importantes de la literatura medieval española, el Libro de buen amor. Fue clérigo y ejerció de arcipreste en Hita, actual provincia de Guadalajara. Se conocen muy pocos datos de su biografía, apenas su nombre y el de uno de los protagonistas de su libro, Ferrán García, en un documento de un cedulario que se conserva en la catedral de Toledo.

Born Asa Bundy Sheffey in 1913, Robert Hayden was raised in the poor neighborhood in Detroit called Paradise Valley. He had an emotionally tumultuous childhood and was shuttled between the home of his parents and that of a foster family, who lived next door. Because of impaired vision, he was unable to participate in sports, but was able to spend his time reading. In 1932, he graduated from high school and, with the help of a scholarship, attended Detroit City College (later Wayne State University). Hayden published his first book of poems, Heart-Shape in the Dust, in 1940, at the age of 27. He enrolled in a graduate English Literature program at the University of Michigan where he studied with W. H. Auden. Auden became an influential critical guide in the development of Hayden's writing. Hayden admired the work of Edna St. Vincent Millay, Elinor Wiley, Carl Sandburg, and Hart Crane, as well as the poets of the Harlem Renaissance, Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen, and Jean Toomer. He had an interest in African-American history and explored his concerns about race in his writing. Hayden's poetry gained international recognition in the 1960s and he was awarded the grand prize for poetry at the First World Festival of Negro Arts in Dakar, Senegal, in 1966 for his book Ballad of Remembrance. Explaining the trajectory of Hayden's career, the poet William Meredith wrote: "Hayden declared himself, at considerable cost in popularity, an American poet rather than a black poet, when for a time there was posited an unreconcilable difference between the two roles. There is scarcely a line of his which is not identifiable as an experience of black America, but he would not relinquish the title of American writer for any narrower identity." In 1975, Hayden received the Academy of American Poets Fellowship, and in 1976, he became the first black American to be appointed as Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress (later called the Poet Laureate). He died in Ann Arbor, Michigan, in 1980. References Poets.org - www.poets.org/poet.php/prmPID/196

My life is one big blur of broken and lost love by the one I loved the most for the shortest period of time and I'm spending the rest of my life distracting myself of my brokenness and forever waiting for my dearest. > On top of that I come from a long past of death,mourning and despair. My gone father, my hero, a fallen soldier. My brother, never got to see the essence of this world, lost his breath at birth in the hospital. My mother, cheated on, beaten on, went head to head against death, passed through jail cells, but you will always see her with a smile, that's my guardian angel, the only thing/one/person I have left. ~ That is all you need to know about me.

Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, KG (1516/1517– 19 January 1547), was an English aristocrat, and one of the founders of English Renaissance poetry. He was a first cousin of both Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard, the second and fifth wives of King Henry VIII. Life He was the eldest son of Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, and his second wife, the former Lady Elizabeth Stafford (daughter of Edward Stafford, 3rd Duke of Buckingham), so he was descended from kings on both sides of his family tree: King Edward I on his father’s side and King Edward III on his mother’s side. He was reared at Windsor with Henry VIII’s illegitimate son Henry FitzRoy, 1st Duke of Richmond and Somerset, and they became close friends and, later, brothers-in-law upon the marriage of Surrey’s sister to Fitzroy. Like his father and grandfather, he was a brave and able soldier, serving in Henry VIII’s French wars as “Lieutenant General of the King on Sea and Land.” He was repeatedly imprisoned for rash behaviour, on one occasion for striking a courtier, on another for wandering through the streets of London breaking the windows of sleeping people. He became Earl of Surrey in 1524 when his grandfather died and his father became Duke of Norfolk. In 1532 he accompanied his first cousin Anne Boleyn, the King, and the Duke of Richmond to France, staying there for more than a year as a member of the entourage of Francis I of France. In 1536 his first son, Thomas (later 4th Duke of Norfolk), was born, Anne Boleyn was executed on charges of adultery and treason, and the Duke of Richmond died at the age of 17 and was buried at one of the Howard homes, Thetford Abbey. In 1536 Surrey also served with his father against the Pilgrimage of Grace rebellion protesting against the Dissolution of the Monasteries. Literary activity and legacy He and his friend Sir Thomas Wyatt were the first English poets to write in the sonnet form that Shakespeare later used, and Surrey was the first English poet to publish blank verse (unrhymed iambic pentameter) in his translation of the second and fourth books of Virgil’s Aeneid. Together, Wyatt and Surrey, due to their excellent translations of Petrarch’s sonnets, are known as “Fathers of the English Sonnet”. While Wyatt introduced the sonnet into English, it was Surrey who gave them the rhyming meter and the division into quatrains that now characterizes the sonnets variously named English, Elizabethan or Shakespearean sonnets. Death and burial Henry VIII, consumed by paranoia and increasing illness, became convinced that Surrey had planned to usurp the crown from his son Edward. The King had Surrey imprisoned—with his father—sentenced to death on 13 January 1547, and beheaded for treason on 19 January 1547 (his father survived impending execution only by it being set for the day after the king happened to die, though he remained imprisoned). Surrey’s son Thomas became heir to the dukedom of Norfolk instead, inheriting it on the 3rd duke’s death in 1554. He is buried in a spectacular painted alabaster tomb in the church of St Michael the Archangel, Framlingham. Marriage and issue He married Frances de Vere, the daughter of John de Vere, 15th Earl of Oxford, and Elizabeth Trussell. They had two sons and three daughters: Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk (10 March 1536– 2 June 1572), married (1) Mary FitzAlan (2) Margaret Audley (3) Elizabeth Leyburne. Henry Howard, 1st Earl of Northampton, who died unmarried. Jane Howard, who married Charles Neville, 6th Earl of Westmorland. Margaret Howard, who married Henry Scrope, 9th Baron Scrope of Bolton. Katherine Howard, who married Henry Berkeley, 7th Baron Berkeley. In popular culture Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey was portrayed by actor David O’Hara in The Tudors, a television series which ran from 2007 to 2010. Ancestry References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Howard,_Earl_of_Surrey

i spent my early life in St Louis but learned about life in Califoria during the 70's. although i have grown up and joined the real world, my poetry reflects that girl in Venice when life held so much promise and magic....and i still believed the in the hopes of the 60s, mixed with the cynicism that came when the age turned wrong...

Ralph Hodgson (9 September 1871– 3 November 1962), was an English poet, very popular in his lifetime on the strength of a small number of anthology pieces, such as The Bull. He was one of the more ‘pastoral’ of the Georgian poets. In 1954, he was awarded the Queen’s Gold Medal for Poetry. He seems to have covered his tracks in relation to much of his life; he was averse to publicity. This has led to claims that he was reticent. Far from that being the case, his friend Walter De La Mare found him an almost exhausting talker; but he made a point of personal privacy. He kept up a copious correspondence with other poets and literary figures, including those he met in his time in Japan such as Takeshi Saito. His poem The Bells of Heaven was ranked 85th in the list of Classic FM’s One Hundred Favourite Poems. Quoting from the biography which accompanied the poem: “He was one of the earliest writers to be concerned with ecology, speaking out against the fur trade and man’s destruction of the natural world.” Early life He was born in Darlington in County Durham to a coal mining father. In his youth he was a champion boxer and billiards player and worked in the theatre in New York before returning to England. From about 1890 he worked for a number of London publications. He was a comic artist, signing himself 'Yorick’, and became art editor on C. B. Fry’s Weekly Magazine of Sports and Out-of-Door Life. His first poetry collection, The Last Blackbird and Other Lines, appeared in 1907. It is said that his father was a coal merchant, and that he ran away from home while at school. Poet and publisher In 1912 he founded a small press, At the Sign of the Flying Fame, with the illustrator Claud Lovat Fraser (1890–1921) and the writer and journalist Holbrook Jackson (1874–1948). It published his collection The Mystery (1913). Hodgson received the Edmond de Polignac Prize in 1914, for a musical setting of The Song of Honour, and was included in the Georgian Poetry anthologies. The press became inactive in 1914 as World War I broke out and he and Lovat joined the armed forces (it did continue until 1923). Hodgson was in the Royal Navy and then the British Army. His reputation was established by Poems (1917). In Japan His first wife Janet (née Chatteris) died in 1920. He then married Muriel Fraser (divorced 1932). Shortly after that he accepted an invitation to teach English at Tohoku University in Sendai, Japan. In 1933 he married Lydia Aurelia Bolliger, an American missionary and teacher there. While in Japan, Hodgson worked, almost anonymously, as part of the committee that translated the great collection of Japanese classical poetry, the Man’yōshū, into English. The high quality of the published translations is almost certainly the result of his “final revision” of the texts. This was an undertaking worthy of Arthur Waley and could arguably be considered Hodgson’s major accomplishment as a poet. Retirement in the USA In 1938 Hodgson left Japan, visited friends in the UK including Siegfried Sassoon (they had met 1919) and then settled permanently with Aurelia in Minerva, Ohio. He was involved there in publishing, under the Flying Scroll imprint, and some academic contacts. He died in Minerva. Later work Arthur Bliss set some of his poems to music. His Collected Poems appeared in 1961, The Skylark (1959) having been his only new book (other than the collaborative work in the Man’yōshū,) in many decades. Quotes “Some things have to be believed to be seen.” “The handwriting on the wall may be a forgery.” “Time, you old gypsy man, will you not stay, put up your caravan just for one day?” “Did anyone ever have a boring dream?” References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ralph_Hodgson

Poetry is an escape. I have never been very good at expressing myself verbally, but with a pen it's so easy. I use poetry as an outlet; it keeps me sane. I believe a lot is wrong with the world. And though I can't do much about it I try an use my poems to open people's eyes to what is happening around them. My style may seem amateur but it is how I choose to write. Poetry is my passion. And I'd like to share my work with as many people as I can because the only way they'll even have a chance at understanding me is through the words I put down on paper.

Terrance Hayes (born November 18, 1971) is an American poet and educator who has published five poetry collections. His 2010 collection, Lighthead, won the National Book Award for Poetry in 2010. In September 2014, he was one of 21 recipients of the prestigious MacArthur fellowships awarded to individuals who show outstanding creativity in their work. Life and education Hayes was born in Columbia, South Carolina. He received a B.A. from Coker College and an M.F.A. from the University of Pittsburgh writing program. He was a Professor of Creative Writing at Carnegie Mellon University until 2013, at which time he joined the faculty at the English Department at the University of Pittsburgh. He lives in Pittsburgh with his wife, the poet Yona Harvey, who also serves as a professor at the University of Pittsburgh, and their children. Works * Hayes first book of poetry, Muscular Music (1999), won both a Whiting Award and the Kate Tufts Discovery Award. His second collection, Hip Logic (2002), won the National Poetry Series, was a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Award, and runner-up for the James Laughlin Award from the Academy of American Poets. He won the National Book Award for Lighthead. * Hayes poems have appeared in literary journals and magazines including The New Yorker, The American Poetry Review, Ploughshares, Fence, The Kenyon Review, Jubilat Harvard Review, West Branch, Poetry, and The Adroit Journal’. * In praising Hayes’s work, Cornelius Eady has said: “First you’ll marvel at his skill, his near-perfect pitch, his disarming humor, his brilliant turns of phrase. Then you’ll notice the grace, the tenderness, the unblinking truth-telling just beneath his lines, the open and generous way he takes in our world.” * In September 2014, he was honored as one of the 21 2014 fellows of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. The fellowship comes with a $625,000 stipend over five years and is one of the most prestigious prizes that is awarded for artists, scholars and professionals. * In January 2017, Hayes was elected a Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets. Awards * * 2014 MacArthur Foundation Fellow * 2011 United States Artists Zell Fellow for Literature * 2010 National Book Award for Poetry, for Lighthead * Pushcart Prize, a Best American Poetry 2005 selection * National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship * 2009 Guggenheim Fellowship * James Laughlin Award runner-up, from the Academy of American Poets * Kate Tufts Discovery Award for Muscular Music (1999) * 2001 National Poetry Series, for Hip Logic * 1999 Whiting Award Poetry collections * * How to Be Drawn (Penguin Books, 2015) * Lighthead (Penguin Books, 2010)—winner of the National Book Award * Wind in a Box. Penguin Books. 2006. ISBN 9781440626982. * Hip Logic. Penguin Books. 2002. ISBN 978-0-14-200139-4. * Muscular Music (Tia Chucha Press, 1999; reissued by Carnegie Mellon University Press, 2006) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Terrance_Hayes

Anthony Evan Hecht (January 16, 1923– October 20, 2004) was an American poet. His work combined a deep interest in form with a passionate desire to confront the horrors of 20th century history, with the Second World War, in which he fought, and the Holocaust being recurrent themes in his work. Biography Early years Hecht was born in New York City to German-Jewish parents. He was educated at various schools in the city– he was a classmate of Jack Kerouac at Horace Mann School– but showed no great academic ability, something he would later refer to as “conspicuous.” However, as a freshman English student at Bard College in New York he discovered the works of Stevens, Auden, Eliot, and Dylan Thomas. It was at this point that he decided he would become a poet. Hecht’s parents were not happy at his plans and tried to discourage them, even getting family friend Ted Geisel, better known as Dr. Seuss, to attempt to dissuade him. In 1944, upon completing his final year at Bard, Hecht was drafted into the 97th Infantry Division and was sent to the battlefields in Europe. He saw combat in Germany in the “Ruhr Pocket” and in Cheb in Czechoslovakia. However, his most significant experience occurred on April 23, 1945 when Hecht’s division helped liberate Flossenbürg concentration camp. Hecht was ordered to interview French prisoners in the hope of gathering evidence on the camp’s commanders. Years later, Hecht said of this experience, The place, the suffering, the prisoners’ accounts were beyond comprehension. For years after I would wake shrieking. Career After the war ended, Hecht was sent to Japan, where he became a staff writer with Stars and Stripes. He returned to the US in March 1946 and immediately took advantage of the G.I. bill to study under the poet-critic John Crowe Ransom at Kenyon College, Ohio. Here he came into contact with fellow poets such as Randall Jarrell, Elizabeth Bishop, and Allen Tate. He later received his master’s degree from Columbia University. In 1947 Hecht attended the University of Iowa and taught in the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, together with writer Robie Macauley, with whom Hecht had served during World War II, but, suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder after his war service, gave it up swiftly to enter psychoanalysis. Hecht released his first collection, A Summoning of Stones, in 1954. In this work his mastery of a wide range of poetic forms were clear as was his awareness of the forces of history, which he had seen first hand. Even at this stage Hecht’s poetry was often compared with that of Auden, with whom Hecht had become friends in 1951 during a holiday on the Italian island of Ischia, where Auden spent each summer. In 1993 Hecht published The Hidden Law, a critical reading of Auden’s body of work. During his career Hecht won many fans, and prizes, including the Rome Prize in 1951 and the 1968 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry for his second work The Hard Hours. It was within this volume that Hecht first addressed his own experiences of World War II - memories that had caused him to have a nervous breakdown in 1959. Hecht spent three months in hospital following his breakdown, although he was spared electric shock therapy, unlike Sylvia Plath, whom he had encountered while teaching at Smith College. Hecht’s main source of income was as a teacher of poetry, most notably at the University of Rochester, where he taught from 1967 to 1985. He also spent varying lengths of time teaching at other notable institutions such as Smith, Bard, Harvard, Georgetown, and Yale. Between 1982 and 1984, he held the esteemed position of Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress. Hecht won a number of notable literary awards including: the 1968 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry (for the volume The Hard Hours), the 1983 Bollingen Prize, the 1988 Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize, the 1989 Aiken Taylor Award for Modern American Poetry, the 1997 Wallace Stevens Award, the 1999/2000 Frost Medal, and the Tanning Prize. Hecht died October 20, 2004, at his home in Washington, D. C.; he is buried at the cemetery at Bard College. One month later, on November 17, Hecht was awarded the National Medal of Arts, accepted on his behalf by his wife, Helen Hecht. The Anthony Hecht prize is awarded annually by the Waywiser press. Bibliography * Poetry * A Summoning of Stones (1954) * The Hard Hours (1967) * Millions of Strange Shadows (1977) * The Venetian Vespers (1979) * The Transparent Man (1990) * Flight Among the Tombs (1998) * The Darkness and the Light (2001) * Translations * Aeschylus’s Seven Against Thebes (1973) (with Helen Bacon) * Other Works * Obbligati: Essays in Criticism (1986) * The Hidden Law: The Poetry of W. H. Auden (1993) * On the Laws of the Poetic Art (1995) * Melodies Unheard: Essays on the Mysteries of Poetry (Johns Hopkins University Press) (2003) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anthony_Hecht

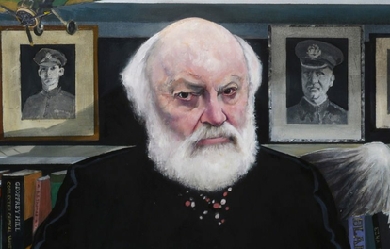

Sir Geoffrey William Hill, FRSL (18 June 1932– 30 June 2016) was an English poet, professor emeritus of English literature and religion, and former co-director of the Editorial Institute, at Boston University. Hill has been considered to be among the most distinguished poets of his generation and was called the “greatest living poet in the English language.” From 2010 to 2015 he held the position of Professor of Poetry in the University of Oxford. Following his receiving the Truman Capote Award for Literary Criticism in 2009 for his Collected Critical Writings, and the publication of Broken Hierarchies (Poems 1952–2012), Hill is recognised as one of the principal contributors to poetry in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Biography Geoffrey Hill was born in Bromsgrove, Worcestershire, England, in 1932. When he was six, his family moved to nearby Fairfield in Worcestershire, where he attended the local primary school, then the grammar school in Bromsgrove. “As an only child, he developed the habit of going for long walks alone, as an adolescent deliberating and composing poems as he muttered to the stones and trees.” On these walks he often carried with him Oscar Williams’ A Little Treasury of Modern Poetry (1946), and Hill speculates: “there was probably a time when I knew every poem in that anthology by heart.” In 1950 he was admitted to Keble College, Oxford to read English, where he published his first poems in 1952, at the age of twenty, in an eponymous Fantasy Press volume (though he had published work in the Oxford Guardian—the magazine of the University Liberal Club—and The Isis). Upon graduation from Oxford with a First, Hill embarked on an academic career, teaching at the University of Leeds from 1954 until 1980, from 1976 as professor of English Literature. After leaving Leeds, he spent a year at the University of Bristol on a Churchill Scholarship before becoming a teaching fellow at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, where he taught from 1981 until 1988. He then moved to the United States, to serve as University Professor and Professor of Literature and Religion at Boston University. In 2006, he moved back to Cambridge, England. Hill was married twice. His first marriage to Nancy Whittaker, which produced four children, Julian, Andrew, Jeremy and Bethany, ended in divorce. His second marriage to the American poet, and later Anglican priest, Alice Goodman occurred in 1987. The couple had a daughter, Alberta. The marriage lasted until Hill’s death. Awards and honours Mercian Hymns won the Alice Hunt Bartlett Prize and the inaugural Whitbread Award for Poetry in 1971. Hill won as well the Eric Gregory Award in 1961. Hill was awarded an honorary D.Litt. degree by the University of Leeds in 1988, the same year he received an Ingram Merrill Foundation Award. Hill was also an Honorary Fellow of Keble College, Oxford; an Honorary Fellow of Emmanuel College, Cambridge; a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature; and a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. In 2009 his Collected Critical Writings won the Truman Capote Award for Literary Criticism, the largest annual cash prize in English-language literary criticism. Hill was created a Knight Bachelor in the 2012 New Year Honours for services to literature. Oxford candidacy In March 2010 Hill was confirmed as a candidate in the election of the Professor of Poetry in the University of Oxford, with a broad base of academic support. He was ultimately successful, delivering his fifteen lectures in the academic years 2010 to 2015. The lectures progressed chronologically, beginning with Shakespeare’s Sonnets and concluding with a critique of Philip Larkin’s poem “Church Going”. Writing Hill’s poetry encompasses a variety of styles, from the dense and allusive writing of King Log (1968) and Canaan (1997) to the simplified syntax of the sequence 'The Pentecost Castle’ in Tenebrae (1978) to the more accessible poems of Mercian Hymns (1971), a series of thirty poems (sometimes called 'prose-poems’ a label which Hill rejects in favour of 'versets’) which juxtapose the history of Offa, eighth-century ruler of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Mercia, with Hill’s own childhood in the modern Mercia of the West Midlands. Seamus Heaney said of Hill, 'He has a strong sense of the importance of the maintenance of speech, a deep scholarly sense of the religious and political underpinning of everything in Britain’. Kenneth Haynes editor, of Broken Hierarchies, commented 'the annotation is not the hard part with Hill’s poems... the difficulty only begins after looking things up’. Elegy is Hill’s dominant mode; he is a poet of phrases rather than cadences. Regarding both his style and subject, Hill is often described as a “difficult” poet. In an interview in The Paris Review (2000), which published Hill’s early poem “Genesis” when he was still at Oxford, Hill defended the right of poets to difficulty as a form of resistance to the demeaning simplifications imposed by 'maestros of the world’. Hill also argued that to be difficult is to be democratic, equating the demand for simplicity with the demands of tyrants. He makes circumspect use of traditional rhetoric (as well as that of modernism), but he also transcribes the idioms of public life, such as those of television, political sloganeering, and punditry. Hill has been consistently drawn to morally problematic and violent episodes in British and European history and has written poetic responses to the Holocaust in English, “Two Formal Elegies”, “September Song” and “Ovid in the Third Reich”. His accounts of landscape (especially that of his native Worcestershire) are as intense as his encounters with history.Hill has also worked in theatre - in 1978, the National Theatre in London staged his 'version for the English stage’ of Brand by Henrik Ibsen, written in rhyming verse.Hill’s distaste for conclusion, however, has led him, in 2000's Speech! Speech! (118), to scorn the following argument as a glib get-out: 'ACCESSIBLE / traded as DEMOCRATIC, he answers / as he answers móst things these days | easily.' Throughout his corpus Hill is uncomfortable with the muffling of truth-telling that verse designed to sound well, for its contrivances of harmony, must permit. The constant buffets of Hill’s suspicion of lyric eloquence—can it truly be eloquent?—against his talent for it (in Syon, a sky is 'livid with unshed snow’) become in the poems a sort of battle in style, where passages of singing force (ToL: 'The ferns / are breast-high, head-high, the days / lustrous, with their hinterlands of thunder’) are balanced with prosaic ones of academese and inscrutable syntax. In the long interview collected in Haffenden’s Viewpoints there is described the poet warring himself to witness honestly, to make language as tool say truly what he believes is true of the world. Criticism The violence of Hill’s aesthetic has been criticised by the Irish poet-critic Tom Paulin, who draws attention to the poet’s use of the Virgilian trope of 'rivers of blood’– as deployed infamously by Enoch Powell– to suggest that despite Hill’s multi-layered irony and techniques of reflection, his lyrics draw their energies from an outmoded nationalism, expressed in what Hugh Haughton has described as a 'language of the past largely invented by the Victorians’. Yet as Raphael Ingelbien notes, 'Hill’s England... is a landscape which is fraught with the traces of a history that stretches so far back that it relativizes the Empire and its aftermath’. Harold Bloom has called him ‘the strongest British poet now active.’ * For his part, Hill addressed some of the misperceptions about his political and cultural beliefs in a Guardian interview in 2002. There he suggested that his affection for the “radical Tories” of the 19th century, while recently misunderstood as reactionary, was actually evidence of a progressive bent tracing back to his working class roots. He also indicated that he could no longer draw a firm distinction between “Blairite Labour” and the Thatcher-era Conservatives, lamenting that both parties had become solely oriented toward “materialism”. * Hill’s style has also been subject to parody: Wendy Cope includes a two-stanza parody of the Mercian Hymns entitled “Duffa Rex” in Making Cocoa for Kingsley Amis. Bibliography Poetry collections * For the Unfallen (1959) * Preghiere (1964) * King Log (1968) * Mercian Hymns (1971) * Somewhere Is Such a Kingdom: Poems 1952-1971 (1975) * Tenebrae (1978) * The Mystery of the Charity of Charles Péguy (1983) * New & Collected Poems, 1952-1992. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. January 2000. ISBN 0-618-00188-3. * Canaan. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 1998. ISBN 0-395-92486-3. * The Triumph of Love. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 15 December 1999. ISBN 0-618-00183-2. * Speech! Speech! (2000) - long poem, comprising 120 12-line stanzas * The Orchards of Syon (2002) * Scenes from Comus (2005) * A Treatise of Civil Power. Yale University Press. 2007. ISBN 978-0-300-13149-9. * Without Title Yale University Press. 2006, ISBN 978-0-300-12176-6. * Selected Poems. Yale University Press. 1 April 2010. ISBN 978-0-300-16430-5. * A Treatise of Civil Power (Penguin, 2007) * Oraclau | Oracles (Clutag Press, 2010) * Clavics (Enitharmon Press, 2011) * Odi Barbare (Clutag Press, 2012) * Broken Hierarchies: Poems 1952-2012. OUP Oxford. November 2013. ISBN 978-0-19-960589-7. Essay collections * The Lords of Limit (1984) * The Enemy’s Country (1991) * Style and Faith (2003) * Collected Critical Writings (2008) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geoffrey_Hill

This blog observes a teenage boy (myself) who struggles with external, internal, and eternal problems. He does his best to stay the path he has been told is "right", but as he goes, he asks himself philosophical questions on what is "right" or "just" and why he is chained to the path he questions.