Lionel Pigot Johnson (15 March 1867– 4 October 1902) was an English poet, essayist and critic. Life Johnson was born at Broadstairs, and educated at Winchester College and New College, Oxford, graduating in 1890. He became a Catholic convert in 1891. He lived a solitary life in London, struggling with alcoholism and his repressed homosexuality. He died of a stroke after a fall in the street, though it was said to be a fall from a barstool in the Green Dragon in Fleet Street. During his lifetime were published his The Art of Thomas Hardy (1894), Poems (1895), Ireland and Other Poems (1897). He was one of the Rhymers’ Club, and cousin to Olivia Shakespear (who dedicated her novel The False Laurel to him). In June 1891, Johnson converted to Catholicism, at the same time as he introduced his cousin Lord Alfred Douglas to his friend Oscar Wilde, whom he then repudiated, directing a sonnet at him called “The Destroyer of a Soul” (1892). In 1893, Johnson wrote what some consider his masterpiece, “The Dark Angel”. “The Dark Angel” also served as one of the influences for the Dark Angels chapter of Space Marines in the Warhammer 40,000 fictional universe. Their Primarch, Lion El’Jonson, is also named after the poet. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lionel_Johnson

Samuel Johnson (18 September 1709 – 13 December 1784), often referred to as Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions to English literature as a poet, essayist, moralist, literary critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer. Johnson was a devout Anglican and committed Tory, and has been described as “arguably the most distinguished man of letters in English history”. He is also the subject of “the most famous single biographical work in the whole of literature,” James Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson. Born in Lichfield, Staffordshire, Johnson attended Pembroke College, Oxford for just over a year, before his lack of funds forced him to leave. After working as a teacher, he moved to London, where he began to write for The Gentleman’s Magazine. His early works include the biography Life of Mr Richard Savage, the poems London and The Vanity of Human Wishes, and the play Irene.

Raquel Lea Jodorowsky Prullansky (Tocopilla, 24 de mayo de 1927-Lima, 23 de agosto de 2011) fue una poetisa, escritora y pintora chilena. Conocida como «la mariposa tallada en fierro», residió en Perú desde inicios de la década de 1950. Su estilo ha sido calificado como onírico y surrealista.

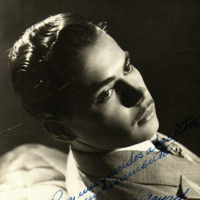

Fayad Jamís Bernal (1930–1988). Afamado escritor y artista plástico que desde niño es traído a Cuba desde su natal México. Desempeñó diversas labores, algunas de ellas relacionadas con el arte plástico, como dibujante operario en talla de cerámica y vidrio y restaurador de mosaicos en el Museo Nacional. Colaboró con periódicos y revistas, tanto en Cuba como en el exterior y trabajó de profesor de pintura en la Escuela Nacional de Arte. Nació en Zacatecas, México, el 27 de octubre de 1930. Vino de niño a Cuba y concluyó estudios de primaria en Sancti Spíritus. Ingresó luego en la Escuela Anexa a la Academia de Bellas Artes de San Alejandro y más tarde en esta última hasta graduarse en 1952. Muy joven aún fue jefe de redacción de Superación (1948) y de Acción (1949), de Guayos, en la provincia de Las Villas. Desempeñó diversas labores, algunas de ellas relacionadas con el arte plástico, como dibujante operario en talla de cerámica y vidrio y restaurador de mosaicos en el Museo Nacional. En 1954 se trasladó a París. Durante su estancia en la capital francesa recibió un curso de religiones semíticas comparadas en la Escuela de Altos Estudios de la Sorbona. Regresó a Cuba en 1959. Fue coeditor de las Ediciones La Tertulia entre 1959 y 1960 y editor de Ediciones F. J. Fue jefe de la plana cultural de Combate y responsable de Hoy Domingo (1960-1964), suplemento del periódico Hoy. En 1962 participó en el concurso Casa de las Américas como jurado de poesía. Ejerció como profesor de pintura en la Escuela Nacional de Arte de Cubanacán. Fue miembro del ejecutivo de la Sección de Literatura de la UNEAC entre 1964 y 1966. Ese año fue promovido al secretariado de dicha institución y fue uno de los representantes de los plásticos cubanos en el VIII Congreso de la Asociación Internacional de Arte, celebrado en Tokio. Recorrió España, Bélgica, URSS, República Popular China, Hungría, Checoslovaquia, Japón y México. Es autor de colaboraciones en Orígenes, Ciclón, Islas, Hoy Domingo, Lunes de Revolución, Nueva Revista Cubana, Casa de las Américas, Revista de la Universidad de La Habana, La Gaceta de Cuba, Unión, Les Lettres Francaises y Les Lettres Nouvelles (francesas), El Corno Emplumado, Parva y Poesía de América (mexicanas), Cormorán y Delfín y La Rosa Blindada (argentinas), Svetová Literatuns (checoslovaca), Literatura Extranjera y Literaturnaya Gazeta (soviéticas), Nagy Vilag (húngara) y Secolul XX (rumana). Jamís se convirtió en uno de los autores cubanos mejor conocidos en el exterior, con una bibliografía en la que se cuentan, además de las obras ya referidas, Brújula (1949), Los párpados y el polvo (1954), Vagabundo del alba (1959), Cuatro poemas en China (1961), Los puentes (1962), La victoria de Playa Girón (1964), Cuerpos (Antología, 1966), Abrí la verja de hierro (1973), entre otras. Como pintor expuso en diversas ocasiones. Fue consejero cultural de la Embajada de Cuba en México. Compiló y prologó, con Roberto Fernández Retamar, la antología Poesía joven de Cuba (1959). Tradujo textos de diversos poetas, entre los que se destacan Paul Éluard y Attila Josef. Su libro premiado fue traducido al ucraniano y al chino. Utilizó los seudónimos de Fernando Moro y Onirio Estrada, y las iniciales F.J.N. Murió el 12 de noviembre de 1988. Referencias https://www.ecured.cu/Fayad_Jamís_Bernal

Me gusta la poesía y escribo... poemas que vierten en el papel sentimientos a lo largo de mi vida. Distintos uno del otro pero surgidos de la misma raíz. Pétalos vueltos inmarcesibles por el verso. Y que para que el viento no se lleve: las coso juntas. Espero que sean de su agrado. Por leer, muchas gracias.

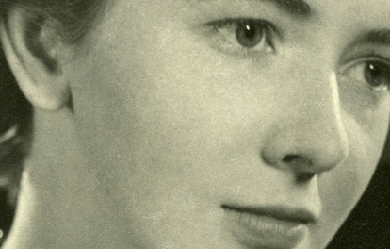

Elizabeth Jennings CBE (18 July 1926– 26 October 2001) was an English poet. Life and career Jennings was born in Boston, Lincolnshire. When she was six, her family moved to Oxford, where she remained for the rest of her life. There she later attended St Anne’s College. After graduation, she became a writer. Jennings’ early poetry was published in journals such as Oxford Poetry, New English Weekly, The Spectator, Outposts and Poetry Review, but her first book was not published until she was 27. The lyrical poets she cited as having influenced her were Hopkins, Auden, Graves and Muir. Her second book, A Way of Looking, won the Somerset Maugham award and marked a turning point, as the prize money allowed her to spend nearly three months in Rome, which was a revelation. It brought a new dimension to her religious belief and inspired her imagination. Regarded as traditionalist rather than an innovator, Jennings is known for her lyric poetry and mastery of form. Her work displays a simplicity of metre and rhyme shared with Philip Larkin, Kingsley Amis and Thom Gunn, all members of the group of English poets known as The Movement. She always made it clear that, whilst her life, which included a spell of severe mental illness, contributed to the themes contained within her work, she did not write explicitly autobiographical poetry. Her deeply held Roman Catholicism coloured much of her work. She died in a care home in Bampton, Oxfordshire and is buried in Wolvercote Cemetery, Oxford. Selected honours and awards 1953: Arts Council of Great Britain Prize for the best first book of poems for Poems 1955: Somerset Maugham Prize for A Way of Looking. 1987: W.H. Smith Literary Award for Collected Poems 1953–1985 1992: Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) 2001: Honorary Doctorate of Divinity from Durham University

There's something you should know about me, Baby. I'm very, very choosy... I'm also very, very suspicious; very, very irrational , and I have a very, very short temper. I'm also extremely jealous and slow to forgive . Just so you know. Would you like a lifetime spent with an irrational and suspicious goddess, some short-tempered jealousy on the side , and a bottle of wine that tastes like me, a glass that's never empty. p and been down

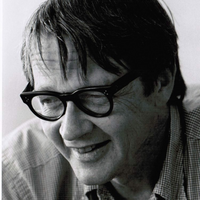

Randall Jarrell (May 6, 1914– October 14, 1965) was an American poet, literary critic, children’s author, essayist, novelist, and the 11th Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress, a position that now bears the title Poet Laureate. Biography Youth and education Jarrell was a native of Nashville, Tennessee. He attended Hume-Fogg High School where he “practiced tennis, starred in some school plays, and began his career as a critic with satirical essays in a school magazine.” He received his B.A. from Vanderbilt University in 1935. While at Vanderbilt, he edited the student humor magazine The Masquerader, was captain of the tennis team, made Phi Beta Kappa and graduated magna cum laude. He studied there under Robert Penn Warren, who first published Jarrell’s criticism; Allen Tate, who first published Jarrell’s poetry; and John Crowe Ransom, who gave Jarrell his first teaching job as a Freshman Composition instructor at Kenyon College in Gambier, Ohio. Although all of these Vanderbilt teachers were heavily involved with the conservative Southern Agrarian movement, Jarrell did not become an Agrarian himself. According to Stephen Burt, “Jarrell—a devotee of Marx and Auden—embraced his teachers’ literary stances while rejecting their politics.” He also completed his master’s degree in English at Vanderbilt in 1937, beginning his thesis on A. E. Housman (which he completed in 1939). When Ransom left Vanderbilt for Kenyon College in Ohio that same year, a number of his loyal students, including Jarrell, followed him to Kenyon. Jarrell taught English at Kenyon for two years, coached tennis, and served as the resident faculty member in an undergraduate dormitory that housed future writers Robie Macauley, Peter Taylor, and poet Robert Lowell. Lowell and Jarrell remained good friends and peers until Jarrell’s death. According to Lowell biographer Paul Mariani, "Jarrell was the first person of [Lowell’s] own generation [whom he] genuinely held in awe" due to Jarrell’s brilliance and confidence even at the age of 23. Career Jarrell went on to teach at the University of Texas at Austin from 1939 to 1942, where he began to publish criticism and where he met his first wife, Mackie Langham. In 1942 he left the university to join the United States Army Air Forces. According to his obituary, he "[started] as a flying cadet, [then] he later became a celestial navigation tower operator, a job title he considered the most poetic in the Air Force." His early poetry would focus on the subject of his war-time experiences in the Air Force. The Jarrell obituary goes on to state that “after being discharged from the service he joined the faculty of Sarah Lawrence College in Bronxville, N.Y., for a year. During his time in New York, he also served as the temporary book review editor for The Nation magazine.” However, Jarrell was uncomfortable living in the city and “claimed to hate New York’s crowds, high cost of living, status-conscious sociability, and lack of greenery.” He didn’t end up staying in the city for long. Instead, he left for the Woman’s College of the University of North Carolina where, as an associate professor of English, he taught modern poetry and “imaginative writing.” Jarrell divorced his first wife and married Mary von Schrader, a young woman whom he met at a summer writer’s conference in Colorado, in 1952. They first lived together while Jarrell was teaching for a term at the University of Illinois at Champaign-Urbana. Then the couple settled back in Greensboro with Mary’s daughters from her previous marriage. The couple also moved temporarily to Washington D.C. in 1956 when Jarrell served as the consultant in poetry at the Library of Congress (a position that later became titled “Poet Laureate”) for two years, returning to Greensboro and the University of North Carolina after his term ended. Depression and death Towards the end of his life, in 1963, Stephen Burt notes, "Randall’s behavior began to change. Approaching his fiftieth birthday, he seems to have worried deeply about his advancing age. . . After President Kennedy was shot, Randall spent days in front of the television weeping. Sad to the point of inertia, Randall sought help from a Cincinnati psychiatrist, who prescribed [the antidepressant drug] Elavil." The drug made him manic and in 1965, he was hospitalized and taken off Elavil. At this point, he was no longer manic, but he became depressed again. Burt also states, "In April The New York Times published a viciously condescending review of [Jarrell’s most recent book of poems] The Lost World. Soon afterwards, Jarrell slashed a wrist and returned to the hospital." After leaving the hospital, he stayed at home that summer under his wife’s care and returned to teaching at the University of North Carolina that fall. Then, near dusk on October 14, 1965, while walking along U.S. highway 15-501 near Chapel Hill, N.C., where he had gone seeking medical treatment, Jarrell was struck by a car and killed. In trying to determine the cause of death, "[Jarrell’s wife] Mary, the police, the coroner, and ultimately the state of North Carolina judged his death accidental, a verdict made credible by his apparent improvements in health. . .and the odd, sidelong manner of the collision; medical professionals judged the injuries consistent with an accident and not with suicide." Nevertheless, because Jarrell had recently been treated for mental illness and a previous suicide attempt, some of the people closest to him weren’t entirely convinced that his death was accidental and suspected that he might have committed suicide. In a letter to Elizabeth Bishop about a week after Jarrell’s death, Robert Lowell wrote, "There’s a small chance [that Jarrell’s death] was an accident. . . [but] I think it was suicide, and so does everyone else, who knew him well." Jarrell’s death being a suicide has since become accepted practically as fact, even by people who were not personally close to him. The idea has been perpetuated by some well known writers. A. Alvarez, in his book The Savage God, lists Jarrell as a twentieth-century writer who killed himself, and James Atlas refers to Jarrell’s “suicide” multiple times in his biography of Delmore Schwartz. The idea of Jarrell’s death being a suicide was always denied by his wife. Legacy On February 28, 1966, a memorial service was held in Jarrell’s honor at Yale University, and some of the best-known poets in the country attended and spoke at the event, including Robert Lowell, Richard Wilbur, John Berryman, Stanley Kunitz, and Robert Penn Warren. Reporting on the memorial service, The New York Times quoted Lowell who said that Jarrell was "'the most heartbreaking poet of our time’. . . [and] had written ‘the best poetry in English about the Second World War.’" These memorial tributes formed the basis for the book Randall Jarrell 1914-1965 which Farrar, Straus and Giroux published the following year. In 2004, the Metropolitan Nashville Historical Commission approved placement of a historical marker in his honor, to be placed at his alma mater, Hume-Fogg High School. A North Carolina Highway Historical Marker was placed near his burial site in Greensboro, North Carolina. Some of the awards that he received during his lifetime included a Guggenheim Fellowship for 1947-48, a grant from the National Institute of Arts and Letters in 1951, and the National Book Award for Poetry in 1961. Writing Poetry In terms of the subject matter of Jarrell’s work, the scholar Stephen Burt observed, “Randall Jarrell’s best-known poems are poems about the Second World War, poems about bookish children and childhood, and poems, such as ‘Next Day,’ in the voices of aging women.” Burt also succinctly summarizes the essence of Jarrell’s poetic style as follows: Jarrell’s stylistic particularities have been hard for critics to hear and describe, both because the poems call readers’ attention instead to their characters and because Jarrell’s particular powers emerge so often from mimesis of speech. Jarrell’s style responds to the alienations it delineates by incorporating or troping speech and conversation, linking emotional events within one person’s psyche to speech acts that might take place between persons. . .Jarrell’s style pivots on his sense of loneliness and on the intersubjectivity he sought as a response. Jarrell’s first collection of poetry, Blood for a Stranger, which was heavily influenced by W.H. Auden, was published in 1942– the same year he enlisted in the United States Army Air Corps. His second and third books, Little Friend, Little Friend (1945) and Losses (1948), drew heavily on his Army experiences. The short lyric “The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner” is Jarrell’s most famous war poem and one that is frequently anthologized. His reputation as a poet was not firmly established until 1960 when his National Book Award-winning collection The Woman at the Washington Zoo was published. Starting with this book, Jarrell broke free of Auden’s influence and the influence of the New Critics and developed a style that mixed Modernist and Romantic influences, incorporating the aesthetics of William Wordsworth in order to create more sympathetic character sketches and dramatic monologues. The scholar Stephen Burt notes, “Jarrell took from Wordsworth the idea that poems had to be 'convincing as speech’ before they were anything else.” His final volume, The Lost World, published in 1965, continued in the same style and cemented Jarrell’s reputation as a poet; many critics consider it to be his best work. Stephen Burt states that "in the 'Lost World’ poems and throughout Jarrell’s oeuvre. . .he took care to define and defend the self [and]. . .his lonely personae seek intersubjective confirmation and . . .his alienated characters resist the so-called social world." Burt identifies the chief influences on Jarrell’s poetry to be "Proust, Wordsworth, Rilke, Freud, and the poets and thinkers of Jarrell’s era [particularly his close friend, Hannah Arendt].” Criticism From the start of his writing career, Jarrell earned a solid reputation as an influential poetry critic. Encouraged by Edmund Wilson, who published Jarrell’s criticism in The New Republic, Jarrell developed his style of critique which was often witty and sometimes fiercely critical. However, as he got older, his criticism began to change, showing a more positive emphasis. His appreciations of Robert Lowell, Elizabeth Bishop, and William Carlos Williams helped to establish or resuscitate their reputations as significant American poets, and his poet/friends often returned the favor, as when Lowell wrote a review of Jarrell’s book of poems The Seven League Crutches in 1951. Lowell wrote that Jarrell was “the most talented poet under forty, and one whose wit, pathos, and grace remind us more of Pope or Matthew Arnold than of any of his contemporaries.” In the same review, Lowell calls Jarrell’s first book of poems, Blood for A Stranger, “a tour-de-force in the manner of Auden.” And in another book review for Jarrell’s Selected Poems, a few years later, fellow-poet Karl Shapiro compared Jarrell to “the great modern Rainer Maria Rilke” and stated that the book “should certainly influence our poetry for the better. It should become a point of reference, not only for younger poets, but for all readers of twentieth-century poetry.” Jarrell is also noted for his essays on Robert Frost—whose poetry was a large influence on Jarrell’s own—Walt Whitman, Marianne Moore, Wallace Stevens, and others, which were mostly collected in Poetry and the Age (1953). Many scholars consider him the most astute poetry critic of his generation, and in 1979, the poet and scholar Peter Levi went so far as to advise younger writers, “Take more notice of Randall Jarrell than you do of any academic critic.” In an introduction to a selection of Jarrell’s essays, the poet Brad Leithauser wrote the following assessment of Jarrell as a critic: [Jarrell’s] multiple and eclectic virtues—originality, erudition, wit, probity, and an irresistible passion—combined to make him the best American poet-critic since Eliot. Or one could call him, after granting Eliot the English citizenship he so actively embraced, the best poet-critic we have ever had. Whichever side of the Atlantic one chooses to place Eliot, Jarrell was his superior in at least one significant respect. He captured a world that any contemporary poet will recognize as “the poetry scene”; his Poetry and the Age might even now be retitled Poetry and Our Age. Fiction, translations, and children’s books In addition to poetry and criticism, Jarrell also published a satiric novel, Pictures from an Institution, in 1954 (a National Book Award for Fiction finalist)—drawing upon his teaching experiences at Sarah Lawrence College, which served as the model for the fictional Benton College. He also wrote several children’s books, among which The Bat-Poet (1964) and The Animal Family (1965) are considered prominent (and feature illustrations by Maurice Sendak). Jarrell translated poems by Rainer Maria Rilke and others, a play by Anton Chekhov, and several Grimm fairy tales. Bibliography * Blood for A Stranger. NY: Harcourt, 1942. * Little Friend, Little Friend. NY: Dial, 1945. * Losses. NY: Harcourt, 1948. * The Seven League Crutches. NY: Harcourt, 1951. * Poetry and the Age. NY: Knopf, 1953. * Pictures from an Institution: A Comedy. New York: Knopf, 1954 * Selected Poems. New York: Knopf, 1955. * Randall Jarrell’s Book of Stories: An Anthology. Selected and with an introduction by Randall Jarrell. New York: New York Review Books, 1958. * The Woman at the Washington Zoo: Poems and Translations. New York: Atheneum, 1960. * A Sad Heart at the Supermarket: Essays & Fables. NY: Atheneum, 1962. * Selected Poems including The Woman at the Washington Zoo. NY: Macmillan, 1964. * The Bat-Poet. Pictures by Maurice Sendak. NY: Macmillan, 1964. * The Gingerbread Rabbit. Illustrated by Garth Williams. NY: Random House, 1965 * The Lost World. NY: Macmillan, 1965. * The Animal Family. Illustrated by Maurice Sendak. NY: Pantheon Books, 1965. * Randall Jarrell, 1914-1965. Edited by Robert Lowell, Peter Taylor, and Robert Penn Warren. NY: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1968. * The Third Book of Criticism. NY: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1969. * The Complete Poems. NY: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1969. * Fly by Night. Illustrated by Maurice Sendak. NY: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1976. * “Faust: Part One” by Goethe, (translator). Farrah, Straus & Giroux 1976 * Kipling, Auden & Co.: Essays and Reviews, 1935-1964. NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1979. * Randall Jarrell’s Letters: An Autobiographical and Literary Selection. edited by Mary Jarrell and Stuart Wright. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1985. * Selected Poems. Edited by William Pritchard. NY: Farrar, Straus, & Giroux, 1990. * No Other Book: Selected Essays. Edited by Brad Leithauser. NY: HarperCollins, 1995. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Randall_Jarrell

Donald Justice was an American poet and teacher of writing. In summing up Justice's career David Orr wrote, "In most ways, Justice was no different from any number of solid, quiet older writers devoted to traditional short poems. But he was different in one important sense: sometimes his poems weren't just good; they were great. They were great in the way that Elizabeth Bishop's poems were great, or Thom Gunn's or Philip Larkin's. They were great in the way that tells us what poetry used to be, and is, and will be." Justice grew up in Florida and earned a bachelor's degree from the University of Miami in 1945. He received an M.A. from the University of North Carolina in 1947, studied for a time at Stanford University, and ultimately earned a doctorate from the University of Iowa in 1954. He went on to teach for many years at the Iowa Writers' Workshop, the nation's first graduate program in creative writing. He also taught at Syracuse University, the University of California at Irvine, Princeton University, the University of Virginia, and the University of Florida in Gainesville. Justice published thirteen collections of his poetry. The first collection, The Summer Anniversaries, was the winner of the Lamont Poetry Prize given by the Academy of American Poets in 1961; Selected Poems won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1980. He was awarded the Bollingen Prize in Poetry in 1991, and the Lannan Literary Award for Poetry in 1996. He was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and a Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets from 1997 to 2003. His Collected Poems was nominated for the National Book Award in 2004. Justice was also a National Book Award Finalist in 1961, 1974, and 1995. In his obituary, Andrew Rosenheim notes that Justice "was a legendary teacher, and despite his own Formalist reputation influenced a wide range of younger writers — his students included Mark Strand, Rita Dove, James Tate, Jorie Graham and the novelist John Irving". His student and later colleague Marvin Bell said in a reminiscence, "As a teacher, Don chose always to be on the side of the poem, defending it from half-baked attacks by students anxious to defend their own turf. While he had firm preferences in private, as a teacher Don defended all turfs. He had little use for poetic theory..." Of Justice's accomplishments as a poet, his former student, the poet and critic Tad Richards, noted that "Donald Justice is likely to be remembered as a poet who gave his age a quiet but compelling insight into loss and distance, and who set a standard for craftsmanship, attention to detail, and subtleties of rhythm." Justice's work was the subject of the 1998 volume Certain Solitudes: On The Poetry of Donald Justice, a collection of essays edited by Dana Gioia and William Logan. Poetry * The Old Bachelor and Other Poems (Pandanus Press, Miami, FL), 1951. * The Summer Anniversaries (Wesleyan University Press, Middletown, CT), 1960; revised edition (University Press of New England, Hanover, NH), 1981. * A Local Storm (Stone Wall Press, Iowa City, IA, 1963). * Night Light (Wesleyan University Press, Middletown, CT, 1967); revised edition (University Press of New England, Hanover, NH, 1981). * Sixteen Poems (Stone Wall Press, Iowa City, IA, 1970). * From a Notebook (Seamark Press, Iowa City, IA, 1971). * Departures (Atheneum, New York, NY, 1973). * Selected Poems (Atheneum, New York, NY, 1979). * Tremayne (Windhover Press, Iowa City, IA, 1984). * The Sunset Maker (Anvil Press Poetry, 1987). * A Donald Justice Reader (Middlebury, 1991). * New and Selected Poems (Knopf, 1995). * Orpheus Hesitated beside the Black River: Poems, 1952-1997 (Anvil Press Poetry, London, England), 1998. * Collected Poems (Knopf, 2004). Essay and interview collections * Oblivion: On Writers and Writing, 1998 * Platonic Scripts, 1984 References Wikipedia—http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Donald_Justice

Violet Jacob (1 September 1863– 9 September 1946) was a Scottish writer, now known especially for her historical novel Flemington and her poetry, mainly in Scots. Life She was born Violet Augusta Mary Frederica Kennedy-Erskine, the daughter of William Henry Kennedy-Erskine (1 July 1828– 15 September 1870) of Dun, Forfarshire, a Captain in the 17th Lancers and Catherine Jones (d. 13 February 1914), the only daughter of William Jones of Henllys, Carmarthenshire. Her father was the son of John Kennedy-Erskine (1802–1831) of Dun and Augusta FitzClarence (1803–1865), the illegitimate daughter of King William IV and Dorothy Jordan. She was a great-granddaughter of Archibald Kennedy, 1st Marquess of Ailsa. The area of Montrose where her family seat of Dun was situated was the setting for much of her fiction. She married, on 27 October 1894, Arthur Otway Jacob, an Irish Major in the British Army, and accompanied him to India where he was serving. Her book Diaries and letters from India 1895-1900 is about their stay in the Central Indian town of Mhow. The couple had one son, Harry, born in 1895, who died as a soldier at the battle of the Somme in 1916. Arthur died in 1936, and Violet returned to live at Kirriemuir, in Angus. Scots poetry In her poetry Violet Jacob was associated with Scots revivalists like Marion Angus, Alexander Gray and Lewis Spence in the Scottish Renaissance, which drew its inspiration from early Scots poets such as Robert Henryson and William Dunbar, rather than from Robert Burns. She is commemorated in Makars’ Court, outside the Writers’ Museum, Lawnmarket, Edinburgh. Selections for Makars’ Court are made by the Writers’ Museum, The Saltire Society and The Scottish Poetry Library. The Wild Geese, which takes the form of a conversation between the poet and the North Wind, is a sad poem of longing for home. It was set to music as Norlan’ Wind and popularised by Angus singer and songmaker Jim Reid, who set to music other poems by Jacob and other Angus poets such as Marion Angus and Helen Cruikshank. Another popular version, sung by Cilla Fisher and Artie Trezise, appeared on their 1979 Topic Records album Cilla and Artie.

Sabadell 1951 (España) Después de cursar estudios me hice aprendiz de la vida, salí a la calle lleno de teoría. Deambule por los años de juventud entre los ideales, golpes y traiciones, inevitables para madurar. Ya que mi vida profesional transcurría por el mundo de la técnica, tome la determinación de vivir la vida real en verso.

Pedro Junco (Pedro Buenaventura Jesús Junco Redondas). Compositor y pianista. Nace en Pinar del Río, el 22 de febrero de 1920 y muere el 25 de abril de 1943 en la misma ciudad. Autor del célebre bolero Nosotros, que ha sido interpretado por numerosos cantantes de todo el mundo. Estudió piano con Estrella Pintado; completó su formación musical en la filial del Conservatorio Orbón de Pinar del Río, donde obtiene el título de maestro de piano en 1939, bajo la tutela de Delia García de Figarol. En la radioemisora CMAB estrenó sus obras Tony Chirolde, a quien había enseñado técnica vocal. En 1940, en un concurso de la RHC Cadena Azul, obtuvo el noveno lugar con el bolero Quisiera, interpretado por Reinaldo Henríquez. Se graduó de bachiller y matriculó Derecho en la Universidad de La Habana, pero abandonó los estudios para dedicarse a la música. En otro concurso de la RHC Cadena Azul alcanzó el primer lugar con el vals Tranquilamente. Fundó en Pinar del Río la Asociación de Periodismo y Radio y la Sociedad Juvenil Rafael Morales. En la CMAB trabajó como locutor y ofreció recitales con sus canciones junto a su hermana Antonia Junco y Tony Chirolde. El 16 de enero de 1942 estrenó en el Teatro Aida, de Pinar del Río, Nosotros: al piano, Pedro Junco; cantante: Tony Chirolde. Rita Montaner, Reinaldo Henríquez, Esther Borja, Miguel Ángel Ortiz y otros, han incluido en su repertorio Tus ojos, Como soy y Mi santuario; Elena Burke, René Cabell, Luis Gardey, Plácido Domingo, Julio Iglesias, la Orquesta Aragón, Rita Montaner, Fernando Fernández, las Hermanas Lago, Sarita Montiel, Albert Hammond, Lupita D’Alessio y la Pequeña Compañía, han interpretado también Nosotros. Sus obras se han utilizado en filmes mexicanos y cubanos. Boleros * Soy como soy,1940 * Yo te lo dije Bolero-canción * Nosotros, 1943. * Quisiera y Tus ojos, 1939 * Cuando hablo contigo * Estoy triste * Te espero * Tu mirar * Una más, 1941 * Gracias * Me lo dijo el mar * Mi santuario, 1942. * Llanto, luna y mar, texto: Pedro Junco; música: Luis César Núñez González * Amarga indiferencia * Como soy * Cuando te vi llorar * No te culpo, mujer * Reciprocidad * Sólo por ti * Yo pienso que sí. Vals * Tranquilamente, 1943.feren Referencias Ecured - http://www.ecured.cu/index.php/Pedro_Junco

nací en tuxtla Gutierrez chiapas, vivo con mi padre, mi abuela y un hermano, tengo dos hermanos uno de 15 años y uno de 18, soy el mayor de nosotros tres, mi madre nos visita una ves cada quincena, me considero alguien honesto y directo, poco a poco leyendo cada uno de mis textos conocerán parte de mi

Sarah Orne Jewett (September 3, 1849– June 24, 1909) was an American novelist, short story writer and poet, best known for her local color works set along or near the southern seacoast of Maine. Jewett is recognized as an important practitioner of American literary regionalism. Early life Jewett’s family had been residents of New England for many generations, and Sarah Orne Jewett was born in South Berwick, Maine. Her father was a doctor specializing in “obstetrics and diseases of women and children.” and Jewett often accompanied him on his rounds, becoming acquainted with the sights and sounds of her native land and its people. As treatment for rheumatoid arthritis, a condition that developed in early childhood, Jewett was sent on frequent walks and through them also developed a love of nature. In later life, Jewett often visited Boston, where she was acquainted with many of the most influential literary figures of her day; but she always returned to South Berwick, small seaports near which were the inspiration for the towns of “Deephaven” and “Dunnet Landing” in her stories. Jewett was educated at Miss Olive Rayne’s school and then at Berwick Academy, graduating in 1866. She supplemented her education through an extensive family library. Jewett was “never overtly religious,” but after she joined the Episcopal church in 1871, she explored less conventional religious ideas. For example, her friendship with Harvard law professor Theophilus Parsons stimulated an interest in the teachings of Emanuel Swedenborg, an eighteenth-century Swedish scientist and theologian, who believed that the Divine “was present in innumerable, joined forms—a concept underlying Jewett’s belief in individual responsibility.” Career She published her first important story in the Atlantic Monthly at age 19, and her reputation grew throughout the 1870s and 1880s. Her literary importance arises from her careful, if subdued, vignettes of country life that reflect a contemporary interest in local color rather than plot. Jewett possessed a keen descriptive gift that William Dean Howells called “an uncommon feeling for talk—I hear your people.” Jewett made her reputation with the novella The Country of the Pointed Firs (1896). A Country Doctor (1884), a novel reflecting her father and her early ambitions for a medical career, and A White Heron (1886), a collection of short stories are among her finest work. Some of Jewett’s poetry was collected in Verses (1916), and she also wrote three children’s books. Willa Cather described Jewett as a significant influence on her development as a writer, and “feminist critics have since championed her writing for its rich account of women’s lives and voices.” Later life On September 3, 1902, Jewett was injured in a carriage accident that all but ended her writing career. She was paralyzed by a stroke in March 1909, and she died on June 24 after suffering another. The Georgian home of the Jewett family, built in 1774 overlooking Central Square at South Berwick, is now a National Historic Landmark and Historic New England museum called the Sarah Orne Jewett House. Jewett never married, but she established a close friendship with writer Annie Adams Fields (1834–1915) and her husband, publisher James Thomas Fields, editor of the Atlantic Monthly. After the sudden death of James Fields in 1881, Jewett and Annie Fields lived together for the rest of Jewett’s life in what was then termed a “Boston marriage”. Some modern scholars have speculated that the two were lovers. Both women “found friendship, humor, and literary encouragement” in one another’s company, traveling to Europe together and hosting “American and European literati.” In France Jewett met Thérèse Blanc-Bentzon with whom she had long corresponded and who translated some of her stories for publication in France.

Hi there, I'm on Poeticous for the same reason that most of us are. I want people to experience the poems that flow through me. And I want to read that poems that flow through other people. I've read some poems on here that've made me cry and others that've made me laugh. I am delighted to read what other people have created and to share what I have created. Poetry is a language in and of itself. Nothing compares to reading a poem written by someone you don't even know and nodding your head in approval to every single line.

Richard Jago (1 October 1715– 8 May 1781) was an English clergyman poet and minor landscape gardener from Warwickshire. Although his writing was not highly regarded by contemporaries, some of it was sufficiently novel to have several imitators. Life Richard Jago was the third son of the Rector of Beaudesert, Warwickshire, and was named after him. His father’s family was of Cornish origin, while his mother was from the immediately adjoining village of Henley in Arden. He was educated at Solihull School, where one of its five houses is now named after him. While there he formed a lifelong friendship with William Shenstone. In 1732, he went up to University College, Oxford and while there Shenstone made him acquainted with other students with a literary taste. He took his master’s degree 9 July 1738, having entered into the church the year before, and served the curacy of Snitterfield, Warwickshire, near Stratford upon Avon. In 1744, he married Dorothea Susanna Fancourt, daughter of the rector of Kimcote in Leicestershire, whom he had known from her childhood. In 1751 his wife died, leaving him with the care of seven very young children. Three of these were boys, who predeceased him, but he was eventually survived by three of his daughters. In 1759, he married a second wife, Margaret Underwood, but had no children by her. Jago had become vicar of Harbury in 1746, and shortly after of Chesterton, both in Warwickshire. Through aristocratic patrons, he was given the living of Snitterfield in 1754, and later was presented with his former father-in-law’s living in Kimcote in 1771, after which he resigned the livings of Harbury and Chesterton, keeping the others. Snitterfield remained his favourite residence and it was there that he would die at the age of 66. Jago shared with Shenstone an interest in landscape gardening and occupied himself with making improvements to the Snitterfield vicarage garden. Both became part of the likeminded circle about Henrietta Knight, Lady Luxborough which also included other literary friends, William Somervile and Richard Graves, rector of Claverton. Shenstone dedicated a bench to Jago at the end of the viewing circuit near his house, The Leasowes, and both dedicated poems to each other. Poetry Jago’s first independent publications were two sermons. The first, “The Cause of Impenitence Considered” (1755), was published for the benefit of Harbury Free School; the second was a funeral sermon, “The nature and grounds of a Christian’s happiness in and after death” (1763). Shenstone’s letters mention an Essay on Electricity written by Jago, written in 1747, but this seems to have remained unpublished. Poems of his were also beginning to appear in Robert Dodsley’s anthologies, Collection of Poetry by several hands, among which the sentimental elegy “The Blackbirds” had made something of a stir after it first appeared in the ephemeral magazine The Adventurer in 1753. This was a lament on the death of a self-sacrificing blackbird and was shortly followed by similar poems on goldfinches and swallows. They were particularly praised by Dr. John Aikin in his “Essay on the application of Natural History to poetry”, who also noted that there were soon imitations among other minor poets, including Samuel Jackson Pratt’s “The Partridges, an elegy” (1771) and James Graeme’s “The Linnet” (1773). Jago’s most ambitious publication was the four-part topographical poem, Edge Hill, or the rural prospect delineated and moralised (1767). It was written in blank verse and was once described as “the most elaborate local poem in our language”. The poet takes his stance on the hill in the morning, facing south-west (book 1); at noon he is on Ratley Hill in the centre (books 2–3) and then moves along the ridge to look north-east at evening. The poem intermingles description with legendary, historical and antiquarian particulars, principally the battle at the start of the English Civil War. Imaginary excursions are made to Warwick, Coventry, Kenilworth, Solihull, and industrial Birmingham (under the name Bremicham), as well as many “flattering descriptions of all the great houses and seats of important people which come within his survey”. Local rivers are also included and even the nearby canal on which “sooty barks pursue their liquid track”. There are many digressions as well, including descriptions of industrial processes and of the nature of vision and the working of the telescope. The critic already quoted finds the poem “really interesting; with the scene before us, it is impossible not to admire the ingenuity and scrupulous thoroughness with which the author has performed his task,” although ultimately it is lacking in poetic execution. The Cambridge History of English and American Literature judges that "his catalogues have little picturesqueness or colour; while his verse, although it is not without the accent of local association, is typical, as a whole, of the decadence of the Miltonic method of natural description in the 18th century. Every group of trees is a grove, every country house a dome, and every hill a precipice". Particular examples of hackneyed diction include Latin-derived adjectives, as in “Honington’s irriguous meads”, or else 18th century circumlocutions such as “the woolly tribes” when sheep are meant. Nevertheless, the poem seems to have inspired the writing of the much shorter and simpler “Ode to Lansdowne Hill” (1785), which celebrates the site of another Civil War battle. In the following year Jago published “Labour and Genius, or the mill-stream and the cascade”, a humorous fable in octosyllabic verse written in memory of William Shenstone and his landscaped grounds at the Leasowes. Poems of lesser significance appeared here and there and Jago was working on a revised edition of his collected poems just before his death. This appeared posthumously as Poems, Moral and Descriptive in 1784. Included there was another homage to Milton in the oratorio “Adam, or the fatal disobedience, compiled from Milton’s Paradise Lost and adapted to music”. The rhymed choruses there were of Jago’s composition, but the main body of the work is adapted directly from Paradise Lost. Though it found no composer to set it, another of Jago’s pieces did. This was the “Roundelay for the Stratford Jubilee” organised by David Garrick in 1769, which was set for singing by Charles Dibdin. One other humorous piece also found an imitator. In Jago’s “Hamlet’s soliloquy imitated”, a minor poet agonises over whether “to print or not to print” and run the danger, by submitting his verses to Dodsley, to “lose the name of author”. A subsequent parody titled “The Presbyterian parson’s soliloquy” over the question to “conform or not conform” appeared in The Hibernian Magazine in 1774 and was often reprinted thereafter, ascribed to Samuel Badcock. One later commentator gave it as his opinion that “the hint of this parody was probably borrowed from Mr Jago’s”. Slight Jago’s output may have been, but it appears to have been influential in its time. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Jago

I am a romantic by very nature. I love passion and romance. I love traveling, cooking, playing scrabble, card games, writing poetry, playing bass guitar, and lead guitar. I love fishing. I love basketball and football go panthers lol. Love life and living. Love knowledge and wisdom. Forever seeking higher heights, and deeper depths...

I'm not scared of toasters, but it's ok if you are. Fearing things that can hurt you is natural. Unfortunately, I'm a sucker for huckleberry jam on toast, so I take that risk every day. I don't have forever, and life isn't always enjoyable, but have you TRIED huckleberry jam? It's hard to hate the world when you have that slightly chunky, gelatinous concentration on a piece of glutenous (or should I say gluttonous) bread.

Henri García Jaramillo Yarumal, Antioquia, Colombia, El universo. www.pagina-blanco.blogspot.com www.imagenesispoemas.blogspot.com www.henrigarciajaramillo.blogspot.com Yo soy 58 kilos de hueso, músculos (¿dije músculos?), vísceras y estiércol que a la falta de autoestima me resigné a este cuerpo y miento diciendo que soy feliz en esta piel. Por eso no me ven en las piscinas llamando la atención con mis enormes rodillas, mis enormes costillas y mi enorme... ansiedad de tenerlo grandecito. Soy un miedoso a la velocidad, la altura y las odontologías, por eso detesto montarme en una moto, montarme en un globo y montarme en una ortodoncia. Soy un comelón empedernido y entre mis platos preferidos están: el sancocho de tres telas, la tripaecallo, la chunchurria, el pescuezo de pollo, la arepa amarilla, los frisoles con coles, la trompa de marrano y la morcilla con arepa. Soy un solitario que a veces no quiere hablar con nadie, por eso me encierro días enteros en mi pieza consolándome con el monólogo del televisor, tratando de no odiar más el homo sapiens que tortura y mata. No me gusta estar en la semana fuera de mi lugar de trabajo, la escuela, los niños alientan mi alma. Yo soy un niño de 42 años que juega a existir. Soy un amante de la noche, de la poesía y del vino, de la música romántica, del rock de los ochenta y de la lluvia de media noche. Soy un soñador que cree que algún día habrá paz, que desaparecerán los partidos políticos, las corridas de toros, las galleras y el cáncer de próstata. Soy un enamorado de la vida y visto siempre de pantalón negro para no olvidar que esta termina y como no creo en el más allá, el negro me simboliza ausencia. Soy lo que como, lo que leo, lo que tomo, lo que siento, lo que vibro, lo que lloro, lo que río, lo que creo, lo que demuestro, lo que oculto, lo que temo, lo que hablo, lo que escribo en esa hoja de papel en blanco. Soy 58 kilos de vísceras, carne, hueso y estiércol, que deambula por esta insignificante porción del universo a medio día, con la linterna encendida buscando un verdadero ser humano. Yo que he sido un ermitaño de mi pieza, en la que me encierro para esconderme del mundo o de mi espejo, huraño por herencia, suicida del tiempo que me queda, he despreciado estar vivo, me duele respirar y anhelo mis cenizas. Por eso, ante el error, la culpa es la que hace el nudo de la horca. Yo he cometido muchas embarradas y ante todas he deseado no estar en este pellejo, pero de todas he salido avante, con la misma piel y me han enseñado a formar mi carácter, al precio de irme arrinconando en una esquina del tiempo. He cometido errores grises que han podido acabar con mi existencia y he sobrevivido gracias a la protección de los dioses. Los dioses aman a los genios y a los santos y se los llevan temprano. Necesitan de ellos su consejo. Yo, que soy ingenuo y nunca he dado ejemplo de religiosidad he demorado en dejar este universo. He cometido errores de tumba y aquí estoy sospechando hasta cuándo. Tal vez algún día me vuelva santo, o genio, o ambos, y la flaca me necesite para que le aconseje su próxima víctima en su parietal derecho. O tal vez no cometa ningún error, pero algún santo o algún genio me confunda y me nombre. Ese día quiero que me entierren con mi guitarra, un lápiz, una hoja de papel en blanco y una botella de vino, para escribir una canción al oscuro y tenebroso mundo de los vivos. Publicaciones • Esquina poética Periódico Sueño Norte (poemas varios). • Coautor del Manual para la convivencia familiar –SE DARTE-. Sin editar. Un libro pensado para el rescate de los valores familiares en aras de la disminución de la violencia intrafamiliar. • Coautor de la cartilla didáctica “Cuéntame una historia: José María Córdova”. Editorial Divegráficas. Medellín, 2004. Una biografía de este prócer de la independencia, pensada exclusivamente para el público infantil. • Coautor de la cartilla: “Leer y escribir EN GRANDE”. Litografía Clip Art. Yarumal, 2005. Diseño que hace parte de un programa de alfabetización de adultos en pro de la disminución del analfabetismo. • Columnista de los periódicos: Sueño Norte y El Antioqueño. Columna Página en blanco. www.pagina-blanco.blogspot.com • Autor del libro “Larva”. Teatro. Sin publicar. • Director de la Revista de poesía Alas de papel. www.alasdepapelrevista.blogspot.com • Memorias II Festival de poesía “Ánfora mágica”, 2008. • Memorias III Festival de poesía “Ánfora mágica”, 2009. • Memorias IV Festival de poesía “Ánfora mágica”, 2010. • Memorias II Festival de poesía y cuento corto “Son de palabras“, Donmatías, 2008. • Autor del libro de poesía “Imagenesis” (2010). • Autor del libro “Otra página en blanco”. Soluciones Impresas. Yarumal, 2013. • Autor del libro “De bolsillo”. Cuentos. Sin publicar. • Finalista en el I Concurso Mundial de Poetas por la Vida 2010 –ecopoesía-. Poema: “Vasos sanguíneos”. • Audio de poesía Imagenesis, “Literatura al aire”, 2010. Actividades • Maestro de escuela. • Miembro fundador del Taller de literatura “El sueño del pino”. Yarumal. • Director de la revista de poesía “Alas de papel”. • Navegante del universo. Capitán sin puerto en busca de los tesoros de la vida que escribe sus vivencias en la bitácora de un barco de papel.