Emma Lazarus (July 22, 1849– November 19, 1887) was an American poet born in New York City. She is best known for “The New Colossus”, a sonnet written in 1883; its lines appear inscribed on a bronze plaque in the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty installed in 1903, a decade and a half after Lazarus’s death. Lazarus was born into a large Sephardic-Ashkenazi Jewish family, the fourth of seven children of Moses Lazarus and Esther Nathan, The Lazarus family was from Germany, and the Nathan family was originally from Portugal and resident in New York long before the American Revolution.

(Belmonte, España, 1527–Madrigal de las Altas Torres, id., 1591) Escritor español en lenguas castellana y latina. De ascendencia judía, desde muy joven militó en la orden agustina. Estudió en las universidades de Alcalá de Henares y de Salamanca, donde obtuvo dos cátedras: la primera de filosofía moral y la segunda de Sagradas Escrituras, que abandonó más tarde para dedicarse a su orden. Fue detenido por la Inquisición y encarcelado durante casi cuatro años (1573-1576) a causa de su Comentario al Cantar de los Cantares (1561), traducción al castellano del texto bíblico, entonces prohibido.

Antonio Plaza Llamas (Apaseo1 Guanajuato, 2 de junio de 1830 — Ciudad de México, 26 de agosto de 1882), fue un militar, poeta y periodista mexicano. (Hasta hace poco tiempo se creyó que había nacido en la localidad del San Jose del Llano del actual municipio de Apaseo el Grande. El actual cronista de Apaseo el Alto, de apellido Francisco Sauza Vega insiste que este personaje nacio en San Bartolomé Aguascalientes, en el actual municipio de Apaseo El Alto. Aunque su acta de bautismo establece claramente que nació en la actual ciudad de Apaseo el Grande, en aquel momento denominada simplemente Apaseo) Orígenes, familia y muerte Sus padres fueron don José María Plaza y doña María de la Luz Llamas y Menéndez, matrimonio originario de la ciudad de Celaya. Se casó y tuvo tres hijos, a quienes amaba intensamente. Del único que se conoce su nombre fue el mayor, Edmundo —al cual le dedicó sentidísimos versos—, y que falleció en Yokohama, siendo Cónsul General en el imperio del Japón. El poeta murió en la ciudad de México a los 51 años. Sus funerales fueron modestos, siendo sepultado en el Panteón del Tepeyac (Villa de Guadalupe), publicándose en los periódicos artículos llenos de sentimiento y pesar por la desaparición de tan insigne pluma. Estudios y Carrera militar Fue enviado a la Ciudad de México; ahí ingresó en el Seminario Conciliar donde sólo se cursaban las carreras eclesiáticas y jurisprudencia. "El niño era precoz y liberal por instintos; así es que de aquellas aulas, de donde salieron Juan José Baz, Manuel Romero Rubio, Justino Fernández Mondoño, Manuel Fernando Soto y tantos otros patricios de renombre a defender la Constitución de 1857 y las Leyes de Reforma, él salió para alistarse como soldado en las filas progresistas y en ellas sirvió hasta el año de 1861 en que se retiró con licencia y con un pie inutilizado por una bala de cañón en pleno campo de batalla". En 1862, ya con el grado de teniente coronel, fue ingresado al Depósito de Jefes y Oficiales asistiendo a las campañas de Querétaro. Posteriormente, en 1867, llegó nuevamente a la Ciudad de México con el ejército, retirándose definitivamente de éste el año siguiente. El Periodista Sus ideales liberales y sus críticas, que encendían los corazones impulsando el movimiento revolucionario que modificó los destinos de la patria, fueron plasmados en los periódicos El Horóscopo, Los Padres del Agua Fría, La Idea, La Bandera Roja, La Luz de los Libres, El Constitucional, La Orquesta, La Pluma Roja, San Baltasar, y La Revista Mexicana, logrando la admiración de muchos... y el resentimiento de otros tantos. El Poeta No llegó a leer a los grandes maestros ni alimentar su estilo poético por una escuela en particular, "a semejanza de las aves, cantaba porque sentía la necesidad de cantar, sin importarle que la Gloria le diera sus lauros o el Olvido le envolviera en sus luctuosos crespones".3 Cantó a la miseria humana, a los vicios de la sociedad de su tiempo, a las pasiones; sus versos exponen situaciones vivenciales por la gran mayoría de sus lectores, de ahí que se hiciera tan popular. Juan de Dios Peza fue su amigo, a pesar de la diferencia de edades, y lo fue hasta su muerte, demostrándolo cuando dice al final del Prólogo al Ábum del Corazón: "¡Duerma en paz el poeta escéptico y adolorido! Yo, encuentro detrás de cada estrofa suya una lágrima y, como su amigo, la enjugo y la comprendo. Algunos de sus Poemas * La voz del inválido * Duerme, niño (a mi hijo Edmundo) * ¡Déjala! * Extravagancias * A una ramera * Amor de martir * A Rosa * Gota de hiel * Lágrimas y flores (a Virginia) * Lejos de ti * En el campo * Luz y sombras * Horas negras Sonetos * Yo * Un prodigio * Una verdad * Dolce far niente * Los héroes * A una jalapeña * A un ángel caído * A Inés Nataly En esta pagina se podrán encontrar algunas de sus obras: http://heron5.tripod.com/plaza.htm Referencias Wikipedia - http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antonio_Plaza

Andrew Lang (31 March 1844– 20 July 1912) was a Scottish poet, novelist, literary critic, and contributor to the field of anthropology. He is best known as a collector of folk and fairy tales. The Andrew Lang lectures at the University of St Andrews are named after him. Biography Lang was born in Selkirk. He was the eldest of the eight children born to John Lang, the town clerk of Selkirk, and his wife Jane Plenderleath Sellar, who was the daughter of Patrick Sellar, factor to the first duke of Sutherland. On 17 April 1875, he married Leonora Blanche Alleyne, youngest daughter of C. T. Alleyne of Clifton and Barbados. She was (or should have been) variously credited as author, collaborator, or translator of Lang’s Color/Rainbow Fairy Books which he edited. He was educated at Selkirk Grammar School, Loretto, and at the Edinburgh Academy, St Andrews University and at Balliol College, Oxford, where he took a first class in the final classical schools in 1868, becoming a fellow and subsequently honorary fellow of Merton College. He soon made a reputation as one of the most able and versatile writers of the day as a journalist, poet, critic, and historian. In 1906, he was elected FBA. He died of angina pectoris at the Tor-na-Coille Hotel in Banchory, Banchory, survived by his wife. He was buried in the cathedral precincts at St Andrews. Scholarship Folklore and anthropology Lang is now chiefly known for his publications on folklore, mythology, and religion. The interest in folklore was from early life; he read John Ferguson McLennan before coming to Oxford, and then was influenced by E. B. Tylor. The earliest of his publications is Custom and Myth (1884). In Myth, Ritual and Religion (1887) he explained the “irrational” elements of mythology as survivals from more primitive forms. Lang’s Making of Religion was heavily influenced by the 18th century idea of the “noble savage”: in it, he maintained the existence of high spiritual ideas among so-called “savage” races, drawing parallels with the contemporary interest in occult phenomena in England. His Blue Fairy Book (1889) was a beautifully produced and illustrated edition of fairy tales that has become a classic. This was followed by many other collections of fairy tales, collectively known as Andrew Lang’s Fairy Books. In the preface of the Lilac Fairy Book he credits his wife with translating and transcribing most of the stories in the collections. Lang examined the origins of totemism in Social Origins (1903). Psychical research Lang was one of the founders of “psychical research” and his other writings on anthropology include The Book of Dreams and Ghosts (1897), Magic and Religion (1901) and The Secret of the Totem (1905). He served as President of the Society for Psychical Research in 1911. Classical scholarship He collaborated with S. H. Butcher in a prose translation (1879) of Homer’s Odyssey, and with E. Myers and Walter Leaf in a prose version (1883) of the Iliad, both still noted for their archaic but attractive style. He was a Homeric scholar of conservative views. Other works include Homer and the Study of Greek found in Essays in Little (1891), Homer and the Epic (1893); a prose translation of The Homeric Hymns (1899), with literary and mythological essays in which he draws parallels between Greek myths and other mythologies; Homer and his Age (1906); and “Homer and Anthropology” (1908). Historian Lang’s writings on Scottish history are characterised by a scholarly care for detail, a piquant literary style, and a gift for disentangling complicated questions. The Mystery of Mary Stuart (1901) was a consideration of the fresh light thrown on Mary, Queen of Scots, by the Lennox manuscripts in the University Library, Cambridge, approving of her and criticising her accusers. He also wrote monographs on The Portraits and Jewels of Mary Stuart (1906) and James VI and the Gowrie Mystery (1902). The somewhat unfavourable view of John Knox presented in his book John Knox and the Reformation (1905) aroused considerable controversy. He gave new information about the continental career of the Young Pretender in Pickle the Spy (1897), an account of Alestair Ruadh MacDonnell, whom he identified with Pickle, a notorious Hanoverian spy. This was followed by The Companions of Pickle (1898) and a monograph on Prince Charles Edward (1900). In 1900 he began a History of Scotland from the Roman Occupation (1900). The Valet’s Tragedy (1903), which takes its title from an essay on Dumas’s Man in the Iron Mask, collects twelve papers on historical mysteries, and A Monk of Fife (1896) is a fictitious narrative purporting to be written by a young Scot in France in 1429–1431. Other writings Lang’s earliest publication was a volume of metrical experiments, The Ballads and Lyrics of Old France (1872), and this was followed at intervals by other volumes of dainty verse, Ballades in Blue China (1880, enlarged edition, 1888), Ballads and Verses Vain (1884), selected by Mr Austin Dobson; Rhymes à la Mode (1884), Grass of Parnassus (1888), Ban and Arrière Ban (1894), New Collected Rhymes (1905). Lang was active as a journalist in various ways, ranging from sparkling “leaders” for the Daily News to miscellaneous articles for the Morning Post, and for many years he was literary editor of Longman’s Magazine; no critic was in more request, whether for occasional articles and introductions to new editions or as editor of dainty reprints. He edited The Poems and Songs of Robert Burns (1896), and was responsible for the Life and Letters (1897) of JG Lockhart, and The Life, Letters and Diaries (1890) of Sir Stafford Northcote, 1st Earl of Iddesleigh. Lang discussed literary subjects with the same humour and acidity that marked his criticism of fellow folklorists, in Books and Bookmen (1886), Letters to Dead Authors (1886), Letters on Literature (1889), etc. Works To 1884 * St Leonards Magazine. 1863. This was a reprint of several articles that appeared in the St Leonards Magazine that Lang edited at St Andrews University. Includes the following Lang contributions: Pages 10–13, Dawgley Manor; A sentimental burlesque; Pages 25–26, Nugae Catulus; Pages 27–30, Popular Philosophies; pages 43–50 are ‘Papers by Eminent Contributors’, seven short parodies of which six are by Lang. * The Ballads and Lyrics of Old France (1872) * The Odyssey Of Homer Rendered Into English Prose (1879) translator with Samuel Henry Butcher * Aristotle’s Politics Books I. III. IV. (VII.). The Text of Bekker. With an English translation by W. E. Bolland. Together with short introductory essays by A. Lang To page 106 are Lang’s Essays, pp. 107–305 are the translation. Lang’s essays without the translated text were later published as The Politics of Aristotle. Introductory Essays. 1886. * The Folklore of France (1878) * Specimens of a Translation of Theocritus. 1879. This was an advance issue of extracts from Theocritus, Bion and Moschus rendered into English prose * XXII Ballades in Blue China (1880) * Oxford. Brief historical & descriptive notes (1880). The 1915 edition of this work was illustrated by painter George Francis Carline. * 'Theocritus Bion and Moschus. Rendered into English Prose with an Introductory Essay. 1880. * Notes by Mr A. Lang on a collection of pictures by Mr J. E.Millais R.A. exhibited at the Fine Arts Society Rooms. 148 New Bond Street. 1881. * The Library: with a chapter on modern illustrated books. 1881. * The Black Thief. A new and original drama (Adapted from the Irish) in four acts. (1882) * Helen of Troy, her life and translation. Done into rhyme from the Greek books. 1882. * The Most Pleasant and Delectable Tale of the Marriage of Cupid and Psyche (1882) with William Aldington * The Iliad of Homer, a prose translation (1883) with Walter Leaf and Ernest Myers * Custom and Myth (1884) * The Princess Nobody: A Tale of Fairyland (1884) * Ballads and Verses Vain (1884) selected by Austin Dobson * Rhymes à la Mode (1884) * Much Darker Days. By A. Huge Longway. (1884) * Household tales; their origin, diffusion, and relations to the higher myths. [1884]. Separate pre-publication issue of the “introduction” to Bohn’s edition of Grimm’s Household tales. 1885–1889 * That Very Mab (1885) with May Kendall * Books and Bookmen (1886) * Letters to Dead Authors (1886) * In the Wrong Paradise (1886) stories * The Mark of Cain (1886) novel * Lines on the inaugural meeting of the Shelley Society. Reprinted for private distribution from the Saturday Review of 13 March 1886 and edited by Thomas Wise (1886) * La Mythologie Traduit de L’Anglais par Léon Léon Parmentier. Avec une préface par Charles Michel et des Additions de l’auteur. (1886) Never published as a complete book in English, although there was a Polish translation. The first 170 pages is a translation of the article in the 'Encyclopædia Britannica’. The rest is a combination of articles and material from 'Custom and Myth’. * Almae matres (1887) * He (1887 with Walter Herries Pollock) parody * Aucassin and Nicolette (1887) * Myth, Ritual and Religion (2 vols., 1887) * Johnny Nut and the Golden Goose. Done into English from the French of Charles Deulin (1887) * Grass of Parnassus. Rhymes old and new. (1888) * Perrault’s Popular Tales (1888) * Gold of Fairnilee (1888) * Pictures at Play or Dialogues of the Galleries (1888) with W. E. Henley * Prince Prigio (1889) * The Blue Fairy Book (1889) (illustrations by Henry J. Ford) * Letters on Literature (1889) * Lost Leaders (1889) * Ode to Golf. Contribution to On the Links; being Golfing Stories by various hands (1889) * The Dead Leman and other tales from the French (1889) translator with Paul Sylvester 1890–1899 * The Red Fairy Book (1890) * The World’s Desire (1890) with H. Rider Haggard * Old Friends: Essays in Epistolary Parody (1890) * The Strife of Love in a Dream, Being the Elizabethan Version of the First Book of the Hypnerotomachia of Francesco Colonna (1890) * The Life, Letters and Diaries of Sir Stafford Northcote, 1st Earl of Iddesleigh (1890) * Etudes traditionnistes (1890) * How to Fail in Literature (1890) * The Blue Poetry Book (1891) * Essays in Little (1891) * On Calais Sands (1891) * The Green Fairy Book (1892) * The Library with a Chapter on Modern English Illustrated Books (1892) with Austin Dobson * William Young Sellar (1892) * The True Story Book (1893) * Homer and the Epic (1893) * Prince Ricardo of Pantouflia (1893) * Waverley Novels (by Walter Scott), 48 volumes (1893) editor * St. Andrews (1893) * Montezuma’s Daughter (1893) with H. Rider Haggard * Kirk’s Secret Commonwealth (1893) * The Tercentenary of Izaak Walton (1893) * The Yellow Fairy Book (1894) * Ban and Arrière Ban (1894) * Cock Lane and Common-Sense (1894) * Memoir of R. F. Murray (1894) * The Red True Story Book (1895) * My Own Fairy Book (1895) * Angling Sketches (1895) * A Monk of Fife (1895) * The Voices of Jeanne D’Arc (1895) * The Animal Story Book (1896) * The Poems and Songs of Robert Burns (1896) editor * The Life and Letters of John Gibson Lockhart (1896) two volumes * Pickle the Spy; or the Incognito of Charles, (1897) * The Nursery Rhyme Book (1897) * The Miracles of Madame Saint Katherine of Fierbois (1897) translator * The Pink Fairy Book (1897) * A Book of Dreams and Ghosts (1897) * Pickle the Spy (1897) * Modern Mythology (1897) * The Companions of Pickle (1898) * The Arabian Nights Entertainments (1898) * The Making of Religion (1898) * Selections from Coleridge (1898) * Waiting on the Glesca Train (1898) * The Red Book of Animal Stories (1899) * Parson Kelly (1899) Co-written with A. E. W. Mason * The Homeric Hymns (1899) translator * The Works of Charles Dickens in Thirty-four Volumes (1899) editor 1900–1909 * The Grey Fairy Book (1900) * Prince Charles Edward (1900) * Parson Kelly (1900) * The Poems and Ballads of Sir Walter Scott, Bart (1900) editor * A History of Scotland– From the Roman Occupation (1900–1907) four volumes * Notes and Names in Books (1900) * Alfred Tennyson (1901) * Magic and Religion (1901) * Adventures Among Books (1901) * The Crimson Fairy Book (1903) * The Mystery of Mary Stuart (1901, new and revised ed., 1904) * The Book of Romance (1902) * The Disentanglers (1902) * James VI and the Gowrie Mystery (1902) * Notre-Dame of Paris (1902) translator * The Young Ruthvens (1902) * The Gowrie Conspiracy: the Confessions of Sprott (1902) editor * The Violet Fairy Book (1901) * Lyrics (1903) * Social England Illustrated (1903) editor * The Story of the Golden Fleece (1903) * The Valet’s Tragedy (1903) * Social Origins (1903) with Primal Law by James Jasper Atkinson * The Snowman and Other Fairy Stories (1903) * Stella Fregelius: A Tale of Three Destinies (1903) with H. Rider Haggard * The Brown Fairy Book (1904) * Historical Mysteries (1904) * The Secret of the Totem (1905) * New Collected Rhymes (1905) * John Knox and the Reformation (1905) * The Puzzle of Dickens’s Last Plot (1905) * The Clyde Mystery. A Study in Forgeries and Folklore (1905) * Adventures among Books (1905) * Homer and His Age (1906) * The Red Romance Book (1906) * The Orange Fairy Book (1906) * The Portraits and Jewels of Mary Stuart (1906) * Life of Sir Walter Scott (1906) * The Story of Joan of Arc (1906) * New and Old Letters to Dead Authors (1906) * Tales of a Fairy Court (1907) * The Olive Fairy Book (1907) * Poets’ Country (1907) editor, with Churton Collins, W. J. Loftie, E. Hartley Coleridge, Michael Macmillan * The King over the Water (1907) * Tales of Troy and Greece (1907) * The Origins of Religion (1908) essays * The Book of Princes and Princesses (1908) * Origins of Terms of Human Relationships (1908) * Select Poems of Jean Ingelow (1908) editor * The Maid of France (1908) * Three Poets of French Bohemia (1908) * The Red Book of Heroes (1909) * The Marvellous Musician and Other Stories (1909) * Sir George Mackenzie King’s Advocate, of Rosehaugh, His Life and Times (1909) 1910–1912 * The Lilac Fairy Book (1910) * Does Ridicule Kill? (1910) * Sir Walter Scott and the Border Minstrelsy (1910) * The World of Homer (1910) * The All Sorts of Stories Book (1911) * Ballades and Rhymes (1911) * Method in the Study of Totemism (1911) * The Book of Saints and Heroes (1912) * Shakespeare, Bacon and the Great Unknown (1912) * A History of English Literature (1912) * In Praise of Frugality (1912) * Ode on a Distant Memory of Jane Eyre (1912) * Ode to the Opening Century (1912) Posthumous * Highways and Byways in The Border (1913) with John Lang * The Strange Story Book (1913) with Mrs. Lang * The Poetical Works (1923) edited by Mrs. Lang, four volumes * Old Friends Among the Fairies: Puss in Boots and Other Stories. Chosen from the Fairy Books (1926) * Tartan Tales From Andrew Lang (1928) edited by Bertha L. Gunterman * From Omar Khayyam (1935) Andrew Lang’s Fairy Books * The Blue Fairy Book (1889) * The Red Fairy Book (1890) * The Green Fairy Book (1892) * The Yellow Fairy Book (1894) * The Pink Fairy Book (1897) * The Grey Fairy Book (1900) * The Violet Fairy Book (1901) * The Crimson Fairy Book (1903) * The Brown Fairy Book (1904) * The Orange Fairy Book (1906) * The Olive Fairy Book (1907) * The Lilac Fairy Book (1910) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrew_Lang

Soy una chica joven, amante de la poesía desde que me alcanza la memoria. Disfruto viendo las horas pasar entre los más bellos poemas de grandes autores, y de algunos otros que pronto lo serán. Me gusta definir la poesía como "aquella porción del corazón del poeta que puede llegar a rozar el tuyo propio". Autores como Miguel Hernández, José de Esproncedea, F. G. Lorca, Rafael Alberti, Antonio Machado, J. L. Borges o José Ángel Buesa consiguieron un día abrir mi corazón al hermoso mundo de la poesía, refugio de serenidad en un mundo estrafalario.

Rosanna Eleanor Leprohon (January 12, 1829– September 20, 1879), born Rosanna Eleanor Mullins, was a Canadian writer and poet. She was “one of the first English-Canadian writers to depict French Canada in a way that earned the praise of, and resulted in her novels being read by, both anglophone and francophone Canadians.”

Li-Young Lee (李立揚, pinyin: Lǐ Lìyáng) (born August 19, 1957) is an American poet. He was born in Jakarta, Indonesia, to Chinese parents. His maternal great-grandfather was Yuan Shikai, China’s first Republican President, who attempted to make himself emperor. Lee’s father, who was a personal physician to Mao Zedong while in China, relocated his family to Indonesia, where he helped found Gamaliel University. His father was exiled and spent 19 months in an Indonesian prison camp in Macau. In 1959 the Lee family fled the country to escape anti-Chinese sentiment and after a five-year trek through Hong Kong and Japan, they settled in the United States in 1964. Li-Young Lee attended the University of Pittsburgh and the University of Arizona, and the State University of New York at Brockport. Development as a poet Lee attended the University of Pittsburgh, where he began to develop his love for writing. He had seen his father find his passion for ministry and as a result of his father reading to him and encouraging Lee to find his passion, Lee began to dive into the art of language. Lee’s writing has also been influenced by classic Chinese poets, such as Li Bai and Du Fu. Many of Lee’s poems are filled with themes of simplicity, strength, and silence. All are strongly influenced by his family history, childhood, and individuality. He writes with simplicity and passion which creates images that take the reader deeper and also requires his audience to fill in the gaps with their own imagination. These feelings of exile and boldness to rebel take shape as they provide common themes for poems. Lee’s influence on Asian American poetry Li-Young Lee has been an established Asian American poet who has been doing interviews for the past twenty years. Breaking the Alabaster Jar: Conversations with Li-Young Lee (BOA Editions, 2006, ed. Earl G. Ingersoll), is the first edited and published collection of interviews with an Asian American poet. In this book, Earl G. Ingersoll has collected interviews with the poet consisting of “conversational” questions meant to bring out Lee’s views on Asian American poetry, writing, and identity. Awards and honors * Lee has won numerous poetry awards: * 1986: Delmore Schwartz Memorial Award, from New York University, for Rose * 1988: Whiting Award * 1990: Lamont Poetry Selection for The City in Which I Love You * 1995: Lannan Literary Award * 1995: American Book Award, from the Before Columbus Foundation, for The Wingéd Seed: A Remembrance * 2002: William Carlos Williams Award for Book of My Nights (American Poets Continuum) Judge: Carolyn Kizer * 2003: Fellowship of the Academy of American Poets, which does not accept applications and which includes a $25,000 stipend * Fellowship, National Endowment for the Arts * Fellowship, John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation * Grant, Illinois Arts Council * Grant, Commonwealth of Pennsylvania * Grant, Pennsylvania Council on the Arts Other recognition * 2011: Lee’s poem ″A Story″ was featured in the AP English Literature and Composition 2011 Free-Response Questions. Selected bibliography Poetry * * 1986: Rose. Rochester: BOA Editions Limited, ISBN 0-918526-53-1 * 1990: The City In Which I Love You. Rochester: BOA Editions Limited, ISBN 0-918526-83-3 * 2001: Book of My Nights. Rochester: BOA Editions Limited, ISBN 1-929918-08-9 * 2008: Behind My Eyes. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., ISBN 0-393-33481-3 Memoir * * The Wingéd Seed: A Remembrance. (hardcover) New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995. ASIN: B000NGRB2G (paperback) St. Paul: Ruminator, 1999. ISBN 1-886913-28-5 References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Li-Young_Lee

Sidney Clopton Lanier (February 3, 1842– September 7, 1881) was an American musician, poet and author. He served in the Confederate army, worked on a blockade running ship for which he was imprisoned (resulting in his catching tuberculosis), taught, worked at a hotel where he gave musical performances, was a church organist, and worked as a lawyer. As a poet he used dialects. He became a flautist and sold poems to publications. He eventually became a university professor and is known for his adaptation of musical meter to poetry. Many schools, other structures and two lakes are named for him. Biography Sidney Clopton Lanier was born February 3, 1842, in Macon, Georgia, to parents Robert Sampson Lanier and Mary Jane Anderson; he was mostly of English ancestry. His distant French Huguenot ancestors immigrated to England in the 16th century, fleeing religious persecution. He began playing the flute at an early age, and his love of that musical instrument continued throughout his life. He attended Oglethorpe University, which at the time was near Milledgeville, Georgia, and he was a member of the Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity. He graduated first in his class shortly before the outbreak of the American Civil War. He fought in the American Civil War (1861–65), primarily in the tidewater region of Virginia, where he served in the Confederate signal corps. Later, he and his brother Clifford served as pilots aboard English blockade runners. On one of these voyages, his ship was boarded. Refusing to take the advice of the British officers on board to don one of their uniforms and pretend to be one of them, he was captured. He was incarcerated in a military prison at Point Lookout in Maryland, where he contracted tuberculosis (generally known as “consumption” at the time). He suffered greatly from this disease, then incurable and usually fatal, for the rest of his life. Shortly after the war, he taught school briefly, then moved to Montgomery, Alabama, where he worked as a desk clerk at The Exchange Hotel and also performed as a musician. He was the regular organist at The First Presbyterian Church in nearby Prattville. He wrote his only novel, Tiger Lilies (1867) while in Alabama. This novel was partly autobiographical, describing a stay in 1860 at his grandfather’s Montvale Springs resort hotel near Knoxville, Tennessee. In 1867, he moved to Prattville, at that time a small town just north of Montgomery, where he taught and served as principal of a school. He married Mary Day of Macon in 1867 and moved back to his hometown, where he began working in his father’s law office. After taking and passing the Georgia bar, Lanier practiced as a lawyer for several years. During this period he wrote a number of poems, using the “cracker” and “negro” dialects of his day, about poor white and black farmers in the Reconstruction South. He traveled extensively through southern and eastern portions of the United States in search of a cure for his tuberculosis. While on one such journey in Texas, he rediscovered his native and untutored talent for the flute and decided to travel to the northeast in hopes of finding employment as a musician in an orchestra. Unable to find work in New York City, Philadelphia, or Boston, he signed on to play flute for the Peabody Orchestra in Baltimore, Maryland, shortly after its organization. He taught himself musical notation and quickly rose to the position of first flautist. He was famous in his day for his performances of a personal composition for the flute called “Black Birds”, which mimics the song of that species. In an effort to support Mary and their three sons, he also wrote poetry for magazines. His most famous poems were “Corn” (1875), “The Symphony” (1875), “Centennial Meditation” (1876), “The Song of the Chattahoochee” (1877), “The Marshes of Glynn”, (1878) and “Sunrise” (1881). The latter two poems are generally considered his greatest works. They are part of an unfinished set of lyrical nature poems known as the “Hymns of the Marshes”, which describe the vast, open salt marshes of Glynn County on the coast of Georgia. (The longest bridge in Georgia is in Glynn County and is named for Lanier.) Later life Late in his life, he became a student, lecturer, and, finally, a faculty member at the Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, specializing in the works of the English novelists, Shakespeare, the Elizabethan sonneteers, Chaucer, and the Old English poets. He published a series of lectures entitled The English Novel (published posthumously in 1883) and a book entitled The Science of English Verse (1880), in which he developed a novel theory exploring the connections between musical notation and meter in poetry. Lanier finally succumbed to complications caused by his tuberculosis on September 7, 1881, while convalescing with his family near Lynn, North Carolina. He was 39. Lanier is buried in Green Mount Cemetery in Baltimore. Writing style and literary theory With his theory connecting musical notation with poetic meter, and also being described as a deft metrical technical, in his own words ‘daring with his poem ’Special Pleading’ to give myself such freedom as I desired, in my own style’ and also by developing a unique style of poetry written in logaoedic dactyls, which was strongly influenced by the works of his beloved Anglo-Saxon poets. He wrote several of his greatest poems in this meter, including “Revenge of Hamish” (1878), “The Marshes of Glynn” and “Sunrise”. In Lanier’s hands, the logaoedic dactylic meter led to a free-form, almost prose-like style of poetry that was greatly admired by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Bayard Taylor, Charlotte Cushman, and other leading poets and critics of the day. A similar poetical meter was independently developed by Gerard Manley Hopkins at about the same time (there is no evidence that they knew each other or that either of them had read any of the other’s works). Lanier also published essays on other literary and musical topics and a notable series of four redactions of literary works about knightly combat and chivalry in modernized language more appealing to the boys of his day: The Boy’s Froissart (1878), a retelling of Jean Froissart’s Froissart’s Chronicles, which tell of adventure, battle and custom in medieval England, France and Spain The Boy’s King Arthur (1880), based on Sir Thomas Malory’s compilation of the legends of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table The Boy’s Mabinogion (1881), based on the early Welsh legends of King Arthur, as retold in the Red Book of Hergest. The Boy’s Percy (published posthumously in 1882), consisting of old ballads of war, adventure and love based on Bishop Thomas Percy’s Reliques of Ancient English Poetry. He also wrote two travelogues that were widely read at the time, entitled Florida: Its Scenery, Climate and History (1875) and Sketches of India (1876) (although he never visited India). Legacy and honors The Sidney Lanier Cottage in Macon, Georgia is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The square, stone Monument to Poets of Georgia, located between 7th & 8th St. in Augusta, lists Lanier as one of Georgia’s four great poets, all of whom saw Confederate service. The southeastern side bears this inscription: "To Sidney Lanier 1842–1880. The catholic man who hath nightly won God out of knowledge and good out of infinite pain and sight out of Blindness and Purity out of stain." The other poets on the monument are James Ryder Randall, Fr. Abram Ryan, and Paul Hayne. Baltimore honored Lanier with a large and elaborate bronze and granite sculptural monument, created by Hans K. Schuler and located on the campus of the Johns Hopkins University. In addition to the monument at Johns Hopkins, Lanier was also later memorialized on the campus of Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. Upon the construction of the iconic Duke Chapel between 1930 and 1935 on the university’s West Campus, a statue of Lanier was included alongside two fellow prominent Southerners, Thomas Jefferson and Robert E. Lee. This statue, which appears to show a Lanier older than the 39 years he actually lived, is situated on the right side of the portico leading into the Chapel narthex. It is prominently featured on the cover of the 2010 autobiographical memoir Hannah’s Child, by Stanley Hauerwas, a Methodist theologian teaching at Duke Divinity School. Lanier’s poem “The Marshes of Glynn” is the inspiration for a cantata by the same name that was created by the modern English composer Andrew Downes to celebrate the Royal Opening of the Adrian Boult Hall in Birmingham, England, in 1986. Piers Anthony used Lanier, his life, and his poetry in his science-fiction novel Macroscope (1969). He quotes from “The Marshes of Glynn” and other references appear throughout the novel. Several entities have been named for Sidney Lanier: Inhabited places Lanier Heights Neighborhood, Washington, D.C. Lanier County, Georgia Indirectly, USS Lanier, which was named for the county. Bodies of water Lake Lanier, operated by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers northeast of Atlanta, Georgia (The lake was created by the damming of the Chattahoochee River, a river that was the subject of one of Lanier’s poems.) Lake Lanier in Tryon, North Carolina Schools Sidney Lanier High School in Montgomery, Alabama Sidney Lanier School in Gainesville, Florida Lanier University short-lived university, first Baptist, then owned by the Ku Klux Klan, in Atlanta, Georgia The Sidney Lanier Building (previously Sidney Lanier Elementary School) on the campus of Glynn Academy, in Brunswick, Georgia Lanier Middle School in Buford, Georgia Lanier Elementary School in Gainesville, Georgia Sidney Lanier Elementary School in Tulsa, Oklahoma Sidney Lanier High School in Austin, Texas Sidney Lanier Expressive Arts Vanguard Elementary School in Dallas, Texas Lanier Middle School in Houston, Texas Lanier High School in San Antonio, Texas Lanier Middle School in Fairfax, Virginia Sidney Lanier Elementary School in Tampa, Florida Lanier Technical College in Oakwood, Georgia Other Sidney Lanier Cottage, the birthplace of Lanier, in Macon, Georgia Sidney Lanier Bridge over the South Brunswick River in Brunswick, Georgia Lanier’s Oak in Brunswick, Georgia The Lanier Library, Tryon, North Carolina. Lanier’s widow, Mary, donated two of his volumes of poetry to begin the collection when the library was established in 1890. Sidney Lanier Camp, Eliot, Maine. Sidney Lanier Boulevard in Duluth, GA References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sidney_Lanier

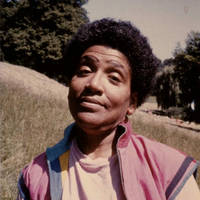

Audre Lorde (/ˈɔːdri lɔːrd/; born Audrey Geraldine Lorde, February 18, 1934– November 17, 1992) was an African American writer, feminist, womanist, lesbian, and civil rights activist. As a poet, she is best known for technical mastery and emotional expression, particularly in her poems expressing anger and outrage at civil and social injustices she observed throughout her life. Her poems and prose largely dealt with issues related to civil rights, feminism, and the exploration of black female identity. In relation to non-intersectional feminism in the United States, Lorde famously said, “Those of us who stand outside the circle of this society’s definition of acceptable women; those of us who have been forged in the crucibles of difference—those of us who are poor, who are lesbians, who are Black, who are older—know that survival is not an academic skill. It is learning how to take our differences and make them strengths. For the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change. And this fact is only threatening to those women who still define the master’s house as their only source of support.” Life and work Lorde was born in New York City to Caribbean immigrants from Barbados and Carriacou, Frederick Byron Lorde (called Byron) and Linda Gertrude Belmar Lorde, who settled in Harlem. Lorde’s mother was of mixed ancestry but could pass for white, a source of pride for her family. Lorde’s father was darker than the Belmar family liked, and they only allowed the couple to marry because of Byron Lorde’s charm, ambition, and persistence. Nearsighted to the point of being legally blind, and the youngest of three daughters (two older sisters, Phyllis and Helen), Audre Lorde grew up hearing her mother’s stories about the West Indies. She learned to talk while she learned to read, at the age of four, and her mother taught her to write at around the same time. She wrote her first poem when she was in eighth grade. Born Audrey Geraldine Lorde, she chose to drop the “y” from her first name while still a child, explaining in Zami: A New Spelling of My Name that she was more interested in the artistic symmetry of the “e”-endings in the two side-by-side names “Audre Lorde” than in spelling her name the way her parents had intended. Lorde’s relationship with her parents was difficult from a young age. She was able to spend very little time with her father and mother, who were busy maintaining their real estate business in the tumultuous economy after the Great Depression, and when she did see them, they were often cold or emotionally distant. In particular, Lorde’s relationship with her mother, who was deeply suspicious of people with darker skin than hers (which Lorde’s was) and the outside world in general, was characterized by “tough love” and strict adherence to family rules. Lorde’s difficult relationship with her mother would figure prominently in later poems, such as Coal’s “Story Books on a Kitchen Table.” As a child, Lorde, who struggled with communication, came to appreciate the power of poetry as a form of expression. She memorized a great deal of poetry, and would use it to communicate, to the extent that, “If asked how she was feeling, Audre would reply by reciting a poem.” Around the age of twelve, she began writing her own poetry and connecting with others at her school who were considered “outcasts” as she felt she was. She attended Hunter College High School, a secondary school for intellectually gifted students, and graduated in 1951. In 1954, she spent a pivotal year as a student at the National University of Mexico, a period she described as a time of affirmation and renewal, during which she confirmed her identity on personal and artistic levels as a lesbian and poet. On her return to New York, she attended Hunter College, graduating class of 1959. There, she worked as a librarian, continued writing and became an active participant in the gay culture of Greenwich Village. She furthered her education at Columbia University, earning a master’s degree in Library Science in 1961. She also worked during this time as a librarian at Mount Vernon Public Library and married attorney Edwin Rollins; they divorced in 1970 after having two children, Elizabeth and Jonathan. In 1966, Lorde became head librarian at Town School Library in New York City, where she remained until 1968. In 1968 Lorde was writer-in-residence at Tougaloo College in Mississippi, where she met Frances Clayton, a white professor of psychology, who was to be her romantic partner until 1989. Lorde’s time at Tougaloo College, like her year at the National University of Mexico, was a formative experience for Lorde as an artist. She led workshops with her young, black undergraduate students, many of whom were eager to discuss the civil rights issues of that time. Through her interactions with her students, she reaffirmed her desire not only to live out her “crazy and queer” identity, but devoted new attention to the formal aspects of her craft as a poet. Her book of poems Cables to Rage came out of her time and experiences at Tougaloo. From 1977 to 1978 Lorde had a brief affair with the sculptor and painter Mildred Thompson. The two met in Nigeria in 1977 at the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture (FESTAC 77). Their affair ran its course during the time that Thompson lived in Washington, D.C. The Berlin Years In 1984 Audre Lorde started a visiting professorship in Berlin Germany at the Free University of Berlin. She was invited by Dagmar Schultz who met her at the UN “World Women’s Conference” in Copenhagen in 1980. While Lorde was in Germany she made a significant impact on the women there and was a big part of the start of the Afro-German movement. The term Afro-German was created by Lorde and some Black German women as a nod to African-American. During her many trips to Germany, she touched many women’s lives including May Ayim, Ika Hugel-Marshell, and Hegal Emde. All of these women decided to start writing after they met Audre Lorde. She encouraged the women of Germany to speak up and have a voice. Instead of fighting through violence, Lorde thought that language was a powerful form of resistance. Her impact on Germany reached more than just Afro-German women. Many white women and men found Lorde’s work to be very beneficial to their own lives. They started to put their privilege and power into question and became more conscious. Because of her impact on the Afro-German movement, Dagmar Schultz put together a documentary to highlight the chapter of her life that was not known to many. Audre Lorde - The Berlin Years was accepted by the Berlinale in 2012 and from then was showed at many different film festivals around the world and received five awards. The film showed the lack of recognition that Lorde received for her contributions towards the theories of intersectionality. Last years Audre Lorde battled cancer for fourteen years. She was first diagnosed with breast cancer in 1978 and underwent a mastectomy. Six years later, she was diagnosed with liver cancer. After her diagnosis, she chose to become more focused on both her life and her writing. She wrote The Cancer Journals, which won the American Library Association Gay Caucus Book of the Year Award in 1981. She featured as the subject of a documentary called A Litany for Survival: The Life and Work of Audre Lorde, which shows her as an author, poet, human rights activist, feminist, lesbian, a teacher, a survivor, and a crusader against bigotry. She is quoted in the film as saying: “What I leave behind has a life of its own. I’ve said this about poetry; I’ve said it about children. Well, in a sense I’m saying it about the very artifact of who I have been.” From 1991 until her death, she was the New York State Poet Laureate. In 1992, she received the Bill Whitehead Award for Lifetime Achievement from Publishing Triangle. In 2001, Publishing Triangle instituted the Audre Lorde Award to honour works of lesbian poetry. Lorde died of liver cancer on November 17, 1992, in St. Croix, where she had been living with Gloria I. Joseph. She was 58. In an African naming ceremony before her death, she took the name Gamba Adisa, which means “Warrior: She Who Makes Her Meaning Known”. Work Poetry Lorde focused her discussion of difference not only on differences between groups of women but between conflicting differences within the individual. “I am defined as other in every group I’m part of,” she declared. “The outsider, both strength and weakness. Yet without community there is certainly no liberation, no future, only the most vulnerable and temporary armistice between me and my oppression”. She described herself both as a part of a “continuum of women” and a “concert of voices” within herself. Her conception of her many layers of selfhood is replicated in the multi-genres of her work. Critic Carmen Birkle wrote: “Her multicultural self is thus reflected in a multicultural text, in multi-genres, in which the individual cultures are no longer separate and autonomous entities but melt into a larger whole without losing their individual importance.” Her refusal to be placed in a particular category, whether social or literary, was characteristic of her determination to come across as an individual rather than a stereotype. Lorde considered herself a “lesbian, mother, warrior, poet” and used poetry to get this message across. Lorde’s poetry was published very regularly during the 1960s—in Langston Hughes’ 1962 New Negro Poets, USA; in several foreign anthologies; and in black literary magazines. During this time, she was also politically active in civil rights, anti-war, and feminist movements. In 1968, Lorde published The First Cities, her first volume of poems. It was edited by Diane di Prima, a former classmate and friend from Hunter College High School. The First Cities has been described as a “quiet, introspective book,” and Dudley Randall, a poet and critic, asserted in his review of the book that Lorde “does not wave a black flag, but her blackness is there, implicit, in the bone”. Her second volume, Cables to Rage (1970), which was mainly written during her tenure as poet-in-residence at Tougaloo College in Mississippi, addressed themes of love, betrayal, childbirth, and the complexities of raising children. It is particularly noteworthy for the poem “Martha,” in which Lorde openly confirms her homosexuality for the first time in her writing: "[W]e shall love each other here if ever at all.” Nominated for the National Book Award for poetry in 1973, From a Land Where Other People Live (Broadside Press) shows Lorde’s personal struggles with identity and anger at social injustice. The volume deals with themes of anger, loneliness, and injustice, as well as what it means to be an African-American woman, mother, friend, and lover. 1974 saw the release of New York Head Shop and Museum, which gives a picture of Lorde’s New York through the lenses of both the civil rights movement and her own restricted childhood: stricken with poverty and neglect and, in Lorde’s opinion, in need of political action. Despite the success of these volumes, it was the release of Coal in 1976 that established Lorde as an influential voice in the Black Arts Movement (Norton), as well as introducing her to a wider audience. The volume includes poems from both The First Cities and Cables to Rage, and it unties many of the themes Lorde would become known for throughout her career: her rage at racial injustice, her celebration of her black identity, and her call for an intersectional consideration of women’s experiences. Lorde followed Coal up with Between Our Selves (also in 1976) and Hanging Fire (1978). In Lorde’s volume The Black Unicorn (1978), she describes her identity within the mythos of African female deities of creation, fertility, and warrior strength. This reclamation of African female identity both builds and challenges existing Black Arts ideas about pan-Africanism. While writers like Amiri Baraka and Ishmael Reed utilized African cosmology in a way that “furnished a repertoire of bold male gods capable of forging and defending an aboriginal black universe,” in Lorde’s writing “that warrior ethos is transferred to a female vanguard capable equally of force and fertility.” Lorde’s poetry became more open and personal as she grew older and became more confident in her sexuality. In Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches, Lorde states, "Poetry is the way we help give name to the nameless so it can be thought…As they become known to and accepted by us, our feelings and the honest exploration of them become sanctuaries and spawning grounds for the most radical and daring ideas." Sister Outsider also elaborates Lorde’s challenge to European-American traditions. Prose The Cancer Journals (1980), derived in part from personal journals written in the late seventies, and A Burst of Light (1988) both use non-fiction prose to preserve, explore, and reflect on Lorde’s diagnosis, treatment, and recovery from breast cancer. In both works, Lorde deals with Western notions of illness, treatment, and physical beauty and prosthesis, as well as themes of death, fear of mortality, victimization versus survival, and inner power. Lorde’s deeply personal novel Zami: A New Spelling of My Name (1982), described as a “biomythography,” chronicles her childhood and adulthood. The narrative deals with the evolution of Lorde’s sexuality and self-awareness. In Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (1984), Lorde asserts the necessity of communicating the experience of marginalized groups in order to make their struggles visible in a repressive society. She emphasizes the need for different groups of people (particularly white women and African-American women) to find common ground in their lived experience. One of her works in Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches is “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House.” Lorde questions the scope and ability for change to be instigated when examining problems through a racist, patriarchal lens. She insists that women see differences between other women not as something to be tolerated, but something that is necessary to generate power and to actively “be” in the world. This will create a community that embraces differences, which will ultimately lead to liberation. Lorde elucidates, “Divide and conquer, in our world, must become define and empower." Also, one must educate themselves about the oppression of others because expecting a marginalized group to educate the oppressors is the continuation of racist, patriarchal thought. She explains that this is a major tool utilized by oppressors to keep the oppressed occupied with the master’s concerns. She concludes that in order to bring about real change, we cannot work within the racist, patriarchal framework because change brought about in that will not remain. Another work in Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches is “The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action.*” Lorde discusses the importance of speaking, even when afraid because one’s silence will not protect them from being marginalized and oppressed. Many people fear to speak the truth because of how it may cause pain, however, one ought to put fear into perspective when deliberating whether to speak or not. Lorde emphasizes that “the transformation of silence into language and action is a self-revelation, and that always seems fraught with danger." People are afraid of others’ reactions for speaking, but mostly for demanding visibility, which is essential to live. Lorde adds, “We can sit in our corners mute forever while our sisters and ourselves are wasted, while our children are distorted and destroyed, while our earth is poisoned; we can sit in our safe corners mute as bottles, and we will still be no less afraid." People are taught to respect their fear of speaking more than silence, but ultimately, the silence will choke us anyway, so we might as well speak the truth. In 1980, together with Barbara Smith and Cherríe Moraga, she co-founded Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, the first U.S. publisher for women of color. Lorde was State Poet of New York from 1991 to 1992. Theory Her writings are based on the “theory of difference,” the idea that the binary opposition between men and women is overly simplistic; although feminists have found it necessary to present the illusion of a solid, unified whole, the category of women itself is full of subdivisions. Lorde identified issues of class, race, age, gender, and even health– this last was added as she battled cancer in her later years– as being fundamental to the female experience. She argued that, although differences in gender have received all the focus, it is essential that these other differences are also recognized and addressed. “Lorde,” writes the critic Carmen Birkle, “puts her emphasis on the authenticity of experience. She wants her difference acknowledged but not judged; she does not want to be subsumed into the one general category of ‘woman.’” This theory is today known as intersectionality. While acknowledging that the differences between women are wide and varied, most of Lorde’s works are concerned with two subsets that concerned her primarily—race and sexuality. In Ada Gay Griffin and Michelle Parkerson’s documentary A Litany for Survival: The Life and Work of Audre Lorde, Lorde says, "Let me tell you first about what it was like being a Black woman poet in the ‘60s, from jump. It meant being invisible. It meant being really invisible. It meant being doubly invisible as a Black feminist woman and it meant being triply invisible as a Black lesbian and feminist". In her essay “The Erotic as Power,” written in 1978 and collected in Sister Outsider, Lorde theorizes the Erotic as a site of power for women only when they learn to release it from its suppression and embrace it. She proposes that the Erotic needs to be explored and experienced wholeheartedly, because it exists not only in reference to sexuality and the sexual, but also as a feeling of enjoyment, love, and thrill that is felt towards any task or experience that satisfies women in their lives, be it reading a book or loving one’s job. She dismisses “the false belief that only by the suppression of the erotic within our lives and consciousness can women be truly strong. But that strength is illusory, for it is fashioned within the context of male models of power.” She explains how patriarchal society has misnamed it used it against women, causing women to fear it. Women also fear it because the erotic is powerful and a deep feeling. Women must share each others’ power rather than use it without consent, which is abuse. They should do it as a method to connect everyone in their differences and similarities. Utilizing, the erotic as power allows women to use their knowledge and power to face the issues of racism, patriarchy, and our anti-erotic society. Contemporary feminist thought Lorde set out to confront issues of racism in feminist thought. She maintained that a great deal of the scholarship of white feminists served to augment the oppression of black women, a conviction that led to angry confrontation, most notably in a blunt open letter addressed to the fellow radical lesbian feminist Mary Daly, to which Lorde claimed she received no reply. Daly’s reply letter to Lorde, dated 4½ months later, was found in 2003 in Lorde’s files after she died. This fervent disagreement with notable white feminists furthered Lorde’s persona as an outsider: "In the institutional milieu of black feminist and black lesbian feminist scholars [...] and within the context of conferences sponsored by white feminist academics, Lorde stood out as an angry, accusatory, isolated black feminist lesbian voice". The criticism was not one-sided: many white feminists were angered by Lorde’s brand of feminism. In her 1984 essay “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House,” Lorde attacked underlying racism within feminism, describing it as unrecognized dependence on the patriarchy. She argued that, by denying difference in the category of women, white feminists merely furthered old systems of oppression and that, in so doing, they were preventing any real, lasting change. Her argument aligned white feminists who did not recognize race as a feminist issue with white male slave-masters, describing both as “agents of oppression.” Lorde’s comments on feminism In Audre Lorde’s “Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference,” she writes: “Certainly there are very real differences between us of race, age, and sex. But it is not those differences between us that are separating us. It is rather our refusal to recognize those differences, and to examine the distortions which result from our misnaming them and their effects upon human behavior and expectation.” More specifically she states: “As white women ignore their built-in privilege of whiteness and define woman in terms of their own experience alone, then women of color become ‘other’.” Self-identified as “a forty-nine-year-old Black lesbian feminist socialist mother of two,” Lorde is considered as “other, deviant, inferior, or just plain wrong” in the eyes of the normative “white male heterosexual capitalist” social hierarchy. “We speak not of human difference, but of human deviance,” she writes. In this respect, Lorde’s ideology coincides with womanism, which “allows black women to affirm and celebrate their color and culture in a way that feminism does not.” Influences on Black Feminism Lorde’s work on black feminism continues to be examined by scholars today. Jennifer C. Nash examines how black feminists acknowledge their identities and find love for themselves through those differences. Nash cites Lorde, who writes, “I urge each one of us here to reach down into that deep place of knowledge inside herself and touch that terror and loathing of any difference that lives there. See whose face it wears. Then the personal as the political can begin to illuminate all our choices." Nash explains that Lorde is urging black feminists to embrace politics rather than fear it, which will lead to an improvement in society for them. Lorde adds, “Black women sharing close ties with each other, politically or emotionally, are not the enemies of Black men. Too frequently, however, some Black men attempt to rule by fear those Black women who are more ally than enemy.” Lorde insists that the fight between black women and men must end in order to end racist politics. Personal Identity Throughout Lorde’s career she included the idea of a collective identity in many of her poems and books. Audre Lorde did not just identify with one category but she wanted to celebrate all parts of herself equally. She was known to describe herself as African-American, black, feminist, poet, mother, etc. In her novel Zami: A New Spelling of My Name Lorde focuses on how her many different identities shape her life and the different experiences she has because of them. She shows us that personal identity is found within the connections between seemingly different parts of life. Personal identity is often associated with the visual aspect of a person, but as Lies Xhonneux theorizes when identity is singled down to just to what you see, some people, even within minority groups, can become invisible. In her late book The Cancer Journals she said “If I didn’t define myself for myself, I would be crunched into other people’s fantasies for me and eaten alive.” This is important because an identity is more than just what people see or think of a person, it is something that must be defined by the individual. “The House of Difference” is a phrase that has stuck with Lorde’s identity theories. Her idea was that everyone is different from each other and it is the collective differences that make us who we are, instead of one little thing. Focusing on all of the aspects of identity brings people together more than choosing one piece of an identity. Audre Lorde and womanism Audre Lorde’s criticism of feminists of the 1960s identified issues of race, class, age, gender and sexuality. Similarly, author and poet Alice Walker coined the term “womanist” in an attempt to distinguish black female and minority female experience from “feminism”. While “feminism” is defined as “a collection of movements and ideologies that share a common goal: to define, establish, and achieve equal political, economic, cultural, personal, and social rights for women” by imposing simplistic opposition between “men” and “women,” the theorists and activists of the 1960s and 1970s usually neglected the experiential difference caused by factors such as race and gender among different social groups. Womanism and its ambiguity Womanism’s existence naturally opens various definitions and interpretations. Alice Walker’s comments on womanism, that “womanist is to feminist as purple is to lavender,” suggests that the scope of study of womanism includes and exceeds that of feminism. In its narrowest definition, womanism is the black feminist movement that was formed in response to the growth of racial stereotypes in the feminist movement. In a broad sense, however, womanism is “a social change perspective based upon the everyday problems and experiences of black women and other women of minority demographics,” but also one that “more broadly seeks methods to eradicate inequalities not just for black women, but for all people” by imposing socialist ideology and equality. However, because womanism is open to interpretation, one of the most common criticisms of womanism is its lack of a unified set of tenets. It is also criticized for its lack of discussion of sexuality. Lorde actively strived for the change of culture within the feminist community by implementing womanist ideology. In the journal "Anger Among Allies: Audre Lorde’s 1981 Keynote Admonishing the National Women’s Studies Association," it is stated that Lorde’s speech contributed to communication with scholars’ understanding of human biases. While “anger, marginalized communities, and US Culture” are the major themes of the speech, Lorde implemented various communication techniques to shift subjectivities of the “white feminist” audience. Lorde further explained that “we are working in a context of oppression and threat, the cause of which is certainly not the angers which lie between us, but rather that virulent hatred leveled against all women, people of color, lesbians and gay men, poor people—against all of us who are seeking to examine the particulars of our lives as we resist our oppressions, moving towards coalition and effective action.” Audre Lorde and critique of womanism A major critique of womanism is its failure to explicitly address homosexuality within the female community. Very little womanist literature relates to lesbian or bisexual issues, and many scholars consider the reluctance to accept homosexuality accountable to the gender simplistic model of womanism. According to Lorde’s essay “Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference,” “the need for unity is often misnamed as a need for homogeneity.” She writes, “A fear of lesbians, or of being accused of being a lesbian, has led many Black women into testifying against themselves.” Contrary to this, Audre Lorde was very open to her own sexuality and sexual awakening. In Zami: A New Spelling of My Name, her famous “biomythography” (a term coined by Lorde that combines “biography” and “mythology”) she writes, “Years afterward when I was grown, whenever I thought about the way I smelled that day, I would have a fantasy of my mother, her hands wiped dry from the washing, and her apron untied and laid neatly away, looking down upon me lying on the couch, and then slowly, thoroughly, our touching and caressing each other’s most secret places.” According to scholar Anh Hua, Lorde turns female abjection—menstruation, female sexuality, and female incest with the mother—into powerful scenes of female relationship and connection, thus subverting patriarchal heterosexist culture. With such a strong ideology and open-mindedness, Lorde’s impact on lesbian society is also significant. An attendee of a 1978 reading of Lorde’s essay “Uses for the Erotic: the Erotic as Power” says: “She asked if all the lesbians in the room would please stand. Almost the entire audience rose.” Tributes The Callen-Lorde Community Health Center is an organization in New York City named for Michael Callen and Audre Lorde, which is dedicated to providing medical health care to the city’s LGBT population without regard to ability to pay. Callen-Lorde is the only primary care center in New York City created specifically to serve the LGBT community. The Audre Lorde Project, founded in 1994, is a Brooklyn-based organization for queer people of color. The organization concentrates on community organizing and radical nonviolent activism around progressive issues within New York City, especially relating to queer and transgender communities, AIDS and HIV activism, pro-immigrant activism, prison reform, and organizing among youth of color. The Audre Lorde Award is an annual literary award presented by Publishing Triangle to honor works of lesbian poetry, first presented in 2001. In 2014 Lorde was inducted into the Legacy Walk, an outdoor public display in Chicago, Illinois that celebrates LGBT history and people.

I grew up in the middle of a cornfield in Nebraska. My mother, born in 1950, and my father, born in 1924, raised me well. I had a great childhood, but my father dying when I was 13 had a large impact on me. I went down a rough road being a state ward, messing around with drugs and alcohol, and living life on the run. Through everything, however, I never stopped writing. Sure, I'd go through dry spells like we all do, but I've never given up. I write short stories, and poetry. I have a very abstract view on life, sometimes. My poems don't always make sense. But that's why I love to write; it doesn't always need to make sense to taste good on your tongue and feel right rolling across your lips. I was published by The American Poets Society in the Book Expressions at age 13 if any of you care to try to look me up. My piece was simply titled, 'Daddy'