Info

Diana bathing (The Fountain)

Jean Baptiste Camille Corot

1869 – 1870

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza

Thomas Parnell (11 September 1679– 24 October 1718) was an Anglo-Irish poet and clergyman who was a friend of both Alexander Pope and Jonathan Swift. He was the son of Thomas Parnell of Maryborough, Queen’s County (now Port Laoise, County Laoise), a prosperous landowner who had been a loyal supporter of Cromwell during the English Civil War and moved to Ireland after the restoration of the monarchy. Thomas was educated at Trinity College, Dublin and collated archdeacon of Clogher in 1705. He however spent much of his time in London, where he participated with Pope, Swift and others in the Scriblerus Club, contributing to The Spectator and aiding Pope in his translation of The Iliad. He was also one of the so-called “Graveyard poets”: his ‘A Night-Piece on Death,’ widely considered the first “Graveyard School” poem, was published posthumously in Poems on Several Occasions, collected and edited by Alexander Pope and is thought by some scholars to have been published in December of 1721 (although dated in 1722 on its title page, the year accepted by The Concise Oxford Chronology of English Literature; see 1721 in poetry, 1722 in poetry). It is said of his poetry 'it was in keeping with his character, easy and pleasing, enunciating the common places with felicity and grace. He died in Chester in 1718 on his way home to Ireland. His wife and children having died, his Laoise estate passed to his brother John, a judge and MP in the Irish House of Commons and the ancestor of Charles Stewart Parnell. Oliver Goldsmith wrote a biography of Parnell which often accompanied later editions of Parnell’s works. Works * Essay on the Different Stiles of Poetry (1713) * Battle of the Frogs and Mice (1717 translation in heroic couplets of a comic epic then attributed to Homer) * An example of his poetry is the opening stanza of his poem The Hermit References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Parnell

My first memories of writing begin in elementary school when one teacher assigned our class to write a story. He made some very encouraging comments and a writer was born. I have stacks of poems and songs collected over the years. I recently began blogging and found this site and am happy to share some of my work here. I hope you will let me know when you are inspired or touched by what I share with you. You, my readers, inspire me.

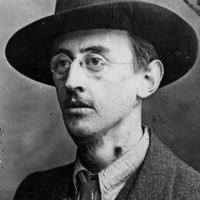

Luis Palés Matos. (Guayama, 20 de marzo de 1898 - 23 de febrero de 1959). Escritor, novelista, poeta y periodista puertorriqueño. De familia culta, inició pronto su actividad literaria y, con diecisiete años, publicó su primer libro de poemas. Sus lecturas de Julio Verne y E.T.A. Hoffmann, entre otros, le acercaron a la literatura universal, formándose como autodidacta. Más tarde dirigíó el diario El Pueblo en su ciudad natal. En San Juan trabajó para El Imparcial o Puerto Rico Ilustrado, además de otros diarios y revistas, aunque debió ganarse la vida como oficinista, repartidor, actor de teatro e incluso secretario del Presidente del Senado. Casado, su matrimonio apenas duró un año al fallecer su esposa de tuberculosis en 1919. En la capital conoció a José de Diego Padró. Ambos representarán el comienzo de la poesía de vanguardia en el país conocido como el diepalismo donde prima la sonoridad y musicalidad de los versos. En la década de 1920 participó en la actividad política convulsa de Puerto Rico, integrándose en la Alianza Puertorriqueña, siendo un activo orador independentista. En estos años desarrolló lo que sería la poesía negra o el verso negro, con una visión de la cultura negra puertorriqueña integrada dentro de la originalidad de su obra de sonidos armoniosos. La influencia que ejerció sobre otros autores de Sudamérica fue destacable, sobre todo en hombres de la talla de Nicolás Guillén. Se casó nuevamente en 1930. En las décadas de 1940 y 1950 viajó por Estados Unidos donde ofreció distintas conferencias en varias instituciones y universidades. Referencias Wikipedia – http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luis_Palés_Matos

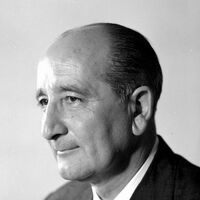

José María Pemán y Pemartín (retratos) (Cádiz, 8 de mayo de 1897 – 19 de julio de 1981) fue un escritor español. Formación Junto con su hermano César, procedía de una familia de la buena sociedad de Cádiz. Su padre fue el abogado en ejercicio y diputado conservador gaditano Juan Gualberto Pemán y Maestre (1859-1922), perteneciente a la familia política de la Restauración, y su madre María Pemartín y Carrera Laborde Aramburu, de entronque jerezano. En la fachada de la casa en que nació en Cádiz (calle Isabel La Católica nº 12) existe una gran lápida, con una figura alegórica con la estética de la época, y su busto en bajorrelieve en bronce, obra del escultor Juan Luis Vassallo. Pemán creció durante la Restauración en el seno de un orden social burgués, parlamentario pero no democrático, y quasi patriarcal (cacicato estable) considerado "natural" y, por tanto, inmutable y legítimo: «La desigualdad social (...) es una ley inexorable contra la cual es inútil luchar porque Dios así lo ha dispuesto; nuestro deber es acatar Su insondable Voluntad y resignarnos cada uno con nuestra suerte, cumpliendo estrictamente en todas circunstancias nuestros deberes cristianos, que a la postre resultará lo más provechoso para todos, no sólo en el otro Mundo, sino en éste» . Conde de Rivadavia Referencias Wikipedia – http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/José_María_Pemán

Luego de décadas de silenciamiento o relegación, el escritor cubano Virgilio Piñera (1912-1979) ocupa un sitio referencial en la literatura cubana contemporánea. Los avatares del canon nacional de las letras se cumplen, como en pocos autores latinoamericanos del siglo XX, en este poeta, dramaturgo y narrador, nacido hace 100 años en Cárdenas, Matanzas. Los atributos de Piñera que molestaban al Estado cubano, hace apenas 20 años, son los mismos que le han ganado una presencia tutelar, cada vez más discernible entre las últimas generaciones de escritores de la isla y la diáspora. Virgilio Piñera (4 de agosto de 1912, Cárdenas (Matanzas), 18 octubre de 1979 - La Habana) fue un poeta cubano. Vida Piñera cursó sus primeros estudios en su localidad natal, pero en 1925 se trasladó con su familia a pepeCamagüey, donde estudió el bachillerato. En 1938 se instaló en La Habana, en cuya universidad se doctoró en Filosofía y Letras en 1940. Ya el año anterior había empezado a publicar, sobre todo poemas, en la revista Espuela de plata, predecesora de Orígenes, en la que coincidió con José Lezama Lima. En 1941 vio la luz su primer poemario, Las furias, y ese mismo año escribió también la que es quizá su obra teatral más importante, Electra Garrigó, que se estrenó en La Habana, ocho años después, y constituyó uno de los grandes hitos del teatro cubano, para muchos críticos, como Rine Leal o Raquel Carrió, el verdadero comienzo del teatro cubano moderno. En 1942 fundó la efímera revista Poeta, de la que fue director. Al año siguiente publicó el extenso poema La isla en peso, una de las cumbres de la poesía cubana, que en su momento fue, sin embargo, objetado por grandes poetas como Gastón Baquero o Eliseo Diego y críticos como Cintio Vitier. Aunque en La isla en peso se considera en la actualidad como uno de los momentos más altos de la poesía cubana. Cuando en 1944 Lezama y Rodríguez Feo fundaron la revista Orígenes, Piñera formó parte del plantel inicial de colaboradores, a pesar de que mantenía importantes discrepancias estéticas con el grupo de poetas de la revista. Allí publicó poesía y un excelente ensayo: "El secreto de Kafka". Preparó, asimismo, un número sobre literatura argentina. En febrero de 1946 viajó a Buenos Aires, donde residió, con algunas interrupciones, hasta 1958. Allí trabajó como funcionario del consulado de su país, como corrector de pruebas y como traductor.1 En la capital argentina hizo amistad con el escritor polaco Witold Gombrowicz, y formó parte del equipo de traductores que llevaron a cabo la versión castellana de Ferdydurke. También conoció a Jorge Luis Borges, Victoria Ocampo, Graziella Peyrou y a José Bianco, quien prologó su volumen de cuentos El que vino a salvarme, publicado por la Editorial Sudamericana. Continuó colaborando con Orígenes con cuentos, ensayos y reseñas críticas. En 1948 se estrenó en La Habana Electra Garrigó, mal acogida por la crítica. Por entonces escribió otras obras teatrales: Jesús y Falsa alarma, obra considerada una de las primeras muestras de teatro del absurdo, anterior incluso a La cantante calva de Eugène Ionesco. En 1952 publicó su primera novela, La carne de René. En 1955, tras el final de Orígenes, marcado por una agria disputa entre Lezama Lima y Rodríguez Feo, fundó con este último la revista Ciclón, de gran importancia en la historia de la literatura cubana. Por entonces colaboró también con la revista argentina Sur y con las francesas Lettres Nouvelles y Les Temps Modernes. En 1958 abandonó Argentina y se instaló definitivamente en Cuba, donde viviría hasta su muerte. Tras el triunfo de la Revolución Cubana, Piñera colaboró en el periódico Revolución y en su suplemento Lunes de Revolución. En 1960 reestrenó Electra Garrigó y publicó su Teatro completo. En 1968 recibió el Premio Casa de las Américas de teatro por Dos viejos pánicos, obra que no fue estrenada en Cuba hasta principios de los años noventa. Recientemente en México ha tenido una exitosa temporada una nueva interpretación de "Electra Garrigo" titulada "El Son de Electra" bajo la dirección del destacado creador Ramón Díaz y las actuaciones de Thais Valdés y Sandra Muñoz y en La Habana ha reaparecido esta obra bajo la dirección de Roberto Blanco y últimamente de Raúl Martín con el Grupo Teatral La Luna. A partir de 1971 y hasta su muerte, Piñera sufrió un fuerte ostracismo por parte del régimen y de las instituciones culturales oficiales cubanas, en gran parte debido a una radical diferencia ideológica y a su condición sexual, ya que nunca escondió su homosexualidad.2 El famoso escritor cubano disidente Reinaldo Arenas, amigo de Piñera, cuenta ese episodio en sus memorias Antes que anochezca. Como narrador, destaca por su humor negro, dentro de la línea del absurdo. Fue también un destacado traductor, y vertió al español obras de Jean Giono, Imre Madách, Charles Baudelaire y de Witold Gombrowicz, entre muchos otros.1 Sus Cuentos completos han sido publicados por la Editorial Alfaguara. Su poesía completa, así como La carne de René, aparecieron bajo el sello de Tusquets Editores. OBRAS Poesía * 1941 - Las furias * 1943 - La isla en peso (reedición cortada en Virgilio Piñera La poesía, La Habana * 1965 - a parte de unas modificaciones mínimas, sobre todo unas correcciones ortográficas añadiendo otros errores, el cambio principal es la corte de un parágrafo sobre la masturbación; reeditado en esta versión truncada también en Virgilio Piñera 'La isla en peso. Obra poética', compilación y prólogo de Antón Arrufat, La Habana 1999 y Barcelona: Tusquets editores 2000, colección Nuevos textos sagrados; la versión original con unas pocas diferencias mínimas más se encuentra entre otros en javiergato.blogspot.com en la parte 'Taedium mundi' ) * 1944 - Poesía y prosa * 1969 - "La vida entera" * 1988 - Una broma colosal * 1994 - Poesía y crítica Cuento * 1942 - El conflicto * 1956 - Cuentos fríos * 1961- "Oficio de tinieblas" * 1970 - El que vino a salvarme * 1987 - Un fogonazo * 1987 - Muecas para escribientes * 1992 - Algunas verdades sospechosas * 1992 - El viaje * 1994 - Cuentos de la risa del horror (antología) * 2008 - Cuentos fríos. El que vino a salvarme. Edición de Vicente Cervera y Mercedes Serna Cátedra, 2008. Novela * 1952 - La carne de René, Buenos Aires, reedición (modificada) Tusquets Editores, Colección Andanzas, Barcelona, 2000. * 1963 - Pequeñas maniobras * 1967 - Presiones y diamantes * 1997 - El caso baldomero Teatro * 1959 - Electra Garrigó * 1959 - Aire frío * 1960 - Teatro completo * 1968 - Dos viejos pánicos * 1986 - Una caja de zapatos vacía * 1990 - Teatro inconcluso * 1993 - Teatro inédito Traducción * 1947 - Witold Gombrowicz Ferdydurke (traducido por Virgilio Piñera junto con Humberto Rodríguez Tomeu y Adolfo de Obieta y 'a veces veinte personas', vea Witold Gombrowicz Diarios, cap. XV, y Virgilio Piñera La vida tal cual, p. 32, donde describe como Gombrowicz le declara 'presidente del Comité de Traducción', en Unión 10 / 1990, La Habana, número dedicado a Virgilio Piñera, p. 22 - p. 35) Referencias Wikipedia – http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virgilio_Piñera Cien años del nacimiento del poeta y dramaturgo cubano En su libro Inventario secreto de La Habana, Abilio Estévez relata un encuentro con Virgilio Piñera en 1979, pocos meses antes de la muerte del gran poeta cubano. En un momento de la conversación, Estévez le preguntó cuál creía que sería su destino literario post mortem. “Me publicarán, me homenajearán y seré por fin el apóstol que siempre debí ser”, disparó el autor de La carne de René con sonrisa escéptica y mirada burlona. La profecía de Piñera (Cárdenas, 1912) terminó cumpliéndose. El escritor solitario, el francotirador, el nadador a contracorriente, como lo ha definido Abilio Estévez, recibió este año un homenaje oficial en La Habana al cumplirse el centenario de su nacimiento. Pero tuvieron que pasar muchos años para que sus libros se editaran en la isla y sus obras dramáticas se representaran en los teatros cubanos. Marginado y desactivado por la Revolución durante décadas, la figura de Piñera —considerado por algunos críticos como el mejor dramaturgo cubano del siglo XX— no levantó vuelo hasta que fue reivindicada por los jóvenes creadores de los años ochenta, pero el régimen no le perdonó la disidencia intelectual de la que hizo gala toda su vida hasta hace bien poco, cuando el general Raúl Castro lo rescató del ostracismo, como si el creador de Electra Garrigó fuera una de esas “absurdas prohibiciones” que el hermano menor de Fidel se dispuso a eliminar para darle a su mandato una pátina de aperturismo. La historia podría haber sido diferente para uno de los máximos exponentes del teatro del absurdo (su Falsa alarma fue publicada en 1948, dos años antes de que Ionesco revolucionara el género con La cantante calva) si se hubiera plegado a las exigencias del guión tras el triunfo de la Revolución en 1959. Un guión que, con respecto a la política cultural, Fidel Castro esbozó en el denominado “Encuentro con los intelectuales”, tres jornadas históricas celebradas en la Biblioteca Nacional de La Habana en junio de 1961 en las que el nuevo régimen dejó sentadas las pautas por las que debía regirse el pensamiento de la época: no habría vida (intelectual) más allá del binomio patria-revolución, a saber: Martí y Fidel. Una vez derribada la dictadura de Batista, a la que se habían opuesto con más o menos ardor patriótico los intelectuales cubanos, estos buscaban su lugar en la alborada revolucionaria. Como otros, Piñera albergaba dudas y recelos sobre el nuevo papel que debía desempeñar la intelligentsia de la isla. Y así se lo hizo saber al Comandante: “Yo quiero decir que tengo mucho miedo. No sé por qué tengo ese miedo pero eso es todo lo que tengo que decir”. ¿Miedo? Piñera pronunció la palabra maldita, aquella que presidiría las relaciones entre la cultura y la Revolución (como quedó de manifiesto en el “caso Padilla” o en el “quinquenio gris”, de 1971 a 1976). Fidel respondió a las inquietudes de Padilla y otros con uno de esos discursos maratónicos que lo harían célebre (y que ha pasado a la historia como “Palabras a los intelectuales”). Y despejó incertidumbres: ¿Cuáles son los derechos de los escritores y de los artistas, revolucionarios o no revolucionarios? Dentro de la Revolución, todo; contra la Revolución, ningún derecho”. Es decir, la cultura quedaría atrapada en la isla entre la sumisión al nuevo establishment sovietizado y la “muerte civil”. Piñera, que ya había publicado sus mejores obras antes del triunfo revolucionario, editó algunos libros más en la década de los sesenta pero fue orillado poco a poco por los prebostes culturales del régimen. En 1969 publicaría su último libro en vida, bajo el curioso título de La vida entera. Desde entonces, hasta su muerte en 1979, no volvió a publicar una sola línea. Pero nunca dejó de escribir. El desdén de los dirigentes revolucionarios hacia Piñera mucho tuvo que ver con su condición de homosexual. Baste recordar que en el primer congreso de Educación y Cultura, celebrado en 1971, el régimen había definido la homosexualidad como una “patología social”. El propio Piñera ya lo había presagiado en un pasaje de La vida tal cual, sus textos autobiográficos: “No bien tuve la edad exigida para que el pensamiento se traduzca en algo más que soltar la baba y agitar los bracitos, me enteré de tres cosas: lo bastante sucias como para no poderme lavar jamás de las mismas. Aprendí que era pobre, que era homosexual y que me gustaba el arte”. El relato de Abilio Estévez sobre la vida cotidiana de ese Bartleby clandestino es estremecedor, pues nos habla de un hombre que casi raya con el indigente. Un literato devenido en menospreciado traductor que se levantaba de madrugada para escribir y, cuando el día se echaba encima, “descendía hacia los abismos de la realidad con una jaba (bolsa) de saco, una cantina de metal y un frasco de medicina vacío”. El pomo de medicina era para el “café aguado” de la cafetería Las Vegas. En la cantina de metal le servían a Piñera unos espaguetis a pelo en una pizzería de la esquina de Infanta y San Lázaro. En la jaba guardaba el escritor el pastel con sabor a manzana que había comprado tras guardar una cola de una hora en el Supercake, una pastelería abierta en Zapata y Belascoaín. “Lo único que mereció (cuando murió) —escribe Abilio Estévez— fue una nota fugaz en los periódicos oficiales, la misma nota en todos los periódicos, con aquella helada sintaxis y estudiada economía de palabras”. Tal vez, mientras aguardaba la cola en el Supercake, Piñera se repitiera a sí mismo esa letanía que susurraba a sus allegados: “Nunca debí regresar de Buenos Aires”. En la Argentina vivió el poeta 12 años de forma intermitente (1946-1958) como funcionario de la embajada cubana. Fueron tiempos fructíferos para Piñera desde el punto de vista creativo. En esos años escribe su mejor novela, La carne de René (1952) los Cuentos fríos (1956) y buena parte de sus mejores obras dramáticas, además de dirigir la revista Ciclón, la contracara del Orígenes de Lezama Lima (otro de los grandes olvidados de la Revolución). Y frecuenta a algunos de los grandes narradores argentinos de la época: Borges, Sabato, Macedonio Fernández… El autor de El Aleph tuvo a bien publicar uno de los cuentos de Piñera en uno de los números de Anales de Buenos Aires (1947). Aunque sin duda el escritor del que más cercano se sintió fue Wiltod Gombrovizc. Gracias a sus conocimientos del francés, idioma que también hablaba el autor polaco, Piñera presidió el comité que realizó en el café Rex la traducción colectiva de Ferdydurke, el artefacto literario con el que Gombrovizc saltó a la fama y que vio la luz en español en 1947. En agradecimiento, Gombrovizc nombró a su colega cubano, con ironía ubuesca, “jefe del ferdydurkismo sudamericano”. Antes de la etapa argentina, Piñera ya había publicado la que acabaría siendo su gran obra poética: La isla en peso (1943), un libro que rompe con el barroquismo de autores como Lezama o Carpentier y también con el pensamiento tradicional cubano, que otorgaba al Caribe un componente mágico-espiritual arcádico, como recuerda el escritor Damaris Calderón. La isla, para Piñera, está marcada más bien por una condición negativa, claustrofóbica, por esa “maldita circunstancia” que canta el poeta: “Esta noche he llorado al conocer a una anciana que ha vivido ciento ocho años rodeada de agua por todas partes”. Como un río subterráneo, la palabra atrapada de Virgilio Piñera no ha cesado de empapar las distintas poéticas que se han sucedido en la isla desde los años sesenta del siglo pasado. La obra narrativa de Reynaldo Arenas (la versión rebelde de Piñera), Severo Sarduy, Abilio Estévez o Antón Arrufat le debe mucho al autor de Cuentos fríos. Ensayistas jóvenes como Rafael Rojas, Antonio José Ponte o Iván de la Nuez (los tres, en el exilio) reivindican en nuestros días el inconformismo intelectual de Piñera, un rasgo distintivo en toda su obra que, para Rojas y Ponte, invalida los homenajes y las vindicaciones actuales del aparato cultural del régimen. “Los atributos de Piñera que molestaban al Estado cubano, hace apenas 20 años, son los mismos que le han dado una presencia tutelar, cada vez más discernible entre las últimas generaciones de escritores de la isla y la diáspora”, escribe Rojas. Y añade: “Un escritor como Piñera merece que (…) se piense críticamente su apropiación por parte del mismo Estado que lo marginó y lo silenció. El mismo Estado que sostiene de jure y de facto leyes e instituciones que un admirador de El pensamiento Cautivo, de Milosz, no podría aprobar”. Porque el pensamiento en la isla, como recuerda Rojas aludiendo al libro de Milosz, sigue cautivo, apresado por la tenaza del discurso único. Solo desde algunas bitácoras del ciberespacio es posible la crítica. El escritor Ángel Santiesteban (autor del blog Los hijos que nadie quiso) se preguntaba recientemente cuántos libros dejó de escribir Piñera tras ser arrumbado por el régimen: “¿De cuántos maravillosos absurdos se privó la Literatura por culpa de los gendarmes de la cultura oficial cubana?”. La huella de Piñera llena las plumas de las últimas hornadas de poetas cubanos. Juan Carlos Flores, poeta de la marginalidad, esculpe versos-martillo desde su departamento en Alamar (en el extrarradio habanero), tan austero y sencillo como aquel de las calles 27 y N en el barrio del Vedado, cuartel general de la tristeza. Flores, como otros jóvenes poetas, también ha rendido tributo al escritor solitario, al francotirador, al nadador a contracorriente y a su visión negativa de la insularidad: “Oscar Wilde tuvo su estancia gélida, el aislamiento pudo ser la tuya. A la hora anunciada por los especialistas en posteridad te convertiste en una isla, isla hundida en qué profundo y olvidado mar oscuro”. Referencias http://www.jotdown.es/2012/11/virgilio-pinera-y-el-agua-por-todas-partes/

I am a blogger, poet and writer. I own wn Monterey Consulting which examines cost centers at mainly industrial accounts and attempts to reduce cost and get paid in the process. Sometimes, I look at natural gas well cash flows to determine private well owners are getting paid properly. I am good at negotiating and is how I make money consulting. I have a 9 year old son named Joseph. I am in the midst of a divorce. It's been painful for sure. I feel so bad for my son. He's strong and resilient- handling it great on the outside. I wonder what goes on in that little head of his. I worry about him sometimes that he is getting all his parental, moral and general life guidance. What's important in this world--what's not. Things dads say. Moms too. I love learning and researching new and sometimes Paranormal type phenomena. Sometimes this research gets me into trouble, both personally and professionally:it involves military grade weapons being remotely used against Americans as a social experiment. It involves emotion manipulation, increase in sex drives, pharmaceuticals, directed brainwashing targeted media custom designed for you. Sometimes they give you your own private line to call in on. Guessing. It involves the research and study of Electromagnetic Radiation as a naturally occurring energy in nature as well as man made ie electricity I am studying various relationships between EMR and other natural and man made variables. It involves several of the sciences including Astronomy, the laws of physics, chemistry and how the principles and properties of predictable data based on current accepted formulae can be Manipulated. "It's simply cause and effect". Tbc cause however is not always as pure as it seems. There are military personnel that are part of the civilian workforce. They cause accidents to your car, they enter your car and take things pertaining to a book I am writing. Cleaned off my entire c drive as well as stole the printed copy I had in a file drawer. WTF

Brian Patten (born 7 February 1946) is an English poet Background Born near the Liverpool docks, Patten attended Sefton Park School in the Smithdown Road area of Liverpool, where he was noted for his essays and greatly encouraged in his work by Harry Sutcliffe, his form teacher. He left school at fifteen and began work for The Bootle Times writing a column on popular music. One of his first articles was on Roger McGough and Adrian Henri, two pop-oriented Liverpool poets who later joined Patten in a best-selling poetry anthology called The Mersey Sound, drawing popular attention to his own contemporary collections Little Johnny’s Confession (1967) and Notes to the Hurrying Man (1969). Patten received early encouragement from Philip Larkin. The collections Storm Damage (1988) and Armada (1996) are more varied, the latter featuring a sequence of poems concerning the death of his mother and memories of his childhood. Armada is perhaps Patten’s most mature and formal book, dispensing with much of the playfulness of former work. He has also written comic verse for children, notably Gargling With Jelly and Thawing Frozen Frogs. Patten’s style is generally lyrical and his subjects are primarily love and relationships. His 1981 collection Love Poems draws together his best work in this area from the previous sixteen years. Tribune has described Patten as “the master poet of his genre, taking on the intricacies of love and beauty with a totally new approach, new for him and for contemporary poetry.” Charles Causley once commented that he “reveals a sensibility profoundly aware of the ever-present possibility of the magical and the miraculous, as well as of the granite-hard realities. These are undiluted poems, beautifully calculated, informed– even in their darkest moments– with courage and hope.” Patten writes extensively for children as well as adults. He has been described as a highly engaging performer, and gives readings frequently. Over the years he has read alongside such poets as Pablo Neruda, Allen Ginsberg, Stevie Smith, Laurie Lee and Robert Lowell. His books have in recent years been translated into Italian, Spanish, German and Polish. His children’s novel Mr Moon’s Last Case won a special award from the Mystery Writers of America Guild. In 2002 Patten accepted the Cholmondeley Award for services to poetry. Together with Roger McGough and the late Adrian Henri, he was honoured with the Freedom of the City of Liverpool. Selected bibliography Poetry collections for adults * The Mersey Sound * Little Johnny’s Confession * Notes to the Hurrying Man * The Irrelevant Song * Vanishing Trick * Grave Gossip * Love Poems * Storm Damage * Grinning Jack * Armada * Selected Poems Penguin Books * The new Collected Love Poems * The projectionist’s nightmare * Geography lesson Books for children * The Elephant and the Flower * Jumping Mouse * Emma’s Doll * Gargling With Jelly * Mr Moon’s Last Case * Jimmy Tag-Along * Thawing Frozen Frogs * Juggling With Gerbils * The Story Giant * Impossible Parents, illustrated by Arthur Robins (Walker Books, 1994), OCLC 31708253 * The Impossible Parents Go Green, illus. Robins (Walker, 2000) * The Most Impossible Parents, illus. Robins (Walker, 2010) As editor * The Puffin Book of Utterly Brilliant Poetry * The Puffin Book of Modern Children’s Verse References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brian_Patten

Michael Palmer (born May 11, 1943) is an American poet and translator. He attended Harvard University where he earned a BA in French and an MA in Comparative Literature. He has worked extensively with Contemporary dance for over thirty years and has collaborated with many composers and visual artists. Palmer has lived in San Francisco since 1969. Palmer is the 2006 recipient of the Wallace Stevens Award from the Academy of American Poets. This $100,000 (US) prize recognizes outstanding and proven mastery in the art of poetry. Beginnings Michael Palmer began actively publishing poetry in the 1960s. Two events in the early sixties would prove particularly decisive for his development as a poet. First, he attended the now famous Vancouver Poetry Conference in 1963. This July–August 1963 Poetry Conference in Vancouver, British Columbia spanned three weeks and involved about sixty people who had registered for a program of discussions, workshops, lectures, and readings designed by Warren Tallman and Robert Creeley as a summer course at the University of B.C. There Palmer met writers and artists who would leave an indelible mark on his own developing sense of a poetics, especially Robert Duncan, Robert Creeley, and Clark Coolidge, with whom he formed lifelong friendships. It was a landmark moment as Robert Creeley observed: Vancouver Poetry Conference brought together for the first time, a decisive company of then disregarded poets such as Denise Levertov, Charles Olson, Allen Ginsberg, Robert Duncan, Margaret Avison, Philip Whalen... together with as yet unrecognised younger poets of that time, Michael Palmer, Clark Coolidge and many more.” Palmer’s second initiation into the rites of a public poet began with the editing of the journal Joglars with fellow poet Clark Coolidge. Joglars (Providence, Rhode Island) numbered just three issues in all, published between 1964–66, but extended the correspondence with fellow poets begun in Vancouver. The first issue appeared in Spring 1964 and included poems by Gary Snyder, Michael McClure, Fielding Dawson, Jonathan Williams, Lorine Niedecker, Robert Kelly, and Louis Zukofsky. Palmer published five of his own poems in the second number of Joglars, an issue that included work by Larry Eigner, Stan Brakhage, Russell Edson, and Jackson Mac Low. For those who attended the Vancouver Conference or learned about it later on, it was apparent that the poetics of Charles Olson, proprioceptive or Projectivist in its reach, was exerting a significant and lasting influence on the emerging generation of artists and poets who came to prominence in the 1950s and 1960s. Subsequent to this emerging generation of artists who felt Olson’s impact, poets such as Robert Creeley and Robert Duncan would in turn exert their own huge impact on our national poetries (see also: Black Mountain poets and San Francisco Renaissance). Of this particular company of poets encountered in Vancouver, Palmer says: ...before meeting that group of poets in 1963 at the Vancouver Poetry Conference, I had begun to read them intensely, and they proposed alternatives to the poets I was encountering at that time at Harvard, the confessional poets, whose work was grounded to a greater or lesser degree in New Criticism, at least those were their mentors. The confessional poets struck me as people absolutely lusting for fame, all of them, and they were all trying to write great lines. Early development of poetry and poetics Following the Vancouver Conference, Robert Duncan and Robert Creeley remained primary resources. Both poets had a lasting, active influence on Palmer’s work which has extended until the present. In an essay, “Robert Duncan and Romantic Synthesis” (see 'External links’ below), Palmer recognizes that Duncan’s appropriation and synthesis of previous poetic influences was transformed into a poetics noted for “exploratory audacity... the manipulation of complex, resistant harmonies, and by the kinetic idea of ”composition by field", whereby all elements of the poem are potentially equally active in the composition as 'events’ of the poem". And if this statement marks a certain tendency readers have noted in Palmer’s work all along, or remains a touchstone of sorts, we sense that from the beginning Palmer has consistently confronted not only the problem of subjectivity and public address in poetry, but the specific agency of Poetry and the relationship between poetry and the political: "The implicit... question has always concerned the human and social justification for this strange thing, poetry, when it is not directly driven by the political or by some other, equally other evident purpose [...] Whereas the significant artistic thrust has always been toward artistic independence within the world, not from it.” So for Michael Palmer, this tendency seems there from the beginning. Today these concerns continue through multiple collaborations across the fields of poetry, dance, translation, and the visual arts. Perhaps similar to Olson’s impact on his generation, Palmer’s influence remains singular and palpable, if difficult to measure. Since Olson’s death in 1970, we continue to be, following upon George Oppen’s phrase, carried into the incalculable, As Palmer recently noted in a blurb for Claudia Rankine’s poetic testament Don’t Let Me Be Lonely (2004), ours is “a time when even death and the self have been re-configured as commodities”. Work Palmer is the author of twelve full-length books of poetry, including Thread (2011), Company of Moths (2005) (shortlisted for the 2006 Canadian Griffin Poetry Prize), Codes Appearing: Poems 1979-1988 (2001), The Promises of Glass (2000), The Lion Bridge: Selected Poems 1972-1995 (1998), At Passages (1996), Sun (1988), First Figure (1984), Notes for Echo Lake (1981), Without Music (1977), The Circular Gates (1974), and Blake’s Newton (1972). A prose work, The Danish Notebook, was published in 1999. In the spring of 2007, a chapbook, The Counter-Sky (with translations by Koichiro Yamauchi), was published by Meltemia Press of Japan, to coincide with the Tokyo Poetry and Dance Festival. His work has appeared in literary magazines such as Boundary 2, Berkeley Poetry Review, Sulfur, Conjunctions, Grand Street and O-blek. Besides the 2006 Wallace Stevens Award, Michael Palmer’s honors include two grants from the Literature Program of the National Endowment for the Arts. In 1989-90 he was a Guggenheim Fellow. During the years 1992–1994 he held a Lila Wallace-Reader’s Digest Fund Writer’s Award. From 1999 to 2004, he served as a Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets. In the spring of 2001 he received the Shelly Memorial Prize Prize from the Poetry Society of America. Introducing Palmer for a reading at the DIA Arts Center in 1996, Brighde Mullins noted that Palmer’s poetics is both “situated yet active”. Palmer alludes to this himself, perhaps, when he speaks of poetry signaling a “site of passages”. He says, “The space of the page is taken as a site in itself, a syntactical and visual space to be expressively exploited, as was the case with the Black Mountain poets, as well as writers such as Frank O’Hara, perhaps partly in response to gestural abstract painting.” Elsewhere he observes that “in our reading we have to rediscover the radical nature of the poem.” In turn, this becomes a search for “the essential place of lyric poetry” as it delves “beneath it to its relationship with language”. Since he seems to explore the nature of language and its relation to human consciousness and perception, Palmer is often associated with the Language poets (sometimes referred to as the L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poets, after the magazine that bears that name). Of this particular association, Palmer comments in a recent (2000) interview: It goes back to an organic period when I had a closer association with some of those writers than I do now, when we were a generation in San Francisco with lots of poetic and theoretical energy and desperately trying to escape from the assumptions of poetic production that were largely dominant in our culture. My own hesitancy comes when you try to create, let’s say, a fixed theoretical matrix and begin to work from an ideology of prohibitions about expressivity and the self—there I depart quite dramatically from a few of the Language Poets. Critical reception Michael Palmer’s poetry has received both praise and criticism over the years. Some reviewers call it abstract. Some call it intimate. Some call it allusive. Some call it personal. Some call it political. And some call it inaccessible. While some reviewers or readers may value Palmer’s work as an “extension of modernism”, they criticize and even reject Palmer’s work as discordant: an interruption of our composure (to invoke Robert Duncan’s phrase). Palmer’s own stated poetics will not allow or settle for “vanguard gesturalism”. In a singular confrontion with the modernist project, the poet must suffer 'loss’, embrace disturbance and paradox, and agonize over what cannot be accounted for. It is a poetry that can, at once, gesture toward post-modern, post-avant-garde, semiotic concerns even as it acknowledges that ...the artist after Dante’s poetics, works with all parts of the poem as polysemous, taking each thing of the composition as generative of meaning, a response to and a contribution to the building form.[...]But this putting together and rendering anew operates in our own apprehension of emerging articulations of time. Every particular is an immediate happening of meaning at large; every present activity in the poem redistributes future as well as past events. This is a presence extended in a time we create as we keep words in mind.” We can recognize that the “weary beauty” of Palmer’s work bespeaks the tension and accord he offers toward the Modernists and the vanguardists, even as he is seeking to maintain or at least continue to search for an ethics of the I/Thou. It is an awkward truce we make with modernism when there is no cessation of hostilities. But sometimes in reading Palmer’s work we recognize (almost against ourselves) a poetry that is described as surreal in context and contour, livid in aural accomplishment, but all the while confronts the reader with a poetics both active and situated. And if Palmer is sometimes praised for this, more often than not he is criticized, rebuked, vilified and dismissed (just as Paul Celan was) for hermeticism, deliberate obscurity, and bogus erudition. Palmer admits to a stated “essential errancy of discovery in the poem” that would not necessarily be a “unified narrative explanation of the self”, but would allow for itself “cloaked meaning and necessary semantic indirection” Confrontation with Modernism He remains candid about the giants of modernism: i.e., Yeats, Eliot and Pound. Whether it is the fascism of Ezra Pound or the less overt but no less insidious anti-semitism found in the work of T. S. Eliot, Palmer’s position is a fierce rejection of their politics, but qualified with the acknowledgment that, as Marjorie Perloff has observed of Pound, “he remains the great inventor of the period, the poet who really MADE THINGS NEW”. Thus, Palmer decries that what remains for us is something quite harrowing “inscribed at the heart of modernism”. Perhaps we can invoke one of Palmer’s real 'heroes’, Antonio Gramsci, and say here, now, what precisely has been inscribed over against what today (in the vicious circles of media and cultural production) is merely forecast as cultural hegemony. So if Palmer, on the one hand, variously describes or defines an Ideology as that which “invades the field of meaning”, we recognize not only in Pound or Eliot, but now as if against ourselves, that ideology implicitly deploys values and premises that must remain unspoken in order for them to function as ideology or to remain hidden in plain sight, as such. At some point we can invoke the 'post-ideological’ stance of Slavoj Žižek who, after Althusser, jettisons the Marxist equation: ideology=false consciousness and say that, perhaps Ideology, to all intents and purposes, IS consciousness. As a way out of this seeming double-bind, or to his admissions that poetry is, as Pound observed, “news that stays news”, that it remains an active and viable (or “actively situated”) principle within the social dynamic, critics and readers alike point to Palmer’s own avowals of an emerging countertradition to the prevailing literary establishment: an 'alternative tradition’ that just slipped under the radar as far as the Academy and its various 'schools’ of poetry are concerned. Though not always so visible, this counter-tradition continues to exert an underground influence. Poetry, as critique or praise, can perhaps in its reach exceed the grasp of modernism and procure for us as visible again, that which is all or nothing except for the 'ghostlier demarcations’ of the social wager within sight of the shipwreck of the singular (as George Oppen characterized it) which denotes or delimits the very idea of the social, if not the very idea that there is a definition of the social other than this: the community of those who have no community. Indeed, the unavowable community (to borrow a title and phrasing from Maurice Blanchot). Faced with shipwreck, “in the dark” amidst the ravished heresies of the unspoken as even against silence itself, we can think with the poem. With fierce determination or graceful adherence we can perhaps even “see” with the poem, account for its usefulness. Even as we use the language, attend to its fissures and abhorrences, language in turn uses us, or has its own uses for us, as Palmer attests: Palmer has repeatedly stated, in interviews and in various talks given across the years, that the situation for the poet is paradoxical: a seeing which is blind, a “nothing you can see”, an “active waiting”, “purposive, sometimes a music”, or a “nowhere” that is "now / here". For Palmer, it is a situation which is never over, and yet it mysteriously starts up again each day, as if describing a circle. Poetry can “interrogate the radical and violent instability of our moment, asking where is the location of culture, where the site of self, selves, among others” (as Palmer has characterized the poetry of Myung Mi Kim). Collaborations Palmer has published translations from French, Russian and Brazilian Portuguese, and has engaged in multiple collaborations with painters. These include the German painter Gerhard Richter, French painter Micaëla Henich, and Italian painter Sandro Chia. He edited and helped translate Nothing The Sun Could Not Explain: Twenty Contemporary Brazilian Poets (Sun & Moon Press, 1997). With Michael Molnar and John High, Palmer helped edit and translate a volume of poetry by the Russian poet Alexei Parshchikov, Blue Vitriol (Avec Books, 1994). He also translated “Theory of Tables” (1994), a book written by Emmanuel Hocquard, a project that grew out of Hocquard’s translations of Palmer’s “Baudelaire Series” into French. Palmer has written many radio plays and works of criticism. But his lasting significance occurs as the singular concerns of the artist extend into the aleatory, the multiple, and the collaborative. Dance For more than thirty years he has collaborated on over a dozen dance works with Margaret Jenkins and her Dance Company. Early dance scenarios in which Palmer participated include Interferences, 1975; Equal Time, 1976; No One but Whitington, 1978; Red, Yellow, Blue, 1980, Straight Words, 1980; Versions by Turns, 1980; Cortland Set, 1982; and First Figure, 1984. A particularly noteworthy example of a recent Jenkins/Palmer collaboration would be The Gates (Far Away Near), an evening-length dance work in which Palmer worked with not only Ms. Jenkins, but also Paul Dresher and Rinde Eckert. This was performed in September 1993 in the San Francisco Bay Area and in July 1994 at New York’s Lincoln Center. Another recent collaboration with Jenkins resulted in “Danger Orange”, a 45-minute outdoor site-specific performance, presented in October 2004 before the Presidential elections. The color orange metaphorically references the national alert systems that are in place that evoke the sense of danger.[see also:Homeland Security Advisory System] Painters and visual artists Similar to his friendship with Robert Duncan and the painter Jess Collins, Palmer’s work with painter Irving Petlin remains generative. Irving’s singular influence from the beginning demonstrated for Palmer a “working” of the poet as “maker” (in the radical sense, even ancient sense of that word). Along with Duncan, Zukofsky, and others, Petlin’s work modeled, demonstrated, circumscribed and, perhaps most importantly for Palmer, verified that “the way” (this way for the artist who is a maker, a creator) would also be, as Gilles Deleuze termed it, “a life”. This in turn delineates Palmer’s own sense of both a poetics and an ongoing counter-poetic tradition, offering him fixture and a place of repair. Recently he worked with painter and visual artist Augusta Talbot, and curated her exhibition at the CUE Art Foundation (March 17 –April 23, 2005). When asked in an interview how collaboration has pushed the boundaries of his work, Palmer responded: There were a variety of influences. One was that, when I was using language—but even when I wasn’t, when I was simply envisioning a structure, for example—I was working with the idea of actual space. Over time, my own language took on a certain physicality or gestural character that it hadn’t had as strongly in the earliest work. Margy (Margaret Jenkins) and I would often work with language as gesture and gesture as language—we would cross these two media, have them join at some nexus. And inevitably then, as I brought certain characteristics of my work to dance, and to dance structure and gesture, it started crossing over into my work. It added space to the poems. It may be that for Palmer, friendship (acknowledging both the multiple and collaborative), becomes in part what Jack Spicer terms a “composition of the real”. Across the fields of painting and dance, Palmer’s work figures as an “unrelenting tentacle of the proprioceptive”. Furthermore, it may signal a Coming Community underscored in the work of Giorgio Agamben, Jean-Luc Nancy and Maurice Blanchot among others. It is a poetry that would, along with theirs, articulate a place for, even spaces where, both the “poetic imaginary” is constituted and a possible social space is envisioned. As Jean-Luc Nancy has written in The Inoperative Community (1991): “These places, spread out everywhere, yield up and orient new spaces... other tracks, other ways, other places for all who are there.” Bibliography Poetry * Plan of the City of O, Barn Dreams Press (Boston, Massachusetts), 1971. * Blake’s Newton, Black Sparrow Press (Santa Barbara, California), 1972. * C’s Songs, Sand Dollar Books (Berkeley, California), 1973. * Six Poems, Black Sparrow Press (Santa Barbara, California), 1973. * The Circular Gates, Black Sparrow Press (Santa Barbara, California), 1974. * (Translator, with Geoffrey Young) Vicente Huidobro, Relativity of Spring: 13 Poems, Sand Dollar Books (Berkeley, California), 1976. * Without Music, Black Sparrow Press (Santa Barbara, California), 1977. * Alogon, Tuumba Press (Berkeley, California), 1980. * Notes for Echo Lake, North Point Press (Berkeley, California), 1981. * (Translator) Alain Tanner and John Berger, Jonah Who Will Be 25 in the Year 2000, North Atlantic Books (Berkeley, California), 1983. * First Figure, North Point Press (Berkeley, California), 1984. * Sun, North Point Press (Berkeley, California), 1988. * At Passages, New Directions (New York, New York), 1995. * The Lion Bridge: Selected Poems, 1972-1995, New Directions (New York, New York), 1998. * The Promises of Glass, New Directions (New York, New York), 2000. * Codes Appearing: Poems, 1979-1988, New Directions (New York, New York), 2001. Notes for Echo Lake, First Figure, and Sun together in one volume. ISBN 978-0-8112-1470-4 * (With Régis Bonvicino) Cadenciando-um-ning, um samba, para o outro: poemas, traduções, diálogos, Atelieì Editorial (Cotia, Brazil), 2001. * Company of Moths, New Directions (New York, New York), 2005. ISBN 978-0-8112-1623-4 * Aygi Cycle, Druksel (Ghent, Belgium), 2009 (chapbook with 10 new poems, inspired by the Russian poet Gennadiy Aygi. * (With Jan Lauwereyns) Truths of Stone, Druksel (Ghent, Belgium), 2010. * Thread, New Directions (New York, New York), 2011. ISBN 978-0-8112-1921-1 * The Laughter of the Sphinx, New Directions (New York, New York), 2016. ISBN 978-0-8112-2554-0 Other * Idem 1-4 (radio plays), 1979. * (Editor) Code of Signals: Recent Writings in Poetics, North Atlantic Books (Berkeley, California), 1983. * The Danish Notebook, Avec Books (Penngrove, California), 1999—prose/memoir * Active Boundaries: Selected Essays and Talks, New Directions (New York, New York), 2008. ISBN 0-8112-1754-X External links Palmer sites and exhibits * Exhibit at The Academy of American Poets includes links to on-line poems by Palmer not listed below * Modern American Poetry site * Author Page at Internationales Literatufestival Berlin site (in English) Palmer was a guest of the ILB (Internationales Literatufestival Berlin/ Germany) in 2001 and 2005. * An internet bibliography for Michael Palmer from LiteraryHistory.com Poems * “Dream of a Language That Speaks” a poem from Company of Moths (2005) @ Jacket Magazine site * “Scale” first published in Richter 858 (ed. David Breskin, The Shifting Foundation, SF MOMA: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art); included in Company of Moths * "Autobiography 3" & Autobiography 5" two poems from Conjunctions magazine’s on-line archive; included in The Promises of Glass (2000) * To the Title (Are there titles?) included in Jacket Magazine 33 * four poems from Thread from Boston Review’s March/April 2010 issue * Late Night Poetry @ Tony Bilson’s Number One: Palmer reads “The Dream of Narcissus” on YouTube Video of Palmer at the 2010 Sydney (Australia) Writers Festival. * Michael Palmer reads Mahmoud Darwish’s “The Strangers’ Picnic” on YouTube Video of Palmer reading a poem from Mahmoud Darwish’s collection Unfortunately, It Was Paradise: Selected Poems * Michael Palmer, Paul Hoover with the poetry of Maria Baranda - September 27, 2015– Palmer reads from his book Thread and from his forthcoming collection The Laughter of the Sphinx. He also reads a single poem from his collection The Company of Moths. Selected essays and talks * Period (senses of duration) this is a version of a talk Palmer gave in San Francisco in February 1982. Scroll down to “Table of Contents” to find the Palmer selection. Here it appears in an e-book representation of Code of Signals (which Palmer edited in 1983, with the subtitle “Recent Writings in Poetics”). * On Robert Duncan reprint of Palmer’s essay “Robert Duncan and Romantic Synthesis” * Michael Palmer audio-files at PENNsound * “On the Sustaining of Culture in Dark Times” text of Palmer’s keynote address given at the 3rd Annual Sustainable Living Conference at Evergreen State College in February 2004 * “Ground Work: On Robert Duncan” Michael Palmer’s “Introduction” to a combined edition of Ground Work: Before the War, and Ground Work II: In the Dark, published by New Directions in April 2006. * Lunch Poems reading by Michael Palmer: Webcast Held on October 5, 2006, in the Morrison Library, University of California at Berkeley: webcast online * “In Company: On Artistic Collaboration and Solitude” This is the title of the lecture/talk that Palmer gave, along with a poetry reading, at the University of Chicago in October 2006. (In audio & video format) * Bad to the bone: What I learned outside Lecture & Talk given in June 2002, when Palmer taught for a brief stint at the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics at Naropa in Boulder, Colorado * Poetic Obligations (Talking about Nothing at Temple) This is a talk Palmer gave at Temple University in February 1999, and was originally published in Fulcrum: An annual of poetry and aesthetics (Issue 2, 2003). * Poetry and Contingency: Within a Timeless Moment of Barbaric Thought essay/talk originally published in the Chicago Review (June, 2003) Interviews with Palmer * The River City Interview conducted by Paul Naylor, Lindsay Hill, and J. P. Craig; appeared in 1994. * An Interview with Michael Palmer by Robert Hicks in 2006 * Interview at Berkeley Daily Planet: April 7, 2006 discusses a reading Palmer & Douglas Blazek gave together at Moe’s, a bookstore in Berkeley, California; includes interviews * Interview with Michael Palmer an interview conducted at Washington University in St. Louis in 2008 by the student editors of “Arch Literary Journal” in conjunction with a talk and reading Palmer gave at the school. Includes an introductory essay by one of the editors, Lawrence Revard, “'What Reading?': Play in Michael Palmer’s Poetics” * “An interview with Michael Palmer”. Litshow.com. 2013-02-13. Retrieved 2013-04-23. Others on Palmer * Margaret Jenkins Dance Company info on both Palmer & his collaborators in their on-going work with Dance * Lauri Ramey:"Michael Palmer: The Lion Bridge" Ramey wrote a doctoral dissertation on Palmer, and here reviews his “Selected Poems” * A Collision of “Possible Worlds” A 2002 review of The Promises of Glass by Michael Dowdy @Free Verse website * A review of Company of Moths a book review of Palmer’s 2005 collection * Griffin Poetry Prize biography, including audio and video clips Palmer was shortlisted for this prize in 2006 * Margaret Jenkins Dance Company’s “A Slipping Glimpse” 2006 dance piece in collaboration with Tanushree Shankar Dance School & the text by Palmer * Cultural camaraderie article from Hindustantimes.com on the dance performance A Slipping Glimpse. Article discusses Palmer’s collaboration (includes quotes) * Palmer is Spring 2007 Writer in Residence press release from California College of the Arts * Michael Palmer (Six Introductions) a brief essay by Clayton Eshleman who edited Sulfur magazine, for which Palmer served as a contributing editor. * Hands Across Many Seas: From San Francisco and India, a dance collaboration article by Deborah Jowitt on “A Slipping Glimpse”, performed by the Margaret Jenkins Dance Company at the “Danspace Project” at Saint Mark’s Church, October 4 through 6, 2007 * Lyric Persuasions at Poets House Rae Armantrout and Zoketsu Norman Fischer discuss Michael Palmer’s work as recorded by Vasiliki Katsarou at the Poet’s House in the Spring of 2010 References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michael_Palmer_(poet)

Leopoldo Panero Torbado (Astorga, León, 17 de octubre de 1909 – Castrillo de las Piedras, León, 27 de agosto de 1962) fue un poeta español, miembro de la Generación del 36, dentro de la corriente de la Poesía arraigada de posguerra. Fue hermano del poeta Juan Panero (1908–1937) y padre de Juan Luis Panero (1942), Leopoldo María Panero (1948) y Michi Panero (1951–2004), los dos primeros también poetas. Estuvo casado con Felicidad Blanc (1913–1990). Pasó toda su infancia en Astorga; hizo la Enseñanza Media en San Sebastián y León, y estudió Derecho en las Universidades de Valladolid y Madrid; en esta última se licenció. Sus primeros versos los publicó en Nueva Revista, de Madrid, que él mismo fundó y que publicó sus obras Crónica cuando amanece (1929) y Poema de la niebla (1930). En el otoño de 1929 enfermó de tuberculosis y fue a reponerse al Sanatorium Royal de la Sierra de Guadarrama durante ocho meses y se enamoró de otra paciente, Joaquína Márquez, fallecida algunos meses después. Amplió estudios en Cambridge (1932 a 1934) y en Tours y Poitiers (1935), impregnándose de literatura inglesa y francesa. Publicó en Caballo Verde para la poesía, revista dirigida por Pablo Neruda. Durante la Guerra Civil Panero fue arrestado, conducido a San Marcos de León y acusado de recaudar fondos para Socorro Rojo, pero la mediación de su madre, de Miguel de Unamuno y de Carmen Polo, esposa de Francisco Franco, le evitó males mayores y volvió a Astorga en noviembre. En 1937 murió su hermano Juan, también poeta, en un accidente de automóvil, hecho que le hirió profundamente, transformándole en un conservador; sobre este hecho y en su memoria escribió Adolescente en sombra (1938). En el año 1941 se casó con Felicidad Blanc,1 escritora, de la que tuvo tres hijos, Juan Luis (1942), Leopoldo María (1948) y Michi, los dos primeros también poetas. Durante la guerra entró en Falange Española, y después le nombraron agregado cultural a la Embajada española (1939) y director del Instituto Español (1945–1947) en Londres. Allí conoció y trató a alguno de los más insignes exiliados como Luis Cernuda o Esteban Salazar Chapela, director a su vez del otro Instituto de España, dependiente de la República. A finales de 1949 y comienzos de 1950, participó de la "misión poética"2 con los poetas Antonio Zubiaurre, Luis Rosales y el Embajador Agustín de Foxá, que recorrió diferentes países iberoamericanos (entre otros Honduras) previo al restablecimiento de relaciones diplomáticas entre estos países y el régimen de Franco. Publicó una Antología de la poesía hispanoamericana (1941); publicó también en la revista Escorial (1940) de Madrid, especialmente en sus números 5 y 15, y en Garcilaso. Juventud creadora (1943–1946) y en Haz (1944), también de Madrid. Su libro Versos del Guadarrama, inspirado en el amor perdido de Joaquina Márquez, se publicó en Fantasía, suplemento de La Estafeta Literaria (1945), también de Madrid. Pasa grandes temporadas en esta última ciudad, donde frecuenta la tertulia del Café Lyon, donde entabla amistad, entre otros, con Luis Rosales, Luis Felipe Vivanco y Gerardo Diego, tertulia que se fundió más tarde con la de Manuel Machado. En 1949 recibió el Premio Fastenrath de la Academia por su libro Escrito a cada instante, y al año siguiente el Premio Nacional de Literatura. Más tarde publicó en la revista Poesía Española (1952–1971). Dirigió la revista Correo Literario y figuró en (1952) como organizador de las Exposiciones Bienales de Arte. Fue secretario de una sección del Instituto de Cultura Hispánica. En 1960 publicó Cándida puerta, considerada una de sus obras maestras. Murió dos años después. Sus primeros versos experimentan el influjo de la Generación del 27 y de las Vanguardias; hay ecos de las estéticas del dadaísmo y del surrealismo, así como uso de verso libre. Tras la Guerra Civil abandonó estos conatos transgresores y escribió poemas dentro de la estética del garcilasismo, intimistas, en que el concepto se equilibra perfectamente con la emoción y la forma, de temática conservadora y religiosa. Los autores que inspiran esta segunda fase son Miguel de Unamuno y Antonio Machado. Destacan entre sus libros de poemas La estancia vacía (1944), Versos al Guadarrama (1945), Escrito a cada instante (1949), donde aparecen sus famosas elegías a César Vallejo, que estuvo en su casa invitado por él durante unos días, y a Federico García Lorca; Canto personal (1953), réplica al Canto General de Pablo Neruda escrita en tercetos al que puso prólogo Dionisio Ridruejo, que recibió el Premio 18 de Julio de manos del ministro Raimundo Fernández-Cuesta, y Cándida puerta (1960); en el póstumo Poesía (1963) se recoge toda su obra lírica, y sus Obras completas se imprimieron en 1973. Hizo excelentes traducciones de románticos ingleses. Javier Huerta Calvo ha preparado unas segundas Obras completas (2008) en tres volúmenes, dos de poesía y uno de prosa, por encargo del Ayuntamiento de Astorga, que recogen algunos textos más que las de 1973. Murió en su casa de Castrillo de las Piedras, tras sufrir una angina de pecho mientras regresaba en su vehículo. Poesía * La estancia vacía (fragmentos), M., Revista Fantasía, 1945. * Versos del Guadarrama. Poesía 1930–1939, M., Revista Fantasía, 1945. * Escrito a cada instante, M., Cultura hispánica, 1949 (Premio Nacional de Literatura). * Canto personal. Carta perdida a Pablo Neruda, M., Cultura hispánica, 1953. * Poesía. 1932–1960, M., Cultura Hispánica, 1963 (Prólogo de Dámaso Alonso). * Obra completa, M., Edit. Nacional, 1973. ISBN 978-84-276-1119-1 * Antología de Leopoldo Panero, Barcelona, Plaza & Janés Editores, 1977. ISBN 978-84-01-80928-6 * Por donde van las águilas, Albolote, Editorial Comares, S. L., 1994, ISBN 978-84-8151-098-0 Referencias wikipedia - http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leopoldo_Panero

Joseph Mary Plunkett (Irish: Seosamh Máire Pluincéid, 21 November 1887– 12 May 1916) was an Irish nationalist, poet, journalist, and a leader of the 1916 Easter Rising. He was born at 26 Upper Fitzwilliam Street in one of Dublin’s most affluent neighbourhoods. Both his parents came from wealthy backgrounds, and his father, George Noble Plunkett, had been made a papal count. Despite being born into a life of privilege, young Joe Plunkett did not have an easy childhood.

Rosario Sansores Prén (Mérida, Yucatán; 25 de agosto de 1889 — Ciudad de México; 7 de enero de 1972) fue una poetisa mexicana, conocida por obras como "Cuando tú te hayas ido", poema que sirvió de base al pasillo "Sombras", musicalizado por el compositor ecuatoriano Carlos Brito Benavides. Nació en un hogar acaudalado, hija de Juan Ignacio Sansores Escalante y Laura Prén Cámara, quienes intentaron disuadirla de escribir poesía a corta edad. A los catorce años de edad se casó con el cubano Antonio Sangenis y se mudó a La Habana, donde viviría por veintitrés años. Durante el tiempo que vivió en Cuba se dedicó a escribir artículos sobre temas sociales en periódicos y revistas. En 1911 empezó a publicar sus libros de poesía, la mayoría firmados con seudónimos

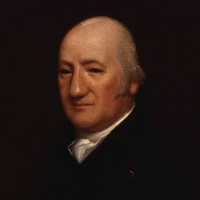

Henry James Pye (/paɪ/; 10 February 1744– 11 August 1813) was an English poet. Pye was Poet Laureate from 1790 until his death. He was the first poet laureate to receive a fixed salary of £27 instead of the historic tierce of Canary wine (though it was still a fairly nominal payment; then as now the Poet Laureate had to look to extra sales generated by the prestige of the office to make significant money from the Laureateship). Life Pye was born in London, the son of Henry Pye of Faringdon House in Berkshire, and his wife, Mary James. He was the nephew of Admiral Thomas Pye. He was educated at Magdalen College, Oxford. His father died in 1766, leaving him a legacy of debt amounting to £50,000, and the burning of the family home further increased his difficulties. In 1784 he was elected Member of Parliament for Berkshire. He was obliged to sell the paternal estate, and, retiring from Parliament in 1790, became a police magistrate for Westminster. Although he had no command of language and was destitute of poetic feeling, his ambition was to obtain recognition as a poet, and he published many volumes of verse. Of all he wrote his prose Summary of the Duties of a Justice of the Peace out of Sessions (1808) is most worthy of record. He was made poet laureate in 1790, perhaps as a reward for his faithful support of William Pitt the Younger in the House of Commons. The appointment was looked on as ridiculous, and his birthday odes were a continual source of contempt. The 20th century British historian Lord Blake called Pye “the worst Poet Laureate in English history with the possible exception of Alfred Austin.” Indeed, Pye’s successor, Robert Southey, wrote in 1814: “I have been rhyming as doggedly and dully as if my name had been Henry James Pye.” After his death, Pye remained one of the unfortunate few who have been classified as a “poetaster.” As a prose writer, Pye was far from contemptible. He had a fancy for commentaries and summaries. His “Commentary on Shakespeare’s commentators”, and that appended to his translation of the Poetics, contain some noteworthy matter. A man, who, born in 1745, could write “Sir Charles Grandison is a much more unnatural character than Caliban,” may have been a poetaster but was certainly not a fool. He died in Pinner, Middlesex on 11 August 1813. Pye married twice. He had two daughters by his first wife. He married secondly in 1801 Martha Corbett, by whom he had a son Henry John Pye, who in 1833 inherited the Clifton Hall, Staffordshire estate of a distant cousin and who was High Sheriff of Staffordshire in 1840. Works Prose * Summary of the Duties of a Justice of the Peace out of Sessions (1808) * The Democrat (1795) * The Aristocrat (1799) Poetry * Poems on Various Subjects (1787), first substantial collection of Pye’s verse * Adelaide: a Tragedy in Five Acts (1800) * Alfred (1801) Translations * Aristotle’s Poetics (1792) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_James_Pye