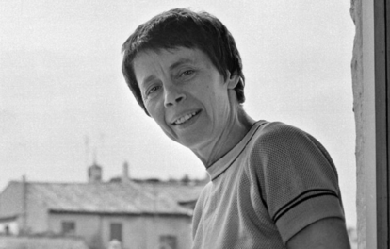

Marilina Rébora Fue una poeta y prosista Argentina. Estudió dibujo y pintura junto a Ernesto Riccio, Vicente Puig, Susana Aguirre y Horacio Butler. Expuso sus obras en diversos salones y se halla representada en museos argentinos. Paralelamente desarrolló su carrera literaria. Sus primeros poemas datan de 1936, 1937 y 1938. Publicó los libros "Los días de los días" (1969), "Libro de estampas" (1972), "El Río Azul" (1975), "Tiempos de la vida" (1975), "Las confidencias" (1978), "Animalerías" (1980) y "El lagarto estaba harto" (1986). Dejó más de veinte obras inéditas. Marilina fue una poeta solitaria que a lo largo de su vida huyó de la estridencia bulliciosa y la difundida notoriedad, pero, en cambio, cultivó devotamente su mundo interior y su opulenta imaginación

I'm just another person trying to spread this art in the form of words to convey an imagine that can't be seen but only heard. Don't expect a traditional poem cause my writing has no structure Hope you enjoy reading my work, please feel free to leave comments good or bad! I would love to hear what you all think of it.

Luis Rosales Camacho (Granada, 31 de mayo de 1910 – Madrid, 24 de octubre de 1992) fue un poeta y ensayista español de la generación de 1936, nacido en el seno de una familia muy conservadora. fue miembro de la Real Academia Española y de la Hispanic Society of America desde 1962 y obtuvo el Premio Cervantes en 1982 por el conjunto de su obra literaria.

Dosártes nació en Ilobasco. Hijo del trópico y bibliófilo empedernido, ha publicado siete poemarios hasta la fecha. Sus proyectos más recientes son: «Volcánica», «Solaz sobre las nubes» y «Labios de ángel». Actualmente, se dedica enteramente a la literatura. Vive entre Los Ángeles y El Zonte. Lea más en https://amazon.com/author/dosartes © ¡Más amor, más gemidos! Instagram: @julianriveiradosartes riveiraderimas.blogspot.com/ #RiveiradeRimas

Kathleen Jessie Raine CBE (14 June 1908– 6 July 2003) was a British poet, critic and scholar, writing in particular on William Blake, W. B. Yeats and Thomas Taylor. Known for her interest in various forms of spirituality, most prominently Platonism and Neoplatonism, she was a founder member of the Temenos Academy. Life Kathleen Raine was born in Ilford, Essex (now part of London). Her mother was from Scotland and her father was born in Wingate, County Durham. The couple had met as students at Armstrong College in Newcastle upon Tyne. Raine spent part of World War I, 'a few short years’, with her Aunty Peggy Black at the Manse in Great Bavington Northumberland. She commented, “I loved everything about it.” For her it was an idyllic world and is the declared foundation of all her poetry. Raine always remembered Northumberland as Eden: “In Northumberland I knew myself in my own place; and I never 'adjusted’ myself to any other or forgot what I had so briefly but clearly seen and understood and experienced.” This period is described in the first book of her autobiography, Farewell Happy Fields (1973). Raine noted that poetry was deeply ingrained in the daily lives of her maternal ancestors: "On my mother’s side I inherited Scotland’s songs and ballads…sung or recited by my mother, aunts and grandmothers, who had learnt it from their mothers and grandmothers… Poetry was the very essence of life." Raine heard and read the Bible daily at home and at school, coming to know much of it by heart. Her father was an English master at County High School in Ilford. He had studied the poetry of Wordsworth for his M.Litt thesis and had a passion for Shakespeare and Raine saw many Shakespearean plays as a child. From her father she gained a love of etymology and the literary aspect of poetry, the counterpart to her immersion in the poetic oral traditions. She wrote that for her poetry was "not something invented but given…Brought up as I was in a household where poets were so regarded it naturally became my ambition to be a poet". She confided her ambition to her father who was sceptical of the plan. “To my father” she wrote “poets belonged to a higher world, to another plane; to say one wished to become a poet was to him something like saying one wished to write the fifth gospel”. Her mother encouraged Raine’s poetry from babyhood. Raine was educated at County High School, Ilford, and then read natural sciences, including botany and zoology, on an Exhibition at Girton College, Cambridge, receiving her master’s degree in 1929. While in Cambridge she met Jacob Bronowski, William Empson, Humphrey Jennings and Malcolm Lowry. In later life she was a friend and colleague of the kabbalist author and teacher, Z’ev ben Shimon Halevi. Raine married Hugh Sykes Davies in 1930. She left Davies for Charles Madge and they had two children together, but their marriage also broke up. She also held an unrequited passion for Gavin Maxwell. The title of Maxwell’s most famous book Ring of Bright Water, subsequently made into a film of the same name starring Virginia McKenna, was taken from a line in Raine’s poem “The Marriage of Psyche”. The relationship with Maxwell ended in 1956 when Raine lost his pet otter, Mijbil, indirectly causing the animal’s death. Raine held herself responsible, not only for losing Mijbil but for a curse she had uttered shortly beforehand, frustrated by Maxwell’s homosexuality: “Let Gavin suffer in this place as I am suffering now.” Raine blamed herself thereafter for all Maxwell’s misfortunes, beginning with Mijbil’s death and ending with the cancer from which he died in 1969. From 1939 to 1941, Raine and her children shared a house at 49a Wordsworth Street in Penrith with Janet Adam Smith and Michael Roberts and later lived in Martindale. She was a friend of Winifred Nicholson. Raine’s two children were Anna Hopwell Madge (born 1934) and James Wolf Madge (1936–2006). In 1959, James married Jennifer Alliston, the daughter of Raine’s friend, architect and town planner Jane Drew with architect James Alliston. Drew was a direct descendant of the neoplatonist Thomas Taylor whom Raine studied and wrote about. Thus a link was made between Raine and Taylor by the two children of her son’s marriage. At the time of her death, following an accident, Raine resided in London.

Sir Charles George Douglas Roberts, KCMG FRSC (January 10, 1860– November 26, 1943) was a Canadian poet and prose writer who is known as the Father of Canadian Poetry. He was “almost the first Canadian author to obtain worldwide reputation and influence; he was also a tireless promoter and encourager of Canadian literature. He published numerous works on Canadian exploration and natural history, verse, travel books, and fiction.” “At his death he was regarded as Canada’s leading man of letters.” Besides his own body of work, Roberts is also called the “Father of Canadian Poetry” because he served as an inspiration and a source of assistance for other Canadian poets of his time. Roberts, his cousin Bliss Carman, Archibald Lampman and Duncan Campbell Scott are known as the Confederation Poets. Life Roberts was born in Douglas, New Brunswick in 1860, the eldest child of Emma Wetmore Bliss and Rev. George Goodridge Roberts (an Anglican priest). Rev. Roberts was rector of Fredericton and canon of Christ Church Cathedral, New Brunswick. Charles’s brother Theodore Goodridge Roberts and sister, Jane Elizabeth Gostwycke Roberts, would also become authors. Between the ages of 8 months and 14 years, Roberts was raised in the parish of Westcock, New Brunswick, near Sackville, by the Tantramar Marshes. He was homeschooled, “mostly by his father, who was proficient in Greek, Latin and French.” He published his first writing, three articles in The Colonial Farmer, at 12 years of age. After the family moved to Fredericton in 1873, Roberts attended Fredericton Collegiate School from 1874 to 1876, and then the University of New Brunswick (UNB), earning his B.A. in 1879 and M.A. in 1881. At the Collegiate School he came under the influence of headmaster George Robert Parkin, who gave him a love of classical literature and introduced him to the poetry of Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Algernon Charles Swinburne. Roberts was principal of Chatham High School in Chatham, New Brunswick, from 1879 to 1881, and of York Street School in Fredericton from 1881 to 1883. In Chatham he met and befriended Edmund Collins, editor of the Chatham Star and the future biographer of Sir John A. Macdonald. Early Canadian career Roberts first published poetry in the Canadian Illustrated News of March 30, 1878, and by 1879 he had placed two poems in the prestigious American magazine, Scribner’s. In 1880, Roberts published his first book of poetry, Orion and Other Poems. Thanks in part to his industry in sending out complimentary review copies, there were many positive reviews. Rose-Belford’s Canadian Monthly proclaimed: “Here is a writer whose power and originality it is impossible to deny—here is a book of which any literature might be proud.” The Montreal Gazette predicted that Roberts would “confer merited fame on himself and lasting honour on his country.” As well, “several American periodicals reviewed it favourably, including the New York Independent, which described it as ‘a little book of choice things, with the indifferent things well weeded out.’” On December 29, 1880, Roberts married Mary Fenety, who would bear him five children. The biography by Roberts’s friend Edmund Collins, The Life and Times of Sir John A. Macdonald, was published in 1883. The book was a huge success, going through eight printings. It contained a long chapter on “Thought and Literature in Canada,” which devoted 15 pages to Roberts, quoting liberally from Orion. “Beyond any comparison,” Collins declared, “our greatest Canadian poet is Mr. Charles G.D. Roberts.” “Edmund Collins is probably responsible for the early acceptance of Charles G.D. Roberts as Canada’s foremost poet.” From 1883 to 1884, Roberts was in Toronto, Ontario, working as the editor of Goldwin Smith’s short-lived literary magazine, The Week. “Roberts lasted only five months at The Week before resigning in frustration from overwork and clashes with Smith.” In 1885, Roberts became a professor at the University of King’s College in Windsor, Nova Scotia. In 1886, his second book, In Divers Tones, was published by a Boston publisher. "Over the next six years, in addition to his academic duties, Roberts published more than thirty poems in numerous American periodicals, but mostly in The Independent while Bliss Carman was on its editorial staff. During the same period, he published almost an equal number of stories, primarily for juvenile readers, in periodicals like The Youth’s Companion. He also edited Poems of Wild Life (1888), completed a 270-page Canadian Guide Book (1891), wrote about a dozen articles on a variety of topics, and gave lectures in various centres from Halifax to New York.” Roberts was asked to edit the anthology, Songs of the Great Dominion, but that position eventually went to W.D. Lighthall. Lighthall included a generous selection of Roberts’s work, and echoed Collins’s assessment of six years earlier: “The foremost name in Canadian song at the present day is that of Charles George Douglas Roberts.” Roberts resigned from King’s College in 1895, when his request for a leave of absence was turned down. Determined to make a living from his pen, in 1896 “he published his first novel, The Forge in the Forest,... his fourth collection of poetry, The Book of the Native,... his first book of nature-stories, Earth’s Enigmas,... and a book of adventure stories for boys, Around the Campfire.” Move to New York In 1897, Roberts left Canada, as well as his wife and children, for New York City so that he may work free-lance. Between 1897 and 1898, he worked for The Illustrated American as an associate editor. In New York, Roberts wrote in many different genres, but found that "his most successful prose genre was the animal story, in which he drew upon his early experience in the wilds of the Maritimes. He published over a dozen such volumes between Earth’s Enigmas (1896) and Eyes of the Wilderness (1933).... Roberts is remembered for creating in the animal story, along with Ernest Thompson Seton, the one native Canadian art form.” Roberts also wrote historical romances and novels. "Barbara Ladd (1902) begins with a girl escaping from an uncongenial aunt in New England in 1769; it sold 80,000 copies in the US alone." He also wrote descriptive text for guide books, such as Picturesque Canada and The Land of Evangeline and Gateways Thither for Nova Scotia’s Dominion Atlantic Railway. Roberts famously became involved in a literary debate known as the nature fakers controversy after John Burroughs denounced his popular animal stories, and those of other writers, in a 1903 article for Atlantic Monthly. The controversy lasted for nearly six years and included important American environmental and political figures of the day, including President Theodore Roosevelt. Europe and return to Canada In 1907, Roberts moved to Europe. First living in Paris, he moved to Munich in 1910, and in 1912 to London, where he lived until 1925. During World War I he enlisted with the British Army as a trooper, eventually becoming a captain and a cadet trainer in England. After the war he joined the Canadian War Records Office in London. Roberts returned to Canada in 1925 which “led to a renewed production of verse.” During the late 1920s he was a member of the Halifax literary and social set, The Song Fishermen. He married his second wife Joan Montgomery on October 28, 1943, at the age of 83, but became ill and died shortly thereafter in Toronto. The funeral was held in Toronto, but his ashes were returned to Fredericton, where he was interred in Forest Hill Cemetery. Poetry Orion and Other Poems Roberts’s first book, Orion and Other Poems (1880), was a vanity book for which he had to "pay an advance of $300, most of which he borrowed from George E. Fenety, the Queen’s Printer for New Brunswick, soon to become his father-in-law." Orion was “a collection of juvenilia, written while the poet was still a teenager.” In 1958, the critic Desmond Pacey wrote that “when we remind ourselves that it was published when the poet was twenty... we realize that it is a remarkable performance. It is imitative, naively romantic, defective in diction, the poetry of books rather than life itself, but it is facile, clever, and occasionally distinctly beautiful.... It is the work of an apprentice, who is quite frankly serving under a sequence of masters from whom he hopes to learn his art.” In Divers Tones The title of Roberts’s second book, In Divers Tones "aptly describes the hodgepodge of its contents. The selections vary greatly, not only in style and subject matter, but also in quality.... Among those written between 1883 and 1886... there is evidence of a maturing talent. In fact, it might be argued that at least three of these poems, ‘The Tantramar Revisited,’ ‘The Sower,’ and 'The Potato Harvest,” were never surpassed by any of his subsequent verse.” Songs of the Common Day By the time of Songs of the Common Day, and Ave! (1893), Roberts "had reached the height of his poetic powers.... It is the sonnet sequence of Songs of the Common Day that has established Roberts’ reputation as a landscape poet.... Evidence of the Tantramar setting occurs in lines like “How sombre slope these acres to the sea’ ('The Furrow”), 'These marshes pale and meadows by the sea’ ('The Salt Flats’), and 'My fields of Tantramar in summer-time’ ('The Pea-Fields’). The descriptions are full of evocative details.” Middle period After Roberts turned to free-lance writing in 1895, “Financial pressure forced him to turn his main attention to fiction.” He published two more books of poetry by 1898, but managed only two more in the following 30 years. “As their titles often indicate, the numerous seasonal poems in The Book of the Native (1897) were written with an eye on the monthly requirements of the magazines: ‘The Brook in February,’ ‘An April Adoration,’ ‘July,’ and ‘An August Woodroad.’ Roberts “is generally at his best in the poems in which he depicts these seasonal stages of nature with the palette of a realistic landscape painter.” However, the book also “signalled a shift in his poetic oeuvre away from descriptive, technically tight Romantic verses to more mystical lyrics.” “Most of the nature poetry in Roberts’s New York Nocturnes and Other Poems (1898) was written before he moved to New York. It belongs to a period of upheaval, desperation and overwork, which may at least partly account for its disappointing slackness.... Even ‘The Solitary Woodsman,’ much anthologized and frequently praised, is a series of unremarkable images made tedious by fifty-two lines of irritating rhythm and rhyme.... Roberts seldom looks at New York with the eye of a painter, and never captures its essence with the effectiveness he displays in his best pictures of rural landscape.... Instead of turning an inquiring eye upon urban conditions, he is inclined to retreat from “'he city’s fume and stress’ and 'clamour’ ('The Ideal’).". The first and title section of The Book of the Rose (1903) was a collection of love poetry. "Roberts handling of the symbol sounds artificial at best and sometimes downright fatuous.... Although most of the poems in the second section are unimpressive, there are a few exceptions. “Heat in the City,” noteworthy for being the best poem he ever wrote about city life, effectively evokes the distress and despair of the tenement-dwellers.... The final poem in the book, “The Aim,” is remarkable for its frank self-analysis.” “New Poems, a slim volume published in 1919, shows the drop in both the quantity and quality of Roberts’ poetry during his European years. At least half of the pieces had been written before he left America, some as early as 1903.” Later poems Roberts’s "return to Canada in 1925 led to a renewed production of verse with The Vagrant of Time (1927) and The Iceberg and Other Poems (1934)." Literary critic Desmond Pacey calls this period “the Indian summer of his poetic career”. “Among the best of the new poems” in The Vagrant of Time "is the one with this inspired opening line: ‘Spring breaks in foam along the blackthorn bough.’ In another love poem, ‘In the Night Watches,’ written in 1926, his command of free verse is natural and unstrained, unlike the laboured language and forced rhymes of his earlier love poetry. Its synthesis of lonely wilderness setting with feelings of separation and longing is harmonious and poignant.” “Most critics rank ”The Iceberg" (265 lines), the title poem of the new collection" published in 1934, "as one of Roberts’ outstanding achievements. It is almost as ambitious as ‘Ave!’ in conception; its cold, unemotional images are as apt and precise in their detached way as the warmly-remembered descriptions in ‘Tantramar Revisited.’ Animal stories The Canadian Encyclopedia says that “Roberts is remembered for creating in the animal story, along with Ernest Thompson Seton, the one native Canadian art form.” A typical Roberts animal story is “The Truce”. In his introduction to The Kindred of the Wild (1902), Roberts called the animal story "a potent emancipator. It frees us for a little from the world of shop-worn utilities, and from the mean tenement of self of which we do well to grow weary. It helps us to return to nature, without requiring that we at the same time return to barbarism. It leads us back to the old kinship of earth, without asking us to relinquish by way of toll any part of the wisdom of the ages, any fine essential of the ‘large result of time.’ (Kindred 28)” Critical interest in Roberts’s animal stories "emerged in the 1960s and 70s in the growth of what we now know as Canadian Literary Studies.... But these critics tended as a group to see in the animal stories a masked reference to Canadian nationhood: James Polk 'attempts to subsume the animal genre entirely within the identity crisis of an emerging nation […seeing] the sympathetic stance of Seton and Roberts towards the sometimes brutal fate of the “lives of the hunted” as a larger political allegory for Canada’s “victim” status as an American satellite. (Sandlos 74)'” Margaret Atwood devotes a chapter of her 1971 critical study Survival: A Thematic Guide to Canadian Literature to animal stories, where she states the same thesis: "the stories are told from the point of view of the animal. That’s the key: English animal stories are about the ‘social relations,’ American ones are about people killing animals; Canadian ones are about animals being killed, as felt emotionally from inside the fur and feathers. (qtd. in Sandlos 74; emphasis in original).” Recognition Charles G. D Roberts was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada in 1893. Roberts was elected to the United States National Institute of Arts and Letters in 1898. He was awarded an honorary LLD from UNB in 1906, and an honorary doctorate from Mount Allison University in 1942. For his contributions to Canadian literature, Roberts was awarded the Royal Society of Canada’s first Lorne Pierce Medal in 1926. On June 3, 1935, Roberts was one of three Canadians on King George V’s honour list to receive a knighthood (Knight Commander of the Order of St. Michael and St. George). Roberts was honoured by a sculpture erected in 1947 on the UNB campus, portraying him with Bliss Carman and fellow poet Francis Joseph Sherman. “In the 1980s,—a hundred years after his first volumes appeared—a major Roberts revival took place, producing monographs, a complete edition of his poems, a new biography, a collection of his letters, etc. A Roberts Symposium at Mount Allison University (1982) and another at the University of Ottawa (1983) included several scholarly reappraisals of his poetry.” Roberts was declared a Person of National Historic Significance in 1945, and a monument to him was erected by the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada in Westcock in 2005. Publications Poetry * Orion, and Other Poems. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: J. B. Lippincott & Co. 1880. ; also: “Orion, and Other Poems”. Canadian Poetry Press. ; Orion, and Other Poems at Google Books * In Divers Tones. Boston, Massachusetts: D. Lothrop and Company. 1886. ; also: “In Divers Tones”. Canadian Poetry Press. ; In Divers Tones at Google Books * AVE! An Ode for the Shelley Centenary. Toronto: Williamson, 1892. * Songs of the Common Day and, AVE! An Ode for the Shelley Centenary. Toronto, Ontario: William Briggs. 1893. ; Songs of the Common Day and, AVE! An Ode for the Shelley Centenary at Google Books * The Book of the Native. Toronto, Ontario: Copp Clark. 1896. * New York Nocturnes and Other Poems. Boston, Massachusetts: Lamson Wolffe. 1898. * Poems. New York: Silver, Burdett, 1901. * The Book of the Rose. Boston, Massachusetts: L. C. Page & Company. 1903. ; The Book of the Rose at Google Books * New Poems. London: Constable. 1919. * The Sweet o’ the Year and Other Poems. Toronto, Ontario: Ryerson. 1925. ; The Sweet o’ the Year and Other Poems at Google Books * The Vagrant of Time. Toronto, Ontario: Ryerson. 1927. ; The Vagrant of Time at Google Books * The Iceberg and Other Poems Selected Poems of Sir Charles G.D. Roberts. 1934. * Selected Poems of Sir Charles G.D. Roberts. Toronto, Ontario: Ryerson. 1936. * Flying Colours. Miami, Florida: Granger Books. 1942. * Pacey, Desmond, ed. (1955). The Selected Poems of Charles G.D. Roberts. Toronto, Ontario: Ryerson. * Keith, W.J., ed. (1974). Selected Poetry and Critical Prose. Toronto, Ontario: University of Toronto Press. * Pacey, Desmond; Adams, Graham, eds. (1985). Collected Poems of Sir Charles G.D. Roberts. Wolfville, Nova Scotia: Wombat Press. Fiction * The Raid from Beauséjour and How the Carter Boys Lifted the Mortgage. New York: Hunt & Eaton. 1894. ; The Raid from Beausejour and How the Carter Boys Lifted the Mortgage at Google Books * Reube Dare’s Shad Boat: A Tale of the Tide Country. New York: Hunt & Eaton. 1895. ; Reube Dare’s Shad Boat - A Tale of the Tide Country at Google Books * Around the Campfire. Toronto: Musson Book Co. 1896. * Earth’s Enigmas. Boston: Lamson, Wolffe. 1896. ; Earth’s Enigmas: A Volume of Stories at Google Books * The Forge in the Forest. Boston: Lamson, Wolffe. 1896. * By the Marshes of Minas. Boston: Silver, Burdett and Company. 1900. * A Sister to Evangeline. Boston: Silver, Burdett and Company. 1900. * The Feet of the Furtive. London: Ward, Lock & Co. 1900. * The Heart of the Ancient Wood. Boston: L. C. Page & Company. 1902. * The Haunters of the Silences: A Book of Animal Life. London: Thomas Nelson. 1900. * Barbara Ladd. Boston: The Page Company. 1902. * The Kindred of the Wild. Boston: The Page Company. 1902. ; The Kindred of the Wild: A Book of Animal Life at Google Books * The Prisoner of Mademoiselle: A Love Story. Boston: L.C. Page. 1904. * The Watchers of the Trails. Toronto: Copp Clark. 1904. * Red Fox. Boston: L. C. Page & Company. 1905. * The Watchers of the Campfire. Boston: L.C. Page & Company. 1906. * The Heart That Knows. Boston: L.C. Page & Company. 1906. * The Cruise of the Yacht “Dido”: A Tale of the Tide Country. Boston: L.C. Page & Company. 1906. * The Little People of the Sycamore. Charles Livingston Bull illus. Boston: L.C. Page & Company. 1906. * The Return to the Trails. Charles Livingston Bull illus. Boston: L.C. Page & Company. 1906. * In the Deep of the Snow. New York: T.Y. Crowell. 1907. * The Young Acadian Boston. Boston: L.C. Page & Company. 1907. * The Haunters of the Silences. Boston: L.C. Page & Company. 1907. * The House in the Water. Boston: L.C. Page & Company. 1908. * The Backwoodsmen. New York: Macmillan. 1909. * Kings in Exile. New York: Macmillan. 1910. * Neighbours Unknown. London: Ward, Lock & Co. 1910. * More Kindred of the Wild. London: Ward, Lock & Co. 1911. * Babes of the Wild. Warwick Reynolds, illus. London: Cassell. 1912. * Children of the Wild. Paul Bramson, illus. New York: Macmillan. 1913. * A Balkan Prince. London: Everett & Co. 1913. * Hoof and Claw (reprint ed.). New York: Macmillan. 1920 [1914]. * The Secret Trails. New York: Macmillan. 1916. * The Ledge on Bald Face. London: Ward, Lock, & Co. 1918. * In the Morning of Time. New York: Frederick A. Stokes. 1919. * Wisdom of the Wilderness. Read Books. 2013 [1923]. ISBN 978-1-4733-0956-2. * They Who Walk in the Wilds. Read Books. 2013 [1924]. ISBN 978-1-4733-1140-4. * Eyes of the Wilderness. New York: Macmillan. 1933. * Further Animal Stories. Dent. 1935. * The Last Barrier and Other Stories. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. 1970. * Ware, Martin, ed. (1992). The Vagrants of the Barren and Other Stories of Charles G.D. Roberts. Ottawa, Ontario: Tecumseh. ISBN 978-0-9196-6235-3. Non-fiction * A History of Canada. Boston, Massachusetts: The Page Company. 1897. * The Canadian Guide-Book: The Tourist’s and Sportsman’s Guide to Eastern Canada and Newfoundland. New York: D. Appleton 1891. * Discoveries and Explorations in the Century. London: Linscott. 1906. * Canada in Flanders (1918)– non-fiction Edited * Poems of Wild Life. London: W. Scott, 1888. * Canada Speaks of Britain and Other Poems of the War. Toronto: Ryerson, 1941. Papers * Sir Charles G. D. Roberts papers. Charles George Douglas Roberts; Linda Dumbleton; Rose Mary Gibson. Kingston: Queen’s University Archives, {c.1983}. * The Collected Letters of Sir Charles G.D. Roberts. Fredericton, NB: Goose Lane, 1989. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_G._D._Roberts

Hey y'all! I'm Samantha, I am 22 years old and getting ready to graduate from LSU. When it comes to writing my passion is poetry. I have been writing poems since my freshman year of high school. Poetry is my escape and my way of venting. I love to travel! My dream job would be to write for a travel magazine and this way I could travel the rest of my life and experience all the world has to offer. Not only have a posted a few of my poems, but I have written and posted some of my travel pieces from my recent trip to Europe. I hope y'all enjoy reading my work!

Isaac Rosenberg (25 November 1890– 1 April 1918) was an English poet and artist. His Poems from the Trenches are recognized as some of the most outstanding poetry written during the First World War. Early life Isaac Rosenberg was born in Bristol, the second of six children and the eldest son of his parents (his twin brother died at birth), Barnett (formerly Dovber) and Hacha Rosenberg, who were Lithuanian Jewish immigrants to Great Britain from Dvinsk (now in Latvia). In 1897, the family moved to Stepney, a poor district of the East End of London, and one with a strong Jewish community. Isaac Rosenberg attended St. Paul’s Primary School at Wellclose Square, St George in the East parish. Later, he went to the Baker Street Board School in Stepney, which had a strong Jewish presence. In 1902, he received a good conduct award and was allowed to take classes at the Arts and Crafts School in Stepney Green. In December 1904, he left the Baker Street School, and in January 1905, started an apprenticeship with Carl Hentschel, an engraver from Fleet Street. He became interested in both poetry and visual art, and started to attend evening classes at Birkbeck College. He withdrew from his apprenticeship in January 1911, as he had managed to find the finances to attend the Slade School of Fine Art at University College, London (UCL). During his time at Slade School, Rosenberg notably studied alongside David Bomberg, Mark Gertler, Stanley Spencer, Paul Nash, Edward Wadsworth, Dora Carrington, William Roberts, and Christopher Nevinson. He was taken up by Laurence Binyon and Edward Marsh, and began to write poetry seriously, but he suffered from ill-health. He published a pamphlet of ten poems, Night and Day, in 1912. He also exhibited paintings at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1914. Afraid that his chronic bronchitis would worsen, Rosenberg hoped to cure himself by relocating in 1914 to the warmer climate of South Africa, where his sister Mina lived in Cape Town. The Jewish Educational Aid Society of London helped by paying the fare. After arriving in Cape Town in the end of June 1914, he composed a poem On Receiving News of the War. While many wrote about war as patriotic sacrifice, Rosenberg was critical of it from the onset. However, feeling better and hoping to find employment as an artist in Britain, Rosenberg returned home in March 1915. He published a second collection of poems, Youth and then after being unable to find a permanent job enlisted in the British Army at the end of October 1915. He asked that half of his pay was sent to his mother. In a personal letter, Rosenberg described his attitude towards war, “I never joined the army for patriotic reasons. Nothing can justify war. I suppose we must all fight to get the trouble over.” First World War Rosenberg was assigned to the 12th Bantam Battalion of the Suffolk Regiment, a bantam being a designation for men under the usual minimum height of 5'3". After turning down an offer to apply for a commission to become a lance corporal, Rosenberg was transferred, first, to the South Lancashire Regiment, then, to the The King’s Own Royal Lancaster Regiment. In June 1916, he was sent with his unit to serve on the Western Front in France, where he arrived on the 3rd of June. He continued to write poetry while serving in the trenches, including Break of Day in the Trenches, Returning we Hear the Larks, and Dead Man’s Dump. In December 1916, the Poetry Magazine published his two poems. In January 1917, Rosenberg reported sick and his family and friends asked his superiors to remove him from the front lines; he was transferred to the Fortieth Division Works Battalion and started to deliver barbed wire to the trenches. He wrote his poem Dead Man’s Dump during this period. In June, he was temporarily assigned to the 229 Field Company, Royal Engineers. In September 1916, he spent ten days in London on leave. After returning to his old unit, he fell sick in October and spent two months in the 51st General Hospital. After release, he was transferred to the 1st Battalion of King’s Own Royal Regiment (KORL). He applied for a transfer to the one of all-Jewish battalions formed in Mesopotamia, but historians have been unable to track his application. On March 21, 1918, the German Army started its Spring offensive on the Western Front. A week later, Rosenberg sent his last letter with a poem Through these Pale Cold Days to England before going to the front lines with reinforcements. Having just finished night patrol, he was killed on the night of the April 1, 1918 with another 10 KORL’s soldiers; there is a dispute as to whether his death occurred at the hands of a sniper or in close combat. In either case, he died in a town called Fampoux, north-east of Arras. He was first buried in a mass grave, but in 1926, the unidentified remains of the six KORL’s soldiers were individually re-interred at Bailleul Road East Cemetery, Plot V, Saint-Laurent-Blangy, Pas de Calais, France. The Rosenberg’s gravestone is marked with his name and the words, “Buried near this spot”, as well as—"Artist and Poet". Legacy His self-portraits hang in the National Portrait Gallery and Tate Britain. A commemorative blue plaque to him hangs outside the Whitechapel Gallery, formerly the Whitechapel Library, which was unveiled by Anglo-Jewish writer Emanuel Litvinoff. On 11 November 1985, Rosenberg was among 16 Great War poets who were commemorated on a slate stone unveiled in Westminster Abbey’s Poet’s Corner. The inscription on the stone was written by a fellow Great War poet, Wilfred Owen. It reads: “My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity.” Rosenberg appears in the novel Grosse Fugue by Ian Phillips. In The Great War and Modern Memory, Paul Fussell’s landmark study of the literature of the First World War, Fussell identifies Rosenberg’s “Break of Day in the Trenches” as “the greatest poem of the war.” References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isaac_Rosenberg

En los inicios del siglo XX Europa miraba el futuro con actitud desafiante porque creía tener en sus manos la fórmula del progreso indefinido que llevaría necesariamente a un mundo feliz; estaban a la vuelta de la esquina los horrores de la Gran Guerra que la sacudirían hasta sus cimientos. En esos mismos años Bolivia vivía la amargura de la experiencia del Tratado de 1904 y la angustia de conectarse con el mundo exterior. Los cruceños, mientras tanto, lanzaban el Memorándum de 1904 que se convierte en el primer llamado para que Santa Cruz de la Sierra —´capital del espejo y de la música´, uno de los tantos nombres que le dio Otero— se incorpore a la vida nacional. La vida de Otero Reiche (1906-1976) acompaña este largo y doloroso proceso de incorporación y lo siembra con la belleza de la palabra que ayuda a los cruceños a mejor conocer y amar su ciudad, su departamento, su país, su continente. En los inicios del siglo XX nacía en Santa Cruz de la Sierra, el 20 de enero de 1906, don Raúl Otero Reiche, hijo de los esposos Samuel Otero y Raquel Reiche. Su ciudad natal, por la que siente un profundo amor y que será una constante en toda su obra poética —´Construcción de Santa Cruz de la Sierra´, ´Doña Santa Cruz de la Sierra´, ´Exaltación de Santa Cruz de la Sierra´— irá moldeando poco a poco la personalidad del poeta mayor del Oriente boliviano. A partir del amor a la ´amable ciudad vieja´ —que seguía estando tan lejos de cualquier parte como en el momento de su fundación y que era una ciudad provinciana pequeña y pobre en la que pareciera que el tiempo se hubiera detenido— descubre al hombre y el paisaje cruceño ´Canto al hombre de la selva´; a partir de este conocimiento, que enriquece su espíritu y fomenta su creatividad, se hace universal —´América y otros poemas´—. Enrique Kempff Mercado dice que ´pocas veces se ha dado en nuestra historia una identificación tan grande entre el pueblo y el cantor de ese pueblo. Santa Cruz puede dar testimonio del hombre que durante más de medio siglo se dedicó a cantarle con una abnegación conmovedora, con un amor obcecado, Raúl Otero fue una versión del paisaje cruceño´. Creador multifacético cultivó la poesía, el ensayo, el teatro, el cuento, la novela y el periodismo. Jugó un papel activo y protagónico en la vida de la comunidad local y nacional: participó en la Guerra del Chaco (´Poemas de sangre y lejanía´, ´No se ha ido nadie´; es considerado como el poeta de esta guerra); fue docente de educación secundaria y ejerció la cátedra universitaria; incursionó en la vida política nacional; fue director de cultura del municipio cruceño; impulsó la creación de la Casa de la Cultura de su ciudad natal —que con toda justicia lleva su nombre— y fue alma y motor de numerosas instituciones culturales y de servicio. Contrajo matrimonio con la señora Nelly Arteaga, con la que formó un hogar numeroso y ejemplar. Aunque la vida de Raúl Otero Reiche terminó el 29 de enero de 1976, en su ciudad natal, la voz de su poesía trasciende el tiempo y su nombre se inscribe en la nómina de los inmortales. Raúl Otero Reiche es ´la selva indómita´; es ´el que esperaban los jaguares, los toros, los caimanes, las palomas (...) para la transfusión de sangres bárbaras´; es ´el arquetipo de esta raza salvaje´; es ´el hombre de la llanura sin fin, más larga que la vista´; es ´un río de pie´. referencias http://www.caracol.com.co/noticias/actualidad/raul-oteroreiche/20060127/nota/242439.aspx

Theodore Goodridge Roberts (July 7, 1877– February 24, 1953) was a Canadian novelist and poet. He was the author of thirty-four novels and over one hundred published stories and poems. He was the brother of poet Charles G.D. Roberts, and the father of painter Goodridge Roberts. Life He was born George Edwards Theodore Goodridge Roberts in Fredericton, to Emma Wetmore Bliss and Anglican Rev. George Goodridge Roberts. The poet Charles G.D. Roberts, and the writers William Carman Roberts and Jane Roberts MacDonald, were his siblings. He published his first poem in 1899, when he was eleven, in the New York Independent (where his cousin Bliss Carman was working), and his first prose piece (a comparison of the Battle of Waterloo and the Battle of Gettysburg) in the Century two years later. Roberts attended Fredericton Collegiate School, though (since school records were lost in a fire) the exact years are unknown. He later went to University of New Brunswick (UNB), but left without graduating. He published poetry in UNB’s University Magazine. In 1897 he moved to New York City, living with his brothers Charles and William and working at The Independent. In 1898 the magazine sent him to Cuba, as a special correspondent, to cover the Spanish–American War. While on the island he contracted malaria—he was sent back to New York and consulted specialists, who sent him back to Fredericton “to die.” An unnamed surgeon saved Roberts’s life, and he was nursed back to heath by Frances Seymour Allen (whom he would subsequently marry). The next year he travelled to Newfoundland, where he helped to found and edit The Newfoundland Magazine. He published his first book of poetry (Northand Lyrics, an anthology edited by Charles G.D. Roberts and featuring his three siblings) in 1899, and his first novel, The House of Isstens, in 1900. In 1901 Roberts sailed on a barkentine to Brazil. In 1902 he returned to Fredericton and briefly edited a second magazine, The Kit-Bag. Roberts married Frances Seymour Allen in November 1903, and they had a two-year honeymoon in Barbados where their first child was born. They would have four children: William Goodridge, Dorothy Mary Gostwick, Theodora Frances Bliss and Loveday (who died as an infant). Roberts averaged three novels a year from 1908 until 1914. At that time his “many novels of adventure and romance” already enoyed a “wide popularity in English-speaking lands.” A former militiaman, Roberts re-enlisted in 1914 when World War I broke out, serving as a lieutenant in the 12th Canadian Infantry Battalion, commanded by Lt.-Col. Harry Fulton McLeod of Fredericton—Roberts’ entire family followed him to England. When the 12th Battalion was assigned to a reserve and training roll in early 1915, Roberts was transferred to a position perhaps better fitted to his combination of military knowledge and literary skill. "In the summer of 1915, he was transferred to the Canadian War Records Office at the request of Max Aitken, Lord Beaverbrook. Roberts wrote official reports and battlefield accounts and published three works in collaboration with others." He was promoted captain early in 1916. When Roberts was in Europe he left his manuscripts and papers, including work not yet published, with a Dr. Wainwright in Saint John, who stored them in his basement. They were destroyed in the spring of 1919 when the Saint John River flooded. In 1929 Roberts wrote a weekly column for the Saint John Telegraph-Journal, “Under the Sun.” From April through September 1930 he edited another small magazine, Acadie. In 1932 he undertook his last major sea cruise, sailing through the Panama Canal to Vancouver and back. The same year he did a cross-Canada reading tour, which “culminated with festivities in Vancouver.” Roberts moved to Toronto in 1935, and in 1937 briefly edited another magazine, Spotlight. In 1939 he relocated to Aylmer, Quebec, where he briefly founded another magazine, Swizzles. He returned to New Brunswick in 1941, and in 1945 moved to Digby, Nova Scotia, where he would die eight years later. He is buried beside Charles G.D. Roberts and Bliss Carman in Fredericton’s Forest Hill Cemetery. Writing The Dictionary of Literary Biography (DLB) says that T.G. Roberts’s “poetry and fiction, staggering in sheer quantity and variety, show at their best Roberts’s most enduring gifts: in his poetry a love of nature well served by a keen eye for local color and detail, a good ear for clean, clear rhythm and rhyme, and a forceful, uncluttered narrative line; and in fiction a talent for presenting his abiding perception of universal struggles between good and evil either in mythic tales of adventure or in regional stories animated by local settings, customs, and dialects.” Of the poems in his 1926 collection, The Lost Shipmate, The Encyclopedia of Literature commented: "Had this volume appeared forty years earlier it might have won for Theodore a reputation equal to that of his brother Charles or of Bliss Carman. Poems such as ‘The sandbar’ and ‘Magic’ are unmatched in Canadian poetry for a facility and clarity of image suggestive of high-realist painting. However, much of what Roberts wrote has been forgotten with time, or has not stood the tests of time and changing fashion. The Merriest Knight The writing that Roberts is most likely to be recognized for today is The Merriest Knight, his collection of Arthurian tales. This looks like the one book by Roberts currently in print - ironically, considering that it was never published as a book during Roberts’s lifetime. Roberts began to write Arthurian fiction in the 1920s; most of these stories, though, were published in the late 1940s and early 1950s in the fiction magazine Blue Book. Roberts planned to publish them as a collection, but died in 1953 before he could do so. In 2001 Mike Ashley, editor of the Mammoth publishing group, brought them out under his Green Knight imprint. A review for SFSite called the collection’s writing “polished,” “erudite,” and “eminently readable,” but “somewhat tame”: “literature for the afternoon tea and crumpets crowd– in a word 'polite’ Arthurian fiction.” Still, it concluded, “if you’re looking for something a bit more upbeat, some Arthuriana-lite, The Merriest Knight is just the book for you.” Recognition The University of New Brunswick awarded Roberts a Doctorate of literature in 1930. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada in 1934. Publications Fiction * The House of Isstens. Boston: L.C. Page, 1900. * Hemming the Adventurer. Boston: L.C. Page, 1904. * Brothers in Peril: A Story of Old Newfoundland, 1905. Boston: L.C. Page & Company, 1905. * Red Feathers: a story of remarkable adventures when the world was young. Boston: L.C. Page, 1907. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. ISBN 978-0-7710-9227-5 * Captain Love. Boston: L.C. Page & Company, 1908. * Flying Plover: His Stories, Told Him by Squat-by-the-Fire. Boston: L.C. Page, 1909. * A Cavalier of Virginia: a romance. Chicago: M.A. Donohue, 1910. * Comrades of the Trails. Boston: L.C. Page & Company, 1910. * Love on a Smokey River. 1911. * A Captain of Raleigh’s: a romance. Boston: L.C. Page & Company, 1911. * A Soldier of Valley Forge. with Robert Neilson Stephens. Boston: L.C. Page, 1911. * Blessington’s Folly. London: John Long, 1912. * Rayton: a backwoods mystery. Boston: L.C. Page, 1912. * The Harbor Master. Chicago: M.A. Donohue, 1913. * Two Shall Be Born. New York: Cassell, 1913. * The Wasp. Toronto: Bell & Cockburn, 1914. * The Toll of the Tides. 1914. * In the High Woods. London: John. Long, 1916. * Forest Fugitives. Toronto: McClelland, Goodchild & Stewart, 1917. * The Islands of Adventure. London; Toronto: Hodder and Stoughton, 1918. * Jess of the River. London: John Long, 1918. * The Exiled Lover. London: John Long, 1919. * Honest Fool. New York: F.A. Munsey, 1925. * The Master of the Moosehorn and Other Backwoods Stories. London; Toronto: Hodder and Stoughton, 1919. * Moonshine. London: Hodder and Stoughton, [1920?]. * The Lure of Piper’s Glen. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Page, 1921. * The Fighting Starkleys. George Varian illus. Boston: Page, 1922. * Musket House. 1922. * Tom Akerley: his adventures in the tall timber and at Gaspard’s clearing on the Indian River. Boston: L.C. Page, 1923. * Green Timber Thoroughbreds. New York: Garden City, 1924. * The Stranger from Up-Along. Garden City, NJ: Doubleday, Page & co., 1924. * The Red Pirogue: a tale of adventure in the Canadian wilds. Boston: L.C. Page, 1924. * The Oxford Wizard. Garden City, NY: Garden City Pub., 1924. * The Lost Shipmate. Toronto: Ryerson, 1926. * The Golden Highlanders. Boston: L.C. Page, 1929. * The Merriest Knight: The Collected Arthurian Tales of Theodore Goodridge Roberts. Mike Ashley ed. Green Knight, 2001. ISBN 978-1-928999-18-8 Non-fiction * Patrols and Trench Raids. 1916. * Battalion Histories. 1918. * Thirty Canadian V.Cs 23rd April 1915 to 30th March 1918, with Robin Richards and Stuart Martin. London: Skeffington, 1918. * Loyalists: a compilation of histories, biographies and genealogies of United empire loyalists and their descendants. Toronto: T. Goodridge Roberts, 1937. Poetry * Northland Lyrics, William Carman Roberts, Theodore Roberts & Elizabeth Roberts Macdonald; selected and arranged with a prologue by Charles G.D. Roberts and an epilogue by Bliss Carman. Boston: Small, Maynard & Co., 1899. ISBN 0-665-12501-1 * Seven Poems. private, 1925. chapbook. * The Lost Shipmate. Toronto: Ryerson Chapbook, 1926. * The Leather Bottle. Toronto: Ryerson, 1934. * That Far River: Selected Poems of Theodore Goodridge Roberts. Martin Ware, ed. London, ON: Canadian Poetry Press, 1998. * Except where noted, bibliographical information courtesy St. Thomas University. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theodore_Goodridge_Roberts

I think my poetry sums me up pretty well. It's full of emotion that I was feeling in that particular moment in time. I will never claim to be a writer or a poet, but I do enjoy writing poetry nonetheless. Writing, amongst other things, has been a form of escape for me. I used to keep anything I wrote to myself and never shared it except with a few persons of my choosing. I'm still a bit uncertain to share it now but I figured, why not share it? I feel as though writing is a form of release, it is for me personally anyway. So I encourage you to try it out, at least once. I'm not going to sit here and type out every detail of my life or even share much of my story with you at all. I think what I share with you in my poetry will suffice. No, my life hasn't been an easy or smooth ride, but who's life has been? I started writing from a very young age, basically since I knew how to put letters together to form words. I'm not the best, I will misspell words, use incorrect punctuation, but I'm not writing to impress and I'm not looking for people to flaunt over what I write or say cruel things about it either. But, if you enjoy them I greatly appreciate it, and if you have constructive criticism, I welcome it. Ultimately though, I chose to share my poetry for the slight chance it could impact someone or help them to know they're not the only one with pain trapped inside of them. It's for those people who think "that's exactly how I feel right now." Because I know how much it effects me when I read a quote or poem or hear a song that explains exactly the way I'm feeling. Somehow it helps knowing I'm not alone in my lonely despair. My words are in no way anything to brag about and can even be a bit dark at times. I understand that my style will not be for everyone and that's okay, you by no means have to read it. But if you do find some enjoyment in them, I very much appreciate it.

Ángel María de Saavedra y Ramírez de Baquedano, III duque de Rivas, grande de España, más conocido por su título nobiliario de duque de Rivas, (Córdoba, 10 de marzo de 1791 – Madrid, 22 de junio de 1865) fue un escritor, dramaturgo, poeta, pintor y político español, conocido por su famoso drama romántico Don Álvaro o la fuerza del sino (1835). Fue presidente del gobierno español (Consejo de Ministros entonces) en 1854, durante sólo dos días. Contando sólo un año de edad, su padre, don Juan Martín de Saavedra fue condecorado con el título de Grande de España. Abocado a la carrera militar por su condición de segundón (su hermano mayor, Juan Remigio heredaría el ducado a la muerte del padre de ambos), ingresó en 1802 en el Real Seminario de Nobles de Madrid permaneciendo en él hasta 1806. Con tan solo nueve años ya le correspondían por linaje la Cruz de Caballero de Malta, la banderola de la Guardia de Corps supernumerario, el hábito de Santiago, etc. En 1807 fue alférez de la Guardia Real. Luchó con valentía contra las tropas napoleónicas siendo herido en la Batalla de Ontígola (1809). El General Castaños le nombró capitán de la Caballería Ligera. Obtuvo también el nombramiento de primer ayudante de Estado Mayor. En 1823, Rivas fue condenado a muerte por sus creencias liberales y haber participado en el golpe de estado de Riego en 1820. Además se le confiscaron sus bienes y huyó a Inglaterra. Luego pasó a Malta en 1825 donde permaneció cinco años. En 1830 se marchó a París. Después de la muerte de Fernando VII en 1833, regresó a España al recibir la amnistía y reclamó su herencia, y además en 1834 murió su hermano mayor, Juan Remigio, y recayó en él por ello el título de Duque de Rivas. Dos años después fue nombrado ministro de la Gobernación. Luego emigró a Portugal por poco espacio de tiempo. A la vuelta desempeñó el papel de senador, alcalde de Madrid, embajador y ministro plenipotenciario en Nápoles y Francia, ministro del Estado, presidente del Consejo de Estado y presidente de la Real Academia Española y del Ateneo de Madrid en 1865. En la literatura, Rivas fue protagonista del romanticismo español. Don Álvaro, fue estrenado en Madrid en 1835, y fue el primer éxito romántico del teatro español. La obra se tomó más tarde como base del libreto de Francesco Maria Piave para la ópera de Verdi La fuerza del destino (1862). Otra obra teatral romántica fue El desengaño en un sueño. También obras de teatro fueron Malek Adel, Lanuza y Arias Gonzalo y la comedia Tanto vales cuanto tienes, estas obras son más de estilo neoclásico. Como poeta, su obra más conocida es Romances históricos (1841), adaptaciones de leyendas populares en forma del romance, pero además escribió en poesía obras como Poesías (1814), El desterrado, El sueño del proscrito, A las estrellas y Canto al Faro de Malta. En prosa escribió Sublevación de Nápoles, capitaneada por Masaniello e Historia del Reino de las Dos Sicilias. En ensayo destacó en Los españoles pintados por sí mismos. Escribió romances al estilo de leyendas con brillantes descripciones y hábil fantasía histórica como La azucena milagrosa (1847), Maldonado (1852) y El aniversario (1854). Además realizó varios cuadros de costumbres. Obras Poesías * Poesías (1814) * Al faro de Malta (1824) * La niña descoloría * Con once heridas mortales * Letrilla *El moro expósito (1834) Sonetos * A Lucianela * A Dido abandonada * Cual suele en la floresta deliciosa * El álamo derribado * Mísero leño * Ojos divinos * Receta segura * Un buen consejo Teatro *Aliatar (1816) * Lanuza (1822) * Florinda (1826) * Arias Gonzalo (1827) * El desterrado * Viaje al Vesubio * Los Hércules * El parador de Bailén * El hospedador de provincia * El duque de Aquitania * El faro de Malta (1828) * Don Álvaro o la fuerza del sino (1835) * Tanto vales cuanto tienes (1840) * La morisca de Alajuar (1841) * El desengaño en un sueño (1842) * La azucena milagrosa (1847) * El crisol de la lealtad Referencias http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Duque_de_Rivas

I'm young in age but my soul is wise and carries many messages that I hope you take the time to listen to. Music and other poets are my main source of inspiration but I'm still very capable of gaining inspiration from the small things like the way the grass wavers in the wind or how rain drops cling to my eyelashes when I'm dancing in the rain. I was born to create and words flow through my veins and impatiently rest beneath my tongue aching to be heard. My poems are cathartic and self healing but they often connect with others and help others as well. I enjoy writing for others and being their voice to portray how they feel when they lack the words needed. I live to write and I write to live. I want to improve and have constructive criticism, but compliments also help out and make me feel appreciated :)

María Enriqueta Camarillo y Roa de Pereyra (Coatepec, Veracruz, 19 de enero de 1872 - Ciudad de México, 1968) fue una poeta, cuentista, traductora, pianista, novelista y dramaturga mexicana del siglo xix. Nominada al premio Nobel en 1951. Además de la poesía, cultivó la narrativa. Fue recopiladora y editora de los libros de lectura "Rosas de la infancia" y "Nuevas rosas de la infancia".

Nacido en el municipio de La Estrella – Antioquia 1990, fue miembro de la corporación cultural Sísifo y el colectivo cultural Morphoeidos, ganador del primer puesto del concurso nacional de poesía inédita Epifanio Mejía Quijano en el 2016. Ha participado en varios recitales a nivel nacional: ciclo de nuevas voces de la poesía en Medellín del festival internacional de poesía de Medellín (2016) IV Internacional Nadaísta (2017) V Internacional Nadaista (2019) entre otros. Algunos de sus poemas han sido publicados en diversas antologías y revistas a nivel nacional: El vacío como llenura (2010) Revista el terraplén (2011) A poca tinta (2012) Antología concurso nacional de poesía inédita Epifanio Mejía Quijano (2016) Afloramientos (2018) fronteras2 (2018) Ha publicado: Poesía sobre el retrete – Fallidos Editores (2017). La liturgia de los asnos y otros poemas – Fallidos Editores (2019) Reside actualmente en Medellín - Colombia.

Mauricio Rosencof (30 de junio de 1933, Florida, Uruguay), escritor, dramaturgo y periodista uruguayo. Fue dirigente del Movimiento de Liberación Nacional (Tupamaros). Fundador de la Unión de Juventudes Comunistas y dirigente del Movimiento de Liberación Nacional – Tupamaros (MLN-T), en 1972 fue detenido y torturado brutalmente. Tras el golpe de Estado de 1973, fue declarado «rehén» junto a ocho reclusos más. Permanecer en ese estado suponía la muerte inmediata si algún acto exterior amenazaba la seguridad de las Fuerzas Armadas. Tras doce años de cárcel y horror, que no lograron acabar ni con el hombre ni con el dramaturgo, fue liberado en 1985.

Raúl Ramón Rivero Castañeda (n. Cuba; 1945) es un poeta, periodista y disidente cubano. Nació en 1945 en la localidad de Morón, perteneciente a la antigua provincia de Camagüey (actualmente corresponde a Ciego de Ávila), en el centro de Cuba. Ha publicado varios libros de poesía y ha trabajado en medios de comunicación cubanos. Vida Laboral Raúl Rivero perteneció a las primeras generaciones de periodistas que se graduaron en la Facultad de Periodismo de la Universidad de La Habana tras el triunfo de la Revolución Cubana. En 1966, fue uno de los fundadores de la revista cultural El Caimán Barbudo. Posteriormente, fue corresponsal de la agencia Prensa Latina en Moscú entre 1973 y 1976, volviendo después a Cuba, donde se encargó de la dirección del servicio de ciencia y cultura de la agencia. En 1989 abandonó el organismo oficial Unión Nacional de Escritores y Artistas de Cuba, que encuadra a todos los escritores y artistas de la isla. Dos años después, el 2 de junio de 1991, fue uno de los firmantes de la Carta de los Intelectuales, en la que se solicitaba al presidente Fidel Castro, la liberación de los presos de conciencia. Ese año, abandonó el periodismo oficial denunciándolo como una "ficción sobre un país que no existe". En 1995 fundó una agencia de noticias independiente del gobierno cubano, denominada Cuba Press. En 2001 fue uno de los fundadores de la primera asociación de periodistas de Cuba independiente del gobierno. Prisión En abril de 2003, Rivero fue condenado a 20 años de prisión durante la llamada Primavera Negra, acusado de realizar actividades subversivas encaminadas a afectar la independencia e integridad territorial de Cuba, escribir contra el gobierno, haberse entrevistado con James Cason, un diplomático estadounidense, y haber organizado reuniones subversivas en su domicilio. Juntos (Ricardo Severino González Alfonso y Raúl Ramón Rivero Castañeda) crearon la Cuba Press la cual agrupaba a varios de estos elementos contrarrevolucionarios y cuyo director es el acusado Rivero Castañeda y por medio de la cual se difundían falsas noticias sobre la situación actual en nuestro gobierno, en cumplimiento con las indicaciones recibidas por el gobierno norteamericano, de igual forma, ambos acusados crearon el treinta de mayo del dos mil, la Sociedad de Periodistas Independientes Manuel Márquez Stering de la que surgió la revista De Cuba, resultando director González Alfonso por medio de la cual suministraban información al gobierno de los Estados Unidos mediante su entrega en la oficina de Intereses de los Estados Unidos en Cuba Rivero pasó en la cárcel año y medio, con grave quebranto de su salud. En noviembre de 2004, debido a las presiones internacionales, fundamentalmente españolas, fue excarcelado, oficialmente tras serle aplicada la llamada licencia extra-penal por motivos de salud. Poco después, Rivero se trasladó a España con toda su familia. Referencias https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raúl_Rivero

Lizette Woodworth Reese (January 9, 1856– December 17, 1935) was an American poet. Reese was born in the Waverly section of Baltimore, Maryland to Louisa Gabler and David Reese. She also had a twin sister named Sophia. Educated in Baltimore’s public schools, Reese graduated from Eastern High School (Baltimore), where a memorial for her stands today. After graduation, she became a school teacher at St. John’s Parish School in 1873. The following year, Reese published her first poem, “The Deserted House,” in Southern Magazine. She continued to publish in various magazines until her first self-published anthology, A Branch of May, in 1887. Subsequent books followed in 1891 and 1896, A Handful of Lavender and A Quiet Road, respectively. During the late 1890s and early 1900s, Reese wrote infrequently. However, her sonnet, “Tears,” published in Scribner’s Magazine in 1899, garnered her praise and recognition, particularly from fellow Baltimore writer, H. L. Mencken, who stated that Reese’s work was “one of the imperishable glories of American literature." In 1918, Reese retired from teaching after having worked her last few years at Western High School (Baltimore). In 1931, Reese was named poet laureate of Maryland by the General Federation of Women’s Clubs. She was also honorary president of thee Poetry Society of Maryland and co-founder of the Women’s Literary Club of Baltimore. Reese died on December 17, 1935. She is buried at the St. John’s Episcopal Church. After her death, Reese’s friend and sculptor, Grace Turnbull was commissioned to create a monument to her work. The marble statue, entitled “The Good Shepherd” stands on the old grounds of Eastern High School, Reese’s alma mater, in Waverly.

Pablo de Rokha (n. 17 de octubre de 1894 en Licantén, Chile – m. 10 de septiembre de 1968 en Santiago, Chile), poeta chileno, cuyo nombre real era Carlos Díaz Loyola. Obtuvo el Premio Nacional de Literatura de su país en 1965 y es considerado uno de los 4 grandes de la poesía chilena (junto con Pablo Neruda, Vicente Huidobro y Gabriela Mistral). además es considerado un poeta vanguardista y de gran influencia en la lírica universal Pablo de Rokha nació en la ciudad chilena de Licantén, el 17 de octubre de 1894, con el nombre de Carlos Díaz Loyola, hijo de José Ignacio Díaz Alvarado y de Laura Loyola de Toledo, y fue el mayor de 19 hermanos. Provenía de una familia de raíz aristocrática, dueña de tierras en la zona de Talca y Licantén, pero que se encontraba en una situación económica desmejorada, por lo que su padre debió realizar diversos trabajos, como administrador de estancias y jefe de resguardo aduanero en la cordillera. En estas condiciones, Pablo de Rokha vivió su infancia en la hacienda Pocoa de Corinto, administrada por su padre, y acompañaba a éste en sus andanzas cordilleranas. En 1901 ingresó a la Escuela Pública nº3 de Talca. Posteriormente, en 1902, ingresó al Seminario Conciliar San Pelayo de Talca, de donde fue expulsado en 1911 por leer a autores "prohibidos". Sus inicios poéticos se expresaron en este período, bajo el pseudónimo de Job Díaz, para luego obtener el pseudónimo de El amigo Piedra. Se trasladó a la capital Santiago de Chile en 1911, para cursar el sexto año de humanidades. Dio su bachillerato en 1912, y se matriculó en la Universidad de Chile con el fin de estudiar derecho o ingeniería. Finalmente esto no ocurrió. Fueron éstos tiempos oscuros para el poeta, que vivió en una nebulosa de disgregación y desencanto familiar. Despuntó en él un carácter violento y rebelde. Durante el transcurso, escribió para distintos periódicos, como La Razón y La Mañana. Publicó sus primeros poemas en Santiago en la revista Juventud de la Federación de Estudiantes de la Universidad de Chile (FECH). Volvió a Talca en 1914 con un sentimiento de fracaso. Fue cuando recibió un libro de poemas firmado por Juana Inés de la Cruz, titulado Lo que me dijo el silencio. Pese a criticar con gran dureza el poemario, no pudo evitar enamorarse de la poetisa, por lo que volvió a Santiago en busca de su amor. El 25 de octubre de 1916 finalmente se casó con Luisa Anabalón Sanderson, verdadero nombre de la poetisa. Luisa, posteriormente, tomaría el seudónimo literario de Winétt de Rokha. Entre 1922 y 1924 residió en San Felipe y Concepción, lugar último donde fundó la revista Dínamo. Colaboró con el Frente Popular que eligió presidente de Chile a Pedro Aguirre Cerda en 1938. Mientras tanto, su vida familiar crecía al nacer sus hijos Carlos (poeta conocido como Carlos de Rokha), Lukó (pintora conocida como Lukó de Rokha), Tomás, Juana Inés, José (pintor conocido como José de Rokha), Pablo, Laura y Flor. Varios de ellos murieron prematuramente: Carmen y Tomás, muy pequeños, mientras que Carlos y Pablo murieron ya mayores y de manera trágica. En 1944 el Presidente Juan Antonio Ríos lo nombró Embajador cultural de Chile en América y el poeta inició un extenso viaje por 19 países del continente. Luego de constantes viajes, se enteró en una escala en Argentina que Gabriel González Videla había sido elegido Presidente de la República, quien dictó la Ley de Defensa de la Democracia y comenzó un período de represión contra el Partido Comunista. En 1949, el poeta volvió a Chile. Su esposa Winétt de Rokha llegó al país enferma de cáncer, para luego fallecer en 1951. En 1953 apareció Fuego negro, elegía de amor dedicada a Winétt. En 1955 publicó Neruda y yo, ácida crítica al poeta, al que llama plagiador, mistificador de los trabajadores y al cual clasificó de falso artista y militante. Estas afirmaciones le provocaron fuerte rechazo de parte de amigos de Neruda. Rokha, con su comunismo ateo y prepotente, no era aceptado entre los más conciliadores seguidores de Neruda. En 1960, con Genio del pueblo, se volvió a suscitar la polémica con Pablo Neruda, satirizado bajo el pseudónimo de Casiano Basualto. Pablo de Rokha continuó su vida embargado en el dolor y el recuerdo imborrable de su compañera Winétt. El dolor se agrandó con la muerte de su hijo Carlos en 1968, lúcido poeta de la época, aunque poco reconocido en la actualidad. Los escritores, y en especial poetas, lo admiraban en gran manera. En 1965 recibió el Premio Nacional de Literatura de Chile, del cual declaró: «Me llegó tarde, casi por cumplido y porque creían que no iba a molestar más». El 19 de octubre de 1966, fue nombrado Hijo Ilustre de Licantén. En 1967, publicó el que fue su último libro editado en vida, Mundo a mundo: Francia. El 10 de septiembre de 1968, a los 73 años de edad, Pablo de Rokha se suicidó de un balazo en la boca, siguiendo el destino de su hijo Pablo, muerto meses antes, y el de su amigo Joaquín Edwards Bello, muerto ese mismo año. Toda la amargura del poeta se puede expresar en la siguiente declaración con motivo de su Premio Nacional de Literatura: «Mis impresiones en este momento son contradictorias. Cuando vivía Winett, mi mujer, y también mi hijo Carlos, antes de que la familia se destrozara, este galardón me habría embargado de un regocijo tan inmenso, infinitamente superior a la emoción que siento en este momento. Hoy para un hombre viejo, este reconocimiento nacional que indudablemente me emociona, no puede tener la misma trascendencia. Poesía * Versos de la infancia, 1916. * El folletín del diablo, 1916-1922. * Sátira, 1918. * Los gemidos, 1922. * Cosmogonía, 1922-1927. * U, 1927. * Satanás, 1927. * Suramérica, 1927. * Ecuación, 1929. * Escritura de Raimundo Contreras, 1929. * El canto de hoy, 1930-1932. * Canto de trinchera, 1933. * Jesucristo, 1930-1933. * Los 13, 1934-1935. * Oda a la memoria de Máximo Gorki, 1936. * Moisés, 1937. * Gran temperatura, 1937. * Imprecación a la bestia fascista, 1937. * Cinco cantos rojos, 1938. * Morfología del espanto, 1942. * Canto al Ejército Rojo, 1944. * Los poemas continentales, 1944-1945. * Carta Magna del continente, 1949. * Fusiles de sangre, 1950. * Funeral por los héroes y los mártires de Corea, 1950. * Fuego negro, 1951-1953. * Arte grande o ejercicio del realismo, 1953. * Antología, 1916-1953. * Idioma del mundo, 1958. * Genio del pueblo, 1960. * Acero de invierno, 1961. * Canto de fuego a China Popular, 1963. * China Roja, 1964. * Estilo de masas, 1965. * Epopeya de las comidas y bebidas de Chile / Canto del macho anciano, 1965. * Infinito contra infinito, ????. * El amigo Piedra, 1989. * Epitafio en la tumba de Juan, el carpintero, ????. Ensayos * Heroísmo sin alegría, 1926. * Interpretación dialéctica de América: los cinco estilos del Pacífico – Chile, Perú, Bolivia, * * Ecuador y Colombia, 1948. * Arenga sobre el arte, 1949. * Neruda y yo, 1956. * Mundo a mundo: Francia (originalmente Mundo a mundo, París, Moscú, Pekín), 1967. Referencias Wikipedia - http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pablo_de_Rokha

Amelia Rosselli (Parigi, 28 marzo 1930 – Roma, 11 febbraio 1996) è stata una poetessa, organista ed etnomusicologa italiana che ha fatto parte della “generazione degli anni trenta”, insieme ad alcuni dei più conosciuti nomi della letteratura italiana. Biografia Amelia Rosselli nacque a Parigi, figlia dell’esule antifascista Carlo Rosselli, teorico del Socialismo Liberale, e di Marion Cave, nata in Inghilterra e attivista del partito laburista britannico. Nel 1940, dopo l’assassinio del padre e dello zio, ordinato da Mussolini e Ciano, ad opera delle milizie fasciste (cagoulards) in Francia (1937), esulò con la famiglia, esperienza che determinò il carattere apolide e insieme personalissimo della sua opera. Amelia Rosselli si trasferì dapprima in Svizzera e quindi negli Stati Uniti. Compì all’estero (senza regolarità) studi letterari, filosofici e musicali, ultimandoli in Inghilterra, poiché in Italia, dove era tornata nel 1946, non le poterono essere riconosciuti. Negli anni quaranta e cinquanta si occupò di teoria musicale, etnomusicologia e composizione, trasponendo le sue ricerche in alcuni saggi. Nel 1948 cominciò a lavorare come traduttrice dall’inglese per alcune case editrici di Firenze e Roma e per la Rai; nel frattempo continuò a dedicarsi a studi letterari e filosofici. In questi anni cominciò a frequentare gli ambienti letterari romani (tramite gli amici Carlo Levi e Rocco Scotellaro, conosciuto nel 1950) e gli artisti che avrebbero successivamente dato vita all’avanguardia del Gruppo 63. Negli anni sessanta si iscrisse al PCI e cominciò a pubblicare i suoi testi principalmente su riviste, attirando l’attenzione di Zanzotto, Raboni e Pasolini. Nel 1963 pubblicò su Il Menabò ventiquattro poesie. L’anno successivo uscì la sua prima raccolta di poesie, Variazioni belliche, edita da Garzanti, e nel 1969 la raccolta Serie ospedaliera, comprensiva del poemetto di difficile gestazione e inedito La Libellula. Nel 1966 iniziò a pubblicare numerose recensioni letterarie su giornali come Paese Sera e L’Unità. Nel 1981 uscì Impromptu, un lungo poema diviso in tredici sezioni, e nel 1983 Appunti sparsi e persi, scritti tra il 1966 e il 1977. Notevole anche la sua ricerca plurilinguistica in poesia (poesie e prose giovanili in francese e in inglese, la successiva raccolta in inglese Sleep). Alcune prose italiane, autobiografiche, di vari periodi, furono raccolte e pubblicate nel 1990, con il titolo Diario ottuso. La morte della madre (avvenuta nel 1949) e altre drammatiche vicende biografiche le causarono ricorrenti esaurimenti nervosi. Non accettò mai la diagnosi di schizofrenia paranoide che le venne fornita da cliniche svizzere e inglesi, ma parlò per lo più di lesioni al sistema extrapiramidale, connesse alla malattia di Parkinson, che le si manifestarono già a 39 anni. È rimasta una figura di scrittrice unica per il suo plurilinguismo e per il tentativo di fondere l’uso della lingua con l’universalismo della musica. Ha vissuto gli ultimi anni della sua vita a Roma, nella sua casa a via del Corallo, dove è morta suicida l’11 febbraio 1996 per cause connesse ad una grave depressione. La data del suicidio segna forse volontariamente un nesso indelebile con quella di Sylvia Plath, autrice che la Rosselli tradusse e amò, dedicandole anche diverse pagine critiche. Su Amelia Rosselli e la sua poesia Elogio del fuoco davanti alla bara di Amelia Rosselli, Roma, Casa della cultura, 16 febbraio 1996Il fuoco riscalda. A leggere la poesia di Amelia, la temperatura del nostro corpo si altera un po’. Talvolta si abbassa, più spesso si innalza. E non diversi effetti scaturivano dall’ascolto, dalla sua viva voce di straordinaria lettrice. […] La sua voce era un basso profondo, una musica che faceva lievitare la fondamentale tra le parole rese singole e compenetrate le une nelle altre. […] Mai un grido nella sua recitazione, eppure quanti soprassalti nelle sue poesie! Per lei hanno nominato Campana, Rimbaud. Ma nulla le era più estraneo dello sregolamento dei sensi, dello sfrenato abbandonarsi all’altra voce che urge quando la ragione tace. In lei parlano entrambe, la ragione della mente e quella che piove dall’Altrove, ma in una educata, civilissima convivenza che non dimenticheremo mai. Il fuoco illumina. La poesia di Amelia Rosselli è oscura eppure chiarissima. Certo, bisogna abituarvisi, come quando si entra da fuori in una stanza buia. All’inizio avanziamo cautamente, abbiamo paura di farci male, urtiamo negli spigoli, imprechiamo. Ma poi diventiamo come i gatti che vedono anche nelle tenebre. Come loro impariamo a sviluppare sensi normalmente inerti, latenti. La sua forma di conoscenza è la Pietà, un grande canzoniere d’amore, senza tracce di narcisismo. […] Il fuoco scotta. Con la Storia che le ha marchiato i suoi segni sul corpo, prima ancora che nella mente. Dietro la sua poesia-amore avanzano la persecuzione politica, l’assassinio, la tragedia del conflitto più violento di un secolo ormai alla fine. La sua lingua, dissennatamente poliglotta, ne è stata disarticolata, ma quanto dilatata! Con Amelia se ne va l’ultima vittima di un secolo divoratore dei suoi poeti. Un’epoca che ostenta indifferenza verso la poesia e che continua a nutrirsene avidamente, cannibalisticamente. Marina Cvetaeva diceva che con la poesia bisogna comportarsi come con le creature amate. Si sta con loro finché non sono loro a lasciarci. E chi resta da solo con il dolore e il lutto non dimenticherà la gioia della dedizione fino al sacrificio finale.(Biancamaria Frabotta, Elogio del fuoco, in Quartetto per masse e voce sola, Roma, Donzelli, 2009, pp. 65-67)