Info

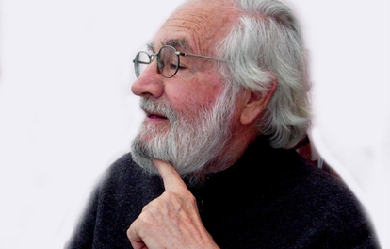

Tomás Segovia (Valencia, España, 21 de mayo de 1927 - México, 7 de noviembre de 2011) fue un escritor, poeta y ensayista nacido en España y nacionalizado mexicano. En México trabajó para cine y televisión, dio clases en el Instituto de Intérpretes y Traductores y fue nombrado profesor-investigador por El Colegio de México. En Estados Unidos fue profesor visitante en la Universidad de Princeton.

Charles Simic (born Dušan Simić; May 9, 1938) is a Serbian-American poet and was co-poetry editor of the Paris Review. He received the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1990 for The World Doesn’t End, and was a finalist of the Pulitzer Prize in 1986 for Selected Poems, 1963-1983 and in 1987 for Unending Blues. He was appointed the fifteenth Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress in 2007. Biography Early years Dušan Simić was born in Belgrade. In his early childhood, during World War II, he and his family were forced to evacuate their home several times to escape indiscriminate bombing of Belgrade. Growing up as a child in war-torn Europe shaped much of his world-view, Simic states. In an interview from the Cortland Review he said, “Being one of the millions of displaced persons made an impression on me. In addition to my own little story of bad luck, I heard plenty of others. I’m still amazed by all the vileness and stupidity I witnessed in my life.” Simic immigrated to the United States with his brother and mother in order to join his father in 1954 when he was sixteen. He grew up in Chicago. In 1961 he was drafted into the U.S. Army, and in 1966 he earned his B.A. from New York University while working at night to cover the costs of tuition. He is professor emeritus of American literature and creative writing at the University of New Hampshire, where he has taught since 1973 and lives on the shore of Bow Lake in Strafford, New Hampshire. Career He began to make a name for himself in the early to mid-1970s as a literary minimalist, writing terse, imagistic poems. Critics have referred to Simic’s poems as “tightly constructed Chinese puzzle boxes”. He himself stated: “Words make love on the page like flies in the summer heat and the poet is merely the bemused spectator.” Simic writes on such diverse topics as jazz, art, and philosophy. He is a translator, essayist and philosopher, opining on the current state of contemporary American poetry. He held the position of poetry editor of The Paris Review and was replaced by Dan Chiasson. He was elected to The American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1995, received the Academy Fellowship in 1998, and was elected a Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets in 2000. Simic was one of the judges for the 2007 Griffin Poetry Prize and continues to contribute poetry and prose to The New York Review of Books. Simic received the US$100,000 Wallace Stevens Award in 2007 from the Academy of American Poets. He was selected by James Billington, Librarian of Congress, to be the fifteenth Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress, succeeding Donald Hall. In choosing Simic as the poet laureate, Billington cited “the rather stunning and original quality of his poetry”. In 2011, he was the recipient of the Frost Medal, presented annually for “lifetime achievement in poetry.” Awards * PEN Translation Prize (1980) * Ingram Merrill Foundation Fellowship (1983) * MacArthur Fellowship (1984–1989) * Pulitzer Prize finalist (1986) * Pulitzer Prize finalist (1987) * Pulitzer Prize for Poetry (1990) * Wallace Stevens Award (2007) * Frost Medal (2011) * Vilcek Prize in Literature (2011) * The Zbigniew Herbert International Literary Award (2014) * Golden Wreath of the Struga Poetry Evenings (2017) Bibliography References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Simic

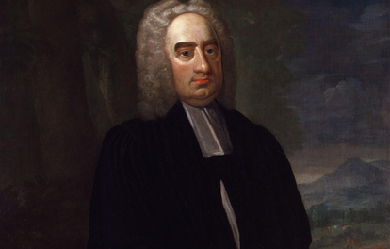

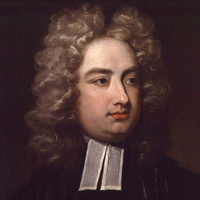

Jonathan Swift (30 November 1667– 19 October 1745) was an Anglo-Irish satirist, essayist, political pamphleteer (first for the Whigs, then for the Tories), poet and cleric who became Dean of St Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin. Swift is remembered for works such as Gulliver’s Travels, A Modest Proposal, A Journal to Stella, Drapier’s Letters, The Battle of the Books, An Argument Against Abolishing Christianity and A Tale of a Tub. He is regarded by the Encyclopædia Britannica as the foremost prose satirist in the English language, and is less well known for his poetry.

Louisa Siefert, née à Lyon le 1er avril 1845 et morte à Pau le 21 octobre 1877, est une poétesse française. Issue d'une famille protestante établie à Lyon, elle reçoit une bonne éducation religieuse. Son père Henri était un homme d’affaires venu jeune à Lyon et originaire de la Hesse tandis que sa mère était fille et petite-fille de soyeux lyonnais, de lointaine origine alémanique (canton de Thurgovie en Suisse) et alliés en France à une famille descendante de protestants cévenols. Elle meurt le 21 octobre 1877 à Pau où elle soignait une tuberculose osseuse (coxalgie) qui avait fini par atteindre ses poumons. Elle est inhumée dans le carré B153 du cimetière communal de Saint-Cyr-au-Mont-d'Or, village où elle habitait, au hameau des Ormes. Louisa Siefert est l'arrière-grand-tante du chanteur Renaud.

JOSÉ SANTIAGO -Poeta ante todo- : Nace en Almuñécar (Granada) 1963 * España * (Gestor Cultural, Escritor, fotógrafo artístico, diseñador gráfico, poeta, pintor, Embajador de Paz - España (WIP), Embajador de la Palabra (FCES), Embajador Cultural Internacional (CIESART), Embajador Int. Del F. Mundial de Literatura por la Paz y los Derechos Humanos (WLFPH). Promotor Cultural: fundador, coordinador de eventos culturales, Gacetas Literarias, Encuentros de las Artes. Autor de 8 libros publicados: * "TÚ O LA ESPUMA: poema al atardecer", con prólogo de Manuel Alvar, exdirector de la Real Academia Española. I.S.B.N. 84 85764 75 7. * HURGANDO SILENCIOS, I.S.B.N. 84- 607- 2085- 6. * AMONTONANDO ESTELAS, I.S.B.N. 84- 607-2086-4 * AMONTONANDO ESTELAS - Segunda Edición - Libro solidario con Unicef - Depósito Legal GR-939-2014 * ALMA GITANA (que años atrás leyera Luis Rosales, “vacilando de paisano granaíno” a sus compañeros de la Real Academia) con I.S.B.N. 84- y con el Registro de Propiedad Intelectual 1317. * ENTREAZULES, edición solidaria con F.E.D.E.R (Federación Española de Enfermedades Raras - coautor- Dep. Legal: GR 556-2014 * KITTY POEMA A ANA FRANK, Edición por el Fomento de la Lectura Gratuita – Dep. Legal: GR 1725-2015 * HUIDA O POSE DE SIRENA, Edición por el Fomento de la Lectura Gratuita – Dep. Legal: GR-131-2016. *VERSOS DE LUNA, Edic. Fom. Lect. Grat. Dep. Legal: GR 691-2017 En preparación su nuevo libro “Se Adentra” título no definitivo. Los libros de José Santiago, son de acceso gratuitos al considerar que la cultura debe de estar al alcance de todos y, por lo general, destinados a fines solidarios. JOSÉ SANTIAGO (escritor, fotógrafo artístico, poeta, pintor...) Fundé la Agrupación de Jóvenes Poetas. El 12 de julio de 1986 se estrena mi obra Alma Gitana. Dirijo durante cuatro años la Gaceta Literaria, fundando, coordinando y dirigiendo posteriormente la Gaceta Literaria de Mnemosine, fundo, colaboro y dirijo Libertad de Expresión. Se me nombró presidente de la delegación en Granada y presidente de Cooperación Cultural y Publicaciones del Sindicato Nacional de Escritores, desde donde fui galardonado en la Décima edición de premios Iberoamericanos de Poesía. He colaborado en diversas publicaciones, a Encuentros de Poesía, en la Semana Cultural de la AED de la Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, en el Voluntariado Cultural de la Junta de Andalucía, etcétera. Así como fundé, dirigí y participé también con fotografías artísticas y mis pinturas en los Encuentros de las Artes. He colaborado en Radio y fui redactor de la Televisión Local de Almuñécar. Durante mi residencia en Madrid, compartí con Rafael Alberti, entablando entrañable amistad con Luis Rosales, Gabriel Celaya, Manolo Rivera, Javier Sanmartín, entre otros (Juan de Loxa, José Martín Recuerda, Ángel Cobo...) Publicaciones: numerosas en las Gaceta Literaria y la de Mnemosine, crítica literaria, artículos periodísticos en varios medios, en Granada Costa, Newipens Romaní, en Libertad de Expresión y otros. Libros Publicados: "TÚ O LA ESPUMA: poema al atardecer", con prólogo de Manuel Alvar, exdirector de la Real Academia Española. I.S.B.N. 84 85764 75 7. HURGANDO SILENCIOS, I.S.B.N. 84- 607- 2085- 6. AMONTONANDO ESTELAS, I.S.B.N. 84- 607-2086-4 y ALMA GITANA (que años atrás leyera Luis Rosales, “vacilando de paisano granaìno” a sus compañeros de la Real Academia) con I.S.B.N. 84- y con el Registro de Propiedad Intelectual 1317. En la actualidad estoy trabajando en una novela y concluyendo otras obras poéticas. * NOTA: BUSCO EDITORIAL SERIA PARA FUTURAS EDICIONES DE MIS LIBROS PUBLICADOS EN OTROS PAISES

Albert Samain, est né le 3 avril 1858 à Lille et mort le 18 août 1900 à Magny-les-Hameaux, il est un poète symboliste français. Biographie il est le Fils du commerçants lillois—son père et sa mère tiennent un commerce de vins et spiritueux—Albert Samain est naît en face de l’église Saint-Maurice, au 75 de la rue de Paris. Son père décède lors qu’il n’avait que 14 ans il a dut interrompre ses études pour gagner sa vie. Il est d’abord coursier chez un agent de change, puis employé dans une maison de courtage en sucre. Vers 1880, il est envoyé à Paris, où il décide de rester. Après plusieurs emplois, il devient expéditionnaire à la préfecture de la Seine en 1883 et bientôt il va etre rejoint par sa famille. Depuis longtemps attiré par la poésie, il fréquente les cercles à la mode, tels que les Hirsutes et les Hydropathes, et commence à réciter ses poèmes aux soirées du Chat noir. Il participe à un cercle littéraire qui réunit quelques amis, dont Antony Mars, Alfred Valette et Victor Forbin, dans une arrière boutique de la rue Monsieur-le-Prince. En 1889, il participe à la création du Mercure de France, avec Alfred Vallette, Ernest Raynaud, Jules Renard, Édouard Dubus et Louis Dumur. Au début des années 1890, fortement influencé par Baudelaire, il évolue vers une poésie plus élégiaque. En 1893, la publication du recueil Au jardin de l’infante lui vaut un succès immédiat après que François Coppée lui a consacré un article très élogieux dans Le Journal. La perfection de la forme, alliée à une veine mélancolique et recueillie, caractérise un art d’une extrême sensibilité. Il collabore notamment au Mercure de France et à la Revue des deux Mondes. Sa mère meurt en janvier 1899. À partir de novembre 1899 la santé de Samain se détériore. Au printemps l’Administration lui accorde un congé pour ce qui se révèlera une phtisie. Il va alors à Lille chez sa sœur, puis il est accueilli par son ami Raymond Bonheur à Magny-les-Hameaux, dans la vallée de Chevreuse. C’est là qu’il meurt quelques mois plus tard, à quarante-deux ans. Mais il a eu le temps d’y écrire Polyphème, un drame lyrique pour lequel Raymond Bonheur compose des chœurs, souvent considéré comme son chef-d’œuvre, qui ne sera mis en scène que quatre ans après sa mort. Rapatrié à Lille, il est enterré le 21 août 1900 au cimetière du l’Est, emplacement O4/FO5-3. Du point de vue des formes poétiques, une des originalités de Samain est l’utilisation du sonnet à quinze vers. Après sa mort, ses poésies sont réimprimées un nombre considérable de fois. De nombreux musiciens composent des mélodies sur ses textes, parmi lesquelles plusieurs chefs-d’œuvre, comme Arpège de Gabriel Fauré, l’opéra Polyphème de Jean Cras ou La Maison du matin d’Adrien Rougier. Son œuvre a également inspiré le sculpteur Émile Joseph Nestor Carlier (1849-1927) qui réalise à partir de celle-ci La Danseuse au voile et Pannyre aux talons d’or, en 1914. Œuvres Poésie * Au Jardin de l’Infante (1893) disponible sur Gallica * Au Jardin de l’Infante. Augmentée de plusiers poèmes (1897; 13e éd. 1906) * Aux flancs du vase (1898), illustré de gravures en couleurs par Gaston La Touche * Le Chariot d’or. Symphonie héroïque (1900) * Aux flancs du vase, suivi de Polyphème et de Poèmes inachevés (1902) disponible sur Gallica * Contes. Xanthis. Divine Bontemps. Hyalis. Rovère et Angisèle (1902) Texte en ligne * Polyphème, comédie en 2 actes, (1904). Paris, Théâtre de l’Œuvre, 10 mai 1904. * Hyalis, le petit faune aux yeux bleus (1909) * Œuvres d’Albert Samain. I. Au jardin de l’infante. Augmenté de plusieurs poèmes (1924) Texte en ligne * Œuvres d’Albert Samain. II. Le Chariot d’or ; Symphonie héroïque ; Aux flancs du vase (1924) Texte en ligne * Œuvres d’Albert Samain. III. Contes ; Polyphème ; Poèmes inachevés (1924) Texte en ligne * Œuvres choisies. Préface de Francis Jammes. Portrait d’Albert Samain sur son lit de mort, par Eugène Carrière, deux autres portraits en phototypie. En appendice: Lettre de Stéphane Mallarmé reproduite en fac-similé. Poésies de Louis Le Cardonnel, Charles Guérin. Textes de Remy de Gourmont, Louis Denise, Adolphe Van Bever et Paul Léautaud. Bibliographie complète. Édition du manuscrit (1928) * Poèmes pour la grande amie, introduction et notes par Jules Mouquet (1942) * Œuvres poétiques complètes, édition de Christophe Carrère, Classiques Garnier, coll. « Bibliothèque du XIXe siècle », no 40, 2015. Correspondance et carnets * Lettres inédites du poète Albert Samain, 1896-1900 (s.d.) * Des lettres, 1887-1900. À François Coppée, Anatole France, Henri de Régnier, Charles Guérin, Paul Morisse, Georges Rodenbach, Odilon Redon, André Gide, Raymond Bonheur, Jules Renard, Paul Fort, Marcel Schwob, Pierre Louÿs, etc. (1933) * Carnets intimes. Carnets I à VII. Notes. Sensations. Portraits littéraires. Notes diverses. Évolution de la poésie au XIXe siècle (1939) * Lettres à Tante Jules. Introduction et notes par Jules Mouquet (1943) * Une amitié lyrique: Albert Samain et Francis Jammes. Correspondance inédite. Introduction et notes par Jules Mouquet (1945) Bibliographie * Alfred Jarry, Albert Samain (Souvenirs), Paris, Éditions Victor Lemasle, 1907. * Albert Samain, sa vie, son oeuvre, par Léon Bocquet avec photographie et autographe. Préface de Francis Jammes, Paris, éditions Mercure de France Prix * Prix Archon-Despérouses 1898. Odonymie Rues * Rue Albert Samain, 59491 Villeneuve-d’ascq * Rue Albert Samain, 66000 Perpignan * Rue Albert Samain, 59240 Dunkerque * Rue Albert Samain, 75017 Paris * Rue Albert Samain, 76620 Le Havre * Rue Albert Samain, 78000 Versailles * Rue Albert Samain, 59160 Lille * Rue Albert-Samain 34070 Montpellier * Rue Albert Samain 92240 Malakoff * Rue Albert Samain, 59242 Templeuve * Rue Albert Samain, 59554 Neuville-Saint-Rémy * Rue Albert Samain, 03100 Montluçon * Rue Albert Samain, 46000 Cahors * Rue Albert Samain, 74000 Annecy * Rue Albert Samain, 13200 Arles Établissements scolaires * Collège ALBERT SAMAIN, 59058 Roubaix * École maternelle publique Albert Samain, 59100 Roubaix * École primaire Albert Samain, Dunkerque * École primaire Albert Samain, 24 rue des écoles Jean Baudin 78114 Magny-les-Hameaux * École primaire Albert Samain, Rue Balzac 59790 Ronchin * École primaire Albert Samain, 28 place de la République 59130 Lambersart * École élémentaire publique Albert Samain– 78180 Montigny-le-Bretonneux . Les références Wikipedia – https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albert_Samain

Receiving my graduate degree from JFK University in Consciousness and the Arts and undergraduate education in Language and Sociology from Howard University, my contributions to society include: improving the status of women in the American Society, consulting on family education and management. Before retiring, I worked as the Secretary for the U.S. Treasury, Proofreader for the Office of the Price Administration and was a Researcher and Public Relations Director for the Eisenhower Congressional Committee. I am now a Professional Volunteer. Some of my achievements are as follows: Senior Senator to the California Senior Legislature Past Presidency and/or Advisor: AAUW, Business and Professional Women, Richmond Plaza Neighborhood Council, Council for Civic Unity, Advisory Council on Aging, Mental Health Task Force on Aging, Elder Abuse Consortium, Ethnic and Handicapped Task Force. I am a proud parent of three children and grandparent of four grandchildren and I share my life with Joe, my husband, who retired as a General Dentist.

Nicomedes Santa Cruz Gamarra (* Lima, 4 de junio de 1925 — † Madrid, España, 5 de febrero de 1992), fue un decimista peruano que llevó la cultura de su país por distintos lugares del mundo. Biografía Nicomedes Santa Cruz nació el 4 de junio de 1925 en el Distrito de La Victoria, Lima - Perú. Hijo de Nicomedes Santa Cruz Aparicio y de Vicky Gamarra Domínguez, era el noveno de diez hermanos. Al concluir el colegio, se decidió a trabajar en la avenida Abancay a las 12 de la noche, oficio que realizó hasta 1956, abandonando su taller y dedicándose a recorrer el Perú y América Latina, recitando sus décimas y versos. Su cercanía con don Porfirio Vásquez, a quien conoció en 1946, influyó de manera decisiva en su formación como decimista. Asumió la tarea de revivir el folclore afroperuano mediante las presentaciones de una compañía teatral que organizó con su hermana Victoria Santa Cruz (1956-1961), a través de actuaciones radiofónicas y sus colaboraciones en el diario Expreso, El comercio y otras publicaciones. Debutó en 1958 en el Teatro Municipal de Buenos Aires, en Argentina, con la Compañía de Pancho cosa de Fierro Cascarón, dentro de un espectáculo denominado Ritmos Negros de Perú. También incursionó en el periodismo, en la radio y la televisión. Poco después incursiona fugazmente en la política, abandonándola al poco tiempo en 1961, y viajando a Brasil en 1963. Entre sus diversos viajes, Nicomedes siguió participando en eventos para promover la cultura afroperuana, entre los cuales destaca la dirección del primer Festival de Arte Negro, realizado en Cañete, en agosto de 1971. Otro de sus viajes tuvo como destino África en 1974, donde participa en el coloquio Négritude et Amérique Latine. Ese mismo año viajo a Cuba y a México, participando en una serie de programas televisivos. A estos países les siguieron Japón (1976), Colombia (1978), Cuba (1979), Panamá (1980). Desde 1981 se trasladó a Madrid, donde residió hasta su muerte. Allí fue periodista en Radio Exterior de España. Al mismo tiempo en 1987, colaboró en la preparación del disco de larga duración España en su folclor, sin descuidar sus presentaciones en diversos países. En 1989 impartió un seminario sobre la cultura africana en Santo Domingo (República Dominicana) y al año siguiente participó en la expedición Aventura 92, que recorrió puertos de México y Centroamérica. Afectado por un cáncer de riñón, falleció el 5 de febrero de 1992 después de haber sido intervenido quirúrgicamente en el Hospital Clínico de Madrid. Discografía Gente Morena (1957) Y su Conjunto Cumanana (1959; Canadá, 1994) Ingá (1960) Décimas y Poemas (1960) Cumanana: Poemas y Canciones (1964) Cumanana: Antología Afroperuana (1965,1970) Octubre Mes Morado (1964) Canto Negro (1968) Los Reyes del Festejo (1971) América Negra (1972) Nicomedes en Argentina (1973) Socabón: Introducción al Folklore Musical y Danzario de la Costa Peruana (1975) Ritmos Negros del Perú (1979) Décimas y Poemas Vol.2 (1980) España en su Folklore (1987) Obras escritas Décimas (1959, 1960, 1966). Cumanana (1960). Canto a mi Perú (1966). Décimas y poemas: antología (1971). Ritmos negros del Perú (Buenos Aires,1973). Rimactampu; rimas al Rímac (1972). La décima en el Perú (Lima 1982). Como has cambiado pelona (chincha 1959). Chala (1963). De ser como soy me alegro. A cocachos aprendí. Poema: meme neguito. [[wikipedia-http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nicomedes_Santa_Cruz_Gamarra

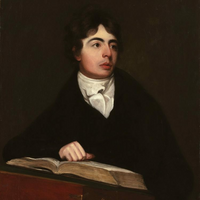

Robert Southey (/ˈsaʊði/ or /ˈsʌði/; August 12, 1774 in Bristol– March 21, 1843 in London) was an English poet of the Romantic school, one of the so-called “Lake Poets”, and Poet Laureate for 30 years from 1813 to his death in 1843. Although his fame has long been eclipsed by that of his contemporaries and friends William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Southey’s verse still enjoys some popularity. Southey was also a prolific letter writer, literary scholar, essay writer, historian and biographer. His biographies include the life and works of John Bunyan, John Wesley, William Cowper, Oliver Cromwell and Horatio Nelson. The last has rarely been out of print since its publication in 1813 and was adapted for the screen in the 1926 British film, Nelson. He was also a renowned scholar of Portuguese and Spanish literature and history, translating a number of works from those two languages into English and writing a History of Brazil (part of his planned History of Portugal, which he never completed) and a History of the Peninsular War. Perhaps his most enduring contribution to literary history is the children’s classic The Story of the Three Bears, the original Goldilocks story, first published in Southey’s prose collection The Doctor. He also wrote on political issues which led to a brief, non-sitting, spell as a Tory Member of Parliament. Life Robert Southey was born in Wine Street, Bristol, England, to Robert Southey and Margaret Hill. He was educated at Westminster School, London, (where he was expelled for writing an article in The Flagellant condemning flogging) and Balliol College, Oxford. Southey later said of Oxford, “All I learnt was a little swimming... and a little boating.” Experimenting with a writing partnership with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, most notably in their joint composition of The Fall of Robespierre, Southey published his first collection of poems in 1794. The same year, Southey, Coleridge, Robert Lovell and several others discussed creating an idealistic community ("pantisocracy") on the banks of the Susquehanna River in America: Southey was the first to reject the idea as unworkable, suggesting that they move the intended location to Wales, but when they failed to agree the plan was abandoned. In 1799 Southey and Coleridge were involved with early experiments with nitrous oxide (laughing gas), conducted by the Cornish scientist Humphry Davy. Southey married Edith Fricker at St. Mary Redcliffe, Bristol, on 14 November 1795. She was a sister of Sara Fricker, Coleridge’s wife. The Southeys made their home at Greta Hall, Keswick, in the Lake District, living on his tiny income. Also living at Greta Hall and supported by him were Sara Coleridge and her three children, after Coleridge abandoned them, as well as the widow of poet Robert Lovell and her son. In 1808 Southey met Walter Savage Landor, whose work he admired, and they became close friends. That same year he wrote Letters from England under the pseudonym Don Manuel Alvarez Espriella, an account of a tour supposedly from a foreigner’s viewpoint. It is considered to present the most accurate picture of English ways at the beginning of the 19th century. From 1809, Southey contributed to the Quarterly Review. He had become so well known by 1813 that he was appointed Poet Laureate after Walter Scott refused the post. In 1819, through a mutual friend (John Rickman), Southey met the leading civil engineer Thomas Telford and struck up a strong friendship. From mid-August to 1 October 1819, Southey accompanied Telford on an extensive tour of his engineering projects in the Scottish Highlands, keeping a diary of his observations. This was published in 1929 as Journal of a Tour in Scotland in 1819. He was also a friend of the Dutch poet Willem Bilderdijk, whom he met twice, in 1824 and 1826, at Bilderdijk’s home in Leiden. In 1837 Southey received a letter from Charlotte Brontë, seeking his advice on some of her poems. He wrote back praising her talents, but also discouraging her from writing professionally. He said “Literature cannot be the business of a woman’s life”. Years later, Brontë remarked to a friend that the letter was “kind and admirable; a little stringent, but it did me good.” In 1838, Edith died and Southey remarried, to Caroline Anne Bowles, also a poet, on 4 June 1839. Southey’s mind was giving way when he wrote a last letter to his friend Landor in 1839, but he continued to mention Landor’s name when generally incapable of mentioning any one. He died on 21 March 1843 and was buried in the churchyard of Crosthwaite Church, Keswick, where he had worshipped for forty years. There is a memorial to him inside the church, with an epitaph written by his friend, William Wordsworth. Many of his poems are still read by British schoolchildren, the best-known being The Inchcape Rock, God’s Judgement on a Wicked Bishop, After Blenheim (possibly one of the earliest anti-war poems) and Cataract of Lodore. As a prolific writer and commentator, Southey introduced or popularised a number of words into the English language. The term autobiography, for example, was used by Southey in 1809 in the Quarterly Review in which he predicted an “epidemical rage for autobiography”, which indeed has continued to the present day. Politics Although originally a radical supporter of the French Revolution, Southey followed the trajectory of his fellow Romantic poets Wordsworth and Coleridge towards conservatism. Embraced by the Tory establishment as Poet Laureate, and from 1807 in receipt of a yearly stipend from them, he vigorously supported the Liverpool government. He argued against parliamentary reform ("the railroad to ruin with the Devil for driver"), blamed the Peterloo Massacre on the allegedly revolutionary “rabble” killed and injured by government troops, and opposed Catholic emancipation. In 1817 he privately proposed penal transportation for those guilty of “libel” or “sedition”. He had in mind figures like Thomas Jonathan Wooler and William Hone, whose prosecution he urged. Such writers were guilty, he wrote in the Quarterly Review, of “inflaming the turbulent temper of the manufacturer and disturbing the quiet attachment of the peasant to those institutions under which he and his fathers have dwelt in peace.” Wooler and Hone were acquitted, but the threats caused another target, William Cobbett, to emigrate temporarily to the United States. In some respects, however, Southey was ahead of his time in his views on social reform. For example, he was an early critic of the evils which the new factory system brought to early 19th-century Britain. He was appalled by the conditions of life in towns like Birmingham and Manchester, and especially by the employment of children in factories, and was outspoken in his criticism of these things. He sympathised with the pioneering socialist plans of Robert Owen, advocated that the state promote public works to maintain high employment and called for universal education. Given his departure from radicalism, and his attempts to have former fellow travellers prosecuted, it is unsurprising that less successful contemporaries who kept the faith attacked Southey. They saw him as a selling out for money and respectability. In 1817 Southey was confronted with the surreptitious publication of a radical play, Wat Tyler, which he had written in 1794 at the height of his radical period. This was instigated by his enemies in an attempt to embarrass the Poet Laureate and highlight his apostasy from radical poet to supporter of the Tory establishment. One of his most savage critics was William Hazlitt. In his portrait of Southey, in The Spirit of the Age, he wrote: “He wooed Liberty as a youthful lover, but it was perhaps more as a mistress than a bride; and he has since wedded with an elderly and not very reputable lady, called Legitimacy.” Southey largely ignored his critics but was forced to defend himself when William Smith, a member of Parliament, rose in the House of Commons on 14 March to attack him. In a spirited response Southey wrote an open letter to the MP, in which he explained that he had always aimed at lessening human misery and bettering the condition of all the lower classes and that he had only changed in respect of “the means by which that amelioration was to be effected.” As he put it, “that as he learnt to understand the institutions of his country, he learnt to appreciate them rightly, to love, and to revere, and to defend them.” He was often mocked for what were seen as sycophantic odes to the king, most notably in Byron’s long ironic dedication of Don Juan to Southey. In the poem Southey is dismissed as insolent, narrow and shabby. This was based both on Byron’s disrespect for Southey’s literary talent, and his disdain for what he perceived as Southey’s hypocritical turn to conservative politics later in life. The source of much of the animosity between the two men can be traced back to Byron’s belief that Southey had spread rumours about him and Percy Shelley being in a “League of Incest” during their time on Lake Geneva in 1816, an accusation that Southey strenuously denied. In response, Southey attacked what he called the Satanic School among modern poets in the preface to his poem, A Vision of Judgement, written following the death of George III. While not referring to Byron by name, it was clearly directed at him, and Byron retaliated with The Vision of Judgment, a brilliant parody of Southey’s poem. Without his prior knowledge, the Earl of Radnor, an admirer of his work, had Southey returned as MP for the latter’s pocket borough seat of Downton in Wiltshire at the 1826 general election as an opponent of Catholic emancipation. However Southey refused to sit in the House of Commons, causing a by-election in December that year, pleading he did not have a large enough estate to support him through political life, did not want to take on the hours full attendance required, wanted to continue living in the Lake District, and preferred to defend the Church of England in writing rather than speech. He declared that ‘for me to change my scheme of life and go into Parliament, would be to commit a moral and intellectual suicide’; and his friend John Rickman, a Commons clerk, noted that ‘prudential reasons would forbid his appearing in London’ as a Member. In 1835 he declined the offer of a baronetcy but accepted a life pension of £300 a year from Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel. Southey is buried in the churchyard of Crosthwaite Parish Church in Cumbria. Honours and Memberships Elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1822. Member of the Royal Spanish Academy. List of works * The Fall of Robespierre (1794) * Joan of Arc (1796) * Icelandic Poetry, or The Edda of Sæmund (1797) * Poems (1797–1799) * Letters Written During a Short Residence in Spain and Portugal (1797) * St. Patrick’s Purgatory (1798) * After Blenheim (1798) * The Devil’s Thoughts (1799). Revised ed. pub. in 1827 as “The Devil’s Walk”. * English Eclogues (1799) * The Old Man’s Comforts and How He Gained Them (1799) * Thalaba the Destroyer (1801) * The Inchcape Rock (1802) * Madoc (1805) * Letters from England: By Don Manuel Alvarez Espriella (1807), the observations of a fictitious Spaniard. * Chronicle of the Cid, from the Spanish (1808) * The Curse of Kehama (1810) * History of Brazil (3 vols.) (1810–1819) * The Life of Horatio, Lord Viscount Nelson (1813) * Roderick the Last of the Goths (1814) * Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte D’Arthur (1817) * Wat Tyler: A Dramatic Poem (1817) * Cataract of Lodore (1820) * The Life of Wesley; and Rise and Progress of Methodism (2 vols.) (1820) * What Are Little Boys Made Of? (1820) * The Vision of Judgement (1821) * History of the Peninsular War, 1807-1814 (3 vols.) (1823-1832) * Sir Thomas More; or, Colloquies on the Progress and Prospects of Society (1829) * The Works of William Cowper (15 vols.) (ed.) (1833-1837) * Lives of the British Admirals, with an Introductory View of the Naval History of England (5 vols.) (1833-40); republished as “English Seamen” in 1895. * The Doctor (7 vols.) (1834-1847). Includes The Story of the Three Bears (1837). * The Poetical Works of Robert Southey, Collected by Himself (1837) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Southey

Welcome!! I have some emotions that have poetic symphony. I have some philosophy and my own stories and experiences in my own perspective; I have not judged them whether they are symmetrical with anyone or differentiate with others. I love writing about the bad luck I bear, the curse I fear and the death, ridiculously, I dare. I am grateful if you read - just like a sudden visitor of an unknown grave, someone came, stood, smiled and wished - "Rest In Peace". I was born in 1979, July 26 just at 12 am. I have no siblings. My two assets are everything, One I lost in 2004; My father; Still one I have, My mother. I am an MBA of University of Chittagong. I have served a lot of companies, Branded-Non branded, Multinational-Local, Authorized-Unknown, Financial-Not Financial, Established-Liquidated, Rising-Falling, Fortunate-Misfortune, Proprietor-Public etc. I like job devotion, I hate impose of discrimination, I am always leader at the beginning, however demonstrator at the ending. I belief Pragmatic is not Truth, Real means partial Truth. I decided to suicide. Before that, I want to keep my creation safe, where they will obscure but they will survive. I can never get the recognition. Better my creations need freedom anywhere in the world. So welcome again my friend before I decay. Thank you.

Rogelio Sinán, seudónimo de Bernardo Domínguez Alba (Taboga, 1902 - Panamá, 1994) fue un escritor vanguardista panameño. Inició sus estudios en el Colegio De La Salle y se graduó de bachiller en el Instituto Nacional de Panamá (1924). Realizó estudios universitarios en Chile, en donde conoció a los poetas Pablo Neruda y Gabriela Mistral. Siguiendo consejo de la poetisa, viaja a Italia a aprender italiano; fue allí donde se empapó de los -ismos (dadaísmo, surrealismo, creacionismo, ultrarealísmo, etc.) en boga en Europa en esa época y que serían la base de su obra posteriormente. En 1989, la Universidad de Panamá lo distinguió con el Doctorado Honori0 Vida profesional En Panamá, ejerció como profesor de español, en el Instituto Nacional y de arte dramático en la Universidad de Panamá. Posteriormente desempeñó el cargo de Primer Secretario de la Embajada de Panamá en México y, en 1938, como Cónsul de Panamá en Calcuta, India. Nuevamente en Panamá, en 1946 fue Director del Departamento de Bellas Artes y Publicaciones del Ministerio de Educación. Fue miembro de la Academia Panameña de la Lengua. Premios y distinciones * Casa de Rogelio Sinán en la Isla de Taboga * Premio Ricardo Miró de Novela por su libro "Plenilunio". Panamá, 1943. * Premio Interamericano de Cuento, por su cuento "La boina roja". México, 1949. * Premio "Ricardo Miró" de Poesía por su libro "Semana Santa en la niebla". Panamá, 1949. * Premio "Ricardo Miró" de Novela por su libro "La isla mágica". Panamá, 1977. + El gobierno panameño le otorgó tres condecoraciones en vida. La Academia Panameña de * la Lengua le otorgó la Primera Orden al Mérito Intelectual. * Actualmente se entregan tres premios literarios en su honor: el Premio Centroamericano de Literatura "Rogelio Sinán", que desde 1996 convoca para libros inéditos en los géneros cuento, novela y poesía la Universidad Tecnológica de Panamá; y la Condecoración + "Rogelio Sinán" que la República de Panamá otorga cada dos años a un autor panameño por la excelencia en la obra de toda una vida. Obra literaria La obra con que Sinán se dio a conocer fue la colección de poemas Onda (1929), publicado en Roma, Italia. Con este poemario, Sinán rompe con la estética del modernismo, cultivada por los poetas románticos panameños hasta la fecha, e inicia el vanguardismo en Panamá. Esta obra representó un cambio en la visión poética del mundo y en la forma de expresión con respecto a la poesía que se practicaba en Panamá en ese momento. Aparte de la poesía, Sinán cultivó el género del cuento y la novela, y en menor medida el teatro infantil y el ensayo. Poesía * Onda. Casa Editrice, Roma, Italia, 1929; Segunda edición, Revista "Lotería", No. 11, Panamá, septiembre de 1964; Tercera edición, Ediciones Formato Dieciséis, Universidad de Panamá, 1983. * Incendio. Cuadernos de poesía "Mar del Sur", No. 1, Panamá, 1944. * Semana Santa en la niebla. Panamá, 1949; Segunda edición, Dirección Nacional de Cultura del Ministerio de Educación, Panamá, 1969. * Saloma sin salomar. Dirección Nacional de Publicaciones del Ministerio de Educación, Panamá, 1969. * Poesía completa de Rogelio Sinán. Prólogo de Elsie Alvarado de Ricord, compilación e introducción de Enrique Jaramillo Levi. Universidad Tecnológica de Panamá, abril de 2000. Cuento * A la orilla de las estatuas maduras. Panamá, 1946; Secretaría de Educación Pública, México, 1967. * Todo un conflicto de sangre. Panamá, 1946. * Dos aventuras en el lejano oriente. Panamá, 1947; Panamá, 1953. * La boina roja y otros cuentos. Panamá, 1954; Ediciones del Ministerio de Educación, Panamá, 1961; Madrid, 1972. Posteriormente se han seguido publicando múltiples ediciones sin las últimas tres palabras del título original. * Los pájaros del sueño. Panamá, 1957. * Cuna común. Ediciones de la revista “Tareas”, Panamá, 1963. * Cuentos de Rogelio Sinán. Editorial Universitaria Centroamericana, San José (Costa Rica), 1971; 1972. * Homenaje a Rogelio Sinán. Poesía y Cuento. Prólogo de Enrique Jaramillo Levi, Editorial Signos, México, 1982. * El candelabro de los malos ofidios y otros cuentos. Editorial Signos, Panamá, 1982. Novela * Plenilunio. Panamá,1947; México, 1953; Panamá, 1961; Madrid, 1972. Posteriormente se ha seguido publicando múltiples ediciones en Panamá. * La isla mágica. Instituto Nacional de Cultura, Panamá, 1979; Segunda edición, Ediciones * Casa de las Américas, Habana, Cuba, 1985 . Teatro infantil * La cucarachita mandinga (farsa, adaptación de una historia tradicional de la India). Panamá, 1937; Segunda edición, Instituto Nacional de Cultura, Panamá, 1992. * Chiquilinga (farsa). Panamá, 1961. * Lobo go home (escenificada en Panamá, pero no publicada como libro). Ensayo * Los valores humanos en la lírica de Maples Arce. México, 1959. * Otros ensayos aparecidos en revistas y periódicos en diversas épocas fueron reunidos por Enrique Jaramillo Levi en: “Maga, Revista panameña de cultura”, No. 5-6, Panamá, enero-junio de 1985. REferencias Wikipedia-http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rogelio_Sin%C3%A1n

SOY VENEZOLANO (47 AÑOS) CASADO Y CON TRES HIJOS. SOY TEÓLOGO (TSU EN TEOLOGÍA), POETA, COMPOSITOR MUSICAL Y MATEMÁTICO. MIS ARTÍCULOS EN REVISTAS MATEMÁTICAS. Ya tengo publicados 4 artículos publicados (en Venezuela, Ecuador y Costa Rica) en el área de teoría de números que pueden accesarse por medio de los siguientes links: *https://lnkd.in/ewSCK9Fp *https://lnkd.in/e_uujDXQ *https://lnkd.in/eGxf27bQ *https://lnkd.in/eYWNPaYW Quisiera vieran mis artículos. Están por salir 2 artículos más y un libro en España (que será versión de uno de los artículos publicados). Mi meta es llegar a obtener reconocimiento internacional y doctorados honoris causa en matemáticas. SIEMPRE HE TRABAJADO POR CUENTA PROPIA Quisiera encontrar financiamiento para seguir desarrollando mi investigación, obtener computadora y otros recursos para trabajar mucho mejor y lograr a la meta de publicar mínimo 30 artículos. Si hay alguien interesado en ayudarme comunicarse conmigo por whatsapp al +584121511275.

Delmore Schwartz (December 8, 1913– July 11, 1966) was an American poet and short story writer. Biography Schwartz was born in 1913 in Brooklyn, New York, where he also grew up. His parents, Harry and Rose, both Romanian Jews, separated when Schwartz was nine, and their divorce had a profound effect on him. In 1930, Schwartz’s father suddenly died at the age of 49. Though Harry had accumulated a good deal of wealth from his dealings in the real estate business, Delmore only inherited a small amount of that money as the result of the shady dealings of the executor of Harry’s estate. According to Schwartz’s biographer, James Atlas, "Delmore continued to hope that he would eventually receive his legacy [even] as late as 1946.” Schwartz spent time at Columbia University and the University of Wisconsin before finally graduating from New York University in 1935. He then did some graduate work in philosophy at Harvard University, where he studied with the philosopher Alfred North Whitehead, but left and returned to New York without receiving a degree. Soon thereafter, he made his parents’ disastrous marriage the subject of his most famous short story, “In Dreams Begin Responsibilities”, which was published in 1937 in the first issue of Partisan Review. This story and other short stories and poems became his first book, also entitled In Dreams Begin Responsibilities, published in 1938 when Schwartz was only 25 years old. The book was well received, and made him a well-known figure in New York intellectual circles. His work received praise from some of the most respected people in literature, including T. S. Eliot, William Carlos Williams, and Ezra Pound, and Schwartz was considered one of the most gifted and promising young writers of his generation. According to James Atlas, Allen Tate responded to the book by stating that "[Schwartz’s] poetic style marked 'the first real innovation we’ve had since Eliot and Pound.'” In 1937, he also married Gertrude Buckman, a book reviewer for Partisan Review, whom he divorced after six years. For the next couple of decades, he continued to publish stories, poems, plays, and essays, and edited the Partisan Review from 1943 to 1955, as well as The New Republic. Schwartz was deeply upset when his epic poem, Genesis, which he published in 1943 and hoped would stand alongside other Modernist epics like The Waste Land and The Cantos as a masterpiece, received a negative critical response. Later, in 1948, he married the much younger novelist, Elizabeth Pollet. This relationship also ended in divorce. In 1959, he became the youngest-ever recipient of the Bollingen Prize, awarded for a collection of poetry he published that year, Summer Knowledge: New and Selected Poems. His poetry differed from his stories in that it was less autobiographical and more philosophical. His verse also became increasingly abstract in his later years. He taught creative writing at six universities, including Syracuse, Princeton, and Kenyon College. In addition to being known as a gifted writer, Schwartz was considered a great conversationalist and spent much time entertaining friends at the White Horse Tavern in New York City. Much of Schwartz’s work is notable for its philosophical and deeply meditative nature, and the literary critic, R.W. Flint, wrote that Schwartz’s stories were “the definitive portrait of the Jewish middle class in New York during the Depression.” In particular, Schwartz emphasized the large divide that existed between his generation (which came of age during the Depression) and his parents’ generation (who had often come to the United States as first-generation immigrants and whose idealistic view of America differed greatly from his own). In another take on Schwartz’s fiction, Morris Dickstein wrote that “Schwartz’s best stories are either poker-faced satirical takes on the bohemians and outright failures of his generation, as in 'The World Is a Wedding’ and 'New Year’s Eve,' or chronicles of the distressed lives of his parents’ generation, for whom the promise of American life has not panned out.” Schwartz was unable to repeat or build on his early successes later in life as a result of alcoholism and mental illness, and his last years were spent in reclusion at the Columbia Hotel in New York City. In fact, Schwartz was so isolated from the rest of the world that when he died on July 11, 1966, at age 52, of a heart attack, two days passed before his body was identified at the morgue. Schwartz was interred at Cedar Park Cemetery, in Emerson, New Jersey. A selection of his short stories was published posthumously in 1978 under the title In Dreams Begin Responsibilities and Other Stories and was edited by James Atlas who had written a biography of Schwartz, Delmore Schwartz: The Life of An American Poet, two years earlier. Later, another collection of Schwartz’s work, Screeno: Stories & Poems, was published in 2004. This collection contained fewer stories than In Dreams Begin Responsibilities and Other Stories but it also included a selection of some of Schwartz’s best-known poems like “The Heavy Bear Who Goes With Me” and “In The Naked Bed, In Plato’s Cave”. Screeno also featured an introduction by the fiction writer and essayist, Cynthia Ozick. Tributes to Schwartz One of the earliest well-known tributes to Schwartz came from Schwartz’s friend, fellow poet Robert Lowell, who published the poem “To Delmore Schwartz” in 1959 (while Schwartz was still alive) in the book Life Studies. In it Lowell reminisces about the time that the two poets lived together in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1946, writing that they were "underseas fellows, nobly mad,/ we talked away our friends.” One year following Schwartz’s death, in 1967, his former student at Syracuse University, the rock musician Lou Reed, dedicated his song “European Son” to Schwartz (although the lyrics themselves made no direct reference to Schwartz). Then, in 1968, Schwartz’s friend and peer, fellow poet John Berryman, dedicated his book His Toy, His Dream, His Rest “to the sacred memory of Delmore Schwartz,” including 12 elegiac poems about Schwartz in the book. In "Dream Song #149," Berryman wrote of Schwartz, In the brightness of his promise, unstained, I saw him thro’ the mist of the actual blazing with insight, warm with gossip thro’ all our Harvard years when both of us were just becoming known I got him out of a police-station once, in Washington, the world is tref and grief too astray for tears. The most ambitious literary tribute to Schwartz came in 1975 when Saul Bellow, a one-time protégé of Schwartz’s, published his Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Humboldt’s Gift which was based on his relationship with Schwartz. Although the character of Von Humboldt Fleischer is Bellow’s portrait of Schwartz during Schwartz’s declining years, the book is actually a testament to Schwartz’s lasting artistic influence on Bellow. Although he is a genius, the Fleischer/Schwartz character struggles financially and has trouble finding a secure university teaching position. He becomes increasingly paranoid and jealous of the success of the main character, Charlie Citrine (who is based upon Bellow himself), becoming isolated and descending into alcoholism and madness. Lou Reed’s 1982 album The Blue Mask included his second Schwartz homage with the song “My House”. The song is a more direct tribute to Schwartz than the above-mentioned “European Son” in that the lyrics of “My House” are about Reed’s relationship with Schwartz. In the song, Reed writes that Schwartz “was the first great man that I ever met”. Much later, in the June 2012 issue of Poetry magazine, Lou Reed published a short prose tribute to Schwartz entitled “O Delmore How I Miss You.” In the piece, Reed quotes and references a number of Schwartz’s short stories and poems including “In Dreams Begin Responsibilities,” “The World is a Wedding,” and “The Heavy Bear Who Goes With Me.” “O Delmore How I Miss You” was re-published as the preface to the New Directions 2012 reissue of Schwartz’s posthumously published story collection In Dreams Begin Responsibilities and Other Stories. In John A. McDermott’s poetry collection, The Idea of God in Tennessee, he includes a poem written for and referencing Schwartz, titled The Poet’s Body, Unclaimed in the Manhattan Morgue. The poem makes mention of Schwartz’s writing, daily habits, and death. Cultural references Scott Spencer uses the final six lines of Schwartz’s poem “I Am a Book I Neither Wrote nor Read” as an epigraph for his National Book Award nominated novel, Endless Love. The words “endless love” are the final two words of that poem. In the film Star Trek Generations, the villain Tolian Soran quotes from Schwartz’s poem, “Calmly We Walk Through This April’s Day”, telling Captain Jean-Luc Picard, “They say time is the fire in which we burn.” Playwright Philip Ridley uses the same line as one of the epigraphs for his 2012 play Shivered. The German symphonic metal band Agathodaimon uses the line “Time is the fire” as the title to one of the songs on the album Phoenix. Grant Morrison named a story in his DC Comics miniseries Multiversity, Pax Americana, after the same line as well as quoting it on the cover. In 1996, Donald Margulies wrote the play Collected Stories, in which the aging writer and teacher Ruth Steiner (a fictional character) reveals that she once had a great affair in her youth with Delmore Schwartz in Greenwich Village (during the period of time when Schwartz was in declining health from alcoholism and mental illness) to her young student, Lisa. Lisa then controversially uses the affair revelation as the basis for a successful novel. The play was produced twice off-Broadway and once on Broadway. Published works The Poets’ Pack (Rudge, New York, 1932), school anthology including four poems by Schwartz. In Dreams Begin Responsibilities. (New Directions, 1938), ISBN 978-0-8112-0680-8, a collection of short stories and poems. Shenandoah and Other Verse Plays (New Directions, 1941). Genesis: Book One (New Directions, 1943), book-length poem about the growth of a human being. The World Is a Wedding (New Directions, 1948), a collection of short stories. Vaudeville for a Princess and Other Poems (New Directions, 1950). Summer Knowledge: New and Selected Poems. (New Directions, 1959; reprinted 1967), ISBN 978-0-8112-0191-9. Successful Love and Other Stories (Corinth Books, 1961; Persea Books, 1985), ISBN 978-0-89255-094-4 Published posthumously Donald Dike, David Zucker (ed.) Selected Essays (1970; University of Chicago Press, 1985), ISBN 978-0-226-74214-4 In Dreams Begin Responsibilities and Other Stories (New Directions, 1978), a short story collection. Letters of Delmore Schwartz, ed. Robert Phillips (1984) ISBN 978-0-86538-048-6 The Ego Is Always at the Wheel: Bagatelles, ed. Robert Phillips (1986), a collection of humorously whimsical short essays Last and Lost Poems. ed. Robert Phillips (New Directions, 1989) ISBN 978-0-8112-1096-6 Screeno: Stories & Poems. New Directions. 2004. ISBN 978-0-8112-1573-2. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Delmore_Schwartz

William Shenstone (18 November 1714– 11 February 1763) was an English poet and one of the earliest practitioners of landscape gardening through the development of his estate, The Leasowes. Biography Son of Thomas Shenstone and Anne Penn, daughter of William Penn of Harborough Hall, then in Hagley (now Blakedown), Shenstone was born at the Leasowes, Halesowen. At that time this was an enclave of Shropshire within the county of Worcestershire and now in the West Midlands. Shenstone received part of his formal education at Halesowen Grammar School (now The Earls High School). In 1741, Shenstone became bailiff to the feoffees of Halesowen Grammar School. While attending Solihull School, he began a lifelong friendship with Richard Jago. He went up to Pembroke College, Oxford in 1732 and made another firm friend there in Richard Graves, the author of The Spiritual Quixote. Shenstone took no degree, but, while still at Oxford, he published Poems on various occasions, written for the entertainment of the author (1737). This edition was intended for private circulation only but, containing the first draft of The Schoolmistress, it attracted some wider attention. Shenstone tried hard to suppress it but in 1742 he published anonymously a revised draft of The Schoolmistress, a Poem in imitation of Spenser. The inspiration of the poem was Sarah Lloyd, teacher of the village school where Shenstone received his first education. Isaac D’Israeli contended that Robert Dodsley had been misled in publishing it as one of a sequence of Moral Poems, its intention having been satirical, as evidenced by the ludicrous index appended to its original publication. In 1741 he published The Judgment of Hercules. He inherited the Leasowes estate, and retired there in 1745 to undertake what proved the chief work of his life, the beautifying of his property. He embarked on elaborate schemes of landscape gardening which gave The Leasowes a wide celebrity (see ferme ornée), but sadly impoverished the owner. Shenstone was not a contented recluse. He desired constant admiration of his gardens, and he never ceased to lament his lack of fame as a poet. Shenstone died unmarried. Critical appraisal Shenstone’s poems of nature were written in praise of her most artificial aspects, but the emotions they express were obviously genuine. His Schoolmistress was admired by Oliver Goldsmith, with whom Shenstone had much in common, and his Elegies written at various times and to some extent biographical in character won the praise of Robert Burns who, in the preface to Poems, chiefly in the Scottish Dialect (1786), called him... that celebrated poet whose divine elegies do honour to our language, our nation and our species. The best example of purely technical skill in his works is perhaps his success in the management of the anapaestic trimeter in his Pastoral Ballad in Four Parts (written in 1743), but first printed in Dodsley’s Collection of Poems (vol. iv., 1755). Arthur Schopenhauer mentions Shenstone in his discussion of equivocation. "[C]oncepts", Schopenhauer asserted, “which in and by themselves contain nothing improper, yet the actual case brought under them leads to an improper conception” are called equivocations. He continued: But a perfect specimen of a sustained and magnificent equivocation is Shenstone’s incomparable epitaph on a justice of the peace, which in its high-sounding lapidary style appears to speak of noble and sublime things, whereas under each of their concepts something quite different is to be subsumed, which appears only in the last word of all as the unexpected key to the whole, and the reader discovers with loud laughter that he has read merely a very obscene equivocation. Bibliography * Shenstone’s works were first published by his friend Robert Dodsley (3 vols., 1764–1769). The second volume contains Dodsley’s description of the Leasowes. The last, consisting of correspondence with Graves, Jago and others, appeared after Dodsley’s death. Other letters of Shenstone’s are included in Select Letters (ed. Thomas Hill 1778). The letters of Lady Luxborough (née Henrietta St John) to Shenstone were printed by T. Dodsley in 1775; much additional correspondence is preserved in the British Museum letters to Lady Luxborough (Add. MS. 28958), Dodsley’s letters to Shenstone (Add. MS. 28959), and correspondence between Shenstone and Bishop Percy from 1757 to 1763 the last being of especial interest; To Shenstone was due the original suggestion of Percy’s Reliques, a service which would alone entitle him to a place among the precursors of the romantic movement in English literature. * In a letter written in 1741 Shenstone became the first person to record the use of “floccinaucinihilipilification”. In the first edition of the Oxford English Dictionary this was recognised as the longest word in the English language. Memorials * One of the five houses of Solihull School is named after him. * One of the four houses of The Earls High School (formerly Halesowen Grammar School) is named after him. * Solihull School’s annual publication is named after him– The Shenstonian. * Louis-René Girardin built a memorial in the French town of Ermenonville. * A prominent public house (pub) in Halesowen (Queensway) is named “The William Shenstone”. The walls are adorned with engravings of The Leasowes in Shenstone’s time. * Two roads in the area near to his home in the Leasowes Park are named in his honour: Shenstone Valley Road and Shenstone Avenue. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Shenstone

Florence Margaret Smith, known as Stevie Smith (20 September 1902– 7 March 1971) was an English poet and novelist. Life Stevie Smith, born Florence Margaret Smith in Kingston upon Hull, was the second daughter of Ethel and Charles Smith. She was called “Peggy” within her family, but acquired the name “Stevie” as a young woman when she was riding in the park with a friend who said that she reminded him of the jockey Steve Donoghue. Her father was a shipping agent, a business that he had inherited from his father. As the company and his marriage began to fall apart, he ran away to sea and Smith saw very little of her father after that. He appeared occasionally on 24-hour shore leave and sent very brief postcards ("Off to Valparaiso, Love Daddy"). When she was three years old she moved with her mother and sister to Palmers Green in North London where Smith would live until her death in 1971. She resented the fact that her father had abandoned his family. Later, when her mother became ill, her aunt Madge Spear (whom Smith called “The Lion Aunt”) came to live with them, raised Smith and her elder sister Molly and became the most important person in Smith’s life. Spear was a feminist who claimed to have “no patience” with men and, as Smith wrote, “she also had 'no patience’ with Hitler”. Smith and Molly were raised without men and thus became attached to their own independence, in contrast to what Smith described as the typical Victorian family atmosphere of “father knows best”. When Smith was five she developed tubercular peritonitis and was sent to a sanatorium near Broadstairs, Kent, where she remained for three years. She related that her preoccupation with death began when she was seven, at a time when she was very distressed at being sent away from her mother. Death and fear fascinated her and provide the subjects of many of her poems. Her mother died when Smith was 16. When suffering from the depression to which she was subject all her life she was so consoled by the thought of death as a release that, as she put it, she did not have to commit suicide. She wrote in several poems that death was “the only god who must come when he is called”. Smith suffered throughout her life from an acute nervousness, described as a mix of shyness and intense sensitivity. In the Poem “A House of Mercy”, she wrote of her childhood house in North London: It was a house of female habitation, Two ladies fair inhabited the house, And they were brave. For although Fear knocked loud Upon the door, and said he must come in, They did not let him in. Smith was educated at Palmers Green High School and North London Collegiate School for Girls. She spent the remainder of her life with her aunt, and worked as private secretary to Sir Neville Pearson with Sir George Newnes at Newnes Publishing Company in London from 1923 to 1953. Despite her secluded life, she corresponded and socialised widely with other writers and creative artists, including Elisabeth Lutyens, Sally Chilver, Inez Holden, Naomi Mitchison, Isobel English and Anna Kallin. After she retired from Sir Neville Pearson’s service following a nervous breakdown she gave poetry readings and broadcasts on the BBC that gained her new friends and readers among a younger generation. Sylvia Plath became a fan of her poetry and sent Smith a letter in 1962, describing herself as “a desperate Smith-addict.” Plath expressed interest in meeting in person but committed suicide soon after sending the letter. Smith was described by her friends as being naive and selfish in some ways and formidably intelligent in others, having been raised by her aunt as both a spoiled child and a resolutely autonomous woman. Likewise, her political views vacillated between her aunt’s Toryism and her friends’ left-wing tendencies. Smith was celibate for most of her life, although she rejected the idea that she was lonely as a result, alleging that she had a number of intimate relationships with friends and family that kept her fulfilled. She never entirely abandoned or accepted the Anglican faith of her childhood, describing herself as a “lapsed atheist”, and wrote sensitively about theological puzzles;"There is a God in whom I do not believe/Yet to this God my love stretches." Her 14-page essay of 1958, “The Necessity of Not Believing”, concludes: “There is no reason to be sad, as some people are sad when they feel religion slipping off from them. There is no reason to be sad, it is a good thing.” Smith died of a brain tumour on 7 March 1971. Her last collection, Scorpion and other Poems was published posthumously in 1972, and the Collected Poems followed in 1975. Three novels were republished and there was a successful play based on her life, Stevie, written by Hugh Whitemore. It was filmed in 1978 by Robert Enders and starred Glenda Jackson and Mona Washbourne. Fiction Smith wrote three novels, the first of which, Novel on Yellow Paper, was published in 1936. Apart from death, common subjects in her writing include loneliness; myth and legend; absurd vignettes, usually drawn from middle-class British life, war, human cruelty and religion. All her novels are lightly fictionalised accounts of her own life, which got her into trouble at times as people recognised themselves. Smith said that two of the male characters in her last book are different aspects of George Orwell, who was close to Smith. There were rumours that they were lovers; he was married to his first wife at the time. Novel on Yellow Paper (Cape, 1936) Smith’s first novel is structured as the random typings of a bored secretary, Pompey. She plays word games, retells stories from classical and popular culture, remembers events from her childhood, gossips about her friends and describes her family, particularly her beloved Aunt. As with all Smith’s novels, there is an early scene where the heroine expresses feelings and beliefs which she will later feel significant, although ambiguous, regret for. In Novel on Yellow Paper that belief is anti-Semitism, where she feels elation at being the “only Goy” at a Jewish party. This apparently throwaway scene acts as a timebomb, which detonates at the centre of the novel when Pompey visits Germany as the Nazis are gaining power. With horror, she acknowledges the continuity between her feeling “Hurray for being a Goy” at the party and the madness that is overtaking Germany. The German scenes stand out in the novel, but perhaps equally powerful is her dissection of failed love. She describes two unsuccessful relationships, first with the German Karl and then with the suburban Freddy. The final section of the novel describes with unusual clarity the intense pain of her break-up with Freddy. Over the Frontier (Cape, 1938) Smith herself dismissed her second novel as a failed experiment, but its attempt to parody popular genre fiction to explore profound political issues now seems to anticipate post-modern fiction. If anti-Semitism was one of the key themes of Novel on Yellow Paper, Over the Frontier is concerned with militarism. In particular, she asks how the necessity of fighting Fascism can be achieved without descending into the nationalism and dehumanisation that fascism represents. After a failed romance the heroine, Pompey, suffers a breakdown and is sent to Germany to recuperate. At this point the novel changes style radically, as Pompey becomes part of an adventure/spy yarn in the style of John Buchan or Dornford Yates. As the novel becomes increasingly dreamlike, Pompey crosses over the frontier to become a spy and soldier. If her initial motives are idealistic, she becomes seduced by the intrigue and, ultimately, violence. The vision Smith offers is a bleak one: “Power and cruelty are the strengths of our lives, and only in their weakness is there love.” The Holiday (Chapman and Hall, 1949) Smith’s final novel is her own favourite, and most fully realised. It is concerned with personal and political malaise in the immediate post-war period. Most of the characters are either employed in the army or civil service in post-war reconstruction, and its heroine, Celia, works for the Ministry as a cryptographer and propagandist. The Holiday describes a series of hopeless relationships. Celia and her cousin Caz are in love, but cannot pursue their affair since it is believed that, because of their parents’ adultery, they are half-brother and sister. Celia’s other cousin Tom is in love with her, Basil is love with Tom, Tom is estranged from his father, Celia’s beloved Uncle Heber, who pines for a reconciliation; and Celia’s best friend Tiny longs for the married Vera. These unhappy, futureless but intractable relationships are mirrored by the novel’s political concerns. The unsustainability of the British Empire and the uncertainty over Britain’s post-war role are constant themes, and many of the characters discuss their personal and political concerns as if they were seamlessly linked. Caz is on leave from Palestine and is deeply disillusioned, Tom goes mad during the war, and it is telling that the family scandal that blights Celia and Caz’s lives took place in India. Just as Pompey’s anti-semitism was tested in Novel on Yellow Paper, so Celia’s traditional nationalism and sentimental support for colonialism is challenged throughout The Holiday. Poetry Smith’s first volume of poetry, the self-illustrated A Good Time Was Had By All, was published in 1937 and established her as a poet. Soon her poems were found in periodicals. Her style was often very dark; her characters were perpetually saying “goodbye” to their friends or welcoming death. At the same time her work has an eerie levity and can be very funny though it is neither light nor whimsical. “Stevie Smith often uses the word 'peculiar’ and it is the best word to describe her effects” (Hermione Lee). She was never sentimental, undercutting any pathetic effects with the ruthless honesty of her humour. “A good time was had by all” itself became a catch phrase, still occasionally used to this day. Smith said she got the phrase from parish magazines, where descriptions of church picnics often included this phrase. This saying has become so familiar that it is recognised even by those who are unaware of its origin. Variations appear in pop culture, including “Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!” by the Beatles. Though her poems were remarkably consistent in tone and quality throughout her life, their subject matter changed over time, with less of the outrageous wit of her youth and more reflection on suffering, faith and the end of life. Her best-known poem is “Not Waving but Drowning”. She was awarded the Cholmondeley Award for Poets in 1966 and won the Queen’s Gold Medal for poetry in 1969. She published nine volumes of poems in her lifetime (three more were released posthumously).

Hey everyone, I'm Erik. I've been writing poetry for about 10 years now, but I started to take it serious about a year and a half ago. A lot of my works are personal/have personal beliefs attached to them, I also want to shake things up a bit with my writing. I hope you like what I have to offer, and if you want to know any thing else find me on facebook or twitter (Skaarcia Vega) @Erik_Skaarnes.

Matilde Kirilovsky de Creimer (Berisso, 24 de febrero de 1912 - La Plata, 13 de septiembre de 2000), también conocida por su pseudónimo literario Matilde Alba Swann, fue una escritora, poetisa, periodista y abogada argentina. Fue una de las primeras mujeres que obtuvo el título de abogada en la Universidad Nacional de La Plata, provincia de Buenos Aires, en el año 1933. Publicó ocho libros de poesía e innumerables artículos periodísticos. Fue corresponsal de guerra para el diario El Día en la guerra de Malvinas. También se desempeñó como presidenta de la Filial La Plata de la Sociedad Argentina de Escritores.

Jack Spicer (January 30, 1925– August 17, 1965) was an American poet often identified with the San Francisco Renaissance. In 2009, My Vocabulary Did This to Me: The Collected Poetry of Jack Spicer won the American Book Award for poetry. Life and work Spicer was born in Los Angeles, where he later graduated from Fairfax High School in 1942, and attended the University of Redlands from 1943-45. He spent most of his writing-life in San Francisco and spent the years 1945 to 1950 and 1952 to 1955 at the University of California, Berkeley, where he began writing, doing work as a research-linguist, and publishing some poetry (though he disdained publishing). During this time he searched out fellow poets, but it was through his alliance with Robert Duncan and Robin Blaser that Spicer forged a new kind of poetry, and together they referred to their common work as the Berkeley Renaissance. The three, who were all gay, also educated younger poets in their circle about their “queer genealogy”, Rimbaud, Lorca, and other gay writers. Spicer’s poetry of this period is collected in One Night Stand and Other Poems (1980). His Imaginary Elegies, later collected in Donald Allen’s The New American Poetry 1945-1960 anthology, were written around this time. In 1954, he co-founded the Six Gallery in San Francisco, which soon became famous as the scene of the October 1955 Six Gallery reading that launched the West Coast Beat movement. In 1955, Spicer moved to New York and then to Boston, where he worked for a time in the Rare Book Room of Boston Public Library. Blaser was also in Boston at this time, and the pair made contact with a number of local poets, including John Wieners, Stephen Jonas, and Joe Dunn. Spicer returned to San Francisco in 1956 and started working on After Lorca. This book represented a major change in direction for two reasons. Firstly, he came to the conclusion that stand-alone poems (which Spicer referred to as his one-night stands) were unsatisfactory and that henceforth he would compose serial poems. In fact, he wrote to Blaser that 'all my stuff from the past (except the Elegies and Troilus) looks foul to me.' Secondly, in writing After Lorca, he began to practice what he called “poetry as dictation”. His interest in the work of Federico García Lorca, especially as it involved the cante jondo ideal, also brought him near the poetics of the deep image group. The Troilus referred to was Spicer’s then unpublished play of that name. The play finally appeared in print in 2004, edited by Aaron Kunin, in issue 3 of No - A Journal of the Arts. In 1957, Spicer ran a workshop called Poetry as Magic at San Francisco State College, which was attended by Duncan, Helen Adam, James Broughton, Joe Dunn, Jack Gilbert, and George Stanley. He also participated in, and sometimes hosted, Blabbermouth Night at a literary bar called The Place. This was a kind of contest of improvised poetry and encouraged Spicer’s view of poetry as being dictated to the poet. After many years of alcohol abuse, Spicer fell into a prehepatic coma in his apartment building elevator, and later died aged 40 in the poverty ward of San Francisco General Hospital on August 17, 1965. Legacy Spicer’s view of the role of language in the process of writing poetry was probably the result of his knowledge of modern pre-Chomskyan linguistics and his experience as a research-linguist at Berkeley. In the legendary Vancouver lectures he elucidated his ideas on “transmissions” (dictations) from the Outside, using the comparison of the poet as crystal-set or radio receiving transmissions from outer space, or Martian transmissions. Although seemingly far-fetched, his view of language as “furniture”, through which the transmissions negotiate their way, is grounded in the structuralist linguistics of Zellig Harris and Charles Hockett. (In fact, the poems of his final book, Language, refer to linguistic concepts such as morphemes and graphemes). As such, Spicer is acknowledged as a precursor and early inspiration for the Language poets. However, many working poets today list Spicer in their succession of precedent figures. Spicer died as a result of his alcoholism. Since the posthumous publication of The Collected Books of Jack Spicer (first published in 1975), his popularity and influence has steadily risen, affecting poetry throughout the United States, Canada, and Europe. In 1994, The Tower of Babel: Jack Spicer’s Detective Novel was published. Adding to the Jack Spicer revival was the publication in 1998 of two volumes: The House That Jack Built: The Collected Lectures of Jack Spicer, edited by Peter Gizzi; and a biography: Jack Spicer and the San Francisco Renaissance by Lewis Ellingham and Kevin Killian (Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press, 1998). A collected works entitled My Vocabulary Did This to Me: The Collected Poetry of Jack Spicer (Peter Gizzi and Kevin Killian, editors) was published by Wesleyan University Press in November 2008, and won the American Book Award in 2009. A collection of critical essays entitled After Spicer: Critical Essays (John Emil Vincent, editor) was published by Wesleyan University Press in 2011. Further reading Blaser, Robin, editor. The Collected Books of Jack Spicer. Santa Rosa, Calif.: Black Sparrow Press, 1975 A Book Of Correspondences For Jack Spicer. Edited By David Levi Strauss and Benjamin Hollander. San Francisco: A Journal of Acts (#6), 1987; (Note: this is a collection of essays, poetry, and documents celebrating Spicer) Diaman, N. A.. Following My Heart: A Memoir. San Francisco: Persona Press, May 2007 _____. The City: A Novel. San Francisco: Persona Press, August 2007 _____. Sitting With Jack At The Poets Table. Los Angeles: The Advocate, 1984 _____. Second Crossing: A Novel. San Francisco: Persona Press, 1982 Ellingham, Lewis, and Kevin Killian. Poet, Be Like God: Jack Spicer and the San Francisco Renaissance. Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 1998 Foster, Edward Halsey. Jack Spicer. Boise, Idaho: Boise State University, 1991 Gizzi, Peter, editor. The House that Jack Built: The Collected Lectures of Jack Spicer. Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press, 1998 Spicer, Jack. Jack Spicer’s Beowulf, Part 1, edited by David Hadbawnik & Sean Reynolds, introduction by David Hadbawnik, Lost and Found: The CUNY Poetics Documents Initiative, New York, 2011 _____. Jack Spicer’s Beowulf, Part II, edited by David Hadbawnik & Sean Reynolds, afterword by Sean Reynolds, Lost and Found: The CUNY Poetics Documents Initiative, New York, 2011 Tallman, Warren. In the Midst. Vancouver: Talonbooks, 1992 Herndon, James. Everything as Expected San Francisco, 1973 Vincent, John Emil, editor. After Spicer: Critical Essays. Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 2011 References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jack_Spicer

... Me llamo jose alejandro Santana , colombiano nacido en unos de los lugares donde la tierra como gran anfitrión une el rio con el mar llamada ciudad dos veces santa . Donde cada calle , o espacio es mejor que el anterior . donde la canción se hace poesía , en donde un tal vives alegra con su música. Donde el olor amar recorre toda la ciudad y nos lleva de un lugar a otro con la brisa , agitando las ramas de los arboles haciéndonos sonreír a un sol que penetra las profundidades de la sabana de color azul llamada bahía soy medico por profesión. Me gusta todo tipo de música, amante único de los días grises con olor a lluvia . mi lugar preferido la ventana donde en realidad la imaginación cobra vida y todo lo demás se es posible . Estimado(a) lector(a) te doy la bienvenida al mundo de cuentos cortos , poesía frágil y sencilla , y escritos con gran sentido de inspiración.

Arthur William Symons (28 February 1865– 22 January 1945), was a British poet, critic and magazine editor. Life Born in Milford Haven, Wales, of Cornish parents, Symons was educated privately, spending much of his time in France and Italy. In 1884–1886 he edited four of Bernard Quaritch’s Shakespeare Quarto Facsimiles, and in 1888–1889 seven plays of the “Henry Irving” Shakespeare. He became a member of the staff of the Athenaeum in 1891, and of the Saturday Review in 1894, but his major editorial feat was his work with the short-lived Savoy. His first volume of verse, Days and Nights (1889), consisted of dramatic monologues. His later verse is influenced by a close study of modern French writers, of Charles Baudelaire, and especially of Paul Verlaine. He reflects French tendencies both in the subject-matter and style of his poems, in their eroticism and their vividness of description. Symons contributed poems and essays to The Yellow Book, including an important piece which was later expanded into The Symbolist Movement in Literature, which would have a major influence on William Butler Yeats and T. S. Eliot. From late 1895 through 1896 he edited, along with Aubrey Beardsley and Leonard Smithers, The Savoy, a literary magazine which published both art and literature. Noteworthy contributors included Yeats, George Bernard Shaw, and Joseph Conrad. Symons was also a member of the Rhymer’s Club founded by Yeats in 1890. In 1892, The Minister’s Call, Symons’s first play, was produced by the Independent Theatre Society– a private club– to avoid censorship by the Lord Chamberlain’s Office. In 1902 Symons made a selection from his earlier verse, published as Poems. He translated from the Italian of Gabriele D’Annunzio The Dead City (1900) and The Child of Pleasure (1898), and from the French of Émile Verhaeren The Dawn (1898). To The Poems of Ernest Dowson (1905) he prefixed an essay on the deceased poet, who was a kind of English Verlaine and had many attractions for Symons. In 1909 Symons suffered a psychotic breakdown, and published very little new work for a period of more than twenty years. His Confessions: A Study in Pathology (1930) has a moving description of his breakdown and treatment. Verse Days and Nights (1889) Silhouettes (1892) London Nights (1895) Amoris victima (1897) Images of Good and Evil (1899) Poems in 2 volumes.(Contains: The Loom of Dreams in the second Volume, 1901), (1902) Lyrics (1903) An anthology of poetry published in the USA only. A Book of Twenty Songs (1905) The Fool of the World and other Poems (1906) Knave of Hearts (1913). Poems written between 1894 and 1908. Love’s Cruelty (1923) Jezebel Mort, and other poems (1931) Essays An Introduction to the study of Browning (1886) Studies in Two Literatures (1897) Aubrey Beardsley: An Essay with a Preface (1898) The Symbolist Movement in Literature (1899; 1919) Cities (1903), word-pictures of Rome, Venice, Naples, Seville, etc. Plays, Acting and Music (1903) Studies in Prose and Verse (1904) Studies in Seven Arts (1906). Figures of Several Centuries (1916) Cities and Sea-Coasts and Islands (1918) Studies in the Elizabethan Drama (1919) Charles Baudelaire: A Study (1920) Dramatis Personae (1925 - US edition 1923) From Toulouse-Lautrec to Rodin (1929) Studies in Strange Souls (1929) Confessions: A Study in Pathology (1930). A book containing Symons’s description of his breakdown and treatment. Wanderings (1931) A Study of Walter Pater (1932) Fiction Spiritual Adventures (1905). With an autobiographical sketch. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arthur_Symons

James Stephens (9 February 1880– 26 December 1950) was an Irish novelist and poet. He produced many retellings of Irish myths and fairy tales. His retellings are marked by a rare combination of humour and lyricism (Deirdre, and Irish Fairy Tales are often especially praised). He also wrote several original novels (The Crock of Gold, Etched in Moonlight, Demi-Gods) based loosely on Irish fairy tales. The Crock of Gold in particular has achieved enduring popularity and has often been reprinted.