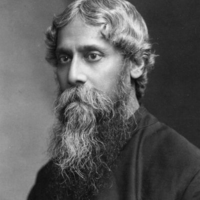

Rabindranath Tagoreα (7 May 1861 – 7 August 1941) was an Indian Bengali polymath who reshaped his region’s literature and music. Author of Gitanjali and its “profoundly sensitive, fresh and beautiful verse”, he became the first non-European to win the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1913. In translation his poetry was viewed as spiritual and mercurial; his seemingly mesmeric personality, flowing hair, and other-worldly dress earned him a prophet-like reputation in the West. His “elegant prose and magical poetry” remain largely unknown outside Bengal.

A veces es difícil morir, más cuando aún estás vivo. Rendirse no es opción y seguir adelante es mandatorio. Aveces necesitamos rupturas y olvidar que hubo historia... A veces es difícil vivir, más cuando el tiempo quiere verte morir, Pero todos necesitamos destrucción, para alcanzar un renacer en gloria. La vida no tiene manual o instrucciones sigue, sin arrepentirte y aprende día con día sus lecciones!

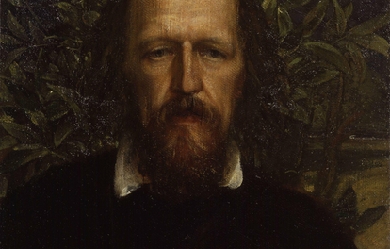

Alfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson, FRS (6 August 1809 – 6 October 1892) was Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom during much of Queen Victoria's reign and remains one of the most popular poets in the English language. A number of phrases from Tennyson’s work have become commonplaces of the English language, including “Nature, red in tooth and claw”, “'Tis better to have loved and lost / Than never to have loved at all”, “Theirs not to reason why, / Theirs but to do and die”, “My strength is as the strength of ten, / Because my heart is pure”, “Knowledge comes, but Wisdom lingers”, and “The old order changeth, yielding place to new”. He is the ninth most frequently quoted writer in The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations.

Sara Teasdale (August 8, 1884 – January 29, 1933) was an American lyric poet. She was born Sarah Trevor Teasdale in St. Louis, Missouri, and used the name Sara Teasdale Filsinger after her marriage in 1914. She had such poor health for so much of her childhood, home schooled until age 9, that it was only at age 10 that she was well enough to begin school. She started at Mary Institute in 1898, but switched to Hosmer Hall in 1899, graduating in 1903. I Shall Not Care WHEN I am dead and over me bright April Shakes out her rain-drenched hair, Tho' you should lean above me broken-hearted, I shall not care. I shall have peace, as leafy trees are peaceful When rain bends down the bough, And I shall be more silent and cold-hearted Than you are now.

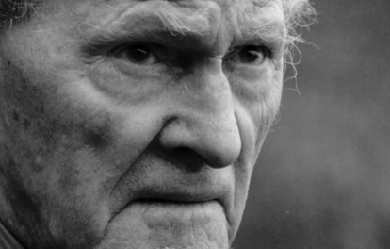

Ronald Stuart Thomas (29 March 1913 – 25 September 2000), published as R. S. Thomas, was a Welsh poet and Anglican priest who was noted for his nationalism, spirituality and deep dislike of the anglicisation of Wales. In 1955, John Betjeman, in his introduction to the first collection of Thomas’s poetry to be produced by a major publisher, Song at the Year's Turning, predicted that Thomas would be remembered long after Betjeman himself was forgotten. M. Wynn Thomas said: "He was the Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn of Wales because he was such a troubler of the Welsh conscience. He was one of the major English language and European poets of the 20th century." R. S. Thomas was born in Cardiff, the only child of Thomas Hubert and Margaret (née Davis). The family moved to Holyhead in 1918 because of his father's work in the merchant navy. He was awarded a bursary in 1932 to study at Bangor University, where he read Classics. In 1936, having completed his theological training at St. Michael's College, Llandaff, he was ordained as a priest in the Church in Wales. From 1936 to 1940 he was the curate of Chirk, Denbighshire, where he met his future wife, Mildred (Elsi) Eldridge, an English artist. He subsequently became curate at Tallarn Green, Flintshire. Thomas and Mildred were married in 1940 and remained together until her death in 1991. Their son, Gwydion, was born 29 August 1945. The Thomas family lived on a tiny income and lacked the comforts of modern life, largely by the Thomas's choice. One of the few household amenities the family ever owned, a vacuum cleaner, was rejected because Thomas decided it was too noisy. For twelve years, from 1942 to 1954, Thomas was rector at Manafon, near Welshpool in rural Montgomeryshire. It was during his time at Manafon that he first began to study Welsh and that he published his first three volumes of poetry, The Stones of the Field, An Acre of Land and The Minister. Thomas' poetry achieved a breakthrough with the publication of his fourth book Song at the Year's Turning, in effect a collected edition of his first three volumes, which was critically very well received and opened with Betjeman's famous introduction. His position was also helped by winning the Royal Society of Literature's Heinemann Award. Thomas learnt the Welsh language at age 30, too late in life, he said, to be able to write poetry in it. The 1960s saw him working in a predominantly Welsh speaking community and he later wrote two prose works in Welsh, Neb (English: Nobody), an ironic and revealing autobiography written in the third person, and Blwyddyn yn Llŷn (English: A Year in Llŷn). In 1964 he won the Queen's Gold Medal for Poetry. From 1967 to 1978 he was vicar at St Hywyn's Church (built 1137) in Aberdaron at the western tip of the Llŷn Peninsula. Thomas retired from church ministry in 1978 and he and his wife relocated to Y Rhiw, in "a tiny, unheated cottage in one of the most beautiful parts of Wales, where, however, the temperature sometimes dipped below freezing", according to Theodore Dalrymple. Free from the constraints of the church he was able to become more political and active in the campaigns that were important to him. He became a fierce advocate of Welsh nationalism, although he never supported Plaid Cymru because he believed they did not go far enough in their opposition to England. In 1996 Thomas was nominated for the Nobel Prize for Literature (the winner that year was Seamus Heaney). Thomas died on 25 September 2000, aged 87, at his home at Pentrefelin near Criccieth. He had been ill with heart trouble and had been treated at Gwynnedd hospital until two weeks before he died. After his death an event celebrating his life and poetry was held in Westminster Abbey with readings from Heaney, Andrew Motion, Gillian Clarke and John Burnside. Thomas's ashes are buried close to the door of St. John's Church, Porthmadog, Gwynedd. Beliefs Thomas believed in what he called "the true Wales of my imagination", a Welsh-speaking, aboriginal community that was in tune with the natural world. He viewed western (specifically English) materialism and greed, represented in the poetry by his mythical "Machine", as the destroyers of community. He could tolerate neither the English who bought up Wales and, in his view, stripped it of its wild and essential nature, nor the Welsh whom he saw as all too eager to kowtow to English money and influence. This may help explain why Thomas was an ardent supporter of CND and described himself as a pacifist but also why he supported the Meibion Glyndŵr fire-bombings of English-owned holiday cottages in rural Wales. On this subject he said in 1998, "what is one death against the death of the whole Welsh nation?" He was also active in wildlife preservation and worked with the RSPB and Welsh volunteer organisations for the preservation of the Red Kite. He resigned his RSPB membership over their plans to introduce non-native kites to Wales. Thomas's son, Gwydion, a resident of Thailand, recalls his father's sermons, in which he would "drone on" to absurd lengths about the evil of refrigerators, washing machines, televisions and other modern devices. Thomas preached that they were all part of the temptation of scrambling after gadgets rather than attending to more spiritual needs. "It was the Machine, you see", Gwydion Thomas explained to a biographer. "This to a congregation that didn’t have any of these things and were longing for them." Although he may have taken some ideas to extreme lengths, Theodore Dalrymple wrote, Thomas "was raising a deep and unanswered question: What is life for? Is it simply to consume more and more, and divert ourselves with ever more elaborate entertainments and gadgetry? What will this do to our souls?" Although he was a cleric, he was not always charitable and was known for being awkward and taciturn. Some critics have interpreted photographs of him as indicating he was "formidable, bad-tempered, and apparently humorless." Works Almost all of Thomas's work concerns the Welsh landscape and the Welsh people, themes with both political and spiritual subtext. His views on the position of the Welsh people, as a conquered people are never far below the surface. As a cleric, his religious views are also present in his works. His earlier works focus on the personal stories of his parishioners, the farm labourers and working men and their wives, challenging the cosy view of the traditional pastoral poem with harsh and vivid descriptions of rural lives. The beauty of the landscape, although ever-present, is never suggested as a compensation for the low pay or monotonous conditions of farm work. This direct view of "country life" comes as a challenge to many English writers writing on similar subjects and challenging the more pastoral works of such as contemporary poets as Dylan Thomas. Thomas's later works were of a more metaphysical nature, more experimental in their style and focusing more overtly on his spirituality. Laboratories of the Spirit (1975) gives, in its title, a hint at this development and also reveals Thomas's increasing experiments with scientific metaphor. He described this shift as an investigation into the "adult geometry of the mind".} Fearing that poetry was becoming a dying art, inaccessible to those who most needed it, "he attempted to make spiritually minded poems relevant within, and relevant to, a science-minded, post-industrial world", to represent that world both in form and in content even as he rejected its machinations. Despite his nationalism Thomas could be hard on his fellow countrymen. Often his works read as more of a criticism of Welshness than a celebration. He himself said there is a "lack of love for human beings" in his poetry. Other critics have not been so harsh. Al Alvarez said: "He was wonderful, very pure, very bitter but the bitterness was beautifully and very sparely rendered. He was completely authoritative, a very, very fine poet, completely off on his own, out of the loop but a real individual. It's not about being a major or minor poet. It's about getting a work absolutely right by your own standards and he did that wonderfully well." Thomas's final works commonly sold 20,000 copies in Britain alone. Books * The Stones of the Field (1946) * An Acre of Land (1952) * The Minister (1953) * Song at the Year's Turning (1955) * Poetry for Supper (1958) * Tares, [Corn-weed] (1961) * The Bread of Truth (1963) * Words and the Poet (1964, lecture) * Pietà (1966) * Not That He Brought Flowers (1968) * H'm (1972) * What is a Welshman? (1974) * Laboratories of the Spirit (1975) * Abercuawg (1976, lecture) * The Way of It (1977) * Frequencies (1978) * Between Here and Now (1981) * Ingrowing Thoughts (1985) * Neb (1985) in Welsh, autobiography, written in the third person * Experimenting with an Amen (1986) * Welsh Airs (1987) * The Echoes Return Slow (1988) * Counterpoint (1990) * Blwyddyn yn Llŷn (1990) in Welsh * Pe Medrwn Yr Iaith : ac ysgrifau eraill ed. Tony Brown & Bedwyr L. Jones, essays in Welsh (1990) * Mass for Hard Times (1992) * No Truce with the Furies (1995) * Autobiographies (1997, collection of prose writings) * Residues (2002, posthumously) References Wikipedia - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/R._S._Thomas

Dylan Marlais Thomas (27 October 1914 – 9 November 1953) was a Welsh poet and writer who wrote exclusively in English. In addition to poetry, he wrote short stories and scripts for film and radio, which he often performed himself. His public readings, particularly in America, won him great acclaim; his sonorous voice with a subtle Welsh lilt became almost as famous as his works. His best-known works include the “play for voices” Under Milk Wood and the celebrated villanelle for his dying father, “Do not go gentle into that good night”. Appreciative critics have also noted the craftsmanship and compression of poems such as “In my Craft or Sullen Art”, and the rhapsodic lyricism in “And death shall have no dominion” and “Fern Hill”.

Lo que normalmente escribo en las llamadas fichas de autor: periodista e investigadora. Mis libros más recientes son "Adriana Loredo: Páginas muy bien condimentadas" (compilación de textos de la periodista Rosa Hilda Zell) y los ensayos "Arreglamundos: mujeres y periodismo en Cuba" y "Modernidad y periodismo en Julián del Casal". He devenido editora gracias al sitio web El Camagüey (www.elcamagüey.org). Lo que de mí no digo (y tal vez más importante) está en las historias que aquí podrás leer...

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835– April 21, 1910), better known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, entrepreneur, publisher, and lecturer. Among his novels are The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) and its sequel, the Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1885), the latter often called “The Great American Novel”.

Celia Laighton Thaxter (June 29, 1835 – August 25, 1894) was an American writer of poetry and stories. She was born in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Thaxter grew up in the Isles of Shoals, first on White Island, where her father, Thomas Laighton, was a lighthouse keeper, and then on Smuttynose and Appledore Islands. When she was sixteen, she married Levi Thaxter and moved to the mainland, residing first in Watertown, Massachusetts at a property his father owned. Celia died suddenly while on Appledore Island. She was buried not far from her cottage, which unfortunately burned in the 1914 fire that destroyed The Appledore House hotel.

Dear my followers...I'm going to be taking this page down shortly. I'm sorry but I can't keep up with it and to help ease some of the stress I have I can't keep it up. Thank you for everything though. Feel free to email me and keep writing, remember you all are beautiful and talented. Don't let this world get you down. Farewell my friends, For the last, XoxoTay.

Jaime Torres Bodet (México, D.F.; 17 de abril de 1902 – Ibídem, 13 de mayo de 1974) fue un diplomático, escritor, ensayista y poeta mexicano, director general de la Unesco de 1948 a 1952. Su trabajo en la alfabetización ha sido reconocido, además de haber implementado la política de relaciones exteriores durante los inicios de la Guerra Fría. Se suicidó en 1974 Secretario de Educación Pública Secretario de Educación Pública. Reorganizó y dio nuevo impulso a la campaña alfabetizadora, creó el Instituto de Capacitación del Magisterio, organizó la Comisión Revisora de Planes y Programas, inició la Biblioteca Enciclopédica Popular, dirigió el valioso compendio México y la cultura (1946), construyó numerosas escuelas y, señaladamente, la Escuela Normal para Maestros, la Escuela Normal Superior y el Conservatorio Nacional en la Ciudad de México, y dio, en fin, coherencia doctrinaria a la educación mexicana. De 1958 a 1964 ocupó por segunda vez el cargo de Secretario de Educación Pública , periodo en que inició un Plan de Once Años para resolver el problema de la educación primaria en el país, en el cual trabajó estrechamente con la distinguida economista Ifigenia Martínez, fundó la Comisión Nacional de Libros de Texto Gratuitos y promovió la construcción del Museo Nacional de Antropología, del Museo de Arte Moderno y la organización y adaptación de los de Arte Virreinal y de Pintura Colonial. También dio auge al programa nacional de construcción de escuelas. Diplomático La siguiente etapa de su vida, a partir de 1929, estuvo dedicada al servicio exterior mexicano. Ese año aprobó el examen de oposición para ingresar a la carrera diplomática. Estuvo designado sucesivamente en Madrid, París, La Haya, Buenos Aires y Bruselas, donde lo sorprende, en 1940, la invasión nazi a Bélgica. Cabe destacar que entre 1937 y 1938 fue jefe del Departamento Diplomático de la Cancillería. A su regreso en México, de 1940 a 1943 es subsecretario de Relaciones Exteriores. Fue secretario de Relaciones Exteriores durante la gestión del presidente Miguel Alemán Valdés, de 1946 a 1948. En noviembre de 1948 fue designado Director General de la Unesco, cargo que ocupó hasta 1952. De 1954 a 1958 fue embajador de México en Francia. Escritor, ensayista y poeta Torres Bodet ingresó en la Academia Mexicana de la Lengua como nombrado miembro de número en 1952 y tomó posesión de la silla XXI el 12 de junio de 1953.2 Fue miembro de El Colegio Nacional, al cual ingresó el 6 de julio de 1953.3 En 1963, fue nombrado doctor honoris causa por la Universidad Autónoma de Sinaloa.4 En 1966 recibió el Premio Nacional de Ciencias y Artes en el área de Literatura y Lingüística de México.5 En 1971 recibió la Medalla Belisario Domínguez del Senado de la República y muchos otros honores de instituciones nacionales y extranjeras. Las novelas y relatos de Torres Bodet -siete volúmenes publicados entre 1927 y 1941- pertenecen a la época de interés por las nuevas direcciones de la prosa narrativa francesa y españolas. Desde la perspectiva actual, son obras sobre todo representativas de la búsqueda de una nueva sensibilidad y un nuevo estilo novelesco que se realizaba por aquellos años. Junto con varios intelectuales formó parte del grupo Los contemporáneos. En sus ensayos y estudios de crítica literaria —publicados inicialmente y en su mayoría en la revista que dio nombre al grupo, y reunidos luego algunos de ellos en un solo volumen (1928)— unía Torres Bodet un conocimiento pleno y siempre renovado de letras antiguas y modernas a un espíritu alerta y a un estilo dúctil y de transparente riqueza. Su crítica rectificó, en su tiempo, el valor de algunos falsos brillos y contribuyó singularmente a la formación literaria de las nuevas generaciones. Sus escritos relacionados con sus cargos públicos: discursos y mensajes entre los que se encuentran páginas admirables—como la oración a la madre, el discurso académico sobre la responsabilidad del escritor y el pronunciado en la inauguración del nuevo Museo Nacional de Antropología—, están dedicados a elucidar los problemas de la cultura, la educación y la concordia internacional de México y el mundo. Padeció cáncer durante dieciséis años. Víctima de dolor, se suicidó en la sala de su casa con un disparo en la sien el 13 de mayo de 1974. Se le rindió un homenaje de cuerpo presente en el Palacio de Bellas Artes. Fue sepultado en la Rotonda de las Personas Ilustres de la Ciudad de México. * Fervor (1918) * El corazón delirante (1922) * Canciones (1922) * La casa (1923) * Los días (1923) * Nuevas Canciones (1923) * Poemas (1924) * Biombo (1925) * Poesías (1926) * Contemporáneos (1928) * Destierro (1930) * Estrella de día (1933) * Cripta (1937) * Sonetos (1949) * Fronteras (1954) * Sin tregua (1957) * Tiempo de arena (1955) * Balzac (1959) * Tolstoi (1965) * Rubén Darío (1966), Premio Mazatlán de Literatura 1968 * Proust (1967) * Memorias (cinco volúmenes) (1961) Artículos publicados: * «Muerte de Proserpina», en Revista de Occidente, 1930. Referencias Wikipedia - http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jaime_Torres_Bodet

Luis Llorens Torres (14 de mayo de 1876, Juana Díaz - 16 de junio de 1944, Santurce) fue un poeta y periodista puertorriqueño. Trayectoria Realizó sus estudios primarios en Juana Díaz, aprendiendo letras, escritura y aritmética. A los 12 años comenzó a estudiar en Maricao su segunda enseñanza obteniendo el bachillerato en literatura y ciencia. Al finalizarlo su familia le ofreció la oportunidad de tener una educación superior en España. Reflejaría los sentimientos de esta separación en su poema "Valle de Collores". Se matriculó en la Facultad de Leyes de Barcelona, estudiando allí tres años. Posteriormente se recibió de abogado en la Universidad de Granada, doctorándose en Filosofía y Letras. En 1898 publicó su primer libro, "América", y al siguiente el primero de versos, "Al pie de la Alhambra", dedicado a la granadina Carmen Rivero, por entonces su novia, con quien contraería nupcias el 23 de enero de 1901, regresando posteriormente a Puerto Rico. Allí se había producido el cambio de soberanía. Ingresó al Partido Federal que defendía la independencia de la isla, lo que reflejó en su poema "El patito feo". Ocupa un escaño legislativo en la Cámara de Delegados para 1908 - 1910. Como colaboró en los periódicos publicados en Puerto Rico en asuntos históricos y políticos. Fundó la "Revista de las Antillas", considerada como una de las mejores en su género. Fue uno de los fundadores y redactores de Juan Bobo, semanario de crítica independiente en el que utilizó y promulgo su pseudónimo "Luis de Puerto Rico". Referencias Wikipedia-http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luis_Llorens_Torres

Torquato Tasso (Sorrento, 11 marzo 1544 – Roma, 25 aprile 1595) è stato un poeta, scrittore, drammaturgo e filosofo italiano. La sua opera più importante, conosciuta e tradotta in molte lingue è la Gerusalemme liberata (1581), in cui vengono cantati gli scontri tra cristiani e musulmani durante la prima crociata, culminanti nella presa cristiana di Gerusalemme.

James Thomson (c. 11 September 1700– 27 August 1748) was a Scottish poet and playwright, known for his masterpiece The Seasons and the lyrics of “Rule, Britannia!”. Scotland, 1700–1725 James Thomson was born in Ednam in Roxburghshire around 11 September 1700 and baptised on 15 September. He was the fourth of nine children of Thomas Thomson and Beatrix Thomson (née Trotter). Beatrix Thomson was born in Fogo, Berwickshire and was a distant relation of the house of Hume. Thomas Thomson was the Presbyterian minister of Ednam until eight weeks after Thomson’s birth, when he was admitted as minister of Southdean, where Thomson spent most of his early years. Thomson may have attended the parish school of Southdean before going to the grammar school in Jedburgh in 1712. He failed to distinguish himself there. Shiels, his earliest biographer, writes: 'far from appearing to possess a sprightly genius, [Thomson] was considered by his schoolmaster, and those which directed his education, as being really without a common share of parts’. He was, however, encouraged to write poetry by Robert Riccaltoun (1691–1769), a farmer, poet and Presbyterian minister; and Sir William Bennet (d. 1729), a whig laird who was a patron of Allan Ramsay. While some early poems by Thomson survive, he burned most of them on New Year’s Day each year. Thomson entered the College of Edinburgh in autumn 1715, destined for the Presbyterian ministry. At Edinburgh he studied metaphysics, Logic, Ethics, Greek, Latin and Natural Philosophy. He completed his arts course in 1719 but chose not to graduate, instead entering Divinity Hall to become a minister. In 1716 Thomas Thomson died, with local legend saying that he was killed whilst performing an exorcism. At Edinburgh Thomson became a member of the Grotesque Club, a literary group, and he met his lifelong friend David Mallet. After the successful publication of some of his poems in the ‘’Edinburgh Miscellany’’ Thomson followed Mallet to London in February 1725 in an effort to publish his verse. London, 1725–1727 In London, Thomson became a tutor to the son of Charles Hamilton, Lord Binning, through connections on his mother’s side of the family. Through David Mallet, by 1724 a published poet, Thomson met the great English poets of the day including Richard Savage, Aaron Hill and Alexander Pope. Thomson’s mother died on 12 May 1725, around the time of his writing ‘Winter’, the first poem of ‘‘The Seasons’’. ‘Winter’ was first published in 1726 by John Millian, with a second edition being released (with revisions, additions and a preface) later the same year. By 1727, Thomson was working on Summer, published in February, and was working at Watt’s Academy, a school for young gentlemen and a bastion of Newtonian science. In the same year Millian published a poem by Thomson titled ‘A Poem to the Memory of Sir Isaac Newton’ (who had died in March). Leaving Watt’s academy, Thomson hoped to earn a living through his poetry, helped by his acquiring several wealthy patrons including Thomas Rundle, the countess of Hertford and Charles Talbot, 1st Baron Talbot. Later life, 1728–1748 He wrote Spring in 1728 and finally Autumn in 1730, when the set of four was published together as The Seasons. During this period he also wrote other poems, such as to the Memory of Sir Isaac Newton, and his first play, The Tragedy of Sophonisba (1729). The latter is best known today for its mention in Samuel Johnson’s Lives of the English Poets, where Johnson records that one 'feeble’ line of the poem - “O, Sophonisba, Sophonisba, O!” was parodied by the wags of the theatre as, “O, Jemmy Thomson, Jemmy Thomson, O!”. In 1730, he became tutor to the son of Sir Charles Talbot, then Solicitor-General, and spent nearly two years in the company of the young man on a tour of Europe. On his return Talbot arranged for him to become a secretary in chancery, which gave him financial security until Talbot’s death in 1737. Meanwhile, there appeared his next major work, Liberty (1734). In 1740, he collaborated with Mallet on the masque Alfred which was first performed at Cliveden, the country home of Frederick, Prince of Wales. Thomson’s words for “Rule Britannia”, written as part of that masque and set to music by Thomas Arne, became one of the best-known British patriotic songs - quite apart from the masque which is now virtually forgotten. The Prince gave him a pension of £100 per annum. He had also introduced him to George Lyttelton, who became his friend and patron. In later years, Thomson lived in Richmond upon Thames, and it was there that he wrote his final work The Castle of Indolence, which was published just before his untimely death on 27 August 1748. Johnson writes about Thomson’s death, “by taking cold on the water between London and Kew, he caught a disorder, which, with some careless exasperation, ended in a fever that put end to his life”. He is buried in St. Mary Magdalene church in Richmond. A dispute over the publishing rights to one of his works, The Seasons, gave rise to two important legal decisions (Millar v. Taylor; Donaldson v. Beckett) in the history of copyright. Thomson’s The Seasons was translated into German by Barthold Heinrich Brockes (1745). This translation formed the basis for a work with the same title by Gottfried van Swieten, which became the libretto for Haydn’s oratorio The Seasons. Memorials Thomson is one of the sixteen Scottish poets and writers appearing on the Scott Monument on Princes Street in Edinburgh. He appears on the right side of the east face. Editions Thomson, James & Bloomfield, Robert, The Seasons & Castles of Indolence / The Farmer’s Boy, Rural Tales, Banks of the Wye, &c. &c., (London: Scott, Webster & Geary, 1842). Gilfillan, Rev. George, Thomson’s Poetical Works, with Life, Critical Dissertation, and Explanatory Notes, Library Edition of the British Poets (1854). Thomson, James. The Seasons, by... A New Edition. Adorned with A Set of Engravings, from Original Paintings. Together with an Original Life of the Author, and a Critical Essay on the Seasons. by Robert Heron, (Perth: R. Morison, 1793) Thomson, James. Poems, edited by William Bayne, London: Walter Scott Publishing Co., [1900], (Series: The Canterbury poets). Thomson, James. The Seasons, edited with introduction and commentary by James Sambrook, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1981) ISBN 0-19-812713-8. Thomson, James. Liberty, The Castle of Indolence and other poems, edited with introduction and commentary by James Sambrook, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1986) ISBN 0-19-812759-6. Bayne, William, Life of James Thomson, Edinburgh: Oliphant, Anderson and Ferrier, 1898, ("Famous Scots Series"). References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Thomson_(poet,_born_1700)

I have never truly fit in with my peers. In early grade school, I had a good amount of friends my age, but by the third grade I was reading at least five grade levels above them, and had discovered my love of the written word. I immersed myself in literature as my peers immersed themselves in pop culture. My friends grew closer to each other, as I delved into my own world. A world of fiction and fantasy. As the girls fell in love with the boys, I fell in love with my favorite characters. My vocabulary expanded to the point where large, polysyllabic words were part of my normal speech, and I had to repeat and tailor my sentences to speak to my peers. This trouble communicating pushed me further from my friends and closer to my books. I chose to live my life between the pages. It was only a matter of time, I suppose, before I discovered what reading had given me. I had developed a command over the written word which I could use to create my own stories. I could share my own thoughts efficiently and creatively, and I could make it sound beautiful with the ways I could craft the syllables to my whims. Words became better friends to me than humans. Over time I have discovered myself as a writer and poet. However, I have not lost my interpersonal relationships. I have been in love, I have been hurt, I have learned to interact with my peers, and I have had the experience one receives in high school. I have taken my experiences, both real and read about, and told them with words. I have learned from life and literature, and developed a depth of maturity that separates me from my closest friends. They come to me for advice because I have an understanding of issues that has proved helpful to them, in the rare situation that they actually enact it. However, when it comes down to it, the superficiality of my fellow high school girls pushes me away. I have tried and failed to open up to my peers and have effectively, though rather unfortunately, created a vast distance between them and I. Now here I am, unable to connect with my peers on a satisfactory level, and I feel a deep loneliness despite however many people surround me at any time. I have, to my dismay, dug my own hole, -- the nature of this hole I am still unsure of, could it be my own grave, I don't know -- but I have opened up a bottle of hurt and placed myself in a crippling depression. My own ignorance has been my ruin. I put myself on a plain above my level, and when I finally came down, I came crashing down only to find that I had pushed myself too far away. I have friends whose sincerity I am irrevocably unconvinced, and I have my own thoughts. Thoughts full of pain and resentment. I used to, desperately, blame others for it, too. I blamed my peers for not being on my level, and even my doctors for treating the ADD which could have kept me back from becoming too knowledgable. However, now I see that I am alone because I put myself in solitary. It is as regrettable as the physical scars which I have made on my wrist and gut: the emotional scar I have carved in my own heart. PS: I have a bit of an affinity to Willow Trees...

William Makepeace Thackeray (18 July 1811– 24 December 1863) was an English novelist of the 19th century. He is famous for his satirical works, particularly Vanity Fair, a panoramic portrait of English society. He began as a satirist and parodist, writing works that displayed a sneaking fondness for roguish upstarts such as Becky Sharp in Vanity Fair, and the title characters of The Luck of Barry Lyndon and Catherine. In his earliest works, written under such pseudonyms as Charles James Yellowplush, Michael Angelo Titmarsh and George Savage Fitz-Boodle, he tended towards savagery in his attacks on high society, military prowess, the institution of marriage and hypocrisy.

Francis Thompson (16 December 1859– 13 November 1907) was an English poet and ascetic. After attending college, he moved to London to become a writer, but could only find menial work and became addicted to opium, and was a street vagrant for years. A married couple read his poetry and rescued him, publishing his first book Poems in 1893. Thompson lived as an unbalanced invalid in Wales and at Storrington, but wrote three books of poetry, with other works and essays, before dying of tuberculosis in 1907. Life and work Thompson was born in Winckley Street, Preston, Lancashire. His father, Charles, was a doctor who had converted to Roman Catholicism, following his brother Edward Healy Thompson, a friend of Cardinal Manning. Thompson was educated at Ushaw College, near Durham, and then studied medicine at Owens College, now the University of Manchester. He took no real interest in his studies and never practised as a doctor, moving instead to London in 1885, to try to become a writer. Here he was reduced to selling matches and newspapers for a living. During this time, he became addicted to opium, which he first had taken as medicine for ill health. Thompson started living on the streets of Charing Cross and sleeping by the River Thames, with the homeless and other addicts. He was turned down by Oxford University, not because he was unqualified, but because of his drug addiction. Thompson attempted suicide in his nadir of despair, but was saved from completing the action through a vision which he believed to be that of a youthful poet Thomas Chatterton, who had committed suicide almost a century earlier. A prostitute– whose identity Thompson never revealed– befriended him, gave him lodgings and shared her income with him. Thompson was later to describe her in his poetry as his saviour. She soon disappeared, however, never to return, in his estimation because she feared she would taint his growing reputation. In 1888, he had been 'discovered’ after sending his poetry to the magazine Merrie England. He had been sought out by the magazine’s editors, Wilfrid and Alice Meynell. Recognizing the value of his work, the couple gave him a home and arranged for publication of his first book Poems in 1893. The book attracted the attention of sympathetic critics in the St James’s Gazette and other newspapers, and Coventry Patmore wrote a eulogistic notice in the Fortnightly Review of January 1894. Concerned about his opium addiction, which was at its height following his years on the streets, the Meynells sent Thompson to Our Lady of England Priory, Storrington. Thompson subsequently lived as an invalid at Pantasaph, Flintshire in Wales and at Storrington. A lifetime of extreme poverty, ill-health, and an addiction to opium took a heavy toll on Thompson, even though he found success in his last years. He would eventually die from tuberculosis at the age of 47, in the Hospital of St John and St Elizabeth and he is buried in St. Mary’s Roman Catholic Cemetery in Kensal Green. His tomb bears the last line from a poem he wrote for his godson - Look for me in the nurseries of Heaven. Style and influence His most famous poem, The Hound of Heaven, describes the pursuit of the human soul by God. This poem is the source of the phrase “with all deliberate speed,” used by the Supreme Court in Brown II, the remedy phase of the famous decision on school desegregation. A phrase in The Kingdom of God is the source of the title of Han Suyin’s novel Love Is a Many-Splendored Thing. In addition, Thompson wrote the most famous cricket poem, the nostalgic At Lord’s. He also wrote Sister Songs (1895), New Poems (1897), and a posthumously published essay, Shelley (1909). He wrote a treatise On Health and Holiness, dealing with the ascetic life, which was published in 1905. G. K. Chesterton said shortly after his death that “with Francis Thompson we lost the greatest poetic energy since Browning.” Among Thompson’s devotees was the young J. R. R. Tolkien, who purchased a volume of Thompson’s works in 1913-1914, and later said that it was an important influence on his own writing. The American novelist Madeleine L’Engle used a line from the poem The Mistress of Vision as the title of her last Vicki Austin novel, Troubling a Star. In 2011, Thompson’s life was the subject of the stage play and film script HOUND (Visions in the Life of the Poet Francis Thompson) by writer/director Chris Ward, which has been performed in various venues around London. Jack the Ripper suspect In his 1999 book Paradox, Australian author and educator Richard Patterson named Thompson as a possible identity of serial killer Jack the Ripper. On 6 November 2015, Patterson strengthened his claim. Home Thompson’s birthplace, in Winckley Street, Preston is marked by a memorial plaque. The inscription reads: "Francis Thompson poet was born in this house Dec 16 1859. Ever and anon a trumpet sounds, From the hid battlements of eternity." The home in Ashton-under-Lyne where Thompson lived from 1864 to 1885 was also marked with a blue plaque. In 2014, however, the building collapsed. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Thompson

Aprendiz de la vida, con tiempo pero sin prisa, amante de mi esposa, alumno de mi hija. Realicé estudios de filosofía, me gradué como psicólogo. Trabajo con colectivos comunitarios diferenciales en articulación entre escuela pública y sus glocalidades. Amo la cocina y esto me llevó a co-participar con @fundaciónati de un viaje hermoso en la co-formación con matronas en gastronomía cultural como resistencia.

Josefina de la Torre Millares (Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, 1907−Madrid, 12 de julio de 2002) fue una poetisa, novelista, cantante lírica y actriz canaria vinculada a la Generación del 27 y la corriente vanguardista hispánica de la primera mitad del siglo XX. Está en la nómina de Las Sinsombrero. Comenzó a escribir poesía a los nueve años, en 1915, cuando compuso unos versos dedicados al poeta modernista canario Alonso Quesada, aunque un año antes ya había escrito un poema de homenaje a Benito Pérez Galdós, y a los 15 comenzó a publicar en revistas.1 La influencia de su hermano Claudio, novelista y dramaturgo en auge en aquel momento, y Premio Nacional de Literatura en 1926, fue muy importante para su iniciación en el campo de la literatura y también de la representación teatral. Así en 1928, creó en su casa de Las Canteras el llamado Teatro Mínimo que dirigía su hermano Claudio.

Paul-Jean Toulet, né à Pau (Basses-Pyrénées) le 5 juin 1867 et mort à Guéthary (Basses-Pyrénées) le 6 septembre 1920, est un écrivain et poète français, célèbre par ses Contrerimes, une forme poétique qu’il avait créée. Biographie Paul-Jean Toulet perd sa mère à sa naissance. Tandis que son père regagne l’île Maurice, il est confié à un oncle de Bilhères, dans la vallée d’Ossau. Il séjourne trois ans à l’île Maurice (1885-1888) puis un an à Alger (1888-1889), où il publie ses premiers articles. Il arrive à Paris en 1898. C’est là qu’il se forme véritablement, sous la tutelle de Willy, dont il est l’un des nombreux nègres, notamment pour Maugis en ménage. Colocataire du futur Prince des Gastronomes Curnonsky, il fréquente les salons mondains et les boudoirs demi-mondains qu’il évoque dans Mon amie Nane. Il travaille beaucoup et se livre à divers excès, dont l’alcool et l’opium. Il collabore à de nombreuses revues, dont la Revue critique des idées et des livres de Jean Rivain et Eugène Marsan. De novembre 1902 à mai 1903, il effectue un voyage qui le mène jusqu’en Indochine. Il quitte définitivement Paris en 1912 pour s’installer chez sa sœur, à Saint-Loubès, au château de la Rafette où leur tante maternelle vit avec son mari Aristide Chaline qui a racheté le château. Paul-Jean est un familier des lieux qui auront l’honneur de plusieurs Contrerimes. Puis à Guéthary, où il se marie. Ses dernières années sont assombries par la maladie. Pendant ce temps, un groupe de jeunes poètes, dont Francis Carco et Tristan Derème, prenant son œuvre en modèle, s’intitulent « poètes fantaisistes ». Les fameuses Contrerimes parurent à partir de la fin des années 1900 dans des revues et dans le corps des romans de Toulet. Un premier projet de les réunir en volume fut avorté par la guerre de 1914. Le livre ne parut finalement que quelques mois après la mort de l’auteur. Il contient outre des contrerimes des poèmes d’autres formes, dont ce dixain: Dans le domaine théâtral, Paul-Jean Toulet composa avec des amis (Martin et Cotoni) un à-propos en vers: La Servante de Molière dont nous n’avons pas le texte, mais qui fut représenté au Théâtre des Nouveautés d’Alger (alors que le poète y résidait), et qu’il s’amusa à éreinter lui-même dans Le Moniteur. Il fit également représenter une comédie en prose: Madame Josephe Prudhomme dont il était l’unique auteur. Enfin, Le Souper interrompu qui fut joué pour la première fois le 27 mai 1944 au théâtre du Vieux-Colombier, au même programme qu’une autre création, Huis clos de Jean-Paul Sartre. Paul-Jean Toulet avait eu, dès 1902, un projet avec Claude Debussy autour de Comme il vous plaira (As you like it) de William Shakespeare. Debussy était désireux d’y revenir en 1917, mais la maladie du compositeur n’en a pas permis la réalisation. Georges Bernanos évoque son souvenir dans les premiers mots de son premier roman Sous le soleil de Satan (« Voici l’heure du soir, qu’aima P.J Toulet... »). De manière un peu inattendue, Frédéric Beigbeder place deux œuvres de Paul-Jean Toulet (Mon amie Nane et Les Contrerimes) dans le "top-100" de ses livres préférés que constitue Premier bilan après l’Apocalypse. Le groupe français Alcest a repris le texte de son poème Sur l’océan couleur de fer sur le titre homonyme paru sur l’album Écailles de Lune (2010). Œuvres * Publications posthumes * TraductionLe Grand Dieu Pan, d’Arthur Machen (parution française, 1901)Correspondance * Publications en revues * Rééditions modernes Les références Wikipedia – https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul-Jean_Toulet