José María Alonso y Trelles Jarén, conocido como «El Viejo Pancho», (Ribadeo Lugo, 7 de mayo de 1857 – Montevideo, 28 de julio de 1924) fue un escritor y poeta gauchesco uruguayo de origen gallego. Radicado en su juventud en la localidad uruguaya de Tala, tuvo a su cargo las publicaciones satíricas El Tala Cómico y Momentáneas. Sus aportes literarios más importantes se dieron en el campo de la lírica, que cultivó en la forma de poesía gauchesca y a la que contribuyó ampliamente a través de los semanarios tradicionalistas El terruño, El fogón y El ombú. En 1915 publicó su obra maestra llamada Paja brava en la cual recopiló la mayoría de sus textos del mencionado género. Hacia el final de sus días ocupó una banca como diputado por el departamento de Canelones. Primeros años Alonso y Trelles nació en Santa María do Campo, parroquia correspondiente al núcleo urbano del municipio de Ribadeo en Galicia. Hijo de Vicenta Jarén de origen gallego y de Francisco Alonso y Trelles de origen asturiano, quien ejerció la docencia en una escuela de la zona de Navia. Es en Navia donde pasó su infancia y adolescencia y recibió instrucción en la carrera de comercio para titularse como Perito Mercantil.3 En 1875 —con 18 años de edad— emigró a América y se estableció durante dos años en Chivilcoy, un pueblo de la Provincia de Buenos Aires en Argentina. Allí alternó diferentes oficios con algunas líneas publicadas en un periódico del lugar. En Chivilcoy permaneció hasta 1877, año en que se trasladó a Montevideo, donde se quedó un corto tiempo, para radicarse definitivamente en Tala. Allí cobró fama como poeta de la vida rural uruguaya. Juventud José Alonso y Trelles (derecha) a poco tiempo de llegar a Tala. Su primer trabajo fue como contador en un almacén de ramos generales, propiedad de Juan Riccetto, con cuya hija, Dolores Riccetto, se casó años más tarde. Una figura que tuvo mucha relevancia en su vida de estos años, fue el maestro rural Joaquín Tejera, a quien había sido recomendado por su compatriota y compañero de viaje Emilio Rodríguez. Fue Tejera quien lo apoyó desde un comienzo, facilitándole un trabajo como funcionario del Correo de esa localidad, y dándole participación en el diario "El Tala", fundado por él y en el cual también oficiaban de redactores Servando Paisal, Schickendantz y Klappenbach. En 1882 contrajo matrimonio con Dolores Riccetto, y al poco tiempo se trasladó con ella al poblado de Sarandí Garupá cercano a Santana do Livramento. A partir de ese momento, se desempeñó como tenedor de libros en una casa de comercio que posteriormente se ve obligado a cerrar. Durante su estadía en esta zona, conoció al periodista y político Rafael Cabeda, con quien entabló una relación que continuó por carta al regresar a Uruguay. En este período nacieron dos hijos producto del matrimonio. Luego regresaron a Tala en 1887. Ya en Tala se desempeñó un tiempo como socio de su suegro en su actividad comercial y luego —aconsejado por su amigo Pedro Soto, quien se desempeñaba como Juez de Paz de esa localidad— decidió entregarse de lleno al estudio de la procuraduría y la escribanía. Participó de varias entidades de fomento creadas por los vecinos de su localidad, como la primera “Comisión auxiliar de Tala” para la cual lo designaron Secretario, o la "Sociedad Cosmopolita de Socorros Mutuos" en la cual se le encargó la vicepresidencia. VIDA LITERARIA Teatro Tuvo en sus manos la organización de un grupo de teatro, secundado por un grupo de aficionados al género. En el mismo, cumple variadas labores, como director, escenógrafo, apuntador, y autor de varias obras. Es debido a su trabajo en este campo, que la ciudad de Tala lo considera su primer Director Teatral. Entre las obras teatrales escritas por él se encuentran: "Un Drama en Palacio", "Caída y Redención", "Colón", "Los Veteranos", "Spion Kook", "El Falso Otelo", "Pepiyo", "Idilio Fulminante" y "Juan el Loco" publicado por intermedio del poeta Orosmán Moratorio en 1887. La mayoría de estas obras han quedado inéditas y sólo se conservan algunas de ellas. Poesía gauchesca Sus aptitudes como escritor de poesía gauchesca fueron evolucionando con el paso del tiempo y las sucesivas publicaciones de "El Tala Cómico" y "Momentáneas" donde absorbía y manifestaba la idiosincrasia de los pobladores de Tala, y de otros lugares del interior de Uruguay, como Florida, Durazno y Minas, localidades que Trelles visitó frecuentemente. Algunas de las obras encontradas en esas revistas comenzaron a ser recogidas por publicaciones como la famosa revista criolla "El Fogón" de Montevideo, con la cual contribuyó con sus textos junto a Elías Regules, Orosmán Moratorio, Alcides de María, Martiniano Leguizamón y otros poetas. Dado que revistas como "El Fogón" y "El Terruño" eran de mucho mayor tiraje que las publicaciones de Trelles, lograron popularizar algunos de sus textos. A modo de ejemplo, se puede mencionar la obra "La Güeya", publicada en el número de "Momentáneas" correspondiente al 10 de septiembre de 1899, la cual fue recogida casi de inmediato por "El Fogón". Últimos años Luego de concluida su actividad política, se radicó en Montevideo debido a los estudios de uno de sus hijos. Posteriormente, y luego de una larga preparación, Trelles emprendió un viaje a su tierra natal, en la que recorre Asturias y Galicia y visita parte de su familia. De nuevo en Uruguay, se le brindó un gran homenaje en San José el 8 de enero de 1922. Falleció en Montevideo en 1924, víctima de una larga enfermedad asociada con una peritonitis. Referencias Wikipedia—https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/José_Alonso_y_Trelles

Namaste, Although I am now residing in sunny Florida, I grew up in Queens, New York. I am the eldest daughter of Jamaican, West Indian immigrants. We were a lively family, five siblings altogether with plenty of love and joviality to go around. From early on, I loved creating stories. My brothers and sisters also keenly enjoyed listening to them. But, being the natural artist, I preferred to retreat into the silence of my room surrounded by my dolls, where we would embark on all sorts of imaginative and adventurous tales. My siblings would listen with their ears glued to the bedroom door, occasionally a giggle of delight escaped from the other side of the door. This interest in story telling gradually metamorphosed into the art of penning poetry. Over the years I have written many poems. The fascinating thing about the imaginative process that I've observed, is that there seems to be some sort of bridge that connects us to the creative source. This is similar to what I experienced in my childhood, a quiet space within, beyond me where creative ideas flow endlessly. On another note, I am also an artist. But, LOL, all of my paintings tell a story too. My work is a visual and poetic diary of my spiritual journey. From the highest peaks in the Himalayas to many of the sacred ashrams in holy India I have been blessed with the opportunity to journey through that divine land eleven times. My spiritual quest began on June 6, 1970 with the birth of my daughter. During the birth I had an amazing out-of-body-experience which catapulted me out of ordinary three dimensional awareness into an astounding, metaphysical reality which I know survives and surpasses death, misery, joy, materialism and all that is dualistic and worldly. A space of being in which Pure Love, Life and Light exists Eternally. This event inspired me to explore the intriguing inner realms of Self through Yoga, Meditation, Rosicrucianism and other spiritually laden paths. I have written two books. The first, "Sai Rapture, The Ecstatic Journey of a Modern Day Gopi " portrays my spiritual journey. The second book, "108 Bhakti Kisses, The Ecstatic Poetry of a Modern Day Gopi" is a garland of poems celebrating the divine in everything.

Alfred Charles Tomlinson, CBE (born 8 January 1927) is a British poet and translator, and also an academic and artist. He was born and raised in Penkhull in the city of Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire. After attending Longton High School, Tomlinson read English at Queens' College, Cambridge, where he studied with Donald Davie. After leaving university he spent a year in Liguria in Italy and then taught in a primary school. He later became Emeritus Professor of English Poetry at the University of Bristol, England. He and his wife Brenda now live in a Cotswold cottage at Ozleworth, near Wotton-under-Edge.[1] They met as teenagers, and have two daughters and a granddaughter. He is also an artist, and In Black and White: The Graphics of Charles Tomlinson, with an introduction by Nobel prize-winner Octavio Paz, was published in 1976. Poetry Tomlinson's first book of poetry was published in 1951, and his Collected Poems was published by the Oxford University Press in 1985, followed by the Selected Poems: 1955-1997 in 1997. His poetry has won international recognition and has received many prizes in Europe and the United States, including the 1993 Bennett Award from Hudson Review; the New Criterion Poetry Prize, 2002; the Premio Internazionale di Poesie Ennio Flaiano, 2001; and the Premio Internazionale di Poesia Attilio Bertolucci, 2004. He is an Honorary Fellow of the American Academy of the Arts and Sciences and of the Modern Language Association. Charles Tomlinson was made a CBE in 2001 for his contribution to literature. Charles Tomlinson's Selected Poems, his collections Skywriting, Metamorphoses and The Vineyard Above the Sea, amongst others, are all published by Carcanet Press. His latest collection Cracks in the Universe was published in May 2006 in Carcanet Press' Oxford Poets series. In his book Some Americans Tomlinson acknowledges his poetic debts to modern American poetry, in particular William Carlos Williams, George Oppen, Marianne Moore, and Louis Zukofsky. In his critical study Lives of Poets, Michael Schmidt observes that 'Wallace Stevens was the guiding star [Tomlinson] initially steered by'. Schmidt goes on to define the two characteristic voices of Tomlinson: 'one is intellectual, meditative, feeling its way through ideas' whilst the other voice engages with 'landscapes and images from the natural world'. Tomlinson's poetry often circles around these themes of place and return, exploring his native landscape of Stoke and the shifting cityscape of modern Bristol. In Against Extremity Tomlinson expresses a distrust of confessional verse and rejects the 'willed extremism of poets like Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton'. He has been active in the field of collaborative poetry, writing renshi under the guidance of Makoto Ooka with James Lasdun and Mikiro Sasaki. From 1985 to 2000 he recorded all of his published poetry for Keele University. Included are his Stoke-on-Trent poems, which are: At Stoke; The Slag Heap; Steel; Canal; Poem for My Father; John Maydew; The Hand at Callow Hill Farm; The Farmer's Wife; Black Brook; The Question; The Shaft; After a Death; Night Ride; Gladstone Street; Etruria Vale; Penkhull New Road; The Way In; The Tree; Midlands; Portrait of the Artist I; Portrait of the Artist II; The Hoard; Consolations for Double Bass; The Rich; Class; The Hawthorn in Trent Vale; Written on Water; The Marl Pits. Translations Tomlinson has excelled as an authoritative translator of poetry from the Russian, Spanish and Italian, including the work of Antonio Machado, Fyodor Tyutchev, César Vallejo and Attilio Bertolucci. He has collaborated with the Mexican writer Octavio Paz. He edited the seminal Oxford Book of Verse in English Translation and the Selected Poems of William Carlos Williams. Works * A Peopled Landscape, Oxford University Press, 1963 * Renga: A Chain of Poems, with Octavio Paz, Jacques Roubaud, and Edoardo Sanguineti. (Braziller, 1971) * Door in the Wall (Carcanet Press, 1999) * Selected Poems (Carcanet Press, 1999) * Annunciation (Carcanet Press, 1999) * The Vineyard Above the Sea (Carcanet Press, 1999) * American Essays (Carcanet Press, 2001) * Metamorphoses: Poetry and Translation (Carcanet Press, 2003) * Skywriting (Carcanet Press, 2003) * Cracks in the Universe (Carcanet Press, 2006) References Wikipedia - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Tomlinson

Jorge Teillier Sandoval (Lautaro, 24 de junio de 1935 - Viña del Mar, 22 de abril de 1996) fue un destacado poeta chileno exponente de la poesía lárica. Su infancia transcurrió en el sur de Chile, en la Araucanía. Desde aquellos años, coincidentes cronológicamente con la Segunda Guerra Mundial, la vida cotidiana del autor estuvo ya marcada por el contacto directo con la naturaleza y una forma de entender la tradición capaz de articular en un mismo enfoque rasgos culturales, sociales e históricos chilenos, franceses y mapuche. A la descendencia gala del autor, se acopló la tradición araucana, y prontamente, a través de la literatura, un sentido aún más universal. Dice Teillier: "No recuerdo haber intentado escribir poema alguno hasta los doce años de edad. La poesía me parecía algo perteneciente a otro mundo y prefería leer en prosa. Leía como si me hubiesen dado cuerda".1 Pero aunque desde los 12 años escribía prosa y poesía, fue a los 16, en la ciudad de Victoria donde escribió, a los 16 años, su "primer poema verdadero", o sea, explica Teillier, "el primero que vi, con incomparable sorpresa, como escrito por otro".1 Gran parte de los poemas que componen su primer libro, Para ángeles y gorriones (1956), nacieron "sobre el pupitre del liceo". De esa época liceana —especialmente fecunda para el novel autor, que colaboró activamente en diversas publicaciones locales, con poemas o pequeñas crónicas que en buena medida anticipaban el particular universo poético que más tarde consolidaría en sus libros—, recordará en 1968: "Mi mundo poético era el mismo donde también ahora suelo habitar, y que tal vez un día deba destruir para que se conserve: aquel atravesado por la locomotora 245, por las nubes que en noviembre hacen llover en pleno verano y son las sombras de los muertos que nos visitan, según decía una vieja tía; aquel poblado por espejos que no reflejan nuestra imagen sino la del desconocido que fuimos y viene desde otra época hasta nuestro encuentro, aquel donde tocan las campanas de la parroquia y donde aún se narran historias sobre la fundación del pueblo". En 1953, con 18 años de edad, Teillier emprendió viaje a Santiago para cursar estudios superiores: ingresa en el Instituto Pedagógico a estudiar Historia, haciendo latente su constante vocación por rescatar la tradición, y de ello alimentar su creación poética. En dicho contexto conocerá a muchos autores de su generación, la del 50, como a los poetas Braulio Arenas, Rolando Cárdenas, Enrique Lihn o el novelista Enrique Lafourcade, entre otros. No tardó en hacerse de un nombre en la escena santiaguina, lo que en buena parte posibilitó la publicación de su primer poemario, que fue bien acogido por la critica especializada de la época y recibió elogiosos comentarios por parte de Alone, quien destacó la simpleza de su poesía, no carente de profundidad. Por aquellos años el pulso poético teilleriano ya se hallaba relativamente consolidado, lo que puede constatarse al analizar publicaciones posteriores, en que suele reiterarse la visión de mundo expuesta en su obra debut. Considerando eso, puede decirse que se trata de uno de los pocos casos en la historia literaria nacional en que un autor es capaz de presentarse "consolidado" en su propuesta poética ya en su primer libro. Recuerda Teillier que por ese entonces "el héroe poético de mi generación era Pablo Neruda, que perseguido por el Traidor se dejaba crecer barba y atravesaba a caballo la Cordillera". Neruda, continúa Teillier, "llamaba a cantar con palabras sencillas al hombre sencillo y en nombre del realismo socialista convocaba a los poetas a construir el socialismo. Hijo de comunista, descendiente de agricultores medianos o pobres y de artesanos, yo sentimentalmente sabía que la poesía debía ser un instrumento de lucha y liberación y mis primeros amigos poetas fueron los que en ese entonces seguían el ejemplo de Neruda y luchaban por la Paz y escribían poesía social. Pero yo era incapaz de escribirla, y eso me creaba un sentimiento de culpa que aún ahora suele perseguirme. Fácilmente podía ser entonces tratado de poeta decadente, pero a mí me parece que la poesía no puede estar subordinada a ideología alguna, aun cuando el poeta como hombre y ciudadano (no quiero decir ciudadano elector, por supuesto) tiene derecho a elegir la lucha a la torre de marfil o de madera o cemento. Ninguna poesía ha calmado el hambre o remediado una injusticia social, pero su belleza puede ayudar a sobrevivir contra todas las miserias. Yo escribía lo que me dictaba mi verdadero yo, el que trato de alcanzar en esta lucha entre mí mismo y mi poesía, reflejada también en mi vida. Porque no importa ser buen o mal poeta, escribir buenos malos versos, sino transformarse en poeta, superar la avería de lo cotidiano, luchar contra el universo que se deshace, no aceptar los valores que no sean poéticos, seguir escuchando el ruiseñor de Keats, que da alegría para siempre". Terminada la universidad, ejerció la docencia en el Liceo de Lautaro. En 1963 fundó y dirigió (hasta 1965), junto con Jorge Vélez, la revista de poesía Orfeo. También dirigiría el Boletín de la Universidad de Chile. Tellier estuvo casado por un tiempo breve con Sybila Arredondo, relaciòn de la que nacieron dos hijos, Carolina y Sebastián. Después del golpe militar del 11 de septiembre de 1973, Teillier siguió fiel a su credo, aunque no se puede negar, como bien dice Marcelo Quiñones, que aparecen "símbolos o signos de indicios" que nos remiten "al drama que por diecisiete años vivió Chile. Es verdad que con el correr de los años, el poeta fue acentuando o hizo más ostensible el tono autobiográfico de su poesía, esas pequeñas confesiones como 'la noche es mi mejor amiga' o 'es mejor morir de vino que de tedio'. Pero es igualmente efectivo que la compulsiva situación que vivió Chile bajo la dictadura fue determinante para que esta poesía tan genuina —en la que más de una vez asoman las 'sombras de los amigos muertos'—, diga en tono desacostumbrado que 'el único país donde me siento extranjero es mi país' o que 'vivo en un tiempo en que mandan los padrastros'". A lo largo de su trayectoria literaria recibió numerosos galardones, incluido el Premio Anguita 1993, concedido por la Editorial Universitaria al poeta vivo más importante de Chile que no hubiese conseguido el Premio Nacional. Teillier se dedicó también a la traducción —por ejemplo, La confesión de un granuja de Sergéi Yesenin; escribió cuentos y colaboró en diversos diarios y revistas. La poesía de Teillier ha sido traducida parcialmente a varios idiomas y cuenta con dos colecciones bilingües: In order to talk with the Dead y From the country of Never-more. Sobre sus obras, el mismo Teillier ha escrito: "Creo que todos mis libros forman un solo libro, publicado en forma fragmentaria, a excepción de Crónica del forastero. Me parece que difícilmente uno tiene más de un poema que escribir en su vida. Hay varias tendencias en mis libros que van de Para ángeles y gorriones (1956) hasta Poemas del País de Nunca Jamás (1963); una descriptiva del paisaje visto como un signo que esconde otra realidad (como en los poemas El aromo o Molino de madera), otra como la historia de un personaje contada con un marco de referencia que es siempre la aldea (así en Historia de hijos pródigos), otra como el afrontar el problema del paso del tiempo, de la muerte que subyace en nosotros revelada como el fuego revela la tinta invisible por medio de la palabra (los poemas Domingo a domingo u Otoño secreto). En este sentido quiero hacer destacar que para mí la poesía es la lucha contra nuestro enemigo el tiempo, y un intento de integrarse a la muerte, de la cual tuve conciencia desde muy niño, a cuyo reino pertenezco desde muy niño, cuando sentía sus pasos subiendo la escalera que me llevaba a la torre de la casa donde me encerraba a leer". Sus influencias poéticas van desde el modernismo hispanoamericano y el creacionismo de Vicente Huidobro hasta la poesía universal de Rainer Maria Rilke. Sin embargo, se lo vincula más directamente con los poetas Friedrich Hölderlin, Georg Trakl y Sergéi Yesenin, ya que tanto ellos como él manifestaron en su escritura una profunda relación con la aldea y con el mito. Los últimos años de su vida los pasó en Cabildo, en el sector denominado El Ingenio. Murió a la edad de 60 años en el Hospital Gustavo Fricke de Viña del Mar. Sus restos mortales descansan en el cementerio de La Ligua. La poesía lírica En 1965, "movido por el impulso de configurar su espacio mítico, publicó Los poetas de los lares, ensayo en el que revisa la obra de todo un grupo de poetas que centraron su obra en la provincia, la infancia y el respeto por las tradiciones, inaugurando una importante vertiente de la poesía nacional, la poesía lárica o de los lares". La poesía lárica o de los lares, es decir, del origen o de la frontera, corresponde a la ética y estética que fundó Jorge Teillier y que transmitió en toda su obra. Esta forma de entender y crear la poesía se caracteriza por la vuelta hacia el pasado, a un paraíso perdido en el cual lo cotidiano y lo amable contrastan con la modernidad imperante en la época. Teillier hace hincapié en la búsqueda de los valores del paisaje, de la aldea y de la provincia, donde confluyen imágenes nostálgicas de la infancia perdida y de la naturaleza primigenia del mito. A través de una escritura usualmente sencilla, propuso el retorno hacia una Edad de Oro en la que el hablante lírico y el lector podrían acceder a un mundo más puro y más feliz, “un mundo mejor”, como el propio poeta diría. Premios y distinciones * Premio Canto a la Reina de la Primavera de Victoria * Premio de Federación de Estudiantes de Chile 1954, por el cuento Manzanas en la lluvia (con Manuel Rojas y José Santos González Vera como miembros del jurado) * Premio Alerce de la Sociedad de Escritores de Chile 1958 por El cielo cae con las hojas * Primer Premio del Concurso Gabriela Mistral 1960 por Los conjuros (esta obra será publicada en 1961 con el título de El árbol de la memoria) * Premio Municipal de Santiago de Poesía 1961 por El árbol de la memoria * Premio CRAV 1964 por Crónicas del forastero * Premio Conmemoración del Sesquicentenario de la Bandera Nacional 1967 * Primer Premio de los Juegos Florales 1976 de la revista Paula * Premio Eduardo Anguita 1993 * Premio del Consejo Nacional del Libro 1994 al mejor libro del año por El molino y la higuera Bibliografía * Libros de poesía * Para ángeles y gorriones (Ediciones Puelche, 1956; reeditado: 1995) * El cielo cae con las hojas (Ediciones Alerce, 1958) * El árbol de la memoria (Impreso por Arancibia Hermanos, 1961) * Poemas del País de Nunca Jamás (Colección El Viento en la Llama, dirigida por Armando Menedín, 1963) * Los trenes de la noche y otros poemas (Revista Mapocho, 1964) * Poemas secretos (Ediciones de los Anales de la Universidad de Chile, separata, 1965) * Crónica del forastero (Impreso por Arancibia Hermanos, 1968) * Muertes y maravillas (Antología, Editorial Universitaria, 1971; reeditado: 2005 y en 2011 por Ediciones Universidad Diego Portales) * Para un pueblo fantasma (Ediciones de la Universidad Católica de Valparaíso,1978; reeditado: 2005) * La Isla del Tesoro (con Juan Cristóbal, poeta peruano, Lima: 1982; reeditado: Editorial Dolmen, 1996) * Cartas para reinas de otras primaveras (Ediciones Manieristas, 1985) * "los Dominios Perdidos" (1996) * El molino y la higuera (Ediciones Azafrán, 1993) * Hotel Nube (póstumo, Ediciones LAR, 1996) * En el mudo corazón del bosque (póstumo, Editorial Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1997) Otras publicaciones * La confesión de un granuja (traducción con Gabriel Barra del libro del poeta ruso Sergéi Yesenin, Editorial Universitaria, 1973) * Los dominios perdidos (antología, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1992, segunda edición en 1994, la tercera edición en 2007 ) * Le petit Teillier illustré (con dibujos de Germán Arestizábal, Ediciones El Kultrún, 1993; segunda edición 2011, ediciones Grillom, en conjunto con "Los trenes que no has de beber) * La invención de Chile (con Armando Roa Vidal, Editorial Universitaria, 1994. Segunda edición 2011-Fondo de Cultura Económica) * Los trenes que no has de beber (con ilustraciones de Germán Arestizábal; primera edición en El Salvador; la segunda en Chile, 1994; tercera edición, 2011, Ediciones Grillom) * Poesía universal traducida por poetas chilenos (Editorial Universitaria, 1996) * Prosas (recopiladas por Ana Traverso, Editorial Sudamericana, 1999) * Entrevistas, 1962-1996 (recopiladas por Daniel Fuenzalida, Quid Ediciones, 2001) * Lo soñé o fue verdad (póstumo, Editorial Universitaria, 2003) * Confieso que he bebido, crónicas del buen comer (antología de artículos, 2011) Antologías en inglés * In Order to Talk with the Death (Traducción de Carolyne Wright, Ed. University of Texas Press, 1993) * From the Country of Nevermore (Traducción Mary Crow, Ed. Wesleyan University Press, 1990) * Antologías póstumas * Jorge Teillier, el poeta de la lluvia (Chile, Editorial Platero, 1996) * Crónicas del forastero (Argentina, Editorial Colihue, 1999) * El árbol de la memoria (España, Editorial Signos, 2000) * Morada irreal (Edición facsimilar a cargo de Ediciones DIBAM- Editorial LOM) Reediciones * Poemas del País de Nunca Jamás-Crónica del forastero (Libros completos, Tajamar Editores, 2003) * El cielo cae con las hojas-El árbol de la memoria-Los trenes de la noche (Libros completos, Tajamar Editores, 2004) * Para un pueblo fantasma/Cartas para reinas de otras primaveras- El molino y la higuera (Libros completos, Tajamar Editores, 2009) Estudios sobre su obra Por un tiempo de arraigo, Jaime Quezada-Jorge Teillier (Editorial LOM, 1996) Jorge Teillier, Poet of the Hearth, Teresa R. Stojkov (Bucknell University Press, 2002) Jorge Teillier, arquitectura del escritor, Hernán Ortega Parada (LOM Ediciones, auspiciada por el Fondo del Libro, 2004) La poesía de Jorge Teillier, Niall Binns (Ediciones LAR, 2004) Retratos de Jorge Teillier: fotografías y testimonios. Patricia García V. (Ediciones Consejo Nacional de la Cultura y de las Artes. Santiago, Chile. 2005) Textos BAJO EL CIELO NACIDO TRAS LA LLUVIA Bajo el cielo nacido tras la lluvia escucho un leve deslizarse de remos en el agua, mientras pienso que la felicidad no es sino un leve deslizarse de remos en el agua. O quizás no sea sino la luz de un pequeño barco, esa luz que aparece y desaparece en el oscuro oleaje de los años lentos como una cena tras un entierro. O la luz de una casa hallada tras la colina Cuando ya creíamos que no quedaba sino andar y andar. O el espacio del silencio entre mi voz y la voz de alguien revelándome el verdadero nombre de las cosas con sólo nombrarlas: "álamos", "tejados". La distancia entre el tintineo del cencerro en el cuello de la oveja al amanecer y el ruido de una puerta cerrándose tras una fiesta. El espacio entre el grito del ave herida en el pantano, y las alas plegadas de una mariposa sobre la cumbre de la loma barrida por el viento. Eso fue la felicidad: dibujar en la escarcha figuras sin sentido sabiendo que no durarían nada, cortar una rama de pino para escribir un instante nuestro nombre en la tierra húmeda, atrapar una plumilla de cardo para detener la huida de toda una estación. Así era la felicidad: breve como el sueño del aromo derribado, o el baile de la solterona loca frente al espejo roto. Pero no importa que los días felices sean breves como el viaje de la estrella desprendida del cielo, pues siempre podremos reunir sus recuerdos, así como el niño castigado en el patio encuentra guijarros para formar brillantes ejércitos. Pues siempre podremos estar en un día que no ayer ni mañana, mirando el cielo nacido tras la lluvia y escuchando a lo lejos un leve deslizarse de remos en el agua. BOTELLA AL MAR Y tú quieres oír, tú quieres entender. Y yo te digo: olvida lo que oyes, lees o escribes. Lo que escribo no es para ti, ni para mí, ni para los iniciados. Es para la niña que nadie saca a bailar, es para los hermanos que afrontan la borrachera y a quienes desdeñan los que se creen santos, profetas o poderosos. Referencias Wikipedia - http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jorge_Teillier

Augustus Montague Toplady (4 November 1740– 11 August 1778) was an Anglican cleric and hymn writer. He was a major Calvinist opponent of John Wesley. He is best remembered as the author of the hymn “Rock of Ages”. Three of his other hymns– “A Debtor to Mercy Alone”, “Deathless Principle, Arise” and “Object of My First Desire”– are still occasionally sung today, though all three are far less popular than “Rock of Ages”. Background and early life, 1740–55 Augustus Toplady was born in Farnham, Surrey, England in November 1740. His father, Richard Toplady, was probably from Enniscorthy, County Wexford in Ireland. Richard Toplady became a commissioned officer in the Royal Marines in 1739; by the time of his death, he had reached the rank of major. In May 1741, shortly after Augustus’ birth, Richard participated in the Battle of Cartagena de Indias (1741), the most significant battle of the War of Jenkins’ Ear (1739–42), during the course of which he died, most likely of yellow fever, leaving Augustus’ mother to raise the boy alone. Toplady’s mother, Catherine, was the daughter of Richard Bate, who was the incumbent of Chilham from 1711 until his death in 1736. Catherine and her son moved from Farnham to Westminster. He attended Westminster School from 1750 to 1755. Trinity College, Dublin: 1755–60 In 1755, Catherine and Augustus moved to Ireland, and Augustus was enrolled in Trinity College, Dublin. Shortly thereafter, in August 1755, the 15-year-old Toplady attended a sermon preached by James Morris, a follower of John Wesley, in a barn in Codymain, co. Wexford (though in his Dying Avowal, Toplady denies that the preacher was directly connected to Wesley, with whom he had developed a bitter relationship). He would remember this sermon as the time at which he received his effectual calling from God. Having undergone his religious conversion under the preaching of a Methodist, Toplady initially followed Wesley in supporting Arminianism. In 1758, however, the 18-year-old Toplady read Thomas Manton’s seventeenth-century sermon on John 17 and Jerome Zanchius’s Confession of the Christian Religion (1562). These works convinced Toplady that Calvinism, not Arminianism, was correct. In 1759, Toplady published his first book, Poems on Sacred Subjects. Following his graduation from Trinity College in 1760, Toplady and his mother returned to Westminster. There, Toplady met and was influenced by several prominent Calvinist ministers, including George Whitefield, John Gill, and William Romaine. It was John Gill who in 1760 urged Toplady to publish his translation of Zanchius’s work on predestination, Toplady commenting that “I was not then, however, sufficiently delivered from the fear of man.” Church ministry: 1762–78 In 1762, Edward Willes, the Bishop of Bath and Wells, ordained Toplady as an Anglican deacon, appointing him curate of Blagdon, located in the Mendip Hills of Somerset. Toplady wrote his famous hymn “Rock of Ages” in 1763. A local tradition– discounted by most historians– holds that he wrote the hymn after seeking shelter under a large rock at Burrington Combe, a magnificent ravine close to Blagdon, during a thunderstorm. Upon being ordained priest in 1764, Toplady returned to London briefly, and then served as curate of Farleigh Hungerford for a little over a year (1764–65). He then returned to stay with friends in London for 1765–66. In May 1766, he became incumbent of Harpford and Venn Ottery, two villages in Devon. In 1768, however, he learned that he had been named to this incumbency because it had been purchased for him; seeing this as simony, he chose to exchange the incumbency for the post of vicar of Broadhembury, another Devon village. He would serve as vicar of Broadhembury until his death, although he received leave to be absent from Broadhembury from 1775 on. Toplady never married, though he did have relationships with two women. The first was Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon, the founder of the Countess of Huntingdon’s Connexion, a Calvinist Methodist series of congregations. Toplady first met Huntingdon in 1763, and preached in her chapels several times in 1775 during his absence from Broadhembury. The second was Catharine Macaulay, whom he first met in 1773, and with whom he spent a large amount of time in the years 1773–77. Animals and Natural World Toplady was a prolific essayist and letter correspondent and wrote on a wide range of topics. He was interested in the natural world and in animals. He composed a short work “Sketch of Natural History, with a few particulars on Birds, Meteors, Sagacity of Brutes, and the solar system”, wherein he set down his observations about the marvels of nature, including the behaviour of birds, and illustrations of wise actions on the part of various animals. Toplady also considered the problem of evil as it relates to the sufferings of animals in “A Short Essay on Original Sin”, and in a public debate delivered a speech on “Whether unnecessary cruelty to the brute creation is not criminal?”. In this speech he repudiated brutality towards animals and also affirmed his belief that the Scriptures point to the resurrection of animals. Toplady’s position about animal brutality and the resurrection were echoed by his contemporaries Joseph Butler, Richard Dean, Humphry Primatt and John Wesley, and throughout the nineteenth century other Christian writers such as Joseph Hamilton, George Hawkins Pember, George N. H. Peters, Joseph Seiss, and James Macauley developed the arguments in more detail in the context of the debates about animal welfare, animal rights and vivisection. Calvinist controversialist: 1769–78 Toplady’s first salvo into the world of religious controversy came in 1769 when he wrote a book in response to a situation at the University of Oxford. Six students had been expelled from St Edmund Hall because of their Calvinist views, which Thomas Nowell criticised as inconsistent with the views of the Church of England. Toplady then criticised Nowell’s position in his book The Church of England Vindicated from the Charge of Arminianism, which argued that Calvinism, not Arminianism, was the position historically held by the Church of England. 1769 also saw Toplady publish his translation of Zanchius’s Confession of the Christian Religion (1562), one of the works which had convinced Toplady to become a Calvinist in 1758. Toplady entitled his translation The Doctrine of Absolute Predestination Stated and Asserted. This work drew a vehement response from John Wesley, thus initiating a protracted pamphlet debate between Toplady and Wesley about whether the Church of England was historically Calvinist or Arminian. This debate peaked in 1774, when Toplady published his 700-page The Historic Proof of the Doctrinal Calvinism of the Church of England, a massive study which traced the doctrine of predestination from the period of the Early Church through to William Laud. The section about the Synod of Dort contained a footnote identifying five basic propositions of the Calvinist faith, arguably the first appearance in print of the summary of Calvinism known as the “five points of Calvinism”. The relationship between Toplady and Wesley that had initially been cordial, involving exchanges of letters in Toplady’s Arminian days, became increasingly bitter and reached its nadir with the “Zanchy affair”. Wesley took exception to the publication of Toplady’s translation of Zanchius’s work on predestination in 1769 and published, in turn, an abridgment of that work titled “The Doctrine of Absolute Predestination Stated and Asserted”, adding his own comment that “The sum of all is this: One in twenty (suppose) of mankind are elected; nineteen in twenty are reprobated. The elect shall be saved, do what they will; the reprobate will be damned, do what they can. Reader believe this, or be damned. Witness my hand.” Toplady viewed the abridgment and comments as a distortion of his and Zanchius’s views and was particularly enraged that the authorship of these additions were attributed to him, as though he approved of the content. Toplady published a response in the form of “A Letter to the Rev Mr John Wesley; Relative to His Pretended Abridgement of Zanchius on Predestination”. Wesley never publicly accepted any wrongdoing on his part and seemingly denied his authorship of the comments contained in his abridgement when, in his 1771 work “The Consequenses Proved” that responded to Toplady’s letter, he ascribed his additions to Toplady. Subsequently Wesley avoided direct correspondence with Toplady, famously stating in a letter of 24 June 1770 that “I do not fight with chimney-sweepers. He is too dirty a writer for me to meddle with. I should only foul my fingers. I read his title-page, and troubled myself no farther. I leave him to Mr Sellon. He cannot be in better hands.” Last years Toplady spent his last three years mainly in London, preaching regularly in a French Calvinist chapel at Orange Street (off of Haymarket), most spectacularly in 1778, when he appeared to rebut charges being made by Wesley’s followers that he had renounced Calvinism on his deathbed. Toplady died of tuberculosis on 11 August 1778. He was buried at Whitefield’s Tabernacle, Tottenham Court Road. Hymns Compared with Christ, in all beside n. 760 in The Church Hymn book 1872 (1772) Deathless spirit, now arise n. 1381 in The Church Hymn book 1872 (1776) Holy Ghost, dispel our sadness n. 80 in The Church Hymn book 1872 (1776). Modernising of John Christian Jacobi’s translation (1725) of Paul Gerhardts hymn from 1653. How happy are the souls above n. 1434 in The Church Hymn book 1872 (1776) (? A. M. Topladys text) Inspirer and hearer of prayer n. 30 in The Church Hymn book 1872 (1774) O thou, that hear’st the prayer of faith n. 642 in The Church Hymn book 1872 (1176) Praise the Lord, who reigns above n. 160 in The Church Hymn book 1872 (1759) Rock of ages, cleft for me n. 697 in The Church Hymn book 1872 (1776) Surely Christ thy griefs hath borne n. 443 in The Church Hymn book 1872 (1759) What, though my frail eye-lids refuse n. 29 in The Church Hymn book 1872 (1774) When langour and disease invade n. 1032 in The Church Hymn book 1872 (1778) Your harps, ye trembling saints n. 861 in The Church Hymn book 1872 (1772) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Augustus_Toplady

Juan de Timoneda (o Joan de Timoneda) (Valencia, entre 1518 y 1520-1583) fue un escritor, dramaturgo y editor español. Es conocido fundamentalmente por su labor compilatoria de poesía popular (lírica cancioneril y romances), por sus ediciones de teatro (a su labor debemos el conocimiento de los pasos de Lope de Rueda, aunque los modificó, fundamentalmente en los pasajes más cómicos de bobos o rufianes)1 y por su conjunto de relatos El patrañuelo (Valencia, 1567), adaptaciones de novelle italianas del estilo de Boccaccio o Bandello. Publicó casi toda su obra en castellano,2 aunque también dio a la imprenta obras en catalán: una antología de poesía trovadoresca titulada Flor de enamorados y algunos autos sacramentales. Antes de dedicarse al negocio de la librería fue zurrador de pieles; quizá debido a que hacía encuadernaciones amplió el negocio como librero. También se sabe que fue actor. En 1547 ya comerciaba con libros propios y ajenos. Estuvo casado con Isabel Ferrandis, de la que tuvo tres hijos; uno de ellos, Bautista, prosiguió a la muerte del padre con el negocio familiar. Obra Su obra literaria se clasifica en tres facetas: dramaturgo, narrador y colector de romances. Pero es famoso sobre todo como autor dramático (es citado muchas veces como uno de los más legítimos precursores de Lope de Vega). Su obra es parcialmente original, ya que en ocasiones se limita a adaptar o traducir sus modelos, si bien con gran talento lírico y eficacia dramática. Autor dramático y sobre todo adaptador, publicó obras escénicas religiosas. Su Ternario sacramental (Valencia, 1575) reúne seis autos sacramentales entre los cuales destaca como mejor el de la Oveja perdida, y los dos Ternarios sacramentales de 1575 que reflejan las nuevas orientaciones de la iglesia española; anterior a estos, hay una pieza suya en valenciano, Aucto de la Iglésia. Es el autor de los únicos autos sacramentales en catalán: L'església militant (La iglesia militante) y el Castell d'Emaús (Castillo de Emaús). Estas obras estaban concebidas para la exaltación de la eucaristía, como elemento de propaganda para defender la doctrina católica en contra de la Reforma luterana y la protestante. Su obra escénica profana forma una colección titulada Turiana (Valencia, 1564 y 1565), que recoge varias comedias, farsas, pasos y entremeses. En Las tres comedias del facundissimo poeta Juan Timoneda (Valencia, 1559) traduce Los dos Menecmos y el Anfitrión del dramaturgo latino Plauto, y añade además la Comedia Carmelia o Cornelia. Como narrador tuvo un gran papel en la evolución del género novelístico en español, pues compuso una Sobremesa y alivio de caminantes (Zaragoza y Medina del Campo, 1563), miscelánea de dichos agudos y cuentecillos, el Buen avíso y portacuentos (Valencia, 1564) y, sobre todo, un famoso libro titulado El patrañuelo (Valencia, 1567), conjunto de novelas muy interesantes-que él denomina patrañas- tomadas del italiano y actualizadas, aclimatadas y narradas en un castellano familiar. Las fuentes de esta obra son los novellieri Masuccio Salernitano, Giovanni Boccaccio, Mateo Bandello, el poeta Ludovico Ariosto y las Gesta romanorum, entre otras. Como compilador y editor de romances, publicó una Rosa de romances (Valencia, 1573) dividida en cuatro partes temáticas en su mayor parte sobre historia de España, romana y troyana, y Flor de enamorados, Sarao; también compiló y editó diferentes cancioneros, como Cancionero llamado Sarao de Amor (1561), Villete de amor (quizá de 1565), Enredo de amor (1573), Guisadillo de amor (1573) y el Truhanesco (también de 1573), y dio a la estampa numerosos pliegos sueltos. También compuso un Libro llamado ingenio, del juego de marro de punta, uno de los muchos tratados españoles sobre el juego de damas en los siglos XVI y XVII. Referencias Wikipdia-http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juan_de_Timoneda

José Juan Tablada (Coyoacán, México 3 de abril de 1871 - Nueva York, Estados Unidos, 2 de agosto de 1945) fue un poeta, periodista y diplomático mexicano. Estudios Estudió en Colegio Militar en el Castillo de Chapultepec. Continuó sus estudios en la Escuela Nacional Preparatoria, donde aprendió pintura, la cual fue una de sus aficiones. Trabajó como empleado administrativo de los ferrocarriles, y conoció de niño al poeta ciego Manuel M. Flores. Vida profesional En 1890, con 19 años, empezó a colaborar en El Universal con poemas y crónicas dominicales en la sección llamada Rostros y máscaras. Colaboró también para El Mundo Ilustrado, Revista de Revistas, Excélsior, y el Universal Ilustrado. Trabajó también para periódicos de Caracas, Bogotá, La Habana y Nueva York. Escribió para revistas literarias como la Revista Azul, la Revista Moderna, La Falange, El Maestro. Fue fundador de la revista Mexican Art and Life. En 1894 publicó en la Revista Azul, el poema "Ónix" el cual lo dio a conocer como un autor prestigioso. Su primer libro de poesía El florilegio lo publicó en 1899. Como Modernista en su primera etapa, defendió esta corriente en la Revista Moderna, en la cual publicó y tradujo artículos entre 1889 y 1911. Vida política Intervinó en la política y llegó a ocupar puestos diplomáticos en Japón, Francia, Ecuador, Colombia y Estados Unidos. En su viaje a Japón, en 1900, mostró interés por el ejemplo naturalista de los japoneses cuya estética, según él, permitía una interpretación plástica de la naturaleza. Fue opositor de la política de Francisco I. Madero y publicó una sátira llamada Madero-Chantecler en 1910. Colaboró para el gobierno de Victoriano Huerta y tras la caída de este en 1914, se trasladó a Nueva York. En 1918 el presidente Venustiano Carranza lo nombró secretario del Servicio Exterior, por tal motivo se mudó a Caracas donde realizó una labor cultural, impartiendo conferencias y realizando publicaciones. En 1920 se trasladó a Quito, pero decidió renunciar a su puesto diplomático por no adaptarse a la altura sobre el nivel del mar de la ciudad. Tras una breve estancia en la Ciudad de México, regresó a Nueva York y fundó la Librería de los Latinos. Durante un breve regreso a la Ciudad de México entre 1922 y 1923, un grupo de escritores lo nombró "poeta representativo de la juventud". Residiendo en Nueva York fue nombrado miembro correspondiente de la Academia Mexicana de la Lengua en 1928. En 1935 regresó a México y vivió en Cuernavaca, en 1941 fue nombrado miembro de número de la Academia Mexicana de la Lengua para ocupar el sillón VIII. A mediados de 1945 regresó a Nueva York, siendo vicecónsul, pero murió el 2 de agosto del mismo año. La Academia Mexicana gestionó el traslado de sus restos mortales los cuales fueron sepultados en la Rotonda de las Personas Ilustres. Obra En sus escritos hizo uso indiscriminado de metáforas, como luego lo harían los ultraístas. Además escribió caligramas al mismo tiempo que Guillaume Apollinaire. Estudió el arte hispanoamericano, el precolombino y el arte contemporáneo. Influyó y apoyó a artistas como Ramón López Velarde, José Clemente Orozco y Diego Rivera entre otros. Tablada también es reconocido como el iniciador de la poesía moderna mexicana, y se le atribuye la introducción del haikú en la literatura hispana. El compositor Edgar Varèse escribió en 1921 una cantata, “Offrandes”, con un poema de Tablada y otro de Vicente Huidobro. Referencias Wikipedia - http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/José_Juan_Tablada

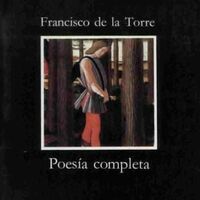

Francisco de la Torre, (¿1534 - 1594?), poeta español de la segunda fase del Renacimiento, perteneciente a la Escuela de Salamanca, que no hay que confundir con el poeta homónimo de la primera mitad del XVI. Casi nada se sabe sobre su vida y sin duda es el poeta más misterioso del siglo XVI. Nada más que una suma de conjeturas extraídas de los débiles indicios que ofrecen sus versos es la biografía bosquejada por Aureliano Fernández-Guerra como discurso de entrada en la Real Academia de la Lengua en 1857. Según este autor, habría nacido en Torrelaguna hacia 1534, habría estudiado en Alcalá de Henares y seguido la carrera militar en Italia, para al final de su vida hacerse clérigo. Un manuscrito de sus poesías circulaba a principios del siglo XVII con una Aprobación de Alonso de Ercilla, que murió en 1594, y llamó la atención de Quevedo, quien lo compró y editó junto a las obras de fray Luis de León en 1631 para combatir con buenos ejemplos de poesía clásica los excesos del Culteranismo. Quevedo se preocupó de indagar sobre el autor del manuscrito, que el librero le vendió con desprecio, pero no pudo sacar nada en limpio; es más, en él estaba "en cinco partes borrado el nombre del autor con tanto cuidado, que se añadió humo a la tinta". Cuando en 1753 José Luis Velázquez reimprimió las obras de Francisco de la Torre en Madrid pensó que su autor era en realidad el propio Francisco de Quevedo, teoría que la crítica moderna rechaza con unanimidad desde Manuel José Quintana en el siglo XIX. Sus obras han sido editadas modernamente por Alonso Zamora Vicente en la colección Clásicos Castellanos, en 1944, y hay otras posteriores no menos notables. En un ensayo reciente, Antonio Alatorre insiste, sin aportar detalles biográficos nuevos, que "Francisco de la Torre nació a mediados del siglo XVI en Santa Fe de Bogotá, donde parece haber pasado toda su vida". Muy influido por el Petrarquismo, algunos de sus poemas son traducciones de escritores italianos, sobre todo Benedetto Varchi, y construye su cancionero en torno a una tal Filis, que al retorno del amante de Italia encuentra casado con otro. Por modelos tiene a Garcilaso y Horacio dentro de una cosmovisión inmersa por completo en el Neoplatonismo, pero le singulariza su finísima sensibilidad ante temas como la noche, la tórtola solitaria, el dolor por la ausencia de la amada, etcétera. En Francisco de la Torre la existencial melancolía garcilasiana se aquilata, depura y refina aún más todavía hasta llegar casi a lo prerromántico; al igual que el poeta toledano, su actitud es paganizante por extremo. La obra está dividida en tres libros: Libros primero y segundo de los versos líricos, donde destacan algunos sonetos de extremada perfección formal y emoción, como los dedicados A la noche y a temas pastoriles, y Libro tercero de los versos adónicos, así como ocho églogas reunidas bajo el título de Bucólica del Tajo. Sus Canciones gozan de justa fama, en especial A la tórtola y A la cierva herida. También hizo algunas aportaciones a la métrica española, como la llamada estrofa de La Torre o sáfico adónica, que fue seguramente el primero en cultivar. También escribió endechas en heptasílabo suelto y en hexasílabos: Endecha II El pastor más triste que ha seguido el cielo, dos fuentes sus ojos y un fuego su pecho. Endecha IV Veneno su pecho, yerba y áspid hecho, dentro de mi pecho, crudo amor, te siento. Referencias Wikipedia - http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francisco_de_la_Torre

Nasco a Ceprano (Fr), il 2 luglio del 1965. Trasferito a Roma nel 1972, qui cresco e la Capitale diventa la mia città. Fin da giovane si fa sentire la voglia di scrivere. Più di un romanzo fantasy iniziato, ma mai nessuno finito. La passione per la lettura è forte. Per lo più romanzi, fantasy, gialli, fantascienza, qualche saggio e la passione per quelli storici, soprattutto ambientati nell'antica Roma. I racconti di Danila Comastri Mintanari diventano fonte di ispirazione. Scriverò il primo racconto ad ambientazione storica, Arcanum, auto pubblicato su Amazon. Inizio nel frattempo a buttar giù qualche poesia, niente di che. Una decina di anni fa'inizio a scrivere in maniera più serrata. Sempre auto pubblicati prendono luce L'anima scritta, poi l'anima nel cuore e uno per un pubblico più adulto...Sotto i vestiti l'anima. Solo nel 2022 parte un progetto che vedrà pubblicato da Francesco Tozzuolo Editore il primo libro "vero", Raccolta di pezzi d'anima. Ed ora eccomi qua. Sinceramente cerco persone che sappiano giudicare i miei scritti. A me tutto ciò che scrivo pare pessimo, aspetto il giudizio di chi è sicuramente migliore di me

Edward William Thomson was born in Toronto township, county of Peel, Ontario, February 12th, 1849. His father was William Thomson, grandson of Archibald Thomson, the first settler in Scarboro. His grandfather Edward William Thomson, was present at the taking of Detroit, and served with distinction under Brock at Queenston Heights; and was afterwards well known in Upper Canada as Col. E. W. Thomson of the Legislative Council, and as the one successful opponent of William Lyon Mackenzie in an election for the Legislature. The mother of the present E. W. Thomson was Margaret Hamilton Foley, sister of the Hon. M. H. Foley, twice Postmaster-General of the united Canadas. The future poet was educated at the Brantford Grammar School, and at the Trinity College Grammar School at Weston; but when about fourteen years of age, he was sent to an uncle and aunt in Philadelphia and given a position in a wholesale mercantile house as 'office junior.' Finding this employment very uncongenial, he enlisted in the Union army, in October, 1864, as a trooper in the 3rd Pennsylvania Cavalry. This corps was engaged twice at Hatcher's Run, and was with Grant when he took Petersburgh. Discharged in August, 1865, he returned to the parental home at Chippewa, Ontario. In June, 1866, when the Fenians raided Upper Canada, young Thomson promptly enlisted in the Queen's Own, and was in action at the Ridgeway fight. The following year he entered the profession of Civil Engineering, and in 1872 was registered a Provincial Land Surveyor. He practised his profession until December, 1878, when at the invitation of the Hon. George Brown, he joined the staff of The Globe, Toronto, as an editorial writer. Four years later the Manitoba boom attracted him, and he practised surveying for two or three years in Winnipeg. In 1885, he rejoined The Globe staff, but retired again in 1891, because of his opposition to the Liberal policy of Unrestricted Reciprocity. Shortly afterwards he was invited to join the staff of the Youth's Companion. He accepted and remained for eleven years. Since 1903, he has lived in Ottawa, employed as a newspaper correspondent and engaged in literary work.The Many-Mansioned House and Other Poems was issued in 1909. His poems, like his short stories, are lucid, vital, original. References http://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/garvin/poets/thomson.html

Mi nombre es Sonia torres mora soy la tercera de nueve hermanos.nací en Vista Hermosa Michoacán México. Y desde muy pequeña me sentía un poco diferente a los demás niños de mi edad.me gustaba caminar y ver el amanecer con mi libreta lista como si fuese cámara para plasmar lo que veía y oía desde el canto de los pajaros...hasta una hoja seca que se desprendía...

Diego Vicente Tejera Calzado (20 de noviembre de 1848 - 6 de noviembre de 1903) fue un escritor, poeta, intelectual, político y patriota cubano del siglo XIX e inicios del siglo XX. Independentista convencido, también fue un importante precursor del movimiento socialista en Cuba. Nació el 20 de noviembre de 1848 en la ciudad de Santiago de Cuba, Cuba. Sus padres fueron Diego Vicente Tejera y Piloña y Ascensión Calzado y Portuondo. En su adolescencia, comenzó los estudios de sacerdocio, pero pronto los abandonó, pues no sentía la vocación. A los 16 años, intentó alistarse en el ejército español, para ir a combatir a República Dominicana, por aquel entonces bajo ocupación española. Al no ser aceptado, rompe con el Gobierno colonial español de Cuba y comienza a distribuir panfletos anticoloniales en su ciudad. En 1866, viaja a Estados Unidos. Meses después, se traslada a Europa. En un periplo de varios meses, recorre París, Londres, Bélgica y el Rin. En septiembre de 1868, al estallar la revolución contra Isabel II en España, Diego viaja a Madrid. Poco después, marcha a Puerto Rico, donde toma parte en el Grito de Lares. Tras el fracaso de este, Diego se exilia en Venezuela, junto a Ramón Emeterio Betances. En Caracas, finaliza sus estudios y luego combate contra Guzmán Blanco. Herido y capturado, debe exiliarse en Barcelona, España. A partir de ese momento, comienza su obra intelectual. Tiempo después, viaja a Nueva York, donde entra en contacto con los exiliados cubanos e intenta solicitar un viaje a Cuba, para unirse a los independentistas en la Guerra de los Diez Años (1868-1878), pero le es denegada su solicitud. Terminada la guerra en Cuba, Diego regresa a su país y colabora con varias publicaciones. Pronto, intenta regresar a España, pero su barco naufraga y debe recalar en Nueva York. En dicha ciudad, contacta de nuevo con los independentistas cubanos exiliados y conoce a José Martí. En 1883, se casó en La Habana con una joven llamada María Teresa, con quien tuvo tres hijos, llamados Diego Luis, Ascensión y Paul Louis. Entre 1888 y 1892, residió en París, pero vino a Cuba para la inauguración del Teatro Terry, en la ciudad de Cienfuegos. Enfermo, regresa a Nueva York en 1894. Su enfermedad le impide unirse a los independentistas cubanos en la Guerra Necesaria (1895-1898). Continúa con su trabajo periodístico e intelectual en Estados Unidos hasta el fin de la guerra en Cuba (1898), cuando regresa a la Isla. De ideas marxistas, Tejera funda el primer Partido Socialista Cubano, el 22 de mayo de 1899, de corta vida. En 1900, intenta refundar el partido con el nombre de Partido Popular, pero fracasa. Falleció de un cáncer de garganta en La Habana, poco antes de cumplir los 55 años de edad, el 6 de noviembre de 1903. Referencias Wikipedia – https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diego_Vicente_Tejera