Info

Violet Jacob (1 September 1863– 9 September 1946) was a Scottish writer, now known especially for her historical novel Flemington and her poetry, mainly in Scots. Life She was born Violet Augusta Mary Frederica Kennedy-Erskine, the daughter of William Henry Kennedy-Erskine (1 July 1828– 15 September 1870) of Dun, Forfarshire, a Captain in the 17th Lancers and Catherine Jones (d. 13 February 1914), the only daughter of William Jones of Henllys, Carmarthenshire. Her father was the son of John Kennedy-Erskine (1802–1831) of Dun and Augusta FitzClarence (1803–1865), the illegitimate daughter of King William IV and Dorothy Jordan. She was a great-granddaughter of Archibald Kennedy, 1st Marquess of Ailsa. The area of Montrose where her family seat of Dun was situated was the setting for much of her fiction. She married, on 27 October 1894, Arthur Otway Jacob, an Irish Major in the British Army, and accompanied him to India where he was serving. Her book Diaries and letters from India 1895-1900 is about their stay in the Central Indian town of Mhow. The couple had one son, Harry, born in 1895, who died as a soldier at the battle of the Somme in 1916. Arthur died in 1936, and Violet returned to live at Kirriemuir, in Angus. Scots poetry In her poetry Violet Jacob was associated with Scots revivalists like Marion Angus, Alexander Gray and Lewis Spence in the Scottish Renaissance, which drew its inspiration from early Scots poets such as Robert Henryson and William Dunbar, rather than from Robert Burns. She is commemorated in Makars’ Court, outside the Writers’ Museum, Lawnmarket, Edinburgh. Selections for Makars’ Court are made by the Writers’ Museum, The Saltire Society and The Scottish Poetry Library. The Wild Geese, which takes the form of a conversation between the poet and the North Wind, is a sad poem of longing for home. It was set to music as Norlan’ Wind and popularised by Angus singer and songmaker Jim Reid, who set to music other poems by Jacob and other Angus poets such as Marion Angus and Helen Cruikshank. Another popular version, sung by Cilla Fisher and Artie Trezise, appeared on their 1979 Topic Records album Cilla and Artie.

Lizelia Augusta Jenkins Moorer (September 1868 - May 24, 1936) was a poet and teacher in Orangeburg, South Carolina. She taught at the Normal and Grammar Schools, Claflin University, Orangeburg, South Carolina from 1895 to 1899. In 1907, she published a collection of poems, “Prejudice Unveiled and Other Poems”. Her work was called, by Joan R. Sherman, the “best poems on racial issues written by any black woman until the middle of the century”. Moorer attacks “lynching, debt peonage, white rape, Jim Crow segregation, and the hypocrisy of the church and the white press”. Moorer was born in September 1868 to Warren D. Jenkins and Mattie Miller in Pickens, South Carolina. In 1899, she married Jacob Moorer, an attorney in Orangeburg who frequently saw cases defending the rights of blacks against what he saw as a prejudiced legal system in South Carolina. In particular, he fought against the constitutionality of election law in the 1895 South Carolina Constitution. Lizelia was also a very strong activist. Beyond her poetry, she was active in the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, serving as State Vice-President in South Carolina in 1910. In 1924, she attended the 1924 Methodist Episcopal Church General Conference where she gave a speech arguing that women should be allowed to be ordained within the Methodist Church. During that conference, women were, indeed, given the right to be ordained as local deacons and elders.

Mary Elizabeth Coleridge (23 September 1861– 25 August 1907) was a British novelist and poet who also wrote essays and reviews. She taught at the London Working Women’s College for twelve years from 1895 to 1907. She wrote poetry under the pseudonym Anodos, taken from George MacDonald; other influences on her were Richard Watson Dixon and Christina Rossetti. Robert Bridges, the Poet Laureate, described her poems as 'wonderously beautiful… but mystical rather and enigmatic’. Coleridge published five novels, the best known of those being The King with Two Faces, which earned her £900 in royalties in 1897. She travelled widely throughout her life, although her home was in London, where she lived with her family. Her father was Arthur Duke Coleridge who, along with the singer Jenny Lind, was responsible for the formation of the London Bach Choir in 1875. Other family friends included Robert Browning, Alfred, Lord Tennyson, John Millais and Fanny Kemble. Mary Coleridge was the great-grandniece of Samuel Taylor Coleridge and the great niece of Sara Coleridge, the author of Phantasmion. She died from complications arising from appendicitis while on holiday in Harrogate in 1907, leaving an unfinished manuscript for her next novel and hundreds of unpublished poems. Eight of her poems, including “The Blue Bird”, were set to music for chorus by Charles Villiers Stanford, and “Thy Hand in Mine” was set by Frank Bridge. A family friend, the composer Hubert Parry, also set several of her poems as songs for voice and piano. Published works Fancy’s Following. Oxford: Daniel, 1896 (poems) The King with Two Faces. London: Edward Arnold, 1897 The Seven Sleepers of Ephesus. London: Chatto & Windus, 1898 Non Sequitur. London: J. Nisbet, 1900 (essays) The Fiery Dawn. London: Edward Arnold, 1901 The Shadow on the Wall: a romance. London: Edward Arnold, 1904 The Lady on the Drawingroom Floor. London: Edward Arnold, 1906kiren Holman Hunt. London: T. C. & E. C. Jack; New York: F. A. Stokes Co., [1908] (three numbers of Masterpieces in Colour issued together: Millais / by A. L. Baldry– Holman Hunt / by M. E. Coleridge– Rossetti / by L. Pissarro.) Poems by Mary E. Coleridge. London: Elkin Mathews, 1908 Songs not listed

Francis Beaumont (1584– 6 March 1616) was a dramatist in the English Renaissance theatre, most famous for his collaborations with John Fletcher. Beaumont was the son of Sir Francis Beaumont of Grace Dieu, near Thringstone in Leicestershire, a justice of the common pleas. His mother was Anne, the daughter of Sir George Pierrepont (d. 1564), of Holme Pierrepont, and his wife Winnifred Twaits. Beaumont was born at the family seat and was educated at Broadgates Hall (now Pembroke College, Oxford) at age thirteen. Following the death of his father in 1598, he left university without a degree and followed in his father’s footsteps by entering the Inner Temple in London in 1600. Accounts suggest that Beaumont did not work long as a lawyer. He became a student of poet and playwright Ben Jonson; he was also acquainted with Michael Drayton and other poets and dramatists, and decided that was where his passion lay. His first work, Salmacis and Hermaphroditus, appeared in 1602. The 1911 edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica describes the work as “not on the whole discreditable to a lad of eighteen, fresh from the popular love-poems of Marlowe and Shakespeare, which it naturally exceeds in long-winded and fantastic diffusion of episodes and conceits.” In 1605, Beaumont wrote commendatory verses to Jonson’s Volpone. Beaumont’s collaboration with Fletcher may have begun as early as 1605. They had both hit an obstacle early in their dramatic careers with notable failures; Beaumont’s The Knight of the Burning Pestle, first performed by the Children of the Blackfriars in 1607, was rejected by an audience who, the publisher’s epistle to the 1613 quarto claims, failed to note “the privie mark of irony about it;” that is, they took Beaumont’s satire of old-fashioned drama as an old-fashioned drama. The play received a lukewarm reception. The following year, Fletcher’s Faithful Shepherdess failed on the same stage. In 1609, however, the two collaborated on Philaster, which was performed by the King’s Men at the Globe Theatre and at Blackfriars. The play was a popular success, not only launching the careers of the two playwrights but also sparking a new taste for tragicomedy. According to a mid-century anecdote related by John Aubrey, they lived in the same house on the Bankside in Southwark, “sharing everything in the closest intimacy.” About 1613 Beaumont married Ursula Isley, daughter and co-heiress of Henry Isley of Sundridge in Kent, by whom he had two daughters, one posthumous. He had a stroke between February and October 1613, after which he wrote no more plays, but was able to write an elegy for Lady Penelope Clifton, who died 26 October 1613. Beaumont died in 1616 and was buried in Westminster Abbey. Although today Beaumont is remembered as a dramatist, during his lifetime he was also celebrated as a poet. Beaumont’s plays It was once written of Beaumont and Fletcher that “in their joint plays their talents are so... completely merged into one, that the hand of Beaumont cannot clearly be distinguished from that of Fletcher.” Yet this romantic notion did not stand up to critical examination. In the seventeenth century, Sir Aston Cockayne, a friend of Fletcher’s, specified that there were many plays in the 1647 Beaumont and Fletcher folio that contained nothing of Beaumont’s work, but rather featured the writing of Philip Massinger. Nineteenth– and twentieth-century critics like E. H. C. Oliphant subjected the plays to a self-consciously literary, and often subjective and impressionistic, reading—but nonetheless began to differentiate the hands of the collaborators. This study was carried much farther, and onto a more objective footing, by twentieth-century scholars, especially Cyrus Hoy. Short of absolute certainty, a critical consensus has evolved on many plays in the canon of Fletcher and his collaborators; in regard to Beaumont, the schema below is among the least controversial that has been drawn. By Beaumont alone: The Knight of the Burning Pestle, comedy (performed 1607; printed 1613) The Masque of the Inner Temple and Gray’s Inn, masque (performed 20 February 1613; printed 1613?) With Fletcher: The Woman Hater, comedy (1606; 1607) Cupid’s Revenge, tragedy (c. 1607–12; 1615) Philaster, or Love Lies a-Bleeding, tragicomedy (c. 1609; 1620) The Maid’s Tragedy, tragedy (c. 1609; 1619) A King and No King, tragicomedy (1611; 1619) The Captain, comedy (c. 1609–12; 1647) The Scornful Lady, comedy (ca. 1613; 1616) Love’s Pilgrimage, tragicomedy (c. 1615–16; 1647) The Noble Gentleman, comedy (licensed 3 February 1626; 1647) Beaumont/Fletcher plays, later revised by Massinger: Thierry and Theodoret, tragedy (c. 1607?; 1621) The Coxcomb, comedy (c. 1608–10; 1647) Beggars’ Bush, comedy (c. 1612–13?; revised 1622?; 1647) Love’s Cure, comedy (c. 1612–13?; revised 1625?; 1647) Because of Fletcher’s highly distinctive and personal pattern of linguistic preferences and contractional forms (ye for you, 'em for them, etc.), his hand can be distinguished fairly easily from Beaumont’s in their collaborations. In A King and No King, for example, Beaumont wrote all of Acts I, II, and III, plus scenes IV.iv and V.ii and iv; Fletcher wrote only the first three scenes in Act IV (IV, i-iii) and the first and third scenes in Act V (V, i and iii)—so that the play is more Beaumont’s than Fletcher’s. The same is true of The Woman Hater, The Maid’s Tragedy, The Noble Gentleman, and Philaster. On the other hand, Cupid’s Revenge, The Coxcomb, The Scornful Lady, Beggar’s Bush, and The Captain are more Fletcher’s than Beaumont’s. In Love’s Cure and Thierry and Theodoret, the influence of Massinger’s revision complicates matters; but in those plays too, Fletcher appears to be the majority contributor, Beaumont the minority. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Beaumont

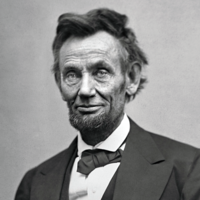

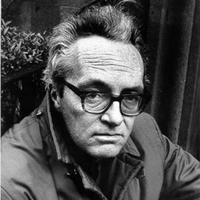

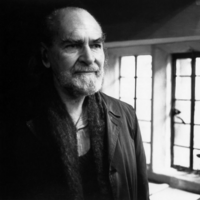

Mark Strand (April 11, 1934– November 29, 2014) was a Canadian-born American poet, essayist and translator. He was appointed Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress in 1990 and received the Wallace Stevens Award in 2004. Strand was a professor of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University from 2005 until his death in 2014. Biography Strand was born in 1934 at Summerside, Prince Edward Island, Canada. Raised in a secular Jewish family, he spent his early years in North America and much of his adolescence in South and Central America. Strand graduated from Oakwood Friends School in 1951 and in 1957 earned his B.A. from Antioch College in Ohio. He then studied painting under Josef Albers at Yale University, where he earned a B.F.A in 1959. On a U.S.-Italy Fulbright Commission scholarship, Strand studied 19th-century Italian poetry in Florence in 1960–61. He attended the Iowa Writers’ Workshop at the University of Iowa the following year and earned a Master of Arts in 1962. In 1965 he spent a year in Brazil as a Fulbright Lecturer. In 1981, Strand was elected a member of The American Academy of Arts and Letters. He served as Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress during the 1990–91 term. In 1997, he left Johns Hopkins University to accept the Andrew MacLeish Distinguished Service Professorship of Social Thought at the Committee on Social Thought at the University of Chicago. From 2005 to his death, Strand taught literature and creative writing at Columbia University, in New York City. Strand received numerous awards, including a MacArthur Fellowship in 1987 and the 1999 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry, for Blizzard of One. Strand died of liposarcoma on November 29, 2014, in Brooklyn, New York. Poetry Many of Strand’s poems are nostalgic in tone, evoking the bays, fields, boats, and pines of his Prince Edward Island childhood. Strand has been compared to Robert Bly in his use of surrealism, though he attributes the surreal elements in his poems to an admiration of the works of Max Ernst, Giorgio de Chirico, and René Magritte. Strand’s poems use plain and concrete language, usually without rhyme or meter. In a 1971 interview, Strand said, “I feel very much a part of a new international style that has a lot to do with plainness of diction, a certain reliance on surrealist techniques, and a strong narrative element.” Academic career Strand’s academic career took him to various colleges and universities, including: Teaching positions University of Iowa, Iowa City, instructor in English, 1962–1965 University of Brazil, Rio de Janeiro, Fulbright lecturer, 1965–1966 Mount Holyoke College, South Hadley, MA, assistant professor, 1967 Columbia University, New York City, adjunct associate professor, 1969–1972 Brooklyn College of the City University of New York, New York City, associate professor, 1970–1972 Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, Bain-Swiggett Lecturer, 1973 Brandeis University, Hurst professor of poetry, 1974–1975 University of Utah, Salt Lake City, professor of English, 1981–1993 Johns Hopkins University, Elliot Coleman Professor of Poetry, 1994–c. 1998 University of Chicago, Committee on Social Thought, 1998– ca. 2005 Columbia University, New York City, professor of English and Comparative Literature, ca. 2005–2014 Visiting professor University of Washington, 1968, 1970 Columbia University, 1980 Yale University, 1969–1970 University of Virginia, 1976, 1978 California State University at Fresno, 1977 University of California at Irvine, 1979 Wesleyan University, 1979 Harvard University, 1980 Awards * Strand has been awarded the following: * 1960–1961: Fulbright Fellowship * 1979: Fellowship of the Academy of American Poets * 1987: MacArthur Fellowship * 1990–1991: Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress * 1992: Bobbitt National Prize for Poetry * 1993: Bollingen Prize * 1999: Pulitzer Prize, for Blizzard of One * 2004: Wallace Stevens Award * 2009: Gold Medal in Poetry, from the American Academy of Arts and Letters Bibliography References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mark_Strand

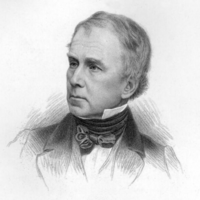

Charles Churchill (February, 1732– 4 November 1764), was an English poet and satirist. Early life Churchill was born in Vine Street, Westminster. His father, rector of Rainham, Essex, held the curacy and lectureship of St Johns, Westminster, from 1733, and Charles was educated at Westminster School, where he became a good classical scholar, and formed a close and lasting friendship with Robert Lloyd. He was admitted to St John’s College, Cambridge on 8 July 1748. Churchill contracted a marriage within the rules of the Fleet in his eighteenth year, and never lived at Cambridge; the young couple lived in his father’s house, and Churchill was afterwards sent to the north of England to prepare for holy orders. He became curate of South Cadbury, Somerset, and, on receiving priest’s orders (1756), began to act as his father’s curate at Rainham. Two years later the elder Churchill died, and the son was elected to succeed him in his curacy and lectureship. His emoluments amounted to less than £100 a year, and he increased his income by teaching in a girls’ school. His marriage proved unhappy, and he began to spend much of his time in dissipation in the society of Robert Lloyd. He was separated from his wife in 1761, and would have been imprisoned for debt but for the timely help of Lloyd’s father, who had been an usher and was now a master at Westminster. Career as Satirist Churchill had already done some work for the booksellers, and his friend Lloyd had had some success with a didactic poem, The Actor. Churchill’s knowledge of the theatre was now made use of in the Rosciad, which appeared in March 1761. This reckless and amusing satire described with the most disconcerting accuracy the faults of the various actors and actresses on the London stage; in a competition judged by Shakespeare and Jonson, Garrick is named the greatest English actor. Its immediate popularity was no doubt largely due to its personal character, but its vigour and raciness make it worth reading even now when the objects of Churchill’s wit are forgotten. The first impression was published anonymously, and in the Critical Review, conducted by Tobias Smollett, it was confidently asserted that the poem was the joint production of George Colman the Elder, Bonnell Thornton and Robert Lloyd. Churchill immediately published an Apology addressed to the Critical Reviewers, which, after developing the subject that it is only authors who prey on their own kind, repeats the fierce attack on the stage. Incidentally it contains an enthusiastic tribute to John Dryden, of whom Churchill was a devotee. In the Rosciad he had praised Mrs Pritchard, Mrs Cibber and Mrs Clive, but no leading London actor, with the exception of David Garrick, had escaped censure, and in the Apology Garrick was clearly threatened. He deprecated criticism by showing every possible civility to Churchill, who became a terror to the actors. Thomas Davies wrote to Garrick attributing his blundering in the part of Cymbeline “to my accidentally seeing Mr Churchill in the pit, it rendering me confused and unmindful of my business.” Churchill’s satire made him many enemies, and brought reprisals. In Night, an Epistle to Robert Lloyd (1761), he answered the attacks made on him, offering by way of defense the argument that any faults were better than hypocrisy. His scandalous conduct brought down the censure of the dean of Westminster, and in 1763 the protests of his parishioners led him to resign his offices, and he was free to wear his blue coat with metal buttons and much gold lace without remonstrance from the dean. The Rosciad had been refused by several publishers, and was finally published at Churchill’s own expense. He received a considerable sum from the sale, and paid his old creditors in full, besides making an allowance to his wife. Friendship with Wilkes He now became a close ally of John Wilkes, whom he regularly assisted with The North Briton weekly newspaper. His next poem, The Prophecy of Famine: A Scots Pastoral (1763), was founded on a paper written originally for that newspaper. This violent satire on Scottish influence fell in with the current hatred of Lord Bute, and the Scottish place-hunters were as much alarmed as the actors had been. When Wilkes was arrested he gave Churchill a timely hint to retire to the country for a time, the publisher, Kearsley, having stated that he received part of the profits from the paper. His Epistle to William Hogarth (1763) was in answer to the caricature of Wilkes made during the trial, in it Hogarth’s vanity and envy were attacked in an invective which Garrick quoted as shocking and barbarous. Hogarth retaliated by a caricature of Churchill as a bear in torn clerical bands hugging a pot of porter and a club made of lies and North Britons. The Duellist (1763) is a virulent satire on the most active opponents of Wilkes in the House of Lords, especially on Bishop Warburton. He attacked Dr Johnson among others in The Ghost as “Pomposo, insolent and loud, Vain idol of a scribbling crowd”. Other poems are The Conference (1763); The Author (1763), highly praised by Churchill’s contemporaries; Gotham (1764), a poem on the duties of a king, didactic rather than satiric in tone; The Candidate (1764), a satire on John Montagu, fourth earl of Sandwich, one of Wilkes’s bitterest enemies, whom he had already denounced for his treachery in The Duellist (Bk. iii.) as too infamous to have a friend; The Farewell (1764); The Times (1764); Independence, and an unfinished Journey. Death and Legacy In October 1764 he went to Boulogne to join Wilkes. There he was attacked by a fever of which he died on 4 November. He left his property to his two sons, and made Wilkes his literary executor with full powers. Wilkes did little. He wrote an epitaph for his friend and about half a dozen notes on his poems, and Andrew Kippis acknowledges some slight assistance from him in preparing his life of Churchill for the Biographia (1780). There is more than one instance of Churchill’s generosity to his friends. In 1763 he found his friend Robert Lloyd in prison for debt. He paid a guinea a week for his better maintenance in the Fleet, and raised a subscription to set him free. Lloyd fell ill on receipt of the news of Churchill’s death, and died shortly afterwards. Churchill’s sister Patty, who was engaged to Lloyd, did not long survive them. William Cowper was his schoolfellow, and left many kindly references to him. A partial collection of Churchill’s poems appeared in 1763. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Churchill_(satirist)

William Cosmo Monkhouse (18 March 1840– 20 July 1901) was an English poet and critic. He was born in London. His father, Cyril John Monkhouse, was a solicitor; his mother’s maiden name was Delafosse. He was educated at St Paul’s School, quitting it at seventeen to enter the board of trade as a junior supplementary clerk, from which grade he rose eventually to be the assistant-secretary to the finance department of the office. In 1870–71 he visited South America in connection with the hospital accommodation for seamen at Valparaíso, Chile, and other ports; and he served on different departmental committees, notably that of 1894–96 on the Mercantile Marine Fund. He was twice married: first, to Laura, daughter of James Keymer of Dartford; and, secondly, to Leonora Eliza, daughter of Commander Blount, R.N.

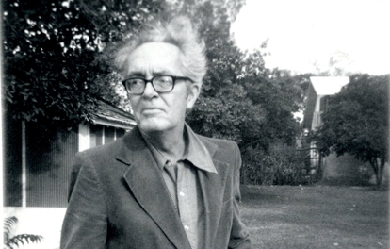

Stanley Jasspon Kunitz (July 29, 1905 – May 14, 2006) was an American poet. He was appointed Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress twice, first in 1974 and then again in 2000. Biography Kunitz was born in Worcester, Massachusetts, the youngest of three children, to Yetta Helen (née Jasspon) and Solomon Z. Kunitz, both of Jewish Russian Lithuanian descent.His father, a dressmaker of Russian Jewish heritage, committed suicide in a public park six weeks before Stanley was born. After going bankrupt, he went to Elm Park in Worcester, and drank carbolic acid. His mother removed every trace of Kunitz’s father from the household. The death of his father would be a powerful influence of his life.Kunitz and his two older sisters, Sarah and Sophia, were raised by his mother, who had made her way from Yashwen, Kovno, Lithuania by herself in 1890, and opened a dry goods store. Yetta remarried to Mark Dine in 1912. Yetta and Mark filed for bankruptcy in 1912 and then were indicted by the U.S. District Court for concealing assets. They pleaded guilty and turned over USD$10,500 to the trustees. Mark Dine died when Kunitz was fourteen, when, while hanging curtains, he suffered a heart attack.At fifteen, Kunitz moved out of the house and became a butcher’s assistant. Later he got a job as a cub reporter on The Worcester Telegram, where he would continue working during his summer vacations from college.Kunitz graduated summa cum laude in 1926 from Harvard College with an English major and a philosophy minor, and then earned a master’s degree in English from Harvard the following year. He wanted to continue his studies for a doctorate degree, but was told by the university that the Anglo-Saxon students would not like to be taught by a Jew.After Harvard, he worked as a reporter for The Worcester Telegram, and as editor for the H. W. Wilson Company in New York City. He then founded and edited Wilson Library Bulletin and started the Author Biographical Studies. Kunitz married Helen Pearce in 1930; they divorced in 1937. In 1935 he moved to New Hope, Pennsylvania and befriended Theodore Roethke. He married Eleanor Evans in 1939; they had a daughter Gretchen in 1950. Kunitz divorced Eleanor in 1958.At Wilson Company, Kunitz served as co-editor for Twentieth Century Authors, among other reference works. In 1931, as Dilly Tante, he edited Living Authors, a Book of Biographies. His poems began to appear in Poetry, Commonweal, The New Republic, The Nation, and The Dial. During World War II, he was drafted into the Army in 1943 as a conscientious objector, and after undergoing basic training three times, served as a noncombatant at Gravely Point, Washington in the Air Transport Command in charge of information and education. He refused a commission and was discharged with the rank of staff sergeant.After the war, he began a peripatetic teaching career at Bennington College (1946–1949; taking over from his friend Roethke). He subsequently taught at the State University of New York at Potsdam (then the New York State Teachers College at Potsdam) as a full professor (1949-1950; summer sessions through 1954), the New School for Social Research (lecturer; 1950-1957), the University of Washington (visiting professor; 1955-1956), Queens College (visiting professor; 1956-1957), Brandeis University (poet-in-residence; 1958-1959) and Columbia University (lecturer in the School of General Studies; 1963-1966) before spending 18 years as an adjunct professor of writing at Columbia’s School of the Arts (1967-1985). Throughout this period, he also held visiting appointments at Yale University (1970), Rutgers University–Camden (1974), Princeton University (1978) and Vassar College (1981).After his divorce from Eleanor, he married the painter and poet Elise Asher in 1958. His marriage to Asher led to friendships with artists like Philip Guston and Mark Rothko.Kunitz’s poetry won wide praise for its profundity and quality. He was the New York State Poet Laureate from 1987 to 1989. He continued to write and publish until his centenary year, as late as 2005. Many consider that his poetry’s symbolism is influenced significantly by the work of Carl Jung. Kunitz influenced many 20th-century poets, including James Wright, Mark Doty, Louise Glück, Joan Hutton Landis, and Carolyn Kizer. For most of his life, Kunitz divided his time between New York City and Provincetown, Massachusetts. He enjoyed gardening and maintained one of the most impressive seaside gardens in Provincetown. There he also founded Fine Arts Work Center, where he was a mainstay of the literary community, as he was of Poets House in Manhattan. He was awarded the Peace Abbey Courage of Conscience award in Sherborn, Massachusetts in October 1998 for his contribution to the liberation of the human spirit through his poetry.He died in 2006 at his home in Manhattan. He had previously come close to death, and reflected on the experience in his last book, a collection of essays, The Wild Braid: A Poet Reflects on a Century in the Garden. Poetry Kunitz’s first collection of poems, Intellectual Things, was published in 1930. His second volume of poems, Passport to the War, was published fourteen years later; the book went largely unnoticed, although it featured some of Kunitz’s best-known poems, and soon fell out of print. Kunitz’s confidence was not in the best of shape when, in 1959, he had trouble finding a publisher for his third book, Selected Poems: 1928-1958. Despite this unflattering experience, the book, eventually published by Little Brown, received the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry. His next volume of poems would not appear until 1971, but Kunitz remained busy through the 1960s editing reference books and translating Russian poets. When twelve years later The Testing Tree appeared, Kunitz’s style was radically transformed from the highly intellectual and philosophical musings of his earlier work to more deeply personal yet disciplined narratives; moreover, his lines shifted from iambic pentameter to a freer prosody based on instinct and breath—usually resulting in shorter stressed lines of three or four beats. Throughout the 70s and 80s, he became one of the most treasured and distinctive voices in American poetry. His collection Passing Through: The Later Poems won the National Book Award for Poetry in 1995. Kunitz received many other honors, including a National Medal of Arts, the Bollingen Prize for a lifetime achievement in poetry, the Robert Frost Medal, and Harvard’s Centennial Medal. He served two terms as Consultant on Poetry for the Library of Congress (the precursor title to Poet Laureate), one term as Poet Laureate of the United States, and one term as the State Poet of New York. He founded the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, Massachusetts, and Poets House in New York City. Kunitz also acted as a judge for the Yale Series of Younger Poets Competition. Library Bill of Rights Kunitz served as editor of the Wilson Library Bulletin from 1928 to 1943. An outspoken critic of censorship, in his capacity as editor, he targeted his criticism at librarians who did not actively oppose it. He published an article in 1938 by Bernard Berelson entitled “The Myth of Library Impartiality”. This article led Forrest Spaulding and the Des Moines Public Library to draft the Library Bill of Rights, which was later adopted by the American Library Association and continues to serve as the cornerstone document on intellectual freedom in libraries. Awards and honors * 2006 L.L. Winship/PEN New England Award, The Wild Braid: A Poet Reflects on a Century in the Garden Bibliography * * Poetry * The Wild Braid: A Poet Reflects on a Century in the Garden (2005) * The Collected Poems of Stanley Kunitz (NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000) * Passing Through, The Later Poems, New and Selected (NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 1995)—winner of the National Book Award * Next-to-Last Things: New Poems and Essays (1985) * The Wellfleet Whale and Companion Poems * The Terrible Threshold * The Coat without a Seam * The Poems of Stanley Kunitz (1928–1978) (1978) * The Testing-Tree (1971) * Selected Poems, 1928-1958 (1958) * Passport to the War (1944) * Intellectual Things (1930)Other writing and interviews: * Conversations with Stanley Kunitz (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, Literary Conversations Series, 11/2013), Edited by Kent P. Ljungquist * A Kind of Order, A Kind of Folly: Essays and Conversations’ * Interviews and Encounters with Stanley Kunitz (Riverdale-on-Hudson, NY: The Sheep Meadow Press, 1995), Edited by Stanley MossAs editor, translator, or co-translator: * The Essential Blake * Orchard Lamps by Ivan Drach * Story under full sail by Andrei Voznesensky * Poems of John Keats * Poems of Akhmatova by Max Hayward References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stanley_Kunitz

Charles Stuart Calverley (/ˈkɑːvərlɪ/; 22 December 1831– 17 February 1884) was an English poet and wit. He was the literary father of what has been called “the university school of humour”. Early life He was born at Martley, Worcestershire, and given the name Charles Stuart Blayds. In 1852, his father, the Rev. Henry Blayds, resumed the old family name of Calverley, which his grandfather had exchanged for Blayds in 1807. Charles went up to Balliol College, Oxford from Harrow School in 1850, and was soon known in Oxford as the most daring and high-spirited undergraduate of his time. He was a universal favourite, a delightful companion, a brilliant scholar and the playful enemy of all “dons.” In 1851 he won the Chancellor’s prize for Latin verse, but it is said that the entire exercise was written in an afternoon, when his friends had locked him into his rooms, refusing to let him out until he had finished what they were confident would prove the prize poem. A year later, to avoid the consequences of a college escapade (he had been expelled from Oxford), he too changed his name to Calverley and moved to Christ’s College, Cambridge. Here he was again successful in Latin verse, the only undergraduate to have won the Chancellor’s prize at both universities. In 1856 he took second place in the first class in the Classical Tripos. Later life He was elected fellow of Christ’s (1858), published Verses and Translations in 1862, and was called to the bar in 1865. Injuries sustained in a skating accident prevented him from following a professional career, and during the last years of his life he was an invalid. He died of Bright’s disease. Works * Nowadays he is best-known (at least in Cambridge, his adoptive home) as the author of the Ode to Tobacco which is to be found on a bronze plaque in Rose crescent, on the wall of what used to be Bacon’s the tobacconist. * His Translations into English and Latin appeared in 1866; his Theocritus translated into English Verse in 1869; Fly Leaves in 1872; and Literary Remains in 1885. * His Complete Works, with a biographical notice by Walter Joseph Sendall, a contemporary at Christ’s and his brother-in-law, appeared in 1901. * George W. E. Russell said of him: * He was a true poet; he was one of the most graceful scholars that Cambridge ever produced; and all his exuberant fun was based on a broad and strong foundation of Greek, Latin, and English literature. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Stuart_Calverley