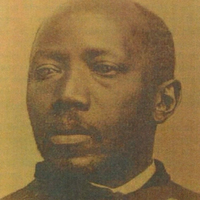

George Moses Horton (1798–1884) was an African-American poet and the first African American poet to be published in the Southern United States. His book was published in 1828 while he was still enslaved; he remained enslaved until he was emancipated late in the Civil War. Biography Horton was born into slavery on William Horton’s plantation in Northampton County, North Carolina. He was the sixth of ten children, though the names of his parents are lost to history. As a very young child in 1800, he and several family members were moved to a tobacco farm in rural Chatham County, when his owner relocated. He was given as property to William’s relative James Horton in 1814. In 1819, the estate was broken up, and George Moses Horton’s family was separated (the poem “Division of an Estate” reflected on the experience years later). Horton disliked farm work and in his free time he taught himself to read using spelling books, the Bible, and hymnals. Learning poetry and snippets of literature, Horton composed poems in his mind. As a young adult, Horton delivered produce to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where he composed and recited poems for students, some of whom transcribed his compositions. Horton also composed poems, usually love poems, by commission for the students at 25 or 50 cents each. Considering the difficulty of earning income from poetry, Horton was likely one of the few professional poets in the South at the time. In 1829, his poems were published in a collection titled The Hope of Liberty, which was intended to raise funds for his release from slavery. The book, funded by the politically-liberal journalist Joseph Gales, appeared the same year as David Walker’s An Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World. Horton is believed to be the first Southern black to publish poetry. Though he knew how to read, he published the book before he learned how to write. As he recalled, “I fell to work in my head, and composed several undigested pieces.” By 1832, he had learned to write for himself, having learned with the aid of Caroline Lee Hentz, who was the wife of a professor and a writer herself. She also assisted in publishing at least two of his poems in a newspaper. Horton had composed a poem on the death of Hentz’s child. As he recalled: “She was extremely pleased with the dirge which I wrote on the death of her much lamented primogenial infant, and for which she gave me much credit and a handsome reward. Not being able to write myself, I dictated while she wrote.” She sent one of Horton’s poems to her hometown newspaper in Lancaster, Massachusetts, where it was published on April 8, 1828, as “Liberty and Slavery”. Horton’s first book was republished under the title Poems by a Slave in 1837 and compiled with a biography and poetry by Phillis Wheatley a year later in a book called Memoir and Poems of Phillis Wheatley, a Native African and Slave: Also Poems by a Slave. The book was published by Boston-based publisher and abolitionist Isaac Knapp, and it is believed to be the first complete collection of Wheatley’s poems in book form. In 1845, Horton released another book of poetry, The Poetical Works of George M. Horton, The Colored Bard of North-Carolina, To Which Is Prefixed The Life of the Author, Written by Himself. The moniker, “Colored Bard of North-Carolina”, was coined by his new publisher. Horton gained the admiration of North Carolina Governor John Owen, influential newspapermen Horace Greeley and William Lloyd Garrison, along with numerous Northern abolitionists. Sometime in the 1830s, Horton married an enslaved woman owned by Franklin Snipes in Chatham County. The couple had two children, Free and Rhody, though little else is known about the family. Horton had written about his interest in the new nation of Liberia, and a few of the abolitionist papers made calls to raise enough money so that Horton could see his dream of life in Liberia come true. He was not emancipated until 1865, however, when he met the Ninth Cavalry from Michigan. A young officer with that group, William H. S. Banks, collaborated with Horton on the collection Naked Genius the same year. At the age of 68, Horton moved to Pennsylvania as a freeman where he continued to write poetry for local newspapers. One such publication, “Forbidden to Ride on the Street Cars”, shows his disappointment in the unjust treatment of blacks even after emancipation. In Philadelphia, he wrote Sunday school stories on behalf of friends who lived in the city. His exact death location and date are unknown. At least one researcher suggests Horton moved to Liberia at some point. Poetry After Horton’s first poem was published in the Lancaster, Massachusetts Gazette, his works appeared in other newspapers like the Register in Raleigh, North Carolina, and the Freedom’s Journal in New York City. Horton’s poetic style was typical of contemporary European poetry and was similar to poems written by free white contemporaries, likely a reflection of his reading and his work for commission. He wrote both sonnets and ballads, and his earlier works focused on his life in servitude. Such topics, however, were more generalized and not necessarily based on his personal experience. Nevertheless, he referred to his life on “vile accursed earth” and the “drudg’ry, pain, and toil” of life, as well as his oppression “because my skin is black”. His first collection was focused heavily on the issue of slavery and bondage. Likely because sales from that book were not enough for him to purchase his freedom, his second book mentions slavery only twice. The change in theme is also likely due to the more restrictive climate in the South in the years leading up to the Civil War. His later works, especially those made after his emancipation, were more rural and pastoral. Like other early black American writers like Jupiter Hammon and Phillis Wheatley, Horton was also heavily influenced by the Bible. The earliest known critical commentary on Horton’s writing is from 1909 by UNC professor Collier Cobb, who dismissed Horton’s antislavery themes: “George never really cared for more liberty than he had, but was fond of playing to the grandstand.”. Legacy Winston-Salem, North Carolina opened the George Moses Horton Branch Library in 1927 in a YWCA building. The George Moses Horton Society for the Study of African American Poetry was founded in 1996, the same year he was inducted into the North Carolina Literary Hall of Fame. The next year, 1997, he was named Historic Poet Laureate of Chatham County, North Carolina. In 2006, UNC Chapel Hill named a dormitory for George Moses Horton; it was formerly called Hinton James North and is believed to be the first university dormitory in the country to be named for a slave. In 2015 author/illustrator Don Tate published Poet: The Remarkable Story of George Moses Horton, an illustrated biography of Horton for children. The Wilson Library at UNC hosted the national launch of the book on September 3, 2015. Published works The Hope of Liberty (1829) Poems by a Slave (1837) The Poetical Works of George M. Horton (1845) Naked Genius (1865, with William H. S. Banks) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Moses_Horton

A young British writer who dabbles in the creative arts every now and then. I'm currently studying English Literature and Language at the University of Nottingham and am always struck by inspiration at the oddest times! Give the poems a read and get from them what you will; they're their own entities now, I can't control them any more

Thomas Hood (23 May 1799– 3 May 1845) was an English poet, author and humourist, best known for poems such as “The Bridge of Sighs” and “The Song of the Shirt”. Hood wrote regularly for The London Magazine, the Athenaeum, and Punch. He later published a magazine largely consisting of his own works. Hood, never robust, lapsed into invalidism by the age of 41 and died at the age of 45. William Michael Rossetti in 1903 called him “the finest English poet” between the generations of Shelley and Tennyson. Hood was the father of playwright and humourist Tom Hood (1835–1874).

Charles Harpur (23 January 1813– 10 June 1868) was an Australian poet. He was born on 23 January 1813 at Windsor, New South Wales, the third child of Joseph Harpur—originally from Kinsale, County Cork, Ireland, parish clerk and master of the Windsor district school—and Sarah, née Chidley (from Somerset; both had been transported.) Harpur received his elementary education in Windsor. This was probably largely supplemented by private study; he was an eager reader of William Shakespeare. Harpur followed various avocations in the bush and for some years in his twenties held a clerical position at the post office in Sydney.

I was born in Alabama. Lived the first 9 years of my life in Florida, but then moved back to Alabama after my grandmother passed away to live in her house. I've been here ever since and I absolutely love it. I am married to a wonderful man who is my best friend. I'm surrounded by my family and friends and beautiful nature. I am a follower of Christ. I've always loved to write. When I was little, I would write my parents little notes and slide them underneath the door of whatever room they were in. I just loved to touch people through my words. Verbally and on paper. When I became a teenager, I started to write random poetry for fun, but also for school. I realized that it wasn't homework for me to write, it was a joy. My poetry streak really took off at the age of 15. Now, having recently turned 30, I have been through a lot in the past decade and have not written as much as i used to. Ups and downs, highs and lows, defeats and victories...you name it. I've felt a lot of different emotions and thought many thoughts. And I've composed quite a few poems and written many songs through it all. So, this is my place to share them with the world, to touch others through my words. I hope they mean something to you. Thank you.

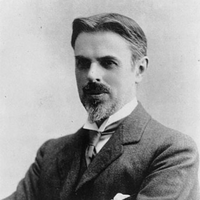

Marguerite Radclyffe Hall (12 August 1880– 7 October 1943) was an English poet and author. She is best known for the novel The Well of Loneliness, a groundbreaking work in lesbian literature. Life Marguerite Radclyffe Hall was born in 1880 at “Sunny Lawn”, Durley Road, Bournemouth, Hampshire (now Dorset), to a wealthy philandering father, Radclyffe Radclyffe-Hall, and an unstable mother, Mary Jane Diehl. Her stepfather was the professor of singing Albert Visetti, whom she did not like and who had a tempestuous relationship with her mother. Hall was a lesbian and described herself as a “congenital invert”, a term taken from the writings of Havelock Ellis and other turn-of-the-century sexologists. Having reached adulthood without a vocation, she spent much of her twenties pursuing women she eventually lost to marriage. In 1907 at the Bad Homburg spa in Germany, Hall met Mabel Batten, a well-known amateur singer of lieder. Batten (nicknamed “Ladye”) was 51 to Hall’s 27, and was married with an adult daughter and grandchildren. They fell in love, and after Batten’s husband died they set up residence together. Batten gave Hall the nickname John, which she used the rest of her life. In 1915 Hall fell in love with Mabel Batten’s cousin Una Troubridge (1887–1963), a sculptor who was the wife of Vice-Admiral Ernest Troubridge, and the mother of a young daughter. Batten died the following year, and in 1917 Radclyffe Hall and Una Troubridge began living together. From 1924 to 1929 they lived at 37 Holland Street, Kensington, London. The relationship would last until Hall’s death. In 1934 Hall fell in love with Russian émigrée Evguenia Souline and embarked upon a long-term affair with her, which Troubridge painfully tolerated. She became involved in affairs with other women throughout the years. Later years and death Hall lived with Troubridge in London and, during the 1930s, in the tiny town of Rye, East Sussex, noted for its many writers, including her contemporary the novelist E. F. Benson. Hall died at age 63 of colon cancer, and is interred at Highgate Cemetery in North London at the entrance of the chamber of the Batten family, where Mabel is buried as well. In 1930, Hall received the Gold Medal of the Eichelbergher Humane Award. She was a member of the PEN club, the Council of the Society for Psychical Research and a fellow of the Zoological Society. Radclyffe Hall was listed at number sixteen in the top 500 lesbian and gay heroes in The Pink Paper. Novels Hall’s first novel was The Unlit Lamp, the story of Joan Ogden, a young girl who dreams of setting up a flat in London with her friend Elizabeth (a so-called Boston marriage) and studying to become a doctor, but feels trapped by her manipulative mother’s emotional dependence on her. Its length and grimness made it a difficult book to sell, so she deliberately chose a lighter theme for her next novel, a social comedy entitled The Forge. While she had used her full name for her early poetry collections, she shortened it to M. Radclyffe Hall for The Forge. The book was a modest success, making the bestseller list of John O’London’s Weekly. The Unlit Lamp, which followed it into print, was the first of her books to give the author’s name simply as Radclyffe Hall. There followed another comic novel, A Saturday Life (1925), and then Adam’s Breed (1926), a novel about an Italian headwaiter who, becoming disgusted with his job and even with food itself, gives away his belongings and lives as a hermit in the forest. The book’s mystical themes have been compared to Hermann Hesse’s Siddhartha. It sold well, was critically acclaimed, and won both the Prix Femina and the James Tait Black Prize, a feat previously achieved only by E. M. Forster’s A Passage to India. The Well of Loneliness Hall’s best-known work was The Well of Loneliness, the only one of her eight novels to have overt lesbian themes. Published in 1928, The Well of Loneliness deals with the life of Stephen Gordon, a masculine lesbian who, like Hall herself, identifies as an “invert”. Although The Well of Loneliness is not sexually explicit, it was nevertheless the subject of an obscenity trial in the UK, which resulted in all copies of the novel being ordered destroyed. The United States allowed its publication only after a long court battle. It is currently published in the UK by Virago, and by Anchor Press in the United States. The Well of Loneliness was number seven on a list of the top 100 lesbian and gay novels compiled by The Publishing Triangle in 1999. Later novels An anonymous verse lampoon entitled The Sink of Solitude appeared during the controversy over The Well. Although its primary targets were James Douglas, who had called for The Well’s suppression, and the Home Secretary William Joynson-Hicks, who had started legal proceedings, it also mocked Hall and her book. One of the illustrations, which depicted Hall nailed to a cross, so horrified her that she could barely speak of it for years afterward. Her sense of guilt at being depicted in a drawing that she saw as blasphemous led to her choice of a religious subject for her next novel, The Master of the House. At Hall’s insistence, The Master of the House was published with no cover blurb, which may have misled some purchasers into thinking it was another novel about “inversion”. Advance sales were strong, and the book made No. 1 on The Observer’s bestseller list, but it received poor reviews in several key periodicals, and sales soon dropped off. In the United States reviewers treated the book more kindly, but shortly after the book’s publication, all copies were seized—not by the police, but by creditors. Hall’s American publisher had gone bankrupt. Houghton Mifflin took over the rights, but by the time the book could be republished, its sales momentum was lost. The Girls of Radcliff Hall The British composer and bon-vivant Gerald Tyrwhitt-Wilson, 14th Baron Berners, wrote a roman à clef girls’ school story entitled The Girls of Radcliff Hall, in which he depicts himself and his circle of friends, including Cecil Beaton and Oliver Messel, as lesbian schoolgirls at a school named “Radcliff Hall”. The novel was written under the pseudonym “Adela Quebec” and published and distributed privately; the indiscretions to which it alluded created an uproar among Berners’s intimates and acquaintances, making the whole affair highly discussed in the 1930s. Cecil Beaton attempted to have all the copies destroyed. The novel subsequently disappeared from circulation, making it extremely rare. The story is, however, included in Berners’ Collected Tales and Fantasies. Works Novels * The Forge (1924) * The Unlit Lamp (1924) * A Saturday Life (1925) * Adam's Breed (1926) * The Well of Loneliness (1928) * The Master of the House (1932) * Miss Ogilvy Finds Herself (1926) * The Sixth Beatitude (William Heineman Ltd, London, 1936) Poetry * Dedicated to Sir Arthur Sullivan (England: s.n., 1894) * Twixt Earth and Stars (London: John and Edward Bumpus Ltd., 1906) * A Sheaf of Verses : Poems (London: J. and E. Bumpus, 1908) * Poems of the Past & Present (London: Chapman And Hall, 1910) * Songs of Three Counties and Other Poems (London: Chapman & Hall, 1913) * The Forgotten Island (London: Chapman & Hall, 1915) * Rhymes and Rhythms (Milan, 1948) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Radclyffe_Hall

Humble as can be was never the guy to realy have or be givin alot so many daily struggles. writing allittle bit helps me cope i feel like i have some sort of talent.My lines may not mean alot but mabey some can relate. I feel as if everyone has an imagination thats been blocked off but theres always a way to break out and understand the talent whe all have. so much potential in all people they key is to bring it out because god made us with gifts so why cant we use them taldent comes from the heart break out of that box.

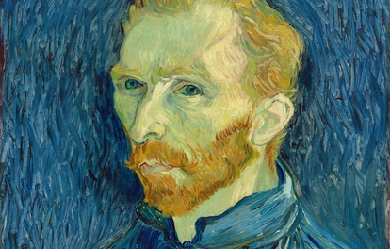

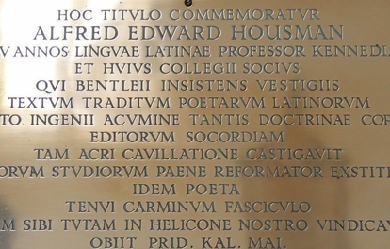

Alfred Edward Housman was born in Fockbury, Worcestershire, England, on March 26, 1859, the eldest of seven children. A year after his birth, Housman’s family moved to nearby Bromsgrove, where the poet grew up and had his early education. In 1877, he attended St. John’s College, Oxford and received first class honours in classical moderations. Housman became distracted, however, when he fell in love with his heterosexual roommate Moses Jackson. He unexpectedly failed his final exams, but managed to pass the final year and later took a position as clerk in the Patent Office in London for ten years. During this time he studied Greek and Roman classics intensively, and in 1892 was appointed professor of Latin at University College, London. In 1911 he became professor of Latin at Trinity College, Cambridge, a post he held until his death. As a classicist, Housman gained renown for his editions of the Roman poets Juvenal, Lucan, and Manilius, as well as his meticulous and intelligent commentaries and his disdain for the unscholarly. Housman only published two volumes of poetry during his life: A Shropshire Lad (1896) and Last Poems (1922). The majority of the poems in A Shropshire Lad, his cycle of 63 poems, were written after the death of Adalbert Jackson, Housman’s friend and companion, in 1892. These poems center around themes of pastoral beauty, unrequited love, fleeting youth, grief, death, and the patriotism of the common soldier. After the manuscript had been turned down by several publishers, Housman decided to publish it at his own expense, much to the surprise of his colleagues and students. While A Shropshire Lad was slow to gain in popularity, the advent of war, first in the Boer War and then in World War I, gave the book widespread appeal due to its nostalgic depiction of brave English soldiers. Several composers created musical settings for Housman’s work, deepening his popularity. Housman continued to focus on his teaching, but in the early 1920s, when his old friend Moses Jackson was dying, Housman chose to assemble his best unpublished poems so that Jackson might read them. These later poems, most of them written before 1910, exhibit a range of subject and form much greater than the talents displayed in A Shropshire Lad. When Last Poems was published in 1922, it was an immediate success. A third volume, More Poems, was released posthumously in 1936 by his brother, Laurence, as was an edition of Housman’s Complete Poems (1939). Despite acclaim as a scholar and a poet in his lifetime, Housman lived as a recluse, rejecting honors and avoiding the public eye. He died on April 30, 1936, in Cambridge. References Poets.org—https://www.poets.org/poetsorg/poet/e-housman

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (September 24, 1825– February 22, 1911) was an African-American abolitionist, suffragist, poet and author. She was also active in other types of social reform and was a member of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, which advocated the federal government taking a role in progressive reform. Born free in Baltimore, Maryland, she had a long and prolific career, publishing her first book of poetry at age 20 and her widely praised Iola Leroy, at age 67. In 1850, she became the first woman to teach sewing at the Union Seminary. In 1851, alongside William Still, chairman of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, she helped escaped slaves along the Underground Railroad on their way to Canada. She began her career as a public speaker and political activist after joining the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1853. Poems on Miscellaneous Subjects (1854) became her biggest commercial success. Her short story “Two Offers” was published in the Anglo-African in 1859. She published Sketches of Southern Life in 1872. It detailed her experience touring the South and meeting newly freed Black people. In these poems she described the harsh living conditions of many. After the Civil War she continued to fight for the rights of women, African Americans, and many other social causes. She helped or held high office in several national progressive organizations. In 1873 Harper became superintendent of the Colored Section of the Philadelphia and Pennsylvania Women’s Christian Temperance Union. In 1894 she helped found the National Association of Colored Women and served as its vice president. Harper died February 22, 1911, nine years before women gained the right to vote. Her funeral service was held at the Unitarian Church on Chestnut Street in Philadelphia. She was buried in Eden Cemetery, next to her daughter, who had died two years before. Life and Works Early Life and Education Frances Ellen Watkins was born to free parents in Baltimore, Maryland. After her mother died when she was three years old in 1828, Watkins was orphaned. She was raised by her maternal aunt and uncle, Rev. William Watkins, who was a civil rights activist. She was educated at his Academy for Negro Youth. Watkins was a major influence on her life and work. At fourteen, Frances found work as a seamstress. Writing career Frances Watkins had her first volume of verse, Forest Leaves, published in 1845 when she was 20. Her second book, Poems on Miscellaneous Subjects (1854), was extremely popular. Over the next few years, it was reprinted numerous times. In 1859, her story “The Two Offers” was published in Anglo-African Magazine, making her the first Black woman to publish a short story. She continued to publish poetry and short stories. She had three novels serialized in a Christian magazine from 1868 to 1888, but was better known for what was long considered her first novel, Iola Leroy, or Shadows Uplifted (1892), published as a book when she was 67. At one time considered the first novel by an African American, it is one of the earliest. (Discoveries of earlier works by Harriet E. Wilson and William Wells Brown have displaced Harper’s work.) While using the conventions of the time, she dealt with serious social issues, including education for women, passing, miscegenation, abolition, reconstruction, temperance, and social responsibility. Teaching and Public Activism In 1850, Watkins moved to Ohio, where she worked as the first female teacher at Union Seminary, established by the Ohio Conference of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. (Union closed in 1863 when the AME Church diverted its funds to purchase Wilberforce University, the first black-owned and operated college.) The school in Wilberforce was run by the Rev. John Mifflin Brown, later a bishop in the AME Church. In 1853, Watkins joined the American Anti-Slavery Society and became a traveling lecturer for the group. In 1854, Watkins delivered her first anti-slavery speech on “Education and the Elevation of Colored Race”. The success of this speech resulted in a two-year lecture tour in Maine for the Anti-Slavery Society. She continued to travel, lecturing throughout the East and Midwest from 1856 to 1860. Progressive Causes Frances Watkins Harper was a strong supporter of abolitionism, prohibition and woman’s suffrage, progressive causes which were connected before and after the American Civil War.. She was also active in the Unitarian Church, which supported abolitionism. An example of her support of the abolition cause, Harper wrote to John Brown (abolitionist), “I thank you that you have been brave enough to reach out your hands to the crushed and blighted of my race; I hope from your sad fate great good may arise to the cause of freedom.” She often read her poetry at the public meetings, including the extremely popular “Bury Me in a Free Land.” In 1858 She refused to give up her seat or ride in the “colored” section of a segregated trolley car in Philadelphia (100 years before Rosa Parks) and wrote one of her most famous poems, “Bury Me In A Free Land,” when she got very sick while on a lecturing tour. Her short story “The Two Offers” became the first short story to be published by a Black woman. In 1866, Harper gave a moving speech before the National Women’s Rights Convention, demanding equal rights for all, including Black women. During the Reconstruction Era, she worked in the South to review and report on living conditions of freedmen. This experience inspired her poems published in Sketches Of Southern Life (1872). She uses the figure of an ex-slave, called Aunt Chloe, as a narrator in several of these. Harper was active in the growing number of Black organizations and came to believe that Black reformers had to be able to set their own priorities. From 1883 to 1890, she helped organize events and programs for the National Woman’s Christian Temperance Union. She had worked with members of the original WCTU, because “it was the most important women’s organization to push for expanding federal power.” “Activists like Harper and Willard campaigned not only for racial and sexual equality but also for a new understanding of the federal government’s responsibility to protect rights, regulate morality, and promote social welfare”. Harper was disappointed when Willard gave priority to white women’s concerns, rather than support Black women’s goals of gaining federal support for an anti-lynching law, defense of black rights, or abolition of the convict lease system. Together with Mary Church Terrell, Harper helped organize the National Association of Colored Women in 1894, and was elected vice president in 1897. Frances Harper died on February 22, 1911.

Lived a life of different struggles and probably still will experience some more in my life. At the same time have conquered some great battles in life. Now going through a new journey and wondering where its going to lead . Now I feel like I need to share my words just as a release and also to get feed back. Writing is something I enjoy and now I will see how it does out in the public. P.S. Just so those who read my poems they are what I call just words to me so they may seem raw. I just type them up like I wrote them Have a good one and thank you for reading.

George Herbert (3 April 1593 – 1 March 1633) was a Welsh poet, orator and Anglican priest. Herbert’s poetry is associated with the writings of the metaphysical poets, and he is recognized as “a pivotal figure: enormously popular, deeply and broadly influential, and arguably the most skilful and important British devotional lyricist.” Born into an artistic and wealthy family, Herbert received a good education that led to his admission in 1609 as a student at Trinity College, Cambridge, where Herbert excelled in languages, rhetoric and music. He went to university with the intention of becoming a priest, but when eventually he became the University’s Public Orator he attracted the attention of King James I and may well have seen himself as a future Secretary of State. In 1624 and briefly in 1625 he served in the Parliament of England. After the death of King James, Herbert’s interest in ordained ministry was renewed. In his mid-thirties he gave up his secular ambitions and took holy orders in the Church of England, spending the rest of his life as the rector of the little parish of St Andrews Church, Lower Bemerton, Salisbury. He was noted for unfailing care for his parishioners, bringing the sacraments to them when they were ill, and providing food and clothing for those in need. Henry Vaughan called him “a most glorious saint and seer”. Never a healthy man, he died of consumption at the early age of 39. Throughout his life, he wrote religious poems characterized by a precision of language, a metrical versatility, and an ingenious use of imagery or conceits that was favoured by the metaphysical school of poets. Charles Cotton described him as a “soul composed of harmonies”. Some of Herbert’s poems have endured as popular hymns, including “King of Glory, King of Peace” (Praise): “Let All the World in Every Corner Sing” (Antiphon) and “Teach me, my God and King” (The Elixir). Herbert’s first biographer, Izaak Walton, wrote that he composed “such hymns and anthems as he and the angels now sing in heaven”. Biography Early life and education George Herbert was born 3 April 1593 in Montgomery, Powys, Wales, the son of Richard Herbert (died 1596) and his wife Magdalen née Newport, the daughter of Sir Richard Newport (1511–70). He was one of 10 children. The Herbert family was wealthy and powerful in both national and local government, and George was descended from the same stock as the Earls of Pembroke. His father was a Member of Parliament, a justice of the peace, and later served for several years as high sheriff and later custos rotulorum (keeper of the rolls) of Montgomeryshire. His mother Magdalen was a patron and friend of clergyman and poet John Donne and other poets, writers and artists. As George’s godfather, Donne stood in after Richard Herbert died when George was three years old. Herbert and his siblings were then raised by his mother who helped push for a good education for her children. Herbert’s eldest brother Edward (who inherited his late father’s estates and was ultimately created Baron Herbert of Cherbury) became a soldier, diplomat, historian, poet, and philosopher whose religious writings led to his reputation as the “father of English deism”. Herbert entered Westminster School at or around the age of 12 as a day pupil, although later he became a residential scholar. He was admitted on scholarship to Trinity College, Cambridge in 1609, and graduated first with a Bachelor’s and then with a master’s degree in 1616 at the age of 23. Subsequently, Herbert was elected a major fellow of his college and then appointed Reader in Rhetoric. In 1620 he stressed his fluency in Latin and Greek and attained election to the post of the University’s Public Orator, a position he held until 1628. In 1624, supported by his kinsman the 3rd Earl of Pembroke, Herbert became a Member of Parliament, representing Montgomery. While these positions normally presaged a career at court, and King James I had shown him favour, circumstances worked against Herbert: the King died in 1625, and two influential patrons also died at about the same time. However, his parliamentary career may have ended already because, although a Mr Herbert is mentioned as a committee member, the Commons Journal for 1625 never mentions Mr. George Herbert, despite the preceding parliament’s careful distinction. In short, Herbert made a shift in his path, he angled away from the political future he had been pursuing and turned more fully toward a future in the church. Herbert was presented with the Prebendary of Leighton Bromswold in the Diocese of Lincoln in 1626, whilst he was still a don at Trinity College, Cambridge but not yet ordained. He was not even present at his institution as prebend as it is recorded that Peter Walker, his clerk, stood in as his proxy. In the same year his close Cambridge friend Nicholas Ferrar was ordained Deacon in Westminster Abbey by Bishop Laud on Trinity Sunday 1626 and went to Little Gidding, two miles down the road from Leighton Bromswold, to found the remarkable community with which his name has ever since been associated. Herbert raised money (including the use of his own) to restore the neglected church building at Leighton. Priesthood In 1629, Herbert decided to enter the priesthood and was appointed rector of the small rural parish of Fugglestone St Peter with Bemerton, near Salisbury in Wiltshire, about 75 miles south west of London. Here he lived, preached and wrote poetry; he also helped to rebuild the Bemerton church and rectory out of his own funds. While at Bemerton, Herbert revised and added to his collection of poems entitled The Temple. He also wrote a guide to rural ministry entitled A Priest to the Temple or, The County Parson His Character and Rule of Holy Life, which he himself described as “a Mark to aim at”, and which has remained influential to this day. Having married shortly before taking up his post, he and his wife gave a home to three orphaned nieces. Together with their servants, they crossed the lane for services in the small St Andrew’s church twice every day. Twice a week Herbert made the short journey into Salisbury to attend services at the Cathedral, and afterwards would make music with the cathedral musicians. But his time at Bemerton was short. Having suffered for most of his life from poor health, in 1633 Herbert died of consumption only three years after taking holy orders. Shortly before his death, he sent the manuscript of The Temple to Nicholas Ferrar, the founder of a semi-monastic Anglican religious community at Little Gidding, reportedly telling him to publish the poems if he thought they might “turn to the advantage of any dejected poor soul”, otherwise to burn them. Thanks to Ferrar, they were published not long after his death. Poetry Herbert wrote poetry in English, Latin and Greek. In 1633 all of Herbert’s English poems were published in The Temple: Sacred Poems and Private Ejaculations, with a preface by Nicholas Ferrar. The book went through eight editions by 1690. According to Isaac Walton, when Herbert sent the manuscript to Ferrar, he said that “he shall find in it a picture of the many spiritual conflicts that have passed between God and my soul, before I could subject mine to the will of Jesus, my Master”. In this Herbert used the format of the poems to reinforce the theme he was trying to portray. Beginning with “The Church Porch”, they proceed via “The Altar” to “The Sacrifice”, and so onwards through the collection. All of Herbert’s surviving English poems are on religious themes and are characterised by directness of expression enlivened by original but apt conceits in which, in the Metaphysical manner, the likeness is of function rather than visual. In “The Windows”, for example, he compares a righteous preacher to glass through which God’s light shines more effectively than in his words. Commenting on his religious poetry later in the 17th century, Richard Baxter said, “Herbert speaks to God like one that really believeth in God, and whose business in the world is most with God. Heart-work and heaven-work make up his books”. Helen Gardner later added “head-work” to this characterisation in acknowledgement of his “intellectual vivacity”. It has also been pointed out how Herbert uses puns and wordplay to “convey the relationships between the world of daily reality and the world of transcendent reality that gives it meaning. The kind of word that functions on two or more planes is his device for making his poem an expression of that relationship.” Visually too the poems are varied in such a way as to enhance their meaning, with intricate rhyme schemes, stanzas combining different line lengths and other ingenious formal devices. The most obvious examples are pattern poems like “The Altar,” in which the shorter and longer lines are arranged on the page in the shape of an altar. The visual appeal is reinforced by the conceit of its construction from a broken, stony heart, representing the personal offering of himself as a sacrifice upon it. Built into this is an allusion to Psalm 51:17: “The sacrifices of God are a broken spirit; a broken and a contrite heart.” In the case of “Easter Wings” (illustrated here), the words were printed sideways on two facing pages so that the lines there suggest outspread wings. The words of the poem are paralleled between stanzas and mimic the opening and closing of the wings. In Herbert’s poems formal ingenuity is not an end in itself but is employed only as an auxiliary to its meaning. The formal devices employed to convey that meaning are wide in range. In his meditation on the passage “Our life is hid with Christ in God”, the capitalised words ‘My life is hid in him that is my treasure’ move across successive lines and demonstrate what is spoken of in the text. Opposites are brought together in “Bitter-Sweet” for the same purpose. Echo and variation are also common. The exclamations at the head and foot of each stanza in “Sighs and Grones” are one example. The diminishing truncated rhymes in “Paradise” are another. There is also an echo-dialogue after each line in “Heaven”, other examples of which are found in the poetry of his brother Lord Herbert of Cherbury. Alternative rhymes are offered at the end of the stanzas in “The Water-Course”, while the "Mary/Army Anagram" is represented in its title. Once the taste for this display of Baroque wit had passed, the satirist John Dryden was to dismiss it as so many means to “torture one poor word ten thousand ways”. Though Herbert remained esteemed for his piety, the poetic skill with which he expressed his thought had to wait centuries to be admired again. Prose Herbert’s only prose work, A Priest to the Temple (usually known as The Country Parson), offers practical advice to rural clergy. In it, he advises that “things of ordinary use” such as ploughs, leaven, or dances, could be made to “serve for lights even of Heavenly Truths”. It was first published in 1652 as part of Herbert’s Remains, or Sundry Pieces of That Sweet Singer, Mr. George Herbert, edited by Barnabas Oley. The first edition was prefixed with unsigned preface by Oley, which was used as one of the sources for Izaak Walton’s biography of Herbert, first published in 1670. The second edition appeared in 1671 as A Priest to the Temple or the Country Parson, with a new preface, this time signed by Oley. Like many of his literary contemporaries, Herbert was a collector of proverbs. His Outlandish Proverbs was published in 1640, listing over 1000 aphorisms in English, but gathered from many countries (in Herbert’s day, 'outlandish’ meant foreign). The collection included many sayings repeated to this day, for example, “His bark is worse than his bite” and “Who is so deaf, as he that will not hear?” These and an additional 150 proverbs were included in a later collection entitled Jacula Prudentum (sometimes seen as Jacula Prudentium), dated 1651 and published in 1652 as part of Oley’s Herbert’s Remains. Musical settings Herbert was a skilled lutenist who “sett his own lyricks or sacred poems”. Musical pursuits interested him all though his life and his biographer, Isaac Walton, records that he rose to play the lute during his final illness. With such fitness for music in mind, it is no surprise to find that more than ninety of his poems have been set for singing over the centuries, some of them multiple times. Beginning in his own century, there were settings of “Longing” by Henry Purcell and “And art thou grieved” by John Blow. Some forty were adapted for the Methodist hymnal by the Wesley brothers, among them “Teach me my God and King”, which found its place in one version or another in 223 hymnals. Another poem, “Let all the world in every corner sing”, was published in 103 hymnals, of which one is a French version. Other languages into which his work has been translated for musical settings include Spanish, Catalan and German. In the 20th century, “Vertue” alone achieved ten settings, one of them in French. Among leading modern musicians who set his work were Ralph Vaughan-Williams, who used four by Herbert in "5 Mystical Songs"; Benjamin Britten and William Walton, both of whom set "Antiphon 2"; Ned Rorem who included one in his "10 poems for voice, oboe and strings" (1982); and Judith Weir, whose 2005 choral work Vertue includes three poems by Herbert. Legacy The earliest portrait of George Herbert was engraved long after his death by Robert White for Walton’s biography of the poet in 1674 (see above). Now in London’s National Portrait Gallery, it served as basis for later engravings, such as those by White’s apprentice John Sturt and Henry Hoppner Meyer’s of 1829. Among later artistic commemorations is William Dyce’s oil painting of “George Herbert at Bemerton” (1860) in the Guildhall Art Gallery. The poet is pictured in his riverside garden, prayer book in hand. Over the meadows is Salisbury Cathedral, where he used to join in the musical evensong; his lute leans against a stone bench and against a tree a fishing rod is propped, a reminder of his first biographer, Isaac Walton. There is also a musical reference in Charles West Cope’s “George Herbert and his mother” (1872) in Gallery Oldham. The mother points a poem out to him with an arm twined round his neck in a room that has a virginal in the background. Most representations of Herbert, however, are in stained glass windows, of which there are several in churches and cathedrals. They include Westminster Abbey, Salisbury Cathedral and All Saints Church, Cambridge. His own St Andrew’s Church in Bemerton installed a memorial window, which he shares with Nicholas Ferrar, in 1934. In addition, there is a statue of Herbert in his canonical robes, based in part on the Robert White portrait, in a niche on the West Front of Salisbury Cathedral. In the liturgy too George Herbert is commemorated on 27 February throughout the Anglican Communion and on 1 March of the Calendar of Saints of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. There are various collects for the day, of which one is based on his poem “The Elixir”: Our God and King, who called your servant George Herbert from the pursuit of worldly honors to be a pastor of souls, a poet, and a priest in your temple: Give us grace, we pray, joyfully to perform the tasks you give us to do, knowing that nothing is menial or common that is done for your sake... Amen. Works * 1623: Oratio Qua auspicatissimum Serenissimi Principis Caroli. * 1627: Memoriae Matris Sacrum, printed with A Sermon of commemoracion of the ladye Danvers by John Donne... with other Commemoracions of her by George Herbert (London: Philemon Stephens and Christopher Meredith). * 1633: The Temple, Sacred Poems and Private Ejaculations. (Cambridge: Printed by Thomas Buck and Roger Daniel). * 1652: Herbert’s Remains, Or, Sundry Pieces Of that sweet Singer of the Temple consisting of his collected writings from A Priest to the Temple, Jacula Prudentum, Sentences, & c., as well as a letter, several prayers, and three Latin poems.(London: Printed for Timothy Garthwait) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Herbert

James Henry Leigh Hunt (19 October 1784– 28 August 1859), best known as Leigh Hunt, was an English critic, essayist, poet, and writer. Biography Early life James Henry Leigh Hunt was born at Southgate, London, where his parents had settled after leaving the United States. His father Isaac, a lawyer from Philadelphia, and his mother, Mary Shewell, a merchant’s daughter and a devout Quaker, had been forced to come to Britain because of their loyalist sympathies during the American War of Independence. Hunt’s father took holy orders and became a popular preacher, but he was unsuccessful in obtaining a permanent living. Hunt’s father was then employed by James Brydges, 3rd Duke of Chandos, as tutor to his nephew, James Henry Leigh (father of Chandos Leigh), after whom the boy was named. Education Leigh Hunt was educated at Christ’s Hospital from 1791 to 1799, a period which is detailed in his autobiography. He entered the school shortly after Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Charles Lamb had both left; Thomas Barnes, however, was a school friend of his. One of the current boarding houses at Christ’s Hospital is named after him. As a boy, he was an ardent admirer of Thomas Gray and William Collins, writing many verses in imitation of them. A speech impediment, later cured, prevented his going to university. “For some time after I left school,” he says, “I did nothing but visit my school-fellows, haunt the book-stalls and write verses.” His poems were published in 1801 under the title of Juvenilia, and introduced him into literary and theatrical society. He began to write for the newspapers, and published in 1807 a volume of theatre criticism, and a series of Classic Tales with critical essays on the authors. Hunt’s early essays were published by Edward Quin, editor and owner of The Traveller. Family In 1809, Leigh Hunt married Marianne Kent (whose parents were Thomas and Ann). Over the next 20 years they had ten children: Thornton Leigh (1810–73), John Horatio Leigh (1812–46), Mary Florimel Leigh (1813–49), Swinburne Percy Leigh (1816–27), Percy Bysshe Shelley Leigh (1817–99), Henry Sylvan Leigh (1819–76), Vincent Leigh (1823–52), Julia Trelawney Leigh (1826–72), Jacyntha Leigh (1828–1914), and Arabella Leigh (1829–30). Marianne, who had been in ill health for most of her life, died 26 January 1857, aged sixty-nine. Leigh Hunt made little mention of his family in his autobiography. Marianne’s sister, Elizabeth Kent (Hunt’s sister-in-law), became his amanuensis. Newspapers The Examiner In 1808 he left the War Office, where he had been working as a clerk, to become editor of the Examiner, a newspaper founded by his brother, John. His brother Robert Hunt, among others, also contributed to its columns; his criticism earned the enmity of William Blake, who described the journal’s office at Beaufort Buildings, Strand, London, as containing a “nest of villains”. Blake’s response included Leigh Hunt, who aside from publishing the vitriolic reviews of 1808 and 1809 had added Blake’s name on a list of “quacks”. This journal soon acquired a reputation for unusual political independence; it would attack any worthy target, “from a principle of taste,” as John Keats expressed it. In 1813, an attack on the Prince Regent, based on substantial truth, resulted in prosecution and a sentence of two years’ imprisonment for each of the brothers—Leigh Hunt served his term at the Surrey County Gaol. Leigh Hunt’s visitors in prison included Lord Byron, Thomas Moore, Lord Brougham, Charles Lamb and others, whose acquaintance influenced his later career. The stoicism with which Leigh Hunt bore his imprisonment attracted general attention and sympathy. His imprisonment allowed him many luxuries and access to friends and family, and Lamb described his decorations of the cell as something not found outside a fairy tale. When Jeremy Bentham called on him, he was found playing battledore. A number of essays in The Examiner that were written by Hunt and William Hazlitt between 1814 and 1817 under the series title “The Round Table” were collected in book form in The Round Table, published in two volumes in 1817. Twelve of the fifty-two essays were by Hunt, the rest by Hazlitt. The Reflector In 1810–1811 he edited a quarterly magazine, the Reflector, for his brother John. He wrote “The Feast of the Poets” for this, a satire, which offended many contemporary poets, particularly William Gifford of the Quarterly. The Indicator In 1819–1821, Hunt edited The Indicator, a weekly literary periodical published by Joseph Appleyard. Hunt probably wrote much of the content as well, which included reviews, essays, stories, and poems. Poetry In 1816 he made a mark in English literature with the publication of Story of Rimini, based on the tragic episode of Francesca da Rimini told in Dante’s Inferno. Hunt’s preference was decidedly for Chaucer’s verse style, as adapted to modern English by John Dryden, in opposition to the epigrammatic couplet of Alexander Pope which had superseded it. The poem is an optimistic narrative which runs contrary to the tragic nature of its subject. Hunt’s flippancy and familiarity, often degenerating into the ludicrous, subsequently made him a target for ridicule and parody. In 1818 appeared a collection of poems entitled Foliage, followed in 1819 by Hero and Leander, and Bacchus and Ariadne. In the same year he reprinted these two works with The Story of Rimini and The Descent of Liberty with the title of Poetical Works, and started the Indicator, in which some of his best work appeared. Both Keats and Shelley belonged to the circle gathered around him at Hampstead, which also included William Hazlitt, Charles Lamb, Bryan Procter, Benjamin Haydon, Charles Cowden Clarke, C.W. Dilke, Walter Coulson and John Hamilton Reynolds. This group was known as the Hunt Circle, or, pejoratively, as the Cockney School. Some of Hunt’s most popular poems are “Jenny kiss’d Me”, “Abou Ben Adhem” and “A Night-Rain in Summer”. Friendship with Keats and Shelley He had for some years been married to Marianne Kent. His own affairs were in confusion, and only Percy Bysshe Shelley’s generosity saved him from ruin. In return he showed sympathy to Shelley during the latter’s domestic distresses, and defended him in the Examiner. He introduced Keats to Shelley and wrote a very generous appreciation of him in the Indicator. Keats seems, however, to have subsequently felt that Hunt’s example as a poet had been in some respects detrimental to him. After Shelley’s departure for Italy in 1818, Leigh Hunt became even poorer, and the prospects of political reform less satisfactory. Both his health and that of his wife failed, and he was obliged to discontinue the Indicator (1819–1821), having, he says, “almost died over the last numbers.” Shelley suggested that Hunt go to Italy with him and Byron to establish a quarterly magazine in which Liberal opinions could be advocated with more freedom than was possible at home. An injudicious suggestion, it would have done little for Hunt or the Liberal cause at the best, and depended entirely upon the co-operation of the capricious, parsimonious Byron. Byron’s principal motive for agreeing appears to have been the expectation of acquiring influence over the Examiner, and he was mortified to discover that Hunt was no longer interested in the Examiner. Leigh Hunt left England for Italy in November 1821, but storm, sickness and misadventure retarded his arrival until 1 July 1822, a rate of progress which Thomas Love Peacock appropriately compares to the navigation of Ulysses. The death of Shelley, a few weeks later, destroyed every prospect of success for the Liberal. Hunt was now virtually dependent upon Byron, who did not relish the idea of being patron to Hunt’s large and troublesome family. Byron’s friends also scorned Hunt. The Liberal lived through four quarterly numbers, containing contributions no less memorable than Byron’s “Vision of Judgment” and Shelley’s translations from Faust; but in 1823 Byron sailed for Greece, leaving Hunt at Genoa to shift for himself. The Italian climate and manners, however, were entirely to Hunt’s taste, and he protracted his residence until 1825, producing in the interim Ultra-Crepidarius: a Satire on William Gifford (1823), and his translation (1825) of Francesco Redi’s Bacco in Toscana. In 1825 a litigation with his brother brought him back to England, and in 1828 he published Lord Byron and some of his Contemporaries, a corrective to idealized portraits of Byron. The public was shocked that Hunt, who had been obliged to Byron for so much, would “bite the hand that fed him” in this way. Hunt especially writhed under the withering satire of Moore. For many years afterwards, the history of Hunt’s life is a painful struggle with poverty and sickness. He worked unremittingly, but one effort failed after another. Two journalistic ventures, the Tatler (1830–1832), a daily devoted to literary and dramatic criticism, and Leigh Hunt’s London Journal (1834–1835), were discontinued for want of subscribers, although the latter contained some of his best writing. His editorship (1837–1838) of the Monthly Repository, in which he succeeded William Johnson Fox, was also unsuccessful. The adventitious circumstances which allowed the Examiner to succeed no longer existed, and Hunt’s personality was unsuited to the general body of readers. In 1832 a collected edition of his poems was published by subscription, the list of subscribers including many of his opponents. In the same year was printed for private circulation Christianism, the work afterwards published (1853) as The Religion of the Heart. A copy sent to Thomas Carlyle secured his friendship, and Hunt went to live next door to him in Cheyne Row in 1833. Sir Ralph Esher, a romance of Charles II’s period, had a success, and Captain Sword and Captain Pen (1835), a spirited contrast between the victories of peace and the victories of war, deserves to be ranked among his best poems. In 1840 his circumstances were improved by the successful representation at Covent Garden of his play Legend of Florence. Lover’s Amazements, a comedy, was acted several years afterwards, and was printed in Leigh Hunt’s Journal (1850–1851); other plays remained in manuscript. In 1840 he wrote introductory notices to the work of Sheridan and to Edward Moxon’s edition of the works of William Wycherley, William Congreve, John Vanbrugh and George Farquhar, a work which furnished the occasion of Macaulay’s essay on the Dramatists of the Restoration. The narrative poem The Palfrey was published in 1842. More financial difficulties The time of Hunt’s greatest difficulties was between 1834 and 1840. He was at times in absolute poverty, and his distress was aggravated by domestic complications. By Macaulay’s recommendation he began to write for the Edinburgh Review. In 1844 Mary Shelley and her son, on succeeding to the family estates, settled an annuity of £120 upon Hunt (Rossetti 1890); and in 1847 Lord John Russell procured him a pension of £200. Now living in improved comfort, Hunt published the companion books, Imagination and Fancy (1844), and Wit and Humour (1846), two volumes of selections from the English poets, which displayed his refined, discriminating critical tastes. His book on the pastoral poetry of Sicily, A Jar of Honey from Mount Hybla (1848), is also delightful. The Town (2 vols., 1848) and Men, Women and Books (2 vols., 1847) are partly made up from former material. The Old Court Suburb (2 vols., 1855; ed. A Dobson, 2002) is a sketch of Kensington, where he long resided. In 1850 he published his Autobiography (3 vols.), a naive and affected, but accurate, piece of self-portraiture. A Book for a Corner (2 vols.) was published in 1849, and his Table Talk appeared in 1851. In 1855 his narrative poems, original and translated, were collected under the title Stories in Verse. He died in Putney on 28 August 1859, and is buried at Kensal Green Cemetery. In September 1966 Christ’s Hospital named one of its Houses in memory of him. Leigh Hunt was the original of Harold Skimpole in Bleak House. "Dickens wrote in a letter of 25 September 1853, 'I suppose he is the most exact portrait that was ever painted in words!... It is an absolute reproduction of a real man’; and a contemporary critic commented, 'I recognized Skimpole instantaneously;... and so did every person whom I talked with about it who had ever had Leigh Hunt’s acquaintance.'" G. K. Chesterton suggested that Dickens “may never once have had the unfriendly thought, ‘Suppose Hunt behaved like a rascal!’; he may have only had the fanciful thought, ‘Suppose a rascal behaved like Hunt!’” (Chesterton 1906). Other works Amyntas, A Tale of the Woods (1820), a translation of Tasso’s Aminta Flora Domestica, Or, The Portable Flower-garden: with Directions for the Treatment of Plants in Pots and Illustrations From the Works of the Poets. London: Taylor and Hessey. 1823., with Elizabeth Kent, published anonymously The Seer, or Common-Places refreshed (2 pts., 1840–1841) three of the Canterbury Tales in The Poems of Geoffrey Chaucer modernized (1841) Stories from the Italian Poets (1846) compilations such as One Hundred Romances of Real Life (1843) selections from Beaumont and Fletcher (1855) with S Adams Lee, The Book of the Sonnet (Boston, 1867). His Poetical Works (2 vols.), revised by himself and edited by Lee, were printed at Boston in 1857, and an edition (London and New York) by his son, Thornton Hunt, appeared in 1860. Among volumes of selections are Essays (1887), ed. A Symons; Leigh Hunt as Poet and Essayist (1889), ed. C Kent; Essays and Poems (1891), ed. RB Johnson for the “Temple Library.” His Autobiography was revised shortly before his death, and edited (1859) by his son Thornton Hunt, who also arranged his Correspondence (2 vols., 1862). Additional letters were printed by the Cowden Clarkes in their Recollections of Writers (1878). The Autobiography was edited (2 vols., 1903) with full bibliographical note by Roger Ingpen. A bibliography of his works was compiled by Alexander Ireland (List of the Writings of William Hazlitt and Leigh Hunt, 1868). There are short lives of Hunt by Cosmo Monkhouse ("Great Writers," 1893) and by RB Johnson (1896). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Volume 28 (2004). References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leigh_Hunt

Poetry is an escape. I have never been very good at expressing myself verbally, but with a pen it's so easy. I use poetry as an outlet; it keeps me sane. I believe a lot is wrong with the world. And though I can't do much about it I try an use my poems to open people's eyes to what is happening around them. My style may seem amateur but it is how I choose to write. Poetry is my passion. And I'd like to share my work with as many people as I can because the only way they'll even have a chance at understanding me is through the words I put down on paper.

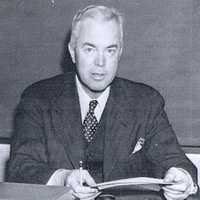

Robert Silliman Hillyer (June 3, 1895– December 24, 1961) was an American poet. Life Hillyer was born in East Orange, New Jersey. He attended Kent School in Kent, Connecticut, and graduated from Harvard in 1917, after which he went to France and volunteered with the S.S.U. 60 of the Norton-Harjes Ambulance Corps serving the Allied Forces in World War I. He had long links to Harvard University, including holding a position as a Professor of English. From 1948 to 1951 Hillyer was a visiting professor at Kenyon College and from there went to serve on the faculty at the University of Delaware. While teaching at Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut in the late 1920s, Hillyer was made a member of the Epsilon chapter of the prestigious St. Anthony Hall Delta Psi literary fraternity in 1927. His work is in meter and often rhyme. He is known for his sonnets and for such poems as “Theme and Variations” (on his war experiences) and the light “Letter to Robert Frost”. American composer Ned Rorem’s most famous art song is a setting of Hillyer’s “Early in the Morning”. Hillyer is remembered as a kind of villain by Ezra Pound scholars, who associate him with his 1949 attacks on The Pisan Cantos in the Saturday Review of Literature which sparked the Bollingen Controversy. Hillyer was identified with the Harvard Aesthetes grouping. He was 66 when he died in Wilmington, Delaware. Awards * Pulitzer Prize for Poetry for “Collected Verse” in 1934. Works Poetry * The Collected Poems. Knopf. 1961. * The relic & other poems. Knopf. 1957. * The suburb by the sea: new poems. Knopf. 1952. * The death of Captain Nemo: a narrative poem. A.A. Knopf. 1949. * Poems for music, 1917–1947. A. A. Knopf. 1947. * The Collected Verse of Robert Hillyer. A.A. Knopf. 1933. * The Coming Forth by Day: An Anthology of Poems from the Egyptian Book of the Dead. B.J. Brimmer Company. 1923. * Hillyer, Robert (1920). Alchemy: A Symphonic Poem. Illustrator Beatrice Stevens. Kessinger Publishing, LLC. * Hillyer, Robert (1920). The Five Books of Youth. Brentano’s. * Hillyer, Robert (1917). Sonnets and Other Lyrics. Harvard University Press. * Hillyer, Robert (1917). The Wise Old Apple Tree in the Spring. Harvard University Press. Novels * Riverhead (1932) Criticism * In Pursuit of Poetry. McGraw-Hill. 1960. * First Principles of Verse. The Writer. 1950. Translations * Oluf Friis (1922). A Book of Danish Verse: Translated in the Original Meters. Translators Samuel Foster Damon, Robert Hillyer. The American-Scandinavian Foundation. Editors * Kahlil Gibran (1959). Hayim Musa Nahmad, Robert Hillyer, ed. A Tear and a Smile. A. A. Knopf. * Samuel Foster Damon, Robert Hillyer, ed. (1923). Eight More Harvard Poets. Brentano’s. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Hillyer

My life is one big blur of broken and lost love by the one I loved the most for the shortest period of time and I'm spending the rest of my life distracting myself of my brokenness and forever waiting for my dearest. > On top of that I come from a long past of death,mourning and despair. My gone father, my hero, a fallen soldier. My brother, never got to see the essence of this world, lost his breath at birth in the hospital. My mother, cheated on, beaten on, went head to head against death, passed through jail cells, but you will always see her with a smile, that's my guardian angel, the only thing/one/person I have left. ~ That is all you need to know about me.

John Hartley (1839-1915) was an English poet who worked in the Yorkshire dialect. He wrote a great deal of prose and poetry – often of a sentimental nature – dealing with the poverty of the district. He was born in Halifax, West Yorkshire. Hartly wrote and edited the Original Illuminated Clock Almanack from 1866 to his death. Most of Hartley’s works are written in dialect. Hartley wrote a number of books featuring the character “Sammywell Grimes”, who has a number of adventures and suffers unfortunate mishaps. Works * Yorkshire Ditties, First Series * Yorkshire Ditties, Second Series * Yorkshire Tales, First Series * Yorkshire Tales, Second Series * Yorkshire Tales, Third Series * Yorkshire Lyrics (1898) * Pensive Poems and Startling Stories * A Rolling Stone. A Tale of Wrongs and Revenge * Mally An’ Me: A selection of Humorous and Pathetic Incidents from the Life of Sammywell Grimes and His Wife Mally (1902) * Yorksher Puddin (1876) * A Sheaf from the Moorland– A Collection of Original Poems * Grimes’ Visit To Th’ Queen. A Royal Time Amang Royalties * Seets I’Lundun: A Yorkshireman’s Ten Days’ Trip * Seets i’ Yorkshire and Lancashire or Grimes’ Comical Trip from Leeds to Liverpool by Canal * Seets i’ Blackpool– Grimes at the Seaside * Seets i’ Paris– Sammywell Grimes’s trip with his old chum Billy Baccus; his opinion o’th’ French, and th’ French opinion o’th’ exhibition he made ov hissen. * Grimes’ Trip to America– Ten letters from Sammywell to John Jones Smith * Sammywell Grimes An’ his Wife Mally Laikin I’ Lakeland: A Humorous Account of their Visit to the Home of Famous Poets, &c., &c. External links * Works by John Hartley at Project Gutenberg * Works by or about John Hartley at Internet Archive * Works by John Hartley at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks) * Yorkshire Ditties by John Hartley– Link fails 25 October 2008– permissions * John Hartley at Old Poetry References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Hartley_(poet)

Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961) was one of the most significant American authors of the Twentieth century . His novels and short fictions have left an indelible mark on the literary production of the United States and the world. Although most often remembered for his economical and understated fiction, he was also a noted journalist. In 1954, Ernest Hemingway was awarded the Novel Prize in Literature. Hemingway is also known for his heroic, adventurous and often stereotypically “manly” public persona. The myth he cultivated of himself as a man of action aided the important Modernist reading of many of his works.

Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, KG (1516/1517– 19 January 1547), was an English aristocrat, and one of the founders of English Renaissance poetry. He was a first cousin of both Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard, the second and fifth wives of King Henry VIII. Life He was the eldest son of Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, and his second wife, the former Lady Elizabeth Stafford (daughter of Edward Stafford, 3rd Duke of Buckingham), so he was descended from kings on both sides of his family tree: King Edward I on his father’s side and King Edward III on his mother’s side. He was reared at Windsor with Henry VIII’s illegitimate son Henry FitzRoy, 1st Duke of Richmond and Somerset, and they became close friends and, later, brothers-in-law upon the marriage of Surrey’s sister to Fitzroy. Like his father and grandfather, he was a brave and able soldier, serving in Henry VIII’s French wars as “Lieutenant General of the King on Sea and Land.” He was repeatedly imprisoned for rash behaviour, on one occasion for striking a courtier, on another for wandering through the streets of London breaking the windows of sleeping people. He became Earl of Surrey in 1524 when his grandfather died and his father became Duke of Norfolk. In 1532 he accompanied his first cousin Anne Boleyn, the King, and the Duke of Richmond to France, staying there for more than a year as a member of the entourage of Francis I of France. In 1536 his first son, Thomas (later 4th Duke of Norfolk), was born, Anne Boleyn was executed on charges of adultery and treason, and the Duke of Richmond died at the age of 17 and was buried at one of the Howard homes, Thetford Abbey. In 1536 Surrey also served with his father against the Pilgrimage of Grace rebellion protesting against the Dissolution of the Monasteries. Literary activity and legacy He and his friend Sir Thomas Wyatt were the first English poets to write in the sonnet form that Shakespeare later used, and Surrey was the first English poet to publish blank verse (unrhymed iambic pentameter) in his translation of the second and fourth books of Virgil’s Aeneid. Together, Wyatt and Surrey, due to their excellent translations of Petrarch’s sonnets, are known as “Fathers of the English Sonnet”. While Wyatt introduced the sonnet into English, it was Surrey who gave them the rhyming meter and the division into quatrains that now characterizes the sonnets variously named English, Elizabethan or Shakespearean sonnets. Death and burial Henry VIII, consumed by paranoia and increasing illness, became convinced that Surrey had planned to usurp the crown from his son Edward. The King had Surrey imprisoned—with his father—sentenced to death on 13 January 1547, and beheaded for treason on 19 January 1547 (his father survived impending execution only by it being set for the day after the king happened to die, though he remained imprisoned). Surrey’s son Thomas became heir to the dukedom of Norfolk instead, inheriting it on the 3rd duke’s death in 1554. He is buried in a spectacular painted alabaster tomb in the church of St Michael the Archangel, Framlingham. Marriage and issue He married Frances de Vere, the daughter of John de Vere, 15th Earl of Oxford, and Elizabeth Trussell. They had two sons and three daughters: Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk (10 March 1536– 2 June 1572), married (1) Mary FitzAlan (2) Margaret Audley (3) Elizabeth Leyburne. Henry Howard, 1st Earl of Northampton, who died unmarried. Jane Howard, who married Charles Neville, 6th Earl of Westmorland. Margaret Howard, who married Henry Scrope, 9th Baron Scrope of Bolton. Katherine Howard, who married Henry Berkeley, 7th Baron Berkeley. In popular culture Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey was portrayed by actor David O’Hara in The Tudors, a television series which ran from 2007 to 2010. Ancestry References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Howard,_Earl_of_Surrey

i spent my early life in St Louis but learned about life in Califoria during the 70's. although i have grown up and joined the real world, my poetry reflects that girl in Venice when life held so much promise and magic....and i still believed the in the hopes of the 60s, mixed with the cynicism that came when the age turned wrong...

Born Asa Bundy Sheffey in 1913, Robert Hayden was raised in the poor neighborhood in Detroit called Paradise Valley. He had an emotionally tumultuous childhood and was shuttled between the home of his parents and that of a foster family, who lived next door. Because of impaired vision, he was unable to participate in sports, but was able to spend his time reading. In 1932, he graduated from high school and, with the help of a scholarship, attended Detroit City College (later Wayne State University). Hayden published his first book of poems, Heart-Shape in the Dust, in 1940, at the age of 27. He enrolled in a graduate English Literature program at the University of Michigan where he studied with W. H. Auden. Auden became an influential critical guide in the development of Hayden's writing. Hayden admired the work of Edna St. Vincent Millay, Elinor Wiley, Carl Sandburg, and Hart Crane, as well as the poets of the Harlem Renaissance, Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen, and Jean Toomer. He had an interest in African-American history and explored his concerns about race in his writing. Hayden's poetry gained international recognition in the 1960s and he was awarded the grand prize for poetry at the First World Festival of Negro Arts in Dakar, Senegal, in 1966 for his book Ballad of Remembrance. Explaining the trajectory of Hayden's career, the poet William Meredith wrote: "Hayden declared himself, at considerable cost in popularity, an American poet rather than a black poet, when for a time there was posited an unreconcilable difference between the two roles. There is scarcely a line of his which is not identifiable as an experience of black America, but he would not relinquish the title of American writer for any narrower identity." In 1975, Hayden received the Academy of American Poets Fellowship, and in 1976, he became the first black American to be appointed as Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress (later called the Poet Laureate). He died in Ann Arbor, Michigan, in 1980. References Poets.org - www.poets.org/poet.php/prmPID/196

This blog observes a teenage boy (myself) who struggles with external, internal, and eternal problems. He does his best to stay the path he has been told is "right", but as he goes, he asks himself philosophical questions on what is "right" or "just" and why he is chained to the path he questions.

Ralph Hodgson (9 September 1871– 3 November 1962), was an English poet, very popular in his lifetime on the strength of a small number of anthology pieces, such as The Bull. He was one of the more ‘pastoral’ of the Georgian poets. In 1954, he was awarded the Queen’s Gold Medal for Poetry. He seems to have covered his tracks in relation to much of his life; he was averse to publicity. This has led to claims that he was reticent. Far from that being the case, his friend Walter De La Mare found him an almost exhausting talker; but he made a point of personal privacy. He kept up a copious correspondence with other poets and literary figures, including those he met in his time in Japan such as Takeshi Saito. His poem The Bells of Heaven was ranked 85th in the list of Classic FM’s One Hundred Favourite Poems. Quoting from the biography which accompanied the poem: “He was one of the earliest writers to be concerned with ecology, speaking out against the fur trade and man’s destruction of the natural world.” Early life He was born in Darlington in County Durham to a coal mining father. In his youth he was a champion boxer and billiards player and worked in the theatre in New York before returning to England. From about 1890 he worked for a number of London publications. He was a comic artist, signing himself 'Yorick’, and became art editor on C. B. Fry’s Weekly Magazine of Sports and Out-of-Door Life. His first poetry collection, The Last Blackbird and Other Lines, appeared in 1907. It is said that his father was a coal merchant, and that he ran away from home while at school. Poet and publisher In 1912 he founded a small press, At the Sign of the Flying Fame, with the illustrator Claud Lovat Fraser (1890–1921) and the writer and journalist Holbrook Jackson (1874–1948). It published his collection The Mystery (1913). Hodgson received the Edmond de Polignac Prize in 1914, for a musical setting of The Song of Honour, and was included in the Georgian Poetry anthologies. The press became inactive in 1914 as World War I broke out and he and Lovat joined the armed forces (it did continue until 1923). Hodgson was in the Royal Navy and then the British Army. His reputation was established by Poems (1917). In Japan His first wife Janet (née Chatteris) died in 1920. He then married Muriel Fraser (divorced 1932). Shortly after that he accepted an invitation to teach English at Tohoku University in Sendai, Japan. In 1933 he married Lydia Aurelia Bolliger, an American missionary and teacher there. While in Japan, Hodgson worked, almost anonymously, as part of the committee that translated the great collection of Japanese classical poetry, the Man’yōshū, into English. The high quality of the published translations is almost certainly the result of his “final revision” of the texts. This was an undertaking worthy of Arthur Waley and could arguably be considered Hodgson’s major accomplishment as a poet. Retirement in the USA In 1938 Hodgson left Japan, visited friends in the UK including Siegfried Sassoon (they had met 1919) and then settled permanently with Aurelia in Minerva, Ohio. He was involved there in publishing, under the Flying Scroll imprint, and some academic contacts. He died in Minerva. Later work Arthur Bliss set some of his poems to music. His Collected Poems appeared in 1961, The Skylark (1959) having been his only new book (other than the collaborative work in the Man’yōshū,) in many decades. Quotes “Some things have to be believed to be seen.” “The handwriting on the wall may be a forgery.” “Time, you old gypsy man, will you not stay, put up your caravan just for one day?” “Did anyone ever have a boring dream?” References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ralph_Hodgson