Info

Edward Hirsch (born January 20, 1950) is an American poet and critic who wrote a national bestseller about reading poetry. He has published nine books of poems, including The Living Fire: New and Selected Poems (2010), which brings together thirty-five years of work, and Gabriel: A Poem (2014), a book-length elegy for his son that The New Yorker calls “a masterpiece of sorrow.” He has also published five prose books about poetry. He is president of the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation in New York City (not to be mistaken with E.D. Hirsch, Jr.). Life Hirsch was born in Chicago. He had a childhood involvement with poetry, which he later explored at Grinnell College and the University of Pennsylvania, where he received a Ph.D. in folklore. Hirsch was a professor of English at Wayne State University. In 1985, he joined the faculty at the University of Houston, where he spent 17 years as a professor in the Creative Writing Program and Department of English. He was appointed the fourth president of the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation on September 3, 2002. He holds seven honorary degrees. Career Hirsch is a well-known advocate for poetry whose essays have been published in the American Poetry Review, The New York Times Book Review, The New York Review of Books, and elsewhere. He wrote a weekly column on poetry for The Washington Post Book World from 2002-2005, which resulted in his book Poet’s Choice (2006). His other prose books include Responsive Reading (1999), The Demon and the Angel: Searching for the Source of Artistic Inspiration (2002), and A Poet’s Glossary (2014), a complete compendium of poetic terms. He is the editor of Transforming Vision: Writers on Art (1994), Theodore Roethke’s Selected Poems (2005) and To a Nightingale (2007). He is the co-editor of A William Maxwell Portrait: Memories and Appreciations and The Making of a Sonnet: A Norton Anthology (2008). He also edits the series “The Writer’s World” (Trinity University Press). Hirsch’s first collection of poems, For the Sleepwalkers, received the Lavan Younger Poets Award from the Academy of American Poets and the Delmore Schwartz Memorial Award from New York University. His second book, Wild Gratitude, received the National Book Critics Circle Award in 1986. He was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1985 and a five-year MacArthur Fellowship in 1997. He received the William Riley Parker Prize from the Modern Language Association for the best scholarly essay in PMLA for the year 1991. He has also received an Ingram Merrill Foundation Award, a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, the Rome Prize from the American Academy in Rome, a Pablo Neruda Presidential Medal of Honor, and the American Academy of Arts and Letters Award for Literature. He is a former Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets. Hirsch’s book, How to Read a Poem and Fall in Love with Poetry (1999), was a surprise bestseller and is widely taught throughout the country. Works Poetry collections * For the Sleepwalkers, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1981) * Wild Gratitude, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1986) * The Night Parade, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1989) * Earthly Measures, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1994) ISBN 0-679-76566-2 * On Love, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1998) * Lay Back the Darkness (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2003) ISBN 0-375-41521-1 * Special Orders (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2008) ISBN 0-307-26681-8 * Gabriel A Poem (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2014) ISBN 978-0-385-35357-1 Non-fiction books * Transforming Vision: Writers on Art, Selected and Introduced by Edward Hirsch, (Boston: Little, Brown, 1994) ISBN 0-8212-2126-4 * How to Read a Poem and Fall in Love with Poetry, (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1999) ISBN 0-15-100419-6 * Responsive Reading, (1999) * 'Introduction’ in John Keats, Complete Poems and Selected Letters of John Keats, (New York: Modern Library, 2001) ISBN 0-375-75669-8 * The Demon and the Angel: Searching for the Source of Artistic Expression, (New York: Harcourt Brace, 2002) * Poet’s Choice, (New York: Harcourt, 2006) ISBN 0-15-101356-X * A Poet’s Glossary, (Boston & New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014) ISBN 978-0-15-101195-7 Editor * Transforming Vision: Writers on Art, (The Art Institute of Chicago/ Bulfinch Press, 1994) ISBN 978-0821221266 * A William Maxwell Portrait, (Norton, 2004) ISBN 978-0393057713 * Theodore Roethke: Selected Poems, (The Library of America, 2005) ISBN 978-1931082785 * Irish Writers on Writing, edited with Eavan Boland, (Trinity University Press, 2007) ISBN 9781595340320 * Polish Writers on Writing, edited with Adam Zagajewski, (Trinity University Press, 2007) ISBN 9781595340337 * To a Nightingale: Poems from Sappho to Borges, (Braziller, 2007) ISBN 978-0807616277 * The Making of a Sonnet, (Norton, 2008) ISBN 978-0393333534 * Hebrew Writers on Writing, edited with Peter Cole (Trinity University Press, 2008) ISBN 9781595340528 * Nineteenth-Century American Writers on Writing, edited with Brenda Wineapple (Trinity University Press, 2010) ISBN 9781595340696 * Chinese Writers on Writing, edited with Arthur Sze (Trinity University Press, 2010) ISBN 9781595340634 * Romanian Writers on Writing, edited with Norman Manea, (Trinity University Press, 2011) ISBN 9781595340825 References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Hirsch

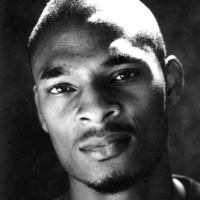

Terrance Hayes (born November 18, 1971) is an American poet and educator who has published five poetry collections. His 2010 collection, Lighthead, won the National Book Award for Poetry in 2010. In September 2014, he was one of 21 recipients of the prestigious MacArthur fellowships awarded to individuals who show outstanding creativity in their work. Life and education Hayes was born in Columbia, South Carolina. He received a B.A. from Coker College and an M.F.A. from the University of Pittsburgh writing program. He was a Professor of Creative Writing at Carnegie Mellon University until 2013, at which time he joined the faculty at the English Department at the University of Pittsburgh. He lives in Pittsburgh with his wife, the poet Yona Harvey, who also serves as a professor at the University of Pittsburgh, and their children. Works * Hayes first book of poetry, Muscular Music (1999), won both a Whiting Award and the Kate Tufts Discovery Award. His second collection, Hip Logic (2002), won the National Poetry Series, was a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Award, and runner-up for the James Laughlin Award from the Academy of American Poets. He won the National Book Award for Lighthead. * Hayes poems have appeared in literary journals and magazines including The New Yorker, The American Poetry Review, Ploughshares, Fence, The Kenyon Review, Jubilat Harvard Review, West Branch, Poetry, and The Adroit Journal’. * In praising Hayes’s work, Cornelius Eady has said: “First you’ll marvel at his skill, his near-perfect pitch, his disarming humor, his brilliant turns of phrase. Then you’ll notice the grace, the tenderness, the unblinking truth-telling just beneath his lines, the open and generous way he takes in our world.” * In September 2014, he was honored as one of the 21 2014 fellows of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. The fellowship comes with a $625,000 stipend over five years and is one of the most prestigious prizes that is awarded for artists, scholars and professionals. * In January 2017, Hayes was elected a Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets. Awards * * 2014 MacArthur Foundation Fellow * 2011 United States Artists Zell Fellow for Literature * 2010 National Book Award for Poetry, for Lighthead * Pushcart Prize, a Best American Poetry 2005 selection * National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship * 2009 Guggenheim Fellowship * James Laughlin Award runner-up, from the Academy of American Poets * Kate Tufts Discovery Award for Muscular Music (1999) * 2001 National Poetry Series, for Hip Logic * 1999 Whiting Award Poetry collections * * How to Be Drawn (Penguin Books, 2015) * Lighthead (Penguin Books, 2010)—winner of the National Book Award * Wind in a Box. Penguin Books. 2006. ISBN 9781440626982. * Hip Logic. Penguin Books. 2002. ISBN 978-0-14-200139-4. * Muscular Music (Tia Chucha Press, 1999; reissued by Carnegie Mellon University Press, 2006) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Terrance_Hayes

Hey! I went through a stage where poetry was an everyday thing for me and I thought I may as well share it instead of filling my book with it.... I don't write as often anymore but would love to start it up again and need some inspiration. I'm a fantasy writer, those of you who have read my poetry so far may notice a lot of it is more horror wirting then nice poetry.. I was in a dark place when I started writing and it helped to express my feelings on paper instead of taking it out on others and dragging myself down, it helped me get through that tough time and back onto my feet so I really do LOVE poetry :) Majority of my poetry is made up, for example, I have never been to the snow.... But I enjoy the fantasy of it of writing whatever you like. The rest of my poems though, are real and based on real life events and I will more than likely note that on my poems. Thank you for taking the time to read this through, enjoy my poetry and feedback is appreciated! :) Cheeers mate!

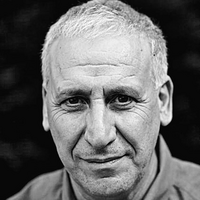

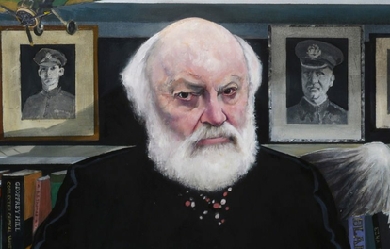

Anthony Evan Hecht (January 16, 1923– October 20, 2004) was an American poet. His work combined a deep interest in form with a passionate desire to confront the horrors of 20th century history, with the Second World War, in which he fought, and the Holocaust being recurrent themes in his work. Biography Early years Hecht was born in New York City to German-Jewish parents. He was educated at various schools in the city– he was a classmate of Jack Kerouac at Horace Mann School– but showed no great academic ability, something he would later refer to as “conspicuous.” However, as a freshman English student at Bard College in New York he discovered the works of Stevens, Auden, Eliot, and Dylan Thomas. It was at this point that he decided he would become a poet. Hecht’s parents were not happy at his plans and tried to discourage them, even getting family friend Ted Geisel, better known as Dr. Seuss, to attempt to dissuade him. In 1944, upon completing his final year at Bard, Hecht was drafted into the 97th Infantry Division and was sent to the battlefields in Europe. He saw combat in Germany in the “Ruhr Pocket” and in Cheb in Czechoslovakia. However, his most significant experience occurred on April 23, 1945 when Hecht’s division helped liberate Flossenbürg concentration camp. Hecht was ordered to interview French prisoners in the hope of gathering evidence on the camp’s commanders. Years later, Hecht said of this experience, The place, the suffering, the prisoners’ accounts were beyond comprehension. For years after I would wake shrieking. Career After the war ended, Hecht was sent to Japan, where he became a staff writer with Stars and Stripes. He returned to the US in March 1946 and immediately took advantage of the G.I. bill to study under the poet-critic John Crowe Ransom at Kenyon College, Ohio. Here he came into contact with fellow poets such as Randall Jarrell, Elizabeth Bishop, and Allen Tate. He later received his master’s degree from Columbia University. In 1947 Hecht attended the University of Iowa and taught in the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, together with writer Robie Macauley, with whom Hecht had served during World War II, but, suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder after his war service, gave it up swiftly to enter psychoanalysis. Hecht released his first collection, A Summoning of Stones, in 1954. In this work his mastery of a wide range of poetic forms were clear as was his awareness of the forces of history, which he had seen first hand. Even at this stage Hecht’s poetry was often compared with that of Auden, with whom Hecht had become friends in 1951 during a holiday on the Italian island of Ischia, where Auden spent each summer. In 1993 Hecht published The Hidden Law, a critical reading of Auden’s body of work. During his career Hecht won many fans, and prizes, including the Rome Prize in 1951 and the 1968 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry for his second work The Hard Hours. It was within this volume that Hecht first addressed his own experiences of World War II - memories that had caused him to have a nervous breakdown in 1959. Hecht spent three months in hospital following his breakdown, although he was spared electric shock therapy, unlike Sylvia Plath, whom he had encountered while teaching at Smith College. Hecht’s main source of income was as a teacher of poetry, most notably at the University of Rochester, where he taught from 1967 to 1985. He also spent varying lengths of time teaching at other notable institutions such as Smith, Bard, Harvard, Georgetown, and Yale. Between 1982 and 1984, he held the esteemed position of Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress. Hecht won a number of notable literary awards including: the 1968 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry (for the volume The Hard Hours), the 1983 Bollingen Prize, the 1988 Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize, the 1989 Aiken Taylor Award for Modern American Poetry, the 1997 Wallace Stevens Award, the 1999/2000 Frost Medal, and the Tanning Prize. Hecht died October 20, 2004, at his home in Washington, D. C.; he is buried at the cemetery at Bard College. One month later, on November 17, Hecht was awarded the National Medal of Arts, accepted on his behalf by his wife, Helen Hecht. The Anthony Hecht prize is awarded annually by the Waywiser press. Bibliography * Poetry * A Summoning of Stones (1954) * The Hard Hours (1967) * Millions of Strange Shadows (1977) * The Venetian Vespers (1979) * The Transparent Man (1990) * Flight Among the Tombs (1998) * The Darkness and the Light (2001) * Translations * Aeschylus’s Seven Against Thebes (1973) (with Helen Bacon) * Other Works * Obbligati: Essays in Criticism (1986) * The Hidden Law: The Poetry of W. H. Auden (1993) * On the Laws of the Poetic Art (1995) * Melodies Unheard: Essays on the Mysteries of Poetry (Johns Hopkins University Press) (2003) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anthony_Hecht

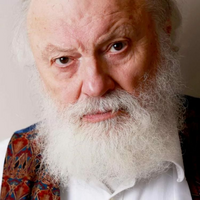

Sir Geoffrey William Hill, FRSL (18 June 1932– 30 June 2016) was an English poet, professor emeritus of English literature and religion, and former co-director of the Editorial Institute, at Boston University. Hill has been considered to be among the most distinguished poets of his generation and was called the “greatest living poet in the English language.” From 2010 to 2015 he held the position of Professor of Poetry in the University of Oxford. Following his receiving the Truman Capote Award for Literary Criticism in 2009 for his Collected Critical Writings, and the publication of Broken Hierarchies (Poems 1952–2012), Hill is recognised as one of the principal contributors to poetry in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Biography Geoffrey Hill was born in Bromsgrove, Worcestershire, England, in 1932. When he was six, his family moved to nearby Fairfield in Worcestershire, where he attended the local primary school, then the grammar school in Bromsgrove. “As an only child, he developed the habit of going for long walks alone, as an adolescent deliberating and composing poems as he muttered to the stones and trees.” On these walks he often carried with him Oscar Williams’ A Little Treasury of Modern Poetry (1946), and Hill speculates: “there was probably a time when I knew every poem in that anthology by heart.” In 1950 he was admitted to Keble College, Oxford to read English, where he published his first poems in 1952, at the age of twenty, in an eponymous Fantasy Press volume (though he had published work in the Oxford Guardian—the magazine of the University Liberal Club—and The Isis). Upon graduation from Oxford with a First, Hill embarked on an academic career, teaching at the University of Leeds from 1954 until 1980, from 1976 as professor of English Literature. After leaving Leeds, he spent a year at the University of Bristol on a Churchill Scholarship before becoming a teaching fellow at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, where he taught from 1981 until 1988. He then moved to the United States, to serve as University Professor and Professor of Literature and Religion at Boston University. In 2006, he moved back to Cambridge, England. Hill was married twice. His first marriage to Nancy Whittaker, which produced four children, Julian, Andrew, Jeremy and Bethany, ended in divorce. His second marriage to the American poet, and later Anglican priest, Alice Goodman occurred in 1987. The couple had a daughter, Alberta. The marriage lasted until Hill’s death. Awards and honours Mercian Hymns won the Alice Hunt Bartlett Prize and the inaugural Whitbread Award for Poetry in 1971. Hill won as well the Eric Gregory Award in 1961. Hill was awarded an honorary D.Litt. degree by the University of Leeds in 1988, the same year he received an Ingram Merrill Foundation Award. Hill was also an Honorary Fellow of Keble College, Oxford; an Honorary Fellow of Emmanuel College, Cambridge; a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature; and a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. In 2009 his Collected Critical Writings won the Truman Capote Award for Literary Criticism, the largest annual cash prize in English-language literary criticism. Hill was created a Knight Bachelor in the 2012 New Year Honours for services to literature. Oxford candidacy In March 2010 Hill was confirmed as a candidate in the election of the Professor of Poetry in the University of Oxford, with a broad base of academic support. He was ultimately successful, delivering his fifteen lectures in the academic years 2010 to 2015. The lectures progressed chronologically, beginning with Shakespeare’s Sonnets and concluding with a critique of Philip Larkin’s poem “Church Going”. Writing Hill’s poetry encompasses a variety of styles, from the dense and allusive writing of King Log (1968) and Canaan (1997) to the simplified syntax of the sequence 'The Pentecost Castle’ in Tenebrae (1978) to the more accessible poems of Mercian Hymns (1971), a series of thirty poems (sometimes called 'prose-poems’ a label which Hill rejects in favour of 'versets’) which juxtapose the history of Offa, eighth-century ruler of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Mercia, with Hill’s own childhood in the modern Mercia of the West Midlands. Seamus Heaney said of Hill, 'He has a strong sense of the importance of the maintenance of speech, a deep scholarly sense of the religious and political underpinning of everything in Britain’. Kenneth Haynes editor, of Broken Hierarchies, commented 'the annotation is not the hard part with Hill’s poems... the difficulty only begins after looking things up’. Elegy is Hill’s dominant mode; he is a poet of phrases rather than cadences. Regarding both his style and subject, Hill is often described as a “difficult” poet. In an interview in The Paris Review (2000), which published Hill’s early poem “Genesis” when he was still at Oxford, Hill defended the right of poets to difficulty as a form of resistance to the demeaning simplifications imposed by 'maestros of the world’. Hill also argued that to be difficult is to be democratic, equating the demand for simplicity with the demands of tyrants. He makes circumspect use of traditional rhetoric (as well as that of modernism), but he also transcribes the idioms of public life, such as those of television, political sloganeering, and punditry. Hill has been consistently drawn to morally problematic and violent episodes in British and European history and has written poetic responses to the Holocaust in English, “Two Formal Elegies”, “September Song” and “Ovid in the Third Reich”. His accounts of landscape (especially that of his native Worcestershire) are as intense as his encounters with history.Hill has also worked in theatre - in 1978, the National Theatre in London staged his 'version for the English stage’ of Brand by Henrik Ibsen, written in rhyming verse.Hill’s distaste for conclusion, however, has led him, in 2000's Speech! Speech! (118), to scorn the following argument as a glib get-out: 'ACCESSIBLE / traded as DEMOCRATIC, he answers / as he answers móst things these days | easily.' Throughout his corpus Hill is uncomfortable with the muffling of truth-telling that verse designed to sound well, for its contrivances of harmony, must permit. The constant buffets of Hill’s suspicion of lyric eloquence—can it truly be eloquent?—against his talent for it (in Syon, a sky is 'livid with unshed snow’) become in the poems a sort of battle in style, where passages of singing force (ToL: 'The ferns / are breast-high, head-high, the days / lustrous, with their hinterlands of thunder’) are balanced with prosaic ones of academese and inscrutable syntax. In the long interview collected in Haffenden’s Viewpoints there is described the poet warring himself to witness honestly, to make language as tool say truly what he believes is true of the world. Criticism The violence of Hill’s aesthetic has been criticised by the Irish poet-critic Tom Paulin, who draws attention to the poet’s use of the Virgilian trope of 'rivers of blood’– as deployed infamously by Enoch Powell– to suggest that despite Hill’s multi-layered irony and techniques of reflection, his lyrics draw their energies from an outmoded nationalism, expressed in what Hugh Haughton has described as a 'language of the past largely invented by the Victorians’. Yet as Raphael Ingelbien notes, 'Hill’s England... is a landscape which is fraught with the traces of a history that stretches so far back that it relativizes the Empire and its aftermath’. Harold Bloom has called him ‘the strongest British poet now active.’ * For his part, Hill addressed some of the misperceptions about his political and cultural beliefs in a Guardian interview in 2002. There he suggested that his affection for the “radical Tories” of the 19th century, while recently misunderstood as reactionary, was actually evidence of a progressive bent tracing back to his working class roots. He also indicated that he could no longer draw a firm distinction between “Blairite Labour” and the Thatcher-era Conservatives, lamenting that both parties had become solely oriented toward “materialism”. * Hill’s style has also been subject to parody: Wendy Cope includes a two-stanza parody of the Mercian Hymns entitled “Duffa Rex” in Making Cocoa for Kingsley Amis. Bibliography Poetry collections * For the Unfallen (1959) * Preghiere (1964) * King Log (1968) * Mercian Hymns (1971) * Somewhere Is Such a Kingdom: Poems 1952-1971 (1975) * Tenebrae (1978) * The Mystery of the Charity of Charles Péguy (1983) * New & Collected Poems, 1952-1992. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. January 2000. ISBN 0-618-00188-3. * Canaan. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 1998. ISBN 0-395-92486-3. * The Triumph of Love. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 15 December 1999. ISBN 0-618-00183-2. * Speech! Speech! (2000) - long poem, comprising 120 12-line stanzas * The Orchards of Syon (2002) * Scenes from Comus (2005) * A Treatise of Civil Power. Yale University Press. 2007. ISBN 978-0-300-13149-9. * Without Title Yale University Press. 2006, ISBN 978-0-300-12176-6. * Selected Poems. Yale University Press. 1 April 2010. ISBN 978-0-300-16430-5. * A Treatise of Civil Power (Penguin, 2007) * Oraclau | Oracles (Clutag Press, 2010) * Clavics (Enitharmon Press, 2011) * Odi Barbare (Clutag Press, 2012) * Broken Hierarchies: Poems 1952-2012. OUP Oxford. November 2013. ISBN 978-0-19-960589-7. Essay collections * The Lords of Limit (1984) * The Enemy’s Country (1991) * Style and Faith (2003) * Collected Critical Writings (2008) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geoffrey_Hill

Julia Ward Howe (/haʊ/; May 27, 1819– October 17, 1910) was an American poet and author, best known for writing “The Battle Hymn of the Republic”. She was also an advocate for abolitionism and was a social activist, particularly for women’s suffrage. Personal life Early life Howe was born in New York City. She was the fourth of seven children born to an upper middle class couple. Her father Samuel Ward III was a Wall Street stockbroker, well-to-do banker, and strict Calvinist. Her mother was the occasional poet Julia Rush Cutler, related to Francis Marion, the “Swamp Fox” of the American Revolution. She died of tuberculosis when her daughter was five years old. She was educated by private tutors and in schools for young ladies until she was sixteen. Her eldest brother Samuel Cutler Ward travelled in Europe and brought home a private library. She had access to these modern works, many contradicting the Calvinistic world view presented by her father. She became well read and intelligent, though as much a social butterfly as she was a scholar. She was brought into contact with some of the greatest minds of her time because of her father’s status as a successful banker. She interacted with Charles Dickens, Charles Sumner, and Margaret Fuller. Sam married into the prominent Astor family, allowing him great social freedom that he shared with his sister. The siblings were cast into mourning time when their father died in 1839; shortly afterwards, brother Henry died, then Samuel’s wife Emily died, along with their newborn child. Marriage and children Julia was visiting Boston in 1841 when she met Samuel Gridley Howe (1801—1876), a physician and reformer who founded the Perkins School for the Blind. They announced their engagement quite suddenly on February 21. Howe had courted her for a time, but he had more recently shown an interest in her sister Louisa. In 1843, they married despite their eighteen-year age difference. She gave birth to their first child while honeymooning in Europe, eleven months later. She bore their last child in 1858 at the age of forty. They had six children: Julia Romana Howe (1844–1886), Florence Marion Howe (1845–1922), Henry Marion Howe (1848–1922), Laura Elizabeth Howe (1850–1943), Maud Howe (1855–1948), and Samuel Gridley Howe, Jr. (1858–1863). Julia was likewise an aunt of novelist Francis Marion Crawford. Howe lived and raised her children in South Boston, while her husband pursued his advocacy work. She hid her unhappiness with their marriage behind a cheerful demeanor and singing at parties, earning the nickname “the family champagne” from her children. She made frequent visits to Gardiner, Maine where she stayed at “The Yellow House,” a home built originally in 1814 and later home to her daughter Laura. Writing She was unhappy with her surroundings, so she took lectures, and studied foreign languages, and wrote plays and dramas. Julia had published essays on Goethe, Schiller and Lamartine before her marriage to Howe, in the New York Review and Theological Review. Her book Passion-Flowers was published in December 1853. The book collected intensely personal poems and was written without the awareness of her husband, who was then editing the Free Soil newspaper The Commonwealth. Her second anonymous collection, Words for the Hour, appeared in 1857. She went on to write plays such as Leonora, The World’s Own, and Hippolytus. These works all contained allusions to her stultifying marriage. She went on many trips, several for missions. In 1860, she published a book, A Trip to Cuba, which told of an 1859 trip she had taken. It had generated outrage from William Lloyd Garrison, an abolitionist, for its derogatory view of Blacks. (Julia had only recently become an abolitionist in the 1850s, her family believing it to be a social evil. She thus believed it was morally right to free the slaves but did not believe in social or racial equality.) Several letters on High Newport society were published in the New York Tribune in 1860, as well. Howe’s being a published author troubled her husband greatly, especially due to the fact that her poems many times had to do with critiques of women’s roles as wives, her own marriage, and women’s place in society. Their marriage problems escalated to the point where they separated in 1852. Samuel, when he became her husband, had also taken complete control of her estate income. Upon her husband’s death in 1876, she had found that through a series of bad investments that most of her money had been spent. Howe’s writing and social activism were greatly shaped by her upbringing and married life. Much study has gone into her difficult marriage and how it influenced her work, both written and active. Social activism She was inspired to write “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” after she and her husband visited Washington, D.C., and met Abraham Lincoln at the White House in November 1861. During the trip, her friend James Freeman Clarke suggested she write new words to the song “John Brown’s Body”, which she did on November 19. The song was set to William Steffe’s already-existing music and Howe’s version was first published in the Atlantic Monthly in February 1862. It quickly became one of the most popular songs of the Union during the American Civil War. Now that Howe was in the public eye, she produced eleven issues of the literary magazine, Northern Lights, in 1867. That same year she wrote about her travels to Europe in From the Oak to the Olive. After the war she focused her activities on the causes of pacifism and women’s suffrage. By 1868, Julia’s husband no longer opposed her involvement in public life, so Julia decided to become active in reform. She helped found the New England Women’s Club and the New England Woman Suffrage Association. She served as president for nine years beginning in 1868. In 1869, she became co-leader with Lucy Stone of the American Woman Suffrage Association. Then, in 1870, she became president of the New England Women’s Club. After her husband’s death in 1876, she focused more on her interests in reform. She was the founder and from 1876 to 1897 president of the Association of American Women, which advocated for women’s education. She also served as president of organizations like the Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association and the New England Suffrage Association. In 1870 she founded the weekly Woman’s Journal, a suffragist magazine which was widely read. She contributed to it for twenty years. That same year, she wrote her “Appeal to womanhood throughout the world”, later known as the Mother’s Day Proclamation. It asked women from the world to join for world peace. (See Category:Pacifist feminism.) In 1872, she asked that “Mother’s Day” be celebrated on the 2nd of June. Her efforts were not successful, and by 1893 she was wondering if the 4th of July could be remade into “Mother’s Day”. In 1874, she edited a coeducational defense titled Sex and Education. She wrote a collection about the places she lived in 1880 called Modern Society. In 1883, Howe published a biography of Margaret Fuller. Then, in 1885 she published another collection of lectures called Is Polite Society Polite? ("Polite society" is a euphemism for the upper class.) Finally in 1899 she published her popular memoirs, Reminiscences. She continued to write until her death. In 1881, Howe was elected president of the Association for the Advancement of Women. Around the same time, Howe went on a speaking tour of the Pacific coast, and founded the Century Club of San Francisco. In 1890, she helped found the General Federation of Women’s Clubs, to reaffirm the Christian values of frugality and moderation. From 1891-1893, she served as president for the second time of the Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association. Until her death, she was president of the New England Woman Suffrage Association. From 1893 to 1898 she directed the General Federation of Women’s Clubs, and headed the Massachusetts Federation of Women’s Clubs. In 1908 Julia was the first woman to be elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters, a society; its goal is to “foster, assist, and sustain excellence” in American literature, music, and art. Death Howe’s accomplishments mostly reside in her contribution to women’s rights. She laid the foundation for women’s rights groups both in her own home and in the public eye. Howe died of pneumonia October 17, 1910, at her home, Oak Glen, in Portsmouth, Rhode Island at the age of 91. She is buried in the Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts. At her memorial service approximately 4,000 individuals sang “Battle Hymn of the Republic” as a sign of respect as it was the custom to sing that song at each of Julia’s speaking engagements. After her death, her children collaborated on a biography, published in 1916. It won the Pulitzer Prize for Biography. Honors On January 28, 1908, at age 88, Howe became the first woman elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Howe was inducted posthumously into the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1970. She has been honored by the U.S. Postal Service with a 14¢ Great Americans series postage stamp issued in 1987. The Julia Ward Howe School of Excellence in Chicago’s Austin community is named in her honor. The Howe neighborhood in Minneapolis, MN was named for her. The Julia Ward Howe Academics Plus Elementary School in Philadelphia was named in her honor in 1913. It celebrates its 100th anniversary in 2013-14. Her Rhode Island home, Oak Glen, was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1978. Her Boston home is a stop on the Boston Women’s Heritage Trail. Works and collections Poetry Passion-Flowers (1854) Words for the Hour (1857) From Sunset Ridge: Poems Old and New (1898) Later Lyrics (1866) At Sunset (published posthumously, 1910) Other works The Hermaphrodite. Incomplete, but probably composed between 1846 and 1847. Published by University of Nebraska Press, 2004 From the Oak to the Olive (travel writing, 1868) Modern Society (essays, 1881) Margaret Fuller (Marchesa Ossoli) (biography, 1883) Woman’s work in America (1891) Is Polite Society Polite? (essays, 1895) Reminiscences: 1819–1899 (autobiography, 1899)