Info

The Head of an Old Man

Anthony van Dyck

1618 – 1620

Museo Nacional del Prado

Alice Christiana Gertrude Meynell (née Thompson; 11 October 1847– 27 November 1922) was an English writer, editor, critic, and suffragist, now remembered mainly as a poet. Biography Alice Christiana Gertrude Thompson was born in Barnes, London, to Thomas James and Christiana (née Weller) Thompson. The family moved around England, Switzerland, and France, but she was brought up mostly in Italy, where a daughter of Thomas from his first marriage had settled. Her father was a friend of Charles Dickens. Preludes (1875) was her first poetry collection, illustrated by her elder sister Elizabeth (the artist Lady Elizabeth Butler, 1846–1933, whose husband was Sir William Francis Butler). The work was warmly praised by Ruskin, although it received little public notice. Ruskin especially singled out the sonnet “Renunciation” for its beauty and delicacy. After Alice, the entire Thompson family converted to the Catholic Church (1868 to 1880), and her writings migrated to subjects of religious matters. This eventually led her to the Catholic newspaper publisher and editor Wilfrid Meynell (1852–1948) in 1876. A year later (in 1877) she married Meynell, and they settled in Kensington. They became the proprietors and editors of such magazines as The Pen, the Weekly Register, and Merry England, among others. Alice and Wilfrid Meynell had eight children, Sebastian, Monica, Everard, Madeleine, Viola, Vivian (who died at three months), Olivia, and Francis. Viola Meynell (1885–1956) became an author in her own right, and the youngest child Francis Meynell (1891–1975) was a poet and printer, co-founding the Nonesuch Press. She was much involved in editorial work on publications with her husband, and in her own writing, poetry and prose. She wrote regularly for The World, The Spectator, The Magazine of Art, the Scots Observer (which became the National Observer, both edited by W. E. Henley), The Tablet, The Art Journal, the Pall Mall Gazette, and The Saturday Review. The poet Francis Thompson, down and out in London and trying to recover from his opium addiction, sent the couple a manuscript. His poems were first published in Wilfrid’s Merry England, and the Meynells became a supporter of Thompson. His 1893 book Poems was a Meynell production and initiative. Another supporter of Thompson was the poet Coventry Patmore. Alice had a deep friendship with Patmore, lasting several years, which led to his becoming obsessed with her, forcing her to break with him. At the end of the 19th century, in conjunction with uprisings against the British (among them the Indians’, the Zulus’, the Boxer Rebellion, and the Muslim revolt led by Muhammad Ahmed in the Sudan), many European scholars, writers, and artists, began to question Europe’s colonial imperialism. This led the Meynells and others in their circle to speak out for the oppressed. Alice Meynell was a vice-president of the Women Writers’ Suffrage League, founded by Cicely Hamilton and active 1908–19. Death and legacy After a series of illnesses, including migraine and depression, she died 27 November 1922. She is buried at Kensal Green Catholic Cemetery, London, England. There is a London Borough Council commemorative blue plaque on the front wall of the property at 47 Palace Court, Bayswater, London, W2, where she and her husband once lived.

I write out my emotions, as every poet does of course. I am a passionate believer that poetry indeed is not just merely told, or thought, it is felt with the heart. True poetry is an extension of one's soul on paper, to touch other's souls in order for the author to be understood or to tell a story. I am Josiah, I am 17 years old. Most of my other poems were written to a girl I was infatuated with, and got my heart miserably broken, but we are best friends now. I still love to write about love though; nowadays my more romantic poems are directed to a wonderful young woman who I regard as the one. She is a true blessing. My other poems are about beautiful things, or my mental hardships that plague me, but are not forever. I hope all of you thoroughly enjoy my poetry.

Lizelia Augusta Jenkins Moorer (September 1868 - May 24, 1936) was a poet and teacher in Orangeburg, South Carolina. She taught at the Normal and Grammar Schools, Claflin University, Orangeburg, South Carolina from 1895 to 1899. In 1907, she published a collection of poems, “Prejudice Unveiled and Other Poems”. Her work was called, by Joan R. Sherman, the “best poems on racial issues written by any black woman until the middle of the century”. Moorer attacks “lynching, debt peonage, white rape, Jim Crow segregation, and the hypocrisy of the church and the white press”. Moorer was born in September 1868 to Warren D. Jenkins and Mattie Miller in Pickens, South Carolina. In 1899, she married Jacob Moorer, an attorney in Orangeburg who frequently saw cases defending the rights of blacks against what he saw as a prejudiced legal system in South Carolina. In particular, he fought against the constitutionality of election law in the 1895 South Carolina Constitution. Lizelia was also a very strong activist. Beyond her poetry, she was active in the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, serving as State Vice-President in South Carolina in 1910. In 1924, she attended the 1924 Methodist Episcopal Church General Conference where she gave a speech arguing that women should be allowed to be ordained within the Methodist Church. During that conference, women were, indeed, given the right to be ordained as local deacons and elders.

William Matthews (November 11, 1942– November 12, 1997) was an American poet and essayist. Born and raised in Cincinnati, Ohio, Matthews attended Berkshire School and later earned a bachelor’s degree from Yale University as well as a master’s from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

"These words I write, they tell my story---not through what they say, but through what they make you feel." A Few of My Favorites: "Pain Creates Hope(Version 2)" "A New Appreciation" "Saving Grace" "The End" "Human being," like "Men working" and "Children playing," is a sentence with a noun, a verb, and the possibility of an imminent disaster.

James Ingram Merrill (March 3, 1926– February 6, 1995) was an American poet whose awards include the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry (1977) for Divine Comedies (1976). His poetry falls into two distinct bodies of work: the polished and formalist lyric poetry of his early career, and the epic narrative of occult communication with spirits and angels, titled The Changing Light at Sandover (published in three volumes from 1976 to 1980), which dominated his later career. Although most of his published work was poetry, he also wrote essays, fiction, and plays.

I was born in chicago public housing in the mid 70s. The lack of a male role model drove me in the wrong direction. I've always had a creative mind, I left home at an early age an spent most of my time in the streets. It was there I found my way into music an managed to get a record deal with an independent label. Things didn't go accordingly I ended up dealing drugs which almost cost me my life. Today I'm just a lonely soul trying to find its way.

Dame Emilie Rose Macaulay, DBE (1 August 1881– 30 October 1958) was an English writer, most noted for her award-winning novel The Towers of Trebizond, about a small Anglo-Catholic group crossing Turkey by camel. The story is seen as a spiritual autobiography, reflecting her own changing and conflicting beliefs. Macaulay’s novels were partly-influenced by Virginia Woolf; she also wrote biographies and travelogues. Early years and education Macaulay was born in Rugby, Warwickshire the daughter of George Campbell Macaulay, a Classical scholar, and his wife, Grace Mary (née Conybeare). Her father was descended in the male-line directly from the Macaulay family of Lewis. She was educated at Oxford High School for Girls and read Modern History at Somerville College at Oxford University. Career Macaulay began writing her first novel, Abbots Verney (published 1906), after leaving Somerville and while living with her parents at Ty Isaf, near Aberystwyth, in Wales. Later novels include The Lee Shore (1912), Potterism (1920), Dangerous Ages (1921), Told by an Idiot (1923), And No Man’s Wit (1940), The World My Wilderness (1950), and The Towers of Trebizond (1956). Her non-fiction work includes They Went to Portugal, Catchwords and Claptrap, a biography of Milton, and Pleasure of Ruins. Macaulay’s fiction was influenced by Virginia Woolf and Anatole France. During World War I Macaulay worked in the British Propaganda Department, after some time as a nurse and later as a civil servant in the War Office. She pursued a romantic affair with Gerald O’Donovan, a writer and former Jesuit priest, from 1918 until his death in 1942. During the interwar period she was a sponsor of the pacifist Peace Pledge Union; however she resigned from the PPU and later recanted her pacifism in 1940. Her London flat was utterly destroyed in the Blitz, and she had to rebuild her life and library from scratch, as documented in the semi-autobiographical short story, Miss Anstruther’s Letters, which was published in 1942. The Towers of Trebizond, her final novel, is generally regarded as her masterpiece. Strongly autobiographical, it treats with wistful humour and deep sadness the attractions of mystical Christianity, and the irremediable conflict between adulterous love and the demands of the Christian faith. For this work, she received the James Tait Black Memorial Prize in 1956. Personal life Macaulay was never a simple believer in “mere Christianity”; however, and her writings reveal a more complex, mystical sense of the divine. That said, she did not return to the Anglican church until 1953; she had been an ardent secularist before and, while religious themes pervade her novels, previous to her conversion she often treats Christianity satirically, for instance in Going Abroad and The World My Wilderness. She never married, as a result of her lengthy and secret relationship with Gerald O’Donovan. They met in 1918 and the affair lasted until his death in 1942. She was created a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBE) on 31 December 1957 in the 1958 New Years Honours. Macaulay was an active feminist throughout her life. Dame Rose Macaulay died on 30 October 1958, aged 77. Memorable quotes From The Towers of Trebizond: “Adultery is a meanness and a stealing, a taking away from someone what should be theirs, a great selfishness, and surrounded and guarded by lies lest it should be found out. And out of meanness and selfishness and lying flow love and joy and peace beyond anything that can be imagined.” First line of The Towers of Trebizond, cited by librarian Nancy Pearl in “Famous First Words: A Librarian Shares Favorite Literary Opening Lines,” [1] hosted by Steve Inskeep on NPR’s Morning Edition, 8 September 2004, as an example among “some notable opening lines that have made Pearl’s heart pound”. “Take my camel, dear”, said my Aunt Dot, as she climbed down from this animal on her return from High Mass. From Staying with Relations. Discussing the coat worn by a visitor, a character remarks: “Is rabbit fur disgusting because it’s cheap, or is it cheap because it’s disgusting?”

Terence Alan “Spike” Milligan KBE (16 April 1918– 27 February 2002) was a comedian, writer and actor. The son of an Irish father and an English mother, his early life was spent in India where he was born. The majority of his working life was spent in the United Kingdom. He disliked his first name and began to call himself “Spike” after hearing a band on Radio Luxembourg called Spike Jones and his City Slickers. Milligan was the co-creator, main writer and a principal cast member of The Goon Show, performing a range of roles including the popular Eccles and Minnie Bannister characters. Milligan wrote and edited many books, including Puckoon and his seven-volume autobiographical account of his time serving during the Second World War, beginning with Adolf Hitler: My Part in His Downfall. He is also noted as a popular writer of comical verse; much of his poetry was written for children, including Silly Verse for Kids (1959). After success with the groundbreaking British radio programme, The Goon Show, Milligan translated this success to television with Q5, a surreal sketch show which is credited as a major influence on the members of Monty Python’s Flying Circus. He was the oldest, longest lived and last surviving member of the Goons. Milligan’s 1960 application for British citizenship and 1961 application for a British passport were blocked by his refusal to pledge an oath of allegiance to the United Kingdom, his adopted home for most of his adult life. When the Commonwealth Immigrants Act removed Indian-born Milligan’s automatic right to British citizenship in 1962, he promptly became an Irish citizen, exercising a right conferred through the automatic retroactive Irish citizenship of his Irish-born father. Early life Milligan was born in Ahmednagar, India, on 16 April 1918, the son of an Irish father, Captain Leo Alphonso Milligan, MSM, RA (1890–1969), who was serving in the British Indian Army. His mother, Florence Mary Winifred Kettleband (1893–1990), was English. He spent his childhood in Poona (India) and later in Rangoon, capital of British Burma. He was educated at the Convent of Jesus and Mary, Poona, and later at St Paul’s High School, Rangoon. On leaving school he played the cornet and discovered jazz. He also joined the Young Communist League in opposition of Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists, who were gaining support near his home in south London. After returning from Burma, Milligan lived most of his life in the United Kingdom apart from overseas service in the British Army in the Royal Artillery during the Second World War. Second World War During most of the late 1930s and early 1940s, Milligan performed as an amateur jazz vocalist and trumpeter before, during and after being called up for military service in the fight against Nazi Germany, but even then he wrote and performed comedy sketches as part of concerts to entertain troops. After his call-up but before being sent abroad, he and fellow musician Harry Edgington (1919–1993) (whose nickname 'Edge-ying-Tong’, inspired one of Milligan’s most memorable musical creations, the “Ying Tong Song”) would compose surreal stories, filled with puns and skewed logic, as a way of staving off the boredom of life in barracks. One biographer describes his early dance band work as follows: “He managed to croon like Bing Crosby and win a competition: he also played drums, guitar and trumpet, in which he was entirely self taught”; he also acquired a double bass, on which he took lessons and would strum in jazz sessions. Milligan had perfect pitch. During the Second World War, Milligan served as a signaller in the 56th Heavy Regiment Royal Artillery, D Battery, as Gunner Milligan, 954024. The unit was equipped with the obsolete First World War era BL 9.2-inch howitzer and based in Bexhill on the south coast of England. Milligan describes training with these guns in part two of Adolf Hitler: My Part in His Downfall, claiming that, during training, gun crews resorted to shouting “bang” in unison as they had no shells with which to practise. The unit was later re-equipped with the BL 7.2-inch howitzer and saw action as part of the First Army in the North African campaign and then in the succeeding Italian campaign. Milligan was appointed lance bombardier and was about to be promoted to bombardier, when he was wounded in action in the Italian theatre at the Battle of Monte Cassino. Subsequently hospitalised for a mortar wound to the right leg and shell shock, he was demoted by an unsympathetic commanding officer (identified in his war diaries as Major Evan “Jumbo” Jenkins) back to Gunner. It was Milligan’s opinion that Major Jenkins did not like him, because Milligan constantly kept the morale of his fellow soldiers up, whereas Jenkins’ approach was to take an attitude towards the troops similar to that of Lord Kitchener. An incident also mentioned was when Jenkins had invited Gunners Milligan and Edgington to his bivouac to play some jazz with him, only to discover that the musicianship of the gunners was far superior to his own ability to play the military tune “Whistling Rufus”. After hospitalisation, Milligan drifted through a number of rear-echelon military jobs in Italy, eventually becoming a full-time entertainer. He played the guitar with a jazz and comedy group called The Bill Hall Trio, in concert parties for the troops. After being demobilised, Milligan remained in Italy playing with the trio but returned to Britain soon after. While he was with the Central Pool of Artists (a group he described as composed “of bomb-happy squaddies”) he began to write parodies of their mainstream plays, which displayed many of the key elements of what would later become The Goon Show (originally called Crazy People) with Peter Sellers, Harry Secombe and Michael Bentine. Career The Goon Show Milligan returned to jazz in the late 1940s and made a precarious living with the Hall trio and other musical comedy acts. He was also trying to break into the world of radio, as a performer or script writer. His first success in radio was as writer for comedian Derek Roy’s show. After a delayed start, Milligan, Peter Sellers, Harry Secombe and Michael Bentine joined forces in a relatively radical comedy project, The Goon Show. During its first season the BBC titled the show as Crazy People, or in full, The Junior Crazy Gang featuring those Crazy People, the Goons!, an attempt to make the programme palatable to BBC officials, by connecting it with the popular group of theatre comedians known as The Crazy Gang. The first episode was broadcast on 28 May 1951 on the BBC Home Service. Although he did not perform as much in the early shows, Milligan eventually became a lead performer in almost all of the Goon Show episodes, portraying a wide range of characters including Eccles, Minnie Bannister, Jim Spriggs and the nefarious Count Moriarty. He was also the primary author of most of the scripts, although he co-wrote many scripts with various collaborators, most notably Larry Stephens and Eric Sykes. Most of the early shows were co-written with Stephens (and edited by Jimmy Grafton) but this partnership faltered after Series 3. Milligan wrote most of Series 4 but from Series 5 (coinciding with the birth of the Milligans’ second child, Seán) and through most of Series 6, he collaborated with Eric Sykes, a development that grew out of his contemporary business collaboration with Sykes in Associated London Scripts. Milligan and Stephens reunited during Series 6 but towards the end of Series 8 Stephens was sidelined by health problems and Milligan worked briefly with John Antrobus. The Milligan-Stephens partnership was finally ended by Stephens’ death from a brain haemorrhage in January 1959; Milligan later downplayed and disparaged Stephens’ contributions. The Goon Show was recorded before a studio audience and during the audience warm-up session, Milligan would play the trumpet, while Peter Sellers played on the orchestra’s drums. For the first few years the shows were recorded live, direct to 16-inch transcription disc, which required the cast to adhere closely to the script but by Series 4, the BBC had adopted the use of magnetic tape. Milligan eagerly exploited the possibilities the new technology offered—the tapes could be edited, so the cast could now ad-lib freely and tape also enabled the creation of groundbreaking sound effects. Over the first three series, Milligan’s demands for increasingly complex sound effects (or 'grams’, as they were then known) pushed technology and the skills of the BBC engineers to their limits—effects had to be created mechanically (foley) or played back from discs, sometimes requiring the use of four or five turntables running simultaneously. With magnetic tape, these effects could be produced in advance and the BBC engineers were able to create highly complex, tightly edited effects 'stings’ that would have been very difficult (if not impossible) to perform using foley or disc. In the later years of the series many Goon Show 'grams’ were produced for the series by members of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, a notable example being the “Major Bloodnok’s Stomach” effect, realised by Dick Mills. Although the Goons elevated Milligan to international stardom, the demands of writing and performing the series took a heavy toll. During Series 3 he suffered the first of several serious mental breakdowns, which also marked the onset of a decades-long cycle of manic-depressive illness. In late 1952, possibly exacerbated by suppressed tensions between the Goons’ stars, Milligan apparently became irrationally convinced that he had to kill Sellers but when he attempted to gain entry to Sellers’s neighbouring flat, armed with a potato knife, he accidentally walked straight through the plate-glass front door. He was hospitalised, heavily sedated for two weeks and spent almost two months recuperating; fortunately for the show, a backlog of scripts meant that his illness had little effect on production. Milligan later blamed the pressure of writing and performing The Goon Show, for both his breakdown and the failure of his first marriage. A lesser-known aspect of Milligan’s life in the 1950s and 1960s, was his involvement in the writers’ agency Associated London Scripts. Milligan married for the first time and began a family. This reportedly distracted him from writing so much, that he accepted an invitation from Eric Sykes to share his small office, leading to the creation of the co-operative agency. Television Milligan made several forays into television as a writer-performer, in addition to his many guest appearances on interview, variety and sketch comedy series from the 1950s to the 2000s. The Idiot Weekly, Price 2d (1956) starring Peter Sellers, was the first attempt to translate Goons humour to TV; it was followed by A Show Called Fred and Son of Fred, both made during 1956 and directed by Richard Lester, who went on to work with the Beatles. During a visit to Australia in 1958, a similar special was made for the Australian Broadcasting Commission, “The Gladys Half-Hour”, which also featured local actors Ray Barrett and John Bluthal, who would appear in several later Milligan projects. In 1961, Milligan co-wrote two episodes of the popular sitcom Sykes and a..., co-starring Sykes and Hattie Jacques and the one-off “Spike Milligan Offers A Series of Unrelated Incidents at Market Value”. The 15-minute series The Telegoons (1963), was the next attempt to transplant the Goons to television, this time using puppet versions of the familiar characters. The initial intention was to 'visualise’ original recordings of 1950s Goon Show episodes but this proved difficult, because of the rapid-fire dialogue and was ultimately frustrated by the BBC’s refusal to allow the original audio to be used. 15-minute adaptations of the original scripts by Maurice Wiltshire were used instead, with Milligan, Sellers and Secombe reuniting to provide the voices; according to a contemporary press report, they received the highest fees the BBC had ever paid for 15-minute shows. Two series were made in 1963 and 1964 and (presumably because it was shot on 35mm film rather than video) the entire series has reportedly been preserved in the BBC archives. Milligan’s next major TV venture was the sketch comedy series The World of Beachcomber (1968), made in colour for BBC 2; it is believed all 19 episodes are lost. That same year, the three Goons reunited for a televised re-staging of a vintage Goon Show for Thames Television, with John Cleese substituting for the late Wallace Greenslade but the pilot was not successful and no further programmes were made. In early 1969, Milligan starred in the ill-fated situation comedy Curry & Chips, created and written by Johnny Speight and featuring Milligan’s old friend and colleague Eric Sykes. Curry & Chips set out to satirise racist attitudes in Britain in a similar vein to Speight’s earlier creation, the hugely successful Till Death Us Do Part, with Milligan 'blacking up’ to play Kevin O’Grady, a half-Pakistani–half-Irish factory worker. The series generated numerous complaints, because of its frequent use of racist epithets and 'bad language’– one viewer reportedly complained of counting 59 uses of the word “bloody” in one episode– and it was cancelled on the orders of the Independent Broadcasting Authority after only six episodes. Milligan was also involved in the ill-fated programme The Melting Pot. Director John Goldschmidt’s film The Other Spike dramatised Milligan’s nervous breakdown in a film for Granada Television, for which Milligan wrote the screenplay and in which he played himself. Later that year, he was commissioned by the BBC to write and star in Q5, the first in the innovative “Q” TV series, acknowledged as an important precursor to Monty Python’s Flying Circus, which premiered several months later. There was a hiatus of several years, before the BBC commissioned Q6 in 1975. Q7 appeared in 1977, Q8 in 1978, Q9 in 1980 and There’s a Lot of It About in 1982. Milligan later complained of the BBC’s cold attitude towards the series and stated that he would have made more programs, had he been given the opportunity. A number of episodes of the earlier “Q” series are missing, presumed wiped. In 1979 he was a special guest star on The Muppet Show. From 1995 to 1998, he voiced the highly successful children’s animated series Wolves, Witches and Giants for ITV. The series was written by Ed Welch, who had featured in the “Q” series, collaborated with Spike on several audio productions, produced and directed by Simon & Sara Bor. The series was shown in over 100 territories including the UK and USA. Poetry and other writings Milligan also wrote verse, considered to be within the genre of literary nonsense. His poetry has been described by comedian Stephen Fry as “absolutely immortal—greatly in the tradition of Lear.” One of his poems, “On the Ning Nang Nong”, was voted the UK’s favourite comic poem in 1998 in a nationwide poll, ahead of other nonsense poets including Lewis Carroll and Edward Lear. This nonsense verse, set to music, became a favourite Australia-wide, performed week after week by the ABC children’s programme Playschool. Milligan included it on his album No One’s Gonna Change Our World in 1969, to aid the World Wildlife Fund. In December 2007 it was reported that, according to OFSTED, it is among the ten most commonly taught poems in primary schools in the UK. While depressed, he wrote serious poetry. He also wrote a novel Puckoon and a series of war memoirs, including Adolf Hitler: My Part in His Downfall (1971), “Rommel?” “Gunner Who?”: A Confrontation in the Desert (1974), Monty: His Part in My Victory (1976) and Mussolini: His Part in My Downfall (1978). Milligan’s seven volumes of memoirs cover the years from 1939 to 1950 (his call-up, war service, first breakdown, time spent entertaining in Italy and return to the UK). He also wrote comedy songs, including “Purple Aeroplane”, which was a parody of the Beatles’ song “Yellow Submarine”. Glimpses of his bouts with depression, which led to the nervous breakdowns, can be found in his serious poetry, which is compiled in Open Heart University. Theatre Treasure Island Bernard Miles gave Milligan his first straight acting role, as Ben Gunn, in the Mermaid Theatre production of Treasure Island. Miles described Milligan as: ... a man of quite extraordinary talents... a visionary who is out there alone, denied the usual contacts simply because he is so different he can’t always communicate with his own species .... Treasure Island played twice daily through the winter of 1961–62 and was an annual production at the Mermaid Theatre for some years. In the 1968 production, Barry Humphries played the role of Long John Silver, alongside William Rushton as Squire Trelawney and Milligan as Ben Gunn. To Humphries, Milligan’s “best performance must surely have been as Ben Gunn .., Milligan stole the show every night, in a makeup which took at least an hour to apply. His appearance on stage always brought a roar of delight from the kids in the audience and Spike had soon left the text far behind as he went off into a riff of sublime absurdity.” The Bed-Sitting Room In 1961–62, during the long pauses between the matinee and the evening show of Treasure Island, Milligan began talking to Miles about the idea he and John Antrobus were exploring, of a dramatised post-nuclear world. This became the one-act play The Bed-Sitting Room, which Milligan co-wrote with John Antrobus and which premiered at the Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury on 12 February 1962. It was adapted to a longer play and staged by Miles at London’s Mermaid Theatre, making its debut on 31 January 1963. It was a critical and commercial success and was revived in 1967 with a provincial tour before opening at London’s Saville Theatre on 3 May 1967. Richard Lester later directed a film version, released in 1969. Oblomov On 6 October 1964, Milligan appeared in Frank Dunlop’s production of the play Oblomov, at the Lyric Theatre in London, based on the novel by Russian writer Ivan Goncharov. Per Scudamore’s biography: Milligan’s fans and the theatrical world in general found it hard to believe that he was to appear in a straight play... He refused to be serious when questioned about his motives. In the story, Oblomov decides to spend his life in bed. Spike decided to identify with his character, and told disbelieving reporters that he thought it would be a nice comfortable rest for him. This was of course, prevarication. Spike was actually intrigued with Oblomov and had read a translation of Ivan Goncharov’s novel. Milligan’s involvement transformed the play. The first night started poorly, Joan Greenwood played Olga and later recalled that her husband André Morell thought the show was so appalling, they should get her out of the play. Per Scudamore: Nobody seemed at all comfortable in their roles and the audience began to hoot with laughter when Milligan’s slipper inadvertently went spinning across the stage into the stalls. That was the end of Spike’s playing straight. The audience demanded a clown, he became a clown. When he forgot his words, or disapproved of them, he simply made up what he felt to be more appropriate ones. That night there were no riotous first night celebrations and most of the cast seemed to go home stunned. The following night Milligan began to ad lib in earnest. The text of the show began to change drastically. The cast were bedevilled and shaken but they went along with him... Incredibly, the show began to resolve itself. The context changed completely. It was turned upside down and inside out. Cues and lines became irrelevant as Milligan verbally rewrote the play each night. By the end of the week, Oblomov had changed beyond recognition. Andre Morell came again... and afterwards said 'the man is a genius. He must be a genius—it’s the only word for him. He’s impossible—but he’s a genius!'. After Oblomov had run for a record-breaking five weeks at the Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith, it was retitled Son of Oblomov and moved to the Comedy Theatre in the West End. In an interview with Bernard Braden, Milligan described theatre as important to him: First it was a means of livelihood. And I had sort of lagged behind my confederates, that I... remained in the writing seat. And I realise that basically I was quite a good clown... and the one and only chance I ever had to prove that was in Oblomov when I clowned my way out of what was a very bad script... I clowned it into a West End success and uh, we kept changing it all the time. It was a tour de force of improvisation... all that ended it was I got fed up with it, that’s all.” Ken Russell films In 1959 Ken Russell made a short 35 mm film about and with Milligan entitled Portrait of a Goon. The making of the film is detailed in Paul Sutton’s 2012 authorised biography Becoming Ken Russell (ISBN 978-0-9572462-3-2). In 1971 Milligan played a humble village priest in Russell’s film The Devils. The scene was cut from the release print and is considered lost but photographs from the scene, together with Murray Melvin’s memory of that day’s filming, are included in Sutton’s 2014 book Six English Filmmakers (ISBN 978-0-9572462-5-6). Ad-libbing As illustrated in the description of his involvement in theatre, Milligan often ad-libbed. He also did this on radio and television. One of his last screen appearances was in the BBC dramatisation of Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast and he was (almost inevitably) noted as an ad-libber. One of Milligan’s ad-lib incidents occurred during a visit to Australia in the late 1960s. He was interviewed live on air and remained in the studio for the news broadcast that followed (read by Rod McNeil), during which Milligan constantly interjected, adding his own name to news items. As a result, he was banned from making any further live appearances on the ABC. The ABC also changed its national policy so that guests had to leave the studio after interviews were complete. A tape of the bulletin survives and has been included in an ABC Radio audio compilation, also on the BBC tribute CD, Vivat Milligna [sic]. Film and television director Richard Lester recalls that the television series A Show Called Fred was broadcast live. “I’ve seen very few moments of genius in my life but I witnessed one with Spike after the first show. He had brought around a silent cartoon” and asked Lester if his P.A. took shorthand. “She said she did. ‘Good, this needs a commentary.’ It was a ten-minute cartoon and Spike could have seen it only once, if that. He ad-libbed the commentary for it and it was perfect. I was open-mouthed at the raw comedy creation in front of me.” Cartoons and art Milligan contributed occasional cartoons to the satirical magazine Private Eye. Most were visualisations of one-line jokes. For example, a young boy sees the Concorde and asks his father “What’s that?”. The reply is “That’s a flying groundnut scheme, son.” Milligan was a keen painter. Advertising In 1967, applying a satirical angle to a fashion for the inclusion of Superman-inspired characters in British television commercials, Milligan dressed up in a “Bat-Goons” outfit, to appear in a series of television commercials for British Petroleum. A contemporary reporter found the TV commercials “funny and effective”. From 1980 to 1982, he advertised for the English Tourist Board, playing a Scotsman on a visit around the different regions of England. Other advertising appearances included television commercials for Kellogg’s Corn Flakes, Commonwealth Bank of Australia, and Planter nuts. Other contributions In the 1970s, Charles Allen compiled a series of stories from British people’s experiences of life in the British Raj, called Plain Tales from the Raj, and published in 1975. Milligan was the youngest contributor, describing his life in India when it was under British rule. In it he mentions the imperial parades there: The most exciting sound for me was the sound of the Irregular Punjabi Regiment playing the dhol and surmai [ a type of drum] - one beat was dum-da-da-dum, dum-da-da-dum, dum-da-da-dum! They wore these great long pantaloons, a gold dome to their turbans, khaki shirts with banded waistcoats, double-cross bandoliers, leather sandals, and they used to march very fast, I remember, bursting in through the dust on the heels of an English regiment. They used to come in with trailed arms and they’d throw their rifles up into the air, catch it with their left hand - always to this dum-da-da-dum, dum-da-da-dum - and then stamp their feet and fire one round, synchronising with the drums. They’d go left, right, left, right, shabash! Hai! Bang! Dum-da-da-dum - It was sensational! Personal life Family Milligan married his first wife, June (Marchinie) Marlow, in 1952; Peter Sellers was best man. They had three children– Laura, Seán and Síle– and divorced in 1960. He had one daughter with his second wife, Patricia Ridgeway (known as Paddy): the actress Jane Milligan (b. 1966). Milligan and Patricia were married in June 1962 with George Martin as best man. The marriage ended with her death from breast cancer in 1978. In 1975 Milligan fathered a son, James (born June 1976), in an affair with Margaret Maughan. Another child, a daughter Romany, is suspected to have been born at the same time, to a Canadian journalist named Roberta Watt. His last wife was Shelagh Sinclair, to whom he was married from 1983 to his death on 27 February 2002. Four of his children collaborated with documentary makers on a new multi-platform programme called I Told You I Was Ill: The Life and Legacy of Spike Milligan (2005), which includes an accompanying website. In October 2008 an array of Milligan’s personal effects was sold at auction by his third wife, Shelagh, who was moving into a smaller home. These included a grand piano salvaged from a demolition and apparently played every morning by Paul McCartney, a neighbour in Rye in East Sussex. Shelagh Milligan died in June 2011. Health He suffered from severe bipolar disorder for most of his life, having at least ten serious mental breakdowns, several lasting over a year. He spoke candidly about his condition and its effect on his life: I have got so low that I have asked to be hospitalised and for deep narcosis (sleep). I cannot stand being awake. The pain is too much... Something has happened to me, this vital spark has stopped burning– I go to a dinner table now and I don’t say a word, just sit there like a dodo. Normally I am the centre of attention, keep the conversation going– so that is depressing in itself. It’s like another person taking over, very strange. The most important thing I say is 'good evening’ and then I go quiet. Nationality As Milligan was not born in the United Kingdom, his claim to British nationality was never clear. Milligan felt that he was entitled to a British passport, after having served in the army for six years. His passport application was refused, primarily because he would not swear an Oath of Allegiance; his Irish ancestry gave him an escape route from his stateless condition. He became an Irish citizen and remained so until his death. Humour with the Prince of Wales The Prince of Wales was a fan and when Milligan received the Lifetime Achievement Award at the British Comedy Awards in 1994, the Prince sent a congratulatory message to be read out on live TV. The comedian interrupted the message to call the Prince a “little grovelling bastard”. He later faxed the prince, saying “I suppose a knighthood is out of the question?” In reality he and the Prince were very close friends and Milligan had already been made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in 1992 (honorary because of his Irish citizenship). He was made an honorary Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire (KBE) in 2000. Campaigning He was a strident campaigner on environmental matters, particularly arguing against unnecessary noise, such as the use of “muzak”. In 1971, Milligan caused controversy by attacking an art exhibition, consisting of catfish oysters and shrimp which were to be electrocuted, at the Hayward Gallery with a hammer. He was a staunch and outspoken scourge of domestic violence, dedicating one of his books to Erin Pizzey. Death Even late in life, Milligan’s black humour had not deserted him. After the death of Harry Secombe from cancer, he said, “I’m glad he died before me, because I didn’t want him to sing at my funeral.” A recording of Secombe singing was played at Milligan’s memorial service. He also wrote his own obituary, in which he stated repeatedly that he “wrote the Goon Show and died”. Milligan died from kidney failure, at the age of 83, on 27 February 2002, at his home in Rye, Sussex. On the day of his funeral, 8 March 2002, his coffin was carried to St Thomas Church in Winchelsea, East Sussex, and was draped in the flag of Ireland. He had once quipped that he wanted his headstone to bear the words “I told you I was ill.” He was buried at St Thomas’ churchyard but the Chichester diocese refused to allow this epitaph. A compromise was reached with the Irish translation, Dúirt mé leat go raibh mé breoite and in English, “Love, light, peace”. The additional epitaph “Grá mór ort Shelagh” can be read as “Great love for you Shelagh”. According to a letter published in the Rye and Battle Observer in 2011, Milligan’s headstone was removed from St Thomas’ churchyard in Winchelsea and moved to be alongside the grave of his wife. Legacy From the 1960s, Milligan was a regular correspondent with Robert Graves. Milligan’s letters to Graves usually addressed a question to do with classical studies. The letters form part of Graves’s bequest to St. John’s College, Oxford. The film of Puckoon, starring Sean Hughes, including Milligan’s daughter, the actress Jane Milligan, was released after his death. Milligan lived for several years in Holden Road, Woodside Park, Finchley, at The Crescent, Barnet, and was a contributing founder and strong supporter of the Finchley Society. His old house in Woodside Park is now demolished but there is a blue plaque in his memory on the block of flats on the site. Over ten years the Finchley Society led by Barbara Warren raised funds– the Spike Milligan Statue Fund– to commission a statue of him cast in bronze by local sculptor John Somerville and erected in Finchley in the grounds of Avenue House in East End Road. The statue of Milligan sitting on a bench was unveiled on 4 September 2014 at a ceremony attended by a number of local dignitaries and showbusiness celebrities including Roy Hudd, Michael Parkinson, Maureen Lipman, Terry Gilliam, Kathy Lette, Denis Norden and Lynsey de Paul. There is a campaign to erect a statue in the London Borough of Lewisham where he grew up. After coming to the UK from India in the 1930s, he lived at 50 Riseldine Road, Brockley and attended Brownhill Boys’ School (later Catford Boys’ School, which was demolished in 1994). There is a plaque and bench located at the Wadestown Library, Wellington, New Zealand, in an area called “Spike Milligan Corner”. In a 2005 poll to find the Comedians’ Comedian, he was voted among the top 50 comedy acts, by fellow comedians and comedy insiders. In a BBC poll in August 1999, Milligan was voted the "funniest person of the last 1,000 years". Milligan has been portrayed twice in films. In the adaptation of his novel Adolf Hitler: My Part in His Downfall, he was played by Jim Dale, while Milligan played his father. He was portrayed by Edward Tudor-Pole in The Life and Death of Peter Sellers (2004). In a 2008 stage play, Surviving Spike, Milligan was played by the entertainer Michael Barrymore. On 9 June 2006, it was reported that Richard Wiseman had identified Milligan as the writer of the world’s funniest joke as decided by the Laughlab project. Wiseman said the joke contained all three elements of what makes a good gag: anxiety, a feeling of superiority and an element of surprise. Eddie Izzard described Milligan as “The Godfather of Alternative Comedy”. “From his unchained mind came forth ideas that just had no boundaries. And he influenced a new generation of comedians who came to be known as 'alternative’.” Members of Monty Python greatly admired him. In one interview, which was widely quoted at the time, John Cleese stated “Milligan is the Great God to all of us”. The Pythons gave Milligan a cameo role in their 1979 film, Monty Python’s Life of Brian, when Milligan happened to be holidaying in Tunisia, near where the film was being shot; he was re-visiting where he had been stationed during wartime. Graham Chapman gave him a minor part in Yellowbeard. After their retirement, Milligan’s parents and his younger brother Desmond moved to Australia. His mother lived the rest of her long life in the coastal village of Woy Woy on the New South Wales Central Coast, just north of Sydney. As a result, Milligan became a regular visitor to Australia and made a number of radio and TV programmes there, including The Idiot Weekly with Bobby Limb. He also wrote several books including Puckoon during a visit to his mother’s house in Woy Woy. Milligan named the town “the largest above ground cemetery in the world” when visiting in the 1960s. Milligan’s mother became an Australian citizen in 1985, partly in protest at her son’s no longer being eligible for British Citizenship, and he was reported at the time to be considering applying for Australian citizenship. The suspension bridge on the cyclepath from Woy Woy, New South Wales to Gosford was renamed the Spike Milligan Bridge in his memory, and a meeting room in the Woy Woy public library is also named after him. Collections (mostly poetry) * Silly Verse for Kids (poems) (1959) * A Book of Milliganimals (1968) * Values (poems) (1969) * Milligan’s Ark (1971) * Small Dreams of a Scorpion (poems) (1972) * Transports of Delight (1974) * Milligan Book of Records (1975) * Poems (poems) (1977) * Goblins (poems) (1978) * Open Heart University (poems) (1979) * Twelve Poems That Made December Colder (poems) (1979) * Unspun Socks from a Chicken’s Laundry (poems) (1981) * Chill Air (poems) (1981) * One Hundred and One Best and Only Limericks of Spike Milligan (poems) (1982) * Silly Verse for Kids and Animals (poems) (1984) * Floored Masterpieces with Worse Verse (poems) (1985) (with Tracey Boyd) * Further Transports of Delight (1985) * The Mirror Running (poems) (1987) * Startling Verse for All the Family (poems) (1987) * That’s Amazing (1988) * Condensed Animals (1991) * Hidden Words: Collected Poems (poems) (1993) * Fleas, Knees and Hidden Elephants (poems) (1994) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spike_Milligan

Nicholas Moore (16 November 1918 – 26 January 1986) was an English poet, associated with the New Apocalyptics in the 1940s, whose reputation stood as high as Dylan Thomas’s. He later dropped out of the literary world. Moore was born in Cambridge, England, the elder child of the philosopher G. E. Moore and Dorothy Ely. His paternal uncle was the poet, artist and critic Thomas Sturge Moore, and his brother was the composer Timothy Moore (1922-2003). He was educated at the Dragon School in Oxford, Leighton Park School in Reading, the University of St Andrews in Scotland, and Trinity College in Cambridge. Moore was editor and co-founder of a literary review, Seven (1938–40), while still an undergraduate. Seven, Magazine of People's Writing, had a complex later history: Moore edited it with John Goodland; it later appeared edited by Gordon Cruikshank, and then by Sydney D. Tremayne, after Randall Swingler bought it in 1941 from Philip O'Connor. While in Cambridge Moore became closely involved with literary London, in particular Tambimuttu. He published pamphlets under the Poetry London imprint in 1941 (of George Scurfield, G. S. Fraser, Anne Ridler and his own work). This led to Moore becoming Tambimuttu's assistant. Moore later worked for the Grey Walls Press. The Glass Tower, a selected poems collection from 1944, appeared with illustrations by the young Lucian Freud. In 1945 he edited The PL Book of Modern American Short Stories, and won Contemporary Poetry's Patron Prize (judged that year by W. H. Auden) for Girl with a Wine Glass. In 1947 he won the Harriet Monroe Memorial Prize for Girls and Birds and various other poems. Later Moore encountered difficulty in publishing; he was in the unusual position for a British poet of having a higher reputation in the USA. His association with the "romantics" of the 1940s was, in fact, rather an inaccurate reflection of his style. In the 1950s he worked as a horticulturist, writing a book The Tall Bearded Iris (1956). In 1968 he entered 31 separate pseudonymous translations of a single Baudelaire poem, in a competition for the Sunday Times, run by George Steiner. Each translation focused on a different element of the poem: rhyme, pattern, tropes, symbolism, etc. producing vastly different results, to illustrate the inadequacies and lacunae produced in translation. This work was published in 1973 as Spleen; it is also available online. Longings of the Acrobats, a selected poems volume, was edited by Peter Riley and published in 1990 by Carcanet Press. An interview with Riley concerning Moore's rediscovery and later years appears as a documentary element within the "Guilty River" chapter of Iain Sinclair's novel Downriver. According to Riley, Moore was extremely prolific and left behind many unpublished poems. An example of one of Moore's "pomenvylopes" – idiosyncratic documents consisting of poems and comments typed onto envelopes and posted to friends and acquaintances – appears online at The Fortnightly Review. His Selected Poems was published by Shoestring Press in 2014. Bibliography * A Wish in Season (1941) * The Island and the Cattle (1941) * A Book for Priscilla (1941) * Buzzing around with a Bee (1941) * The Cabaret, the Dancer, the Gentlemen (1942) * The Glass Tower (1944) * Thirty-Five Anonymous Odes (published anonymously, 1944) * The War of the Little Jersey Cows (published under the pseudonym "Guy Kelly", 1945) * The Anonymous Elegies and other poems (published anonymously, 1945) * Recollections of the Gala: Selected Poems 1943-48 (1950) * The Tall Bearded Iris (1956) * Anxious To Please (1968) (published under the pseudonym (anagram) "Romeo Anschilo", 1995 by Oasis Books) * Identity (1969) * Resolution and Identity (1970) * Spleen (1973) * Lacrimae Rerum (1988) * Longings of the Acrobats: Selected Poems (1990) * The Orange Bed (2011) References Wikipedia—http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nicholas_Moore

Sir Andrew Motion FRSL (born 26 October 1952) is an English poet, novelist, and biographer, who was Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom from 1999 to 2009. During the period of his laureateship, Motion founded the Poetry Archive, an online resource of poems and audio recordings of poets reading their own work. In 2012, he became President of the Campaign to Protect Rural England, taking over from Bill Bryson. Early life Motion was born on 26 October 1952 in London; his mother was Catherine Gillian Bakewell (known as Gillian) and his father Andrew Richard Michael Motion (known as Richard). The family moved to Stisted, near Braintree in Essex, when Motion was 12 years old. Motion went to boarding school from the age of seven joined by his younger brother. Most of the boy’s friends were from the school and when Motion was in the village he spent a lot of time on his own. He began to have an interest and affection for the countryside and he went for walks with a pet dog. Later he went to Radley College, where, in the sixth form, he encountered Peter Way, an inspiring English teacher who introduced him to poetry– first Hardy, then Philip Larkin, W. H. Auden, Heaney, Hughes, Wordsworth and Keats. When Motion was 17 years old, his mother had a horse riding accident and suffered a serious head injury requiring a life-saving neurosurgery operation. She regained some speech, but she was severely paralysed and remained in and out of coma for nine years. She died in 1978 and her husband died of cancer in 2006. Motion has said that he wrote to keep his memory of his mother alive and that she was a muse of his work. When Motion was about 18 years old he moved away from the village to study English at University College, Oxford; however, since then he has remained in contact with the village to visit the church graveyard, where his parents are buried, and also to see his brother, who lives nearby. At University he studied at weekly sessions with W. H. Auden, whom he greatly admired. Motion won the university’s Newdigate Prize and graduated with a first class honours degree. Career Between 1976 and 1980, Motion taught English at the University of Hull and while there, at age 24, he had his first volume of poetry published. At Hull he met university librarian and poet Philip Larkin. Motion was later appointed as one of Larkin’s literary executors which would privilege Motion’s role as his biographer following Larkin’s death in 1985. In Philip Larkin: A Writer’s Life, Motion says that at no time during their nine-year friendship did they discuss writing his biography and it was Larkin’s longtime companion Monica Jones who requested it. He reports how, as executor, he rescued many of Larkin’s papers from imminent destruction following his friend’s death. His 1993 biography of Larkin, which won the Whitbread Prize for Biography, was responsible for bringing about a substantial revision of Larkin’s reputation. Motion was Editorial Director and Poetry Editor at Chatto & Windus (1983–89), he edited the Poetry Society’s Poetry Review from 1980–1982 and succeeded Malcolm Bradbury as Professor of Creative Writing at the University of East Anglia. He is now on the faculty at the Johns Hopkins Writing Seminars. Laureateship Motion was appointed Poet Laureate on 1 May 1999, following the death of Ted Hughes, the previous incumbent. The Nobel Prize-winning Northern Irish poet and translator Seamus Heaney had ruled himself out for the post. Breaking with the tradition of the laureate retaining the post for life, Motion stipulated that he would stay for only ten years. The yearly stipend of £200 was increased to £5,000 and he received the customary butt of sack. He wanted to write “poems about things in the news, and commissions from people or organisations involved with ordinary life,” rather than be seen a 'courtier’. So, he wrote "for the TUC about liberty, about homelessness for the Salvation Army, about bullying for ChildLine, about the foot and mouth outbreak for the Today programme, about the Paddington rail disaster, the 11 September attacks and Harry Patch for the BBC, and more recently about shell shock for the charity Combat Stress, and climate change for the song cycle he finished for Cambridge University with Peter Maxwell Davies.” On 14 March 2002, as part of the 'Re-weaving Rainbows’ event of National Science Week 2002, Motion unveiled a blue plaque on the front wall of 28 St Thomas Street, Southwark, to commemorate the sharing of lodgings there by John Keats and Henry Stephens while they were medical students at Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital in 1815–16. In 2003, Motion wrote Regime change, a poem in protest at Invasion of Iraq from the point of view of Death walking the streets during the conflict, and in 2005, Spring Wedding in honour of the wedding of the Prince of Wales to Camilla Parker Bowles. Commissioned to write in the honour of 109-year-old Harry Patch, the last surviving “Tommy” to have fought in World War I, Motion composed a five-part poem, read and received by Patch at the Bishop’s Palace in Wells in 2008. As laureate, he also founded the Poetry Archive, an on-line library of historic and contemporary recordings of poets reciting their own work. Motion remarked that he found some of the duties attendant to the post of poet laureate difficult and onerous and that the appointment had been "very, very damaging to [his] work". The appointment of Motion met with criticism from some quarters. As he prepared to stand down from the job, Motion published an article in The Guardian that concluded, "To have had 10 years working as laureate has been remarkable. Sometimes it’s been remarkably difficult, the laureate has to take a lot of flak, one way or another. More often it has been remarkably fulfilling. I’m glad I did it, and I’m glad I’m giving it up– especially since I mean to continue working for poetry." Motion spent his last day as Poet Laureate holding a creative writing class at his alma mater, Radley College, before giving a poetry reading and thanking Peter Way, the man who taught him English at Radley, for making him who he was. Carol Ann Duffy succeeded him as Poet Laureate on 1 May 2009. Post-laureateship Motion is Chairman of the Arts Council of England’s Literature Panel (appointed 1996) and is also a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. In 2003, he became Professor of Creative Writing at Royal Holloway, University of London. Since July 2009, Motion has been Chairman of the Museums, Libraries and Archives Council (MLA) appointed by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport. He is also a Vice-President of the Friends of the British Library, a charity which provides funding support to the British Library. He was knighted in the 2009 Queen’s Birthday Honours list. He has been a member of English Heritage’s Blue Plaques Panel since 2008. Motion was selected as jury chair for the Man Booker Prize 2010 and in March 2010, he announced that he was working with publishers Jonathan Cape on a sequel to Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island. Entitled Silver, the story is set a generation on from the original book and was published in March 2012. In July 2010, Motion returned to Kingston-upon-Hull for the annual Humber Mouth literature festival and taking part in the Larkin 25 festival commemorating the 25th anniversary of Philip Larkin’s death. In his capacity as Larkin’s biographer and as a former lecturer in English at the University of Hull, Motion named an East Yorkshire Motor Services bus Philip Larkin. Motion’s debut play Incoming, about the war in Afghanistan, premièred at the High Tides Festival in Halesworth, Suffolk in May 2011. Motion also featured in Jamie’s Dream School in 2011 as the poetry teacher. In June 2012, he became the President of the Campaign to Protect Rural England. In March 2014 he was elected an Honorary Fellow at Homerton College, Cambridge. Motion won the 2015 Ted Hughes Award for new work in poetry for the radio programme Coming Home. The production featured poetry by Motion based on recordings he made of British soldiers returning from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Work Motion has said of himself: “My wish to write a poem is inseparable from my wish to explain something to myself.” His work combines lyrical and narrative aspects in a “postmodern-romantic sensibility”. Motion says that he aims to write in clear language without tricks. The Independent describes the stalwart poet as the “charming and tireless defender of the art form”. Motion has won the Arvon Prize, the John Llewellyn Rhys Prize, Eric Gregory Award, Whitbread Prize for Biography and the Dylan Thomas Prize. Motion took part in the Bush Theatre’s 2011 project Sixty-Six Books, writing and performing a piece based upon a book of the King James Bible. Personal life Motion’s marriage to Joanna Powell ended in 1983. He was married to Jan Dalley from 1985 to 2009, divorcing after a seven-year separation. They had one son born in 1986 and twins, a son and a daughter, born in 1988. In 2009 he married Kyeong-Soo Kim. They live in Baltimore, Maryland. Selected honours and awards 1975: won the Newdigate prize for Oxford undergraduate poetry 1976: Eric Gregory Award 1981: wins Arvon Foundation’s International Poetry Competition with The Letter 1984: John Llewellyn Rhys Prize for Dangerous Play: Poems 1974–1984 1986: Somerset Maugham Award for The Lamberts 1987: Dylan Thomas Prize for Natural Causes 1999: appointed Poet Laureate for ten years 1994: Philip Larkin: A Writer’s Life, Whitbread Prize for Biography 2009: Knighthood 2014: Wilfred Owen Poetry Award Selected works Poetry collections * 1972: Goodnestone: a sequence. Workshop Press * 1976: Inland. Cygnet Press * 1977: The Pleasure Steamers. Carcanet * 1981: Independence. Salamander Press * 1983: Secret Narratives. Salamander Press * 1984: Dangerous Play: Poems 1974–1984. Salamander Press / Penguin * 1987: Natural Causes. Chatto & Windus * 1988: Two Poems. Words Ltd * 1991: Love in a Life. Faber and Faber * 1994: The Price of Everything. Faber and Faber * 1997: Salt Water Faber and Faber * 1998: Selected Poems 1976–1997. Faber and Faber * 2001: A Long Story. The Old School Press * 2002: Public Property. Faber and Faber * 2009: The Cinder Path. Faber and Faber * 2012: The Customs House. Faber and Faber * 2015: Peace Talks. Faber and Faber * 2015: Coming Home. Published by Andrew J Moorhouse at Fine Press Poetry http://www.finepresspoetry.com Criticism * 1980: The Poetry of Edward Thomas. Routledge & Kegan Paul * 1982: Philip Larkin. (Contemporary Writers series) Methuen * 1986: Elizabeth Bishop. (Chatterton Lectures on an English Poet) * 1998: Sarah Raphael: Strip!. Marlborough Fine Art (London) * 2008: Ways of Life: On Places, Painters and Poets. Faber and Faber Biography and memoir * 1986: The Lamberts: George, Constant and Kit. Chatto & Windus * 1993: Philip Larkin: A Writer’s Life. Faber and Faber * 1997: Keats: A Biography. Faber and Faber * 2006: In the Blood: A Memoir of my Childhood. Faber and Faber Fiction * 1989: The Pale Companion. Penguin * 1991: Famous for the Creatures. Viking * 2003: The Invention of Dr Cake. Faber and Faber * 2000: Wainewright the Poisoner: The Confessions of Thomas Griffiths Wainewright (biographical novel) * 2012: Silver. Jonathan Cape Edited works, introductions, and forewords * 1981: Selected Poems: William Barnes. Penguin Classics * 1982: The Penguin Book of Contemporary British Poetry with Blake Morrison. Penguin * 1994: Thomas Hardy: Selected Poems. Dent * 1993: New Writing 2 (With Malcolm Bradbury). Minerva in association with the British Council * 1994: New Writing 3 (With Candice Rodd). Minerva in association with the British Council * 1997: Penguin Modern Poets: Volume 11 with Michael Donaghy and Hugo Williams. Penguin * 1998: Take 20: New Writing. University of East Anglia * 1999: Verses of the Poets Laureate: From John Dryden to Andrew Motion. With Hilary Laurie. Orion. * 1999: Babel: New Writing by the University of East Anglia’s MA Writers. University of East Anglia. * 2001: Firsthand: The New Anthology of Creative Writing from the University of East Anglia. University of East Anglia * 2002: Paper Scissors Stone: New Writing from the MA in Creative Writing at UEA. University of East Anglia. * 2001: The Creative Writing Coursebook: Forty Authors Share Advice and Exercises for Fiction & Poetry. With Julia Bell. Macmillan * 2000: John Keats: Poems Selected by Andrew Motion. Faber and Faber * 2001: Here to Eternity: An Anthology of Poetry. Faber and Faber * 2002: The Mays Literary Anthology; Guest editor. Varsity Publications * 2003: 101 Poems Against War . Faber and Faber (Afterword) * 2003: First World War Poems. Faber and Faber * 2006: Collins Rhyming Dictionary. Collins * 2007: Bedford Square 2: New Writing from the Royal Holloway Creative Writing Programme. John Murray Ltd. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrew_Motion

ABOUT THE AUTHOR Nthikeng Daniel Madileng was born in 1992 march 18th at Regae, vandermerweskraal in the Limpopo province. He was raised by his single mother and a grandmother under a strictly traditional and a Christian circle. Nthikeng is the first born of Selies Madileng, and a third born of Johannes Rapetsoa. His father had two daughters just before Nthikeng was born. Due to family problems, Nthikeng had to grow under the support of his late grandmother Sophie who was a pensioner and a grandmother to eleven children. As a brother Nthikeng chose school over all of the opportunities of life, he went to Regae primary school at the age of 6 until the age of 12. At the age of 13 until the age of 17 he was in high school where he passed with a bachelor NSC certificate under the science stream. At the age of 18 Nthikeng went to the University of Pretoria where he studied Chemical engineering extended curriculum. He then relocated to Polokwane where he continued with his studies. Writing He started writing at age ten and spent many years learning under Majatladi High school and Tshwane university of Technology drama and entertainment programs. His writing and poetry have been featured in many exhibitions and festivals around Limpopo and Gauteng province, where he was awarded Best poet of the Show. He has exhibited his work in high school events, university events such as fresher’s ball and YFE programme, political events, and cultural centers throughout Limpopo and Gauteng province. In his work Nthikeng often uses real life ideas combined with emotional poetry techniques. Nthikeng is currently extending his knowledge by teaching young passionate kids to express their feelings through the language of poetry. He continues to explore new ways to share his mind and the background of his life.

Charles Mair (September 21, 1838– July 7, 1927) was a Canadian poet and journalist. He was a fervent Canadian nationalist noted for his participation in the Canada First movement and his opposition to Louis Riel during the two Riel Rebellions in western Canada. Life Mair was born at Lanark, Upper Canada, to Margaret Holmes and James Mair. He attended Queen’s University but did not graduate. On leaving college, he became a journalist. In Ottawa in 1868, Mair was introduced by civil servant and writer Henry Morgan to young lawyers George Denison, William Foster, and Robert Haliburton. “Together they organized the overtly nationalistic Canada First movement, which began as a small social group.” Mair “represented the Montreal Gazette during the first Riel Rebellion, and was imprisoned and narrowly escaped being shot by the rebels.” Mair was a Freemason Mair "was an Officer of the Governor-General’s Body Guard during the second Riel rebellion in 1885, and was later employed in the Canadian civil service in the West." He died in Victoria, British Columbia. Writing Mair published the first book of poetry in post-Confederation Canada, 1868's Dreamland and Other Poems. “Negligible as verse,” says The Canadian Encyclopedia, "the volume gained interest when Mair escaped after being captured by Louis Riel during the Red River disturbances of 1869-70.” The Dictionary of Canadian Biography (DCB) states that Dreamland “demonstrates a conventional colonial approach to poetry. Such poems as 'August’ succeed in their attention to natural detail: descriptions of the blueflies, the milkmaids, and the 'ribby-lean’ cattle in parched fields anticipate the mature nature poetry of Archibald Lampman. But too often he wrote not of the timberlands he knew but of a dreamland weakly modelled upon the romantic flights of Keats.” However, the book was praised by “the established poet Charles Sangster, who referred to Canada’s sophisticated literary tradition as one that was habitually overlooked in the popular press.” Writing later in the Ottawa Journal, William Wilfred Campbell saw Dreamland as a precursor to the nature poetry later popularized in Canada by the Confederation Poets: “The thirty-three poems constitute the first attempt to deal with Canadian nature, in the manner of Keats and the other classic poets, and many of them in theme and treatment are similar to the verse of Lampman and Roberts.... And there are strong evidences in Mair’s work that he influenced these poets to a great extent.” Mair published Tecumseh, a historical drama mainly in blank verse dealing with the War of 1812, in 1886. Canadian critic Alan Filewood wrote of the political and philosophical ideas expressed by Mair in the poem: Mair’s projection of Canadian nationhood is embodied in the character of Lefroy, a Byronesque poet who flees civilization to seek solace in nature’s genius. He learns– tragically– from the British General Brock that natural law finds its outward form in the monarchic principle, and from the Indian chieftain Tecumseh that nature must be defended against the perversion of American materialism. The dying Tecumseh legitimizes the proto-(Anglo) Canadians as the natural guardians of the land, and Canadian manhood finds mature expression in a race of armed poets.(...) Mair looked to the day when the dominions would assume the responsibilities of adulthood: Then shall a whole family of young giants stand 'Erect, unbound, at Britain’s side-' her imperial offspring oversea, the upholders in the far future of her glorious tradition, or, should exhaustion ever come, the props and supports of her declining years. The DCB calls Tecumseh "a major contribution to our 19th-century literary heritage, wherein the War of 1812 is the central event of Canadian history. Among the many literary treatments of this war, including works by Sangster, John Richardson, and Sarah Anne Curzon... Tecumseh stands as the most accomplished." The Canadian Encyclopedia says that the poem’s “blank verse is pedestrian and untheatrical”, but it also tells us that “Tecumseh was important in the development of Canadian drama. It presents a vision of Canada as a co-operative enterprise in contrast with the self-seeking individualism of the United States.” Recognition Mair was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada in 1889. In 1937 he was designated a Person of National Historic Significance. Canadian folksinger Gordon Lightfoot adapted a line from Tecumseh, “There was a time on this fair continent,” for the first line in his 1967 historical ballad, “The Canadian Railroad Trilogy” ("There was a time in this fair land when the railroad did not run"). Publications * Dreamland and Other Poems. London: S. Low, 1868. Montreal: Dawson, 1868, * Tecumseh. Toronto: Hunter, Rose & Co., 1886. London: Chapman & Hall, 1886. * Through the Mackenzie Basin: A Narrative of the Athabasca and Peace River Treaty Expedition of 1899 . London: Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co., 1903. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Mair

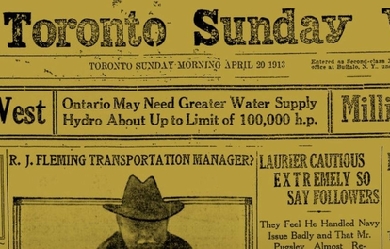

In a very real sense Miss Laura Elizabeth McCully is a Toronto writer, as, with the exception of one academic year in the United States and a few months in Ottawa, she has lived all her life in this city. She is a grand niece of the late Hon. John McCully, of Truro, Nova Scotia, one of the Fathers of Confederation; and is the daughter of Samuel Edward McCully, M.D., and Helen (Fitzgibbon) McCully. Her father is of Manx descent, and her mother is a descendant of the late James McBride of Halton county, Ontario, magistrate, who was one of the pioneers of this province, and who heroically cleared off forest and left to his heirs, one thousand acres of valuable farm lands. Miss McCully's poetry is enriched by classical illustrations, and expressed in forceful and melodious language. Her imagination relates us to the universe and to humanity. Wordsworth found new lessons in the fields and woods, and taught them; Lanier made trees, flowers and clouds our intimate friends; when we read Miss McCully's nature poems we are not conscious of the moralizing of the poet, we are in the glens ourselves looking at the afterglow, with the purity, the glory, the growth spirit and the transforming beauty of nature flowing into our lives. In a few flaming lines her stories reveal the love, the despair, and the ultimately triumphant faith of humanity. With tender pathos she unveils the evils of social and industrial conditions, and in clear tones arouses each soul, and makes it conscious of the splendour of the better conditions ahead, and thrills it with the determination to achieve for justice, freedom, and truth. – JAMES L. HUGHES, LL. D.

Welcome!! "MY POEM ATTIC" It's a passion which blooms from within ourselves. For me it's just like a river flowing once when my pen touches the paper. Your inner feelings, your character, personality , your surroundings .. ..everything gets visible through my writings. Observant and a warm loving heart who had experienced life deeply knowing the essence of poetry writing. Fall in love with my harmonious poems...Make urself feel light and heavenly.. Sit back and relax!! ~~~Keerthi Krishna M~~~

Mahathi is a renowned Indian English poet. So far 6 anthologies of his original poems were published. His 6th book, FINDING THE MOTHER, a trans-creation of SRI SUNDARA KANDA , the 5th canto of Srimad RAMAYANA was critically acclaimed as one of the greatest epic works of modern English poetry. His poetry is known for its great imagery, clear diction, solemn expression and scintillating narration, often laced with fun, pun and satire. Mahathi being a strong protagonist of classical poetic forms of Elizabethan era, naturally his verses have the sublimity of classical accent and flow with lyrical grace. A few of his book reviews, forewords to books of other authors and a couple of articles in prose were also published.

Born in the west of Ireland in the economic vacuum that followed WW2 Grew up on Beatles Mohammad Ali Worried about the troubles and sustainable farming Studied agriculture instead of English I feel my roots are Viking and would like to see Norway as well as California . My interest in farming has led me to supply a vast range of farm machinery parts. I am married to Karen and we have two daughters and a son I am dedicated to Gaelic football which is like a friend factory My ambition along with seeing Norway and California is to climb Kilamanjario and publish my poems

About Me: Please leave a comment on my poetry and stories thank you Blessed Be 37, Mother of 2 gorgeous daughters 13 n 10, Found my high school sweetheart after 15 years and now we celebrated our 1yr anniversary aug-27-13. Ill never let him go no matter what. I Love writing poetry and short stories. Its my way to relieve my over stuffed mind that is always stuck on play. I write because that is the only way I know how to express myself. I'm horrible talking face to face because of my Social Anxiety. I hate it but i have friends and family who love me and help me thru it. My Hobbies: Horseback riding,biking,roller skating, coloring,taking walks,writing poetry and more My Achievements: People in our life are not strangers just friends we haven't met yet :-) Please add me toYOUR favorites and a friend.. as i will be happy to do the same :-) Blessed Be Published In Pocono Record: Eastern Pocono Community News *Your Page: *So High And Free -January-26-2001 *The Day YouBEGIN To Live..June-8-2001 Awards:-------------------------------------------------------- *Poetry.com: & the International Library of Poetry: Awarded Prestigious Editor's Choice Award, >Outstanding Achievement in Poetry: *VIP# P6125073- Rain- 2004 *VIP# P612507- You're- June 2005 *VIP#P1854496- The Day You Begin To Live -December 2000 Awaking To Sunshine (book- Natures of Echoes) *Award of MeritCERTIFICATE : from John Campbell: Editor & Publisher, Eddie-Lou Cole : Poetry Editor, Rank Honorable Mention In Appreciation December-15-1991 World of Poetry: *Winter Is