Octavio Paz (Ciudad de México, 31 de marzo de 1914 – Ibidem, 19 de abril de 1998), registrado al nacer como Octavio Irineo Paz Lozano, fue un poeta, ensayista y diplomático mexicano. Obtuvo el Premio Nobel de Literatura en 1990 y el Premio Cervantes en 1981. Se le considera uno de los más influyentes autores del siglo xx y uno de los más grandes poetas de todos los tiempos.

#Mexicanos #PremioCervantes #PremioNobel #SigloXX

Flora Alejandra Pizarnik (Avellaneda, 29 de abril de 1936 – Buenos Aires, 25 de septiembre de 1972) fue una poetisa, ensayista y traductora argentina. Estudió filosofía y Letras en la Universidad de Buenos Aires y pintura con Juan Batlle Planas. Entre 1960 y 1964, Pizarnik vivió en París, donde trabajó para la revista Cuadernos y algunas editoriales francesas, publicó poemas y críticas en varios diarios y tradujo a Antonin Artaud, Henri Michaux, Aimé Césaire e Yves Bonnefoy. Además, estudió historia de la religión y literatura francesa en La Sorbona. Tras su retorno a Buenos Aires, Pizarnik publicó tres de sus principales volúmenes: Los trabajos y las noches, Extracción de la piedra de locura y El infierno musical, así como su trabajo en prosa La condesa sangrienta.

#Argentinos #Mujeres #SigloXX #Suicidio

Rafael Pombo, (Bogotá, República de Nueva Granada, 7 de noviembre de 1833 – Bogotá, Colombia, 5 de mayo de 1924), fue un poeta, escritor, fabulista, traductor, intelectual y diplomático colombiano. Sus padres fueron Lino de Pombo O'Donnell y Ana María Rebolledo, ambos pertenecientes a familias de la aristocracia de Popayán. Cuando el General Francisco de Paula Santander designó a Lino de Pombo como secretario del Interior y de Relaciones Exteriores, éste aceptó y viajó desde Popayán con su familia a Bogotá. Cuando la familia llegó a Bogotá, Ana María Rebolledo tenía 9 meses de embarazo, por lo que poco después dio a luz a su primogénito José Rafael de Pombo Rebolledo.

#Colombianos #ParaNiños #SigloXIX

Nació en Buenos Aires el 18 de enero de 1960. Es licenciada en Letras por la Universidad de Buenos Aires, periodista, docente y editora. Ha publicado La Fiesta del Ser, poemas, (Ed. Vinciguerra,1994), premiado en 1995 por la Sociedad Argentina de Escritores. En 1996 una selección de sus poemas apareció en la antología Poesía Argentina de Fin de Siglo. En Patagonia Rumbo Sur (Ed. Vinciguerra, 1998), poemario bilingüe español-inglés ilustrado fotográficamente por Chacho Rodríguez Muñoz, realiza un viaje intemporal a través de la inmensidad patagónica, donde los temas surgen de ese espacio sólo en apariencia vacío, poblado por incontables voces que el viento guarda. En 1999, año del centenario del nacimiento de Jorge Luis Borges, publicó miBorges.com Poema en Nueve Cantos (Ed. Vinciguerra), un homenaje a la monumental huella que el gran poeta dejó en su escritura; obra que apareció conjuntamente en formato libro y en internet, en el sitio www.miborges.com.ar Ejerciendo el periodismo cultural, despliega el género de la entrevista con la gran versatilidad devenida de las dos vertientes que convergen en ella: la literatura y la gráfica. Paralelamente, sus poemas son editados en diversas revistas y publicaciones literarias de la Argentina, América Latina y Portugal. Ese año de 1999 publicó también la investigación periodística Un argentino llamado Mosconi. Un siglo de petróleo en la Argentina y la historia del hombre que lo convirtió en un instrumento para el desarrollo de la Nación , con prólogo de María Esther de Miguel. En 2002 editó Mascarón de proa, poemas (Ed. Edivérn), con prólogo de María Rosa Lojo. En Poemas 2003 publicó una selección de los libros inéditos Materia prima e Intemperies, en Summa poética II (Ed. Vinciguerra, 2004). En 2007 formó parte de la antología Poesía Argentina Contemporánea realizada por la Fundación Argentina para la Poesía, FAP. Al año siguiente, esta misma institución le otorgó el Premio Puma de Plata por su labor periodística en difusión de la poesía. A fines de 2010 editó Aquí no duele -50 poemas– (Ed. Vinciguerra). En 2016 apareció Calle Charcas. Poemas de barbarie para leer escuchando Summertime de George Gershwin, en Summa Poética - Vinciguerra 30° Aniversario, Caja estuche con la participación de 25 poemarios de 25 poetas (Ed. Vinciguerra, 2016). Desde 2013 y hasta fines de 2017 dirigió talleres de “Abordajes Poéticos” para la FAP en la Sociedad Argentina de Escritores y condujo luego la experiencia pionera de un programa en vivo online de taller de lectoescritura visual y radial para esta misma institución señera de la poesía en la Argentina. En agosto de 2017, tres poemas inéditos en libros fueron publicados entre las págs. 84/85, en el N° 137 de la prestigiosa revista de literatura Hispamérica, una de las más importantes publicaciones de referencia del latinoamericanismo académico internacional, realizada, creada y editada desde 1972 por Saúl Sosnowski, Dr. en Letras y catedrático de la Universidad de Maryland, Estados Unidos. En 2020 participó en la antología 24 poetas mujeres hoy II (Ed. Imaginante). En abril de 2021, Imprex Ediciones publicó El gato de Rodas y otros santuarios desolados, poemas. En diciembre de 2021, Ed. Vinciguerra editó Aviso para caminantes (poemas de pandemia y otros) . http://abordajespoeticos.blogspot.com.ar/ https://www.amazon.com/dp/B09RTLWJ5T https://miborgescom.blogspot.com/2019/04/introduccion.html?spref=twhttp://miborgescom.blogspot.com/2019/04/historia-de-una-foto.html

Arturo Borja Pérez, (n. Quito, 1892 - f. Ibídem, 13 de noviembre de 1912) fue un poeta ecuatoriano, perteneciente al movimiento llamado “La Generación Decapitada” y el primero del grupo en despuntar como modernista. Es muy escasa su obra artística pero suficiente para determinar la calidad de poeta: una corona de veinte composiciones forma el libro titulado La flauta de ónix, y seis poemas más; obras que fueron publicadas póstumamente. Se suicidó en la ciudad de Quito, el 13 de noviembre de 1912, contando apenas con 20 años de edad. Ofrenda de rosas (A Arturo Borja) Recuerdo que te hallé por mi camino como un Verlaine aún adolescente, ¡y daba el signo de un fatal destino tu alma de estirpe lírica y ardiente! Y ambos fraternizamos; que tus rosas para todas las almas entreabrías, ¡haciéndote en las horas humildosas dueño de todas las melancolías...! Quién volviera a tus ojos, en ofrenda, la vida humilde que suspira y canta, como el Rubí de manos de leyenda que antaño dijo a Lázaro: ¡Levanta! Evoco el sueño juvenil de un día que, en el Claustro del Arte bien sentido, matamos la viril hipocrecía, y laboramos lentos el gemido. Y ahora la luna de tu sistro agrestre, al visitar nuestro santurario frío, da su color de lágrima celeste en el cristal de tu crisol vacío... ¡Adiós, fuente de lánguido quebranto!, que volvías un Fénix mi rosal, ¡encantando las rosas sin encanto cuando el encanto huía con el mal! ¡Adiós, fuente de lágrimas cantoras que halagaron el viaje juvenil!; de la angustia de Abril refrescadoras como lluvias caídas en Abril... Duerme y reposa; que quizás es bueno sólo el sueño sin sueño en que caíste, ¡la flor de espino y el laurel de heleno entremezclados en tu frente triste! —Humberto Fierro Feliz tú, hermano mío (Al espíritu fraternal de Arturo Borja) Poeta, hermano mío, que como yo sufriste, el frío del vacío y la grandeza triste de saberte una nube en prisión de rocío; tu buen hermano en lira, en rosa, azul y luna que inspira la mentira de la verde laguna, sabe envidiar tu suerte porque tu suerte admira. Lloro tu vida breve por lo que dado hubieras, pero la leve nieve de tus quimeras en nube se transforma y desde lo alto llueve. Poeta, hermano mío, ya no estarás más triste, ni el frío del vacío sentirás que sentiste... Ya no eres una nube encerrada en rocío; después de que partiste tu lluvia se hizo un río que da savia a tu rosa y a tu bulbul alpiste... ¡Feliz tú, hermano mío! —Alejandro Sux

#Ecuatorianos #GeneraciónDecapitada #LaGeneraciónDecapitada #SigloXX #Suicidio

José Emilio Pacheco (Ciudad de México, 30 de junio de 1939 - Ib., 26 de enero de 2014) fue un destacado escritor mexicano principalmente por su poesía, aunque cultivó con éxito también la crónica, la novela, el cuento, el ensayo y la traducción. Se le considera integrante de la llamada generación de los cincuenta o de medio siglo. Comparte la perspectiva cosmopolita que caracteriza a los literatos de esa generación, y los temas que aborda en sus textos van desde la historia y el tiempo cíclico, los universos de la infancia y de lo fantástico, hasta la ciudad y la muerte. La escritura de Pacheco se distingue por un constante cuestionamiento sobre la vida en el mundo moderno, sobre la literatura y su propia producción artística, así como por el uso de un lenguaje sin rebuscamientos, accesible.

Carezco de malos hábitos a excepción de: 1.-Morir de noche, cuando me siento solo y desgraciado 2.-Empezar un sol sin terminar una estrella 3.-Fumar el opio de mis malas ideas 4.-Reciclarte dentro de mis sueños para que después no te pierda 5.-Animar a los demonios a entrar en mi alma 6.-Calmar mi sed con la sangre que se derrama 7.-Añorar un beso que me costaría el alama 8.-Suplicar por más sabiendo que nada me han dado 9.-Pertenecer a un ser que no tubo el derecho de nacer 10.-Escribir estupideces con tal de ver el sol con los ojos secos cada nuevo amanecer. Seguiría mi lista pero el tiempo se acaba, el sol que comencé a crear derrama ríos de lava y no quiero que mate a los demonios que van a entrar en mi alma, ellos tienen mejor opio que el mio, y no suplican, no lloran, no mueren de noche, ellos no escriben estupideces, ellos lloran como lo debería de hacer yo.

Carlos Pellicer Cámara (San Juan Bautista, Villahermosa, Tabasco, 16 de enero de 1897-Ciudad de México; 16 de febrero de 1977) fue un escritor, poeta, museógrafo y político mexicano, quien fuera senador por Tabasco desde el 1 de septiembre de 1976 hasta el día de su muerte. Inició sus estudios en la escuela primaria Daría González. La revolución mexicana lo contagió de su ímpetu. Los aviones lo hicieron soñar con ser piloto civil, pero desde muy temprana edad descubrió su vena poética y la convicción de llegar a ser alguien importante.

#Mexicanos #Modernismo #SigloXX #Vanguardismo

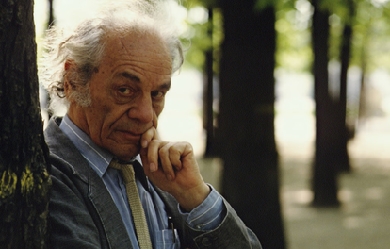

Nicanor Segundo Parra Sandoval (San Fabián de Alico, 5 de septiembre de 1914 – La Reina, Santiago, 23 de enero de 2018) fue un poeta, profesor, físico e intelectual chileno cuya obra ha tenido una profunda influencia en la literatura hispanoamericana. Considerado el creador de la antipoesía, es para muchos críticos y autores connotados, tales como Harold Bloom, Niall Binns o Roberto Bolaño, uno de los mejores poetas de Occidente. El mayor de la familia Parra, recibió el Premio Nacional de Literatura (1969) y el Premio Miguel de Cervantes (2011).

Heberto Padilla (Puerta del Golpe, Pinar del Río, 20 de enero de 1932 – Alabama, Estados Unidos, 24 de septiembre de 2000) fue un poeta y activista cubano, perseguido por el gobierno de la República de Cuba. En 1966 se convirtió en centro de una polémica cultural en las páginas de Juventud Rebelde, a pesar de lo cual obtuvo el Premio Nacional de Poesía por Fuera del juego, lo que motivó las protestas de la Unión de Escritores ya que el libro era considerado contrarrevolucionario. En 1967 comienza a trabajar en la Universidad de La Habana hasta que el 20 de marzo de 1971 es detenido a raíz del recital de poesía dado en la Unión de Escritores, donde leyó Provocaciones. Padilla fue arrestado junto con la poetisa Belkis Cuza Malé, su esposa desde 1967. Ambos fueron acusados por el Departamento de Seguridad del Estado de “actividades subversivas” contra el gobierno. Su encarcelamiento provocó una reacción en todo el mundo, con las consiguientes protestas de conocidísimos intelectuales entre los que figuraban Julio Cortázar, Simone de Beauvoir, Marguerite Duras, Carlos Fuentes, Juan Goytisolo, Alberto Moravia, Octavio Paz, Juan Rulfo, Jean-Paul Sartre, Susan Sontag, Mario Vargas Llosa y muchos otros. Después de 38 días de reclusión en Villa Marista, Padilla leyó en la Unión de Escritores su famosa Autocrítica. Su esposa logró salir con su hijo pequeño hacia Estados Unidos en 1979, y al año siguiente, gracias a la presión internacional, permitió a Padilla viajar también a ese país. Llegó a Nueva York, vía Montreal, el 16 de marzo de 1980. Como testimonian su esposa y el escritor Guillermo Cabrera Infante esta experiencia y el exilio cambiaron a Padilla, que enfermó espiritualmente y nunca pudo reponerse del todo. Murió de un ataque al corazón a los 68 años, recostado en un sofá en Alabama.

Violeta del Carmen Parra Sandoval (San Fabián de Alico o en San Carlos, el 4 de octubre de 1917 – Santiago de Chile, 5 de febrero de 1967) fue una cantautora, pintora, escultora, bordadora y ceramista chilena, considerada por algunos la folclorista más importante de Chile y fundadora de la música popular chilena. Era miembro de la prolífica familia Parra. El 5 de febrero de 1967, a los 49 años de vida, y tras varios intentos fallidos, Violeta Parra se suicidó.

#Chilenos #Mujeres #SigloXX #Suicidio

Claudio Martínez Paiva, a quien también se menciona como Claudio Martínez Payva fue un poeta, escritor, dramaturgo y periodista que nació el 9 de octubre de 1887 en Gualeguaychú, provincia de Entre Ríos, Argentina y falleció el 24 de marzo de 1970 en Argentina. Fue una figura destacada de la poesía gauchesca del Río de la Plata y uno de los primeros comediógrafos de la Argentina, que estrenó su primera obra teatral El idiota a los 24 años.

Gonzalo Rojas Pizarro (Lebu, 20 de diciembre de 1916 – Santiago, 25 de abril de 2011) fue un profesor y poeta chileno perteneciente a la llamada «Generación de 1938». Su obra se enmarca en la tradición continuadora de las vanguardias literarias latinoamericanas del siglo XX. Ampliamente reconocido a nivel Hispanoamericano, fue galardonado, entre otros, con el Premio Reina Sofía de Poesía Iberoamericana 1992, el Premio Nacional de Literatura de Chile 1992 y el Premio Cervantes 2003.

Javier Heraud Pérez (Miraflores, Lima, Perú, 19 de enero de 1942 – Madre de Dios, 15 de mayo de 1963), fue un poeta , profesor, guerrillero peruano. Desde muy niño mostró un gran interés por el estudio, lo que se reflejó en el ámbito académico, al ocupar el segundo puesto de su promoción en el colegio Markham, y el primer puesto de ingreso en la Facultad de Letras de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú en 1958. En 1960, aún siendo menor de edad, publica “El río”, poemario donde hizo gala de su talento para la composición literaria. “No deseo la victoria ni la muerte, no deseo la derrota ni la vida, sólo deseo el árbol y su sombra, la vida con su muerte” Convertirse en lo que uno es. Eso es todo.

#Asesinados #Peruanos #SigloXX

Facundo: Civilization and Barbarism (original Spanish title: Facundo: Civilización I Barbarie) is a book written in 1845 by Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, a writer and journalist who became the seventh president of Argentina. It is a cornerstone of Latin American literature: a work of creative non-fiction that helped to define the parameters for thinking about the region’s development, modernization, power, and culture. Subtitled Civilization and Barbarism, Facundo contrasts civilization and barbarism as seen in early 19th-century Argentina. Literary critic Roberto González Echevarría calls the work “the most important book written by a Latin American in any discipline or genre”. Facundo describes the life of Juan Facundo Quiroga, a gaucho who had terrorized provincial Argentina in the 1820s and 1830s. Kathleen Ross, one of Facundo’s English translators, points out that the author also published Facundo to “denounce the tyranny of the Argentine dictator Juan Manuel de Rosas”. Juan Manuel de Rosas ruled Argentina from 1829 to 1832 and again from 1835 to 1852; it was because of Rosas that Sarmiento was in exile in Chile, where he wrote the book. Sarmiento sees Rosas as heir to Facundo: both are caudillos and representatives of a barbarism that derives from the nature of the Argentine countryside. As Ross explains, Sarmiento’s book is therefore engaged in describing the “Argentine national character, explaining the effects of Argentina’s geographical conditions on personality, the 'barbaric’ nature of the countryside versus the 'civilizing’ influence of the city, and the great future awaiting Argentina when it opened its doors wide to European immigration”. Throughout the text, Sarmiento explores the dichotomy between civilization and barbarism. As Kimberly Ball observes, “civilization is identified with northern Europe, North America, cities, Unitarians, Paz, and Rivadavia”, while “barbarism is identified with Latin America, Spain, Asia, the Middle East, the countryside, Federalists, Facundo, and Rosas”. It is in the way that Facundo articulates this opposition that Sarmiento’s book has had such a profound influence. In the words of González Echevarría: “in proposing the dialectic between civilization and barbarism as the central conflict in Latin American culture Facundo gave shape to a polemic that began in the colonial period and continues to the present day”. The first edition of Facundo was published in instalments in 1845. Sarmiento removed the last two chapters of the second edition (1851), but restored them in the 1874 edition, deciding that they were important to the book’s development. The first translation into English, by Mary Mann, was published in 1868. A modern and complete translation by Kathleen Ross appeared in 2003 from the University of California Press. Background While exiled in Chile, Sarmiento wrote Facundo in 1845 as an attack on Juan Manuel de Rosas, the Argentine dictator at the time. The book was a critical analysis of Argentine culture as he saw it, represented in men such as Rosas and the regional leader Juan Facundo Quiroga, a warlord from La Rioja. For Sarmiento, Rosas and Quiroga were caudillos—strongmen who did not submit to the law. However, if Facundo’s portrait is linked to the wild nature of the countryside, Rosas is depicted as an opportunist who exploits the situation to perpetuate himself in power. Sarmiento’s book is a critique and also a symptom of Argentina’s cultural conflicts. In 1810, the country had gained independence from the Spanish Empire, but Sarmiento complains that Argentina had yet to cohere as a unified entity. The country’s chief political division saw the Unitarists (or Unitarians, with whom Sarmiento sided), who favored centralization, counterposed against the Federalists, who believed that the regions should maintain a good measure of autonomy. This division was in part a split between the city and the countryside. Then as now, Buenos Aires was the country’s largest and wealthiest city as a result of its access to river trade routes and the South Atlantic. Buenos Aires was exposed not only to trade but to fresh ideas and European culture. These economic and cultural differences caused tension between Buenos Aires and the land-locked regions of the country. Despite his Unitarian sympathies, Sarmiento himself came from the provinces, a native of the Western town of San Juan. Argentine civil war Argentina’s divisions led to a civil war that began in 1814. A frail agreement was reached in the early 1820s, which led to the unification of the Republic just in time to wage the Cisplatine War against the Empire of Brazil, but the relations between the Provinces reached again the point of breaking-off in 1826, when Unitarist Bernardino Rivadavia was elected president and tried to enforce a newly enacted centralist Constitution. Supporters of decentralized government challenged the Unitarist Party, leading to the outbreak of violence. Federalists Juan Facundo Quiroga and Manuel Dorrego wanted more autonomy for the provinces and were inclined to reject European culture. The Unitarists defended Rivadavia’s presidency, as it created educational opportunities for rural inhabitants through a European-staffed university program. However, under Rivadavia’s rule, the salaries of common laborers were subjected to government wage ceilings, and the gauchos ("cattle-wrangling horsemen of the pampas") were either imprisoned or forced to work without pay. A series of governors were installed and replaced beginning in 1828 with the appointment of Federalist Manuel Dorrego as the governor of Buenos Aires. However, Dorrego’s government was very soon overthrown and replaced by that of Unitarist Juan Lavalle. Lavalle’s rule ended when he was defeated by a militia of gauchos led by Rosas. By the end of 1829, the legislature had appointed Rosas as governor of Buenos Aires. Under Rosas’s rule, many intellectuals fled either to Chile, as did Sarmiento, or to Uruguay, as Sarmiento himself notes. Juan Manuel de Rosas According to Latin American historian John Lynch, Juan Manuel de Rosas was "a landowner, a rural caudillo, and the dictator of Buenos Aires from 1829 to 1852". He was born into a wealthy family of high social status, but Rosas’s strict upbringing had a deep psychological influence on him. Sarmiento asserts that because of Rosas’s mother, “the spectacle of authority and servitude must have left lasting impressions on him”. Shortly after reaching puberty, Rosas was sent to an estancia and stayed there for about thirty years. In time, he learned how to manage the ranch and he established an authoritarian government in the area. While in power, Rosas incarcerated residents for unspecified reasons, acts which Sarmiento argues were similar to Rosas’s treatment of cattle. Sarmiento argues that this was one method of making his citizens like the “tamest, most orderly cattle known”. Juan Manuel de Rosas’s first term as governor lasted only three years. His rule, assisted by Juan Facundo Quiroga and Estanislao López, was respected and he was praised for his ability to maintain harmony between Buenos Aires and the rural areas. The country fell into disorder after Rosas’s resignation in 1832, and in 1835 he was once again called to lead the country. He ruled the country not as he did during his first term as governor, but as a dictator, forcing all citizens to support his Federalist regime. According to Nicolas Shumway, Rosas “forced the citizens to wear the red Federalist insignia, and his picture appeared in all public places... Rosas’s enemies, real and imagined, were increasingly imprisoned, tortured, murdered, or driven into exile by the mazorca, a band of spies and thugs supervised personally by Rosas. Publications were censored, and porteño newspapers became tedious apologizers for the regime”. Domingo Faustino Sarmiento In Facundo, Sarmiento is both the narrator and a main character. The book contains autobiographical elements from Sarmiento’s life, and he comments on the entire Argentine circumstance. He also expresses and analyzes his own opinion and chronicles some historic events. Within the book’s dichotomy between civilization and barbarism, Sarmiento’s character represents civilization, steeped as he is in European and North American ideas; he stands for education and development, as opposed to Rosas and Facundo, who symbolize barbarism. Sarmiento was an educator, a civilized man who was a militant adherent to the Unitarist movement. During the Argentine civil war he fought against Facundo several times, and while in Spain he became a member of the Literary Society of Professors. Exiled to Chile by Rosas when he started to write Facundo, Sarmiento would later return as a politician. He was a member of the Senate after Rosas’s fall and president of Argentina for six years (1868–1874). During his presidency, Sarmiento concentrated on migration, sciences, and culture. His ideas were based on European civilization; for him, the development of a country was rooted in education. To this end, he founded Argentina’s military and naval colleges. Synopsis After a lengthy introduction, Facundo’s fifteen chapters divide broadly into three sections: chapters one to four outline Argentine geography, anthropology, and history; chapters five to fourteen recount the life of Juan Facundo Quiroga; and the concluding chapter expounds Sarmiento’s vision of a future for Argentina under a Unitarist government. In Sarmiento’s words, the reason why he chose to provide Argentine context and use Facundo Quiroga to condemn Rosas’s dictatorship is that “in Facundo Quiroga I do not only see simply a caudillo, but rather a manifestation of Argentine life as it has been made by colonization and the peculiarities of the land”. Argentine context Facundo begins with a geographical description of Argentina, from the Andes in the west to the eastern Atlantic coast, where two main river systems converge at the boundary between Argentina and Uruguay. This river estuary, called the Rio de Plata, is the location of Buenos Aires, the capital. Through his discussion of Argentina’s geography, Sarmiento demonstrates Buenos Aires’ advantages; the river systems were communications arteries which, by enabling trade, helped the city to achieve civilization. Buenos Aires failed to spread civilization to the rural areas and as a result, much of the rest of Argentina was doomed to barbarism. Sarmiento also argues that the pampas, Argentina’s wide and empty plains, provided “no place for people to escape and hide for defense and this prohibits civilization in most parts of Argentina”. Despite the barriers to civilization caused by Argentina’s geography, Sarmiento argues that many of the country’s problems were caused by gauchos like Juan Manuel de Rosas, who were barbaric, uneducated, ignorant, and arrogant; their character prevented Argentine society’s progress toward civilization. Sarmiento then describes the four main types of gaucho and these characterizations aid in understanding Argentine leaders, such as Juan Manuel de Rosas. Sarmiento argues that without an understanding of these Argentine character types, “it is impossible to understand our political personages, or the primordial, American character of the bloody struggle that tears apart the Argentine Republic”. Sarmiento then moves on to the Argentine peasants, who are “independent of all need, free of all subjection, with no idea of government”. The peasants gather at taverns, where they spend their time drinking and gambling. They display their eagerness to prove their physical strength with horsemanship and knife fights. Rarely these displays led to deaths, and Sarmiento notes that Rosas’s residence was sometimes used as a refuge on such occasions, before he became politically powerful. According to Sarmiento, these elements are crucial to an understanding of the Argentine Revolution, in which Argentina gained independence from Spain. Although Argentina’s war of independence was prompted by the influence of European ideas, Buenos Aires was the only city that could achieve civilization. Rural people participated in the war to demonstrate their physical strengths rather than because they wanted to civilize the country. In the end, the revolution was a failure because the barbaric instincts of the rural population led to the loss and dishonor of the civilized city—Buenos Aires. Life of Juan Facundo Quiroga The second section of Facundo explores the life of its titular character, Juan Facundo Quiroga—the “Tiger of the Plains”. Despite being born into a wealthy family, Facundo received only a basic education in reading and writing. He loved gambling, being called el jugador (the player)—in fact, Sarmiento describes his gambling as “an ardent passion burning in his belly”. As a youth Facundo was antisocial and rebellious, refusing to mix with other children, and these traits became more pronounced as he matured. Sarmiento describes an incident in which Facundo killed a man, writing that this type of behaviour “marked his passage through the world”. Sarmiento gives a physical description of the man he considers to personify the caudillo: "[he had a] short and well built stature; his broad shoulders supported, on a short neck, a well-formed head covered with very thick, black and curly hair", with “eyes... full of fire”. Facundo’s relations with his family eventually broke down, and, taking on the life of a gaucho, he joined the caudillos in the province of Entre Ríos. His killing of two Spaniards after a jailbreak saw him acclaimed as a hero among the gauchos, and on relocating to La Rioja, Facundo was appointed to a leadership position in the Llanos Militia. He built his reputation and won his comrades’ respect through his fierce battlefield performances, but hated and tried to destroy those who differed from him by being civilized and well-educated. In 1825, when Unitarist Bernardino Rivadavia became the governor of the Buenos Aires province, he held a meeting with representatives from all provinces in Argentina. Facundo was present as the governor of La Rioja. Rivadavia was soon overthrown, and Manuel Dorrego became the new governor. Sarmiento contends that Dorrego, a Federalist, was interested neither in social progress nor in ending barbaric behaviour in Argentina by improving the level of civilization and education of its rural inhabitants. In the turmoil that characterized Argentine politics at the time, Dorrego was assassinated by Unitarists and Facundo was defeated by Unitarist General José María Paz. Facundo escaped to Buenos Aires and joined the Federalist government of Juan Manuel de Rosas. During the ensuing civil war between the two ideologies, Facundo conquered the provinces of San Luis, Cordoba and Mendoza. On return to his San Juan home, which Sarmiento says Facundo governed “solely with his terrifying name”, he realized that his government lacked support from Rosas. He went to Buenos Aires to confront Rosas, who sent him on another political mission. On his way back, Facundo was shot and killed at Barranca Yaco, Córdoba. According to Sarmiento, the murder was plotted by Rosas: “An impartial history still awaits facts and revelations, in order to point its finger at the instigator of the assassins”. Consequences of Facundo’s death In the book’s final chapters, Sarmiento explores the consequences of Facundo’s death for the history and politics of the Argentine Republic. He further analyzes Rosas’s government and personality, commenting on dictatorship, tyranny, the role of popular support, and the use of force to maintain order. Sarmiento criticizes Rosas by using the words of the dictator, making sarcastic remarks about Rosas’s actions, and describing the “terror” established during the dictatorship, the contradictions of the government, and the situation in the provinces that were ruled by Facundo. Sarmiento writes, “The red ribbon is a materialization of the terror that accompanies you everywhere, in the streets, in the bosom of the family; it must be thought about when dressing, when undressing, and ideas are always engraved upon us by association”. Finally, Sarmiento examines the legacy of Rosas’s government by attacking the dictator and widening the civilization–barbarism dichotomy. By setting France against Argentina—representing civilization and barbarism respectively—Sarmiento contrasts culture and savagery: France’s blockade had lasted for two years, and the 'American’ government, inspired by 'American’ spirit, was facing off with France, European principles, European pretensions. The social results of the French blockade, however, had been fruitful for the Argentine Republic, and served to demonstrate in all their nakedness the current state of mind and the new elements of struggle, which were to ignite a fierce war that can end only with the fall of that monstrous government. Genre and style Spanish critic and philosopher Miguel de Unamuno comments of the book, “I never took Facundo by Sarmiento as a historical work, nor do I think it can be very valued in that regard. I always thought of it as a literary work, as a historical novel”. However, Facundo cannot be classified as a novel or a specific genre of literature. According to González Echevarría, the book is at once an "essay, biography, autobiography, novel, epic, memoir, confession, political pamphlet, diatribe, scientific treatise, [and] travelogue". Sarmiento’s style and his exploration of the life of Facundo unify the three distinct parts of his work. Even the first section, describing Argentina’s geography, follows this pattern, since Sarmiento contends that Facundo is a natural product of this environment. The book is partly fictional, as well: Sarmiento draws on his imagination in addition to historical fact in describing Rosas. In Facundo, Sarmiento outlines his argument that Rosas’s dictatorship is the main cause of Argentina’s problems. The themes of barbarism and savagery that run through the book are, to Sarmiento, consequences of Rosas’s dictatorial government. To make his case, Sarmiento often has recourse to strategies drawn from literature. Themes Civilization and barbarism Facundo is not only a critique of Rosas’s dictatorship, but a broader investigation into Argentine history and culture, which Sarmiento charts through the rise, controversial rule, and downfall of Juan Facundo Quiroga, an archetypical Argentine caudillo. Sarmiento summarizes the book’s message in the phrase “That is the point: to be or not to be savages”. The dichotomy between civilization and barbarism is the book’s central idea; Facundo Quiroga is portrayed as wild, untamed, and standing opposed to true progress through his rejection of European cultural ideals—found at that time in the metropolitan society of Buenos Aires. The conflict between civilization and barbarism mirrors Latin America’s difficulties in the post-Independence era. Literary critic Sorensen Goodrich argues that although Sarmiento was not the first to articulate this dichotomy, he forged it into a powerful and prominent theme that would impact Latin American literature. He explores the issue of civilization versus the cruder aspects of a caudillo culture of brutality and absolute power. Facundo set forth an oppositional message that promoted a more beneficial alternative for society at large. Although Sarmiento advocated various changes, such as honest officials who understood enlightenment ideas of European and Classical origin, for him education was the key. Caudillos like Facundo Quiroga are seen, at the beginning of the book, as the antithesis of education, high culture, and civil stability; barbarism was like a never ending litany of social ills. They are the agents of instability and chaos, destroying societies through their blatant disregard for humanity and social progress. If Sarmiento viewed himself as civilized, Rosas was barbaric. Historian David Rock argues that “contemporary opponents reviled Rosas as a bloody tyrant and a symbol of barbarism”. Sarmiento attacked Rosas through his book by promoting education and “civilized” status, whereas Rosas used political power and brute force to dispose of any kind of hindrance. In linking Europe with civilization, and civilization with education, Sarmiento conveyed an admiration of European culture and civilization which at the same time gave him a sense of dissatisfaction with his own culture, motivating him to drive it towards civilization. Using the wilderness of the pampas to reinforce his social analysis, he characterizes those who were isolated and opposed to political dialogue as ignorant and anarchic—symbolized by Argentina’s desolate physical geography. Conversely, Latin America was connected to barbarism, which Sarmiento used mainly to illustrate the way in which Argentina was disconnected from the numerous resources surrounding it, limiting the growth of the country. American critic Doris Sommer sees a connection between Facundo’s ideology and Sarmiento’s readings of Fenimore Cooper. She links Sarmiento’s remarks on modernization and culture to the American discourse of expansion and progress of the 19th century. Writing and power In the history of post-independence Latin America, dictatorships have been relatively common—examples range from Paraguay’s José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia in the 19th century to Chile’s Augusto Pinochet in the 20th. In this context, Latin American literature has been distinguished by the protest novel, or dictator novel; the main story is based around the dictator figure, his behaviour, characteristics and the situation of the people under his regime. Writers such as Sarmiento used the power of the written word in order to criticize government, using literature as a tool, an instance of resistance and as a weapon against repression. Making use of the connection between writing and power was one of Sarmiento’s strategies. For him, writing was intended to be a catalyst for action. While the gauchos fought with physical weapons, Sarmiento used his voice and language. Sorensen states that Sarmiento used "text as [a] weapon". Sarmiento was writing not only for Argentina but for a wider audience too, especially the United States and Europe; in his view, these regions were close to civilization; his purpose was to seduce his readers toward his own political viewpoint. In the numerous translations of Facundo, Sarmiento’s association of writing with power and conquest is apparent. Since his books often serve as vehicles for his political manifesto, Sarmiento’s writings commonly mock governments, with Facundo being the most prominent example. He elevates his own status at the expense of the ruling elite, almost portraying himself as invincible due to the power of writing. Toward the end of 1840, Sarmiento was exiled for his political views. Covered with bruises received the day before from unruly soldiers, he wrote in French, “On ne tue point les idees” (misquoted from “on ne tire pas des coups de fusil aux idees”, which means “ideas cannot be killed by guns”). The government decided to decipher the message, and on learning the translation, said, “So! What does this mean?”. With the failure of his oppressors to understand his meaning, Sarmiento is able to illustrate their ineptitude. His words are presented as a “code” that needs to be “deciphered”, and unlike Sarmiento those in power are barbaric and uneducated. Their bafflement not only demonstrates their general ignorance, but also, according to Sorensen, illustrates “the fundamental displacement which any cultural transplantation brings about”, since Argentine rural inhabitants and Rosas’s associates were unable to accept the civilized culture which Sarmiento believed would lead to progress in Argentina. Legacy For translator Kathleen Ross, Facundo is “one of the foundational works of Spanish American literary history”. It has been enormously influential in setting out a “blueprint for modernization”, with its practical message enhanced by a “tremendous beauty and passion”. However, according to literary critic González Echevarría it is not only a powerful founding text but “the first Latin American classic, and the most important book written about Latin America by a Latin American in any discipline or genre”. The book’s political influence can be seen in Sarmiento’s eventual rise to power. He became president of Argentina in 1868 and was finally able to apply his theories to ensure that his nation achieved civilization. Although Sarmiento wrote several books, he viewed Facundo as authorizing his political views. According to Sorensen, “early readers of Facundo were deeply influenced by the struggles that preceded and followed Rosas’s dictatorship, and their views sprang from their relationship to the strife for interpretive and political hegemony”. González Echevarría notes that Facundo provided the impetus for other writers to examine dictatorship in Latin America, and contends that it is still read today because Sarmiento created “a voice for modern Latin American authors”. The reason for this, according to González Echevarría, is that “Latin American authors struggle with its legacy, rewriting Facundo in their works even as they try to untangle themselves from its discourse”. Subsequent dictator novels, such as El Señor Presidente by Miguel Ángel Asturias and The Feast of the Goat by Mario Vargas Llosa, drew upon its ideas, and a knowledge of Facundo enhances the reader’s understanding of these later books. One irony of the impact of Sarmiento’s essay genre and fictional literature is that, according to González Echevarría, the gaucho has become “an object of nostalgia, a lost origin around which to build a national mythology”. While Sarmiento was trying to eliminate the gaucho, he also transformed him into a “national symbol”. González Echevarría further argues that Juan Facundo Quiroga also continues to exist, since he represents “our unresolved struggle between good and evil and our lives’ inexorable drive toward death”. According to translator Kathleen Ross, “Facundo continues to inspire controversy and debate because it contributes to national myths of modernization, anti-populism, and racist ideology”. Publication and translation history The first edition of Facundo was published in instalments in 1845, in the literary supplement of the Chilean newspaper El Progreso. The second edition, also published in Chile (in 1851), contained significant alterations—Sarmiento removed the last two chapters on the advice of Valentín Alsina, an exiled Argentinian lawyer and politician. However the missing sections reappeared in 1874 in a later edition, because Sarmiento saw them as crucial to the book’s development. Facundo was first translated in 1868, by Mary Mann, with the title Life in the Argentine Republic in the Days of the Tyrants; or, Civilization and Barbarism. More recently, Kathleen Ross has undertaken a modern and complete translation, published in 2003 by the University of California Press. In Ross’s “Translator’s Introduction,” she notes that Mann’s 19th-century version of the text was influenced by Mann’s friendship with Sarmiento and by the fact that he was at the time a candidate in the Argentine presidential election: “Mann wished to further her friend’s cause abroad by presenting Sarmiento as an admirer and emulator of United States political and cultural institutions”. Hence this translation cut much of what made Sarmiento’s work distinctively part of the Hispanic tradition. Ross continues: “Mann’s elimination of metaphor, the stylistic device perhaps most characteristic of Sarmiento’s prose, is especially striking”. Footnotes References Wikipedia—facundo

Juan de Dios Peza (México, 29 de junio de 1852 - 16 de marzo de 1910), fue un poeta, político y escritor mexicano. Fue nombrado miembro numerario de la Academia Mexicana de la Lengua, ocupó la silla IX en mayo de 1908. Estudios y primeros trabajos Nació en 1852 en la Ciudad de México, inició sus estudios en la Escuela de Agricultura, después pasó al Colegio de San Ildefonso y en 1867 ingresó a la Escuela Nacional Preparatoria. Se convirtió en el estudiante predilecto del pensador mexicano Ignacio Ramírez, "El Nigromante";2 fue también alumno de Ignacio Manuel Altamirano.3 Al egresar de ese centro de estudios ingresó a la Escuela de Medicina donde establece gran amistad con Manuel Acuña, quien lo llegó a estimar al grado de llamarlo "hermano", no terminó su carrera y se dedicó a las letras. Peza fue adicto del liberalismo, su entusiasmo y apasionamiento por ese modo de entender la política y la vida social, y por el movimiento liberal mexicano, lo llevó a renunciar a sus estudios para entregarse de lleno al periodismo. Colaboró para la Revista Universal, El Eco de Ambos Mundos y La Juventud Literaria. En 1874 estrenó en el Teatro del Conservatorio su primera obra teatral llamada La ciencia del hogar. Vida política y desarrollo como escritor En 1878 es nombrado segundo secretario de la legación de México en España, al lado de Vicente Riva Palacio. En Madrid socializó con el político Emilio Castelar y con los escritores Gaspar Núñez de Arce, Ramón de Campoamor y José Selgas. Al regresar a México intentó hacer carrera política y fue electo diputado al Congreso de la Unión. Siguieron otros cargos públicos, pero sin abandonar las letras; como poeta su estilo es realista, aunque lleno de ternura. Su obra, de gran popularidad y aceptación en su patria, fue traducida al ruso, francés, inglés, alemán, húngaro, portugués, italiano y al japonés. El libro que más fama le dio fue Cantos del hogar; se trata de una poesía intimista al estilo del español José Selgas. Tuvo la desgracia de sufrir el abandono de su mujer, que lo dejó con dos hijos pequeños, a los que crio y educó con dedicación. Muere en 1910, año en el cual el país estaba a punto de entrar en otra gran conflagración: la Revolución mexicana. Poesía Poesías (1873) Canto a la Patria (1876) Horas de pasión (1876) La lira mexicana (1879) Fusiles y muñecas Reir llorando Prosa Poetas y escritores mexicanos (1878) Biografía de Ignacio M. Altamirano (1878) La beneficencia en México (1881) Memorias, reliquias y retratos (1900) Los últimos instantes de Colón (1874) Referencias Wikipedia - http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juan_de_Dios_Peza

Mario Santiago Papasquiaro, cuyo verdadero nombre era José Alfredo Zendejas Pineda (México, D. F., 25 de diciembre de 1953- 10 de enero de 1998), fue un poeta mexicano, fundador del movimiento infrarrealista. Infancia y juventud Nació en "una clínica que ya no existe en la cerrada de Rafael Guillén en la delegacion Mixcoac"1 (Distrito Federal, México, en realidad se llama Guillain). Según él mismo, escribía desde niño. Cambió su nombre a Mario Santiago (argumentando que José Alfredo solo había uno, José Alfredo Jiménez) y posteriormente a Santiago Papasquiaro en homenaje al lugar natal de José Revueltas). Su primer recital fue en 1973 y de forma personal el 3 de mayo de 1974 en el Museo Nacional de San Carlos. "Tuve oportunidad de conocer a mis 19 años a José Revueltas y a Efraín Huerta en sus respectivas casas. Yo soy hijo de ellos. Por eso mi seudónimo de Santiago Papasquiaro, el pueblo de Durango donde nacieron los hermanos Revueltas. Hay dos camadas fundamentales para mí, la de los Revueltas y la de los Flores Magón. Yo también tengo una formación anarquista", comentó. El infrarrealismo En 1976 junto con Roberto Bolaño, Cuauhtémoc Méndez Estrada, Ramón Méndez Estrada, Bruno Montané, Rubén Medina, Juan Esteban Harrington, Oscar Altamirano, José Peguero, Guadalupe Ochoa, José Vicente Anaya, Edgar Altamirano, José Rosas Ribeyro, Elmer Santana y Mara Larrosa fundó el infrarrealismo, corriente literaria de vanguardia y de verdadera ruptura con el establishment literario mexicano, lo que consiguió estilísticamente en algunos de sus integrantes, si bien Mario Santiago fue el máximo exponente y con mayor pureza estilística. Sus poemas son creaciones complejas y altamente metafóricas, eruditas y con referencias constantes a la percepción, los viajes y las caminatas. Mario Santiago redactó sus poemas buscando también la estética de los signos como los caligramas de Guillaume Apollinaire. –¿Es la poesía necesariamente molesta, transgresora? –A las moscas les pica la luz, a las lagartijas las calienta. La Poesía es psilocibina ardiente. Cantar Sympathy for the Devil a la luz de la luna más hiena. Exactamente como dijera el poeta eléctrico Michel Bulteau: "Arrodillarse en la boca crispada de las hadas". Los testimonios que recientemente recogió la audiorevista Nomedites número 8, dedicada al infrarrealismo coinciden en la entrega absoluta a la escritura, su talento pleno que "sacudió la pazgüatería de la poesía mexicana" y en la originalidad, pureza y creatividad de su estilo y la dificultad de trato en ciertas ocasiones por su carácter rebelde y retador. "Yo creo que estamos ante un poeta de dimensiones incalculables (...) había en él siempre un sentido de la provocación(...) te insultaba por elogiar sus poemas (...) era el testigo más incómodo de su propia poesía (...) hay poesía suya de altísimo nivel", recuerda Juan Villoro. Roberto Bolaño y Mario Santiago Papasquiaro fueron los pilares del movimiento infrarrealista, teniendo como principal guía la oposición y la rebeldía: "Volarle la tapa de los sesos a la cultura oficial", dice el Manifiesto infrarrealista. Ambos alcanzaron, en la prosa (Los detectives salvajes) y en la poesía (Aullido de cisne) respectivamente, concretar una corriente hasta hoy excluida del panorama literario mexicano y última en constituirse como tal, aunque cumpla las características para denominarla así: poseer una conciencia de grupo, crear un manifiesto con los puntos principales de acción y legar al patrimonio artístico obras de gran magnitud. Bolaño escribió acerca de su primer encuentro con Mario Santiago: “Lo vi por primera vez en la calle de Bucareli, en México, es decir en la adolescencia, en la zona borrosa y vacilante que pertenecía a los poetas de hierro, una noche cargada de niebla que obligaba a los coches a circular con lentitud y que disponía a los andantes a comentar, con regocijada extrañeza, el fenómeno brumoso, tan inusual en aquellas noches mexicanas, al menos hasta donde recuerdo. Antes de que me lo presentaran, en las puertas del Café La Habana, oí su voz, profunda, como de terciopelo, lo único que no ha cambiado con el paso de los años. Dijo: es una noche a la medida de Jack. Se refería a Jack el Destripador, pero su voz sonó evocadora de tierras sin ley, donde cualquier cosa era posible. Todos éramos adolescentes, adolescentes bragados, eso sí, y poetas y nos reímos” En adelante, Mario Santiago se entregó de forma total a la creación poética y en la década de los setenta a viajar. Estuvo en Barcelona, París (en donde se volvió a encontrar con el poeta peruano José Rosas Ribeyro y conoció a Elqui Burgos, estando ya muy vinculado con el Movimiento Hora Zero descubrió con uno de sus miembros, Elías Durand, la música de Miles Davis), Viena y Tel Aviv. En una carta a Santiago, poco antes de que éste falleciera el 10 de enero de 1998 en la Ciudad de México, Bolaño le escribió desde Barcelona: "Estoy con las ventanas abiertas, afuera llueve, una tormenta de verano, rayos, truenos, esas cosas que excitan o que impelen a la melancolía. ¿Cómo está México? ¿Cómo están las calles de México, mi fantasma, los amigos invisibles? ¿Sigue en pie Al Este del Paraíso o ya entró en el sueño de los justos?. Cuando mejore mi economía apareceré por tu casa una noche cualquiera. Y si no, es igual. El trecho que recorrimos juntos de alguna manera es historia y permanece. Quiero decir: sospecho, intuyo que aún está vivo, en medio de la oscuridad, pero vivo y todavía, quién lo iba a decir, desafiante. Bueno, no nos pongamos estupendos. Estoy escribiendo una novela donde tú te llamas Ulises Lima. La novela se llama Los detectives salvajes. / Un fuerte abrazo. R.” Mario Santiago Papasquiaro reconoció legalmente tres hijos: Zirahuen, Nadja y Mowgli. Un detective salvaje Roberto Bolaño lo convirtió en uno de los protagonistas de su novela Los detectives salvajes al crear el personaje de Ulises Lima, un poeta que como el hombre que lo inspiró se presenta como un aventurero y excéntrico, opositor de las formas tradicionales del literato vendido a las becas estatales y con una actitud snob. Tal postura le granjeó enemigos por doquier por su sinceridad y crítica abierta ante formas inferiores u oficiales de poesía o poetas, y que le ha segregado de cualquier tipo de reconocimiento hasta el día de hoy y a llevar un veto permanente aún después de la muerte. La representación literaria de su persona parece no estar alejada de la realidad, por los testimonios escritos y orales que sus compañeros de armas han dado. "Me he enfrentado con "(José Emilio) Pacheco, con (Carlos) Monsiváis, a todos los conozco. Nadie me quiere dar trabajo (...) Sergio Mondragón me ha negado trabajo porque soy infrarrealista. Dicen que yo saboteo recitales. Dicen que los infrarrealistas golpeamos a la gente. Y los imbéciles alegan que yo no sé escribir. Puta madre. Yo soy l’ecrivain. Pero eso no importa" Aunque lo que se dice de Mario Santiago Papasquiaro tiene algunos pincelazos de ficción, los puntos coincidentes en las descripciones que se hacen de él es la de una personalidad avasallante y un estilo de vida totalmente entregado a la creación literaria. Se carece de una biografía homogénea de Mario; lo que es innegable es la influencia decisiva en la obra de creadores posteriores -hay quienes lo reconocen y la mayoría no- y el importante legado disperso y sin recopilar -adicional a Aullido de Cisne- dejado por Mario Santiago, que su ex pareja Rebeca López García ha recopilado. Obra * Aullido de cisne (1998, Al este del paraíso) * Jeta de Santo (2008, Fondo de Cultura Económica) * Respiración del laberinto (2008) Sus poemas aparecieron en la antología de poetas infrarrealistas Pájaro de calor, 1976, en la revista Correspondencia infra, 1977 y en la antología de poetas latinoamericanos Muchachos desnudos bajo arco iris de fuego, 1979. Sus poemas fueron recopilados en Aullido de cisne, que vio la luz en 1996 en una pequeña editorial creada por Santiago y en la que editó cinco libros, incluido el suyo, de poetas infrarrealistas. Mario Santiago dijo que este libro es "...una leve probada de poemas (59) escritos entre 1979 y 1992, quizás apenas un 10 por ciento de lo que he garabateado desde 1973 hasta la fecha: aparte de aquello que se hayan tragado el cielo y el mar. Los diablitos chimuelos lo hubieran querido ver enterrado, pero aquí está el tridente de su vuelo" Su viuda, Rebeca López García (Q.E.P.D.) , y el escritor Mario Raúl Guzmán elaboraron la antología Jeta de Santo en 2008.5 Publicado por el Fondo de Cultura Económica España, reúne una selección de 161 poemas, de entre aproximadamente 1.500, escritos en los años 1974-1997. Según explica Guzmán en el prólogo, el título se lo sugirió el propio Mario Santiago. El mismo año apareció la antología Respiración del laberinto, selección más pequeña prologada por los escritores Bruno Montané, Juan Villoro, Diana Bellessi, Homero Carvhalo, Pedro Damian, Tulio Mora y Joseantonio Suárez en dependencia del país donde ha sido publicada. Sus textos Devoción Cherokee y Oración de Abril han sido musicalizados por Arturo Meza. El siguiente poema es el último que escribió, en donde Mario Santiago alude a La Hija de los Apaches, una pulquería de la colonia Romita en la Ciudad de México, atendida por el jicarero y ex-boxeador Epifanio Pifas Leyva. En ella hay pegados en sus paredes antiguas fotografías de boxeadores. En 2005 fue develada una placa en el lugar con este poema: EME ESE PE Moriré sorbiendo pulque de ajo Haciendo piruetas de cirquera en la Hija de los Apaches del buen Pifas' * * * Bajo la bendición de las imágenes sagradas/ inmortales del Kid/ el Chango/ el Battling/ el Púas Ultiminio/ el Ratón (sacerdotes del placer del cloroformo) * * * Qué más que saber salir de las cuerdas & fajarse la madre en el centro del ring La vida es 1 madriza sorda Alucine de Efe Zeta Película de Juan Orol Mejor largarse así Sin decir semen va o enchílame la otra Garabateando la posición del feto Pero ahora sí definitivamente & al revés. Un poema infrarreal de Mario Santiago Papasquiaro SAN JUAN DE LA CRUZ LE DA 1 AVENTÓN A NEAL CASSADY /EN LA FRONTERA ENTRE EL MITO & EL SUEÑO/ La carretera se pandea rumbo al centro de su propio :incendio centrífugo Tijuana se desvanece flotando bajo la mollera del ojo Esquirlas de cabaret & colchón empujan la estela de duendes que preña la ilusión de este instante En el radio: Jim Morrison traga esporas crecidas en la cicatriz del diluvio Este puente mental va al volante Estrellado el afuera & adentro Verde mota la selva El destino rodando Todo ser & hasta en zancos escupe ovnis bordados con alas de las más locas luciérnagas Es de noche / & en carretera / & volando Los Doors con los dientes hacen realidad su voltaje El cuerpo del alma se baña en el viaje El centro se curva La curva es salvaje La carretera es Dios mismo Cada ganglio / cada trozo resbala: se esfuma El pie va braceando La mente desyerba la euforia del eco. Testimonios sobre Mario Santiago Papasquiaro "Ulises Lima era mi amigo Mario Santiago Papasquiaro quien murió hace un año. Fue mi mejor amigo, mi mejor amigo de lejos (...) un ser extrañísimo, un lector empedernido con cosas tan extrañas como meterse a la ducha y salir leyendo. Siempre veía mis libros mojados y no sabia que había ocurrido ¿Será que México es tan grande que puede llover en ciertas partes? Me pregunté hasta que lo sorprendí leyendo en la ducha (...) Mario era un personaje fantástico, no tenía alguna disciplina. Él era un poeta poeta, un ser fantástico, muy valioso". Roberto Bolaño. "En el trato me tenía tanto respeto como cariño y yo a Mario lo quise mucho (...) Yo creo que Mario Santiago hizo una poesía adolescente, pero luego se deschavetó, se fue. No tenía una conciencia de transcurrir, sino la consigna del día". Orlando Guillén. "Estamos ante un poeta de dimensiones incalculables. Yo leí textos luminosos suyos, así como pésimos, pero Mario renunció a cualquier sentido de autocrítica porque era parte de su rebeldía. Creo también que como toda gente que se sintió marginada en un momento continuó en una fuga hacia adelante que dijo "Si me marginan porque escribo cosas intolerables, entonces las haré mas intolerables", entonces había en él siempre un sentido de la provocación (...) siempre andaba cargado de papeles y él te hacía leerlos en voz alta y opinar. Si lo elogiabas te insultaba, si te ponías de su parte te insultaba y te tomaba como un tipo blandengue y sin crítica. Él era el testigo más incómodo de su propia poesía. Hay poesía de él de altísimo nivel". Juan Villoro. "Mario era un poeta tormenta, magnífico y una persona toda ella con el espíritu de un poeta que quería del espacio en silencio de la poesía interpretar el mundo. Me gusta Mario Santiago todavía, lamento mucho que no esté publicada su poesía reunida". Carmen Boullosa. "En él hay una idea la fuerza amorfa brutal, velada y derretida, como lo que Rimbaud en la Carta del vidente describe: "Si de lo profundo viene amorfo, lo doy amorfo y si viene con forma lo doy con forma. Creo que ese tipo de testamentos del que fue heredero legítimo Mario pueden servir mucho para entender sus motivaciones y el secreto de sus recursos. Sus demonios son la embriaguez, la pobreza, la sordidez y cuando las mencionase las conjura, se pelea con ellos. No son sus socios, son sus formas de provocar al abismo, y de sacar del abismo lo que Rimbaud decía. Este placer que le da no ser monedita de oro, ser una mortificación hasta para las personas que él más estima. Era simplemente un hombre con talento pero con mucha indignación. No le bastaba la propia, agarraba la de la prostituta, la del criminal, necesitaba el sufrimiento de millares de seres para decir que no era fácil amar. Toda esta sociología de seres excepcionalmente defraudados, tristones, tenía su revancha en el verso agresivo y sorpresivo de Mario. Era un conspirador del espíritu". Horacio Caballero Referencias Wikipedia - http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mario_Santiago_Papasquiaro

#Mexicanos El escindido poeta

Ernesto Cardenal nos cuenta de su infancia, acudiendo a una prosa sencilla, casi «in sordina», para mejor celebrar al personaje que pasó rápidamente y sin excesivo ruido por la vida: «[...] muy pronto comenzó a hablar. Le llevaban su botella de leche a la escuela y la bebía ahí acostado en el suelo porque sólo así la podía beber. Amaba mucho los perros y tenía uno llamado "Gobi" que murió cuando Joaquín tenía doce años. Cuando Joaquín iba a morir dijo a su mamá que quería tener un petate y un perro, para recordar su infancia. La infancia de Joaquín fue en Granada. En el patio de su casa había un palo de mango donde él se subía a leer. Cuenta su mamá que desde el palo le gritaba que quería pan, y ella le subía el pan al palo. Pablo Antonio Cuadra, que era primo de Joaquín, me ha contado que fastidiaba con los perros. Pablo Antonio Cuadra pertenecía a una banda que se llamaba "La Mano Bermeja" y Joaquín pertenecía a una banda enemiga que se llamaba "La Mano Negra". Un día "La Mano Bermeja" le capturó el tesoro a "La Mano Negra", y entre las cosas del tesoro había un cuaderno de versos de Joaquín. Pablo Antonio que ya por entonces comenzaba también a escribir versos admiró los versos de Joaquín y desde entonces fueron amigos. [...]». Referencias http://www.cervantesvirtual.com/obra-visor/joaquin-pasos-o-el-dolor-de-vivir--0/html/0ab71f28-f33b-4bf9-9c97-ce4680a02f2c_3.html Epitafio para Joaquín Pasos de Ernesto Cardenal Aquí pasaba a pie por estas calles, sin empleo ni puesto Y sin un peso Sólo poetas, putas Pero recordadle cuando tengais puentes de concreto, Grandes turbinas, tractores, plateados graneros, buenos gobiernos. La guardia nacional anda buscando a un hombre un hombre espera esta noche llegar a la frontera el nombre de ese hombre no se sabe hay muchos hombres más enterrados en una zanja El número y el nombre de esos hombres no se sabe. Ni se sabe el lugar ni el número de zanjas. La guardia nacional anda buscando a un hombre Un hombre espera esta noche salir de Nicaragua 'Joaquín Pasos Arguello' (Granada, Nicaragua 1914 - Managua, Nicaragua 1947) fue un poeta, dramaturgo y ensayista nicaragüense. Nació el 14 de mayo en Granada (Nicaragua). Comenzó a escribir poesía, siendo muy joven. Desde 1929, con tan sólo 16 años, entra a formar parte del grupo "Movimiento de Vanguardia", en el que se cuentan, entre otros, José Coronel Urtecho, Pablo Antonio Cuadra, Manolo Cuadra y Luis Alberto Cabrales. Pasos fue el miembro más joven del grupo, y abanderó la tendencia que se conoció como "Anti-Parnaso", por la decisiva lucha contra las formas parnasianas imperantes en las letras nicaragüenses de aquella época. En 1932 se graduó en el Colegio Centroamérica. Colaboró en diversas publicaciones vinculadas a las vanguardias literarias de la época, como el periódico La Reacción, o la revista humorística Los Lunes, donde alcanzó notable popularidad. En varias ocasiones fue encarcelado por sus sátiras contra el dictador Somoza. En 1939 escribió junto a José Coronel Urtecho una pieza teatral titulada Chinfonía burguesa. Murió en Managua un 20 de enero de 1947, debido a problemas de salud provocados por el alcoholismo sin haber llegado a reunir su obra poética en forma de libro. Su muerte provocó una gran conmoción en las letras nicaragüenses. Ese mismo año fue publicada una antología de su obra titulada Breve Suma. En 1962 Ernesto Cardenal realizó una nueva antología más completa bajo el título de Poemas de un joven Sus poemas fueron agrupados de acuerdo al plan que el mismo Joaquín había diseñado: Poemas de un joven que no ha viajado nunca (que incluía poemas sobre países que nunca visitó); Poemas de un joven que no ha amado nunca (que incluía sus poesía amorosa); Poemas de un joven que no sabe inglés (que incluía sus poemas en esa lengua, que aprendió sin maestro desde niño); y además, Misterio indio (sus poemas de temática indígena). Su poema Canto de guerra de las cosas está considerado como el más importante de su producción; su poema Coral de mendigos es digna de la antología latinoamericana más exigente. Referencias Wikipedia-http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joaqu%C3%ADn_Pasos

Aprendiz y estudiante del arte y de la vida de medio tiempo y escritora y dibujante de tiempo completo (no profesional), sin embargo es uno de mis sueños, por esta razón es que escribo y me gustaría que más gente me ayudara a volverlo realidad, ya que lamentablemente dependo de ello. "Escribo para vivir y vivo para escribir". Entré a este sitio buscando material para matar el tiempo, pero terminó siendo parte de mi vida, ojalá no se vuelva tan importante como para volverse más que una parte de mi vida, parte de mi ser, después de todo no importa, pasar gran parte del día escribiendo en vez de hacer algo con mi vida es un mal hábito que me alegra tener, y definitivamente adentrarte en el mundo de la poesía es como una droga, una vez que lo has probado ya no puedes salir de ella, es como estar drogado sin drogarte, y esa sensación para mí es de las más asombrosas que puedes experimentar en la vida.

Juan Luis Panero Blanc (Madrid, 1942) es un poeta español. Hijo del poeta Leopoldo Panero (1909–1962) y Felicidad Blanc (1913–1990), hermano del poeta Leopoldo María Panero (1948) y Michi Panero (1951–2004) y sobrino del poeta Juan Panero (1908–1937), creció en el seno de una familia acomodada recibiendo educación en El Escorial y luego en Londres. Su espíritu rebelde y viajero lo llevó a deambular por diferentes países de América, dándole la oportunidad de conocer a grandes escritores como Octavio Paz, Jorge Luis Borges y Juan Rulfo entre otros. Su poesía completa (1968–1996) está recogida en un volumen de la editorial Tusquets y algunas de sus conferencias, en particular la que recoge su relación con Luis Cernuda, están incluidas bajo el título de «Páginas sobre cine y poesía» en el libro Después de tantos desencantos. Vida y obra poéticas de los Panero, de Federico Utrera (Ed. Festival Internac. de Cine de LPGC, 2008). Ha preparado además antologías de poetas como Leopoldo Panero, Pablo Neruda y Octavio Paz y ha reunido selecciones de Poesía colombiana (1880–1980) y Poesía mejicana contemporánea. Vive en Gerona desde 1985. Obra poética Su irrupción en la poesía española contemporánea se inició en 1968 con la publicación del libro A través del tiempo, al que siguieron, luego, Los trucos de la muerte, en 1975; Desapariciones y fracasos, en 1978; y Juegos para aplazar la muerte, en 1984. Antes que llegue la noche (1985) le permitió obtener el Premio Ciudad de Barcelona. En 1988, con «Galerías y fantasmas», obtuvo el Premio Internacional de Poesía de la Fundación Loewe. Sin rumbo cierto, XII Premio Comillas de Biografía, Autobiografía y Memorias, y Enigmas y despedidas, publicado en 1999, son sus últimas producciones. En 2009 Ediciones Vitruvio publica La memoria y la muerte, una antología que recoge toda su obra poética editada hasta la fecha. El desencanto En 1976 Jaime Chávarri inicia el rodaje de lo que tenía que ser un reportaje sobre el padre: Leopoldo Panero, el material se convierte en la película "El desencanto" que acabará siendo un símbolo tanto de la familia como de la época y será una película de culto para toda una generación. En El desencanto la madre, paradójicamente llamada Felicidad, y dos de sus hijos, retratan a través de sus recuerdos al poeta, siempre ausente (mientras que en la segunda parte, Después de tantos años, Leopoldo María, el hijo, se convertiría en el eje central del film). Pero sobre esta peculiar y decadente estampa familiar pesa el reflejo de una época que se agota. Los últimos coletazos del franquismo se dejan ver a través de la evocación de la vieja gloria de quien fuera uno de los escritores oficiales del régimen. El desencanto fue además la última película mutilada por la censura cinematográfica en España y una de las obras de Chávarri más reconocidas por la crítica. Ya en 1994 llegaría "Después de tantos años", película en la que Ricardo Franco retoma la labor de retratista emprendida por Jaime Chávarri dos décadas antes. Referencias wikipedia-http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juan_Luis_Panero

Delfín Prats es un poeta cubano. Nació en Holguín, en 1945. Estudió Filología y Lenguas Rusas en la desaparecida Unión Soviética. Por muchos años fue traductor de ruso. En 1968 su poemario Lenguaje de mudos ganó el premio David de la Unión de Escritores y Artistas de Cuba (UNEAC). Sin embargo, la obra fue censurada y el libro, convertido en pulpa. Prats volvió a publicar en Cuba en 1987 cuando apareció Para festejar el ascenso de Ícaro, que ganó el Premio Nacional de la Crítica. Otros poemarios suyos son: El esplendor y el caos y Aguas.

José María Pemán y Pemartín (retratos) (Cádiz, 8 de mayo de 1897 – 19 de julio de 1981) fue un escritor español. Formación Junto con su hermano César, procedía de una familia de la buena sociedad de Cádiz. Su padre fue el abogado en ejercicio y diputado conservador gaditano Juan Gualberto Pemán y Maestre (1859-1922), perteneciente a la familia política de la Restauración, y su madre María Pemartín y Carrera Laborde Aramburu, de entronque jerezano. En la fachada de la casa en que nació en Cádiz (calle Isabel La Católica nº 12) existe una gran lápida, con una figura alegórica con la estética de la época, y su busto en bajorrelieve en bronce, obra del escultor Juan Luis Vassallo. Pemán creció durante la Restauración en el seno de un orden social burgués, parlamentario pero no democrático, y quasi patriarcal (cacicato estable) considerado "natural" y, por tanto, inmutable y legítimo: «La desigualdad social (...) es una ley inexorable contra la cual es inútil luchar porque Dios así lo ha dispuesto; nuestro deber es acatar Su insondable Voluntad y resignarnos cada uno con nuestra suerte, cumpliendo estrictamente en todas circunstancias nuestros deberes cristianos, que a la postre resultará lo más provechoso para todos, no sólo en el otro Mundo, sino en éste» . Conde de Rivadavia Referencias Wikipedia – http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/José_María_Pemán

Luego de décadas de silenciamiento o relegación, el escritor cubano Virgilio Piñera (1912-1979) ocupa un sitio referencial en la literatura cubana contemporánea. Los avatares del canon nacional de las letras se cumplen, como en pocos autores latinoamericanos del siglo XX, en este poeta, dramaturgo y narrador, nacido hace 100 años en Cárdenas, Matanzas. Los atributos de Piñera que molestaban al Estado cubano, hace apenas 20 años, son los mismos que le han ganado una presencia tutelar, cada vez más discernible entre las últimas generaciones de escritores de la isla y la diáspora. Virgilio Piñera (4 de agosto de 1912, Cárdenas, Matanzas, 18 octubre de 1979 – La Habana) fue un poeta cubano. Piñera cursó sus primeros estudios en su localidad natal, pero en 1925 se trasladó con su familia a pepeCamagüey, donde estudió el bachillerato. En 1938 se instaló en La Habana, en cuya universidad se doctoró en Filosofía y Letras en 1940. Ya el año anterior había empezado a publicar, sobre todo poemas, en la revista Espuela de plata, predecesora de Orígenes, en la que coincidió con José Lezama Lima. En 1941 vio la luz su primer poemario, Las furias, y ese mismo año escribió también la que es quizá su obra teatral más importante, Electra Garrigó, que se estrenó en La Habana, ocho años después, y constituyó uno de los grandes hitos del teatro cubano, para muchos críticos, como Rine Leal o Raquel Carrió, el verdadero comienzo del teatro cubano moderno.

.jpg?locale=es)

Escribo versos libres desde los 18 años. En la actualidad a mis 22 años, llevo conmigo unas 16 poesías que seguirán creciendo en número mientras tenga vida, porque ganas de escribir no me faltan. Casi siempre describo felices o desgarradoras historias de amor adolescente y de mi vida personal. Me gustaría trabajar próximamente en poemas de contenido social.

Josefina Pla (Isla de Lobos, España, 1903 - Asunción, Paraguay, 1999) poetisa, dramaturga, narradora, ensayista, ceramista, crítica de arte, pintora y periodista. Escribió poesía, cuento, novela y ensayo. Tuvo una gran influencia sobre futuras generaciones de intelectuales de Paraguay. A lo largo de su vida recibió numerosos premios y distinciones por su labor literaria y en defensa de los derechos humanos y la igualdad entre hombre y mujeres. Vivir la otra que soy que no fui que habría sido. Vivir la que sería Morir la que aún no soy. Dormir todos los fui Despertar otro voy. Nos habremos deseado tanto que el beso habrá muerto. Desnudo Día, 1936 Infancia y Juventud Si bien se sabe que nació en la Isla de Lobos, Canarias, España, que es hija de Leopoldo Plá y de Rafaela Guerra Galvani, no existen datos ciertos acerca de la fecha de su nacimiento. Miembros de su familia muy próximos a ella indican que fue en 1903. El erudito Profesor Raúl Amaral, uno de sus biógrafos más connotados, asegura que nació el 9 de noviembre de 1903. Pasó su infancia y su juventud en diversas ciudades de España acompañando a su padre, funcionario en provincias. En 1924 conoció en Villajoyosa, Alicante, España, al artista paraguayo Andrés Campos Cervera, cuyo seudónimo artístico de Julián de la Herrería ha forjado su inmortalidad, con quien casó dos años después. El Gobierno español le otorga la distinción "Dama de la Orden de Isabel la Católica", el mismo año que en Paraguay recibe el premio "Mujer del Año" Vida en Paraguay En 1926 llegó al Paraguay y se estableció en el barrio Villa Aurelia y luego en el centro de Asunción, capital del país. De ese mismo año datan sus primeras incursiones en el ambiente artístico de la que sería su patria de adopción, pues presentó sus escritos en la revista “Juventud”, vocero de la generación de escritores del postmodernismo paraguayo. Desde ese tiempo y hasta 1938 viajó dos veces más a España junto a su esposo y, entretanto, colaboró en diversos periódicos y revistas del Paraguay con poemas, artículos y otros textos literarios. Trayectoria Su marido falleció en 1937. A su regreso al Paraguay, un año después, se convirtió en una de las figuras capitales del movimiento literario renovador, especialmente en poesía, que junto con ella encabezó Hérib Campos Cervera, sobrino carnal de su marido. Desde entonces realizó una intensa y descomunal tarea como periodista, escritora y artista plástica, que se extendió hasta el final de sus días. A lo largo de su vida recibió una serie de premios, galardones y nominaciones. Enumerarlas sería abrumador. Destacan, sin embargo, la condición de Dama de Honor de la Orden de Isabel la Católica (1977); la de miembro de la Academia Internacional de Cerámica con sede en Ginebra, Suiza; la de miembro fundadora del PEN Club Paraguayo; el trofeo “Ollantay” a la investigación teatral, de Venezuela (1984); la de “Mujer del año” (1977); la Medalla del Bicentenario de los Estados Unidos de América (1976); la condición de Consejera del Vice Ministerio de Cultura del Paraguay; la “Orden Nacional del Mérito” en el grado de Comendador, del gobierno paraguayo (1994); el galardón por su defensa de los derechos humanos, otorgada por la Sociedad Internacional de Juristas; la Medalla de Oro de las Bellas Artes de España (1995); la Medalla Johann Gottfried von Herder; la de miembro de las Academias Paraguaya de la Lengua, de la Historia Paraguaya y de la Historia Española; la de finalista en el concurso de méritos para el Premio “Príncipe de Asturias” (1981); la de su postulación para el “Premio Cervantes”, máximo galardón de las letras hispánicas, en los años 1989 y 1994; la “Ciudadanía Honoraria” conferida por el Parlamento paraguayo en 1998, entre otras. Fue fundadora, a inicios de los años 50 en el Siglo pasado, junto al brasileño Joao Rossi y a Olga Blinder, del “Grupo Arte Nuevo”, nervio motor de la más rotunda innovación en las artes plásticas del Paraguay. Últimos años Rodeada de la consideración y el respeto de intelectuales y artistas del Paraguay, España y el mundo, falleció en Asunción el 20 de enero de 1999. Obras Su obra abarca el campo de la creación literaria –más de cuarenta títulos en poesía, narrativa y teatro-, la historia social y cultural del Paraguay, la cerámica, la pintura y la crítica, por lo cual, con justicia es considerada como el más alto, fundamental e insustituible referente en materia cultural en el Paraguay en el siglo pasado. Año Obras * 1934 “El precio de los sueños” * 1950 “Una Novia para Josevai” * 1960 “La raíz y la aurora” * 1965 “Rostros en el agua” * 1965 “Invención de la muerte” * 1966 “Satélites oscuros” * 1968 “El polvo enamorado” * 1968 “Desnudo día” * 1975 “Luz negra” * 1927-1977 “Antología Poética” * 1982 “Follaje del tiempo”, “Tiempo y tiniebla” * 1984 “Cambiar sueños por sombras”. * 1985 “La nave del olvido”. * 1985 “La llama y la arena”. “Los treinta mil ausentes”. * 1996 “De la imposible ausente” Su producción dramática incluye, desde 1927 hasta 1974, “Víctima propiciatoria”, “Episodios chaqueños” (con Roque Centurión Miranda), “Porasy” (libreto de ópera con música de Otakar Platal), “Desheredado”, “La hora de Caín”, “Aquí no ha pasado nada”, “Un sobre en blanco”, “María inmaculada”, “Pater familias” (todas con Roque Centurión Miranda), “La humana impaciente”, “Fiesta en el río”, “El edificio”, “De mí que no del tiempo”, “El pretendiente inesperado”, “Historia de un número”, “Esta es la casa que Juana construyó”, “La cocina de las sombras”, “El profesor”, “El pan del avaro”, “El rey que rabió” y “El hombre de oro” (las tres últimas, piezas para niños), “La tercera huella dactilar”, “Media docena de grotescos brevísimos”, “Las ocho sobre el mar”, “Hermano Francisco”, “Momentos estelares de la mujer (serie de obras breves)”, “Don Quijote y los Galeotes”, “El hombre en la cruz”, “El empleo” y “Alcestes”. Su obra sobre historia cultural y social del Paraguay incluye los títulos siguientes: “La cultura paraguaya y el libro”, “Literatura paraguaya del Siglo XX”, “Apuntes para una historia de la cultura paraguaya”, “Arte actual en el Paraguay”, “Cuatro siglos de teatro en el Paraguay”, “Impacto de la cultura de las Reducciones en lo Nacional”, “Apuntes para una aproximación a la Imaginería Paraguaya”, “El Templo de Yaguarón”, “El barroco hispano-guaraní”, “Las artesanías en el Paraguay”, “Ñandutí. Encrucijada de dos mundos”, “El espíritu del fuego”, “El libro en la época colonial”, “Bilingüismo y tercera lengua en el Paraguay”, “Españoles en la cultura del Paraguay” y “La mujer en la plástica paraguaya”. Uno de los poemas de Josefina Plá que más valor significativo tenía para la autora es: Quisiera Quisiera desdormirme y desandarme Quisiera desfirmarme y desdecirme Quisiera devolverme y desllorarme Quisiera a veces desarrepentirme Por largas avenidas des-soñarme Los sueños que soñé desolvidarme Sombra volver del cuerpo. Desamarme Presentirme. Saber dónde buscarme Mi propio llanto ser y así sorberme y ser el metro con el cual medirme el vaso con el cual mi sed beberme y el puño que el mal golpe ha de infligirme Quisiera alguna vez ser la cuchilla que me corta y saber lo que ella siente Quisiera alguna vez sencillamente andar descalza por mi propia orilla. Referencias Wikipedia - http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Josefina_Pla

Rosario Sansores Prén (Mérida, Yucatán; 25 de agosto de 1889 — Ciudad de México; 7 de enero de 1972) fue una poetisa mexicana, conocida por obras como "Cuando tú te hayas ido", poema que sirvió de base al pasillo "Sombras", musicalizado por el compositor ecuatoriano Carlos Brito Benavides. Nació en un hogar acaudalado, hija de Juan Ignacio Sansores Escalante y Laura Prén Cámara, quienes intentaron disuadirla de escribir poesía a corta edad. A los catorce años de edad se casó con el cubano Antonio Sangenis y se mudó a La Habana, donde viviría por veintitrés años. Durante el tiempo que vivió en Cuba se dedicó a escribir artículos sobre temas sociales en periódicos y revistas. En 1911 empezó a publicar sus libros de poesía, la mayoría firmados con seudónimos