Info

Charlotte Turner Smith (4 May 1749– 28 October 1806) was an English Romantic poet and novelist. She initiated a revival of the English sonnet, helped establish the conventions of Gothic fiction, and wrote political novels of sensibility. Smith was born into a wealthy family and received a typical education for a woman during the late 18th century. However, her father’s reckless spending forced her to marry early. In a marriage that she later described as prostitution, she was given by her father to the violent and profligate Benjamin Smith. Their marriage was deeply unhappy, although they had twelve children together. Charlotte joined Benjamin in debtor’s prison, where she wrote her first book of poetry, Elegiac Sonnets. Its success allowed her to help pay for Benjamin’s release. Benjamin’s father attempted to leave money to Charlotte and her children upon his death, but legal technicalities prevented her from ever acquiring it. Charlotte Smith eventually left Benjamin and began writing to support their children. Smith’s struggle to provide for her children and her frustrated attempts to gain legal protection as a woman provided themes for her poetry and novels; she included portraits of herself and her family in her novels as well as details about her life in her prefaces. Her early novels are exercises in aesthetic development, particularly of the Gothic and sentimentality. “The theme of her many sentimental and didactic novels was that of a badly married wife helped by a thoughtful sensible lover” (Smith’s entry in British Authors Before 1800: A Biographical Dictionary Ed. Stanley Kunitz and Howard Haycraft. New York: H.W. Wilson, 1952. pg. 478.) Her later novels, including The Old Manor House, often considered her best, support the ideals of the French Revolution. Smith was a successful writer, publishing ten novels, three books of poetry, four children’s books, and other assorted works, over the course of her career. She always saw herself as a poet first and foremost, however, as poetry was considered the most exalted form of literature at the time. Scholars credit Smith with transforming the sonnet into an expression of woeful sentiment that would pave the way for poets such as Coleridge, Wordsworth, Shelly and Keats. Smith’s poetry and prose was praised by contemporaries such as Romantic poets William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge as well as novelist Walter Scott. Coleridge, in 1796, even remarked that “those sonnets appear to me the most exquisite, in which moral Sentiments, Affections, or Feelings, are deduced from, and associated with the scenery of Nature”. After 1798, Smith’s popularity waned and by 1803 she was destitute and ill—she could barely hold a pen. She had to sell her books to pay off her debts. In 1806, Smith died. Largely forgotten by the middle of the 19th century, her works have now been republished and she is recognized as an important Romantic writer. Early life Smith was born on 4 May 1749 in London and baptized on 12 June; she was the oldest child of well-to-do Nicholas Turner and Anna Towers. Her two younger siblings, Nicholas and Catherine Ann, were born within the next five years. Smith’s childhood was shaped by her mother’s early death (probably in giving birth to Catherine) and her father’s reckless spending. After losing his wife, Nicholas Turner travelled and the children were raised by Lucy Towers, their maternal aunt (when exactly their father returned is unknown). At the age of six, Charlotte went to school in Chichester and took drawing lessons from the painter George Smith. Two years later, she, her aunt, and her sister moved to London and she attended a girls school in Kensington where she learned dancing, drawing, music, and acting. She loved to read and wrote poems, which her father encouraged. She even submitted a few to the Lady’s Magazine for publication, but they were not accepted. Marriage and first publication Smith’s father encountered financial difficulties upon his return to England and he was forced to sell some of the family’s holdings and to marry the wealthy Henrietta Meriton in 1765. Smith entered society at the age of twelve, leaving school and being tutored at home. On 23 February 1765, at the age of fifteen, she married Benjamin Smith, the son of Richard Smith, a wealthy West Indian merchant and a director of the East India Company. The proposal was accepted for her by her father; forty years later, Smith condemned her father’s action, which she wrote had turned her into a “legal prostitute”. Smith’s marriage was unhappy. She detested living in commercial Cheapside (the family later moved to Southgate and Tottenham) and argued with her in-laws, who she believed were unrefined and uneducated. They, in turn, mocked her for spending time reading, writing, and drawing. Even worse, Benjamin proved to be violent, unfaithful, and profligate. Only her father-in-law, Richard, appreciated her writing abilities, although he wanted her to use them to further his business interests. Richard Smith owned plantations in Barbados and he and his second wife brought five slaves to England, who, along with their descendants, were included as part of the family property in his will. Although Charlotte Smith later argued against slavery in works such as The Old Manor House (1793) and “Beachy Head”, she herself benefited from the income and slave labor of Richard Smith’s plantations. In 1766, Charlotte and Benjamin had their first child, who died the next year just days after the birth of their second, Benjamin Berney (1767–77). Between 1767 and 1785, the couple had ten more children: William Towers (born 1768), Charlotte Mary (born c. 1769), Braithwaite (born 1770), Nicholas Hankey (1771–1837), Married Anni Petroose (1779–1843), Charles Dyer (born 1773), Anna Augusta (1774–94), Lucy Eleanor (born 1776), Lionel (1778–1842), Harriet (born c. 1782), and George (born c. 1785). Only six of Smith’s children survived her. Smith assisted in the family business that her husband had abandoned by helping Richard Smith with his correspondence. She persuaded Richard to set Benjamin up as a gentleman farmer in Hampshire and lived with him at Lys Farm from 1774 until 1783. Worried about Charlotte’s future and that of his grandchildren and concerned that his son would continue his irresponsible ways, Richard Smith willed the majority of his property to Charlotte’s children. However, because he had drawn up the will himself, the documents contained legal problems. The inheritance, originally worth nearly £36,000, was tied up in chancery after his death in 1776 for almost forty years. Smith and her children saw little of it. (It has been proposed that this real case may have inspired the famous fictional case of Jarndyce and Jarndyce, in Dickens’s Bleak House.) In fact, Benjamin illegally spent at least a third of the legacy and ended up in King’s Bench Prison in December 1783. Smith moved in with him and it was in this environment that she wrote and published her first work, Elegiac Sonnets (1784). Elegiac Sonnets achieved instant success, allowing Charlotte to pay for their release from prison. Smith’s sonnets helped initiate a revival of the form and granted an aura of respectability to her later novels (poetry was considered the highest art form at the time). Smith revised Elegiac Poems several times over the years, eventually creating a two-volume work. Novelist After Benjamin Smith was released from prison, the entire family moved to Dieppe, France to avoid further creditors. Charlotte returned to negotiate with them, but failed to come to an agreement. She went back to France and in 1784 began translating works from French into English. In 1787 she published The Romance of Real Life, consisting of translated selections from François Gayot de Pitaval’s trials. She was forced to withdraw her other translation, Manon Lescaut, after it was argued that the work was immoral and plagiarized. In 1786, she published it anonymously. In 1785, the family returned to England and moved to Woolbeding House near Midhurst, Sussex. Smith’s relationship with her husband did not improve and on 15 April 1787, after twenty-two years of marriage, she left him. She wrote that she might “have been contented to reside in the same house with him”, had not “his temper been so capricious and often so cruel” that her “life was not safe”. When Charlotte left Benjamin, she did not secure a legal agreement that would protect her profits—he would have access to them under English primogeniture laws. Smith knew that her children’s future rested on a successful settlement of the lawsuit over her father-in-law’s will, therefore she made every effort to earn enough money to fund the suit and retain the family’s genteel status. Smith claimed the position of gentlewoman, signing herself “Charlotte Smith of Bignor Park” on the title page of Elegiac Sonnets. All of her works were published under her own name, “a daring decision” for a woman at the time. Her success as a poet allowed her to make this choice. Throughout her career, Smith identified herself as a poet. Although she published far more prose than poetry and her novels brought her more money and fame, she believed poetry would bring her respectability. As Sarah Zimmerman claimed in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, “She prized her verse for the role it gave her as a private woman whose sorrows were submitted only reluctantly to the public.” After separating from her husband, Smith moved to a town near Chichester and decided to write novels, as they would make her more money than poetry. Her first novel, Emmeline (1788), was a success, selling 1500 copies within months. She wrote nine more novels in the next ten years: Ethelinde (1789), Celestina (1791), Desmond (1792), The Old Manor House (1793), The Wanderings of Warwick (1794), The Banished Man (1794), Montalbert (1795), Marchmont (1796), and The Young Philosopher (1798). Smith began her career as a novelist during the 1780s at a time when women’s fiction was expected to focus on romance and to foreground “a chaste and flawless heroine subjected to repeated melodramatic distresses until reinstated in society by the virtuous hero”. Although Smith’s novels employed this structure, they also incorporated political commentary, particularly support of the French Revolution, through the voices of male characters. At times, she challenged the typical romance plot by including “narratives of female desire” or “tales of females suffering despotism”. Smith’s novels contributed to the development of Gothic fiction and the novel of sensibility. Smith’s novels are autobiographical. While a common device at the time, Antje Blank writes in The Literary Encyclopedia, “few exploited fiction’s potential of self-representation with such determination as Smith”. For example, Mr. and Mrs. Stafford in Emmeline are portraits of Charlotte and Benjamin. The prefaces to Smith’s novels told the story of her own struggles, including the deaths of several of her children. According to Zimmerman, "Smith mourned most publicly for her daughter Anna Augusta, who married an émigré... and died aged twenty in 1795." Smith’s prefaces positioned her as both a suffering sentimental heroine as well as a vocal critic of the laws that kept her and her children in poverty. Smith’s experiences prompted her to argue for legal reforms that would grant women more rights, making the case for these reforms through her novels. Smith’s stories showed the “legal, economic, and sexual exploitation” of women by marriage and property laws. Initially readers were swayed by her arguments and writers such as William Cowper patronized her. However, as the years passed, readers became exhausted by Smith’s stories of struggle and inequality. Public opinion shifted towards the view of poet Anna Seward, who argued that Smith was “vain” and “indelicate” for exposing her husband to “public contempt”. Smith moved frequently due to financial concerns and declining health. During the last twenty years of her life, she lived in: Chichester, Brighton, Storrington, Bath, Exmouth, Weymouth, Oxford, London, Frant, and Elstead. She eventually settled at Tilford, Surrey. Smith became involved with English radicals while she was living in Brighton from 1791 to 1793. Like them, she supported the French Revolution and its republican principles. Her epistolary novel Desmond tells the story of a man who journeys to revolutionary France and is convinced of the rightness of the revolution and contends that England should be reformed as well. The novel was published in June 1792, a year before France and England went to war and before the Reign of Terror began, which shocked the British public, turning them against the revolutionaries. Like many radicals, Smith criticized the French, but she still endorsed the original ideals of the revolution. In order to support her family, Smith had to sell her works, thus she was eventually forced to, as Blank claims, “tone down the radicalism that had characterised the authorial voice in Desmond and adopt more oblique techniques to express her libertarian ideals”. She therefore set her next novel, The Old Manor House (1793), during the American Revolutionary War, which allowed her to discuss democratic reform without directly addressing the French situation. However, in her last novel, The Young Philosopher (1798), Smith wrote a final piece of “outspoken radical fiction”. Smith’s protagonist leaves Britain for America, as there is no hope for a reform in Britain. The Old Manor House is "frequently deemed [Smith’s] best" novel for its sentimental themes and development of minor characters. Novelist Walter Scott labeled it as such and poet and critic Anna Laetitia Barbauld chose it for her anthology of The British Novelists (1810). As a successful novelist and poet, Smith communicated with famous artists and thinkers of the day, including musician Charles Burney (father of Frances Burney), poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, scientist and poet Erasmus Darwin, lawyer and radical Thomas Erskine, novelist Mary Hays, playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan, and poet Robert Southey. A wide array of periodicals reviewed her works, including the Anti-Jacobin Review, the Analytical Review, the British Critic, The Critical Review, the European Magazine, the Gentleman’s Magazine, the Monthly Magazine, and the Universal Magazine. Smith earned the most money between 1787 and 1798, after which she was no longer as popular; several reasons have been suggested for the public’s declining interest in Smith, including “a corresponding erosion of the quality of her work after so many years of literary labour, an eventual waning of readerly interest as she published, on average, one work per year for twenty-two years, and a controversy that attached to her public profile” as she wrote about the French revolution. Both radical and conservative periodicals criticized her novels about the revolution. Her insistence on pursuing the lawsuit over Richard Smith’s inheritance lost her several patrons. Also, her increasingly blunt prefaces made her less appealing to the public. In order to continue earning money, Smith began writing in less politically charged genres. She published a collection of tales, Letters of a Solitary Wanderer (1801–02) and the play What Is She? (1799, attributed). Her most successful new foray was into children’s literature: Rural Walks (1795), Rambles Farther (1796), Minor Morals (1798), and Conversations Introducing Poetry (1804). She also wrote two volumes of a history of England (1806) and A Natural History of Birds (1807, posthumous). She also returned to writing poetry and Beachy Head and Other Poems (1807) was published posthumously. Publishers did not pay as much for these works, however, and by 1803, Smith was poverty-stricken. She could barely afford food and had no coal. She even sold her beloved library of 500 books in order to pay off debts, but feared being sent to jail for the remaining £20. Illness and death Smith complained of gout for many years (it was probably rheumatoid arthritis), which made it increasingly difficult and painful for her to write. By the end of her life, it had almost paralyzed her. She wrote to a friend that she was “literally vegetating, for I have very little locomotive powers beyond those that appertain to a cauliflower”. On 23 February 1806, her husband died in a debtors’ prison and Smith finally received some of the money he owed her, but she was too ill to do anything with it. She died a few months later, on 28 October 1806, at Tilford and was buried at Stoke Church, Stoke Park, near Guildford. The lawsuit over her father-in-law’s estate was settled seven years later, on 22 April 1813, more than thirty-six years after Richard Smith’s death. Legacy Stuart Curran, the editor of Smith’s poems, has written that Smith is “the first poet in England whom in retrospect we would call Romantic”. She helped shape the “patterns of thought and conventions of style” for the period. Romantic poet William Wordsworth was the most affected by her works. He said of Smith in the 1830s that she was “a lady to whom English verse is under greater obligations than are likely to be either acknowledged or remembered”. By the second half of the 19th century, Smith was largely forgotten. Smith’s novels were republished again at the end of the 20th century, and “critics interested in the period’s women poets and prose writers, the Gothic novel, the historical novel, the social problem novel, and post-colonial studies” have argued for her significance as a writer. They looked to the contemporary documentation of her importance, discovering that she helped to revitalize the English sonnet, a fact recognized by Coleridge and others. Scott wrote that she “preserves in her landscapes the truth and precision of a painter” and poet and Barbauld claimed that Smith was the first to include sustained natural description in novels. It was not until 2008 however, that Smith’s entire prose collection became available to the general public. The edition contains each novel, the children’s stories and rural walks.

William Edgar Stafford (January 17, 1914 – August 28, 1993) was an American poet and pacifist, and the father of poet and essayist Kim Stafford. He was appointed the twentieth Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress in 1970. Early years Stafford was born in Hutchinson, Kansas, the oldest of three children in a highly literate family. During the Depression, his family moved from town to town in an effort to find work for his father. Stafford helped contribute to family income by delivering newspapers, working in sugar beet fields, raising vegetables, and working as an electrician's apprentice. During this time he had a near death experience in a local swimming hole. He graduated from high school in the town of Liberal, Kansas in 1933. After attending junior college, he received a B.A. from the University of Kansas in 1937. He was drafted into the United States armed forces in 1941, while pursuing his master's degree at the University of Kansas, but declared himself a conscientious objector. As a registered pacifist, he performed alternative service from 1942 to 1946 in the Civilian Public Service camps. The work consisted of forestry and soil conservation work in Arkansas, California, and Illinois for $2.50 per month. While working in California in 1944, he met and married Dorothy Hope Frantz with whom he later had four children (Bret, who died in 1988; Kim, writer; Kit, artist; Barbara, artist). He received his M.A. from the University of Kansas in 1947. His master's thesis, the prose memoir Down In My Heart, was published in 1948 and described his experience in the forest service camps. That same year he moved to Oregon to teach at Lewis & Clark College. In 1954, he received a Ph.D. from the University of Iowa. Stafford taught for one academic year (1955–1956) in the English department at Manchester College in Indiana, a college affiliated with the Church of the Brethren where he had received training during his time in Civilian Public Service. The following year (1956–57), he taught at San Jose State in California, and the next year returned to the faculty of Lewis & Clark. Career One striking feature of his career is its late start. Stafford was 46 years old when his first major collection of poetry was published, Traveling Through the Dark, which won the 1963 National Book Award for Poetry. The title poem is one of his best known works. It describes encountering a recently killed doe on a mountain road. Before pushing the doe into a canyon, the narrator discovers that she was pregnant and the fawn inside is still alive. Stafford had a quiet daily ritual of writing and his writing focuses on the ordinary. His gentle quotidian style has been compared to Robert Frost. Paul Merchant writes, "His poems are accessible, sometimes deceptively so, with a conversational manner that is close to everyday speech. Among predecessors whom he most admired are William Wordsworth, Thomas Hardy, Walt Whitman, and Emily Dickinson." His poems are typically short, focusing on the earthy, accessible details appropriate to a specific locality. Stafford said this in a 1971 interview: I keep following this sort of hidden river of my life, you know, whatever the topic or impulse which comes, I follow it along trustingly. And I don't have any sense of its coming to a kind of crescendo, or of its petering out either. It is just going steadily along. Stafford was a close friend and collaborator with poet Robert Bly. Despite his late start, he was a frequent contributor to magazines and anthologies and eventually published fifty-seven volumes of poetry. James Dickey called Stafford one of those poets "who pour out rivers of ink, all on good poems."[6] He kept a daily journal for 50 years, and composed nearly 22,000 poems, of which roughly 3,000 were published. In 1970, he was named Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress, a position that is now known as Poet Laureate. In 1975, he was named Poet Laureate of Oregon; his tenure in the position lasted until 1990. In 1980, he retired from Lewis & Clark College but continued to travel extensively and give public readings of his poetry. In 1992, he won the Western States Book Award for lifetime achievement in poetry. Death Stafford died of a heart attack in Lake Oswego, Oregon on August 28, 1993, having written a poem that morning containing the lines, "'You don't have to / prove anything,' my mother said. 'Just be ready / for what God sends.'" In 2008, the Stafford family gave William Stafford's papers, including the 20,000 pages of his daily writing, to the Special Collections Department at Lewis & Clark College. Kim Stafford, who serves as literary executor for the Estate of William Stafford, has written a memoir Early Morning: Remembering My Father, William Stafford (Graywolf Press). References Wikipedia—http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Stafford_(poet)

Gertrude Stein was born in Allegheny, Pennsylvania, on February 3, 1874, to wealthy German-Jewish immigrants. At the age of three, her family moved first to Vienna and then to Paris. They returned to America in 1878 and settled in Oakland, California. Her mother, Amelia, died of cancer in 1888 and her father, Daniel, died 1891. Stein attended Radcliffe College from 1893 to 1897, where she specialized in Psychology under noted psychologist William James. After leaving Radcliffe, she enrolled at the Johns Hopkins University, where she studied medicine for four years, leaving in 1901. Stein did not receive a formal degree from either institution. In 1903, Stein moved to Paris with Alice B. Toklas, a younger friend from San Francisco who would remain her partner and secretary throughout her life. The couple did not return to the United States for over thirty years. Together with Toklas and her brother Leo, an art critic and painter, Stein took an apartment on the Left Bank. Their home, 27 rue de Fleurus, soon became gathering spot for many young artists and writers including Henri Matisse, Ezra Pound, Pablo Picasso, Max Jacob, and Guillaume Apollinaire. She was a passionate advocate for the "new" in art, her literary friendships grew to include writers as diverse as William Carlos Williams, Djuana Barnes, F. Scott Fitzgerald, James Joyce, and Ernest Hemingway. It was to Hemingway that Stein coined the phrase "the lost generation" to describe the expatriate writers living abroad between the wars. By 1913, Stein's support of cubist painters and her increasingly avant-garde writing caused a split with her brother Leo, who moved to Florence. Her first book, Three Lives, was published in 1909. She followed it with Tender Buttons in 1914. Tender Buttons clearly showed the profound effect modern painting had on her writing. In these small prose poems, images and phrases come together in often surprising ways—similar in manner to cubist painting. Her writing, characterized by its use of words for their associations and sounds rather than their meanings, received considerable interest from other artists and writers, but did not find a wide audience. Sherwood Anderson in the introduction to Geography and Plays (1922) wrote that her writing "consists in a rebuilding, and entire new recasting of life, in the city of words." Among Stein's most influential works are The Making of Americans (1925); How to Write (1931); The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (1933), which was a best-seller; and Stanzas in Meditation and Other Poems [1929-1933] (1956). In 1934, the biographer T. S. Matthews described her as a "solid elderly woman, dressed in no-nonsense rough-spun clothes," with "deep black eyes that make her grave face and its archaic smile come alive." Stein died at the American Hospital at Neuilly on July 27, 1946, of inoperable cancer.

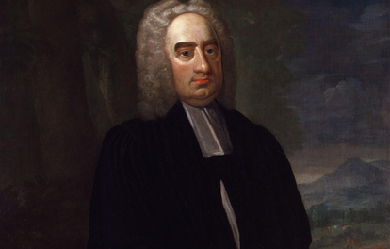

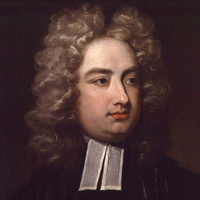

Jonathan Swift (30 November 1667– 19 October 1745) was an Anglo-Irish satirist, essayist, political pamphleteer (first for the Whigs, then for the Tories), poet and cleric who became Dean of St Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin. Swift is remembered for works such as Gulliver’s Travels, A Modest Proposal, A Journal to Stella, Drapier’s Letters, The Battle of the Books, An Argument Against Abolishing Christianity and A Tale of a Tub. He is regarded by the Encyclopædia Britannica as the foremost prose satirist in the English language, and is less well known for his poetry.

Welcome!! I have some emotions that have poetic symphony. I have some philosophy and my own stories and experiences in my own perspective; I have not judged them whether they are symmetrical with anyone or differentiate with others. I love writing about the bad luck I bear, the curse I fear and the death, ridiculously, I dare. I am grateful if you read - just like a sudden visitor of an unknown grave, someone came, stood, smiled and wished - "Rest In Peace". I was born in 1979, July 26 just at 12 am. I have no siblings. My two assets are everything, One I lost in 2004; My father; Still one I have, My mother. I am an MBA of University of Chittagong. I have served a lot of companies, Branded-Non branded, Multinational-Local, Authorized-Unknown, Financial-Not Financial, Established-Liquidated, Rising-Falling, Fortunate-Misfortune, Proprietor-Public etc. I like job devotion, I hate impose of discrimination, I am always leader at the beginning, however demonstrator at the ending. I belief Pragmatic is not Truth, Real means partial Truth. I decided to suicide. Before that, I want to keep my creation safe, where they will obscure but they will survive. I can never get the recognition. Better my creations need freedom anywhere in the world. So welcome again my friend before I decay. Thank you.

Charles Simic (born Dušan Simić; May 9, 1938) is a Serbian-American poet and was co-poetry editor of the Paris Review. He received the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1990 for The World Doesn’t End, and was a finalist of the Pulitzer Prize in 1986 for Selected Poems, 1963-1983 and in 1987 for Unending Blues. He was appointed the fifteenth Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress in 2007. Biography Early years Dušan Simić was born in Belgrade. In his early childhood, during World War II, he and his family were forced to evacuate their home several times to escape indiscriminate bombing of Belgrade. Growing up as a child in war-torn Europe shaped much of his world-view, Simic states. In an interview from the Cortland Review he said, “Being one of the millions of displaced persons made an impression on me. In addition to my own little story of bad luck, I heard plenty of others. I’m still amazed by all the vileness and stupidity I witnessed in my life.” Simic immigrated to the United States with his brother and mother in order to join his father in 1954 when he was sixteen. He grew up in Chicago. In 1961 he was drafted into the U.S. Army, and in 1966 he earned his B.A. from New York University while working at night to cover the costs of tuition. He is professor emeritus of American literature and creative writing at the University of New Hampshire, where he has taught since 1973 and lives on the shore of Bow Lake in Strafford, New Hampshire. Career He began to make a name for himself in the early to mid-1970s as a literary minimalist, writing terse, imagistic poems. Critics have referred to Simic’s poems as “tightly constructed Chinese puzzle boxes”. He himself stated: “Words make love on the page like flies in the summer heat and the poet is merely the bemused spectator.” Simic writes on such diverse topics as jazz, art, and philosophy. He is a translator, essayist and philosopher, opining on the current state of contemporary American poetry. He held the position of poetry editor of The Paris Review and was replaced by Dan Chiasson. He was elected to The American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1995, received the Academy Fellowship in 1998, and was elected a Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets in 2000. Simic was one of the judges for the 2007 Griffin Poetry Prize and continues to contribute poetry and prose to The New York Review of Books. Simic received the US$100,000 Wallace Stevens Award in 2007 from the Academy of American Poets. He was selected by James Billington, Librarian of Congress, to be the fifteenth Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress, succeeding Donald Hall. In choosing Simic as the poet laureate, Billington cited “the rather stunning and original quality of his poetry”. In 2011, he was the recipient of the Frost Medal, presented annually for “lifetime achievement in poetry.” Awards * PEN Translation Prize (1980) * Ingram Merrill Foundation Fellowship (1983) * MacArthur Fellowship (1984–1989) * Pulitzer Prize finalist (1986) * Pulitzer Prize finalist (1987) * Pulitzer Prize for Poetry (1990) * Wallace Stevens Award (2007) * Frost Medal (2011) * Vilcek Prize in Literature (2011) * The Zbigniew Herbert International Literary Award (2014) * Golden Wreath of the Struga Poetry Evenings (2017) Bibliography References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Simic

Hi, my name is, Paul Schreiner. I was born somewhere in the country of, Brasil. I don't know when or even where, I was born. Or who my biological parents may be. In fact, nobody in the American or the Brasilian government, really knows who I am or anything about me or my past. All that is known, is how I miraculously appeared in an orphanage with no birth certificate, due to my sister and I being kidnapped for sex trafficking. In 1988, my two loving parents flew down from America to Brasil, and adopted me. They gave me a name, a birthday, a home, a new country, and most of all, a family to call my own! Since I was a child, in a foreign country with no one to communicate with; I gravitated towards books, the Encyclopedia, history, and poetry. For some reason, I was able to comprehend the English language and it's structure more easily, through poetry. I love and appreciate poetry, because in a way, it explains an emotion, thoughts, or just life, in a way no other written structure can. I am so grateful for sights like these! It's sad, because poetry, I believe, is a dying art. Sights like these keep it alive and well for poets and fans, like ourselves. I hope you enjoy some of mine, almost as much as I enjoyed writing them! Go write on!!

Jack Spicer (January 30, 1925– August 17, 1965) was an American poet often identified with the San Francisco Renaissance. In 2009, My Vocabulary Did This to Me: The Collected Poetry of Jack Spicer won the American Book Award for poetry. Life and work Spicer was born in Los Angeles, where he later graduated from Fairfax High School in 1942, and attended the University of Redlands from 1943-45. He spent most of his writing-life in San Francisco and spent the years 1945 to 1950 and 1952 to 1955 at the University of California, Berkeley, where he began writing, doing work as a research-linguist, and publishing some poetry (though he disdained publishing). During this time he searched out fellow poets, but it was through his alliance with Robert Duncan and Robin Blaser that Spicer forged a new kind of poetry, and together they referred to their common work as the Berkeley Renaissance. The three, who were all gay, also educated younger poets in their circle about their “queer genealogy”, Rimbaud, Lorca, and other gay writers. Spicer’s poetry of this period is collected in One Night Stand and Other Poems (1980). His Imaginary Elegies, later collected in Donald Allen’s The New American Poetry 1945-1960 anthology, were written around this time. In 1954, he co-founded the Six Gallery in San Francisco, which soon became famous as the scene of the October 1955 Six Gallery reading that launched the West Coast Beat movement. In 1955, Spicer moved to New York and then to Boston, where he worked for a time in the Rare Book Room of Boston Public Library. Blaser was also in Boston at this time, and the pair made contact with a number of local poets, including John Wieners, Stephen Jonas, and Joe Dunn. Spicer returned to San Francisco in 1956 and started working on After Lorca. This book represented a major change in direction for two reasons. Firstly, he came to the conclusion that stand-alone poems (which Spicer referred to as his one-night stands) were unsatisfactory and that henceforth he would compose serial poems. In fact, he wrote to Blaser that 'all my stuff from the past (except the Elegies and Troilus) looks foul to me.' Secondly, in writing After Lorca, he began to practice what he called “poetry as dictation”. His interest in the work of Federico García Lorca, especially as it involved the cante jondo ideal, also brought him near the poetics of the deep image group. The Troilus referred to was Spicer’s then unpublished play of that name. The play finally appeared in print in 2004, edited by Aaron Kunin, in issue 3 of No - A Journal of the Arts. In 1957, Spicer ran a workshop called Poetry as Magic at San Francisco State College, which was attended by Duncan, Helen Adam, James Broughton, Joe Dunn, Jack Gilbert, and George Stanley. He also participated in, and sometimes hosted, Blabbermouth Night at a literary bar called The Place. This was a kind of contest of improvised poetry and encouraged Spicer’s view of poetry as being dictated to the poet. After many years of alcohol abuse, Spicer fell into a prehepatic coma in his apartment building elevator, and later died aged 40 in the poverty ward of San Francisco General Hospital on August 17, 1965. Legacy Spicer’s view of the role of language in the process of writing poetry was probably the result of his knowledge of modern pre-Chomskyan linguistics and his experience as a research-linguist at Berkeley. In the legendary Vancouver lectures he elucidated his ideas on “transmissions” (dictations) from the Outside, using the comparison of the poet as crystal-set or radio receiving transmissions from outer space, or Martian transmissions. Although seemingly far-fetched, his view of language as “furniture”, through which the transmissions negotiate their way, is grounded in the structuralist linguistics of Zellig Harris and Charles Hockett. (In fact, the poems of his final book, Language, refer to linguistic concepts such as morphemes and graphemes). As such, Spicer is acknowledged as a precursor and early inspiration for the Language poets. However, many working poets today list Spicer in their succession of precedent figures. Spicer died as a result of his alcoholism. Since the posthumous publication of The Collected Books of Jack Spicer (first published in 1975), his popularity and influence has steadily risen, affecting poetry throughout the United States, Canada, and Europe. In 1994, The Tower of Babel: Jack Spicer’s Detective Novel was published. Adding to the Jack Spicer revival was the publication in 1998 of two volumes: The House That Jack Built: The Collected Lectures of Jack Spicer, edited by Peter Gizzi; and a biography: Jack Spicer and the San Francisco Renaissance by Lewis Ellingham and Kevin Killian (Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press, 1998). A collected works entitled My Vocabulary Did This to Me: The Collected Poetry of Jack Spicer (Peter Gizzi and Kevin Killian, editors) was published by Wesleyan University Press in November 2008, and won the American Book Award in 2009. A collection of critical essays entitled After Spicer: Critical Essays (John Emil Vincent, editor) was published by Wesleyan University Press in 2011. Further reading Blaser, Robin, editor. The Collected Books of Jack Spicer. Santa Rosa, Calif.: Black Sparrow Press, 1975 A Book Of Correspondences For Jack Spicer. Edited By David Levi Strauss and Benjamin Hollander. San Francisco: A Journal of Acts (#6), 1987; (Note: this is a collection of essays, poetry, and documents celebrating Spicer) Diaman, N. A.. Following My Heart: A Memoir. San Francisco: Persona Press, May 2007 _____. The City: A Novel. San Francisco: Persona Press, August 2007 _____. Sitting With Jack At The Poets Table. Los Angeles: The Advocate, 1984 _____. Second Crossing: A Novel. San Francisco: Persona Press, 1982 Ellingham, Lewis, and Kevin Killian. Poet, Be Like God: Jack Spicer and the San Francisco Renaissance. Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 1998 Foster, Edward Halsey. Jack Spicer. Boise, Idaho: Boise State University, 1991 Gizzi, Peter, editor. The House that Jack Built: The Collected Lectures of Jack Spicer. Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press, 1998 Spicer, Jack. Jack Spicer’s Beowulf, Part 1, edited by David Hadbawnik & Sean Reynolds, introduction by David Hadbawnik, Lost and Found: The CUNY Poetics Documents Initiative, New York, 2011 _____. Jack Spicer’s Beowulf, Part II, edited by David Hadbawnik & Sean Reynolds, afterword by Sean Reynolds, Lost and Found: The CUNY Poetics Documents Initiative, New York, 2011 Tallman, Warren. In the Midst. Vancouver: Talonbooks, 1992 Herndon, James. Everything as Expected San Francisco, 1973 Vincent, John Emil, editor. After Spicer: Critical Essays. Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 2011 References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jack_Spicer

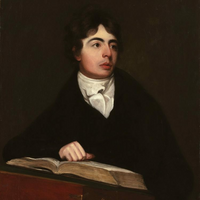

Robert Southey (/ˈsaʊði/ or /ˈsʌði/; August 12, 1774 in Bristol– March 21, 1843 in London) was an English poet of the Romantic school, one of the so-called “Lake Poets”, and Poet Laureate for 30 years from 1813 to his death in 1843. Although his fame has long been eclipsed by that of his contemporaries and friends William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Southey’s verse still enjoys some popularity. Southey was also a prolific letter writer, literary scholar, essay writer, historian and biographer. His biographies include the life and works of John Bunyan, John Wesley, William Cowper, Oliver Cromwell and Horatio Nelson. The last has rarely been out of print since its publication in 1813 and was adapted for the screen in the 1926 British film, Nelson. He was also a renowned scholar of Portuguese and Spanish literature and history, translating a number of works from those two languages into English and writing a History of Brazil (part of his planned History of Portugal, which he never completed) and a History of the Peninsular War. Perhaps his most enduring contribution to literary history is the children’s classic The Story of the Three Bears, the original Goldilocks story, first published in Southey’s prose collection The Doctor. He also wrote on political issues which led to a brief, non-sitting, spell as a Tory Member of Parliament. Life Robert Southey was born in Wine Street, Bristol, England, to Robert Southey and Margaret Hill. He was educated at Westminster School, London, (where he was expelled for writing an article in The Flagellant condemning flogging) and Balliol College, Oxford. Southey later said of Oxford, “All I learnt was a little swimming... and a little boating.” Experimenting with a writing partnership with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, most notably in their joint composition of The Fall of Robespierre, Southey published his first collection of poems in 1794. The same year, Southey, Coleridge, Robert Lovell and several others discussed creating an idealistic community ("pantisocracy") on the banks of the Susquehanna River in America: Southey was the first to reject the idea as unworkable, suggesting that they move the intended location to Wales, but when they failed to agree the plan was abandoned. In 1799 Southey and Coleridge were involved with early experiments with nitrous oxide (laughing gas), conducted by the Cornish scientist Humphry Davy. Southey married Edith Fricker at St. Mary Redcliffe, Bristol, on 14 November 1795. She was a sister of Sara Fricker, Coleridge’s wife. The Southeys made their home at Greta Hall, Keswick, in the Lake District, living on his tiny income. Also living at Greta Hall and supported by him were Sara Coleridge and her three children, after Coleridge abandoned them, as well as the widow of poet Robert Lovell and her son. In 1808 Southey met Walter Savage Landor, whose work he admired, and they became close friends. That same year he wrote Letters from England under the pseudonym Don Manuel Alvarez Espriella, an account of a tour supposedly from a foreigner’s viewpoint. It is considered to present the most accurate picture of English ways at the beginning of the 19th century. From 1809, Southey contributed to the Quarterly Review. He had become so well known by 1813 that he was appointed Poet Laureate after Walter Scott refused the post. In 1819, through a mutual friend (John Rickman), Southey met the leading civil engineer Thomas Telford and struck up a strong friendship. From mid-August to 1 October 1819, Southey accompanied Telford on an extensive tour of his engineering projects in the Scottish Highlands, keeping a diary of his observations. This was published in 1929 as Journal of a Tour in Scotland in 1819. He was also a friend of the Dutch poet Willem Bilderdijk, whom he met twice, in 1824 and 1826, at Bilderdijk’s home in Leiden. In 1837 Southey received a letter from Charlotte Brontë, seeking his advice on some of her poems. He wrote back praising her talents, but also discouraging her from writing professionally. He said “Literature cannot be the business of a woman’s life”. Years later, Brontë remarked to a friend that the letter was “kind and admirable; a little stringent, but it did me good.” In 1838, Edith died and Southey remarried, to Caroline Anne Bowles, also a poet, on 4 June 1839. Southey’s mind was giving way when he wrote a last letter to his friend Landor in 1839, but he continued to mention Landor’s name when generally incapable of mentioning any one. He died on 21 March 1843 and was buried in the churchyard of Crosthwaite Church, Keswick, where he had worshipped for forty years. There is a memorial to him inside the church, with an epitaph written by his friend, William Wordsworth. Many of his poems are still read by British schoolchildren, the best-known being The Inchcape Rock, God’s Judgement on a Wicked Bishop, After Blenheim (possibly one of the earliest anti-war poems) and Cataract of Lodore. As a prolific writer and commentator, Southey introduced or popularised a number of words into the English language. The term autobiography, for example, was used by Southey in 1809 in the Quarterly Review in which he predicted an “epidemical rage for autobiography”, which indeed has continued to the present day. Politics Although originally a radical supporter of the French Revolution, Southey followed the trajectory of his fellow Romantic poets Wordsworth and Coleridge towards conservatism. Embraced by the Tory establishment as Poet Laureate, and from 1807 in receipt of a yearly stipend from them, he vigorously supported the Liverpool government. He argued against parliamentary reform ("the railroad to ruin with the Devil for driver"), blamed the Peterloo Massacre on the allegedly revolutionary “rabble” killed and injured by government troops, and opposed Catholic emancipation. In 1817 he privately proposed penal transportation for those guilty of “libel” or “sedition”. He had in mind figures like Thomas Jonathan Wooler and William Hone, whose prosecution he urged. Such writers were guilty, he wrote in the Quarterly Review, of “inflaming the turbulent temper of the manufacturer and disturbing the quiet attachment of the peasant to those institutions under which he and his fathers have dwelt in peace.” Wooler and Hone were acquitted, but the threats caused another target, William Cobbett, to emigrate temporarily to the United States. In some respects, however, Southey was ahead of his time in his views on social reform. For example, he was an early critic of the evils which the new factory system brought to early 19th-century Britain. He was appalled by the conditions of life in towns like Birmingham and Manchester, and especially by the employment of children in factories, and was outspoken in his criticism of these things. He sympathised with the pioneering socialist plans of Robert Owen, advocated that the state promote public works to maintain high employment and called for universal education. Given his departure from radicalism, and his attempts to have former fellow travellers prosecuted, it is unsurprising that less successful contemporaries who kept the faith attacked Southey. They saw him as a selling out for money and respectability. In 1817 Southey was confronted with the surreptitious publication of a radical play, Wat Tyler, which he had written in 1794 at the height of his radical period. This was instigated by his enemies in an attempt to embarrass the Poet Laureate and highlight his apostasy from radical poet to supporter of the Tory establishment. One of his most savage critics was William Hazlitt. In his portrait of Southey, in The Spirit of the Age, he wrote: “He wooed Liberty as a youthful lover, but it was perhaps more as a mistress than a bride; and he has since wedded with an elderly and not very reputable lady, called Legitimacy.” Southey largely ignored his critics but was forced to defend himself when William Smith, a member of Parliament, rose in the House of Commons on 14 March to attack him. In a spirited response Southey wrote an open letter to the MP, in which he explained that he had always aimed at lessening human misery and bettering the condition of all the lower classes and that he had only changed in respect of “the means by which that amelioration was to be effected.” As he put it, “that as he learnt to understand the institutions of his country, he learnt to appreciate them rightly, to love, and to revere, and to defend them.” He was often mocked for what were seen as sycophantic odes to the king, most notably in Byron’s long ironic dedication of Don Juan to Southey. In the poem Southey is dismissed as insolent, narrow and shabby. This was based both on Byron’s disrespect for Southey’s literary talent, and his disdain for what he perceived as Southey’s hypocritical turn to conservative politics later in life. The source of much of the animosity between the two men can be traced back to Byron’s belief that Southey had spread rumours about him and Percy Shelley being in a “League of Incest” during their time on Lake Geneva in 1816, an accusation that Southey strenuously denied. In response, Southey attacked what he called the Satanic School among modern poets in the preface to his poem, A Vision of Judgement, written following the death of George III. While not referring to Byron by name, it was clearly directed at him, and Byron retaliated with The Vision of Judgment, a brilliant parody of Southey’s poem. Without his prior knowledge, the Earl of Radnor, an admirer of his work, had Southey returned as MP for the latter’s pocket borough seat of Downton in Wiltshire at the 1826 general election as an opponent of Catholic emancipation. However Southey refused to sit in the House of Commons, causing a by-election in December that year, pleading he did not have a large enough estate to support him through political life, did not want to take on the hours full attendance required, wanted to continue living in the Lake District, and preferred to defend the Church of England in writing rather than speech. He declared that ‘for me to change my scheme of life and go into Parliament, would be to commit a moral and intellectual suicide’; and his friend John Rickman, a Commons clerk, noted that ‘prudential reasons would forbid his appearing in London’ as a Member. In 1835 he declined the offer of a baronetcy but accepted a life pension of £300 a year from Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel. Southey is buried in the churchyard of Crosthwaite Parish Church in Cumbria. Honours and Memberships Elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1822. Member of the Royal Spanish Academy. List of works * The Fall of Robespierre (1794) * Joan of Arc (1796) * Icelandic Poetry, or The Edda of Sæmund (1797) * Poems (1797–1799) * Letters Written During a Short Residence in Spain and Portugal (1797) * St. Patrick’s Purgatory (1798) * After Blenheim (1798) * The Devil’s Thoughts (1799). Revised ed. pub. in 1827 as “The Devil’s Walk”. * English Eclogues (1799) * The Old Man’s Comforts and How He Gained Them (1799) * Thalaba the Destroyer (1801) * The Inchcape Rock (1802) * Madoc (1805) * Letters from England: By Don Manuel Alvarez Espriella (1807), the observations of a fictitious Spaniard. * Chronicle of the Cid, from the Spanish (1808) * The Curse of Kehama (1810) * History of Brazil (3 vols.) (1810–1819) * The Life of Horatio, Lord Viscount Nelson (1813) * Roderick the Last of the Goths (1814) * Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte D’Arthur (1817) * Wat Tyler: A Dramatic Poem (1817) * Cataract of Lodore (1820) * The Life of Wesley; and Rise and Progress of Methodism (2 vols.) (1820) * What Are Little Boys Made Of? (1820) * The Vision of Judgement (1821) * History of the Peninsular War, 1807-1814 (3 vols.) (1823-1832) * Sir Thomas More; or, Colloquies on the Progress and Prospects of Society (1829) * The Works of William Cowper (15 vols.) (ed.) (1833-1837) * Lives of the British Admirals, with an Introductory View of the Naval History of England (5 vols.) (1833-40); republished as “English Seamen” in 1895. * The Doctor (7 vols.) (1834-1847). Includes The Story of the Three Bears (1837). * The Poetical Works of Robert Southey, Collected by Himself (1837) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Southey

Receiving my graduate degree from JFK University in Consciousness and the Arts and undergraduate education in Language and Sociology from Howard University, my contributions to society include: improving the status of women in the American Society, consulting on family education and management. Before retiring, I worked as the Secretary for the U.S. Treasury, Proofreader for the Office of the Price Administration and was a Researcher and Public Relations Director for the Eisenhower Congressional Committee. I am now a Professional Volunteer. Some of my achievements are as follows: Senior Senator to the California Senior Legislature Past Presidency and/or Advisor: AAUW, Business and Professional Women, Richmond Plaza Neighborhood Council, Council for Civic Unity, Advisory Council on Aging, Mental Health Task Force on Aging, Elder Abuse Consortium, Ethnic and Handicapped Task Force. I am a proud parent of three children and grandparent of four grandchildren and I share my life with Joe, my husband, who retired as a General Dentist.

Delmore Schwartz (December 8, 1913– July 11, 1966) was an American poet and short story writer. Biography Schwartz was born in 1913 in Brooklyn, New York, where he also grew up. His parents, Harry and Rose, both Romanian Jews, separated when Schwartz was nine, and their divorce had a profound effect on him. In 1930, Schwartz’s father suddenly died at the age of 49. Though Harry had accumulated a good deal of wealth from his dealings in the real estate business, Delmore only inherited a small amount of that money as the result of the shady dealings of the executor of Harry’s estate. According to Schwartz’s biographer, James Atlas, "Delmore continued to hope that he would eventually receive his legacy [even] as late as 1946.” Schwartz spent time at Columbia University and the University of Wisconsin before finally graduating from New York University in 1935. He then did some graduate work in philosophy at Harvard University, where he studied with the philosopher Alfred North Whitehead, but left and returned to New York without receiving a degree. Soon thereafter, he made his parents’ disastrous marriage the subject of his most famous short story, “In Dreams Begin Responsibilities”, which was published in 1937 in the first issue of Partisan Review. This story and other short stories and poems became his first book, also entitled In Dreams Begin Responsibilities, published in 1938 when Schwartz was only 25 years old. The book was well received, and made him a well-known figure in New York intellectual circles. His work received praise from some of the most respected people in literature, including T. S. Eliot, William Carlos Williams, and Ezra Pound, and Schwartz was considered one of the most gifted and promising young writers of his generation. According to James Atlas, Allen Tate responded to the book by stating that "[Schwartz’s] poetic style marked 'the first real innovation we’ve had since Eliot and Pound.'” In 1937, he also married Gertrude Buckman, a book reviewer for Partisan Review, whom he divorced after six years. For the next couple of decades, he continued to publish stories, poems, plays, and essays, and edited the Partisan Review from 1943 to 1955, as well as The New Republic. Schwartz was deeply upset when his epic poem, Genesis, which he published in 1943 and hoped would stand alongside other Modernist epics like The Waste Land and The Cantos as a masterpiece, received a negative critical response. Later, in 1948, he married the much younger novelist, Elizabeth Pollet. This relationship also ended in divorce. In 1959, he became the youngest-ever recipient of the Bollingen Prize, awarded for a collection of poetry he published that year, Summer Knowledge: New and Selected Poems. His poetry differed from his stories in that it was less autobiographical and more philosophical. His verse also became increasingly abstract in his later years. He taught creative writing at six universities, including Syracuse, Princeton, and Kenyon College. In addition to being known as a gifted writer, Schwartz was considered a great conversationalist and spent much time entertaining friends at the White Horse Tavern in New York City. Much of Schwartz’s work is notable for its philosophical and deeply meditative nature, and the literary critic, R.W. Flint, wrote that Schwartz’s stories were “the definitive portrait of the Jewish middle class in New York during the Depression.” In particular, Schwartz emphasized the large divide that existed between his generation (which came of age during the Depression) and his parents’ generation (who had often come to the United States as first-generation immigrants and whose idealistic view of America differed greatly from his own). In another take on Schwartz’s fiction, Morris Dickstein wrote that “Schwartz’s best stories are either poker-faced satirical takes on the bohemians and outright failures of his generation, as in 'The World Is a Wedding’ and 'New Year’s Eve,' or chronicles of the distressed lives of his parents’ generation, for whom the promise of American life has not panned out.” Schwartz was unable to repeat or build on his early successes later in life as a result of alcoholism and mental illness, and his last years were spent in reclusion at the Columbia Hotel in New York City. In fact, Schwartz was so isolated from the rest of the world that when he died on July 11, 1966, at age 52, of a heart attack, two days passed before his body was identified at the morgue. Schwartz was interred at Cedar Park Cemetery, in Emerson, New Jersey. A selection of his short stories was published posthumously in 1978 under the title In Dreams Begin Responsibilities and Other Stories and was edited by James Atlas who had written a biography of Schwartz, Delmore Schwartz: The Life of An American Poet, two years earlier. Later, another collection of Schwartz’s work, Screeno: Stories & Poems, was published in 2004. This collection contained fewer stories than In Dreams Begin Responsibilities and Other Stories but it also included a selection of some of Schwartz’s best-known poems like “The Heavy Bear Who Goes With Me” and “In The Naked Bed, In Plato’s Cave”. Screeno also featured an introduction by the fiction writer and essayist, Cynthia Ozick. Tributes to Schwartz One of the earliest well-known tributes to Schwartz came from Schwartz’s friend, fellow poet Robert Lowell, who published the poem “To Delmore Schwartz” in 1959 (while Schwartz was still alive) in the book Life Studies. In it Lowell reminisces about the time that the two poets lived together in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1946, writing that they were "underseas fellows, nobly mad,/ we talked away our friends.” One year following Schwartz’s death, in 1967, his former student at Syracuse University, the rock musician Lou Reed, dedicated his song “European Son” to Schwartz (although the lyrics themselves made no direct reference to Schwartz). Then, in 1968, Schwartz’s friend and peer, fellow poet John Berryman, dedicated his book His Toy, His Dream, His Rest “to the sacred memory of Delmore Schwartz,” including 12 elegiac poems about Schwartz in the book. In "Dream Song #149," Berryman wrote of Schwartz, In the brightness of his promise, unstained, I saw him thro’ the mist of the actual blazing with insight, warm with gossip thro’ all our Harvard years when both of us were just becoming known I got him out of a police-station once, in Washington, the world is tref and grief too astray for tears. The most ambitious literary tribute to Schwartz came in 1975 when Saul Bellow, a one-time protégé of Schwartz’s, published his Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Humboldt’s Gift which was based on his relationship with Schwartz. Although the character of Von Humboldt Fleischer is Bellow’s portrait of Schwartz during Schwartz’s declining years, the book is actually a testament to Schwartz’s lasting artistic influence on Bellow. Although he is a genius, the Fleischer/Schwartz character struggles financially and has trouble finding a secure university teaching position. He becomes increasingly paranoid and jealous of the success of the main character, Charlie Citrine (who is based upon Bellow himself), becoming isolated and descending into alcoholism and madness. Lou Reed’s 1982 album The Blue Mask included his second Schwartz homage with the song “My House”. The song is a more direct tribute to Schwartz than the above-mentioned “European Son” in that the lyrics of “My House” are about Reed’s relationship with Schwartz. In the song, Reed writes that Schwartz “was the first great man that I ever met”. Much later, in the June 2012 issue of Poetry magazine, Lou Reed published a short prose tribute to Schwartz entitled “O Delmore How I Miss You.” In the piece, Reed quotes and references a number of Schwartz’s short stories and poems including “In Dreams Begin Responsibilities,” “The World is a Wedding,” and “The Heavy Bear Who Goes With Me.” “O Delmore How I Miss You” was re-published as the preface to the New Directions 2012 reissue of Schwartz’s posthumously published story collection In Dreams Begin Responsibilities and Other Stories. In John A. McDermott’s poetry collection, The Idea of God in Tennessee, he includes a poem written for and referencing Schwartz, titled The Poet’s Body, Unclaimed in the Manhattan Morgue. The poem makes mention of Schwartz’s writing, daily habits, and death. Cultural references Scott Spencer uses the final six lines of Schwartz’s poem “I Am a Book I Neither Wrote nor Read” as an epigraph for his National Book Award nominated novel, Endless Love. The words “endless love” are the final two words of that poem. In the film Star Trek Generations, the villain Tolian Soran quotes from Schwartz’s poem, “Calmly We Walk Through This April’s Day”, telling Captain Jean-Luc Picard, “They say time is the fire in which we burn.” Playwright Philip Ridley uses the same line as one of the epigraphs for his 2012 play Shivered. The German symphonic metal band Agathodaimon uses the line “Time is the fire” as the title to one of the songs on the album Phoenix. Grant Morrison named a story in his DC Comics miniseries Multiversity, Pax Americana, after the same line as well as quoting it on the cover. In 1996, Donald Margulies wrote the play Collected Stories, in which the aging writer and teacher Ruth Steiner (a fictional character) reveals that she once had a great affair in her youth with Delmore Schwartz in Greenwich Village (during the period of time when Schwartz was in declining health from alcoholism and mental illness) to her young student, Lisa. Lisa then controversially uses the affair revelation as the basis for a successful novel. The play was produced twice off-Broadway and once on Broadway. Published works The Poets’ Pack (Rudge, New York, 1932), school anthology including four poems by Schwartz. In Dreams Begin Responsibilities. (New Directions, 1938), ISBN 978-0-8112-0680-8, a collection of short stories and poems. Shenandoah and Other Verse Plays (New Directions, 1941). Genesis: Book One (New Directions, 1943), book-length poem about the growth of a human being. The World Is a Wedding (New Directions, 1948), a collection of short stories. Vaudeville for a Princess and Other Poems (New Directions, 1950). Summer Knowledge: New and Selected Poems. (New Directions, 1959; reprinted 1967), ISBN 978-0-8112-0191-9. Successful Love and Other Stories (Corinth Books, 1961; Persea Books, 1985), ISBN 978-0-89255-094-4 Published posthumously Donald Dike, David Zucker (ed.) Selected Essays (1970; University of Chicago Press, 1985), ISBN 978-0-226-74214-4 In Dreams Begin Responsibilities and Other Stories (New Directions, 1978), a short story collection. Letters of Delmore Schwartz, ed. Robert Phillips (1984) ISBN 978-0-86538-048-6 The Ego Is Always at the Wheel: Bagatelles, ed. Robert Phillips (1986), a collection of humorously whimsical short essays Last and Lost Poems. ed. Robert Phillips (New Directions, 1989) ISBN 978-0-8112-1096-6 Screeno: Stories & Poems. New Directions. 2004. ISBN 978-0-8112-1573-2. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Delmore_Schwartz

Florence Margaret Smith, known as Stevie Smith (20 September 1902– 7 March 1971) was an English poet and novelist. Life Stevie Smith, born Florence Margaret Smith in Kingston upon Hull, was the second daughter of Ethel and Charles Smith. She was called “Peggy” within her family, but acquired the name “Stevie” as a young woman when she was riding in the park with a friend who said that she reminded him of the jockey Steve Donoghue. Her father was a shipping agent, a business that he had inherited from his father. As the company and his marriage began to fall apart, he ran away to sea and Smith saw very little of her father after that. He appeared occasionally on 24-hour shore leave and sent very brief postcards ("Off to Valparaiso, Love Daddy"). When she was three years old she moved with her mother and sister to Palmers Green in North London where Smith would live until her death in 1971. She resented the fact that her father had abandoned his family. Later, when her mother became ill, her aunt Madge Spear (whom Smith called “The Lion Aunt”) came to live with them, raised Smith and her elder sister Molly and became the most important person in Smith’s life. Spear was a feminist who claimed to have “no patience” with men and, as Smith wrote, “she also had 'no patience’ with Hitler”. Smith and Molly were raised without men and thus became attached to their own independence, in contrast to what Smith described as the typical Victorian family atmosphere of “father knows best”. When Smith was five she developed tubercular peritonitis and was sent to a sanatorium near Broadstairs, Kent, where she remained for three years. She related that her preoccupation with death began when she was seven, at a time when she was very distressed at being sent away from her mother. Death and fear fascinated her and provide the subjects of many of her poems. Her mother died when Smith was 16. When suffering from the depression to which she was subject all her life she was so consoled by the thought of death as a release that, as she put it, she did not have to commit suicide. She wrote in several poems that death was “the only god who must come when he is called”. Smith suffered throughout her life from an acute nervousness, described as a mix of shyness and intense sensitivity. In the Poem “A House of Mercy”, she wrote of her childhood house in North London: It was a house of female habitation, Two ladies fair inhabited the house, And they were brave. For although Fear knocked loud Upon the door, and said he must come in, They did not let him in. Smith was educated at Palmers Green High School and North London Collegiate School for Girls. She spent the remainder of her life with her aunt, and worked as private secretary to Sir Neville Pearson with Sir George Newnes at Newnes Publishing Company in London from 1923 to 1953. Despite her secluded life, she corresponded and socialised widely with other writers and creative artists, including Elisabeth Lutyens, Sally Chilver, Inez Holden, Naomi Mitchison, Isobel English and Anna Kallin. After she retired from Sir Neville Pearson’s service following a nervous breakdown she gave poetry readings and broadcasts on the BBC that gained her new friends and readers among a younger generation. Sylvia Plath became a fan of her poetry and sent Smith a letter in 1962, describing herself as “a desperate Smith-addict.” Plath expressed interest in meeting in person but committed suicide soon after sending the letter. Smith was described by her friends as being naive and selfish in some ways and formidably intelligent in others, having been raised by her aunt as both a spoiled child and a resolutely autonomous woman. Likewise, her political views vacillated between her aunt’s Toryism and her friends’ left-wing tendencies. Smith was celibate for most of her life, although she rejected the idea that she was lonely as a result, alleging that she had a number of intimate relationships with friends and family that kept her fulfilled. She never entirely abandoned or accepted the Anglican faith of her childhood, describing herself as a “lapsed atheist”, and wrote sensitively about theological puzzles;"There is a God in whom I do not believe/Yet to this God my love stretches." Her 14-page essay of 1958, “The Necessity of Not Believing”, concludes: “There is no reason to be sad, as some people are sad when they feel religion slipping off from them. There is no reason to be sad, it is a good thing.” Smith died of a brain tumour on 7 March 1971. Her last collection, Scorpion and other Poems was published posthumously in 1972, and the Collected Poems followed in 1975. Three novels were republished and there was a successful play based on her life, Stevie, written by Hugh Whitemore. It was filmed in 1978 by Robert Enders and starred Glenda Jackson and Mona Washbourne. Fiction Smith wrote three novels, the first of which, Novel on Yellow Paper, was published in 1936. Apart from death, common subjects in her writing include loneliness; myth and legend; absurd vignettes, usually drawn from middle-class British life, war, human cruelty and religion. All her novels are lightly fictionalised accounts of her own life, which got her into trouble at times as people recognised themselves. Smith said that two of the male characters in her last book are different aspects of George Orwell, who was close to Smith. There were rumours that they were lovers; he was married to his first wife at the time. Novel on Yellow Paper (Cape, 1936) Smith’s first novel is structured as the random typings of a bored secretary, Pompey. She plays word games, retells stories from classical and popular culture, remembers events from her childhood, gossips about her friends and describes her family, particularly her beloved Aunt. As with all Smith’s novels, there is an early scene where the heroine expresses feelings and beliefs which she will later feel significant, although ambiguous, regret for. In Novel on Yellow Paper that belief is anti-Semitism, where she feels elation at being the “only Goy” at a Jewish party. This apparently throwaway scene acts as a timebomb, which detonates at the centre of the novel when Pompey visits Germany as the Nazis are gaining power. With horror, she acknowledges the continuity between her feeling “Hurray for being a Goy” at the party and the madness that is overtaking Germany. The German scenes stand out in the novel, but perhaps equally powerful is her dissection of failed love. She describes two unsuccessful relationships, first with the German Karl and then with the suburban Freddy. The final section of the novel describes with unusual clarity the intense pain of her break-up with Freddy. Over the Frontier (Cape, 1938) Smith herself dismissed her second novel as a failed experiment, but its attempt to parody popular genre fiction to explore profound political issues now seems to anticipate post-modern fiction. If anti-Semitism was one of the key themes of Novel on Yellow Paper, Over the Frontier is concerned with militarism. In particular, she asks how the necessity of fighting Fascism can be achieved without descending into the nationalism and dehumanisation that fascism represents. After a failed romance the heroine, Pompey, suffers a breakdown and is sent to Germany to recuperate. At this point the novel changes style radically, as Pompey becomes part of an adventure/spy yarn in the style of John Buchan or Dornford Yates. As the novel becomes increasingly dreamlike, Pompey crosses over the frontier to become a spy and soldier. If her initial motives are idealistic, she becomes seduced by the intrigue and, ultimately, violence. The vision Smith offers is a bleak one: “Power and cruelty are the strengths of our lives, and only in their weakness is there love.” The Holiday (Chapman and Hall, 1949) Smith’s final novel is her own favourite, and most fully realised. It is concerned with personal and political malaise in the immediate post-war period. Most of the characters are either employed in the army or civil service in post-war reconstruction, and its heroine, Celia, works for the Ministry as a cryptographer and propagandist. The Holiday describes a series of hopeless relationships. Celia and her cousin Caz are in love, but cannot pursue their affair since it is believed that, because of their parents’ adultery, they are half-brother and sister. Celia’s other cousin Tom is in love with her, Basil is love with Tom, Tom is estranged from his father, Celia’s beloved Uncle Heber, who pines for a reconciliation; and Celia’s best friend Tiny longs for the married Vera. These unhappy, futureless but intractable relationships are mirrored by the novel’s political concerns. The unsustainability of the British Empire and the uncertainty over Britain’s post-war role are constant themes, and many of the characters discuss their personal and political concerns as if they were seamlessly linked. Caz is on leave from Palestine and is deeply disillusioned, Tom goes mad during the war, and it is telling that the family scandal that blights Celia and Caz’s lives took place in India. Just as Pompey’s anti-semitism was tested in Novel on Yellow Paper, so Celia’s traditional nationalism and sentimental support for colonialism is challenged throughout The Holiday. Poetry Smith’s first volume of poetry, the self-illustrated A Good Time Was Had By All, was published in 1937 and established her as a poet. Soon her poems were found in periodicals. Her style was often very dark; her characters were perpetually saying “goodbye” to their friends or welcoming death. At the same time her work has an eerie levity and can be very funny though it is neither light nor whimsical. “Stevie Smith often uses the word 'peculiar’ and it is the best word to describe her effects” (Hermione Lee). She was never sentimental, undercutting any pathetic effects with the ruthless honesty of her humour. “A good time was had by all” itself became a catch phrase, still occasionally used to this day. Smith said she got the phrase from parish magazines, where descriptions of church picnics often included this phrase. This saying has become so familiar that it is recognised even by those who are unaware of its origin. Variations appear in pop culture, including “Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!” by the Beatles. Though her poems were remarkably consistent in tone and quality throughout her life, their subject matter changed over time, with less of the outrageous wit of her youth and more reflection on suffering, faith and the end of life. Her best-known poem is “Not Waving but Drowning”. She was awarded the Cholmondeley Award for Poets in 1966 and won the Queen’s Gold Medal for poetry in 1969. She published nine volumes of poems in her lifetime (three more were released posthumously).

Arthur William Symons (28 February 1865– 22 January 1945), was a British poet, critic and magazine editor. Life Born in Milford Haven, Wales, of Cornish parents, Symons was educated privately, spending much of his time in France and Italy. In 1884–1886 he edited four of Bernard Quaritch’s Shakespeare Quarto Facsimiles, and in 1888–1889 seven plays of the “Henry Irving” Shakespeare. He became a member of the staff of the Athenaeum in 1891, and of the Saturday Review in 1894, but his major editorial feat was his work with the short-lived Savoy. His first volume of verse, Days and Nights (1889), consisted of dramatic monologues. His later verse is influenced by a close study of modern French writers, of Charles Baudelaire, and especially of Paul Verlaine. He reflects French tendencies both in the subject-matter and style of his poems, in their eroticism and their vividness of description. Symons contributed poems and essays to The Yellow Book, including an important piece which was later expanded into The Symbolist Movement in Literature, which would have a major influence on William Butler Yeats and T. S. Eliot. From late 1895 through 1896 he edited, along with Aubrey Beardsley and Leonard Smithers, The Savoy, a literary magazine which published both art and literature. Noteworthy contributors included Yeats, George Bernard Shaw, and Joseph Conrad. Symons was also a member of the Rhymer’s Club founded by Yeats in 1890. In 1892, The Minister’s Call, Symons’s first play, was produced by the Independent Theatre Society– a private club– to avoid censorship by the Lord Chamberlain’s Office. In 1902 Symons made a selection from his earlier verse, published as Poems. He translated from the Italian of Gabriele D’Annunzio The Dead City (1900) and The Child of Pleasure (1898), and from the French of Émile Verhaeren The Dawn (1898). To The Poems of Ernest Dowson (1905) he prefixed an essay on the deceased poet, who was a kind of English Verlaine and had many attractions for Symons. In 1909 Symons suffered a psychotic breakdown, and published very little new work for a period of more than twenty years. His Confessions: A Study in Pathology (1930) has a moving description of his breakdown and treatment. Verse Days and Nights (1889) Silhouettes (1892) London Nights (1895) Amoris victima (1897) Images of Good and Evil (1899) Poems in 2 volumes.(Contains: The Loom of Dreams in the second Volume, 1901), (1902) Lyrics (1903) An anthology of poetry published in the USA only. A Book of Twenty Songs (1905) The Fool of the World and other Poems (1906) Knave of Hearts (1913). Poems written between 1894 and 1908. Love’s Cruelty (1923) Jezebel Mort, and other poems (1931) Essays An Introduction to the study of Browning (1886) Studies in Two Literatures (1897) Aubrey Beardsley: An Essay with a Preface (1898) The Symbolist Movement in Literature (1899; 1919) Cities (1903), word-pictures of Rome, Venice, Naples, Seville, etc. Plays, Acting and Music (1903) Studies in Prose and Verse (1904) Studies in Seven Arts (1906). Figures of Several Centuries (1916) Cities and Sea-Coasts and Islands (1918) Studies in the Elizabethan Drama (1919) Charles Baudelaire: A Study (1920) Dramatis Personae (1925 - US edition 1923) From Toulouse-Lautrec to Rodin (1929) Studies in Strange Souls (1929) Confessions: A Study in Pathology (1930). A book containing Symons’s description of his breakdown and treatment. Wanderings (1931) A Study of Walter Pater (1932) Fiction Spiritual Adventures (1905). With an autobiographical sketch. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arthur_Symons