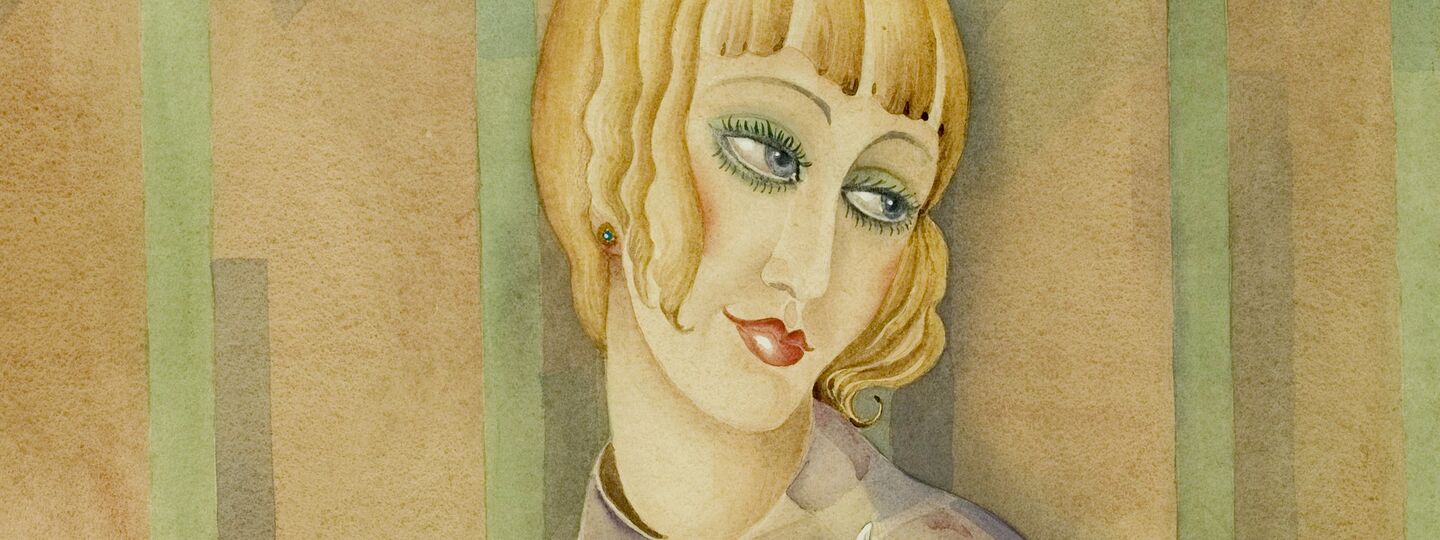

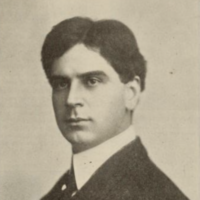

Arthur Stringer (February 26, 1874– September 13, 1950) was a Canadian novelist, screenwriter, and poet who later moved to the United States. He published 45 works of fiction and 15 other books, in addition to writing numerous filmscripts and articles. Life Stringer was born in Chatham, Ontario. “He was a high spirited boy who spent his childhood days fishing, swimming, raiding orchards and manning a pirate ship.” In 1884 the family moved to London, Ontario, where Charles attended London Collegiate Institute. At the Institute he founded and edited a school magazine called Chips. He then attended University College, University of Toronto from 1892 to 1894 and later studied at Oxford University. His first book of poetry, Watchers of Twilight and Other Poems, was published in 1894. In 1895 he worked for the Montreal Herald. At this time he was also publishing in Saturday Night and the Canadian Magazine. In 1898 he got a job with the American Press Association, moved to New York City, and was soon publishing in The Atlantic and Harper’s. His first poem in Harper’s, “Remorse”, appeared in February 1899. His first novel, The Silver Poppy, came out in 1903. In the same year he bought a farm on the shore of Lake Erie. and married actress Jobyna Howland, known as the original Gibson girl. They divorced in 1914, and Stringer married his cousin, Margaret Arbuthnott. Stringer was popular in his day for his crime fiction and his wilderness adventures, but he wrote in many genres, from social realism (his “Prairie” trilogy, 1915–1921) to psychological fiction (The Wine of Life (1921). He even wrote early science fiction novels, The Story Without a Name (1924) with Russell Holman, and The Woman Who Couldn’t Die (1929). Much of his writing was for films. Film scripts on which he worked include The Perils Of Pauline (1914), The Hand Of Peril (1916), The House Of Intrigue (1919), Unseeing Eyes (1923), Empty Hands (1924), The Canadian (1926), The Purchase Price (1932), The Lady Fights Back (1937), Buck Benny Rides Again (1940) and The Iron Claw (1941). Last years In 1921, the Stringers moved to Mountain Lakes, New Jersey, where Arthur Stringer continued to write, and where he died in 1950, aged 76. Writing Fiction Stringer was popular in his day for his crime fiction and his wilderness adventures, both of which rely to a large degree on formula; “generally he worked within the conventions of sentimental romance popular around the turn of the century.” Modern critics have not been kind to his fiction. For example, Douglas Fetherling wrote of him in the Canadian Encyclopedia: Stringer was not in any recognizable stream of Canadian writing but rather was a prolific American hack-fiction writer... The fact that he lived most of his life in the U.S., however, did not prevent him from frequently inventing Canadian characters and sometimes... setting them in the Far North, a region he misunderstood lavishly, thereby contributing to foreign stereotyping of Canada. Against that one has to set Stringer’s prairie trilogy– Prairie Wife (1915), Prairie Mother (1920), and Prairie Child (1921)– which has been called “an enduring contribution to Canadian literature.” The trilogy uses a diary form to tell the tale of its narrator, “a New England socialite married to a dour Scots-Canadian wheat farmer,” and “develops gradually from the optimism typical of pioneering romances, through disillusionment as her marriage deteriorates, to mature resolve as she begins an independent life on the Prairies.” Poetry The Oxford Companion to Canadian Literature described Stringer’s poetry as “undistinguished verse.” However, it was also said that in his poetry “there is maintained a standard of beauty, depth of feeling, and technical power, which in Canada have had all too little recognition.” At its time his blank verse drama Sappho in Leucadia was called “an imaginative, passionate, artistic work of surpassing quality”. Stringer’s chief claim to poetic fame today rests on his 1914 book, Open Water, the first book by a Canadian poet to use free verse– and in particular on his preface to that book, in which he “describes the modernist movement as a natural evolution.” Louis Dudek and Michael Gnarowski, who reprinted the Open Water preface in their anthology The Making of Modern Poetry In Canada, remarked on it: This book must be seen as a turning point in Canadian writing if only for the importance of the ideas advanced by Stringer in his preface. In a carefully presented, extremely well-informed account of traditional verse-making, Stringer pleaded the cause of free verse and created what must now be recognized as an early document of the struggle to free Canadian poetry from the trammels of end-rhyme, and to liberalize its methods and its substance. “Stringer’s arguments become even more striking from the point of view of literary history”, Dudek and Gnarowski continued, "if we recall... that the famous notes of F.S. Flint and the strictures of Ezra Pound on imagisme and free verse had appeared less than a year before this, in the March 1913 issue of Poetry: A Magazine of Verse (Chicago). Legacy Stringer was awarded an honorary D.Litt. by the University of Western Ontario in 1946. Stringer is commemorated by Arthur Stringer Public School in London, Ontario, which opened in 1969. The house in which Stringer lived as a boy in London, Ontario has been preserved as a historic site, Arthur Stringer House. Publications Fiction * The Silver Poppy. New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1903. * Lonely O’Malley: A Story of Boy Life. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1905. * The Wire Tappers. Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1906. * Phantom Wires. Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1907. * The Under Groove. New York: McClure Company, 1908. * The Gun-Runner. New York: B.W. Dodge & Co., 1909. * The Shadow. New York: The Century Co., 1913. * Never-Fail Blake Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, c.1913. * The Prairie Wife Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, c.1915. * The Hand of Peril. New York: Macmillan, April 1915. * The Door of Dread: A Secret Service Romance. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, c.1916. * The House of Intrigue. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, c.1918. * The Man Who Couldn’t Sleep. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, c.1919. * The Prairie Mother. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, c.1920. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1920. * Twin Tales: “Are All Men Alike” and “The Lost Titian”. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, c.1921. * The Wine of Life. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1921. * The Prairie Child. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, c.1922. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1923. * The Diamond Thieves. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, c.1923. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1925. * The City of Peril. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1923. * Empty Hands. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, c.1924. * and Russell Holman. Manhandled. (Illustrated with scenes from the photoplay). New York: Grossett & Dunlap, 1924. * and Russell Holman. The Story Without a Name. (Illustrated with scenes from the photoplay). New York: Grossett & Dunlap, 1924. * Power. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, c.1925. * In Bad With Sinbad. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1926. * Night Hawk. A Novel. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1926. * White Hands. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1927. * The Wolf Woman. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1927. * Cristina and I Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1929. * The Woman Who Couldn’t Die. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1929. * A Lady Quite Lost. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1931. * The Mud Lark. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1932. * Dark Soil. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1933. * Marriage by Capture. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1933. * Man Lost. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1934. * The Wife Traders: A Tale of the North. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1936. * Heather of the High Hand: A Novel of the North. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1937. * The Lamp In the Valley. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1938. * The Dark Wing. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1939. * The Ghost Plane: A Novel of the North. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1940. * A King Who Loved Old Clothes. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1941. * Intruders in Eden. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1942. * Shadowed Victory. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1943. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1944. * Star in a Mist. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1943. * The Devastator. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1944. * Information on early fiction from American fiction, 1901-1925. Non-fiction * A Study of King Lear. New York, 1897. * Red Wine of Youth: A Life of Rupert Brooke, 1921. Poetry * Watchers of Twilight, and Other Poems. London, ON: T.H. Warren, 1894. * Pauline and Other Poems. London, ON: T.H. Warren, 1895. * The Loom of Destiny. Boston: Small, Maynard, 1899. * The Woman in the Rain, and Other Poems. Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1907. 1949. * Irish Poems. New York: Mitchell Kennerley, 1911. * Out of Erin (Songs in Exile). Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1930. * Open Water. London: John Lane Co., 1914. * A Woman at Dusk and Other Poems. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1928. * The Old Woman Remembers and Other Irish Poems. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1938. * New York Nocturnes. Toronto: Ryerson P, 1948. Plays * Hephaestus: Persephone At Enna And Sappho In Leucadia. 1903 * The Cleverest Woman In the World and Other One-Act Dramas. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1939. Movies * The following 22 movies were based on fiction by Arthur Stringer: * 1912 The Man Who Made Good (short) (story) * 1914 The Case of Cherry Purcelle (short) (story) * 1916 The Secret Agent (short) (story) * 1916 The Breaker (story) * 1916 The Hand of Peril (novel The Hand of Peril: A Novel of Adventure) * 1918 From Two to Six (story “The Button Thief”) * 1919 The House of Intrigue (novel) * 1920 Are All Men Alike? (story “The Waffle Iron”) * 1923 Unseeing Eyes (story “Snowblind”) * 1924 Manhandled (story) * 1924 The Story Without a Name (novel) * 1924 Empty Hands (story) * 1925 The Prairie Wife (story) * 1925 Womanhandled (story) * 1926 The Canadian (story and scenario) * 1926 The Wilderness Woman (scenario / story) * 1926 Out of the Storm (story “The Travis Coup”) * 1928 Half a Bride (story “White Hands”) * 1932 The Purchase Price (story “The Mud Lark”) * 1937 The Lady Fights Back (novel “Heather of the High Hand”) * 1940 Buck Benny Rides Again (story) * 1941 The Iron Claw (story) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arthur_Stringer_(writer)

May Sarton is the pen name of Eleanore Marie Sarton ( (May 3, 1912– July 16, 1995), an American poet, novelist and memoirist. Biography Sarton was born in Wondelgem, Belgium (today a part of the city of Ghent). Her parents were science historian George Sarton and his wife, the English artist Mabel Eleanor Elwes. When German troops invaded Belgium after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in 1914, her family fled to Ipswich, England, where Sarton’s maternal grandmother lived. One year later, they moved to Boston, Massachusetts, where her father started working at Harvard University. She went to school in Cambridge, Massachusetts, graduating from Cambridge High and Latin School in 1929. She started theatre lessons in her late teens, but continued writing poetry. She published her first collection in 1937, entitled Encounter in April. In 1945 in Santa Fe, New Mexico, she met Judy Matlack, who became her partner for the next thirteen years. They separated in 1956, when Sarton’s father died and Sarton moved to Nelson, New Hampshire. Honey in the Hive (1988) is about their relationship. In her memoir At Seventy, Sarton reflected on Judy’s importance in her life and how her Unitarian Universalist upbringing shaped her. She was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1958. Sarton later moved to York, Maine. In 1990, she suffered a stroke, severely reducing her ability to concentrate and write. After several months, she was able to dictate her final journals, starting with Endgame, with the help of a tape recorder. She died of breast cancer on July 16, 1995, and is buried in Nelson, New Hampshire. Works and themes Despite the quality of some of her many novels and poems, May Sarton’s best and most enduring work probably lies in her journals and memoirs, particularly Plant Dreaming Deep (about her early years at Nelson, ca. 1958-68), Journal of a Solitude (1972-1973, often considered her best), The House by the Sea (1974-1976), Recovering (1978-1979) and At Seventy (1982-1983). In these fragile, rambling and honest accounts of her solitary life, she deals with such issues as aging, isolation, solitude, friendship, love and relationships, lesbianism, self-doubt, success and failure, envy, gratitude for life’s simple pleasures, love of nature (particularly of flowers), the changing seasons, spirituality and, importantly, the constant struggles of a creative life. Sarton’s later journals are not of the same quality, as she endeavoured to keep writing through ill health and by dictation. Although many of her earlier works, such as Encounter in April, contain vivid erotic female imagery, May Sarton often emphasized in her journals that she didn’t see herself as a “lesbian” writer, instead wanting to touch on what is universally human about love in all its manifestations. When publishing her novel Mrs. Stevens Hears the Mermaids Singing in 1965, she feared that writing openly about lesbianism would lead to a diminution of the previously established value of her work. “The fear of homosexuality is so great that it took courage to write Mrs. Stevens Hears the Mermaids Singing,” she wrote in Journal of a Solitude, “to write a novel about a woman homosexual who is not a sex maniac, a drunkard, a drug-taker, or in any way repulsive, to portray a homosexual who is neither pitiable nor disgusting, without sentimentality ...” After the book’s release, many of Sarton’s works began to be studied in university level women’s studies classes, being embraced by feminists and lesbians alike. However, Sarton’s work should not be classified as 'lesbian literature’ alone, as her works tackle many deeply human issues of love, loneliness, aging, nature, self-doubt etc., common to both men and women. Margot Peters’ controversial biography (1998) revealed May Sarton as a complex individual who often struggled in her relationships.

Poetry allows me to say all of the things that are in my heart and mind that I cannot express verbally. I feel most at home when I am in my notebook just writing what I feel. It is the most free I will ever be. We live in a world of constant rejection and criticism, so it's nice to be able to contribute something beautiful to world that is in desperate need of it.

Susan Frances Harrison née Riley (February 24, 1859– May 5, 1935) (a.k.a. Seranus) was a Canadian poet, novelist, music critic and music composer who lived and worked in Ottawa and Toronto. Life Susie Frances Riley was born in Toronto of Irish-Canadian ancestry, the daughter of John Byron Riley. She studied music with Frederic Boscovitz, at a private school for girls in Toronto, and later in Montreal. She reportedly began publishing poetry, in the Canadian Illustrated News, at 16 under the pseudonym “Medusa.” After completing her education, she worked as a pianist and singer. In 1880 she married organist John W. F. Harrison, of Bristol, England, who was the organist of St. George’s Church in Montreal. The couple had a son and a daughter. The Harrisons lived in Ottawa in 1883, when Susie Harrison composed the song “Address of Welcome to Lord Lansdowne” to celebrate the first public appearance of the new Governor General, the Marquess of Lansdowne. In 1887 the Harrisons moved to Toronto, where John Harrison became organist and choirmaster of St. Simon the Apostle, and Susan Harrison began a literary career under the pseudonym “Seranus” (a misreading of her signature, “S. Frances”), soon publishing articles in “many of the leading journals and periodicals.” She wrote a number of songs published in the United States and England under the name Seranus, and published other songs in England under the name, Gilbert King. She was the music critic of The Week from December 1886 to June 1887 under her pen-name of Seranus. She wrote the “Historical sketch on Canadian music” for the 1898 Canada: An Encyclopedia of the Country. Susan Harrison was considered an authority on folk music, and often lectured on the subject. She used traditional Irish melodies in her String Quartet on Ancient Irish Airs, and French-Canadian music in her 1887 Trois Esquisses canadiennes (Three Canadian Sketches), ‘Dialogue,’ ‘Nocturne,’ and 'Chant du voyageur’. She also incorporated French-Canadian melodies in her three-act opera, Pipandor (with libretto by F.A. Dixon of Ottawa). Her String Quartet on Ancient Irish Airs, is likely the first string quartet composed in Canada by a woman. In 1896 and 1897 she presented a series of well-received lectures in Toronto on "The Music of French Canada. For 20 years Harrison was the principal of the Rosedale branch of the Toronto Conservatory of Music. During the 1900s she contributed to and edited the Conservatory’s publication Conservatory Monthly, and contributed to its successor Conservatory Quarterly Review. She wrote the article on “Canada” for the 1909 Imperial History and Encyclopedia of Music. In addition, she wrote at least six books of poetry, and three novels. Writing Poetry Harrison’s musical training is reflected in her poetry: “she was adept in her handling of the rhythmic complexities of poetic forms such as the sonnet and the villanelle. Like other Canadian poets of the late nineteenth century, her prevailing themes include nature, love, and patriotism. Her landscape poetry, richly influenced by the works of Charles G.D. Roberts and Archibald Lampman, paints the Canadian wilderness as beguilingly beautiful yet at the same time mysterious and distant.” Harrison was a master of the villanelle. The villanelle was a French verse form that had been introduced to English readers by Edmund Gosse in his 1877 essay, “A Plea for Certain Exotic Forms of Verse”. Novels Her two novels “articulate a fascination with a heavily mythologized Quebec culture that Harrison shared with many English-speaking Canadians of her time... characterized by a gothic emphasis on horror, madness, aristocratic seigneurial manor houses, and a decadent Catholicism.” “Harrison writes elegiacally of a regime whose romantic qualities are largely the creation of an Upper Canadian quest for a distinctive historical identity.” Recognition Harrison experienced a decline in reputation in her lifetime. In 1916 anthologist John Garvin called her “one of our greater poets whose work has not yet had the recognition in Canada it merits.”. "By 1926, Garvin describes her merely as 'one of our distinctive poets’.” The Dictionary of Literary Biography wrote of Susan Frances Harrison, in 1990, that “Harrison’s unpublished work has not been preserved, her published work is out of print and difficult to obtain, and her once-substantial position in the literary life of her country is now all but forgotten.” Publications Selected songs * Song of Welcome. * Pipandor. opera * ‘Trois Esquisses canadiennes: ’Dialogue,' ‘Nocturne,’ 'Chant du voyageur’. 1887. * Quartet on Ancient Irish Airs. Poetry * Four Ballads and a Play. Toronto: Author, 1890. * Pine, Rose and Fleur De Lis. Toronto: Hart, 1891. * In Northern Skies and Other Poems. Toronto: Author, 1912. * Songs of Love and Labor. Toronto: Author, 1925. * Later Poems and New Villanelles. Toronto: Ryerson, 1928. * Penelope and Other Poems. Toronto: Author, 1934. * Bibliographical information on poems from Wanda Campbell, Hidden Rooms. Prose * Crowded Out and Other Sketches. Ottawa: Evening Journal, 1886. * The Forest of Bourg-Marie, novel. Toronto: G.N. Morang, 1898. * Ringfield, novel. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1914. Edited * Canadian Birthday Book. Toronto: Robinson, 1887. Poetry anthology. Articles * “Historical sketch of music in Canada,” Canada: An Encyclopedia of the Country, vol 4, J.C. Hopkins ed., Toronto, 1898. * “Canada,” The Imperial History and Encyclopedia of Music, vol 3: History of Foreign Music, W.L. Hubbard ed., New York ca 1909. Discography * Harrison’s piano music has been recorded and issued on media, including: * Keillor, Elaine. By a Canadian Lady Piano Music 1841-1997 Carleton Sound * Keillor, Elaine. Piano Music by Torontonians (1984) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Susie_Frances_Harrison

I was born in 1997, I've had a weird life, being forced to grow up fast, going through situations that will be described in some of my poems. I'm currently in high school dealing with what life throws at me. No matter what happens to me I try to deal life with a smile on my face, but my poetry is where I let everything flow out.

I have been an introverted writer/artist ever since I was a little girl no more than five years old living in a place where i felt i was not allowed to express myself. My imagination was my heaven, my domain, my escape, my serene place and my laboratory to brew the ideas in my soul. As I got older I started to do talent shows here and there, but I always perceived being critiqued as being judged and made fun of. As a result I did not consistently practice and follow through with striving to do my best work or constantly attempting to polish and refine my craft because I was filled with fear. I am no longer fearful. Feedback? Bring it on. Constructive criticism? I am ready for you. Namaste.

My name is Deborrah Ann Stenberg. I currently reside in Billings, Montana. I have been an adamant writer of children's stories and poetry throughout most of my life and I'm always honored to be involved with such dedicated achievers. Whether it's a hobby, profession, or a dream come true, we should never give up on what's important in life, and continue to practice all the things we do best. Then commend ourselves daily for rewarded success, and appreciate each noted achievement.

Born and raised in the Big Sky country, Billings, Montana. Hobbies and interests----photography, art, ceramics, poetry, and writing children's stories. Whether it's a hobby, profession, or a dream come true, never give on believing or dreaming. Always be proud of the person you are.

hello my name is tamika starks aka 4-play. I'm a 32 year old poet from buffalo New York , I've been writing since my mother died when I was 11. I've been doing the spoken word scene for the 7 years. I love poetry and it's pretty much the one thing I have control of all the time!!

A highly ambitious writer and entrepreneur always in search of new challenges. Edward has nearly two decades of experience working on Wall Street within the executive search business. He contributes to professional industry magazines and spends time blogging. Over the course of his writing career he has been published in EfinancialCareers, Bloomberg, Integrity Research, and Benzinga. Edward is from Springfield, IL and graduated from Arizona State University in 2003 where he studied Politcal Science and Creative Writing. He studied poetry under Norman Dubie and Alberto Rios. Today Edward manages a small consulting practice, hosts a podcast on Spotify called "The Poetry Everywhere" and writes poetry.

“Reading makes a full man.” – Francis Bacon Student with a greed for amassing enormous vocabulary, yet can’t speak them out. I am known for my avarice lust for words and poetry, I read whatever my hands grab. I like Yeats, Frost, Plath, Sexton and Dylan Thomas. Maybe Ted Hughes. Oh boy new words and poems, here I come!

This is a great platform to showcase ideas and desires to reflect thoughts and wishes. It is a means to express our deepest emotions, divulging inner feelings and illuminating the magic through poetry. Literature allows us to indulge in communication and exchangeability to enlighten our fellow poets and encourage the growth of written art. Sharing experiences, receiving likes and comments doesn't only make one feel heard, but it opens a gateway to a whole new dimension of commonality and understanding. The power of networking, empathising and encouraging others are active on this site, that's why I created this page.

writing something is expressing yourself, i feel i need to write when i am stressed or happy. i started writing when i was in alimentary school. there was a poem competition and i got a first prize for a poem "my loving mother". At that time i was innocent and never realised what exactly the world is, now i feel what i wrote that time was just expression of myself.

Hey, it's Khushi here, and this is my new blog "she writes". Writing endlessly, and scribbling away in journals has always been a part of my daily routine. Imagination and chai are the two things I thrive upon, and turning my musings into a blog has been on my list foreverr. So, join me on a journey through the labyrinth of language, where every verse is a portal to worlds unknown, where I'll write about relatable melancholic musings and some interesting?? Well you'll see!

Hey I was away for awhile traveling finding my inner self, but I am back so message me or Facebook me if you have question or just need a a really good friend to listen cause I'm that guy. :) updated 6/24/15 I am very initiative guy who has a lot if emotions to expose and I really want to get my words out there to help anybody in need and just remember your smile brings more smiles but when your sad you makes everybody else sad if anybody needs serious help help please contact me cause I will listen and to my honest beat to help you cause if I share my love you will to so smile :)

Hello my name is jasmine smith and i am a christian poet. for many years i have been writing poetry which was a therapy for my healing as a teenager. i endured so many changes and tragedies that the git of writing was my god given gift to share his love and his teachings. i am a southern girl from GEORGIA a small town called Dublin, Ga. i hope and pray that the things i write and speak are touching to you and brings you some type of positive vibe..