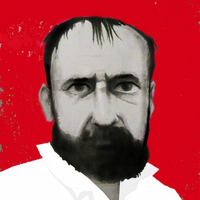

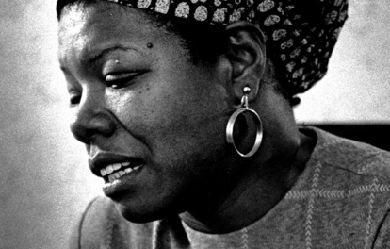

Maya Angelou (born Marguerite Ann Johnson; April 4, 1928 – May 28, 2014) was an American author and poet. She published seven autobiographies, three books of essays, and several books of poetry, and is credited with a list of plays, movies, and television shows spanning more than fifty years. She received dozens of awards and over thirty honorary doctoral degrees. Angelou is best known for her series of seven autobiographies, which focus on her childhood and early adult experiences. The first, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings (1969), tells of her life up to the age of seventeen, and brought her international recognition and acclaim. Angelou's long list of occupations has included pimp, prostitute, night-club dancer and performer, cast-member of the musical Porgy and Bess, coordinator for Martin Luther King, Jr.'s Southern Christian Leadership Conference, author, journalist in Egypt and Ghana during the days of decolonization, and actor, writer, director, and producer of plays, movies, and public television programs.

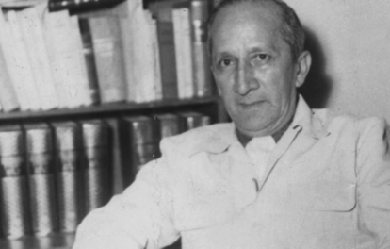

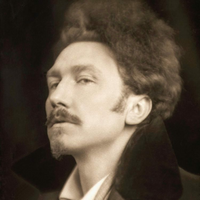

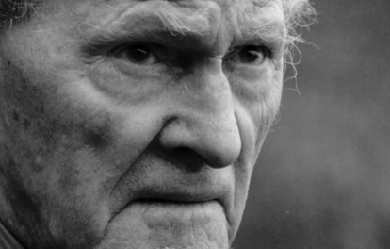

Ezra Weston Loomis Pound (30 October 1885 – 1 November 1972) was an American expatriate poet, critic and a major figure of the early modernist movement. His contribution to poetry began with his promotion of Imagism, a movement that derived its technique from classical Chinese and Japanese poetry, stressing clarity, precision and economy of language. His best-known works include Ripostes (1912), Hugh Selwyn Mauberley (1920), and his unfinished 120-section epic, The Cantos (1917–1969). Working in London in the early 20th century as foreign editor of several American literary magazines, Pound helped to discover and shape the work of contemporaries such as T. S. Eliot, James Joyce, Robert Frost, and Ernest Hemingway. He was responsible for the publication in 1915 of Eliot's “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” and for the serialization from 1918 of Joyce's Ulysses. Hemingway wrote of him in 1925: “He defends [his friends] when they are attacked, he gets them into magazines and out of jail. ... He writes articles about them. He introduces them to wealthy women. He gets publishers to take their books. He sits up all night with them when they claim to be dying... he advances them hospital expenses and dissuades them from suicide.”

Rafael Pombo, (Bogotá, República de Nueva Granada, 7 de noviembre de 1833 – Bogotá, Colombia, 5 de mayo de 1924), fue un poeta, escritor, fabulista, traductor, intelectual y diplomático colombiano. Sus padres fueron Lino de Pombo O'Donnell y Ana María Rebolledo, ambos pertenecientes a familias de la aristocracia de Popayán. Cuando el General Francisco de Paula Santander designó a Lino de Pombo como secretario del Interior y de Relaciones Exteriores, éste aceptó y viajó desde Popayán con su familia a Bogotá. Cuando la familia llegó a Bogotá, Ana María Rebolledo tenía 9 meses de embarazo, por lo que poco después dio a luz a su primogénito José Rafael de Pombo Rebolledo.

Idea Vilariño (Montevideo, 18 de agosto de 1920 - 28 de abril de 2009) poeta, ensayista y crítica literaria uruguaya perteneciente al grupo de escritores denominado Generación del 45. Dentro de sus facetas menos conocidas se encuentran la de traductora, compositora y docente. Nació en una familia de clase media y culta, en la que estaban presentes música y literatura. Su padre, Leandro Vilariño (1892-1944) fue un poeta conocido. Al igual que sus hermanos Numen, Poema, Azul y Alma, estudió música. Su madre conocía muy bien la literatura europea.

Edward Estlin Cummings (October 14, 1894 – September 3, 1962), popularly known as E. E. Cummings, with the abbreviated form of his name often written by others in lowercase letters as e.e. cummings (in the style of some of his poems—see name and capitalization, below), was an American poet, painter, essayist, author, and playwright. His body of work encompasses approximately 2,900 poems, two autobiographical novels, four plays and several essays, as well as numerous drawings and paintings. He is remembered as a preeminent voice of 20th century poetry.

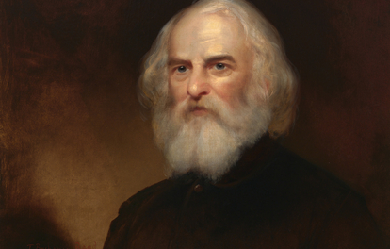

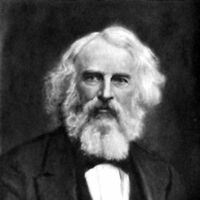

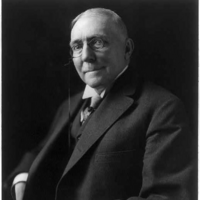

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (February 27, 1807 – March 24, 1882) was an American poet and educator whose works include "Paul Revere's Ride", The Song of Hiawatha, and Evangeline. He was also the first American to translate Dante Alighieri's The Divine Comedy and was one of the five Fireside Poets. Longfellow was born in Portland, Maine, then part of Massachusetts, and studied at Bowdoin College. After spending time in Europe he became a professor at Bowdoin and, later, at Harvard College. His first major poetry collections were Voices of the Night (1839) and Ballads and Other Poems (1841). Longfellow retired from teaching in 1854 to focus on his writing, living the remainder of his life in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in a former headquarters of George Washington. His first wife, Mary Potter, died in 1835 after a miscarriage. His second wife, Frances Appleton, died in 1861 after sustaining burns from her dress catching fire. After her death, Longfellow had difficulty writing poetry for a time and focused on his translation. He died in 1882.

Rosario Castellanos Figueroa (Ciudad de México, 25 de mayo de 1925 - Tel Aviv, 7 de agosto de 1974) fue una escritora, periodista y diplomática mexicana, considerada una de las literatas mexicanas más importantes del siglo XX. ...si es necesaria una definición para el papel de identidad, apunte que soy una mujer de buenas intenciones y que he pavimentado un camino directo y fácil al infierno. –Rosario Castellanos

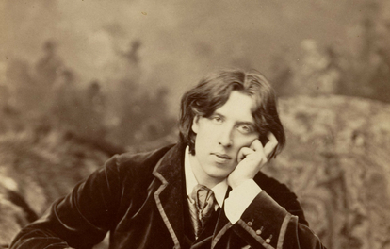

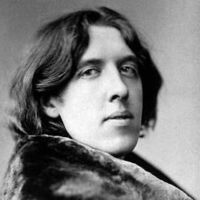

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 1854 – 30 November 1900) was an Irish writer and poet. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of London's most popular playwrights in the early 1890s. Today he is remembered for his epigrams, plays and the circumstances of his imprisonment, followed by his early death. At the turn of the 1890s, he refined his ideas about the supremacy of art in a series of dialogues and essays, and incorporated themes of decadence, duplicity, and beauty into his only novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890). The opportunity to construct aesthetic details precisely, and combine them with larger social themes, drew Wilde to write drama. He wrote Salome (1891) in French in Paris but it was refused a licence. Unperturbed, Wilde produced four society comedies in the early 1890s, which made him one of the most successful playwrights of late Victorian London.

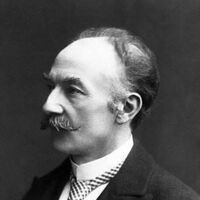

Thomas Hardy (2 June 1840 – 11 January 1928) was an English novelist and poet. While his works typically belong to the Naturalism movement, several poems display elements of the previous Romantic and Enlightenment periods of literature, such as his fascination with the supernatural. While he regarded himself primarily as a poet who composed novels mainly for financial gain, he became and continues to be widely regarded for his novels, such as Tess of the d'Urbervilles and Far from the Madding Crowd. Hardy's poetry, first published in his fifties, has come to be as well regarded as his novels and has had a significant influence over modern English poetry, especially after The Movement poets of the 1950s and 1960s cited Hardy as a major figure.

Juana Inés de Asbaje y Ramírez de Santillana, más conocida como Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, (San Miguel Nepantla, 12 de noviembre de 1651—Ciudad de México, 17 de abril de 1695) fue una religiosa y escritora novohispana del Barroco en el Siglo de Oro. Cultivó la lírica, el auto sacramental y el teatro, así como la prosa. Por la importancia de su obra, recibió los sobrenombres de «el fénix de América», «la Décima Musa» o «la Décima Musa mexicana». A muy temprana edad aprendió a leer y a escribir. Perteneció a la corte de Antonio de Toledo y Salazar, marqués de Mancera y 25° virrey novohispano. En 1667 ingresó a la vida religiosa a fin de consagrarse por completo a la literatura. Sus más importantes mecenas fueron los marqueses de la Laguna, virreyes de la Nueva España, quienes publicaron sus obras en la España peninsular. Murió a causa de una epidemia el 17 de abril de 1695.

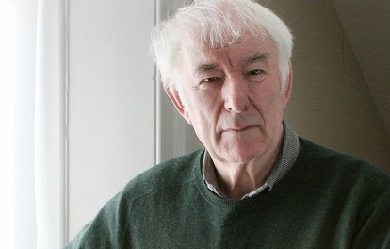

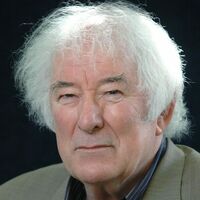

Seamus Justin Heaney (13 April 1939 – 30 August 2013) was an Irish poet, playwright and translator. He received the 1995 Nobel Prize in Literature. Among his best-known works is Death of a Naturalist (1966), his first major published volume. Heaney was and is still recognised as one of the principal contributors to poetry in Ireland during his lifetime. American poet Robert Lowell described him as “the most important Irish poet since Yeats”, and many others, including the academic John Sutherland, have said that he was “the greatest poet of our age”. Robert Pinsky has stated that “with his wonderful gift of eye and ear Heaney has the gift of the story-teller.” Upon his death in 2013, The Independent described him as “probably the best-known poet in the world”.

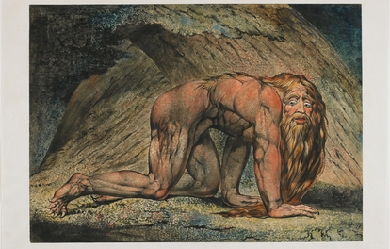

William Blake (28 November 1757 – 12 August 1827) was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his lifetime, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of both the poetry and visual arts of the Romantic Age. His prophetic poetry has been said to form “what is in proportion to its merits the least read body of poetry in the English language”. His visual artistry has led one contemporary art critic to proclaim him “far and away the greatest artist Britain has ever produced”. Although he lived in London his entire life except for three years spent in Felpham he produced a diverse and symbolically rich corpus, which embraced the imagination as “the body of God”, or “Human existence itself”.

Gustavo Adolfo Domínguez Bastida (Sevilla, 17 de febrero de 1836 – Madrid, 22 de diciembre de 1870), más conocido como Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer, fue un poeta y narrador español, perteneciente al movimiento del Romanticismo, aunque escribió en una etapa literaria perteneciente al Realismo. Por ser un romántico tardío, ha sido asociado igualmente con el movimiento posromántico. Aunque, mientras vivió, fue moderadamente conocido, sólo comenzó a ganar verdadero prestigio cuando, tras su muerte, fueron publicadas muchas de sus obras. Nació en Sevilla el 17 de febrero de 1836, hijo del pintor José Domínguez Insausti, que firmaba sus cuadros con el apellido de sus antepasados como José Domínguez Bécquer. Sus más conocidos trabajos son sus Rimas y Leyendas. Los poemas e historias incluidos en esta colección son esenciales para el estudio de la Literatura hispana, siendo ampliamente reconocidos por su influencia posterior. Gustavo Adolfo por Mercedes de Velilla En la margen del Betis murmurante, donde expira, entre flores, la onda inquieta, en monumento digno del poeta, su hermosa estatua se alzará triunfante. El sol le ofrecerá nimbo radiante; sus perfumes, la rosa y la violeta; la aurora, el beso de su luz discreta; el crepúsculo, brisa refrescante. Traerá la noche espíritus y hadas, visiones de Leyendas peregrinas que poblarán las verdes enramadas. La alondra y las obscuras golondrinas cantarán, al lucir las alboradas, las Rimas inmortales y divinas.

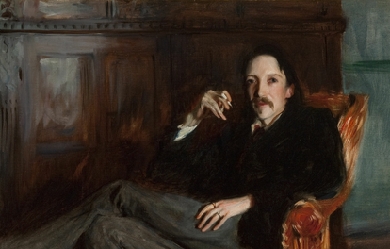

Robert Louis Balfour Stevenson (13 November 1850 – 3 December 1894) was a Scottish novelist, poet, essayist and travel writer. His best-known books include Treasure Island, Kidnapped, and Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. A literary celebrity during his lifetime, Stevenson now ranks among the 26 most translated authors in the world. He has been greatly admired by many authors, including Jorge Luis Borges, Ernest Hemingway, Rudyard Kipling, Marcel Schwob, Vladimir Nabokov, J. M. Barrie, and G. K. Chesterton, who said of him that he “seemed to pick the right word up on the point of his pen, like a man playing spillikins”.

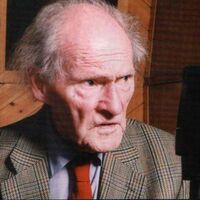

Ronald Stuart Thomas (29 March 1913 – 25 September 2000), published as R. S. Thomas, was a Welsh poet and Anglican priest who was noted for his nationalism, spirituality and deep dislike of the anglicisation of Wales. In 1955, John Betjeman, in his introduction to the first collection of Thomas’s poetry to be produced by a major publisher, Song at the Year's Turning, predicted that Thomas would be remembered long after Betjeman himself was forgotten. M. Wynn Thomas said: "He was the Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn of Wales because he was such a troubler of the Welsh conscience. He was one of the major English language and European poets of the 20th century." R. S. Thomas was born in Cardiff, the only child of Thomas Hubert and Margaret (née Davis). The family moved to Holyhead in 1918 because of his father's work in the merchant navy. He was awarded a bursary in 1932 to study at Bangor University, where he read Classics. In 1936, having completed his theological training at St. Michael's College, Llandaff, he was ordained as a priest in the Church in Wales. From 1936 to 1940 he was the curate of Chirk, Denbighshire, where he met his future wife, Mildred (Elsi) Eldridge, an English artist. He subsequently became curate at Tallarn Green, Flintshire. Thomas and Mildred were married in 1940 and remained together until her death in 1991. Their son, Gwydion, was born 29 August 1945. The Thomas family lived on a tiny income and lacked the comforts of modern life, largely by the Thomas's choice. One of the few household amenities the family ever owned, a vacuum cleaner, was rejected because Thomas decided it was too noisy. For twelve years, from 1942 to 1954, Thomas was rector at Manafon, near Welshpool in rural Montgomeryshire. It was during his time at Manafon that he first began to study Welsh and that he published his first three volumes of poetry, The Stones of the Field, An Acre of Land and The Minister. Thomas' poetry achieved a breakthrough with the publication of his fourth book Song at the Year's Turning, in effect a collected edition of his first three volumes, which was critically very well received and opened with Betjeman's famous introduction. His position was also helped by winning the Royal Society of Literature's Heinemann Award. Thomas learnt the Welsh language at age 30, too late in life, he said, to be able to write poetry in it. The 1960s saw him working in a predominantly Welsh speaking community and he later wrote two prose works in Welsh, Neb (English: Nobody), an ironic and revealing autobiography written in the third person, and Blwyddyn yn Llŷn (English: A Year in Llŷn). In 1964 he won the Queen's Gold Medal for Poetry. From 1967 to 1978 he was vicar at St Hywyn's Church (built 1137) in Aberdaron at the western tip of the Llŷn Peninsula. Thomas retired from church ministry in 1978 and he and his wife relocated to Y Rhiw, in "a tiny, unheated cottage in one of the most beautiful parts of Wales, where, however, the temperature sometimes dipped below freezing", according to Theodore Dalrymple. Free from the constraints of the church he was able to become more political and active in the campaigns that were important to him. He became a fierce advocate of Welsh nationalism, although he never supported Plaid Cymru because he believed they did not go far enough in their opposition to England. In 1996 Thomas was nominated for the Nobel Prize for Literature (the winner that year was Seamus Heaney). Thomas died on 25 September 2000, aged 87, at his home at Pentrefelin near Criccieth. He had been ill with heart trouble and had been treated at Gwynnedd hospital until two weeks before he died. After his death an event celebrating his life and poetry was held in Westminster Abbey with readings from Heaney, Andrew Motion, Gillian Clarke and John Burnside. Thomas's ashes are buried close to the door of St. John's Church, Porthmadog, Gwynedd. Beliefs Thomas believed in what he called "the true Wales of my imagination", a Welsh-speaking, aboriginal community that was in tune with the natural world. He viewed western (specifically English) materialism and greed, represented in the poetry by his mythical "Machine", as the destroyers of community. He could tolerate neither the English who bought up Wales and, in his view, stripped it of its wild and essential nature, nor the Welsh whom he saw as all too eager to kowtow to English money and influence. This may help explain why Thomas was an ardent supporter of CND and described himself as a pacifist but also why he supported the Meibion Glyndŵr fire-bombings of English-owned holiday cottages in rural Wales. On this subject he said in 1998, "what is one death against the death of the whole Welsh nation?" He was also active in wildlife preservation and worked with the RSPB and Welsh volunteer organisations for the preservation of the Red Kite. He resigned his RSPB membership over their plans to introduce non-native kites to Wales. Thomas's son, Gwydion, a resident of Thailand, recalls his father's sermons, in which he would "drone on" to absurd lengths about the evil of refrigerators, washing machines, televisions and other modern devices. Thomas preached that they were all part of the temptation of scrambling after gadgets rather than attending to more spiritual needs. "It was the Machine, you see", Gwydion Thomas explained to a biographer. "This to a congregation that didn’t have any of these things and were longing for them." Although he may have taken some ideas to extreme lengths, Theodore Dalrymple wrote, Thomas "was raising a deep and unanswered question: What is life for? Is it simply to consume more and more, and divert ourselves with ever more elaborate entertainments and gadgetry? What will this do to our souls?" Although he was a cleric, he was not always charitable and was known for being awkward and taciturn. Some critics have interpreted photographs of him as indicating he was "formidable, bad-tempered, and apparently humorless." Works Almost all of Thomas's work concerns the Welsh landscape and the Welsh people, themes with both political and spiritual subtext. His views on the position of the Welsh people, as a conquered people are never far below the surface. As a cleric, his religious views are also present in his works. His earlier works focus on the personal stories of his parishioners, the farm labourers and working men and their wives, challenging the cosy view of the traditional pastoral poem with harsh and vivid descriptions of rural lives. The beauty of the landscape, although ever-present, is never suggested as a compensation for the low pay or monotonous conditions of farm work. This direct view of "country life" comes as a challenge to many English writers writing on similar subjects and challenging the more pastoral works of such as contemporary poets as Dylan Thomas. Thomas's later works were of a more metaphysical nature, more experimental in their style and focusing more overtly on his spirituality. Laboratories of the Spirit (1975) gives, in its title, a hint at this development and also reveals Thomas's increasing experiments with scientific metaphor. He described this shift as an investigation into the "adult geometry of the mind".} Fearing that poetry was becoming a dying art, inaccessible to those who most needed it, "he attempted to make spiritually minded poems relevant within, and relevant to, a science-minded, post-industrial world", to represent that world both in form and in content even as he rejected its machinations. Despite his nationalism Thomas could be hard on his fellow countrymen. Often his works read as more of a criticism of Welshness than a celebration. He himself said there is a "lack of love for human beings" in his poetry. Other critics have not been so harsh. Al Alvarez said: "He was wonderful, very pure, very bitter but the bitterness was beautifully and very sparely rendered. He was completely authoritative, a very, very fine poet, completely off on his own, out of the loop but a real individual. It's not about being a major or minor poet. It's about getting a work absolutely right by your own standards and he did that wonderfully well." Thomas's final works commonly sold 20,000 copies in Britain alone. Books * The Stones of the Field (1946) * An Acre of Land (1952) * The Minister (1953) * Song at the Year's Turning (1955) * Poetry for Supper (1958) * Tares, [Corn-weed] (1961) * The Bread of Truth (1963) * Words and the Poet (1964, lecture) * Pietà (1966) * Not That He Brought Flowers (1968) * H'm (1972) * What is a Welshman? (1974) * Laboratories of the Spirit (1975) * Abercuawg (1976, lecture) * The Way of It (1977) * Frequencies (1978) * Between Here and Now (1981) * Ingrowing Thoughts (1985) * Neb (1985) in Welsh, autobiography, written in the third person * Experimenting with an Amen (1986) * Welsh Airs (1987) * The Echoes Return Slow (1988) * Counterpoint (1990) * Blwyddyn yn Llŷn (1990) in Welsh * Pe Medrwn Yr Iaith : ac ysgrifau eraill ed. Tony Brown & Bedwyr L. Jones, essays in Welsh (1990) * Mass for Hard Times (1992) * No Truce with the Furies (1995) * Autobiographies (1997, collection of prose writings) * Residues (2002, posthumously) References Wikipedia - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/R._S._Thomas

Carilda Oliver Labra. Poetisa cubana, Premio Nacional de Literatura (1998), nacida el 6 de julio de 1922 en la occidental provincia de Matanzas, específicamente en la capital provincial, ciudad en la que siempre ha vivido. Graduada de Derecho en la Universidad de La Habana en 1945, profesión que ha ejercido en su ciudad natal junto a su pasión por la poesía. Carilda Oliver: “He sido muy feliz siendo poeta” En el programa "Con 2 que se quieran”, 4 enero 2011. Amaury Pérez: Muy buenas noches, estamos en Con 2 que se quieran, ahora aquí en 5ta. Avenida y calle 32, en el barrio de Miramar, en los maravillosos Estudios Abdala. Una noche verdaderamente especial. Durante todos estos programas que han transcurrido hasta este momento, ustedes la pidieron, ustedes la solicitaron mediante sus correos, mediante sus cartas. Es la persona que más han solicitado. Yo lo he ido apuntando y así es y aquí está. Los ojos más bellos de la literatura cubana: una mujer extraordinariamente hermosa, una escritora de excelencia. Para cualquiera es emotivo presentarla, tenerla delante. Una mujer que irradia dulzura y ternura, la eminente poetisa cubana, matancera Carilda Oliver Labra. Señora, un beso, otro beso. Muchas gracias, yo estoy abrumado por su presencia, usted ha venido de Matanzas a estar aquí con nosotros y yo no puedo menos que rendirme a sus pies y agradecérselo. Y empezaremos nuestra conversación, más que una entrevista. Usted es Premio Nacional de Literatura. La pregunta sería. ¿Llegó a tiempo el Premio Nacional de Literatura? Carilda. Claro que te voy contestar y te voy a tratar de tú. Aunque no hemos tenido mucha oportunidad de vernos personalmente, pero te he visto en escena, en televisión, y en sueños… Amaury. Ay, Dios mío… Carilda. Primero, tengo que agradecerte la invitación. Amaury. Gracias, muchas gracias. Carilda. Después, todas esas cosas lindísimas que has dicho y en el transcurso del programa creo que se podrá ir haciendo presente esa admiración que es mutua. Amaury. Ah, muchas gracias. Carilda. Y que hoy para que no parezca esto una asociación de bombos recíprocos no te puedo hablar de tu música ni de tus interpretaciones. Yo creo que tú eres un poeta, lo de músico, ¡figúrate!, pero bueno, vamos a pasar a responder tu pregunta. Que si llegó, si tomó mucho tiempo… eso, en cierto modo, pues no es descorazonador, diríamos, no, no me angustió. Fui candidata 9 veces, o sea, 9 años seguidos, al Premio Nacional de Literatura que es, como todo el mundo sabe, el premio más importante en la carrera de un escritor. Fueron escogiendo los mejores escritores de Cuba, no puedo decir otra cosa, pero bueno, mi turno no llegaba y yo pensaba: bueno, es que yo no soy tan buena, yo no soy tan buena. Además, yo había tenido mis problemas, había estado fuera de las editoriales mucho tiempo, y decía: esto puede ser que influencie, era un tribunal, parece que compasivo, digo yo, también, a lo mejor no era tan justo, pero dirían: esta pobre mujer lleva 9 años esperando seguramente. No, yo ya no esperaba. Amaury. ¿No esperaba nada? Carilda. Cuando me lo dieron, que me llamaron por teléfono para decírmelo. Dije: Esto es una broma, esto es una broma. ¡Pero era verdad! Amaury. ¡Pero era verdad!, ¿y lo disfrutó? Carilda. ¡Ay, cómo no! Lo disfruté muchísimo, lo estoy disfrutando todavía. Sí, sí, porque eso, claro, es un compromiso, es un compromiso histórico y algo que nos obliga a tratar de ser mejores y ya va siendo imposible porque la vida…, con sus añitos… es posible que nos esté haciendo daño. Desde luego, nosotros no nos damos cuenta. Esto es una coquetería, esto es una coquetería. Amaury. Téngala conmigo porque la está teniendo con los televidentes nada más. La veo que mira para la cámara y para la cámara, tiene que hablarme a mí, porque me estoy poniendo celoso. Carilda. Yo coqueteo con los televidentes… (risas) Amaury. (risas) Yo estoy celoso, me estoy poniendo celoso de la cámara. Carilda. No esté celoso, porque más celoso estará mi marido. (risas) Amaury. Ah, sí, seguramente. (risas) Carilda. Y ten cuidado no se cele de ti porque es karateca. (risas) Amaury. ¡No. no, no! Además él sabe que usted es un amor antiguo mío, pero somos amigos, usted lo sabe, Raydel y yo somos amigos, así que no se va a poner celoso conmigo. Ahora, ¿Usted escogió el camino de la poesía, Carilda, o la poesía la escogió a usted? Carilda. Bueno, yo creo que sería presumir mucho por parte mía si digo que yo fui escogida por la poesía. Es presumir mucho. Lo que pasa que de ella no me he podido escapar. He sido muy feliz siendo poeta. No hubiera querido ser nada más. Amo mucho la música, la plástica. He intentado y hasta me he graduado de pintura, pero realmente… el ballet, bueno, el teatro, todas las artes, pero, sinceramente, nací poeta. Y quiero decirlo, porque cuando yo tenía tres o cuatro años, que mi mamá me cantaba canciones, ella me contó mucho tiempo después, que yo le modificaba las canciones. Amaury. ¿Ah, sí? Carilda. La letra. Amaury. La letra, claro. Carilda. Entonces ella dijo: esta niña va a ser poeta y parece que resultó. Claro, la poesía es muy difícil y me parece a mí, que aparte del don que se pueda traer, hay que estudiar y tiene mucho que ver con la técnica y con la inspiración. Amaury. Ahí vamos, porque hay gente que dice que no hace falta… que la inspiración no existe. Carilda. ¡Pero imagínate!, si no existiera la inspiración, si fuera una cosa de aprender lo que es un endecasílabo, lo que es una cesura, lo que es un hemistiquio, lo que es un soneto, lo que es un verso libre, pues sería, vaya, un objetivo de cualquier persona. Amaury. Cualquier persona se aprende la técnica y ya es poeta. Carilda. Claro y yo creo que…, claro, se pueden hacer versos, pero una cosa es un verso y otra cosa es la poesía, ¿eh?. El verso es la línea, el fondo, la forma, diría, la forma. Pero tú puedes aprender…, bueno, vamos a hacer octosílabos. Me voy a leer a Martí, que era magnífico poeta y que además en los octosílabos, sí, era un príncipe y ya, voy cogiendo esa música, que la rima y el ritmo, pero si se te fue la chispa, que es el fuego, es más que el fuego, la luz del verso, no puedes hacer poesía. Bueno, no es una lección, es una idea muy humilde. Amaury. Bueno, es humilde pero está viniendo de Carilda Oliver. No me lo está diciendo cualquiera. Carilda. Además, no creo que sea una idea mía, yo creo que todos los que escribimos sabemos. Hay veces que uno hace cosas que rompen. Que las miras después y en todo…, uno puede escribir un poema breve de cinco o seis o siete versos y tener un solo verso, y si merece la pena lo dejamos porque es imposible que, por ejemplo, en un soneto, los catorce versos sean buenos. Ahora, me preguntaba Gabriela Mistral. ¡Ay, bueno, es una anécdota…! Perdóname que te la haga. Amaury. No, ¡pero qué bueno que me la hace! Por favor. Carilda. Bueno, el día que tuve la dicha de conocerla, porque fue tan generosa Dulce María Loynaz, nuestra enorme, inmensa, inolvidable Dulce María, que me invitó a su casa, la primera vez que fui, porque estaba allí Gabriela. Y entonces Gabriela, después que leyó unos sonetos míos, me dice: con una modestia, que es digna de mencionar. No por lo que entraña el elogio que me hizo, sino por la forma en que ella asumió el conocimiento de una muchacha, como ella llamaba “del campo”, una niña del campo, porque yo era matancera y Dulce María era capitalina y además una mujer que había viajado y yo no había salido de Tirry 81 (calle y número de la casa de Carilda en Matanzas). Amaury. De Calzada de Tirry 81. Carilda. Fue después que he viajado y he tenido otras oportunidades, pero bueno, Tirry 81, para mí, es el planeta. Entonces, ¿qué pasa?, que ella me dice: ¿Y cómo cierra tan bien los sonetos? porque en el último verso a mí siempre se me va la fuerza, palabra textuales de Gabriela, y luego paso mucho trabajo y a fin de cuentas lo dejo así, ¿pero cómo tú lo cierras tan bien? y entonces yo le dije: A mí, casi siempre, los sonetos me suceden en los momentos menos oportunos. Estoy sentada en el cine viendo una película, y me viene un solo verso y me levanto y voy para mi casa a escribir, porque después se me olvida. Es así, eso va en aumento, porque la inspiración es como que se consolida en determinado momento, ya es como una efervescencia, como una llama que crece, que crece y que luego no se vuelve humo, sino se vuelve luz. Y ese verso de la luz, a veces, aparece en el segundo terceto, en el último, o aparece en el primer cuarteto, en cualquier parte, pero uno tiene que darse cuenta y dice: este es el final y lo pone al final y después empieza la rima de abajo para arriba. Amaury. Nunca había oído que nadie empezara un soneto de abajo para arriba. Carilda. Sí, pero eso es una técnica, que yo no sé si yo la descubrí, yo creo que no, pero es un recurso, es un apoyo, y ahí está el soneto a mi madre. Búscalo. Amaury. ¡A claro, claro! Aquí, este soneto, por ejemplo. (Amaury le acerca el soneto Madre mía que estás en una carta, escrito por Carilda) Carilda. No lo vamos a leer todo completo. Amaury. ¡Léalo completo!. Carilda. Ah, ¿completo? Amaury. Completo. Carilda. Y entonces ustedes verán que el último verso, que no lo voy a decir ahora, es realmente el cierre, pero es que ese fue el primero que yo escribí y no lo puse arriba porque echaba a perder el soneto. Amaury. ¡Qué bárbaro! Carilda. ¿Comprende? él se llama: “Madre mía que estás en una carta”. Madre mía que estás en una carta Y en un regaño antiguo que no encuentro. Quédate para siempre aquí en el centro de la rosa total que no se aparta. Madre mía que estás tan lejos Harta de la nieve y la bruma, Espera que entro a ponerte a vivir con el sol dentro Madre mía que estás en una carta. Puedes darle al misterio alguna cita, Convenir con las sombras hechiceras. Puede ser una piedra que se quita O secarte ahora mismo las ojeras, pero acuérdate madre de tu hijita, ¡No te atrevas a todo, no te mueras! Amaury. ¡Madre santa, es que eso es un poema! ¿Cuán duro fue, ya que me leyó esto, el exilio de sus padres, para usted, que decidió quedarse? Carilda. Bueno, imagínate si fue duro el exilio, que yo los acompañé al aeropuerto y en el momento que el avión despegó, yo me quedé sin habla y sin oír. Y recuperé el habla a las pocas horas y todavía me falta por recuperar, que ya es imposible, de eso hace muchos años, el oído derecho. Yo oigo solo de este oído, del izquierdo, que lo recuperé después, de la impresión. Eso fue muy duro, pero la decisión la tomé sin dame cuenta. Desde que empezaron con el asunto de los pasaportes y tengo que significar que ninguno de los dos era desafecto a la Revolución. Pero se iban en pos de hijos y en pos de nietos. Amaury. Claro. Carilda. Mi papá era abogado y quería sacarme el pasaporte como para embullarme, pero sin decírmelo, siempre me respetaron mucho mi opinión, ni siquiera hicieron presión. Y, era muy triste, porque imagínese, ellos se iban…, aparte del amor, de la compañía, yo estaba en aquel momento sola, no tenía a nadie. Pero yo soy una palma que nací aquí y aquí tengo la raíz y no me podía, de ningún modo cortar las raíces, me quedé, eso fue todo. Amaury. Bueno, ya no sé ni cómo hacer las preguntas. La gente tiene una imagen, la imagen que se quiere crear de Carilda. Pero evidentemente hay una Carilda imaginada y hay una Carilda real. Hay una oculta, la que habita en Tirry 81, la que tiene una familia, la que tiene hace veinte años un compañero, un matrimonio, su esposo. Y hay una que es la que la gente quiere fantasear, que es la que acusan de… los términos son feos, pero la Carilda que dicen que es libertina (Carilda ríe), que cuando uno se pone a buscar los sinónimos de libertina… Y yo, yo puedo dar fe en televisión de que usted es una dama, de que usted es una señora. Carilda. Gracias, gracias. Bueno, eso es hasta simpático, no me ha traumatizado, aunque desde luego, en cierto modo ha tergiversado la personalidad literaria de uno. A mí no me afecta desde el punto de vista personal. A mí…, Carilda, es así, es asao… generalmente los artistas arrastramos una serie de comentarios, que son muy convenientes porque así hablan de nosotros, buscan las poesías, y se venden los libros y entonces uno puede hacer una carrera, pudiéramos decir, vamos a llamarle así a esto de ser poeta, que no es ninguna carrera. Ser poeta es una cosa muy difícil, cuando uno, bueno, quiere serlo de verdad. Entonces ¿qué pasa?, que yo, figúrate, muy jovencita escribí el tal “Me desordeno…” y la gente siguió desordenándose por su cuenta (risas), pero me han echado la culpa a mí de todo. La cantidad de hombres que me han dicho a mí y de mujeres: Ay, le agradezco su Me desordeno, porque con esa poesía yo he enamorado y he hecho, y qué sé yo. Y a mí me da risa, porque esa poesía es hasta inocente, es inocente incluso esa parte que dice: “Cuando quiero besarte arrodillada“, esa parte, la gente le da unas explicaciones… que bueno, no lo voy a decir aquí porque estamos en la televisión (risas), pero los televidentes ya saben de lo que estoy hablando. Entonces…, me van a tachar todo esto… (risas) Amaury. (risas) No le vamos a tachar nada. Carilda. ¿Qué dirá el ICRT? (risas) Amaury. No, no, nada, el ICRT es muy comprensivo con este programa. (risas) Carilda. Ay, perdónenme, pero yo, bueno, soy un poco irreverente, pero buena muchacha. (risas) Lo de muchacha es peor que lo de irreverente (risas). Amaury. (risas) ¡Señora, señora, señora! Carilda. Bueno, chico, pero me estoy divirtiendo un poco. (risas) Amaury. Claro que sí, diviértase. Carilda. En estos programas hay que reírse también. Amaury. Claro, no se puede ser tan grave… Carilda. A veces tenemos que llorar por cosas…, que tampoco debiéramos llorar… Amaury. No, pero si yo lo que la quiero es ver divertida. ¿Cómo llorando? No, yo no quiero verla llorando. Carilda. Estoy divertida, pero es culpa tuya, porque yo no sé qué vueltas me has dado, que mira dónde me has puesto (risas), porque yo no iba a venir a ningún programa. Bueno, entonces me atreví a celebrar las piernas de los hombres, de un hombre. Amaury. De uno, claro, no de los hombres. Carilda. En uno están todos los demás. Entonces la boca, los ojos, vaya, decirles piropos a los hombres. Porque siempre eran a las mujeres y bueno, pues yo rompí con eso, porque yo no veo nada en eso de extraordinario, ni de cosas subversivas, irreverentes, que estoy faltando el respeto, porque piensan que estoy hablando de una cosa carnal. Y el amor es espiritual y carnal y tiene que integrarse de las dos cosas, porque si no realmente no responde a la verdadera esencia del amor. Y bueno, todas esas cosas empezaron a traerme, aparte de algunas cosas de la vida de uno, que se han ido deformando y se han exagerado cosas y pasiones. Han inventado cosas con Hemingway, que no pasó nada en lo absoluto, ese era un hombre muy caballeroso, que me dio un elogio, un piropo delante de periodistas y eso empezó a dar vueltas, es un ejemplo que pongo. Y bueno, a cada rato pues a la gente le ha parecido muy natural que yo tenga romances de acuerdo con los versos que he escrito y esos versos están escritos para mis esposos, para las personas que yo he amado y que me han amado. Mi vida ¡figúrate!, en la Ciudad de Matanzas, que es una ciudad como todo el mundo sabe, como todas las provincias de Cuba. Yo allí salía sola con mi novio, cosa que la gente no hacía, mi familia me lo permitía. Estoy hablando de los años 50. Mi primer matrimonio data del 52. Íbamos a sentarnos en el parque…, allí lo más que hacíamos era cogernos las manos. El primer noviazgo mío eran dos días a la semana por la noche, dos horas, y mi mamá sentada cerca, que uno no se podía dar ni un beso porque, ¡imagínate!, ella, cuando ya el novio se iba, se paraba a la mitad del zaguán y ya. Esas cosas de la época…, que ahora los jóvenes disfrutan de otra libertad que ¡bienvenida sea!, porque creo que todo aquello era… Mi mamá era de una educación española. Mis abuelos eran españoles, por parte de madre, pero siempre mi madre, a pesar de haberse educado en aquel sitio, me respetaba, me veía como…, ella decía que no se podía interferir en la vida de los hijos hasta el extremo de querer dirigirlos en todo, que había que dejarles que respiraran el aire de la libertad, que ella no lo había tenido de niña, que siempre estaba con la religión a cuestas. Y, fíjate que todo eso no juega con que después yo escribiera determinados versos, pero a lo mejor era aquel hálito que había en mi casa de respeto lo que me hizo soltarme como un pájaro y volar. Amaury. Y no como un papalote donde hay una cuerda. Porque el papalote parece que está libre, pero hay una cuerda que lo ata. Carilda. Exacto, perfecta la imagen, perfecta la imagen. No sé si te contesté. Amaury. Sí, claro que me contestó. No, me contestó, y de más, qué maravilla. Carilda. Me he casado tres veces. Estuve muchos años sin compañía. Luego llegó un muchacho joven a mi vida, demasiado joven. Toda la ciudad se escandalizó y yo diría que toda Cuba, cuando él empezó a visitarme. Él estuvo como dos años detrás de mí y yo me acuerdo que el primer día que lo vi, lo vi a través de la mirilla de la puerta. Esto no viene al caso, pero bueno. (risas) Amaury. ¡No, cómo no!, sí viene al caso, claro, porque yo voy a leer ahora una cosa que él me mandó. Carilda. ¿Ah, sí? Amaury. Así que sí viene al caso, aquí todo viene al caso y, viniendo de usted, más al caso. Carilda. Bueno, pues entonces yo lo veía por la mirilla de la puerta. Él tenía el pelo largo -¡imagínese! que andaba por los veinte años y yo andaba por… vamos a no hablar de eso. Amaury. No lo diga, no lo diga. Carilda. Yo decía: Este es otro de esos muchachos que vienen a leer versos y a enamorarla a una, porque yo tenía una casa y vivía sola en la casa ¿comprende?, y sabe cómo son las cosas, como había tanta diferencia de edad, yo siempre pensaba… y eso es cosa de malicia también del pueblo. Amaury. Claro. Carilda. Que no nos perdonaron cuando empezamos el romance y cuando nos casamos. Siempre creyeron que él venía por la casa y porque ya yo tenía cierto nombre, y que él era un muchacho joven que empezaba. Pero yo me enamoré de aquel muchacho por muchas cosas. La primera porque la soledad es una cosa terrible, llevaba años viuda…, con mis gatos. Amaury. Con sus gatos, ¡qué maravilla! Carilda. Mis gatos que han sido mis nenés, mis niñitos, mis compañeros. Bueno, y ahí me conoció él, que yo no tenía ni un centavo y él tenía una casa magnífica donde vivir, había huido del campo porque quería estudiar y esa es la historia de ese joven. Amaury. Claro, él me manda hoy, porque no pudo venir al programa por asuntos personales vinculados con su mamá. Él me manda una carta que no voy a leer completamente porque es una carta privada, pero hay una parte que sí quiero compartir con Carilda, que no la conoce. Carilda. No. Amaury. Y con ustedes. Él me dice, bueno, empieza con “Mi muy admirado Amaury”, muy cariñoso. “Lamento profundamente no asistir a este encuentro con nuestra Carilda. Pero me ha resultado imposible” (y ahí me explica por qué). Pero después dice: “Gracias Amaury por llevarte contigo, en esta feliz ocasión, a una mujer que ya no se puede amar desde un solo cuerpo, que se ha hecho menos mía para volverse propiedad de un pueblo que ha encontrado en su voz la suya propia, prohijada por un deseo interminable de amor y de vida.” Y después me señala: “Hay muchas personas que tal vez contemplen nuestra pareja como un sacrilegio porque nos hemos atrevido a unir nuestras dos juventudes en un matrimonio que ya casi cumple dos decenios.” Y es lo que usted ahora ha estado aclarando y eso es lo que me manda a decir. Carilda. ¡Qué casualidad! Amaury. Ahora, él toca aquí un punto, fíjese que yo no lo tenía ni anotado… pero él toca un punto donde dice, hablando de usted y, ahora entonces vamos a hablar de este tema que él toca aquí. “Carilda ha tenido fe en la justicia, en el amor de su gente y en el triunfo de la verdad. Por ello en mi opinión creo que durante aquellos casi veinte años de silencio en su amada Patria, no supo en la soledad ser infeliz.” ¿Por qué usted cree que hubo tanto tiempo sin que a usted la consideraran lo que siempre ha sido? Una cubana fiel, digna y amante de su Patria. Carilda. Bueno, hay cosas que realmente ni el tiempo ha podido aclarar. Porque la verdad, sí, yo siempre creí que todo pasaría y así fue, todo pasó. Yo había escrito, inclusive, un Canto a Fidel cuando estaba en la Sierra (Maestra) porque yo había conocido a Fidel en la Universidad. Ya yo terminando en la Universidad, Derecho, él empezaba y, naturalmente, al ver que estaba en la Sierra -y esa historia no la voy a hacer porque es larga y ya se ha publicado- Me emocionó mucho aquel compañero de la adolescencia, que alentaba una Revolución que era una esperanza. Amaury. Un símbolo. Carilda. Y así, bueno, entonces ¿qué sucede? La Revolución realmente triunfó, pero inmediatamente, casi, a mí me dejaron cesante de mi trabajo. ¿Por qué? porque yo trabajaba en la Alcaldía de Matanzas. Porque las revoluciones son convulsas y cuando comienzan, como en este caso, hay un problema: Que hay mucha gente que se sube al carro de la Revolución sin haber estado en esa Revolución. Y a mí me parece que los intermediarios fueron, no en este caso, pero en muchos casos, fueron responsables de las injusticias y de las cosas que pasaron. Yo tuve la suerte de que no me quedé completamente cesante y esto es muy bueno decirlo, porque siempre hay alguien que esclarece, que salva, que es un abogado, que hoy es muy notable y es uno de los defensores de los Cinco Héroes, que es el doctor Rodolfo Dávalos. Amaury. Una eminencia, el doctor Dávalos es una eminencia. Carilda. Una eminencia, jurista y él me dijo: no, no importa, tú eres abogada y tú no has cometido delitos… Además, tú tienes ese Canto a Fidel. Él es poeta, pero de esos silenciosos, que no publican. Amaury. Sí, que no quiere publicar. Carilda. Tremendo escritor ¿eh?. Y entonces, bueno, entré en aquel bufete colectivo y fui muy feliz en ese bufete, porque allí se pudo hacer mucha justicia y muchas cosas y no se habló de nada. Pero el veto empezó a pesar de estar yo en el bufete. Amaury. ¿Y no se le publicaba entonces, nada? Carilda. Esto es bueno que se sepa, ¡qué me van a publicar! Pasaron muchas cosas. Amaury. ¿Y cuándo termina el veto? Carilda. Eso termina un día, un buen día, un magnífico día, estoy nombrando personas porque estoy hablando verdades. Amaury. Claro, claro. Carilda. No me gusta hacer anonimatos, y fulano, y que esto. Bueno y además, estoy muy agradecida al doctor Armando Hart. Amaury. Un hombre de la cultura y un hombre justiciero. Carilda. Se apareció en Matanzas un día, a averiguar qué pasaba conmigo, porque él no entendía nada. Amaury. Pero usted nunca abandonó ninguna Revolución ¿qué Revolución abandonó usted? Carilda. ¿Pero qué abandono?, ¡pero si no me exilé con toda mi familia y seguí en mi Tirry 81 pasando calamidades! Yo he comido sopas de yerbas y todas esas cosas. Yo tuve que arrancar las puertas grandes de Tirry 81, que están detrás de las ventanas, para un pobre guajiro que vino, bueno, no era pobre porque tenía más dinero que yo, y me compró las puertas y con eso comí como seis meses. ¡Ay, pero no soy ninguna víctima! Amaury. ¡Claro que no!. Carilda. No, no, no. Amaury. ¡Y con esos ojos!. Carilda. Muy dichosa. Muy dichosa, porque escribí más poesía que nunca. Escribe y escribe y escribe y feliz, feliz. Amaury. Bueno, aquí están sobre la mesa sus libros… Carilda trajo sus libros. Yo me he quedado frío. Carilda. Tengo 43 libros. Claro, entre ediciones, reediciones y cosas en el extranjero. En España tengo cinco libros. Amaury. Ahora, yo quiero de todas maneras, porque cuando hablamos por teléfono el otro día… Carilda. Sí. Amaury. …Hablamos mucho, hablamos más por teléfono que lo que vamos a hablar en la entrevista. Y pasó una cosa bien curiosa, porque yo le dije que a mí me encantaba este soneto, de Sonetos a mi padre, el cuarto soneto. Carilda. Ah, sí. Amaury. Y usted de pronto me dijo: qué casualidad, era el que le gustaba a ¡Eliseo Diego! Carilda. Sí, así mismo es. Amaury. Léame, por favor, ese soneto. Carilda. ¿El último? Amaury. Ese soneto, el último, yo se lo escogí. Carilda. Este es el Cuarto Soneto de la colección, pero cuatro son demasiado. Tu sillón de dentista ¿dónde está? Tu violín de estudiante, ¿cómo suena? Enterrabas centavos en la arena Y otros nombres ponías a mamá. Guardo todas tus cartas y retratos En mis sueños tu próstata se cura, Por el fondo del patio y la ternura Se encaminan tus últimos zapatos. Quiero verte salir en un postigo, ¡Ven fantasma, ven ángel oportuno! Ya no sé lo que hago, lo que digo, Porque quiero beber el desayuno, Con mi padre, mi sabio, mi mendigo En Calzada de Tirry 81. Amaury. ¡Es que es algo…, es precioso ese soneto! y se ve que a usted le afecta, todavía le afecta. No sé ni para qué lo traje. Fíjese qué rápido vamos a hablar de otro tema. A ver si usted me quiere decir este secreto. En este libro (Amaury le muestra un libro) hay una carta, están sus prosas, aparte que hay una foto aquí tremenda, la foto de la portada, con el pelo corto. Carilda. Está agotado ese libro. Amaury. Ese libro está agotado, ah, bueno. Pero ya uno va teniendo cosas que están agotadas, uno se va quedando con ellas. Pero hay un momento, donde hay varias cartas. Usted no quiere, ya me lo dijo por teléfono, hablar de a quién le había hecho las cartas y yo, por supuesto, respeto eso, pero no puedo privar al televidente de esa Carilda irónica que aparece aquí en un momento de esta carta. Carilda. ¡Ah!, va a leer esa, ¡vale!. Amaury. En un momento de esta carta yo por poquito me…, yo me arrastré cuando la leí la primera vez -carta número 4 se llama-, Te escribo por recomendación de este papel amarillo que vi sobre la mesa y para que me perdones el incumplimiento de la amenaza: El director tropieza con todos los sueños, así que dispuso sin mi permiso, que trabajara hoy de noche. Como te encantan las sorpresas, estarás muy contento de ver a otra mujer y no a la que pronosticó el telegrama. Pues bien, deseo con todos los humores negros de mi venganza, que solo caiga en tus brazos una soprano calva de 190 libras. No vamos a hablar de a quién se la hizo, pero vamos a hablar de esa Carilda maldita, esa Carilda, que vaya, es que no… “Lo que deseo es que caiga en tus brazos una soprano calva de 190 libras“. (risas) Carilda. (risas) Ay, son cosas de la juventud. Amaury. Ahora, ¿cómo fue aquello del tren que viene de Santiago, pasa por Matanzas y una persona que la amaba le ponía mensajes en el tren? ¿Qué cosa es eso, Carilda? Carilda. Ay, pero mira lo que estás sacando hoy. Óyeme, pero ¿cuántos cuentos te han hecho? Qué cosas… Amaury. Pero es que eso es tan bello. Carilda. Bueno, es verdad, es una cosa de…, y estoy hablando del año 50, porque fue el año, lo recuerdo perfectamente, en que salió Al sur de mi garganta. Al sur… nace en el 49, pero se lleva el Premio Nacional de Poesía del 50. Y entonces él es un poeta, por cierto, un poeta muy singular, porque es que tenía muchos oficios y era matemático, era graduado de La Sorbona, de Yale, yo no sé de cuántos lugares. Era un hombre muy talentoso que apareció en Cuba. Y como él quería enamorarse, porque él quería enamorarse de algún modo de alguna cubana, y sobre todo que fuera un amor imposible, digo yo, porque hizo todo lo posible. Yo tenía mi novio, yo era novia de Hugo Ania que era un noviazgo reciente y que después nos casamos. Y entonces, pues… No voy a contar lo que pasó en el medio, porque hubo problemas muy serios. Amaury. No, no. Carilda. Esa es la mitología con que el pueblo cubano me ha adornado a mí, porque ese mito es un adorno. Amaury. Claro. Carilda. La gente quiere que yo sea como me han inventado. Amaury. Exactamente. Carilda. Y realmente yo soy una señora muy respetable, ¡Ay!, ¿qué dije? (se tapa la boca) Amaury. No, sí lo es. Sí, Carilda, sí lo es. Carilda. No, pero es que todo el mundo se va a disgustar. Amaury. No, nadie se va a disgustar. Carilda. ¿Tú crees que no? Amaury. No, nadie se va a disgustar. La gente va a seguir con la mitología que quiera crearse sobre usted. Pero es bueno que de una vez se diga, que lo importante de usted, aparte de su belleza, aparte de su talento, de su simpatía, es su gran obra poética, que es lo que la va a trascender. Y la mitología que la gente se crea sobre los artistas, esa se va a quedar en el camino y lo que va a quedar al final, son estos poemas, son estos libros, eso es lo que va… Carilda. …Ay, Amaury. ¡Qué generoso eres! Amaury. No, generoso no, soy justo con usted. Carilda. Te quiero. Amaury. Carilda ¿Y entonces lo del tren? ¿El tren salía de dónde? Carilda. Él tren venía de Santiago y llegaba a La Habana, aquí, pero claro, pasaba por Matanzas. Y entonces, este escritor, uruguayo, me escribía, después que se fue de Matanzas, me escribía desde allá. Pero él quería que llegaran las cosas tan pronto que iba al último vagón del tren. Ya me lo había advertido por teléfono: por la mañana me decía: Carilda, ahora voy a escribirte un mensaje en la pared del vagón último del tren, bueno, yo iba por la noche cuando llegaba el tren a Matanzas a ver aquello, a leer aquello. ¡Qué lindas cosas escribía! Amaury. Por eso ahí empiezan las historias. Carilda. Y ahí empiezan las historias de Carilda ¿comprende? Amaury. Claro Carilda. Que después de todo son historias muy lindas y no hay por qué renunciar a ellas. Amaury. Pero mire, yo le voy a decir algo. El pueblo cubano, el lector cubano y más que el lector cubano, incluso, el que no la ha leído -que se está perdiendo una de las maravillas del mundo- la quiere a usted, usted es amada. Usted es amada por todo el mundo. Carilda. No, porque amo, porque amo al pueblo. Amaury. Claro, porque eso va y viene, eso es un efecto de ida y vuelta. Ahora, yo quiero, Carilda, porque ya el programa lo estamos terminando. Mire, usted me trajo hoy de regalo la última edición de Al sur de mi garganta, es esta. Carilda. 60 años cumplió el año pasado. Amaury. Con una dedicatoria que es para mi corazón, yo no voy a leer lo que dice, que es muy emocionante y ya yo tengo hace rato los ojos aguados. Pero es que yo traje para que Carilda me firmara… Carilda. …¡Ay, chico!… Amaury. …La edición Príncipe… Carilda. …Eso me emocionó… Amaury. …De Al sur de mi garganta... Carilda. Porque nadie la tiene, porque se hicieron 300 ejemplares. Imagínense, en el año 49. Amaury. Claro, del 49 y esto se lo regala a mi tío Raúl y por supuesto a mi tía María Luisa también, Pascualito, un amigo, el 11 de marzo de 1950. Y aquí está con las ilustraciones. ¿Cuántos libros se hicieron de esta edición? Carilda. 300 nada más. Esto lo pagó mi padre. Entonces no había editoriales. Amaury. ¡Fíjese que es propiedad del autor!. Carilda. Y tuve la suerte de que con ese librito gané el premio. Amaury. Entonces usted me va a hacer el favor de poner su nombre aquí. Y después, porque estamos en televisión, me pone una cosita más, porque eso es un tesoro de la biblioteca nuestra, de mi esposa y mía. Un programa bien emotivo y bien difícil. Esto no se puede creer. Carilda. Es que tú no habías nacido cuando el libro se publicó. Amaury. ¡Claro que no había nacido!. Carilda. Ah, imagínate. Amaury. Pero ya había nacido usted, había nacido su poesía y a lo mejor, quién sabe si yo nací de algún poema de estos. Entonces, ahora va a terminar el programa usted. Yo antes le voy a agradecer su gentileza, su viaje, el suyo y el de sus compañeros que la han traído. Ha sido un programa muy especial. Es además el programa con el que estamos comenzando este año 2011, es el primer programa de enero de 2011. Todavía hay una grata temperatura afuera, hemos acabado de pasar las Navidades…, yo quiero que usted me lea este poema que es uno de los poemas que más me gusta suyo, y que de esa manera despida el programa y le agradezco señora, su poesía, su talante, su genio, su gentileza, su belleza. Su amor a Cuba, su amor a la Patria. Carilda. Gracias, la agradecida soy yo. Gracias. Adiós locura de mis treinta años, Besado en julio bajo luna llena, Al tiempo de la herida y la azucena Adiós mi venda de taparme daños. Adiós mi excusa, mi desorden bello, mi alarma tierna, mi ignorante fruta Estrella transitoria que se enluta, Esperanza de todo por mi cuello. Adiós muchacho de la cita corta, Adiós pequeña ayuda de mi aorta, Tristísimo juguete violentado Adiós verde placer, falso delito Adiós sin una queja, sin un grito Adiós mi sueño nunca abandonado. Amaury. Gracias, Carilda, muchas gracias por existir. Nos veremos pronto. Carilda. Gracias. Petí arregla el vestido de la poeta y Solís verifica que el micrófono permita escuchar con nitidez la voz de Carilda. El programa está por comenzar. Referencias Cuba Debate - www.cubadebate.cu/noticias/2011/01/04/carilda-oliver-he-sido-muy-feliz-siendo-poeta/ BIOGRAFÍA Su primer libro, "Preludio Lírico", fue publicado en Matanzas en 1943. En esta selección de poemas escritos entre 1939 y 1942, ya se hacen presentes: -El amor, con sus devanes, inquietudes, zozobras, desalientos, aciertos, quizás con una pluma inexperta que no sabía dominar emociones e impregnada del entorno un tanto melodramático que a muchos atacaba; -La familia, la abuela, la madre y el padre presentes en un cuadro que no desaparecerá nunca de su obra. Después de obtener el Segundo Lugar en el Concurso Internacional de Poesía, organizado por la National Broadcasting Co. de Nueva York, Estados Unidos, publica en 1949 "Al sur de mi garganta", libro con el que ganó el Premio Nacional de Poesía, al mismo tiempo que trabaja en la biblioteca Gener y del Monte, es declarada Hija Eminente de la Atenas de Cuba. En esa misma temporada culmina sus estudios en la Escuela de Artes Plásticas de Matanzas que la acreditan como profesora de Dibujo, Pintura y Escultura y contrajo nupcias con el abogado y poeta Hugo Ania Mercier, de quien se divorciaría en 1955 tras una relación turbulenta. Tuvo otros 2 matrimonios: Félix Pons, cuya muerte la inspiró para su libro "Se me ha perdido un hombre" y finalmente Raidel Hernández, muy joven, con quien comparte ahora su vida. Se le reconoce una intensa labor como profesora en escuelas de su natal Matanzas, ligando a su amor por el magisterio su trabajo como abogada y su pasión por la poesía. Hasta la actualidad cuenta con 43 publicaciones que incluyen prosa y poesía, más varios premios y reconocimientos. Poemas suyos han sido traducidos al inglés, francés, italiano, ruso, búlgaro, rumano y vietnamita. Desde 1980 funciona en Madrid una Tertulia Poética que lleva su nombre y que, además, convoca anualmente a un Premio Internacional de Poesía. Aunque su obra transmite muchas veces dolor, añoranza o vacío, desde el "Me desordeno amor..." que hizo con tan solo 24 años, su poesía está cargada de sensualidad, desenfado, seducción, y la muestran progresista, liberal y hasta un tanto irreverente. En una ocasión comentó: "Tal vez me colgaron la etiqueta de erótica porque conocen más esa proyección mía que las otras. Es la que escogen los declamadores, la que aparece en programas radiales y aquella que se ha musicalizado y difundido casi sin yo darme cuenta." Ella misma nos da su receta de erotismo: “Hay que renunciar a traducir su misterio. Entre el erotismo y la profanación, entre lo que debe ser y lo que tiene que ser hay una línea divisoria muy fina. Nace, no se aprende”. Referencias Wikipedia - es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carilda_Oliver Cuba Literaria - www.cubaliteraria.cu/autor/carilda_oliver/biografia.html Ecured - www.ecured.cu/index.php/Carilda_Oliver_Labra

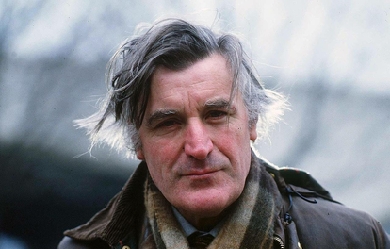

Edward James (Ted) Hughes was born in Mytholmroyd, in the West Riding district of Yorkshire, on August 17, 1930. His childhood was quiet and dominately rural. When he was seven years old, his family moved to the small town of Mexborough in South Yorkshire, and the landscape of the moors of that area informed his poetry throughout his life. Hughes graduated from Cambridge in 1954. A few years later, in 1956, he co-founded the literary magazine St. Botolph’s Review with a handful of other editors. At the launch party for the magazine, he met Sylvia Plath. A few short months later, on June 16, 1956, they were married.

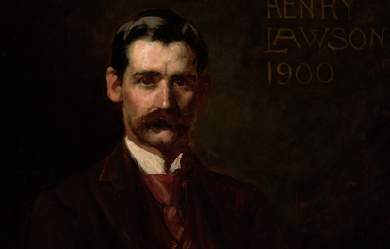

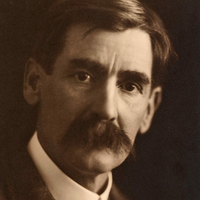

Henry Archibald Hertzberg Lawson (17 June 1867 – 2 September 1922) was an Australian writer and poet. Along with his contemporary Banjo Paterson, Lawson is among the best-known Australian poets and fiction writers of the colonial period and is often called Australia's “greatest short story writer”. He was the son of the poet, publisher and feminist Louisa Lawson.

Pedro Salinas Serrano (Madrid, 27 de noviembre de 1891 – Boston, 4 de diciembre de 1951) fue un escritor español conocido sobre todo por su poesía y ensayos. Dentro del contexto de la Generación del 27, se le considera uno de sus mayores poetas. Sus traducciones de Proust contribuyeron al conocimiento del novelista francés en el mundo hispanohablante. Al concluir la guerra civil española, se exilió en Estados Unidos hasta su muerte.

Eduardo Germán María Hughes Galeano (Montevideo, 3 de septiembre de 1940-Ib., 13 de abril de 2015) fue un periodista y escritor uruguayo, considerado uno de los escritores más influyentes de la izquierda latinoamericana. Sus libros más conocidos, Las venas abiertas de América Latina (1971) y Memoria del fuego (1986), han sido traducidos a veinte idiomas. Sus trabajos trascienden géneros ortodoxos y combinan documental, ficción, periodismo, análisis político e historia.

William Carlos Williams (September 17, 1883 – March 4, 1963) was an American poet closely associated with modernism and Imagism. He was also a pediatrician and general practitioner of medicine with a medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine. Williams "worked harder at being a writer than he did at being a physician" but excelled at both. Although his primary occupation was as a family doctor, Williams had a successful literary career as a poet. In addition to poetry (his main literary focus), he occasionally wrote short stories, plays, novels, essays, and translations. He practiced medicine by day and wrote at night. Early in his career, he briefly became involved in the Imagist movement through his friendships with Ezra Pound and H.D. (also known as Hilda Doolittle, another well-known poet whom he befriended while attending the University of Pennsylvania), but soon he began to develop opinions that differed from those of his poet/friends.

Emily Jane Brontë (30 July 1818 – 19 December 1848) was an English novelist and poet, best remembered for her solitary novel, Wuthering Heights, now considered a classic of English literature. Emily was the third eldest of the four surviving Brontë siblings, between the youngest Anne and her brother Branwell. She published under the pen name Ellis Bell. She was born in Thornton, near Bradford in Yorkshire, to Maria Branwell and Patrick Brontë. She was the younger sister of Charlotte Brontë and the fifth of six children. In 1824, the family moved to Haworth, where Emily's father was perpetual curate, and it was in these surroundings that their literary gifts flourished.

Dylan Marlais Thomas (27 October 1914 – 9 November 1953) was a Welsh poet and writer who wrote exclusively in English. In addition to poetry, he wrote short stories and scripts for film and radio, which he often performed himself. His public readings, particularly in America, won him great acclaim; his sonorous voice with a subtle Welsh lilt became almost as famous as his works. His best-known works include the “play for voices” Under Milk Wood and the celebrated villanelle for his dying father, “Do not go gentle into that good night”. Appreciative critics have also noted the craftsmanship and compression of poems such as “In my Craft or Sullen Art”, and the rhapsodic lyricism in “And death shall have no dominion” and “Fern Hill”.

Carolina Coronado Romero de Tejada (Almendralejo, Badajoz, 12 de diciembre de 1820 - Lisboa, 15 de enero de 1911, enterrada en el Cementerio de Badajoz), escritora española, considerada como la equivalente extremeña de otras autoras románticas coetáneas como Rosalía de Castro, y autora de tal notoriedad que llegaría a ser calificada con el título de "El Bécquer femenino". Fue tía de Ramón Gómez de la Serna. Nació en el seno de una familia acomodada de Almendralejo (Badajoz), pero de ideología progresista, lo que provocó que su padre y su abuelo fueran perseguidos. Tras mudarse a la capital de provincia, Badajoz, Carolina sería educada de la forma tradicional para las niñas de la época: costura, labores del hogar... pese a lo cual, ya desde pequeña mostró su interés por la literatura, y comienza a leer, robando horas al sueño, cualquier género u obra que puede conseguir.

Khalil Gibran (Arabic pronunciation: [xaˈliːl ʒiˈbrɑːn]) (January 6, 1883 - April 10, 1931); born Gubran Khalil Gubran, was a Lebanese-American artist, poet, and writer. Born in the town of Bsharri in modern-day Lebanon (then part of the Ottoman Mount Lebanon mutasarrifate), as a young man he emigrated with his family to the United States where he studied art and began his literary career. In the Arab world, Gibran is regarded as a literary and political rebel. His Romantic style was at the heart of a renaissance in modern Arabic literature, especially prose poetry, breaking away from the classical school. In Lebanon, he is still celebrated as a literary hero. He is chiefly known in the English-speaking world for his 1923 book The Prophet, an early example of inspirational fiction including a series of philosophical essays written in poetic English prose. The book sold well despite a cool critical reception, gaining popularity in the 1930s and again especially in the 1960s counterculture. Gibran is the third best-selling poet of all time, behind Shakespeare and Lao-Tzu. In academic contexts his name is often spelled Jubrān Khalīl Jubrān,:217:255 Jibrān Khalīl Jibrān,:217:559 or Jibrān Xalīl Jibrān;:189 Arabic جبران خليل جبران , January 6, 1883 – April 10, 1931) also known as Kahlil Gibran, In Lebanon Gibran was born to a Maronite Catholic family from the historical town of Bsharri in northern Lebanon. His mother Kamila, daughter of a priest, was thirty when he was born; his father Khalil was her third husband. As a result of his family's poverty, Gibran received no formal schooling during his youth. However, priests visited him regularly and taught him about the Bible, as well as the Arabic and Syriac languages. Gibran's father initially worked in an apothecary but, with gambling debts he was unable to pay, he went to work for a local Ottoman-appointed administrator. Around 1891, extensive complaints by angry subjects led to the administrator being removed and his staff being investigated. Gibran's father was imprisoned for embezzlement, and his family's property was confiscated by the authorities. Kamila Gibran decided to follow her brother to the United States. Although Gibran's father was released in 1894, Kamila remained resolved and left for New York on June 25, 1895, taking Khalil, his younger sisters Mariana and Sultana, and his elder half-brother Peter (in Arabic, Butrus). In the United States The Gibrans settled in Boston's South End, at the time the second largest Syrian/Lebanese-American community in the United States. Due to a mistake at school, he was registered as Kahlil Gibran. His mother began working as a seamstress peddler, selling lace and linens that she carried from door to door. Gibran started school on September 30, 1895. School officials placed him in a special class for immigrants to learn English. Gibran also enrolled in an art school at a nearby settlement house. Through his teachers there, he was introduced to the avant-garde Boston artist, photographer, and publisher Fred Holland Day, who encouraged and supported Gibran in his creative endeavors. A publisher used some of Gibran's drawings for book covers in 1898. Gibran's mother, along with his elder brother Peter, wanted him to absorb more of his own heritage rather than just the Western aesthetic culture he was attracted to, so at the age of fifteen, Gibran returned to his homeland to study at a Maronite-run preparatory school and higher-education institute in Beirut, called Al-Hikma (The Wisdom). He started a student literary magazine with a classmate and was elected "college poet". He stayed there for several years before returning to Boston in 1902, coming through Ellis Island (a second time) on May 10. Two weeks before he got back, his sister Sultana died of tuberculosis at the age of 14. The next year, Peter died of the same disease and his mother died of cancer. His sister Marianna supported Gibran and herself by working at a dressmaker’s shop. Art and poetry Gibran held his first art exhibition of his drawings in 1904 in Boston, at Day's studio. During this exhibition, Gibran met Mary Elizabeth Haskell, a respected headmistress ten years his senior. The two formed an important friendship that lasted the rest of Gibran’s life. Though publicly discreet, their correspondence reveals that the two were lovers. In fact, Gibran twice proposed to her but marriage was not possible in the face of her family's conservatism. Haskell influenced not only Gibran’s personal life, but also his career. She became his editor, and introduced him to Charlotte Teller, a journalist,and Emilie Michel (Micheline), a French teacher, who accepted to pose for him as a model and became close friends. In 1908, Gibran went to study art in Paris for two years. While there he met his art study partner and lifelong friend Youssef Howayek. While most of Gibran's early writings were in Arabic, most of his work published after 1918 was in English. His first book for the publishing company Alfred A. Knopf, in 1918, was The Madman, a slim volume of aphorisms and parables written in biblical cadence somewhere between poetry and prose. Gibran also took part in the New York Pen League, also known as the "immigrant poets" (al-mahjar), alongside important Lebanese-American authors such as Ameen Rihani, Elia Abu Madi and Mikhail Naimy, a close friend and distinguished master of Arabic literature, whose descendants Gibran declared to be his own children, and whose nephew, Samir, is a godson of Gibran's. Much of Gibran's writings deal with Christianity, especially on the topic of spiritual love. But his mysticism is a convergence of several different influences : Christianity, Islam, Sufism, Hinduism and theosophy. He wrote : "You are my brother and I love you. I love you when you prostrate yourself in your mosque, and kneel in your church and pray in your synagogue. You and I are sons of one faith - the Spirit." Juliet Thompson, one of Gibran's acquaintances, reported several anecdotes relating to Gibran: She recalls Gibran met `Abdu'l-Bahá, the leader of the Bahá’í Faith at the time of his visit to the United States, circa 1911–1912. Barbara Young, in "This Man from Lebanon: A Study of Khalil Gibran", records Gibran was unable to sleep the night before meeting `Abdu'l-Bahá who sat for a pair of portraits. Thompson reports Gibran saying that all the way through writing of "Jesus, The Son of Man", he thought of `Abdu'l-Bahá. Years later, after the death of `Abdu'l-Bahá, there was a viewing of the movie recording of `Abdu'l-Bahá – Gibran rose to talk and in tears, proclaimed an exalted station of `Abdu'l-Bahá and left the event weeping. His poetry is notable for its use of formal language, as well as insights on topics of life using spiritual terms. Gibran's best-known work is The Prophet, a book composed of twenty-six poetic essays. Its popularity grew markedly during the 1960s with the American counterculture and then with the flowering of the New Age movements. It has remained popular with these and with the wider population to this day. Since it was first published in 1923, The Prophet has never been out of print. Having been translated into more than forty languages, it was one of the bestselling books of the twentieth century in the United States. One of his most notable lines of poetry is from "Sand and Foam" (1926), which reads: "Half of what I say is meaningless, but I say it so that the other half may reach you". This line was used by John Lennon and placed, though in a slightly altered form, into the song "Julia" from The Beatles' 1968 album The Beatles (a.k.a. "The White Album”). Drawing and painting Gibran was an accomplished artist, especially in drawing and watercolour, having attended art school in Paris from 1908 to 1910, pursuing a symbolist and romantic style over then up-and-coming realism. His more than 700 images include portraits of his friends WB Yeats, Carl Jung and August Rodin. A possible Gibran painting was the subject of a June 2012 episode of the PBS TV series History Detectives. Political thought Gibran was by no means a politician. He used to say : "I am not a politician, nor do I wish to become one" and "Spare me the political events and power struggles, as the whole earth is my homeland and all men are my fellow countrymen". Nevertheless, Gibran called for the adoption of Arabic as a national language of Syria, considered from a geographic point of view, not as a political entity. When Gibran met `Abdu'l-Bahá in 1911–12, who traveled to the United States partly to promote peace, Gibran admired the teachings on peace but argued that "young nations like his own" be freed from Ottoman control. Gibran also wrote the famous "Pity The Nation" poem during these years, posthumously published in The Garden of the Prophet. When the Ottomans were finally driven out of Syria during World War I, Gibran's exhilaration was manifested in a sketch called "Free Syria" which appeared on the front page of al-Sa'ih's special "victory" edition. Moreover, in a draft of a play, still kept among his papers, Gibran expressed great hope for national independence and progress. This play, according to Khalil Hawi, "defines Gibran's belief in Syrian nationalism with great clarity, distinguishing it from both Lebanese and Arab nationalism, and showing us that nationalism lived in his mind, even at this late stage, side by side with internationalism.” Death and legacy Gibran died in New York City on April 10, 1931: the cause was determined to be cirrhosis of the liver and tuberculosis. Before his death, Gibran expressed the wish that he be buried in Lebanon. This wish was fulfilled in 1932, when Mary Haskell and his sister Mariana purchased the Mar Sarkis Monastery in Lebanon, which has since become the Gibran Museum. The words written next to Gibran's grave are "a word I want to see written on my grave: I am alive like you, and I am standing beside you. Close your eyes and look around, you will see me in front of you ...." Gibran willed the contents of his studio to Mary Haskell. There she discovered her letters to him spanning twenty-three years. She initially agreed to burn them because of their intimacy, but recognizing their historical value she saved them. She gave them, along with his letters to her which she had also saved, to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Library before she died in 1964. Excerpts of the over six hundred letters were published in "Beloved Prophet" in 1972. Mary Haskell Minis (she wed Jacob Florance Minis in 1923) donated her personal collection of nearly one hundred original works of art by Gibran to the Telfair Museum of Art in Savannah, Georgia in 1950. Haskell had been thinking of placing her collection at the Telfair as early as 1914. In a letter to Gibran, she wrote "I am thinking of other museums ... the unique little Telfair Gallery in Savannah, Ga., that Gari Melchers chooses pictures for. There when I was a visiting child, form burst upon my astonished little soul." Haskell's gift to the Telfair is the largest public collection of Gibran’s visual art in the country, consisting of five oils and numerous works on paper rendered in the artist’s lyrical style, which reflects the influence of symbolism. The future American royalties to his books were willed to his hometown of Bsharri, to be "used for good causes”. Works In Arabic: * Nubthah fi Fan Al-Musiqa (Music, 1905) * Ara'is al-Muruj (Nymphs of the Valley, also translated as Spirit Brides and Brides of the Prairie, 1906) * al-Arwah al-Mutamarrida (Rebellious Spirits, 1908) * al-Ajniha al-Mutakassira (Broken Wings, 1912) * Dam'a wa Ibtisama (A Tear and A Smile, 1914) * al-Mawakib (The Processions, 1919) * al-‘Awāsif (The Tempests, 1920) * al-Bada'i' waal-Tara'if (The New and the Marvellous, 1923) In English, prior to his death: * The Madman (1918) (downloadable free version) * Twenty Drawings (1919) * The Forerunner (1920) * The Prophet, (1923) * Sand and Foam (1926) * Kingdom of the Imagination (1927) * Jesus, The Son of Man (1928) * The Earth Gods (1931) Posthumous, in English: * The Wanderer (1932) * The Garden of the Prophet (1933, Completed by Barbara Young) * Lazarus and his Beloved (Play, 1933) Collections: * Prose Poems (1934) * Secrets of the Heart (1947) * A Treasury of Kahlil Gibran (1951) * A Self-Portrait (1959) * Thoughts and Meditations (1960) * A Second Treasury of Kahlil Gibran (1962) * Spiritual Sayings (1962) * Voice of the Master (1963) * Mirrors of the Soul (1965) * Between Night & Morn (1972) * A Third Treasury of Kahlil Gibran (1975) * The Storm (1994) * The Beloved (1994) * The Vision (1994) * Eye of the Prophet (1995) * The Treasured Writings of Kahlil Gibran (1995) Other: * Beloved Prophet, The love letters of Khalil Gibran and Mary Haskell, and her private journal (1972, edited by Virginia Hilu) Memorials and honors * Lebanese Ministry of Post and Telecommunications published a stamp in his honor in 1971. * Gibran Museum in Bsharri, Lebanon * Gibran Khalil Gibran Garden, Beirut, Lebanon * Gibran Khalil Gibran collectin, Soumaya Museum, Mexico. * Kahlil Gibran Street, Ville Saint-Laurent, Quebec, Canada inaugurated on 27 Sept. 2008 on occasion of the 125th anniversary of his birth. * Gibran Kahlil Gibran Skiing Piste, The Cedars Ski Resort, Lebanon * Kahlil Gibran Memorial Garden in Washington, D.C., dedicated in 1990 * The Kahlil Gibran Chair for Values and Peace, University of Maryland, currently held by Suheil Bushrui * Pavilion K. Gibran at École Pasteur in Montréal, Quebec, Canada * Gibran Memorial Plaque in Copley Square, Boston, Massachusetts see Kahlil Gibran (sculptor). * Khalil Gibran International Academy, a public high school in Brooklyn, NY, opened in September 2007 * Khalil Gibran Park (Parcul Khalil Gibran) in Bucharest, Romania * Gibran Kalil Gibran sculpture on a marble pedestal indoors at Arab Memorial building at Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil * Gibran Khalil Gibran Memorial, in front of Plaza de las Naciones. Buenos Aires. References Wikipedia - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Khalil_Gibran

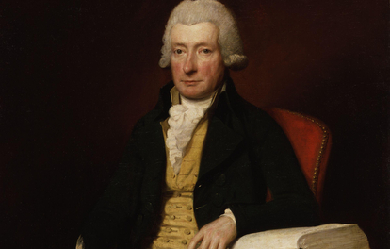

William Cowper (26 November 1731– 25 April 1800) was an English poet and hymnodist. One of the most popular poets of his time, Cowper changed the direction of 18th century nature poetry by writing of everyday life and scenes of the English countryside. In many ways, he was one of the forerunners of Romantic poetry. Samuel Taylor Coleridge called him “the best modern poet”, whilst William Wordsworth particularly admired his poem Yardley-Oak. He was a nephew of the poet Judith Madan.