Richard Le Gallienne (20 January 1866– 15 September 1947) was an English author and poet. The American actress Eva Le Gallienne (1899–1991) was his daughter, by his second marriage. Life and career He was born in Liverpool. He started work in an accountant’s office, but abandoned this job to become a professional writer. The book My Ladies’ Sonnets appeared in 1887, and in 1889 he became, for a brief time, literary secretary to Wilson Barrett. He joined the staff of the newspaper The Star in 1891, and wrote for various papers by the name Logroller. He contributed to The Yellow Book, and associated with the Rhymers’ Club. His first wife, Mildred Lee, died in 1894. They had one daughter, Hesper. In 1897 he married the Danish journalist Julie Norregard, who left him in 1903 and took their daughter Eva to live in Paris. Le Gallienne subsequently became a resident of the United States. He has been credited with the 1906 translation from the Danish of Peter Nansen’s Love’s Trilogy; but most sources and the book itself attribute it to Julie. They were divorced in June 1911. On October 27, 1911, he married Mrs. Irma Perry, née Hinton, whose previous marriage to her first cousin, the painter and sculptor Roland Hinton Perry, had been dissolved in 1904. Le Gallienne and Irma had known each other for some time, and had jointly published an article as early as 1906. Irma’s daughter Gwendolyn Perry subsequently called herself “Gwen Le Gallienne”, but was almost certainly not his natural daughter, having been born in 1900. Le Gallienne and Irma lived in Paris from the late 1920s, where Gwen was by then an established figure in the expatriate bohéme (see, e.g.) and where he wrote a regular newspaper column. Le Gallienne lived in Menton on the French Riviera during the 1940s. During the Second World War Le Gallienne was prevented from returning to his Menton home and lived in Monaco for the rest of the war. Le Gallienne’s house in Menton was occupied by German troops and his library was nearly sent back to Germany as bounty. Le Gallienne appealed to a German officer in Monaco who allowed him to return to Menton to collect his books. During the war Le Gallienne refused to write propaganda for the local German and Italian authorities, and with no income, once collapsed in the street due to hunger. In later times he knew Llewelyn Powys and John Cowper Powys. Asked how to say his name, he told The Literary Digest the stress was “on the last syllable: le gal-i-enn’. As a rule I hear it pronounced as if it were spelled ‘gallion,’ which, of course, is wrong.” (Charles Earle Funk, What’s the Name, Please?, Funk & Wagnalls, 1936.) A number of his works are now available online. He also wrote the foreword to “The Days I Knew” by Lillie Langtry 1925, George H. Doran Company on Murray Hill New York. Works * My Ladies’ Sonnets and Other Vain and Amatorious Verses (1887) * Volumes in Folio (1889) poems * George Meredith: Some Characteristics (1890) * The Book-Bills of Narcissus (1891) * English Poems (1892) * The Religion of a Literary Man (1893) * Robert Louis Stevenson: An Elegy and Other Poems (1895) * Quest of the Golden Girl (1896) novel * Prose Fancies (1896) * Retrospective Reviews (1896) * Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam (1897) * If I Were God (1897) * The Romance Of Zion Chapel (1898) * In Praise of Bishop Valentine (1898) * Young Lives (1899) * Sleeping Beauty and Other Prose Fancies (1900) * The Worshipper Of The Image (1900) * The Love Letters of the King, or The Life Romantic (1901) * An Old Country House (1902) * Odes from the Divan of Hafiz (1903) translation * Old Love Stories Retold (1904) * Painted Shadows (1904) * Romances of Old France (1905) * Little Dinners with the Sphinx and other Prose Fancies (1907) * Omar Repentant (1908) * Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde (1909) Translator * Attitudes and Avowals (1910) essays * October Vagabonds (1910) * New Poems (1910) * The Maker of Rainbows and Other Fairy-Tales and Fables (1912) * The Lonely Dancer and Other Poems (1913) * The Highway to Happiness (1913) * Vanishing Roads and Other Essays (1915) * The Silk-Hat Soldier and Other Poems in War Time (1915) * The Chain Invisible (1916) * Pieces of Eight (1918) * The Junk-Man and Other Poems (1920) * A Jongleur Strayed (1922) poems * Woodstock: An Essay (1923) * The Romantic '90s (1925) memoirs * The Romance of Perfume (1928) * There Was a Ship (1930) * From a Paris Garret (1936) memoirs * The Diary of Samuel Pepys (editor) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Le_Gallienne

_and_brother_Ronald_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

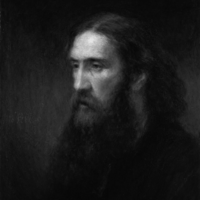

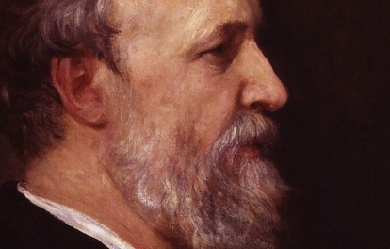

George MacDonald (10 December 1824– 18 September 1905) was a Scottish author, poet, and Christian minister. He was a pioneering figure in the field of fantasy literature and the mentor of fellow writer Lewis Carroll. His writings have been cited as a major literary influence by many notable authors including W. H. Auden, C. S. Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien, Walter de la Mare, E. Nesbit and Madeleine L’Engle. C. S. Lewis wrote that he regarded MacDonald as his “master”: “Picking up a copy of Phantastes one day at a train-station bookstall, I began to read. A few hours later,” said Lewis, “I knew that I had crossed a great frontier.” G. K. Chesterton cited The Princess and the Goblin as a book that had “made a difference to my whole existence”. Elizabeth Yates wrote of Sir Gibbie, “It moved me the way books did when, as a child, the great gates of literature began to open and first encounters with noble thoughts and utterances were unspeakably thrilling.” Even Mark Twain, who initially disliked MacDonald, became friends with him, and there is some evidence that Twain was influenced by MacDonald. Christian author Oswald Chambers (1874–1917) wrote in Christian Disciplines, vol. 1, (pub. 1934) that “it is a striking indication of the trend and shallowness of the modern reading public that George MacDonald’s books have been so neglected”. In addition to his fairy tales, MacDonald wrote several works on Christian apologetics including several that defended his view of Christian Universalism. Early life George MacDonald was born on 10 December 1824 at Huntly, Aberdeenshire, Scotland. His father, a farmer, was one of the MacDonalds of Glen Coe, and a direct descendant of one of the families that suffered in the massacre of 1692. The Doric dialect of the Aberdeenshire area appears in the dialogue of some of his non-fantasy novels. MacDonald grew up in the Congregational Church, with an atmosphere of Calvinism. But MacDonald never felt comfortable with some aspects of Calvinist doctrine; indeed, legend has itt that when the doctrine of predestination was first explained to him, he burst into tears (although assured that he was one of the elect). Later novels, such as Robert Falconer and Lilith, show a distaste for the idea that God’s electing love is limited to some and denied to others. MacDonald graduated from the University of Aberdeen, and then went to London, studying at Highbury College for the Congregational ministry. In 1850 he was appointed pastor of Trinity Congregational Church, Arundel, but his sermons (preaching God’s universal love and the possibility that none would, ultimately, fail to unite with God) met with little favour and his salary was cut in half. Later he was engaged in ministerial work in Manchester. He left that because of poor health, and after a short sojourn in Algiers he settled in London and taught for some time at the University of London. MacDonald was also for a time editor of Good Words for the Young, and lectured successfully in the United States during 1872–1873. Work George MacDonald’s best-known works are Phantastes, The Princess and the Goblin, At the Back of the North Wind, and Lilith, all fantasy novels, and fairy tales such as “The Light Princess”, “The Golden Key”, and “The Wise Woman”. “I write, not for children,” he wrote, “but for the child-like, whether they be of five, or fifty, or seventy-five.” MacDonald also published some volumes of sermons, the pulpit not having proved an unreservedly successful venue. MacDonald also served as a mentor to Lewis Carroll (the pen-name of Rev. Charles Lutwidge Dodgson); it was MacDonald’s advice, and the enthusiastic reception of Alice by MacDonald’s many sons and daughters, that convinced Carroll to submit Alice for publication. Carroll, one of the finest Victorian photographers, also created photographic portraits of several of the MacDonald children. MacDonald was also friends with John Ruskin and served as a go-between in Ruskin’s long courtship with Rose La Touche. MacDonald was acquainted with most of the literary luminaries of the day; a surviving group photograph shows him with Tennyson, Dickens, Wilkie Collins, Trollope, Ruskin, Lewes, and Thackeray. While in America he was a friend of Longfellow and Walt Whitman. In 1877 he was given a civil list pension. From 1879 he and his family moved to Bordighera in a place much loved by British expatriates, the Riviera dei Fiori in Liguria, Italy, almost on the French border. In that locality there also was an Anglican Church, which he attended. Deeply enamoured of the Riviera, he spent there 20 years, writing almost half of his whole literary production, especially the fantasy work. In that Ligurian town MacDonald founded a literary studio named Casa Coraggio (Bravery House), which soon became one of the most renowned cultural centres of that period, well attended by British and Italian travellers, and by locals. In that house representations were often held of classic plays, and readings were given of Dante and Shakespeare. In 1900 he moved into St George’s Wood, Haslemere, a house designed for him by his son, Robert Falconer MacDonald, and the building overseen by his eldest son, Greville MacDonald. He died on 18 September 1905 in Ashtead, (Surrey). He was cremated and his ashes buried in Bordighera, in the English cemetery, along with his wife Louisa and daughters Lilia and Grace. As hinted above, MacDonald’s use of fantasy as a literary medium for exploring the human condition greatly influenced a generation of such notable authors as C. S. Lewis (who featured him as a character in his The Great Divorce), J. R. R. Tolkien, and Madeleine L’Engle. MacDonald’s non-fantasy novels, such as Alec Forbes, had their influence as well; they were among the first realistic Scottish novels, and as such MacDonald has been credited with founding the “kailyard school” of Scottish writing. His son Greville MacDonald became a noted medical specialist, a pioneer of the Peasant Arts movement, and also wrote numerous fairy tales for children. Greville ensured that new editions of his father’s works were published. Another son, Ronald MacDonald, was also a novelist. Ronald’s son, Philip MacDonald, (George MacDonald’s grandson) became a very well known Hollywood screenwriter. Theology MacDonald rejected the doctrine of penal substitutionary atonement as developed by John Calvin, which argues that Christ has taken the place of sinners and is punished by the wrath of God in their place, believing that in turn it raised serious questions about the character and nature of God. Instead, he taught that Christ had come to save people from their sins, and not from a Divine penalty for their sins. The problem was not the need to appease a wrathful God but the disease of cosmic evil itself. George MacDonald frequently described the Atonement in terms similar to the Christus Victor theory. MacDonald posed the rhetorical question, “Did he not foil and slay evil by letting all the waves and billows of its horrid sea break upon him, go over him, and die without rebound—spend their rage, fall defeated, and cease? Verily, he made atonement!” MacDonald was convinced that God does not punish except to amend, and that the sole end of His greatest anger is the amelioration of the guilty. As the doctor uses fire and steel in certain deep-seated diseases, so God may use hell-fire if necessary to heal the hardened sinner. MacDonald declared, “I believe that no hell will be lacking which would help the just mercy of God to redeem his children.” MacDonald posed the rhetorical question, “When we say that God is Love, do we teach men that their fear of Him is groundless?” He replied, “No. As much as they fear will come upon them, possibly far more.... The wrath will consume what they call themselves; so that the selves God made shall appear.” However, true repentance, in the sense of freely chosen moral growth, is essential to this process, and, in MacDonald’s optimistic view, inevitable for all beings (see universal reconciliation). He recognised the theoretical possibility that, bathed in the eschatological divine light, some might perceive right and wrong for what they are but still refuse to be transfigured by operation of God’s fires of love, but he did not think this likely. In this theology of divine punishment, MacDonald stands in opposition to Augustine of Hippo, and in agreement with the Greek Church Fathers Clement of Alexandria, Origen, and St. Gregory of Nyssa, although it is unknown whether MacDonald had a working familiarity with Patristics or Eastern Orthodox Christianity. At least an indirect influence is likely, because F. D. Maurice, who influenced MacDonald, knew the Greek Fathers, especially Clement, very well. MacDonald states his theological views most distinctly in the sermon Justice found in the third volume of Unspoken Sermons. In his introduction to George MacDonald: An Anthology, C. S. Lewis speaks highly of MacDonald’s theology: “This collection, as I have said, was designed not to revive MacDonald’s literary reputation but to spread his religious teaching. Hence most of my extracts are taken from the three volumes of Unspoken Sermons. My own debt to this book is almost as great as one man can owe to another: and nearly all serious inquirers to whom I have introduced it acknowledge that it has given them great help—sometimes indispensable help toward the very acceptance of the Christian faith. ... I know hardly any other writer who seems to be closer, or more continually close, to the Spirit of Christ Himself. Hence his Christ-like union of tenderness and severity. Nowhere else outside the New Testament have I found terror and comfort so intertwined.... In making this collection I was discharging a debt of justice. I have never concealed the fact that I regarded him as my master; indeed I fancy I have never written a book in which I did not quote from him. But it has not seemed to me that those who have received my books kindly take even now sufficient notice of the affiliation. Honesty drives me to emphasize it.” Bibliography Fantasy * Phantastes: A Fairie Romance for Men and Women (1858) * “Cross Purposes” (1862) * Adela Cathcart (1864), containing “The Light Princess”, “The Shadows”, and other short stories * The Portent: A Story of the Inner Vision of the Highlanders, Commonly Called “The Second Sight” (1864) * Dealings with the Fairies (1867), containing “The Golden Key”, “The Light Princess”, “The Shadows”, and other short stories * At the Back of the North Wind (1871) * Works of Fancy and Imagination (1871), including Within and Without, “Cross Purposes”, “The Light Princess”, “The Golden Key”, and other works * The Princess and the Goblin (1872) * The Wise Woman: A Parable (1875) (Published also as “The Lost Princess: A Double Story”; or as “A Double Story”.) * The Gifts of the Child Christ and Other Tales (1882; republished as Stephen Archer and Other Tales) * The Day Boy and the Night Girl (1882) * The Princess and Curdie (1883), a sequel to The Princess and the Goblin * The Flight of the Shadow (1891) * Lilith: A Romance (1895) Realistic fiction * David Elginbrod (1863; republished as The Tutor’s First Love), originally published in three volumes * Alec Forbes of Howglen (1865; republished as The Maiden’s Bequest) * Annals of a Quiet Neighbourhood (1867) * Guild Court: A London Story (1868) * Robert Falconer (1868; republished as The Musician’s Quest) * The Seaboard Parish (1869), a sequel to Annals of a Quiet Neighbourhood * Ranald Bannerman’s Boyhood (1871) * Wilfrid Cumbermede (1871–72) * The Vicar’s Daughter (1871–72), a sequel to Annals of a Quiet Neighborhood and The Seaboard Parish * The History of Gutta Percha Willie, the Working Genius (1873), usually called simply Gutta Percha Willie * Malcolm (1875) * St. George and St. Michael (1876) * Thomas Wingfold, Curate (1876; republished as The Curate’s Awakening) * The Marquis of Lossie (1877; republished as The Marquis’ Secret), the second book of Malcolm * Paul Faber, Surgeon (1879; republished as The Lady’s Confession), a sequel to Thomas Wingfold, Curate * Sir Gibbie (1879; republished as The Baronet’s Song) * Mary Marston (1881; republished as A Daughter’s Devotion) * Warlock o’ Glenwarlock (1881; republished as Castle Warlock and The Laird’s Inheritance) * Weighed and Wanting (1882; republished as A Gentlewoman’s Choice) * Donal Grant (1883; republished as The Shepherd’s Castle), a sequel to Sir Gibbie * What’s Mine’s Mine (1886; republished as The Highlander’s Last Song) * Home Again: A Tale (1887; republished as The Poet’s Homecoming) * The Elect Lady (1888; republished as The Landlady’s Master) * A Rough Shaking (1891) * There and Back (1891; republished as The Baron’s Apprenticeship), a sequel to Thomas Wingfold, Curate and Paul Faber, Surgeon * Heather and Snow (1893; republished as The Peasant Girl’s Dream) * Salted with Fire (1896; republished as The Minister’s Restoration) * Far Above Rubies (1898) Poetry * Twelve of the Spiritual Songs of Novalis (1851), privately printed translation of the poetry of Novalis * Within and Without: A Dramatic Poem (1855) * Poems (1857) * “A Hidden Life” and Other Poems (1864) * “The Disciple” and Other Poems (1867) * Exotics: A Translation of the Spiritual Songs of Novalis, the Hymn-book of Luther, and Other Poems from the German and Italian (1876) * Dramatic and Miscellaneous Poems (1876) * Diary of an Old Soul (1880) * A Book of Strife, in the Form of the Diary of an Old Soul (1880), privately printed * The Threefold Cord: Poems by Three Friends (1883), privately printed, with Greville Matheson and John Hill MacDonald * Poems (1887) * The Poetical Works of George MacDonald, 2 Volumes (1893) * Scotch Songs and Ballads (1893) * Rampolli: Growths from a Long-planted Root (1897) Nonfiction * Unspoken Sermons (1867) * England’s Antiphon (1868, 1874) * The Miracles of Our Lord (1870) * Cheerful Words from the Writing of George MacDonald (1880), compiled by E. E. Brown * Orts: Chiefly Papers on the Imagination, and on Shakespeare (1882) * “Preface” (1884) to Letters from Hell (1866) by Valdemar Adolph Thisted * The Tragedie of Hamlet, Prince of Denmarke: A Study With the Test of the Folio of 1623 (1885) * Unspoken Sermons, Second Series (1885) * Unspoken Sermons, Third Series (1889) * A Cabinet of Gems, Cut and Polished by Sir Philip Sidney; Now, for the More Radiance, Presented Without Their Setting by George MacDonald (1891) * The Hope of the Gospel (1892) * A Dish of Orts (1893) * Beautiful Thoughts from George MacDonald (1894), compiled by Elizabeth Dougall In popular culture * (Alphabetical by artist) * Christian celtic punk band Ballydowse have a song called “George MacDonald” on their album Out of the Fertile Crescent. The song is both taken from MacDonald’s poem “My Two Geniuses” and liberally quoted from Phantastes. * American classical composer John Craton has utilized several of MacDonald’s stories in his works, including “The Gray Wolf” (in a tone poem of the same name for solo mandolin– 2006) and portions of “The Cruel Painter”, Lilith, and The Light Princess (in Three Tableaux from George MacDonald for mandolin, recorder, and cello– 2011). * Contemporary new-age musician Jeff Johnson wrote a song titled “The Golden Key” based on George MacDonald’s story of the same name. He has also written several other songs inspired by MacDonald and the Inklings. * Jazz pianist and recording artist Ray Lyon has a song on his CD Beginning to See (2007), called “Up The Spiral Stairs”, which features lyrics from MacDonald’s 26 and 27 September devotional readings from the book Diary of an Old Soul. * A verse from The Light Princess is cited in the “Beauty and the Beast” song by Nightwish. * Rock group The Waterboys titled their album Room to Roam (1990) after a passage in MacDonald’s Phantastes, also found in Lilith. The title track of the album comprises a MacDonald poem from the text of Phantastes set to music by the band. The novels Lilith and Phantastes are both named as books in a library, in the title track of another Waterboys album, Universal Hall (2003). (The Waterboys have also quoted from C. S. Lewis in several songs, including “Church Not Made With Hands” and “Further Up, Further In”, confirming the enduring link in modern pop culture between MacDonald and Lewis.) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_MacDonald

Siegfried Loraine Sassoon (8 September 1886 – 1 September 1967) was an English poet, author and soldier. Decorated for bravery on the Western Front, he became one of the leading poets of the First World War. His poetry both described the horrors of the trenches, and satirised the patriotic pretensions of those who, in Sassoon's view, were responsible for a vainglorious war. He later won acclaim for his prose work, notably his three-volume fictionalised autobiography, collectively known as the "Sherston Trilogy". Motivated by patriotism, Sassoon joined the British Army just as the threat of World War I was realised, and was in service with the Sussex Yeomanry on the day the United Kingdom declared war (4 August 1914). He broke his arm badly in a riding accident and was put out of action before even leaving England, spending the spring of 1915 convalescing.

John Clare (13 July 1793 – 20 May 1864) was an English poet, the son of a farm labourer, who came to be known for his celebratory representations of the English countryside and his lamentation of its disruption. His poetry underwent a major re-evaluation in the late 20th century and he is often now considered to be among the most important 19th-century poets. His biographer Jonathan Bate states that Clare was "the greatest labouring-class poet that England has ever produced. No one has ever written more powerfully of nature, of a rural childhood, and of the alienated and unstable self”. Early life Clare was born in Helpston, six miles to the north of the city of Peterborough. In his life time, the village was in the Soke of Peterborough in Northamptonshire and his memorial calls him "The Northamptonshire Peasant Poet". Helpston now lies in the Peterborough unitary authority of Cambridgeshire. He became an agricultural labourer while still a child; however, he attended school in Glinton church until he was twelve. In his early adult years, Clare became a pot-boy in the Blue Bell public house and fell in love with Mary Joyce; but her father, a prosperous farmer, forbade her to meet him. Subsequently he was a gardener at Burghley House. He enlisted in the militia, tried camp life with Gypsies, and worked in Pickworth as a lime burner in 1817. In the following year he was obliged to accept parish relief. Malnutrition stemming from childhood may be the main culprit behind his 5-foot stature and may have contributed to his poor physical health in later life. Early poems Clare had bought a copy of Thomson's Seasons and began to write poems and sonnets. In an attempt to hold off his parents' eviction from their home, Clare offered his poems to a local bookseller named Edward Drury. Drury sent Clare's poetry to his cousin John Taylor of the publishing firm of Taylor & Hessey, who had published the work of John Keats. Taylor published Clare's Poems Descriptive of Rural Life and Scenery in 1820. This book was highly praised, and in the next year his Village Minstrel and other Poems were published. Midlife He had married Martha ("Patty") Turner in 1820. An annuity of 15 guineas from the Marquess of Exeter, in whose service he had been, was supplemented by subscription, so that Clare became possessed of £45 annually, a sum far beyond what he had ever earned. Soon, however, his income became insufficient, and in 1823 he was nearly penniless. The Shepherd's Calendar (1827) met with little success, which was not increased by his hawking it himself. As he worked again in the fields his health temporarily improved; but he soon became seriously ill. Earl FitzWilliam presented him with a new cottage and a piece of ground, but Clare could not settle in his new home. Clare was constantly torn between the two worlds of literary London and his often illiterate neighbours; between the need to write poetry and the need for money to feed and clothe his children. His health began to suffer, and he had bouts of severe depression, which became worse after his sixth child was born in 1830 and as his poetry sold less well. In 1832, his friends and his London patrons clubbed together to move the family to a larger cottage with a smallholding in the village of Northborough, not far from Helpston. However, he felt only more alienated. His last work, the Rural Muse (1835), was noticed favourably by Christopher North and other reviewers, but this was not enough to support his wife and seven children. Clare's mental health began to worsen. As his alcohol consumption steadily increased along with his dissatisfaction with his own identity, Clare's behaviour became more erratic. A notable instance of this behaviour was demonstrated in his interruption of a performance of The Merchant of Venice, in which Clare verbally assaulted Shylock. He was becoming a burden to Patty and his family, and in July 1837, on the recommendation of his publishing friend, John Taylor, Clare went of his own volition (accompanied by a friend of Taylor's) to Dr Matthew Allen's private asylum High Beach near Loughton, in Epping Forest. Taylor had assured Clare that he would receive the best medical care. Later life and death During his first few asylum years in Essex (1837–1841), Clare re-wrote famous poems and sonnets by Lord Byron. His own version of Child Harold became a lament for past lost love, and Don Juan, A Poem became an acerbic, misogynistic, sexualised rant redolent of an aging Regency dandy. Clare also took credit for Shakespeare's plays, claiming to be the Renaissance genius himself. "I'm John Clare now," the poet claimed to a newspaper editor, "I was Byron and Shakespeare formerly." In 1841, Clare left the asylum in Essex, to walk home, believing that he was to meet his first love Mary Joyce; Clare was convinced that he was married with children to her and Martha as well. He did not believe her family when they told him she had died accidentally three years earlier in a house fire. He remained free, mostly at home in Northborough, for the five months following, but eventually Patty called the doctors in. Between Christmas and New Year in 1841, Clare was committed to the Northampton General Lunatic Asylum (now St Andrew's Hospital). Upon Clare's arrival at the asylum, the accompanying doctor, Fenwick Skrimshire, who had treated Clare since 1820, completed the admission papers. To the enquiry "Was the insanity preceded by any severe or long-continued mental emotion or exertion?", Dr Skrimshire entered: "After years of poetical prosing." He remained here for the rest of his life under the humane regime of Dr Thomas Octavius Prichard, encouraged and helped to write. Here he wrote possibly his most famous poem, I Am. He died on 20 May 1864, in his 71st year. His remains were returned to Helpston for burial in St Botolph’s churchyard. Today, children at the John Clare School, Helpston's primary, parade through the village and place their 'midsummer cushions' around Clare's gravestone (which has the inscriptions "To the Memory of John Clare The Northamptonshire Peasant Poet" and "A Poet is Born not Made") on his birthday, in honour of their most famous resident. The thatched cottage where he was born was bought by the John Clare Education & Environment Trust in 2005 and is restoring the cottage to its 18th century state. Poetry In his time, Clare was commonly known as "the Northamptonshire Peasant Poet". Since his formal education was brief, Clare resisted the use of the increasingly standardised English grammar and orthography in his poetry and prose. Many of his poems would come to incorporate terms used locally in his Northamptonshire dialect, such as 'pooty' (snail), 'lady-cow' (ladybird), 'crizzle' (to crisp) and 'throstle' (song thrush). In his early life he struggled to find a place for his poetry in the changing literary fashions of the day. He also felt that he did not belong with other peasants. Clare once wrote "I live here among the ignorant like a lost man in fact like one whom the rest seemes careless of having anything to do with—they hardly dare talk in my company for fear I should mention them in my writings and I find more pleasure in wandering the fields than in musing among my silent neighbours who are insensible to everything but toiling and talking of it and that to no purpose.” It is common to see an absence of punctuation in many of Clare's original writings, although many publishers felt the need to remedy this practice in the majority of his work. Clare argued with his editors about how it should be presented to the public. Clare grew up during a period of massive changes in both town and countryside as the Industrial Revolution swept Europe. Many former agricultural workers, including children, moved away from the countryside to over-crowded cities, following factory work. The Agricultural Revolution saw pastures ploughed up, trees and hedges uprooted, the fens drained and the common land enclosed. This destruction of a centuries-old way of life distressed Clare deeply. His political and social views were predominantly conservative ("I am as far as my politics reaches 'King and Country'—no Innovations in Religion and Government say I."). He refused even to complain about the subordinate position to which English society relegated him, swearing that "with the old dish that was served to my forefathers I am content." His early work delights both in nature and the cycle of the rural year. Poems such as Winter Evening, Haymaking and Wood Pictures in Summer celebrate the beauty of the world and the certainties of rural life, where animals must be fed and crops harvested. Poems such as Little Trotty Wagtail show his sharp observation of wildlife, though The Badger shows his lack of sentiment about the place of animals in the countryside. At this time, he often used poetic forms such as the sonnet and the rhyming couplet. His later poetry tends to be more meditative and use forms similar to the folks songs and ballads of his youth. An example of this is Evening. His knowledge of the natural world went far beyond that of the major Romantic poets. However, poems such as I Am show a metaphysical depth on a par with his contemporary poets and many of his pre-asylum poems deal with intricate play on the nature of linguistics. His 'bird's nest poems', it can be argued, illustrate the self-awareness, and obsession with the creative process that captivated the romantics. Clare was the most influential poet, aside from Wordsworth to practice in an older style. Revival of interest in the twentieth century Clare was relatively forgotten during the later nineteenth century, but interest in his work was revived by Arthur Symons in 1908, Edmund Blunden in 1920 and John and Anne Tibble in their ground-breaking 1935 2-volume edition. Benjamin Britten set some of 'May' from A Shepherd's Calendar in his Spring Symphony of 1948, and included a setting of The Evening Primrose in his Five Flower Songs Copyright to much of his work has been claimed since 1965 by the editor of the Complete Poetry (OUP, 9 vols., 1984–2003), Professor Eric Robinson though these claims were contested. Recent publishers have refused to acknowledge the claim (especially in recent editions from Faber and Carcanet) and it seems the copyright is now defunct. The John Clare Trust purchased Clare Cottage in Helpston in 2005, preserving it for future generations. In May 2007 the Trust gained £1.m of funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund and commissioned Jefferson Sheard Architects to create the new landscape design and Visitor Centre, including a cafe, shop and exhibition space. The Cottage has been restored using traditional building methods and opened to the public. The largest collection of original Clare manuscripts are housed at Peterborough Museum, where they are available to view by appointment. Since 1993, the John Clare Society of North America has organised an annual session of scholarly papers concerning John Clare at the annual Convention of the Modern Language Association of America. Poetry collections by Clare (chronological) * Poems Descriptive of Rural Life and Scenery. London, 1820. * The Village Minstrel, and Other Poems. London, 1821. * The Shepherd's Calendar with Village Stories and Other Poems. London, 1827 * The Rural Muse. London, 1835. * Sonnet. London 1841 * First Love * Snow Storm. * The Firetail. * The Badger – Time unknown References Wikipedia - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Clare

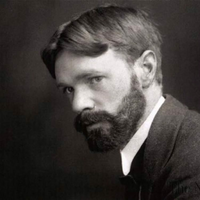

David Herbert Richards Lawrence (11 September 1885 – 2 March 1930) was an English novelist, poet, playwright, essayist, literary critic and painter who published as D. H. Lawrence. His collected works represent an extended reflection upon the dehumanising effects of modernity and industrialisation. In them, Lawrence confronts issues relating to emotional health and vitality, spontaneity, and instinct. Lawrence’s opinions earned him many enemies and he endured official persecution, censorship, and misrepresentation of his creative work throughout the second half of his life, much of which he spent in a voluntary exile which he called his “savage pilgrimage”. At the time of his death, his public reputation was that of a pornographer who had wasted his considerable talents. E. M. Forster, in an obituary notice, challenged this widely held view, describing him as, “The greatest imaginative novelist of our generation”. Later, the influential Cambridge critic F. R. Leavis championed both his artistic integrity and his moral seriousness, placing much of Lawrence's fiction within the canonical “great tradition” of the English novel. Lawrence is now valued by many as a visionary thinker and significant representative of modernism in English literature.

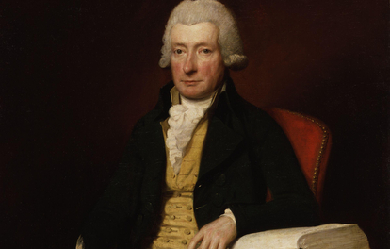

William Cowper (26 November 1731– 25 April 1800) was an English poet and hymnodist. One of the most popular poets of his time, Cowper changed the direction of 18th century nature poetry by writing of everyday life and scenes of the English countryside. In many ways, he was one of the forerunners of Romantic poetry. Samuel Taylor Coleridge called him “the best modern poet”, whilst William Wordsworth particularly admired his poem Yardley-Oak. He was a nephew of the poet Judith Madan.

John Greenleaf Whittier (December 17, 1807 – September 7, 1892) was an American Quaker poet and advocate of the abolition of slavery in the United States. Frequently listed as one of the Fireside Poets, he was influenced by the Scottish poet Robert Burns. Whittier is remembered particularly for his anti-slavery writings as well as his book Snow-Bound. Early life and work John Greenleaf Whittier was born to John and Abigail (Hussey) at their rural homestead in Haverhill, Massachusetts, on December 17, 1807. His middle name is thought to mean 'feuillevert' after his Huguenot forbears. He grew up on the farm in a household with his parents, a brother and two sisters, a maternal aunt and paternal uncle, and a constant flow of visitors and hired hands for the farm. As a boy, it was discovered that Whittier was color-blind when he was unable to see a difference between ripe and unripe strawberries. Their farm was not very profitable and there was only enough money to get by. Whittier himself was not cut out for hard farm labor and suffered from bad health and physical frailty his whole life. Although he received little formal education, he was an avid reader who studied his father's six books on Quakerism until their teachings became the foundation of his ideology. Whittier was heavily influenced by the doctrines of his religion, particularly its stress on humanitarianism, compassion, and social responsibility. Whittier was first introduced to poetry by a teacher. His sister sent his first poem, "The Exile's Departure", to the Newburyport Free Press without his permission and its editor, William Lloyd Garrison, published it on June 8, 1826. Garrison as well as another local editor encouraged Whittier to attend the recently opened Haverhill Academy. To raise money to attend the school, Whittier became a shoemaker for a time, and a deal was made to pay part of his tuition with food from the family farm. Before his second term, he earned money to cover tuition by serving as a teacher in a one-room schoolhouse in what is now Merrimac, Massachusetts. He attended Haverhill Academy from 1827 to 1828 and completed a high school education in only two terms. Garrison gave Whittier the job of editor of the National Philanthropist, a Boston-based temperance weekly. Shortly after a change in management, Garrison reassigned him as editor of the weekly American Manufacturer in Boston. Whittier became an out-spoken critic of President Andrew Jackson, and by 1830 was editor of the prominent New England Weekly Review in Hartford, Connecticut, the most influential Whig journal in New England. In 1833 he published The Song of the Vermonters, 1779, which he had anonymously inserted in The New England Magazine. The poem was erroneously attributed to Ethan Allen for nearly sixty years. Abolitionist activity During the 1830s, Whittier became interested in politics but, after losing a Congressional election at age twenty-five, he suffered a nervous breakdown and returned home. The year 1833 was a turning point for Whittier; he resurrected his correspondence with Garrison, and the passionate abolitionist began to encourage the young Quaker to join his cause. In 1833, Whittier published the antislavery pamphlet Justice and Expediency, and from there dedicated the next twenty years of his life to the abolitionist cause. The controversial pamphlet destroyed all of his political hopes — as his demand for immediate emancipation alienated both northern businessmen and southern slaveholders — but it also sealed his commitment to a cause that he deemed morally correct and socially necessary. He was a founding member of the American Anti-Slavery Society and signed the Anti-Slavery Declaration of 1833, which he often considered the most significant action of his life. Whittier's political skill made him useful as a lobbyist, and his willingness to badger anti-slavery congressional leaders into joining the abolitionist cause was invaluable. From 1835 to 1838, he traveled widely in the North, attending conventions, securing votes, speaking to the public, and lobbying politicians. As he did so, Whittier received his fair share of violent responses, being several times mobbed, stoned, and run out of town. From 1838 to 1840, he was editor of The Pennsylvania Freeman in Philadelphia, one of the leading antislavery papers in the North, formerly known as the National Enquirer. In May 1838, the publication moved its offices to the newly opened Pennsylvania Hall on North Sixth Street, which was shortly after burned by a pro-slavery mob. Whittier also continued to write poetry and nearly all of his poems in this period dealt with the problem of slavery. By the end of the 1830s, the unity of the abolitionist movement had begun to fracture. Whittier stuck to his belief that moral action apart from political effort was futile. He knew that success required legislative change, not merely moral suasion. This opinion alone engendered a bitter split from Garrison,[citation needed] and Whittier went on to become a founding member of the Liberty Party in 1839. In 1840 he attended the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London. By 1843, he was announcing the triumph of the fledgling party: "Liberty party is no longer an experiment. It is vigorous reality, exerting... a powerful influence". Whittier also unsuccessfully encouraged Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow to join the party. He took editing jobs with the Middlesex Standard in Lowell, Massachusetts and the Essex Transcript in Amesbury until 1844. While in Lowell, he met Lucy Larcom, who became a lifelong friend. In 1845, he began writing his essay "The Black Man" which included an anecdote about John Fountain, a free black who was jailed in Virginia for helping slaves escape. After his release, Fountain went on a speaking tour and thanked Whittier for writing his story. Around this time, the stresses of editorial duties, worsening health, and dangerous mob violence caused him to have a physical breakdown. Whittier went home to Amesbury, and remained there for the rest of his life, ending his active participation in abolition. Even so, he continued to believe that the best way to gain abolitionist support was to broaden the Liberty Party's political appeal, and Whittier persisted in advocating the addition of other issues to their platform. He eventually participated in the evolution of the Liberty Party into the Free Soil Party, and some say his greatest political feat was convincing Charles Sumner to run on the Free-Soil ticket for the U.S. Senate in 1850. Beginning in 1847, Whittier was editor of Gamaliel Bailey's The National Era, one of the most influential abolitionist newspapers in the North. For the next ten years it featured the best of his writing, both as prose and poetry. Being confined to his home and away from the action offered Whittier a chance to write better abolitionist poetry; he was even poet laureate for his party. Whittier's poems often used slavery to represent all kinds of oppression (physical, spiritual, economic), and his poems stirred up popular response because they appealed to feelings rather than logic. Whittier produced two collections of antislavery poetry: Poems Written during the Progress of the Abolition Question in the United States, between 1830 and 1838 and Voices of Freedom (1846). He was an elector in the presidential election of 1860 and of 1864, voting for Abraham Lincoln both times. The passage of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865 ended both slavery and his public cause, so Whittier turned to other forms of poetry for the remainder of his life. Criticism Nathaniel Hawthorne dismissed Whittier's Literary Recreations and Miscellanies (1854): "Whittier's book is poor stuff! I like the man, but have no high opinion either of his poetry or his prose." Editor George Ripley, however, found Whittier's poetry refreshing and said it had a "stately movement of versification, grandeur of imagery, a vein of tender and solemn pathos, cheerful trust" and a "pure and ennobling character". Boston critic Edwin Percy Whipple noted Whittier's moral and ethical tone mingled with sincere emotion. He wrote, "In reading this last volume, I feel as if my soul had taken a bath in holy water." Later scholars and critics questioned the depth of Whittier's poetry. One was Karl Keller, who noted, "Whittier has been a writer to love, not to belabor." Influence and legacy Whittier was particularly supportive of women writers, including Alice Cary, Phoebe Cary, Sarah Orne Jewett, Lucy Larcom, and Celia Thaxter. He was especially influential in prose writings by Jewett, with whom he shared a belief in the moral quality of literature and an interest New England folklore. Jewett dedicated one of her books to him and modeled several of her characters after people in Whittier's life. Whittier's family farm, known as the John Greenleaf Whittier Homestead or simply "Whittier's Birthplace", is now a historic site open to the public. His later residence in Amesbury, where he lived for 56 years, is also open to the public, and is now known as the John Greenleaf Whittier Home. Whittier's hometown of Haverhill has named many buildings and landmarks in his honor including J.G. Whittier Middle School, Greenleaf Elementary, and Whittier Regional Vocational Technical High School. Numerous other schools around the country also bear his name. A bridge named for Whittier, built in the style of the Sagamore and Bourne Bridges, carries Interstate 95 from Amesbury to Newburyport over the Merrimack River. A covered bridge spanning the Bearcamp River in Ossipee, New Hampshire is also named for Whittier, as is a nearby mountain. The city of Whittier, California is named after the poet, as are the communities of Whittier, Alaska, and Whittier, Iowa, the Minneapolis neighborhood of Whittier, the Denver, Colorado, neighborhood of Whittier, and the town of Greenleaf, Idaho. Both Whittier College and Whittier Law School are also named after him. A park in the Saint Boniface area of Winnipeg is named after the poet in recognition of his poem "The Red River Voyageur". Whittier Education Campus in Washington, DC is named in his honor. The alternate history story P.'s Correspondence (1846) by Nathaniel Hawthorne, considered the first such story ever published in English, includes the notice "Whittier, a fiery Quaker youth, to whom the muse had perversely assigned a battle-trumpet, got himself lynched, in South Carolina". The date of that event in Hawthorne's invented timeline was 1835. Whittier was one of thirteen writers in the 1897 card game Authors and referenced his writings "Laus Deo", "Among the Hills", Snow-bound, and "The Eternal Goodness". He was removed from the card game when it was reissued in 1987. LIST OF WORKS Poetry collections Poems written during the Progress of the Abolition Question in the United States (1837) Lays of My Home (1843) Voices of Freedom (1846) Songs of Labor (1850) The Chapel of the Hermits (1853) Le Marais du Cygne (September 1858 Atlantic Monthly) Home Ballads (1860) The Furnace Blast (1862) Maud Muller (1856) In War Time (1864) Snow-Bound (1866) The Tent on the Beach (1867) Among the Hills (1869) Whittier's Poems Complete (1874)[citation needed] *The Pennsylvania Pilgrim (1872) The Vision of Echard (1878) The King's Missive (1881) Saint Gregory's Guest (1886) At Sundown (1890) Prose The Stranger in Lowell (1845) The Supernaturalism of New England (1847) Leaves from Margaret Smith's Journal (1849) Old Portraits and Modern Sketches (1850) Literary Recreations and Miscellanies (1854) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Greenleaf_Whittier

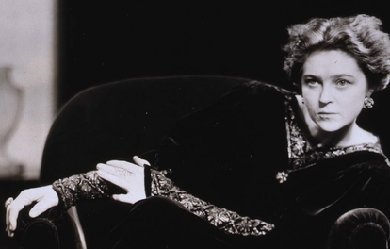

Amy Lawrence Lowell (February 9, 1874 – May 12, 1925) was an American poet of the imagist school from Brookline, Massachusetts, who posthumously won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1926. Amy was born into Brookline’s Lowell family, sister to astronomer Percival Lowell and Harvard president Abbott Lawrence Lowell. She never attended college because her family did not consider it proper for a woman to do so. She compensated for this lack with avid reading and near-obsessive book collecting. She lived as a socialite and travelled widely, turning to poetry in 1902 (age 28) after being inspired by a performance of Eleonora Duse in Europe.

Juan Antonio Alix. Desapercibido pasó el 180 aniversario del natalicio de Juan Antonio Alix (Moca, 6 septiembre 1833 – Santiago, 15 febrero 1918), recordado por sus décimas Eso e paja pa’ la gaiza, El follón de Yamasá, El negro tras de la oreja, Entre Lucas y Juan Mejía, Cánticos (mejor conocida como A las arandelas) y Los mangos bajitos. Sabemos que tenía una hermana, Carmen Alix Rodríguez, y que sus padres, Juan Mateo Alix, natural de Cabo Haitiano, y María Magdalena Rodríguez, casaron en Moca en 1829. Su madre, hija de Domingo Antonio Rodríguez y Juana de Rojas Valerio, había casado por primera vez con Juan José Espaillat Velilla, con quien había procreado a Juan Francisco, José María y Eloísa Espaillat Rodríguez, esta última esposa de su primo hermano paterno Ulises Francisco Espaillat Quiñones, presidente de la República en 1876. En su entorno familiar materno se descubren interesantes entronques. Una de sus tías fue Tomasina Rodríguez Rojas de Julia, ascendiente de los eminentes médicos Alejandro Llenas Julia y Arturo Grullón Julia, el gestor cultural Rafael Díaz Niese, el historiador mocano Julio Jaime Julia Guzmán, el historiador y político Juan Isidro Jimenes Grullón, el escritor Virgilio Díaz Grullón, el munícipe santiaguero Tomás (Jimmy) Pastoriza Espaillat y el banquero Alejandro Grullón Espaillat. Su tía abuela María Dolores Rojas Valerio de Solano fue madre, entre otros, de Domingo Antonio Solano Rojas, el famoso padre Solano, quien fuera padre, entre otros hijos, de Santiago Petitón y José Antonio Olavarrieta, troncos de las familias Petitón y Olavarrieta, y ascendiente del presidente Rafael Estrella Ureña, el Dr. José Jesús Jiménez Olavarrieta, Maestro de la Medicina Dominicana; el munícipe santiaguero Víctor Espaillat Mera y la ex primera dama Asela Mera de Jorge. De su lado, su tío abuelo Carlos de Rojas Valerio fue padre, entre otros, de Benigno Filomeno de Rojas Ramos, presidente del Congreso Constituyente que adoptó en Moca la Constitución de 1857 y prócer civil de la Guerra de la Restauración, y de Carlos de Rojas Ramos, tronco de la familia Rojas de Moca. Alix casó con Petronila Francisca Liriano Bidó y procreó a Petronila Hortensia (n.1868); Tomasina (f. 19 de marzo de 1940), esposa desde 1892 de José María Benedicto Luisón (papá Cheché), munícipe y presidente del Ayuntamiento de Santiago en varias ocasiones; Olivia Juana Antonia, quien casó con Agustín Bonilla Tavares en 1897; Rosalina (Rocha), quien casó en 1898 con Manuel Malagón Espaillat y fallecida en 1900 a la edad de 23 años; Carmen, fallecida soltera y sin descendencia, y Agripina (Pinona) Alix Liriano, esposa del puertorriqueño Ramón Goico. El matrimonio Benedicto Alix procreó a Graciela, esposa de Narciso Román; Mario, Mercedes, Migdalia, Rafael, Rosa Celia, cónyuge de Eladio Antonio Victoria Morales, y José Tomás Benedicto Alix, esposo de Delia Guzmán. Los hijos de Olivia Juana Antonia Alix de Bonilla, fueron Agustín, Betina, Carlos, Dorila, Emma, casada con Rafael Díaz Espinal; María, cónyuge de Manuel Furcy Bonnelly Fondeur; Nidia Antonia, cónyuge de José Manuel Nicolás Rodríguez, y Zaida Bonilla Alix. De su lado, los hijos de Agripina Alix Liriano fueron Mercedes, Miguel Ángel, Octavio y Juan Goico Alix, este último poeta como su abuelo. La descendencia de Alix alcanza ya la sexta generación, compuesta por niños y jóvenes nacidos a fines del siglo XX y principios del XXI, quienes de seguro desconocen que tienen “detrás de la oreja” a nuestro máximo poeta popular. Instituto Dominicano de Genealogía Referencias Hoy—hoy.com.do/juan-antonio-alix-180-anos/

Jorge Eduardo Eielson (Lima, 13 de abril de 1924 - Milán, 8 de marzo de 2006) fue un poeta y artista peruano. Hijo de una ciudadana limeña y de un estadounidense de origen escandinavo. Cuando tenía siete años fallece su padre. Desde su juventud manifestó su inclinación hacia distintas formas de arte, incluyendo la literatura, las artes visuales y la música. En 1945 gana el Premio Nacional de Poesía con el poemario Reinos, publicado en la revista Historia dirigida por el historiador nacional Jorge Basadre. Al año siguiente obtiene el III Premio Nacional de Teatro 1948 por una obra titulada Maquillage, parcialmente publicada en la revista Espacio y recientemente publicada en su totalidad en libro. En simultáneo a sus primeros textos literarios realiza sus primeras obras gráficas, exponiendo algunas de estas junto a otros objetos en 1948. Ese año lleva a cabo un viaje a París gracias a una beca del gobierno francés, iniciando con ello una suerte de exilio voluntario de su país, al cual retornaría en muchas, aún cuando cortas oportunidades. Vivió la mayor parte del tiempo en Europa y se asentó en Milán (Italia). Su obra literaria se caracteriza por la búsqueda de la pureza en la expresión, procurando una forma que trascienda las limitaciones de la realidad y del lenguaje. Ello lo llevó a dedicarse además de a las letras, a las artes visuales, entregado a una experimentación vanguardista que le permite un diálogo inédito con algunos aspectos de la cultura precolombina peruana, y tomando particularmente como signo una versión propia del Quipu. Por su trabajo como artista recibió en el Perú el Premio Tecnoquímica en 2004. Al año siguiente participó en el proyecto de arte público Itinerarios del sonido, con una pieza que se presentaba en una parada de autobús en el Paseo del Pintor Rosales, en Madrid. El conjunto de su obra poética se ha editado tres veces con el título Poesía escrita, primero en Lima en 1976, luego México en el año 1989 y posteriormente en Colombia, en 1998. Además, en 2005 la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú elaboró una edición especial con toda su obra poética, sumada a selecciones de sus trabajos en prosa y reproducciones de su creación plástica. Junto con los poetas peruanos Blanca Varela, César Calvo, Antonio Cisneros y Luis Hernández, entre otros, es considerado el poeta peruano que mayor influencia ha dejado en el ámbito de la poesía latinoamericana. Poesía: * Reinos (1945) * Canción y muerte de Rolando (1959) * Mutatis mutandis (1967) * Poesía escrita (1976) * Poesía escrita, 2ª edición (1989) * Noche oscura del cuerpo (1989) * Antología (1996) * Nudos, ed. bilingüe (1997) * Poesía escrita, ed. de Martha Canfield (1998) * Sin título (2000) * Celebración (2001) * Canto visibile (2002) * Nudos (2002) * Arte poética, antología (2005) * Del absoluto amor y otros poemas sin título (2005) * De materia verbalis (2005) * Habitación en Roma, ed. de Martha Canfield (2008) * Pytx (2008) * Habitación en Roma, ed. de Sergio Téllez-Pon (Quimera, México, 2009) * Poeta en Roma (2009) Narrativa: * El cuerpo de Giulia-no (1971) * Primera muerte de María (2002) Teatro: * Acto final (1959) * Maquillage. [Obra en dos actos y un prólogo]. Edición y presentación de Ricardo Silva-Santisteban. Colofón de Jesús Cabel. Lima: Universidad Nacional San Luis Gonzaga – Editorial San Marcos, 2012. 62 pp. (Colección Huarango; 6). ISBN 978-612-302-747-6 [Obra ganadora del III Premio Nacional de Teatro 1948 y estrenada el 25 de mayo de 1950 en el teatro de la Asociación de Artistas Aficionados (AAA), bajo la dirección de Joaquín Roca Rey]. Referencias Wikipedia—http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jorge_Eielson

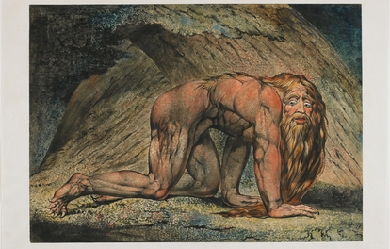

Robert Laurence Binyon, CH (10 August 1869– 10 March 1943) was an English poet, dramatist and art scholar. His most famous work, For the Fallen, is well known for being used in Remembrance Sunday services. Pre-war life Laurence Binyon was born in Lancaster, Lancashire, England. His parents were Frederick Binyon, and Mary Dockray. Mary’s father, Robert Benson Dockray, was the main engineer of the London and Birmingham Railway. The family were Quakers. Binyon studied at St Paul’s School, London. Then he read Classics (Honour Moderations) at Trinity College, Oxford, where he won the Newdigate Prize for poetry in 1891. Immediately after graduating in 1893, Binyon started working for the Department of Printed Books of the British Museum, writing catalogues for the museum and art monographs for himself. In 1895 his first book, Dutch Etchers of the Seventeenth Century, was published. In that same year, Binyon moved into the Museum’s Department of Prints and Drawings, under Campbell Dodgson. In 1909, Binyon became its Assistant Keeper, and in 1913 he was made the Keeper of the new Sub-Department of Oriental Prints and Drawings. Around this time he played a crucial role in the formation of Modernism in London by introducing young Imagist poets such as Ezra Pound, Richard Aldington and H.D. to East Asian visual art and literature. Many of Binyon’s books produced while at the Museum were influenced by his own sensibilities as a poet, although some are works of plain scholarship– such as his four-volume catalogue of all the Museum’s English drawings, and his seminal catalogue of Chinese and Japanese prints. In 1904 he married historian Cicely Margaret Powell, and the couple had three daughters. During those years, Binyon belonged to a circle of artists, as a regular patron of the Wiener Cafe of London. His fellow intellectuals there were Ezra Pound, Sir William Rothenstein, Walter Sickert, Charles Ricketts, Lucien Pissarro and Edmund Dulac. Binyon’s reputation before the war was such that, on the death of the Poet Laureate Alfred Austin in 1913, Binyon was among the names mentioned in the press as his likely successor (others named included Thomas Hardy, John Masefield and Rudyard Kipling; the post went to Robert Bridges). For the Fallen Moved by the opening of the Great War and the already high number of casualties of the British Expeditionary Force, in 1914 Laurence Binyon wrote his For the Fallen, with its Ode of Remembrance, as he was visiting the cliffs on the north Cornwall coast, either at Polzeath or at Portreath (at each of which places there is a plaque commemorating the event, though Binyon himself mentioned Polzeath in a 1939 interview. The confusion may be related to Porteath Farm being near Polzeath). The piece was published by The Times newspaper in September, when public feeling was affected by the recent Battle of Marne. Today Binyon’s most famous poem, For the Fallen, is often recited at Remembrance Sunday services in the UK; is an integral part of Anzac Day services in Australia and New Zealand and of the 11 November Remembrance Day services in Canada. The third and fourth verses of the poem (although often just the fourth) have thus been claimed as a tribute to all casualties of war, regardless of nation. They went with songs to the battle, they were young. Straight of limb, true of eyes, steady and aglow. They were staunch to the end against odds uncounted, They fell with their faces to the foe. They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old: Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn. At the going down of the sun and in the morning, We will remember them. They mingle not with their laughing comrades again; They sit no more at familiar tables of home; They have no lot in our labour of the day-time; They sleep beyond England’s foam Three of Binyon’s poems, including “For the Fallen”, were set by Sir Edward Elgar in his last major orchestra/choral work, The Spirit of England. In 1915, despite being too old to enlist in the First World War, Laurence Binyon volunteered at a British hospital for French soldiers, Hôpital Temporaire d’Arc-en-Barrois, Haute-Marne, France, working briefly as a hospital orderly. He returned in the summer of 1916 and took care of soldiers taken in from the Verdun battlefield. He wrote about his experiences in For Dauntless France (1918) and his poems, “Fetching the Wounded” and “The Distant Guns”, were inspired by his hospital service in Arc-en-Barrois. Artists Rifles, a CD audiobook published in 2004, includes a reading of For the Fallen by Binyon himself. The recording itself is undated and appeared on a 78 rpm disc issued in Japan. Other Great War poets heard on the CD include Siegfried Sassoon, Edmund Blunden, Robert Graves, David Jones and Edgell Rickword. Post-war life After the war, he returned to the British Museum and wrote numerous books on art; in particular on William Blake, Persian art, and Japanese art. His work on ancient Japanese and Chinese cultures offered strongly contextualised examples that inspired, among others, the poets Ezra Pound and W. B. Yeats. His work on Blake and his followers kept alive the then nearly-forgotten memory of the work of Samuel Palmer. Binyon’s duality of interests continued the traditional interest of British visionary Romanticism in the rich strangeness of Mediterranean and Oriental cultures. In 1931, his two volume Collected Poems appeared. In 1932, Binyon rose to be the Keeper of the Prints and Drawings Department, yet in 1933 he retired from the British Museum. He went to live in the country at Westridge Green, near Streatley (where his daughters also came to live during the Second World War). He continued writing poetry. In 1933–1934, Binyon was appointed Norton Professor of Poetry at Harvard University. He delivered a series of lectures on The Spirit of Man in Asian Art, which were published in 1935. Binyon continued his academic work: in May 1939 he gave the prestigious Romanes Lecture in Oxford on Art and Freedom, and in 1940 he was appointed the Byron Professor of English Literature at University of Athens. He worked there until forced to leave, narrowly escaping the German invasion of Greece in April 1941 . He was succeeded by Lord Dunsany, who held the chair in 1940-1941. Binyon had been friends with Ezra Pound since around 1909, and in the 1930s the two became especially close; Pound affectionately called him “BinBin”, and assisted Binyon with his translation of Dante. Another protégé was Arthur Waley, whom Binyon employed at the British Museum. Between 1933 and 1943, Binyon published his acclaimed translation of Dante’s Divine Comedy in an English version of terza rima, made with some editorial assistance by Ezra Pound. Its readership was dramatically increased when Paolo Milano selected it for the “The Portable Dante” in Viking’s Portable Library series. Binyon significantly revised his translation of all three parts for the project, and the volume went through three major editions and eight printings (while other volumes in the same series went out of print) before being replaced by the Mark Musa translation in 1981. At his death he was also working on a major three-part Arthurian trilogy, the first part of which was published after his death as The Madness of Merlin (1947). He died in Dunedin Nursing Home, Bath Road, Reading, on 10 March 1943 after an operation. A funeral service was held at Trinity College Chapel, Oxford, on 13 March 1943. There is a slate memorial in St. Mary’s Church, Aldworth, where Binyon’s ashes were scattered. On 11 November 1985, Binyon was among 16 Great War poets commemorated on a slate stone unveiled in Westminster Abbey’s Poets’ Corner. The inscription on the stone quotes a fellow Great War poet, Wilfred Owen. It reads: “My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity.” Daughters His three daughters Helen, Margaret and Nicolete became artists. Helen Binyon (1904–1979) studied with Paul Nash and Eric Ravilious, illustrating many books for the Oxford University Press, and was also a marionettist. She later taught puppetry and published Puppetry Today (1966) and Professional Puppetry in England (1973). Margaret Binyon wrote children’s books, which were illustrated by Helen. Nicolete, as Nicolete Gray, was a distinguished calligrapher and art scholar. Bibliography of key works Poems and verse * Lyric Poems (1894) * Porphyrion and other Poems (1898) * Odes (1901) * Death of Adam and Other Poems (1904) * London Visions (1908) * England and Other Poems (1909) * “For The Fallen”, The Times, 21 September 1914 * Winnowing Fan (1914) * The Anvil (1916) * The Cause (1917) * The New World: Poems (1918) * The Idols (1928) * Collected Poems Vol 1: London Visions, Narrative Poems, Translations. (1931) * Collected Poems Vol 2: Lyrical Poems. (1931) * The North Star and Other Poems (1941) * The Burning of the Leaves and Other Poems (1944) * The Madness of Merlin (1947) In 1915 Cyril Rootham set “For the Fallen” for chorus and orchestra, first performed in 1919 by the Cambridge University Musical Society conducted by the composer. Edward Elgar set to music three of Binyon’s poems ("The Fourth of August", “To Women”, and “For the Fallen”, published within the collection “The Winnowing Fan”) as The Spirit of England, Op. 80, for tenor or soprano solo, chorus and orchestra (1917). English arts and myth * Dutch Etchers of the Seventeenth Century (1895), Binyon’s first book on painting * John Crone and John Sell Cotman (1897) * William Blake: Being all his Woodcuts Photographically Reproduced in Facsimile (1902) * English Poetry in its relation to painting and the other arts (1918) * Drawings and Engravings of William Blake (1922) * Arthur: A Tragedy (1923) * The Followers of William Blake (1925) * The Engraved Designs of William Blake (1926) * Landscape in English Art and Poetry (1931) * English Watercolours (1933) * Gerard Hopkins and his influence (1939) * Art and freedom. (The Romanes lecture, delivered 25 May 1939). Oxford: The Clarendon press, (1939) Japanese and Persian arts * Painting in the Far East (1908) * Japanese Art (1909) * Flight of the Dragon (1911) * The Court Painters of the Grand Moguls (1921) * Japanese Colour Prints (1923) * The Poems of Nizami (1928) (Translation) * Persian Miniature Painting (1933) * The Spirit of Man in Asian Art (1936) Autobiography * For Dauntless France (1918) (War memoir) Biography * Botticelli (1913) * Akbar (1932) Stage plays * Brief Candles A verse-drama about the decision of Richard III to dispatch his two nephews * “Paris and Oenone”, 1906 * Godstow Nunnery: Play * Boadicea; A Play in eight Scenes * Attila: a Tragedy in Four Acts * Ayuli: a Play in three Acts and an Epilogue * Sophro the Wise: a Play for Children * (Most of the above were written for John Masefield’s theatre). * Charles Villiers Stanford wrote incidental music for Attila in 1907. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laurence_Binyon

Eduardo Germán María Hughes Galeano (Montevideo, 3 de septiembre de 1940-Ib., 13 de abril de 2015) fue un periodista y escritor uruguayo, considerado uno de los escritores más influyentes de la izquierda latinoamericana. Sus libros más conocidos, Las venas abiertas de América Latina (1971) y Memoria del fuego (1986), han sido traducidos a veinte idiomas. Sus trabajos trascienden géneros ortodoxos y combinan documental, ficción, periodismo, análisis político e historia.

Ronald Stuart Thomas (29 March 1913 – 25 September 2000), published as R. S. Thomas, was a Welsh poet and Anglican priest who was noted for his nationalism, spirituality and deep dislike of the anglicisation of Wales. In 1955, John Betjeman, in his introduction to the first collection of Thomas’s poetry to be produced by a major publisher, Song at the Year's Turning, predicted that Thomas would be remembered long after Betjeman himself was forgotten. M. Wynn Thomas said: "He was the Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn of Wales because he was such a troubler of the Welsh conscience. He was one of the major English language and European poets of the 20th century." R. S. Thomas was born in Cardiff, the only child of Thomas Hubert and Margaret (née Davis). The family moved to Holyhead in 1918 because of his father's work in the merchant navy. He was awarded a bursary in 1932 to study at Bangor University, where he read Classics. In 1936, having completed his theological training at St. Michael's College, Llandaff, he was ordained as a priest in the Church in Wales. From 1936 to 1940 he was the curate of Chirk, Denbighshire, where he met his future wife, Mildred (Elsi) Eldridge, an English artist. He subsequently became curate at Tallarn Green, Flintshire. Thomas and Mildred were married in 1940 and remained together until her death in 1991. Their son, Gwydion, was born 29 August 1945. The Thomas family lived on a tiny income and lacked the comforts of modern life, largely by the Thomas's choice. One of the few household amenities the family ever owned, a vacuum cleaner, was rejected because Thomas decided it was too noisy. For twelve years, from 1942 to 1954, Thomas was rector at Manafon, near Welshpool in rural Montgomeryshire. It was during his time at Manafon that he first began to study Welsh and that he published his first three volumes of poetry, The Stones of the Field, An Acre of Land and The Minister. Thomas' poetry achieved a breakthrough with the publication of his fourth book Song at the Year's Turning, in effect a collected edition of his first three volumes, which was critically very well received and opened with Betjeman's famous introduction. His position was also helped by winning the Royal Society of Literature's Heinemann Award. Thomas learnt the Welsh language at age 30, too late in life, he said, to be able to write poetry in it. The 1960s saw him working in a predominantly Welsh speaking community and he later wrote two prose works in Welsh, Neb (English: Nobody), an ironic and revealing autobiography written in the third person, and Blwyddyn yn Llŷn (English: A Year in Llŷn). In 1964 he won the Queen's Gold Medal for Poetry. From 1967 to 1978 he was vicar at St Hywyn's Church (built 1137) in Aberdaron at the western tip of the Llŷn Peninsula. Thomas retired from church ministry in 1978 and he and his wife relocated to Y Rhiw, in "a tiny, unheated cottage in one of the most beautiful parts of Wales, where, however, the temperature sometimes dipped below freezing", according to Theodore Dalrymple. Free from the constraints of the church he was able to become more political and active in the campaigns that were important to him. He became a fierce advocate of Welsh nationalism, although he never supported Plaid Cymru because he believed they did not go far enough in their opposition to England. In 1996 Thomas was nominated for the Nobel Prize for Literature (the winner that year was Seamus Heaney). Thomas died on 25 September 2000, aged 87, at his home at Pentrefelin near Criccieth. He had been ill with heart trouble and had been treated at Gwynnedd hospital until two weeks before he died. After his death an event celebrating his life and poetry was held in Westminster Abbey with readings from Heaney, Andrew Motion, Gillian Clarke and John Burnside. Thomas's ashes are buried close to the door of St. John's Church, Porthmadog, Gwynedd. Beliefs Thomas believed in what he called "the true Wales of my imagination", a Welsh-speaking, aboriginal community that was in tune with the natural world. He viewed western (specifically English) materialism and greed, represented in the poetry by his mythical "Machine", as the destroyers of community. He could tolerate neither the English who bought up Wales and, in his view, stripped it of its wild and essential nature, nor the Welsh whom he saw as all too eager to kowtow to English money and influence. This may help explain why Thomas was an ardent supporter of CND and described himself as a pacifist but also why he supported the Meibion Glyndŵr fire-bombings of English-owned holiday cottages in rural Wales. On this subject he said in 1998, "what is one death against the death of the whole Welsh nation?" He was also active in wildlife preservation and worked with the RSPB and Welsh volunteer organisations for the preservation of the Red Kite. He resigned his RSPB membership over their plans to introduce non-native kites to Wales. Thomas's son, Gwydion, a resident of Thailand, recalls his father's sermons, in which he would "drone on" to absurd lengths about the evil of refrigerators, washing machines, televisions and other modern devices. Thomas preached that they were all part of the temptation of scrambling after gadgets rather than attending to more spiritual needs. "It was the Machine, you see", Gwydion Thomas explained to a biographer. "This to a congregation that didn’t have any of these things and were longing for them." Although he may have taken some ideas to extreme lengths, Theodore Dalrymple wrote, Thomas "was raising a deep and unanswered question: What is life for? Is it simply to consume more and more, and divert ourselves with ever more elaborate entertainments and gadgetry? What will this do to our souls?" Although he was a cleric, he was not always charitable and was known for being awkward and taciturn. Some critics have interpreted photographs of him as indicating he was "formidable, bad-tempered, and apparently humorless." Works Almost all of Thomas's work concerns the Welsh landscape and the Welsh people, themes with both political and spiritual subtext. His views on the position of the Welsh people, as a conquered people are never far below the surface. As a cleric, his religious views are also present in his works. His earlier works focus on the personal stories of his parishioners, the farm labourers and working men and their wives, challenging the cosy view of the traditional pastoral poem with harsh and vivid descriptions of rural lives. The beauty of the landscape, although ever-present, is never suggested as a compensation for the low pay or monotonous conditions of farm work. This direct view of "country life" comes as a challenge to many English writers writing on similar subjects and challenging the more pastoral works of such as contemporary poets as Dylan Thomas. Thomas's later works were of a more metaphysical nature, more experimental in their style and focusing more overtly on his spirituality. Laboratories of the Spirit (1975) gives, in its title, a hint at this development and also reveals Thomas's increasing experiments with scientific metaphor. He described this shift as an investigation into the "adult geometry of the mind".} Fearing that poetry was becoming a dying art, inaccessible to those who most needed it, "he attempted to make spiritually minded poems relevant within, and relevant to, a science-minded, post-industrial world", to represent that world both in form and in content even as he rejected its machinations. Despite his nationalism Thomas could be hard on his fellow countrymen. Often his works read as more of a criticism of Welshness than a celebration. He himself said there is a "lack of love for human beings" in his poetry. Other critics have not been so harsh. Al Alvarez said: "He was wonderful, very pure, very bitter but the bitterness was beautifully and very sparely rendered. He was completely authoritative, a very, very fine poet, completely off on his own, out of the loop but a real individual. It's not about being a major or minor poet. It's about getting a work absolutely right by your own standards and he did that wonderfully well." Thomas's final works commonly sold 20,000 copies in Britain alone. Books * The Stones of the Field (1946) * An Acre of Land (1952) * The Minister (1953) * Song at the Year's Turning (1955) * Poetry for Supper (1958) * Tares, [Corn-weed] (1961) * The Bread of Truth (1963) * Words and the Poet (1964, lecture) * Pietà (1966) * Not That He Brought Flowers (1968) * H'm (1972) * What is a Welshman? (1974) * Laboratories of the Spirit (1975) * Abercuawg (1976, lecture) * The Way of It (1977) * Frequencies (1978) * Between Here and Now (1981) * Ingrowing Thoughts (1985) * Neb (1985) in Welsh, autobiography, written in the third person * Experimenting with an Amen (1986) * Welsh Airs (1987) * The Echoes Return Slow (1988) * Counterpoint (1990) * Blwyddyn yn Llŷn (1990) in Welsh * Pe Medrwn Yr Iaith : ac ysgrifau eraill ed. Tony Brown & Bedwyr L. Jones, essays in Welsh (1990) * Mass for Hard Times (1992) * No Truce with the Furies (1995) * Autobiographies (1997, collection of prose writings) * Residues (2002, posthumously) References Wikipedia - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/R._S._Thomas