San Juan de la Cruz, O.C.D., cuyo nombre de nacimiento era Juan de Yepes Álvarez y su primer nombre como fraile Juan de San Matías, O. Carm. (Fontiveros, Ávila, España, 24 de junio de 1542 – Úbeda, Jaén, 14 de diciembre de 1591) fue un religioso y poeta místico del renacimiento español. Fue reformador de la Orden de los Carmelitas y cofundador de la Orden de Carmelitas Descalzos con Santa Teresa de Jesús. Desde 1952 es el patrono de los poetas en lengua española. Primeros años Nació en 1542 en la localidad abulense de Fontiveros, sita en la amplia paramera delimitada por Madrigal de las Altas Torres, Arévalo y Ávila. Fue hijo de un tejedor toledano de buratos llamado Gonzalo de Yepes y de Catalina Álvarez.3 Tenía dos hermanos mayores llamados Francisco y Luis. El padre de Juan murió cuando tenía cuatro años lo que dejó a la familia en una difícil situación.4 Su hermano Luis murió cuando él tenía seis años, quizá por mala alimentación.5 La madre y los dos hijos restantes, Francisco y el propio Juan, sufren una acuciante pobreza por lo que se ven obligados a trasladarse primero a Arévalo, donde viven durante cuatro años, y en 1551 a Medina del Campo. Estas penalidades pasadas hicieron de Juan un hombre de escasa corpulencia, bastante bajo de estatura, tanto que Santa Teresa de Jesús lo llamaba «mi medio fraile». El incremento de fortuna que les reportó el matrimonio del hermano mayor con Ana Izquierdo consiguió que se establecieran allí definitivamente. Juan, gracias a su condición de pobre de solemnidad, pudo asistir al Colegio de los Niños de la Doctrina,6 privilegio que le obliga a realizar ciertas contraprestaciones, como asistir en el convento, la ayuda a Misa y a los Oficios, el acompañamiento de entierros y la práctica de pedir limosna. La mínima formación recibida en el colegio le capacitó para continuar su formación en el recién creado (1551) colegio de los jesuitas, que le dieron una sólida base en Humanidades. Como alumno externo y a tiempo parcial, debía compaginar sus estudios con un trabajo de asistencia en el Hospital de Nuestra Señora de la Concepción de Medina del Campo, especializado en la curación de enfermedades venéreas contagiosas. Así, pues, entre 1559 y 1563, estudia con los jesuitas; durante los primeros tres años, recibe la formación según la novedosa Ratio Studiorum, en la que el latín era la base de todo el currículo; en el cuarto año, aparte de recibir instrucción retórica, aprende a escribir en latín, a construir versos en este idioma y a traducir a Cicerón, Julio César, Virgilio, Ovidio, Marcial y Horacio. Simultáneamente, vive las nuevas corrientes del humanismo cristiano, con estilo y comportamientos renovados en la pedagogía. A los veintiún años, en 1563, ingresa en el Convento de los Padres Carmelitas de Medina del Campo, de la Orden de los Carmelitas, y adopta el nombre de Fray Juan de san Matías. Tras realizar el noviciado entre 1563 y 1564 en el Convento de Santa Ana, se traslada a Salamanca donde estudiará en el Colegio de San Andrés de los Cármenes entre 1564 y 1567 los tres cursos preceptivos para bachillerarse en artes. Durante el tercer curso, fue nombrado, por sus destrezas dialécticas, prefecto de estudiantes en el colegio de San Andrés. Relación con Santa Teresa de Jesús Su insatisfacción con el modo de vivir la experiencia contemplativa en el Carmelo, le hacen considerar irse a la Cartuja,7 pero en 1567 regresa a Medina del Campo por unos pocos días para ser ordenado presbítero y celebrar su primera misa en presencia de su hermano, el resto de su familia y sus amigos del convento y allí conoce a Teresa de Cepeda y Ahumada, futura santa Teresa de Jesús, que había llegado a la ciudad para fundar una nueva sede de su «Reforma carmelita», los llamados carmelitas descalzos. Teresa convence a Juan y lo une a su causa de reforma de su orden, que tropezó con una gran hostilidad por parte de los carmelitas calzados. Juan regresa a Salamanca e inicia estudios de teología durante el curso 1567-1568, pero sólo termina un curso de cuatro por lo que no obtuvo ni siquiera el grado de bachiller. En agosto abandona Salamanca para acompañar a Teresa en su fundación femenina de Valladolid. El 28 de noviembre de 1568 funda en Duruelo el primer convento de la rama masculina del Carmelo Descalzo siguiendo la «Regla Primitiva» de San Alberto esto es, un establecimiento que propugna el retorno a la práctica original de la orden.8 Durante la ceremonia cambia su nombre por el de fray Juan de la Cruz. En 1570 la fundación se trasladó a Mancera,9 donde Juan desempeñó el cargo de subprior y maestro de novicios. En 1571, después de una breve estancia en Pastrana, donde puso en marcha su noviciado, se establece en Alcalá de Henares como rector del recién fundado Colegio convento de Carmelitas Descalzos de San Cirilo. Juan se convierte en uno de los principales formadores para los nuevos adeptos a esta reforma carmelitana. En 1572 viaja, invitado por Teresa de Jesús, al Convento de la Encarnación en Ávila, donde asumirá las tareas de vicario y confesor de las monjas. Permanecerá aquí hasta finales de 1577, por lo que acompañará a la madre Teresa a la fundación de diversos conventos de descalzas, como el de Segovia. Enfrentamiento entre carmelitas Durante este periodo, en el seno de la Orden del Carmelo se habían agravado los conflictos jurisdiccionales entre los carmelitas calzados y descalzos, debidos a distintos enfoques espirituales de la reforma; por lo demás, el pleito se enmarcaba también en la confrontación entre el poder real y el pontificio por dominar el sector de las órdenes religiosas. Así, en 1575, el Capítulo General de los Carmelitas decidió enviar un visitador de la Orden para suprimir los conventos fundados sin licencia del General y de recluir a la madre Teresa en un convento. Finalmente, en 1580 el Carmelo Descalzo se erige en Provincia exenta y en 1588 es reconocida como Orden. En este contexto es en el que se produce el encarcelamiento de Juan de la Cruz, quien ya en 1575 había sido detenido y encarcelado en Medina del Campo durante unos días por los frailes calzados. La noche del 3 de diciembre de 1577 Juan de la Cruz es nuevamente apresado y trasladado al convento de frailes carmelitas de Toledo, donde es obligado a comparecer ante un tribunal de frailes calzados para retractarse de la Reforma teresiana. Ante su negativa, es recluido en una prisión conventual durante ocho meses. Durante este periodo de reclusión escribe las treinta y una primeras estrofas del Cántico espiritual (en la versión conocida como protocántico), varios romances y el poema de la fonte, y los canta en su estrecha reclusión para consolarse. Tras concienciarse de que su liberación iba a ser difícil, planea detenidamente su fuga y entre el 16 y el 18 de mayo de 1578, con la ayuda de un carcelero, se escapa en medio de la noche y se acoge en el convento de las Madres Carmelitas Descalzas, también en Toledo.11 Para mayor seguridad, las monjas lo envían al Hospital de Santa Cruz, en el que estuvo mes y medio. En 1578 se dirige a Andalucía para recuperarse completamente. Pasa por Almodóvar del Campo, cuna de los místicos San Juan de Ávila y San Juan Bautista de la Concepción, y luego llega como Vicario al convento de El Calvario en Beas de Segura, Jaén. Entabla amistad con Ana de Jesús, tras algunas visitas a la fundación de Beas. En junio de 1579 se establece en la fundación de Baeza donde permanece como Rector del Colegio Mayor hasta 1582, en que marcha para Granada tras ser nombrado Tercer Definidor y Prior de los Mártires de esa ciudad. Realiza numerosos viajes por Andalucía y Portugal, por razones del cargo. En 1588 es elegido Primer Definidor y Tercer Consiliario de la Consulta, la cual le traslada a Segovia. Muerte y canonización Tras un nuevo enfrentamiento doctrinal en 1590, es destituido en 1591 de todos sus cargos, y queda como simple súbdito de la comunidad. Durante su viaje de vuelta a Segovia, cae enfermo en el convento de La Peñuela de La Carolina y es trasladado a Úbeda, donde muere la noche del 13 al 14 de diciembre. Inmediatamente tras su muerte, su cuerpo es despojado y se inician los pleitos entre Úbeda y Segovia por la posesión de sus restos. En 1593, éstos, mutilados, se trasladan clandestinamente a Segovia, donde reposan actualmente. El proceso de beatificación y canonización se inició en 1627 y finalizó en 1630. Fue beatificado en 1675 por Clemente X y canonizado por Benedicto XIII en 1726. Posteriormente, el 24 de agosto de 1926, Pío XI lo proclama Doctor de la Iglesia Universal.12 Obra literaria Influencia La poesía de Juan de Yepes constituye el punto de encuentro de una larga tradición literaria. Su lírica integra tradiciones literarias de distinto origen que, aunadas por el escritor en sus textos, van adquiriendo significados y valores múltiples que sobrepasan aquellos que tenían en su origen. La crítica, desde Dámaso Alonso, ha puesto de relieve la confluencia de tres influjos: por un lado, el bíblico del Cantar de los Cantares, y, por otro, la tradición de la poesía culta italianizante y la tradición de la poesía popular y de cancioneros del Renacimiento español. El influjo de la Biblia es fundamental en su poesía, en tanto actúa como molde y catalizador del resto de lecturas que conforman el bagaje cultural de San Juan. Particularmente, resulta trascendental en el Cántico espiritual, cuyo simbolismo e imágenes tienen su origen en el Cantar de los cantares. Religiosidad y filología La obra de San Juan de la Cruz ha sido, desde siempre, enfocada desde dos perspectivas, la teológica y la literaria, que, en muchas ocasiones, se han presentado mezcladas. Perspectiva religiosa la obra de San Juan sufre una serie de manipulaciones tendentes a integrarla dentro de los límites y convenciones de la ortodoxia. Probablemente, la primera manipulación la realiza el propio autor cuando se decide a redactar los comentarios. Domingo Ynduráin Muñoz La cita hace referencia a los comentarios o paráfrasis explicativa que Juan de la Cruz escribió para su obra más importante, el llamado Cántico espiritual, con una finalidad didáctica como resultado de las dificultades de adaptar la estructura del poema al esquema del itinerario místico (las tres vías y los tres estados correlativos). Esta presencia teológica sobre su obra, y en concreto sobre el Cántico, se ha manifestado también en las constantes manipulaciones de tipo editorial que ha sufrido, en forma de añadidos al título o de epígrafes para determinados grupos de estrofas del poema. Consecuentemente, una importante rama de los estudios sanjuanistas se ha dedicado a demostrar la adecuación de lo escrito por San Juan a la ortodoxia religiosa católica, privilegiando los Comentarios en prosa sobre la poesía. Perspectiva filológica Por otro lado, es frecuente en el estudio literario de su obra que o bien se den saltos continuos a lo teológico, o bien que se estudien de forma conjunta la poesía y los Comentarios doctrinales del propio poeta, con la idea de que estos son necesarios para comprender aquella. Frente a esta vertiente de los estudios sanjuanistas, se encuentra otra que postula que «la necesidad (o posibilidad) de la interpretación religiosa es algo que debe ser argumentado y discutido en cada caso», en tanto que el sentido objetivo de la poesía de San Juan no obliga necesariamente a aceptar un significado religioso. Combinando la antigua simbología del Cantar de los cantares con las fórmulas propias del petrarquismo, produjo una rica literatura mística, que hunde sus raíces en la teología tomista y en los místicos medievales alemanes y flamencos. Su producción refleja una amplia formación religiosa, aunque deja traslucir el influjo del Cancionero tradicional del siglo XVI, sobre todo en el uso del amor profano (las figuras del amante y de la amada) para simbolizar y representar el sentimiento místico del amor divino. La estrofa más empleada en sus poemas es la lira, aunque demuestra igual soltura en el uso del romance octosílabo. San Juan utiliza determinados recursos estilísticos con una profusión y madurez poco frecuentes, dando un nuevo y más profundo sentido a las expresiones paradójicas («cauterio suave»), a las exclamaciones estremecedoras («¡Oh, llama de amor viva!») habituales en los cancioneros. Además, emplea símbolos como la casa o morada, la noche, la luz, la fuente, la oscuridad, la caza de cetrería, la caída, el vuelo, los animales etcétera. Lo que mejor define su poesía es su extraordinaria intensidad expresiva, gracias a la perfecta adecuación y el equilibrio de cada una de sus imágenes. A ello contribuye así mismo su tendencia a abandonar el registro discursivo y eliminar nexos neutros carentes de valor estético para buscar una yuxtaposición constante de elementos poéticos de gran plasticidad en torno a un elemento central, como ha demostrado Dámaso Alonso. Poesía Su obra poética está compuesta por tres poemas considerados mayores: Noche oscura, Cántico espiritual y Llama de amor viva; y un conjunto de poemas habitualmente calificados como menores: cinco glosas, diez romances (nueve de ellos pueden contarse como una sola composición) y dos cantares. La difusión de su obra fue manuscrita, y aún no se han dilucidado todos los problemas textuales que conllevan. En prosa escribió cuatro comentarios a sus poemas mayores: Subida del Monte Carmelo y Noche oscura para el primero de estos poemas, y otros tratados homónimos sobre el Cántico espiritual y Llama de amor viva. Las poesías atribuibles sin lugar a duda a San Juan de la Cruz son las recogidas en el códice de Sanlúcar o manuscrito S, ya que este fue supervisado por el mismo San Juan. El repertorio de sus poemas, según dicha fuente, se restringe a diez composiciones (los tres poemas mayores citados y otras siete composiciones), siempre y cuando los romances que comprenden los textos titulados In principio erat Verbum, que son un total de nueve, sean considerados una única obra. La autenticidad del resto de su obra poética no ha podido aún ser dilucidada por la crítica. Por tradición se acepta generalmente que también son suyos los poemas Sin arrimo y con arrimo y Por toda la hermosura, y las letrillas Del Verbo divino y Olvido de lo criado. Las siete glosas y poemas «menores» cuya autoría no está discutida son los siguientes: (se citan por el primer verso): * Entréme donde no supe * Glosa al Vivo sin vivir en mí * Tras de un amoroso lance * Un pastorcico solo está penado * Que bien sé yo la fonte * En el principio moraba * In principio erat Verbum (nueve romances cuyos primeros versos son: «En aquel amor inmenso», «Una esposa que te ame», «Hágase, pues, dijo el Padre», «Con esta buena esperanza», «En aquellos y otros ruegos», «Ya que el tiempo era llegado», «Entonces llamó un arcángel», «Ya que era llegado el tiempo» y «Encima de las corrientes») Prosa Su obra en prosa pretende ser corolario explicativo, dado el hermetismo simbólico que entre cierta crítica se atribuye su poesía: (las tres primeras han sido editadas juntas reunidas en el volumen Obras espirituales que encaminan a un alma a la unión perfecta con Dios) y Cántico espiritual. * Subida al monte Carmelo (1578-1583) * Noche oscura del alma * Cántico espiritual (1584) * Llama de amor viva (1584) Doctrina Toda su doctrina gira en torno al símbolo de la «noche oscura», imagen que ya era usada en la literatura mística, pero a la que él dio una forma nueva y original. La noche, al borrar los límites de las cosas, le sugiere, en efecto, lo eterno, y de esa manera pasa a simbolizar la negación activa del alma a lo sensible, el absoluto vacío espiritual. El término «noche oscura» lo utiliza san Juan en referencia a las «terribles pruebas que Dios envía al hombre para purificarlo»; ateniéndose a este significado, habla de una noche del sentido y de una noche del espíritu, situadas, respectivamente, al fin de la vía purgativa y de la vía iluminativa, tras las cuales vendría la vía unitiva, aspiración última del alma atormentada por la distancia que la separa de Dios, y realización de su deseo de fusión total con Él. La existencia de estas tres vías se corresponde con las tres potencias clásicas del alma: memoria, entendimiento y voluntad, que en este mismo orden son reducidas a un estado de perfecto silencio. El silencio de la memoria es llamado en la mística esperanza. El silencio del entendimiento se llama fe y el silencio de la voluntad caridad o amor. Estos tres silencios representan a la par un vaciamiento interior y una renuncia de uno mismo que alcanza su máximo grado a través de la virtud de la caridad. De ahí sobrevienen la enorme angustia y la sensación de muerte característica de los místicos, pues unirse a Dios es un perderse previo a sí mismo para después ganarse. Antes de acceder a la experiencia mística de unión con Dios, el alma experimenta una desoladora sensación de soledad y abandono, acompañada de terribles tentaciones que, si consigue vencer, dejan paso a una nueva luz, pues «Dios no deja vacío sin llenar». En una noche oscura, con ansias, en amores inflamada ¡oh dichosa ventura!, salí sin ser notada estando ya mi casa sosegada. Primera estrofa de Noche oscura. San Juan de la Cruz Originalidad San Juan de la Cruz ofrece una radical originalidad en el misticismo consistente en el concepto de noche oscura espiritual. Desde los inicios históricos de la vida retirada eremítica, los buscadores renunciaban a los bienes y placeres mundanos sometiéndose a ayunos y otras asperezas, con el objeto de vaciar sus deseos del mundo y llenarlo de bienes más elevados. San Juan de la Cruz aclara que esta es solamente la primera etapa, ya que tras ella viene la citada noche espiritual, en que el buscador, ya desapegado de los consuelos y placeres mundanos, perderá también el apoyo de su paz, de sus suavidades interiores, entrando en la más "espantable" noche a la que sí sigue la perfecta contemplación. Una de las partes más originales y más profundas de la doctrina de San Juan de la Cruz, con la que más ha hecho progresar la teología mística y merecido el título de Doctor, es la que se refiere a lo que él llama la noche pasiva del espíritu. Réginald Garrigou-Lagrange Un campo sin explorar. Juan de la Cruz percibe la urgencia y la dificultad, y se decide a explorar todo ese campo de la noche, en especial las zonas más arduas donde ningún escritor había logrado penetrar. José Vicente Rodríguez y Federico Ruiz Monte de perfección En su célebre dibujo del Monte de perfección la recta senda del ascenso aparece flanqueada por dos caminos laterales sin salida. El de la derecha, el camino mundano, señala sus peligros: poseer, gozo, saber, consuelo, descanso. Asimismo el de la izquierda marca también los peligros de un camino espiritual: gloria, gozo, saber, consuelo, descanso. Sorprende especialmente la leyenda de los escalones del camino central, el correcto, en los cuales se lee: Nada, nada, nada, nada, nada Como nota de este gráfico el autor escribe: Da avisos y doctrina, así a los principiantes como a los aprovechados, muy provechosa para que sepan desembarazarse de todo lo temporal y no embarazarse con lo espiritual, y queden en la suma desnudez y libertad de espíritu, la cual se requiere para la divina unión. Algunas de sus frases breves resumen bien su doctrina, como: «Niega tus deseos, y hallarás lo que desea tu corazón» y «El amor no consiste en sentir grandes cosas, sino en tener grande desnudez, y padecer por el Amado». Referencias Wikipedia - http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/San_Juan_de_la_Cruz

.jpg)

La poésie occupe une place dans la littérature aussi réduite que la place que l'on accorde à ses textes, et nous les homos ⚣ sommes presque aussi marginalisés qu'elle malgré notre étiquette d'icône gay, alors imaginez, la poésie homosexuelle ! De la même façon que j'ai pu regarder des films issus du cinéma gay, j'ai voulu écouter de la poésie gay/queer sur le web... Je n'eus que quelques malheureux textes de la trilogie infernale Verlaine/Rimbaud, et de Jean Genet. Le 24 avr. 2017 je créais donc ma chaîne afin de disposer d'un espace où je puisse dire la poésie que je voulais sans qu'elle soit censurée pour pornographie, car c'est bien connu, seuls les Grands peuvent être excusés d'avoir écrit. L'éternelle formalité vaine d'une pornographie nécessairement péjorative et indigne des Lettres qui la forme. Écrire sur elle ou en partant d'elle est une gémonies par indécence et bien c'est de ces corps putrides du sexe-mort que je veux partir. C'est pour cela que je me revendique "poète queer", non pas pour préjuger de la qualité de mes écrits mais au nom de la rareté de ceux qui s'affichent comme tel : queer.

Lisímaco Chavarría Palma (San Ramón, Costa Rica, 10 de mayo de 1878 – 27 de agosto de 1913) fue un escritor y poeta costarricense. De orígenes humildes y escasa formación académica, en su corta vida logró posicionarse como uno de los poetas más importantes de la literatura costarricense, representante del modernismo en Costa Rica pero desarrollador de un estilo propio, que lo llevó a considerársele un renovador de la poesía lírica nacional. Es Benemérito de las Letras Patrias desde 1994. Biografía Poeta nacido en San Ramón de Alajuela (Costa Rica) el 10 de mayo de 1878, en un modesto hogar que tenía su asiento cerca del cementerio de la ciudad. Hijo de Eduardo Chavarría y Teresa Palma. Cursó la enseñanza primaria en su ciudad natal, pero tuvo que abandonar los estudios para dedicarse a la agricultura como medio de subsistencia. En su juventud se dedicó a la pintura y a la escultura en el taller del maestro Manuel Rodríguez Cruz , como medio para ganarse la vida en una época hostil a las manifestaciones literarias. También trabajó como peón agrícola en San Marcos de Tarrazú. Su deseo por arte lo motivó a viajar a San José, donde trabajó para Pedro Pérez Molina por un corto periodo, para luego trasladarse a Cartago, donde laboró de nuevo como imaginero. Durante esta época aprendió el oficio de relojero, y después fue maestro en una escuela de Tabarcia de Mora y en Santa Rita de Nicoya. En 1901 dirigió la escuela de Santa Ana. Luego de su divorcio en 1905, residió nuevamente en San Ramón. Laboró en sus últimos diez años en la Biblioteca Nacional, gracias a su amigo el poeta Justo A. Facio. La consecución de este empleo le permitió solventar su ingreso económico, permitiéndole cultivar su cultura literaria. En 1907, fue redactor del diario La Prensa Libre. En medio de sus labores no dejaba de escribir poesía. Publicó su primer poemario, Orquídeas, en 1904, y unos meses después, el segundo, Nómadas, con un prólogo de Antonio Zambrana. Sus primeros escritos, debido a su timidez, los esconde bajo el nombre de Rosa Corrales de Chavarría, su primera esposa. El triunfo del poema El arte, que obtuvo el primer premio en el festival Fiesta del Arte (1905) precipitó una disputa entre Lisímaco y su esposa por la autoría del mismo, lo que precipitó el divorcio. Poco después, se comprobó que Chavarría era el autor, y al año siguiente, dos poemas suyos, Al pensador y Al trabajo, obtuvieron el primer premio de la Fiesta del Arte de ese año. Entre 1905 y hasta su muerte, se dedicará a mejorar su producción poética, publicando sus trabajos en la revista Páginas Ilustradas. También incursionó en el ensayo. En 1904, escribió varios ensayos sobre las artes plásticas, donde destacaba la labor pedagógica de Tomás Povedano en este campo. En 1907, publicó Añoranzas líricas, e inició sus estudios de pintura en la Escuela de Bellas Artes que dirigió Tomás Povedano. Se le han atribuido varias obras pictóricas de gran calidad cuya autoría no ha podido ser comprobada. En 1908 publicó su libro Desde los Andes, que lo dio a conocer como poeta en Hispanoamérica. Esto permitió que revistas extranjeras comenzaran a publicar sus poemas: France Amerique (París, Francia), Cuba (La Habana, Cuba), América (Nueva York, EEUU), Expectación literaria (Alicante, España), El Comercio (Quito, Ecuador), El diario de la tarde (Mazatlán, México). También lo puso en contacto con prestigiosos literatos latinoamericanos. Un poema suyo, El árbol del sendero, ganó un certamen de poesía latinoamericana organizado por la revista neoyorquina América, mientras que en México se le declaró segundo poeta de Hispanoamérica, luego de Rubén Darío. En 1909, por su Poema del agua, obtuvo el galardón La Flor Natural en los juegos florales de Costa Rica y dos Menciones Honoríficas por Palabras de la momia y Los carboneros. Este premio nacional, marca la consagración de Lisímaco como poeta de una época y lo lanza internacionalmente mediante el reconocimiento de figuras tan prestigiosas como Rubén Darío, Manuel Magallanes Moure, Manuel Baldomero Ugarte, Ismael Urdaneta, José Enrique Rodó, quienes se convirtieron en sus amigos epistolares. Lisímaco, afectado de tuberculosis, fallece en casa de su madre en San Ramón, la tarde del 27 de agosto de 1913. Fue declarado Benemérito de las Letras Patrias el 27 de abril de 1994 por la Asamblea Legislativa de Costa Rica. References Wikipedia—https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lisímaco_Chavarría’’

Just tryna get my poems out there and let people know they're not alone <3 follow me and I'll follow back . I write about a range of things from recovery, to depression, to happiness and all in between. Hopefully some can relate and I have the honor of helping someone get through a rough time.

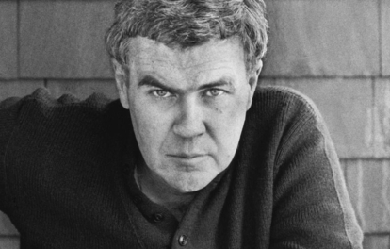

Raymond Clevie Carver, Jr. (May 25, 1938– August 2, 1988) was an American short-story writer and poet. Carver contributed to the revitalization of the American short story in literature during the 1980s. Early life Carver was born in Clatskanie, Oregon, a mill town on the Columbia River, and grew up in Yakima, Washington, the son of Ella Beatrice (née Casey) and Clevie Raymond Carver. His father, a sawmill worker from Arkansas, was a fisherman and heavy drinker. Carver’s mother worked on and off as a waitress and a retail clerk. His one brother, James Franklin Carver, was born in 1943. Carver was educated at local schools in Yakima, Washington. In his spare time, he read mostly novels by Mickey Spillane or publications such as Sports Afield and Outdoor Life, and hunted and fished with friends and family. After graduating from Yakima High School in 1956, Carver worked with his father at a sawmill in California. In June 1957, at age 19, he married 16-year-old Maryann Burk, who had just graduated from a private Episcopal school for girls. Their daughter, Christine La Rae, was born in December 1957. Their second child, a boy named Vance Lindsay, was born a year later. He supported his family by working as a delivery man, janitor, library assistant, and sawmill laborer. During their marriage, Maryann also supported the family by working as an administrative assistant and a high school English teacher, salesperson, and waitress. Writing career Carver became interested in writing in Paradise, California, where he had moved with his family to be close to his mother-in-law. While attending Chico State College, he enrolled in a creative writing course taught by the novelist John Gardner, a recent doctoral graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop who became a mentor and had a major influence on Carver’s life and career. Carver’s first published story, “The Furious Seasons”, appeared in 1961. More florid than his later work, the story strongly bore the influence of William Faulkner. “Furious Seasons” was later used as a title for a collection of stories published by Capra Press, and is now in the recent collection, No Heroics, Please and Call If You Need Me. It is a common misconception that Carver was influenced by Ernest Hemingway, as both writers exhibit a similar economical and plain prose style. In his essay “On Influence”, however, Carver states clearly that, while he was an admirer of Hemingway’s fiction, he never saw him as an influence, citing instead the work of Lawrence Durrell. Carver continued his studies under the short-story writer Richard Cortez Day (like Gardner, a recent PhD alumnus of the Iowa program) at Humboldt State College in Arcata, California. After electing not to take the foreign language courses required by the English program, he received his B.A. in general studies in 1963. During this period he was first published and served as editor for Toyon, the university’s literary magazine, in which he published several of his own pieces under his own name as well as the pseudonym John Vale. With his B– average—exacerbated by his penchant to forsake coursework for literary endeavors—ballasted by a sterling recommendation from Day, Carver was accepted into the Iowa Writers’ Workshop on a $1,000 fellowship for the 1963–1964 academic year. Homesick for California and unable to fully acclimate to the program’s upper middle class milieu, he only completed 12 credits out of the 30 required for a M.A. degree or 60 for the M.F.A. degree. Although he was awarded a fellowship for a second year of study from program director Paul Engle after Maryann Carver personally interceded and compared her husband’s plight to Tennessee Williams’ deleterious experience in the program three decades earlier, Carver decided to leave the program at the end of the semester. Maryann (who postponed completing her education to support her husband’s educational and literary endeavors) eventually graduated from San Jose State College in 1970 and taught English at Los Altos High School until 1977, when she enrolled in the University of California, Santa Barbara’s doctoral program in English. In the mid-1960s, Carver and his family resided in Sacramento, California, where he briefly worked at a bookstore before taking a position as a night custodian at Mercy Hospital. He did all of the janitorial work in the first hour and then wrote at the hospital through the rest of the night. He audited classes at what was then Sacramento State College, including workshops with poet Dennis Schmitz. Carver and Schmitz soon became friends, and Carver wrote and published his first book of poems, Near Klamath, under Schmitz’s guidance. With the appearance of Will You Please Be Quiet, Please? in Martha Foley’s annual Best American Short Stories anthology and the impending publication of Near Klamath by the English Club of Sacramento State College, 1967 was a landmark year for Carver. He briefly enrolled in the library science graduate program at the University of Iowa that summer but returned to California following the death of his father. Shortly thereafter, the Carvers relocated to Palo Alto, California, so he could take his first white-collar job at Science Research Associates (a subsidiary of IBM), where he worked intermittently as a textbook editor and public relations director through 1970. Following a 1968 sojourn to Israel, the Carvers relocated to San Jose, California; as Maryann finished her undergraduate degree, he continued his graduate studies in library science at San Jose State through the end of 1969 before failing once again to take a degree. Nevertheless, he established vital literary connections with Gordon Lish and the poet/publisher George Hitchcock during this period. After the publication of “Neighbors” in the June 1971 issue of Esquire at the instigation of Lish (by now ensconced as the magazine’s fiction editor), Carver began to teach at the University of California, Santa Cruz at the behest of provost James B. Hall (an Iowa alumnus and early mentor to Ken Kesey at the University of Oregon), commuting from his new home in Sunnyvale, California. Following a succession of failed applications, he received a $4,000 Stegner Fellowship to study in the prestigious non-degree graduate creative writing program at Stanford University during the 1972–1973 term, where he cultivated friendships with Kesey-era luminaries Ed McClanahan and Gurney Norman in addition to contemporaneous fellows Chuck Kinder, Max Crawford, and William Kittredge. The fellowship enabled the Carvers to buy a house in Cupertino, California. He took on another teaching job at the University of California, Berkeley that year and briefly rented a pied-à-terre in the city; this development was largely precipitated by his instigation of an extramarital affair with Diane Cecily, a University of Montana administrator and mutual friend of Kittredge who would subsequently marry Kinder. During his years of working at miscellaneous jobs, rearing children, and trying to write, Carver started abusing alcohol. By his own admission, he essentially gave up writing and took to full-time drinking. In the fall semester of 1973, Carver was a visiting lecturer in the Iowa Writers’ Workshop with John Cheever, but Carver stated that they did less teaching than drinking and almost no writing. With the assistance of Kinder and Kittredge, he attempted to simultaneously commute to California and maintain his lectureship at Santa Cruz; after missing all but a handful of classes due to the inherent logistical hurdles of this arrangement (including various alcohol-related illnesses), Hall gently enjoined Carver to resign his position. The next year, after leaving Iowa City, Carver went to a treatment center to attempt to overcome his alcoholism, but continued drinking for three years. His first short story collection, Will You Please Be Quiet, Please?, was published in 1976. The collection itself was shortlisted for the National Book Award, though it sold fewer than 5,000 copies that year. After being hospitalized three times (between June 1976 and February or March 1977), Carver began his “second life” and stopped drinking on June 2, 1977, with the help of Alcoholics Anonymous. While he continued to regularly smoke marijuana and later experimented with cocaine at the behest of Jay McInerney during a 1980 visit to New York City, Carver believed he would have died of alcoholism at the age of 40 had he not overcome his drinking. Carver was nominated again in 1984 for his third major-press collection, Cathedral, the volume generally perceived as his best. Included in the collection are the award-winning stories “A Small, Good Thing”, and “Where I’m Calling From”. John Updike selected the latter for inclusion in The Best American Short Stories of the Century. For his part, Carver saw Cathedral as a watershed in his career, in its shift towards a more optimistic and confidently poetic style. Personal life and death Decline of first marriage The following excerpt from Scott Driscoll’s review of Maryann Burk Carver’s 2006 memoir describes the decline of Maryann and Raymond’s marriage. The fall began with Ray’s trip to Missoula, Mont., in '72 to fish with friend and literary helpmate Bill Kittredge. That summer Ray fell in love with Diane Cecily, an editor at the University of Montana, whom he met at Kittredge’s birthday party. “That’s when the serious drinking began. It broke my heart and hurt the children. It changed everything.” “By fall of '74", writes Carver, “he was more dead than alive. I had to drop out of the Ph.D. program so I could get him cleaned up and drive him to his classes”. Over the next several years, Maryann’s husband physically abused her. Friends urged her to leave Raymond. “But I couldn’t. I really wanted to hang in there for the long haul. I thought I could outlast the drinking. I’d do anything it took. I loved Ray, first, last and always.” Carver describes, without a trace of rancor, what finally put her over the edge. In the fall of '78, with a new teaching position at the University of Texas at El Paso, Ray started seeing Tess Gallagher, a writer from Port Angeles, who would become his muse and wife near the end of his life. “It was like a contretemps. He tried to call me to talk about where we were. I missed the calls. He knew he was about to invite Tess to Thanksgiving.” So he wrote a letter instead. “I thought, I’ve gone through all those years fighting to keep it all balanced. Here it was, coming at me again, the same thing. I had to get on with my own life. But I never fell out of love with him.” Second marriage Carver met the poet Tess Gallagher at a writers’ conference in Dallas, Texas, in November 1977. Beginning in January, 1979, Carver and Gallagher lived together in El Paso, Texas; in a borrowed cabin near Port Angeles, Washington; and in Tucson, Arizona. In 1980, the two moved to Syracuse, New York, where Gallagher had been appointed the coordinator of the creative writing program at Syracuse University; Carver taught as a professor in the English department. He and Gallagher jointly purchased a house in Syracuse, at 832 Maryland Avenue. In ensuing years, the house became so popular that the couple had to hang a sign outside that read “Writers At Work” in order to be left alone. In 1982, Carver and first wife, Maryann, were divorced. He married Gallagher in 1988 in Reno, Nevada. Six weeks later, on August 2, 1988, Carver died in Port Angeles, Washington, from lung cancer at the age of 50. In the same year, he was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters. In December 2006, Gallagher published an essay in The Sun magazine, titled “Instead of Dying”, about alcoholism and Carver’s having maintained his sobriety. The essay is an adaptation of a talk she initially delivered at the Welsh Academy’s Academi Intoxication Conference in 2006. The first lines read: “Instead of dying from alcohol, Raymond Carver chose to live. I would meet him five months after this choice, so I never knew the Ray who drank, except by report and through the characters and actions of his stories and poems.” Death On August 2, 1988, Carver died from lung cancer at the age of 50. He is buried at Ocean View Cemetery in Port Angeles, Washington. The inscription on his tombstone reads: LATE FRAGMENT And did you get what you wanted from this life, even so? I did. And what did you want? To call myself beloved, to feel myself beloved on the earth. His poem “Gravy” is also inscribed. As Carver’s will directed, Tess Gallagher assumed the management of his literary estate. Memorials In Carver’s birth town of Clatskanie, Oregon, a memorial park and statue were constructed in the late 2000s spearheaded by the local Friends of the Library, using mostly local donations. Tess Gallagher was present at the dedication. It is located in the old town on the corner of Lillich and Nehalem Streets, across from the library. A block away, the building where Raymond Carver was born still stands. There is a plaque of Carver in the foyer. Legacy and posthumous publications The novelist Chuck Kinder published Honeymooners: A Cautionary Tale (2001), a roman à clef about his friendship with Carver in the 1970s. Carver’s high school sweetheart and first wife, Maryann Burk Carver, wrote a memoir of her years with Carver, What it Used to be Like: A Portrait of My Marriage to Raymond Carver (2006). The New York Times Book Review and San Francisco Chronicle named Carol Sklenicka’s unauthorized biography, Raymond Carver: A Writer’s Life (2009), published by Scribner, one of the Best Ten Books of that year; and the San Francisco Chronicle deemed it: “exhaustively researched and definitive biography”. Carver’s widow, Tess Gallagher, refused to engage with Sklenica. His final (incomplete) collection of seven stories, titled Elephant in Britain (included in “Where I’m Calling From”) was composed in the five years before his death. The nature of these stories, especially “Errand”, have led to some speculation that Carver was preparing to write a novel. Only one piece of this work has survived– the fragment “The Augustine Notebooks”, first printed in No Heroics, Please. Tess Gallagher published five Carver stories posthumously in Call If You Need Me; one of the stories ("Kindling") won an O. Henry Award in 1999. In his lifetime Carver won five O. Henry Awards; these winning stories were “Are These Actual Miles” (originally titled “What is it?”) (1972), “Put Yourself in My Shoes” (1974), “Are You A Doctor?” (1975), “A Small, Good Thing” (1983), and “Errand” (1988). Tess Gallagher fought with Knopf for permission to republish the stories in What We Talk About When We Talk About Love as they were originally written by Carver, as opposed to the heavily edited and altered versions that appeared in 1981 under the editorship of Gordon Lish. The book, entitled Beginners, was released in hardback on October 1, 2009 in Great Britain, followed by its U.S. publication in the Library of America edition that collected all of Carver’s short fiction in a single volume. Literary characteristics Carver’s career was dedicated to short stories and poetry. He described himself as “inclined toward brevity and intensity” and “hooked on writing short stories” (in the foreword of Where I’m Calling From, a collection published in 1988 and a recipient of an honorable mention in the 2006 New York Times article citing the best works of fiction of the previous 25 years). Another stated reason for his brevity was "that the story [or poem] can be written and read in one sitting." This was not simply a preference but, particularly at the beginning of his career, a practical consideration as he juggled writing with work. His subject matter was often focused on blue-collar experience, and was clearly reflective of his own life. Characteristics of minimalism are generally seen as one of the hallmarks of Carver’s work, although, as reviewer David Wiegand notes: Carver never thought of himself as a minimalist or in any category, for that matter. “He rejected categories generally,” Sklenicka says. “I don’t think he had an abstract mind at all. He just wasn’t built that way, which is why he’s so good at picking the right details that will stand for many things.” Carver’s editor at Esquire, Gordon Lish, was instrumental in shaping Carver’s prose in this direction– where his earlier tutor John Gardner had advised Carver to use fifteen words instead of twenty-five, Lish instructed Carver to use five in place of fifteen. Objecting to the “surgical amputation and transplantation” of Lish’s heavy editing, Carver eventually broke with him. During this time, Carver also submitted poetry to James Dickey, then poetry editor of Esquire. Carver’s style has also been described as dirty realism, which connected him with a group of writers in the 1970s and 1980s that included Richard Ford and Tobias Wolff (two writers with whom Carver was closely acquainted), as well as others such as Ann Beattie, Frederick Barthelme, and Jayne Anne Phillips. With the exception of Beattie, who wrote about upper-middle-class people, these were writers who focused on sadness and loss in the everyday lives of ordinary people—often lower-middle class or isolated and marginalized people. Works Fiction Collections * Will You Please Be Quiet, Please? (first published 1976) * Furious Seasons and other stories (1977) * What We Talk About When We Talk About Love (1981) * Cathedral (1983) * Elephant (1988)– this title only published in Great Britain; included as a section of Where I’m Calling From: New & Selected Stories in the U.S. Compilations * Where I’m Calling From: New & Selected Stories (1988) * Short Cuts: Selected Stories (1993)– published to accompany the Robert Altman film Short Cuts * Collected Stories (2009)– complete short fiction including Beginners Poetry Collections * Near Klamath (1968) * Winter Insomnia (1970) * At Night The Salmon Move (1976) * Fires (1983) * Where Water Comes Together With Other Water (1985) * Ultramarine (1986) * A New Path To The Waterfall (1989) * Gravy (Unknown year) Compilations * In a Marine Light: Selected Poems (1988) * All of Us: The Collected Poems (1996) Screenplays * Dostoevsky (1985, with Tess Gallagher) Films and theatre adaptations * Short Cuts directed by Robert Altman (1993), based on nine Carver short stories and a poem * Everything Goes directed by Andrew Kotatko (2004), starring Hugo Weaving and Abbie Cornish, based on Carver’s short story “Why Don’t You Dance?” * Whoever Was Using This Bed, also directed by Andrew Kotatko (2016), starring Jean-Marc Barr, Radha Mitchell and Jane Birkin, based on Carver’s short story of the same name * Jindabyne directed by Ray Lawrence (2006), based on Carver’s short story “So Much Water So Close to Home” * “After The Denim” directed by Gregory D. Goyins (2010) starring Tom Bower and Karen Landry, based on Carver’s short story “If It Please You” * Everything Must Go directed by Dan Rush (2010), and starring Will Ferrell, based on Carver’s short story “Why Don’t You Dance?” * Carver a production directed by William Gaskill at London’s Arcola Theatre in 1995, adapted from five Carver short stories including “What’s In Alaska?” “Put Yourself in My Shoes” and “Intimacy” * Studentova žena (Croatian) directed by Goran Kovač, based on “The Student’s Wife” * Carousel (Croatian) directed by Toma Zidić, inspired by “Ashtray” * Men Who Don’t Work directed by Alexander Atkins and Andrew Franks, based on “What Do You Do in San Francisco?” * Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance), directed by Alejandro G. Iñárritu, depicts the mounting of a Broadway production of “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love” as its central storyline. The film’s main character, Riggan Thomson, attributes his choice of acting as a profession to a complimentary note he once received from Raymond Carver written on a cocktail napkin. The film also preludes with Carver’s poem “Late Fragment.” In February 2015, Birdman won four Oscars, including the Academy Award for Best Picture. Musical adaptions * Everything’s Turning to White is a folk rock track written and performed by Paul Kelly on the album So Much Water So Close to Home (1989), which was based on Carver’s short story of the same name. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raymond_Carver

Geoffrey Chaucer (c. 1343 – 25 October 1400), known as the Father of English literature, is widely considered the greatest English poet of the Middle Ages and was the first poet to have been buried in Poet's Corner of Westminster Abbey. While he achieved fame during his lifetime as an author, philosopher, alchemist and astronomer, composing a scientific treatise on the astrolabe for his ten year-old son Lewis, Chaucer also maintained an active career in the civil service as a bureaucrat, courtier and diplomat. Among his many works, which include The Book of the Duchess, the House of Fame, the Legend of Good Women and Troilus and Criseyde, he is best known today for The Canterbury Tales. Chaucer is a crucial figure in developing the legitimacy of the vernacular, Middle English, at a time when the dominant literary languages in England were French and Latin. Geoffrey Chaucer was born in London sometime around 1343, though the precise date and location of his birth remain unknown. His father and grandfather were both London vintners; several previous generations had been merchants in Ipswich. (His family name derives from the French chausseur, meaning "shoemaker".)[1] In 1324 John Chaucer, Geoffrey's father, was kidnapped by an aunt in the hope of marrying the twelve-year-old boy to her daughter in an attempt to keep property in Ipswich. The aunt was imprisoned and the £250 fine levied suggests that the family was financially secure—bourgeois, if not elite.[2] John Chaucer married Agnes Copton, who, in 1349, inherited properties including 24 shops in London from her uncle, Hamo de Copton, who is described in a will dated 3 April 1354 and listed in the City Hustings Roll as "moneyer"; he was said to be moneyer at the Tower of London. In the City Hustings Roll 110, 5, Ric II, dated June 1380, Geoffrey Chaucer refers to himself as me Galfridum Chaucer, filium Johannis Chaucer, Vinetarii, Londonie' . While records concerning the lives of his contemporary poets, William Langland and the Pearl Poet are practically non-existent, since Chaucer was a public servant, his official life is very well documented, with nearly five hundred written items testifying to his career. The first of the "Chaucer Life Records" appears in 1357, in the household accounts of Elizabeth de Burgh, the Countess of Ulster, when he became the noblewoman's page through his father's connections.[3] She was married to Lionel, Duke of Clarence, the second surviving son of the king, Edward III, and the position brought the teenage Chaucer into the close court circle, where he was to remain for the rest of his life. He also worked as a courtier, a diplomat, and a civil servant, as well as working for the king, collecting and inventorying scrap metal. In 1359, in the early stages of the Hundred Years' War, Edward III invaded France and Chaucer travelled with Lionel of Antwerp, 1st Duke of Clarence, Elizabeth's husband, as part of the English army. In 1360, he was captured during the siege of Rheims. Edward paid £16 for his ransom, a considerable sum, and Chaucer was released. After this, Chaucer's life is uncertain, but he seems to have travelled in France, Spain, and Flanders, possibly as a messenger and perhaps even going on a pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela. Around 1366, Chaucer married Philippa (de) Roet. She was a lady-in-waiting to Edward III's queen, Philippa of Hainault, and a sister of Katherine Swynford, who later (ca. 1396) became the third wife of John of Gaunt. It is uncertain how many children Chaucer and Philippa had, but three or four are most commonly cited. His son, Thomas Chaucer, had an illustrious career, as chief butler to four kings, envoy to France, and Speaker of the House of Commons. Thomas's daughter, Alice, married the Duke of Suffolk. Thomas's great-grandson (Geoffrey's great-great-grandson), John de la Pole, Earl of Lincoln, was the heir to the throne designated by Richard III before he was deposed. Geoffrey's other children probably included Elizabeth Chaucy, a nun at Barking Abbey. Agnes, an attendant at Henry IV's coronation; and another son, Lewis Chaucer. Chaucer’s “Treatise on the Astrolabe” was written for Lewis. Chaucer probably studied law in the Inner Temple (an Inn of Court) at this time. He became a member of the royal court of Edward III as a varlet de chambre, yeoman, or esquire on 20 June 1367, a position which could entail a wide variety of tasks. His wife also received a pension for court employment. He travelled abroad many times, at least some of them in his role as a valet. In 1368, he may have attended the wedding of Lionel of Antwerp to Violante Visconti, daughter of Galeazzo II Visconti, in Milan. Two other literary stars of the era were in attendance: Jean Froissart and Petrarch. Around this time, Chaucer is believed to have written The Book of the Duchess in honour of Blanche of Lancaster, the late wife of John of Gaunt, who died in 1369. Chaucer travelled to Picardy the next year as part of a military expedition; in 1373 he visited Genoa and Florence. Numerous scholars such as Skeat, Boitani, and Rowland suggested that, on this Italian trip, he came into contact with Petrarch or Boccaccio. They introduced him to medieval Italian poetry, the forms and stories of which he would use later. The purposes of a voyage in 1377 are mysterious, as details within the historical record conflict. Later documents suggest it was a mission, along with Jean Froissart, to arrange a marriage between the future King Richard II and a French princess, thereby ending the Hundred Years War. If this was the purpose of their trip, they seem to have been unsuccessful, as no wedding occurred. In 1378, Richard II sent Chaucer as an envoy (secret dispatch) to the Visconti and to Sir John Hawkwood, English condottiere (mercenary leader) in Milan. It has been speculated that it was Hawkwood on whom Chaucer based his character the Knight in the Canterbury Tales, for a description matches that of a fourteenth-century condottiere. A possible indication that his career as a writer was appreciated came when Edward III granted Chaucer "a gallon of wine daily for the rest of his life" for some unspecified task. This was an unusual grant, but given on a day of celebration, St George's Day, 1374, when artistic endeavours were traditionally rewarded, it is assumed to have been another early poetic work. It is not known which, if any, of Chaucer's extant works prompted the reward, but the suggestion of him as poet to a king places him as a precursor to later poets laureate. Chaucer continued to collect the liquid stipend until Richard II came to power, after which it was converted to a monetary grant on 18 April 1378. Chaucer obtained the very substantial job of Comptroller of the Customs for the port of London, which he began on 8 June 1374.[10] He must have been suited for the role as he continued in it for twelve years, a long time in such a post at that time. His life goes undocumented for much of the next ten years, but it is believed that he wrote (or began) most of his famous works during this period. He was mentioned in law papers of 4 May 1380, involved in the raptus of Cecilia Chaumpaigne. What raptus means is unclear, but the incident seems to have been resolved quickly and did not leave a stain on Chaucer's reputation. It is not known if Chaucer was in the city of London at the time of the Peasants' Revolt, but if he was, he would have seen its leaders pass almost directly under his apartment window at Aldgate. While still working as comptroller, Chaucer appears to have moved to Kent, being appointed as one of the commissioners of peace for Kent, at a time when French invasion was a possibility. He is thought to have started work on The Canterbury Tales in the early 1380s. He also became a Member of Parliament for Kent in 1386. There is no further reference after this date to Philippa, Chaucer's wife, and she is presumed to have died in 1387. He survived the political upheavals caused by the Lords Appellants, despite the fact that Chaucer knew some of the men executed over the affair quite well. On 12 July 1389, Chaucer was appointed the clerk of the king's works, a sort of foreman organising most of the king's building projects.[12] No major works were begun during his tenure, but he did conduct repairs on Westminster Palace, St. George's Chapel, Windsor, continue building the wharf at the Tower of London, and build the stands for a tournament held in 1390. It may have been a difficult job, but it paid well: two shillings a day, more than three times his salary as a comptroller. Chaucer was also appointed keeper of the lodge at the King’s park in Feckenham, which was a largely honorary appointment.[13] In September 1390, records say that he was robbed, and possibly injured, while conducting the business, and it was shortly after, on 17 June 1391, that he stopped working in this capacity. Almost immediately, on 22 June, he began as Deputy Forester in the royal forest of North Petherton, Somerset. This was no sinecure, with maintenance an important part of the job, although there were many opportunities to derive profit. He was granted an annual pension of twenty pounds by Richard II in 1394.[14] It is believed that Chaucer stopped work on the Canterbury Tales sometime towards the end of this decade. Not long after the overthrow of his patron, Richard II, in 1399, Chaucer's name fades from the historical record. The last few records of his life show his pension renewed by the new king, and his taking of a lease on a residence within the close of Westminster Abbey on 24 December 1399.[15] Although Henry IV renewed the grants assigned to Chaucer by Richard, Chaucer's own The Complaint of Chaucer to his Purse hints that the grants might not have been paid. The last mention of Chaucer is on 5 June 1400, when some monies owed to him were paid. He is believed to have died of unknown causes on 25 October 1400, but there is no firm evidence for this date, as it comes from the engraving on his tomb, erected more than one hundred years after his death. There is some speculation—most recently in Terry Jones' book Who Murdered Chaucer? : A Medieval Mystery—that he was murdered by enemies of Richard II or even on the orders of his successor Henry IV, but the case is entirely circumstantial. Chaucer was buried in Westminster Abbey in London, as was his right owing to his status as a tenant of the Abbey's close. In 1556, his remains were transferred to a more ornate tomb, making Chaucer the first writer interred in the area now known as Poets' Corner. Work Chaucer's first major work, The Book of the Duchess, was an elegy for Blanche of Lancaster (who died in 1369). It is possible that this work was commissioned by her husband John of Gaunt, as he granted Chaucer a £10 annuity on 13 June 1374. This would seem to place the writing of The Book of the Duchess between the years 1369 and 1374. Two other early works by Chaucer were Anelida and Arcite and The House of Fame. Chaucer wrote many of his major works in a prolific period when he held the job of customs comptroller for London (1374 to 1386). His Parlement of Foules, The Legend of Good Women and Troilus and Criseyde all date from this time. Also it is believed that he started work on The Canterbury Tales in the early 1380s. Chaucer is best known as the writer of The Canterbury Tales, which is a collection of stories told by fictional pilgrims on the road to the cathedral at Canterbury; these tales would help to shape English literature. The Canterbury Tales contrasts with other literature of the period in the naturalism of its narrative, the variety of stories the pilgrims tell and the varied characters who are engaged in the pilgrimage. Many of the stories narrated by the pilgrims seem to fit their individual characters and social standing, although some of the stories seem ill-fitting to their narrators, perhaps as a result of the incomplete state of the work. Chaucer drew on real life for his cast of pilgrims: the innkeeper shares the name of a contemporary keeper of an inn in Southwark, and real-life identities for the Wife of Bath, the Merchant, the Man of Law and the Student have been suggested. The many jobs that Chaucer held in medieval society—page, soldier, messenger, valet, bureaucrat, foreman and administrator—probably exposed him to many of the types of people he depicted in the Tales. He was able to shape their speech and satirise their manners in what was to become popular literature among people of the same types. Chaucer's works are sometimes grouped into first a French period, then an Italian period and finally an English period, with Chaucer being influenced by those countries' literatures in turn. Certainly Troilus and Criseyde is a middle period work with its reliance on the forms of Italian poetry, little known in England at the time, but to which Chaucer was probably exposed during his frequent trips abroad on court business. In addition, its use of a classical subject and its elaborate, courtly language sets it apart as one of his most complete and well-formed works. In Troilus and Criseyde Chaucer draws heavily on his source, Boccaccio, and on the late Latin philosopher Boethius. However, it is The Canterbury Tales, wherein he focuses on English subjects, with bawdy jokes and respected figures often being undercut with humour, that has cemented his reputation. Chaucer also translated such important works as Boethius' Consolation of Philosophy and The Romance of the Rose by Guillaume de Lorris (extended by Jean de Meun). However, while many scholars maintain that Chaucer did indeed translate part of the text of Roman de la Rose as The Romaunt of the Rose, others claim that this has been effectively disproved. Many of his other works were very loose translations of, or simply based on, works from continental Europe. It is in this role that Chaucer receives some of his earliest critical praise. Eustache Deschamps wrote a ballade on the great translator and called himself a "nettle in Chaucer's garden of poetry". In 1385 Thomas Usk made glowing mention of Chaucer, and John Gower, Chaucer's main poetic rival of the time, also lauded him. This reference was later edited out of Gower's Confessio Amantis and it has been suggested by some that this was because of ill feeling between them, but it is likely due simply to stylistic concerns. One other significant work of Chaucer's is his Treatise on the Astrolabe, possibly for his own son, that describes the form and use of that instrument in detail and is sometimes cited as the first example of technical writing in the English language. Although much of the text may have come from other sources, the treatise indicates that Chaucer was versed in science in addition to his literary talents. Another scientific work discovered in 1952, Equatorie of the Planetis, has similar language and handwriting compared to some considered to be Chaucer's and it continues many of the ideas from the Astrolabe. Furthermore, it contains an example of early European encryption.[16] The attribution of this work to Chaucer is still uncertain. Selected Works The Canterbury Tales Troilus and Criseyde Treatise on the Astrolabe The Legend of Good Women Parlement of Foules Anelida and Arcite The House of Fame The Book of the Duchess Roman de la Rose Translation of Boethius' Consolation of Philosophy (as Boece) References Wikipedia – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geoffrey_Chaucer